|

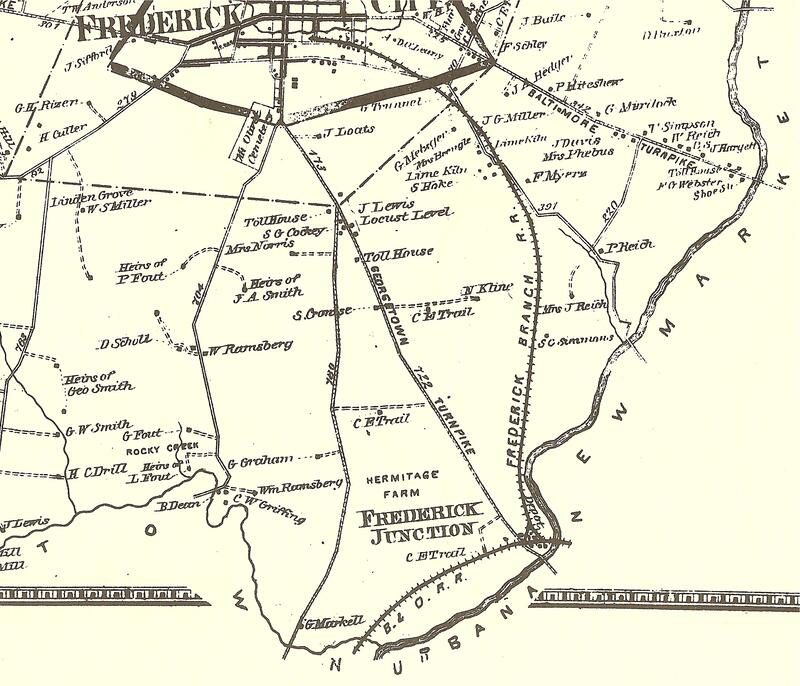

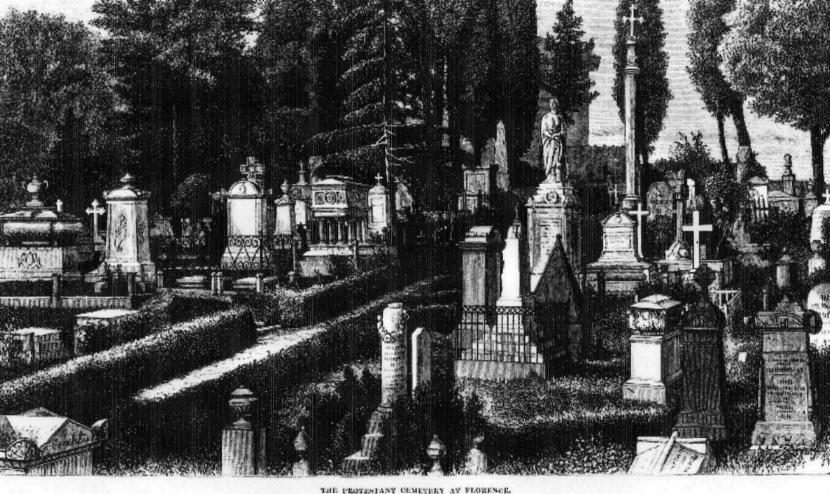

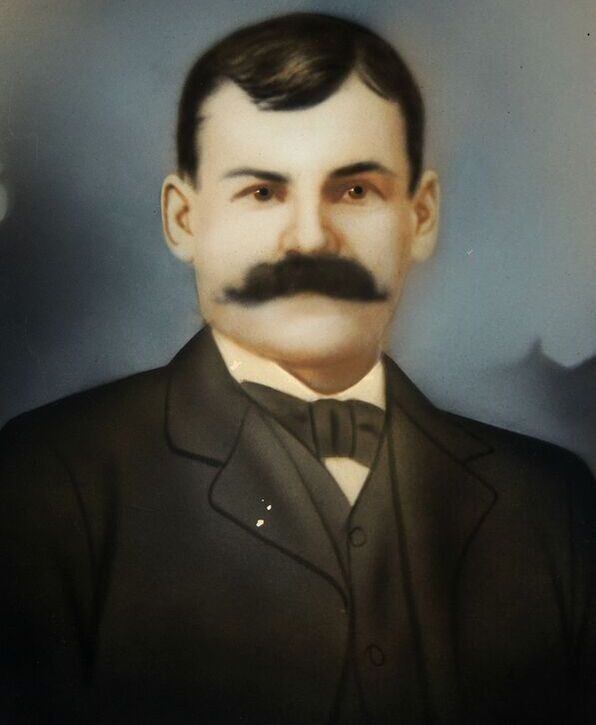

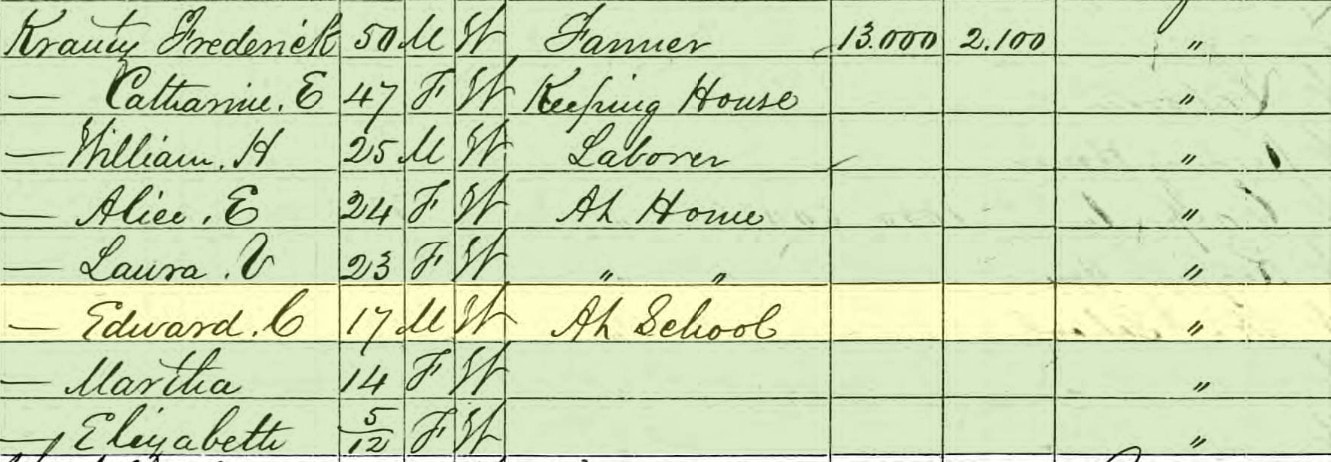

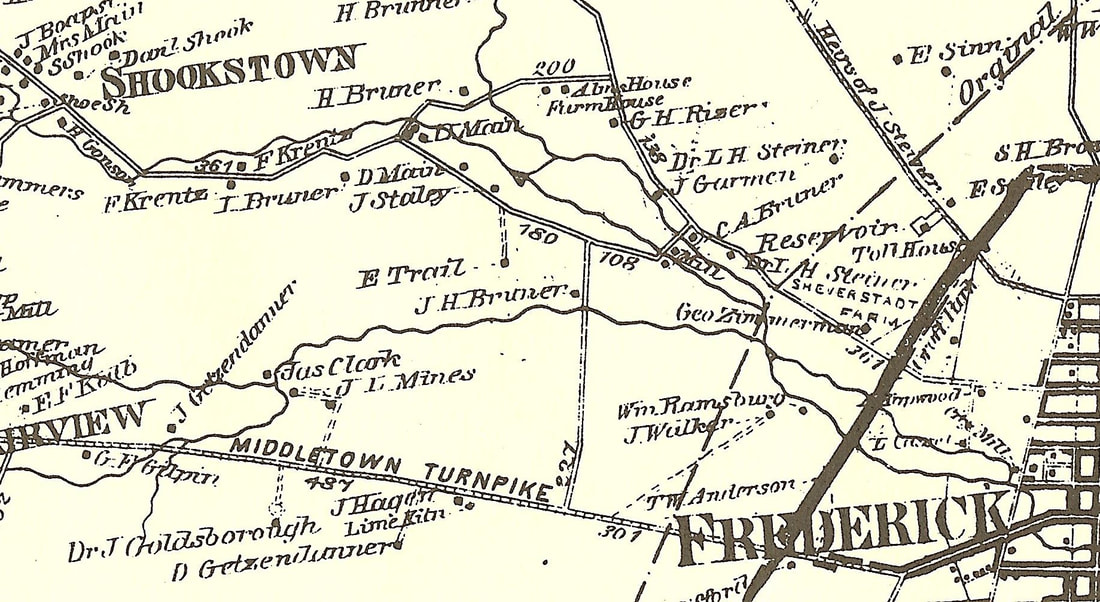

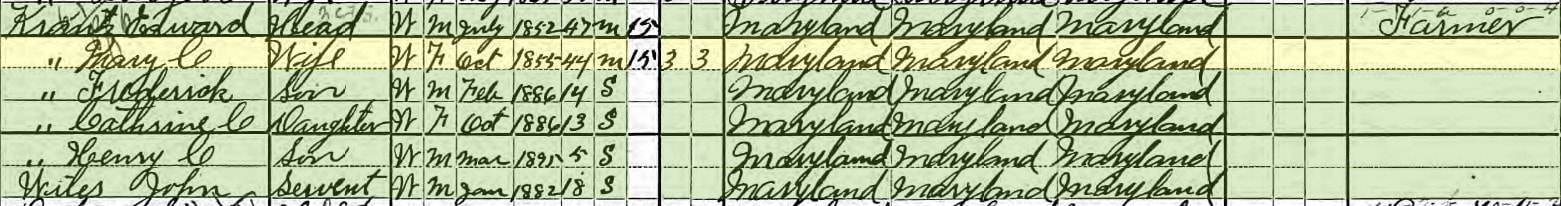

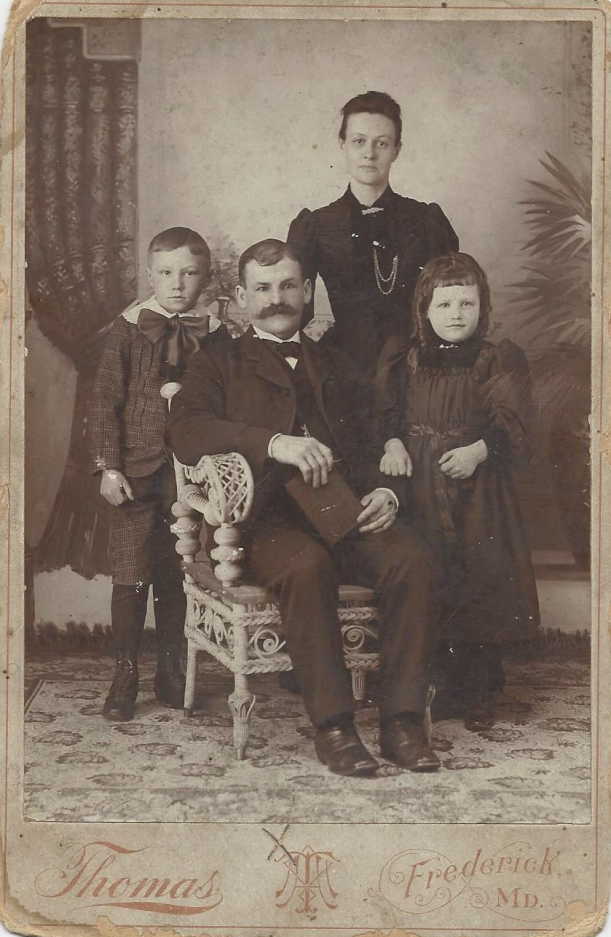

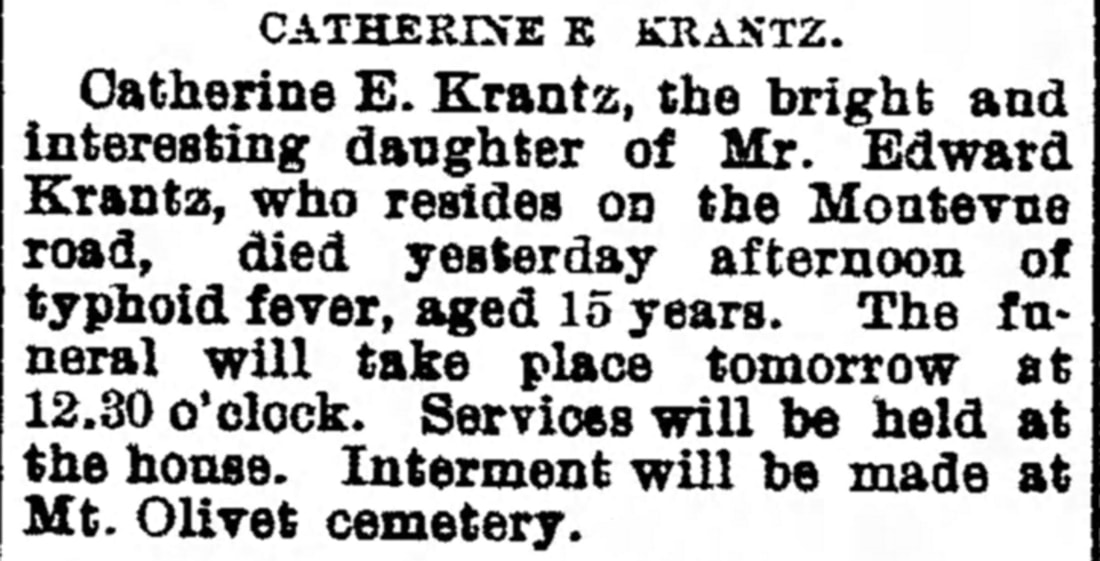

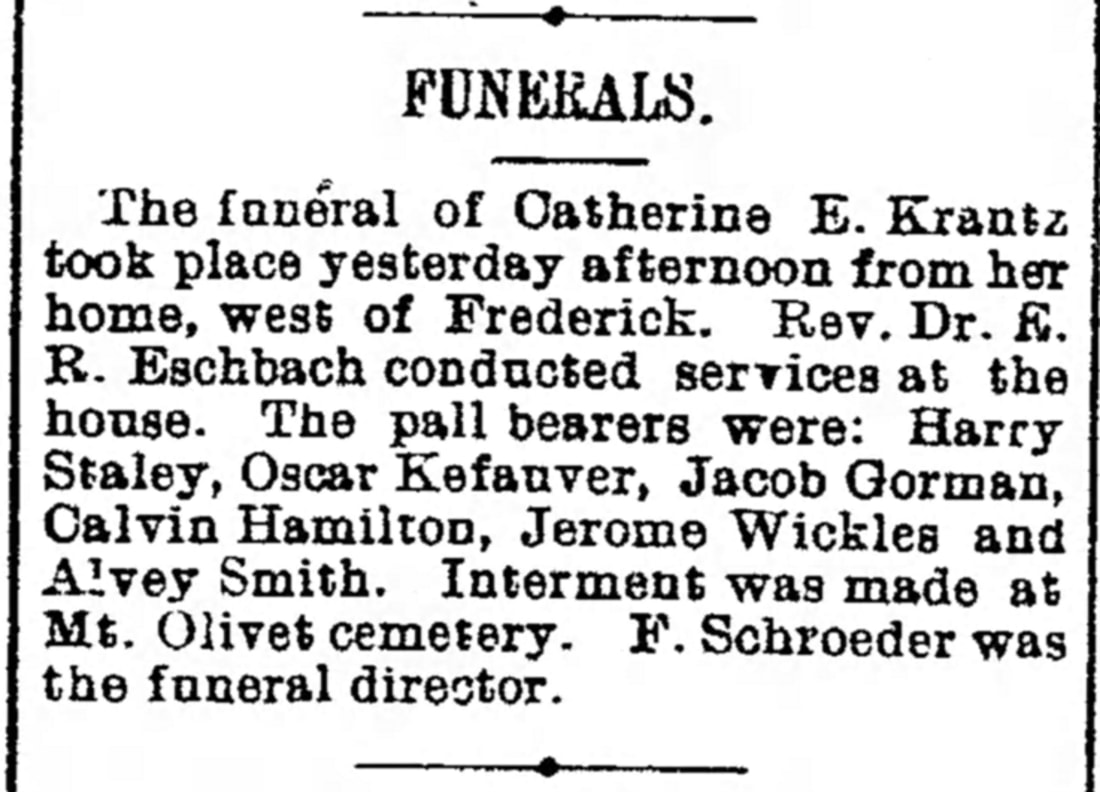

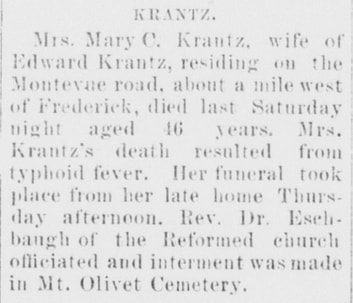

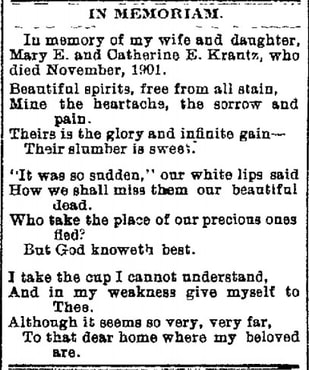

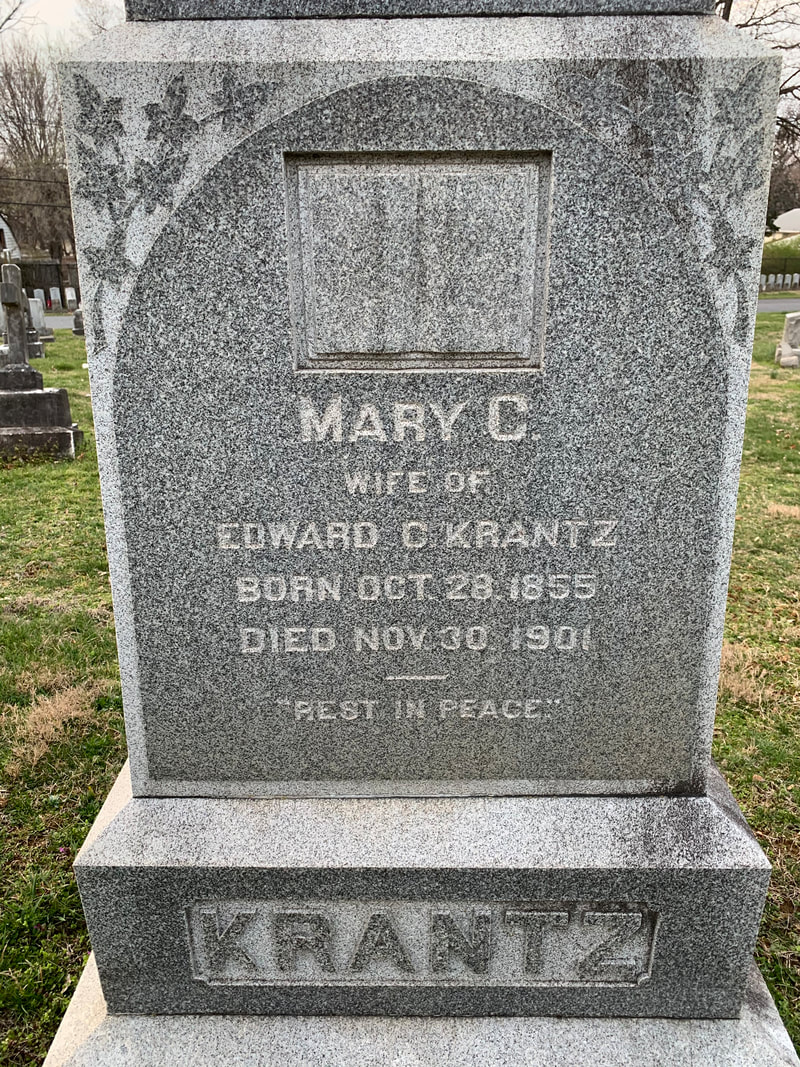

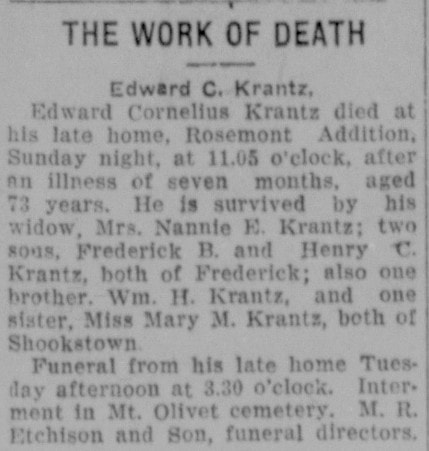

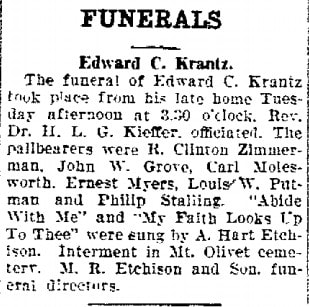

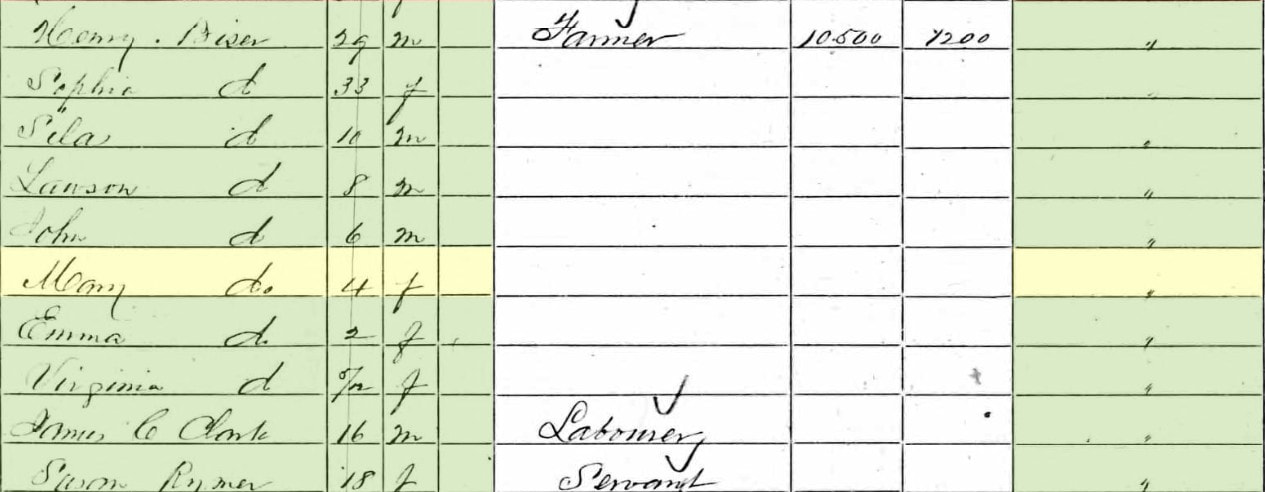

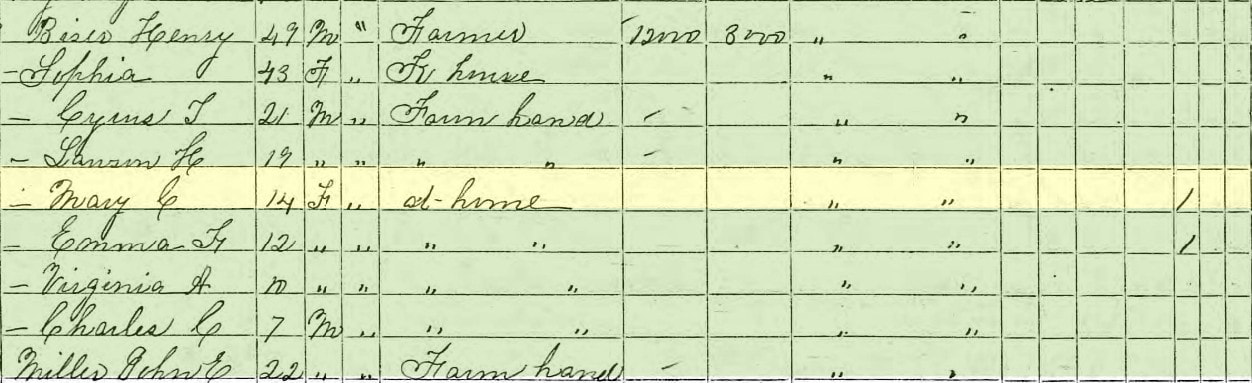

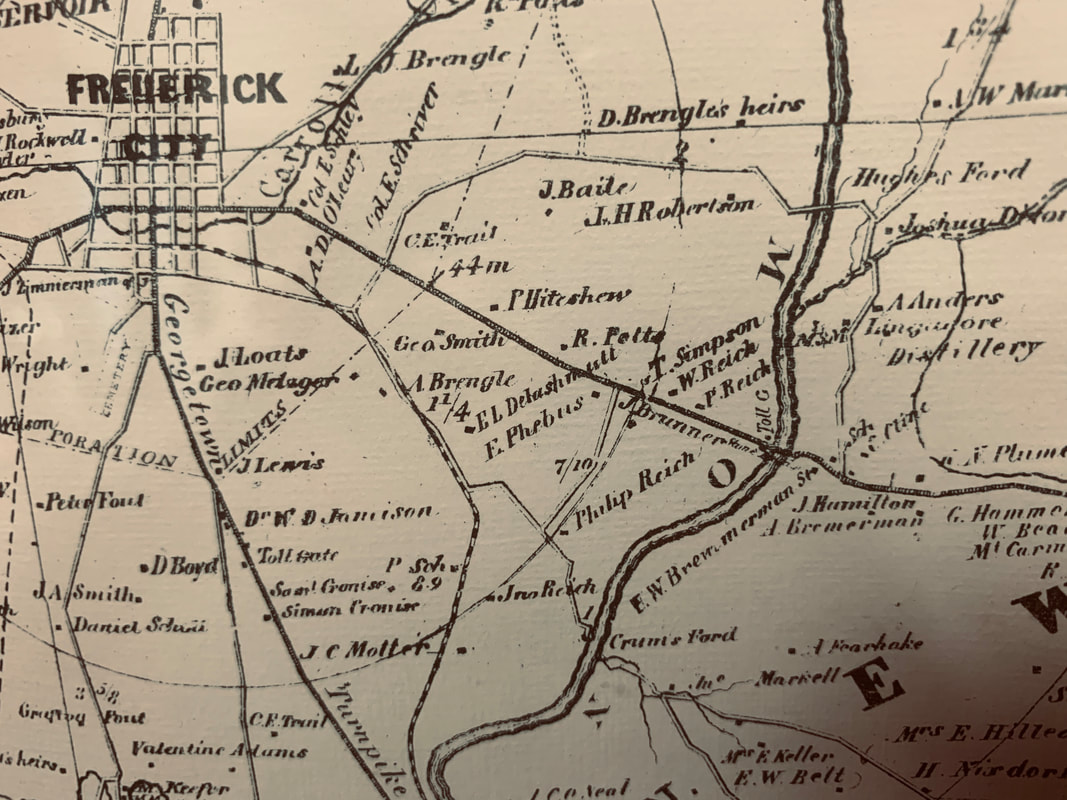

A picturesque scene can be found in Mount Olivet’s Area G. Standing high above all surrounding others is the funerary monument of Edward C. and Mary Catherine Krantz. The towering gravestone was erected in the waning years of the Victorian Era (1832-1903) and displays the high ornamentation that characterized that time period. The era was an eclectic period in the decorative arts with several styles—Gothic, Tudor, Neoclassical—vying for dominance. This was true in architecture, furniture, and, of greatest interest here, the funerary arts. In cemeteries, gravestones became taller, embellished and sentimental. This particular grave monument on Lot 156 features a shrouded woman with arms folded across her chest, gazing upwards toward the heavens in what appears to be prayer and contemplation. The white marble statue sits atop a polished, granite base. Altogether, the work stands roughly 10 feet in height. The monument itself is a paean to Victorian design—possessing an air of triumph, symbolism and sentimentality. Upon closer inspection, one will notice that the woman has a chain draped around her neck which extends down and across her chest to an upright anchor at her side. One of the anchor’s spades is partially concealed under the rear of her robe. Look carefully and you will see that the chain is actually depicted as being broken at the point it reaches the eye-hole atop the anchor. Anchors abound on tombstones throughout Mount Olivet. In some cases, they denote the sailing profession of the deceased as is the case with that of Captain Herman Ordeman (1812-1884) of whom I published an earlier story back in late summer of 2017. More so than not, it is the religious/Christian symbolism of the anchor that comes into play with these grave markers as we have a large amount featured throughout the grounds. The gravestone of the father of the earlier mentioned Edward C. Krantz actually utilizes the anchor-cross motif in an adjoining lot (Area G/Lot 158).  As a religious symbol, anchors were used in antiquity as secret crosses and denoted hope, and still do today. Within the books of the New Testament, the passage in the Epistle to the Hebrews 6 states: “Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast, and which entereth into that within the veil.” A translation elaborates on this passage attributed to St. Paul, saying: “So God has given both his promise and his oath. These two things are unchangeable because it is impossible for God to lie. Therefore, we who have fled to him for refuge can have great confidence as we hold to the hope that lies before us. This hope is a strong and trustworthy anchor for our souls. It leads us through the curtain into God’s inner sanctuary.” The three theological Virtues (human forms that represent core Christian values) include Faith, Hope and Charity, and the figure of Hope almost always has an anchor with her. Therein lies the allegorical statuary category that this gravestone can be classified within--the Statue of Hope. These were commonly erected in the Victorian era and believed to be popularized by the Statue of Liberty's dedication in 1886. A female, typically shown wearing Roman Stola and Palla garments, stands with one arm resting on, or holding, an anchor. Often, the opposite arm is raised with the index finger of the hand pointing towards the sky, symbolizing the pathway to heaven. Holding one’s hand over the heart symbolizes faith and devotion. In the case of the Krantz monument, the woman has her hands folded in a show of complete devotion and subservience. Statues of Hope generally feature elements of a broken chain attached to the anchor, or sometimes hanging from the neck symbolizing the cessation of life. Many statues feature the maiden donning a “Crown of Immortality” made of flowers or stars. The flower or star on the top of the forehead, usually on a crown or diadem, and represents the immortal soul. Prior to this, other images such as Saint Philomena (patron saint of infants, babies and youth) whose authorization of devotion began in 1837 and Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen's Goddess of Hope statue sculpted in 1817, displayed similar characteristics. One of the earliest signed Statue of Hope memorials was carved by Odoardo Fantacchiotti in 1863 for the grave of Samuel Reginald Routh of England in the Protestant Cemetery of Florence, Italy. Another variation was completed earlier in 1791 with the Custom House, Dublin Ireland in which a 16-foot tall statue of a female resting on an anchor is atop the building’s iconic dome. This statue has been called both the Statue of Hope and the Statue of Commerce. The Krantz Family So just who were these “hopeful” people that left us with such a beautiful lasting legacy in the form of a statuary monument atop their gravesite? Thanks to a number of sources, I had a relatively easy time of learning their vital statistics, life stories, and causes of death. An extra bonus came with accessibility to images of the couple courtesy of polished embellishments to both an Ancestry.Com Family Tree and Find-a-Grave pages by family historian Patrick Aaron Steward. (Thanks Patrick!) The History of Frederick County by T.J.C. Williams and Folger McKinsey includes an elaborate biography on Edward Cornelius Krantz. Mr. Krantz was born on July 3rd, 1852 on a small farm and grist mill located along Linganore Creek in the New Market District. He was the son of Frederick J. and Catherine E. (Stup) Krantz. Edward’s grandfather (John Dietrich Krantz 1820-1890) had come to this country from Germany in his youth and worked as a shoemaker. Son Frederick took up the occupation of miller and worked at various locations around Frederick. In 1869, Edward’s father (the above-mentioned Frederick) purchased a fine farm of 142 acres, located two and a half miles northeast of Frederick City on the Shookstown Pike. Here’s where we find our subject living in the 1870 census as he spent his childhood learning his life’s profession of farming. After his father’s retirement, he and brother William managed the home farm for three years. Edward would go on to rent another farm that their father had acquired in 1879 on the Buckeystown Pike and located a few miles south of Frederick. The young man would purchase and make this his home until 1901. Edward's brother, William, and sisters farmed the old family homestead bisected by Shookstown Road (between Willowdale and Waverly drives). The remaining structures were recently demolished to make way for the Gambrill View housing subdivision. When the farm sold out of the Krantz family in 2001 (to a developer from Leesburg (VA)), it was one of the last remaining large farms operating with the Frederick City limits. Edward C. Krantz married Mary Catherine Biser, born October 28th, 1855 in Middletown. She, like her husband, had been raised on the family farm belonging to her parents, Henry and Sophia Routzahn Biser. They married in 1885 and had three children: Frederick Biser Krantz (b. 1886), Catherine Elizabeth Krantz (b. 1887) and Henry Cornelius Krantz (b.1895). Of wife Mary Catherine, Williams’ reads: “She was a devoted helpmate in his (Edward’s) labors.” The family attended the Evangelical Reformed Church of Frederick and made their domicile into what Williams’ states as “an elegant farm of 140 acres.” The author stated Mr. Krantz to be “one of the highly successful agriculturalists of the Frederick District. "The property is west of the Buckeystown Pike (today's MD route 85), north and east of Crestwood Blvd, surrounding Westview Drive. Fortunately, the Krantz farm stayed pretty much intact, with the exception of some road right-of-ways, from before 1859 through 1986. I know this takes us a bit off subject, but I was fascinated to see the ownership of this property over history before and after the Krantz family. This info comes courtesy of my awesome research assistant, Marilyn Veek, and includes other residents of Mount Olivet who I have bolded (names) for your reading pleasure. These include: Abraham Adams, Valentine Adams (1799-1860 in Area H/326) Abraham's son, John Henry Nelson (1820- 1870 in Area H/326) Valentine's son-in-law, Richard and Caroline Kemp Lamar (1815-1879 in Area D/53), Robert Guy Lamar (1848- 1885 in Area Q/45) son of Caroline. Here are a couple of descriptions of the farm as it existed in the 1860s, from chancery court records: It had a 2-story brick house, barn, stable, carriage house, wagon shed, smoke house and other out buildings including a large quarter for servants detached from the house. It had two pumps of water, one near the house and the other near the barn. The soil is limestone, quality unsurpassed; improvements consist of a 2-story brick house of 9 rooms and kitchen, barn, stabling, shedding, corn house, ice house, a first-class farm. There is also a tenant house which has recently been repaired at great expense. Farm lately used as a dairy farm for at least 30 cows; has fine water, milk house, fine orchard of various fruit.  1873 Titus Atlas map showing Evergreen Point area below Frederick. The Krantz Farm on Buckeystown Pike can be denoted in the vicinity of G Graham shown on mapto the immediate west of Hermitage Farm. Of special interest is the fact that the author feels that the farm was tenanted by George Graham (b. 1819), an African-American who appears with his family in the 1850 and 1860 census records. He could have interesting tiies to the Vincindiere family who began Hermitage Farm or to the Grahams of Rose Hill Manor (daughter and son in law of Thomas Johnson, Jr.) Everything seemed to be going well for the Krantz family until late 1901 when bitter misfortune would rear its ugly head. In my curiosity, I became determined to learn more about this malady that killed many in the time before modern medicine and a known vaccine. Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a bacterial infection due to a specific type of Salmonella that causes symptoms that may vary from mild to severe, and usually begin 6 to 30 days after exposure. It likely starts from ingesting contaminated food or water. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several days. A critical added danger of Typhoid is its spread to others by way of eating or drinking food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person. Family members were prime targets. The best they could do was wash hands meticulously—certainly more difficult to accomplish in the days before running water. In the desperate nursing of the newly turned 14 year-old daughter, a hopeful and devoted mother would fall prey herself to the dreaded illness. Edward had lost his teenage daughter and 46 year-old wife within that fateful month of November 1901. He would erect the Statue of Hope memorial to these two exceptional women of his life. The monumental losses suffered could have prompted him to move back to his earlier home area north of Frederick. He purchased a 185-acre farm on the old Montevue Pike (today’s Rosemont Ave), and erected a two-story dwelling, a bank barn and other buildings, at the same time improving an existing house on the land. The existing house was none other than Schifferstadt, one of Frederick's earliest dwellings. The property consisted of land stretching westward to Baughmans Lane, eastward to West 7th Street, and to Fort Detrick. My home in the Villa Estates neighborhood (between US15 and Military Road) was even part of the Krantz farm. Edward married again two years later in late 1903. His second wife, Mamie E. Schaeffer was the daughter of Frederick druggist David L. Schaeffer and wife Elizabeth. Edward Krantz would continue overseeing his farm properties and stayed active in town and religious affairs. He died on March 21st, 1926 and was buried beside his beloved daughter and exceptional helpmate—one who, like many other devoted women, sacrificed her own life in the unselfish care of an ailing child. Saint Philomena surely interceded on her behalf then, and in the form of a statue of Hope that has kept vigilant watch over the women's mortal remains ever since. As for the farms of Edward C. Krantz, the Buckeystown Pike farm was conveyed to his sisters when he re-located north of Frederick City (after the deaths of his wife and daughter). The Krantz sisters sold it to Henry Krantz, Edward's son. Henry sold it to Gerrit and Elizabeth Lewis Peters (1898-1989 in Area E/Lot 89). The Peters sold it to Tyler Gatewood Kent, who sold it to Martha Prior. She sold it to her son Howard Anderson Prior (1905-1985 in Area FF/252), who eventually sold it to the trustees of Princeton University in 1984. They sold it to Westview Associates Ltd Partnership in 1986.

And here is the former Edward C. Krantz farm today:

2 Comments

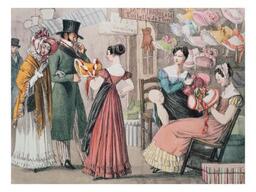

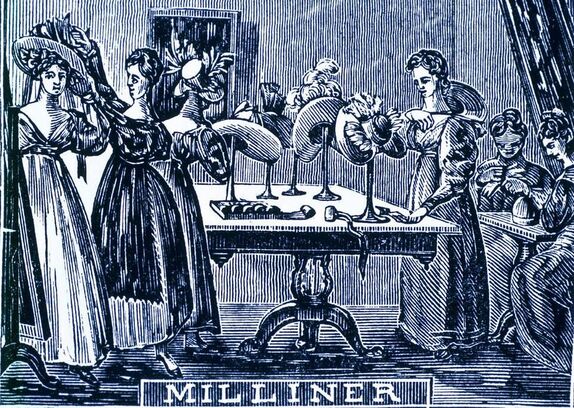

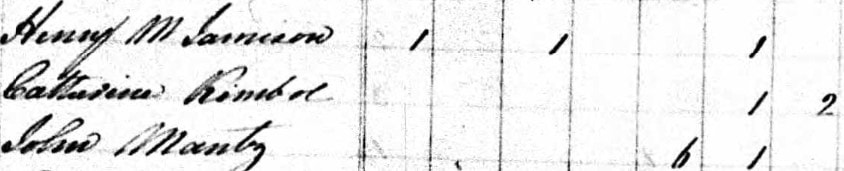

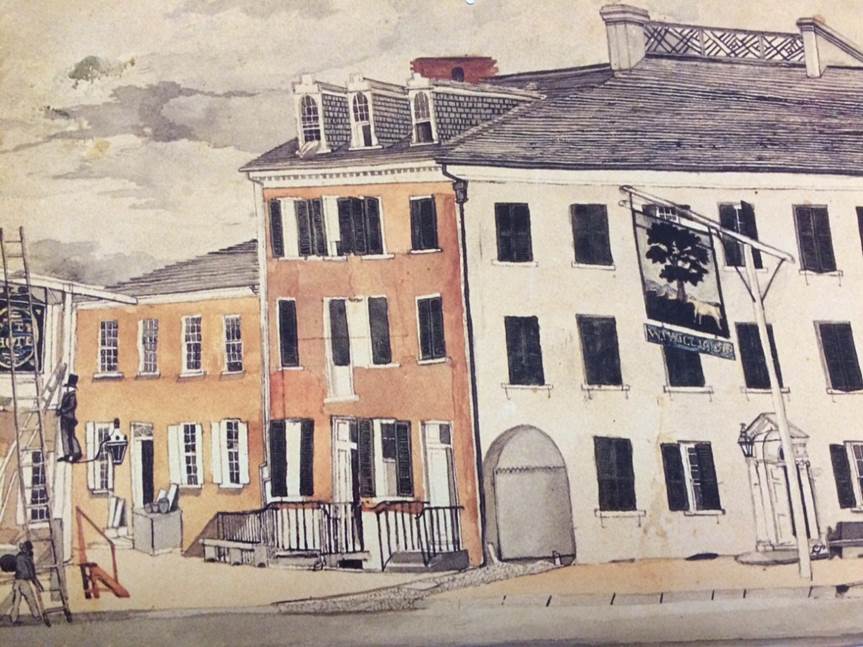

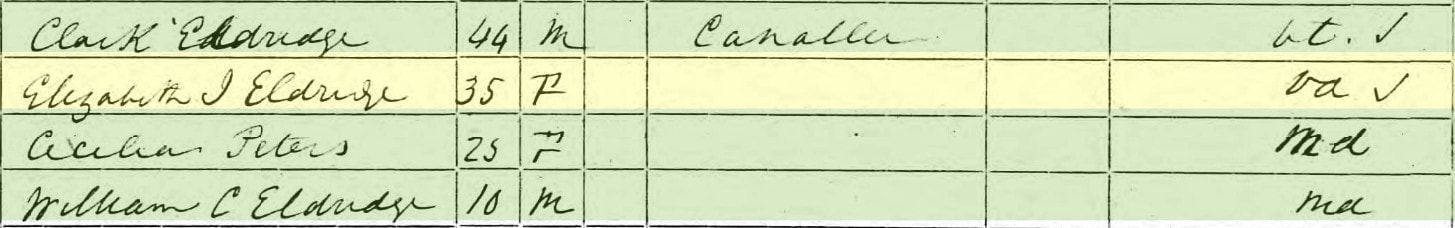

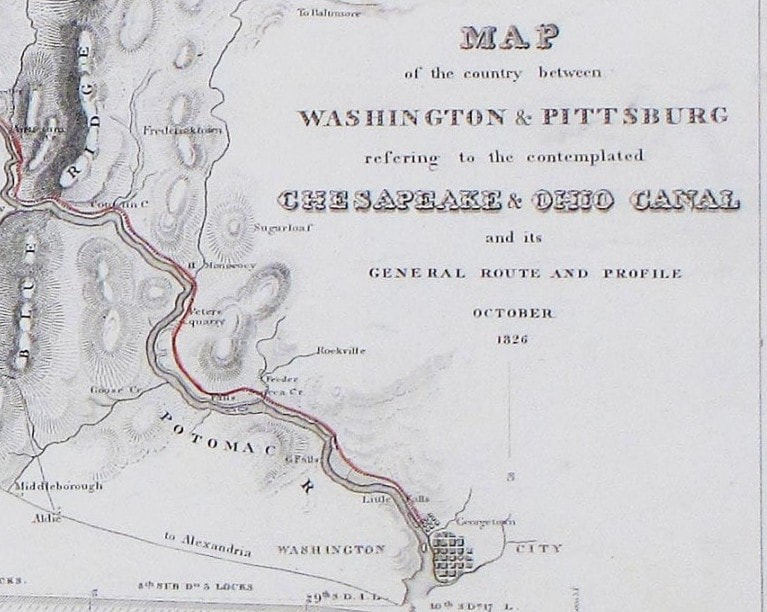

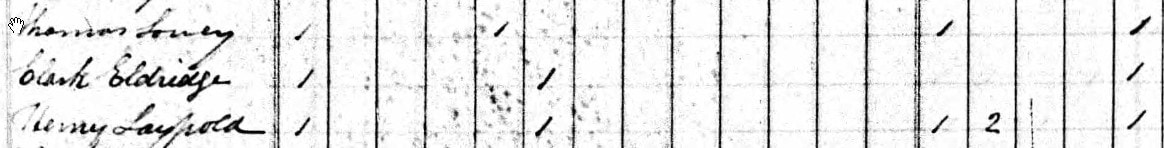

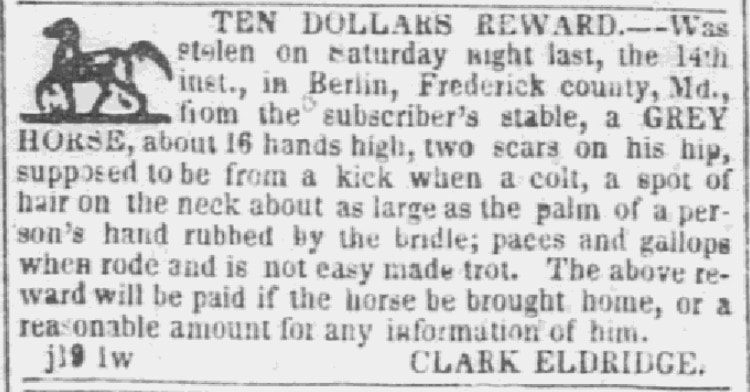

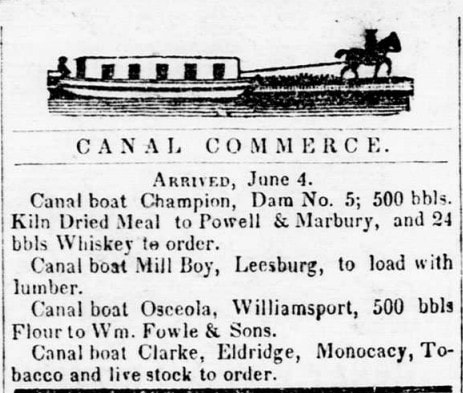

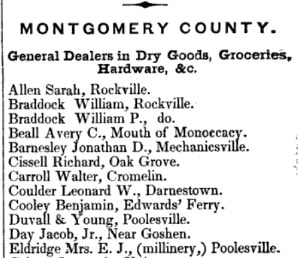

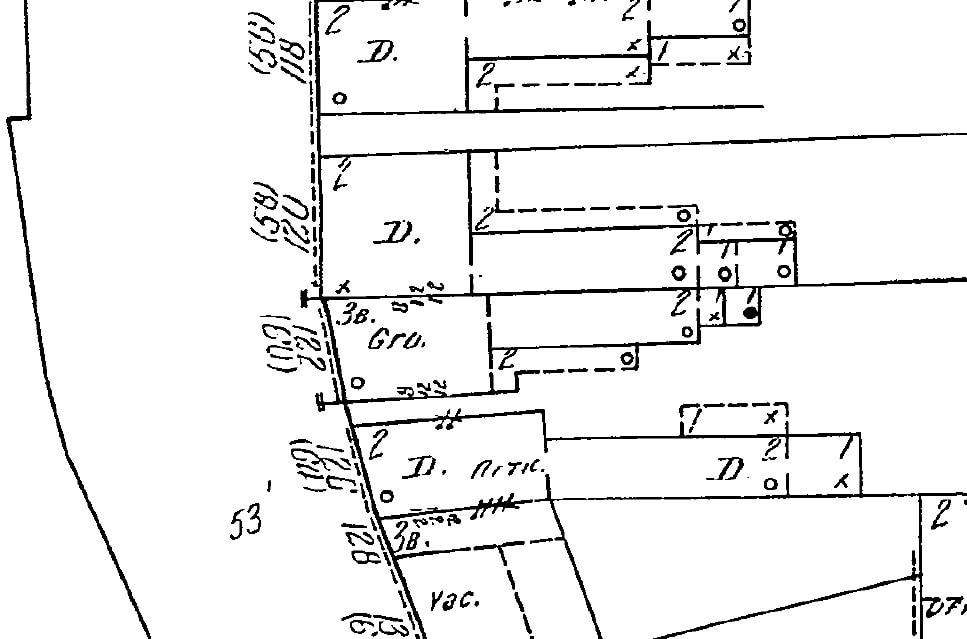

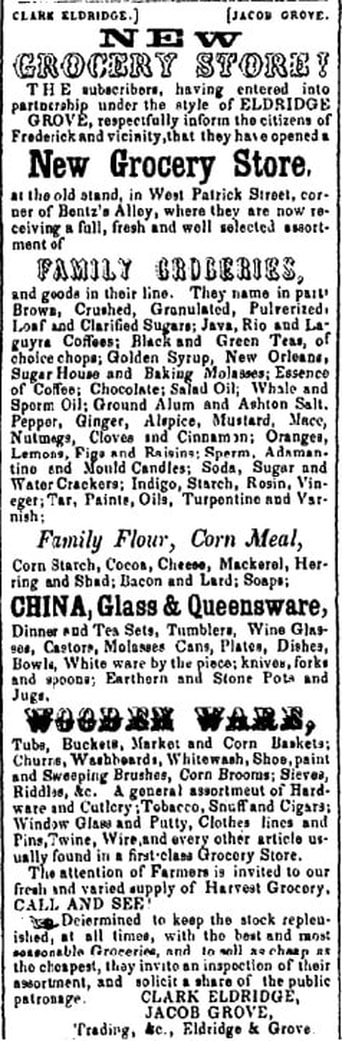

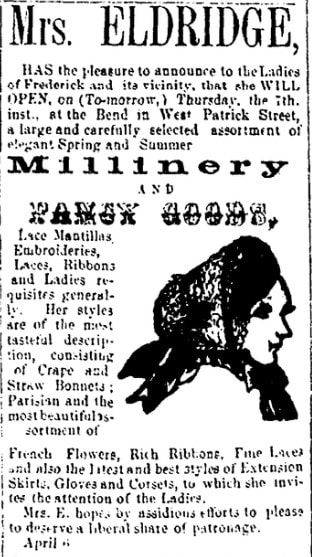

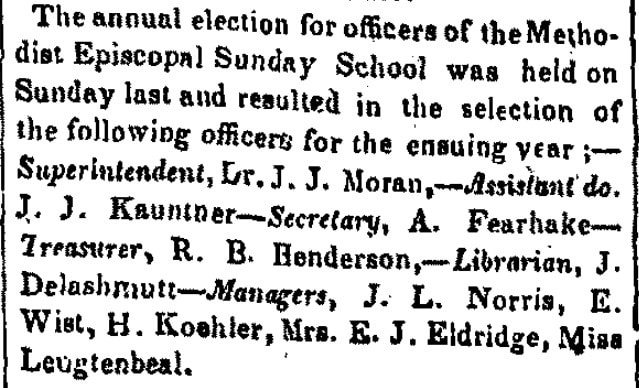

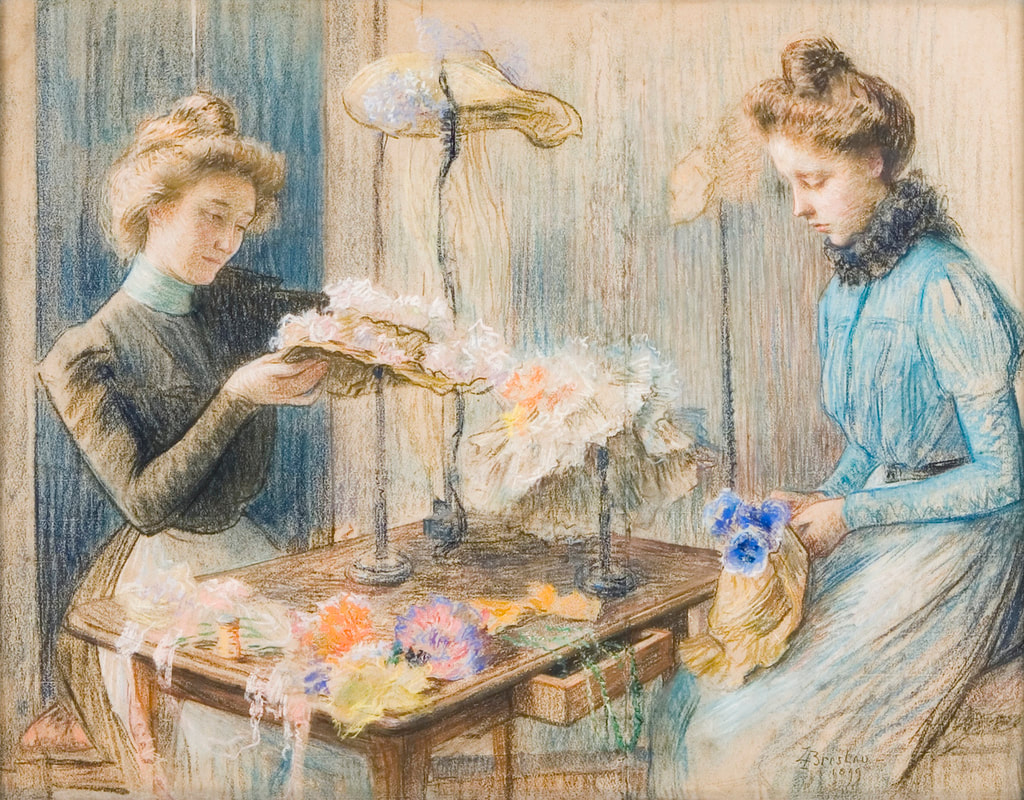

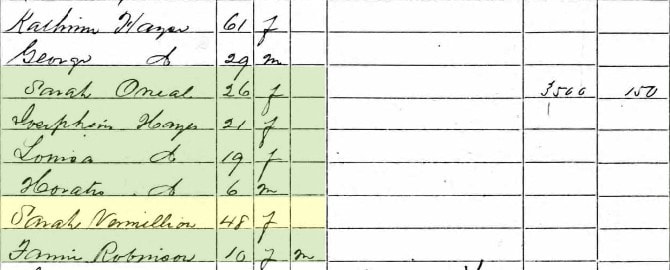

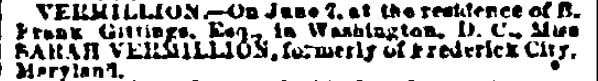

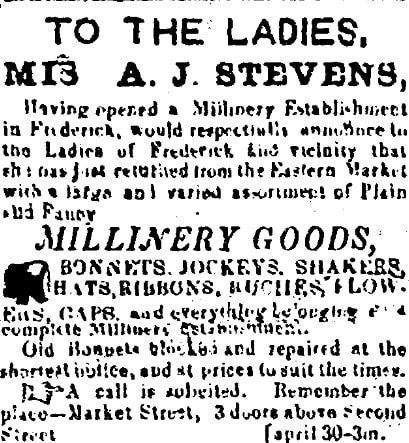

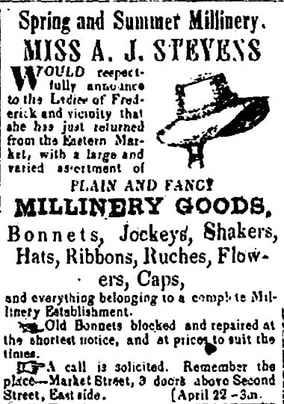

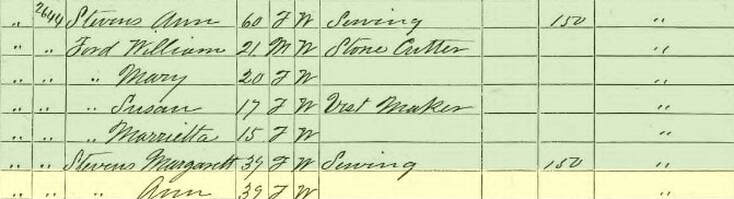

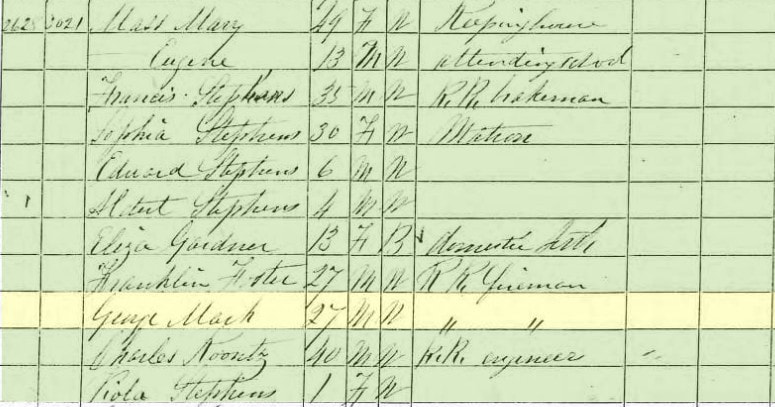

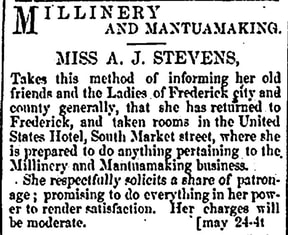

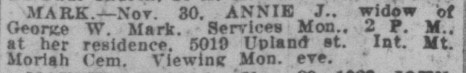

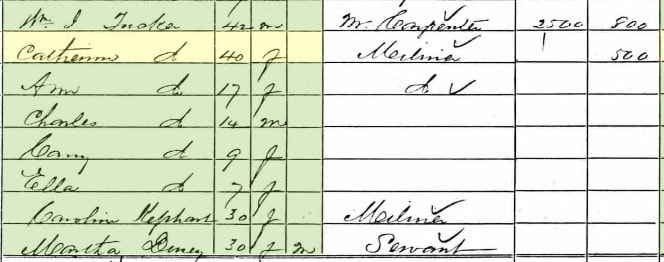

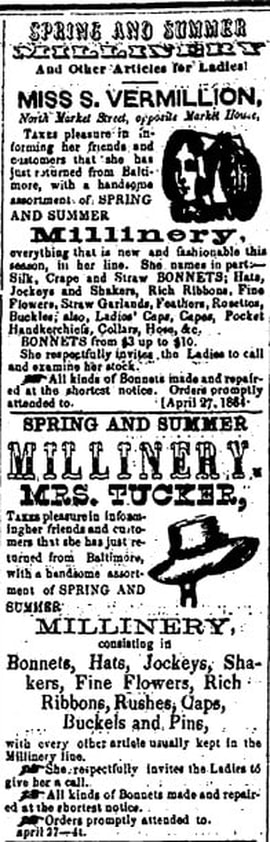

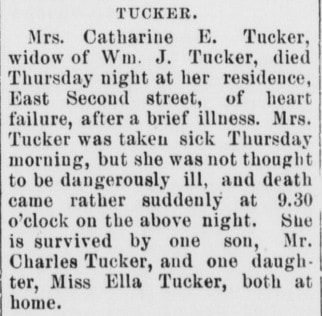

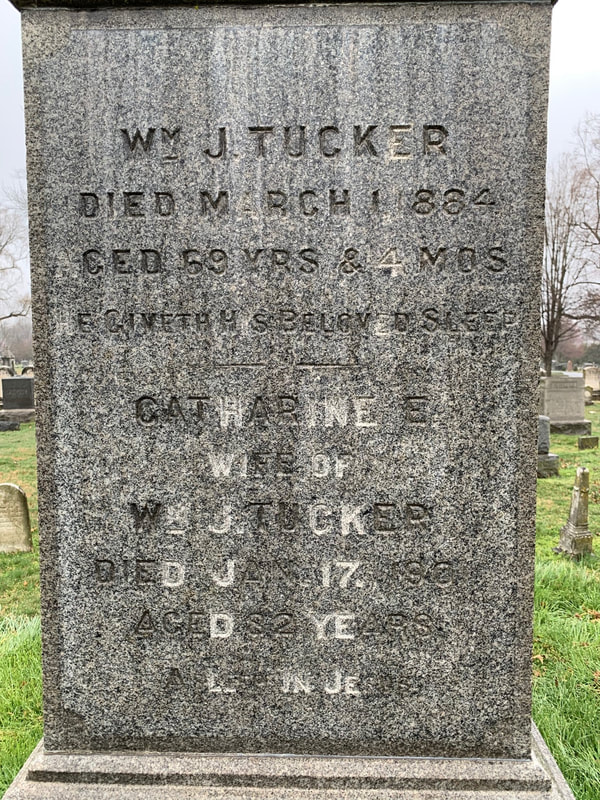

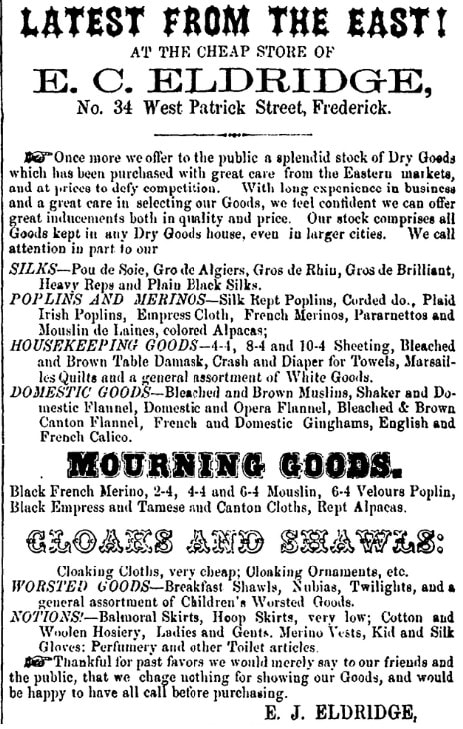

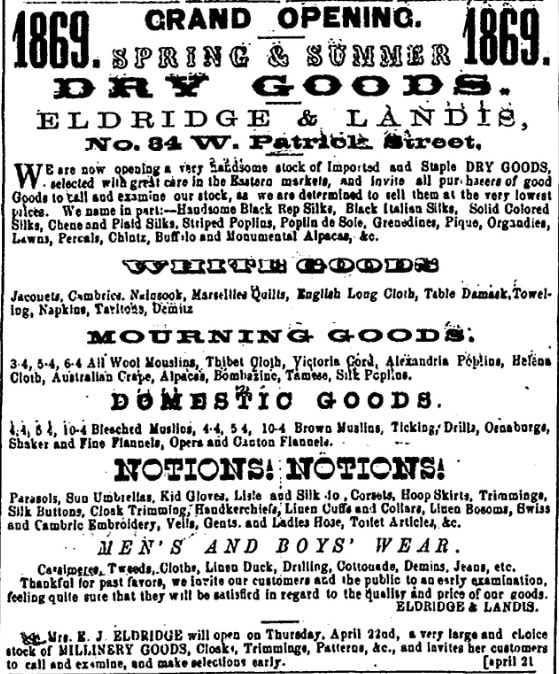

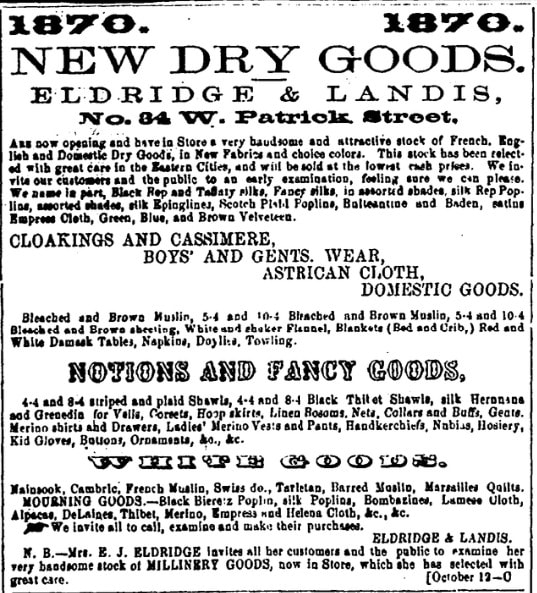

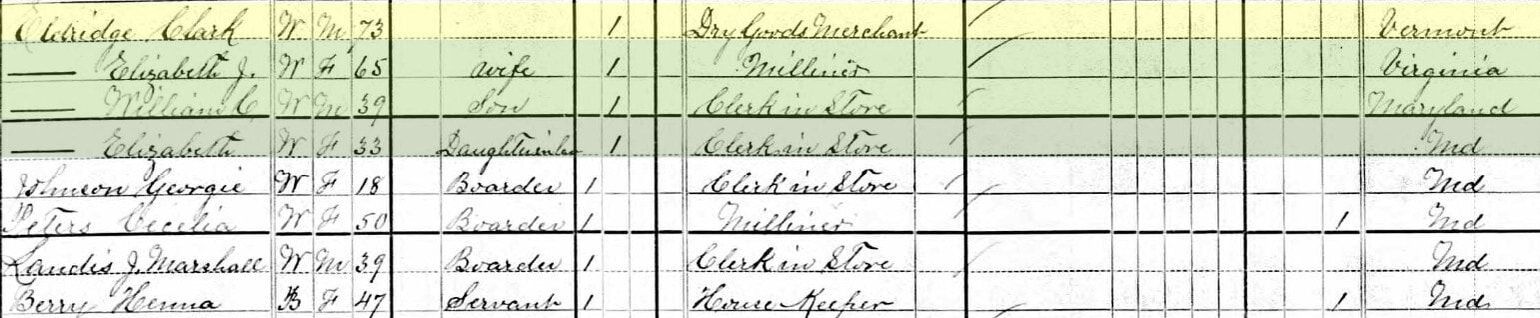

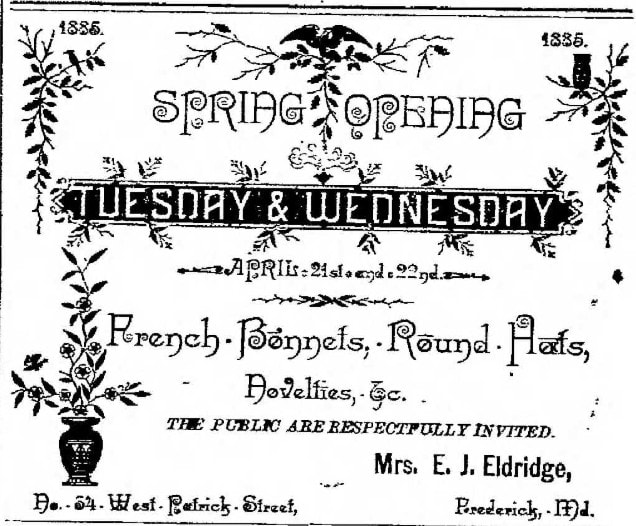

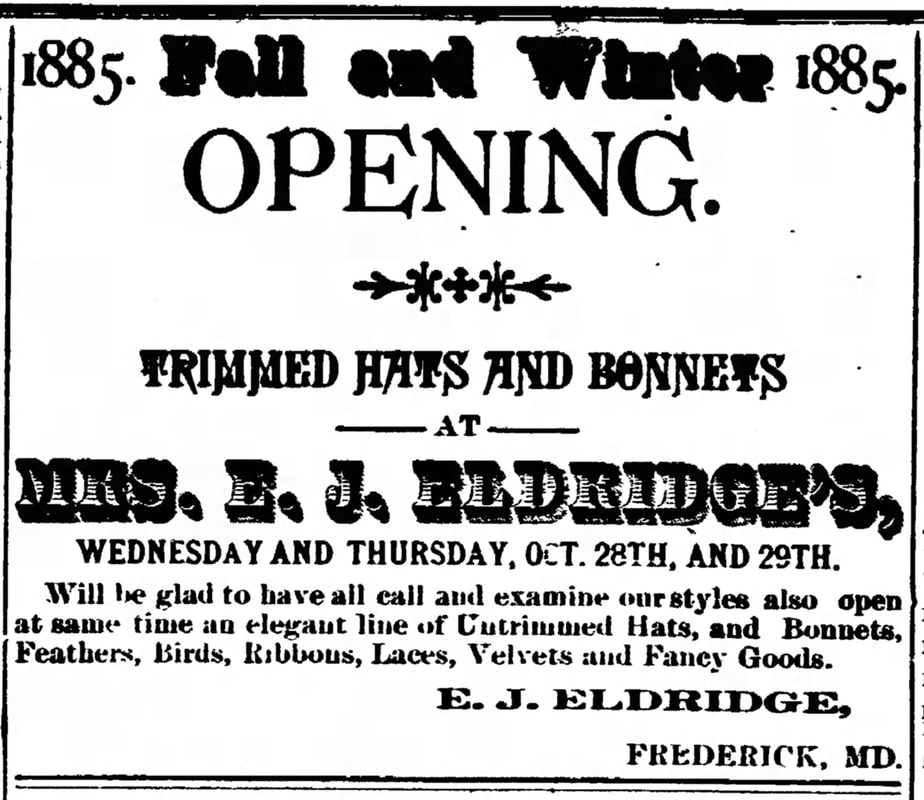

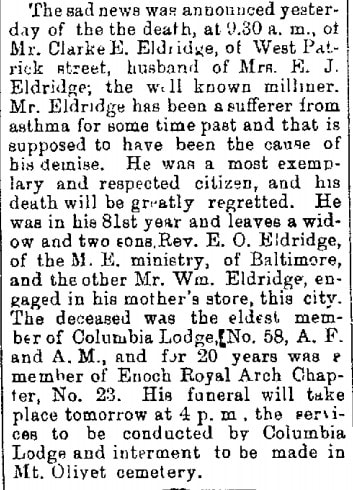

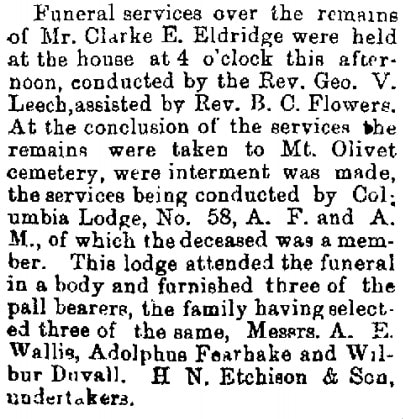

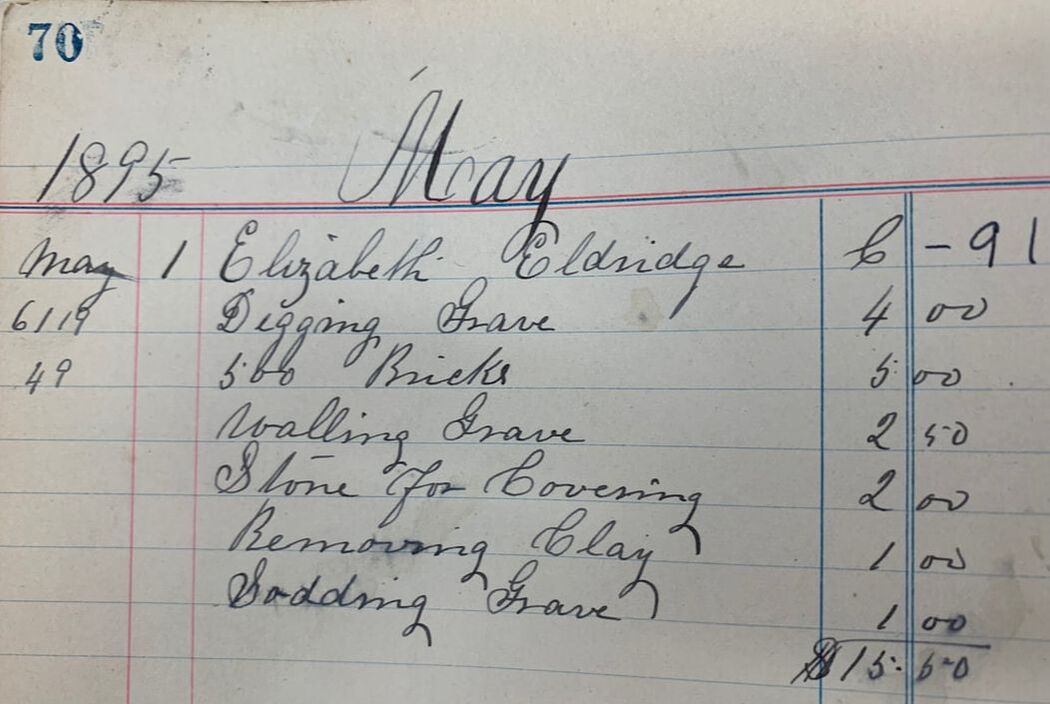

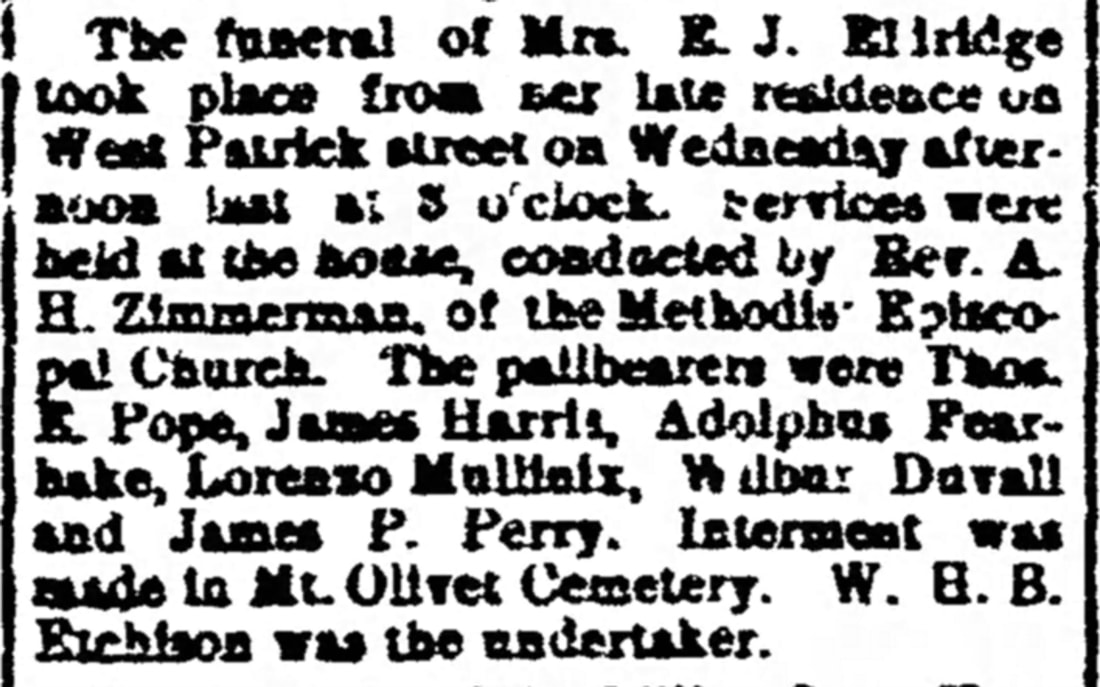

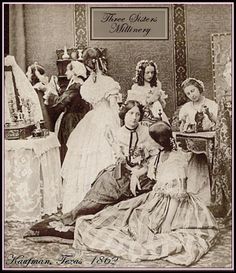

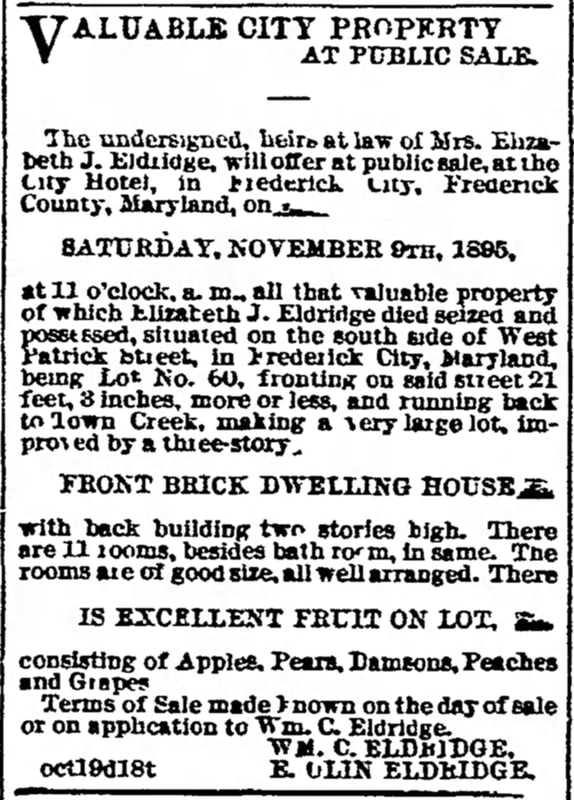

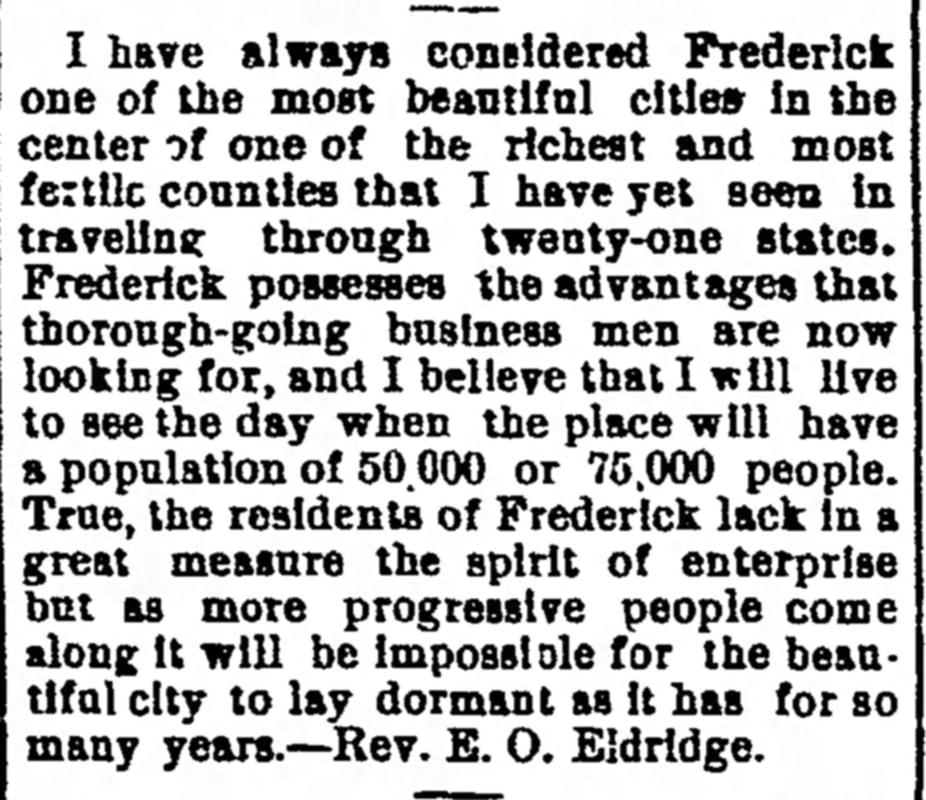

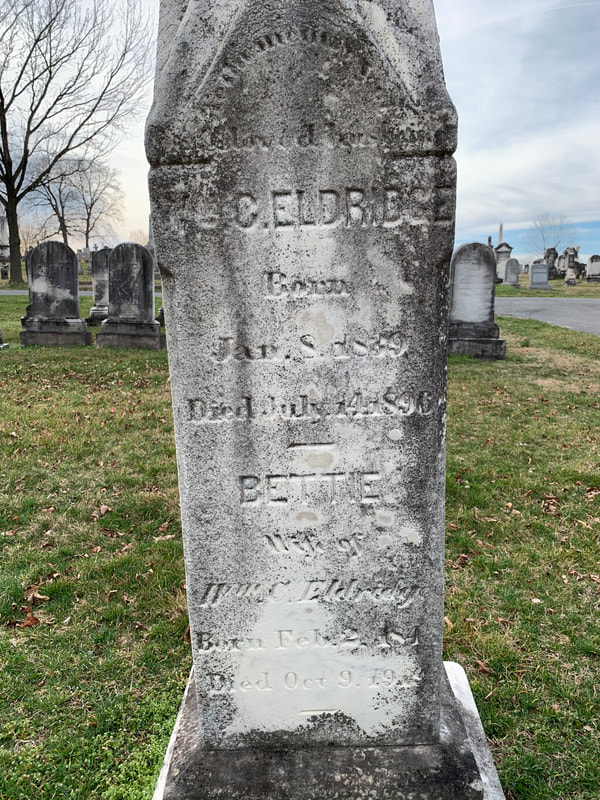

Since its Women’s History Month, I decided to seek out a leading businesswoman in Frederick’s distant past. There are plenty out there to choose from, but unfortunately most have not graced the pages of Frederick’s history annals. Information is scarce. One such that did, Mrs. Catharine Kimball (1745-1831), has held my interest for quite some time as a prominent tavern-keeper dating back to the Colonial era. Another woman (in the mid-late 19th century) seemed to jump off the pages of old newspapers at me with countless advertisements boasting her popular millinery business located in downtown Frederick. Her name was Elizabeth Jane Eldridge (1815-1895). Mrs. Kimball Frederick has been a popular hospitality center since its inception in 1745, welcoming travelers and visitors as an important crossroads town and commercial center. Few taverns have been praised more in the history books than that of Mrs. Catharine Kimball, who operated “the sign of the Golden Lamb.” Kimball served as her inn’s proprietor for over thirty years. Catharine Kimball was born Catharina Margaretha Grosh in Mainz, Germany on September 10th, 1745. She was the daughter of Johann Conrad Grosch and Maria Sophia Gutenberger. Interestingly, Kimball’s birthdate is the accepted birthdate for Frederick Town as well. The family, including Catharine’s brother and sister, arrived in America in 1748. It appears that she married William Kimball, a saddler by profession, in the early 1760s but this gentleman seems to vanish from the record by mid-decade. The couple had at least one child, Maria Barbara, born May, 1763. Three of Catharine’s brothers took part in the American Revolution. Her sister Mary (Grosch) Beatty would become the mother-in-law of Maj. Nathaniel Rochester (1752-1831), when the latter married Catharine’s niece Sophia Beatty. The namesake of Rochester, New York and his wife would give one of their daughters the moniker of Catharine Kimball Rochester (1799-1835). Mrs. Kimball’s father had started the location as a tavern and Catharine took charge at the time of his death in 1793. Here, many a famous guest, including Thomas Jefferson, had lodged. The hostelry also had a reputation for hosting many of the town’s important social events. According to Frederick legend, a young Barbara (Hauer) Fritchie is said to have served George Washington tea from a favorite, family china set. Catharine Kimball’s tavern would be sold in the late 1820s to Joseph Talbott who changed the name eventually to the City Hotel. Nearly a century later, in the early 20th century, the Francis Scott Key Hotel would sit on this site. Today, the former home of Mrs. Kimball’s fabled establishment boasts luxury apartments.  I wrongly assumed to find Mrs. Kimball here in Mount Olivet. I mistook her to be an Episcopalian, which she clearly was not. I soon recalled her maiden name and realized her father, Conrad Grosch, was one of the earliest, and most influential, settlers of town and served as a prime force in building a new home and place of Lutheran worship in the early 1760s. Catherine is buried behind Evangelical Lutheran Church on East Church Street. So, not a Mount Olivet “Story in Stone,” since she’s not here, but at least I gave her an important “shout-out” during this special month honoring women. Mrs. Eldridge Unlike Mrs. Kimball, I found Elizabeth Jane Eldridge in our cemetery’s Area C/Lot 91. However, I had a much easier time discovering info on Kimball’s early life and vital info compared to that of Mrs. Eldridge. Here was a lady whose advertisements filled local papers for nearly 40 years. It has frustrated the heck out of me as all I’ve only really been able to learn about her past from a few things gleaned from the 1850 census. This constitutes an “epic fail” as the kids say these days. Elizabeth Jane Eldridge was born in Virginia in 1815. I’m guessing she met her husband in Loudoun County, VA as he was employed on the Potomac River, but I really have no idea. I haven’t been able to narrow down her exact birthdate, birth location, maiden name or any family members on her respective familial side (parents, siblings). This info is not in our cemetery records, or any that I have searched through otherwise. Elizabeth likely met her husband, William “Clarke” Eldridge, in the nearby area/region because of a clue taken from that very same census of 1850. The Eldridges are found living in Medleys, Maryland, better known to us today as the vicinity of Poolesville in northwestern Montgomery County. Clarke Eldridge was born in Vermont in, or about, 1807. His profession is listed as that of “canaller.”  When I say canaller, I’m referring to the operator of a canal boat, one that would have traveled specifically on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal which stretched from Georgetown in the District of Columbia to Cumberland, Maryland—184.5 miles in length. The commerce marvel was begun in 1828 (at Georgetown) and reached Frederick in the early 1830s. Apparently, Mr. Eldridge would serve as a contractor for canal section 126 (between Edwards Ferry and Berlin (Brunswick)) in the summer of 1832. Clarke Eldridge would also serve as an assistant superintendent of this stretch as I found repair reports written in his hand in 1843. In the US census of 1840, Clarke is shown as a resident of Petersville District of Frederick County, living with what appears to be a young son and wife. This correlates well with another newspaper advertisement in the Baltimore Sun in 1843 in which Clarke is inquiring of the public about information about a missing horse that was stolen from his horse stable. From an advertisement, found in an 1845 newspaper from Alexandria (VA), it appears that two of Mr. Eldridge’s prime shipments were tobacco and livestock from northwestern Montgomery County at the location of the Monocacy Aqueduct’s eastern approach at mile marker 42.2. The aqueduct, itself, is the largest of 11 featured along the old transportation system and has been called an icon of American civil engineering. In my research, I was fortunate to have found another online source that chronicled deliveries on the canal in the waning years of the 1840s. Clarke Eldridge was transporting a wide variety of goods ranging from lumber, anthracite coal and plaster to groceries, corn, salt and dry goods such as boots and shoes. I stumbled upon a copy of Thomson’s Mercantile and Professional Directory of 1851 which listed our subject, Mrs. Eldridge, in the profession of a “milliner.” Sometime before 1856, the Eldridges moved to Frederick. Frederick diarist Catherine Susannah Thomas Markell penned a short passage in April of 1856 that she was attending Mrs. Eldridge’s store opening. The two women were neighbors and seem to have become good friends as well. In 1860, the Eldridges are found living in Frederick on West Patrick Street on the southside of the famed “bend” in the street. For long-time Fredericktonians, the house would have been located at the west end of the count courthouse and the former parking area of Delphey’s Sporting Goods, and the lane that went back to other commercial units and the McClellan Veterinary Clinic. Today, this area is best illustrated as the driveway between the courthouse and the West Patrick Street Parking Garage. In the 1860 census, Clarke Eldridge is listed as a merchant, and Elizabeth as a milliner. The previous two years (1859) featured newspaper advertisements for both of their respective businesses. Clarks was on the northwest corner of Bentz and West Patrick streets. Mrs Eldridge ran her business out of her home at No. 60 (today this would be No. 122), geographically situated at the bend in West Patrick. Clarke partnered with a gentleman named Jacob Henry Grove (1793-1878) and ran a grocery and hardware store. Elizabeth was a milliner, a term many are unfamiliar with in this day and age. It was a fancy term for a seller of stylish women’s hats. Of course, today, we seldom see women wearing headgear, and outside uniform accoutrements and baseball hats, men don’t don them like we use to. The Eldridges had two known children per the census: William Clark (b. 1840) and Emory Olin (b. 1852). The 1860 census also showed that other tenants living with the Eldridges included three young ladies employed as milliners, an random 11 year-old girl, and a 14 year-old black servant named Fannie Holland. I checked the background on the 11-year old and other milliners hoping that I may get a clue to Elizabeth’s background with one of these being kinfolk. I got absolutely nowhere after several hours of work. I did learn that Elizabeth was one of the Sunday school managers of the town’s Methodist Episcopal Church congregation.  Since info is so slim on Elizabeth, perhaps I should explain the origin of the word “milliner.” Here’s what I found on the internet (Wikipedia): A probable origin of millinery as an occupation is suggested by the etymology of the word "milliner." The Oxford English Dictionary states as the primary definition, "a native or inhabitant of Milan (Spain)." In reference to the occupation the second definition, denoted as obsolete, is "a vendor of ’fancy' wares and other articles of apparel, such as were originally of Milan manufacture, e.g. ’Milan bonnets,’ ribbons, gloves, cutlery." In A Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson derived "milliner" from "Milaner, an inhabitant of Milan," and defined the subject as "one who sells ribands and dresses for women." Thus, the products of Milan seem to have been related closely to the activities of early milliners. Purveyors of like products in England in the 1600s and 1700s became known by this name and it carried forward to those of the profession in the colonies. Competition It was interesting to learn that Mrs. Eldridge was not the only milliner in town. In fact she faced competition from a gentleman named Henry Goldenberg, and three other women: Miss Sarah J. Vermillion, Miss A. J. Stevens and Mrs. Catherine Elizabeth Tucker. I don’t really care about telling you about Mr. Goldenberg because its Women’s History Month and all, but I promise to tell you his interesting (and tragic) story another day. As for Miss Vermillion, she was born in 1812 and lived in the first block of East Church Street. She would pass in June, 1876 in Baltimore and is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area E/Lot 71 within a plot owned by the Keturah Hayes family with whom she lived while here in Frederick. Miss Anna Jane Stevens appears to have come to Frederick by way of Baltimore where her mother was a seamstress. Born around 1830, she may have wanted to test the waters out in Frederick and set up shop on North Market Street in the early 1860s. Perhaps it seemed a safer choice as her hometown of Baltimore was under martial law at the time with the guns of Federal Hill pointing down on the city. While here in Frederick, she met her future husband George W. Mark, who worked as a fireman for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Mr. Mark’s parents are buried here in Mount Olivet. It seems Miss Stevens abruptly left Frederick around 1868/69 and reemerged in early 1871. I found an announcement of her wedding in November, 1870 to Mr. Mark. However in the 1870 census, she is living with her mother in Baltimore, and Mr. Mark was a boarder in a hotel. Of great interest is the fact that living with George Mark is a one-year-old baby named Viola. The birth predates the wedding, so I’m curious if Miss Stevens ducked out of Frederick and took up residence because of the stigma attached at the time to having a child out of wedlock? Mrs. Stevens-Mark would eventually move with her new husband to West Virginia as he continued his work with the railroad. They would eventually take up residence in Philadelphia where her husband would die in 1908. Anna would live until 1923, however the census records don’t reveal whether she ever picked up professional millinery work again after she got married. She is buried in Philadelphia’s Mount Moriah Cemetery. Mrs. Catherine (Kephart) Tucker was born in Frederick around 1819. She married husband William J. Tucker in 1840. Mr. Tucker was a master carpenter and native of Frederick. Mrs Tucker was the mother of four children and is listed as a milliner in the 1860 census. She was aided in her business by sister Caroline Kephart. However, it seems that they were out of business by the middle of the decade. By 1870, it appears that Clarke Eldridge changed professions, albeit briefly. He is listed as a contractor for the railroad, the chief competitor against his old C&O Canal profession. I’ve struggled to find out more about this railroad venture, but this is certainly fitting since he had a like contracting job with the canal a few decades earlier. Two major events affected the Eldridge family and business. It likely had an impact on Mrs. Eldridge’s previously mentioned competitors as well. The first was the American Civil War. At war’s end, the family appear to have moved the business location out of their home and back up Patrick Street to No. 34 West Patrick which was a former building that stood on the southeast corner of the intersection of Brewers Alley (today’s South Court Street) and West Patrick. Today, you will find the Patrick Center, home to several financial-oriented firms, which overlooks the County Courthouse. Ironically, the Eldridge Store faced the City Hotel, former tavern of Mrs. Catharine Kimball. In February 1866, court records show that Elizabeth bought out the business venture of her son (William C.) and took over the entirety of the store including its contents. She seems to have enlarged her dry goods business with a focus on women’s clothing. Son William was working for her as a clerk. A second event of note came in late July 1868 as a terrible flood hit Frederick, doing its worst damage to the commercial entities and private homes between Brewers Alley and the iron bridge going over Carroll Creek. The famed Barbara Fritchie house was so damaged that it would be condemned and later demolished. The Eldridge home had to have taken in much damage. Diarist Jacob Engelbrecht says the family had lost a new wall constructed to the rear of their home and I am guessing this was perhaps for an addition being built as their back yard stretched all the way to Carroll Creek. Whatever the extent of the damage done by this flood, Mrs. Eldridge entered into a business partnership with a gentleman named John Marshall Landis (1837-1920) by century’s end. Landis was a retired grocer turned boot and shoe salesman. Advertisements now proclaimed the business as Eldridge & Landis. By 1870, Elizabeth was still operating her own business at this time. Her younger son, Emery O. Eldridge was attending Dickinson College in Carlisle, PA and then would head to New Jersey’s Drew Theological Seminary in 1872-73. Rev. E. O. Eldridge was ordained in 1875 as a Methodist Episcopal Church minister. He would preach throughout the country. In the early 1880s, he was in nearby Emmitsburg and would have stints in Winchester (VA), Baltimore and ended his career in churches located in Medford and Portland, Oregon. This same 1870 census shows two employees of the business living with the family in Elizabeth Sencil and Ella Stevens. Stevens may have had a connection to rival milliner Miss A. J. Stevens mentioned earlier. She would marry a gentleman named Isaac Shipley in 1871 and move to Baltimore. Miss Sencil would become the bride of William C. Eldridge. The 1880 census shows the Eldridge family still living on West Patrick, operating their business with Clarke back at the helm, at least on paper. Son William is living with them, along with his wife. Three other boarders are also shown here, all employees of the store as well. One such, Cecilia Peters, had been with the Eldridges working as a milliner for over twenty years. I again have an outside hunch she could have a familial connection, but have come up with nothing. Mourning Ware Clarke Eldridge died in August, 1887 after reported to have been in poor health for several years. It’s not known when he stepped away from the business, but an advertisement in Frederick newspapers of 1885 still attributes Mrs. E. J. Eldridge as the sole proprietor. Mr. Eldridge was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area C/Lot 91. The service was presided over by son Rev. Emory Olin Eldridge. The family plot had been purchased four years earlier for the burial of an infant grandson. Its easy to say that this site would see many a mourning bonnet over the next decade, most likely made by the talented hands of Mrs. Eldridge, herself. Mrs. Eldridge would operate her business until 1893, at which time she is found selling off dry goods and liquidating her personal assets. Son William C. Eldridge would run the dry goods/millinery business that his mother had faithfully established at a new location, No. 14 West Patrick. Today this is the site of the Verbena Salon & Spa. Elizabeth Jane Eldridge would live out her final days in Frederick, passing at the age of 80 on April 30th, 1895. Again, Rev. Eldridge would come back to town and help officiate the burial of a parent. The local newspaper took the opportunity to ask him his thoughts about Frederick while here. I’m sure the Eldridge plot held additional significance to the clergyman because it held the graves of his mother-in-law, Anna M. (Ireland) Yoe (1828-1906) who died at her residence in Washington, DC. Rev. Eldridge’s infant sons William Yoe Eldridge (d. 1883) and Robert Clark “Robbie” Eldridge (d. 1890) and an un-named baby (d. 1891) are also resting here. William Clark Eldridge died in 1896, and his widow Elizabeth Sencil Eldridge lived until 1919. Rev. Emery Olin Eldridge died the following year (1920) in Oregon and is buried there. One remaining individual here in the Mount Olivet plot is Ann Cecelia Peters, the longtime millinery assistant who lived with the family from 1850 until her death in 1892.

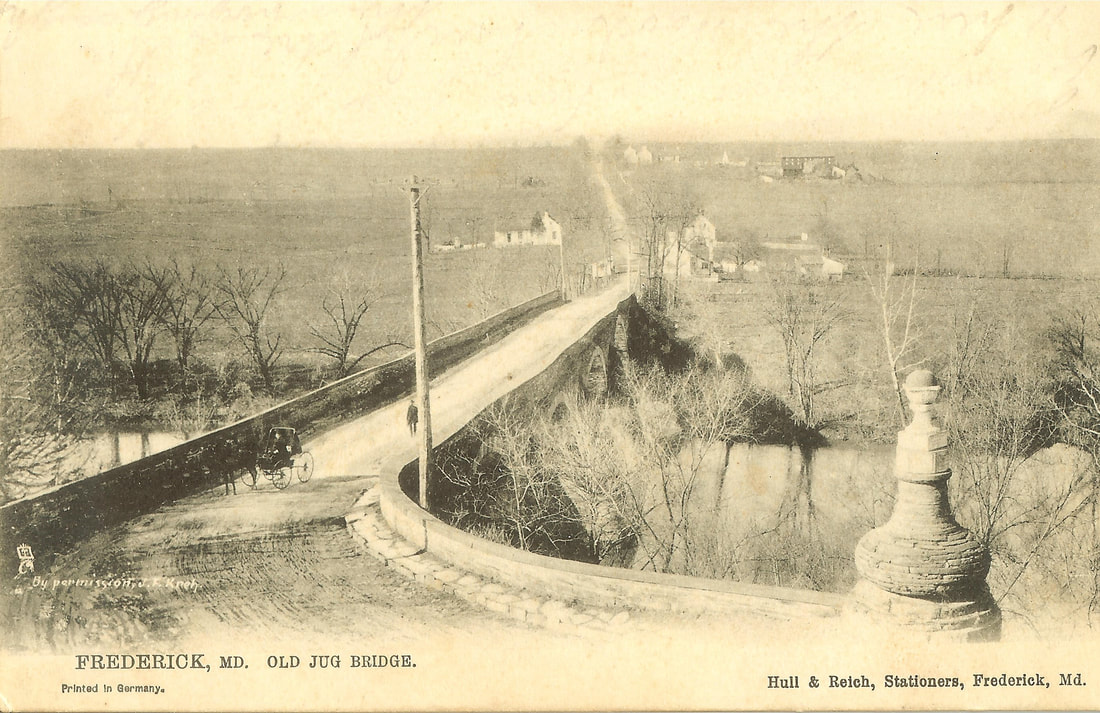

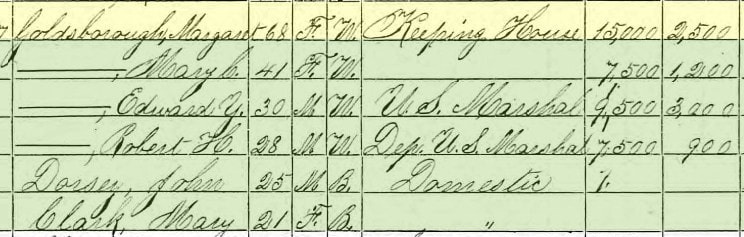

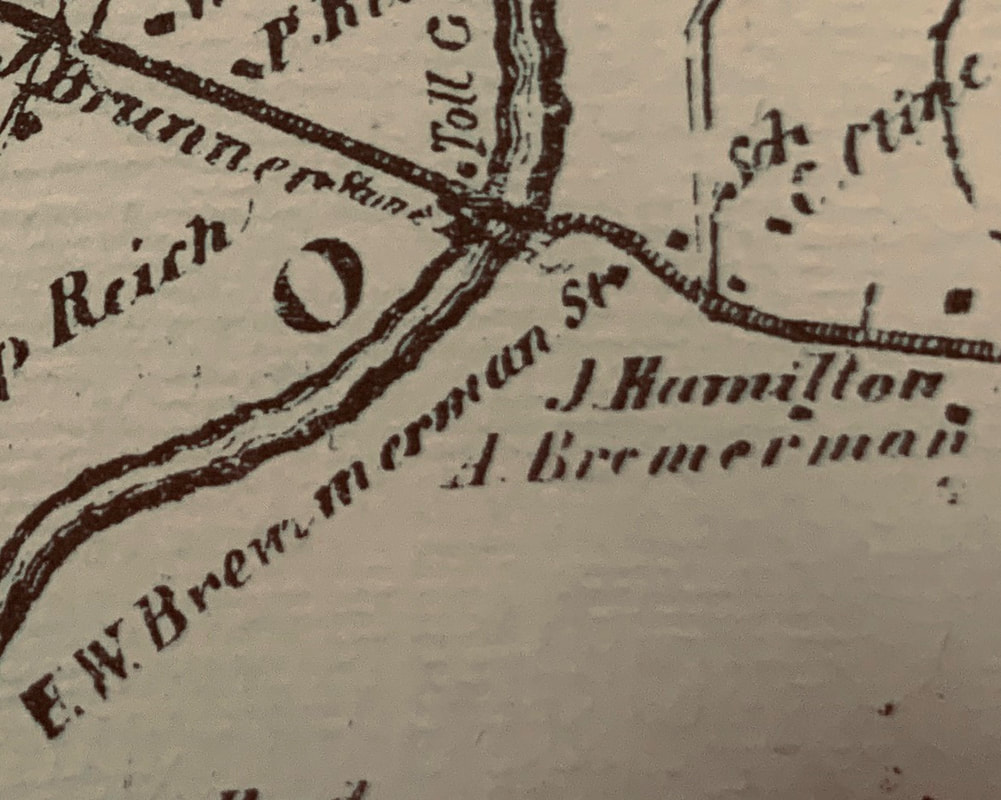

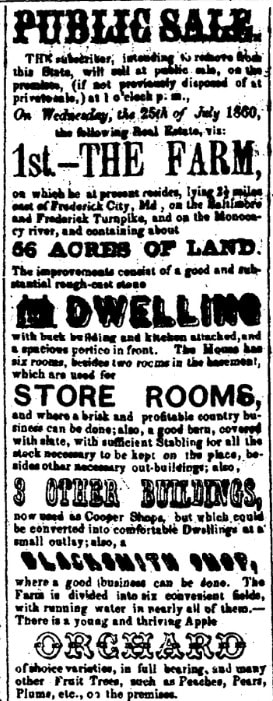

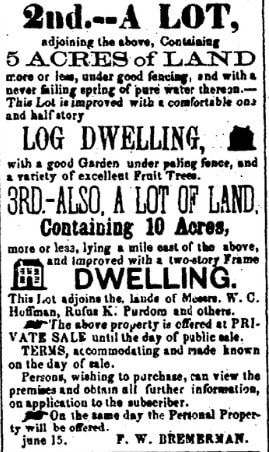

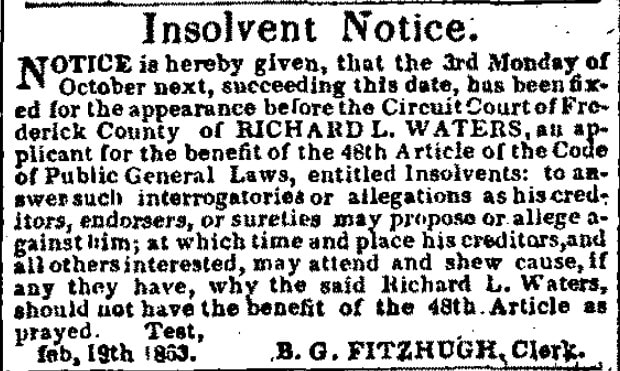

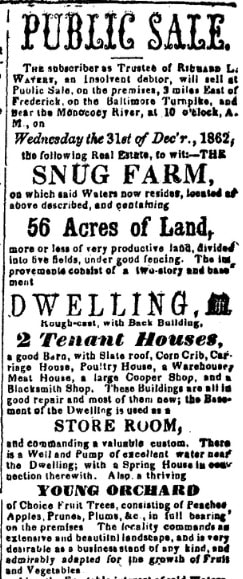

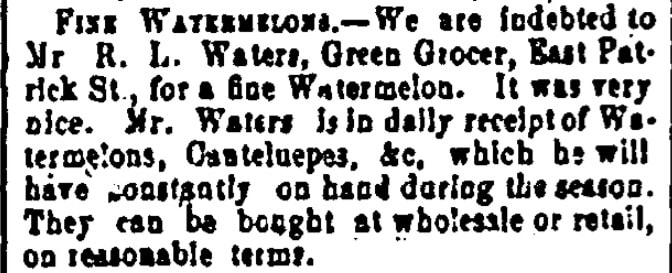

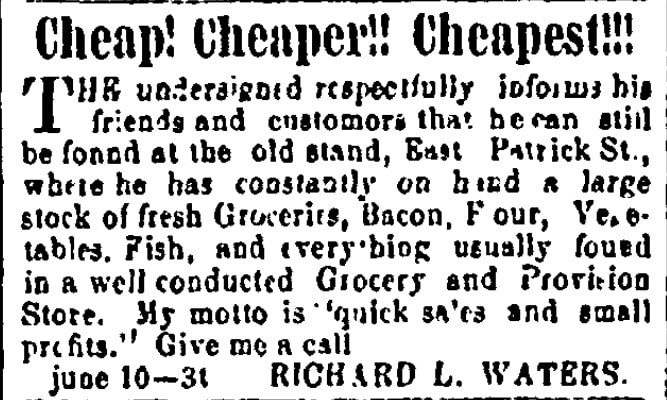

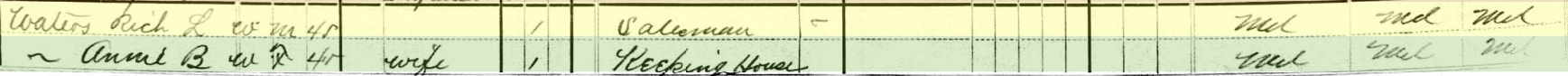

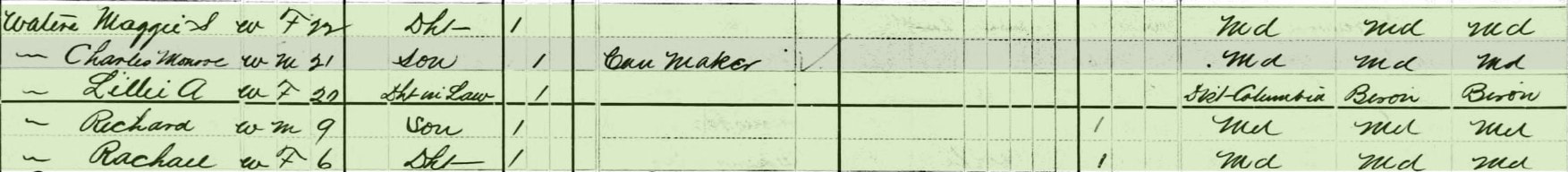

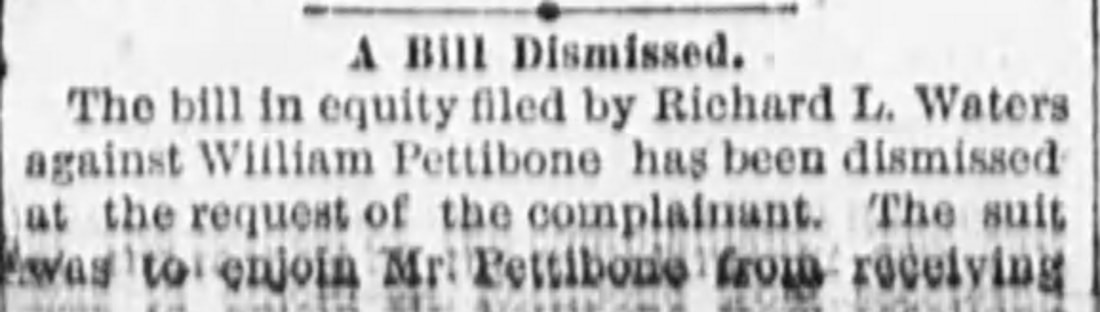

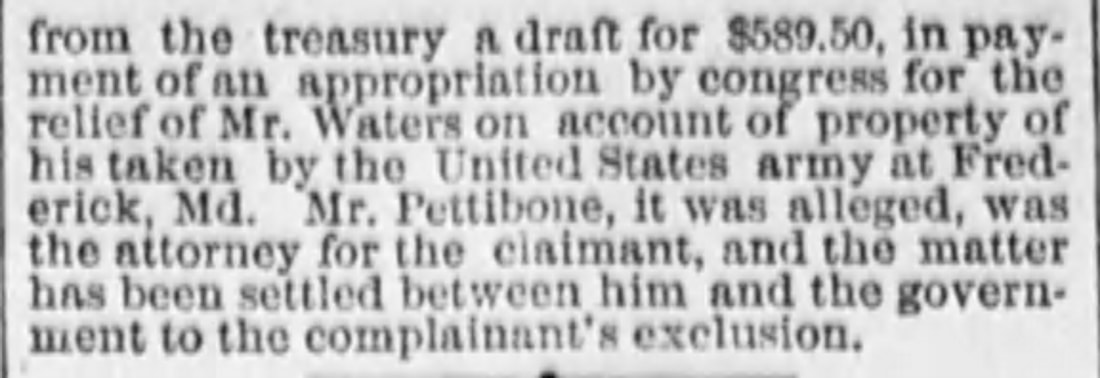

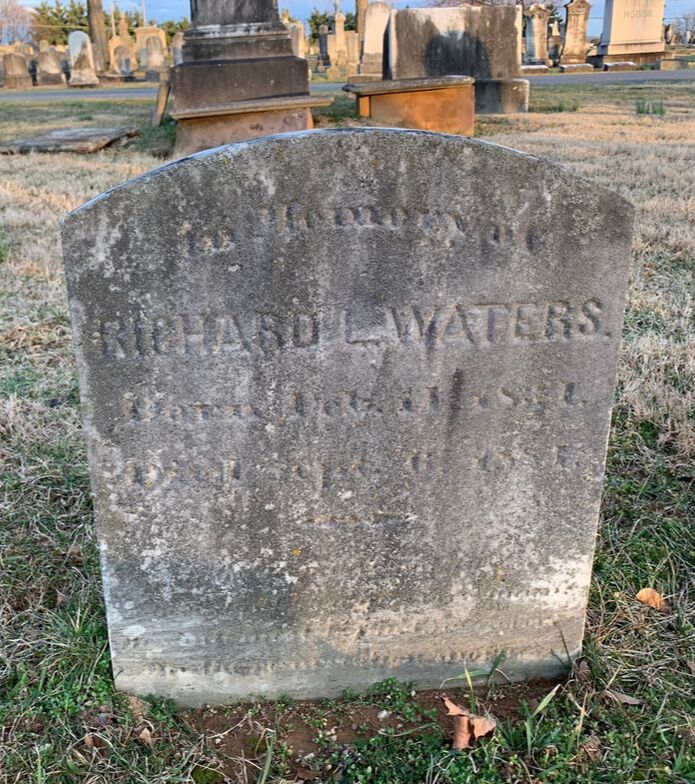

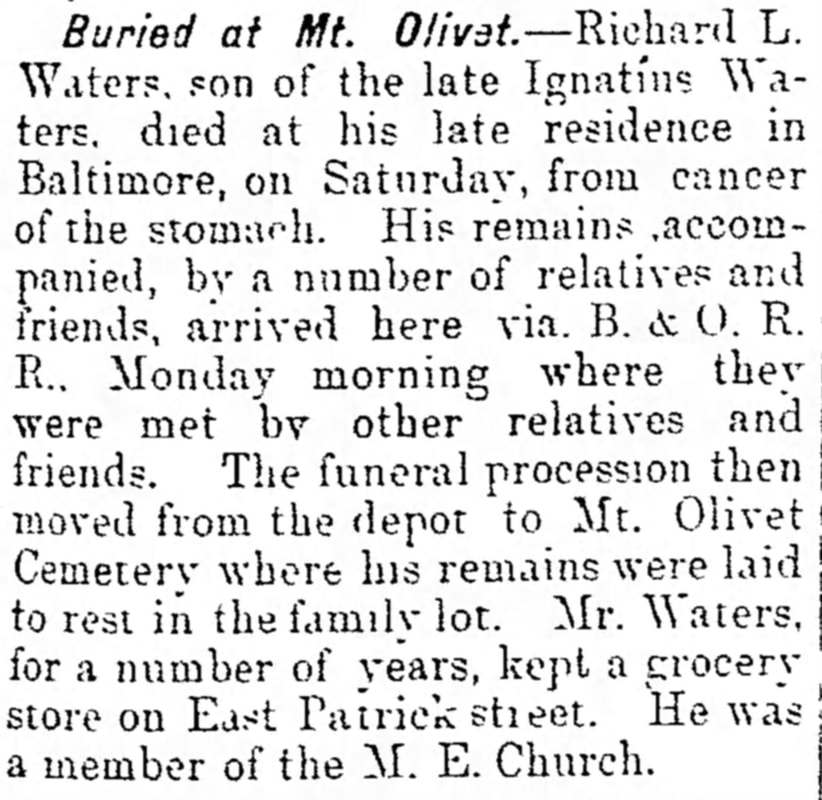

This is part-two of a story chronicling some of the local places frequented, and people met, by Col. Robert Gould Shaw of the American Civil War. If the name seems eerily familiar, you may recall being introduced to Shaw as the fearless leader of the 54th Infantry Regiment of Colored Troops who stormed Fort Wagner in the motion picture Glory. Shaw was formerly with the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment as a 2nd lieutenant, and spent the winter of 1861-1862 encamped just east of the Monocacy River and Frederick City at a place called Camp Hicks. In part 1, I shared a letter written home (by Shaw) to his sister, Effie, in which he talked warmly of spending a day with two of the daughters of Col. Edward Shriver, a lawyer, politician, officer and all-around, key Union man here in town. This correspondence was found in a work called Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. The work was edited by Russell Duncan and published Avon Books in 1992. My fascination, in respect to “Stories in Stone,” lies in the fact that the above-mentioned Col. Shriver and a daughter, Mary, are buried here in Mount Olivet. To think, each had a brush with greatness. I often have wondered how the colonel and his daughters reacted upon hearing news of Shaw’s untimely death on July 18th, 1863 in South Carolina while recalling their fond encounter(s) with the dashing young, soldier the previous year?  Camp Hicks Camp Hicks More Letters Home The next few correspondences written by Lt. Shaw were atypical of the time of year. It was December, and more importantly, Christmastime. In letters written on the 14th and 25th, Shaw laments the fact of being away from family and the pleasures of home during this special time of year. Apparently, we soon learn that Shaw had received a special gift from his sister mid-month—42 pairs of mittens. With the holidays behind him, Shaw in his first letter of the new year recounts some of the non-glamorous experiences of his military duty. Cantonment Hicks Jany 15 1862 My dear Effie, I have, I believe three letters from you unanswered, the last received day before yesterday in which you relate your encounter with, and defeat by the invidious fog. I hope he relented at last and that you have got away. I proceeded immediately after receipt of yours to inspect my checks and I don’t think you w’d find them much less flabby than formerly. Indeed, Mother’s account of my corpulency must have been a little exaggerated for I don’t perceive much increase my-self. I returned yesterday noon from the Monocacy bridge, between here and Frederick where I was on guard for 24 hours, and where I should have had a very pleasant time if it hadn’t been for three brats who tormented me. I stayed in a house near the bridge, and thought at first that the landlady was a very pretty & pleasant woman, but the bad behavior of the above-mentioned children soon brought out some little characteristics which were, to say the least, not ladylike. She got very much enraged and said to the nurse: “Hang you, you black imp, I’ll knock your black head off”—and to the children “Get out of this or “I’ll smack your jaws!” and made use of many other expressions. At night instead of putting the children to bed, the plan was, to get them asleep downstairs & then carry them up. Of course, this was a tedious process & involved much screaming, swearing, bawling & blubbering. Three times it was tried & three times they waked up on the way upstairs. After the third failure the noise was something terrible—all the three children screamed at the top of their lungs. Mrs. waters cussed & swore at the black girl. The black girl cried and actually said it wasn’t her fault. Mr. Waters consoled himself & vainly tried to amuse the 2 children by vigorously playing upon the most infernal old fiddle that ever was manufactured and beating time very hard with his cowhide boots. I sat with a smile on my face, but despair in my heart trying to concentrate my ideas sufficiently to understand "Halleck’s Elements of Military Art & Science.” May I be preserved in the future from such scenes at these! I didn’t bargain for anything of the kind when I joined the regiment. I originally read this particular letter for the first time about 15 years ago and pondered the location of this residence of the Waters family. I knew it was in the vicinity of the old Jug Bridge’s eastern approach, today’s MD144 over near Bartonsville and Spring Ridge, and not far from the site of Camp Hicks off of Linganore Road. Jug Bridge itself was a marvel in engineering for its time, having been built in 1808-1809 as part of the Baltimore-Frederick Turnpike. It was a true asset in the transport of travelers, pioneers, and natural resources and farm products from western Maryland to eastern manufactories and the port of Baltimore. It was equally important in the American Civil War for moving troops. It behooved the Union Army to protect this important gateway from being sabotaged by the Confederates--hence Shaw’s guard duty assignment. So the next question is this: "Who was this family whose house Shaw and other soldiers took refuge in during the war?" I looked at two old Frederick maps: the Isaac Bond Map of Frederick County (1858) and the Titus Atlas Map of 1873. I could not find a Waters family name associated with any houses in the immediate area on either map. The US census records of 1860 and 1870 were of no help as well because I didn't find any Waters in this specific location. I started to deduce “Waters” families by looking at those buried here in Mount Olivet, because otherwise they wouldn’t be relevant to me for my story’s sake (as this is a blog about folks buried in Mount Olivet.) The exercise limited me down to three gentlemen who seemed to match up age-wise to being of “young father age” in the year 1862. Two, of the three men, had little kids in 1862, and only one had three at this time. This latter suspect perfectly fit the bill of siring the “brats” that tormented the man who would lead the legendary “54th Mass” later this same year. My person of interest was Richard Linthicum Waters. I would soon find that his wife, Ann Virginia (Hobbs) Waters, had family in the immediate area—father Rezin Hobbs (1810-1891) and wife Margaret Galezio (1810-1881). The neighborhood was known more commonly by the name of Pearl, nearly a century-and-a-half before the name Spring Ridge would come around. I still didn’t know where this house was, but asked my research assistant, Marilyn Veek, to search real estate records for a clue. I shared with her my “non-findings” on the maps earlier mentioned, not to mention census records. I had found Richard L. Waters living in Carroll County in 1860 within the Freedom District at the hamlet of Freedom. This is the approximate location of Centennial High School today, just northwest of Eldersburg in southern Carroll County. He was listed as a farmer, and I found other supposed relatives of his father-in-law (Rezin Hobbs) in the area. In 1870, the Waters family was living in Frederick City and Richard was listed as a green-grocer and living on East Patrick Street. Richard Linthicum Waters was born February 11th, 1834, the son of Ignatius and Susan R. (Linthicum) Waters. In 1850, the Waters lived in the Howard District of Anne Arundel County, and Ignatius was listed as a Methodist minister. This area would become Howard County in 1851. Family history pointed towards the family being slaveholders. Richard married wife Anna Virginia Hobbs on October 7th, 1856. As far as I could ascertain, the Waters had the following children: Sarah Margaret “Maggie” Waters (1857-1887) Charles Monroe Waters (1859-1909) Amelia Waters (1860-1863) Minnie Waters (1862-1865) Ida Kate Waters (1866-1869) So this proved my postulate of Richard and Ann Waters having three children with the potentyial for extreme "brattiness" in January, 1862 at which time Lt. Shaw would have stayed in their home in between guard duty shifts atop the old Jug Bridge. However, where was the Waters’ home in 1862, as I could not prove that the family was living here in the Bartonsville/Pearl area on the east side of the Monocacy River, and along the National Pike? That’s when the “smoking gun” was discovered by my trusted assistant. In August 1860, Richard L. Waters obtained the property named “Snug Farm” from Frederick W. and Malinda Bremerman. Ann Waters father (Rezin) and husband (Richard) would enter into an agreement to mortgage the parcel for $4,500. It can be found on the 1858 Isaac Bond map and labeled under the name of F. W. Bremerman. The property is the first dwelling found on the east side of the Monocacy along the Frederick-Baltimore turnpike, on the southside of the road.

While the Bremermans were losing children in the late 1850s, the Waters were gaining them. Perhaps, family help was needed from Ann Waters’ family ( the Hobbs) who lived here in this vicinity. This would have been a comfort for the young mother in childbirth, along with relatives to look after her other small children. Besides, if we can trust Lt. Shaw’s judgment, those Waters' kids were a handful to say the least! The Waters owned slaves in the 1860 census and possessed a domestic servant in 1870. So it is not far- fetched that the family had at least one slave in January, 1862, whom Mrs. Waters verbally attacked in front of Robert Gould Shaw. Interestingly, this would be one of the first images of slavery and oppression witnessed by the wealthy New Englander who would help mold the most famous Black fighting regiment in US history (the 54th). An interesting paradox, found all to often in Frederick’s history as “a border county within a border state,” is that Mr. Waters was a die-hard Union Man. He even hosted a Union rally on his property back in the summer of 1861. One of the speakers at this event was Col. Edward Shriver. The Shriver family, one of the town’s most loyal and patriotic, (of whom I mentioned in part I of this article) also owned slaves, as did Frederick’s greatest Union supporter of all-time—Barbara Fritchie. So don’t let anybody tell you that the American Civil War was solely an act to end slavery as there were many factors at play, and motivations for men to fight on both sides (states rights, nationalism, patriotism, economics and capitalism, abolition of slavery, humeris, etc). Now back to the family of Richard L. Waters, host to Robert Gould Shaw in December, 1861. The couple would have other children born later in the decade so I’m sure the sleepless nights didn’t end for several years to come. As much as I feel sorry for Mr. and Mrs Waters, I, of course, feel more sorry for the slaves and servants that had to dote on the brats with little say in matter. So what happened to the Waters family? Well, it appears Richard declared bankruptcy in spring of 1868. This led to the Waters family losing the fore-mentioned property and likely precipitated the move into Frederick. I found a few ads beginning in 1866 where Richard is advertising his business wares as a green grocer. By 1880, the Waters had moved again—this time to Baltimore. In the 1880 census, Richard is listed as a salesman, and the family was living on Lombard Street. Two more children blessed the family in the forms of Richard Vincent Waters (1870-1926) and Rachel N. Waters (German) (1873-1947). Sadly, the Waters had endured the deaths of three children in the 1860s, perhaps leading to financial woes and the original move from “Snug Farm” to Frederick. Daughter Amelia, the youngest of the “three brats,” died in February, 1863. Two other daughters, Minnie and Ida Kate would die in 1865 and 1869 respectively.

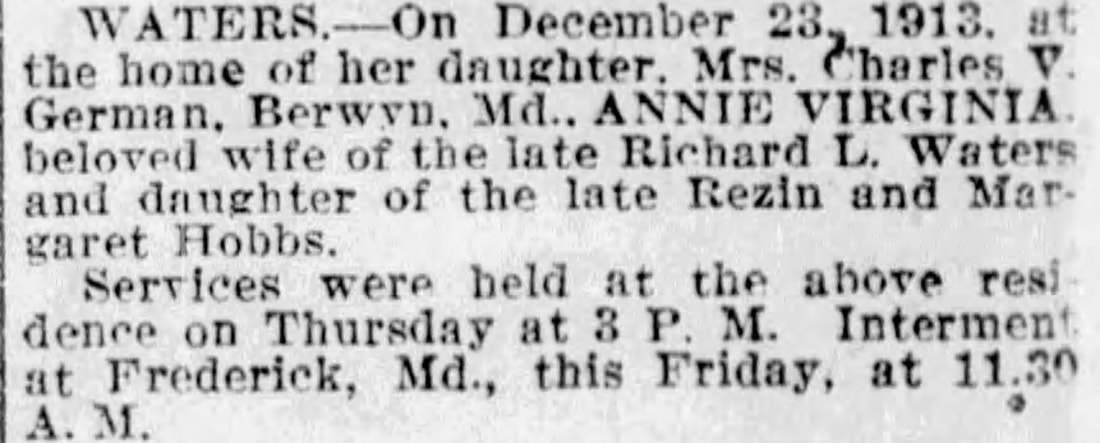

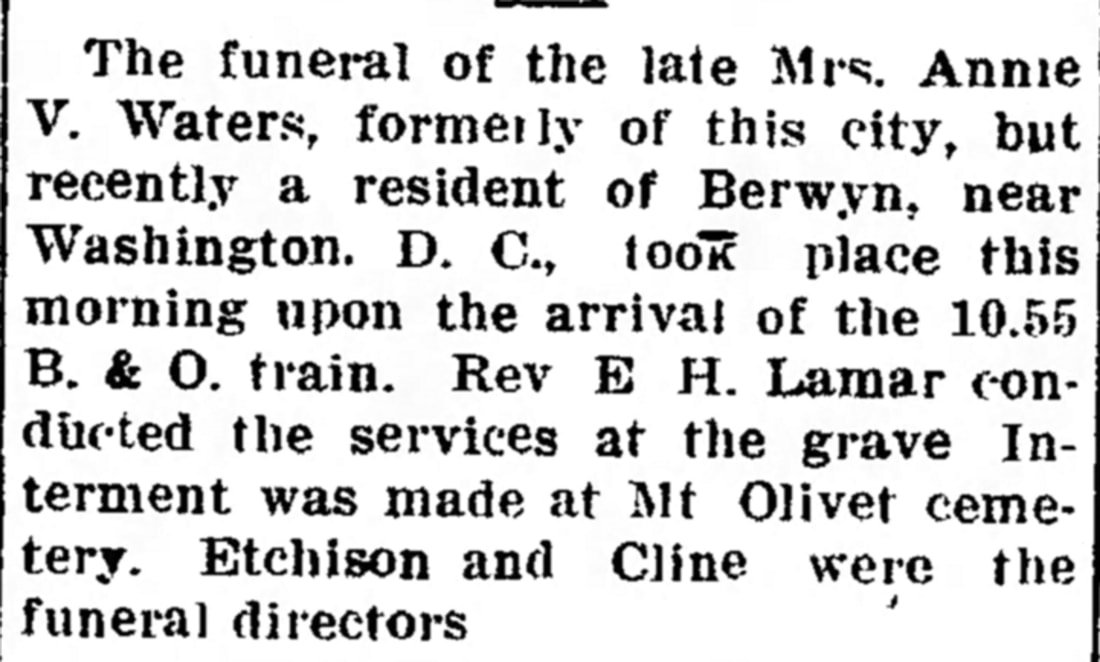

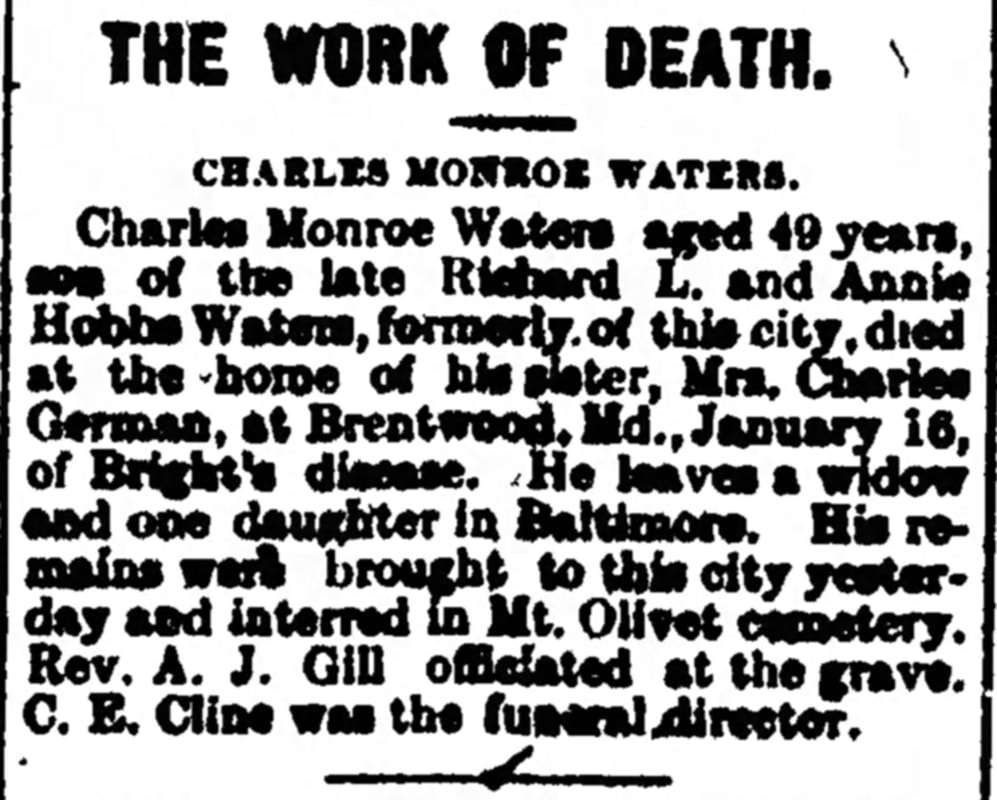

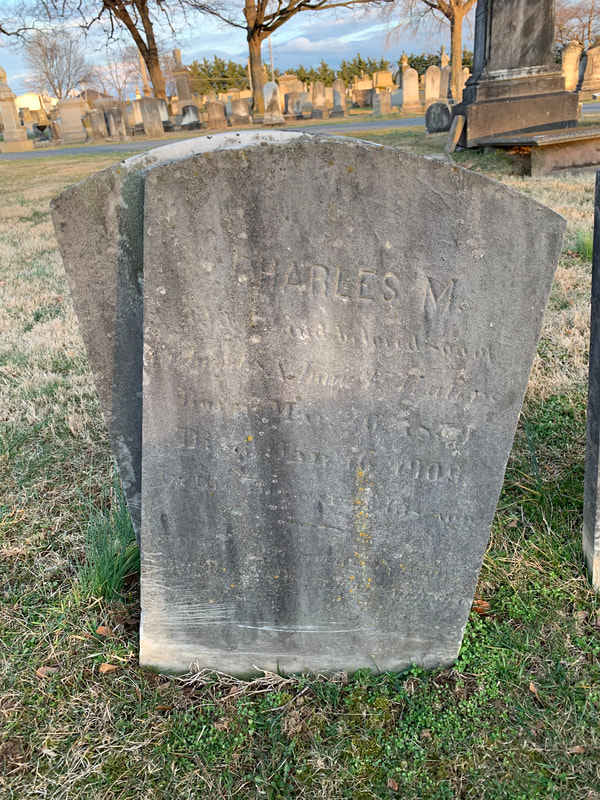

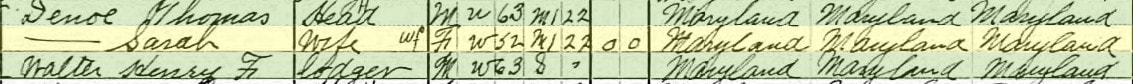

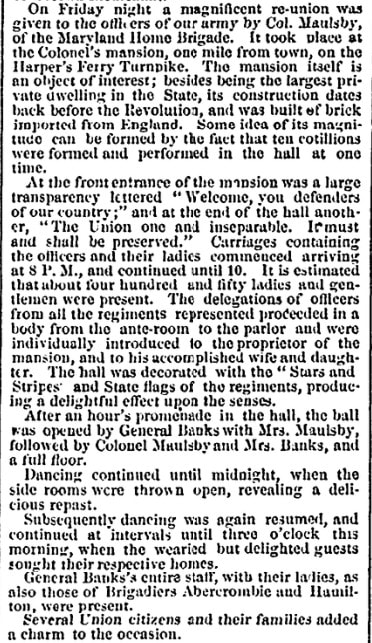

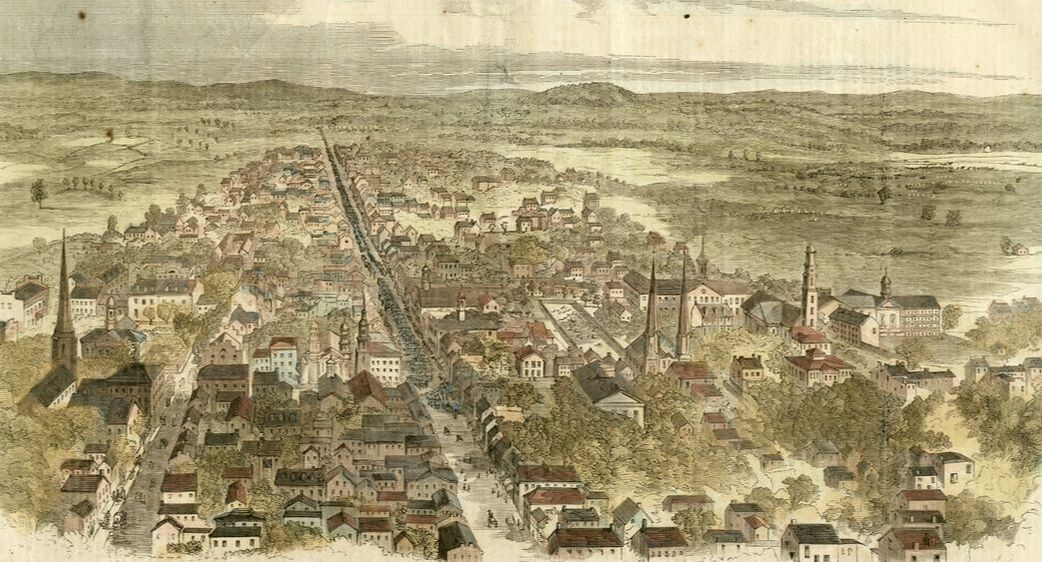

Richard L. Waters was duly buried in the Hobbs family plot in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 139, alongside his three previously deceased daughters. The “sharp-tongued” Ann Waters would live until 1913, dying in Berwyn, MD. Brat number two, Charles Monroe Waters, grew up and eventually worked as a foreman for the American Can company in Baltimore. In 1880, he married an Irish immigrant named Catherine and had two daughters and two sons. When Charles died in January of 1909, he was living in Brentwood, MD in Prince Georges County. His body was brought to Frederick to be buried beside his father and sisters. Sarah Margaret Waters, “Maggie,” married Thomas Edward Denoe in 1887. Interestingly, Mr. Denoe was a grocer in Baltimore and had a successful career, primarily running his store on West Baltimore Street. The couple never had any children. Maggie died in 1923 and is buried in historic Loudoun Park Cemetery in west Baltimore. Unfortunately, I could not come across a visual of the old Waters house that Lt. Shaw visited. The former house no longer exists as it was torn down long ago to make way for the new alignment of the National Pike/MD144. As many know, the original Jug Bridge collapsed on March 4th, 1942, when heavy rains and high winds caused a 65-foot span of the bridge to collapse. A few years later the stone arch bridge was demolished and little remains of it. The replacement bridge was in operation for decades until a new crossing over the river was built to the immediate south of the old bridge.  From this aerial shot of MD144 on the eastern approach to Jug Bridge over the Monocacy, the Waters homestead was located at the site of the blue swimming pool pictured above (very fitting-Waters). Below features a view from the intersection of Linganore Road and MD144 looking southwest toward the former location of the R. L. Waters residence. "Prospecting" in Frederick In early December, 1861, Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht estimated more than 16,000 Union soldiers had recently come to town and were encamped around it. They were under the command of Gen. Nathanial Prentiss Banks who set up his headquarters at the southeast corner of N. Court and W. Second streets, a few doors north of Col. Edward Shriver’s home and courthouse square. Regiments, here at that time, were not just from Massachusetts, but hailed from New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Indiana. The streets were packed with “boys in blue” as Frederick had never been so populated ever before. Unfortunately, liquor and libations got the best of many of these soldiers, far from home with time to kill. In one of his letters, Robert Gould Shaw talks about a “sobering” experience while attending a great party here in town in early January, held at a landmark structure that still stands today.

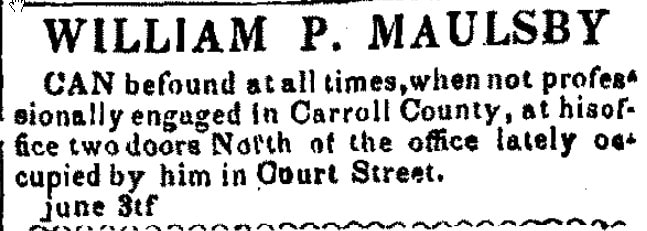

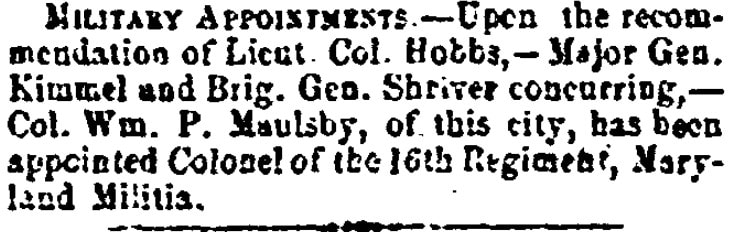

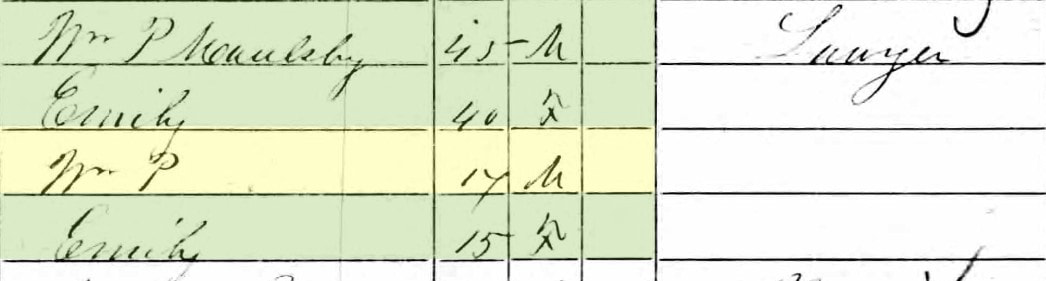

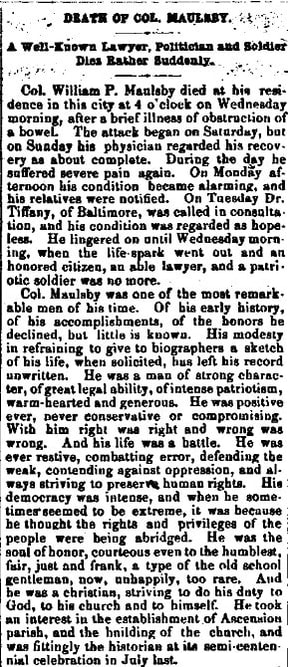

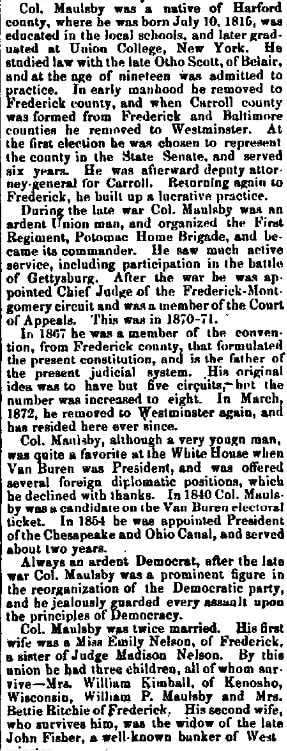

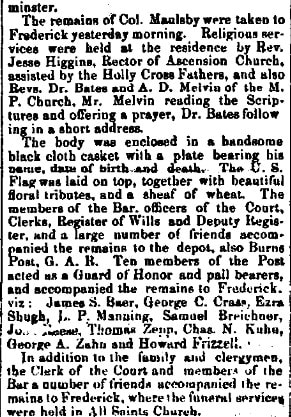

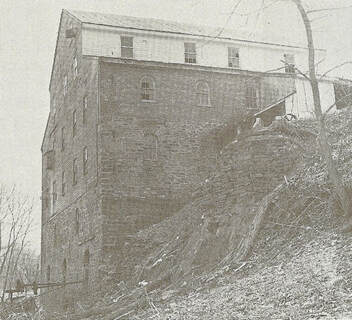

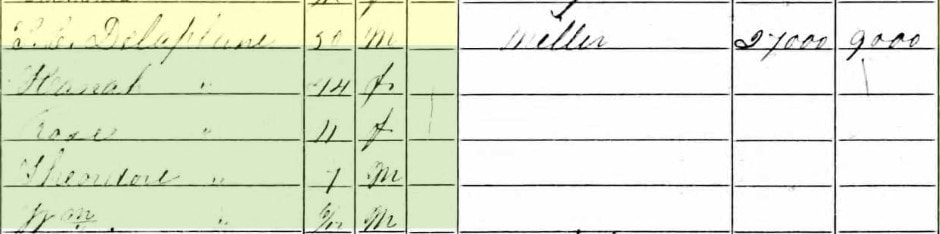

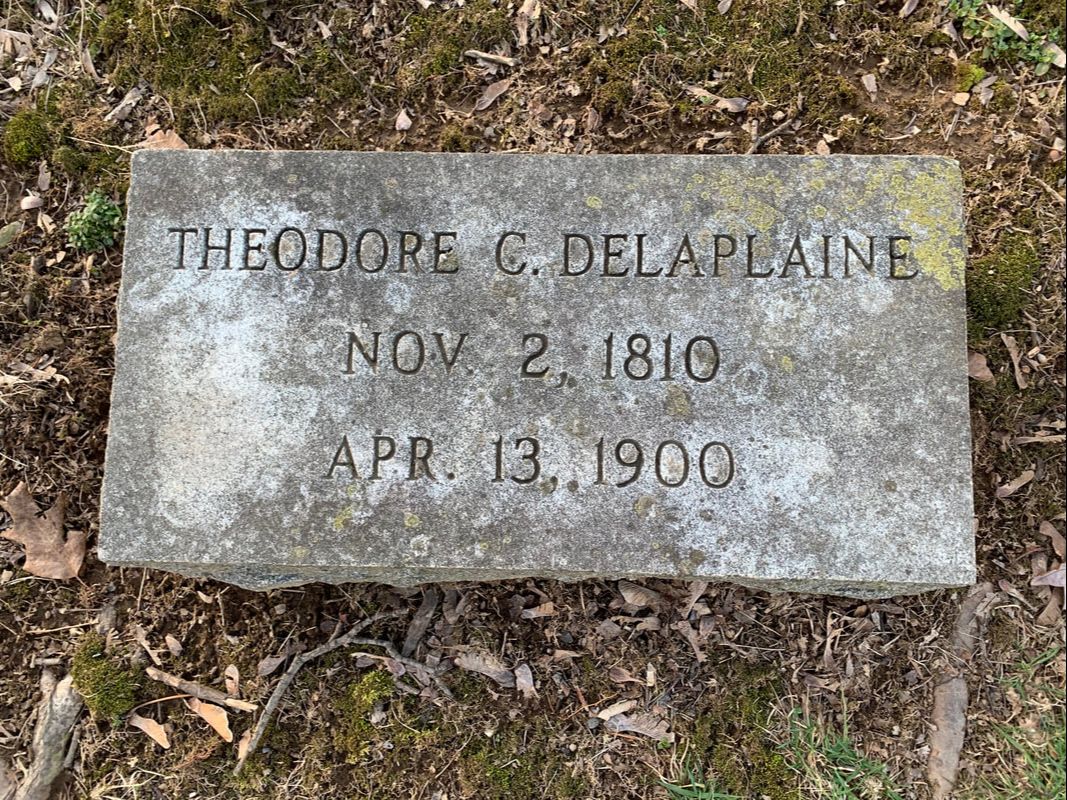

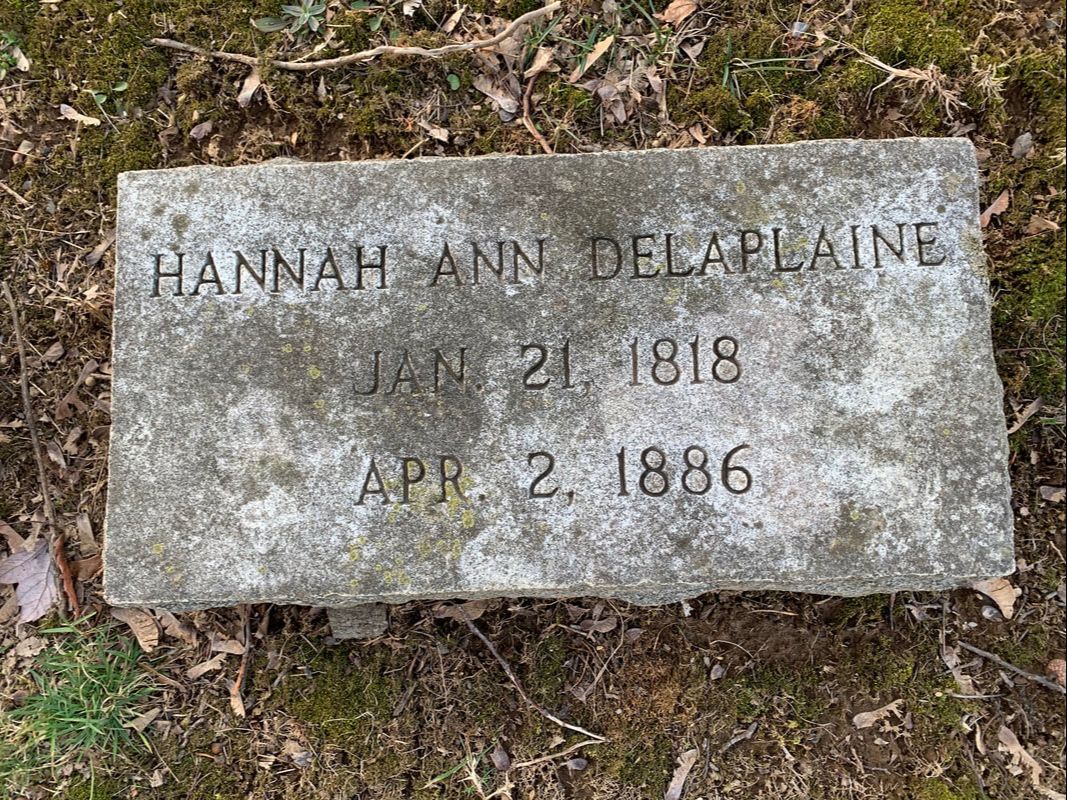

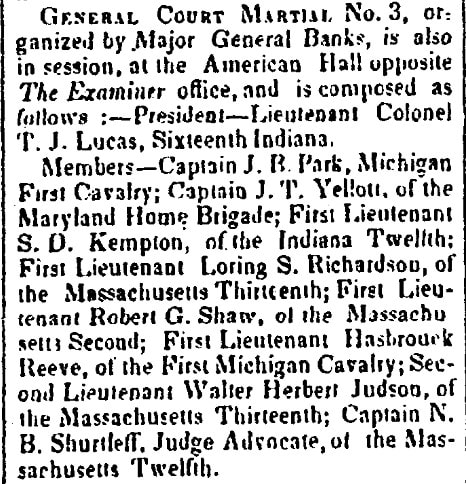

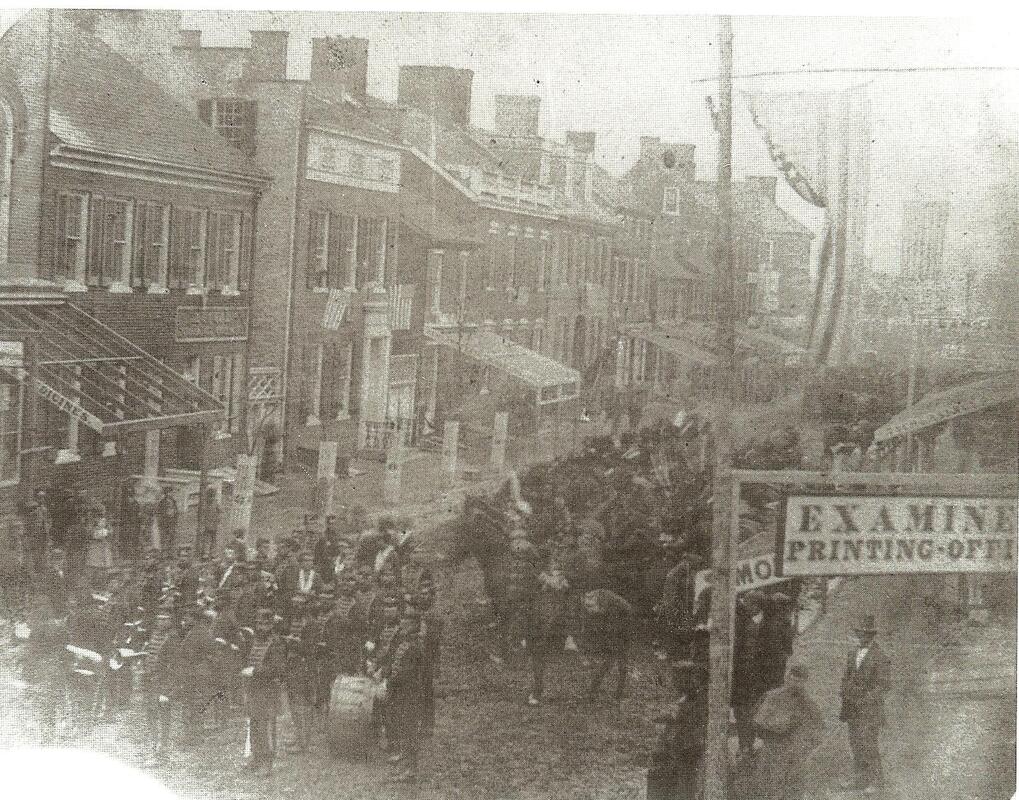

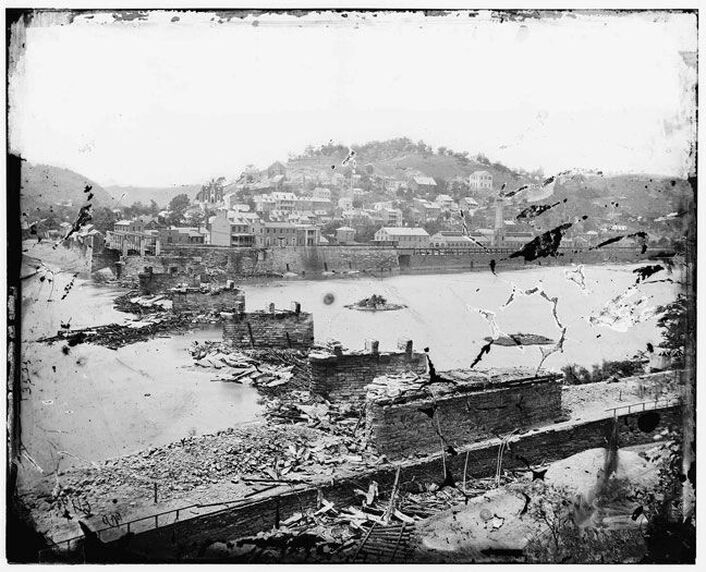

The party in question was held on Friday, January 10th (1862) at Prospect Hall, former site of St. Johns Literary Institution later known as St. John's Catholic Prep (College Preparatory School). The owner in 1862 was local lawyer William Pinkney Maulsby, Sr., born July 15th, 1815 near Bel Air in Harford County. Maulsby had been commissioned a colonel during the war and was the first commander of the 1st Potomac Home Brigade, organized at Frederick, Maryland, beginning August of 1861. It was mustered into the Union Army under Gen. Banks on December 13th, 1861. As a young man, Maulsby studied law in Baltimore under the tutelage of John Nelson (who would later go on to serve as the US Attorney General). In 1835, William married John Nelson’s daughter, Emily, and embarked on a legal and political career. You may recall a story I published a few years back about William and Emily Maulsby’s daughter Betty Harrison Maulsby (Ritchie) who was was the driving force in organizing Frederick’s first DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) chapter in 1892. Betty’s daughter, Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean would serve as President General of the national organization from 1905-1909.  Prospect Hall Prospect Hall Upon the creation of Carroll County in 1837, Col. Maulsby represented the county first as a state senator, then as a state’s attorney. By 1850, he had moved his family to Baltimore before again moving to Frederick for business and political reasons. In 1856, Maulsby purchased “Prospect Hall,” a large Greek Revival style mansion just south of the city. Prospect Hall would serve home to the Maulsby family from 1856-1864 and the location did more than host the future hero of Glory, as this would be the site where Gen. George Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac in late June, 1863. Col. Maulsby headed his regiment (Potomac Home Brigade) for three years, leading his men at Harper’s Ferry, Gettysburg, Monocacy, and countless smaller skirmishes. After leaving the US Army, he sold Prospect Hall and moved to downtown Frederick and a home on East Second Street. Despite his service to the Union, William P. Maulsby earned the wrath of many Republicans in the post-war years due to his affiliation with the Democratic party and his leniency towards the defeated secessionists. In 1866, he ran an unsuccessful bid for congress. Maulsby continued his career as a judge and eventually moved to Westminster where he died October 3rd, 1894. He is buried under a large cross monument in Mount Olivet’s Area G/Lot191. A Very Queer Old Party Lt. Shaw talked of a “party” of another kind in a letter sent to sister Effie in February, 1862. His hosts were prominent mill-owners in Buckeystown who had a son whose later printed creation would “shower good news” down on Frederick County for well-over a century. I also owe this same man homage as his direct descendants gave me my first real job, and the opportunity to work professionally in public history. Frederick Md. February 9,1862 My dear Effie, I have received two letters from you since I last wrote and I admire your constancy in writing so regularly. Susie is in Washington & I have just telegraphed to Cousin John to know if he can’t go home this way and make us a short visit. I can’t possibly go away, so if they don’t come to Frederick I shan’t see Susie at all. That would be too bad when we are so near together. Today, for the first time, I think, for five weeks the weather is fine—but it looks as if it were going to cloud over again in a little while. I have very pleasant lodgings here in a family consisting of a very queer old party, named Delaplane, and his wife. The latter has a most wonderful appetite and an extraordinary love of good dinners, the result of which is, that we live remarkably well. Capt Savage & Dr. Stone of the 2 Mass. Live here too, but will soon be going back to the regt. I am afraid I shall be rather lonely then. We have two rooms adjoining each other, one of which has a large open fire-place, which is very comfortable & cozy. I go round to the Court-Martial around 10 o’cl. A. M. and we usually get through at 2 P. M. so that I have a good deal of time to myself. I find though, that camp is the best place for me. I am always in good spirits out there—probably because it is such a wholesome life. As soon as I get a horse, I shall have a much pleasanter time here, for I have much difficulty in getting about now—especially out to camp where I want to go quite often. Robert Gould Shaw was living with Theodore Crist Delaplaine and wife Hannah (Wilcoxen) Delaplaine, proprietors of the Monocacy Flour Mill located southeast of Buckeystown along the Monocacy River. This property still exists today off of Michaels Mill Road. Mr. Delaplaine was born in Georgetown on November 2nd, 1810. Two weeks after his birth, his mother died. At this point he was taken to Frederick to live. In T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County (published 1910), shares the following anecdote about young Theodore: “On the way from Georgetown to Frederick the stage coach broke down but the little fellow was passed through a window, and was quite unharmed.” I don't know whether that means if he was thrown out of the vehicle, or simply handed out, but it piques curiousity. Young Theodore's childhood was spent on a farm near Ladiesburg and he was educated in the country schools. He got his first job at Greenfield Mills in southern Frederick County and then added to his “milling” experience and education by working at like operations in Halltown (WV), Bladensburg (MD), Georgetown (DC), Alexandria (VA), Highland and Germantown (OH), and Missouri. Delaplaine returned to Maryland and owned/operated various mills in Frederick County along with getting further instruction as an employee of the famed Ellicott Mills in Ellicott City (Howard County). In 1851, Theodore Delaplaine acquired the Monocacy Mills outside Buckeystown which he would operate successfully for the next 24 years. Williams’ History goes on to say: “During the Civil War his output reached one hundred barrels a day. The quality of his flour was excellent and much of it was sold wholesale to South America." In 1862, General Lee’s Confederate troops made a raid on Delaplaine’s mill and took seven hundred barrels of flour. The general is said to have offered to pay in Confederate money as far as he was able but, knowing that it was practically useless, Mr. Delaplaine refused the money. This story illustrates the importance of Union protection for the mill, not unlike the old Jug Bridge, as it was a prime target of the Rebels. It's no wonder the Delaplaines were so willing to provide soldiers accommodations in their humble abode.  Wm T Delaplaine Wm T Delaplaine Theodore Crist Delaplaine was married in 1848 to widow Hannah A. Wilcoxen (b. April 21st, 1818), daughter of Capt. Eden Edmonston and Lucretia Waters. And yes, Mrs. Delaplaine, through her mother's family, was a distant cousin of the fore-mentioned Richard Waters. The couple had three children: Rosanna Delaplaine (Dutrow) (1849-1883), Theodosia Waters Delaplaine (1854-1944), and William Theodore Delaplaine (1860-1895). From all accounts, these children seemed a little better behaved than those of Richard L. and Annie Waters mentioned earlier. To some of you, the Delaplaine’s youngest child’s name may seem familiar because William T. Delaplaine started the Frederick News in 1883. He would die young of pneumonia at the age of 35, leaving his four young sons to carry on the family business which was handed off to future generations. I had the great pleasure of working for, and under the tutelage of, Theodore Crist Delaplaine’s great-grandson, George B. Delaplaine, Jr. and great-granddaughter, Frances Delaplaine Randall while at Frederick Cablevision and GS Communications for 12+ years. If it wasn't for them, I likely wouldn't be writing this article for you today. Hannah Delaplaine died on April 2nd, 1885 and was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 257. The old miller, Theodore, would join his wife here five years later, dying on April 13th, 1900 at the age of 90. Theodosia is buried in this plot with her parents, and William T. in an adjoining lot. Sister Fannie (Delaplaine) Dutrow is buried in Urbana’s Zion Cemetery. Parting Words A final letter was written from Frederick by Robert Gould Shaw to his mother on February 16th, 1862. In this, he talks of calling on the prettiest girl on town, but her name is omitted in the publication. Unfortunate, as I bet she’s here in Mount Olivet, whoever she was. Shaw also speaks of attending a church service at All Saints Episcopal Church on West Church Street (Frederick) and finding himself, along with the church sexton, the only men in the building full of ladies. Sadly, Shaw ends the letter on a sour note in respect to Frederick, but one that would likely to have subconsciously fed his drive for the job ahead that he was destined for: “How do you feel about the good news from the South and West? All I want or wish for this week is to hear that Fort Donelson and Savannah are taken. Next week I should like to have Burnside take Norfolk. I am very much afraid, though, that we shan’t have such a run of luck as that. Some of the Secession people here were enraged at the news. I heard one girl say to another, when I was standing near them in the street, 'I like a nigger better than a Massachusetts soldier!' This same young person turns up her nose, and makes faces, whenever she meets us riding or walking. Most of the Secession ladies, though, have good enough manners to refrain from any such demonstrations. Love to Father, Anna, and Nellie. Ever your loving son, Robert G. Shaw All of Shaw's wishes would come to fruition: Fort Donelson and Savannah were captured within days, and Gen. Ambrose Burnside would have full control over Norfolk within weeks after the March 8th ironclad showdown in the Battle of Hampton Roads in which the Union's USS Monitor defeated the Confederate CSS Virginia (aka the Merrimack). This fully opened the area to serve as a base of operations for Gen. Burnside to launch an expedition on North Carolina's coast. Outside of these letters, the only proof of Shaw’s presence in town is within a small article that appears in the Frederick Examiner newspaper on February 19th, 1862. The lieutenant’s name is mentioned with others who made up a court-martial tribunal that was meeting in the newspaper’s office. Today this exact location is better known to Fredericktonians as The Orchard restaurant on the southwest corner of North Market and West Church Streets. On February 22nd, 1862, George Washington’s birthday was celebrated in fine form here in Frederick, complete with a grand review of the Union Army on Market Street. We are lucky to have a few photographs of that momentous occasion in the archives of Heritage Frederick (the former Historical Society of Frederick County). One was taken just outside the previously mentioned Examiner Building. The grand marshal was Col. Edward Shriver with whom Shaw had spent time while here. Could Robert Gould Shaw be pictured among the Union men captured in the photographs on Market Street? We’ll never know. On Sunday, February 22nd (1862), resident Jacob Engelbrecht penned in his diary the following passage: “Today Washington’s birthday was celebrated by the people of Frederick by the ringing of bells & firing of cannon by the military. Two flags were presented by the ladies of Frederick to the First Maryland Regiment under Colonel William P. Maulsby. The presentation was made by James T. Smith & received by William P. Maulsby. Addresses made by both. The different regiments in our neighborhood were present on the occasion numbering 4 or 5,000 who paraded through the streets. The presentation was made at the veranda of the Junior Hall where nearly all the staff officers were. Major General N. P. Banks, Colonel Geary, General Abercrombie, &c were present. After the presentation the “Star Spangled Banner” was sung—led by William D. Reese. And Mrs. General Banks sung in style. Among the singers your humble servant was among the singers and I would remark that I sang the same old “Star Spangled Banner” a few weeks after it was composed say about October 1814.” The next day, Lt. Shaw and his regiment were given orders to be ready in one hour’s notice, with three day’s cooked rations, and cartridge boxes filled. A fellow soldier from Massachusetts, named Henry Newton Comey, wrote in a letter: ”The wagons started off immediately as did the artillery and pontoons. We expected to leave about that time as well, but alas we did not. We later heard that the pontoons, floated by canal from Washington, were too wide for the canal locks at Harpers Ferry, and could not get into the river. Our departure came on February 27th, when we abandoned Camp Hicks after breakfast. At 4:00am, the 2nd, Rgt. Slogged through the wet boggy ground which laid between the camp and the road, and marched into Frederick. From there we took railway cars southwest to Sandy Hook.” At this point the regiment crossed the Potomac and spent the night in the empty houses on Shenandoah Street (Harpers Ferry). Over the next seven months, Shaw fought with his fellow Massachusetts soldiers in the first Battle of Winchester, the Battle of Cedar Mountain and at the bloody battle of Antietam. Robert Gould Shaw served both as a line officer in the field and as a staff officer for Gen. George H Gordon. Twice wounded, by the fall of 1862 he was promoted to the rank of captain. It’s fascinating to think that Shaw walked the streets of Frederick. He would have traveled by Mount Olivet regularly, and I’d bet money that he strolled through Mount Olivet at least once. If anything else, we have several folks interred here that shared conversation, libations, meals and social interaction with this brave young soldier, destined for "Glory." If you've never seen the movie of the same name (Glory), please make a point to watch as you will witness Shaw's promotion to the rank of colonel and the rest of his amazing story--one shared with the brave men of the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Ironically, Col. Robert Gould Shaw doesn't have a marked gravesite. He was buried in a mass grave at Fort Wagner, South Carolina along with his fallen troops. He is remembered in his hometown with the famous bronze-relief sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and located at the edge of Boston Common. Shaw also is honored with a cenotaph in nearby Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed