|

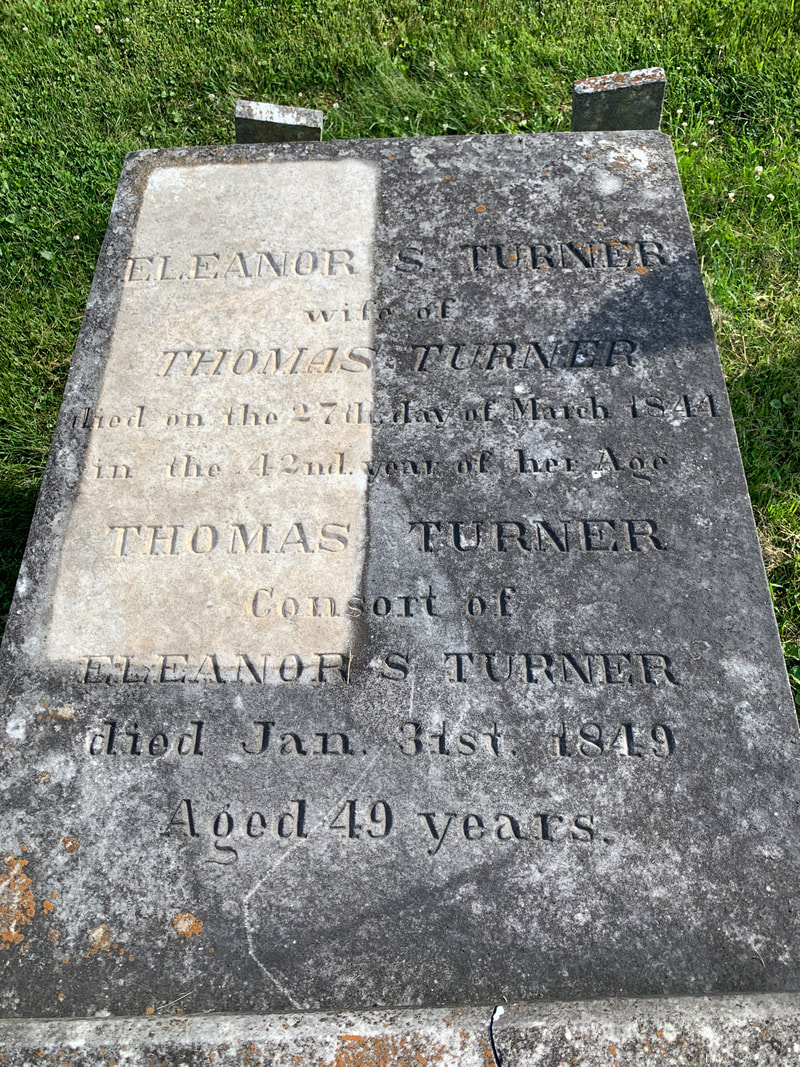

I came across a very odd sight in the cemetery while conducting a tour a few weeks ago for a throng of middle-schoolers attending a history camp. No need to brace yourself, as it has nothing to do with anything disturbing or macabre. Rather, it was simply a discoloration of a section of a ledger-style gravestone. Or should I say, it can be better described as a rare preservation of a portion of a ledger gravestone. The history session immediately turned into a science lab in which I was describing why this lasting memorial to Eleanor S. (Pratt) Turner (1842-1844) and her consort, Thomas Turner (1799-1849), had a big, white rectangle on its face. I had to stop my presentation and think a minute, but the answer was crystal clear—It was all about aging and exposure to outside elements. Although old age does a number on all gravestones (as it does most decedents), the Maryland climate with four seasons also plays a major factor on our memorials. Blame this on such things as algae, lichen, moss, mold, or mildew growth and stains. These growths develop on the surface, making headstones look dark, dirty, and downright creepy. Most grave monuments sit outside naturally, and are constantly subjected to moist, humid conditions. Unfortunately, these situations promote unsightly growths to take hold and grow. This is especially true in the southern part of the country where high humidity is common.

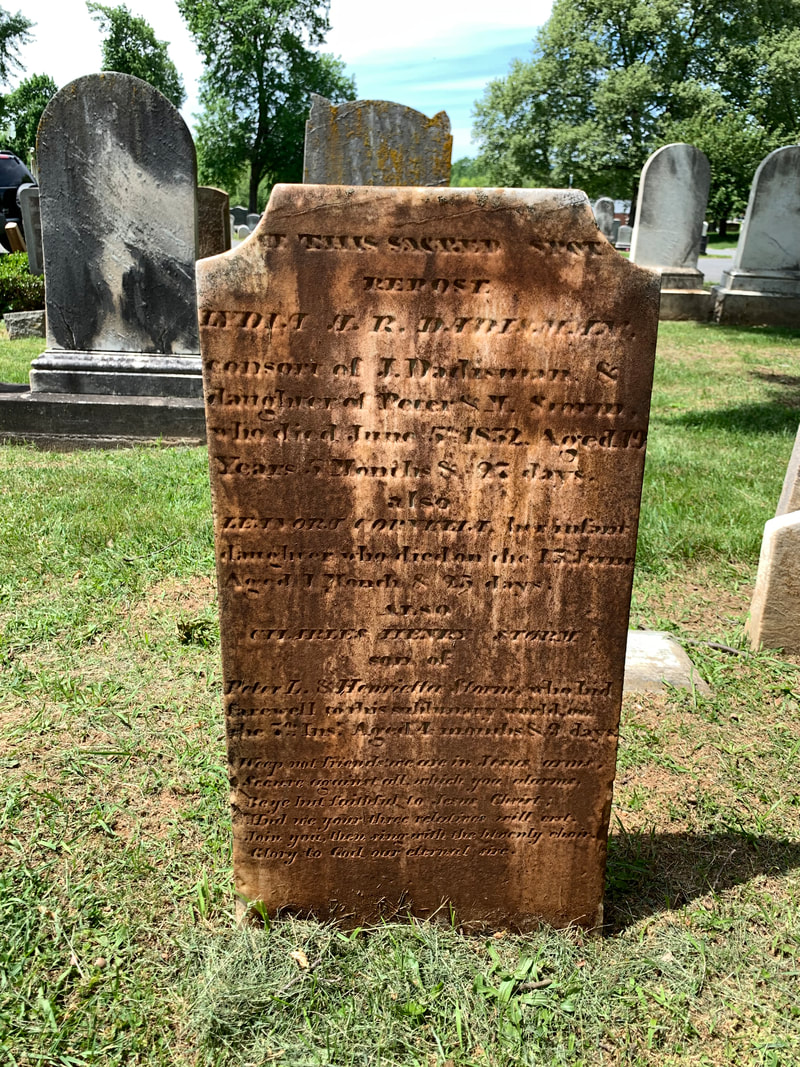

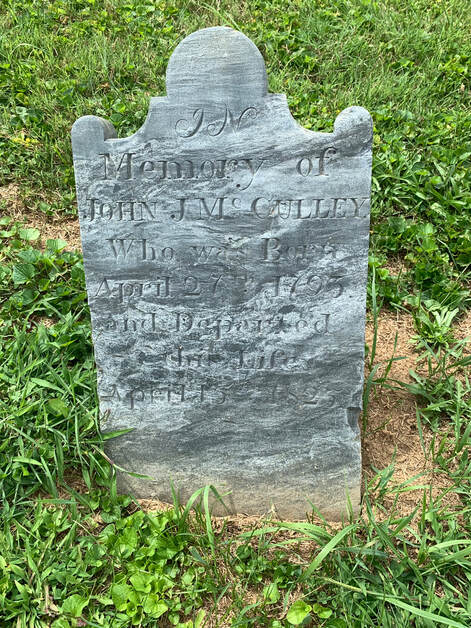

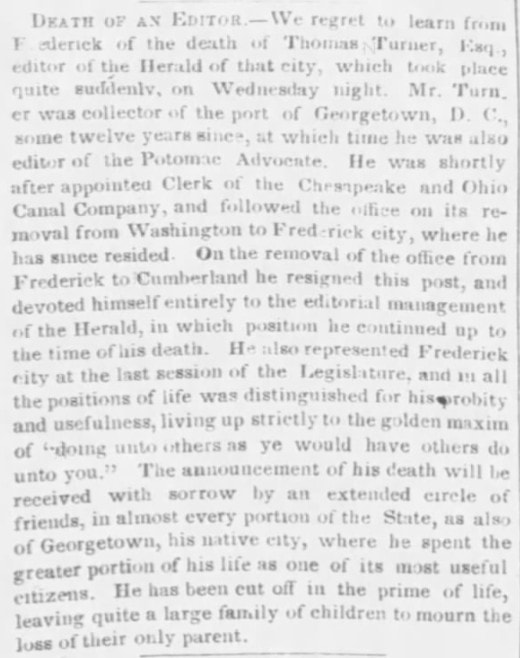

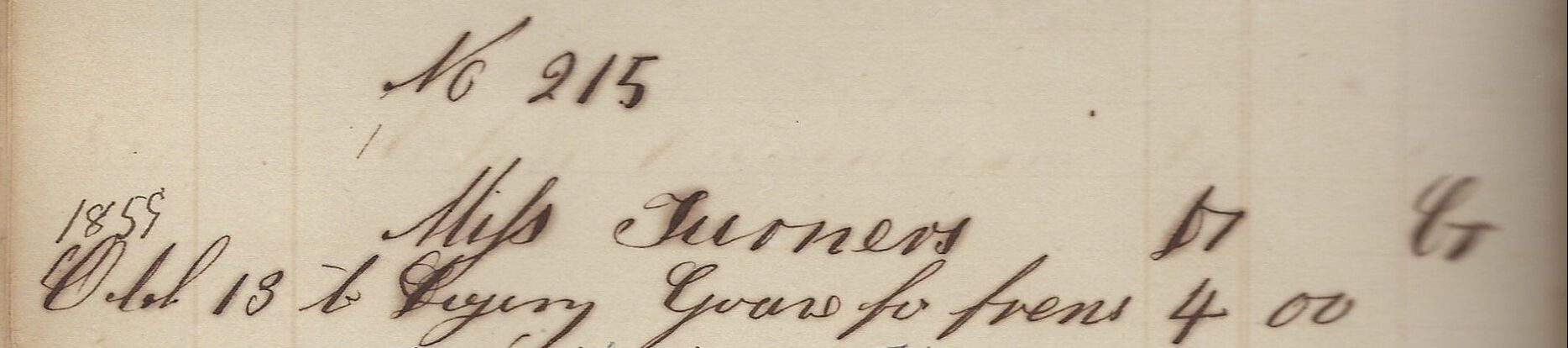

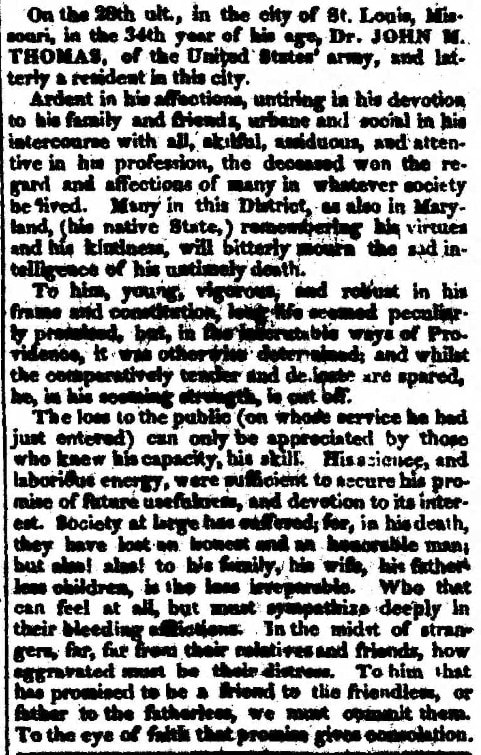

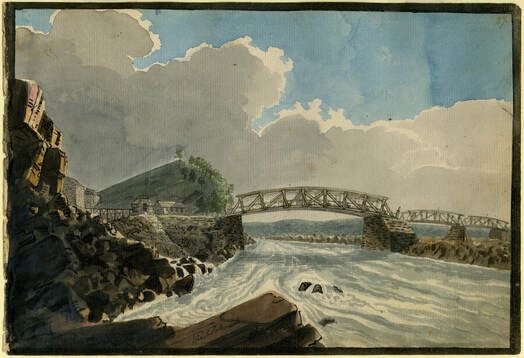

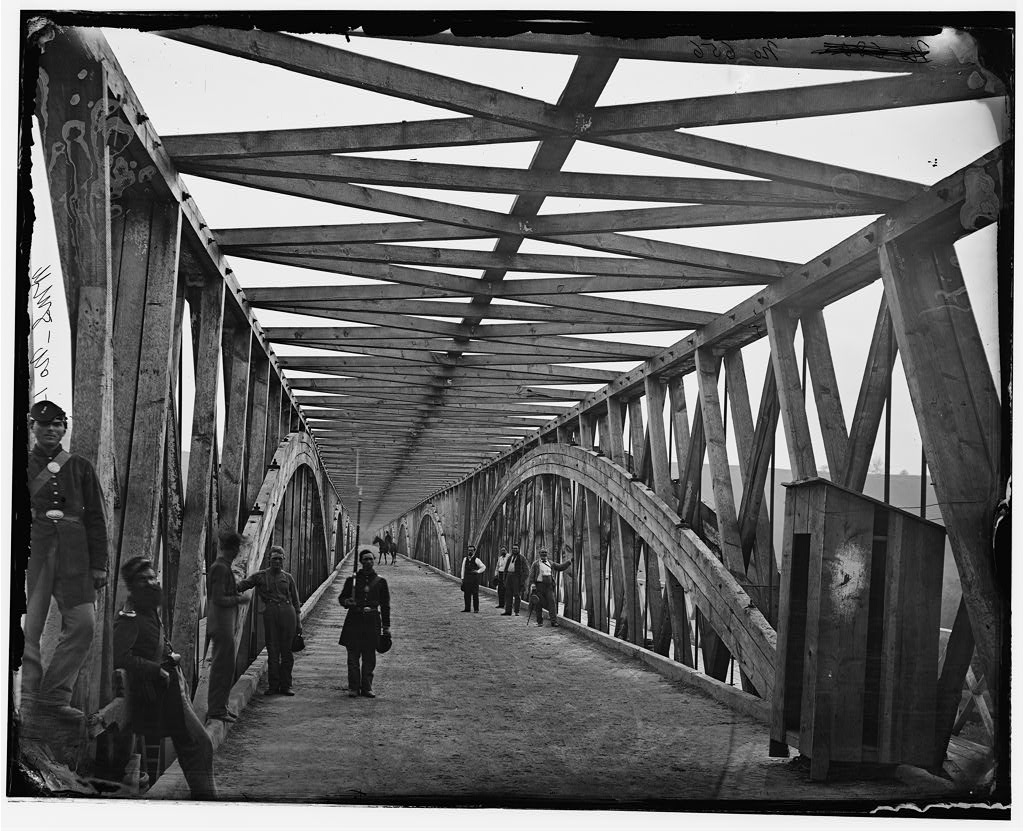

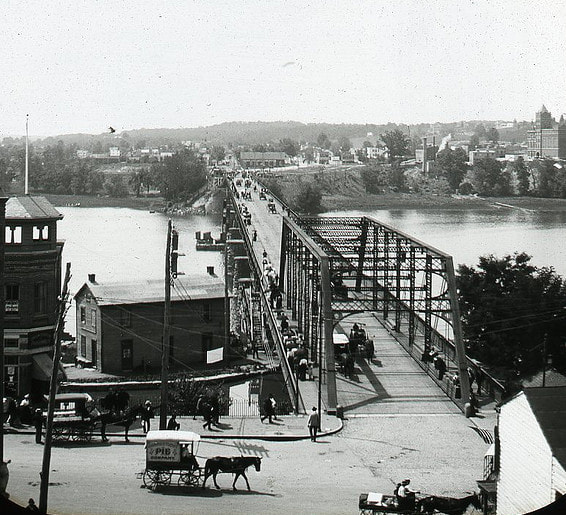

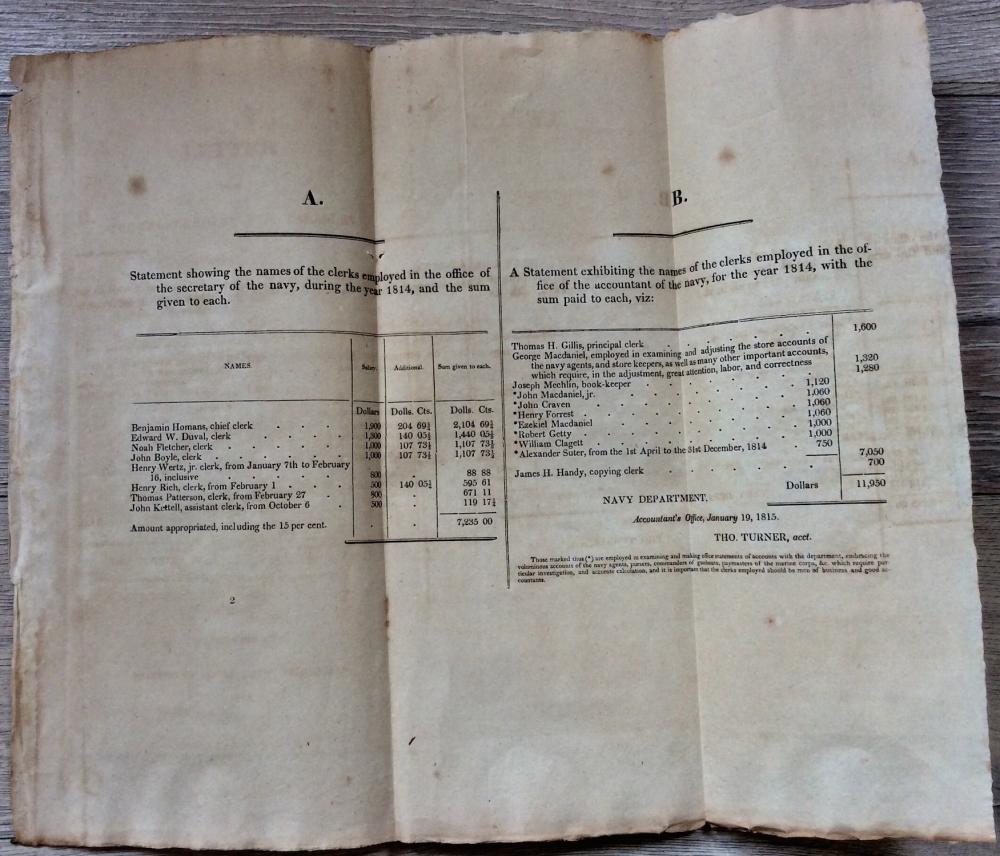

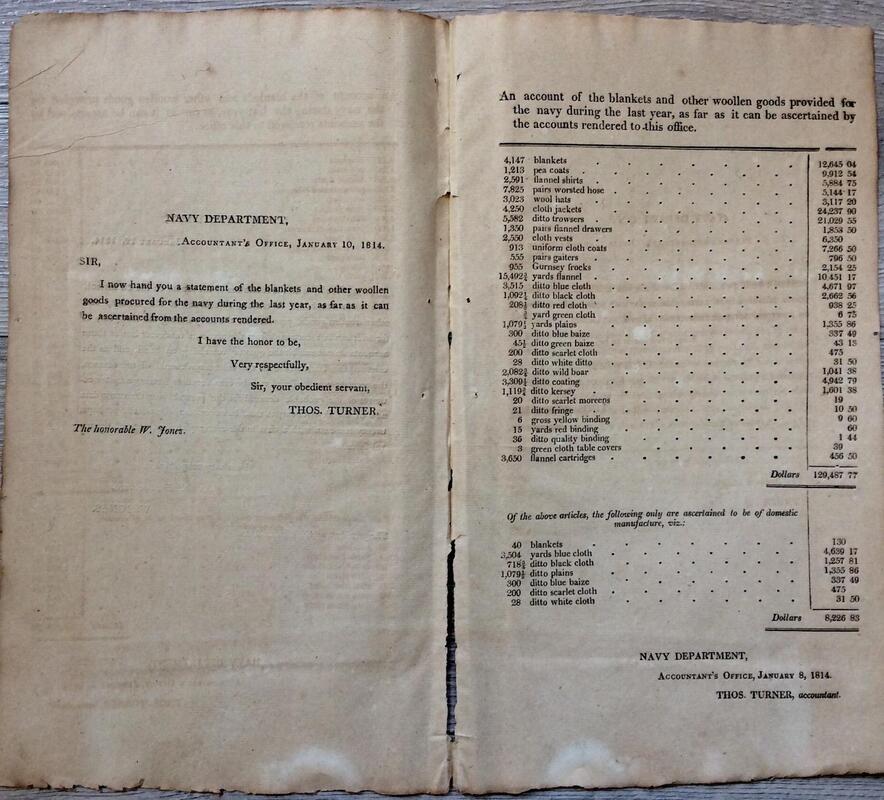

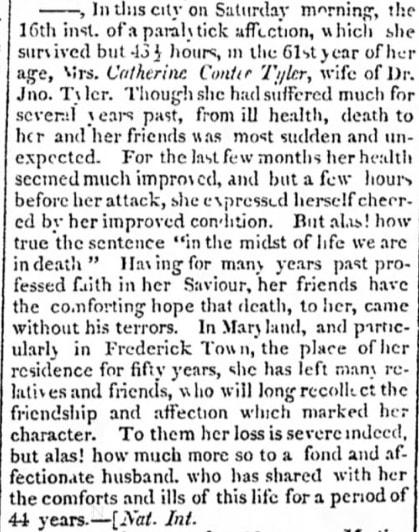

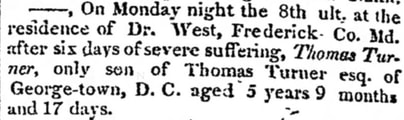

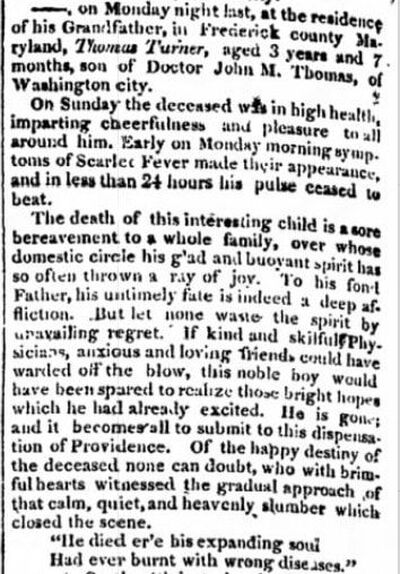

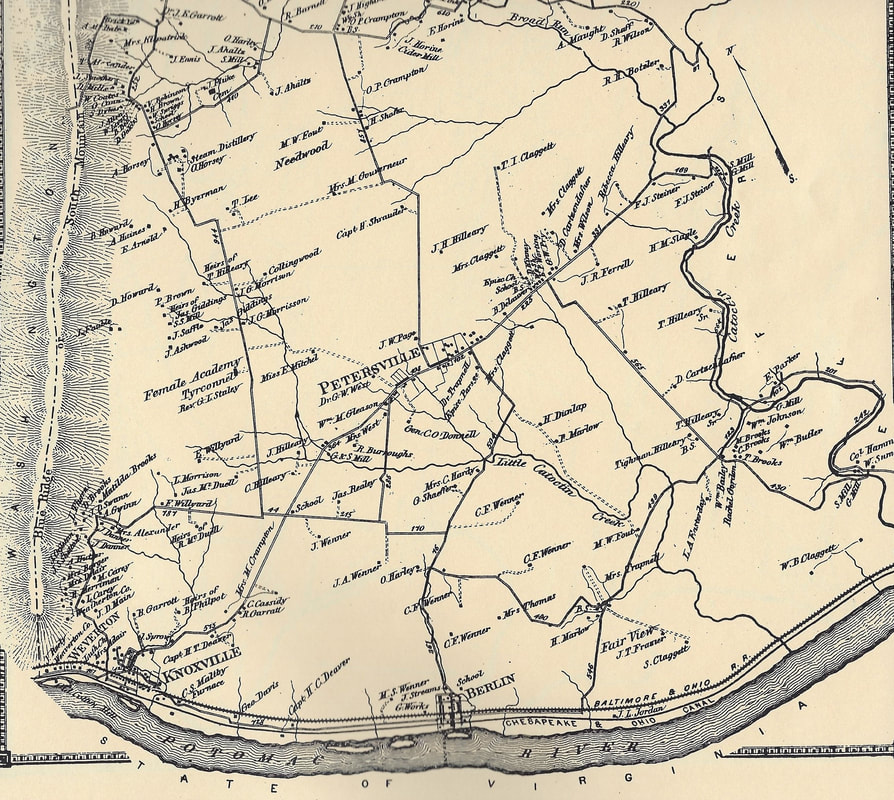

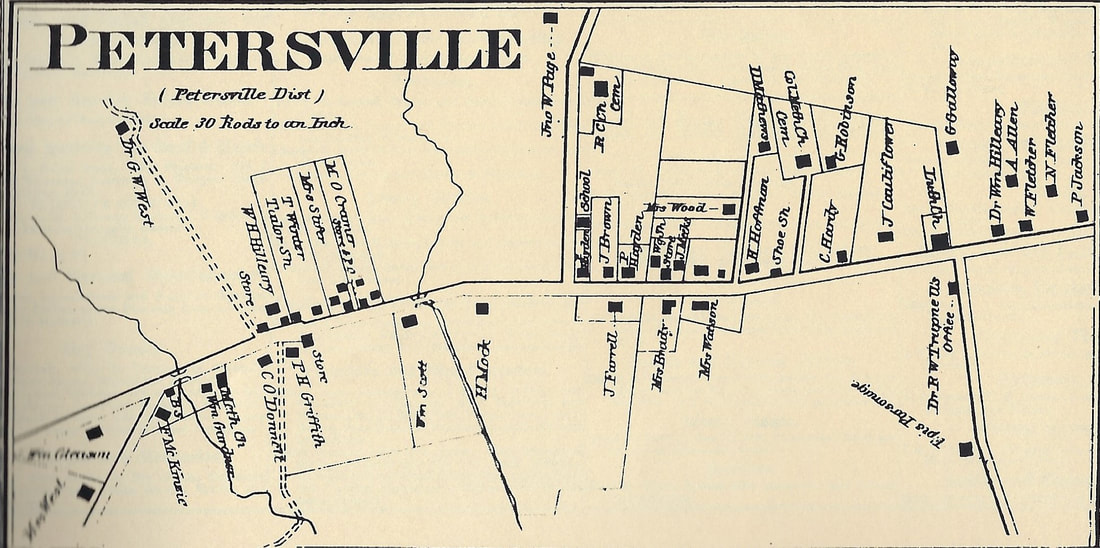

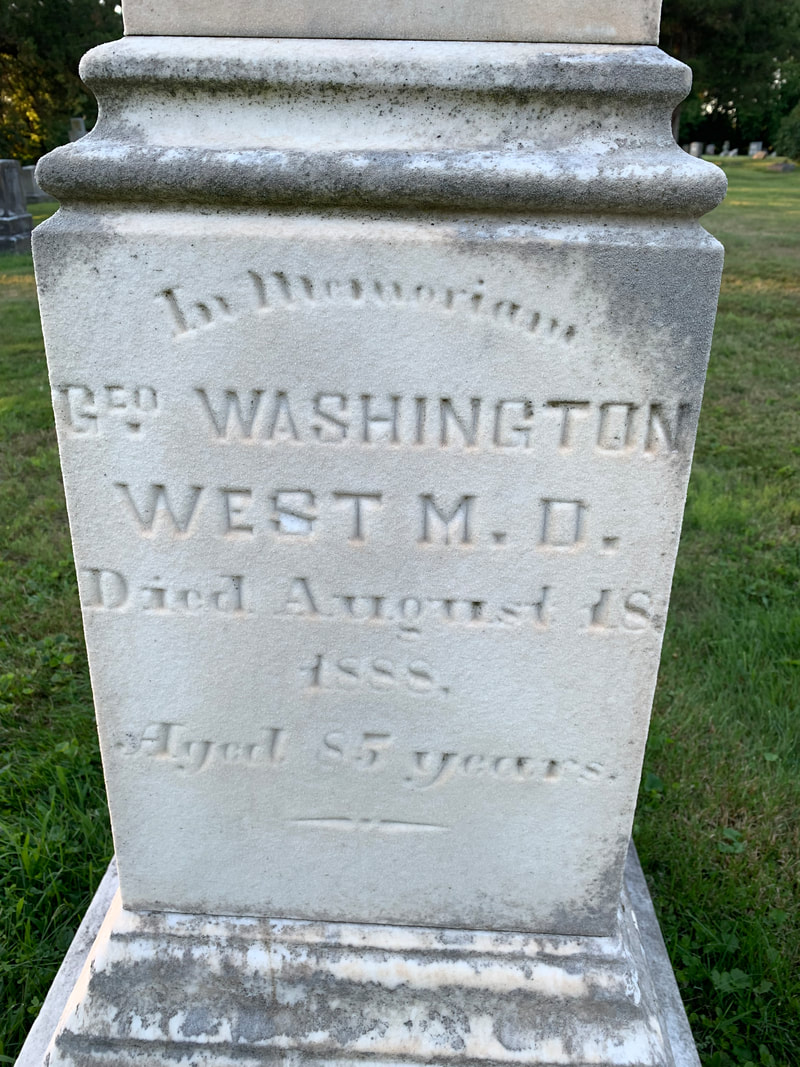

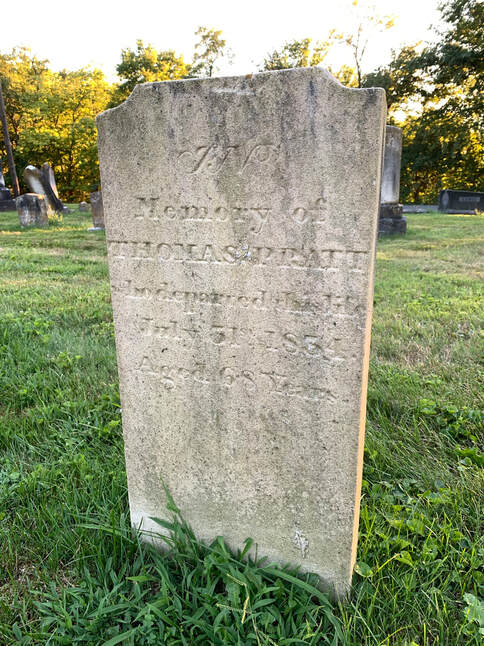

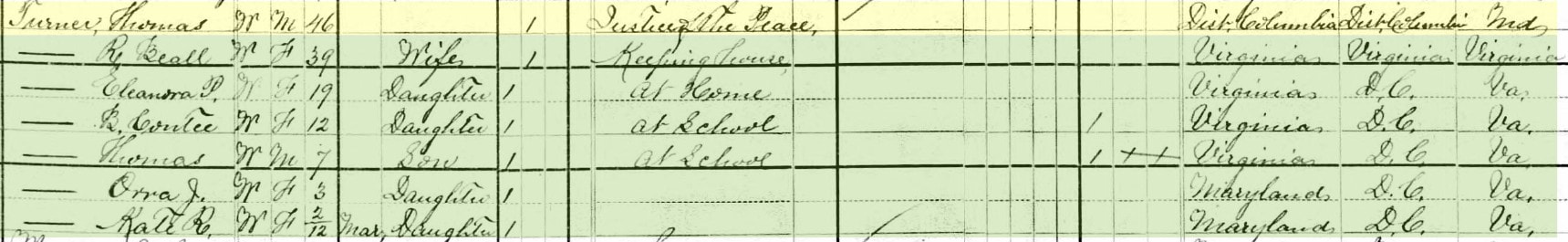

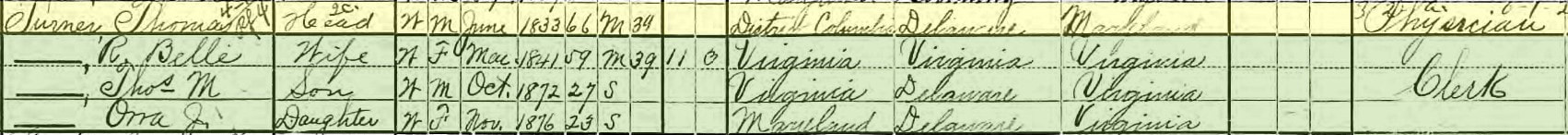

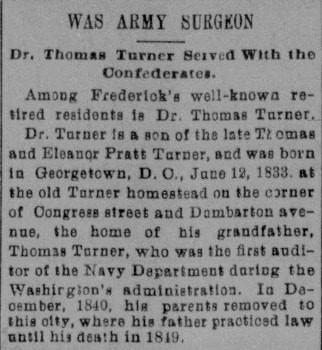

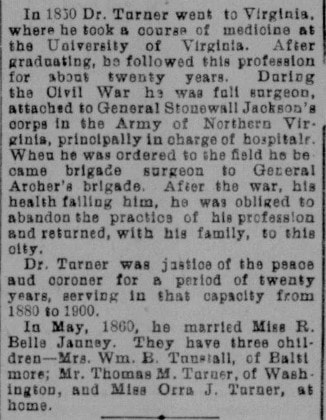

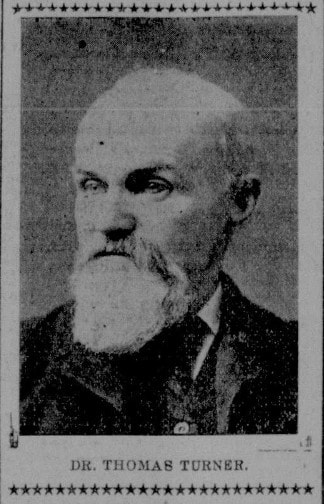

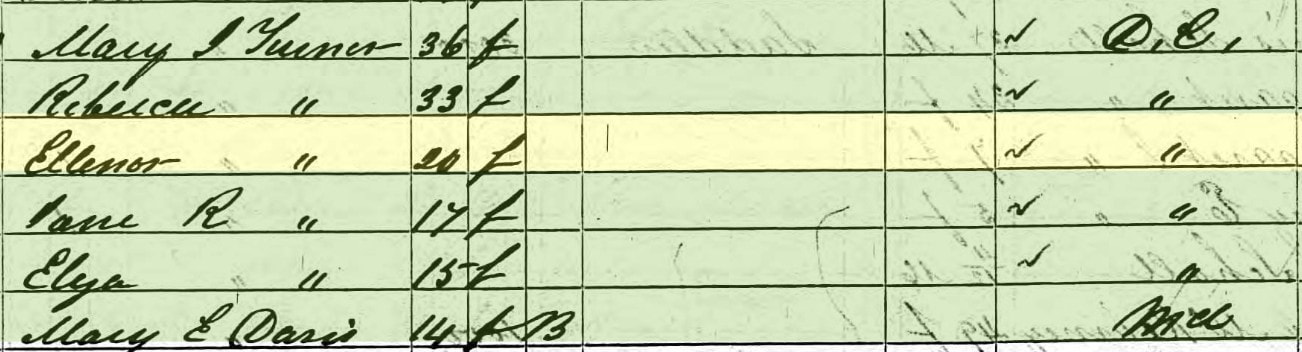

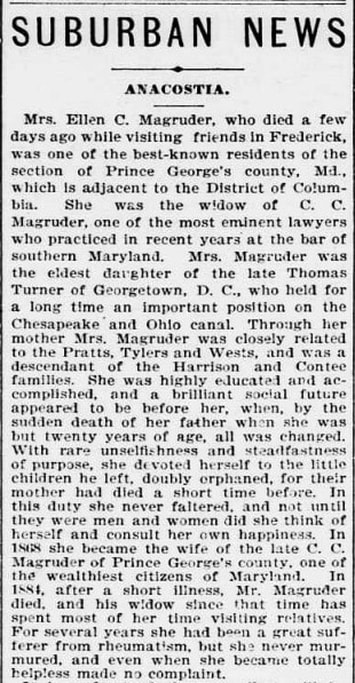

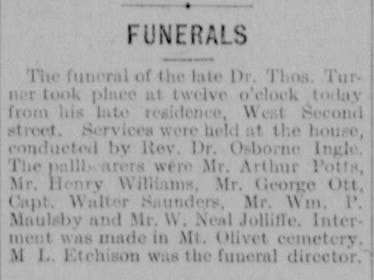

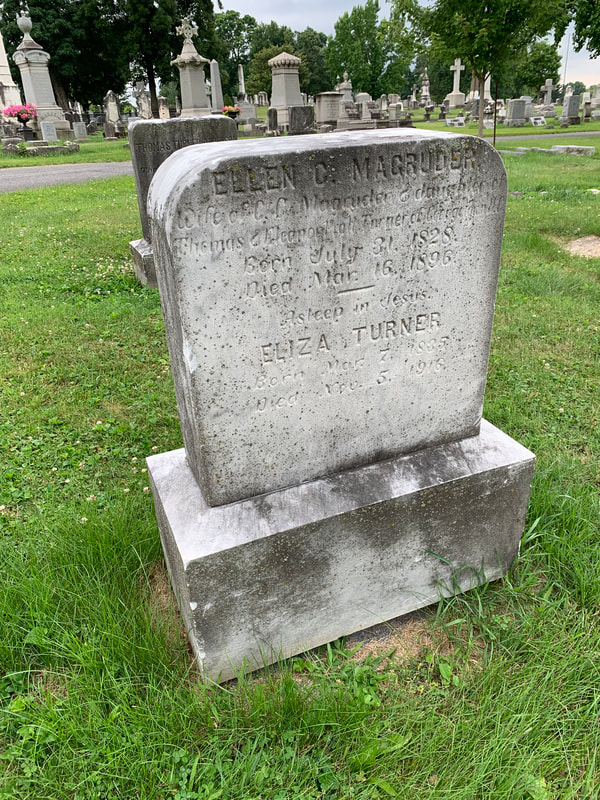

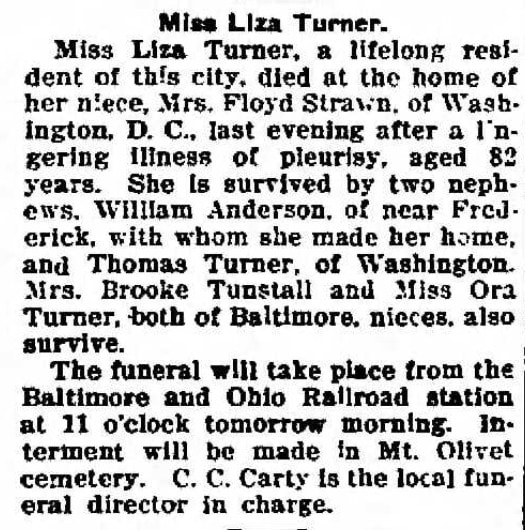

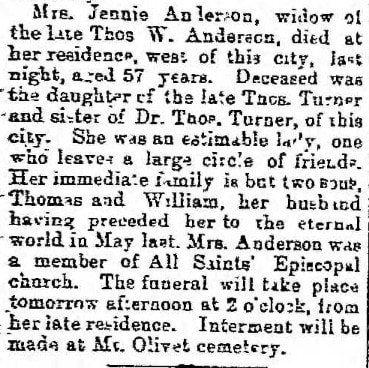

The D/2 Biological solution kills the lichen and whitens the stone, especially effective in the case of marble grave markers. This was the dominant material utilized in the early decades of the cemetery. D/2 is sprayed on the damp gravestone and one can see immediately things start to happen. You may question yourself as to why the gravestone is turning pink? Don't worry—as its normal for the stone to turn a subtle color of pinkish-orange, gray or purplish brown in other cases after applying the solution. This color change is the result of the biological organisms reacting to the solution. Not all stones react this way, but some will—and this discoloration is only temporary. When it does, it will generally take 24-48 hours before the discoloration disappears. So, the only downside is that you may have to come back after a few days to take some good "after cleaning" pictures. I give plenty of lectures and programs to civic and social groups around the county and talk about our continued preservation and fundraising efforts and am often asked, "Why do you want to clean the monuments as the wear and soiling gives them a unique character." I ask the question back of them saying "Why do we clean our cars, marble countertops, or power-wash decks and patios?" I tell them not to worry, just give it time and they will eventually be dirty again one day. More so, I explain the importance of cleaning as a necessary maintenance to preserve the longevity of the stone, especially in each monument's legibility. Let's just say, "A clean stone is a happy stone." If you are curious about the process and want to see it happening live, I invite you to come out some Thursday morning and see for yourself. Perhaps we may even recruit you to our ranks with a membership in our FOMO Group? (Contact me for more info if interested). Nan Markey, our "Chief Stoner," (pictured below) would love to have you as she has been leading our organized process section by section for the past two years. We are lucky to have this level of detail from the retired Registrar of Hood College, and plenty of other talented folks who care about Mount Olivet. So, what’s the deal with Eleanor and Thomas Turner’s headstone in Area H/Lot 399? Why would somebody only clean a small section of a large ledger stone? Au contraire, this is not the case at all! First off, let me explain the term “ledger stone” to those who may not be familiar with it. A ledger stone, or ledgerstone, is an inscribed stone slab usually laid into the floor of a church to commemorate or mark the place of the burial of an important deceased person. The term "ledger" derives from the Middle English words lygger, ligger or leger, themselves derived from the root of the Old English verb liċġan, meaning to lie (down). Think of accounting ledgers, and ledger paper and notepads—long and narrow. Ledger stones may also be found as slabs forming the tops of chest tombs. An inscription is usually incised into the stone within a ledger line running around the edge of the stone in the same manner a ledger book contains stacked rows of recorded information and numbers. Such inscription may continue within the central area of the stone, which may be decorated with relief-sculpted or incised coats of arms, or other appropriate decorative items such as skulls, hourglasses, etc. Stones with inset brasses first appeared in the 13th century.  An upright stone in the fashion of an olde world ledger stone of Europe is cleaned by preservation expert Jonathan Appell of Connecticut. This is the oldest formal gravestone in Frederick, likely the county as well. It belongs to Jacob Steiner/Stoner (1713-1748), one of Frederick's first settlers in the mid 18th century. Gravestones of this type are generally found in older, “colonial-era” cemeteries in New England and English-settled places like Williamsburg, Virginia or New Castle, Delaware. They also were a preferred grave marker of the wealthy. We have many examples here at Mount Olivet, some predating our cemetery and coming from other downtown graveyards. There are also instances of more recent decedents simply fancying this unique, throwback-style of monument. In the case of the Turners, here is a ledger stone that is propped up off the ground with four rounded-pillars. These appear to be standing on a flat rock, purposely put in place to be used as a foundation, as not to allow the pillars to sink into the earth below. This creates an optic looking like legs supporting a table or an altar. Regardless, you want to put something between the stone and the ground, so as to keep it from eventually sinking and being engulfed into the ground over time. The grave (stone and decedent) in question was moved here in 1859 from the former All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal Church Graveyard along Carroll Creek. Eleanor Turner died on March 28th, 1844. This took a little research as the All Saints’ Parish Burial Records (Register #3) states: “Ellen or Eleanor S. Turner, wife of Thomas (of D.C.), died March 28th, 1844, while her headstone recorded her death as March 27th, 1844.” As for Eleanor’s husband (or consort), I was fascinated to learn that Thomas Turner was the editor and publisher of the Frederick Town Herald, immediately before Lewis F. Coppersmith, the subject of our last “Story in Stone.” Coppersmith continued his predecessor’s role throughout the 1850s. What are the odds of that? As I’ve said many times, I love discovering these unique “connections” within these stories as it’s not just connections across family lines, but almost anything imaginable in some cases. Thomas Turner had begun a newspaper in Georgetown in 1837 called the Potomac Advocate and Metropolitan Intelligencer. Like Coppersmith, Mr. Turner also practiced law and served as a clerk as well for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. He died on January 31st, 1849 and his obituary appeared in multiple papers in Maryland and around the nation’s capital. One way or another, the Turner’s fashionable stone was apparently used as a makeshift table to hold another family member’s stone, or a portion thereof. This was Mr. Turner’s sister, Catharine Contee (Turner) Thomas. She died at age 30 on September 22nd, 1831. Jacob Engelbrecht made mention of this death as well in his famous diary. Like her brother and sister-in-law, Catharine is what we call “a removal,” and was brought here from All Saints Protestant Episcopal Graveyard as well. We learn that Catharine’s father (Thomas Turner, Sr.) was an "Accountant of the Navy Department" from the inscription on her headstone. The stone also records the fact that she was married to Dr. John M. Thomas. John M. is not buried here with her, as he died on December 28th, 1835, in St. Louis, Missouri, about the age of 38. Dr. Thomas was in the U.S. Army, but I cannot locate a burial for him here locally, in Maryland, Missouri, or the District of Columbia. Catharine’s mini-ledger stone must have sat on the Turner’s stone for quite some time as it protected/blocked the area directly underneath from the elements and pollutants. For reasons unknown, somebody recently moved Catherine’s stone toward the bottom of her brother’s ledger. Perhaps it was a descendant or interested genealogist who wanted to see what was written on the area of Eleanor and Thomas’ stone that was covered for all those years? Apparently, the Turners never bought a home in Frederick, unfortunately. Deeds found by my assistant, Marilyn Veek, for Thomas Turner involved bringing enslaved persons from Washington, D.C. into Maryland when he moved here. These included one in 1840 for a Negro girl named Emily (age 18) and a girl Phoebe (age 10). Other deeds were written in 1842 (a Negro girl Rachel age 11-12) and in 1844 (a Mulatto woman Letty Henson aged 30-35 and her infant child Maria Victoria aged about 15 months). I did, however, find the Turner’s former home when they lived in northwest Washington, D.C. It still stands and is in Georgetown, on the southeast corner of current day 31st Street, N.W. (formerly known as Congress Street) and Dumbarton Avenue. The Turners had a long history in Georgetown prior to moving to Frederick. Thomas Turner, Sr. (father of our “multi-colored stone” subjects) was clerk of the corporation of Georgetown prior to 1791 and was elected mayor on January 5th, 1795. Also in 1795, Thomas, Sr. was appointed by the governor of Maryland to a committee to assess the impact of constructing a road from Georgetown to a bridge to be built over the Potomac at Little Falls. The bridge would become a reality and featured several stone abutments and wooden cross sections that went across the Potomac. Little Falls is the place on the river where Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia meet. You may recognize this structure as “Chain Bridge,” which originally was a covered wooden bridge completed on July 3rd, 1797. It apparently rotted and collapsed by 1804, and a replacement of the same design burned around 1805. Numerous bridges have been built in the same position since then. Speaking of bridges, Thomas Sr.’s son, Thomas Turner (Eleanor's husband), was on a committee that petitioned the U.S. Senate to build a bridge in connection with the aqueduct for the Alexandria Canal Company. This was the first Aqueduct Bridge, built in 1830 to carry the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal across the Potomac to connect with the Alexandria Canal on the Virginia shore. The bridge was later converted into a roadway during the American Civil War. In 1866, the canal was restored, and a new wooden roadway built over it atop trestles. The 1830 bridge was torn down in 1884, and a new structure was built, opening in 1889. This would be named for an individual who once lived on the Georgetown side of the bridge that takes motorists across the river to Rosslyn (VA)—the Francis Scott Key Bridge and is more commonly referred to the Key Bridge. The Washington and Virginia abutments for the original crossing still survive. Both are located a short distance west of the Key Bridge. Between the two abutments, a pier also remains in the river near the Virginia shore. How’s that for “bridging” history? In January of 1800, Thomas Turner, Sr. (the father of Thomas Turner and Catharine Thomas) was nominated by John Adams to be Fourth Auditor (accountant of the U.S. Navy) in the Treasury Department and served for 16 years. As mentioned earlier, this position is noted on daughter Catherine Contee (Turner) Thomas’ ledger headstone. Fitting that a ledger stone connects to a ledger entry about an accountant, isn’t it? Mr. Turner had his hands full with the new branch of our young country's armed forces. He would serve in this position throughout the duration of the War of 1812, and was likely very familiar with fellow Georgetown resident and notable war personality Francis Scott Key and his catchy tune about the flag over Baltimore's Fort McHenry. Examples of Thomas Turner Sr.'s accounting prowess with these published reports on US Navy expenditures at the time of the War of 1812. Eleanor Pratt and Thomas Turner were married in 1825 in Allegany County, which seems odd at first glance, but both had ties to Cumberland as a home thanks to the construction of the C & O Canal. Not a great deal is known about Eleanor, but there is a definitive connection to Frederick through her mother, Christiana B. (Tyler) Pratt (1767-1825), a sister of Dr. John Tyler (1763-1841). We will review the accomplished life of Dr. Tyler another time as he is buried here in Mount Olivet, but many are familiar with the fact that he was one of our country’s first accomplished ophthalmologists and receives credit as one of the first physicians to perform cataract surgery. His majestic home of West Church Street still survives and is known as the Tyler-Spite House. Catharine (Turner) Thomas is named for Dr. Tyler’s wife, the former Catharine Contee Harrison (1770-1831). Both Dr. and Mrs. Tyler are buried in Area MM/Lot 52. There is yet another family link as our subject Thomas Turner’s mother was a sister to Mrs. Tyler in the form of Eleanor Contee Harrison who married Thomas Turner, Sr. 1n 1792. When Dr. Tyler died intestate in 1841, there was an equity court case. Thomas Turner was one of the trustees appointed in the case to handle the sale of Tyler's property but, refrained from buying any of it himself. Eleanor’s father was Thomas George Pratt, born in the year 1769. He removed from his native Prince Georges County to Allegany County (Maryland) and eventually afterwards lived in southwestern Frederick County at a point about five miles from Harper's Ferry. This was a 245-acre plantation bought in 1830 from the estate of Daniel Leakins which included part of Fielderia Manor on the eastern slope of Catoctin Mountain east of Jefferson (near the intersection of MD 180 and Mount Zion Road). Unfortunately, Pratt got himself into debt and had to sell this property off in 1832. After that, he apparently lived with his son-in-law, a man named George Washington West (1803-1888) who married his daughter Eliza. The same year of 1832, a year after the death of Catherine (Turner) Thomas, saw more heartache for Mr. Pratt, the Turners and recent widower Dr. John M. Thomas—all connected to our Mount Olivet “Stonehenge of stacked ledgers” in form of a table in Area H. Thomas Turner’s first-born son, named Thomas Turner, would die of Scarlet Fever at the home of Dr. West on October 8th. One week later, Thomas Turner Thomas, only child of Dr. Thomas, would pass of likely the same ailment at the same location. Both obituaries appeared in the October 8th edition of the Frederick Town Herald. In 1834, Pratt sold West two enslaved persons; the deed includes the following language: "I Thomas Pratt fully aware of the trouble inconvenience and expense to which Doct. George W. West and his family have been subjected by the board of and attention to myself during the four last years & that the same will continue so long as I may live, and being willing and desirous some compensation to the said Doct. George W. West for the services so rendered and to be rendered by himself and family.” And here is another amazing connection, but perhaps more so for me, because of a personal link. I recently became interested in the George W. West family through my son’s girlfriend who lives on a parcel that was once part of the larger West plantation known as Westhill Farm. This is located just “west” of Petersville, a small hamlet located on the fore-mentioned MD180, the original road from Frederick to Harpers Ferry which at one time was a turnpike. Westhill Farm is quite picturesque and can be seen from MD 340 as well, with its stone manor house, barn buildings and an adjacent pond. Thought to be built around 1800 by Thomas H. West, the house passed to his son, Dr. George Washington West (1803-1888), in an 1832 partition of real property following his death. Dr. West was a prominent local physician and former graduate of the University of Maryland in 1825. George W. West would own the farm for more than 50 years and his name is shown on both the 1858 Bond Atlas and 1873 Titus Atlas of Frederick County. Since I rarely get to speak on Petersville, the village grew as a stop along the turnpike with businesses to serve travelers as well as local farmers. The land on which Petersville is situated was originally patented by Captain John Colvill as the "Merryland Tract" on November 5th, 1731, containing over 6,000 acres. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, Petersville began to develop as a village, with lots facing the turnpike route and four cross streets. The village also sat at the crossroads of one of the valley's north-south roads leading from Middletown to Berlin (today Brunswick). The 1808 Varle Map of Maryland shows Petersville as well. Five years later, in October 1813, the Petersville Post Office was established (it closed in 1909). The Maryland General Assembly established the Petersville District in 1829. In his will, Thomas Pratt had intended to leave his own plantation at Fielderia (part of the former site of a short-lived, colonial era furnace operation by Fielder Gantt) to his son John Wilkes Pratt, who was named executor. Unfortunately, by the time Thomas died in 1834, he had lost the property. John Wilkes Pratt declined to return to Maryland to be executor as he had gone to Cass County, Illinois for health reasons. While there, the brother of the fore-mentioned Eleanor (Turner) and Catherine (Thomas) worked as a lawyer, served in the State Legislature, and performed duties as Cass County’s first County Clerk. Not living to see it, Thomas Pratt would've been proud of the fact that his son excelled where he, himself, fell short. Mr. Pratt’s grandson (John Wilkes Pratt’s son) Thomas George Pratt was even more accomplished. The young man studied law and returned to his father’s native state to settle in Prince Georges County. He would serve in the House of Delegates and State Senate for several years before becoming Maryland’s governor from 1845-48. Two years later in 1850, Thomas and Eleanor Turner’s nephew, Thomas G. Pratt, was elected to the U.S. Senate to represent the Western Shore of Maryland. As for the governor’s namesake, I found Eleanor (Pratt) Turner’s father buried next to his daughter Eliza and husband George W. West in St. Mark’s Apostolic Church Cemetery on the “east” side of Petersville. After Eleanor and Thomas passed in the mid to late 1840s, their children were split up. Son Thomas became a physician at age 17 and went to live with Samuel Turner, his uncle (also a physician) in Clarke County, VA. Thomas was still living in Clarke County in 1860, but I could not locate him in 1870, as he was possibly lying low after the American Civil War since he served with the Confederacy as a surgeon. In 1880, Dr. Turner and his family were living on South Market Street in Frederick. In 1900 the family was living at what is now 125 W. Second St, in a house owned by George Nixdorf. The younger Thomas Turner never bought any real estate of his own, but in the late 1890s held a mortgage from Bettie Ritchie on the house then known as 50-52 W. Church St. She defaulted on the mortgage, and he sold the property at 50 West Church Street to Otho Keller and 52 West Church Street to Henrietta Maulsby. Today these properties are labeled as 116-118 W. Church Street. We did a story on Mrs. Ritchie a few years back as she was the foundress of our original Frederick Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Eleanor and Thomas Turner’s daughters remained in Frederick. In the 1850 census, the head of household was Mary Jane Turner, age 36. The others were Rebecca, age 33, Ellenor “Ellen”, age 20, Jane R. age 17, Eliza, age 15. An obituary for oldest daughter Ellenor (aka Ellen/Eleanor Contee (Turner) Magruder) from the Washington Star says she was very prominent later in life after showing selflessness in caring for her younger siblings after the parents died. Mary Jane Turner (1814-1867) and Rebecca Turner (1817-1877) are aunts of Eleanor, Jane “Jennie” Rebecca and Eliza—making them sisters of our subject Thomas Turner. These ladies bought what is now 211-213 East Second St in 1855. The property was sold in 1879 after Rebecca's death (the current building is more recent, however). I couldn’t determine where they were living in 1850 but, did discover that Rebecca had employment with the U.S. Navy. Here in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 399, Mary Jane, Rebecca and Dr. Thomas Turner are buried next to Thomas and Eleanor Turner’s table-resembling memorial. The physician died on September 6th, 1908 from "a pulmonary affection." Within adjoining lot #403, one can find grave markers for Thomas and Eleanor’s daughters: Ellen C. (Turner) Magruder (1828-1896), Eliza Turner (1835-1916) and Jane "Jennie" (Turner) Anderson (1831-1888). Frankly, all these stones could use a good cleaning, and hopefully they will match the small, pearly white rectangle that can be found on Thomas and Eleanor’s discolored grave ledger!

1 Comment

Jacquelyn M Ebersole

8/15/2022 02:50:31 pm

OH, what a story. Loved it. Especially the info on C&O canal at Little Falls. Westhills - recently sold. Petersville and all the rest. Have seen the Dr. West name forever at the museum (Brunswick Heritage Museum).

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed