|

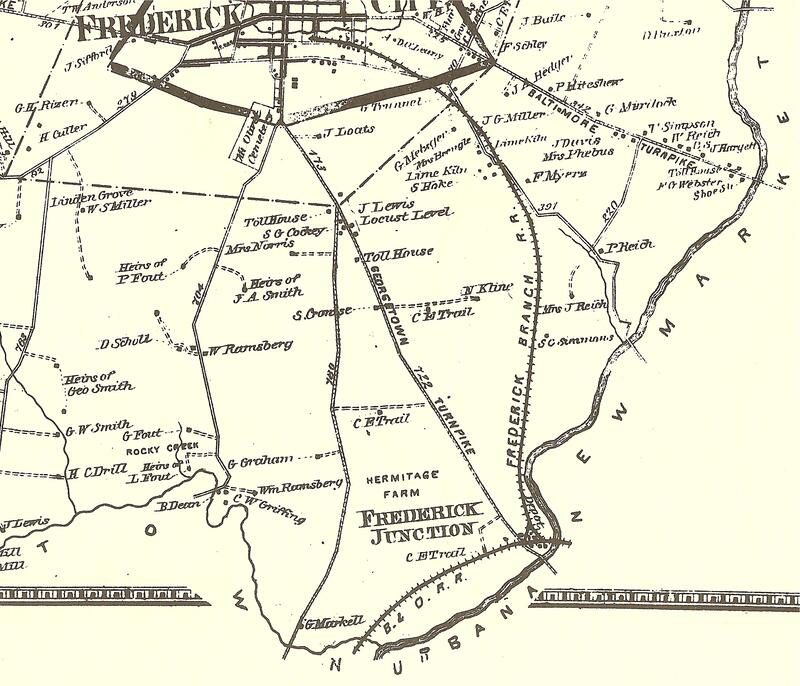

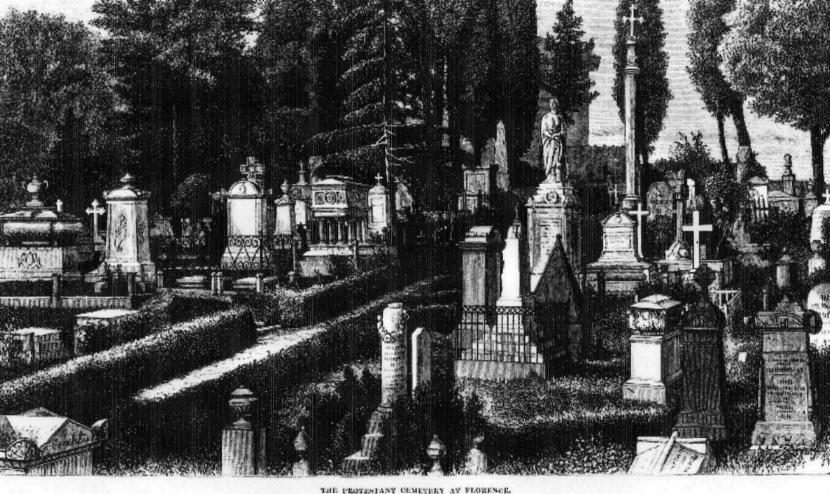

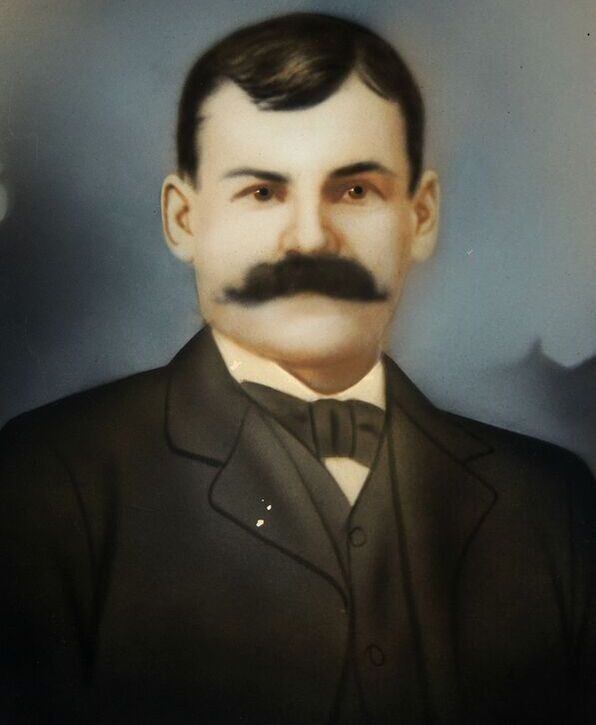

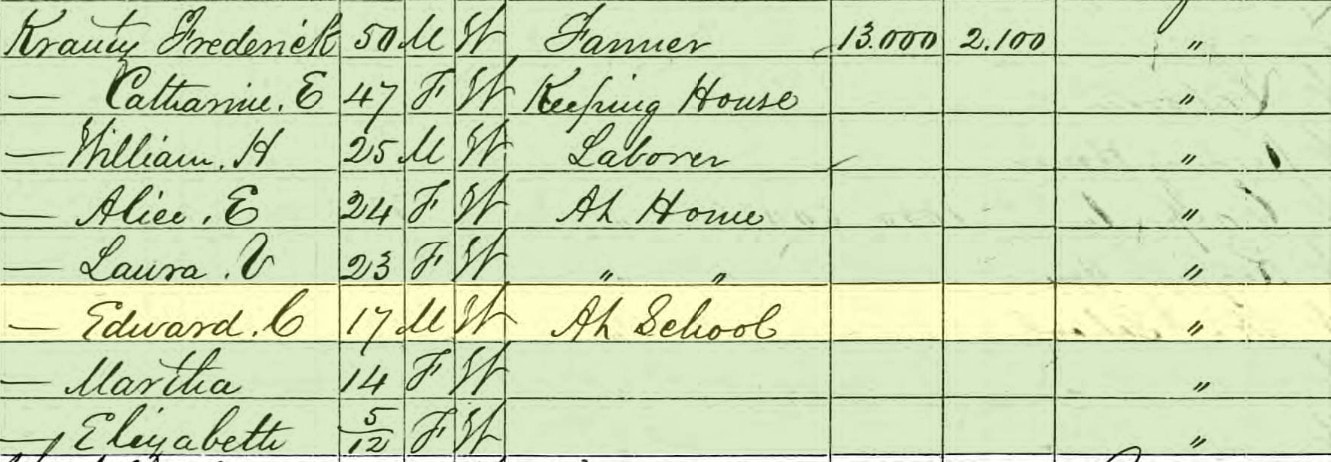

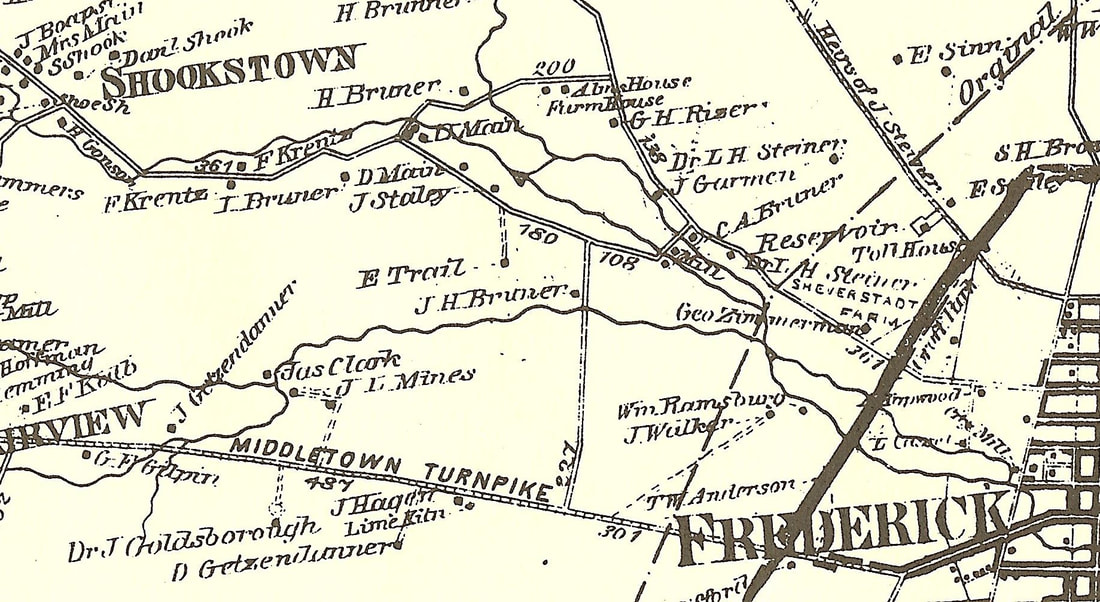

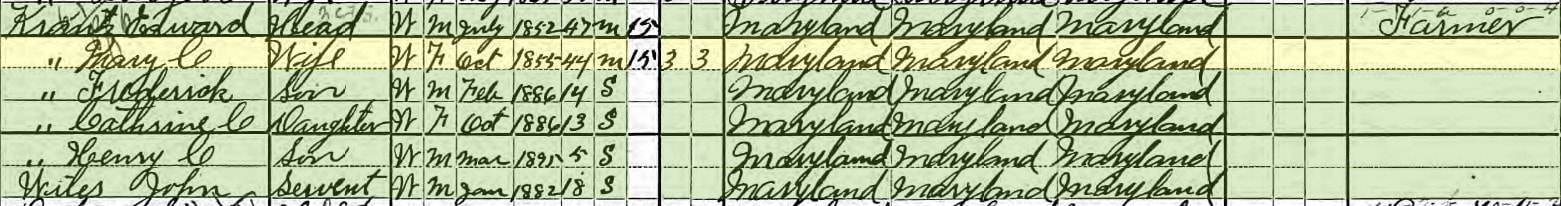

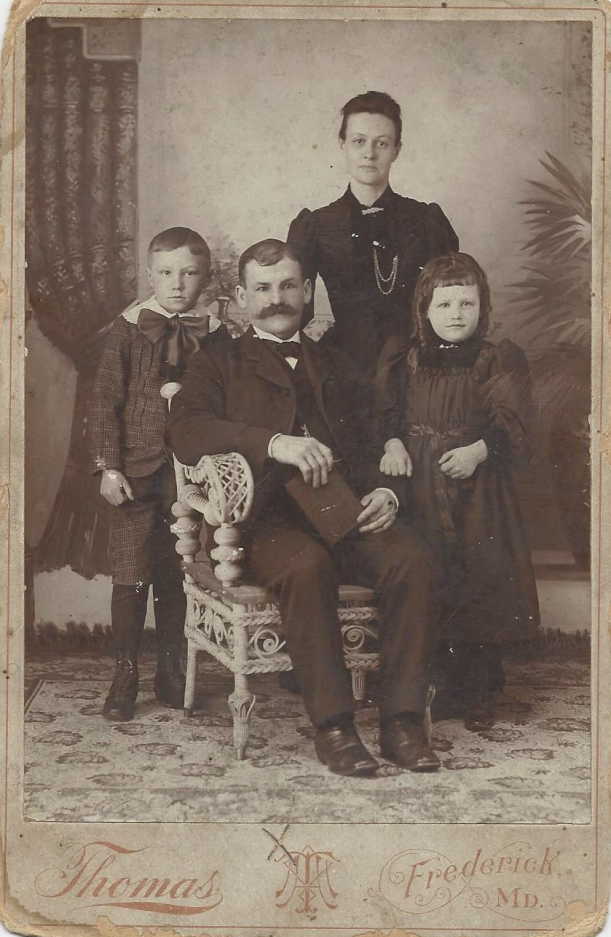

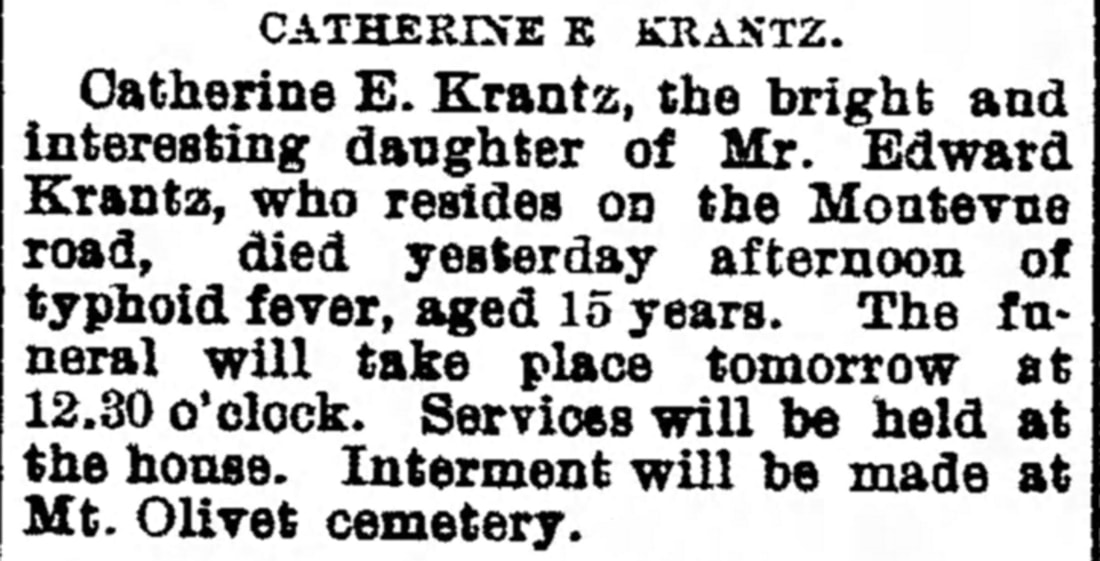

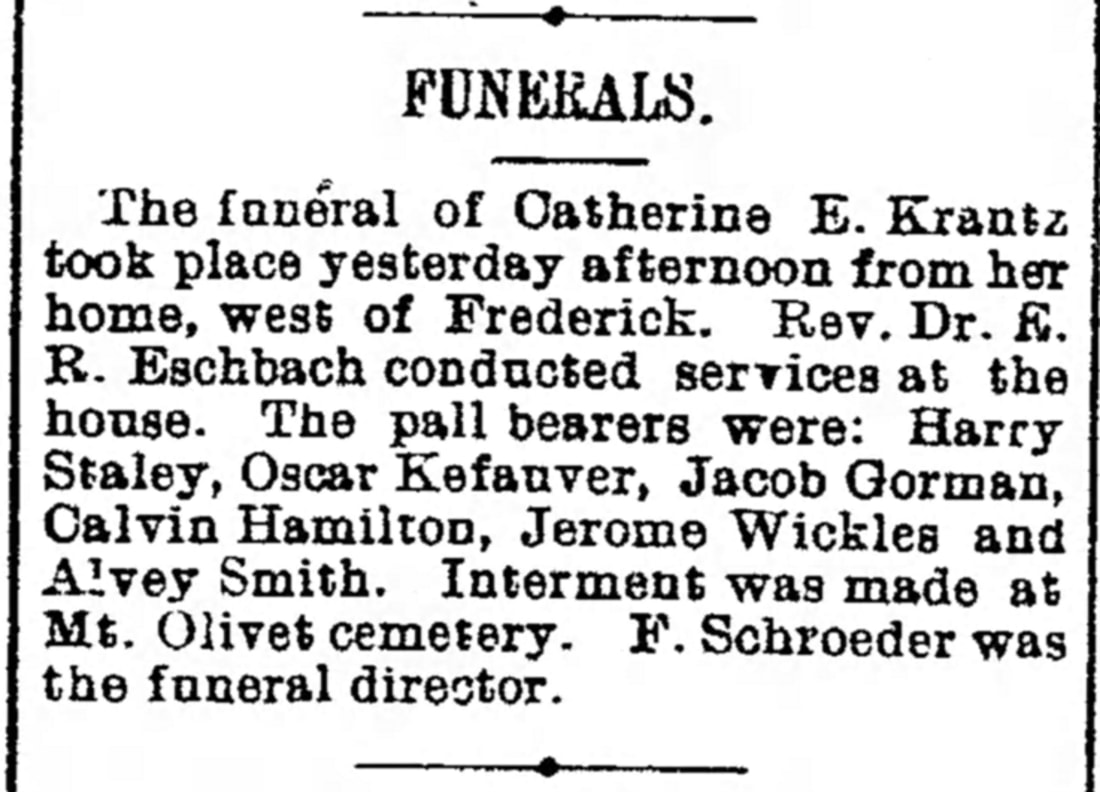

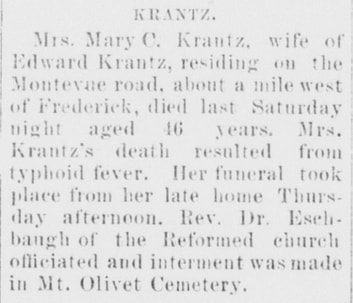

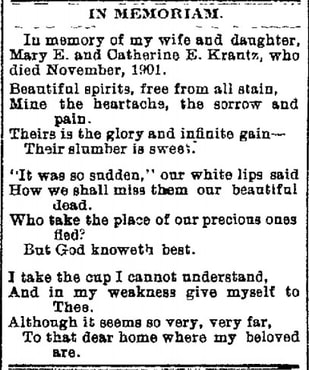

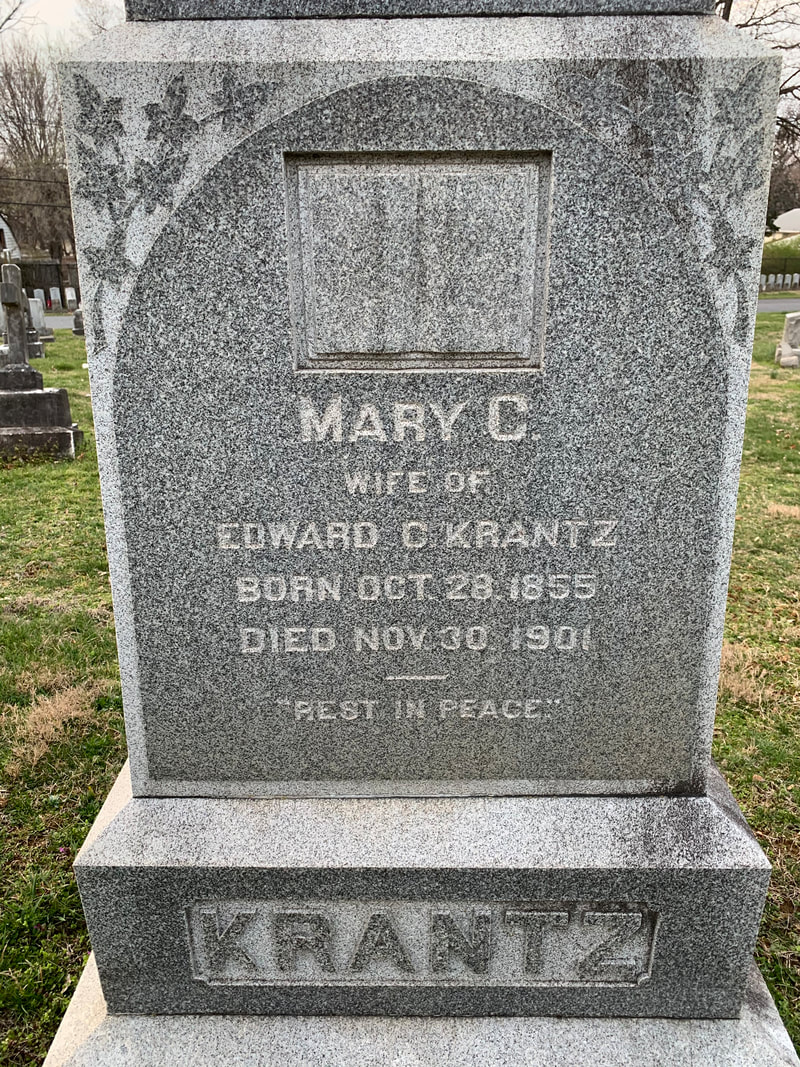

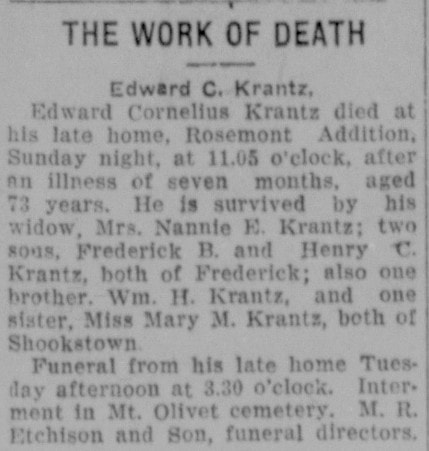

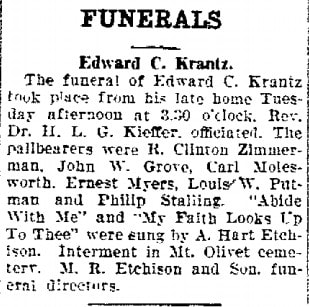

A picturesque scene can be found in Mount Olivet’s Area G. Standing high above all surrounding others is the funerary monument of Edward C. and Mary Catherine Krantz. The towering gravestone was erected in the waning years of the Victorian Era (1832-1903) and displays the high ornamentation that characterized that time period. The era was an eclectic period in the decorative arts with several styles—Gothic, Tudor, Neoclassical—vying for dominance. This was true in architecture, furniture, and, of greatest interest here, the funerary arts. In cemeteries, gravestones became taller, embellished and sentimental. This particular grave monument on Lot 156 features a shrouded woman with arms folded across her chest, gazing upwards toward the heavens in what appears to be prayer and contemplation. The white marble statue sits atop a polished, granite base. Altogether, the work stands roughly 10 feet in height. The monument itself is a paean to Victorian design—possessing an air of triumph, symbolism and sentimentality. Upon closer inspection, one will notice that the woman has a chain draped around her neck which extends down and across her chest to an upright anchor at her side. One of the anchor’s spades is partially concealed under the rear of her robe. Look carefully and you will see that the chain is actually depicted as being broken at the point it reaches the eye-hole atop the anchor. Anchors abound on tombstones throughout Mount Olivet. In some cases, they denote the sailing profession of the deceased as is the case with that of Captain Herman Ordeman (1812-1884) of whom I published an earlier story back in late summer of 2017. More so than not, it is the religious/Christian symbolism of the anchor that comes into play with these grave markers as we have a large amount featured throughout the grounds. The gravestone of the father of the earlier mentioned Edward C. Krantz actually utilizes the anchor-cross motif in an adjoining lot (Area G/Lot 158).  As a religious symbol, anchors were used in antiquity as secret crosses and denoted hope, and still do today. Within the books of the New Testament, the passage in the Epistle to the Hebrews 6 states: “Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast, and which entereth into that within the veil.” A translation elaborates on this passage attributed to St. Paul, saying: “So God has given both his promise and his oath. These two things are unchangeable because it is impossible for God to lie. Therefore, we who have fled to him for refuge can have great confidence as we hold to the hope that lies before us. This hope is a strong and trustworthy anchor for our souls. It leads us through the curtain into God’s inner sanctuary.” The three theological Virtues (human forms that represent core Christian values) include Faith, Hope and Charity, and the figure of Hope almost always has an anchor with her. Therein lies the allegorical statuary category that this gravestone can be classified within--the Statue of Hope. These were commonly erected in the Victorian era and believed to be popularized by the Statue of Liberty's dedication in 1886. A female, typically shown wearing Roman Stola and Palla garments, stands with one arm resting on, or holding, an anchor. Often, the opposite arm is raised with the index finger of the hand pointing towards the sky, symbolizing the pathway to heaven. Holding one’s hand over the heart symbolizes faith and devotion. In the case of the Krantz monument, the woman has her hands folded in a show of complete devotion and subservience. Statues of Hope generally feature elements of a broken chain attached to the anchor, or sometimes hanging from the neck symbolizing the cessation of life. Many statues feature the maiden donning a “Crown of Immortality” made of flowers or stars. The flower or star on the top of the forehead, usually on a crown or diadem, and represents the immortal soul. Prior to this, other images such as Saint Philomena (patron saint of infants, babies and youth) whose authorization of devotion began in 1837 and Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen's Goddess of Hope statue sculpted in 1817, displayed similar characteristics. One of the earliest signed Statue of Hope memorials was carved by Odoardo Fantacchiotti in 1863 for the grave of Samuel Reginald Routh of England in the Protestant Cemetery of Florence, Italy. Another variation was completed earlier in 1791 with the Custom House, Dublin Ireland in which a 16-foot tall statue of a female resting on an anchor is atop the building’s iconic dome. This statue has been called both the Statue of Hope and the Statue of Commerce. The Krantz Family So just who were these “hopeful” people that left us with such a beautiful lasting legacy in the form of a statuary monument atop their gravesite? Thanks to a number of sources, I had a relatively easy time of learning their vital statistics, life stories, and causes of death. An extra bonus came with accessibility to images of the couple courtesy of polished embellishments to both an Ancestry.Com Family Tree and Find-a-Grave pages by family historian Patrick Aaron Steward. (Thanks Patrick!) The History of Frederick County by T.J.C. Williams and Folger McKinsey includes an elaborate biography on Edward Cornelius Krantz. Mr. Krantz was born on July 3rd, 1852 on a small farm and grist mill located along Linganore Creek in the New Market District. He was the son of Frederick J. and Catherine E. (Stup) Krantz. Edward’s grandfather (John Dietrich Krantz 1820-1890) had come to this country from Germany in his youth and worked as a shoemaker. Son Frederick took up the occupation of miller and worked at various locations around Frederick. In 1869, Edward’s father (the above-mentioned Frederick) purchased a fine farm of 142 acres, located two and a half miles northeast of Frederick City on the Shookstown Pike. Here’s where we find our subject living in the 1870 census as he spent his childhood learning his life’s profession of farming. After his father’s retirement, he and brother William managed the home farm for three years. Edward would go on to rent another farm that their father had acquired in 1879 on the Buckeystown Pike and located a few miles south of Frederick. The young man would purchase and make this his home until 1901. Edward's brother, William, and sisters farmed the old family homestead bisected by Shookstown Road (between Willowdale and Waverly drives). The remaining structures were recently demolished to make way for the Gambrill View housing subdivision. When the farm sold out of the Krantz family in 2001 (to a developer from Leesburg (VA)), it was one of the last remaining large farms operating with the Frederick City limits. Edward C. Krantz married Mary Catherine Biser, born October 28th, 1855 in Middletown. She, like her husband, had been raised on the family farm belonging to her parents, Henry and Sophia Routzahn Biser. They married in 1885 and had three children: Frederick Biser Krantz (b. 1886), Catherine Elizabeth Krantz (b. 1887) and Henry Cornelius Krantz (b.1895). Of wife Mary Catherine, Williams’ reads: “She was a devoted helpmate in his (Edward’s) labors.” The family attended the Evangelical Reformed Church of Frederick and made their domicile into what Williams’ states as “an elegant farm of 140 acres.” The author stated Mr. Krantz to be “one of the highly successful agriculturalists of the Frederick District. "The property is west of the Buckeystown Pike (today's MD route 85), north and east of Crestwood Blvd, surrounding Westview Drive. Fortunately, the Krantz farm stayed pretty much intact, with the exception of some road right-of-ways, from before 1859 through 1986. I know this takes us a bit off subject, but I was fascinated to see the ownership of this property over history before and after the Krantz family. This info comes courtesy of my awesome research assistant, Marilyn Veek, and includes other residents of Mount Olivet who I have bolded (names) for your reading pleasure. These include: Abraham Adams, Valentine Adams (1799-1860 in Area H/326) Abraham's son, John Henry Nelson (1820- 1870 in Area H/326) Valentine's son-in-law, Richard and Caroline Kemp Lamar (1815-1879 in Area D/53), Robert Guy Lamar (1848- 1885 in Area Q/45) son of Caroline. Here are a couple of descriptions of the farm as it existed in the 1860s, from chancery court records: It had a 2-story brick house, barn, stable, carriage house, wagon shed, smoke house and other out buildings including a large quarter for servants detached from the house. It had two pumps of water, one near the house and the other near the barn. The soil is limestone, quality unsurpassed; improvements consist of a 2-story brick house of 9 rooms and kitchen, barn, stabling, shedding, corn house, ice house, a first-class farm. There is also a tenant house which has recently been repaired at great expense. Farm lately used as a dairy farm for at least 30 cows; has fine water, milk house, fine orchard of various fruit.  1873 Titus Atlas map showing Evergreen Point area below Frederick. The Krantz Farm on Buckeystown Pike can be denoted in the vicinity of G Graham shown on mapto the immediate west of Hermitage Farm. Of special interest is the fact that the author feels that the farm was tenanted by George Graham (b. 1819), an African-American who appears with his family in the 1850 and 1860 census records. He could have interesting tiies to the Vincindiere family who began Hermitage Farm or to the Grahams of Rose Hill Manor (daughter and son in law of Thomas Johnson, Jr.) Everything seemed to be going well for the Krantz family until late 1901 when bitter misfortune would rear its ugly head. In my curiosity, I became determined to learn more about this malady that killed many in the time before modern medicine and a known vaccine. Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a bacterial infection due to a specific type of Salmonella that causes symptoms that may vary from mild to severe, and usually begin 6 to 30 days after exposure. It likely starts from ingesting contaminated food or water. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several days. A critical added danger of Typhoid is its spread to others by way of eating or drinking food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person. Family members were prime targets. The best they could do was wash hands meticulously—certainly more difficult to accomplish in the days before running water. In the desperate nursing of the newly turned 14 year-old daughter, a hopeful and devoted mother would fall prey herself to the dreaded illness. Edward had lost his teenage daughter and 46 year-old wife within that fateful month of November 1901. He would erect the Statue of Hope memorial to these two exceptional women of his life. The monumental losses suffered could have prompted him to move back to his earlier home area north of Frederick. He purchased a 185-acre farm on the old Montevue Pike (today’s Rosemont Ave), and erected a two-story dwelling, a bank barn and other buildings, at the same time improving an existing house on the land. The existing house was none other than Schifferstadt, one of Frederick's earliest dwellings. The property consisted of land stretching westward to Baughmans Lane, eastward to West 7th Street, and to Fort Detrick. My home in the Villa Estates neighborhood (between US15 and Military Road) was even part of the Krantz farm. Edward married again two years later in late 1903. His second wife, Mamie E. Schaeffer was the daughter of Frederick druggist David L. Schaeffer and wife Elizabeth. Edward Krantz would continue overseeing his farm properties and stayed active in town and religious affairs. He died on March 21st, 1926 and was buried beside his beloved daughter and exceptional helpmate—one who, like many other devoted women, sacrificed her own life in the unselfish care of an ailing child. Saint Philomena surely interceded on her behalf then, and in the form of a statue of Hope that has kept vigilant watch over the women's mortal remains ever since. As for the farms of Edward C. Krantz, the Buckeystown Pike farm was conveyed to his sisters when he re-located north of Frederick City (after the deaths of his wife and daughter). The Krantz sisters sold it to Henry Krantz, Edward's son. Henry sold it to Gerrit and Elizabeth Lewis Peters (1898-1989 in Area E/Lot 89). The Peters sold it to Tyler Gatewood Kent, who sold it to Martha Prior. She sold it to her son Howard Anderson Prior (1905-1985 in Area FF/252), who eventually sold it to the trustees of Princeton University in 1984. They sold it to Westview Associates Ltd Partnership in 1986.

And here is the former Edward C. Krantz farm today:

2 Comments

Nancy Droneburg

3/28/2020 10:15:14 am

How sad that our history is becoming sub divisions and parking lots

Reply

Patrick Aaron Steward

5/21/2020 11:48:17 am

Hi!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed