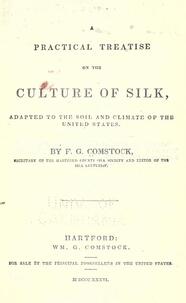

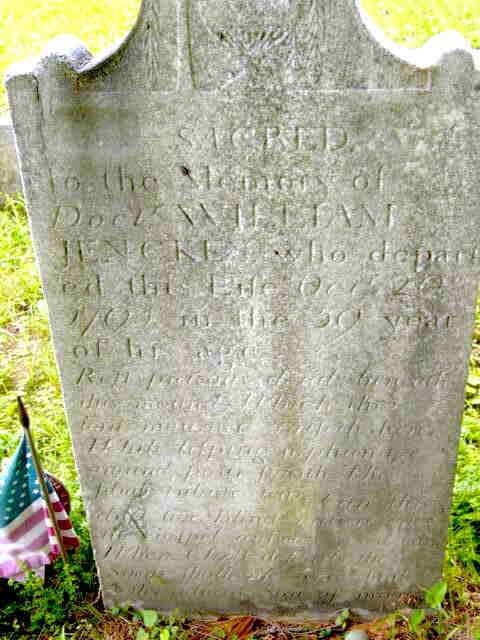

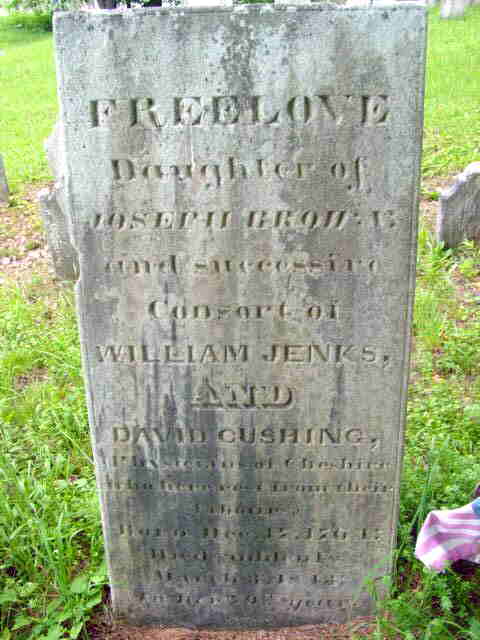

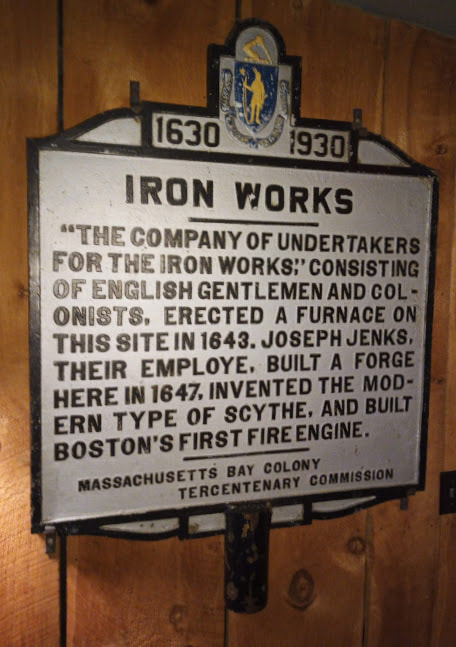

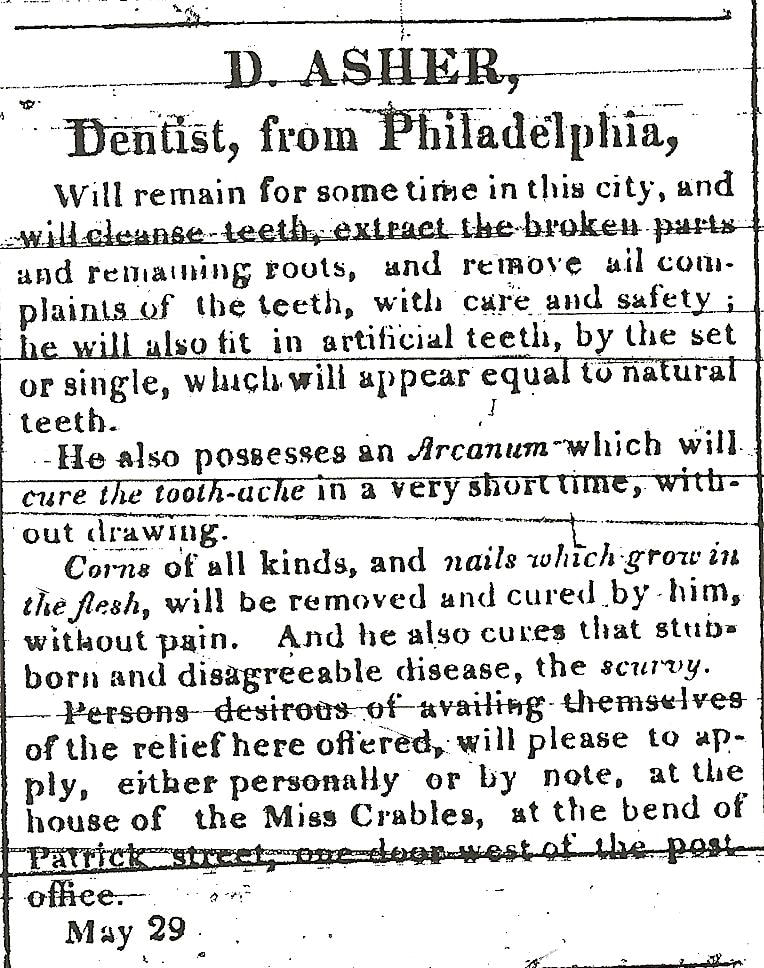

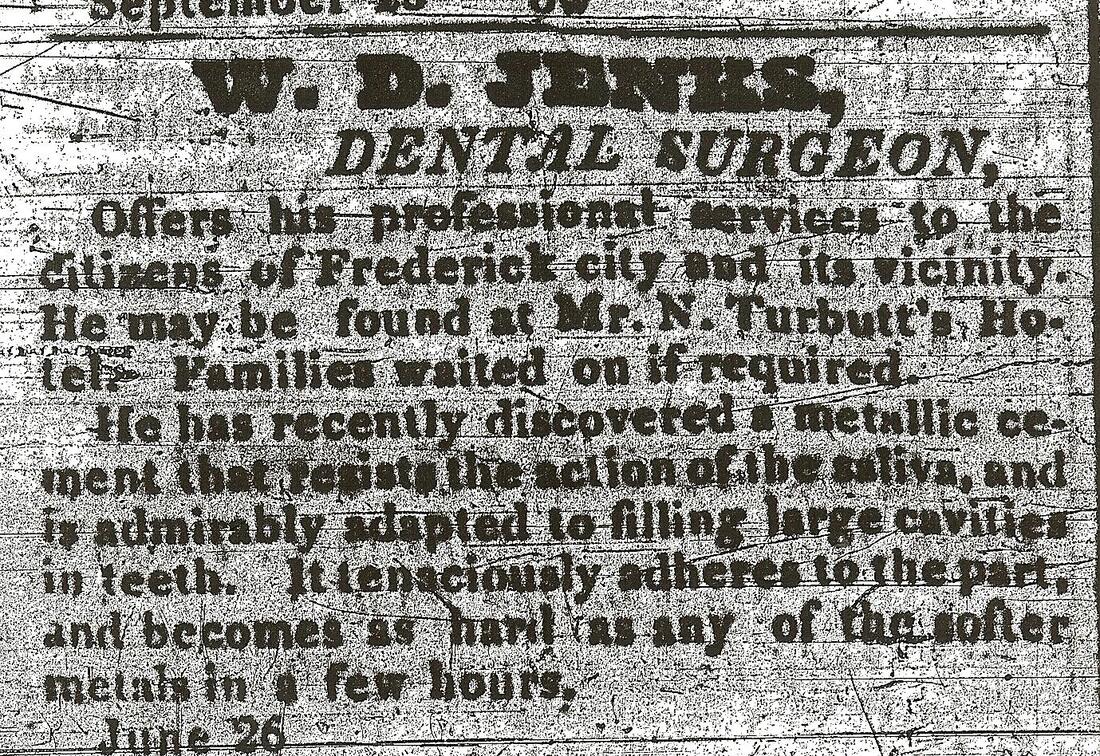

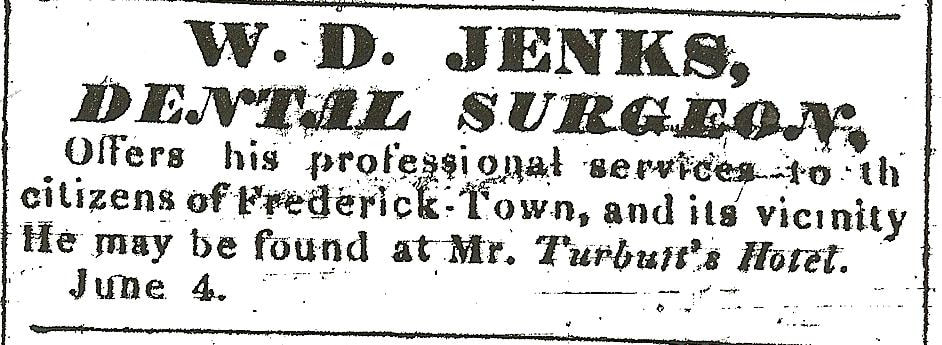

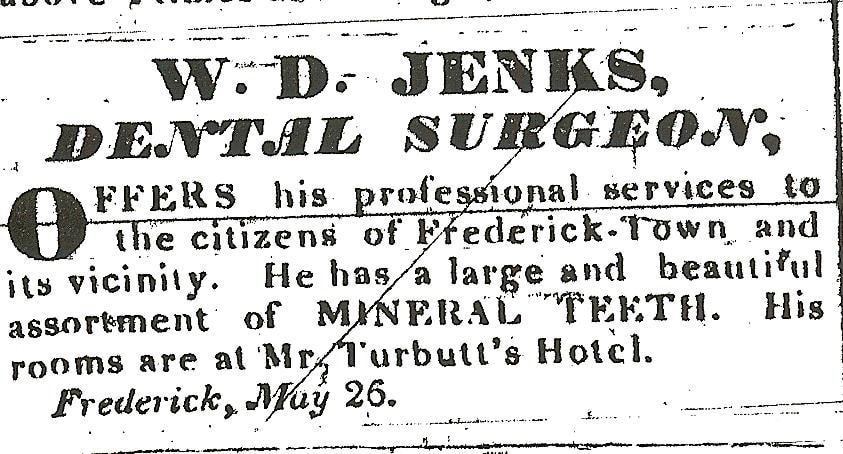

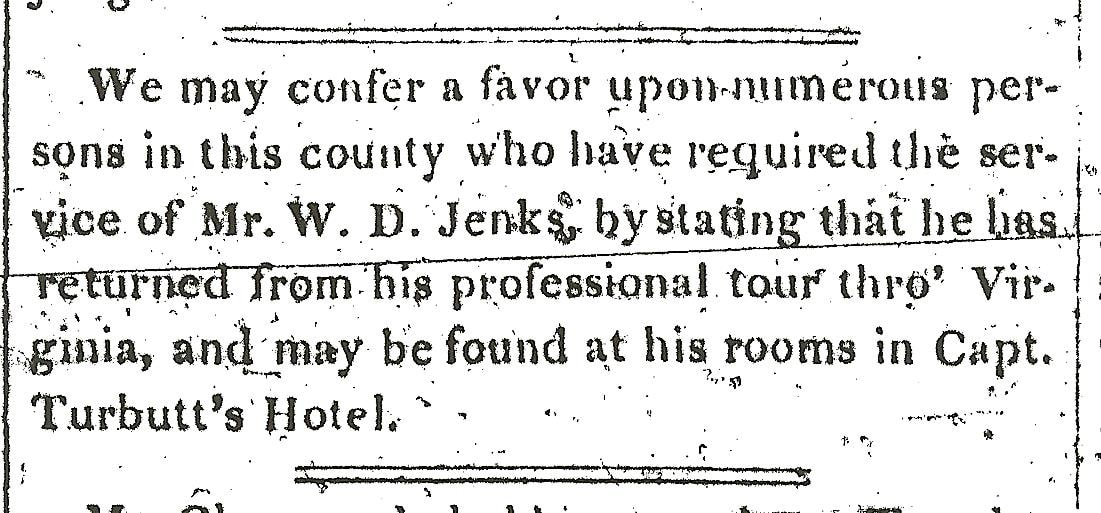

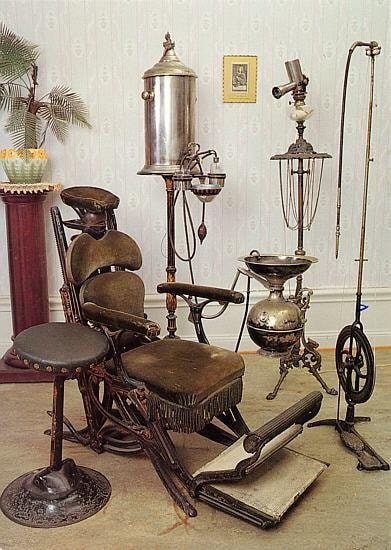

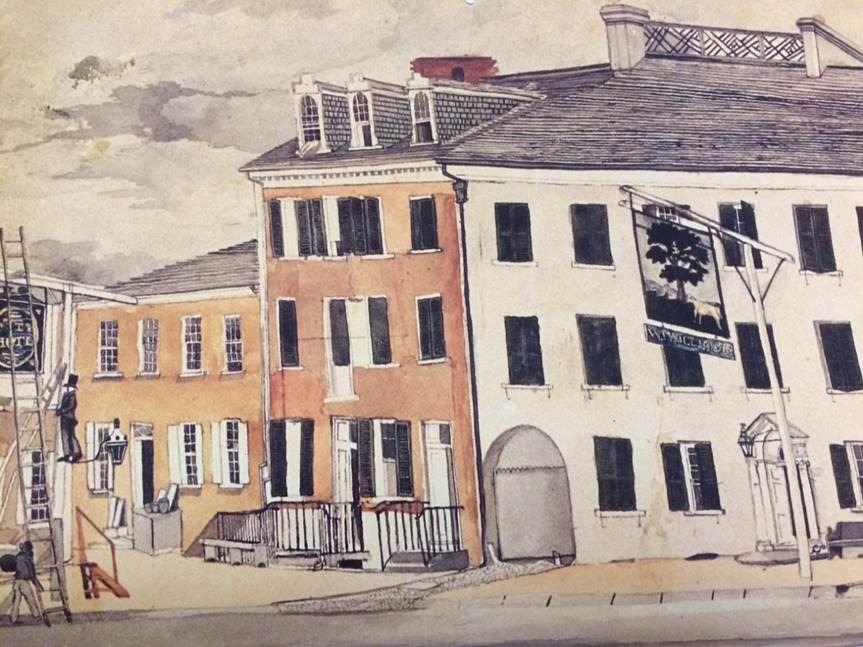

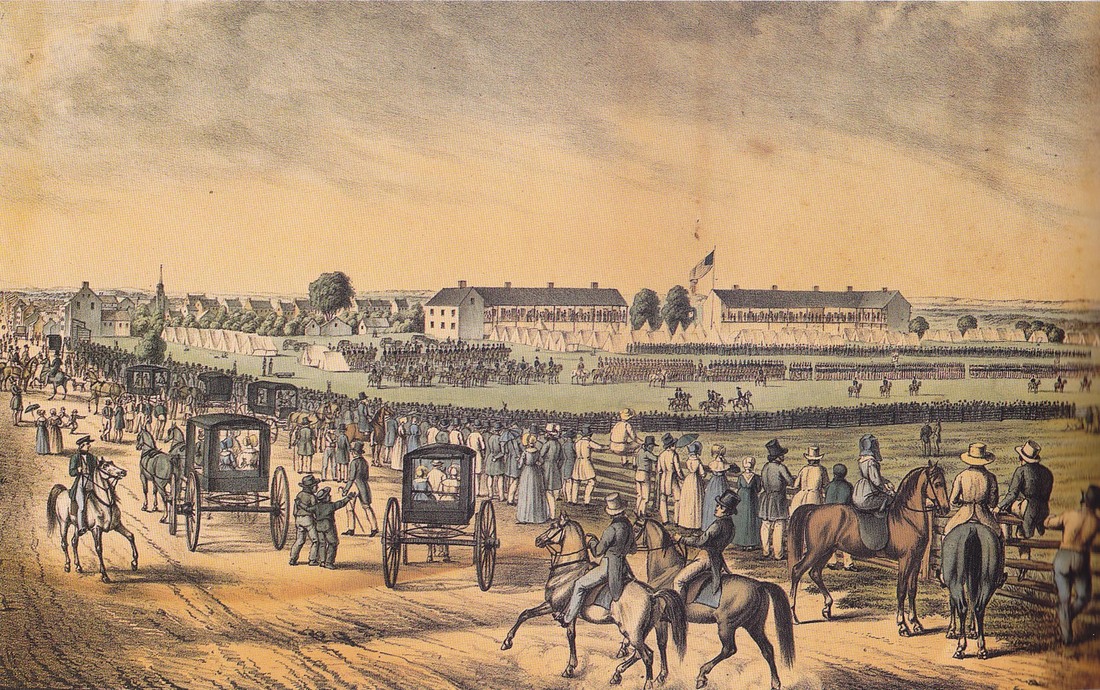

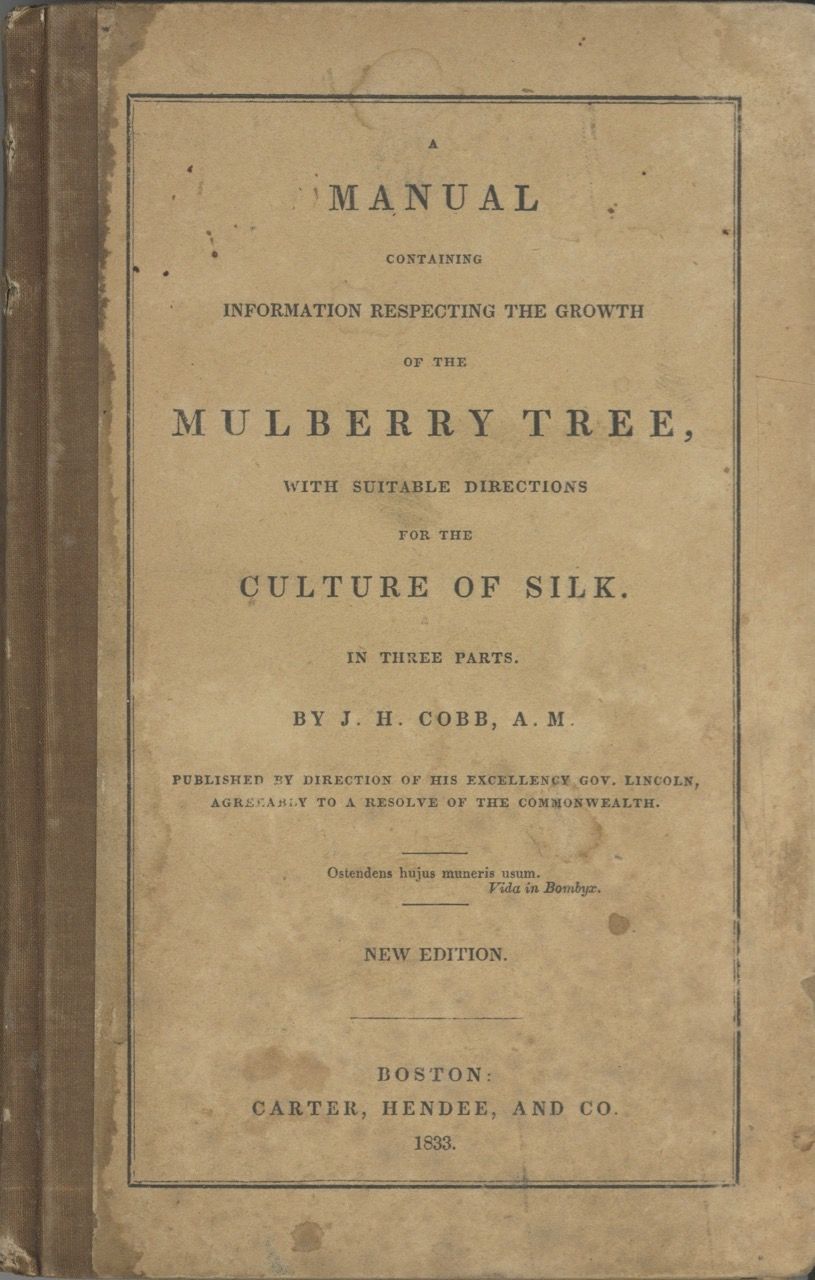

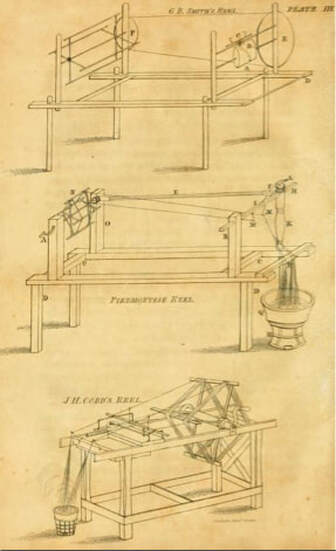

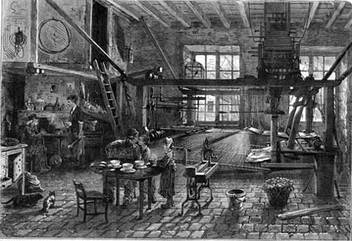

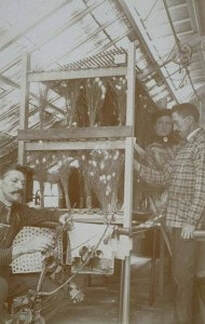

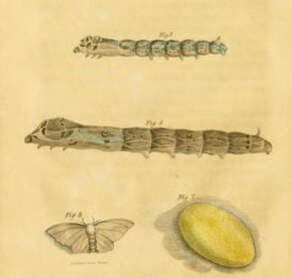

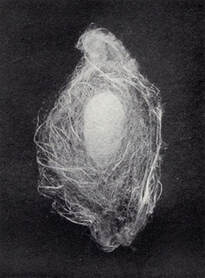

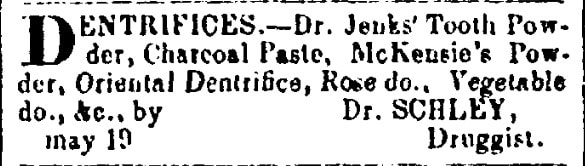

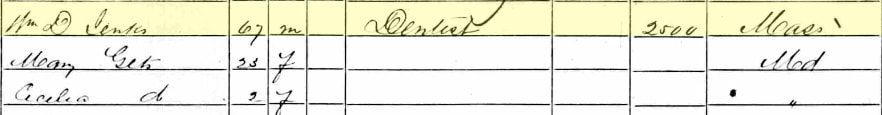

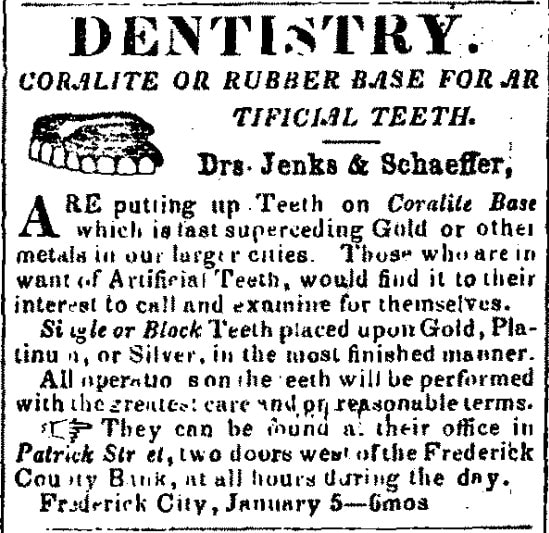

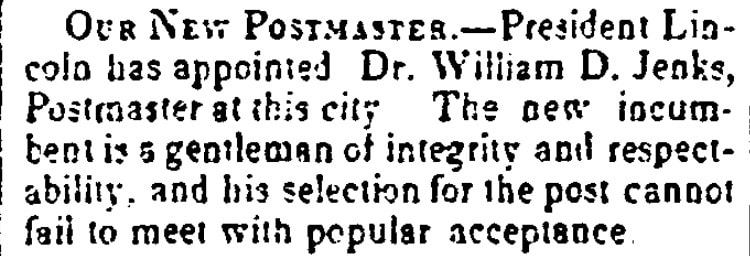

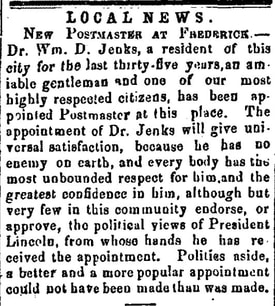

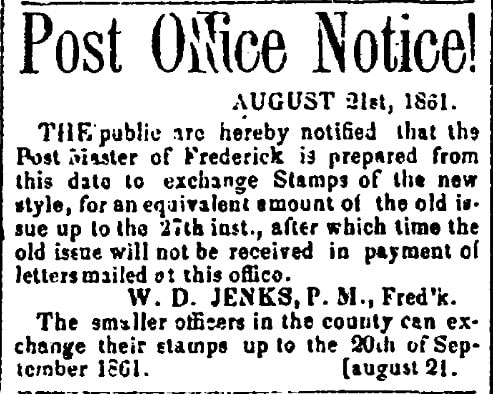

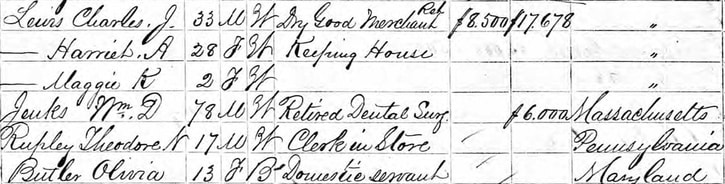

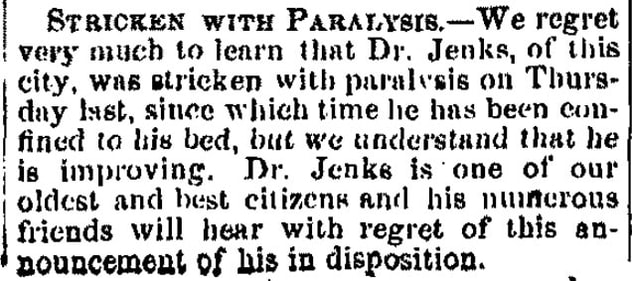

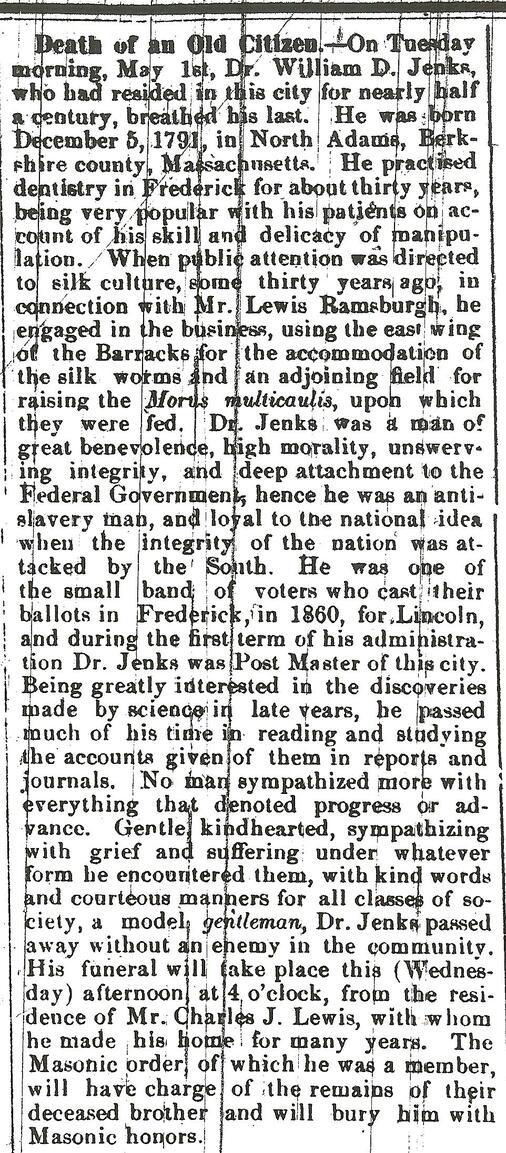

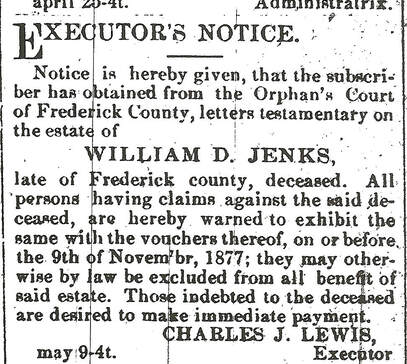

Once known by the name as Pumphouse Hill, a central area of Mount Olivet represents the highest elevation in Downtown Frederick. This was the one-time location of an actual pumphouse which fed water to all parts of the cemetery. Today, the pumphouse is long gone, but the area’s central facet is Founder’s Garden, a tribute to the seven church congregations that helped with the founding of this non-denominational burying ground which opened in 1854. A decade earlier, this was a farm field with a commanding view to the northeast that included the Frederick Barracks silhouetted against a large grove of mulberry trees. Today, at these "lofty heights," the view of the barracks is quite obstructed by buildings, but one can find some of the most prominent families and characters in Frederick history within a small radius. Just a few yards from Founder’s Garden, is the stand-alone grave monument of Dr. William D. Jenks (1791-1877), the man responsible for the previously mentioned Mulberry trees. I have been familiar with this gentleman, at least in name, for over 25 years now since my work on a video production called Frederick Town, a 10-hour documentary featuring a chronological telling of our town’s history from 1745-1995. Dr. Jenks was one of our earliest dentists. In addition, he, along with a business associate, was responsible for one of Frederick’s strangest, yet short-lived business endeavors, commencing in the late 1830’s. William Dexter Jenks was born on December 5th, 1791 in Cheshire, Berkshire County, Massachusetts. He was the youngest of four children born to Dr. William Jenckes (1757-1794), a private of the American Revolution who fought in a Rhode Island regiment and mother Freelove Brown (Jenckes) (1764-1843). Our Dr. Jenks received his middle name courtesy of his maternal grandmother, Hopestill Dexter (Brown). It was tough finding any early information on Dr. W. D. Jenks. His parents were natives of Rhode Island and moved their young family to Massachusetts prior to our subject’s birth. Dr. Jenks’ third great-grandfather (Joseph Jenckes, Sr.) emigrated from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1643 and was involved with organizing and operating the first American iron works in the New England Colonies (1646). In 1953, this iron works was excavated and rebuilt to what is now the Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site in Saugus (MA) located about ten miles northeast of downtown Boston. Joseph Jenckes is credited with America’s first machine patent with his design of a waterwheel used at the forge. He would also be inventor of the first fire engine apparatus to appear on the continent in 1654. Joseph’s son, Joseph Jenckes, Jr., was also a native of Great Britain, having traveled across the Atlantic with his widowed father in the 1640s. An ironworker as well, Joseph Jenks, Jr. is credited as being the founder of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Dr. Jenks’ father (Dr. William Jenckes) died a few months before the boy’s third birthday. His mother would remarry a gentleman named Dr. David Cushing and six additional step-siblings would come from this union. It comes as no surprise that our subject would enter into the medical profession like his father and step-father. I don’t know if they were dentists per se, but am assuming rather general practitioners. I also was not able to find anything on William Dexter Jenks’ professional schooling/training, or anything pertaining to his youth and young adulthood for that matter. A public family tree is posted on Ancestry.com which infers that Dr. Jenks married a woman named Julia A. Hamilton in the year 1806 in Hamilton, Butler County, Ohio. It goes on to show that the couple had three children: Judith (b. 1837), Freeman (b. 1839), and Harriet Ann (1841-1929). I have found nothing about any of these individuals in searching records galore. I feel somewhat confident in stating that the family historian that posted this either holds the only key, or is completely mistaken as Jenks’ obituary makes no mention of a former wife or children. I'm leaning towards the latter, especially after discovering that Jenks' brother, Stephen B. Jenks, moved to East Hamilton, NY, married a woman named Julia Ann, and had children named Judith and Freeman. I do know that W. D. Jenks came to Frederick in the late 1820’s, likely 1828, as his obituary dated 1877 says that he had spent nearly half a century in the western Maryland town of ours. I performed hours of additional research at the Maryland Room of C. Burr Artz Library hoping to discover his exact arrival. Sadly, the particular microfilm reel of the Frederick Town Herald newspaper facsimiles dating from summer 1827-mid fall 1830 is missing from the collection, and has been for years. Although this is conjecture, I feel that Dr. Jenks simply answered the call of local residents here looking for a dentist and moreso, a dental surgeon. In perusing earlier newspapers, I happened to find an advertisement dating from 1824 heralding the services being offered by an early dental physician named D. Asher of Philadelphia. It appears that Dr. Asher was simply an itinerant professional who set up “shop” during his stays at Frederick in the home of a Miss Crables (likely Miss Graybill) on W. Patrick Street. I saw no other dentist advertisements in local newspapers until I saw an immediate ad for Dr. Jenks on the front page of the first newspaper I scrolled to within the ensuing microfilm reel (after the missing reel). One year later, famed Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht mentions our New England physician in an entry that dates to October 4th, 1831: “This day I had a jaw tooth extracted by Doctor W. D. Jenks. It was the 3rd from behind on the lower right jaw. It is the first I had extracted, except when I was a boy and then did it with thread & a sudden jerk. I had the next hind one plugged by Doctor Jenks on the 16 October & one filed.” I would see several other advertisements in the years to follow. Of particular interest was a small mention in the January 4th, 1834 edition of the Frederick Town Herald which sheds light on the fact that like the previously mentioned Dr. Asher of Philadelphia, Dr. Jenks apparently took his talents out on the road.  Dr. Jenks continued to serve the Frederick community throughout the 1830s, a decade that saw plenty of town growth and passers through as the National Pike was busier than ever with rushing stage coaches, settlers in large wagons heading westward, and travelers and livestock coming eastward along with valuable trade items and natural resources from the burgeoning Ohio River valley. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad had arrived in town in 1831, changing the transportation landscape forever. Jenks continued to live and run his practice in hotels of town, Capt. Nicholas Turbott’s Tavern at first and later Talbott’s Tavern, operated by Joseph Talbott. This latter hostelry was located at the northeast corner of W. Patrick and Court streets, diagonally across from the Frederick County Courthouse of today. The site had hosted Gen. Lafayette back in 1824 and would gain later fame as the City Hotel before its removal in the early 20th century to make way for the Francis Scott Key Hotel. In my researching endeavors for this story, I found an article published in 1968 in which the managing staff of the Frederick News-Post became recipients of a booklet containing copies of several letters written by Dr. Jenks to relatives living in East Hamilton, New York, home to Dr. Jenks’ brother Stephen B. Jenks. In one of these letters, written in 1831, Jenks estimated that Frederick had a population of 5,000. He mentioned that the city had eight churches and that there was “an elegant and expensive iron railing” around the Court House. According to Jenks: “Frederick had a flourishing Academy for the education of boys, and also a Catholic Seminary and an Orphan Asylum operated under the direction of the Sisters of Charity.” In describing the citizenry, many of whom made up his customer base, Dr. Jenks reported: “A stranger on visiting Frederick County would discover little of that urbanity of manners so fascinating in the warm hearted Southerner; they are, however, sober, industrious and frugal; but the want of a system of general education is deeply felt.” Jenks said that he had never known business so dull, and he regarded the farmers as an unusually fortunate and happy class of people at that time. He went on to write: “The farmer, who is free from debt and can raise his own bread and meat is your most independent man after all, and must be the happiest.” Perhaps this last shared impression was the impetus for William D. Jenks to make a very interesting move in the late 1830s? In April, 1837, the local newspaper reveled in reporting to its readers: “Dr. Wm. D. Jenks has planted this Spring in the vicinity of this town, 20,000 white mulberry trees. On the growth of one year, for the purpose of feeding silk worms, and purpose of planting the same number next year." Jacob Engelbrecht would shed a bit more light on the progress of the enterprising tooth expert with an entry written into his diary on July 2nd, 1838: “Silk Worms—Messrs. William D. Jenks & Lewis Ramsburgh have a cocoonry at the barracks and their mulberry trees next to the barracks field. I saw them yesterday. Nearly mature they have about worms, this is the first year.” Of course, the barracks referred to the Frederick “Hessian” Barracks located today on the campus of Maryland School for the Deaf, just a stone’s throw from Mount Olivet’s front gate.  The process, as demonstrated by Dr. Jenks’ actions, begins with the mulberry tree and the silkworm, which is a type of caterpillar. The silkworm prefers a diet of mulberry leaves, and produces a cocoon which, when unraveled, can be spun into silk thread. In case you are curious, silk production is called sericulture. Historians trace the origins of what has been coined the “Mulberry Mania” or the “Multicaulis Craze” of the 1830s to an 1826 Congressional report. This stated that too much money was being spent on imported silk and that, to remedy this, the feasibility of domestic production should be explored. The result of this investigation was a 220-page illustrated manual published in 1828 by the U.S. Treasury Department. Following the federal lead, state legislatures took up the issue of silk production. Back in Dr. Jenks’ native state, the House of Representatives of Massachusetts actually passed a resolution in 1831 that a treatise be compiled that would contain “the best information respecting the growth of the mulberry tree, with suitable directions for the culture of silk.” The author of this work, Jonathan H. Cobb of Dedham, MA had experience in sericulture and claimed that he was able to produce $100 worth of silk a week year-round. Cobb’s promise enticed farmers with visions of silk production as the surest way to “acquire so much [income], with so little capital and labor.” Mr. Cobb also pitched silk production as a means of alleviating rural poverty. Cobb envisioned self-sustaining towns run silk farms, suggesting that “paupers” and students provide the labor. This manual also predicted ample funds would be available for public works and schools “if all the highways in the country towns were ornamented with a row of mulberry trees.” By the end of the decade, thousands of volumes had been printed and this wildly popular work had gone through four editions.  Similar works were published up and down the east coast. In 1836, F. G. Comstock, a Hartford, Connecticut seed dealer, published A Practical Treatise on the Culture of Silk, his own contribution to a growing body of work that sought to promote the planting of mulberries. With the fertile ground of imagined riches thus well prepared, the introduction of a new mulberry tree from China was the seed that allowed a bout of wild agricultural speculation to take root. Around 1830 a new variety of mulberry was introduced in America from France. It was known as Morus multicaulis, for its habit of sending up multiple sprouts from the base. This variety also had very large leaves and was said to be the secret behind the Chinese success at silk production. Nurserymen in several northeastern states began to grow the trees in great quantities. At the height of the bubble, young mulberry trees sold for up to $5 each, while the going rate for trees of other species was thirty to fifty cents apiece. Mulberries are fast growing, as well as easily cloned from both softwood and hardwood cuttings, so a skilled propagator was able to realize great profits. The dizzying heights which the speculation reached caused an insatiable demand for the multicaulis mulberry. In hindsight, it is clear that that market speculation drove the price of the mulberry trees well beyond the value of any silk which might be produced from the leaves. Indeed, none of the accounts from the period tell of any but theoretical profit made from silk farming, but instead of equal parts lucky and wily nurseryman who were able to capitalize on the craze. Dr. Jenks and Mr. Ramsburg also had the State of Maryland behind them as can be seen by proceedings in the Maryland General Assembly session of 1840. In January, the silkworm entrepreneurs received the permission necessary to utilize the Hessian Barracks for their endeavor.  John Thomas Scharf wrote in his History of Western Maryland (published in 1882): “From 1840 and for several years afterwards a portion of the Barracks (which belonged to the State) were used by special permission of the Legislature by Messrs. Jenks & Ramsburg as a cocoonery. They had a white mulberry orchard, consisting of ten acres, in an adjoining lot. The State granted them the use of the Barracks buildings to test the experiment of silk-culture, then creating so much discussion throughout the country. W. D. Jenks began operations and planted his trees in 1837. Feb. 28, 1840, the reels were put up. During the year sewing silk was made equal to that of foreign manufacture. After the flyer was in operation, gold-stripe vesting was manufactured in considerable quantities. With Jenks and Ramsburg leasing the Barracks, silk worms were being raised on the second floor. It has been said that results for this local endeavor were not commercially promising, although enough silk was produced in 1843 that a pair of silk stockings was woven by Buck, a prominent stocking weaver based on Patrick street. Supposedly, the following year featured silk being sent to the penitentiary, where a vest was woven, but this was the peak of the silk industry in Frederick County.  Another resident of town wrote on the subject of the Frederick cocoonery, present in her youth. This was Catherine Susanna Thomas Markell (1828-1900) who wrote an unpublished manuscript entitled "Short Stories of Life in Frederick in the 1830s." Mrs. Markell wrote in her memoir: "An orchard of thrifty white mulberry trees, covering ten acres, flourished on the sunny eastern slope. The greatest interest was manifested by citizens of all classes and for us children, the whole procedure possessed an inexpressable fascination. Imagination exhausted itself in varied speculations as to what new phase would be next developed. With unbounded admiration, we regarded the huge hampers of glistening, white, yellow and orange-colored cocoons, and when, after undergoing a heating process for the destruction of the grub, interminable lengths of soft gossamer fibre were wound smoothly off the great reels or flyers, our delight defied control.  In wonderment akin to awe, we watched the mysterious advent of the butterflies and the dainty things emerged, one after another, from their pretty oval prisons and hovered o'er the mulberry foliage strewn about on long plank tables. Upon these leaves the tiny eggs were deposited and upon them also the larvae subsequently fed. The moth, in its exit from the sheath, severed many strands of its fibre, thus rendering the cocoon in a measure worthless for reeling, though an uneven, lustre-less thread, known as "spun-silk" was often fabricated from these "cut" cocoons and used for knitting purposes."  Like all bubbles, the "Mulberry Mania" of the 1830s grew and grew until it popped. Precipitating events for the rapid deflation of the industry nationally can be blamed on a blight which wreaked havoc on newly-planted mulberry orchards in 1839, along with a particularly hard winter in 1844, to which many surviving trees succumbed. These two calamities offered a moment of clarity to farmers who had been swept up in the craze. This helped prove the point that silk production was not viable on a large scale in America. Too many factors, from climate, to the necessary labor and the knowledge of the production process were hurdles too large to surmount. By the time the market crashed, nurseries could not even sell a bundle of a hundred mulberry trees for a dollar. The operation at the barracks likely ceased by 1843, opening the opportunity for the grounds to be used easily with the large military encampment under Gen. Scott. Luckily, Dr. Jenks had a legitimate, and proven, career to fall back on. He continued to operate on teeth and create smiles here in Frederick. It’s just a shame he didn’t have the foresight to see the possibility of silk dental floss, embodied today by the product named Dental Lace. Dr. Jenks was a member of the Columbia (Masonic) Lodge #58, and served as a Methodist church trustee although he identified more closely with the Unitarian Universalist religion. He also busied himself with politics. In fact, Jenks’ obituary shares that he was among the small minority who supported (and voted for) Abraham Lincoln in the presidential election of 1860. He personally cast one of 2,294 votes for the future “Great Emancipator.” Many are surprised to learn that Lincoln only received 2.48% of the popular vote statewide, finishing last behind three other candidates: John Breckinridge (42,482 votes), John Bell (41,760 votes), and Stephen Douglas (5,966). Well, Dr. Jenks’ support did not go unnoticed as he was aptly rewarded after President Lincoln took office. This came in the form of an appointment as Frederick’s new Post Master. Dr. Jenks would conduct this job with great pride until having to step down for health reasons in 1865. I presume the assassination of his political icon that same year didn’t help matters either. Two years later, health setbacks forced a retirement from the dental business. Dr. Jenks soldiered on, living with a gentleman named Charles Lewis and family. According to the family tree I saw on Ancestry.com, Mr. Lewis would be Jenks' son-in-law, having married supposed daughter Harriet A. Jenks (b. 1842). I did find that Lewis was a merchant who owned a dry goods store on W. Patrick Street, and the family lived on the premises as this was Dr. Jenks' last home. The Lewis family would eventually move to Clarendon, TX in the late 1880s and be buried there. Charles would be appointed a Post Master of Clarendon years later, so I'm guessing the connection could be more along "postal" lines rather than familial. I'm thinking Jenks took Charles under his wing as a mentor of sorts. I still remain skeptical on this issue of Jenks being married with children, even though Charles and Harriet Lewis would name their first-born son William Jenks Lewis (1871-1960). Dr. Jenks would die on May 1st, 1877 at the age of 85. I’d really like to think that the good doctor breathed his last, with head lying comfortably on a silk-upholstered pillow from his earlier venture begun “two score” earlier. The former New Englander would be buried in Mount Olivet’s Area F/Lot 5. He had bought two adjoining plots when the cemetery was created in the early 1850s. With no family buried in the vicinity, his monument is surrounded by a nice green-space. It almost begs to ask a final, and befitting, question: “Is there room to plant a few mulberry trees?”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed