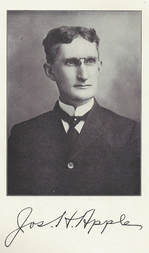

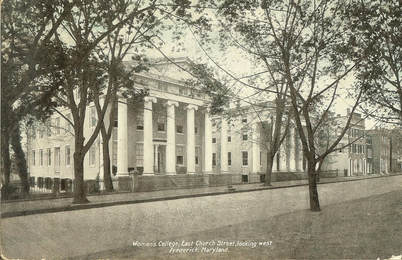

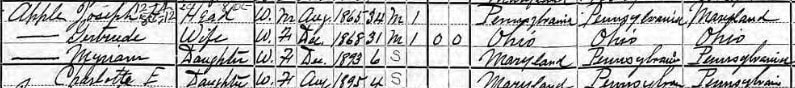

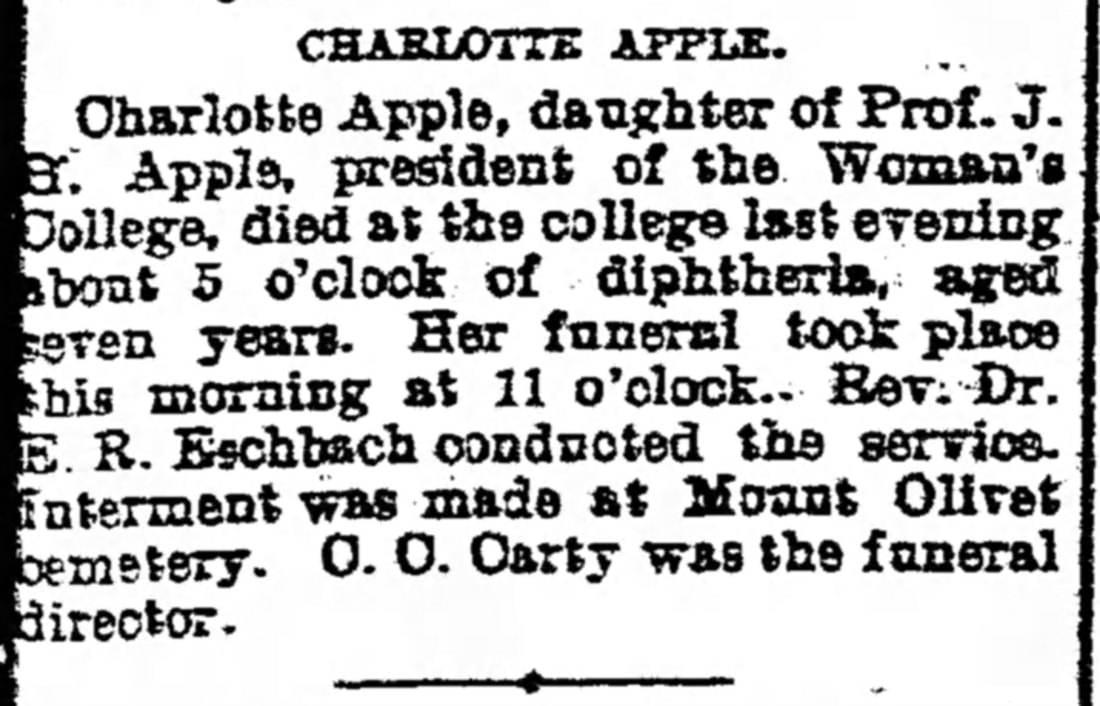

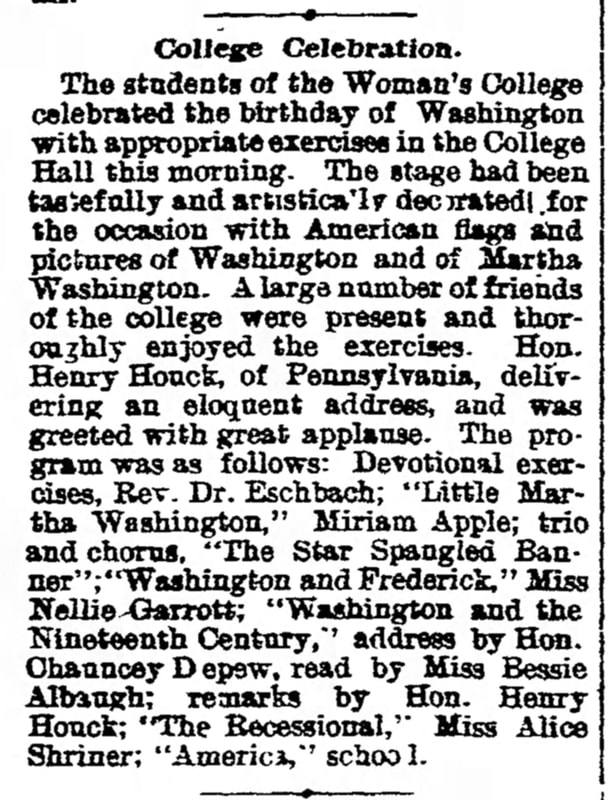

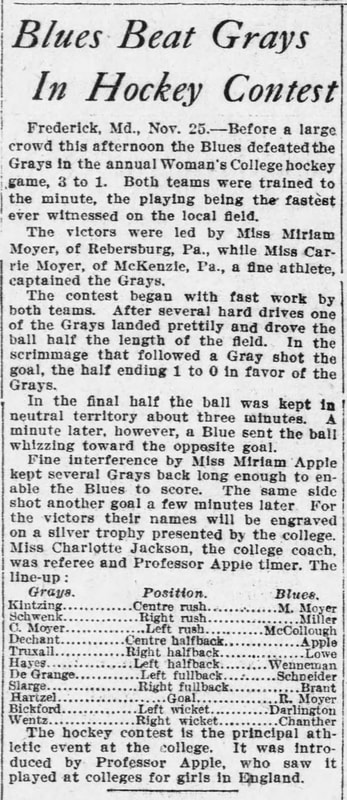

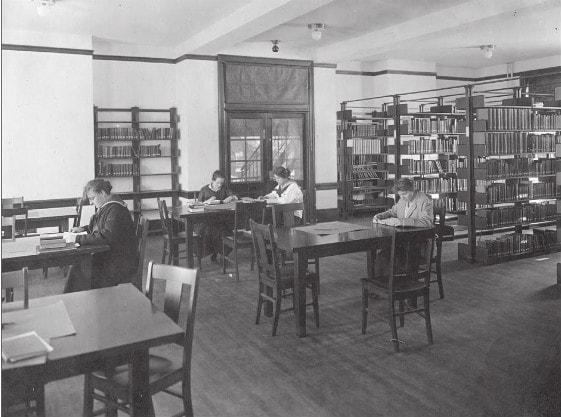

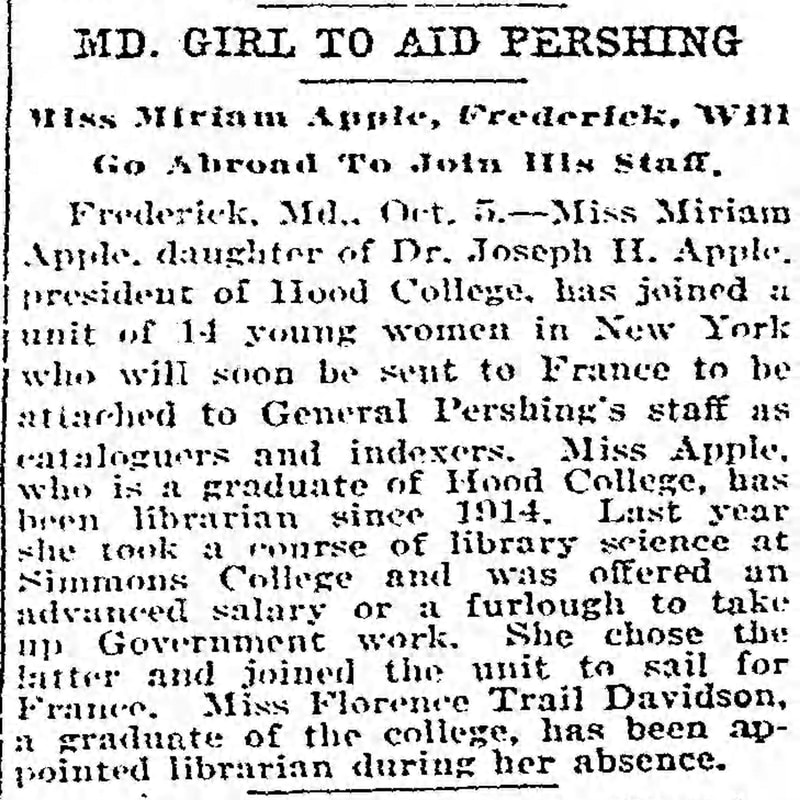

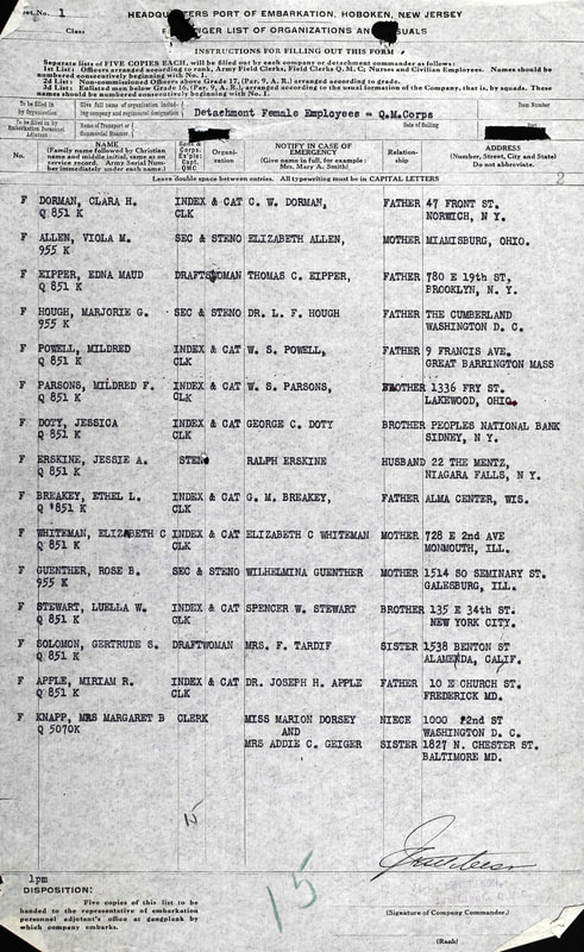

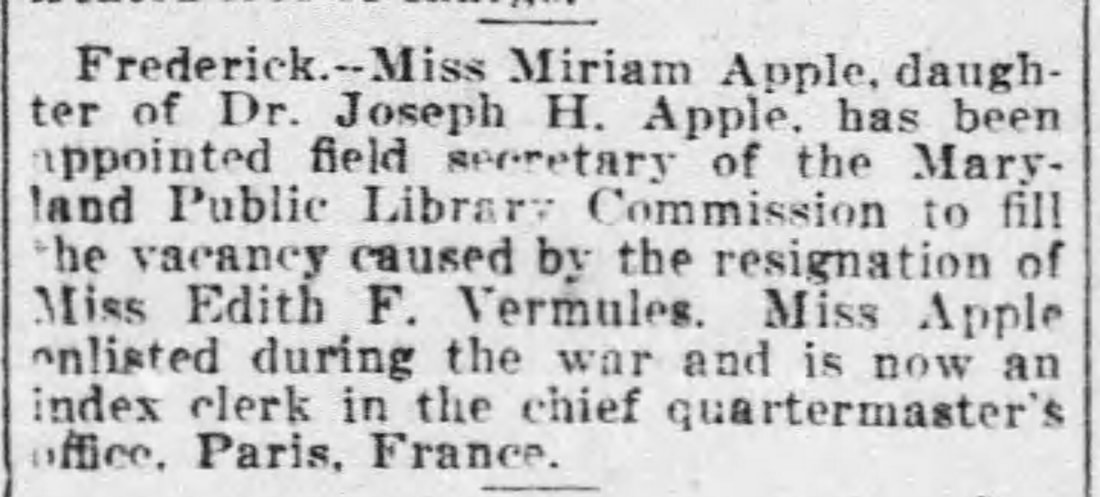

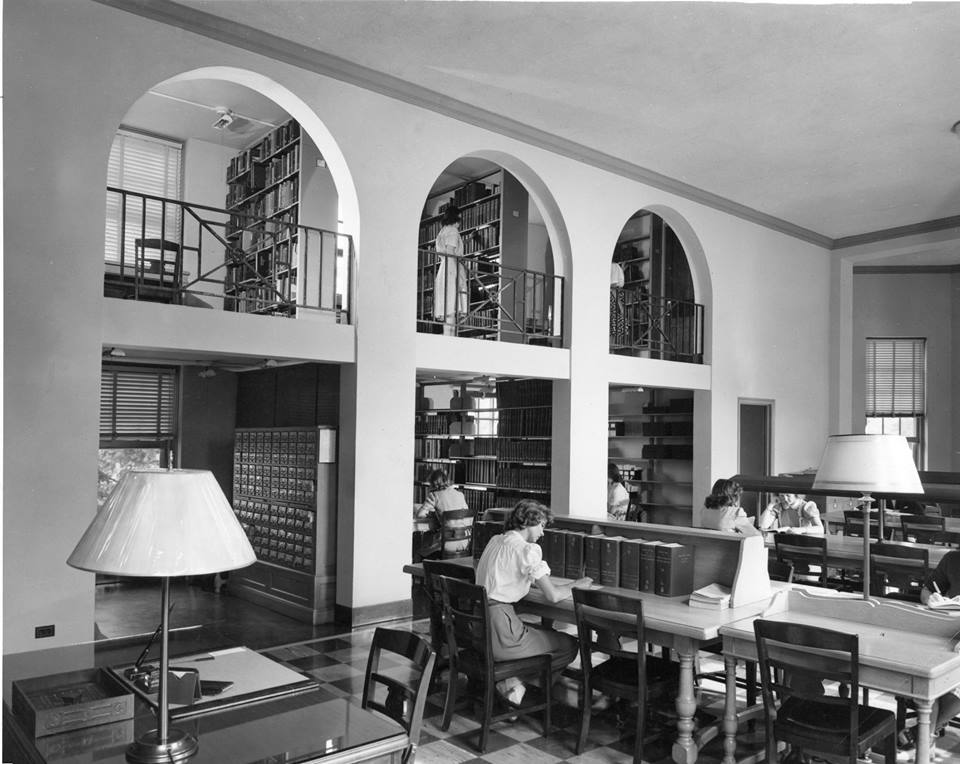

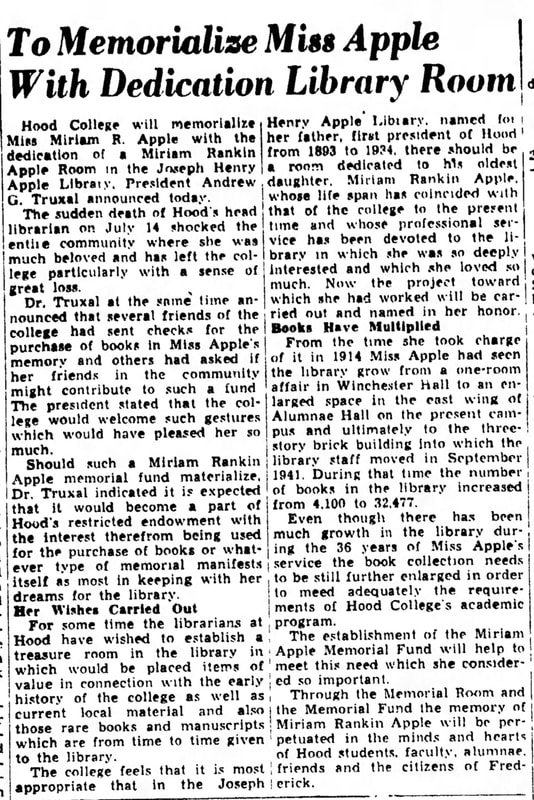

Apples have been with us all our lives, and have always held a scholarly and "bookish" air about them. As a matter of fact, many of us learned about an affiliation with apples in the most famous "books" of all, one that goes back to ancient times—I’ll have you recall a guy named Adam and a gal named Eve. The unnamed fruit of Eden eventually became thought of as an apple. Perhaps this was influenced by the story from Greek mythology of the golden apples in the Garden of Hesperides. Whatever the case, the apple became a symbol for knowledge, immortality, temptation, and the fall of man and sin. Rather than the latter associations mentioned here, I’d like to dwell on the positive connotations of apples, like the objects adorning the desks of beloved teachers, or an orchard-derived “Kryptonite” to thwart having to see doctors. While we are at it, we can also call attention to the modern-day technology company that has been revolutionizing the computing world for over four decades now. Oh, and who can forget apple dumplings, a country culinary delight for all ages.  Here in Frederick, the surname of Apple has certainly upheld the connection to knowledge and learning. Dr. Joseph Henry Apple, Jr. (1865-1948) came to Frederick from his native Pennsylvania and became the first president of the Woman’s College of Frederick. His outstanding leadership talents grew the school in countless ways. It eventually became known as Hood College, and moved its campus from Winchester Hall in downtown Frederick to its present site on Rosemont Avenue. Dr. Apple arrived here in town in the summer of 1893, with his wife, Mary Evans (Rankin) Apple. The couple had wed just months before in December of 1892, and it has been said that it was Mary who influenced her husband to make the move to Frederick. Mary grew up in Clarion, PA in the western part of the state and enjoyed the distinction of being the first Clarion pupil to graduate from the Pennsylvania State Normal School, in the class of 1889. Soon afterward Mary’s ambition to become a teacher led her to continue her studies at the Cook County Normal, Chicago, IL., from which she graduated in 1890. For one year after graduation she taught for a public school in suburban Chicago with marked success Mary then came home to become a faculty member of the Clarion State Normal School. As Dr. Apple held the title of President and Principal, Mary would serve as Vice President and taught classes. Their first school year commenced that fall of 1893. By the time of the Christmas holidays to celebrate, Mary was pregnant with the couple’s first child. The baby would arrive less than a week before Christmas on December 19th, 1893. She would be named Miriam Rankin Apple.  Miriam was given a sister named Charlotte in August of 1895. The girls would spend their childhoods within the confines of Winchester Hall, home of the Frederick Woman's College. Unfortunately, Miriam’s mother was not blessed with perfect health throughout her young life. Shortly after Charlotte’s birth, or possibly as a result, evidence of tubercular trouble starting showing itself in autumn of 1895. She was forced to abandon her duties with the Woman’s College at the advice of her physician who recommended a change of climate. Accompanied by her sister, Mrs. Apple spent the winter of 1896 in North Carolina and returned north in the spring to spend the remainder of her days with her parents and friends in Clarion and at her home in Frederick. Thanksgiving of 1896 was celebrated at the college in Frederick. At this time, Miriam’s mother was enduring intense suffering. Mary Apple would succumb to her illness just ten days before Miriam’s third birthday on December 2nd, 1896. Her obituary states: “The hope that some instrumentality would be blessed to her recovery, for the sake of her two little daughters, Miriam and Charlotte, remained strong in her till within ten days of her death.” The article also sheds light on the impression she left on the Woman’s College of Frederick over such a short time: "At this institution of learning, Mrs. Apple at once made herself a necessary part. Her loving advice to and sympathy for the young ladies of the College made her loved by all, and no doubt her influence for good will be felt during the lives of many. She was ever a loving devoted wife to her husband encouraging and helping him in all his undertakings and rejoicing in his success."  Gravesite of Mary R. Apple in Clarion Cemetery (PA) Gravesite of Mary R. Apple in Clarion Cemetery (PA) Mrs. Apple’s body would not be laid to rest here in Mount Olivet, rather it was returned to her family plot in Clarion, Pennsylvania, placed in proximity to her parents and a host of relatives and friends. Miriam, her sister, and Dr. Apple had been dealt a hard blow. The girls leaned on their father, who likely worked through his grief by his extraordinary commitment to growing the college. He would marry again by the end of the century, giving Miriam and Charlotte a step-mother in the person of Gertrude Harner, an instructor at the college hailing from Ohio. While the new union would bring three step-siblings over the first decade o the 1900s, Miriam would be dealt another major loss with the death of Charlotte in December, 1902 shortly after the sixth anniversary of her mother’s passing and days before Miriam’s ninth birthday. Dr. Apple’s surviving daughter would take her studies seriously, as would be expected from the child of educators. She also inherited her mother’s talent as a musician. Several early newspaper articles make mention of Miss Miriam Apple entertaining audiences and guests to the college through her gift as an instrumentalist and also as a singer. She would attend the college herself, and graduated in 1914. She was also an athlete, participating in the College's annual inter-squad field hockey game. The Hood College website notes Miriam’s attributes of grace, charm and friendliness inherent at a young age. Miriam was active in church, civic and club life as well as in the affairs of the college, not surprising due to the fact that her father would serve here as president for 41 years. Upon graduation, she became librarian of the newly named Hood College, carrying on her father’s great interest in library work. A library had been formed on the third floor of Alumnae Hall, a structure that would grace the new campus after its construction in 1914. In an effort to enhance her knowledge of library work, Miriam would take courses at Simmons College in Boston in 1917-1918 school year. This was the equivalent of graduate studies and Miriam excelled in the program taken abroad.

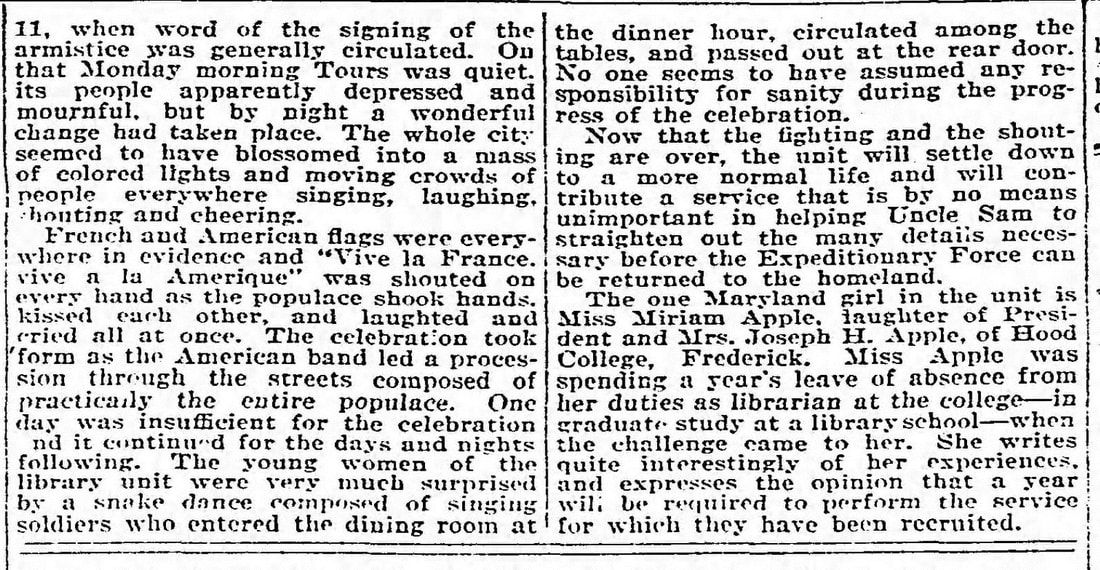

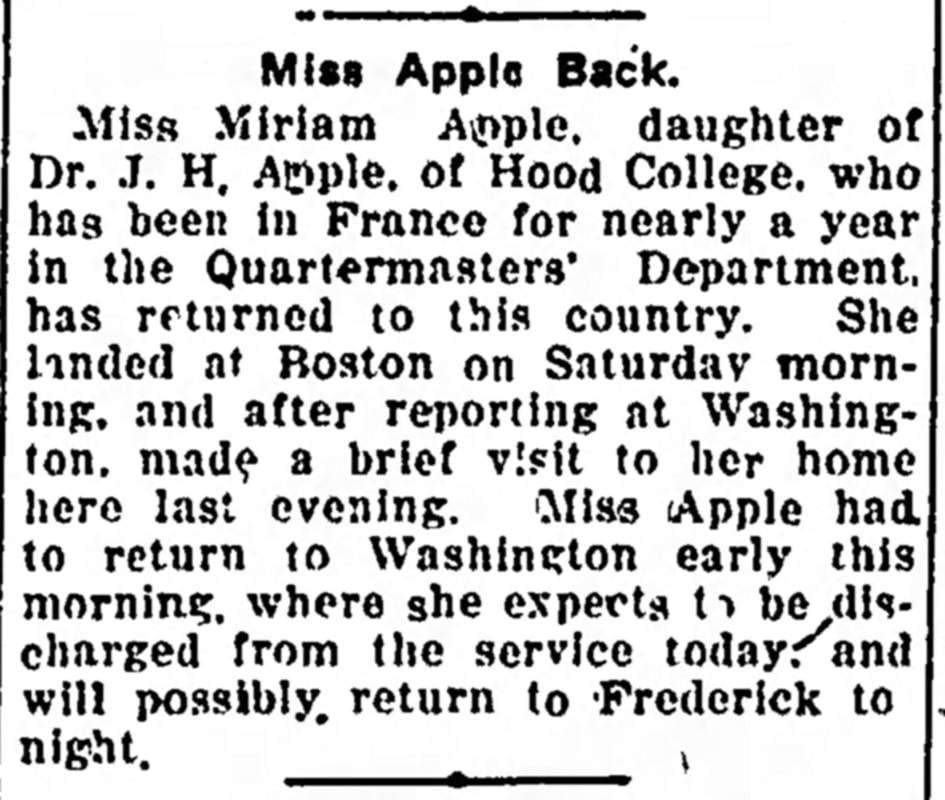

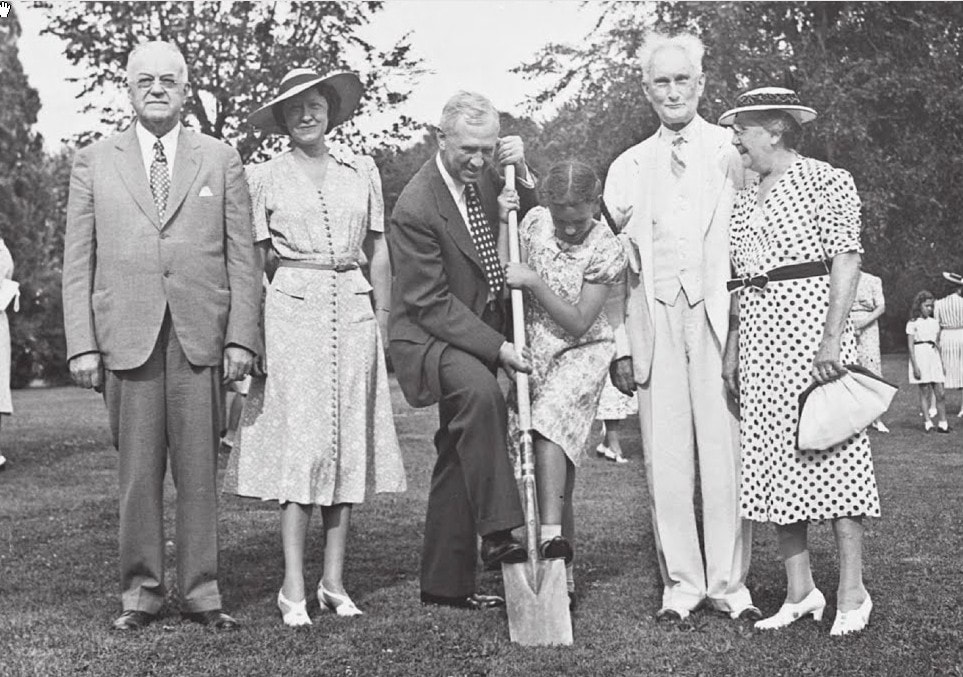

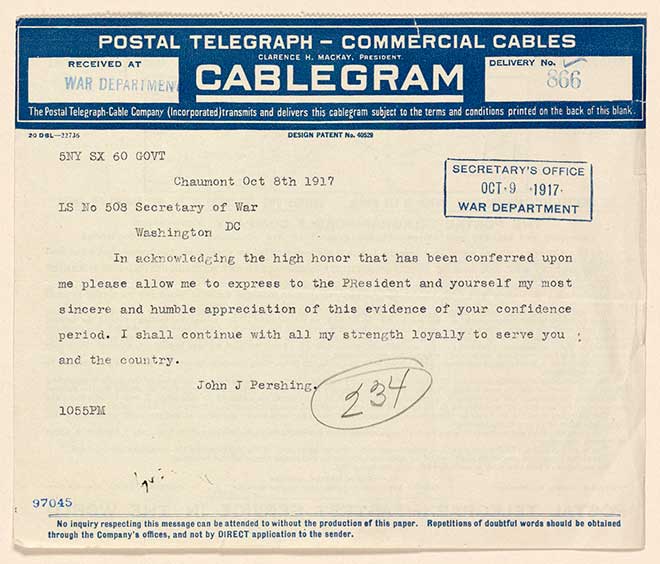

Miriam and her counterparts returned to the United States in July, 1919. The experience further grew Miriam, now 25 years-old. Notoriety of her experiences, combined with extreme competency and above-average drive opened other doors upon her return to Frederick. With the exception of her two leaves of absence to gain graduate training at Simmons and serve in the US Army’s Quartermaster Corps at Gen. Pershing’s headquarters, Miriam R. Apple would hold the position as Hood’s librarian for nearly 36 years. All the while, she continued to gain recognition throughout the east for her efforts on behalf of libraries and their staff workers. A new library was opened in 1941, named in honor of her father who had retired in 1934. Miriam continued serving the college and greater community through the 1940’s. She again answered the call of patriotism with service in the Civilian Defense Corps where she was a fire warden, and within the American Women’s Volunteer Services which provided support services to help the nation during the war such as message delivery, ambulance driving, selling war bonds, emergency kitchens, cycle corps drivers, dog-sled teamsters, aircraft spotters, navigation, aerial photography, fighting fires, truck driving, and canteen workers. Dr. Apple died in January, 1948 and was buried in Mount Olivet. Miriam continued to serve her students, fellow faculty and college administration (along with community and country) until her untimely death at the age of 57. She died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage in the early morning hours of July 15th, 1950. Miriam Rankin Apple's wonderful achievements would be lauded throughout impressive funeral ceremonies at her beloved Evangelical Lutheran Church, and Mount Olivet Cemetery. She was laid to rest in the Apple family plot on Area CC (Lot 27), next to her sister Charlotte who predeceased her nearly half a century earlier and a few yards from her dutiful father. Today on the Hood campus, one can find lasting reminders of the Apple family and their enduring legacy. The Joseph Henry Apple library gave way to the Beneficial-Hodson Library and Information Technology Center. in 1991. Here in the main lobby of the facility, a beautiful color portrait of the school's legendary librarian adorns the wall. Miriam R. Apple's legacy of sharing resources and knowledge with others will continue on through this storied institution. what a father-daughter duo--giving proof that the apple certainly didn't fall far from the tree. Extra special thanks goes out to Hood College Collection Services Development Manager and Archivist Mary Atwell who provided the author with so many fascinating images from the college's vast archival collection.

2 Comments

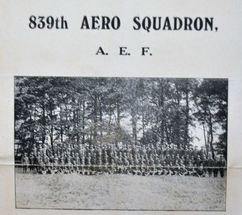

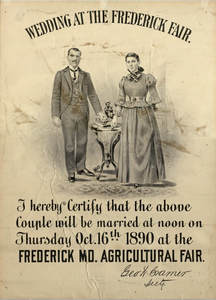

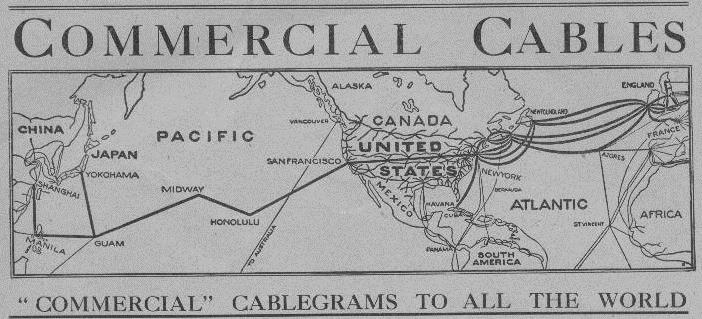

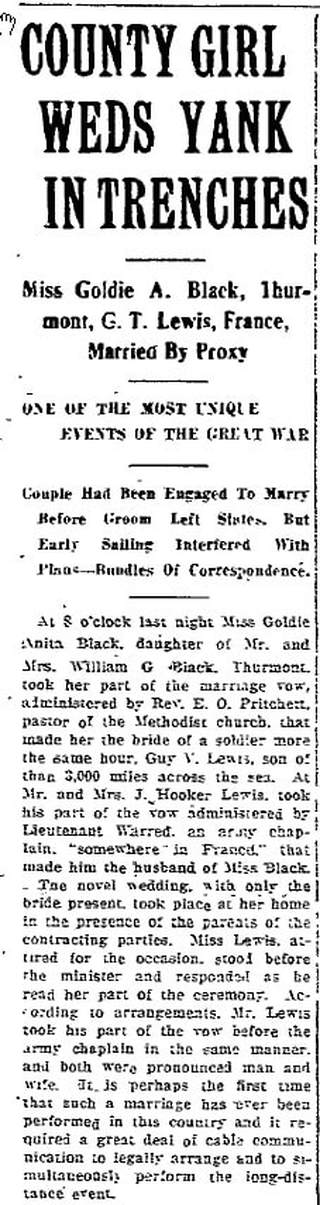

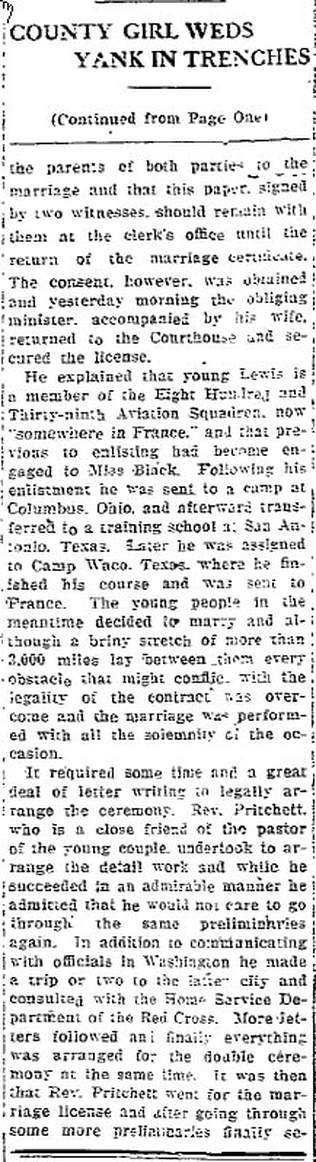

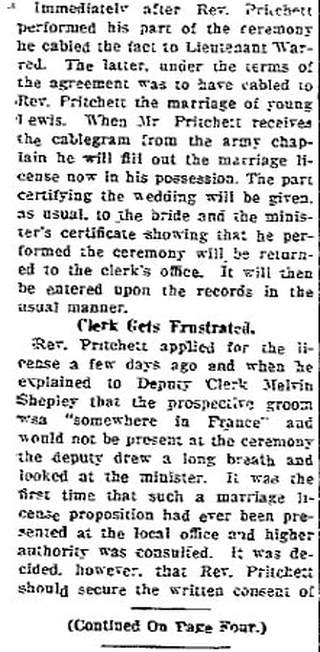

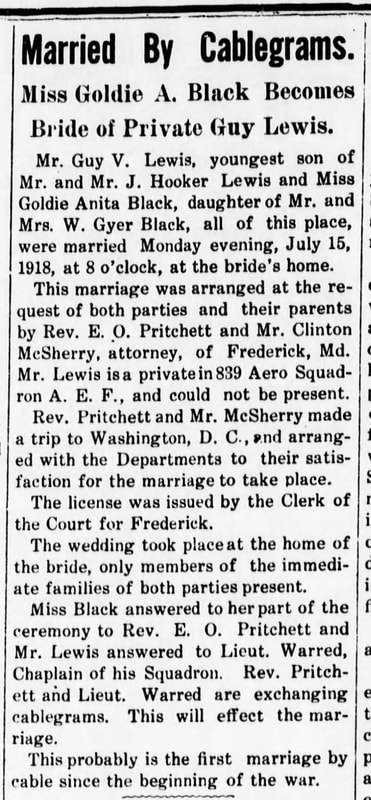

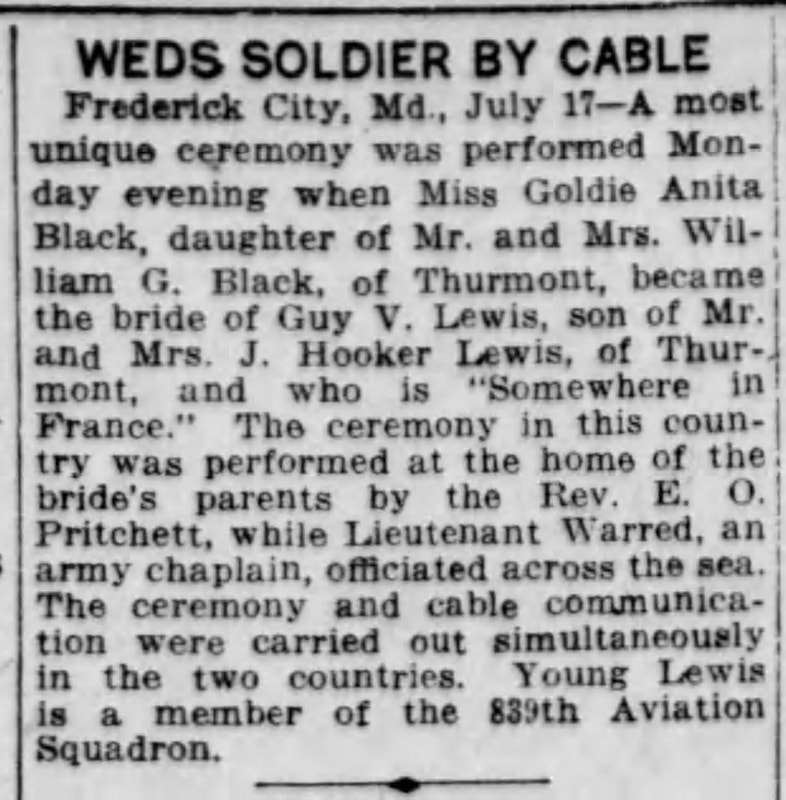

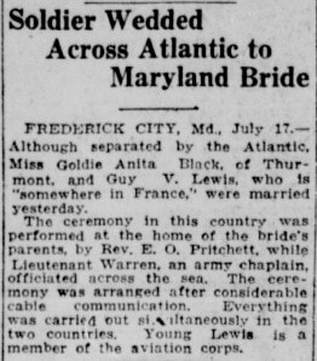

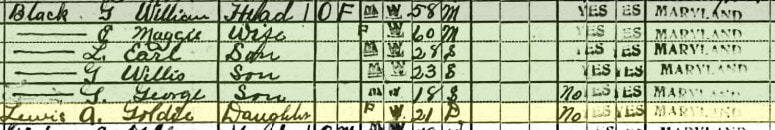

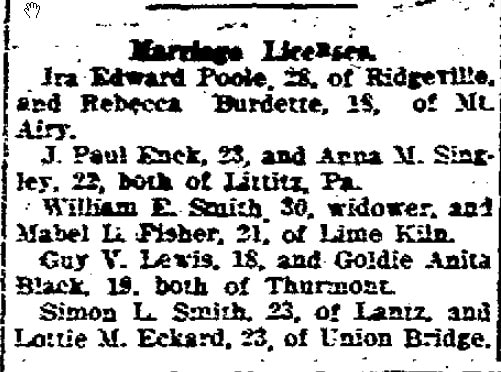

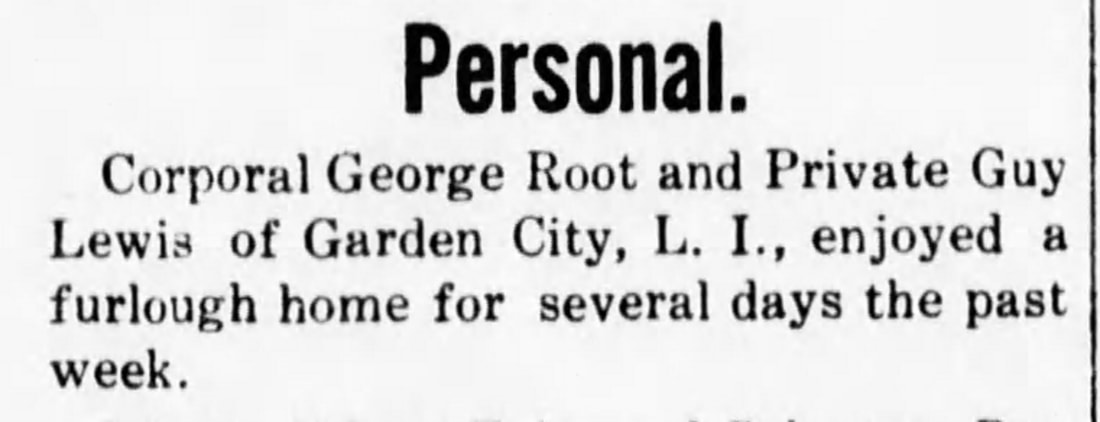

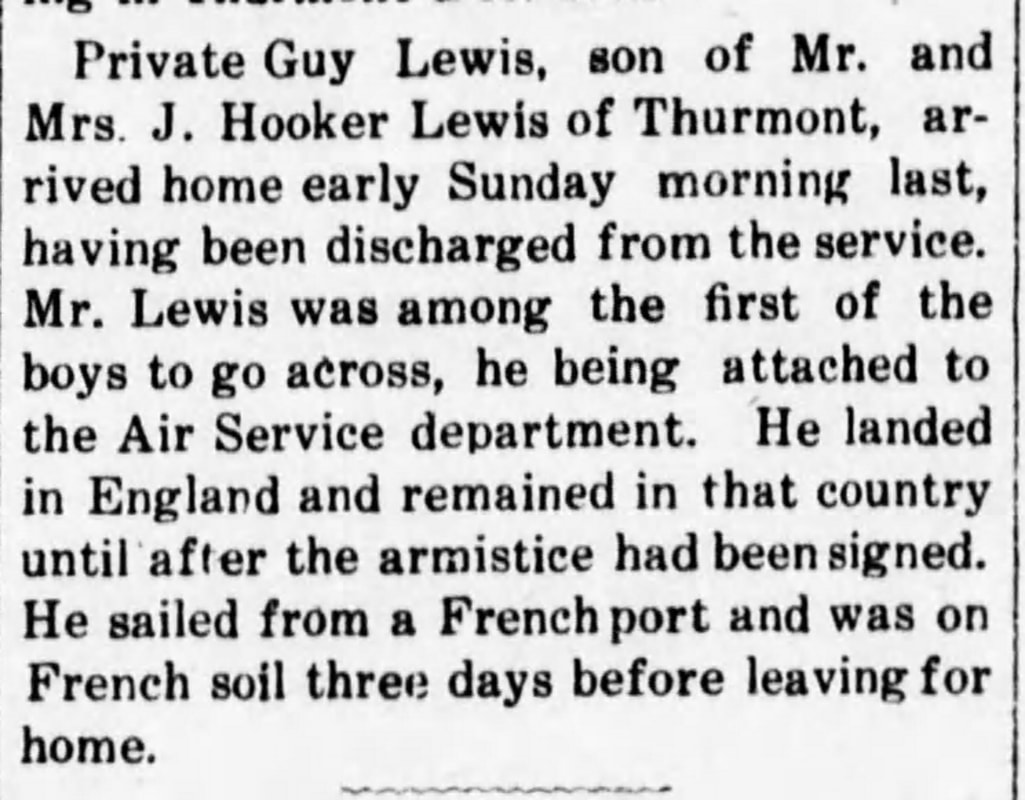

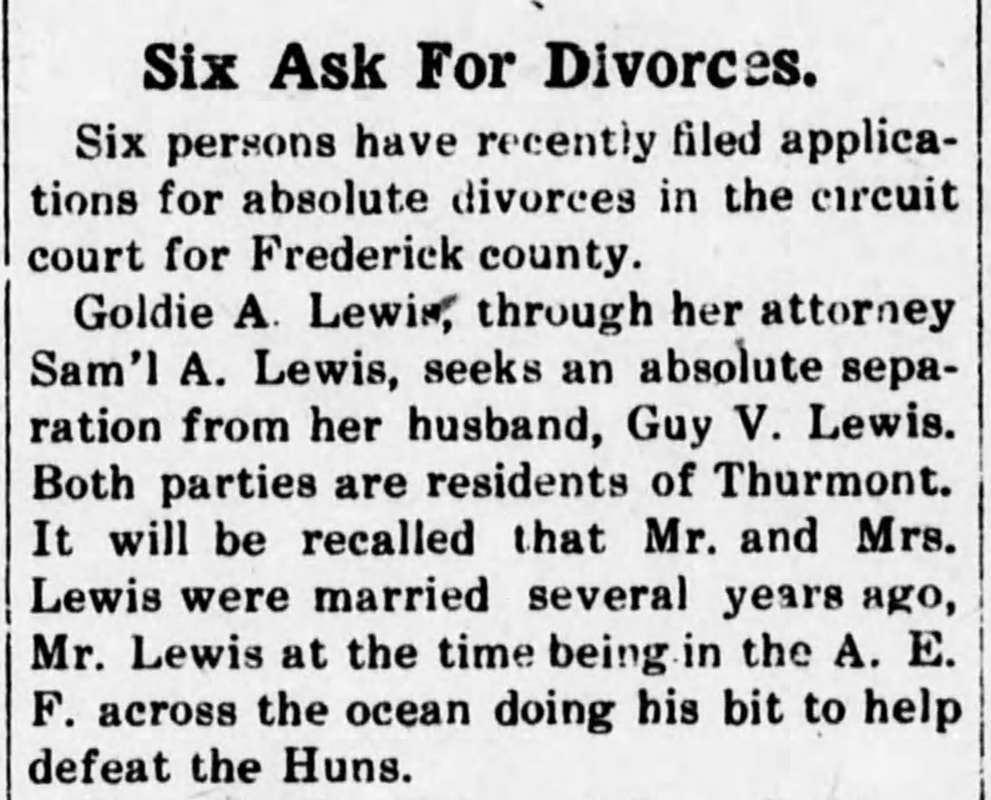

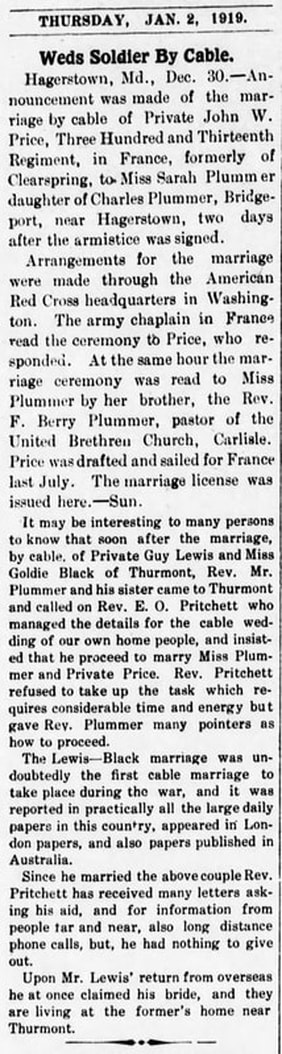

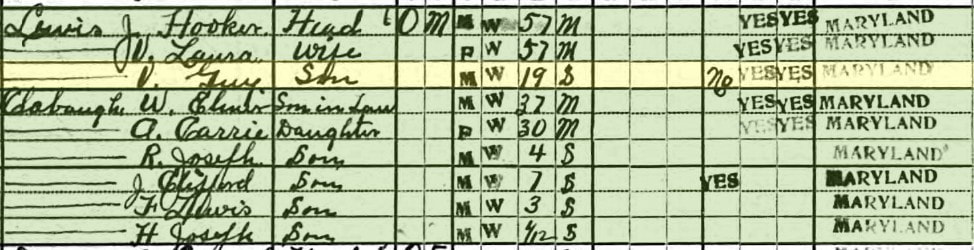

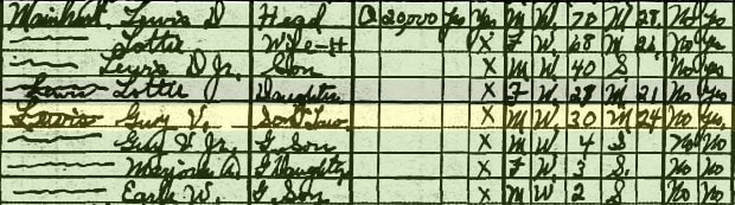

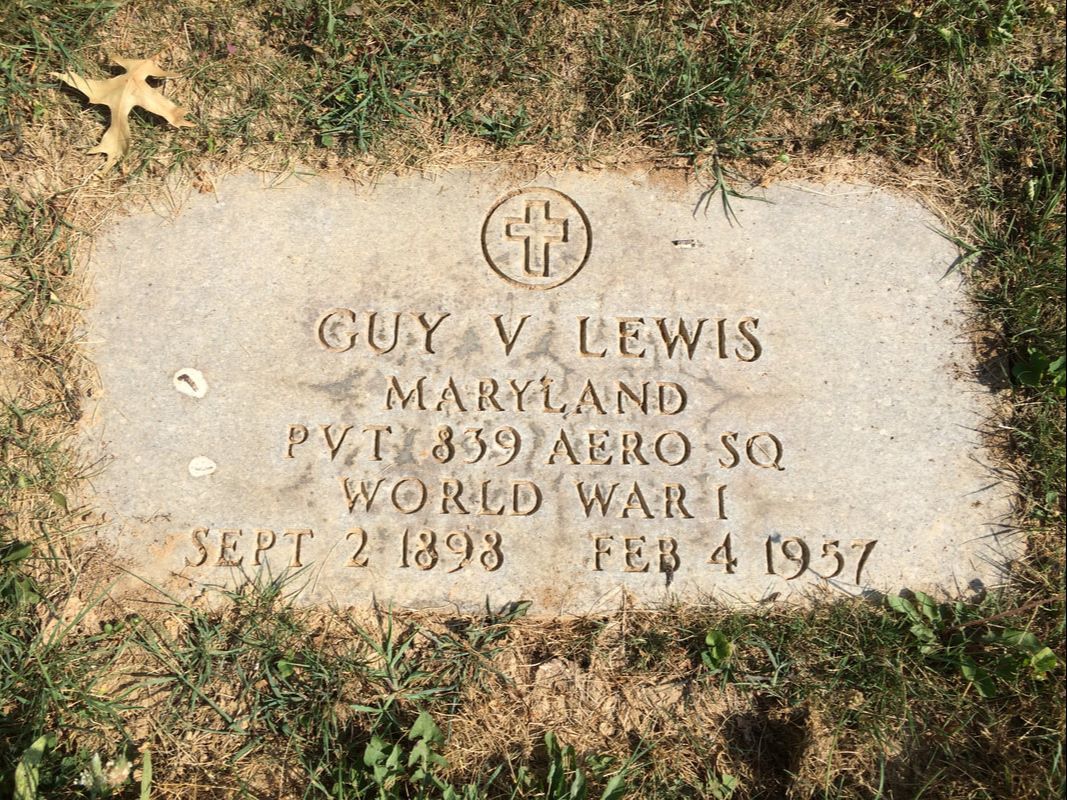

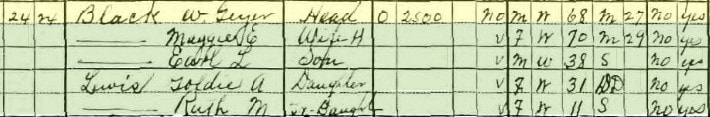

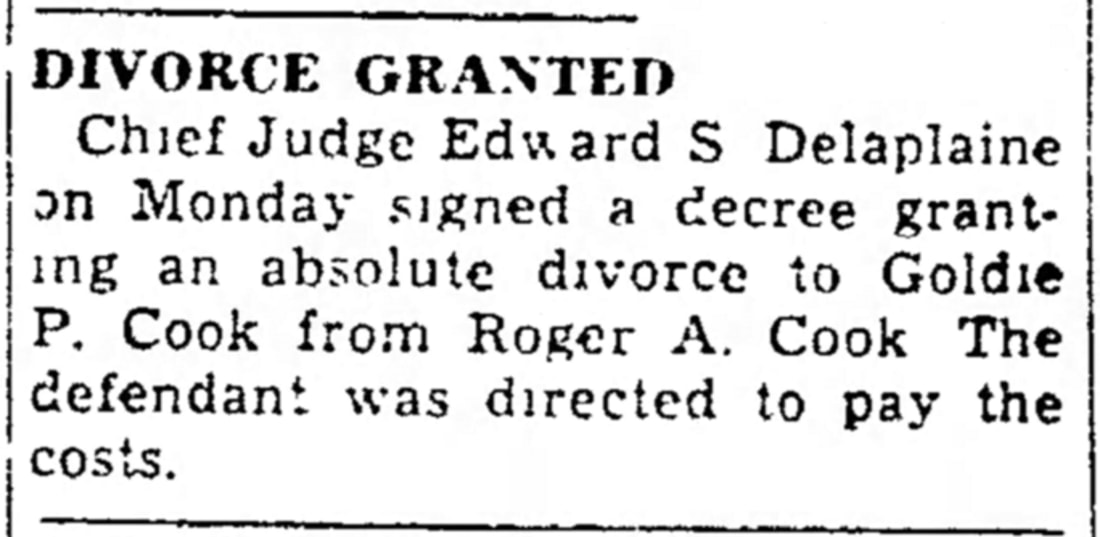

When you think of past wars, be it the American Revolution, Civil War, or World War II, the last thing you may think of is a wedding. Armed conflicts just don’t provide the romantic backdrop young “brides to be” dream of as little girls. As for guys, they may have “played war” as children, or in today’s age, war-inspired video games such as Call of Duty, but I would wager that marriage is seldom pondered while engaged in these pursuits. For history wonks like me, one of the best features of the Frederick News-Post is the Yesterday feature which recollects happenings here in Frederick, Maryland as they were covered in the local paper “on this date” at the intervals of 100, 50 and 20 years ago. Some of you may have seen an entry under the 100 Years Ago heading for July 16th, 1918 which chronicled an exchange of marriage vows between a local couple separated by the Atlantic Ocean. At this time, a young US Army serviceman was tying the knot with a young lady from his hometown of Thurmont (MD).  Trans-global communication is commonplace today, and has been for decades. Anybody with a smart phone device can “video-chat” (using computer software such as Skype) with a friend anywhere on the planet, as long as there is cell signal. Many first saw this as a future possibility on the Hanna-Barbera Jetsons cartoon from the early 1960’s. Our marriage in question, however, took place in 1918. Just think of the telegraph and telephone service of the day, requiring an intricate set of lines and operators who physically made, or recorded all the connections and communications by hand. This was the situation involved here as an elaborate choreography of communication over cables was necessary. Actual telegrams were sent via underwater cable between the two continents. These were known as cablegrams.  The Wedding Participants Nineteen year-old Guy Vincent Lewis of Thurmont was serving in the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe during World War I. He had enlisted in the Regular Army on December 13th, 1917 and was sent to the 2nd Training Brigade at Kelly Field, Texas. He was then assigned to the 38th Reconnaissance Squadron at Camp Arthur, Texas. On February 4th (1918), Private Lewis became part of the 839th Aero Squadron, and was duly shipped overseas on April 16th, landing in England. The lovely bride was named Goldie Anita Black, born January 20th, 1899, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William G. Black of Thurmont. The Blacks owned a farm on Apples Church Road and were proud members of Thurmont’s Methodist congregation. On the big day, July 15th, 1918, Private Lewis married Miss Black—with the wedding taking place in two separate locations. Guy Lewis was currently stationed at an air base in Toul, France, while Goldie was in the confines of her home in Thurmont—3,000 miles across the sea from her groom. Both parties were in the company of clergymen at the hour of 8:00PM (Maryland Time), 2:00AM in France. Rev. E.O. Pritchett, pastor of Thurmont’s Methodist Episcopal Church, administered the marriage vows on the bride’s “stateside” behalf. In France, Lewis’ religious proxy was an Army chaplain known only as Lt. Warred. Guests of the wedding gathered at the Black family home and included the fore-mentioned bride’s parents, along with those of groom. Private Lewis’ father was J. Hooker Lewis, a renowned former resident of the area and purveyor of a successful orchard business on the eastern slope of Catoctin Mountain. You may recall the name of Charles Lewis, Guy’s older brother, who got himself in a heap of trouble during the infamous Blue Blazes (moonshine) Still Raid of 1929. Guilty or not, Charles Lewis “took the rap” for the killing of Frederick County Sheriff’s Deputy, Clyde L. Hauver, Sr. on the evening of July, 31st, 1929. Charles Lewis may have been on hand at this special occasion, but would spend much of his adult life behind bars after the bloody raid a decade later, serving out his sentence for first-degree murder in the penitentiary from 1930-1950. (See earlier Story in Stone from July 29, 2017 "The Victim of Blue Blazes")  The Lewis-Black marriage was successfully conducted "without a hitch" that mid-summer night, and it made perfect fodder for the press, especially as a rare “feel-good story” amidst the backdrop of such a terrible and lonely war. The story first appeared in the Frederick paper the following day. Soon it was picked up by papers across the nation, and printed. Spending just a few minutes in search, I found the Lewis nuptials covered in papers ranging from Massachusetts, Georgia, Minnesota, Ohio, Iowa and California. Private and Mrs. Lewis were now pseudo celebrities, perhaps in the same vain as earlier Frederick County “marriage exhibitionists,” Ella N. Graser and Jacob M. Kanode who starred in a public wedding at the Great Frederick Fair in October of 1890. The Rest of the Story I was delighted to find that Guy V. Lewis was buried in Mount Olivet, giving me a pass to pen this story for “Stories in Stone.” I was amazed that I hadn’t been alerted to the fascinating tale having spent years producing a comprehensive history documentary about Thurmont and its rich heritage. The name of the film (completed in 2014) is “Almost Blue Mountain City: the History of Thurmont, MD. The Lewis’ marriage story would have fit in perfectly with a portion of the project that explored local involvement in World War I. We talked about the boys who served and those lost in “the Great War,” prompting townspeople to create Thurmont’s Memorial Park on a plot of ground on East Main Street. A bronze plaque lists 119 local boys who served in the conflict, 11 of whom made the supreme sacrifice. Scarlet oak trees were planted in memory of each of those killed. Looking at our cemetery records, I noticed both a glaring omission, and a strange addition. First the omission—there was no sign of wife Goldie A. (Black) Lewis. Well, this simply could have been due to a burial elsewhere, perhaps back home in Thurmont in the Black family lot at Wellers Methodist Church Cemetery. Now that’s where Goldie’s parents reside, but she’s not in the plot. However, I did find her at the adjacent Blue Ridge Cemetery. She was buried alone, but wore a new surname—Goldie A. Cook. “Oh no, I thought!” What a shame, as the “marriage over cable” story was so romantic and newsworthy, even more so during a war. I quickly checked our cemetery records and saw that Guy, unlike his former wife, was indeed buried here at Mount Olivet but with a second wife, Lottie Maude Mainhart (Lewis). I scoured old newspapers and found a brief article relating to Guy’s return from war in December 1918. Sadly, a year later in January, 1920, I found another article announcing Goldie filing for divorce from Guy in 1920. When I began looking for the couple in census records, I noticed the presence of a daughter named Ruth Lewis. More interesting was the fact that Ruth was born on August 15th, 1918—exactly one month after the wedding “heard ‘round the world.” So I guess the irony here is that the “romantic, long-distance” wedding was definitely military-related, being a classic “shotgun-wedding.” Well at least I am comforted in knowing that both young lovers found love again, even though their own did not last. Guy Lewis was living back home in Thurmont with his parents in the 1920 US Census. His fortunes would change five years later as he married Lottie M. Mainhart on the 1st of January, 1925. The nuptials took place in Washington, DC, however I couldn't find out if it was a traditional church ceremony, a "justice of the peace" simple deal, or something unique like he did six-and-a-half years earlier. He moved to Lottie's family farm located in Beallsville, between Poolesville and Darnestown, where he would reside up to his death in 1957. I found that Guy and Lottie were responsible for planting fruit trees on the Mainhart's farm which had been founded in 1888. Not only did Guy understand the orchard business, having grown up on one in Thurmont, he was one of the first people in the area with a flatbed truck. His key job consisted of hauling the family’s fruit, mainly peaches, to local canneries. The operation would eventually become the wildly successful Lewis Orchards operation that continues today, located at the intersection of MD28 and Peach Tree Road. Goldie Anita (Black) Lewis lived in Thurmont over the next two decades and raised daughter Ruth into adulthood. She remarried a gentleman named Roger A. Cook (1892-1957), sometime after 1940, and took up residence in downtown Frederick at 129 W. Fourth Street. I would discover an article announcing a proposed suit of divorce in April, 1942, but the couple apparently made amends sometime after. Roger would enlist in the US Army six months later, participating in World War II. Maybe there was a “re-connection” while both were separated by the Atlantic Ocean, who knows? Roger went on to become the Superintendent of Frederick City’s Street system, and at the time of his death in May, 1957, was the municipality’s oldest working employee. Goldie remained in Frederick, dying in 1991. As for the Lewis’ child, baby Ruth grew up fine and would one day marry Claude S. Humerick. Ruth spent her life in Thurmont, working at the Claire Frock Company and later Thurmont High School before passing in 2004. She had four children (although two died young) and our grandchildren. She is buried in Blue Ridge Cemetery, the same as her mother. I looked again at our cemetery records and found a gravesite of one, Guy V. Lewis, Jr. (1925-2003). Guy, Jr. was a product of his father’s second marriage and one of six children. I noticed a message on this tombstone, along with his obituary) recognizing him as a beloved “Pop-Pop” to his four grandchildren. In total, Guy Sr. had 12 grandkids via his remarriage. So regardless of the divorce of Guy V. Lewis and Goldie A. Black, the relationship, and subsequent ones, continued to bear fruit as future generations were positively affected and impacted. I’m sure there is much more to the story (and pictures of the participants out there as well), but what a nice takeaway, proving that everything happens or a reason. And one more thing. Goldie Black Lewis Cook had a brother named Willis Glen Black (1896-1937). Willis’ sons (and Goldie’s nephew) Elmer “Lee”(1923-2015) and Harry (1921-1998) would enter into the fruit industry as well. In 1950, Elmer “Lee” Black bought J. Hooker Lewis’ (Guy V. Lewis’ father) Strawberry Field and started Blacks Hilltop Orchard. Four years prior (or should I say Pryor as Pryor’s Orchard was opened by a son-in-law of J. Hooker Lewis), Harry Black was responsible for starting an orchard business in 1946 with the help of his wife Helen. This venture, located along US15, just north of Thurmont, is still in operation today. It’s being run by Harry’s children Bob and Pat, and a slew of grandchildren and great-grandchildren. I guess it’s fair to say that the fruit doesn’t fall far from the tree.

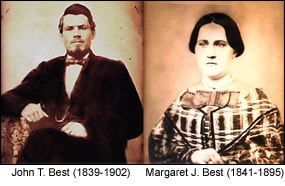

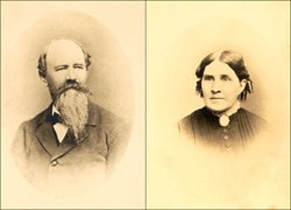

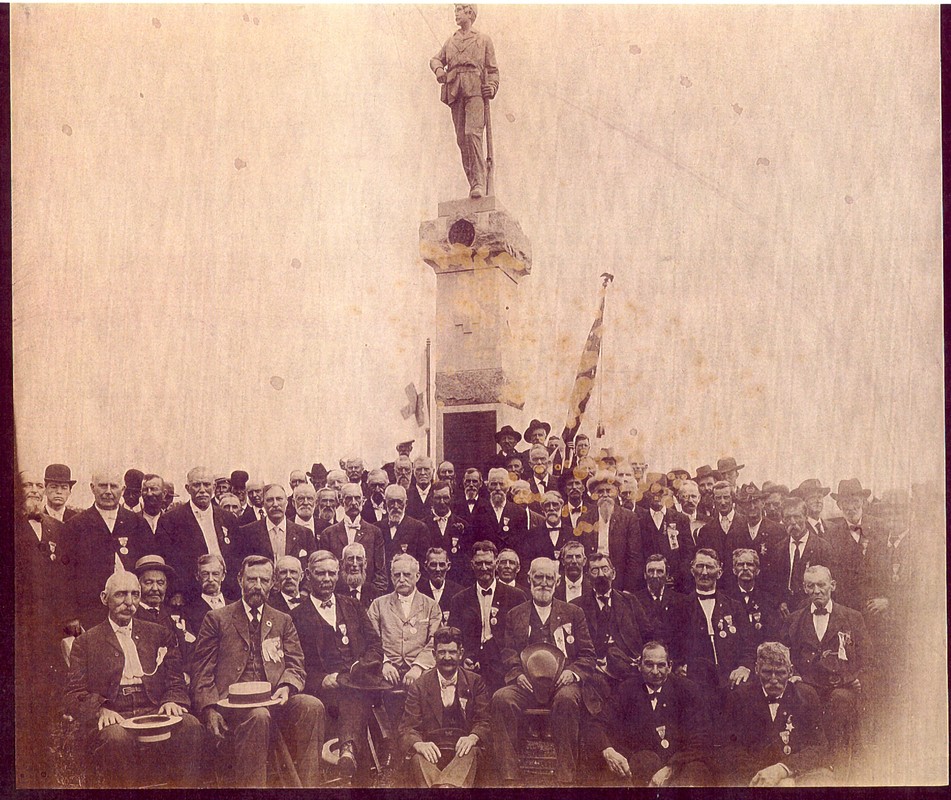

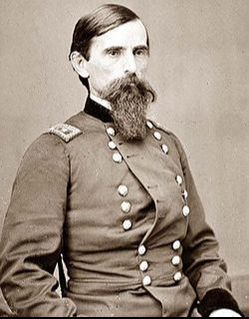

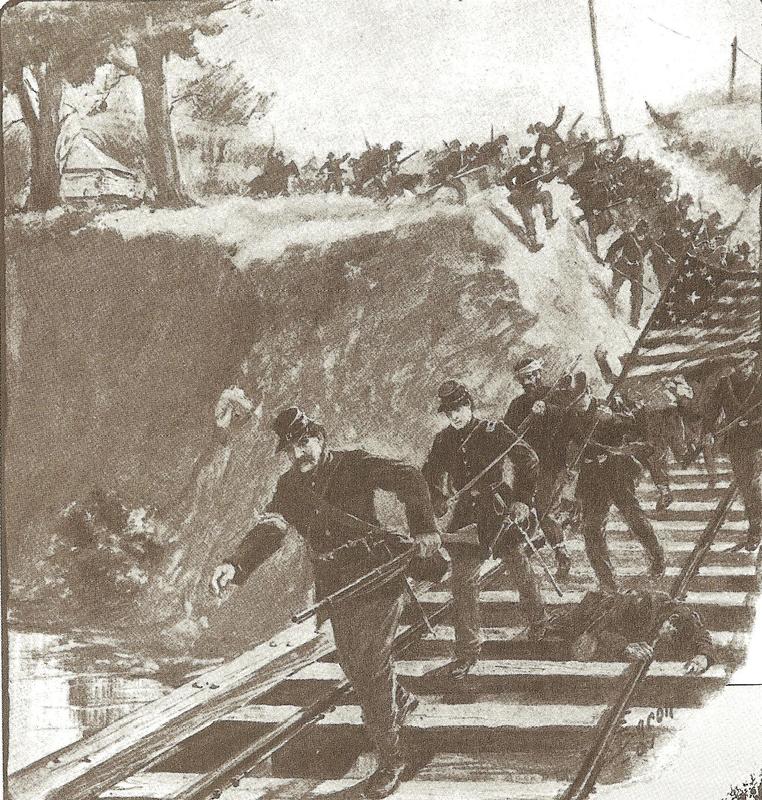

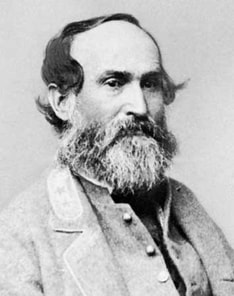

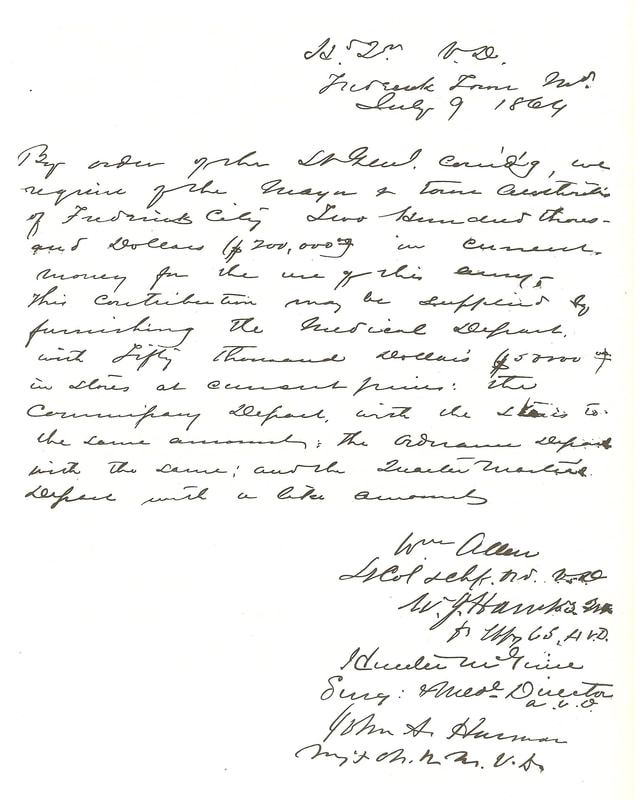

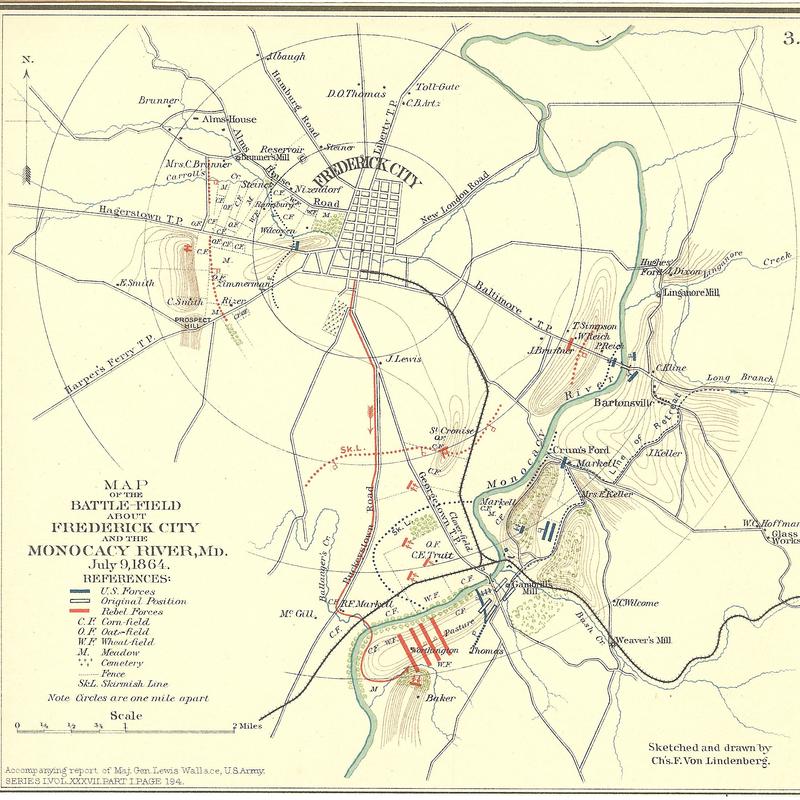

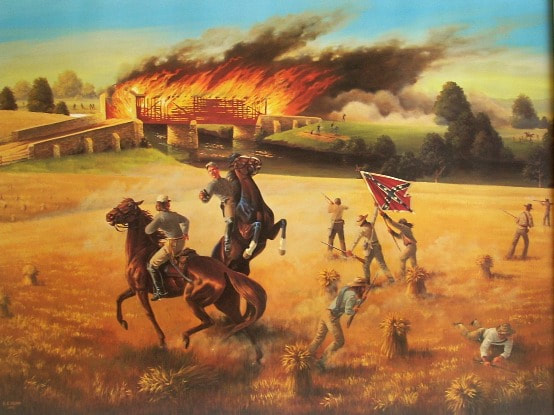

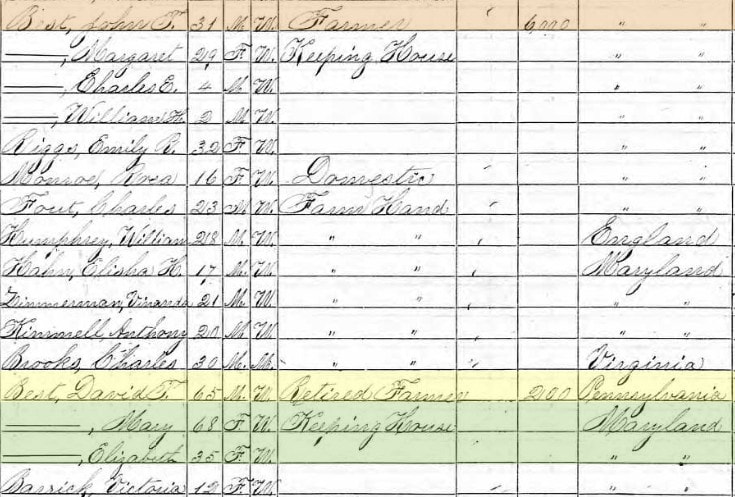

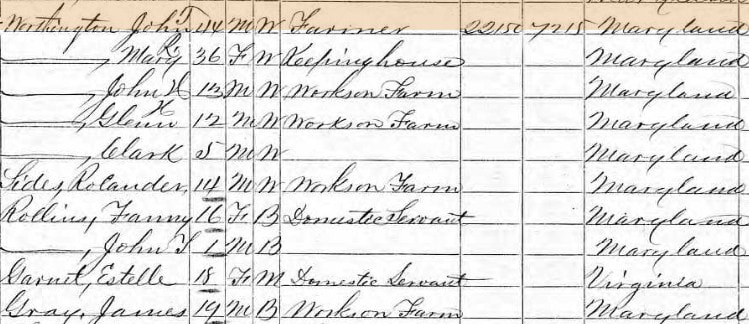

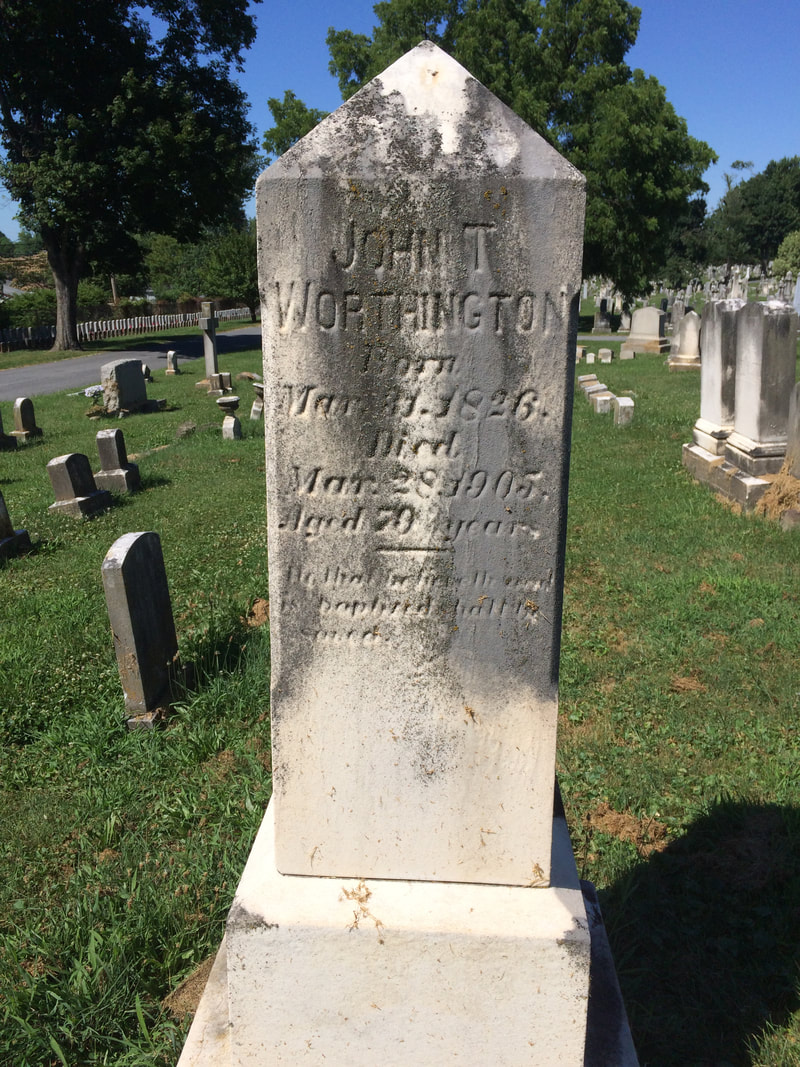

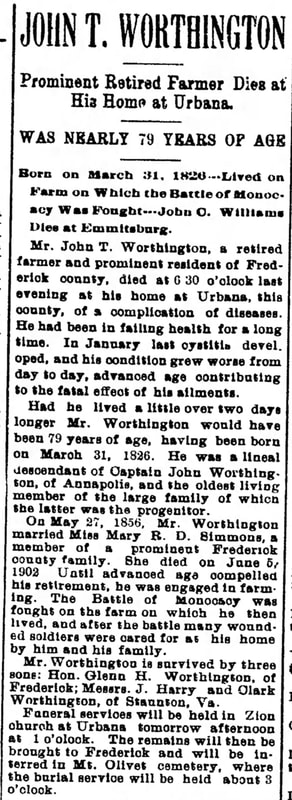

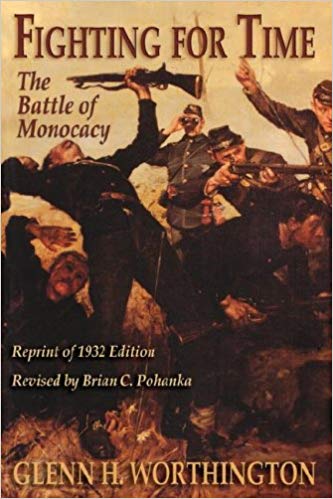

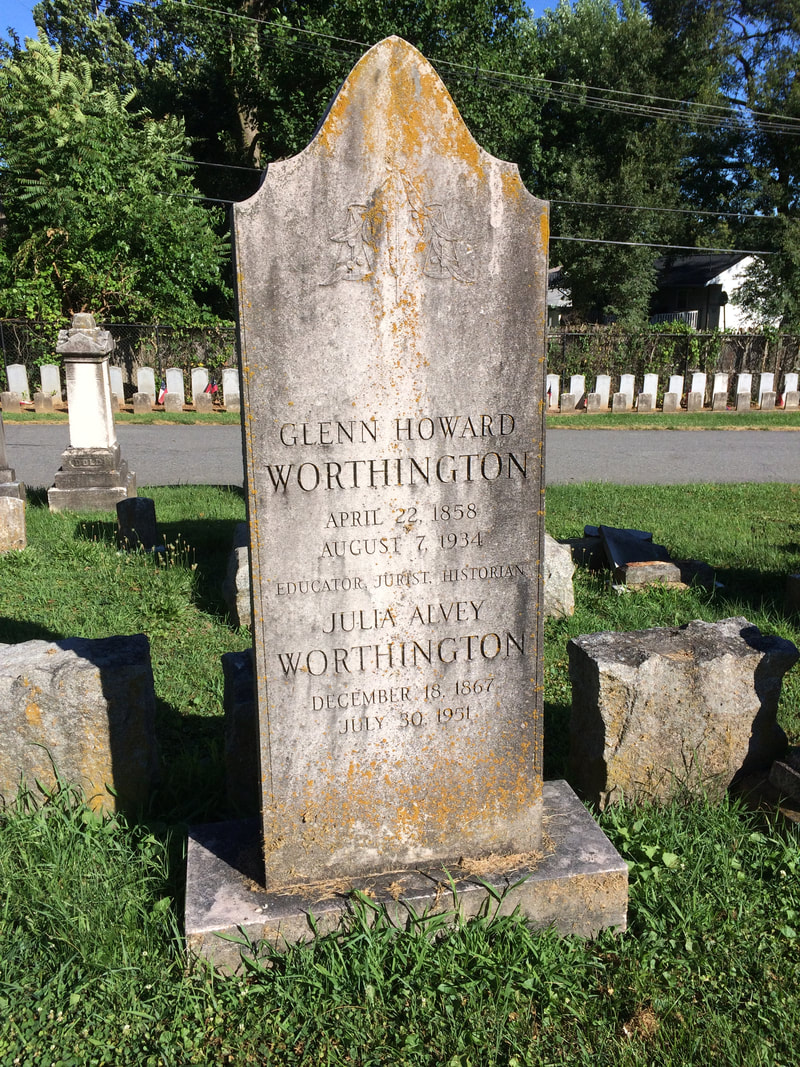

Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) “Captured again -Our old City of Frederick was captured by the Rebel forces under General Jubal Early on Saturday, July 9th forenoon or rather morning. They first entered about 6’oclock am from the west. We had no army to protect us except 2 or 3000 while the Rebels had from 10-15,000 men. General Early levied a contribution on Frederick of $200,000 which I am told was paid on Saturday. The money was got from the banks and the Corporation became responsible. About 8 o'clock AM on Saturday their wagon train commenced passing through town and it lasted 4 or 5 hours. 4 or 500 wagons must have passed. Down at the Monocacy Junction they had a battle and a goodly number were killed and wounded on both sides.” Jacob Engelbrecht July 11,1864  Monocacy National Battlefield Visitor Center (Frederick, MD) Monocacy National Battlefield Visitor Center (Frederick, MD) July 9th is the anniversary of the Battle of Monocacy, also known as “The Battle that Saved Washington, DC.” For many years now, this date continues to be commemorated at the NPS unit located a few short miles southeast of Mount Olivet Cemetery and the City of Frederick. Much of the Monocacy battlefield remained in private hands for over 100 years after the Civil War. In the decades after the battle, veterans’ organizations placed monuments and markers to specific units on the battlefield, including the 14th New Jersey (dedicated in 1907), the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, and Vermont markers. Other monuments have been added.  In 1928, Glenn H. Worthington, the owner of a large portion of the northern segment of the battlefield, petitioned Congress to create a National Military Park at Monocacy. Though the bill passed in 1934, the battlefield languished for nearly 50 years before Congress appropriated funds for land acquisition. Once funds were secured, 1,587 acres of the battlefield were acquired in the late 1970s and turned over to the National Park Service for maintenance and interpretation. The historic Thomas Farm, scene of some of the most intense fighting, was acquired by the National Park Service in 2001. Preservationists lost fights in the 1960s and 1980s when Interstate 270 was constructed and later widened, bisecting a portion of the battlefield.  Monocacy Junction Monocacy Junction One-hundred and fifty-four years ago, a very eventful week was kicked off on July 5th, 1864, when Union Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace arrived at Frederick Junction, also known as Monocacy Junction from Baltimore. The future author of Ben Hur would personally take command of the force concentrated at the railroad junction adjacent the intersection of the Old Georgetown Pike (MD 355) and the Monocacy River. By July 7th, the Union Army that had converged on Frederick totaled about 3,200 men. Wallace and his men were about to square off against Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early and a Rebel force of around 14,000. Wallace found himself commanding the only army protecting Baltimore and Washington from the Confederates. He was facing an opponent of unknown strength and intention. The Confederate Army’s presence came as a major surprise to war weary Frederick County. They had seen these men a year before in July, 1863 with the Battle of Gettysburg. Nine months earlier, Gen. Robert E. Lee had brought his Army of Northern Virginia for the Maryland Campaign and occupied Frederick for nearly a week. Soon after, the first major battles on northern soil would be fought at South Mountain (Sept. 14, 1862) and Antietam (Sept. 17th, 1862). On July 8th, Gen. Early levied his infamous ransom of $200,000 on Frederick, with the perceived threat of burning the city. Frederick’s mayor and other leaders hastily raised the money from the towns’ banks. Meanwhile, Wallace had doubled his number of union defenders to nearly 6,000 troops. The next day, July 9th, Early’s advance southward toward the nation’s capital was delayed at the Monocacy River below Frederick by the Union contingent under Maj. Gen. Wallace. Wallace knew he had very little chance of defeating Early’s veterans, but hoped to stall the Confederates in order for reinforcements to refortify Washington. In the vicinity of Monocacy Junction, a handful of families would soon find their idyllic properties turned into killing fields. A series of farms is usually talked about as encompassing what is now the Battle of Monocacy. These include the Best Farm, the Worthington Farm, the Thomas Farm, and the Gambrill Mill and Farm. All are named according to current owner (or in one case tenant) during the battle. The Confederate approach came primarily from the north via South Market Street as it doubled as the Old Georgetown Pike (MD Route 355). Many soldiers passed by Mount Olivet on their way to battle. Some of these, perhaps, would find their way back inside the cemetery’s gates as a casualty of war. The Union men were lying in wait on the south side of the Monocacy River. There would soon be an engagement at the Best Farm, the former headquarters site of generals Lee, Jackson and Longstreet during the earlier 1862 campaign. The fiercest fighting north of the river occurred to the immediate east of the Best Farm around the railroad junction area and where a covered bridge aided the Georgetown Pike in crossing the river.  The Rebels were successful in fording the river at multiple spots. Throughout the day there would be fighting between the Worthington and Thomas farms. The Union retreated back towards the Gambrill Farm, a place that had earlier received some of the first artillery shots because its proximity to the river. Fittingly, the battle concluded back on the Best Farm and resulted in the only Confederate victory in a major battle on Maryland soil. It basically took an entire day—an important day of travel that was lost to Gen. Early and the Confederates. The Rebel victors camped in this vicinity for the night, while the Federal soldiers retreated back toward Baltimore. While Early was free to march on Washington, the delay at Monocacy bought the needed time for the Union to bolster its defenses around the nation’s capital. Days later, Gen. Early would be thwarted at Fort Stevens (near present-day Silver Spring, Maryland). They now Rest in Peace We hear so much about the military officers of war, and the soldiers who did the bulk of the fighting, and dying. In most cases, these individuals made the choice to do so. As for the civilians of a place, be them in Frederick or elsewhere, the war came to them. This was not a choice that they had a say in. Battles happened with little, or no warning. In most cases, property owners lost their livelihoods, and farms that had been in the same familial hands for generations could be demolished in a day. I did a little searching around Mount Olivet to find connections to the Battle of Monocacy. Of course we have here plenty of the soldiers who participated in the battle, including those who “they here gave the last full measure of devotion” on our battleground south of town. I specifically looked for the familiar civilians linked to the farms on which the battle was fought. Monocacy Battlefield’s website, https://www.nps.gov/mono/index.htm was a huge help in garnering background on these folks.  Charles E. Trail (1826-1909) Charles E. Trail (1826-1909) The Bests The Best Farm comprises the southern 274 acres of what was originally a 748-acre plantation known as L'Hermitage, and was home to the French expatriates known as the Vincendière family. The Vincendieres sold the farm in 1827, and after several transfers of ownership it was acquired by Charles E. Trail in 1852. This was the same year that Mr. Trail and other leading citizens were in the process of establishing the Mount Olivet Cemetery Company. Trail was on the cemetery’s first Board of Directors, and was influential in getting the cemetery created in the first place. Back to the Best Farm, the Trails never occupied the farm and instead operated it as a tenant farm until it was acquired by the National Park Service in 1993. For many years during Trail's ownership, members of the Best family leased the farm, beginning with David Best and wife Anna Mary (Lantz) Best and their four children. Because of its proximity to the Georgetown Pike and Monocacy Junction, portions of both the Union and Confederate armies camped at the Best Farm throughout the Civil War.  The property included 375 acres at the time with 50 acres of wooded/unimproved land. This portion was known as “Best Grove.” This is where Gen. Lee had his camp in September, 1862. On September 13th, 1862, during the Maryland Campaign, Lee's lost order No. 191 (which outlined his army's movements) was found near the Best Farm by soldiers from the 27th Indiana. Passed up through the chain of command, the captured order gave Union Gen. George B. McClellan advance notice of his enemy's movements. In 1864, John Thomas Best (and wife Margaret J. (Dorsey) Best) took over operation of the farm from his father David. The first year of farming on his own looked promising, but soon proved disastrous. During the Battle of Monocacy, Confederate artillery set up on his farm and sharpshooters took positions in the barn. They fired at Union troops guarding the covered bridge over the Monocacy River on the Georgetown Pike. The Union returned fire, however, setting the Best's barn ablaze and destroying the grain, hay, tools, and farming implements kept there. Confederate infantry, using the farm as a staging area, soon destroyed any crops left standing in the fields. The covered bridge over the Monocacy would be destroyed as well. Undaunted by this disastrous first year, John Best continued to successfully operate the farm for many years following the Civil War. John T. and Joanna Best can be found in Area H/lot 331, adjoining that of his parents.  John T. and Mary Worthington John T. and Mary Worthington The Worthingtons John Thomas Worthington was born in 1826 into an extended Frederick County family of “prominent” farmers. John married Mary Ruth Delilah Simmons in 1856 and the couple eventually had four children, three of whom survived childhood. In 1862, Worthington purchased “Clifton Farm” adjacent to the Monocacy River, renamed it “Riverside Farm,” and settled his family into their new home. The morning of July 9th, 1864 was spent preparing for the impending battle. Hoping to minimize his loss of property, Worthington instructed the family’s slaves to gather wheat from the field, and then to take the horses to nearby Sugar Loaf Mountain and hide them in the “darkest and loneliest place you can find.” However, Confederate soldiers discovered and confiscated all nine horses, at a substantial cost to John Worthington. After the horses were hidden, the slaves busied themselves placing tubs of water in the cellar and boarding up the windows.  Depiction of Glenn Worthington watching the battle from his cellar (Keith Rocco) Depiction of Glenn Worthington watching the battle from his cellar (Keith Rocco) During the Battle of Monocacy, Confederate troops crossed the Monocacy River onto the Worthington Farm, initiating three attacks from the farm fields. Worthington and his family took refuge in the cellar, and through the boarded-up windows, six-year-old Glenn Worthington watched intently as the fighting raged in front of the house. In his memoir Fighting For Time, Glenn Worthington recalls that, “Glimpses of blue could be seen as they passed windows. More than one received his death wound close to the house and fell there to die, in Worthington yard.” After the battle, John Worthington and his family assisted with the care of the wounded soldiers. Glenn and his seven-year-old brother Harry were sent into the nearby fields to gather sheaves of wheat for use as a bed for a wounded Confederate soldier. While the wounded were being cared for, other Confederate soldiers gathered the muskets that had been thrown away by the retreating Union soldiers. The muskets were placed in a pile in Worthington’s back yard and set on fire, leaving only the gun barrels and bayonets. Glenn desired one of these bayonets as a souvenir. He procured a stick and began to drag the bayonet from the embers, and as he stooped to retrieve his prize, an ember touched a discarded paper cartridge which exploded in his face. A Confederate soldier carried him, blinded and yelling, into the house. Luckily Glenn’s eyesight was not damaged by the explosion and he made a full recovery. After the Civil War, John Worthington continued to be a successful farmer, managing to acquire an additional farm as well as improve “Riverside Farm.” The Worthingtons also maintained a townhouse in Frederick until the 1890s, which John inherited from his father, James W. Worthington. John and Mary Worthington remained at “Riverside Farm” until their deaths in 1902 (Mary) and 1905 (John). The farm passed to Glenn and his brother Clark, and although neither lived there, it remained in the Worthington family until 1953.

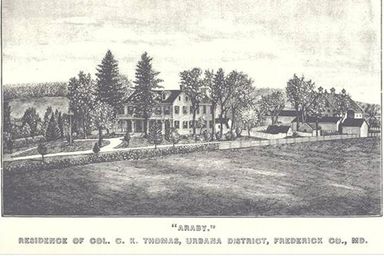

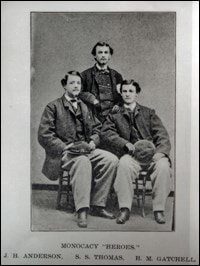

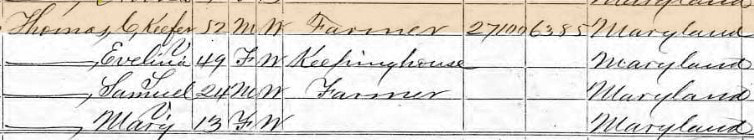

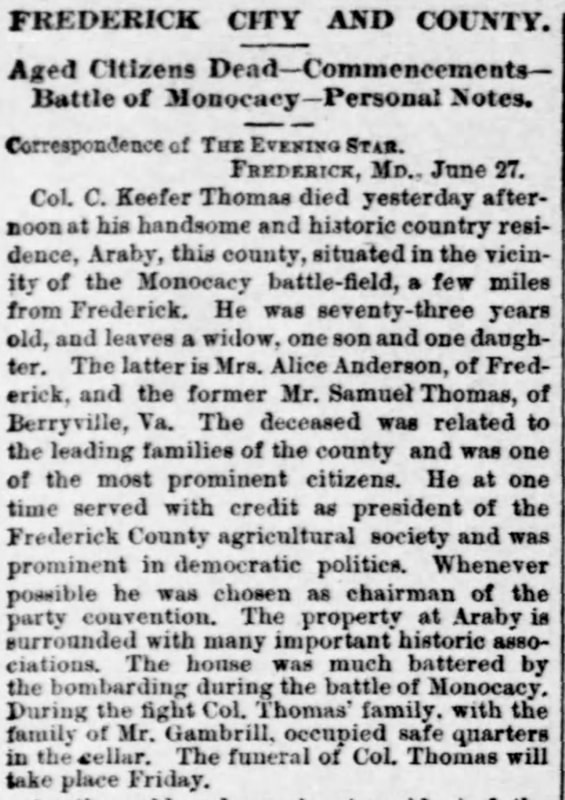

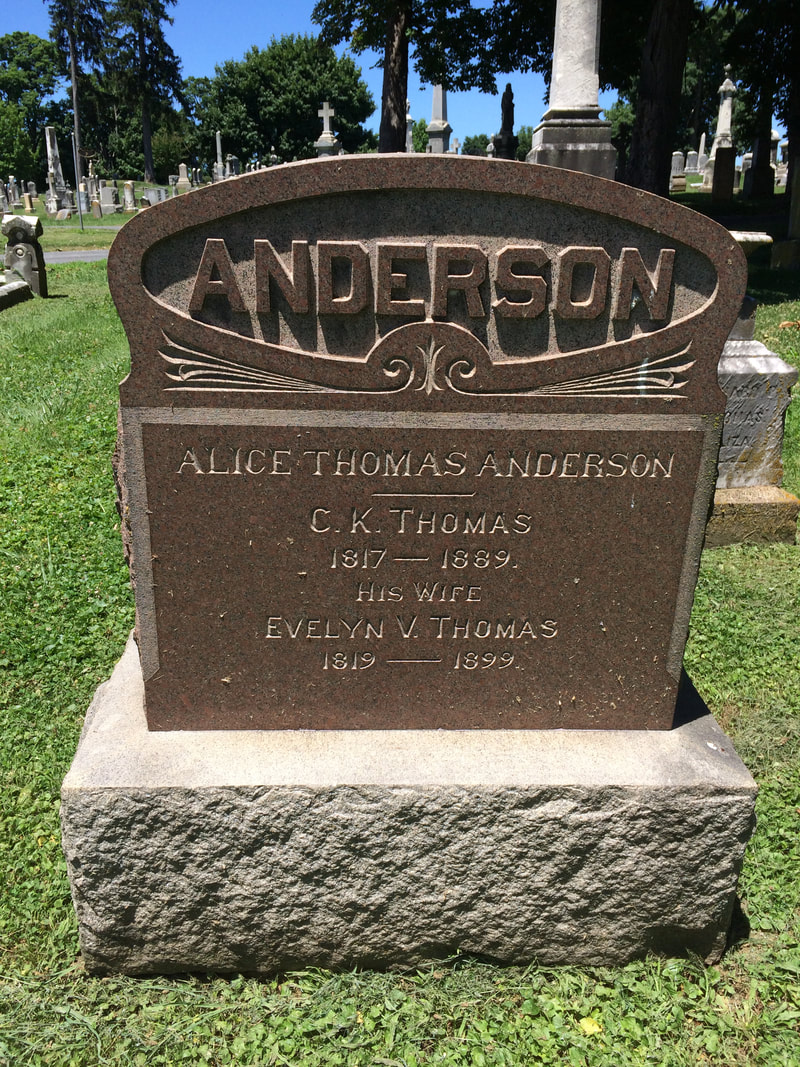

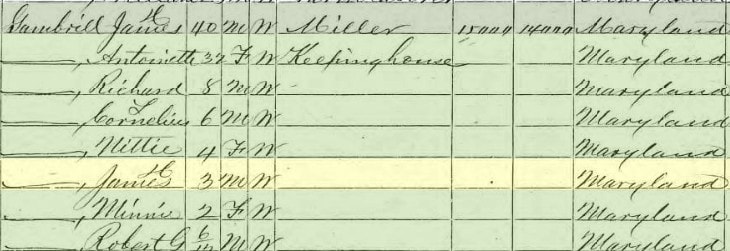

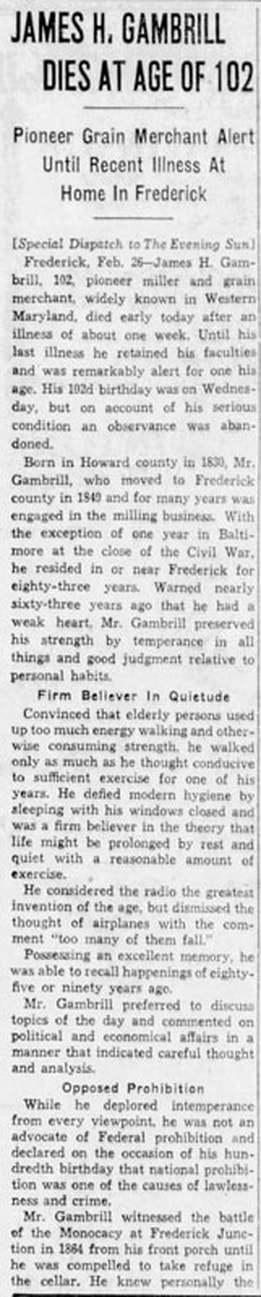

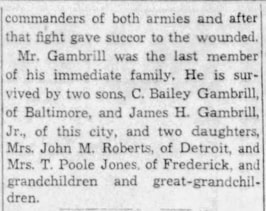

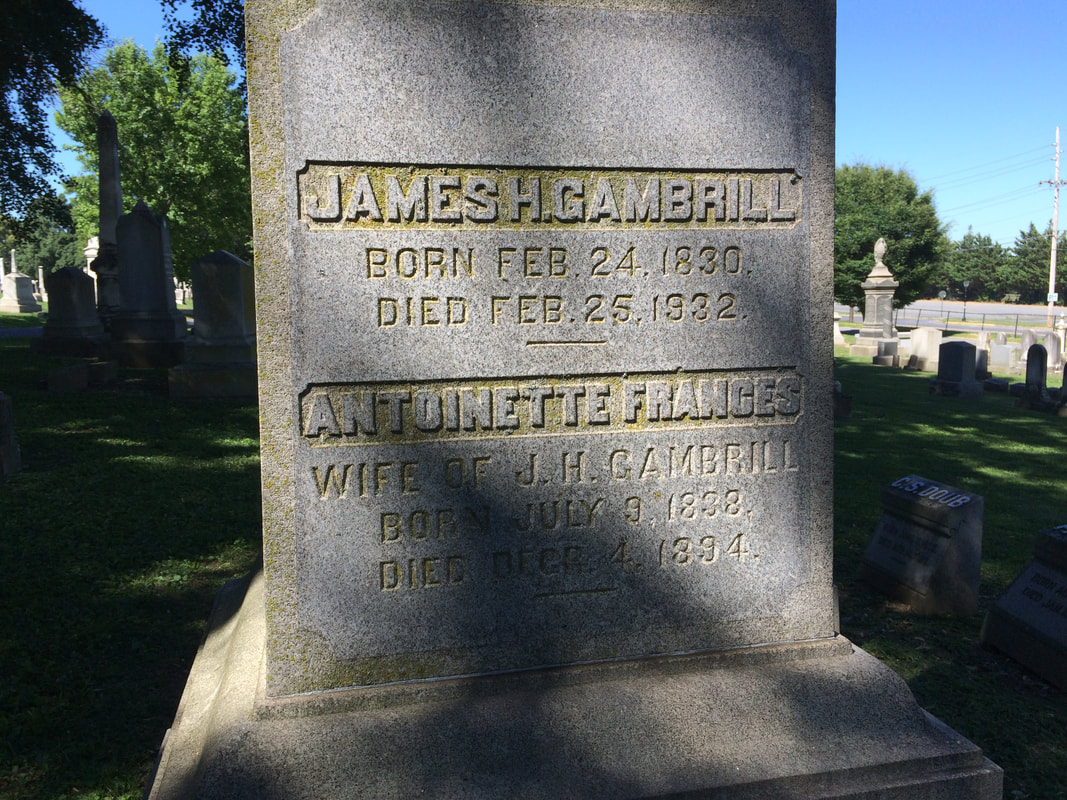

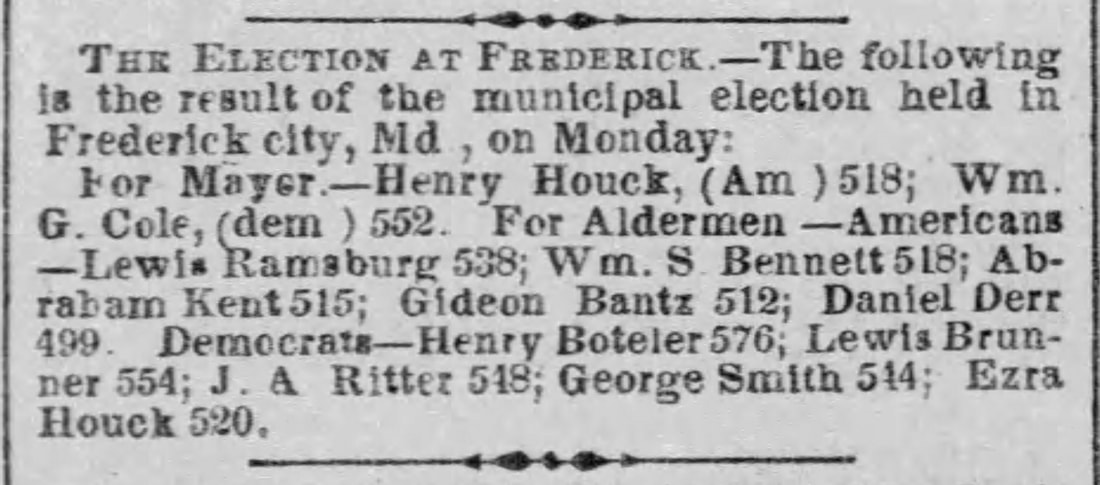

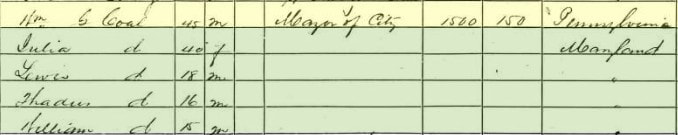

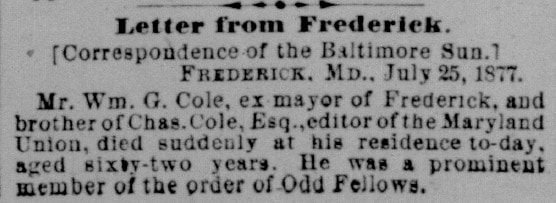

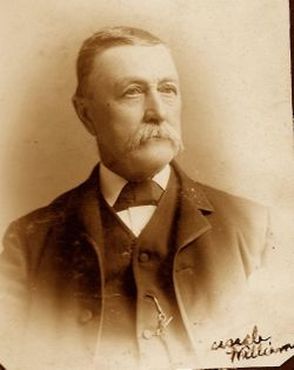

Thomas Family Born in 1818, Christian Keefer Thomas was a Frederick County native. For a large part of his professional life, however, he resided in Baltimore, where he was a partner in the wholesale dry goods firm of Devries, Stevens, and Thomas. In 1839, Thomas married Evelina Virginia Buckey, and within a few years their son Samuel was born. Around 1860, Thomas sold his interest in the dry goods business, and purchased the Araby Farm that same year for $17,823.75. Thomas returned to his native Frederick County to retire, hoping to avoid the impending violence and unrest of the Civil War. The Thomas family had hardly settled in before the Civil War came to them. Because of its strategic bridges, roads, and railways, both Union and Confederate forces were active in the Monocacy area throughout the period of conflict, particularly during the Antietam (1862) and Gettysburg campaigns (1863).  Samuel B. Thomas standing behind his two friends Samuel B. Thomas standing behind his two friends Although he owned slaves and is generally thought to have been sympathetic to the Southern Cause, C. K. Thomas had extensive interactions with the Union army. During the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863, Union Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock headquartered in the Thomas House. Thomas was also friendly with several soldiers from the 14th New Jersey Regiment, who camped nearby at Monocacy Junction during the winter of 1862 and 1863. During the Battle of Monocacy, the Thomas family hid in the cellar while heavy fighting raged around them. Battle accounts record that the fighting "swarmed" around the Thomas House and outbuildings. The house changed hands several times over the course of the day, and Union sharpshooters occupied the upper floors before being flushed out by Confederate artillery. Unfortunately, C. K. Thomas' son Samuel and two friends had come to visit for the weekend. They were captured by the Union Army and impressed into service. These young men were eventually released and managed to escape to neighbor James Gambrill's mill where they hid for the rest of the battle. They were eventually reunited with their families back at the Thomas farm.  Thomas House Thomas House Barely a month after the battle, a Union soldier named John Rodgers Miegs passed by the farm and in a letter to his mother, he gave the following description: “I stand at the house of Mister Thomas the other day where our headquarters were camped on the Monocacy battlefield. I have rarely seen a house more scarred by battle than was his. His daughter, Miss Alice, a lovely and accomplished girl was driven for safety with her mother and the rest of the family to the cellar. She declares that she did not feel very badly frightened though the muskets were popping out of the windows and the balls were rattling against the house until a shell crashed through the wall of the dining room and burst just over their heads with only a thin flooring between. Seven shells struck the house and I counted the marks of twenty-six musket balls on one side of the house and discovered many more afterwards. Her father, she thinks, caused them a great deal of unnecessary anxiety by continually going upstairs to see how the fight came on. Our men and the rebels fought hand to hand around the house and the marks of the bloody contest were everywhere visible.” While the Thomas family survived the battle unharmed, the farm continued to be a focal point of military activity—in August 1864, Union generals Grant, Hunter, Ricketts, Crook, and Sheridan used the Thomas House to plan the Shenandoah Valley campaign. After the Civil War ended, the Thomas family began the process of rebuilding. By 1868, the farm had recovered sufficiently to serve as the setting for 21-year-old Alice Thomas's wedding. In the 1870s, C. K. Thomas became active in local politics, serving as president of both the Frederick Agricultural Society and the local school board. C. K. Thomas died in 1889, after a prolonged respiratory illness. His obituary described him as a "gentleman of pleasant manners" and remarked that "his beautiful home was noted for its hospitality and delightful social entertainments." The family plot is on Area C, (lot 171). One will find daughter Alice and son Samuel buried here with their parents. The farm remained in the Thomas family until 1910. It was acquired by the National Park Service in 2001.  James H Gambrill and family James H Gambrill and family The Gambrills In 1855, James H. Gambrill purchased the Araby Mills complex from his former employer and mentor, a miller named George W. Delaplane. Gambrill was born in Howard County, Maryland in 1830 into an extended family that comprised a virtual "milling dynasty" in the Baltimore area. James Gambrill married Antoinette Staley in 1860 and the couple eventually had ten children, nine of whom survived childhood. By 1872, Gambrill had achieved a level of prosperity that allowed him to construct a lavish Second Empire-style mansion, one of the largest single-family residences ever built in Frederick County, and one its very few full-scale Empire-style houses. Known as Edgewood, it featured an elegant double parlor, intimate library, wine cellar, and spacious dining room, as well as a third-floor ballroom with a built-in stage. The commodious rooms were accented by imported Italian marble fireplaces, elaborate plaster ceiling medallions, elegant wallpaper, and large crystal chandeliers. The house was richly furnished throughout; in 1876, the Gambrill's furniture was valued at $1,200. John Worthington, owner of the nearby Worthington Farm, owned furniture valued at just $350. James Gambrill's success as a miller and businessman continued through the 1870s and 1880s. Described as "a characteristic American merchant, active, thorough, and full of energy and vim," Gambrill took over a large steam-powered flour mill in downtown Frederick in 1878. In 1882, Gambrill installed roller milling machinery in his Frederick City mill, thus becoming an early participant in the "roller revolution" which transformed the American milling industry. Araby Mill was not converted to rollers, but still produced as many as 12,000 barrels of flour per year at its peak. By the close of the nineteenth century, Gambrill's milling business had failed, primarily as a result of competition with the large-scale milling operations of the Upper Midwest. In 1897, Gambrill sold his house and mill, and while the house continued to be occupied by a succession of owners over the years, the mill never resumed operation. In spite of the ultimate failure of Gambrill's milling operation, when he died in 1932 at the age of 102, his obituary described him as a "pioneer miller." James Gambrill and wife Antoinette are buried in the shadow of a stately obelisk monument on Area C/Lot 24. Mayor William G. Cole William George Cole was born near York, Pennsylvania on June 12, 1815. He came to Frederick, Maryland with his brother Charles Edward around 1835. He was mayor of Frederick, Maryland, from 1859 to 1865, two three year terms. He was mayor in 1864 when during the Civil War General Jubal Early assessed a ransom of the City of Frederick of 200 thousand dollars which was not paid off until 1951.

The 1860 Federal Census lists William as Mayor of the City of Frederick. Listed also are wife, Julia, and sons Lewis, Thaddeus and William. After his terms as mayor, Cole would go on to serve as Superintendent of the Frederick Water Works. He died on July 25th, 1877 and was laid to rest in Area P/Lot 39. Mount Olivet is final resting place to countless others who experienced the American Civil War firsthand. We certainly will present more interesting connections through “Stories in Stone” into the future.

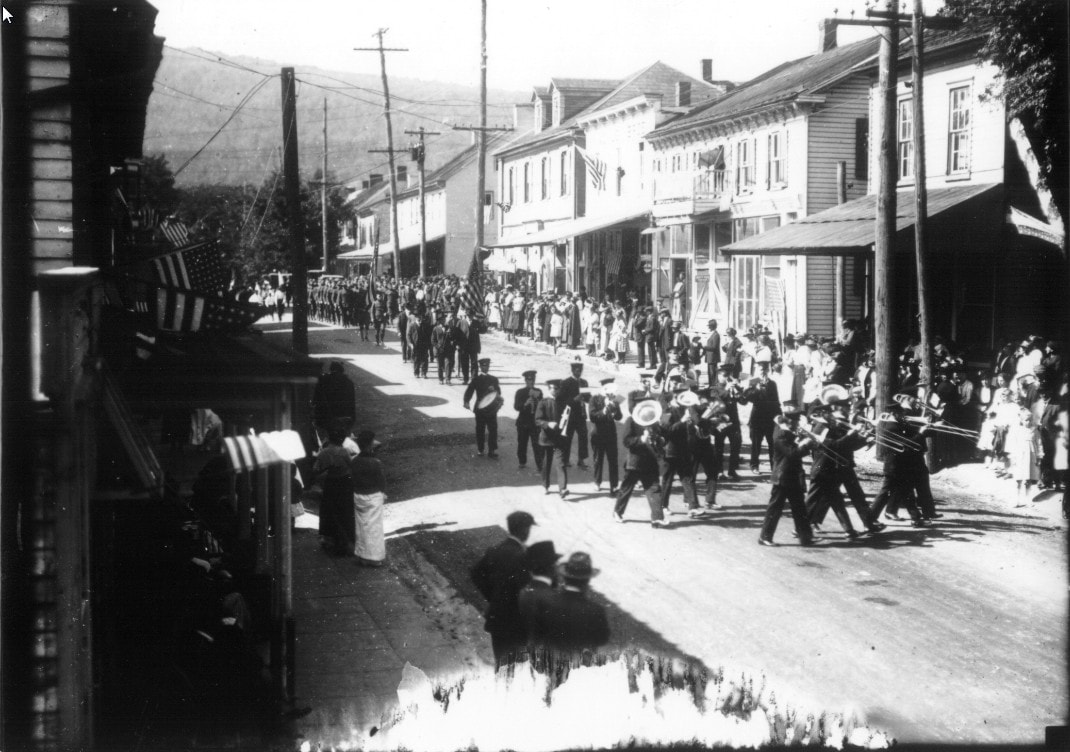

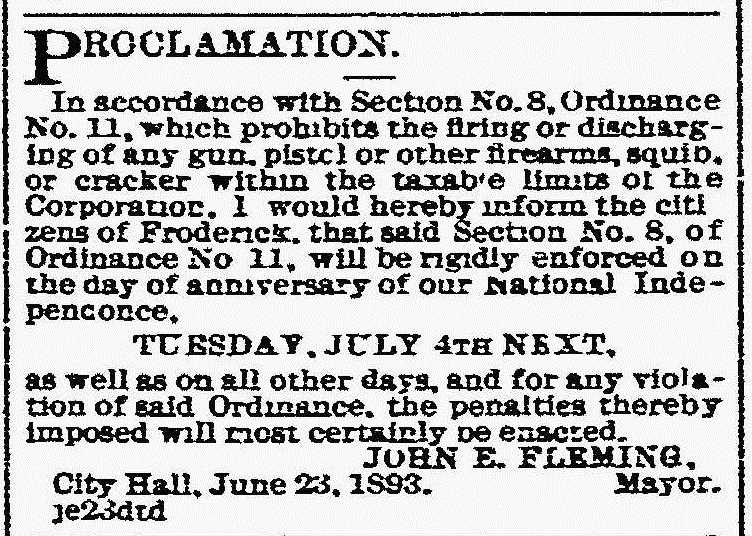

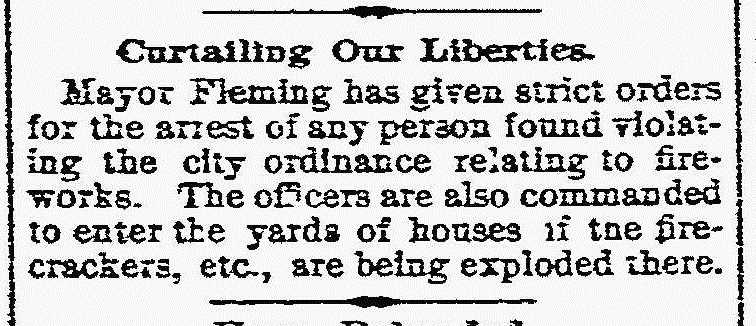

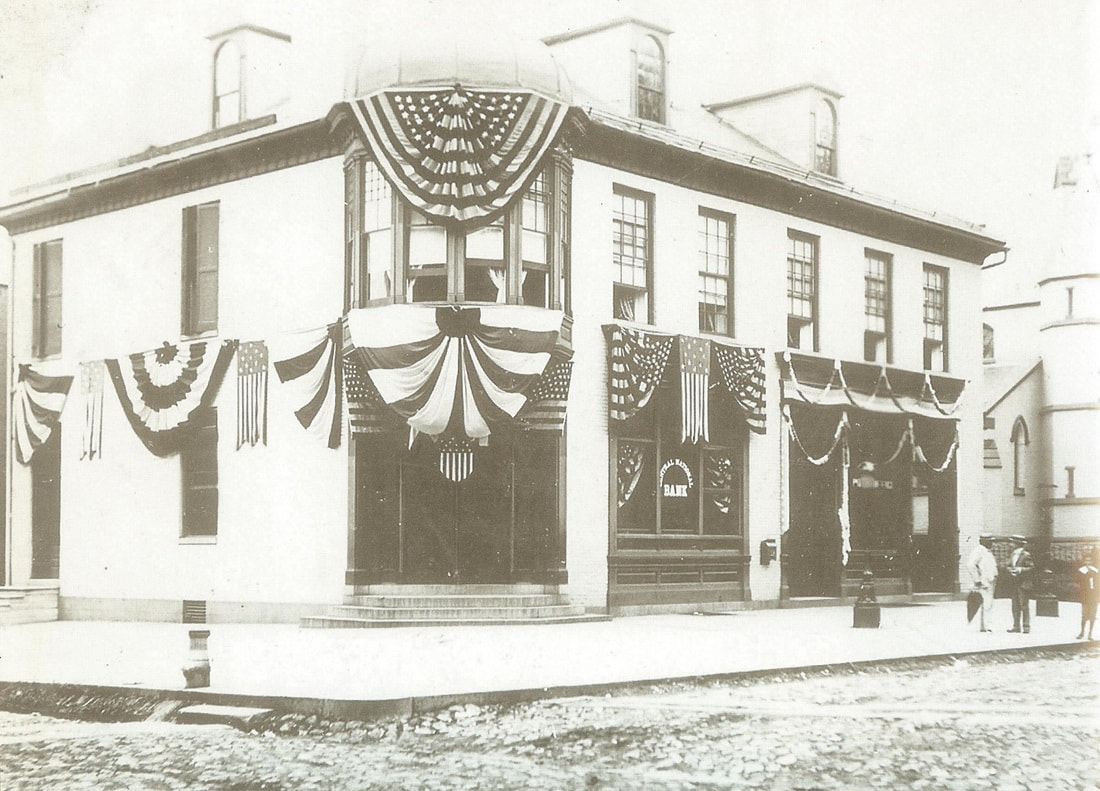

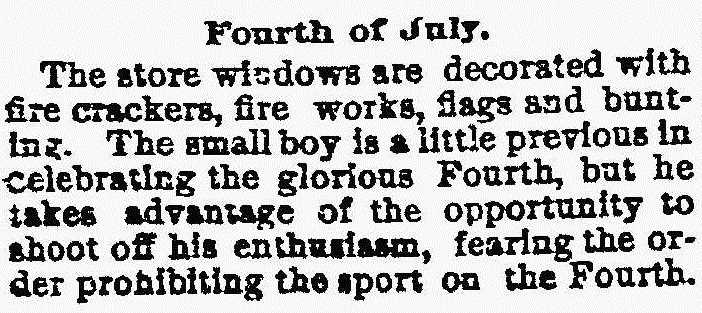

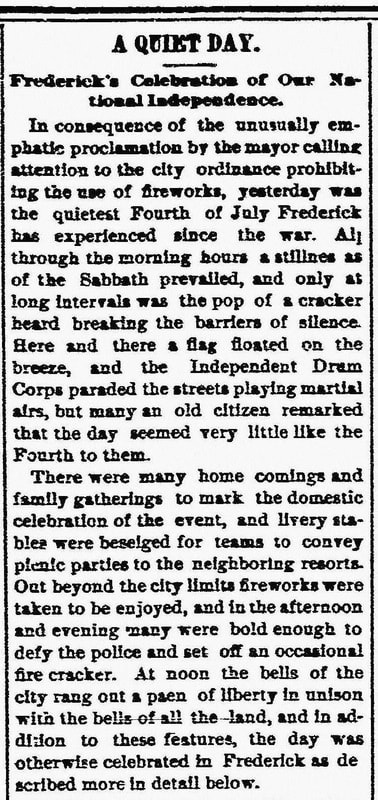

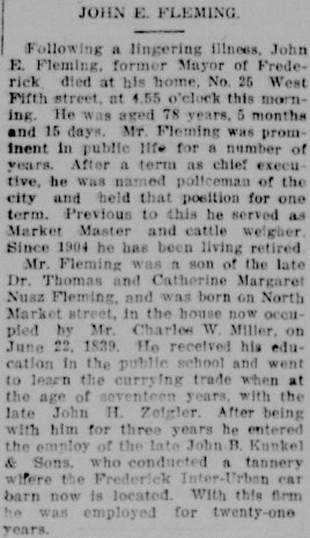

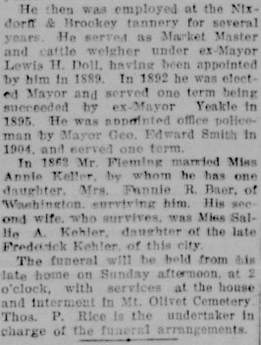

Frederick, Maryland is patriotic, and has always been dating back to July 4th, 1776. For this, we can credit many of those that repose in Mount Olivet Cemetery, be them military veterans, or just plain, good Americans. As we embark on the most popular day, and week, of summer, I wanted to look back at our town (and county) and its relationship to the July 4th holiday. For those on vacation, and others attending a friendly barbecue, Independence Day is generally characterized by the other 3 “R’s”: relaxation, reflection and revelry. Some have labeled July 4th, “The Sunday of the Nation.” The word that best sums up the feeling on this day should be contentment—content by having freedom, possessing unalienable rights and just plain, being proud to be an American. This was also the message given a century ago on July 18th, 1918 by President Woodrow Wilson. The nation was in the midst of World War I, a conflict that involved thousands of Frederick County residents—500 of which are laid to rest here in Mount Olivet Cemetery. President Wilson delivered an address at Mount Vernon (Virginia) where he sought to link the endeavors of George Washington and the other Founding Fathers of the United States with the present efforts in the battlefields of Europe. Wilson told his audience the following: We intend what they intended. We here in America believe our participation in this present war to be only the fruitage of what they planted. Our case differs from theirs only in this, that it is our inestimable privilege to concert with men out of every nation what shall make not only the liberties of America secure but the liberties of every other people as well. It’s ironic that this holiday has roots going back to the specific day in 1776 where the mood of the general populous was one of discontent. The people of Frederick County, Maryland, and countless inhabitants of the other 12 colonies were not pleased with their governance under Great Britain’s King George III, son of our county/city namesake—Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales (1707-1751).  From a historical perspective, it’s interesting to look back and read about past "Independence Days" here in Frederick. A few years back I was contemplating the subject and arbitrarily picked 1893 for some odd reason—a year that certainly does not roll off the tongue for its contribution to county, state or nation. This was 25 years before President Wilson's sojourn to Mount Vernon, and Grover Cleveland was the sitting commander-in-chief. To my surprise, and delight, I found major discontent surrounding the holiday here at home, mainly because residents of Frederick City would/could have no fireworks. Newly elected Mayor John E. Fleming had issued a proclamation on June 23rd (1893) re-stating the city ordinance prohibiting “the firing or discharging of any gun, pistol or other firearms, squib or cracker within the limits of the Corporation.” Mayor Fleming cautioned that this would be rigidly enforced on July 4th.

In essence, this was the 4th of July equivalent of the movie Footloose. Many townspeople were livid, especially wayward teens and ornery children, not to mention more than a few uppity adults. Now in Mayor Fleming’s defense, this particular "Fourth" fell on a Sunday, aka the Lord’s Day. Some decorum needed to be shown churchgoers, because firecracker hijinx was not just something that happened after dusk as we know today. In addition, things had gotten wildly out of hand over the years with the high frequency of firework-related accidents, mamings, etc., especially involving young people. Over the years, the newspapers could always count on these stories to help fill content. Fire risk was also a reality. The mayor had been working hard for months on creating fire-related ordinances and strengthening support for the volunteer fire departments of Frederick. Lastly, who needs people shooting off firearms in town, especially after a long day of celebratory alcoholic libations?  Folger McKinsey, "the Bentztown Bard" wrote for the Frederick News. The Elkton (MD) native gained greater fame with the Baltimore Sun, for which he worked for over 40 years until his death in 1950 Folger McKinsey, "the Bentztown Bard" wrote for the Frederick News. The Elkton (MD) native gained greater fame with the Baltimore Sun, for which he worked for over 40 years until his death in 1950 To the average Joe “Son of Liberty,” this rationale seemed to buck tradition, looking more like an infringement on God-given rights. Isn’t there a Constitutional amendment providing for the right for American citizens to spend Independence Day doing whatever the heck they wanted to show their patriotic devotion to flag and country? The famed "Bentztown Bard," Folger McKinsey, wrote in the Daily News another signature "tongue in cheek ditty": "I believe in letting the eagle scream On the glorious Fourth of July; As firmly I believe that mankind, Would perish 'twere not for pie."

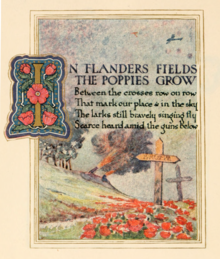

After reading an account of a young doctor attending a party in nearby Jefferson, I certainly have a new view on what was considered “fireworks fun” during the period. It appears that this gentleman was lured in by a flirtatious group of young ladies working in tandem with a group of young hooligans. The boys attached, and lit, a bundle of fireworks to the physician’s frock coat. Luckily he escaped injury, but I can surely think of safer and less stressful ways to celebrate the independence of our nation. Luckily things got back to normal, "July 4th-wise" when Mayor Fleming left office in 1895. As for the good mayor, he rests in an unmarked grave in Mount Olivet's Area H (Lot 162) in between both his first wife Anna A. (Keller) Fleming (1841-1875) and second wife, Sallie Ann (Kehler) Fleming (1850-1934). He passed away on December 12th, 1917 as the United States was mobilizing for that first World War. I find it heartwarming to think that Mayor Fleming has a front-row seat for the nightly fireworks displays presented after Frederick Keys games throughout the summer.  So in closing, I wish you and yours a very happy Fourth! ...but please think twice before shooting off your bottle rockets, cakes, and Roman candles this holiday as the ordinance is still in effect within the corporate boundaries of Frederick. You can still enjoy sparklers without repercussion, both literally and figuratively. All these years later, the municipal government does a fine job of putting on a great rundown of 4th of July activities for its residents, capped with the annual fireworks display. One of the best vantage points for viewing these is none other than Fleming Avenue, of course. While we can demonstrate the proper spirit of patriotism in many ways, take a few minutes to remember why we continue to have the right to celebrate such an incredible annual event and explain this to a young person. Better yet, take a leisurely ride or walk through Mount Olivet as the point will be punctuated by the monuments to Francis Scott Key, Barbara Fritchie, Gov. Thomas Johnson, and graves of service men and women connected to World War I and all other conflicts in which our nation has participated. Because of them, we not only have our freedom, but so much more. Talk about being content!  One of the most iconic things to come out of World War I, fought a century ago, was the war poem entitled "In Flanders Fields." It was written by a Canadian physician named John McCrae who was inspired to write after presiding over the funeral of a fellow soldier. As a result of its immediate popularity, parts of the poem were used in efforts and appeals to recruit soldiers and raise money selling war bonds. Its references to the red poppies that grew over the graves of fallen soldiers resulted in the remembrance poppy becoming one of the world's most recognized memorial symbols for soldiers who have died in conflict. Flanders is a village in northwest Belgium. Those native peoples hailing from the area of Flanders, along with those speaking the Flemish-language, are known as Flemings. Although Mayor John E. Fleming may not have given Frederick what it truly wanted on July 4th 1893, possible distant cousins of the man could have more than made up for it: Alexander Fleming who gave us penicillin (1928), Ian Fleming gave us James Bond, and Peggy Fleming who gave us the joy of IceCapades. Now let's make some noise for the Flemings, and more importantly, all Frederick County's patriots, past and present! Information coming soon on special commemorative programming at Mount Olivet over the weekend of November 10-11, 2018 (Veterans day). To learn more about World War I veterans in Mount Olivet Cemetery, visit our auxiliary website: mountolivetvets.org  The site features comprehensive memorial pages for WWI vets buried in the cemetery. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed