|

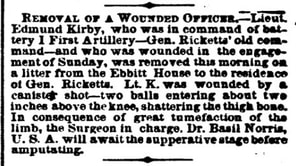

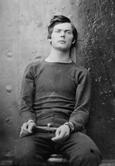

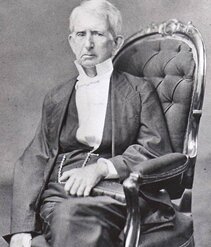

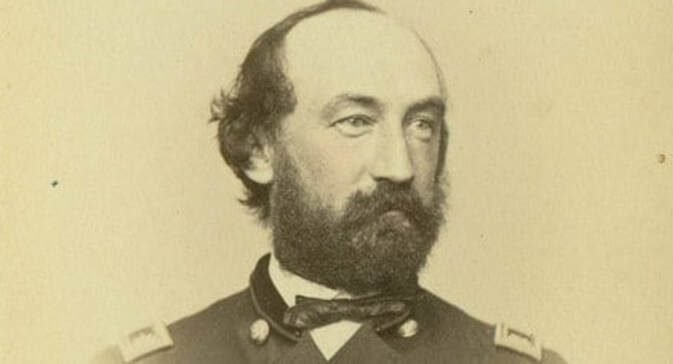

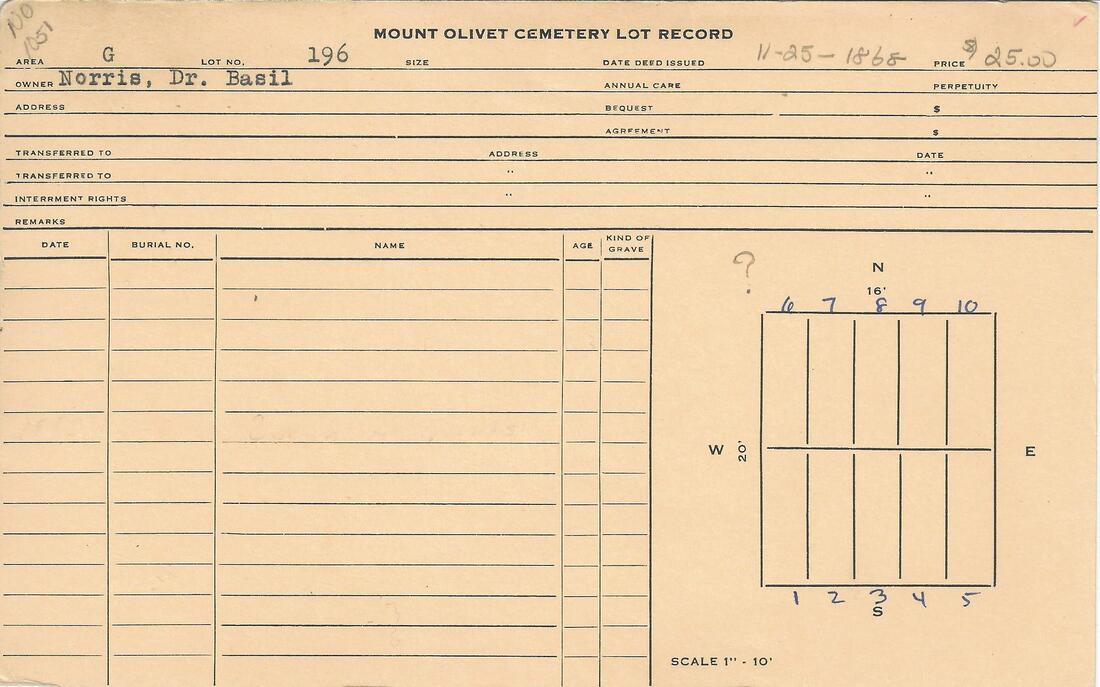

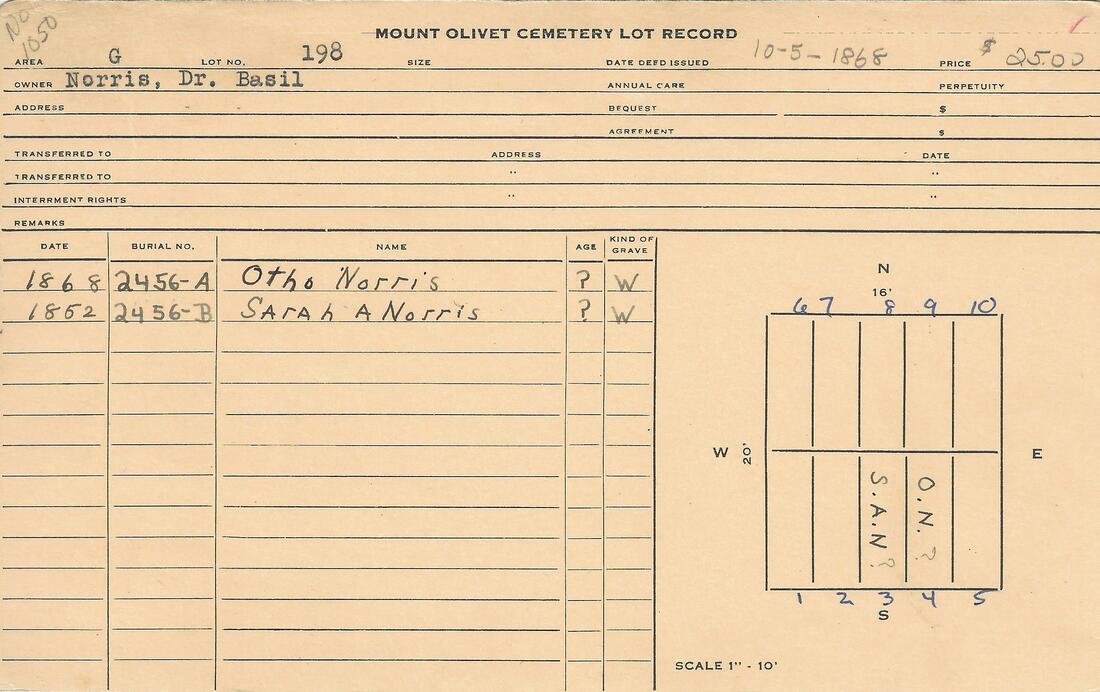

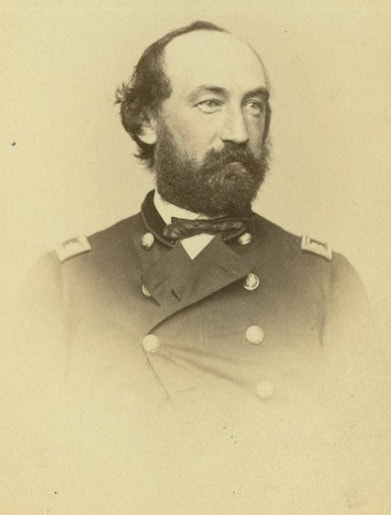

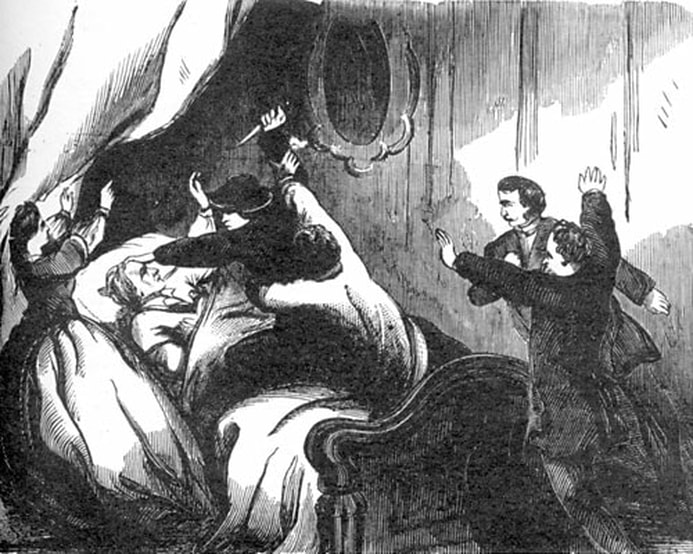

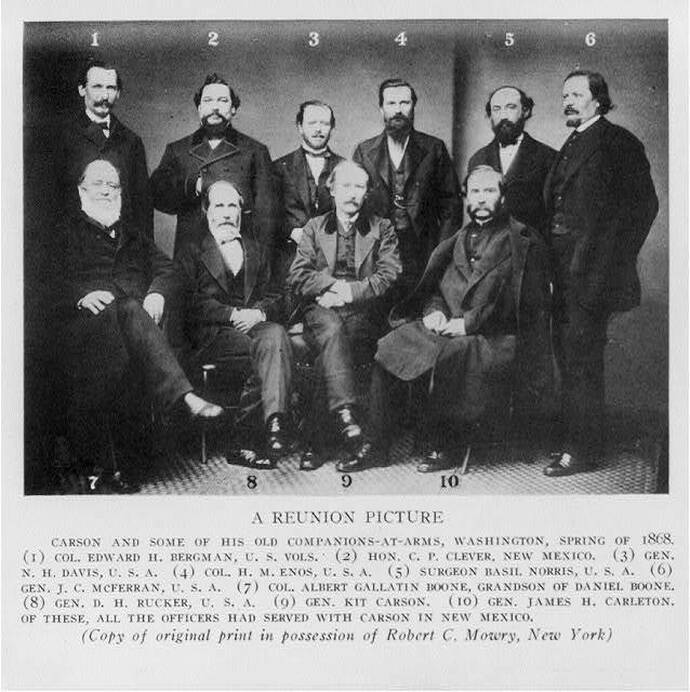

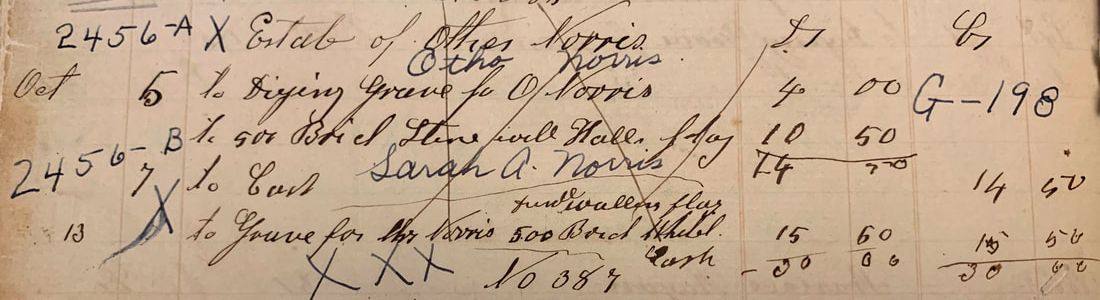

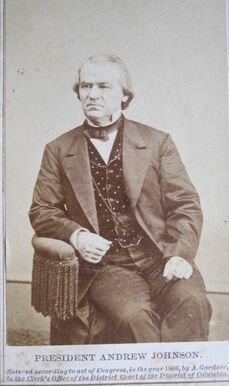

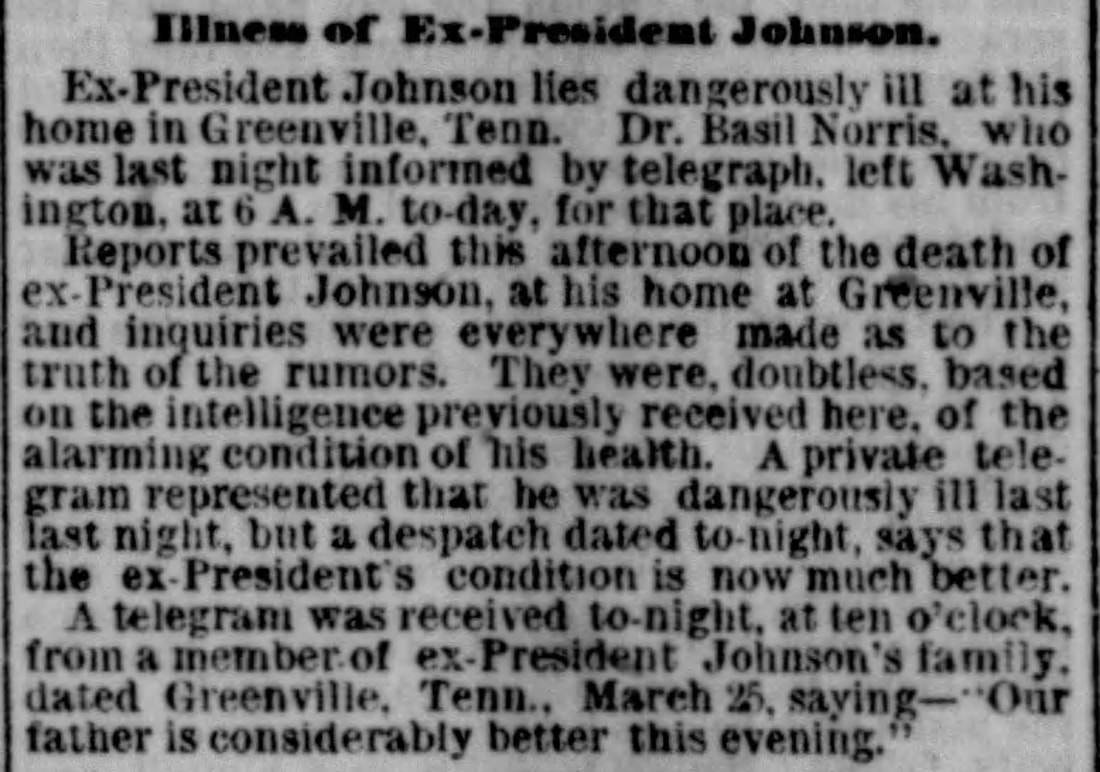

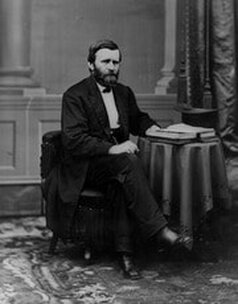

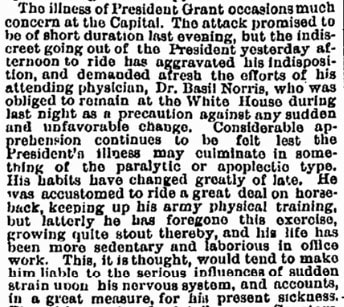

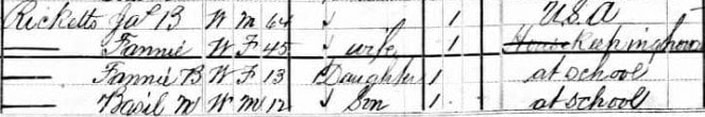

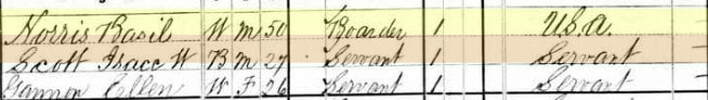

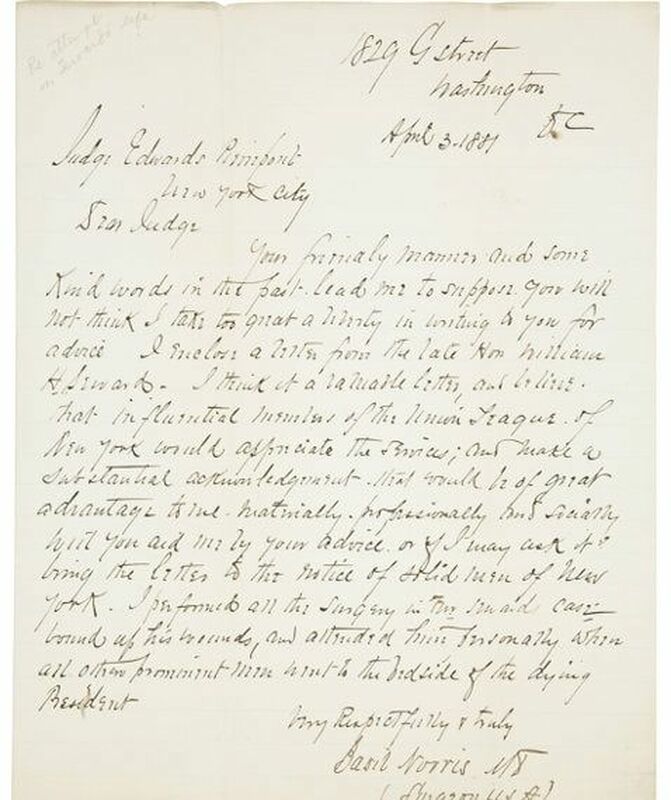

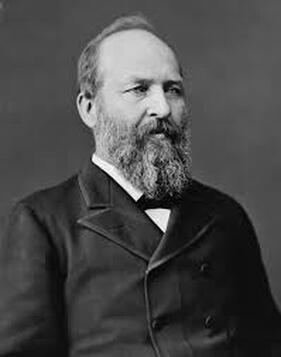

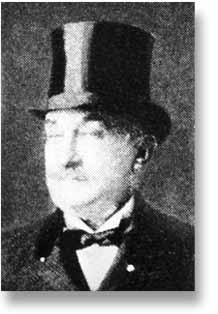

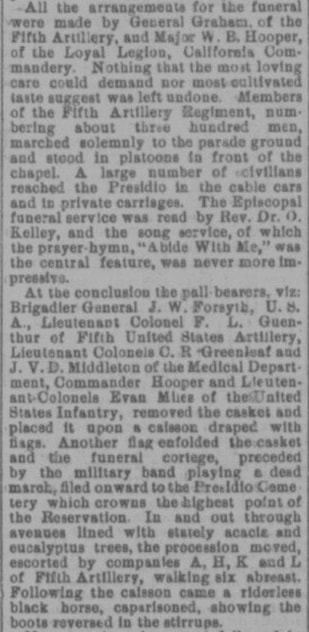

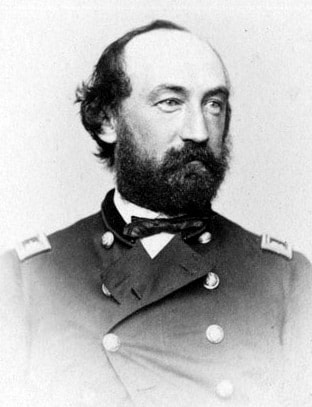

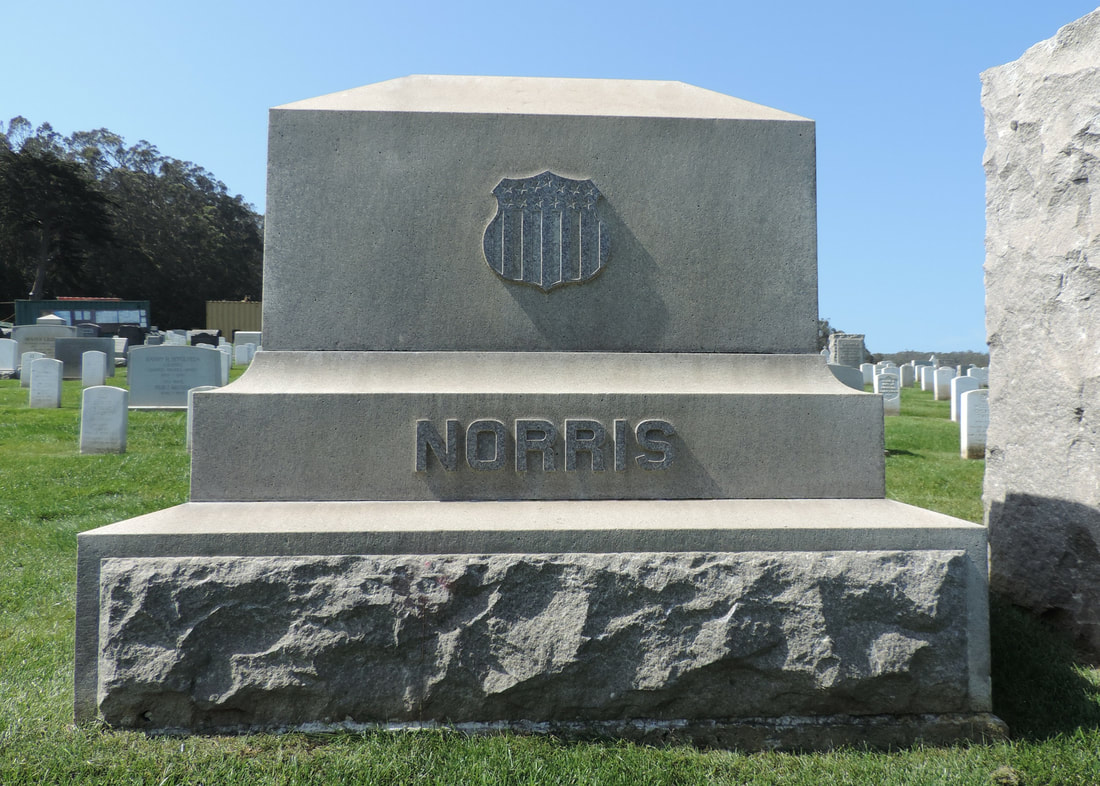

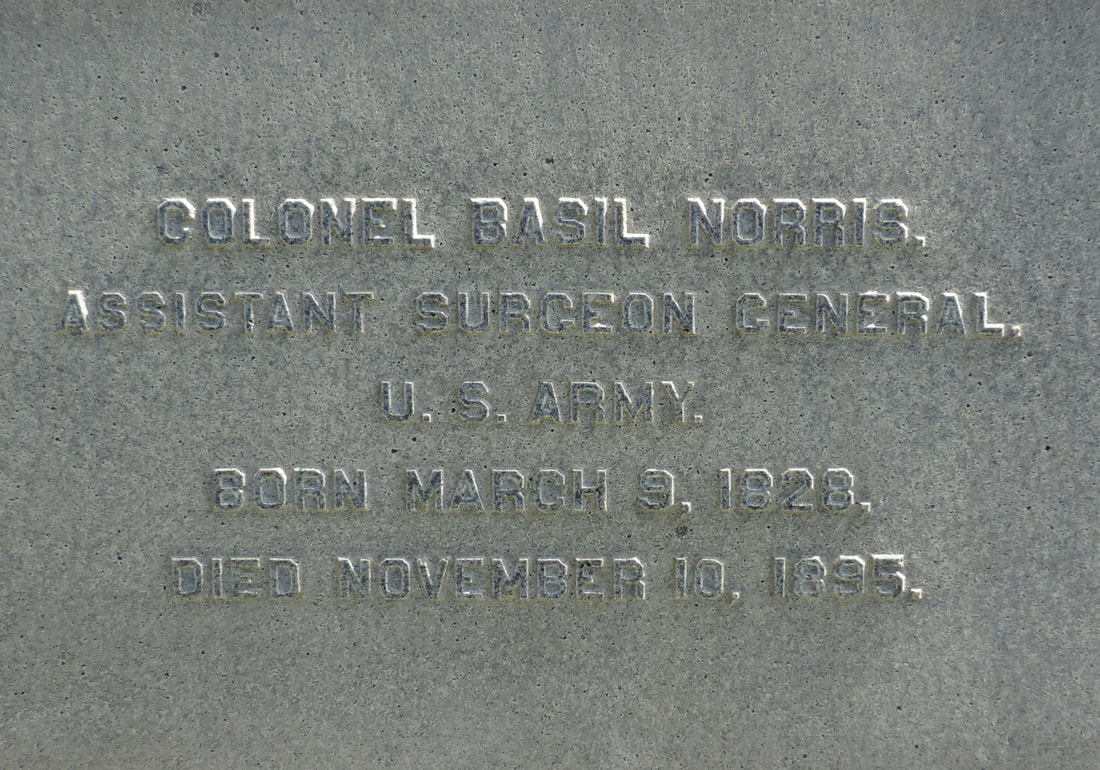

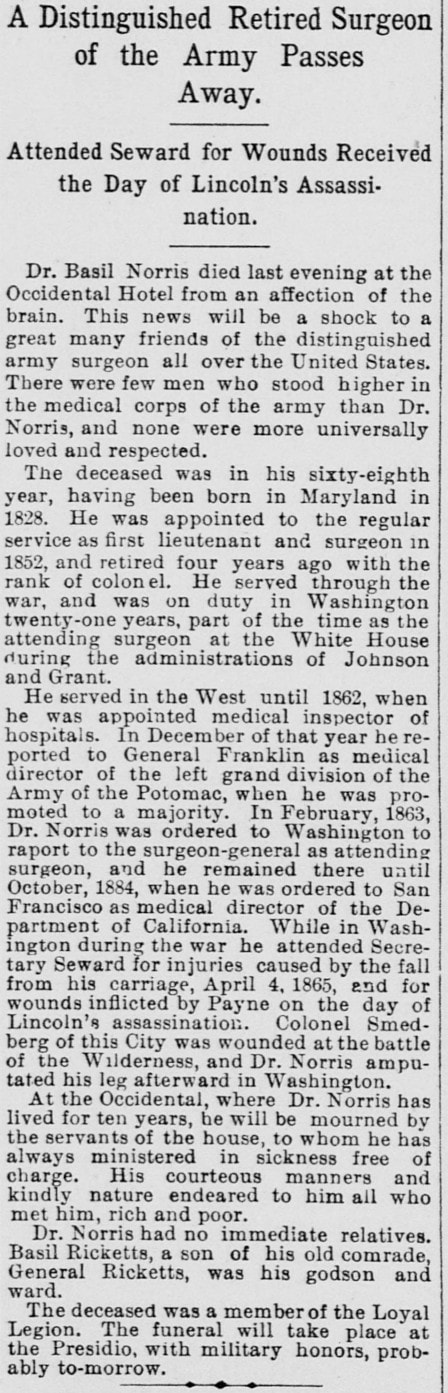

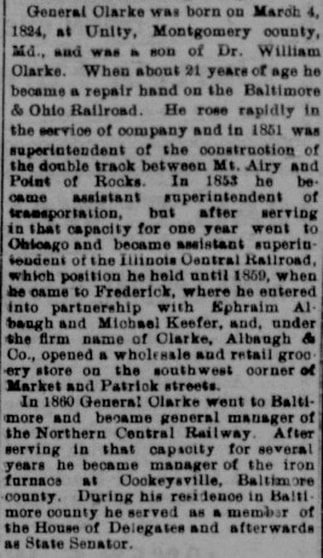

So the premise of our blog is clearly based on the “memorialization power” a gravestone, monument or plaque can wield. You can find them formed out of marble, granite, slatestone, and even white bronze. Most are beautiful works of craftsmanship, some representing bonafide works of art and magnificent architecture. No matter how grand or petite, each grave marker stands as proof that a particular human being once walked this earth between the given birth date (or year) and death date carved upon its surface. The particular individual’s journey could have taken them across the country, or to another continent. Meanwhile, there are others who perhaps never ventured outside of Frederick County. Regardless of your spiritual beliefs, the end of the respective “road” for the mortal remains of over 40,000 people is right here in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. Gravestones are important touchstones to relatives and future generations to come. They are also invaluable to folks like me and countless other researchers in trying to decipher what happened during “the dash” that appears between those birth and death dates on the face of a stone.  Norris sisters' monument in Area F/Lot 12 Norris sisters' monument in Area F/Lot 12 Back in January, 2017, I performed some research in an effort to locate the first monument erected in our cemetery. This event occurred in May, 1854, just a few weeks before the formal opening services of the cemetery and the first interment—Mrs. Ann Crawford. The beautiful twin-columned monument of Parian marble was placed on the new gravesite of two teenage sisters who had died a few years earlier, and had been originally interred at the All Saints Protestant Episcopal burying ground located along Carroll Creek. The individual responsible for commissioning this outstanding grave marker was Basil Norris (1788-1865), the girls’ father and a successful grocery store operator that once stood in the first block of W. Patrick St. When doing my research, Mr. Norris’ name seemed somewhat familiar to me in some fashion. Upon further review, I realized that I had seen the name of another Basil Norris who was a member of the Union’s Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. This individual was a noted surgeon during the conflict, and afterwards served in the capacity of presidential physician, or better put—a physician utilized by a few of our US presidents. Once I read that fact, I sort of lost my focus on the Norris sisters and their inaugural monument, and took aim on Basil Norris, the surgical soldier. I looked in our Mount Olivet database to see if Dr. Norris was buried here, and soon found that he bought two entire grave plots in the fall of 1868. Each plot consisted of 10 individual grave spots, all located in Area G. In my excitement, I drove out to inspect the site, but only found one large monument on the easternmost lot of the two in Norris’ name. Both grave plots were what we call “feature lots,” front road burial locations adjacent one of the drives or avenues of the cemetery. The large monument referenced before was that of Otho Norris (1799-1868) and wife, Sarah Ann (McElfresh) Norris (1805-1852). There were also corresponding footstones for the couple, but clearly no sign of Basil Norris the Union officer. Not finding anything, I had a fleeting thought to myself that perhaps his grave was unmarked? I went back to my office and got back in our cemetery database. My mystery physician was clearly on electronic record and listed as occupying space #1 of Area G’s Lot 196. However cemetery superintendent Pearcey would tell me that this was simply a facet of our computer data program, and Dr. Norris may not be buried there at all. Each plot-holder has to attached to a cemetery lot for the program’s search engine to work properly. He told me to check the official interment cards, as they tell the true story. Here I found that Dr. Norris also purchased Plot 198 as well (to the left of #196 in picture above). It’s generally a rarity that a lot-holder would not be buried in his or her plot, but this could possibly be a “dummy” read which would soon be confirmed. Find-a-Grave.com showed me that Col. Basil Norris, M.D. (1828-1896) was buried in San Francisco’s famed national military cemetery—the Presidio. Shortly thereafter, I found a footnote in our records that said the same thing. Irony was certainly at play as our cemetery’s first monument, and likely that of our most famous “missing monument” are tied to gentlemen possessing the same name (Basil Norris), and in the same family. As a matter of fact, Basil the Civil War surgeon was the nephew, and namesake, of Basil the merchant, which was really all I needed to know for that story two years ago. Ever since, I have been curious as to why Basil bought 20 lots (2 full plots) in 1868, but was buried on the other side of the country. I also wondered what was Col. Basil’s relationship to Otho and Sarah Ann Norris? Lastly, I still lament the fact that the famous doctor is not here as it would make such a great tie-in to Frederick’s Civil War Medicine legacy told so wonderfully at our downtown museum (National Museum of Civil War Medicine). So, I apologize that it’s not a legitimate Mount Olivet “Story in Stone,” but since Col. Basil Norris was a minor celebrity, along with being a major cemetery lot-holder, why not tell his “Story not in Stone.” Besides, this blog’s initial publishing comes so close to April Fool’s Day, so what the heck. Col. Basil Norris The son of Otho Norris and Sarah Ann (McElfresh), Basil Norris was born in Frederick County on March 9th, 1828. His father was a merchant in town, and the family seems to have had strong connections to the Libertytown-Unionville area in the northeast part of the county. The Norris’ were members of All Saints Church, but I haven’t located their home in town as of yet. Basil was named for his uncle, whom we introduced earlier. The young man served as class secretary and graduated from the University of Maryland’s medical school in 1849. He entered into the US Army in 1852, and served with troops in Texas, Utah and New Mexico during the decade which followed the Mexican-American War.  Evening Star, Washington DC (May 7, 1863) Evening Star, Washington DC (May 7, 1863) Basil Norris returned east in 1862 during the intensity of the American Civil War. He was first appointed medical inspector of hospitals. Soonafter, Norris was promoted to the rank of Surgeon in 1863 and appointed Medical Director of one of the grand divisions of the Army of the Potomac. Interestingly, Dr. Norris would apply for a transfer from his post with the US Army of the Potomac, finding: “…my duties here are not important. These duties can be performed by volunteer surgeons, quite as well by me. In Santa Fe, I could add to my income by private practice and my appointment would be agreeable…“ Norris was eventually stationed as the attending physician of officers of the regular army and their families in the City of Washington from 1863-1884. He also maintained a private practice as well. For meritorious services, Basil Norris would be raised to the rank of Lieutenant–Colonel in 1882 and, and finally Colonel in 1888.  Lincoln conspirator Lewis Powell Lincoln conspirator Lewis Powell On the night of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Norris had been at Secretary of State William H. Seward’s bedside earlier in the evening, treating his private patient for a double fracture of the upper jaw caused by a carriage accident which occurred a week earlier. Later that night, John Wilkes Booth’s conspirator, Lewis Powell, attacked the secretary in his bedroom on that ill-fated night of April 13th, 1865. Norris returned that night and treated Seward for his new wounds which could have proven fatal. He continued his intensive care of the secretary over several weeks to follow.  William H. Seward recuperating after the assassination attempt on his life William H. Seward recuperating after the assassination attempt on his life I found an official public commendation in the form of a resolution by the New York State Senate in regards to Col. Norris’ care of Secretary of State Seward. This was found in the 1883 Journal of the Senate’s proceedings. Here, a letter written by Secretary Seward to Col. Norris in July 1870 was read to the body and recorded for posterity: “Dr. Basil Norris, Surgeon U.S.A.: My Dear Sir—I cannot doubt that I have long since made you understand, in our pleasant social intercourse, how lightly I appreciate the surgical skill and care with which you treated me in the year 1865 when I fell under the blows of an assassin, inflicted while I was lying helpless in my bed in my own house at Washington. A season of rest, however, which I long desired, and needed, has come to me at last, and I am improving it as well as I can by performing personal domestic and social duties which were neglected when I was engaged in the public service. It seems to me to be an important duty of this kind to record, in a manner that may be lasting, my acknowledgements of the appreciation which I have mentioned of the gratitude I owe you as a savior of my life, of my profound respect and of my sincere and affectionate esteem. —William H. Seward” The testimonial gave thanks to Col. Norris for saving Seward’s life in 1865. This is especially interesting because Norris’ actions would make possible Secretary of State Seward’s greatest career achievement two years later. The United States purchased Alaska on March 30th, 1867. Seward brokered the deal with Russia for $7 million, which equaled two cents an acre. The deal almost didn't pass the Senate and was mocked in Congress. They called the new territory “Seward's Folly” or “Seward's Icebox.” The rest is history, and our native son had a hand in it, per se. Basil Norris bought his Mount Olivet burial plots on the occasion of his father’s death on October 3rd, 1868. His mother Sarah Ann had passed back in November, 1852. Son Basil made the burial arrangements for his father, and at the same time, had his mother re-interred here from All Saints Protestant Episcopal burial ground. Another note of interest is that I found the widowed Otho living with his brother, Basil Norris (the grocer) in the 1860 US Census. He likely lived with them up through his death. Presidential Encounters Basil Norris subsequently became the physician for Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson and his family. Johnson suffered from recurrent kidney stones during his abbreviated tenure as president through early 1869. His ailment was described by a colleague: ”Afflicted with gravel, he found no cessation from pain, and but little relief in standing while at work for hours in preference to remaining in a sitting posture, or from a variety of an occasional “fit of the grave with its excruciating torture.” This malady was both serious and episodic, and it felled the president in the summer of 1865, and again in the late winter and spring of 1867. Johnson, in order to obtain relief, “had taken to working at a high desk, standing up.” Just weeks after leaving office, Andrew Johnson became extremely ill in March, 1869, probably from a recurrence of renal stones. Col. Norris expeditiously traveled to the ex-President’s home in Greenville, Tennessee, where Johnson eventually wrote: ”…In my extreme illness after my return from Washington, when my life had been despaired of, your presence at my bedside, after so short a notice, seemed almost to be the work of magic power.” The military surgeon from Frederick would return from Tennessee and tend to the personal needs of newly-elected president Ulysses S. Grant and his family. This continued for the next eight years. During this tenure, however, Norris became embroiled in a debate between civilian members of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia and those army and navy members who maintained private medical practices in Washington. This was 1877, and Norris became a major figure in the question of whether a military physician could ethically provide professional care to a civilian, even though that civilian was the former US commander in chief. (Fifteen years later In 1892, US Surgeon General Charles Sutherland ordered that the tradition of civilian practice by Army doctors be discontinued.) President Grant, and his family, suffered from no significant illness during their eight years in the White House. Grant, upon departing the presidency, expressed to Col. Norris his “…gratitude and that of his family for your many acts of kindness and professional attendance in every case occurring with us for the past eight years.

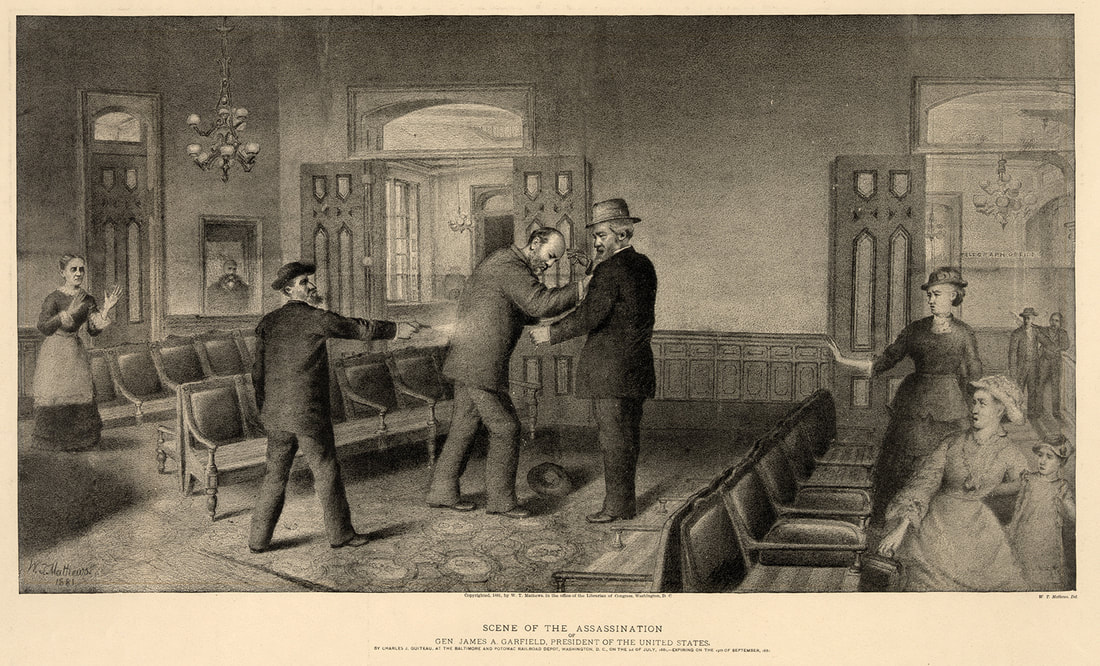

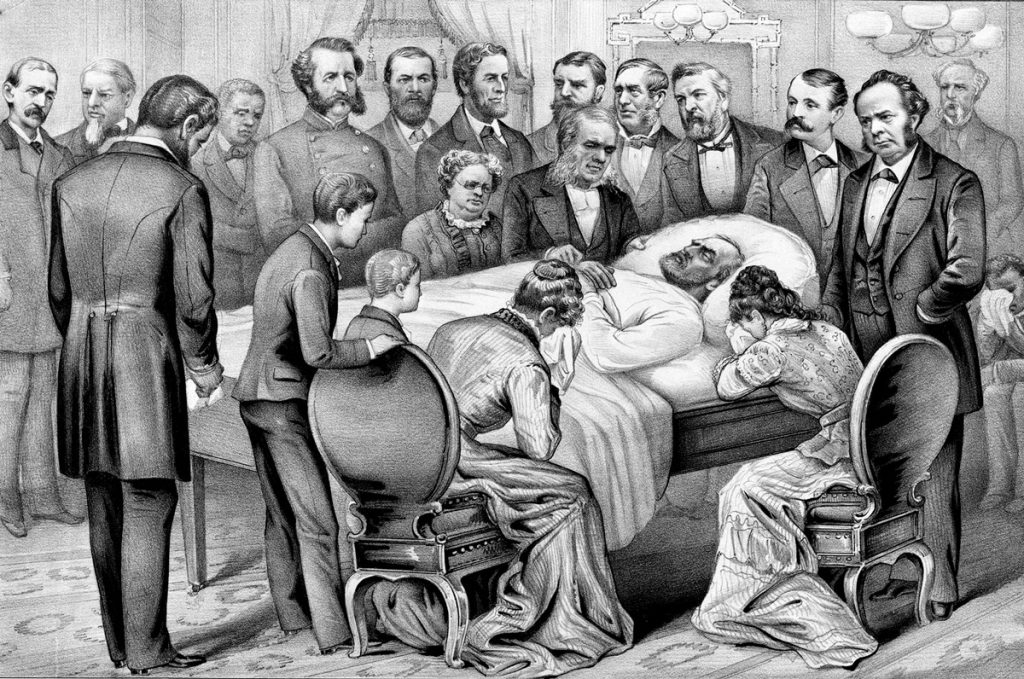

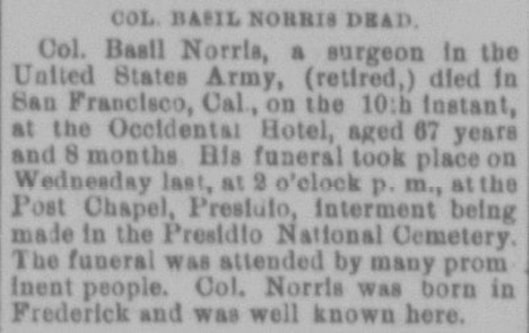

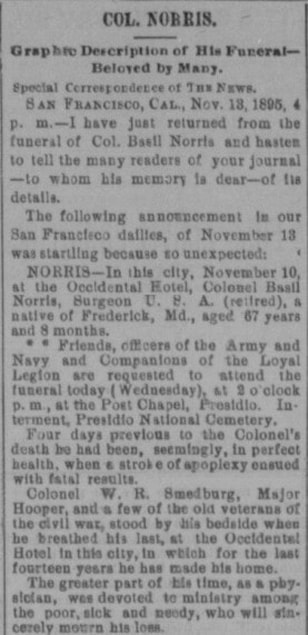

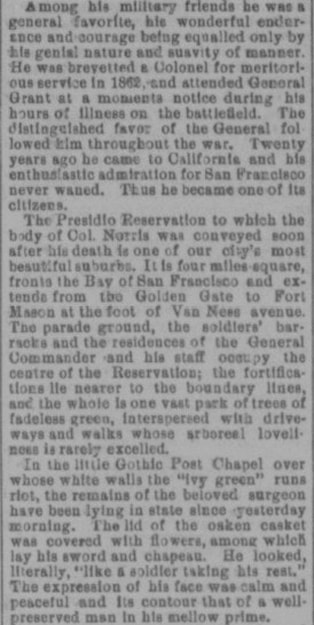

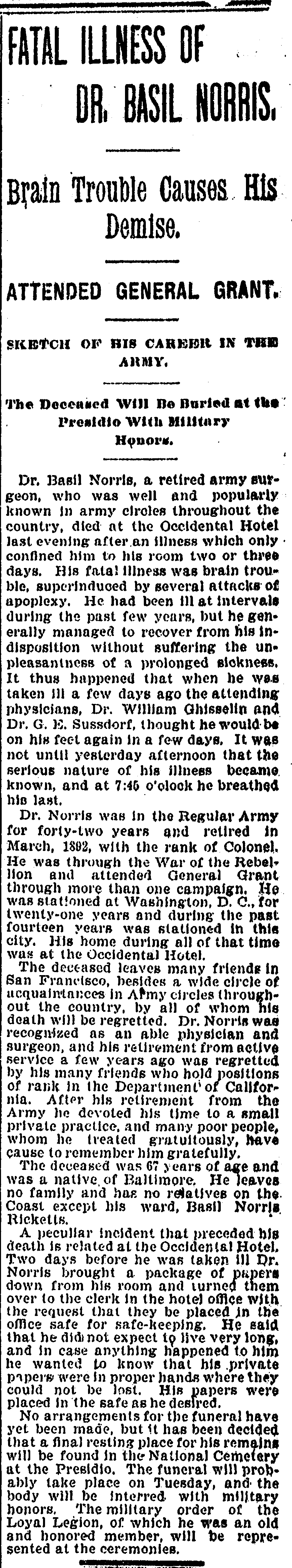

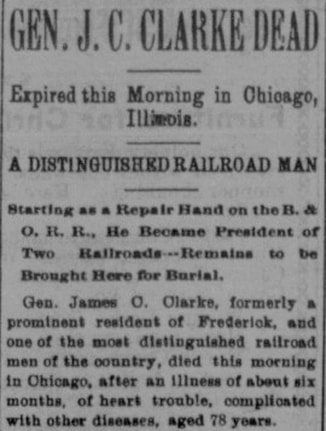

Historians agree that massive infection was a significant factor in President Garfield's demise. Norris wasn’t the principal physician on the scene, but was among the group. The president recuperated for a few months, but finally succumbed to infection and blood poisoning on September 19th, 1881, the second US president to die from an assassination attempt. In 1884, Col. Basil Norris left the nation’s capital after a 21-year stint. He relocated to San Francisco, California to serve as Medical Director of the US Army’s Division of the Pacific. He took up residence at San Francisco’s Occidental Hotel. Col. Basil Norris retired from the military in 1894 but kept his private practice in which it is said that he helped provide medical care to San Francisco's poor and indigent. His medical writings are said to have been numerous and scholarly. He was described as having been a genial man, an accomplished physician and an efficient officer. Norris died of apoplexy in San Francisco on November 11th, 1895.

Additional obituaries featured in the San Francisco papers

2 Comments

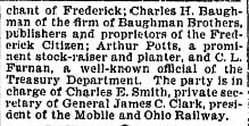

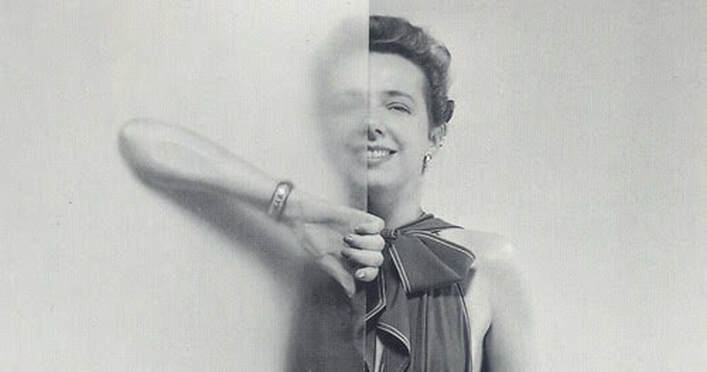

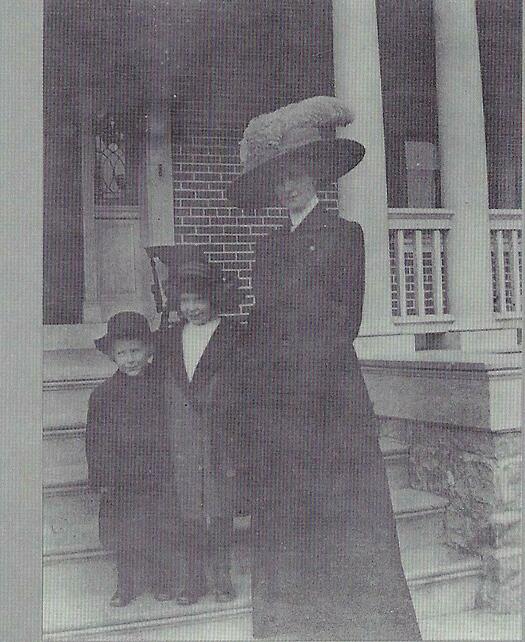

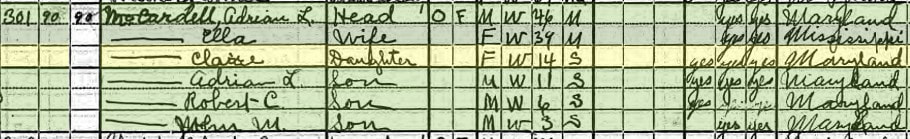

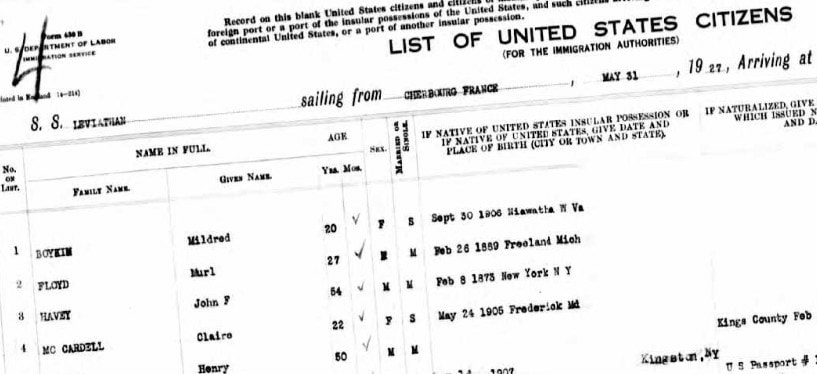

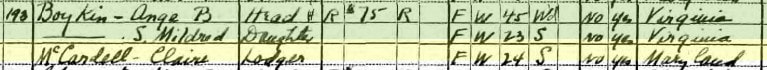

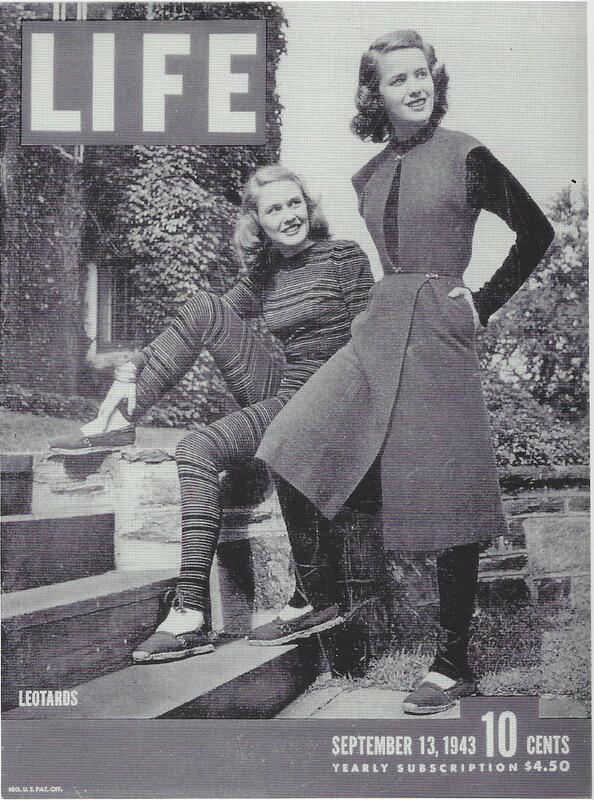

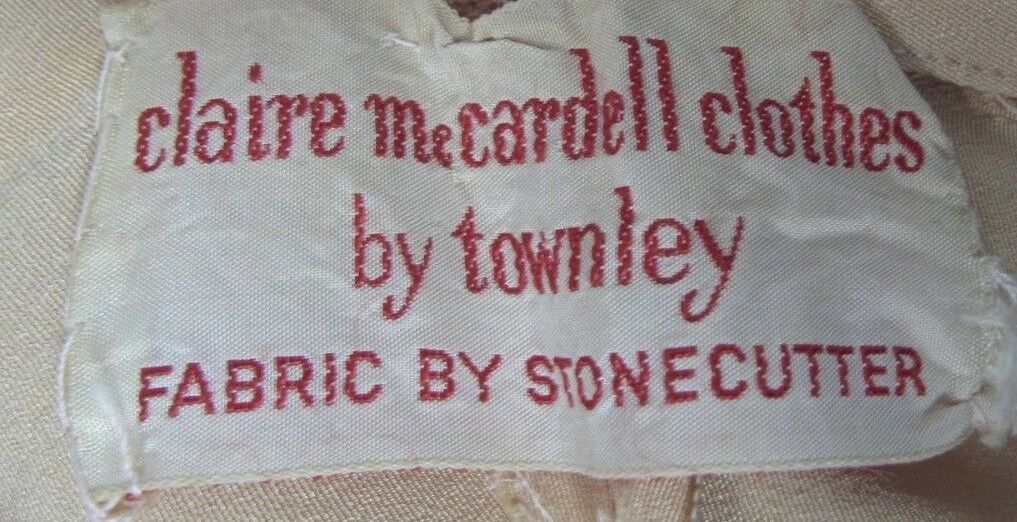

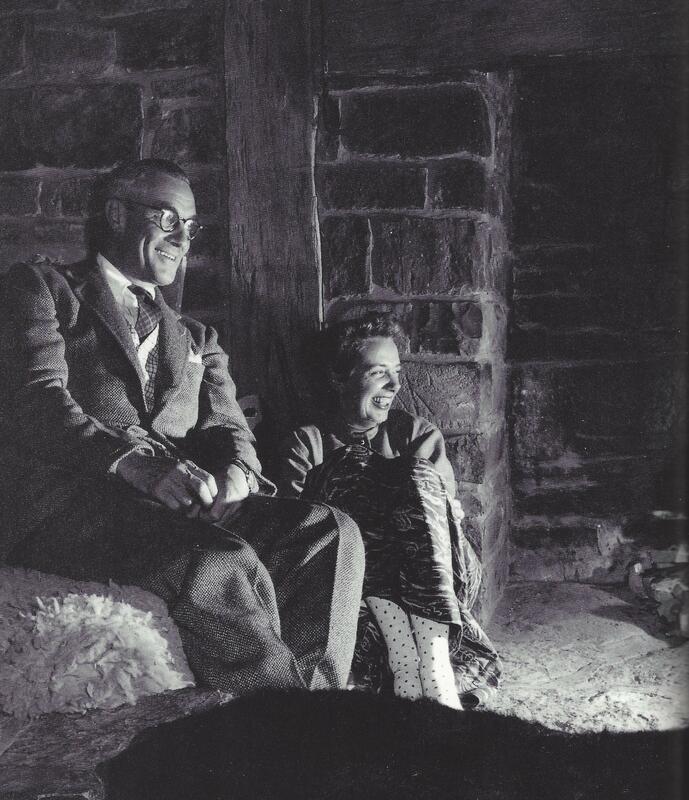

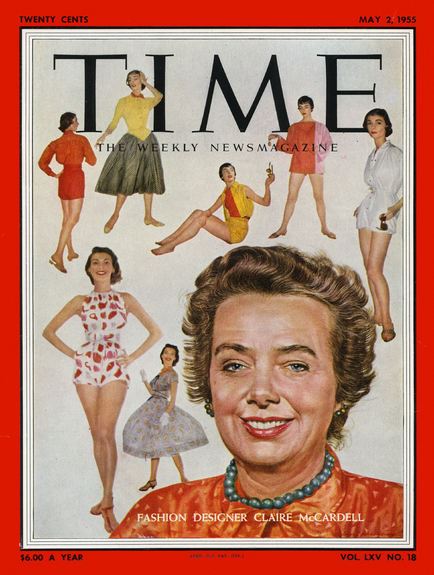

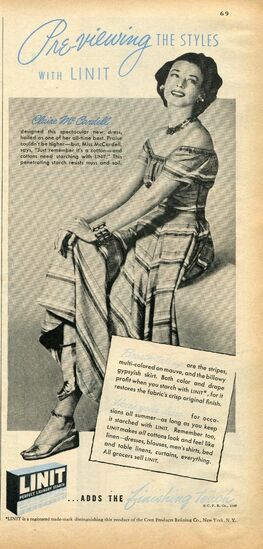

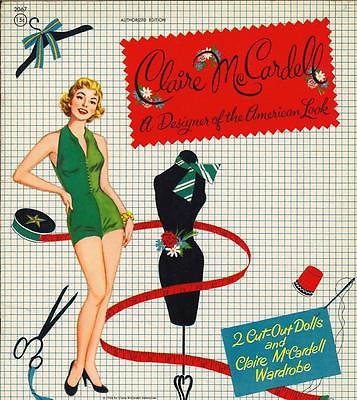

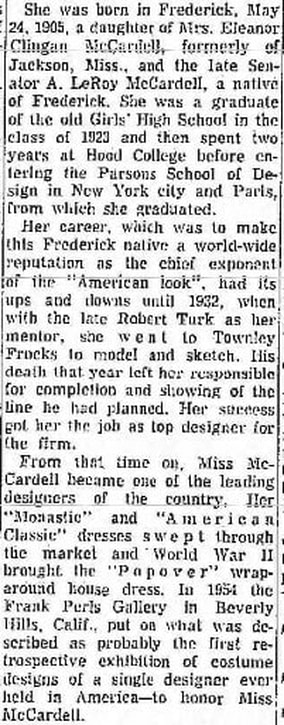

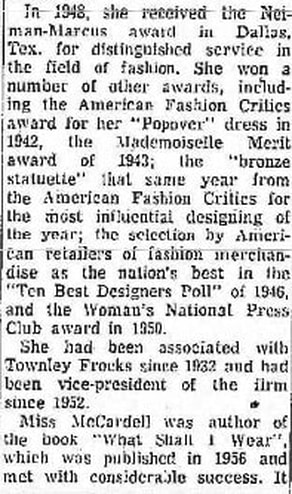

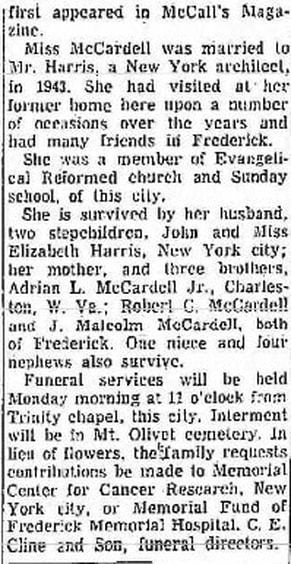

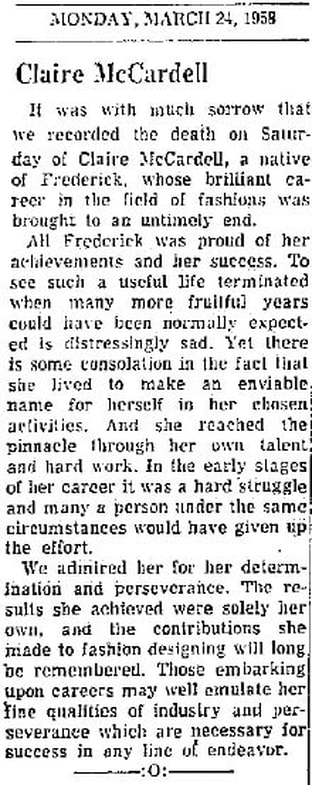

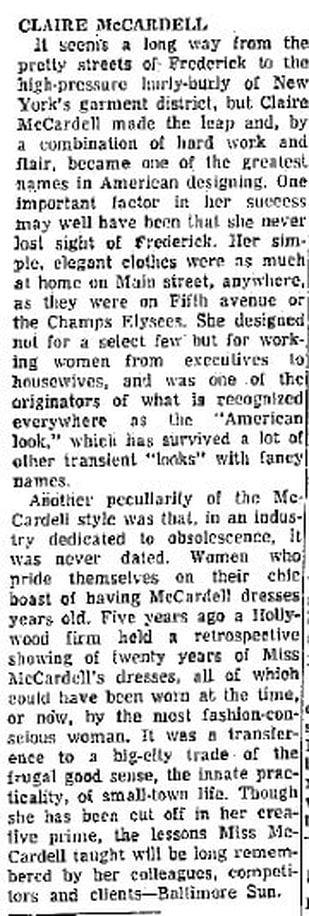

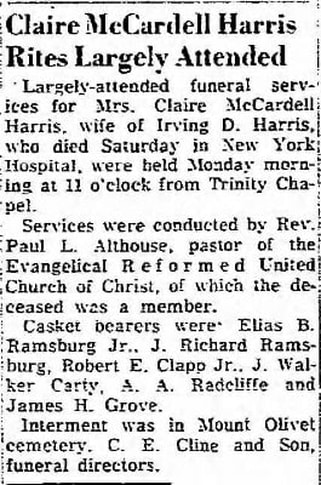

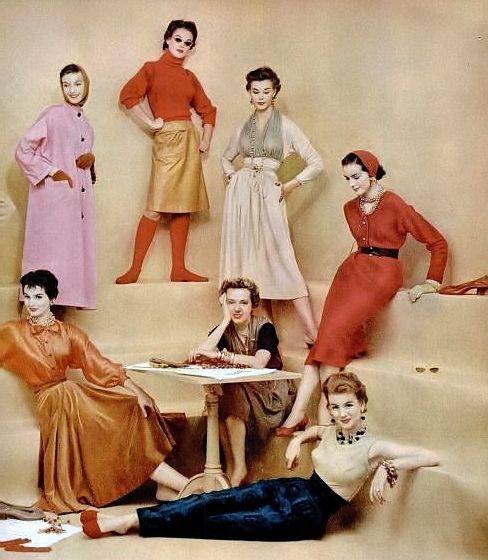

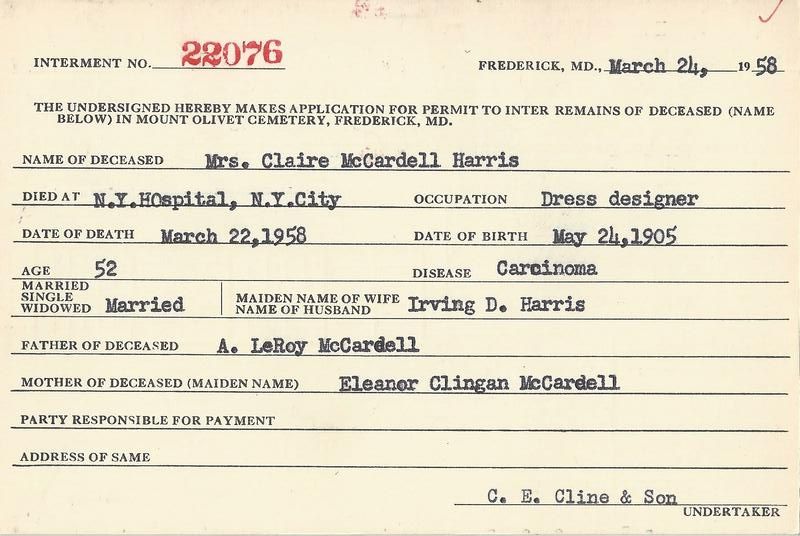

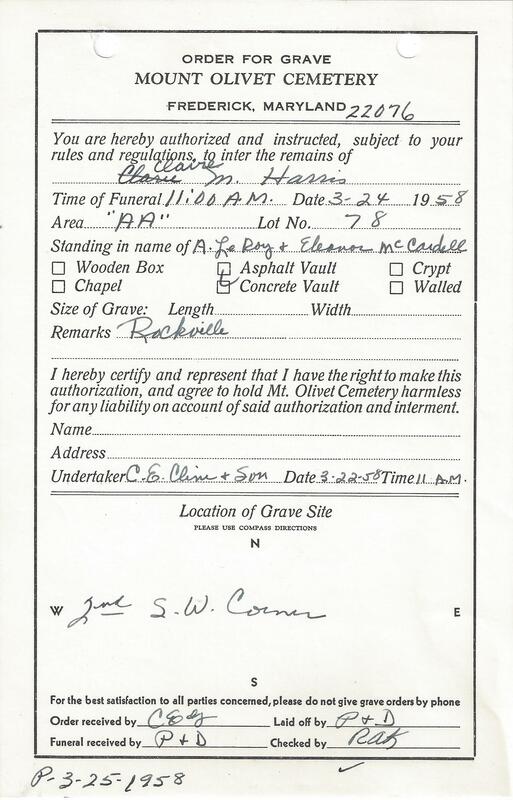

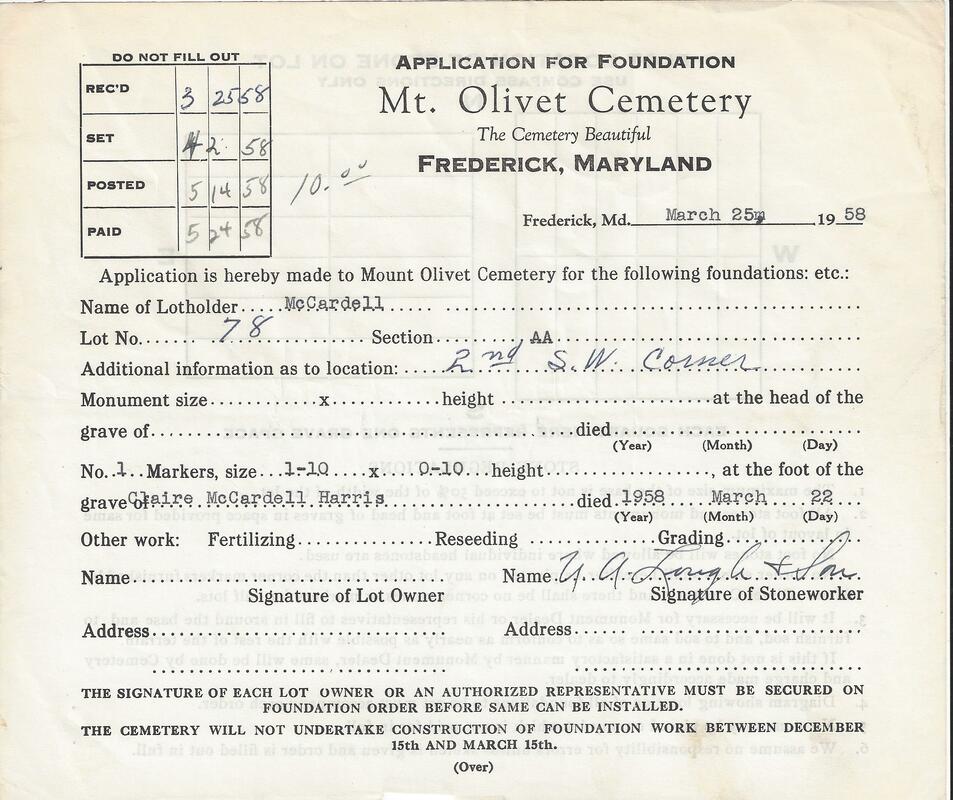

Claire McCardell (1940) Claire McCardell (1940) Well it’s Women’s History Month, and there is certainly no shortage of outstanding individuals here in Mount Olivet Cemetery to feature in this week’s “Story in Stone.” Women’s History Month had its origins as a national celebration in 1981 when Congress passed a public law which authorized and requested the President to proclaim the week beginning March 7th, 1982 as “Women’s History Week.” Throughout the next five years, Congress continued to pass joint resolutions designating a week in March as “Women’s History Week.” In 1987 after being petitioned by the National Women’s History Project, Congress passed another law which designated the month of March, 1987 as “Women’s History Month.” Back to "monumental" women in our cemetery, one of the best examples is already known to many Fredericktonians and those interested in the history of clothing and fashion design. Most people, however, have never heard of a woman named Claire McCardell Harris. This is unfortunate because the ingenuitive, Frederick native is credited with revolutionizing women’s fashion, and helping to create what would be coined “the American Look.” This all began roughly 90 years ago. Whether you are a fashion aficionado or not, many of us are familiar with designer names such as Calvin Klein, Donna Karan, Gianni Versace, Vera Wang, Tommy Hilfiger, Coco Chanel, Ralph Lauren and Christian Dior. It’s just too bad that the same is not true about Claire McCardell Harris, or simply Claire McCardell as she was more commonly known. This wasn’t always the case as Claire was revered internationally in her heyday of the 1930’s-1950’s. She was a Frederick girl who made an impact on the world with her creations.  There has been plenty written about Claire McCardell over the years. In my opinion, I put one work, in particular, at the top of the list—a fine book, published in 1998 and written by Kohle Yohannon and Nancy Nolf (Carl) entitled Claire McCardell: Redefining Modernism. This 151-page hardcover is steeped in illustrations and photographs and tells the life story of Ms. McCardell Harris from her childhood in Frederick up through her death from colon cancer on March 22nd, 1958 at the age of 52. Author Yohannon was an art and design historian and faculty member of Claire’s alma-mater of the Parson’s School of Design in New York, and the late Ms. Carl was a former faculty member and historian of Hood College, where Claire spent two years at the start of her collegiate career. You can purchase this book on Amazon, along with one penned by Claire, herself, back in 1956 entitled “What Shall I Wear?” The descriptive review on the website reads as follows: First published in 1956, What Shall I Wear? is a distillation of McCardell’s democratic fashion philosophy and a chattily vivacious guide to looking effortlessly stylish. Mostly eschewing Paris, although she studied there and was influenced by Vionnet and Madame Gres, McCardell preferred an unadorned aesthetic; modern and minimalist, elegant and relaxed, even for evening, with wool jersey and tweed among her favorite fabrics. What Shall I Wear? provides a glimpse into the sources of McCardell’s inspiration―travel, sports, the American leisure lifestyle, and her own closet―and how she transformed them into fashion, all the while approaching design from her chosen vantage point of practicality. More relevant than ever is McCardell’s sensible advice on how to cultivate a wardrobe of long-lasting, durable pieces, a vital approach to style for those looking to offset the cost of the modern fast-fashion economy. A retro treat for designers and everyone who loves fashion―vintage and contemporary―and teeming with charming illustrations and timeless advice for finding your own best look, creatively shopping on a budget, and building a real wardrobe that is lasting, chic, and individual, What Shall I Wear? is a tribute to the American spirit in fashion. A more recent article about Ms. McCardell appeared a few months back in the December 12th edition of the Washington Post Magazine. Many anecdotes from the above two works were utilized by author Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson in an article entitled: A Dress for Everyone: Claire McCardell took on the fashion industry — and revolutionized what women wear. So, at best, I will make a feeble attempt of giving a brief overview instead of trying to recount the life, times, and triumphs of this revolutionary fashion designer. The fore-mentioned resources will provide a much richer story. Claire McCardell designed for the emerging active lifestyle of women in the 1940s and ’50s. She was the originator of mix-and-match separates, open-backed sundresses, and feminine denim fashion. Ms. McCardell started the trend for ballet flats as a solution to a wartime leather-rationing measure. Spaghetti straps, brass hooks and eyes as fasteners, rivets, menswear details and fabrics can also be credited to the former Frederictonian. Claire’s Monastic and Pop-over dresses achieved cult status, and her fashions were taken up by working women, suburban housewives, and high society ladies alike. Claire McCardell was born May 24th, 1905 in Frederick to Adrian Leroy and Eleanor "Ella" M. (Clingan) McCardell (originally from Jackson, Mississippi). She was the oldest in her family and had three brothers: Adrian, Robert and John. Mr. McCardell was a state senator and president of the Frederick County National Bank. His father, Adrian C. McCardell, was a native of Williamsport, MD and confectioner who was running a successful sweet shop on N. Market Street at the time of his granddaughter's birth. Claire's grandfather also had strong ties with Mount Olivet as he served as the cemetery's president from 1919 until his death in 1932. Claire's family lived on Rockwell Terrace, the fine suburban neighborhood on the city's northwest side. From the age of five, Claire was interested in fashions, demonstrated by the clipping of paper dolls from many of her mother’s fashion magazines. By the time she was in her teens, Claire was dismantling her clothes, and those of her siblings in an effort to remake them herself. After graduating from Frederick High School in 1923, Claire attended Hood College for two years. In 1926, she left to study at the School of Fine and Applied Arts in New York City for three years. This institution eventually became known as the Parsons School of Design. The curriculum involved two semesters of study in Paris, which made quite an impression on the Marylander. She was accompanied by friend Mildred Boykin, a fellow student of Claire's who also had ambitions as a fashion designer. The two would be lifelong friends. In late 1928, Claire finally obtained her first job as a fit model in the French Room at B. Altman’s department store in New York. In the 1930 census Claire can be found living with Mildred and her mother on E. 30th Street (near 5th Avenue) in New York City. In 1929, Claire started her career with Robert Turk, an independent designer and dressmaker. Turk’s untimely death led his company to be absorbed by Townley Frocks, where Claire later became chief designer. During World War II, she designed the “Pop-Over” dress and soon introduced leotards which were dubbed by Life magazine as “funny tights.” She received two American Fashions Critics’ Awards and a Coty Award. Claire married her longtime boyfriend, Irving Drought Harris, an architect from Texas. This was in 1943, and in doing so, the former Miss McCardell became a step-mother to Harris’ children (John and Elizabeth) from a former marriage. Claire is said to have often shunned Harris’ ambitious New York social life whenever possible. She was more comfortable living in the humble surroundings of her rustic country farm retreat in Frenchtown, NJ. McCardell’s design prowess was so esteemed that in 1955 she partnered with some of Europe’s best artists, like Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, and Joan Miro, using their fabric designs with her garments for a feature in LIFE Magazine. That same year Claire landed the cover of Time, only the third fashion designer to have done so. In 1956, she wrote her book, “What Shall I Wear?” Claire was not only at the top of her field, but she was also a marketable commodity, often sought for bringing modern and stylish credibility to other products. Sadly, the end of life was near. Claire would be diagnosed with colon cancer. She continued to work, but the disease slowly took its toll. A popular story has been recounted involving an event in the winter of 1958 as the designer was bed bound in a New York hospital. Claire insisted that her dear friend Mildred Boykin (Orrick) help her attend a final showing of her clothes, most of which had been designed while in the hospital. The pair was successful in making a stealthy escape, and attended the premiere as desired. Apparently, Claire took the stage at the conclusion of the show, and received a hearty, standing ovation from the audience, media members and runway models. In just a few short months, Claire McCardell was gone--dead at the age of 52. This made front page news back home in Frederick. The “Frederick fashionista” was mourned by not only her family, friends and industry, but by generations of women who purchased and collected her clothes. The Coty American Fashion Critics' Awards Hall of Fame awarded Claire a posthumous induction later that year. The Townley company, who had made her a partner in 1952, closed soon after her death. Even though offers to pick up the McCardell line came from multiple directions, the McCardell family decided to let the brand name die with the designer, rather than sell it off to someone else.

In the early 1980’s, spurred by renewed interest in McCardell, Lord & Taylor department store reissued a line of McCardell-inspired dresses. Examples of Claire's fashions have been featured in museum exhibits at such places as the Metropolitan Museum of Art (NY), the Fashion Institute of Technology (State University of New York), the Maryland Historical Society and Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising (Los Angeles). The advent of the internet has helped reintroduce Claire (and her work) to later generations through blog articles and portfolio pieces. Even eBay has played a role, as auctions of McCardell clothing items are a regular occurrence, with original vintage dresses selling from $150-$2,000. As Kohle Yohannon and Nancy Nolf-Carl say in their book (Claire McCardell: Redefining Modernism) “Claire McCardell was a pioneer in minimalism, an innovator of modernism, and throughout her short but influential career she provided women with designs that stressed comfort, practicality, and integrity.” Thankfully, Claire McCardell Harris is still remembered today and her popularity seems to be growing again. It’s not difficult to see why she is considered a lady with outstanding vision of informed fashions that are enjoyed by young girls and ladies today. It is again amazing to think that she is buried here in Mount Olivet, back in her old home town—as charming as it was in her time…but arguably more modern and stylish thanks to our mastery of adaptive reuse of historic buildings and public artwork;) She’d be proud, I’m sure.

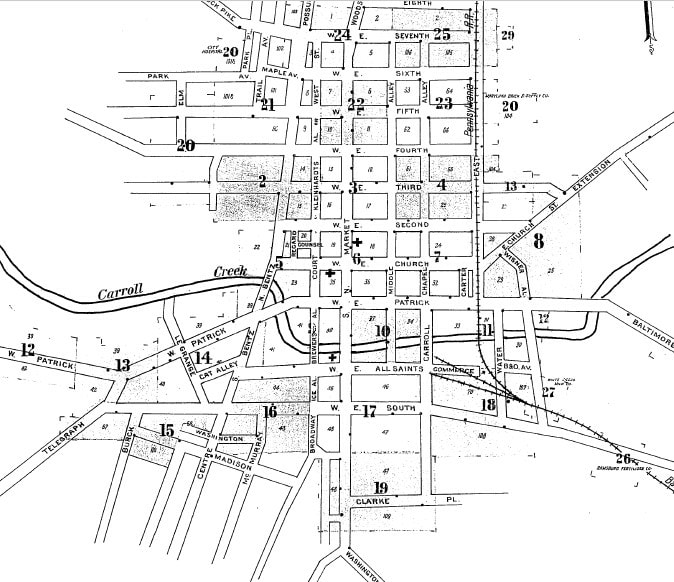

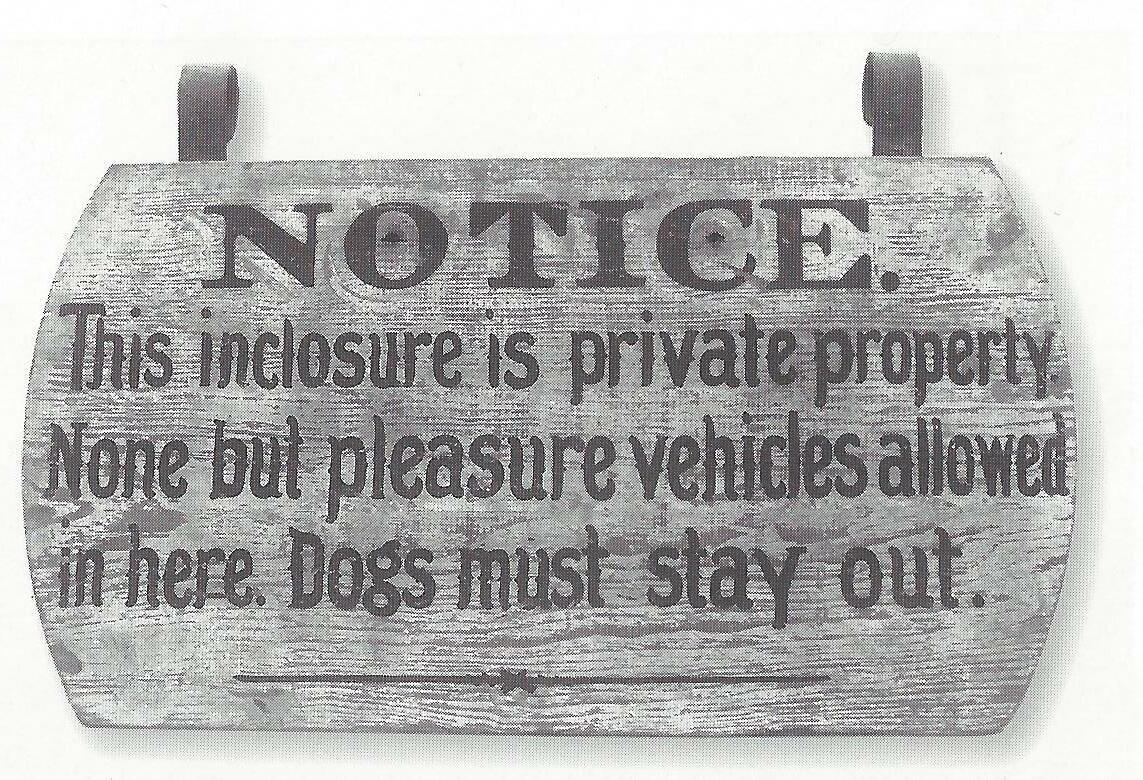

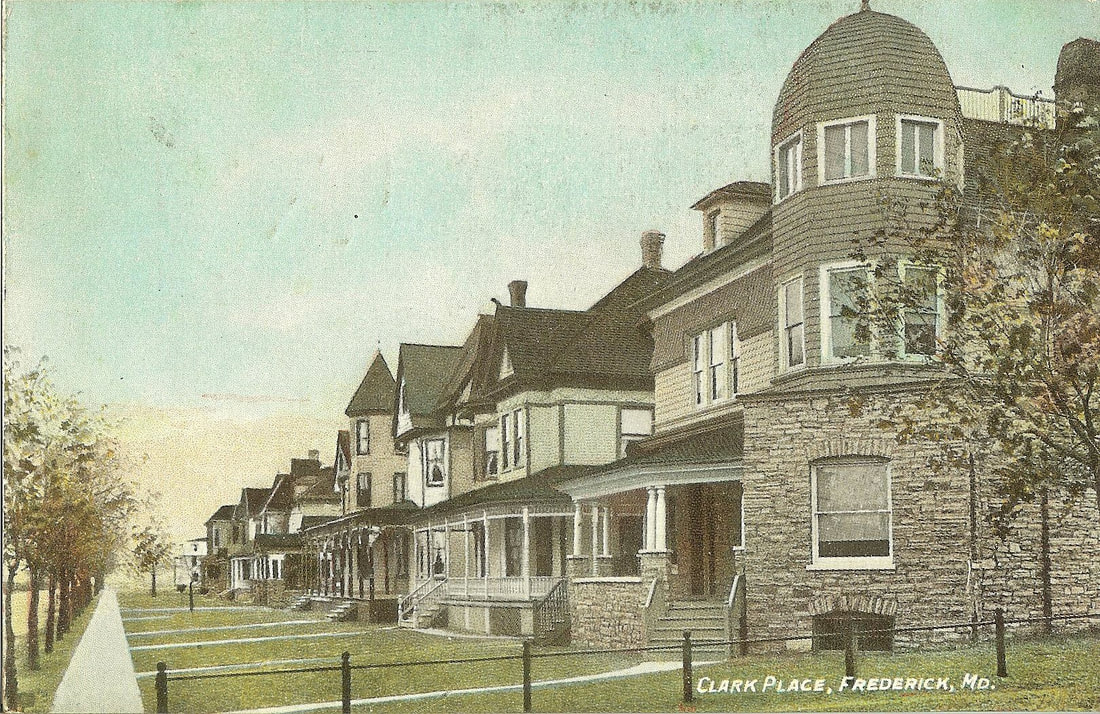

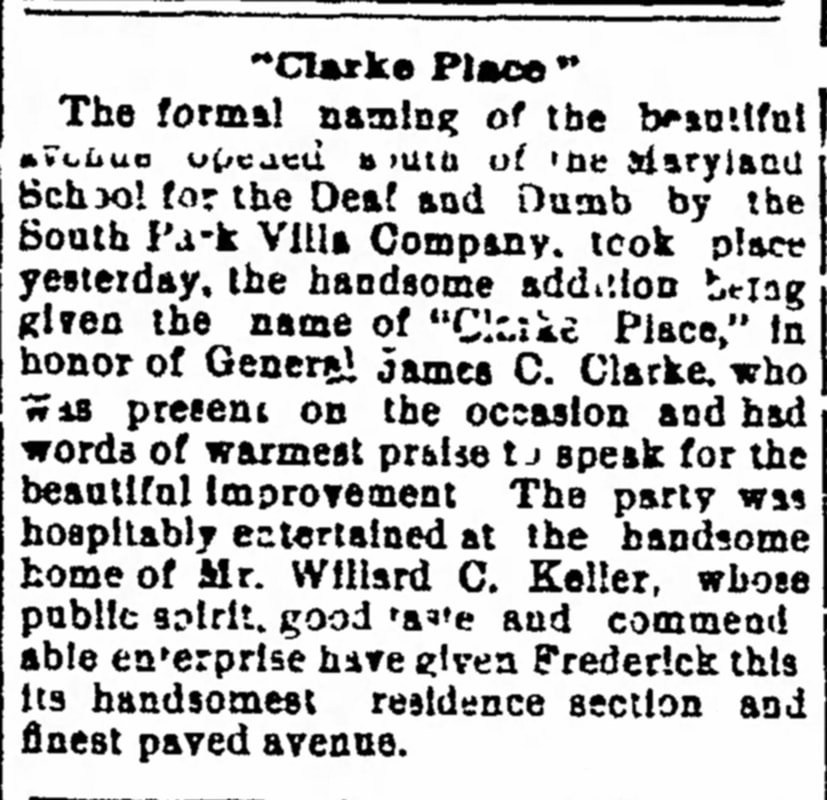

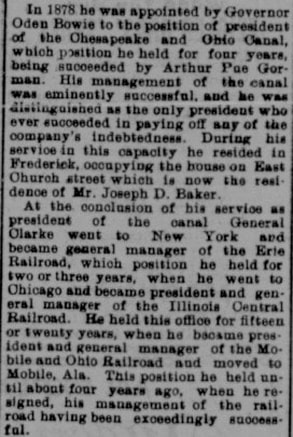

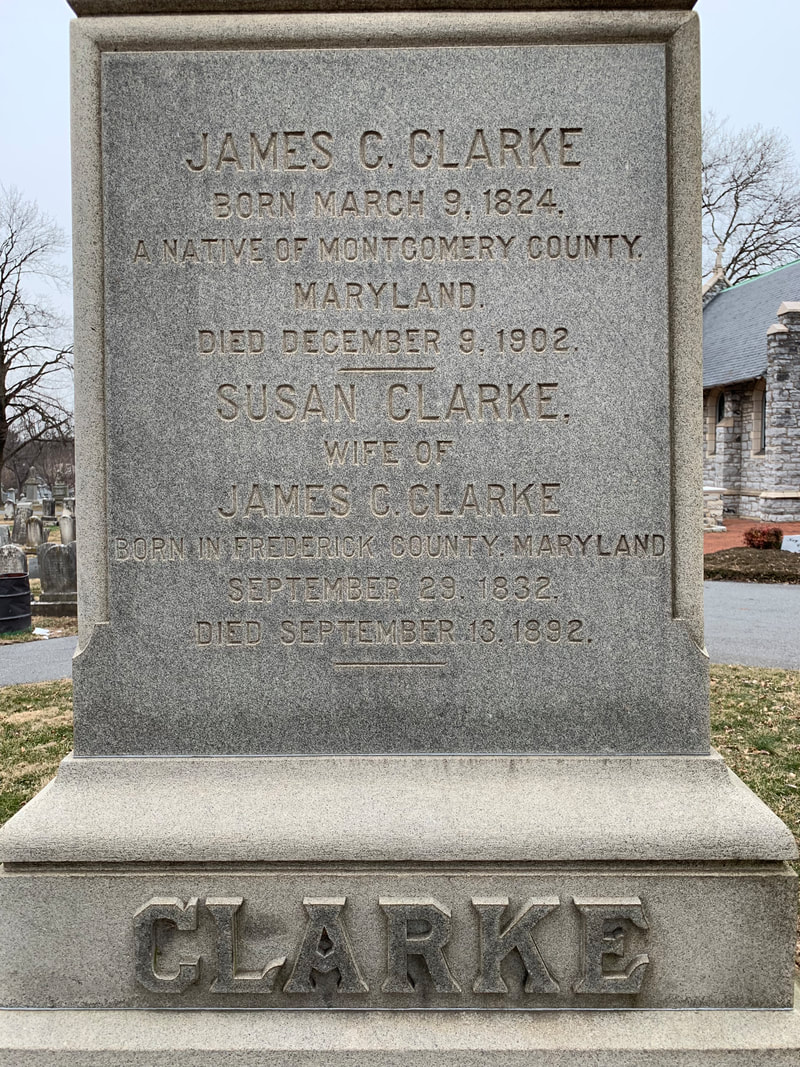

You can’t go anywhere these days and not hear about “walls.” It reminds me of an interesting local history tale that deals with the genesis of Frederick’s first, gated community. Many think this would have to be a more current occurrence, but it happened in the late 1800’s, and apparently was a happenstance created by two key ingredients: milk and cobblestones. The locale was positioned of Frederick’s southern city limits, not far from our cemetery, actually only about a 100 yards north from Mount Olivet’s front gate. Here one can find Clarke Place, a short avenue that connects S. Market St. eastward to S. Carroll Street. Along the way, fine examples of Victorian-era architecture line the south side of the thoroughfare. To the north is the campus of Maryland School for the Deaf, resting atop the footprint of what remains of the Frederick “Hessian” Barracks compound atop aptly named Barracks Hill. A large, farmstead once sat to the south of the school, and was owned by Dr. Bradley Tyler. This eventually came into the possession of Mr. Harry W. Bowers and the South Park Villa Company. Mr. Bowers was a land developer and also a Clerk of the Circuit Court of Frederick County. The South Park Villa Company hired John F. Ramsburg to survey a series of residential building lots on the north boundary of his property in the year 1894.  Former home of Harry and Anna Bowers Former home of Harry and Anna Bowers Mr. Bowers built the first house on the block, a brick structure. Soon others would follow, utilizing some of the most creative designs of the day. Features employed included broad front porches, turret-like towers and gingerbread trim. The vicinity quickly became one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in town. It predated Rockwell Terrace and the major College Park development that would eventually bolster the northwest side of town a few decades later, built adjacent the new campus of Hood College. To add to the grandeur, Clarke Place was one of the only paved secondary roads in town. Of course, we are not talking about the use of macadam here, but rather, cobblestones. Well the old story, whether apocryphal or not, goes that a milk wagon, pulled by horses, traversed Clarke Place to deliver dairy products to customers on the street. More so, the road provided a shorter route for said vendor to make his way back to the milk plant (on the east side of town), without having to backtrack through Frederick’s center city. Apparently more than one neighbor got perturbed with the daily clanking of hoofs upon the cobblestone drive early each morning. And if the milkman was using this as a short-cut, odds are there were plenty more. This quandary eventually led to an iron-clad solution to keep the riff-raff out as rail fencing went up on both ends of Clarke Place. Talk about your “crying over spilt milk! Another interesting anecdote comes from a gentleman named Melvin M. Engle (1903-1984), one-time vice-president of Mount Olivet’s Board of Directors. Mr. Engle grew up on the proverbial “other side of the tracks,” among the many blue-collar families residing in townhouses along S. Market Street. He told our cemetery superintendent, Ron Pearcey, that on more than one occasion, he and his buddies would be playing ball on S. Market and an errand hit, or throw, would put their baseball in the trajectory of Clarke Place and the other side of the railed fence. As one of the lads sheepishly went to retrieve said ball, old Mrs. Anna Bowers, usually parked on her front porch, was already in hot pursuit of the round, stitched and leather-bound intruder. She would lay claim to the ball being on her property, and promptly took it into her home amidst the begging of the boys. This usually put an abrupt end to the sporting forays of the neighborhood children. Just as Clarke Place was imposing to many Frederick residents, old and young, the grave monument and memorial to the street’s namesake is equally awe-inspiring. With no further adieu, let me introduce to you, Gen. James C. Clarke, whose reputation and career seem to be more than fitting to deserve the 30’ obelisk that rests atop his mortal remains, and those of his family.  Gen. James C. Clarke Gen. James C. Clarke James C. Clarke James C. Clarke was a true “rags to riches” success story, rising to the pinnacle of his profession. He was described as “a rough and ready railroader, tall and strong with a can-do attitude—a master storyteller and loved by all.” Clarke was born March 9th, 1824 in Unity, Maryland (within Montgomery County). His parents were Dr. William Clarke and Elizabeth “Betsy” Simpson. James’ father came from Newtownards, Ireland, located in County Down. His mother’s family (the Simpsons) originally came from southern England. Dr. Clarke would gain employment with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad when it was extending its line into Frederick County in the late 1820’s. Simpson family historian Sharon Chrisafulli paints a colorful picture of the early childhood of our subject in her online Graveyard Rabbit blog from 2012: “Betsy Simpson Clarke was very spoiled and high spirited. They were aristocratic, descending from Worthingtons and Ridgelys, and quite wealthy, owning many slaves. M. William Clarke was very amiable and endeavored to please her but she would frequently fly into a rage and seeking revenge would set free some of the slaves. Finally, Mr. Clarke would leave her and his family, never to return. Betsy, in time, became poor and at 12 years of age, James C. Clarke stopped his schooling at Point of Rocks (MD) to seek employment. He called on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal but was refused work due to his young age. James pressed on telling he had a mother to support. They admired his courage and started him as a water boy. By age 16, he was a mule driver of a canal boat and held the position for four years eventually rising to the owner of a boat, which sunk in a collision.”

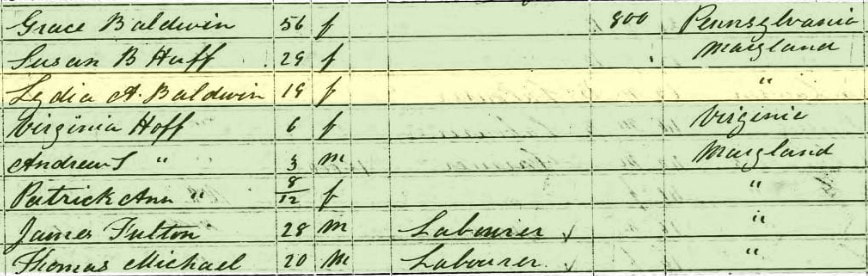

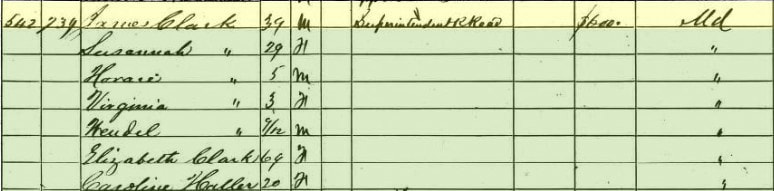

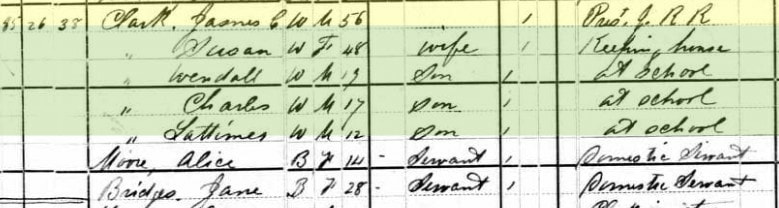

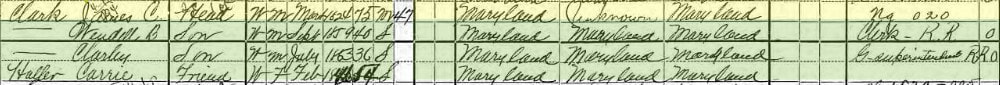

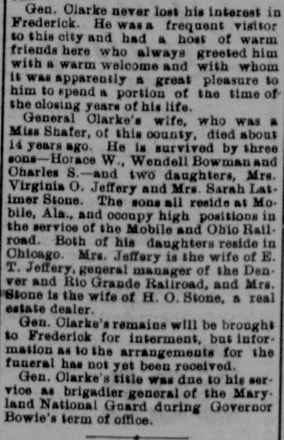

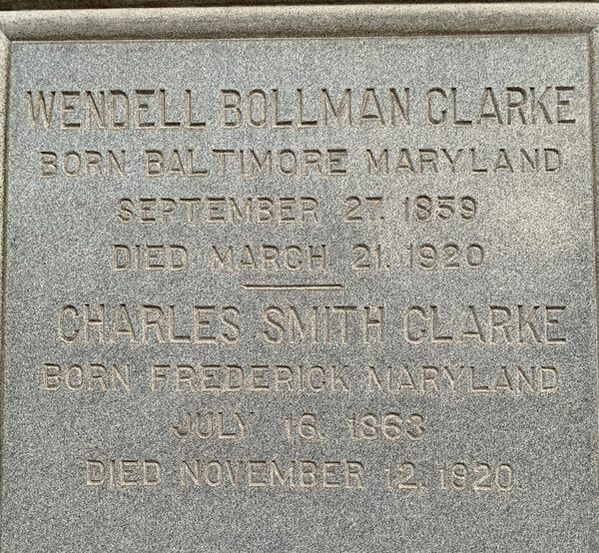

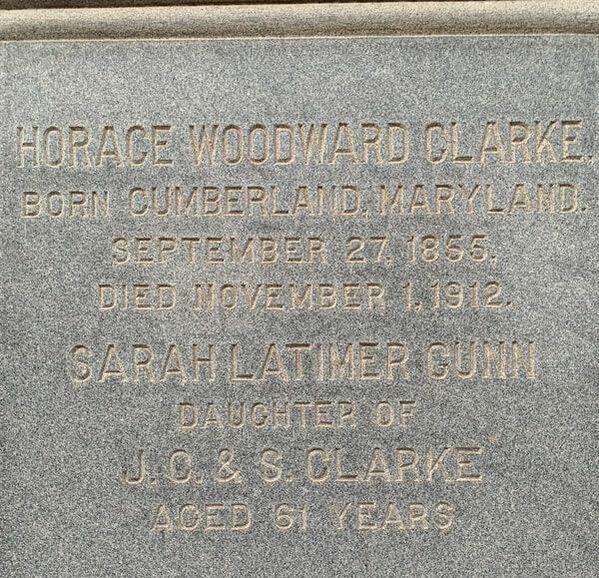

Along the way, James Clarke found time for a family of his own. He married Susannah Shafer (b. 1832) on December 21st, 1852. She was a Frederick native through and through, the daughter of Peter Schaffer and Elizabeth Brunner. Her great-grandfather, Jacob Brunner is connected to building Schifferstadt. A passage found in William Jarboe Grove's 1921 work The History of Carrollton Manor recounts a former love interest of our subject when he was a resident of "Slabtown," a collection simply built slabs (frame and log houses) for the accommodation of B & O Railroad employees. The location was located just north of Buckeystown at a vicinity that would come to take the name of Lime Kiln. Mr. Grove states: "Mr. Clarke at that time was a water boy in the employ of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. A widow living in the best house in town and whose name was Baldwin, had a beautiful daughter by the name of Mary. James C. Clarke fell desperately in love with Miss Baldwin and pressed his suit, but Mary had another lover, James Fulton, also employed by the railroad who was a foreman and like James Clarke was a handsome and fine looking fellow. Miss Baldwin married James Fulton. They raised a large family of children but Mr. Fulton never advanced further than track foreman and finally moved to Iowa. James C. Clarke rose rapidly and became President of one of the leading railroads in the United States. Many other people said Mary made a mistake, but she always seemed happy with her family. " I found the object of James' earlier affection in the 1850 census. Apparently, Mr. Grove had her name mixed up because I found her in the form of Lydia A. Baldwin, daughter of Grace (Buckman) Baldwin and Reginald Baldwin. Lydia married James A. Fulton in May, 1851 and eventually moved to Boone County, Iowa around 1890. She is buried there, dying in 1908, eight years after her husband passed in 1900. As for James and Susannah, five known children would bless the union: Horace Woodward (1855-1912) born in Cumberland, Virginia "Jennie" Osborne (Jeffery) (1857-1933), Wendell Bollman (1859-1920) born in Baltimore, Charles Smith (1863-1920) born in Frederick, Sarah Latimer (Gunn) (1866-1927) born in Baltimore. During the American Civil War, Clarke was kept busy with railroad logistics involving troops. Apparently, in 1862, he left the railroad business to return to Maryland and Frederick County where he became engaged in farming, milling and merchandising. He was part owner in a grocery and wholesale business on the SW corner of Market and Patrick streets (where Colonial Jewelers is located today). The family lived on E. Church Street in the home that would one day become the Evangelical Lutheran Church Parsonage. Clarke was said to have been visited by officers and soldiers of both armies of whom he had friends and acquaintances. I also uncovered a story in which he appeared to be a Southern sympathizer, and even got himself arrested and imprisoned for providing valuable supplies to the Confederates. If that’s not playing both sides of the fence, I don’t know what is? After the war, James C. Clarke took charge of the Ashland Iron Works in Baltimore County, and soon became an owner of interest in this company. He relocated to Baltimore, and in 1866 was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, and a year later, to the State Senate in Annapolis where he would serve two terms. He was appointed a brigadier-general in the Maryland National Guard by Maryland governor Oden Bowie. In 1870, James C. Clarke was nominated president of his first employer—the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. He knew the dominance of the “iron horse,” and would jump back to the railroad industry in 1872 after being made president and general manager of the Erie Railroad, where he worked until 1874. He would then head to Chicago, Illinois. For the next fourteen years, Gen. Clarke would work for one of the most prestigious lines in railroad history—the Illinois Central Railroad. He began as superintendent of the railroad’s North Division, but two years in would take up residence in the south region as he lived on Bourbon Street in New Orleans from 1876-1883. He was elected president of the Illinois Central in 1883, and held this post for nearly five years. These duties brought him back to residency in Chicago. From 1888-1902, Clarke returned south and spent a decade with the Mobile (Alabama) & Ohio Railroad, becoming the firm’s president early on. He took a flailing operation, and made it successful again by the end of his tenure. While living abroad, Mrs. Susanna Clarke died in September, 1892. General Clarke finished an incredible 58-year career in the burgeoning transportation industry of our nation. Over his lifetime, he saw the birth of both the C&O Canal and B&O Railroad. He not only worked for both entities, but helped both grow under his managerial leadership. Mending Fences Gen. Clarke returned to Frederick regularly to visit old friends, plus he owned three farms in the area. The small town always felt like true home, even though his profession took him to reside elsewhere. Clarke always retained an interest in town growth and affairs. Ironically, he is attached to another controversial story involving fencing in downtown Frederick. Beginning in 1818, Court House Square resident, Col. John McPherson began installing iron railings around the Frederick county Courthouse and subsequent public lawn. This was forged at McPherson’s Catoctin Furnace operation located in the north sector of the county between Lewistown and Mechanictown, destined to become Thurmont. Apparently the neighbors of “the Square,” consisting of the town’s “upper crust,” were annoyed with the recent phenomena of rogue animals grazing on the prestigious courthouse lawn that once boasted legal luminaries such as Francis Scott Key, Roger Brooke Taney and Reverdy Johnson. What seemed like a philanthropic venture by McPherson soon angered the general citizenry as they saw this symbolized an obtrusive wall to a public place and access to courthouse amenities and officials. It also seemed as an extension of the adjacent neighbors hoping to keep all others out of their prestigious neighborhood unless they had official court business to attend perform. The squabble would last for decades, as a matter of fact, eighty years. The railings were finally removed in 1888. To help pacify the masses, Gen. Clarke found it necessary to offer an olive branch to all citizens by providing a perfect centerpiece to the courthouse green—an ornamental fountain. The Clarke fountain was duly dedicated to all people of Frederick. Again, I want to point out the irony here as both “railing stories” involve Clarke, especially fitting because he built his career, fortune and reputation on iron rails! Gen. James C. Clarke could be found residing in Mobile, Alabama with his two sons in 1900. Both sons, Wendall and Charley, worked for the railroad. Wendell is listed as a clerk, and Charley as superintendent, taking over his Dad’s position with the Mobile & Ohio Railroad.

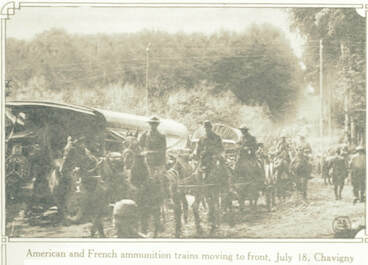

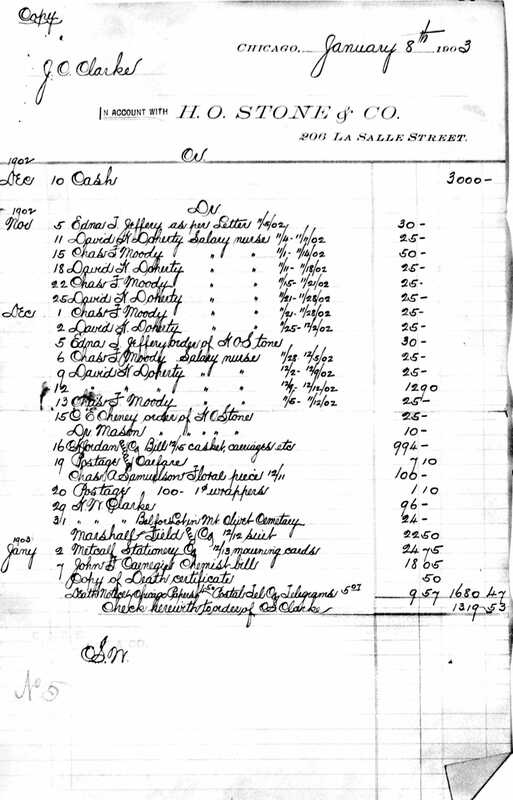

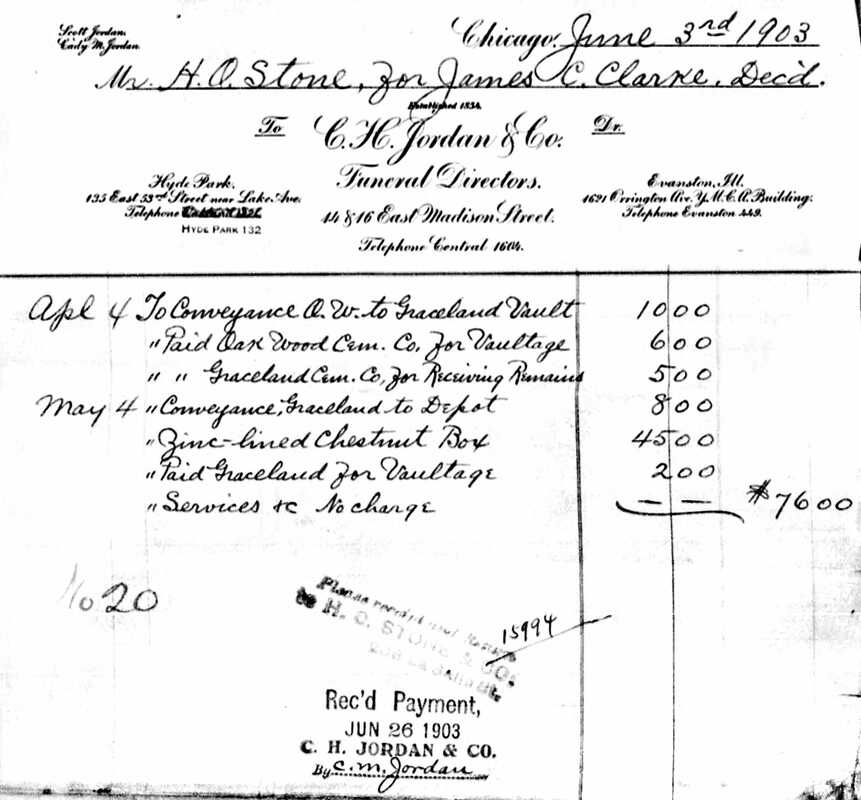

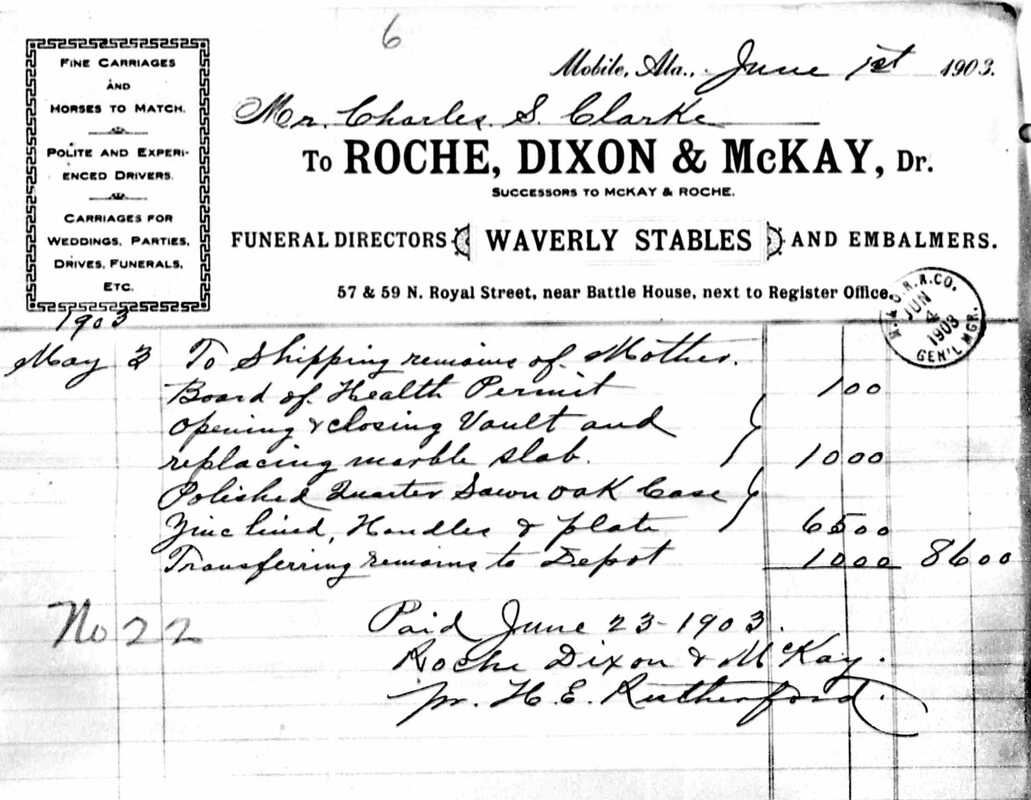

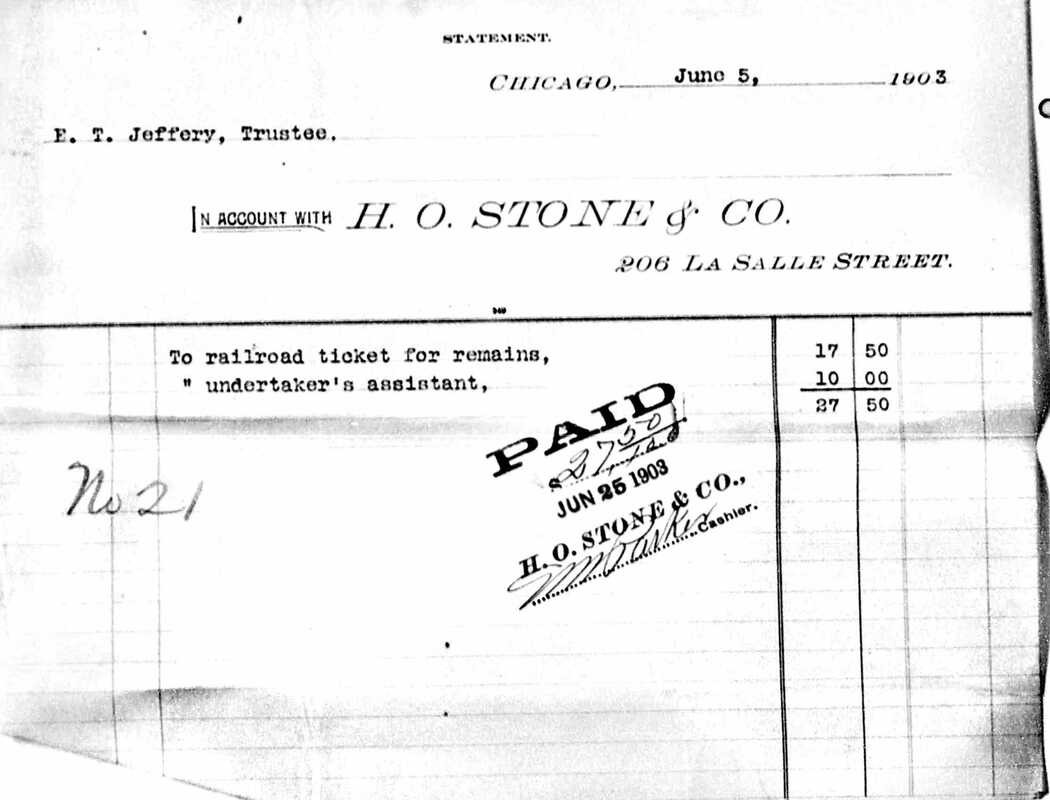

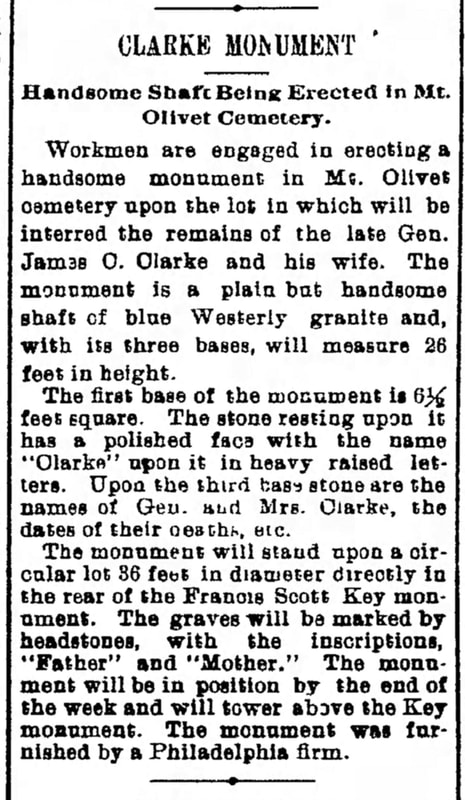

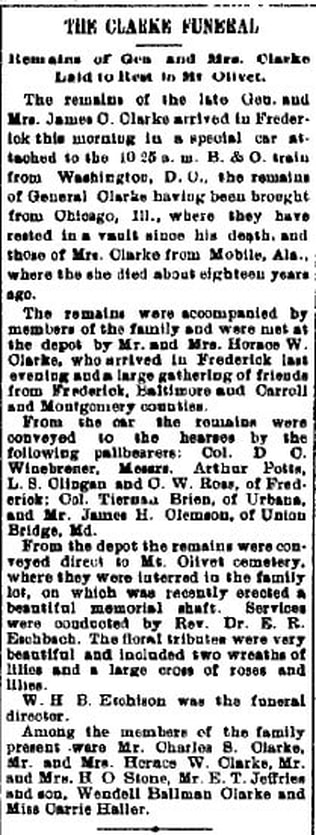

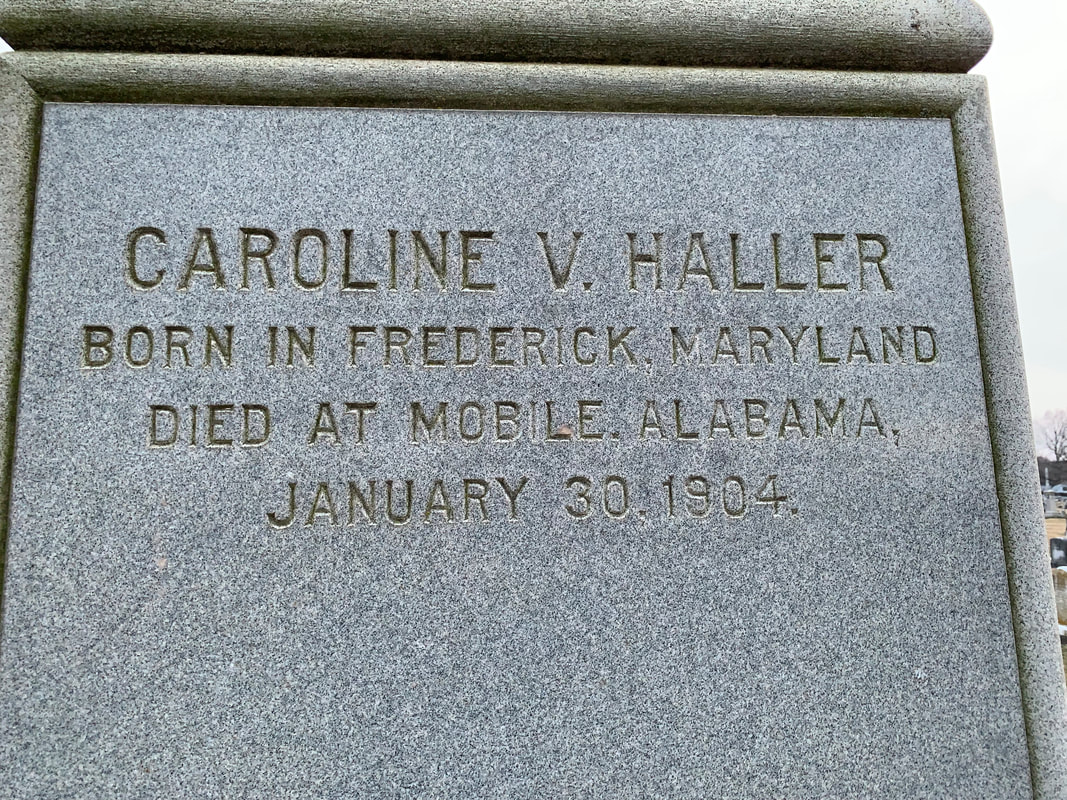

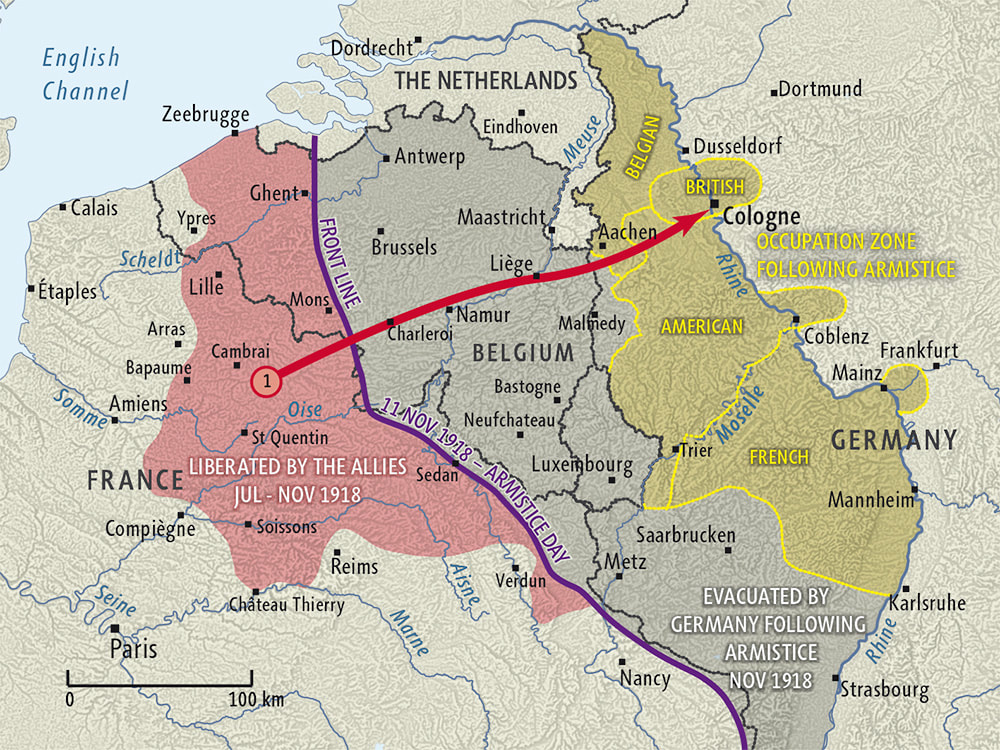

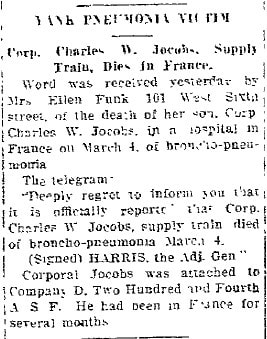

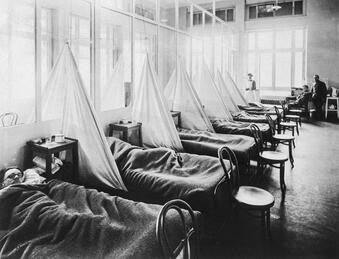

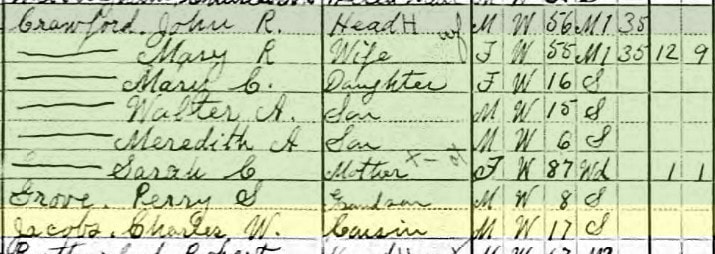

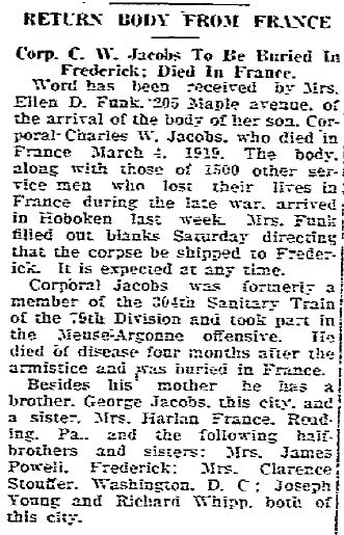

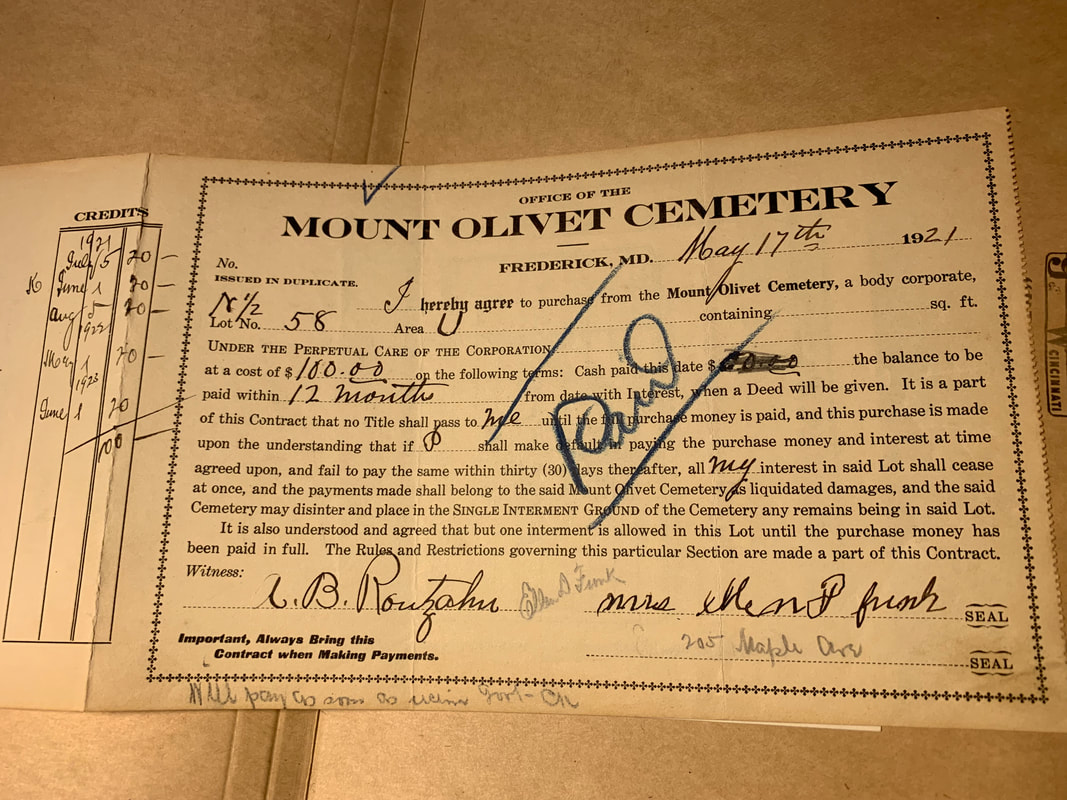

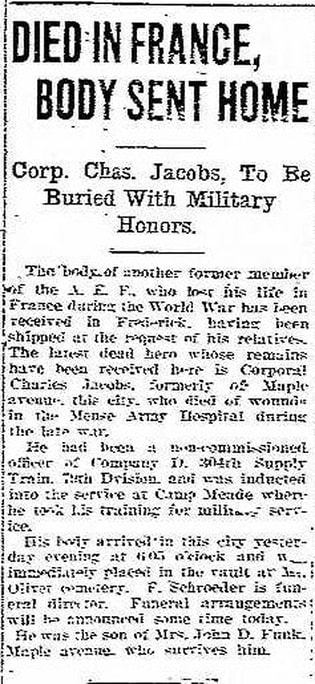

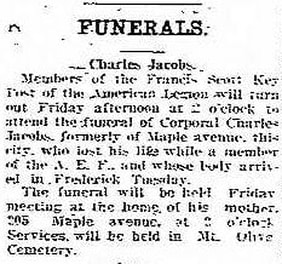

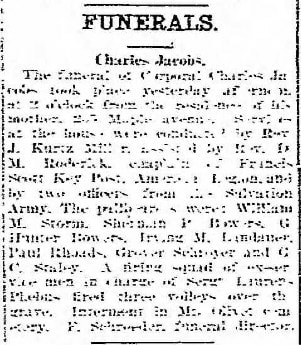

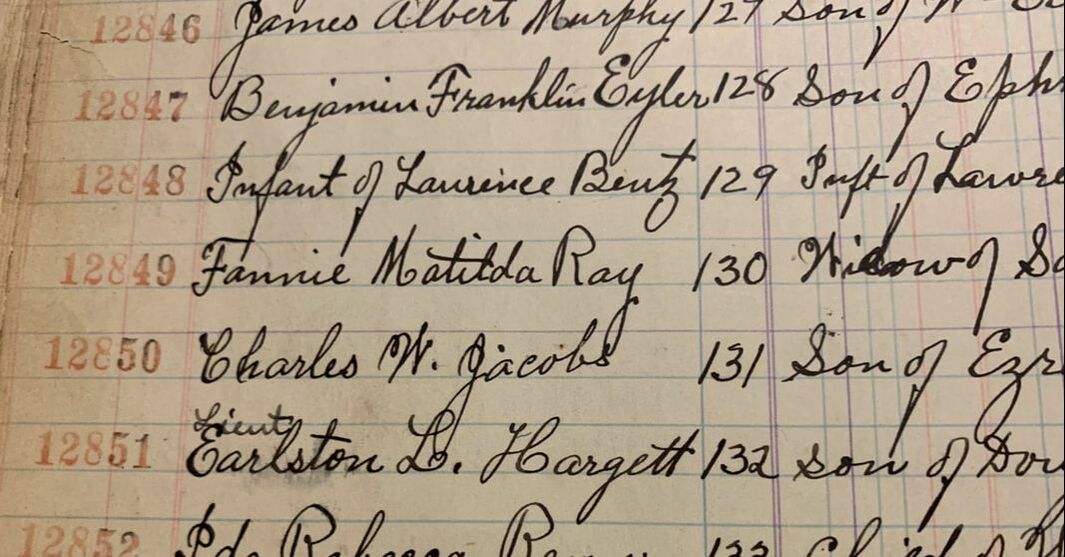

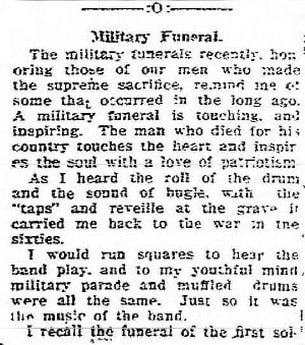

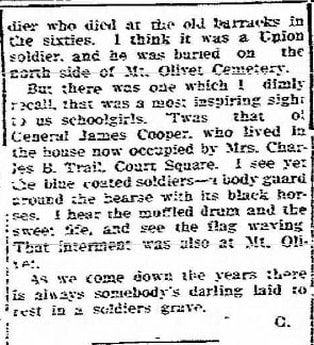

Clarke's body was handled by Chicago's C. H. Jordan & Co. Funeral Directors, and appears to have been taken to Oak Wood Cemetery in Chicago for a funeral service of some kind. Here, Gen. Clarke was placed in a storage vault, as the season would not guarantee favorable weather to bury him in Frederick in the heart of the winter season. This was quite a common occurrence in a time devoid of better equipment to excavate frozen ground. Plans were also made to bring Mrs. Clarke's body to Frederick from Mobile, where she had been buried in Graceland Cemetery. I assume that the weather also played a factor here as well. Construction soon commenced on an elaborate memorial obelisk to adorn the Clarke burial plot in Frederick. Both Gen. and Mrs. Clarke's bodies would be transported by train back to Frederick on the morning of May, 6th, 1903. A procession brought the bodies to Mount Olivet where graveside services were held under the shadow of the magnificent memorial that had been recently finished. I'm not sure whether or not the procession passed through Clarke Place, but I can guarantee that it went by Clarke place en-route to the cemetery.  Graves of Harry and Anna Bowers in Area D/Lot 3 with Grove Stadium in background Graves of Harry and Anna Bowers in Area D/Lot 3 with Grove Stadium in background In time, sons Horace (d. 1912), Wendell (d. 1920), Charles (d. 1920) and daughter Sarah L. Gunn (d. 1927) would join their parents here in Mount Olivet. One additional burial in this lot was that of Caroline Virginia Haller (d. 1904). Ms. Haller can be found living with the family in Mobile in 1900, and is listed simply as a friend. She could have served as a housekeeper or nanny for the children as she lived with the family for decades. Carrie, as she was known, attended the May, 1903 funeral for Gen. Clarke, but would be buried in this same lot the following February after her death back in Mobile in January, 1904 at the age of 64. A final irony here lies in the fact that the vicinity of southern Frederick City was commonly referred to as “Hallerstown,” long before there was ever a Clarke Place. This was said to be due to the influx of family members with that surname. So next time you visit any of the Clarke “places” in town be it the street, Court Square fountain or burial-memorial site here in Mount Olivet, be sure to give homage to a true pioneer of transportation innovation. And I would also suggest that you keep all baseballs "out of site" from crotchety Mrs. Baker as well—she's buried about 20 yards to the left of the Clarke monument on the corner of Area D. So fitting that Harry Grove Stadium at Nymeo Park is such a short distance away. From the vantage point of the month of March, this past November seems so long ago. Was this the same notion of Fredericktonians a century ago when they received word in mid-March (1919) that another one of their native sons had perished as a victim of World War I? The war had ended for all intents and purposes back on November 11th with the famed Armistice that ceased fighting on land, sea and air between the Allies and their adversary, Germany. However, on March 13th, the Frederick Post newspaper’s front page announced that Corporal Charles Winfield Jacobs of Frederick had succumbed to pneumonia while serving overseas with Company D of the 304th Supply Train. Just four months earlier, victory over Germany had been celebrated in the streets of Frederick, and everywhere else in the country. In the weeks and months that followed, many soldiers began making their way back home—a 16-day trip by boat. The Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year holidays of 1918 were especially joyous occasions for all families, especially those missing a serviceman (or woman) at the supper table. The general thought was that these veterans were now out of harm’s way, safe and sound, and anticipated back to Frederick soon. The Armistice Although the armistice, itself, ended the fighting on the Western battlefront of Europe, total peace would be prolonged three times until the Treaty of Versailles. This was signed on June 28th, 1919, but would not officially take effect until January 10th, 1920. In the ceasefire agreement from November, the question over the settlement of the Rhineland was set aside. This was the highly contested border area between Germany and France, comprised of the Rhine and Ruhr river areas. The Armistice merely provided for the Allied occupation of the left bank of the Rhine and three "bridgeheads" near Cologne, Mainz, and Coblenz. The German troops were forced to withdraw behind a ten kilometer wide neutral zone along the right bank of the Rhine.  US soldiers entering Germany after the signing of the Armistice of November 11, 1918 US soldiers entering Germany after the signing of the Armistice of November 11, 1918 During the negotiation of the Treaty of Versailles, France had to forgo any additional “land-grab” ideas it entertained in the Rhineland, and finally accept a compromise. To meet France’s need for security, the United States and Great Britain promised military support in the event of a reprisal German attack. In return, the military occupation of the Rhineland was limited to only last fifteen years. Four occupation zones were established, each possessing a future deadline in which to be vacated according to plan. The smallest zones were left to the British and the Americans, with the US surrendering its area to the French in 1923. The treaty outlined that a failure on the part of the German government to uphold its contractual obligations would result in an extension of the occupation. So, to review, the goal of the occupation was to achieve military protection against Germany on one hand, and, to secure collateral for the German reparations on the other. Charles Winfield Jacobs and his “band of brothers” were part of this Allied occupation force. Details about the young man are scant, but he represents the last of our county’s service-related casualties tied to “the Great War.” Of the 2,095 known veterans who came from Frederick County, there were 83 who perished. Corporal Jacobs is among a smaller subset of 12 servicemen interred here at Mount Olivet. (NOTE: The notice that appeared in the Frederick Post (above) is hard to make out from archival microfilm, but I have added a transcript.) Yank Pneumonia Victim Corp. Charles W. Jacobs, Supply train, Dies in France. Word was received yesterday by Mrs. Ellen Funk, 101 W. Sixth street, of the death of her son, Corp. Charles W. Jacobs, in a hospital in France on March 4th, of bronchio-pneumonia. The telegram: “Deeply regret to inform you that it is officially reported that Corp. Charles W. Jacobs supply train died of bronchio-pneumonia March 4. (Signed) HARRIS, the Adj. Gen“ Corporal Jacobs was attached to Company D, Two Hundred and Fourth for several months The next day, the newspaper ran a list of Jacob’s surviving family members including his mother, three sisters, and three brothers. He was unmarried at his time of death, and working as an auto mechanic within the US Army’s 304th Supply Train, Company D, part of the 79th Division. (NOTE: the paper erred with his unit). Charles Winfield Jacobs Charles Winfield Jacobs was born in Frederick on December 11th, 1890. He was the son of Ellen D. (Crummitt) and Ezra Jacobs. From what I gleaned, childhood was likely “tough sledding” for Charles as presumed after finding a brief article in the Frederick News (dated Dec. 28, 1893). Charles’ father died a few weeks later and was buried in Doubs Cemetery near Adamstown. His mom, Mrs. Ellen Jacobs, would marry again—John D. Funk. By the time of the war, the family, or at least Charles, had put on his draft registration that he was residing at 101 W. 6th Street in the northern sector of Frederick City. He also listed his profession at the time as that of chauffeur. In May, 1918, Charles was inducted into the US Army as a private. The 27 year-old was originally assigned to 12th Company, 3rd Battalion of the 154th Depot Brigade. He received his basic training at nearby Camp Meade, and eventually transferred to Company D of the 304th Supply Train.  Private Jacobs departed for Europe from Hoboken, New Jersey on July 14th, 1918 aboard a troop transport ship. At least one other Frederick County resident was in Jacob’s Company D. This was Robert E. Valentine of Rocky Ridge. Both men would land at Haverford, England, and eventually made their way to the war-front in France by early fall. Along the way, Charles W. Jacobs would be promoted to the rank of corporal on September 26th, 1918. Jacobs, and his fellow soldiers of Company D, found themselves in the heart of fighting as they were recorded in the Avocourt Sector, Meuse-Argonne, and the Troyon Sector. Meuse, France is listed as his place of his death. It's not known how long he suffered from pneumonia, but the US military was no stranger to this malady, as the previous fall saw countless soldiers attacked by a foe far deadlier than the German soldiers. This was the Spanish Flu pandemic. Jacobs is reported to have died in a military hospital and buried in a nearby American cemetery. On July 4th, 1919, Corporal Jacob’s sacrifice was remembered publicly as one of the immortal 83 who would not return to Frederick among the living. The occasion was a special Homecoming celebration for Frederick County vets. Nearly 15,000 citizens are said to have taken part in the festivities of the day. Best of all, many of our local doughboys and sailors paraded through the streets of town, amidst cheers and thanks from the masses on hand.  Burial of a fallen American serviceman in France during WWI Burial of a fallen American serviceman in France during WWI The Long and Winding Road French leaders were against the removal of veteran bodies back to the United States. They envisioned macabre trains packed with bodies crisscrossing their countryside. Arguing that they had to concentrate on rebuilding their country, France banned removal of bodies for three years. Nearly a year after the armistice, a compromise was forged. The War Department announced in October 1919 that it would survey each of the fallen soldiers’ next of kin. Families could choose to bring home remains or have them buried in newly created American military cemeteries in Europe. Ballots were sent to nearly 80,000 grieving relatives, asking them for guidance. In late 1920, the French finally yielded to American pressure and lifted their ban on the return of bodies. The United States spent the next two years and more than $30 million recovering the dead. The remains of 46,000 soldiers were returned to the States at their families’ request, while another 30,000—roughly 40 percent of the total—were laid to rest in military cemeteries in Europe. One of these was the body of Corporal Jacobs. The federal government granted the request of Charles’ mom to have her son’s remains brought back home. Our files contain the original signed contract by Mrs. Funk in which she purchased a plot in Area U for the purpose of burying her son. This transaction occurred on May 17th, 1921. A newspaper article appeared on June 22nd, announcing the fact that Jacobs’ body had arrived back home in Frederick and that military honors would be performed later in the week at Mount Olivet. The funeral occurred on June 24th. (transcript for clipping above left) Died in France, Body Sent Home Corp. Chas. Jacobs, To Be Buried With Military Honors The body of another former member of the A.E.F. who lost his life in France during the World war has been received in Frederick, having been shipped at the request of his relatives. The latest dead hero whose remains have been received here is Corporal Charles Jacobs, formerly of Maple avenue, this city, who died of wounds in the Meuse Army Hospital during the late war. He had been a non-commissioned officer of Company D, 304th Supply train, 79th division, and was inducted into the service at Camp Meade where he took his training for military service. His body arrived in this city yesterday evening at 6:05 o'clock and was immediately placed in the vault at Mt. Olivet cemetery. F. Schroeder is funeral director. Funeral arrangements will be announced some time today. He was the son of Mrs. John D. Funk, Maple avenue who survives him. (transcript for clipping above lower right) Funerals - Charles Jacobs The funeral of Corporal Charles Jacobs took place yesterday afternoon at 2 o'clock from the residence of his mother, 205 Maple avenue. Services at the house were conducted by Rev. J. Kurtz Miller, assisted by Rev. D. Roderick, chaplain of Francis Scott Key Post, American Legion, and by two officers from the Salvation Army. The pallbearers were William M. Storm, Sherman P. Bowers, G. Hunter Bowers, Irving M. Landauer, Paul Rhoads, Grover Schroyer and C. P. Staley. A firing squad of ex-servicemen in charge of Sergt. Laurence Phebus fired three volleys over the grave. Interment in Mt. Olivet cemetery. F. Schroeder, funeral director. Five days prior, private Benjamin Franklin Eyler had been buried here in the cemetery. Two days after Charles Jacob Winfield's funeral service, another local soldier’s body was also laid to rest in Mount Olivet. This was that of Lt. Earlston Lilburn Hargett, who had been killed in the Battle of Argonne in late September, 1918. All three young men had been buried overseas, and their remains would make the lonely trek back home to Frederick, Maryland. The recent flurry of military pomp and circumstance, attached to these two Frederick heroes, conjured up memories for a contributor to the Frederick News of a much earlier era.I'm assuming it was none other than Emma Gittinger (1850-1927), pioneering female columnist for the newspaper. Charles Winfield Jacobs is buried in Area U/Lot 58. He is one of over 505 known veterans of World War I interred in our cemetery. Last year, at this time, a memorial page was created for Corporal Jacobs as part of our www.MountOlivetVets.com website. On Memorial Day, Frederick American Legion baseball players marked his grave with a small flaglet. This again occurred on November 11th, 2018 (Veterans Day)— the 100th anniversary of the Armistice. We featured special programming that weekend including lectures and walking tours of WWI soldiers’ graves. Again, I acknowledged Charles Winfield Jacobs. In December, we honored Jacob’s memory by placing a wreath atop his grave, part of our inaugural experience in the Wreaths Across America program that originated at Arlington Cemetery. Now on the 100th anniversary of his death, I am humbled to write this brief piece as part of our ongoing “Stories in Stone” blog series. The finishing touch was yet another visit to the corporal's gravesite of just under 98 years in an effort to take a photograph of his tombstone. The memorial, along with a wreath, were resting peacefully under a blanket of fresh snow. Rest in Peace, Corporal Jacobs. Thanks for your service, and making the ultimate sacrifice. In doing so, you helped guarantee the continued freedoms of future generations living in the greatest country in the world. The very same can be said for 4,000 other veterans, men and women, buried throughout Mount Olivet. For those interested, the following links below correspond to the 12 casualties of World War I that are buried here in Mount Olivet. Click the respective button to go to their respective memorial pages on the previously mentioned MountOlivetVets website.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed