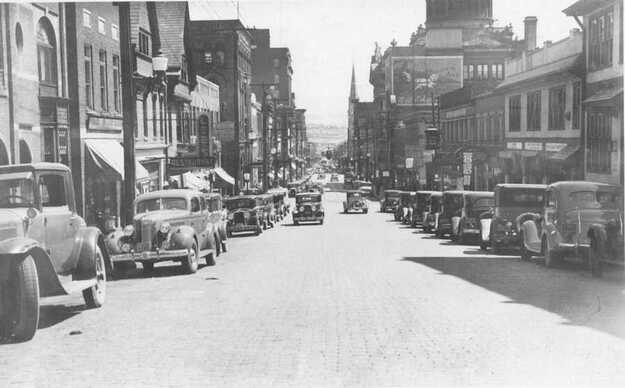

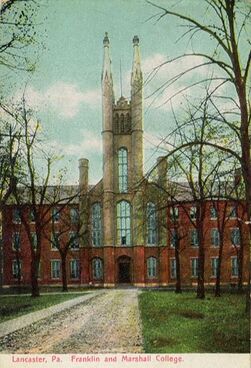

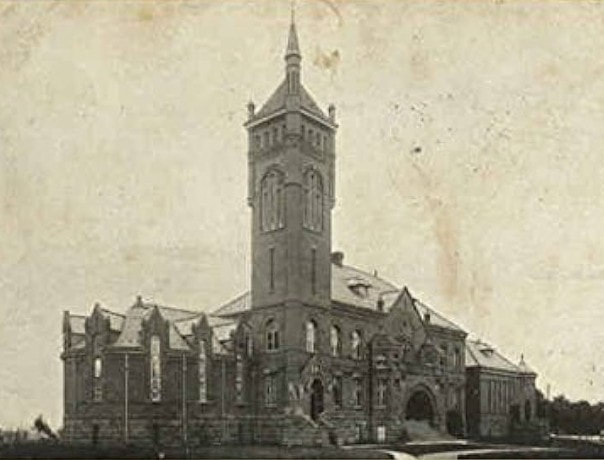

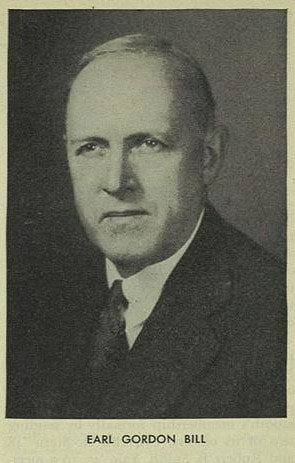

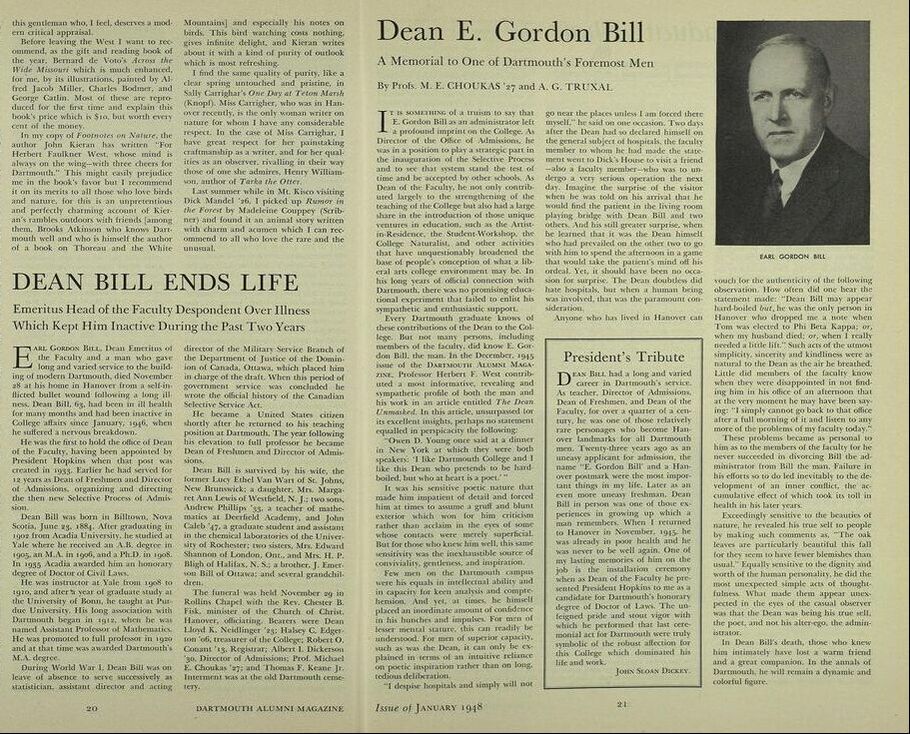

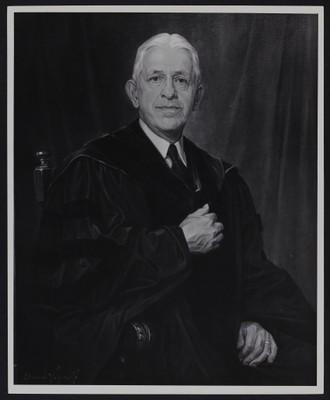

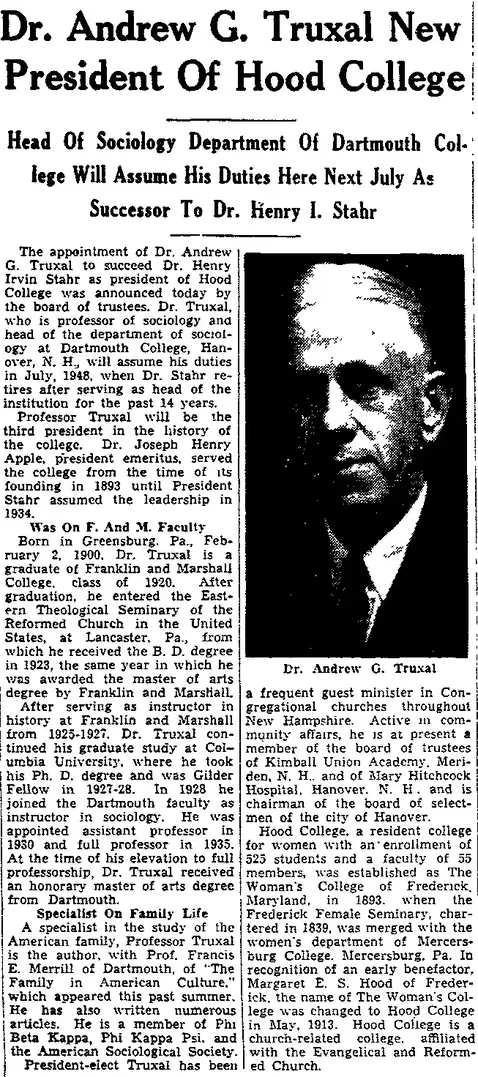

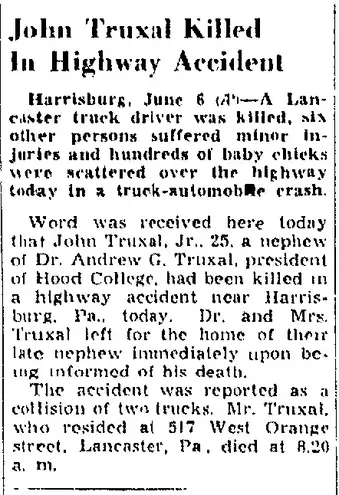

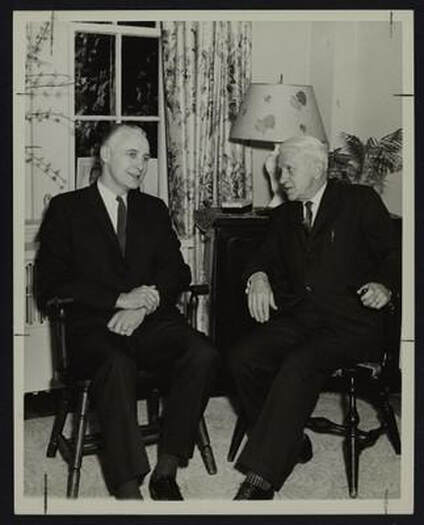

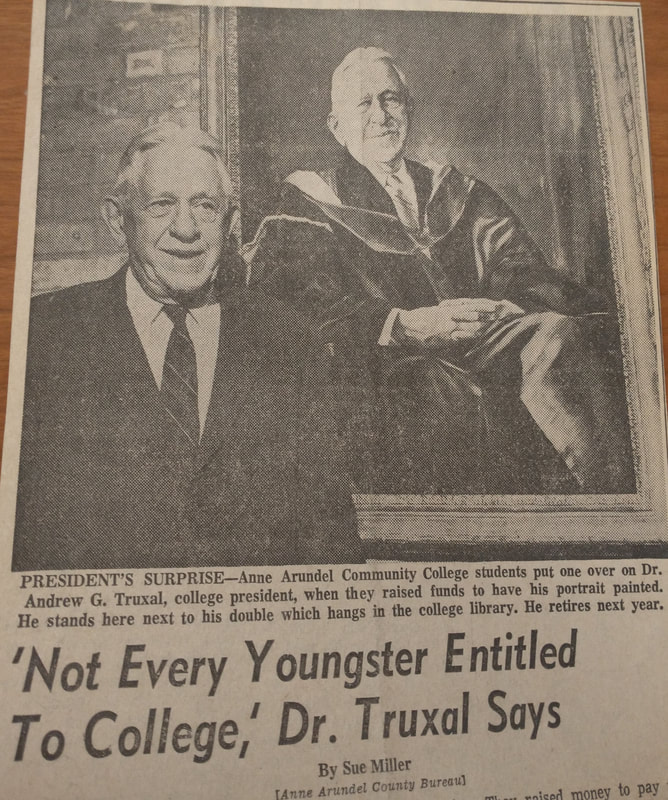

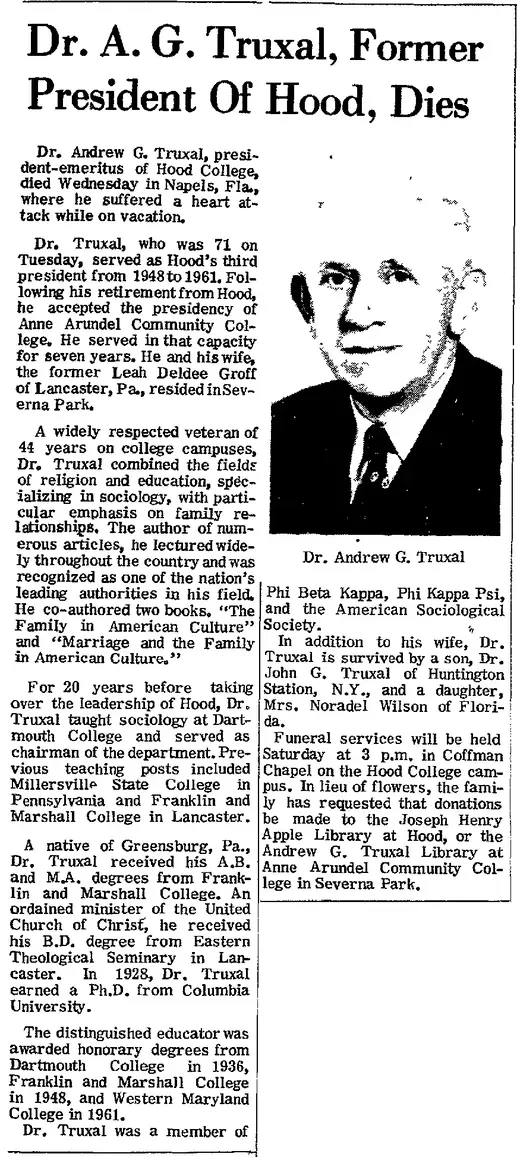

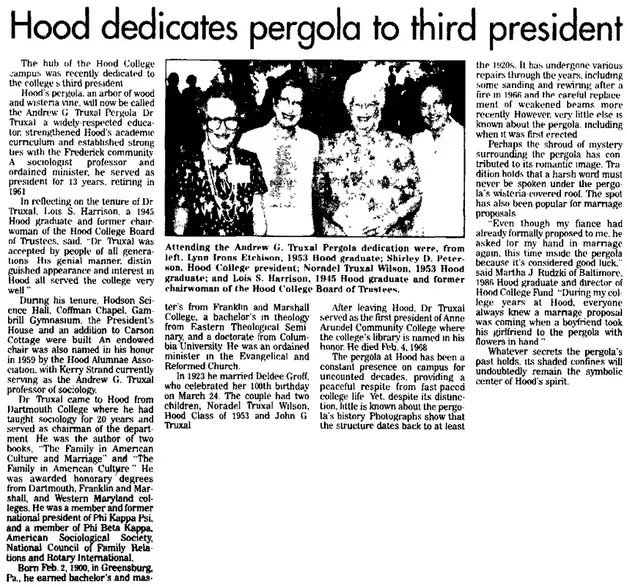

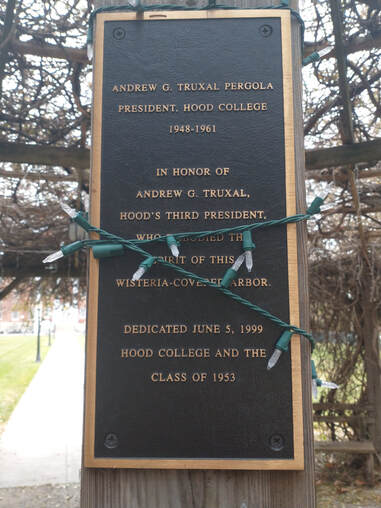

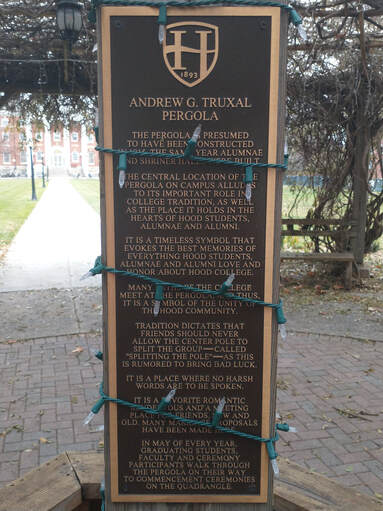

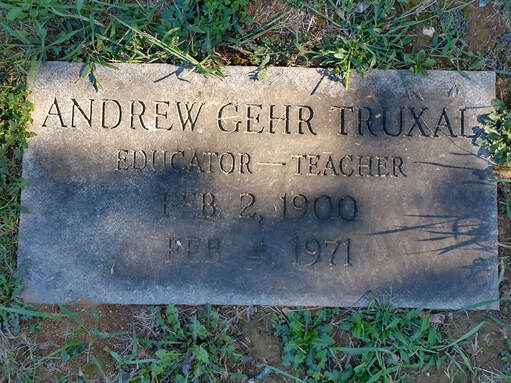

A German "turner" at work A German "turner" at work AUTHOR'S NOTE: The following "Story in Stone" was researched and written by Hood College senior Luke Jones as part of his internship with us here at Mount Olivet Cemetery (Fall Semester 2023). Here’s a question: How much have you thought about the design of your furniture, or a special woodcraft item? Chances are that you have not given it much thought once you bought it and put it in your home. Yet at the same time, many could not imagine their living space without intricately patterned wooden furniture or decorative objects. Plastic seats and toys do not invoke the same feeling of homeliness and completeness. The person to thank behind these designs in the woodwork is called a turner. A turner is one who works in woodturning, the craft of carving wood into various shapes and patterns using a lathe and handheld tools. Like a potter does with clay, a turner turns a seemingly ordinary piece of wood into something new and improved, connected to yet distinct from what it was before. Now, there are not any famous or revolutionary woodturners known to be buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery. But there is a “turner” interred here that did help craft materials into improved versions, and just like many turners, he has often been forgotten despite the great impact he had. I am referring to one Andrew G. Truxal (1900-1971), third president of Frederick’s famous Hood College as well as the first president of the renowned Anne Arundel Community College. Mr. Truxal fits the turner mold in two ways. “Truxal” is derived from a German word for “turner,” with the name having many variations including Troxel and Traxal. Like many surnames, people likely received it due to their professions as woodturners. Mr. Truxal was far removed from any woodturning ancestor, but he fit the term in a more metaphorical way. Just as a turner turns wood into something new and special, Mr. Truxal as an educator helped turn young minds to more knowledgeable and moral individuals. It is even more fitting for him specifically, as he was especially concerned with the character of his students, perhaps selectively so. Andrew Gehr Truxal was born on February 2, 1900, in Greensburg, Pennsylvania to Jacob Q. Truxal and Elizabeth S. Truxal (née Gehr). At the turn of the century, Greensburg, like much of the rest of the United States, was going through great changes as new technologies such as automobiles became more common and industries more expansive. Greensburg was continuing to grow from a small town to the largest city in Westmoreland County, spurred by the large coal mines nearby.  Map of Saarland within Germany Map of Saarland within Germany Andrew Truxal was part of a long lineage. Germans had been a key demographic in Pennsylvania since the foundation of the original colony by the Quaker William Penn. Their descendants, the Pennsylvania Dutch, continue to have social and cultural influence on the state and adjacent areas, and many Pennsylvanians state that they descend from Germans according to census data. It appears the Truxal family that led to Andrew first arrived in the mid-1700s with Johann Daniel Troxell or Trachsel (1725-1814), who was born in the Saarland in what is now Germany. Note how the surname changed over time, becoming more anglicized, likely the result of living near English-speaking colonists causing linguistic drift as well as perhaps a desire to fit in, or it could simply be a transcription mistake. Whatever the reason, the Truxal family remained remarkably sedentary, never leaving the region in and around Westmoreland County. Truxal family members witnessed many national events, such as the American Revolution and the Civil War; in fact, Jacob Dotterer Truxal, Andrew’s paternal great-great-grandfather, was a soldier in the Continental Army. For his part, Andrew was no exception to seeing conflict and crisis. During his youth, Andrew saw worldwide tensions boil over into the First World War, and during his adult years before Hood he saw the Great Depression and the Second World War. In fact, Andrew’s whole career would coincide with great changes in the United States and the world, and those changes provided context for his actions and beliefs. But that’s for later in this story. Going back to Andrew’s early years, there are few records of his childhood. He left no personal recollections outside the school records he wrote during his later duties as administrator. But by researching around him, a general picture can be constructed. He was the fifth child and third son of Jacob and Elizabeth Truxal, who were probably thankful for his survival; a previous child, Hazel, sadly died at only a year old. Unfortunately, that would not be the only untimely passing in the family. Two years after Andrew graduated from Greensburg High School in 1916, his older brother Jacob, Jr. was killed while serving in France during the First World War, and then eight years later his other older brother, Todd, died at the untimely age of 34, leaving Andrew as the eldest living Truxal son. In addition to mourning expected by the family, there was also undoubtedly pressure on the young Andrew to succeed as the primary heir of the Truxal name and legacy. It is possible these early deaths in the family pushed Andrew towards familial sociology and earnest Christian faith as an adult to seek understanding and comfort. Despite these tragedies, Andrew continued with his higher education. For a very brief moment, Andrew was drafted into the Army in the final months of World War I, but the war ended before he saw combat, sparing him from his brother's fate. Resuming his education, he obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree from the renowned Franklin and Marshall College in nearby Lancaster in 1920, specializing in sociology, or the study of human relationships and interpersonal functions, but also focusing on history, social statistics, and religion. He also joined Phi Kappa Psi, a noted national fraternity. Three years later, he received his Master of Arts degree from the same location, and that same year he completed his training at the Lancaster Theological Seminary of the Evangelical and Reformed Church, becoming an ordained minister of the titular church. In 1923, Andrew Truxal married Leah Deldee Groff. She was also a person of German descent in western Pennsylvania; she graduated from Goucher College in Baltimore in 1920 with a degree in mathematics, and she was a teacher from 1920 to 1923. How she met Andrew is unknown, though judging from the timing and background, it is likely they met in 1923 in Lancaster, though it is possible they knew each other earlier. While it may seem strange for a sociologist and a mathematician to fall in love, they were both interested in teaching. Combined with their shared ethnic background, Andrew and Leah were drawn to each other. They remained happily married and had two children, son John Groff and daughter Nora Deldee. The family’s long health and unity provided key support for Andrew Truxal when his other family members died. Above all else, Andrew Truxal was devoted to educational and moral teaching. According to a later piece for the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, a friend suggested getting into law, with the eventual goal of becoming a judge. By Dr. Truxal’s own words, “They happened to be in a political position to do just that!” But rather than accepting his friend’s ethically dubious aid and advice, Andrew Truxal wanted to do what he enjoyed (while also getting paid). This was the first indicator that above all else, Mr. Truxal was both passionate and serious about being an educator, something that would remain consistent throughout his life. No doubt his skills as a minister were not only useful for teaching but also partially explained why he liked teaching; from a certain perspective, spreading the word of Jesus Christ and instructing the next generation are similar in their overall goals and methods. Andrew Truxal entered the teaching profession in a familiar place, serving as an instructor of history and economics at Franklin and Marshall from 1923 to 1925. He then went to another institution, this time State Teachers College in Millersburg, Pennsylvania, again serving as an instructor of history during the summers of 1925, 1926, and 1927. He might as well have been eternally in school during the Twenties, either as a student or educator. It appears he missed the heights of the Roaring Twenties, though maybe the general prosperity of the period permitted this thorough education and career. It is also possible he pushed through due to the deaths of his older brothers; the legacy of the Truxal name was resting on his shoulders. Evidently, Andrew Truxal was on a roll, for he then went to Columbia University in New York for his Ph.D., which he had earned by 1928. Once that was achieved, he went to Dartmouth College, an Ivy League school in Hanover, New Hampshire. It was the farthest he had ever gone from his home county, and it would be the next major chapter in his life.  28 year-old Dr. Andrew Truxal joined the faculty at Dartmouth in 1928. He appeared to have no prior connections to the institution. Considering the prestigious nature of the college, it seems Dr. Truxal was invited there due to his credentials. It certainly was not for the salary; Truxal later admitted that out of all the options, Dartmouth was actually the least attractive option in terms of earnings, yet he chose it anyway. If so, it speaks highly of him as a learned educator; not everyone is appointed as instructor at an Ivy League school they have never attended for relatively low pay. For the next twenty years, Dr. Truxal was part of the Dartmouth faculty, and it was during this period he started to earn greater renown for his skills and dutifulness. Initially, he was a mere instructor in sociology, meaning he was only teaching students rather than participating in the administration. Though, he must have been happy to actually teach his most preferred subject for once. In an article for Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, written in 1957 while he was President of Hood College, Dr. Andrew Truxal described his experience as wonderful and even joyous. He wrote: "To begin with, the administration of Dartmouth was so enlightened that we faculty members had confidence that our pursuit of the truth, wherever it might lead, would meet with the staunchest support from the President. This dedication to the principles of academic freedom provided a climate in which it was a joy to work. Likewise, the President felt that a good faculty member should also be a good citizen and participate in civic affairs. This led, in my case, to a most rewarding experience in town government." While transcribed years later, this does imply that Dr. Truxal’s dedication to not only knowledge but also moral character started early on. He enjoyed Dartmouth because, according to him at least, it produced and exalted good people, rather than just sharing good information. He continues: "In the next place, the students were a highly selected group of young men and, with very few exceptions, if they were treated with the respect due them as persons, one received their respect in return. Finally, the emphasis of the institution was on teaching and not on research. Consequently, my associations were with colleagues whose primary objective was teaching rather than spending the best working hours of the day on research and then, in utter weariness, meeting classes." In essence, Dr. Andrew Truxal was describing a close-knit community, rather than a purely educational facility. Dartmouth was a second home to him. Considering his focus on familial social connections, as well as the tragedies of his youth, such an institution would have greatly appealed to Dr. Truxal, explaining why he remained for so long. Of course, Dr. Andrew Truxal did not remain a mere instructor for twenty years; very few people could hold such a relatively minor position for that long. He quickly rose through the ranks of the Sociology department, becoming an Assistant Professor in 1930, before rising to become a full Professor of Sociology in 1935, being named the Chairman of the Sociology Department at Dartmouth and becoming more entwined with the faculty and administration. He held special courses on family and public welfare, fitting for a man of his interests. He also earned an honorary degree from Dartmouth in 1936. Dr. Truxal became a prolific figure at Dartmouth. By this time, he had joined the American Sociological Society, which was not so surprising. What is more surprising is that in 1940 he became a Selectman of Hanover, which was essentially a local government member in New England towns. In a way, the idea of joining the government first posited years before came to fruition, though in a different way than anybody expected. It was somewhat ironic, for he himself admitted if often referred to administration as “The Ad Building” in less-than-complimentary terms. Considering his focus on character as well as knowledge, it is possible that Dr. Truxal disliked the politics behind the scenes that interfered with his work. Yet ironically, administrative duties would become what Dr. Truxal was most renowned for. One person, recommending Dr. Truxal for Hood College, even said, “Dr. Truxal has served Dartmouth in every possible capacity except as President.”  The same year he became a Selectman, Dr. Truxal also became President of Phi Kappa Psi, which he held until 1942. This man kept finding positions of authority, despite his interests in just teaching! By 1948, he had additionally finished his book, The Family in American Culture, which was one of the very few books he wrote throughout his life, though he had also written various articles, including at least one at Dartmouth concerning interstate migration. By the end of Dr. Truxal’s time at Dartmouth, the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, along with other sources, noted, “He [was] recognized as one of the country's leading authorities in this field.” Renowned for his lectures on sociology and Christianity, it seemed he would have been happy to remain at Dartmouth for the rest of his life. Popular with faculty and students, Dr. Truxal certainly achieved his dream of improving others’ character, as well as his own. Dr. Truxal also served on various committees at Dartmouth, and not always under great circumstances. One committee was the Special Committee on Academic Adjustments, which handled academic opportunities for veterans. Dr. Truxal had an ever so brief experience in this realm, but was perhaps inspired by his long-deceased brother? Then in 1946, Dean Earl Gordon Bill became unable to do his duties due to a longtime illness, so Dr. Truxal, along with Bancroft H. Brown and W. Stuart Messer, became part of a triumvirate committee that directed the Office of the Dean of the Faculty in Bill’s absence. Sadly, Bill took his own life in November 1947 due to the pain of his illness, after he had retired. Dr. Truxal and his compatriots had to remain in their special committee until a new Dean could be found. Dr. Truxal co-authored a piece with fellow professor Michael E. Choukas that celebrated the Dean’s life. What Dartmouth did not know was that Dr. Truxal would soon leave them, too, though fortunately for much more optimistic reasons. In 1948, Henry I. Stahr, the second President of Hood College, resigned from his post. In anticipation, the Hood administrators called upon Dr. Andrew Truxal as the new potential leader of the Frederick institution. The nearly fifty year-old professor, with his years of experience in both teaching and administration, was a natural choice from a practical standpoint. But there were other probable reasons for Dr. Truxal’s appointment. Truxal was not only from Pennsylvania, a place relatively near to Frederick, but he also was part of the same Christian sect (German Reformed Synod) that Hood founder Dr. Joseph Henry Apple hailed from. There is no solid proof that Dr. Truxal and Dr. Apple knew each other personally, but at the very least, they must have been aware of each other considering how prolific both were within the Reformed Church and its descendant congregations. (The Reformed Church went through several mergers throughout the twentieth century, eventually leading to the modern United Church of Christ.) In a sad coincidence, Dr. Apple died the same year Dr. Truxal became Hood President, preventing them from forming a deeper relationship. In any case, Dr. Truxal’s similarities to Dr. Apple made the former an appealing choice. Yet, there were perhaps even more reasons for Dr. Truxal’s appointment. In several respects, Dr. Truxal could be considered conservative, a trait which would become more prominent in later years. His focus on moral character as well as knowledge, and his staunch Christianity, was the same as many conservative figures during the period after World War II. Implicitly, the Hood board wanted someone to maintain traditional values during this time of change and uncertainty. It is noteworthy that most of Dr. Truxal’s tenure occurred in the 1950s, famously known as conservative decade, and he left in the early 1960s, just as social changes began to sweep the nation. In essence, Mr. Truxal was a bastion against changing times. Whatever the reasons, Dr. Andrew Truxal became the third President of Hood College in July 1948, beginning a tenure that lasted for over a decade. Truxal and his family moved from the familiarity of Hanover to the new locale of Frederick, in a way returning to their German heritage. The occasion was celebrated by the newspapers, and many were excited to see how the renowned professor would elevate the Frederick institution. According to local newspapers, approximately 1500 people attended Dr. Truxal’s inauguration, including the presidents of John Hopkins University, Franklin and Marshall College, and Dartmouth as well as leaders of the Evangelical and Reformed Church to which Dr. Truxal belonged. In addition, the event also featured Maryland Governor William Preston Lane and numerous student leaders. Dr. Truxal's father Jacob also came to congratulate his son. In his speech, Dr. Truxal reiterated the values he had held as a teacher, saying: "We have been entirely too content with the mere training of the intellect. The only kind of education that will be at all adequate for the world of tomorrow must be an education which gives equal emphasis to the training of intellect and to the development of character." After the excitement of the inauguration, however, the hard work began. While Dr. Truxal had held positions of power before, he had never had such a high and powerful job before; even his two years as Phi Kappa Psi President could not prepare for what ended up being over a decade in college administration. No longer was he just a teacher, he was a leader. The first years were not particularly happy ones for Dr. Truxal, at least on a personal level, for he faced several family tragedies once again. In 1950, his nephew died (John) in an accident, causing Mr. and Mrs. Truxal to leave the campus to deal with the situation. A year later, his father Jacob Quimby Truxal passed away, undoubtedly saddening Dr. Truxal even more. Now he was the immediate Truxal patriarch, putting more pressure onto the new Hood President. But in more positive news, President Truxal was happy to announce that his daughter was getting married to Randolph G. Wilson in 1953. Whatever he faced, the ups and downs of his personal life did not impede his duties as Hood President. President Andrew Truxal’s tenure at Hood College was a period of stability and growth. He sought to expand the college, as despite several decades of growth from its humble beginnings, it was still a relatively small campus in terms of attendance and space. Starting in 1955, Hood built multiple new structures, including Hodson Science Hall, Smith Hall, the Thomas Annex in the Apple Library (which later became the Joseph Henry Apple Academic Resource Center), and perhaps most excitingly for Dr. Truxal, Coffman Chapel. These buildings still stand today and perform important functions for the Hood community. Of course, these large building projects required large amounts of funds. He also wanted to connect alumni with the current student body, the latter of which he also sought to enlarge. To kill two birds with one stone, President Truxal started the “Hood Forward” and “Hood Looks Ahead” programs. These initiatives sought out alumni and other associates to ask for donations and contributions to improve Hood. The "Hood Forward" program occurred early in Truxal’s tenure, while the "Looks Ahead" program occurred in his final years at Hood. Both were immensely successful and reflected Truxal’s dedication to social bonds and relationships. The "Looks Ahead" program made around $700,000 thousand dollars; in today’s money, that’s over seven million dollars! Part of those funds went to the Andrew G. Truxal Chair of Economics and Sociology, which was named in the president’s honor and to acknowledge his career as a sociologist. Truxal was also successful in increasing the size of the student body, which grew into the thousands. Hood College’s renown increased throughout Truxal’s tenure, and many notable individuals came to the campus. The President of John Hopkins and the Maryland Governor were already impressive clientele, but 1951 saw a visit by famous general and statesman George Marshall, the namesake for the Marshall Plan that helped rebuild Europe after the Second World War. Truxal had the honor of hosting and shaking hands with Marshall, perhaps a highlight of his long career. About nine years later, Truxal had the second honor of hosting Senator John F. Kennedy himself during his presidential campaign. Meanwhile, President Truxal led Hood through turbulent times. The Cold War began in earnest just as Truxal took his position, and fears, sometimes justified, many times unfounded, permeated the nation, and Frederick was no exception. At the same time, the 1950s were known for their image of post-war happiness and stability, and Truxal, while generally avoiding politics, did seem to thrive in that environment. President Truxal performed numerous sermons and talks at the Chapel in addition to his presidential duties, talking about Christianity’s place in the changing world. He brought not only his skills as a teacher and sociologist but also as a minister to the Hood presidency, focusing all his qualities to bring his own style and values to Hood College. Under his tutelage, Hood fully transitioned from an educational facility to an engaging and productive community, where the character of the students mattered just as much as their knowledge. This spirit still remains today, with the stated goals of Hood matching the ideals of Truxal from so long ago. President Andrew Truxal found the most success during the conservative 1950s. But by the end of the decade, society started to shift. The Cold War was heating up and had no end in sight, and the United States was starting to face a reckoning of its bigoted past and present as civil rights movements began to gain steam. A new generation of youth, born during and after the Second World War, had far different ideas from their parents and wished to take the country in a new direction. President Truxal, now sixty, saw the shifting tide, and in a sign of wisdom and acceptance, declared in 1960 that he would resign by July next year. Explaining his decision, he declared that he thought it was “wise to hand over administration of the college to a younger leader.” He would be greatly missed by both students and faculty. His successor was Randle Elliott, a political scientist, and Truxal greeted him as he took up his new post. However, that did not mean Dr. Truxal was done with administration. By his own admission, he wanted to retire, having spent his whole adult life in education. But as Hood was growing, another nearby school was being conceptualized and established called Anne Arundel Community College. By coincidence, Anne Arundel Community College was founded the same time Dr. Truxal decided to resign. By this point, Andrew Truxal had become renowned throughout Maryland and the country. The leaders of Anne Arundel considered Dr. Truxal to be ideal for the first president of the college, and they offered him the position when Dr. Truxal decided to leave Hood. Despite his original intentions, Dr. Truxal accepted, becoming President Truxal once again at Anne Arundel in 1961. President Truxal had the new challenge of building up an entirely new school, rather than joining an established institution. From 1961 to 1968, Truxal guided the faculty and students through those first awkward years every school goes through. His most impressive achievement was maintaining and growing Anne Arundel Community College, moving into its own campus and receiving full accreditation, having originally been at Severna Park High School with nightly classes. As these things were achieved, giving the college a stable future, Dr. Truxal decided to retire, this time for good. Before he left, the students honored him by voting to name the college library after him, in a way paralleling the Apple Library at Hood. The Andrew G. Truxal Library still stands today as a marker of his legacy. That was not to say Truxal’s tenure at Anne Arundel was without any controversy. In 1967, Dr. Truxal stated, “Not every youngster is entitled to college.” He explained that since college was improving character as well as imparting knowledge, students need to be the best they can be so they can eventually lead society. This meant that some individuals were not “fit” for college and that such people should pursue other careers. He also stated that an imbalance in student commitment and capabilities made it “impossible for a professor to teach.” Being an educator for over forty years, Dr. Truxal had definitely seen many types of students. Perhaps he was venting some long-simmering frustrations? In any case, it was somewhat ironic or even hypocritical for Dr. Truxal to have such views. Anne Arundel, being a community college, was designed to be more accessible than someplace like Hood or Dartmouth. Additionally, equal opportunity for education is dearly held by many, and only became more popular during Truxal’s time. Even the press notes that this is an unpopular opinion from a respected man. Maybe the aging Truxal was starting to lose touch with the students he cherished, convincing him to retire for good. Dr. Andrew Truxal fully retired in 1968 and moved to Florida with his wife Leah Deldee. After decades of learning and teaching, he had earned a deserved rest. While he had vague ideas about continuing to write, Truxal spent his last days in quiet peace. Unfortunately, he would not get long to enjoy the leisure. On February 3, 1971, just one day after his birthday, Andrew Truxal suffered a heart attack and passed away. President Tuxal's body was brought back to Maryland, and his funeral service was held at Hood College, the place he helped grow, permanently tying him and his legacy to the institution. All who wrote about him noted he was an accomplished and respectable man, dedicated to the personal improvement of his students, whether as a professor or a president. He was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Area FF, Lot 306. Leah Deldee lived for decades in Frederick after her husband’s passing, participating as an honored guest for many Hood events. She died in 2001 at the age of 101, being buried beside her husband. the Truxals' son, John G. Truxal, became a respected professor in his own right, going to M.I.T. and specializing in electrical engineering. Andrew Gehr Truxal left an impressive legacy, even if his name is little spoken today at Dartmouth, Hood, or Anne Arundel Community College. The latter two colleges are among the most renowned higher education institutions in the state of Maryland, with Anne Arundel being rated as one the best community colleges in the United States for the past several years. Anne Arundel also has a “Dr. Truxal Award,” celebrating students for achievements on both the sports field and in the classroom. In 1991, the Hood student body dedicated the pergola at the center of campus in Truxal’s name. A beautiful piece of work, the pergola symbolizes the unity of the Hood community, a place where bonds are created and enhanced. It has even been the site of more than a few wedding proposals. Hood legends state that friends should not “split the poles'” or else risk bringing bad luck. Andrew Truxal would have been proud. In his own way, Andrew Truxal was a turner, improving the character of his students, whether he was a teacher, writer, or administrator. Like a woodturner, his influence may not be obvious, but he forms a fundamental part of the local legacy and image. Through all his tribulations, Andrew Gehr Truxal truly lived up to his family name.

Special thanks to Mary Atwell, Archivist at the Hood College Archives, for her assistance with this article.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed