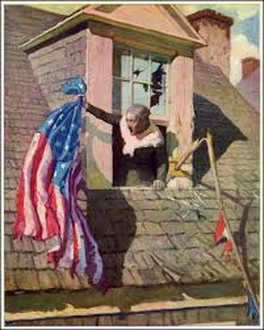

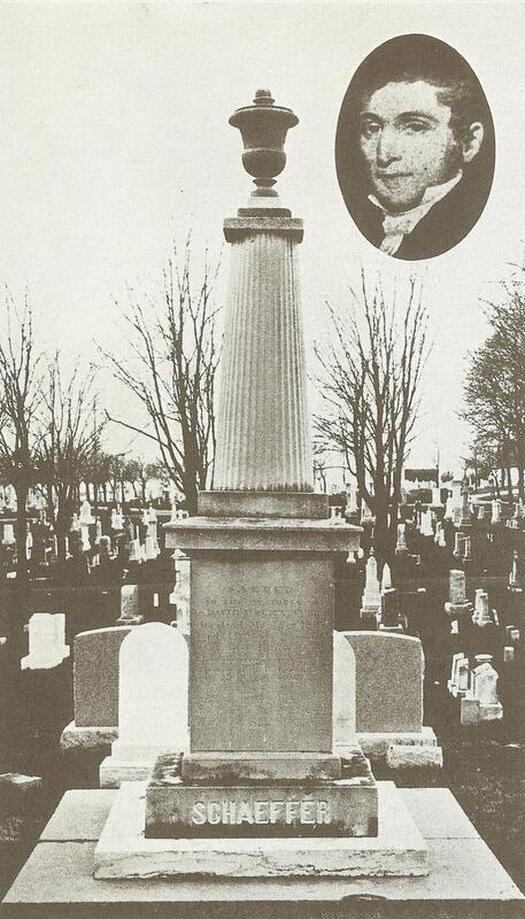

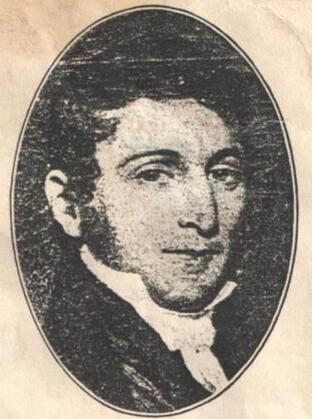

“Listen, my children, and you shall hear Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five: Hardly a man is now alive Who remembers that famous day and year. He said to his friend, “If the British march By land or sea from the town to-night, Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry-arch Of the North-Church-tower, as a signal-light,– One if by land, and two if by sea; And I on the opposite shore will be, Ready to ride and spread the alarm Through every Middlesex village and farm, For the country-folk to be up and to arm. Many of us grew up with this poem, the work of fireside poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow more than a century and a half ago. But, does anyone know of an impressive “ride” that occurred here in Frederick, Maryland on the twenty-fifth of August, in 1814? “Paul Revere’s Ride” was written in 1860 on the eve of the American Civil War, first appearing in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine. Interestingly, and possibly by design, a friend and fellow poet from Massachusetts named John Greenleaf Whittier would have a similar work published in The Atlantic just three years later. As Longfellow made a household name out of Boston silversmith Paul Revere, Whittier did the same with a former resident of our fair city of Frederick—her name was Barbara Fritchie. However, in both cases, fame did not come to either subject until after their respective deaths. A bit of embellishment had been employed. You see, there is this thing called “poetic license,” which is defined as: the freedom to depart from the facts of a matter or from the conventional rules of language when speaking or writing in order to create an effect. And who best to demonstrate poetic license than Longfellow and Whittier—poets themselves!  William Dawes, Jr. William Dawes, Jr. Sadly, two other individuals, William Dawes, Jr. (1745-1799) of Boston and Mary Quantrill (1824-1879) of Frederick, never made the history books, while their counterparts have been “revered” for over a century and a half. Thanks again go to Wadsworth and Whittier. Hey, I just want to make it clear that I’m not here to challenge the patriotism of Paul or Barbara. Mr. Revere demonstrated his loyalty to the Sons of Liberty, and Dame Fritchie to the Union. Both poems (“Paul Revere’s Ride” and “The Ballad of Barbara Frietchie” made major impacts on our cultural identity as a country and explore the spirit of the civilian population in respect to our American Revolution and Civil War.  Today, Barbara Fritchie rests in peace within the confines of Mount Olivet, her grave topped by an impressive monument with Whittier’s poem etched on a bronze tablet. Nearly 80 or so yards to the north is another impressive monument marking the gravesite that of a local minister that old Dame Fritchie surely knew. He did not preach at her particular church (German Reformed), but was instead connected to Frederick’s Lutheran congregation. His name was David Frederick Schaeffer. Although this name doesn’t conjure up patriotism and the vision of flag-waving among lifelong Fredericktonians, one could make the case that Rev. Schaeffer could be considered our town’s “Paul Revere.” Rev. Schaeffer David Frederick Schaeffer was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania on July 22nd, 1787. His parents were Frederick David Schaeffer and Rosina Rosenmiller, both German immigrants. His father was a Lutheran clergyman, as were his brothers Frederick Christian, Charles Frederick, and Frederick Solomon. As you can see, this family had a penchant for “Frederick,” through and through! By the way, I recently learned that the name Frederick is said to mean “peaceful.” Our subject spent much of his youth in Germantown, PA, once located northwest of Philadelphia, but today encompassed by “the City of Brotherly Love.” David graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1807, where he studied theology with Justus Henry Christian Helmuth, John Frederick Schmidt, and his own father. Young Schaeffer was ordained by the Pennsylvania Ministerium in 1812, although he had received his license to preach earlier in 1808. On July 17th of that same year (of 1808), Schaeffer became pastor of Frederick, Maryland’s Evangelical Lutheran congregation. Five days after his arrival, he would celebrate his 21st birthday.  The young minister came into a situation in which the congregation, for the most part, had experienced an adversarial relationship with their former, permanent pastor, a Rev. Frederick William Jaminsky. Jaminsky served from 1802 until July, 1807 at which time he honorably resigned his charge. An illustration of Schaeffer’s pastorate in Frederick can be gleaned from a book titled “A History of the Evangelical Lutheran Church: 250 years 1738-1988,” written by Abdel Ross Wentz and Francis E. Reinberger: If the Synod could now fill its own order and supply Frederick with a “peace-loving and capable pious pastor” there was every reason to expect that the church would share that enthusiasm for progress that was now beginning to mark the American nation as a whole and to lead it out into larger undertakings in the name of Jehovah….The period of waiting was over. The time of short pastorates was past. A long constructive period. The Frederick church, like the nation in general, was about to enter upon a new stage of its history. This new era in the life of the American nation covered the first forty years in the nineteenth century. It was marked by the rapid growth of patriotism and the national spirit. It severed the bonds that tied the Americans to their European masters, and it gave them independence in fact as the Revolutionary War had given them independence in name. This development of a new American culture applied not only to politics but to the religious and intellectual life as well. It enlarged the vision of individual Christians and it pushed back the horizons of the Churches as bodies. It led the Churches to face squarely the vast practical Christian tasks presented by the sudden territorial expansion and rapid numerical growth of the nation. This new temper of the times helps explain the general trend of events in the Frederick Lutheran Church during the period.” Rev. Schaeffer would prove a perfect match for the town, and county, that shared his middle name. He is said to have “entered his field with enthusiasm,” and possessed “an attractive personality, for he was well educated, trained in the courtesies and properties of life, tall and sturdy. His clear strong voice was a special asset in the pulpit. He had the dignified bearing of a clergyman and the natural grace of a gentleman. Even in his youth he never lacked poise. His unfailing kindliness of disposition attracted to him people of all stations and ages.” One such who was attracted to Rev. Schaeffer was Elizabeth Krebs of Philadelphia, whom he married in the year 1810. The couple would go on to have six children.

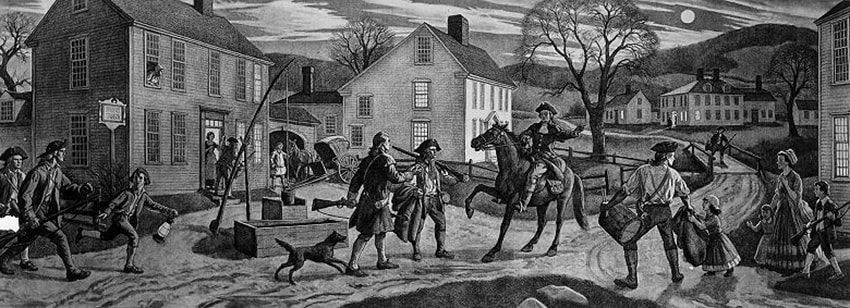

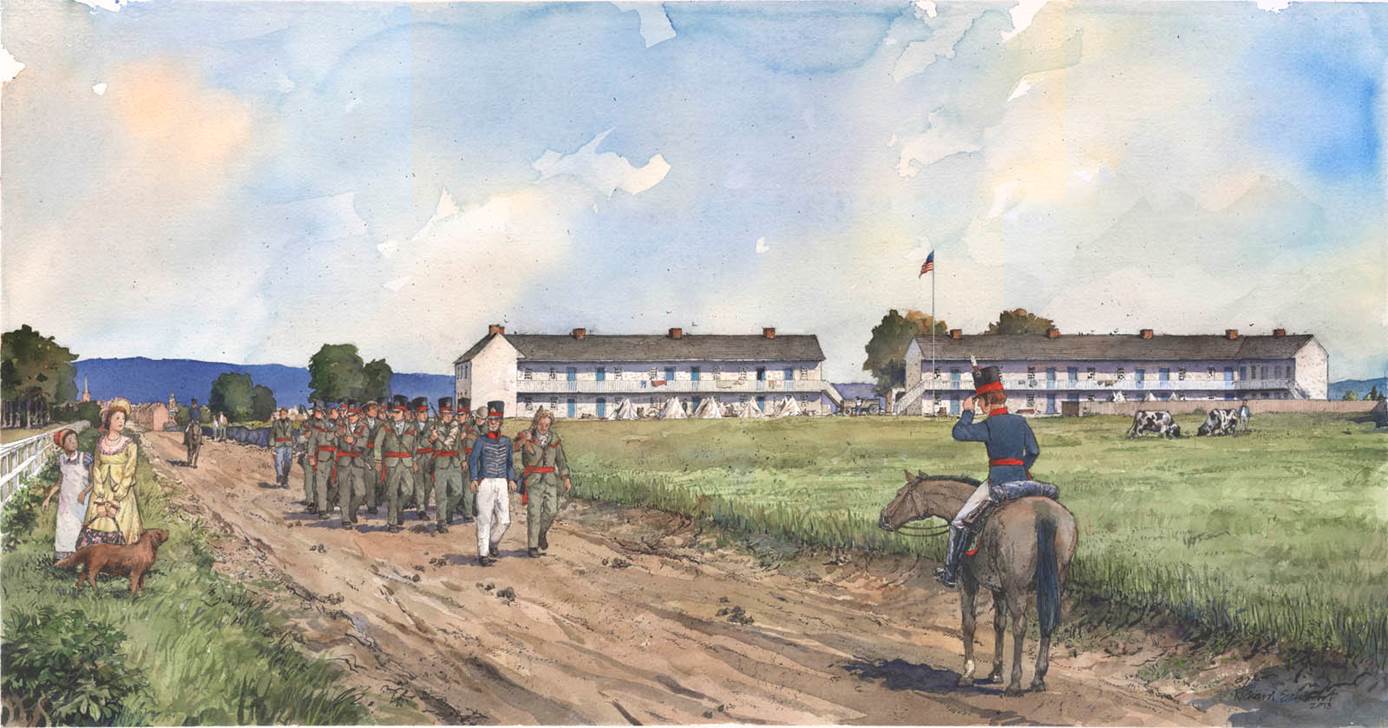

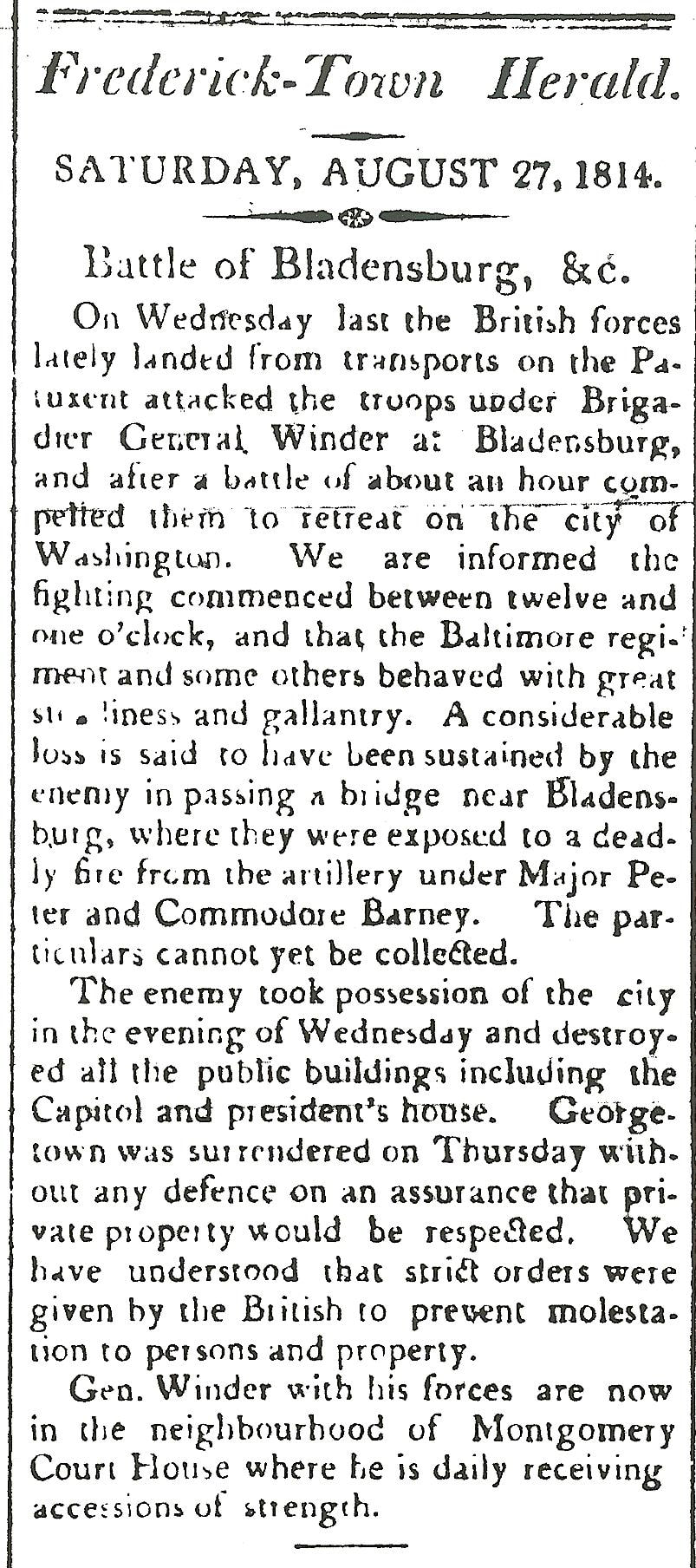

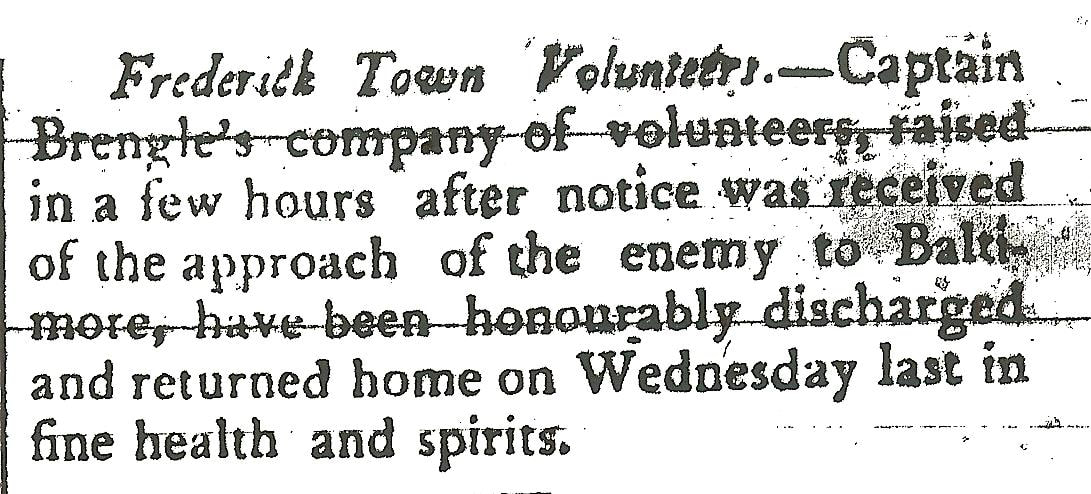

“The Perilous Fight” The winds of war were swirling shortly after David Schaeffer’s arrival here in Frederick. Great Britain was certainly “stirring the pot” of antagonism, but no one anticipated the fact that things would eventually escalate into a "Second War of Independence,” lasting from 1812 to 1815. One of the major issues during the first decade of the 19th century featured the practice of "impressment" on the high seas. This involved forcing men to serve in the armed forces through violence. The British Royal Navy vigorously practiced this method of replacing its sailors by taking United States citizens from American ships—not cool. In addition, Britain was also making attempts to limit American trade with France (with whom Britain was currently at war). This caused tensions to eventually boil over into a declaration of war by the United States in June, 1812. Battles between the two countries (and their respective Native-American allies) were primarily fought on the U.S.-Canadian border over the first two years of the war. This included locations such as Detroit and Niagara, as Canada was then a British territory. At least one bright highlight was the capture (and subsequent burning) of the major town of York in Ontario, Canada by US forces. We know this place today as Toronto. All the while, the United States did not have much of a major standing army at the time. Across the country, local men would be asked to comprise companies in an effort to form and bolster state militias. Frederick was no exception, as the Secretary of War demanded that quotas be filled for the defense and protection of major towns such as Baltimore and the state capital of Annapolis in our case. One of our local commanders included Major Ezra Mantz. He, in turn, had two local brothers, part of one of the town’s founding families. Captain Stephen Steiner oversaw a company of infantry and Captain Henry Steiner oversaw a company of artillery. A frequent place of military activity was the Frederick (Hessian) Barracks (today's site of the Maryland School for the Deaf). Here, troops would be mustered and take part in drilling and other training exercises. Outside of that, things were relatively quiet in the mid-Atlantic region and these citizen soldiers had ample opportunity to tend to their crops and respective trades as the war raged on elsewhere. That would all change in early 1814. Napoleon Bonaparte and his French Army would be defeated by spring, allowing the British to turn more of their attention to the United States. In mid-August of 1814, the British sailed up the Chesapeake Bay and disembarked on Maryland’s western shore at Benedict with the goal of capturing Washington, DC. This occurred on August 19th and the entire region was thrown into a full state of alarm and panic as you could imagine. The state militia scrambled to defend the nation’s capital and met the enemy at Bladensburg on Wednesday, August 24th. One such participant was Francis Scott Key, a lawyer who once dreamed of becoming a minister. During the battle, Key was living in Georgetown and served as an aide for the District of Columbia’s militia commander. The Battle of Bladensburg resulted in an embarrassing defeat of American forces under General William Winder. The blunder allowed the British Army to subsequently march into nearby Washington DC and set fire to public buildings, including the presidential mansion (later to be rebuilt and renamed as the White House) and Capitol over August 24th and 25th. Worse yet, this act of war was primarily performed in retaliation for the earlier torching of York (Toronto) by the United States. This had a major effect on American morale as the British had succeeded in destroying the very symbols of American democracy and spirit. At this moment in late August, 1814, the British sought to swiftly end the war, and with it, the “American Independence” that was first declared back on July 4th, 1776. As you can imagine, excitement was heightened here at home when news of the defeat and destruction reached Frederick. Our standing militia companies departed for Bladensburg and Washington on Thursday, August 25th under the leadership of the previously mentioned Capt. Henry Steiner, and another officer named George Washington Ent. Unfortunately, we had no mayor at the time for guidance or moral support as Frederick Town had not quite been incorporated, an event that would occur in 1817. So, you can guess who residents now turned to for guidance and support since our key military leaders were rushing toward the scenes of battle? That’s right—the local clergy. Now 27 years old, Rev. Schaeffer had “commanded” the respect of not only his Lutheran flock, but many other residents of Frederick.  Jacob Engelbrecht Jacob Engelbrecht We can get a feel for the mood of the day from two written accounts—one found in the local newspaper of the day and the other from our esteemed resident/diarist Jacob Engelbrecht, merely a teenager at the time. Englebrecht’s description would not be recorded until 42 years later( June of 1856), but it still provides documented proof of a unique happenstance involving Rev. Schaeffer: “War of 1812. The following is the Muster Roll (copy) of Captain John Brengle’s Company of Volunteers, which Company was raised in four hours, by marching through the streets of Frederick, August 25, 1814, (the day after the Battle of Bladensburg, on which day we received the news) headed by Captain Brengle & by the side, with them, rode the Reverend David F. Schaeffer, encouraging the men to volunteer…” Somewhat like Paul Revere, our Rev. David Frederick Schaeffer helped warn the "masses" that “the British were coming” and moreso urged residents to aid in repulsing this threat to America’s independence. Brengle, a large farm-owner from just east of town, was a seasoned militia veteran and upon hearing the threat to the capital became intent on raising additional men. Rev. Schaeffer is said to have rode alongside the company for three miles on their departure out of town that same day as they headed south on the Old Georgetown Pike. He delivered a parting address and offered a prayer with the soldiers all kneeling. Apparently, Captain Brengle’s Company is said to have encountered a messenger around the present vicinity of Clarksburg who told them that Washington had been lost and that the British were now setting their sights on Baltimore. At that point, Brengle is said to have re-directed his troops eastward. These men would eventually participate in the Battle of Baltimore a few weeks later on September 13th and 14th.  It’s not exactly known why or how John Brengle sought out our Rev. Schaeffer, particularly made more intriguing because the Brengle family was part of the Frederick’s German Reformed congregation. Regardless, the charisma and leadership qualities of the young minister helped result in the official tally of 73 men garnered for the additional local militia company. One final aside is a comical anecdote that Captain John Brengle got caught up in the excitement of the day and failed to notify his family that he had raised a volunteer company, and had even left Frederick for battle. In the bigger picture of “cause and effect,” the US flag, coupled with the relentless bravery shown by Baltimore’s defenders ( made up of Frederick’s own, including men inspired by Rev. Schaeffer), helped give impetus for the writing of a song, often confused to be a poem, by the fore-mentioned Francis Scott Key. The British were thwarted in “Charm City” and our Independence maintained. Rev. Schaeffer had played an interesting part in this drama—and did so as a civilian. The same can be said for FSK at this time, Paul Revere nearly forty years earlier, and Barbara Fritchie 48 years later.

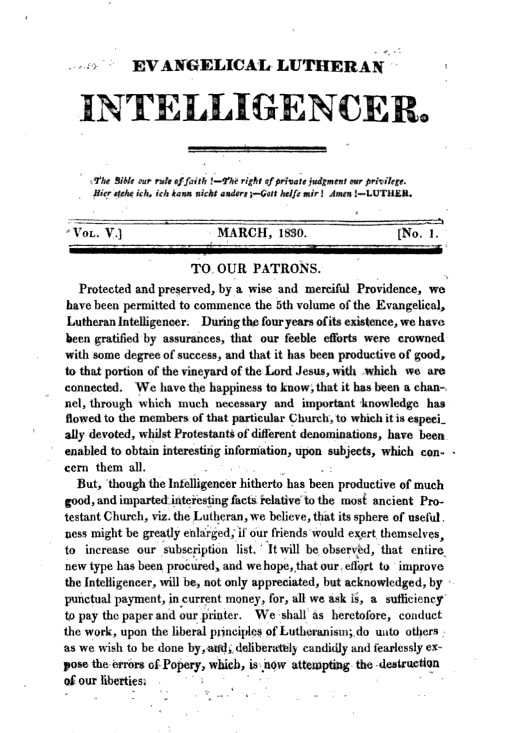

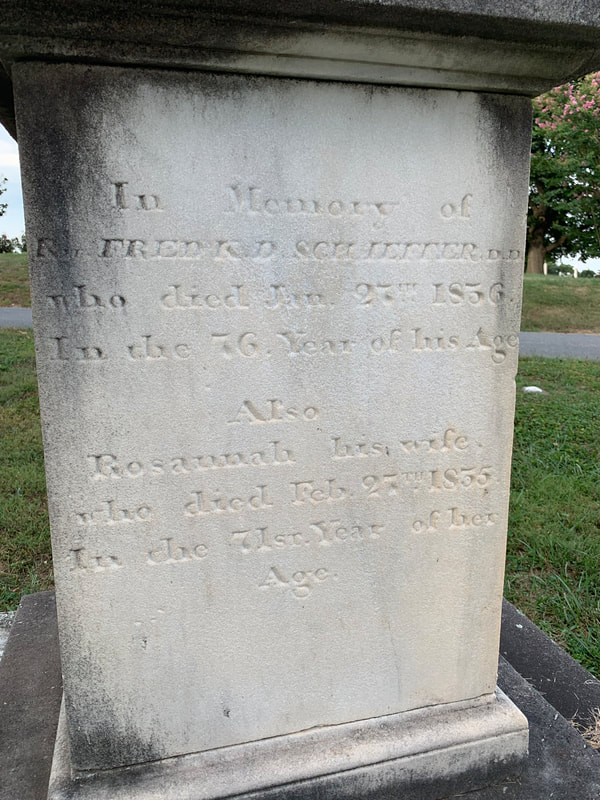

Back to the Pulpit As things returned to a new normal in Frederick, Rev. Schaeffer continued his recruiting ways, but these draftees were men and women intended for church pews, not battle trenches. He had a major goal of gaining more young people, particularly children, into the folds of the church. In 1820, Schaeffer initiated the first Sunday School at Frederick, known as the "Mathenian Association." In 1825, he helped lead a major restoration project to the aging chapel, resulting in the congregation boasting the largest auditorium in town. The timing could not have been any better as the year 1826 marked a very important time of patriotic fervor for not only the country, but Frederick as well—the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1826. Just as he had done twelve years earlier, Rev. Schaeffer rallied the community with his participation and leadership in hosting a commemorative celebration at the newly refurbished (and expanded) church. A newspaper of the day reported the work of the “Great Baby Waker” cannon and related exercises of the day: “The dawn of the day was announced by the thundering voice of the big black war dog who in the year 1783 was brought to Frederick to celebrate the restoration of peace and echo ever since has occupied his lonely station on Barracks Hill. He roused the inhabitants from their slumbers and bade them prepare to celebrate the Jubilee of Freedom. The enlivening strains of the bands of instrumental music stationed in the steeples, which broke upon the ear like a salutation from the celestial spheres; the brisk and animated rattle of the drums with the shrill tones of the fife silenced at intervals for a moment by the thundering peals of artillery together with the gay streamers that flaunted in the breeze, all imparted to the scene an interest such as was suited to the occasion….At an early hour at the east end of Market Street the procession was formed. The procession moved down Market Street, up Patrick Street, through Court Street, and thence to the Evangelical Lutheran Church. On entering the door, the choir sung an anthem suited to the occasion and the ceremonies were commenced by an appropriate address to the Throne of Grace by the Rev. Samuel Helfenstine. Thomas W. Morgan, Esquire, read the Declaration of Independence prefaced by a brief but suitable exordium. He was followed by L. P. W. Balch, Esquire, who pronounced an oration abounding with patriotic and benevolent sentiments.” It was a proud day for all in attendance, as I strongly sense that a 59 year-old local woman named Barbara Fritchie was in attendance, especially based on her strong patriotic leanings. It must have been a proud day for Rev. Schaeffer. From 1826 until 1831 David F. Schaeffer was the editor of the first English-language periodical established in the Lutheran Church in the United States, the Lutheran Intelligencer. Also in 1826, Schaeffer took an active part in the establishment of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The reverend was one of the founders of the General Synod of the Lutheran Church (1821), and served as its secretary from 1821-1829, and its president from 1831-1833. In 1836, Schaeffer received the degree of Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) from St. John's College in Annapolis, MD. Besides a large number of doctrinal and other articles in the Lutheran Intelligencer, he published various addresses and sermons.  It was also in the year 1836 that a major setback occurred, one that involved Rev. Schaeffer feeling the need to resign his post due to health reasons. The congregation was reluctant to let Dr. Schaeffer go, as hope was held out that he would eventually overcome his present situation with rest as the reverend was not even 50 years old at this time. Meanwhile, Schaeffer kept getting unanimously elected by the congregation in votes to fill his vacancy. He repeatedly and respectfully declined, stating that he was significantly ill and the elections were unconstitutional. Finally, his resignation was accepted with deep regret in early 1837. Mrs. Elizabeth Schaeffer would die in February of that year, and her husband would succumb to his maladies on May 5th 1837, one day after the church’s Ascension Day . On the night of the 5th, Jacob Engelbrecht recorded the event for posterity in his diary: “Died this evening about 5 o’clock aged 49 years, 9 months & 13 days, The reverend David Frederick Schaeffer, D.D. Pastor of the Lutheran Church of this place for upwards of 28 years, from 1808 to 1836. He was born (in Germantown, Pennsylvania I believe) “July 22, 1787,” so he told me on the 22nd July 1833.” A month later, Engelbrecht would again mention Rev. Schaeffer in his diary: The funeral sermon of the late Reverend David F. Schaeffer, D.D. was preached yesterday forenoon in the Lutheran Church by the reverend Charles Philip Krauth, one of the professors of the Theological Seminary, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to an over-crowded church. The reverend Doctor Hazelius, now of Salem, North Carolina preached last night in the Lutheran church in the English Language.” (Friday, June 5, 1837 )  Once again, I harken back to the fine history book of Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church written at the time of its 250th anniversary in 1988. The following summation concludes several chapters on Schaeffer’s impact and accomplishments here in Frederick: “Dr. Schaeffer’s life was not a long one if measured in years. But in his ministry, all of it spent in Frederick, was abundant. Even the figures would suggest a great volume of labors and a large harvest. He preached at Frederick about 5,000 sermons, baptized over 2,000 infants, catechized and confirmed about 1,400 people, married about 2,000 couples and conducted 1,600 funeral services.” Rev. Schaeffer was buried in the congregational cemetery, once located at the southeast corner of East Church and East streets. Today, the site is marked by Everedy Square. His remains once rested alongside those of his wife under the shadow of a fine monument erected by the congregation. Also in this grave plot, were buried his esteemed father and dutiful mother who had both died within the preceding two years. In the early 1900’s, Rev. Schaeffer, his wife and parents were moved to Mount Olivet along with the impressive monument. This likely occurred in 1903 at the time of death of Schaeffer’s daughter Caroline 1827-1903). The eternal resting place of these exceptional early leaders of the Lutheran Church in Frederick (and abroad) is located in Area Q/Lot 10. In case you were curious, the Evangelical Lutheran Church eventually sold the land that constituted their second burying ground, causing the majority of the inhabitants to be transferred here to Mount Olivet. The good reverend’s name lives on as part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church campus. Fronting on E. 2nd Street, a new Sunday School building was constructed in 1891 and carries the name the Schaeffer Center. Within the adjacent church, two windows (on the east side) are memorials to the Rev. David Frederick Schaeffer, D.D. and feature Martin Luther and St. Paul. These were placed here in 1924 by grandson, Mr. George Frederick Hane, of Washington, DC.

2 Comments

Hollis Thoms

8/25/2019 06:58:35 am

Very interesting and very detailed account. Enjoyed reading this. Have read Engelbrecht's diary and seen the original at the Frederick Historical Society.

Reply

shane shanholtz

8/28/2019 08:56:32 pm

great story as always

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed