|

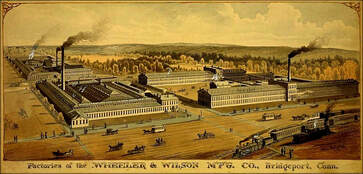

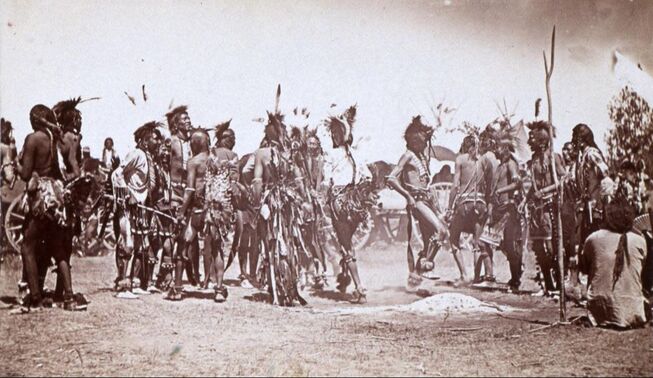

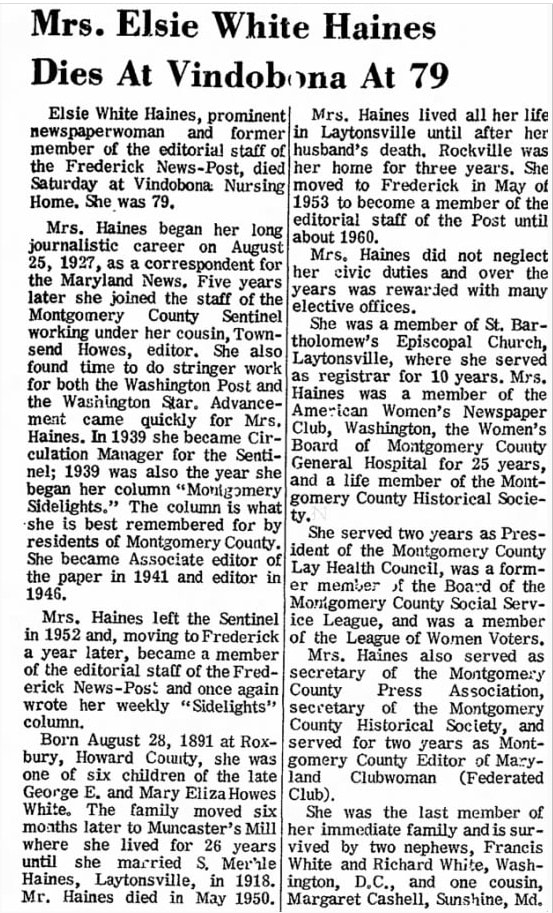

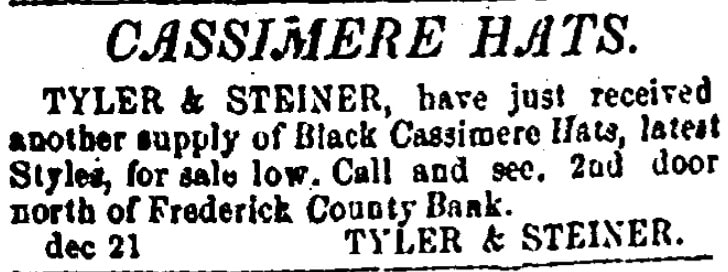

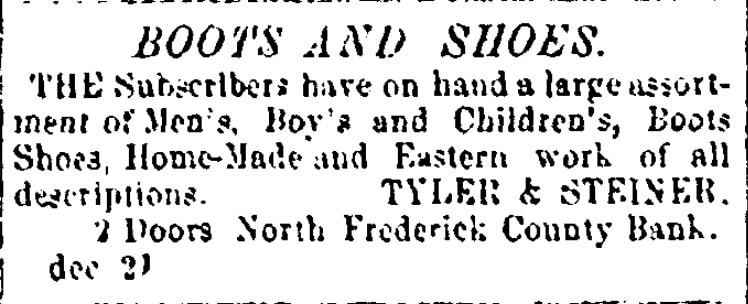

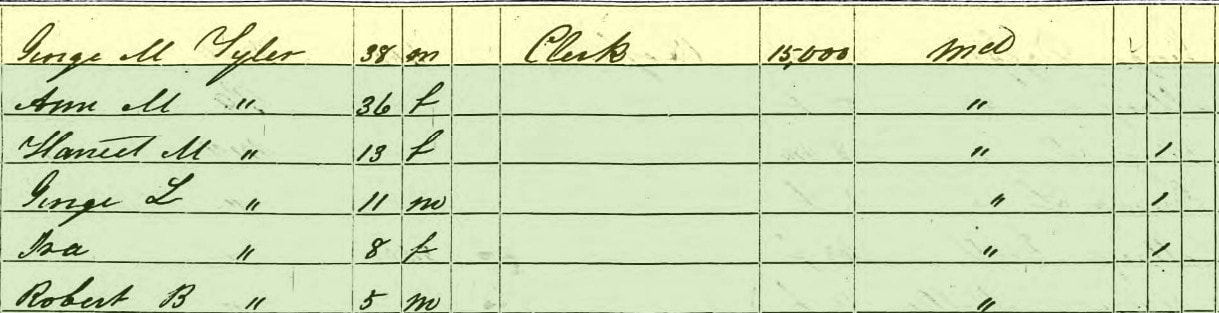

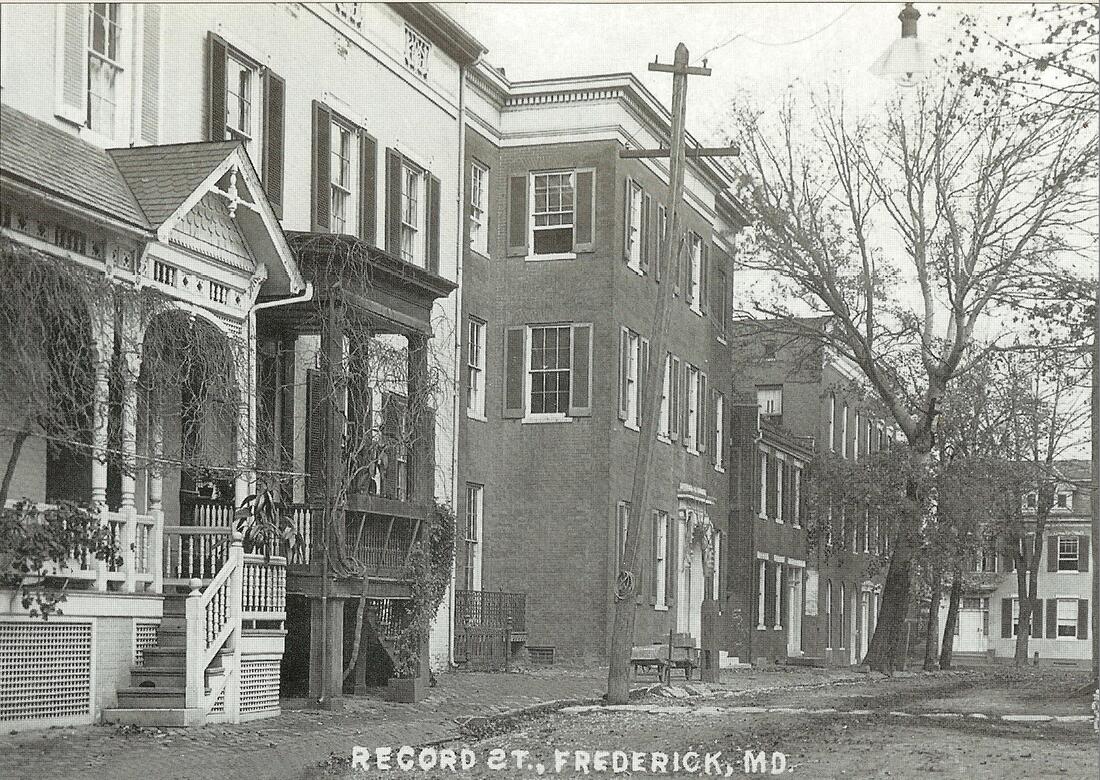

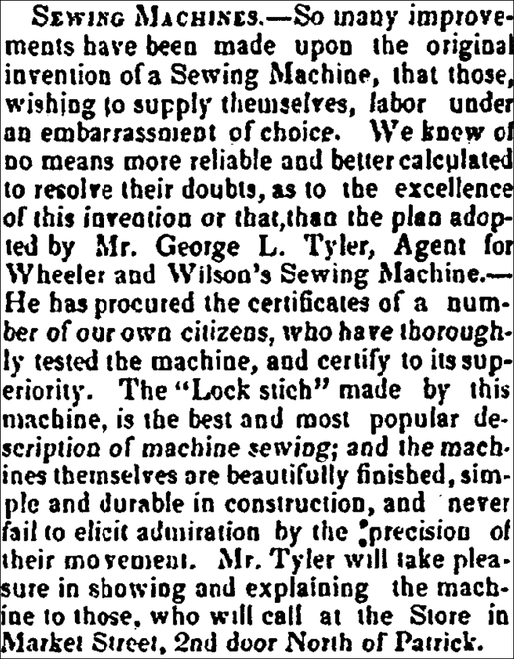

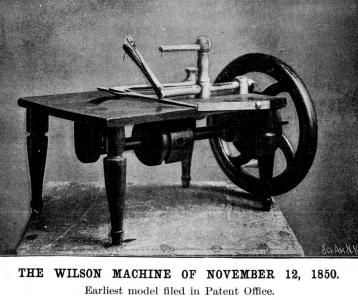

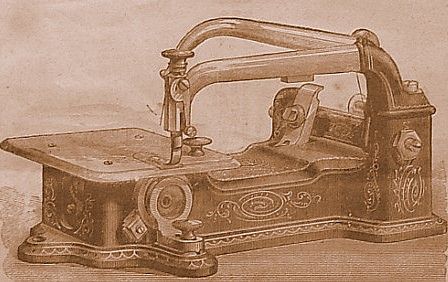

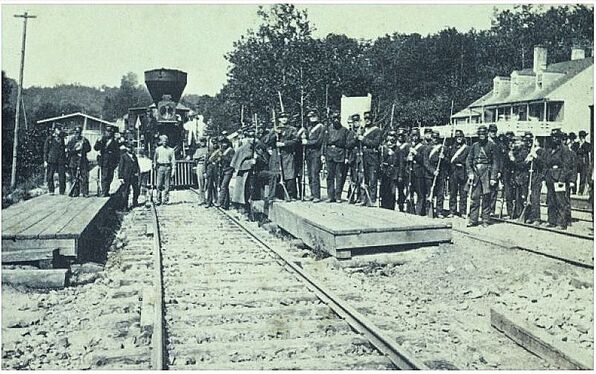

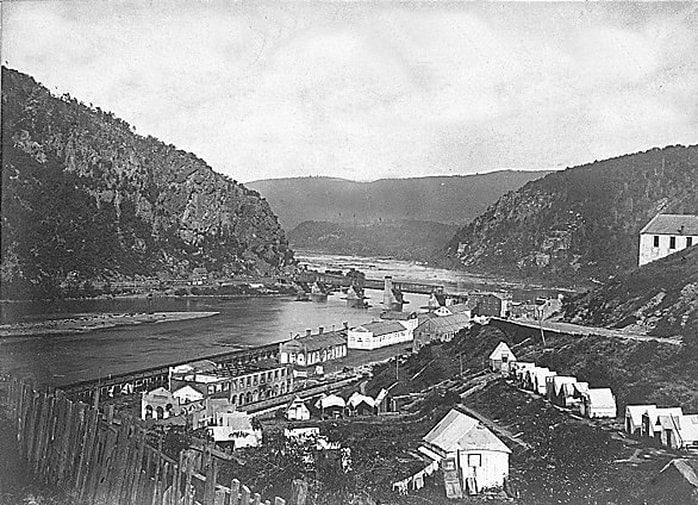

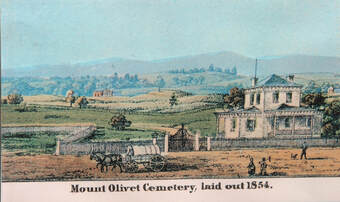

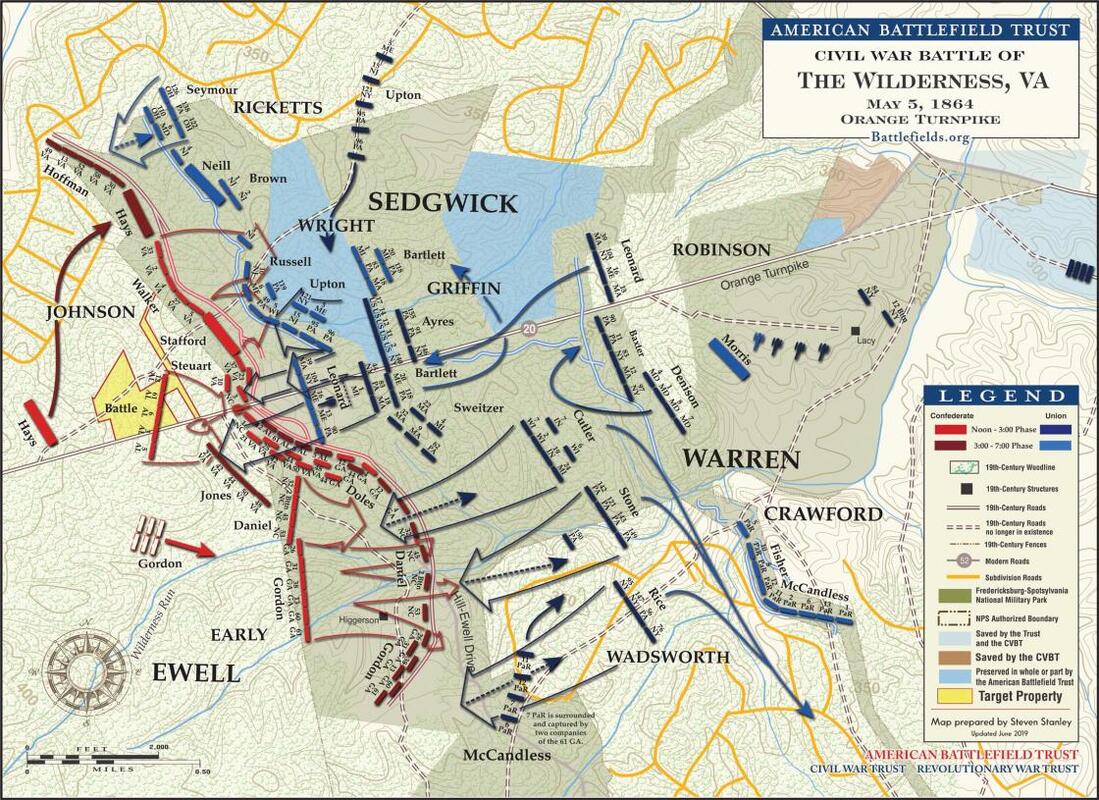

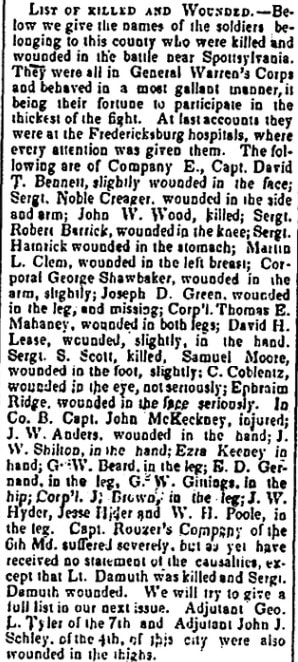

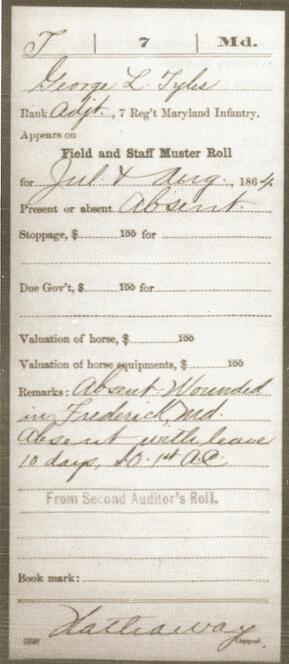

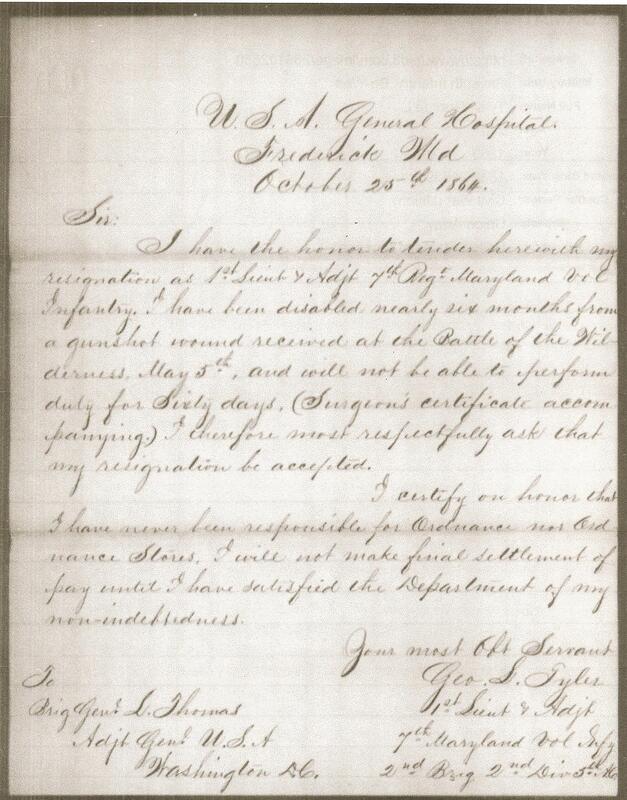

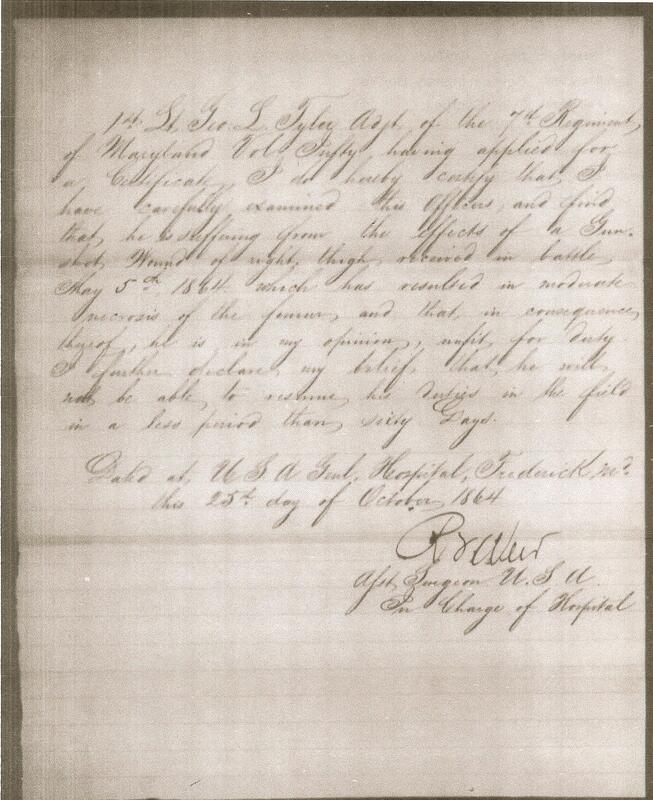

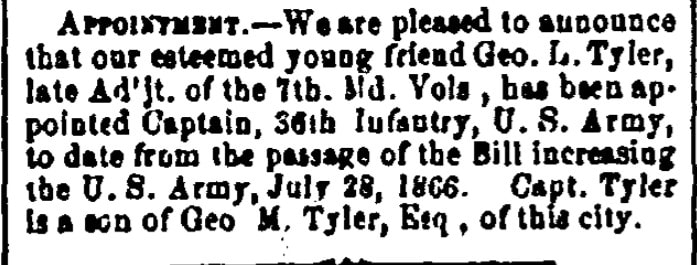

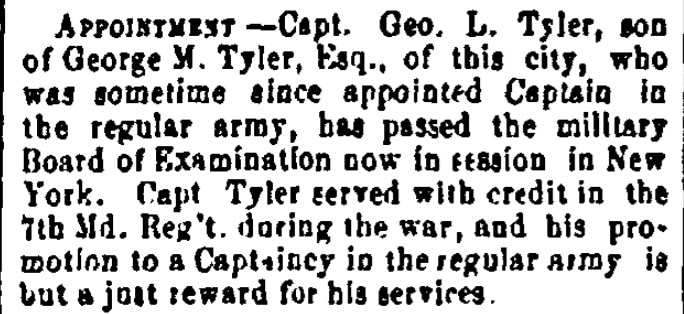

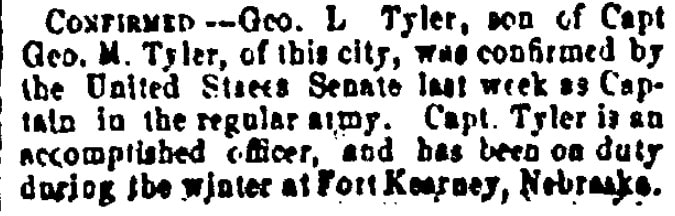

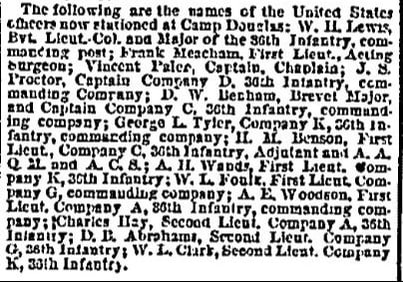

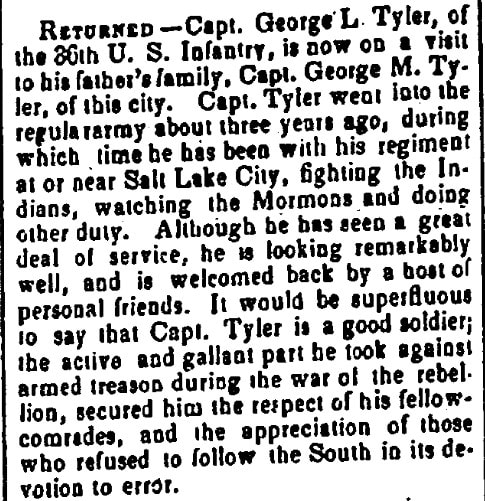

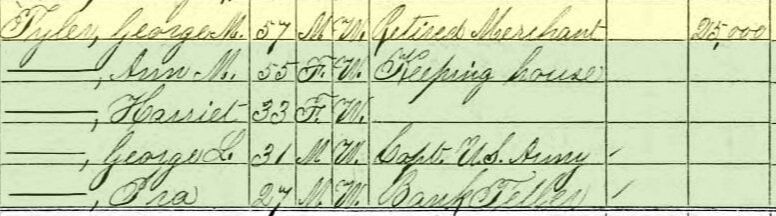

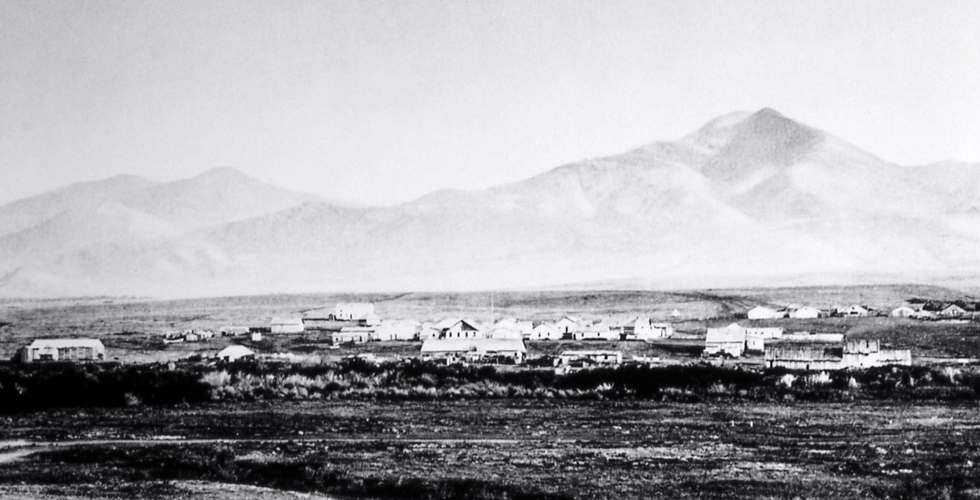

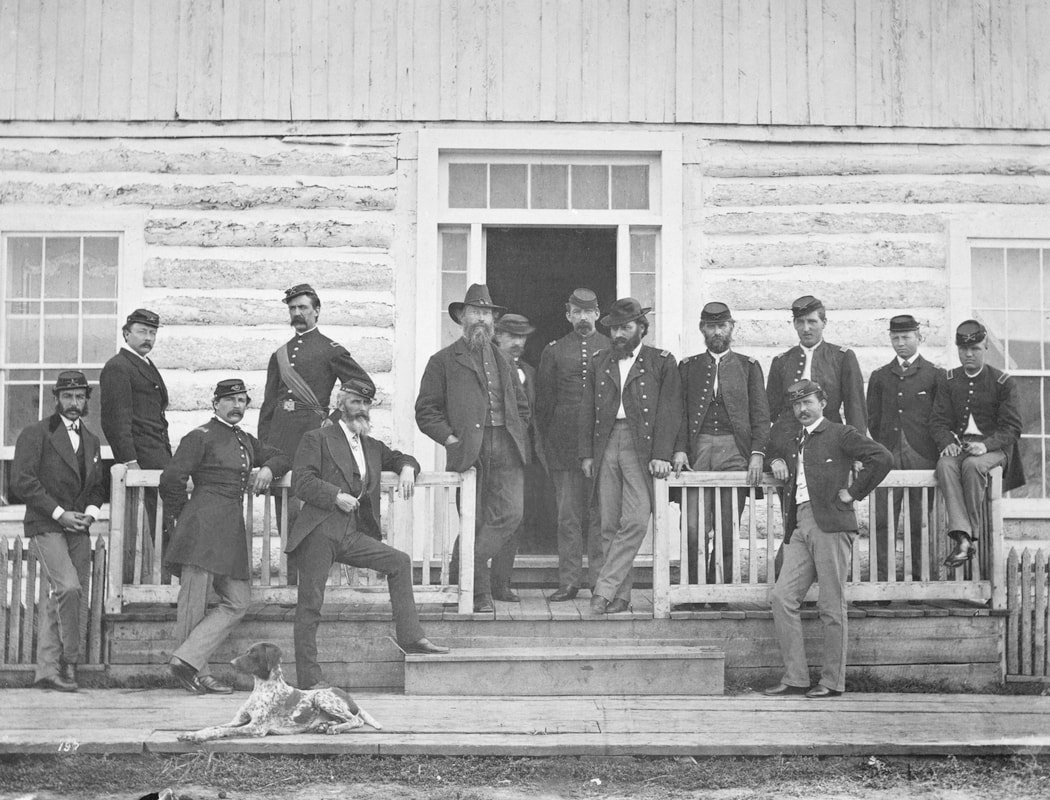

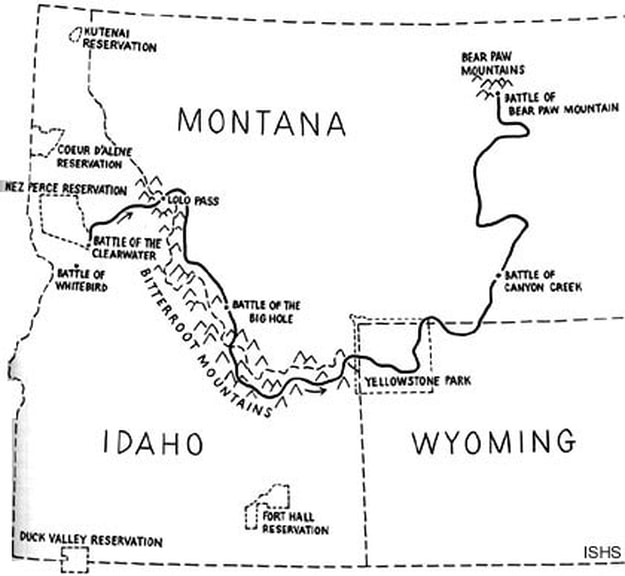

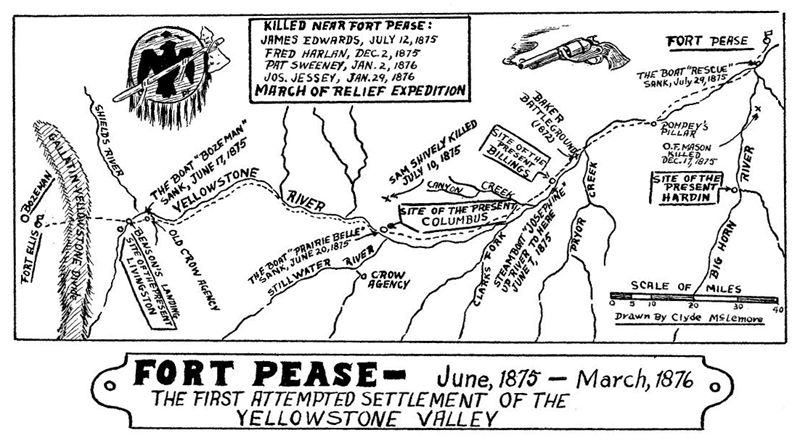

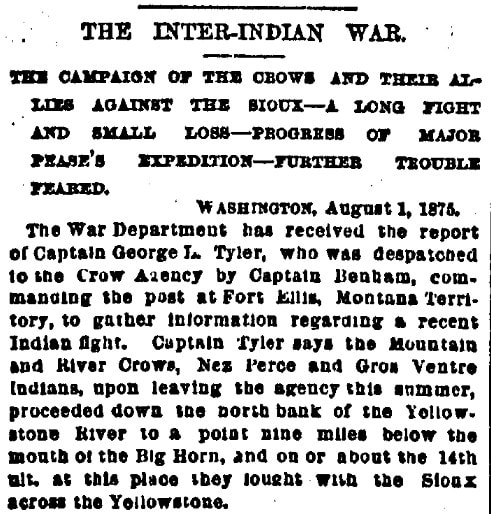

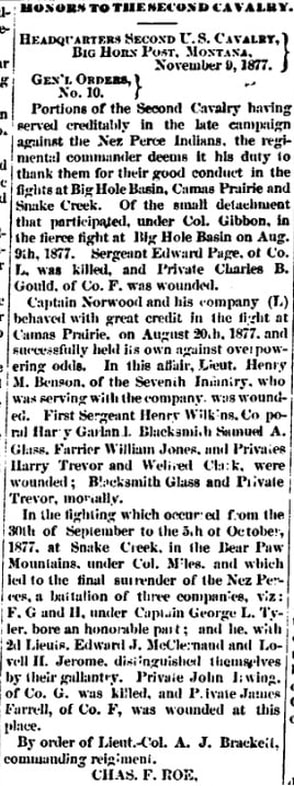

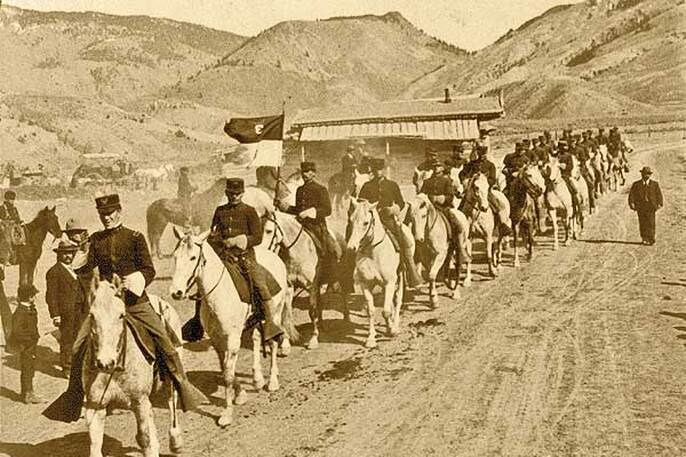

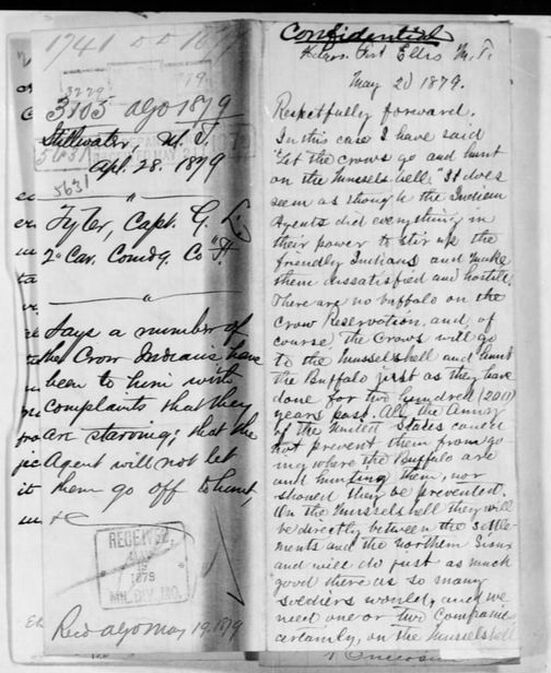

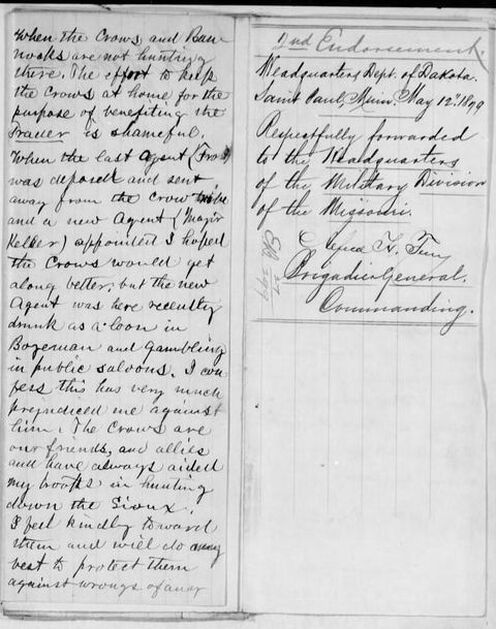

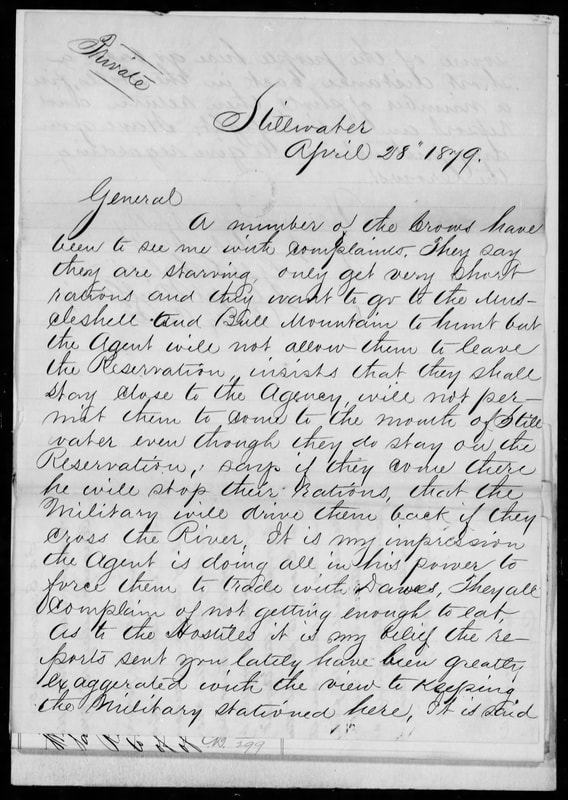

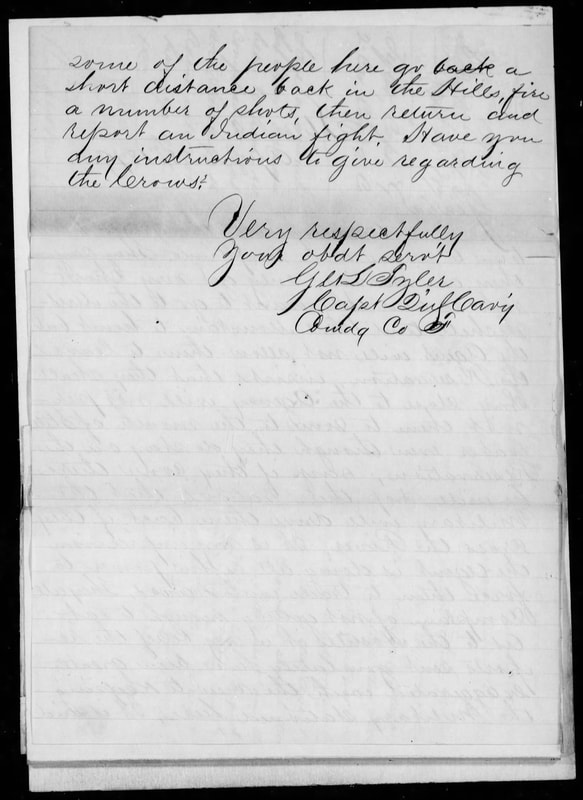

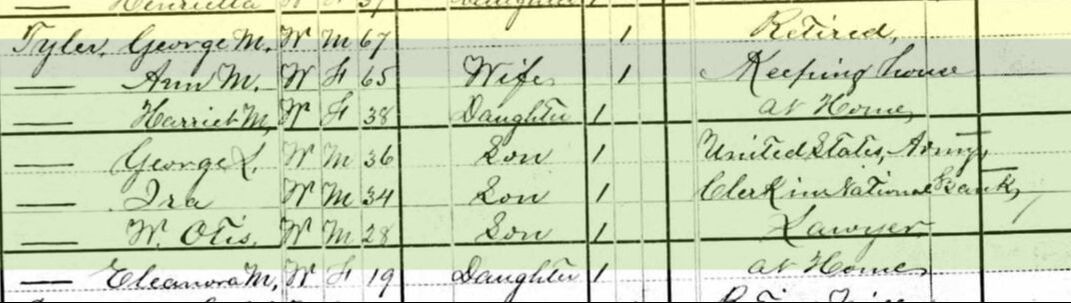

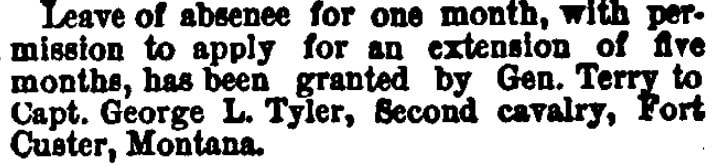

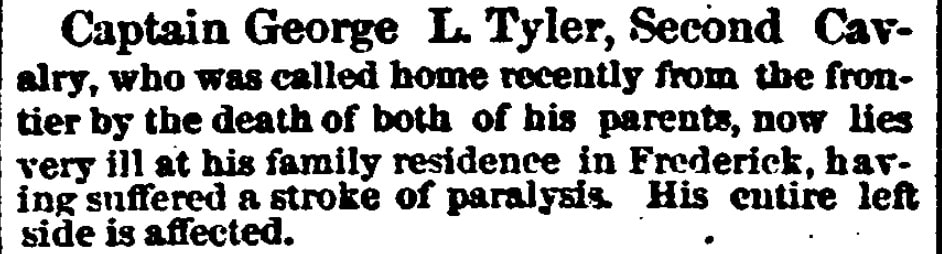

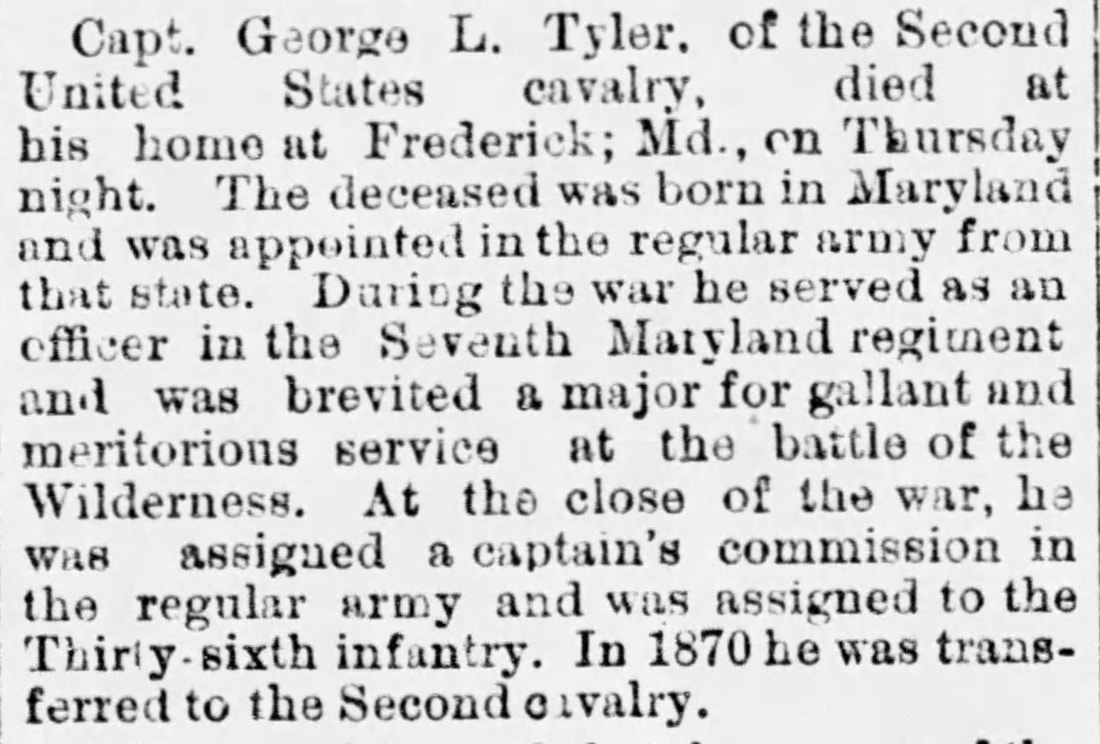

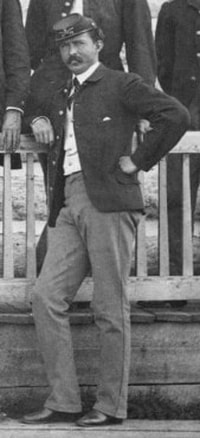

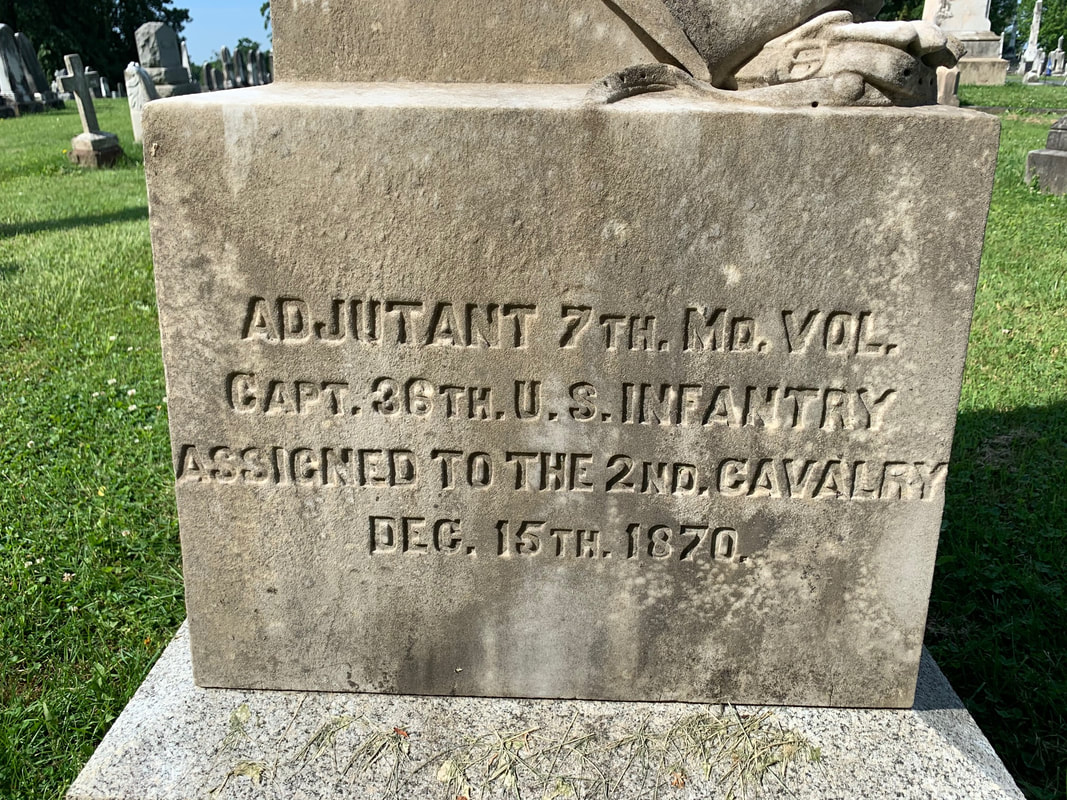

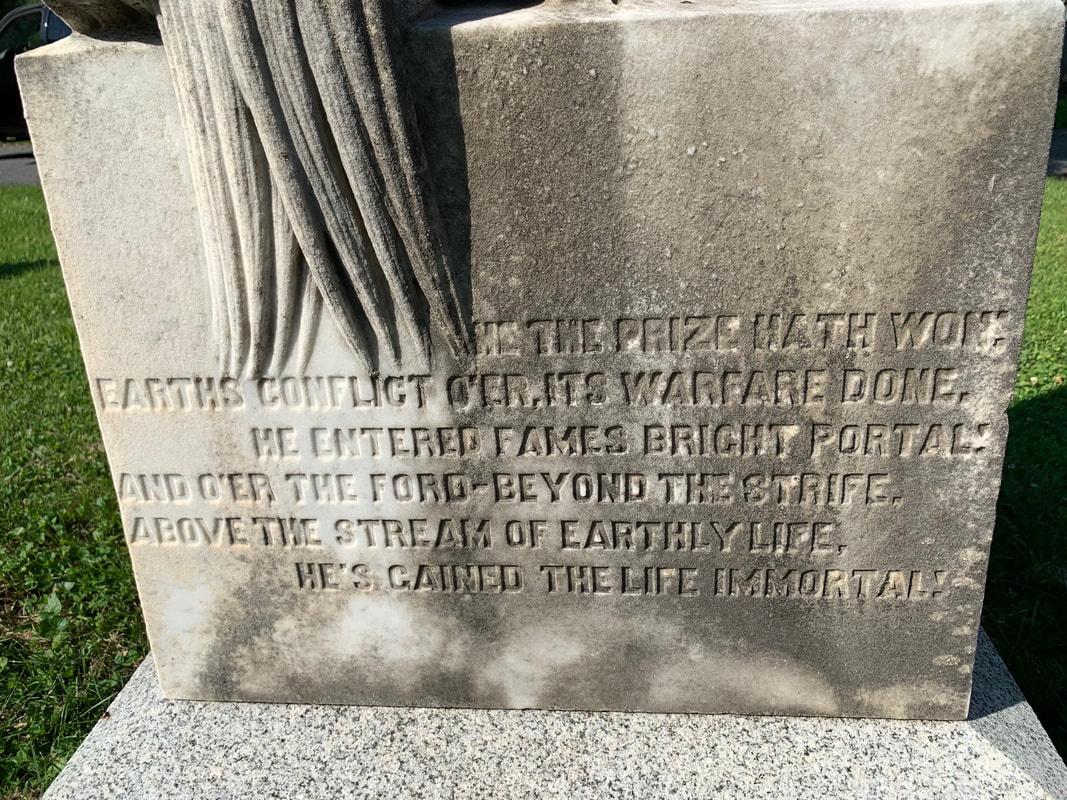

Although it has been on my own personal, radar for years now, I was pleased to find a vintage newspaper article with a mention of a particular, outstanding burial monument here at Mount Olivet, often overlooked. The anecdote can be found within the Sidelights column from the Frederick Post’s edition of August 7th, 1962. The weekly feature highlighted local history and culture with a strong bend toward preservation. “An interesting memorial to Capt. George Late Tyler, 2nd Cavalry USA who died October, 1881, aged 48, has a stone with a column from which is suspended a sword and belt, above the helmet, gloves and spurs.”  The author was reporter Elsie White Haines, a seasoned journalist who started with the Frederick newspaper in the early 1950s. Soon, Ms. Haines had a recurring column on Fridays. She did a great job in bringing historic preservation to the forefront at a time when many old structures here in the city (and county) were being demolished. Her past experience hailed from a similar column written for a newspaper in her native home of Montgomery County. After my impromptu introduction to Ms. Haines (1891-1970) and her artfully-penned writings, I experienced an immediate connection, and also a tinge of guilt and embarrassment because I hadn’t know her name earlier. In addition, I felt regret that Ms. Haines died in 1970, not having the chance to see incredible strides toward preserving so many structures within Frederick's 40-block historic district, not to mention the efforts of the Frederick County Landmarks Foundation in saving buildings such as Schifferstadt and Rose Hill Manor in the immediate decade following her death. If she could see the adaptive re-use mentality in play with local shops, restaurants, and even government and non-profit entities like my old stomping grounds of the Frederick Visitor Center, she would be very proud.  Elsie White Haines (1966) Elsie White Haines (1966) What resonated most with me was a poignant quote that Ms. Haines used to start off a Sidelights column dated June 4th, 1965. This line was attributed to a gentleman named Fred Gebhardt who wrote an article the previous year in DAR Magazine: “Tomorrow is built upon yesterday, Therefore let us save America’s yesterday—today. Let us not wait for tomorrow, For tomorrow might be too late.” Oh, how important and powerful this quote is today, looking back at the activity that saved much in our little town, while the county seat of Ms. Haines home county, Rockville, lost so much of its heritage through historic structures. Ever since I’ve lived here in Frederick (1974), I’ve always heard the expression: “Don’t let happen to Frederick, what happened to Rockville.” I use this brief parlay into Ms. Haines’ life as a grand introduction into my main subject of this week’s “Story in Stone.” This is the decedent buried under the fine monument Ms. Haines described in the above-mentioned passage from 1962--George Late Tyler, a man from a prominent Frederick family who would transition in life from selling sewing machines in 1860, to receiving commendations for gallantry in the Battle of the Wilderness four years later, to fighting Indian tribes in the wild west over the next 17 years until his untimely death in 1881 at the age of 42. George Late Tyler Born February 12th, 1839 in Frederick City, George Late Tyler was one of five children of the marriage union between George Murdoch Tyler and Ann Maria “Mary” Late. George Late Tyler’s grandfather was Dr. William Bradley Tyler (1788-1863), a prominent physician. Dr. Tyler, the son of an English immigrant, made his way to Frederick in 1814 from his native Prince Georges County after stints in Baltimore and Leesburg, VA . In addition to medicine, he served as clerk of the county court and would serve in politics on the local and state level including a run for governor in 1825. George’s namesake father was a merchant of shoes and boots here in town, with a shop located at in the first block of North Market Street on the west side of the street. The family lived next door his father, Dr. Tyler, on Record Street. Our subject attended local school for his early education. He didn’t have far to go, as he attended the Old Frederick Academy located across Record Street from his home. A few of his classmates included future military men who would make names for themselves in the coming American Civil War. Two of these were Alexander Swift “Sandie” Pendleton, son of All Saints Church rector William N. Pendleton who would serve as the youngest officer on Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s staff; and Winfield Scott Schley, who went on to the Naval Academy in Annapolis and participated in the Vicksburg Campaign. George, himself, and brother Ira, would serve in the Civil War under the Union flag. The Tyler family, however, was one of those families that was split in allegiance. George’s paternal uncle, local lawyer Bradley Tyler Johnson, would serve as Maryland’s highest-ranking Rebel, promoted to brigadier general and responsible for commanding the 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA. Frederick history buffs in the know may recall that Dr. William B. Tyler owned slaves, but was also a major Union supporter who hosted President Abraham Lincoln for a meal in his home on Lincoln’s brief visit to town on October 4th, 1862. More confusion from the war that featured Southerners (including many Confederate soldiers) that didn’t believe in slavery and thought their rights were being trampled by a “collusion of northern states,” and die-hard Unionists in the north who maintained slaves, somehow convinced that it was their right within the Union, which it was in border states. So complicated, even for seasoned historians like myself to attempt to comprehend. George Late Tyler’s life would be defined by the United States military, hence the gravestone depicting this fact. Before I get to that history, let me “sew” some seeds of what his life may have been had the American Civil War not come about. As would be expected, George worked as a clerk in his father’s store, with the intent of taking over the business one day, or at the least breaking off with his own. In 1860, an article in the Frederick Examiner newspaper talks of 21-year old George as Frederick’s agent for a newfangled invention that would help define the industrial revolution. The first sewing machine to combine all the disparate elements of the previous half-century of innovation into the modern sewing machine was the device built by English inventor John Fisher in 1844, a little earlier than the very similar machines built by Isaac Merritt Singer in 1851, and the lesser known Elias Howe, in 1845. However, due to the botched filing of Fisher's patent at the Patent Office, he did not receive due recognition for the modern sewing machine in the legal disputations of priority with Singer, and Singer reaped the benefits of the patent. Meanwhile, a man named Allen B. Wilson developed a shuttle that reciprocated in a short arc, which was an improvement over the sewing machines of Singer and Howe. However, John Bradshaw had patented a similar device and threatened to sue, so Wilson decided to try a new method. He went into partnership with Nathaniel Wheeler to produce a machine with a rotary hook instead of a shuttle. This was far quieter and smoother than other methods, with the result that the Wheeler & Wilson Company produced more machines in the 1850s and 1860s than any other manufacturer. Wilson also invented the four-motion feed mechanism that is still used on every sewing machine today. This had a forward, down, back and up motion, which drew the cloth through in an even and smooth motion.  George Late Tyler was on the cutting edge and likely the apple of local seamstresses’ eyes—sales were booming. But there was an ugly side to the business. Throughout the 1850s, more and more companies were being formed, each trying to sue the others for patent infringement. This triggered something known as “the Sewing Machine War.” A former law student at George Mason School of Law wrote the following in a 2009 research paper: “The invention and incredible commercial success of the sewing machine is a striking account of early American technological, commercial, and legal ingenuity, which heralds important empirical lessons for how patent thicket theory is understood and applied today.” In 1856, the Sewing Machine Combination was formed, consisting of Singer, Howe, Wheeler, Wilson, and Grover and Baker. These four companies pooled their patents, with the result that all other manufacturers had to obtain a license for $15 per machine. This lasted until 1877 when the last patent expired. The winds of another war swept up George. He joined the ranks of the 4th regiment of the Potomac Home Brigade. An effort had been made to raise this outfit during the winter of 1861-62. Only three companies (A, B & C) were organized for a term of enlistment for three years. Company “A” was raised in Hagerstown, Company “B” in Baltimore, and Company “C” in Frederick County. Initially these three companies were assigned to guard duty along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, between Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg.  A S Pendleton A S Pendleton On August 11th, 1862 George L. Tyler’s company was incorporated into the ranks of the 3rd Potomac Home Brigade. This infantry outfit was also assigned to duty as railroad guard on Upper Potomac in Maryland and Virginia. Less than a month later, the war came to Frederick as Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Confederate troops camped in and around Frederick City from September 5-10th. The invaders (or liberators for some families) headed west and were eventually engaged by the Union Army at South Mountain and Sharpsburg (Battle of Antietam). George L. Tyler participated in the Rebel siege of nearby Harper's Ferry with the Battle for Maryland Heights (September 12th-15th) led by Gen. Stonewall Jackson with help from Tyler’s old schoolmate, Sandie Pendleton. The Potomac Home Brigade’s 3rd Regiment surrendered on September 15th. They were paroled September 16th and sent to Annapolis. George would be transferred into Company F of Maryland’s 7th Volunteer Infantry unit and was promoted to the rank of adjutant. For those not familiar with this rank, an “adjutant” is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in army unit. I’m thinking there was some “family pull” somewhere that got these guys into higher-end duties. Meanwhile, around this same time, George’s younger brother, Ira, would be commissioned a 1st lieutenant in the 6th Maryland Volunteer Infantry. As for the 7th Maryland, who had served guard duty in the defenses of Washington, the regiment was sent to the Shenandoah Valley for operations. Their first combat came on March 13, 1863, when they repulsed a charge by the 5th Virginia Infantry regiment. They were sent to V Corps, Army of the Potomac. At the Battle of Gettysburg, they were forced to withdraw from the Peach Orchard early on the second day. They were among the units who repelled Pickett's charge. The unit was stationed for garrison duty in southern Pennsylvania and was involved in skirmishes against some of Confederate Gen. Jubal Early's infantry units. George Tyler would participate in the Battle of the Wilderness, fought May 5th–7th, 1864, the first battle of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army. Both armies suffered heavy casualties, around 5,000 men killed in total, a harbinger of a bloody war of attrition by Grant against Lee's army and, eventually, the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. The battle was tactically inconclusive, as Grant disengaged and continued his offensive. Tyler would suffer a gunshot wound that would severely injure his right hip while in combat at the Battle of the Wilderness. He would later be breveted captain for gallantry and meritorious service. Tyler would return home to Frederick to recuperate from his injury immediately after it occurred in May, 1864. Some muster rolls report him at the at the General Hospital created here, but I assume he was nursed back to health in the comfort of his home. Tyler was here that summer, particularly in early July, 1864, the time of Jubal Early’s infamous raid and ransom on Frederick, culminating with the nearby Battle of Monocacy. In November of 1864, Tyler was still hospitalized as a result of his wounds from Wilderness. He was suffering from necrosis of his right femur and obtained a Surgeon's Certificate from famed Union Army physician Robert F. Weir saying he was unfit for further duty during the war. Less than two years after leaving the ranks of the military, George L. Tyler would accept a commission as captain in the 36th US Infantry. Tyler would go unassigned during reorganization of the army in 1869. Late in 1870, he was appointed to the Second Cavalry, and was a member of F Troop. He would soon make his way west to the Montana Territory and Fort Ellis located at today's Bozeman, Montana. The story of the US Cavalry in the west is not a pretty history in hindsight, however, it is our unblemished history, nonetheless. Here are some highlights of the unit’s major activity during the decade: On 23 January 1870, elements of Companies F, G, H, and L participated in the Marias Massacre in the Montana Territory, where 200 Piegan Blackfeet Indians were killed. After this massacre, Federal Indian policy changed under President Grant, and more peaceful solutions were sought. On 15 May 1870, SGT Patrick James Leonard was leading a party of 4 other troopers from C Company along the Little Blue River in Nebraska attempting to locate stray horses. A band of 50 Indians surrounded this detachment and the men raced for cover and made a fortified position with their two dead horses. One trooper, PVT Thomas Hubbard, was wounded, but they managed to hold the Indians at bay and inflicted several casualties. When the hostile band retreated after an hour of fighting, the troopers left, took a settler family under their charge and returned safely. All 5 men were awarded the Medal of Honor (SGT Patrick J. Leonard, and PVTs Heth Canfield, Michael Himmelsback, Thomas Hubbard, and George W. Thompson). Today, junior NCOs in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment compete for the Sergeant Patrick James Leonard award. On 17 March 1876, troopers from Companies E, I, and K (156 men) joined the 3rd US Cavalry Regiment under COL Joseph J. Reynolds to combat the Cheyenne and Lakota in the ill-fated Big Horn Expedition. During the Battle of Powder River, the cavalrymen attacked, but were repulsed, and the 2nd Cavalry lost 1 man killed and 5 wounded. 66 men also suffered from frostbite. The 2nd Cavalry was once again repulsed by the Cheyenne and Lakota at the Battle of the Rosebud on 17 June 1876, and only a few days later, Custer's 7th Cavalry were defeated at the Battle of Little Bighorn. By April 1877, most of the US cavalry was in the west, fighting against bands of hostile Indians. The Cheyenne surrendered in December, Sitting Bull escaped to Canada, and Crazy Horse, the victorious chief in the Battles of the Rosebud and Little Bighorn, surrendered in April 1878. Chief Lame Deer was one of the last Lakota war-chiefs left resisting the US Government. The "Montana Battalion" of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment eventually caught up with his band near the Little Muddy Creek, Montana on 6 May 1878. After a midnight march, the troopers surprised Lame Deer's warriors at dawn on 7 May. H Company charged the village and scattered the enemy horses, while the remaining troopers charged and routed the band of Lakota. During the intense battle, PVT William Leonard of L Company became isolated, and defended his position behind a large rock for two hours before he was rescued by his comrades. He, and PVT Samuel D. Phillips of H Company both earned the Medal of Honor for their gallantry in this battle. While searching the ruined village, the troopers found many uniforms, guidons, and weapons from the 7th Cavalry Regiment, and they left knowing that they had avenged those fallen at Little Bighorn  At the 10-year memorial of the Battle of Little Bighorn, unidentified Lakota Sioux dance in commemoration of their victory over the United States 7th Cavalry Regiment (under General George Custer), Montana, 1886. The photograph was taken by S.T. Fansler, at the battlefield’s dedication ceremony as a national monument. On 20 August 1877, elements of the 2nd Cavalry which had been pursuing Chief Joseph's band of Nez Perce Indians through Idaho reported that their quarry had turned on them, stole their pack train, and began attempting to escape to Canada. Despite being low on supplies, L Troop and two additional Troops of the 1st Cavalry were dispatched to retrieve the pack train. After a hard ride, the Indians were overtaken and a fierce battle ensued. CPL Harry Garland, wounded and unable to stand, continued to direct his men in the battle until the Indians withdrew. For his actions, he would receive the Medal of Honor along with three other men from L Troop; 1SG Henry Wilkens, PVT Clark, and Farrier William H. Jones. Today, the annual award for the most outstanding trooper in the 2nd Cavalry is called the Farrier Jones Award. On 18 September, a force of 600 men under General Oliver Otis Howard and Colonel Nelson A. Miles, including Troops F, G, and H of the 2nd Cavalry, marched to stop Chief Joseph's band from reaching Canada. L Troop was sent back to Fort Ellis to gather supplies but would join the expedition later. On 30 September 1877, the Battle of Bear Paw Mountain began. The three Troops of 2nd Cavalry were dispatched to drive away the Indians' ponies by attacking their rear. G Troop, under LT Edward John McClernand, caught up with Chief White Bird as he and his band tried to escape to Canada. The ensuing engagement was brief, but violent, and resulted in the capture of the Indians and their mounts. Lt McClernand was awarded the Medal of Honor for his gallantry. After a four-day siege, Chief Joseph surrendered his band to General Howard on 4 October 1877. The following newspaper article praises Capt. George L. Tyler "who bore an honorable part." In the fall of 1878, the 2nd Cavalry was posted in two forts in Montana; Fort Custer and Fort Keogh with the mission of preventing Chief Sitting Bull from returning to US territory after escaping to Canada. In early winter, Chiefs Dull Knife and Little Wolf left their reservations in Oklahoma and began moving northwards. Dull Knife was intercepted and surrendered at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, but Little Wolf sought shelter in the Sand Hills of Wyoming. Elements of E and I Troop under LT William P. Clark (who had earned a special rapport with the Indians) were sent to negotiate with these stalwarts. The band was located near Box Elder Creek, Montana on 25 March 1879, and was persuaded to accompany the troopers back to Fort Keogh. During the march back, on 5 April, several Indians escaped and attacked the soldiers. SGT T.B. Glover took 10 men of B Troop and charged the numerically superior enemy, forcing them to surrender, and SGT Glover received the Medal of Honor for this action. Chief Little Wolf eventually surrendered his band when the party returned to Fort Keogh. (NOTE: The above info came from editor Chris Golden’s "History, Customs, and Traditions of the "Second Dragoons" (2011). On the Fold3 website, I was lucky enough to find several military records on George Late Tyler. Specifically, I was fascinated with source documents held by the National Archives in the form of letter correspondence between Capt. Tyler and the commandant of Fort Ellis (Montana) in April, 1879. The content of these materials consisted of complaints made by the Crow Indians and "sundry charges" against their assigned Indian Agent liaison (assigned by the federal government). It seems Capt. Tyler worked to assist this tribe by writing a confidential letter to his superior, calling out said agent. These concerns, as presented by Capt. Tyler, would be forwarded to the Department of the Interior's Office of Indian Affairs and the War Department. Tyler would be commended for this action. Below are pages from Tyler's personal notebook from his interview with the Crow tribe, and the letter he penned to Washington, DC: The summer of 1880 featured another trip home to Frederick by George L. Tyler. I don't know how his military leave worked, or whether his trips back home were add-ons to visits to superiors in Washington. Regardless, he can be found in Frederick within the 1880 US Census.

George Late Tyler died in town on October 20th, 1881. He was buried in the Tyler family lot in Area E/Lot 184. A remarkable monument was erected in his honor--a true masterpiece.

1 Comment

Nancy Droneburg

6/19/2020 11:31:16 am

Wonderful

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed