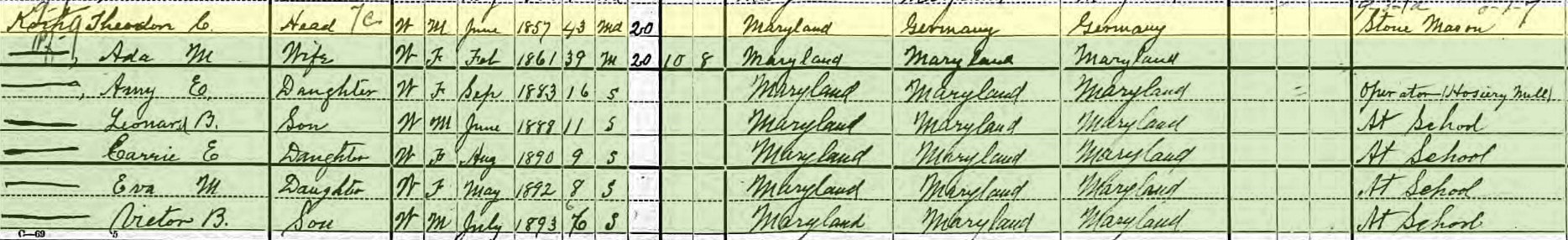

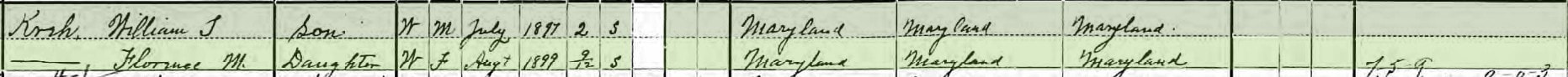

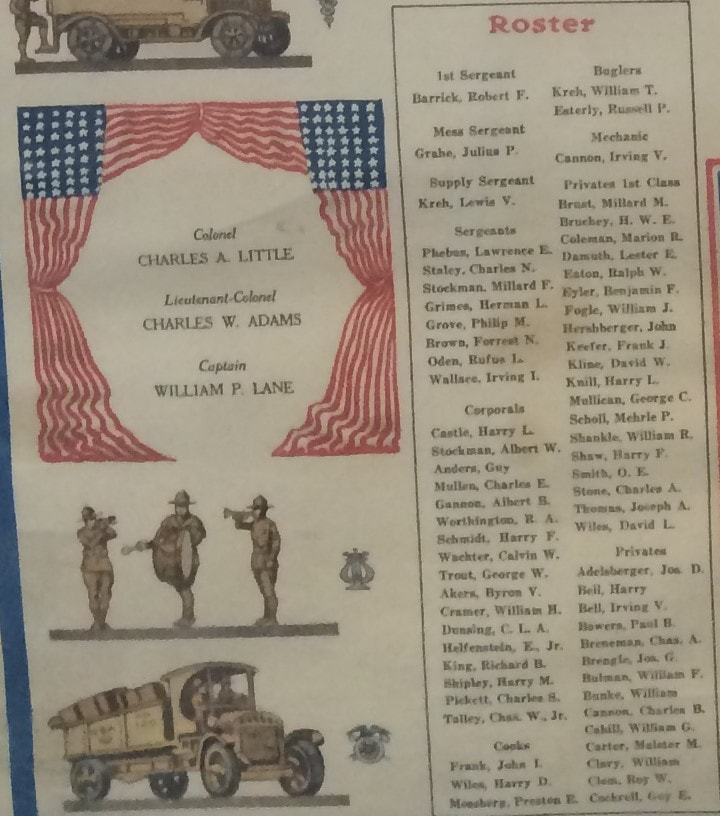

A scene from the motion picture 1917 A scene from the motion picture 1917 One of the hottest movies in theaters currently (at the time of this writing) is simply entitled 1917. We will continue to hear about this critically acclaimed work in coming months as it has already garnered Academy Award® consideration. The feature is an epic war film directed, co-written and produced by Sam Mendes and based in part on an account told to Mendes by his paternal grandfather, Alfred Mendes, a veteran of World War I. The movie chronicles the story of two young British soldiers during the war who are given a mission to deliver a message that warns of a suspected ambush during a skirmish, soon after the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line during Operation Alberich in 1917. The grave importance of message carrying in warfare cannot be understated. The common name applied to these brave souls was that of a “runner,” a soldier responsible for passing on messages between fronts during war. In the era before electronic communication innovations in warfare, battlefield administrators needed to share intelligence among one another in highly stressful, chaotic and rapidly changing situations. It was certainly a matter of life and death, as the lives of countless soldiers were at stake based on the safe transport of either questions or answers by the runner. Things could go horribly wrong with a lack of communication, a mistake, or an incorrect presumption made without the aid of military intelligence or observation. As can be easily imagined, this was a very dangerous job. The movie will certainly demonstrate this fact if you don’t believe me. World War I was dominated by trench warfare. With such, there was a tremendous need for runners. Passing messages between the trenches was not possible without climbing up to ground level and running towards the other trench. While on the ground, the soldier was hampered by weather conditions. The track was not ideal and full of obstacles, oftentimes forcing the soldier to sprint through smoke and chemical-weapon gasses, while on a muddy, or artillery riddled, track. Add to this the fact that runners were completely exposed to enemy sharpshooters, and it was commonplace for participants to die before reaching their destination. Officers could not be sure that a message had reached its recipient unless the runner managed to return. Last year was the anniversary of the end of the Great War, which prompted me to write stories on some of Mount Olivet Cemetery’s 500+ veterans of that conflict alone who are buried here. Many know that we have Charlotte Berry Winters here, who at the time of her death at age 109, was the last female veteran of the war to pass. We also have 13 soldiers who died during the war in active service. Some died in combat, and others due to the terrible Spanish Flu pandemic. One specific Frederick World War I vet, (today buried in our midst here in the cemetery) survived combat and the flu to return to the States and live a productive life. He was a bugler in the US Army’s Company A of the 115th Infantry Regiment, part of the famed 29th Division. Company A, started right here in Frederick. This gentleman’s name was William Theodore Kreh, Sr.—and he was a runner. Known by the nickname of “Whitey,” William Theodore Kreh Sr. was born on July 21st, 1897 in Frederick, the son of Theodore Christian Kreh and Ada Mae Stull. The family had 11 children and Mr. Kreh was an accomplished stone mason. The family lived at 239 W. 5th Street on Frederick’s south side at the time of William T.’s enlistment into service at the age of 20. He had joined the National Guard and was assigned to the 115th Regiment and Frederick’s Company A was based here in Frederick at the Armory located at the corner of Bentz and W. Second streets. As a matter of fact, the armory had been built in 1913, the third of a series of similar armories built for the Maryland National Guard in the early 20th century. Up until his time of deployment, he worked as a brushmaker at the Ox Fibre Brush Company.

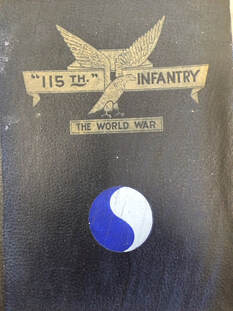

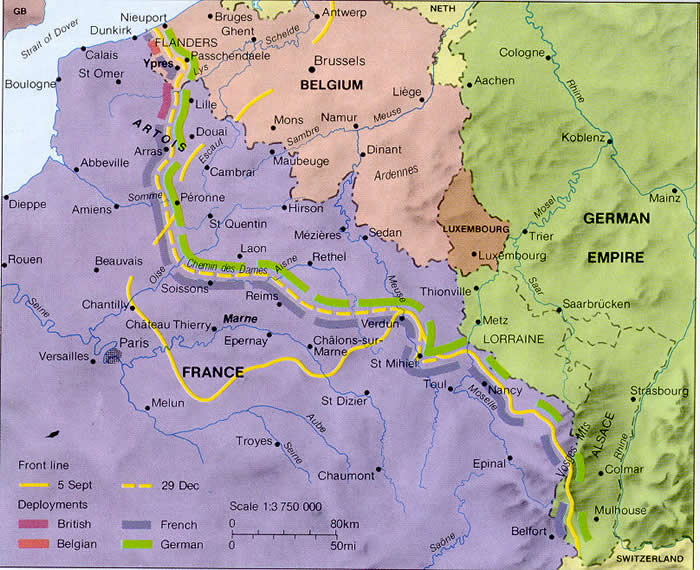

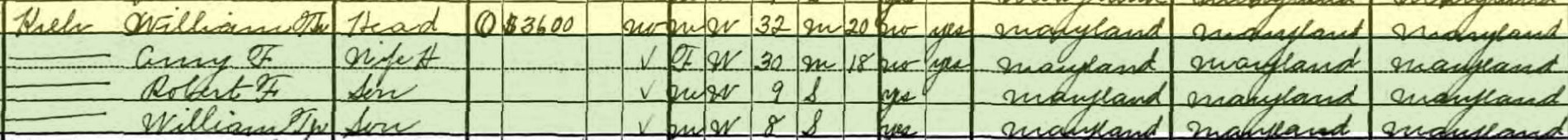

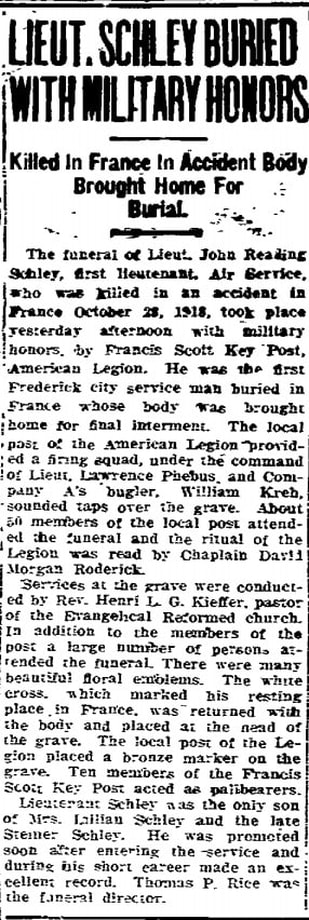

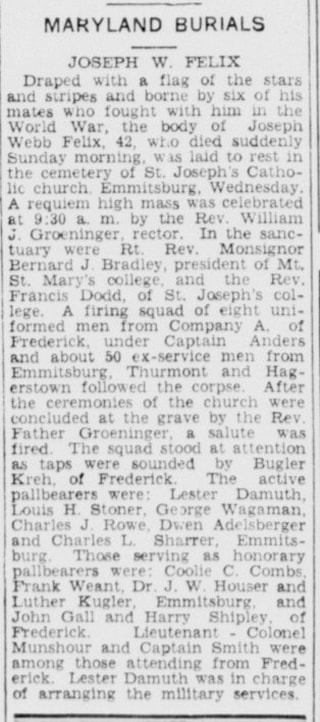

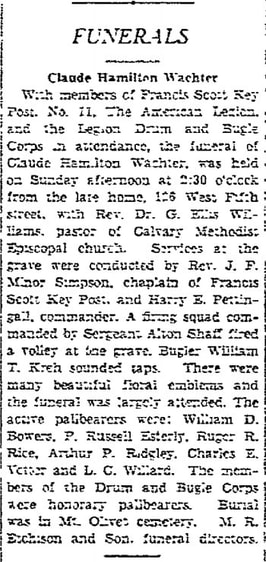

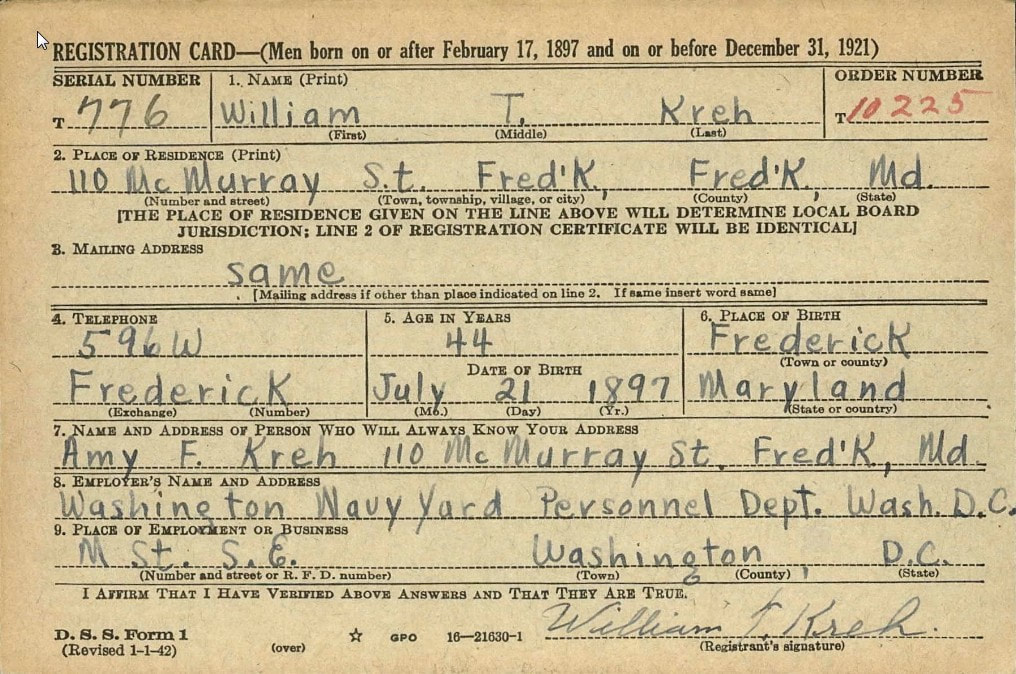

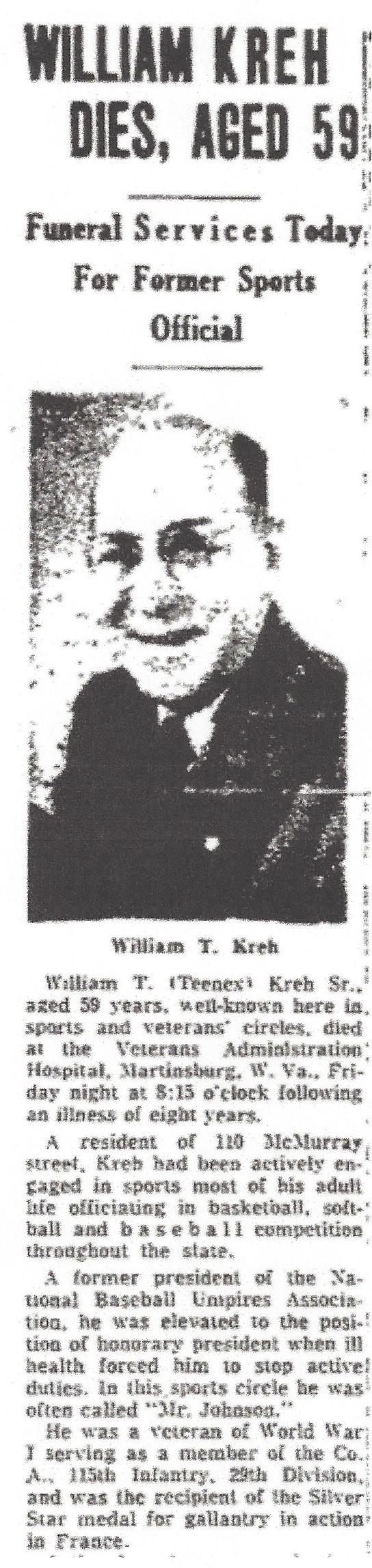

The following passage comes from the Regimental History of the 115th and paints a picture of what William T. Kreh experienced during his military service. Under command of Major General Charles G. Norton, the division was sent to Camp McClellan, near Anniston, Alabama, in August 1917. It spent ten months there in training before being shipped to France. On arrival at the front the division was given responsibility for a "quiet" sector on the German-Swiss border; its mission was to control the Belfort Gap. After two months in that position, the Blue and Gray division was sent north on September 22, 1918, to take part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The men of the division went "over the top" for the first time on October 8. In twenty-one consecutive days in the front line trenches they advanced six miles at a cost of 4,781 casualties, including 1,053 killed or died of wounds. The 29th sector was south of the Heights of the Meuse. The mission was to storm those heights attacking the entrenched positions of the Hindenberg Line with its pillboxes and machine gun nests. The division helped to take the Consenvoye Heights and the Borne de Cornouilles (Corned Willy Hill). On November 11, when the Armistice was declared, the 29th division was marching back to the line to join the Second (U.S.) Army's drive against the forts at Metz. William T. Kreh had recently married Amy Ford before making the trek to Alabama. Musical talents earned him a prestigious job as Company A’s bugler. This would put him in close proximity to the command element throughout the war. Like the runner, bugler was a hazardous position in any infantry unit—and often times one in the same. In addition to the standard Reveille and Taps calls, the bugler blurted out command signals for the troops during action. To do so required him to stand tall and play the instrument with great force so all could hear over the rattling of machine guns and the explosions of artillery shells. In doing this, he represented a perfect target for the enemy. Cutting off lines of communication in war was an essential objective for the enemy, and I’m sure William T. Kreh was well aware of this fact. On arrival at the front, the division was given responsibility for a "quiet" sector on the German-Swiss border with its mission to control the Belfort Gap. After two months in that position, the Blue and Gray Division was sent north to France on September 22nd, 1918, to relieve the soldiers on the frontlines northwest of Verdun taking part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The men of the division went "over the top" (of the trenches) for the first time on October 8th. In twenty-one consecutive days in the frontline trenches they advanced six miles at a cost of 4,781 casualties, including 1,053 killed or died of wounds. The 29th sector was south of the Heights of the Meuse. Up until the 8th of October, William T. Kreh and his colleagues of the 29th had been encamped in the Valley of the Meuse, waiting for orders to attack. Mustard gas created depression among the troops. Of all the death and destruction, the area of Molleville Farm would prove the bloodiest and fiercest. The locale was a key position in the German defenses during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The farm was attacked on October 8th, by the 29th, who finally took the woods around the farm over a week later on October 16th at a cost of 3,936 casualties. Several Frederick doughboys fought in a fierce and decisive battle, as this action would become a deciding turning point in World War I. Going across this land, the soldiers not only fought the Germans but also the horrible conditions of the trenches located so close that one could hear their enemies talking to each other. Other inhabitants of the trenches were rats and vermin.  Major D. John Markey Major D. John Markey William T. Kreh would be given an assignment at the Molleville Farm, one that would receive great praise from a fellow Fredericktonian, Major D. John Markey (1872-1963), commander of the 112th Machine Gun Battalion of the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment. He eventually took command of the 115th Regiment, and eventually rose to the rank of brigadier general, and served on the General Staff of the Army. In a letter written in January, 1919, Major Markey, an original founder of Frederick’s Company A, was quick to heap praise on the former unit he helped create. The letter was published in the February 21st, 1919 edition of the Frederick News: “Company A, 115th and the community can well be proud of the record they have made. One of their members, “Whitey” Kreh, a bugler of the company carried a message for me at the battle of Molleville Farm, an important message from the frontlines back to headquarters through an unusually heavy barrage.”  Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find much more on Kreh’s heroics at Molleville Farm on October 15th, however his action under fire would not go unnoticed by the top brass as they say. On November 11th, when the Armistice was declared, the 29th Division was marching back to the line to join the Second (U.S.) Army's drive against the forts at Metz. The Armistice put an end to the war—the Allies were victorious. Kreh and the men of Company A would return home that spring, and Kreh officially wrapped up his service with the 115th on May 24th, 1919, receiving his honorable discharge. William T. Kreh would receive the AEF Citation for Gallantry in Action for his role in delivering important messages through an intense bombardment. This award is more commonly referred to as the Silver Star. His citation, dated June 3, 1919, reads as follows: “By direction of the President, under the provisions of the act of Congress approved July 9, 1918 (Bul. No. 43, W.D., 1918), Bugler William T. Kreh (ASN: 1283806), United States Army, is cited by the Commanding General, American Expeditionary Forces, for gallantry in action and a silver star may be placed upon the ribbon of the Victory Medals awarded him. Bugler Kreh distinguished himself by gallantry in action while serving with Company A, 115th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division, American Expeditionary Forces, in action in the Verdun Sector, France, 15 October 1918, in delivering important messages through an intense bombardment. In doing some more research, I found that the bugler’s mission in World War I would be replaced in the coming years by more advanced communication equipment and procedures. Once back home in Frederick, William T. Kreh took up residence with wife Amy at 110 W. 5th Street. They would have two sons: Robert and William T. Kreh, Jr. By 1930, the Kreh family can be found living at 110 McMurray Street and William was still employed as a machinist and Ox Fibre. I saw several articles that show Kreh’s involvement in the local American Legion Post and was a charter member of Veterans of Foreign Wars, John R. Webb Post, No. 3285. In addition, it seemed commonplace for him to be regularly given the honor of performing as bugler for military holiday events and on veteran funeral details here at Mount Olivet and other local churches. By the year 1941, America was heading into a Second World War. William T. Kreh, Sr. was involved in the war effort again, this time as an employee working at the Washington Navy Yard within the Personnel Department. His obituary says that he was actively involved in local athletics, primarily officiating games—a perfect hobby for a former bugler. He even served as a former president of the National Baseball Umpires Association. Kreh became ill in the late 1940’s and would slowly become debilitated by this malady. He spent his final months at the Newton D. Baker Veterans Hospital in Martinsburg, WV, dying of a heart attack on November 30th, 1956. His death and obituary made the front page of the local paper. William T. Kreh is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area P/Lot 198. His wife Amy would pass in 1968. Other family members reside here too.

It's only fair to ponder the question: "Was Taps played at the former runner's funeral? And if so, who played the bugle?" ........................................................................It didn't take long to answer that question.

4 Comments

ROBERT F. KREH III

1/22/2020 06:53:34 pm

was an article on my grandfathers life i did not know alot about since son of veterans of all past world wars,and vietnam...Thanks....

Reply

Penny Kreh

3/24/2020 06:20:51 am

Robert Kreh. if you would email me or message me I would greatly appreciate it. I have been looking for years a cousin and his family. My cousin, Bob Kreh, Ii was the son of Robert Franklin Kreh, Sr. His (my Uncle's ) Parents were William T Kreh, Sr and Amy Ford Kreh. They had three sons, Robert (Bob) F. Kreh, William (Bill) Theodore Kreh, Jr. And Carson Ford Kreh. They lived in Frederick, MD.

Reply

4/27/2020 01:44:55 pm

Movies about the era of World War has always been an interest of mine. I cannot remember exactly when it started, but I have always been curious about the stories during World War that we were not taught in school. The recent film '1917', as you have mentioned, is one of the best films I have seen so far. The story revolves about a runner, a soldier who is responsible for delivering messages to other soldiers, who is faced with the pressure of relaying a message that could potentially save one thousand and six hundred lives. The movie puts you into a roller coaster of emotions and gives you a glimpse of the horror many soldiers face during war. It keeps you off the edge of your seat and leaves you a mind-blowing experience towards the end.

Maquita Sue

5/7/2020 12:56:34 pm

Great article. My father Bob Kreh (Robert Kreh, Jr.) did not share this one.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed