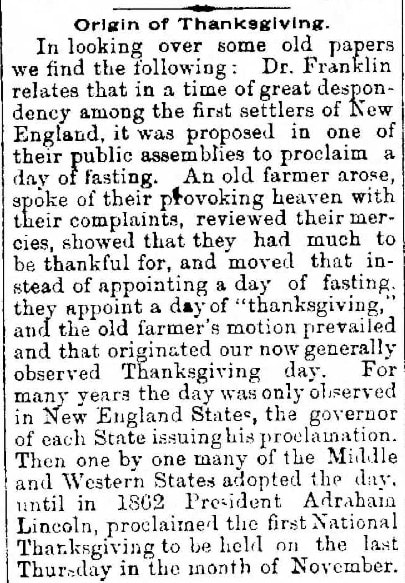

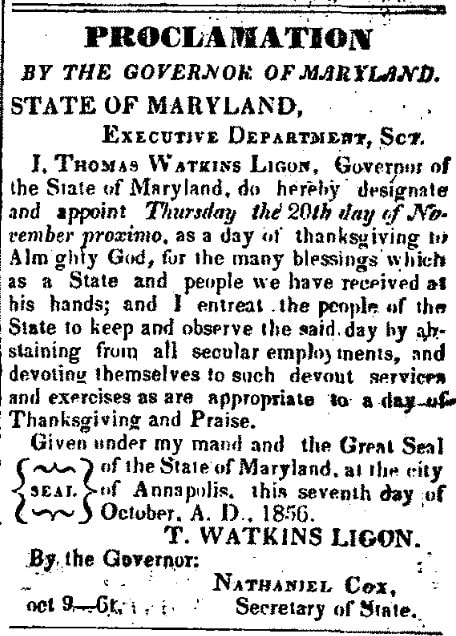

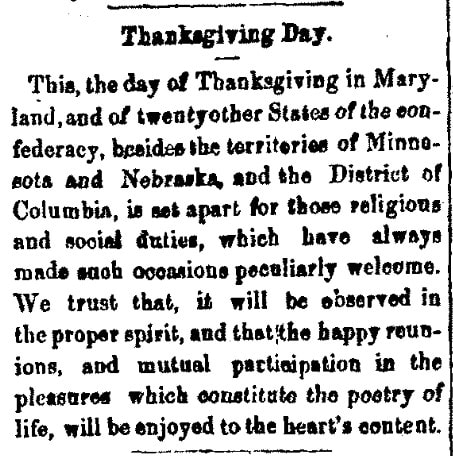

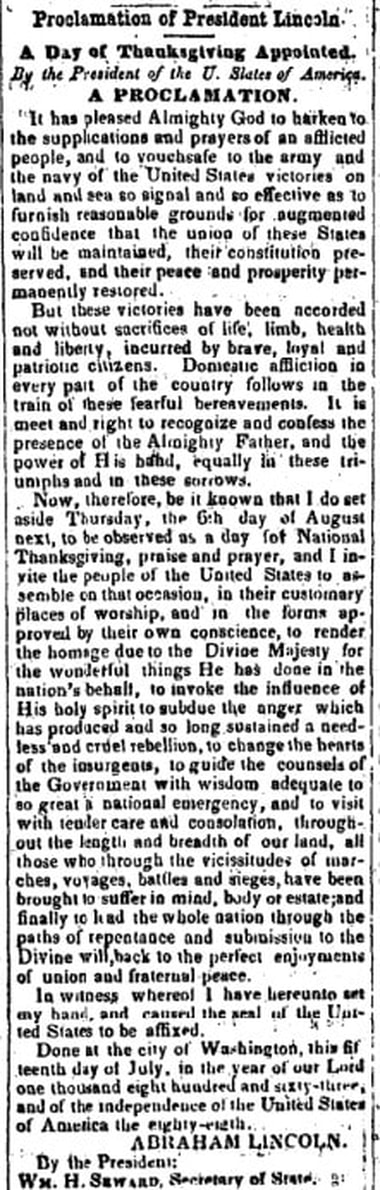

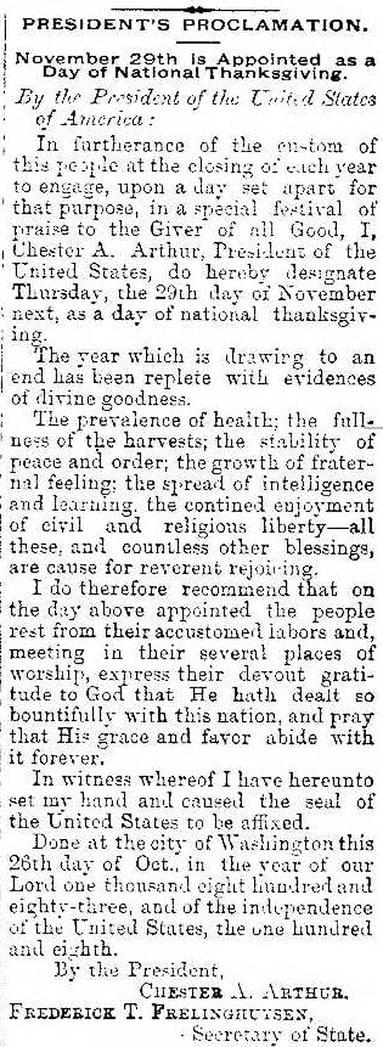

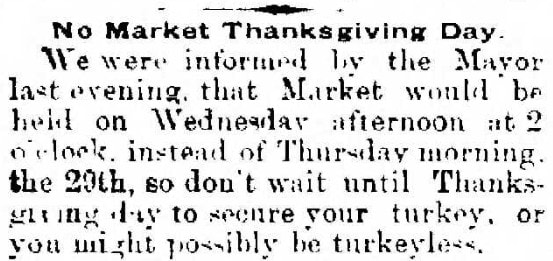

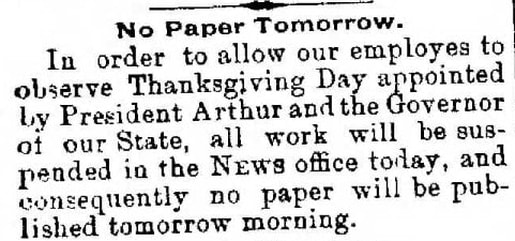

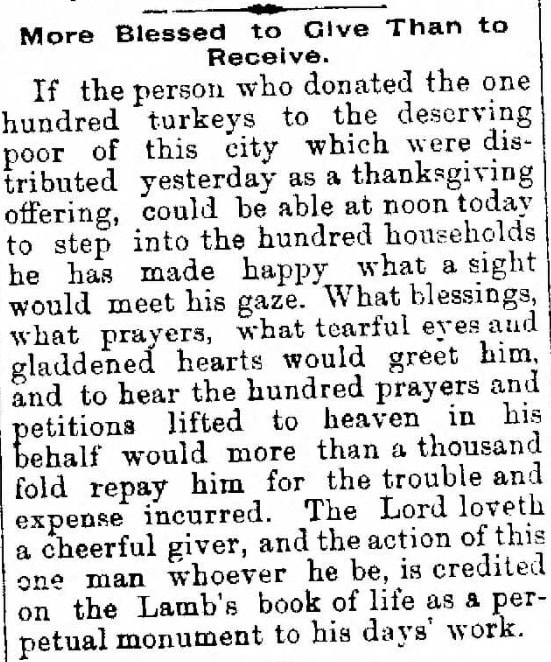

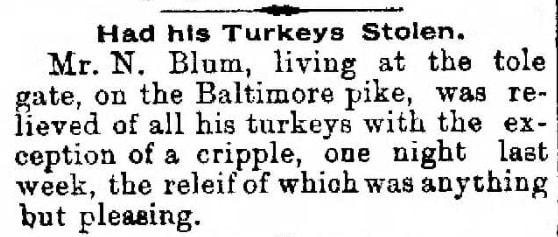

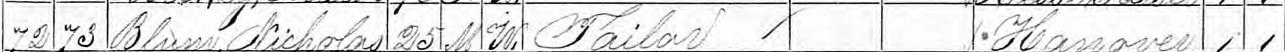

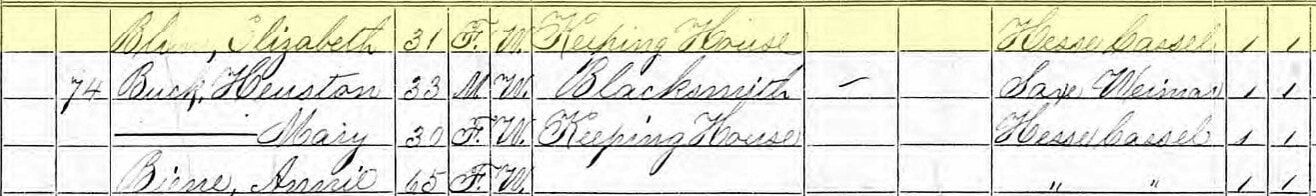

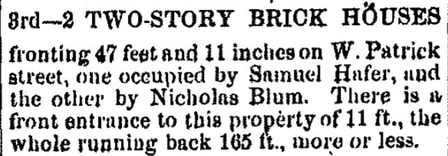

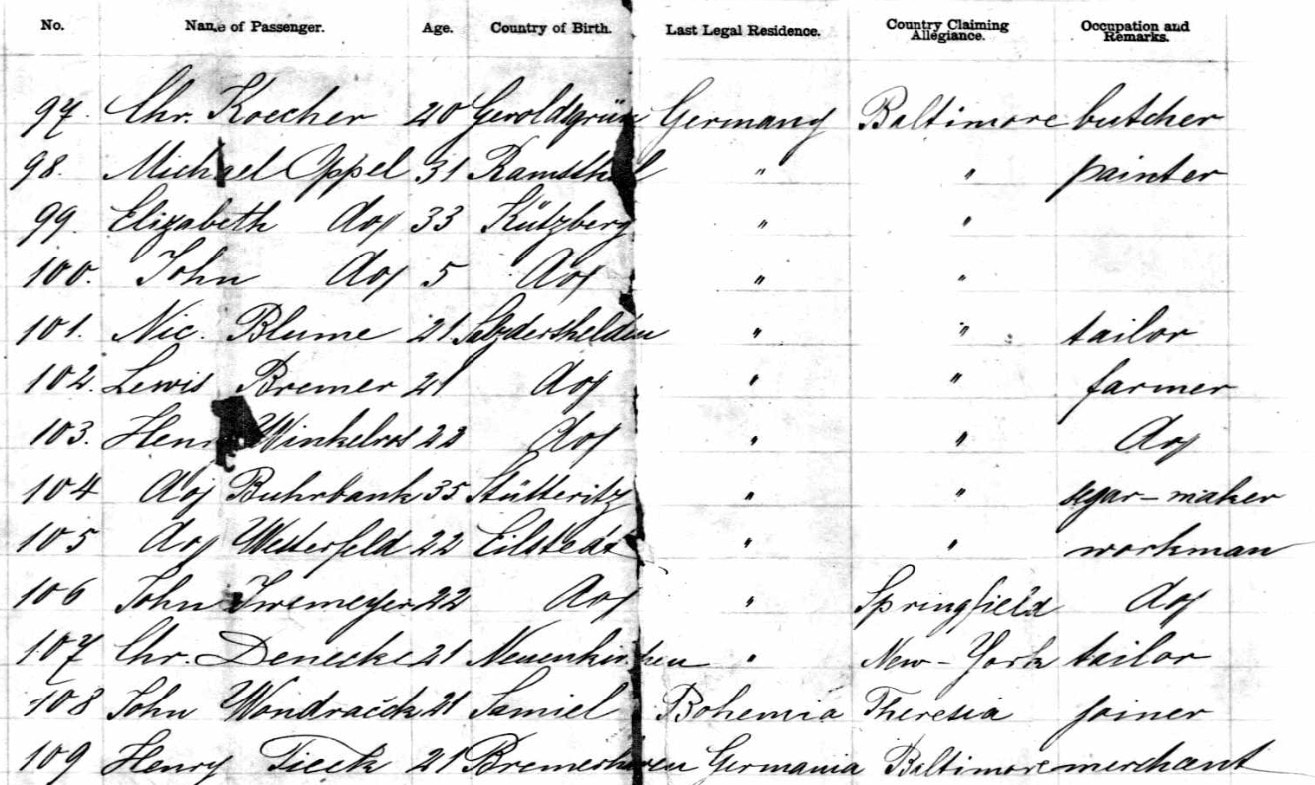

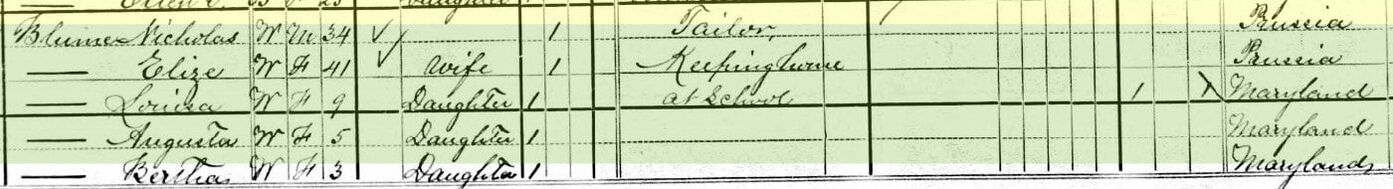

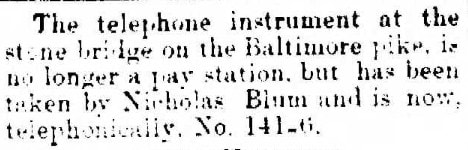

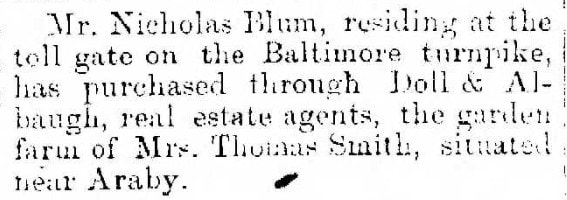

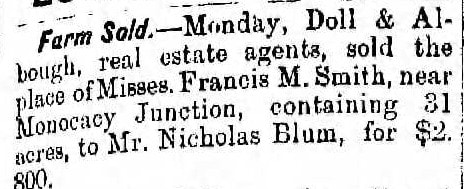

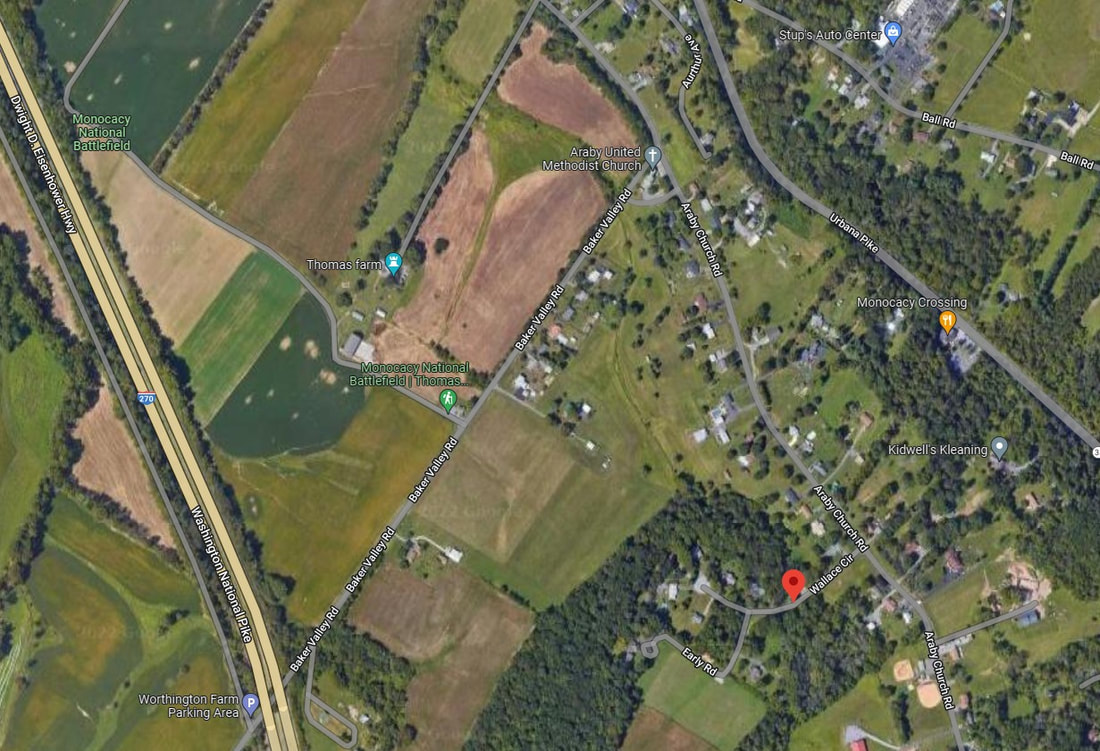

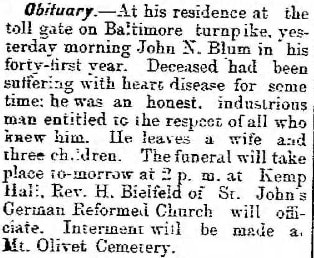

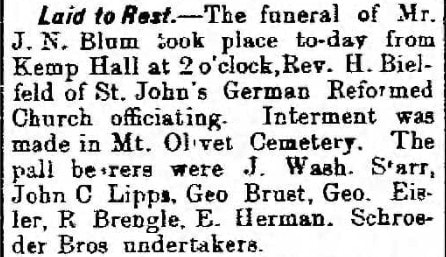

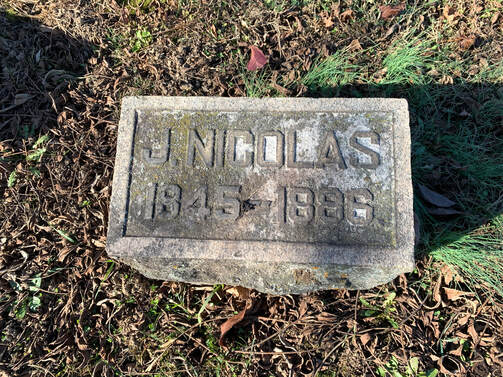

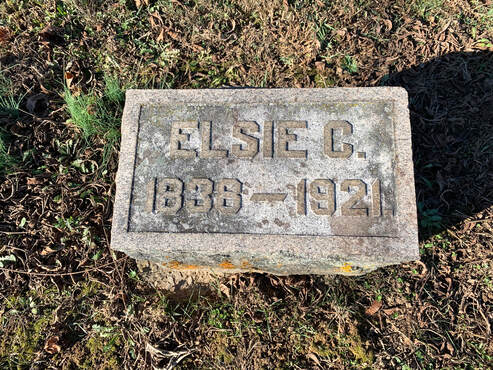

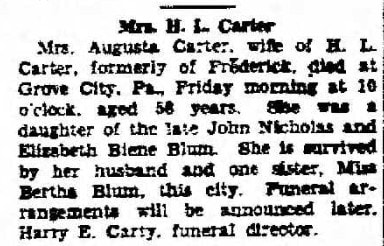

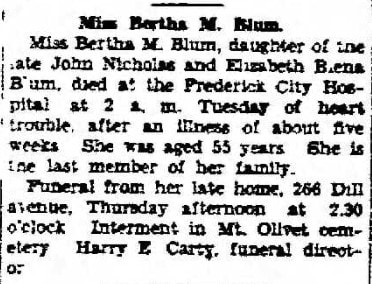

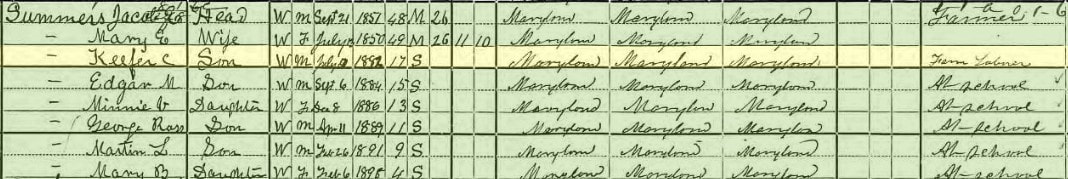

Table scene from "A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving." Table scene from "A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving." "We've got another holiday to worry about. It seems Thanksgiving Day is upon us." These were the words uttered by the immortal icon of my childhood and many others—Charlie Brown. Renowned cartoonist Charles M. Schulz gave us a classic work in his 1973 A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving that still holds its important message to this day nearly a half century after its first airing. The day in question, one beloved by millions of Americans, and naturally despised by just as many turkeys, is celebrated on the fourth Thursday of November, but began as a state holiday rather than a federal one. Thanksgiving’s origins saw it as a day of celebrating the year’s harvest, with the theme of the holiday revolving around giving thanks and the centerpiece of celebrations being a Thanksgiving dinner. Of course, the special dinner traditionally consists of foods and dishes indigenous to the Americas, namely turkey, potatoes (usually mashed or sweet), stuffing, squash, corn (maize), green beans, cranberries (typically in sauce form), and pumpkin pie. This is not exactly what Snoopy and Woodstock served up to Charlie Brown, Linus and other Peanuts characters in the 1973 classic, but what really are our expectations when at the mercy of animal chefs forced to utilize foods readily at their disposal including toast, popcorn, pretzels and jellybeans? That clever cartoon special teaches a simple lesson that focuses on what the day (Thanksgiving) is truly about—who we spend Thanksgiving with is far more important than the quality, or amount, of the food we eat on Thanksgiving. Many of us don’t truly grasp this concept until we lose someone who had shared the holiday dinner table with us year after year, such as a grandparent, parent or sibling. As many readers know, I spend a great deal of time in old newspapers in an effort to learn about the life and times of my subjects for these “Stories in Stone.” It’s sort of being like a time traveler, as I can see events from history playing out in real time, knowing of course how they end. I was searching through papers dating from the 1880s and found the passage above talking about Benjamin Franklin and his interest in origins of Thanksgiving. Many may recall that Ben Franklin also had a fondness for wild turkeys, so much so he put forth the species nomination to become our national bird. Franklin praised the turkey as “a bird of courage” and a “true original native of America.” He also said it was a better representative of the new country than the bald eagle, which he called “a bird of bad moral character” that steals fish from hawks and “a rank coward” easily cowed by sparrows. The Wikipedia explanation of Thanksgiving offers a summary stating that New England and Virginia colonists originally celebrated days of fasting, as well as days of thanksgiving, thanking God for blessings such as harvests, ship landings, military victories, or the end of a drought. These were observed through church services, accompanied with feasts and other communal gatherings. The event that Americans commonly call the "First Thanksgiving" was celebrated by the Pilgrims after their first harvest in the New World in October 1621. This feast lasted three days and was attended by 90 Indians of the Wampanoag tribe and 53 Pilgrims (survivors of the Mayflower). Less widely known is an earlier Thanksgiving celebration in Virginia in 1619 by English settlers who had just landed at Berkeley Hundred aboard the ship Margaret. Thanksgiving has been celebrated nationally off and on since 1789, begun with a proclamation by President George Washington after a request by Congress. Apparently, President Thomas Jefferson chose not to observe the holiday, and its celebration was intermittent up through the 1850s. Maryland began celebrating Thanksgiving as an official state holiday after Gov. Thomas Ligon’s proclamation of 1856. At this time, there were 17 states that followed the tradition at this level. That number would grow to 21 by the decade’s close. Mind you that there were only 33 states at that time. The American Civil War soon followed, but President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a national day of "Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens,” calling on the American people to also, "with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience ... fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation..." Lincoln declared that the special observance would occur on the last Thursday in November. As I was searching through the newspapers of fall, 1883, I came across a later proclamation from a lesser-known president having sole discretion over dictating the date of the Thanksgiving holiday as Lincoln’s successors had before him. This was President Chester A. Arthur. November 29th was a departure back to Lincoln’s spirit of the holiday being at the end of the month. In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant had moved the date to the third Thursday of November. Things got more serious as to the date when, in January of 1885, an act by Congress made Thanksgiving, and other federal holidays, a paid holiday for all federal workers throughout the United States. In 1942, while engaged in World War II, Thanksgiving received a permanent observation date as set by an act of Congress. Without the discretion or interference of the president, Thanksgiving was slated for the fourth Thursday in November. This holds true up through today. 1883 The year 1883 was fairly, uneventful in the annals of US history. However, here in Frederick, something happened that was extremely “newsworthy.” This featured the emergence of a new newspaper offering, fittingly entitled “The News.” Founded by William T. Delaplaine, the Great Southern Printing and Manufacturing Company took responsibility for publishing this new paper which commenced on October 15th. I purposely set out to glean any mentions of Thanksgiving tradition and happenings in our town in the Frederick Daily News’ first year. In addition to the two articles I’ve already shared involving Ben Franklin and Chester Arthur, I found a warning that the town market would be closed on Thanksgiving day so customers were warned to be proactive with obtaining their turkeys for dinner. I also saw that the upstart publication made plans to give employees time off for the holiday, and told readers not to expect a Thanksgiving Day edition. As a former employee of the Great Southern Printing and Manufacturing Company, I can vouch for the support of employees in family endeavors, part of the corporate culture for the entirety of this company. In that last edition (before the holiday) of November 29th, the paper included the following brief story of charity, and dare I say, benevolent assistance and giving to be thankful for. I would love to know the name of the individual who donated 100 turkeys to the lesser-fortunate families of town. I searched, but did not have an outstanding candidate, however I would bet that we have a street or building in town today likely named for him. What a great tale of charity, the essence of Thanksgiving. However, a few days earlier, I found a disappointing story of “Thanks-taking!” It involved the seemingly likeable turnpike tollgate operator John Nicholas Blum (which is spelled Nicolas on his gravestone) who resided at the time east of town on the National Pike (MD 144) on the western approach to the Jug Bridge that once spanned the Monocacy River. This foul, or fowl, travesty was certainly not an exhibition of proper holiday decorum to say the least. The German immigrant and his family had not only lost their valuable poultry, but also the main course for Thanksgiving dinner. I did get a good chuckle out of the way the article was written, but I’m sure it was not a laughing matter for Mr. Blum, who I would soon learn is buried here in Mount Olivet. So, I decided to explore his life further. Johann Nicholas Blum was born in Hanover, Germany in 1845. He can first be found living in Frederick in the 1870 US Census. Here, at 25 years of age, Blum listed his occupation as that of a tailor, and was residing on the south side of West Patrick Street near its intersection with Jefferson Street. Here, he lived with wife Elizabeth (better known as “Elise”), in a house owned by Samuel Hafer, a carpenter who would later be very prominent in the annals of local cannery operations in town. Mrs. Blum was the former Elizabeth C. Biene, and hailed from Hesse Cassel (Germany). However, in this census, her next door neighbors appear to be Biene relatives (perhaps her sister and mother). I deduct that these individuals had recently come to America. Perhaps John Nicholas Blum was the immigrant I found landing in Baltimore on February 16th, 1867 aboard a ship named Adolphine? The age, name and profession match perfectly, and the port of entry geography fits as well. Salzderhelden is given as the former home of the immigrant and this village is located close to Einbeck and 40 miles directly south of Hanover. Nicholas and Elise were members of Frederick's German Reformed Church and would go on to have three daughters and a son through the decade: Louisa (1870-1930), George (1871-1872), Augusta (1874-1932), and Bertha (1876-1939). George would die as a toddler and was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 385. Nicholas Blum did buy a lot on the north side of W. South St. in 1880 and sold it in 1884 to Annie F. Doll. He seems to have taken up residence at the toll house on the turnpike, scene of the great “Turkey Heist of ’83.” I found a few more mentions of Mr. Blum in relation to this property but soon he would be moving to a farm south of town along the Georgetown Pike. The property that the Blums bought was a portion of the greater estate of Araby, noted property which was bought in 1864 by C. Keefer Thomas. This is the famous “Thomas Farm” associated with the Battle of Monocacy and currently owned by the National Park Service. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant would conduct a clandestine meeting here with Gen. Patrick Sheridan during the Civil War, shortly after the 1864 "Battle that Saved Washington"—but that is a story for another day. The "Thomas Farm" stayed in the Thomas family until 1910. What the Blums had bought in 1884 was 31 acres, which Mr. Thomas had originally sold to Frances Albaugh in 1864, shortly after purchasing the entire farm. This property is now the subdivision called "Araby View" that surrounds Wallace Circle on the west side of Araby Church Road. It is located southeast of the Thomas Farm, across Baker Valley Road. I learned little more about J. Nicolas Blum as he would die two years after purchasing the farm on February 14th, 1886. John Nicholas Blum would be laid to rest next to his son George. I also realized that he only celebrated two more Thanksgivings after the event that triggered my interest in him. Elise Blum inherited the Araby property from her deceased husband, but in 1899 sold it to her daughter Louisa, a teacher who graduated from Towson Normal School that year. She kept this until 1904. Elise moved back in town to Frederick at this time after buying what is today’s 266 Dill Avenue in the year 1908. Here she lived with her daughter Bertha until her own death in 1921. In 1920, Louisa and Bertha Blum, along with a man named George Caulk, bought what is now 6714 Jefferson Boulevard in Braddock Heights. Louisa never married and died in 1930. Two years later, middle daughter Augusta (Blum) Carter, died as well on November 11th. She had been residing in Grove City, Pennsylvania. Her body would be brought back to the family plot for burial in Frederick as her funeral took place the week before Thanksgiving. I’m assuming that it was a particularly hard holiday for Bertha to experience without her sisters as she was the last surviving member of the family, losing Louisa and Augusta in that short span. Sadly, Bertha would die six days after Thanksgiving on November 29th. She has no headstone, likely due to her being the last survivor of the immediate family with no one to make plans for her headstone Let's end with that simple message from A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving in that we shouldn't focus on what we are eating, but instead, be most thankful for those who we are spending the holiday with along with fond memories of the opportunities had in past years with those no longer with us. (You can thank me later turkeys). Happy Thanksgiving to you all, and a huge thanks for the continued support of this blog along with the ongoing preservation and history efforts associated with our great cemetery. Please remember the Mount Olivet Preservation and Enhancement Fund and Wreaths Across America on "Giving Tuesday." Click the button below for more information.

1 Comment

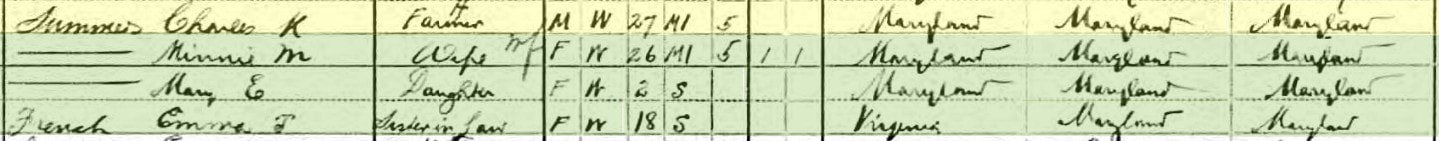

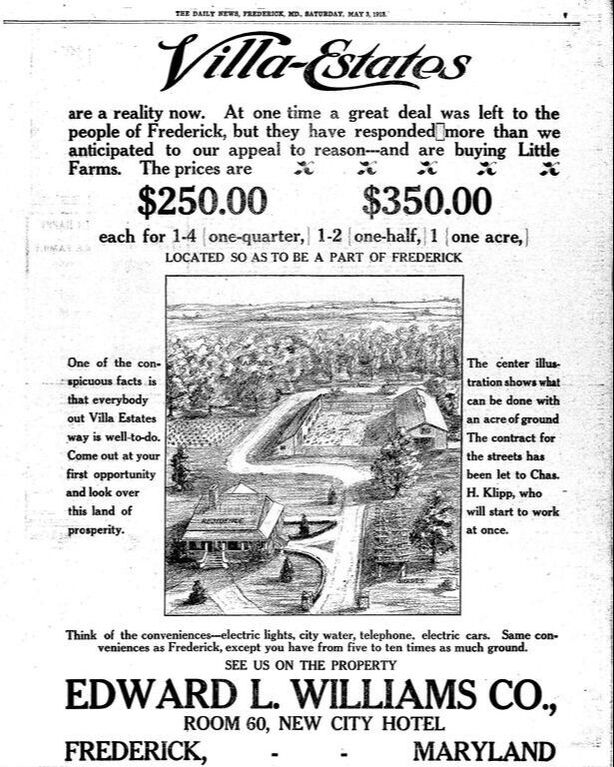

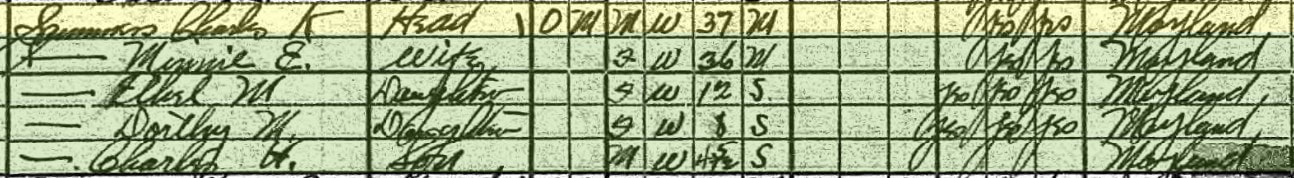

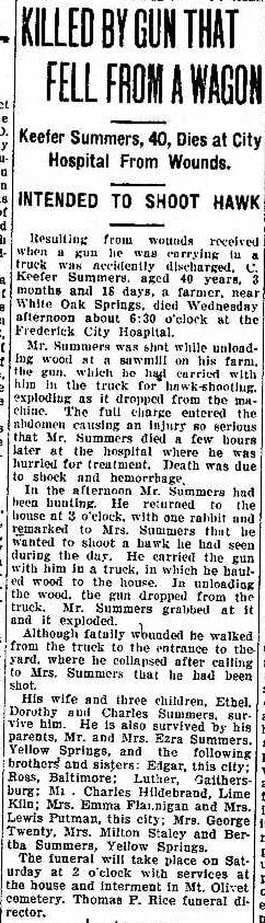

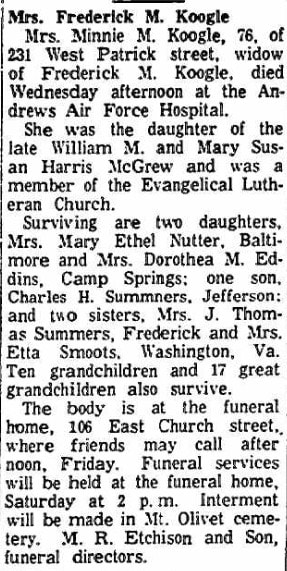

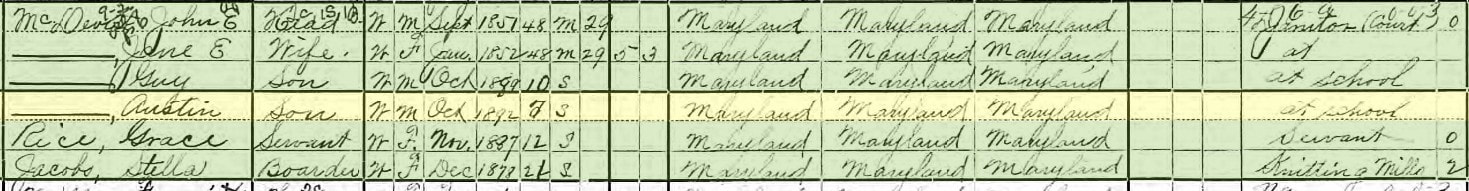

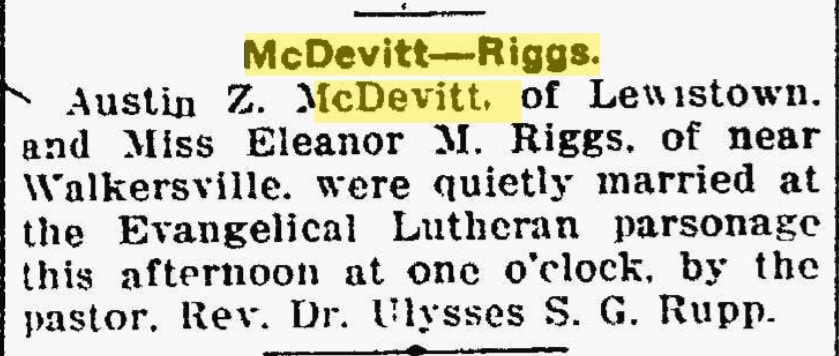

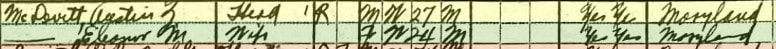

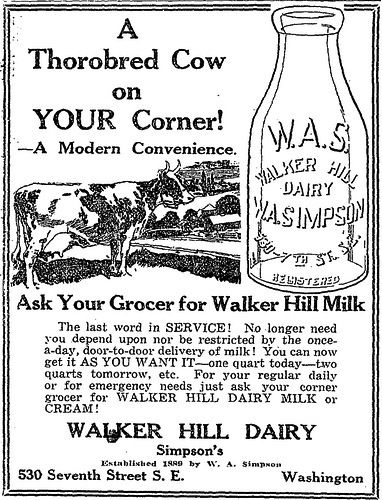

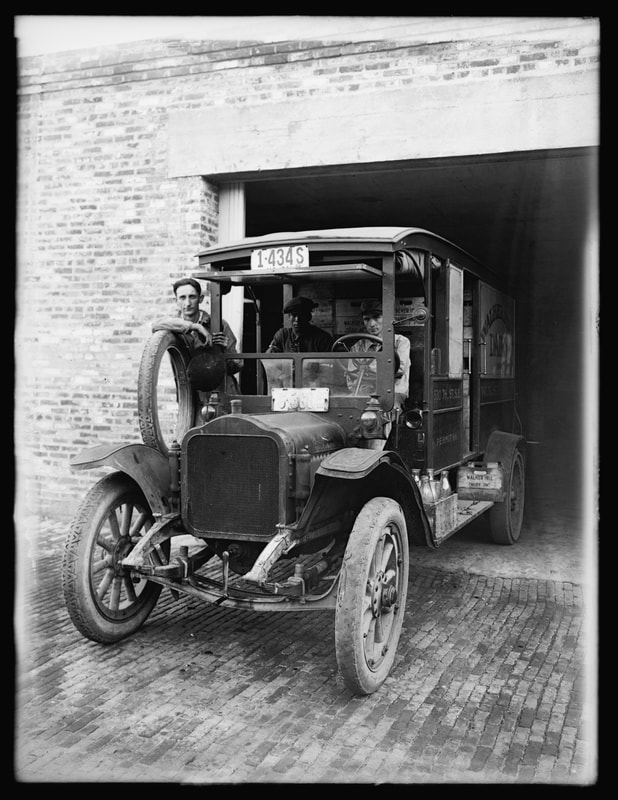

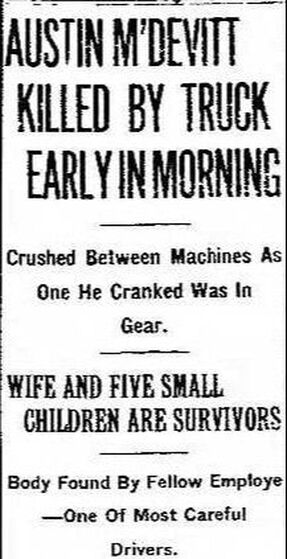

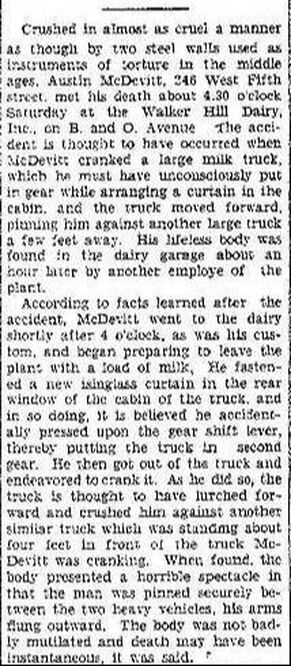

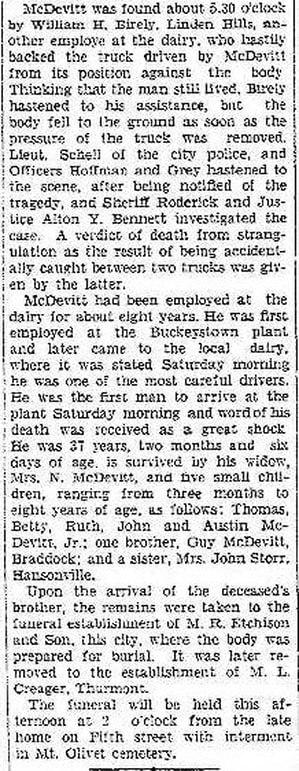

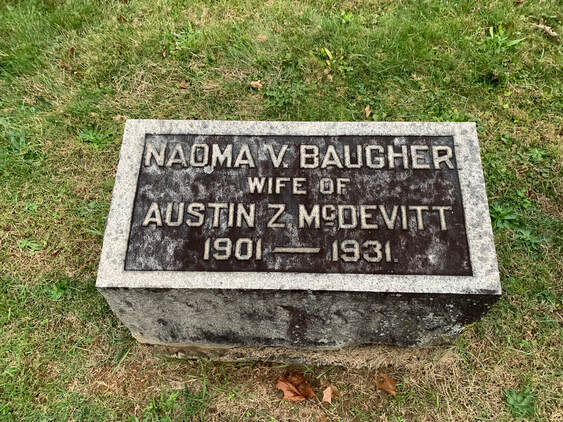

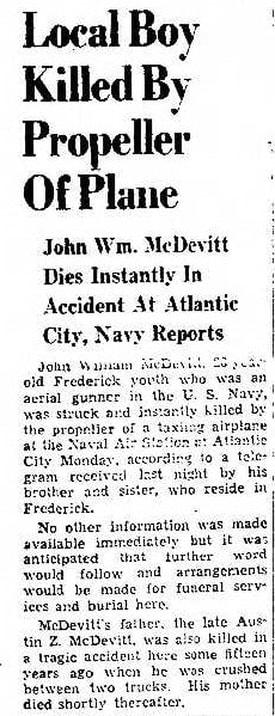

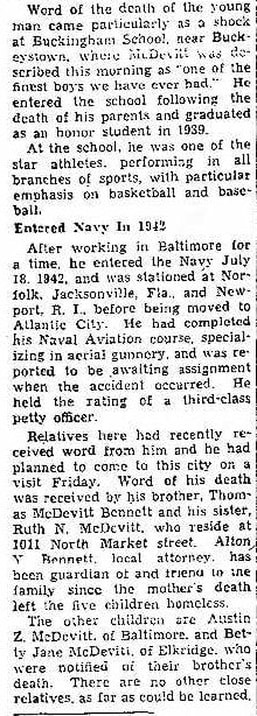

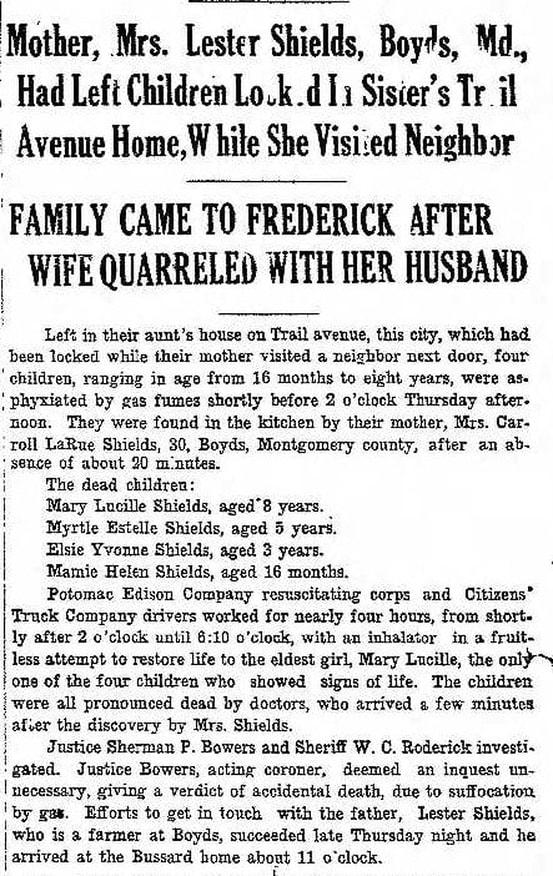

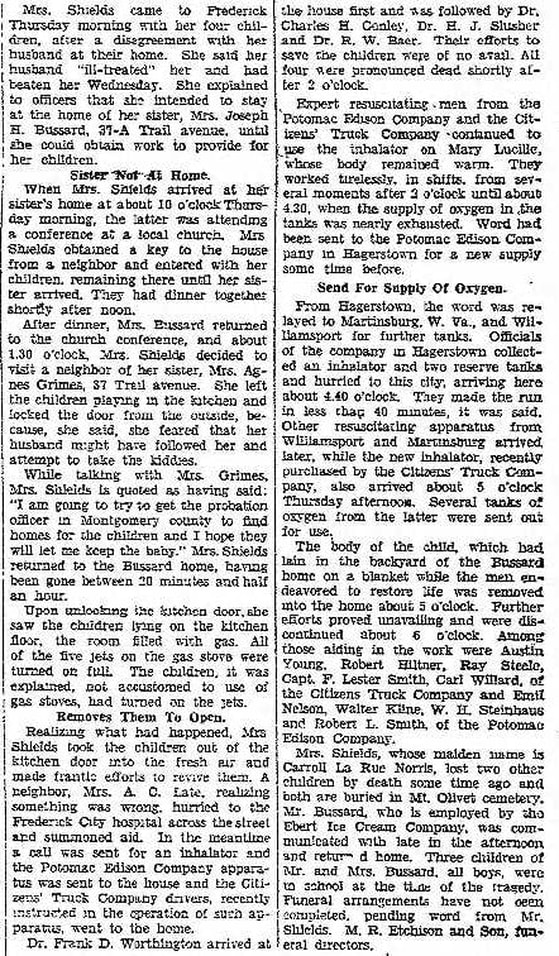

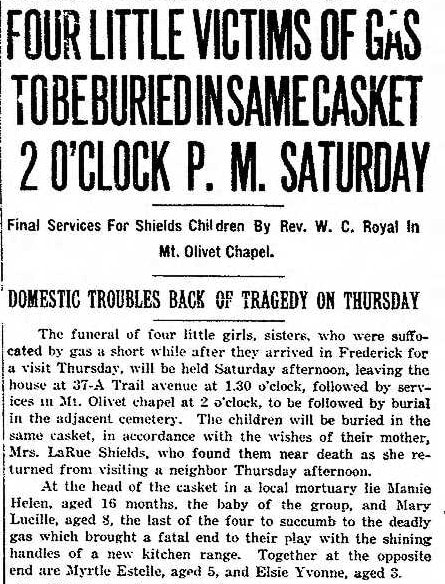

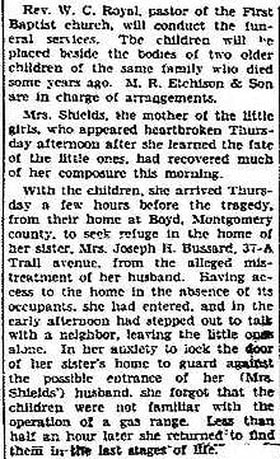

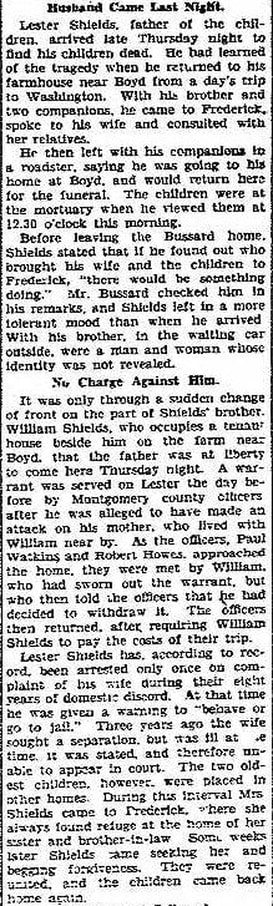

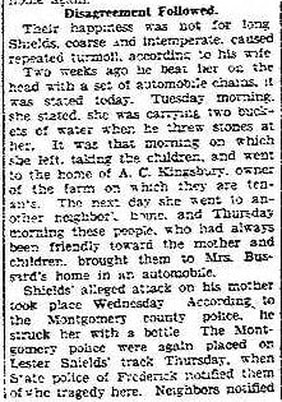

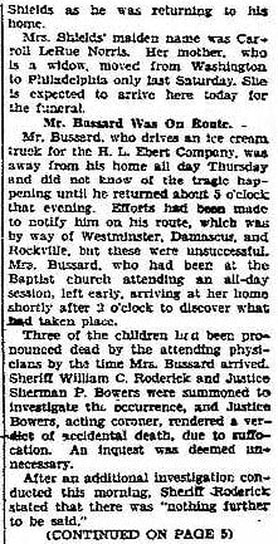

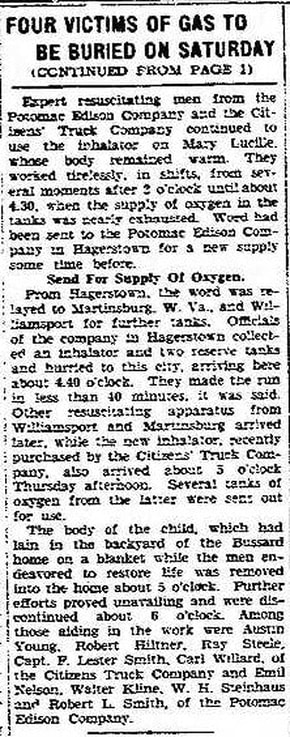

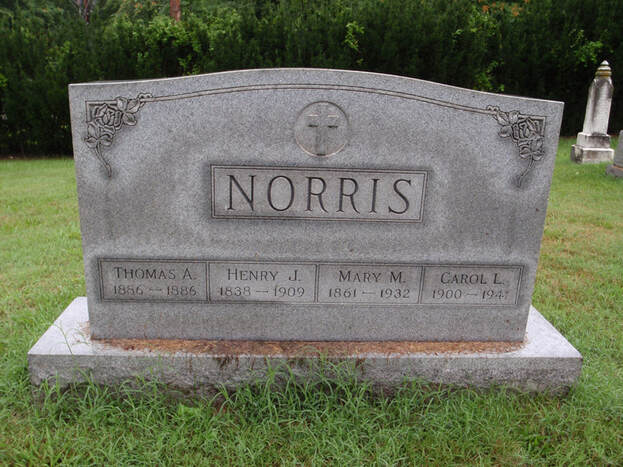

Accidents will happen, is an age-old saying usually uttered in an attempt to comfort someone after a mishap or setback has occurred. There was a motion picture starring Ronald Reagan that utilized this idiom as its title, and many of us, of a certain age, may recall the popular song by Elvis Costello and the Attractions from 1979. Inevitable parts of life, most accidents are somewhat harmless in the bigger picture with a common case in point—the spilling of milk. Other accidents, such as the typical vehicular “fender bender” are certainly a bit more serious in nature, and usually cost participants money and inconvenience. However, there are more serious accidents which are devastating, and, dare I say, even deadly. I’m going to share three of the latter variety with you in this particular “Story in Stone,” but there are many more that can be talked about in context with our fair cemetery. I was inspired to pursue this theme the other day when looking at a newspaper from November 16th, 1922. The newspaper included a front-page story involving a freak gun accident which turned fatal for a local farmer. This added to the tales of two other incidents (from later in that same decade) that have been ruminating in my head in recent weeks since talking about them on recent candlelight tours I gave. (WARNING: I must add that the following stories with accompanying newspaper accounts will be quite unsettling, so please be forewarned as this is a heart-wrenching edition. ) Charles Keefer Summers Even in Fall, one will find plenty of “Summers” here in Mount Olivet. We have two such individuals with this surname on our cemetery’s Board of Directors as well. The Summers in question here is a gentleman named Charles Keefer Summers, born in 1882. It appears that Mr. Summers was born and grew up in Yellow Springs area northwest of Frederick City. He was one of 10 children. His father, Jacob Ezra Summers, bought a 62-acre farm in 1886, the current location being 6201 Ford Road, home to a dog kennel business. The Summers family would later own property along Yellow Springs Road, adjacent my old elementary school (today 8701A, 8701B and 8701C Yellow Springs Road). Charles Keefer acquired 8701C from his father in 1916. He built a sawmill on the property, a very useful thing to have since he owned a 16-acre woodlot in the vicinity of Spout Spring Road about two miles south. Its not known how long Charles Keefer Summers lived here, as he would acquire a few different properties during his life. He bought a farm near a place called White Oak Springs in 1909 shortly after the birth of his daughter Ethel Mary. He had married Minnie Mae McGrew of Walkersville in 1905. He would go on to have two more children, Dorothy Mae Summers (1912-2000) and Charles Hammond Summers (1915-2007) The Charles K. Summers residence was on the west side of New Design Road, south of Ballenger Creek and along White Oak Springs Road (which no longer exists but once ran along the south side of Ballenger Creek between New Design Road and Buckeystown Pike.) This property is now the Robin Meadows development. More recently known as the Griffin Farm, the nearby White Oak Springs to the northwest of the Summers property constitutes land within a housing community called the Enclave at Ballenger Run, located a few hundred yards east of Tuscarora High School. Charles also bought what is now 407 and 409 Wilson Place in 1917. This was part of a new suburban development named Villa Estates. He would never live here, selling to a William Warfield in 1920, at which time the existing house was constructed. This may explain Charles’ occupation as listed as “contractor” in the 1920 US Census. These lots in Villa Estates were advertised as “little farms” and attractive opportunities to live in the city, while having the opportunity to grow your own garden and raise chickens. “Keefer,” as he was more commonly known, would meet his early demise at his home near White Oak Springs. I’d like to remind you that this was purely by accident. The ill-fated day was that of November 15th, 1922. Here is the story that appeared in the Frederick News on November 16th. Charles Keefer Summers body was laid to rest in Mount Olivet’s Area MM/Lot 81, not far from the grave of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. Wife Minnie would remarry two more times. She appears to have rented the property near White Oak Springs until 1933, at which time she sold the property. Minnie died in 1960. Austin Z. McDevitt Down the hill and to the east of Charles and Minnie Summers gravesite is that of Austin Zimmerman McDevitt in Area OO/Lot 130. Here we have the victim of another accidental death, which claimed the life of a gentleman only 37 years old. In the annals of history, 1929 was not the greatest of years anyway. Although it started well, you may recall “the Great Crash” which had nothing to do with automobiles, but everything to do with Wall Street as this was the legendary stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of that year. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange collapsed and sparked the following decade and an era coined “The Great Depression.” Austin Zimmerman McDevitt was born October 15th, 1892. He was the son of John Edward McDevitt (1851-1919) and wife, Rebecca Jane Zimmerman (1852-1901). The family lived in Charlesville, directly north of Frederick, near Lewistown. Austin was the fourth of four children. Sadly, Austin would experience great loss in his life. His mother passed when he was 9 years old. He married Eleanor May Riggs in 1916, and the couple had a daughter, Lulu May in 1918. In the next two years, our subject would lose both his infant daughter and young wife. Lulu passed at eight months of age of pneumonia and Eleanor died in the State sanitarium at Sabillasville of tuberculosis at the age of 24. Austin would marry again in late 1920, this time to Naomi V. Baugher. The couple would have five children and resided at 246 West 5th Street in Frederick City. Mr. McDevitt worked for the Walker Hill Dairy located on B&O Avenue in the southeast part of Frederick. This operation was begun by William A. Simpson (1864-1948), who had bought properties at G Street in southeast Washington, D.C. around 1900, and expanded the stables from his Walker Hill Dairy, which delivered Frederick County, Maryland, milk to area doorsteps until 1929. I presume that the Frederick division hailed from the White Cross Milk operation. Our subject here was a deliveryman, himself. Sadly, Austin Zimmerman McDevitt’s life of love and loss would come to an abrupt close in the early morning hours of December 21st. Austin Z. McDevitt would be buried on December 23rd in the same plot he had buried his wife and daughter years before. On Christmas Eve, 1929, Naomi McDevitt found herself a grieving widow with five children. A terrible accident had changed the upward trajectory of a young family. While conducting research on the McDevitts, I also learned that Christmas Eve, 1929 marked misfortune for the White House down the road in Washington, DC. A children’s Christmas party held by President Herbert Hoover and attended by aides and friends was suddenly disrupted by a fire that would rage in the presidential residence’s West Wing executive offices. Despite the four-alarmer bringing some 130 firefighters to the White House, the children were never aware. The press room was destroyed, and the offices suffered substantial damage. However, the fire was out by 10:30 p.m. I’ve included a clipping from the Frederick Post from December 26th, 1929, along with a link to a short video produced by the White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/videos/1929-christmas-eve-fire-at-the-white-house While the White House would make a full recovery over coming months into 1930, things would get progressively worse for the family of Austin Z. McDevitt. Naomi McDevitt would die suddenly of a heart attack in 1931. The orphaned children had lost both parents in tragic manner. I am assuming they would be raised by relatives, and learned that at least one, John William McDevitt would attend the Buckingham School for Boys in Buckeystown, as I would think that his brother Austin Zimmerman McDevitt, Jr. would as well. I know of John’s fate because he is buried beside his mother and within a few yards of his father in Area OO/Lot 130. This veteran of the US Navy would sadly, like his father, lose his life due to a freak accident while in the line of duty. He was only 20 years of age. When I ventured to the gravesite to take pictures for this story, it gave me great pleasure to see that John W. McDevitt’s grave was marked with a flag for Veterans Day. I also took pause to think that on the 93rd anniversary of his father’s unfortunate death, and 79 years after his own, John William McDevitt will have a wreath on his grave courtesy of our annual Wreaths Across America program. Shields Children The months of January, February and March of 1930 found the McDeVitt family reeling, and President Hoover utilizing a makeshift office. The latter would not move back into the West Wing until mid-April, at which time we had a local family and an entire community in shock over one of the worst accidents in Frederick's history—one in which four young children would die as a result. This event not only made front page news locally and regionally, but it was covered in publications across the country. A fight between a married couple originating in Montgomery County led to a series of events resulting in fatal consequences. It was the mother of all accidents, and exemplified the height of just how tragic and disturbing a mishap could be. It didn't involve a weapon, as we saw earlier in the case of Charles Keefer Summers, or vehicles (truck/airplane) as witnessed in the deaths of Austin McDeVitt and son John William. No, it was a typical household appliance that is better known for aiding life with food preparation, instead of impacting, or heaven forbid, taking life away. The fateful day in this case was Thursday, March 27th. To summarize, Mrs. Carol LaRue Shields came to Frederick to confer with her sister after having a fight with her husband Lester at their home in Boyds (Montgomery County). Mr. Shields was a former veteran of World War I, who served with Company K of the 29th Division in France. He worked as a farm laborer. Mrs. Shields was a mother of four at the time, and had traveled to Frederick to see her sister (Elsie Bussard) to receive support for her most recent altercation with Lester. Elsie not being home at the time precipitated Mrs. Shields to seek a neighbor to tell of her trouble with her husband. Thinking the children would be alright unsupervised for a short amount of time, Mrs. Shields made "the accident of her lifetime" as the children did the unthinkable. The Shields had already lost two infants in 1920 and 1924. These were buried in a Shields family lot in Area B/Lot 70. Upon visiting, I could not find these children as "names in stone," as their graves remain unmarked. As for the Shields as a couple with severe issues, they had lost all their children in an instant. With some additional research, we found that the true address of the Bussard residence is today's 612 Trail Avenue, directly across the street from the hospital.  Shields grave at Parklawn Shields grave at Parklawn An excruciating story, one that certainly got more than its proper share of coverage. In mid April, census records show me that Mr. and Mrs. Shields estranged with Lester Shields living with his brother in Clarksville. They would divorce and I found that Lester would remarry (Maggie Geneva (King) Sheckels) and live in Montgomery County until his death in 1964. The couple are buried at Parklawn Memorial Park in Rockville. I could not find Carol LaRue Shields in that census of 1930. She would remarry, however, seven years later in February, 1937. Her marriage to Robert D. Dickinson would only last for just over four years as Carol died in June, 1941. She is buried in the Norris family plot at Monocacy Cemetery in Beallsville, Montgomery County. The six children of Lester and Carol Shields are buried in Area B, all without tombstones. They are surrounded by Shields family members of earlier generations.

Accidents can be quite terrible things. They will happen yes, but they can also be avoided in some cases as well if caution and proactive thinking is considered at all times. God bless those mentioned in this unsettling story, as lives certainly did not get the chance to be lived to the fullest in all circumstances. Veterans Day weekend and thousands of flags are gently blowing in the breeze here in Mount Olivet Cemetery. These were placed on the graves of former military personnel last Saturday November 5th by hundreds of volunteers, both young and old. The Veterans Day holiday, itself, is recognized on November 11th each year, symbolic as the date when World War I officially ended in 1918. For over a century, November 11th has been a national holiday in France, and was declared a national holiday in many Allied nations. However, many Western countries and associated nations have since changed the name of the holiday from Armistice Day, with member states of the Commonwealth of Nations adopting Remembrance Day, and the United States government opting for Veterans Day. At the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, the Great War ended. At 5 am. that morning, Germany, lacking manpower and supplies and faced with imminent invasion, signed an armistice agreement with the Allies in a railroad car outside Compiégne, France. World War I left nine million soldiers dead and 21 million wounded, with Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, France and Great Britain each losing nearly a million or more lives. In addition, at least five million civilians died from disease, starvation, or exposure. Twelve Frederick boys, buried in Mount Olivet, died while engaged in active duty. I’ve written previous stories about each of these individuals. 600 other veterans, including four known women, joined their comrades here when their lives on earth came to fruition.

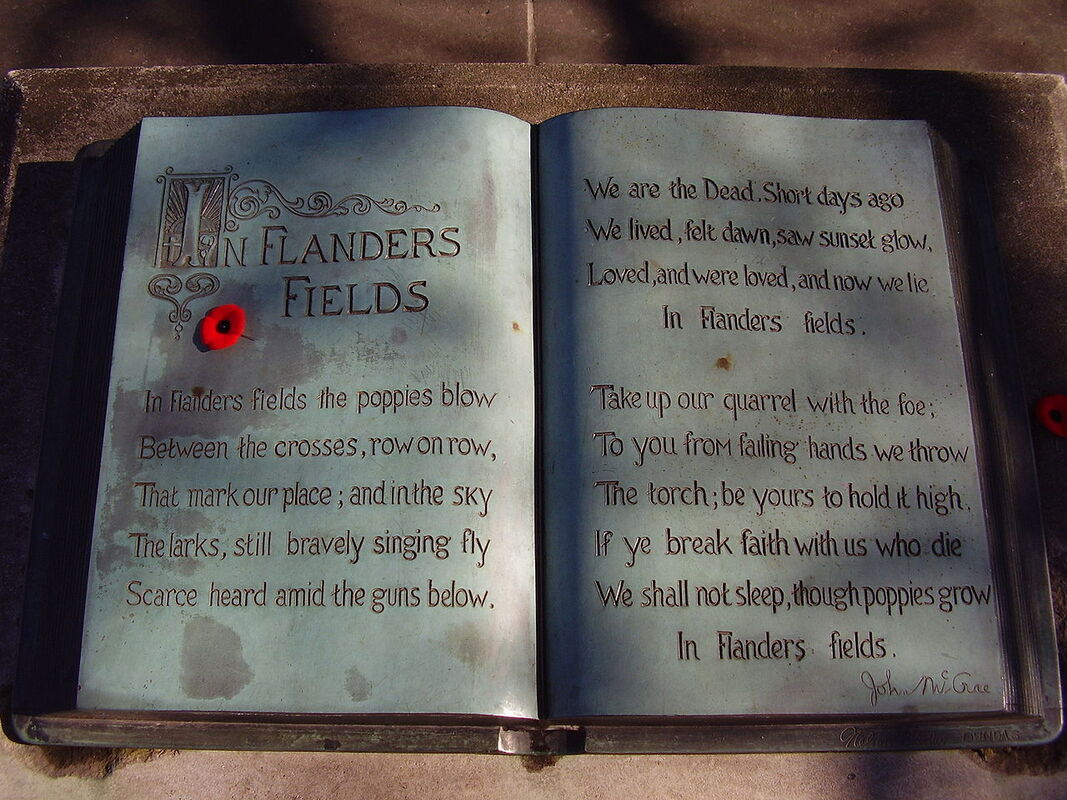

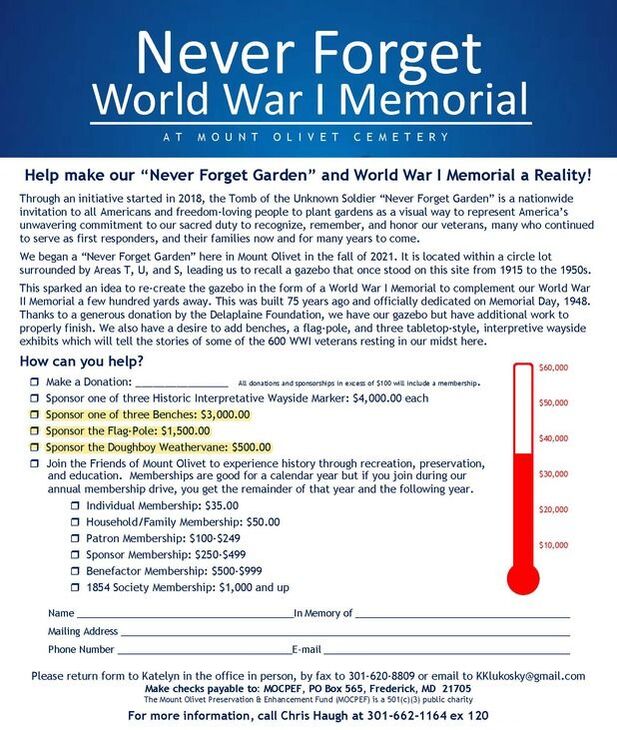

As part of the ceremony, we acknowledged 11 knockout roses which were planted on the perimeter of the gazebo as part of a Never Forget Garden. This idea “germinated” from Arlington Cemetery through an initiative started in 2018. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Never Forget Garden is a nationwide invitation to all Americans and freedom loving people to plant gardens as a visual way to represent America’s unwavering commitment to our sacred duty to recognize, remember, and honor our veterans, many who continued to serve as first responders, and their families now and for many years to come. There are many ways and traditions that are available to express patriotism, love, mourning and remembrance. The Never Forget Garden Marker, designed in collaboration with the artists at Carruth Studio, was inspired by the sacred duty of the American people to never, ever forget or forsake all those who have served and sacrificed on behalf of America in times of war or armed conflict. Its message beckons the visitor "to pause in this special place, and with a quiet soul open your heart to allow these plantings to speak; to reflect upon the deeds of those who we owe a debt that can never be fully repaid; and to think about those immutable truths that define us as Americans secured by their full measure of devotion." Occasioned by the Centennial of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a Never Forget Garden and this marker are intended to be a place to remember, to honor, and to teach. It is a place of remembrance and renewal of our commitment to the living, the dead, and those yet to serve our Country. We originally scheduled our dedication event for October 1st but it was postponed to month’s end due to rain, the remnants of Hurricane Ian which did a number on western Florida. On our second try, we had perfect weather, and an equally nice ceremony to go with it. The late October event featured a few highly talented speakers. One of which was Richard Azzaro, a former guard of the Tomb of the Unknown soldier from March 1963-April 1965. Mr. Azzaro is co-founder of the Society of the Honor Guard, Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and served as the organization’s inaugural Vice President and later as President. He is the current director of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Never Forget Garden Committee. He was joined by Chaplain Charles J. Shacochis, Jr., who also served as part of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier honor guard from February 1965 until February 1967.  tri-color cockade tri-color cockade These gentlemen explained that the recent Centennial of World War I was not only a celebration to remember the burial of the World War I Unknown Soldier, but an opportunity to reflect on what the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier means to America. The legislation that created the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, written by Congressman Hamilton Fish, viewed the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier as a focal point to bring all Americans together—that its meaning be not limited to the Great War and the exclusive claim of that War’s veterans. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington is an American symbol of remembrance that has a connection to an organization to Le Souvenir Francais. In 1887 this organization began in northern France in an area known as Alsace-Lorraine that was claimed by Prussia after the War of 1870. To remember French soldiers who had died fighting Prussian (German) soldiers, young French girls placed flowers and tri-color cockades of the French flag on the tombstones of these departed warriors despite the orders of Prussian officials who occupied Alsace-Lorraine not to decorate the graves. A professor from the area, Xavier Niessen organized the Le Souvenir Francais to honor these dead soldiers. As word spread throughout France, a swell of patriotism grew. On March 7, 1887 Professor Niessen petitioned the French government to join Le Souvenir Francais and they did. Up until 1914 and the start of Great War, Le Souvenir Francais created monuments and participated in ceremonies across France honoring war dead. In 1914 the organization began affixing tricolor cockades on tombstones of France’s dead near hospitals and cemeteries. Following the end of World War I, Le Souvenir Francais was unable to access the graves of the dead still on French battlefields. The government was concerned about the spread of disease, unexploded ordnance and other hazards. Around the 1st of November, All Saints Day, ceremonies were organized away from the battlefields to place flowers on graves and help bereaved families. It was during one of these ceremonies that Francis Simon asked the French government to transfer the body of an Unknown French Soldier from the battlefield to Paris. The commanding general of American forces in France, Brigadier General William D. Connor, learned of the French project while it was still in the planning stage. Favorably impressed, he proposed a similar American project to the Army Chief of Staff, General Peyton C. March, on October 29, 1919. Gen. March ultimately did not approve Gen. Connor's proposal. Mrs. M. M. Melony, editor of the Delineator, made a similar suggestion to Gen. March. In his reply Gen. March explained to Mrs. Melony that while the French and English had many unknown dead, it appeared possible that the Army Graves Registration Service eventually would identify all American dead. Furthermore, the United States had no burial place for a fallen hero similar to Westminster Abbey or the Arc de Triumphe. In any case, March pointed out, the matter was one for Congress to decide. On December 21st, 1920, Congressman Hamilton Fish, III of New York introduced a resolution calling for the return to the United States of an unknown American member of the overseas Expeditionary Force killed in combat in France and his burial with appropriate ceremonies in a tomb to be constructed at the recently built Memorial Amphitheater in Arlington National Cemetery. The measure was approved on March 4th, 1921 as Public Resolution 67 of the 66th Congress. Fish had originally intended for the ceremony to take place on Memorial Day 1921 but it was too late for that date. Then on October 20, 1921, Congress declared November 11th, 1921 a legal holiday to honor all those who participated in World War I; an elaborate ceremony in Washington would pay tribute to the symbolic unknown soldier. On September 9th, 1921 the Quartermaster General received orders from the War Department to select an unknown soldier from those buried in France. Following the selection ceremony, he was to deliver the body to Le Havre, where the Navy would receive it for transportation to the United States. The necessary arrangements were completed by the Quartermaster Corps in France in cooperation with French and U.S. Navy authorities. According to plans, the selection ceremony was to take place at Chalons-sur-Marne, ninety miles east of Paris, on October 24th, 1921. The honor of making the selection went to Sergeant Edward F. Younger, a decorated World War I veteran sent from his posting in Germany to support the selection ceremony. To indicate his choice of the Unknown Soldier, Younger placed a spray of white roses upon one of four caskets that contained the remains of unidentified American service members. These roses held deep meaning. They were donated by Brasseur Brulfer, a former member of the Châlons City Council who lost two sons in the war, including one whose remains were never identified—just like the American Unknown being honored that day. Grown in the earth of France, these roses formed a tangible connection between the American Unknown, the unknown dead of France and the French nation itself.  Thousands — including President Harding — gather for the burial of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery on Nov. 11, 1921. (Library of Congress) Thousands — including President Harding — gather for the burial of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery on Nov. 11, 1921. (Library of Congress) After the selection ceremony, the roses were placed on top of the flag-draped casket of the newly designated Unknown Soldier. Various sources, images and motion picture footage indicate that the roses from the selection travelled with the Unknown through many stages of his journey back to the United States, and may have been buried with him inside the Tomb. In the years after 1921, the white rose came to symbolize the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. To this day, it is frequently used in commemorations related to the Tomb, such as a recent ceremony at Sgt. Younger’s grave on October 24th, 1921, to mark the 100th anniversary of the selection. Mr. Azzaro wrapped up his comments by placing a bouquet of white roses on our Never Forget Garden marker. Additional remarks were given by Corey Campion, Associate Professor of History and Global Studies Program Director, Master's in Humanities and Chair, Dept. of History. Corey has conducted much research on World War I, which has culminated in him co-authoring a book with teaching colleague Trevor Dodman (also of Hood College), creating a curriculum to instruct educators and leading a tour a few years back to the former battlefields of France. Corey spoke to the importance of remembering not only the war dead, but also the veterans of any and all military conflicts. He referenced the Victory monument in Frederick’s Memorial Park, site of the annual Veterans Day program, along with other such sites in the county such as the Doughboy Memorial in Emmitsburg, Middletown's Memorial Hall and the William Bunke Memorial in Libertytown’s St. Peter’s Catholic Cemetery. Now our Mount Olivet World War I Memorial Gazebo joins that esteemed collection. Professor Campion took the opportunity to continue on the theme of flowers representing life, yet connecting to battlefield sacrifice as our earlier speakers had explained the importance of white roses in Mount Olivet’s Never Forget Garden. He spoke on the symbolism behind the red poppy flower and read the epic poem “In Flanders Fields.” The opening lines of this work refer to poppies growing among the graves of war victims in a region of Belgium. The poem is written from the point of view of the fallen soldiers and in its last verse, the soldiers call on the living to continue the conflict. The poem was written by Canadian physician John McCrae on May 3rd, 1915 after witnessing the death of his friend and fellow soldier the day before. The poem was first published on December 8th, 1915 in the London-based magazine Punch.

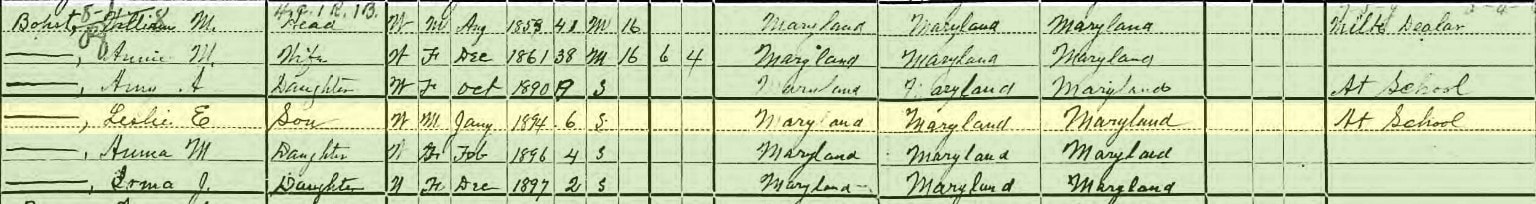

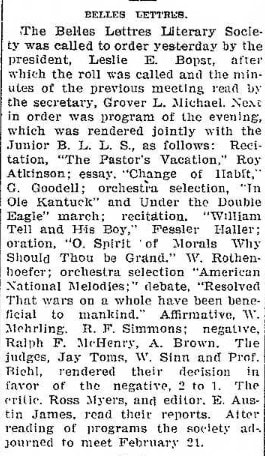

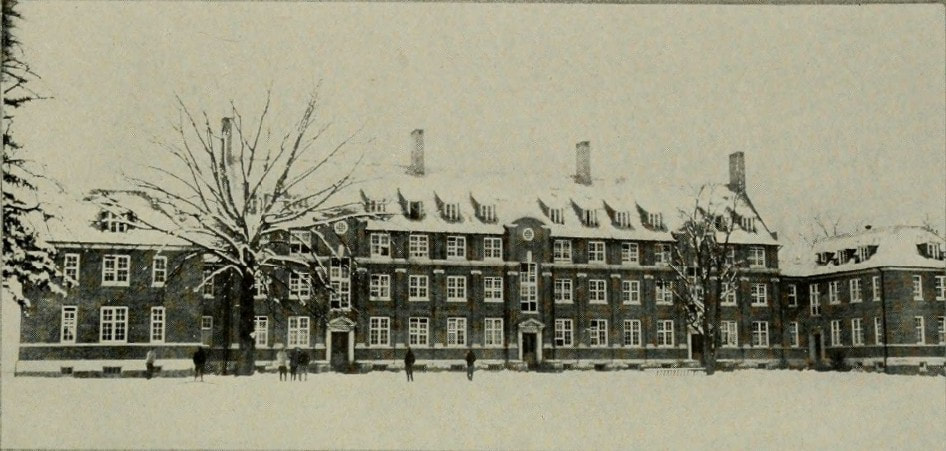

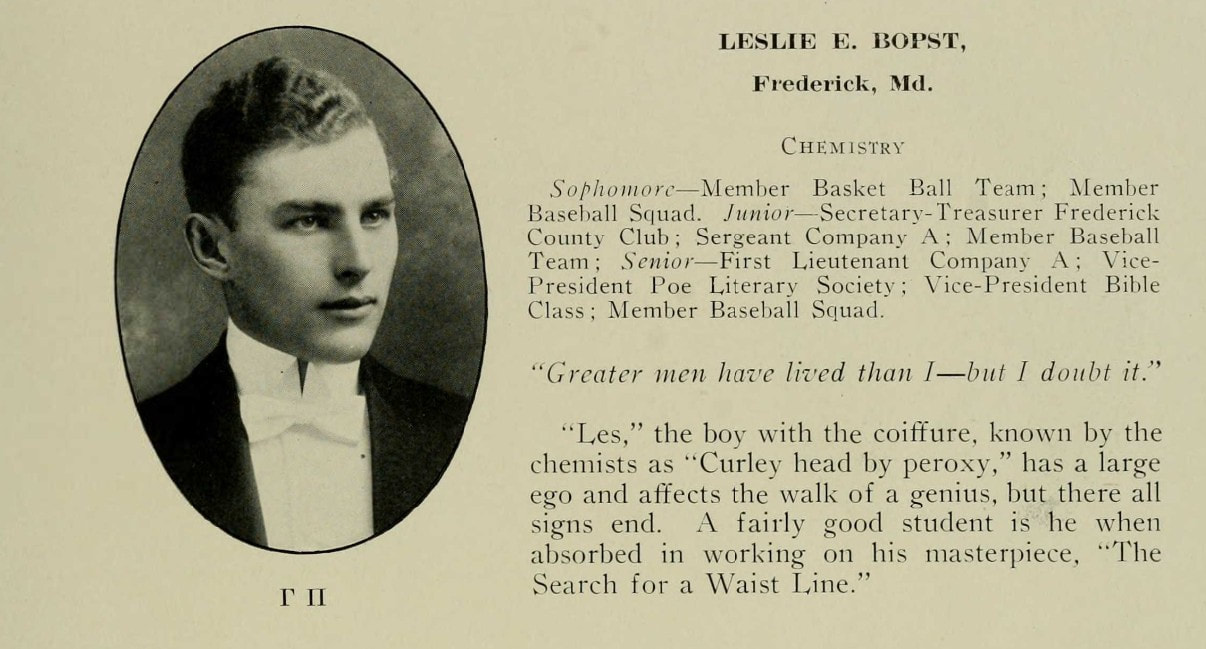

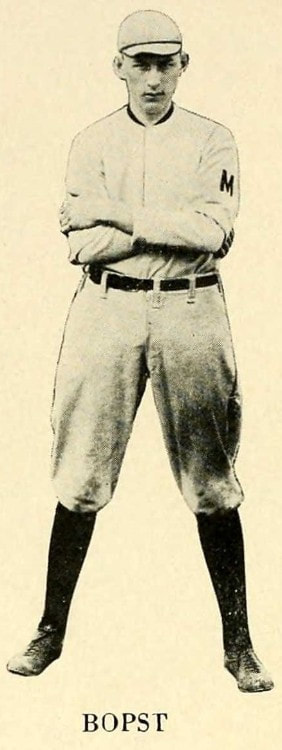

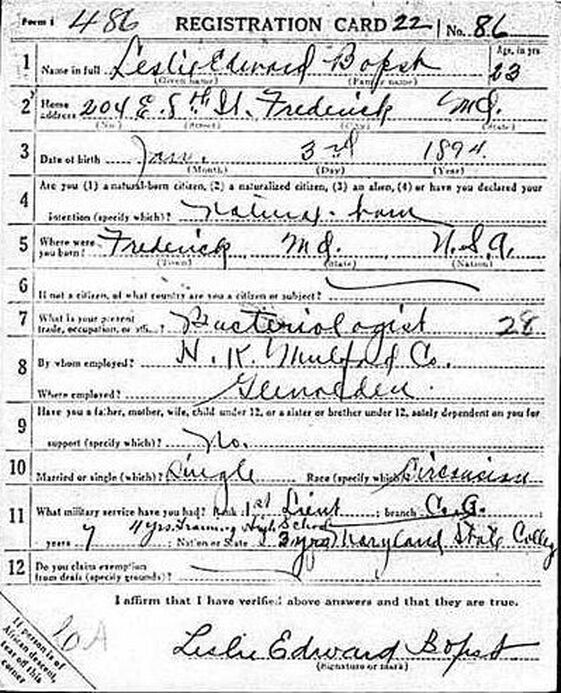

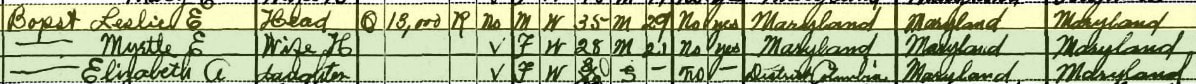

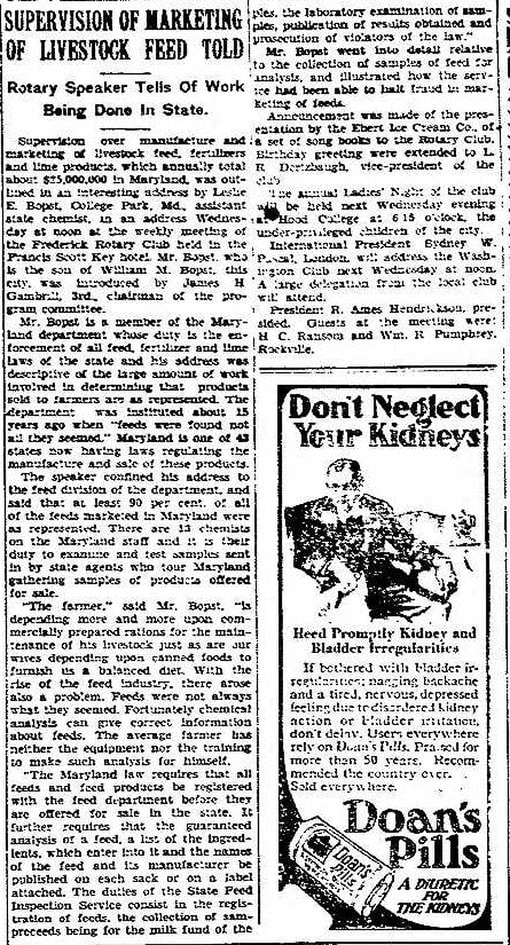

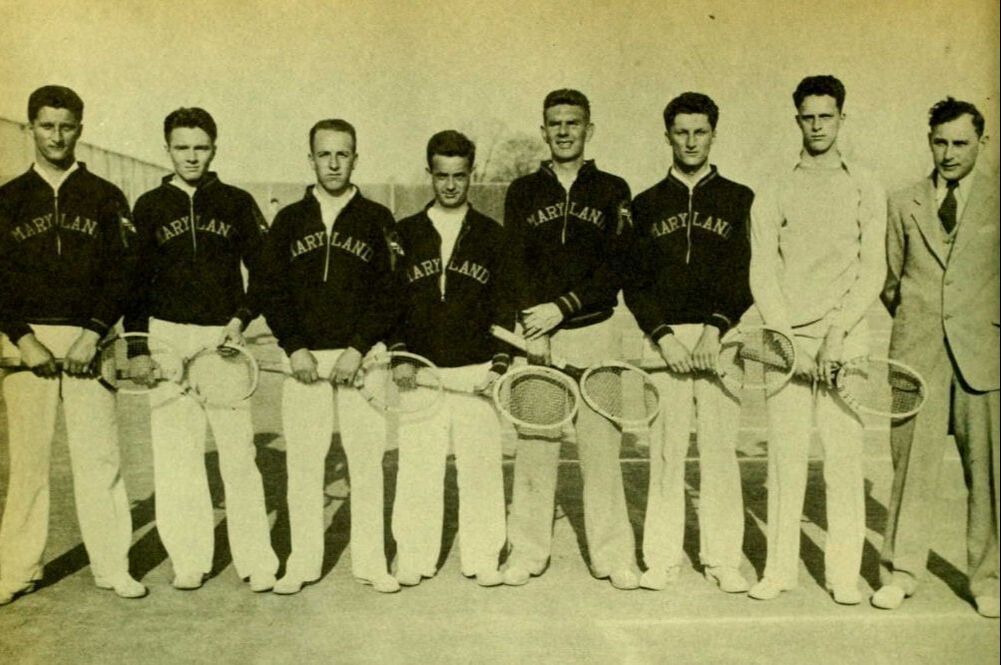

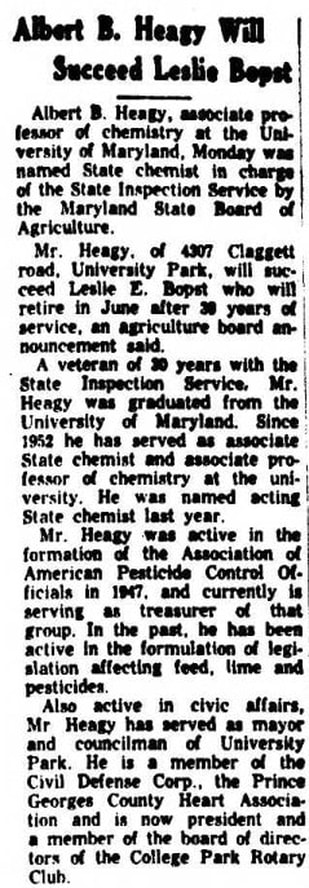

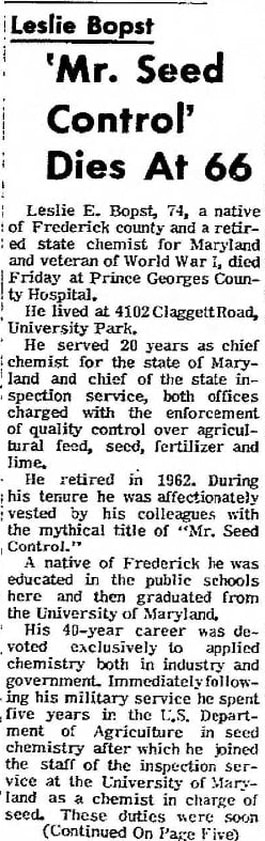

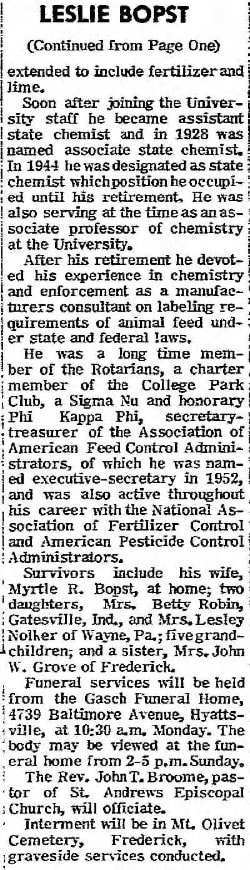

Moina Michael, who had taken leave from her professorship at the University of Georgia to be a volunteer worker for the American YMCA Overseas War Secretaries Organization, was inspired by the poem. She published a poem of her own called "We Shall Keep the Faith" in 1918. In tribute to McCrae's poem, she vowed to always wear a red poppy as a symbol of remembrance for those who fought in and assisted with the war. At a November 1918 YMCA Overseas War Secretaries' conference, she appeared with a silk poppy pinned to her coat and distributed twenty-five more poppies to attendees. She then campaigned to have the poppy adopted as a national symbol of remembrance. At the conclusion of our Mount Olivet Gazebo ceremony, we invited participants and onlookers in helping us spread red poppy seeds around the gazebo to further enhance our Never Forget Garden. We may not have poppies springing up in all other areas in our cemetery, but the flags (I referenced at the beginning) in a way represent the beautiful red flowers of Flanders Fields and battlefields everywhere our ancestors toiled. Thank you again to the volunteers who help us place these in advance of both Veterans Day and Memorial Day as its a big project. In five weeks on Wreaths Across America Day, these gravesites will also be covered with wreaths of evergreen symbolizing HONOR, RESPECT, and VICTORY. While on the subject of flowers, I can’t help but think of seeds and seasons. Of course, I could wax poetic for hours about the symbolism of both flowers and seasons and their relationship to life and death. One of the greatest principles in life is the concept of sowing seeds. This teaches us that if we give something, we can receive something in return. If we plant something in the proper conditions, water, feed and grow it, we can reap something bigger and greater. On Veterans Day, we honor all current and former members of the Armed Services. Our country's greatness is built on the foundation of your courage and sacrifice. Veterans Day calls out the sacrifices made by all service members in their decision to protect our freedoms by pledging their time, efforts, energies and expertise in addition to their lives. Mr. Seed Control With the flow of this story, it is obvious to me that at least one Mount Olivet veteran, in particular, needs to be recognized this Veterans Day weekend. He was a Frederick native and veteran of World War I, but of greater intrigue, his nickname was “Mr. Seed Control.” His name was Leslie Edward Bopst, a peculiar name, to go along with an even more peculiar nickname. There are 49 people with the Bopst moniker resting here in Mount Olivet, and I’m told the name is pronounced with a long O sounding similar to boast, but with a “p” sandwiched in the middle of that one-syllable word. Born January 3rd, 1894 to William Mortimer Bopst and Anna Mary (Brunner), Leslie spent his childhood at 8 East 8th Street on the outskirts of downtown Frederick in the early 20th century. His father started the Excelsior Dairy and ran the operation until 1920 at which time he sold it to Charles F. Rothenhoefer. Leslie had three sisters and was educated in local schools. He was a 1913 graduate of nearby Frederick Boys’ High School under the watchful eye of Professor Amon Burgee. Bopst busied himself with athletics and served as president of the Belles Lettres Literary Society. Fittingly, he also had charge of his high school’s floral committee. Leslie Bopst would go on to further his education at the Maryland Agricultural College, later to be known as the University of Maryland. He would graduate in 1916. While in school, Leslie, or Les as he was more commonly called, partook in athletics for the M. A. C. The Reveille yearbook of 1916 includes a picture of him as a senior, and another as a member of the college’s baseball team. The yearbook also makes mention of him having the rank of 1st Lt. in Company A. I believe this to be the college's Company A of an ROTC program as opposed to Frederick’s unit in the Maryland National Guard, which had its home at the former armory building standing on the southwest corner of N. Bentz and W. 2nd streets across from Memorial Park. Les would formally enlist in the US Army on September 27th, 1917. At this time, he found himself as a private in the 154th Depot Brigade. Twelve days later he was transferred to Company I of the 313th Infantry Regiment. Bopst would receive a promotion to the rank of corporal five weeks later. The following year, Les would be transferred on April 12th to a unique new wing of the United States Army. This was the Battalion Research Division of Chemical Warfare Service. The Great War was the first to utilize deadly and debilitating gasses thus necessitating such a division. Bopst would not be sent overseas to France, but would be based in Washington, DC. He would attain the rank of corporal for this entity one week before the end of the war, and would be honorably discharged one month later on December 10th, 1918. After completing his military service, Les embarked on a five-year career with the Department of Agriculture in seed chemistry. I found Les Bopst in the 1920 census living in an apartment building located on P Street in the nations capital. In this record, his occupation was listed as chemist, and his place of employment was labeled “private concern.” By 1922, his workplace would be the Maryland Agricultural College at today’s College Park. He joined the staff of inspection service at his alma mater as a chemist in charge of seeds with fertilizer and lime to fall under his purview shortly thereafter. On September 19th, 1923, our subject was a resident of Bethesda (MD) and married a fellow Bethesdan by the name of Myrtle R. Rabbitt. They would raise two daughters into adulthood. In 1928, Les would be named associate state chemist after spending a number of years as assistant state chemist. While a faculty member at the college, he naturally taught chemistry. I also learned that he was an advisor to Sigma Nu fraternity, and also coached the college’s tennis team. In 1944, Les Bopst was named state chemist, a position he would hold until his retirement 18 years later in 1962. His career at the college spanned 40 years. Bopst spent his remaining years as a corporate consultant, and remained active with Rotary and the College Park Club of which he was a charter member. He and Myrtle lived in the College Park-Hyattsville area and doted on the seeds of their personal life, two daughters and five grandchildren. Leslie E. Bopst died on December 20th, 1968. He would be buried in Area L/Lot 160, located behind our Key Memorial Chapel, along the drive that leads west to Confederate Row. Wife Myrtle would join him here in late May of 1990. Our last phase of the World War I Memorial Gazebo includes necessary fundraising for the addition of three, tabletop-style interpretive exhibits to be placed around the structure. These will tell the stories of the Never Forget Garden and Memorial Gazebo, along with highlighting the lives of some of the WW I veterans buried here, including individuals killed on the battlefield and others who fell victim to the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918. Please help us if you can.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed