|

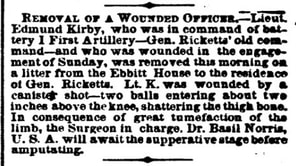

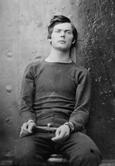

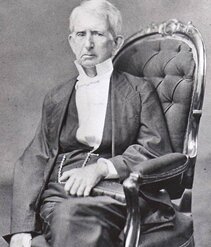

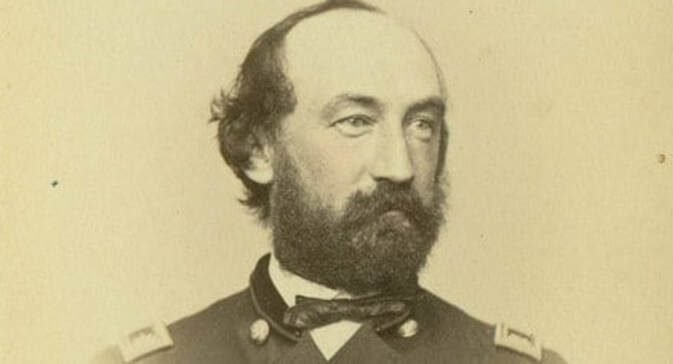

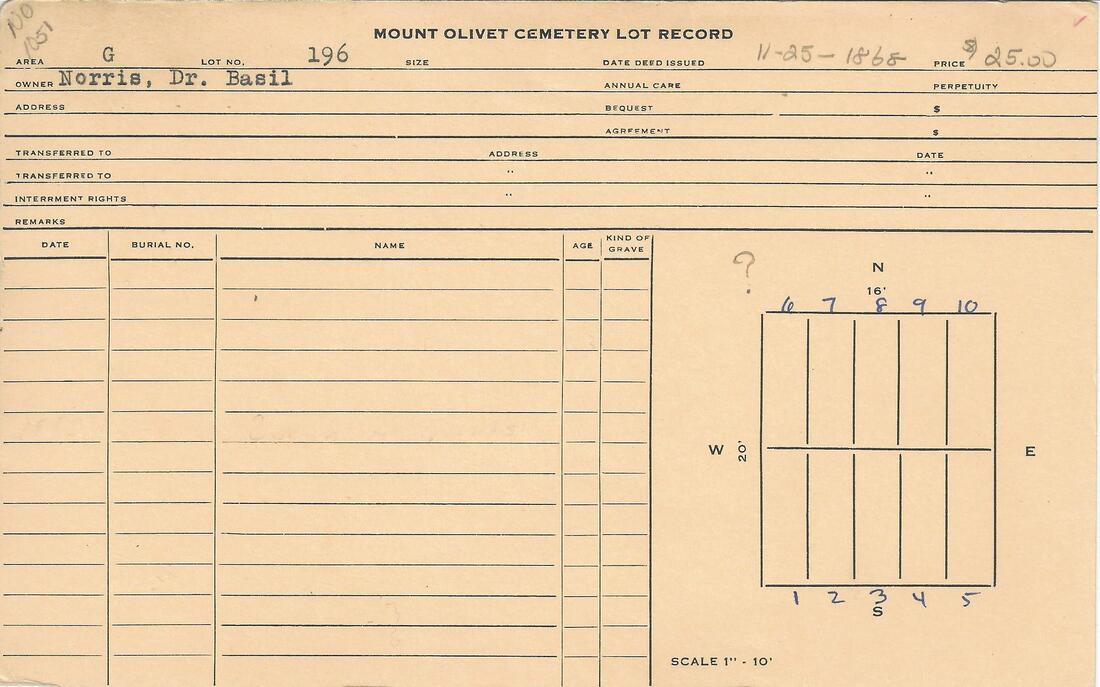

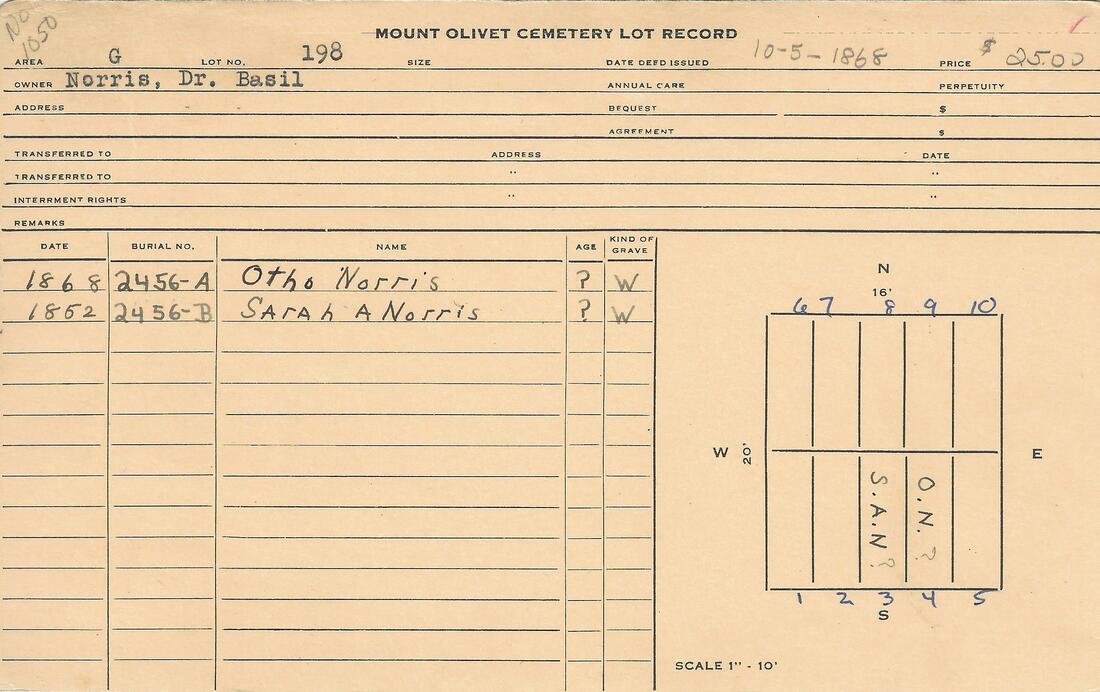

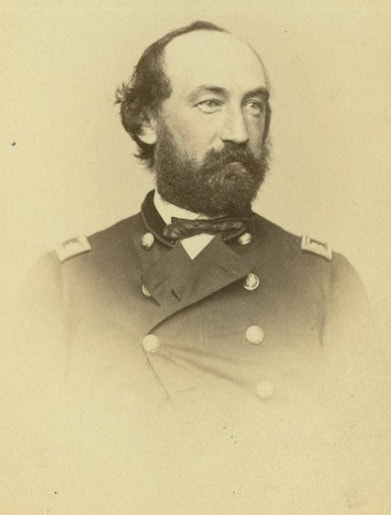

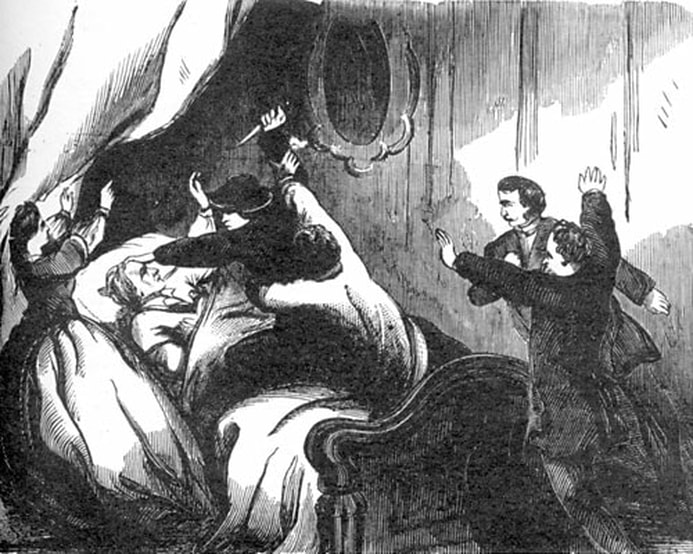

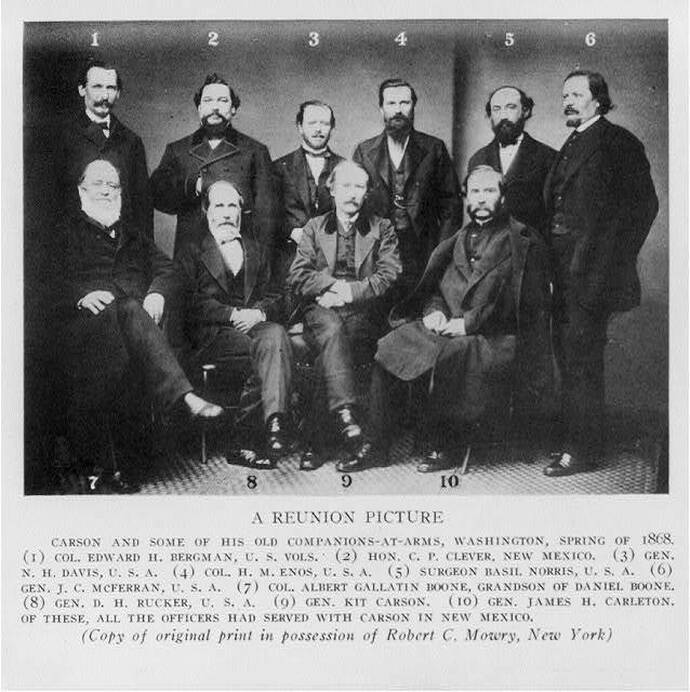

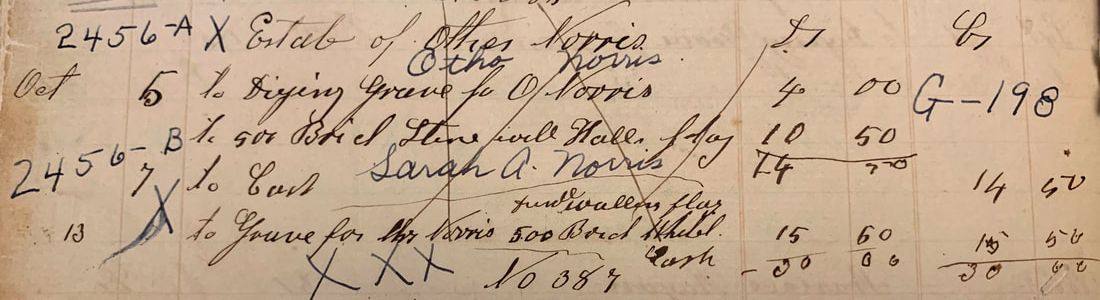

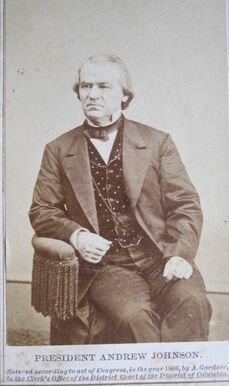

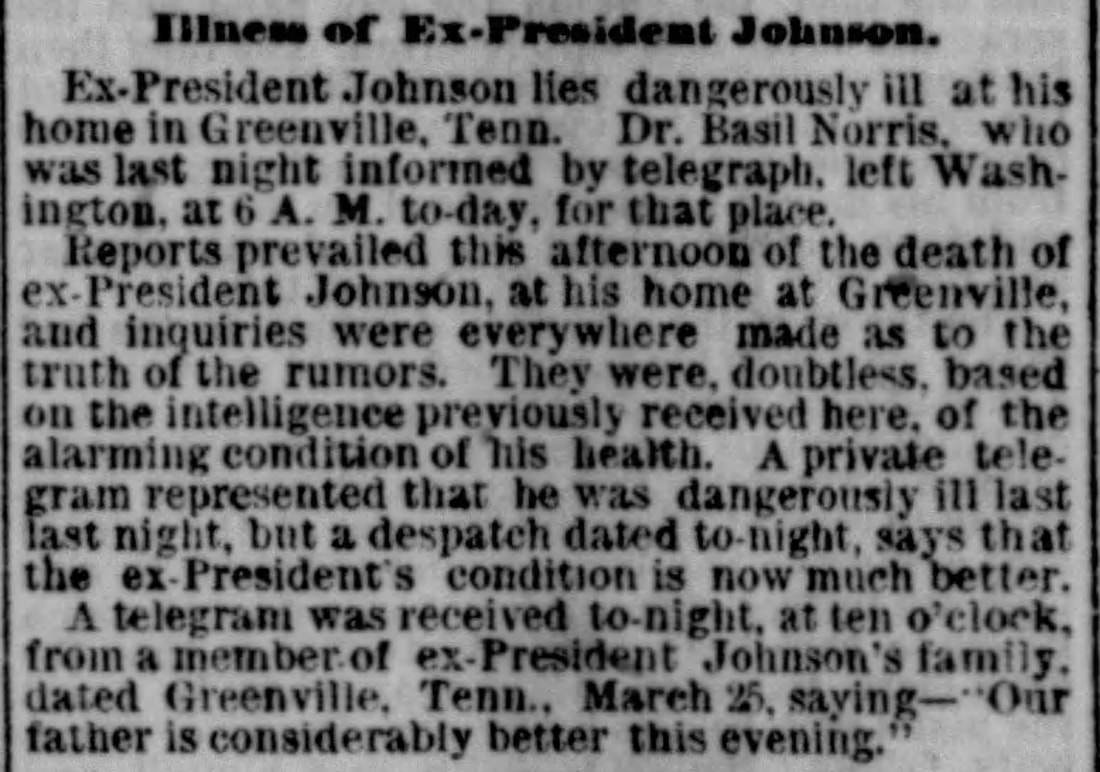

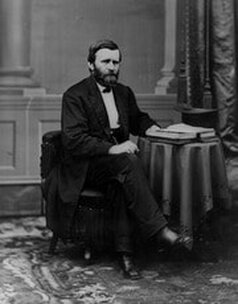

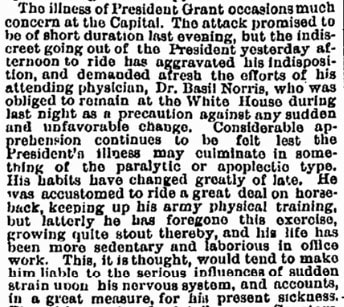

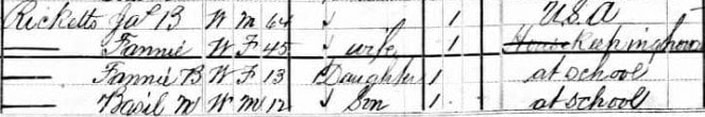

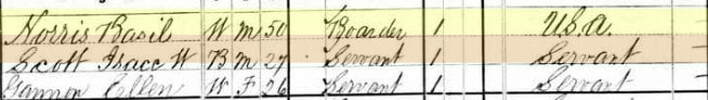

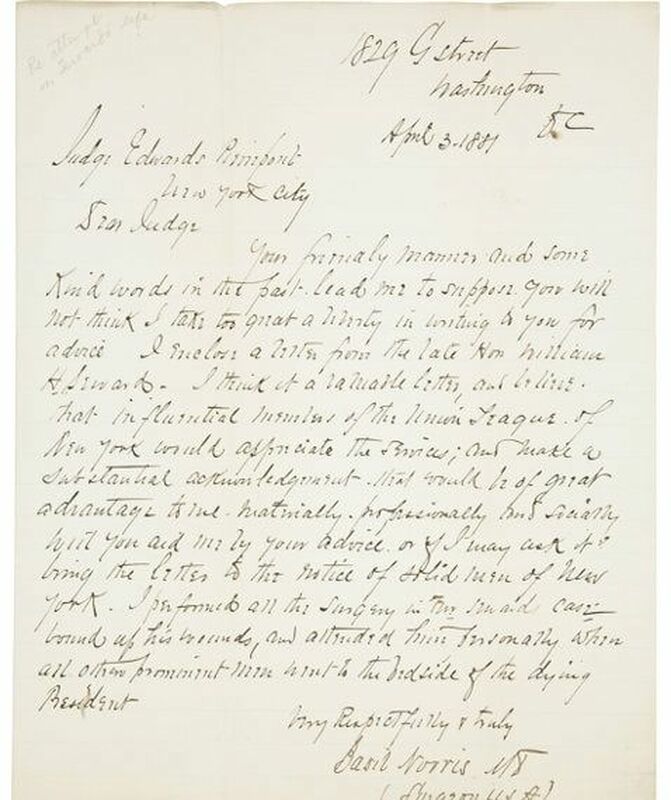

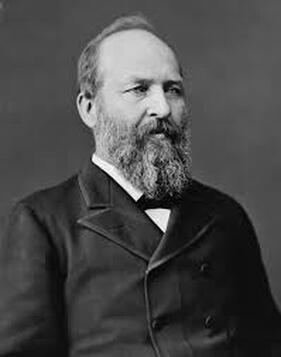

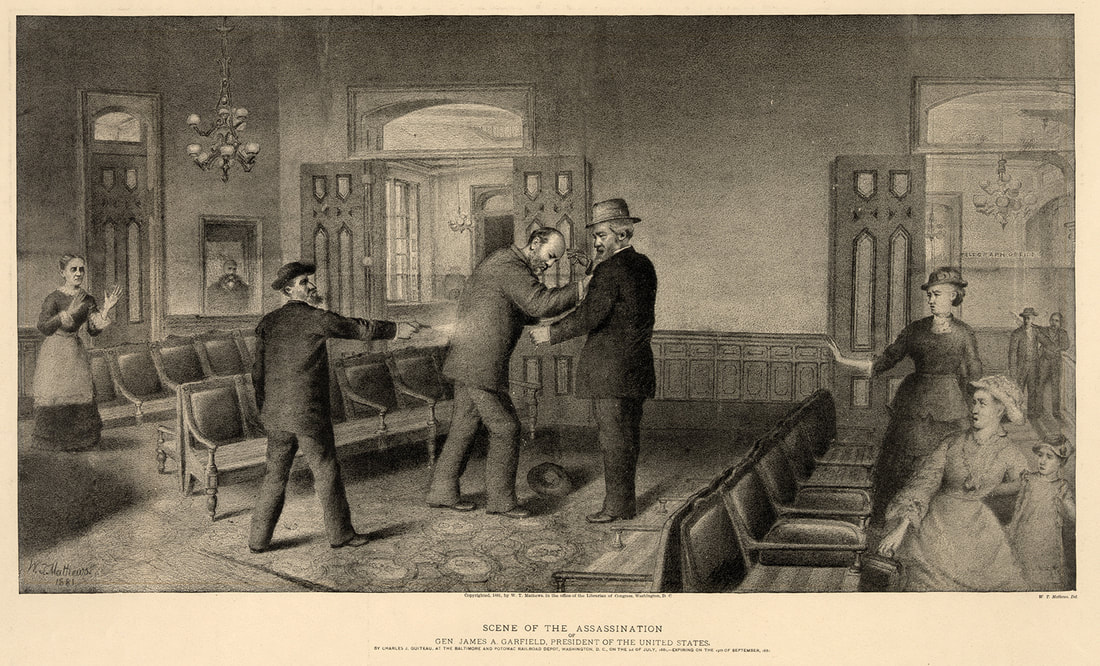

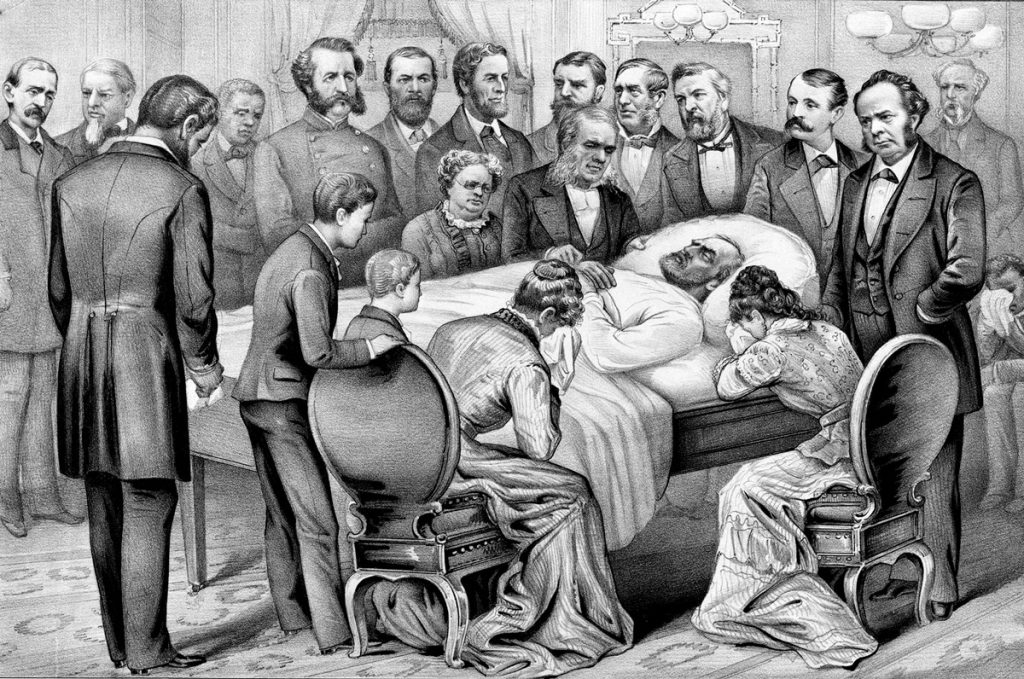

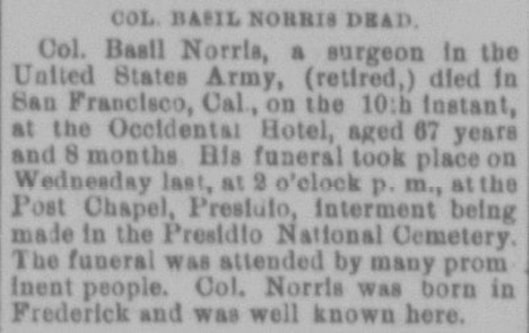

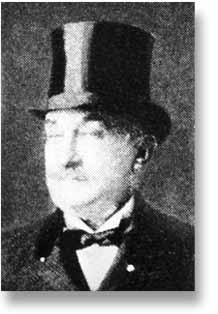

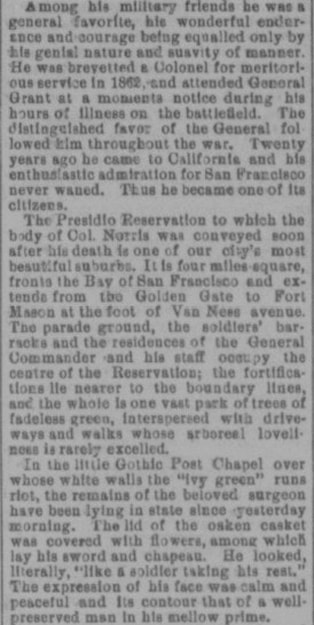

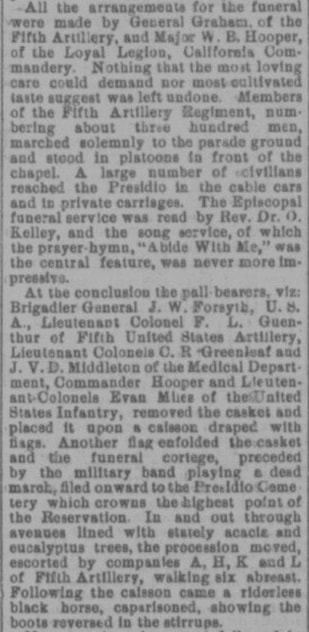

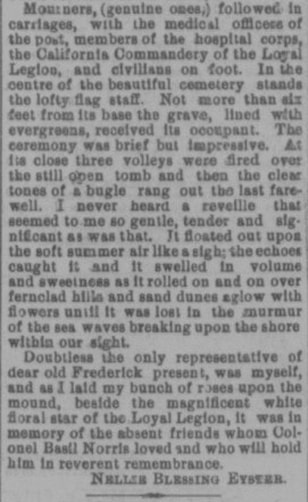

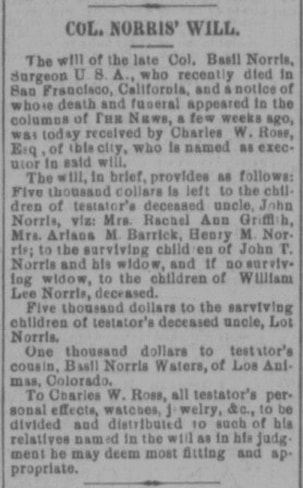

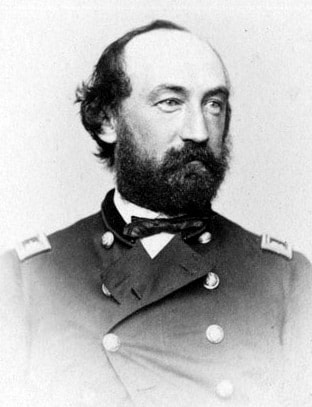

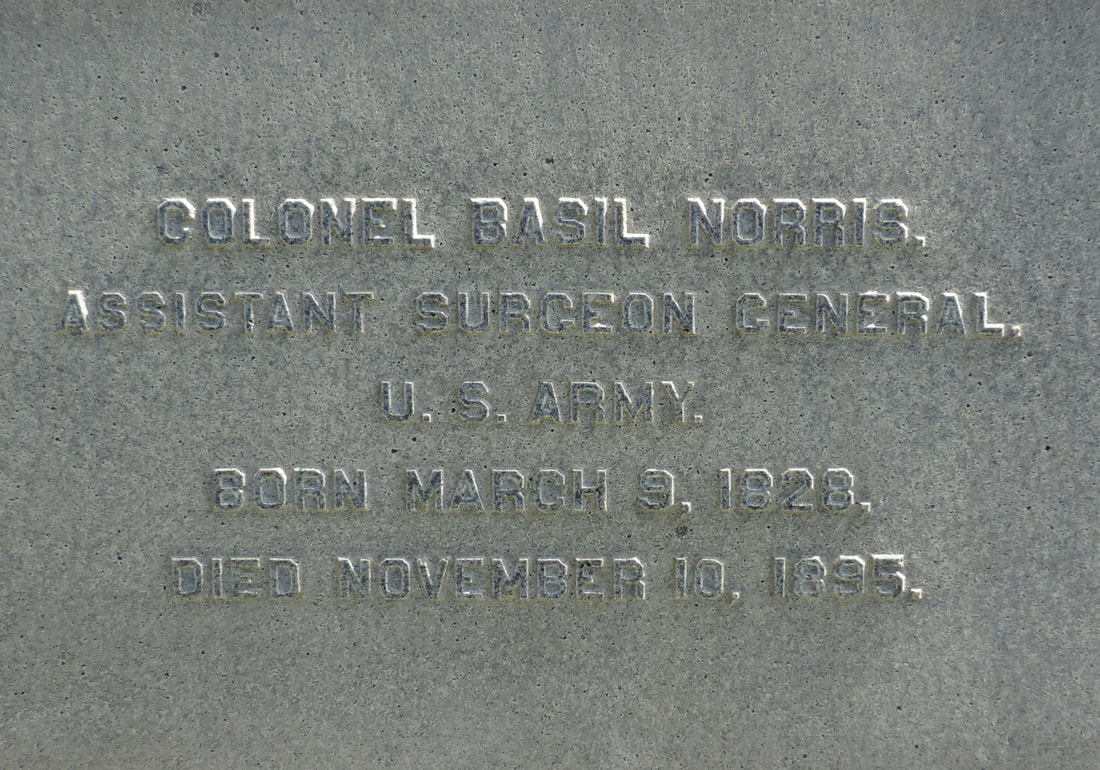

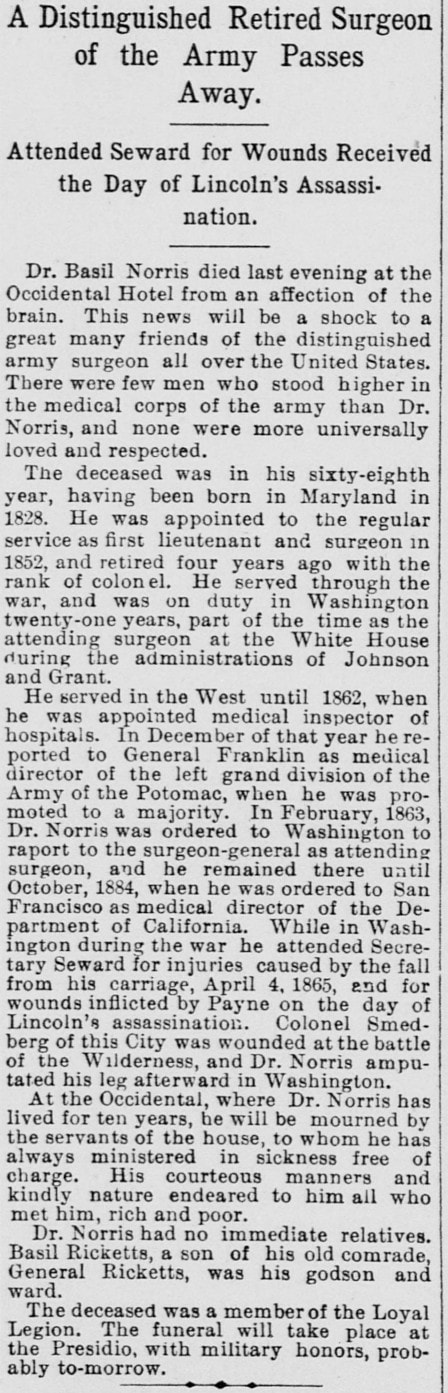

So the premise of our blog is clearly based on the “memorialization power” a gravestone, monument or plaque can wield. You can find them formed out of marble, granite, slatestone, and even white bronze. Most are beautiful works of craftsmanship, some representing bonafide works of art and magnificent architecture. No matter how grand or petite, each grave marker stands as proof that a particular human being once walked this earth between the given birth date (or year) and death date carved upon its surface. The particular individual’s journey could have taken them across the country, or to another continent. Meanwhile, there are others who perhaps never ventured outside of Frederick County. Regardless of your spiritual beliefs, the end of the respective “road” for the mortal remains of over 40,000 people is right here in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. Gravestones are important touchstones to relatives and future generations to come. They are also invaluable to folks like me and countless other researchers in trying to decipher what happened during “the dash” that appears between those birth and death dates on the face of a stone.  Norris sisters' monument in Area F/Lot 12 Norris sisters' monument in Area F/Lot 12 Back in January, 2017, I performed some research in an effort to locate the first monument erected in our cemetery. This event occurred in May, 1854, just a few weeks before the formal opening services of the cemetery and the first interment—Mrs. Ann Crawford. The beautiful twin-columned monument of Parian marble was placed on the new gravesite of two teenage sisters who had died a few years earlier, and had been originally interred at the All Saints Protestant Episcopal burying ground located along Carroll Creek. The individual responsible for commissioning this outstanding grave marker was Basil Norris (1788-1865), the girls’ father and a successful grocery store operator that once stood in the first block of W. Patrick St. When doing my research, Mr. Norris’ name seemed somewhat familiar to me in some fashion. Upon further review, I realized that I had seen the name of another Basil Norris who was a member of the Union’s Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. This individual was a noted surgeon during the conflict, and afterwards served in the capacity of presidential physician, or better put—a physician utilized by a few of our US presidents. Once I read that fact, I sort of lost my focus on the Norris sisters and their inaugural monument, and took aim on Basil Norris, the surgical soldier. I looked in our Mount Olivet database to see if Dr. Norris was buried here, and soon found that he bought two entire grave plots in the fall of 1868. Each plot consisted of 10 individual grave spots, all located in Area G. In my excitement, I drove out to inspect the site, but only found one large monument on the easternmost lot of the two in Norris’ name. Both grave plots were what we call “feature lots,” front road burial locations adjacent one of the drives or avenues of the cemetery. The large monument referenced before was that of Otho Norris (1799-1868) and wife, Sarah Ann (McElfresh) Norris (1805-1852). There were also corresponding footstones for the couple, but clearly no sign of Basil Norris the Union officer. Not finding anything, I had a fleeting thought to myself that perhaps his grave was unmarked? I went back to my office and got back in our cemetery database. My mystery physician was clearly on electronic record and listed as occupying space #1 of Area G’s Lot 196. However cemetery superintendent Pearcey would tell me that this was simply a facet of our computer data program, and Dr. Norris may not be buried there at all. Each plot-holder has to attached to a cemetery lot for the program’s search engine to work properly. He told me to check the official interment cards, as they tell the true story. Here I found that Dr. Norris also purchased Plot 198 as well (to the left of #196 in picture above). It’s generally a rarity that a lot-holder would not be buried in his or her plot, but this could possibly be a “dummy” read which would soon be confirmed. Find-a-Grave.com showed me that Col. Basil Norris, M.D. (1828-1896) was buried in San Francisco’s famed national military cemetery—the Presidio. Shortly thereafter, I found a footnote in our records that said the same thing. Irony was certainly at play as our cemetery’s first monument, and likely that of our most famous “missing monument” are tied to gentlemen possessing the same name (Basil Norris), and in the same family. As a matter of fact, Basil the Civil War surgeon was the nephew, and namesake, of Basil the merchant, which was really all I needed to know for that story two years ago. Ever since, I have been curious as to why Basil bought 20 lots (2 full plots) in 1868, but was buried on the other side of the country. I also wondered what was Col. Basil’s relationship to Otho and Sarah Ann Norris? Lastly, I still lament the fact that the famous doctor is not here as it would make such a great tie-in to Frederick’s Civil War Medicine legacy told so wonderfully at our downtown museum (National Museum of Civil War Medicine). So, I apologize that it’s not a legitimate Mount Olivet “Story in Stone,” but since Col. Basil Norris was a minor celebrity, along with being a major cemetery lot-holder, why not tell his “Story not in Stone.” Besides, this blog’s initial publishing comes so close to April Fool’s Day, so what the heck. Col. Basil Norris The son of Otho Norris and Sarah Ann (McElfresh), Basil Norris was born in Frederick County on March 9th, 1828. His father was a merchant in town, and the family seems to have had strong connections to the Libertytown-Unionville area in the northeast part of the county. The Norris’ were members of All Saints Church, but I haven’t located their home in town as of yet. Basil was named for his uncle, whom we introduced earlier. The young man served as class secretary and graduated from the University of Maryland’s medical school in 1849. He entered into the US Army in 1852, and served with troops in Texas, Utah and New Mexico during the decade which followed the Mexican-American War.  Evening Star, Washington DC (May 7, 1863) Evening Star, Washington DC (May 7, 1863) Basil Norris returned east in 1862 during the intensity of the American Civil War. He was first appointed medical inspector of hospitals. Soonafter, Norris was promoted to the rank of Surgeon in 1863 and appointed Medical Director of one of the grand divisions of the Army of the Potomac. Interestingly, Dr. Norris would apply for a transfer from his post with the US Army of the Potomac, finding: “…my duties here are not important. These duties can be performed by volunteer surgeons, quite as well by me. In Santa Fe, I could add to my income by private practice and my appointment would be agreeable…“ Norris was eventually stationed as the attending physician of officers of the regular army and their families in the City of Washington from 1863-1884. He also maintained a private practice as well. For meritorious services, Basil Norris would be raised to the rank of Lieutenant–Colonel in 1882 and, and finally Colonel in 1888.  Lincoln conspirator Lewis Powell Lincoln conspirator Lewis Powell On the night of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Norris had been at Secretary of State William H. Seward’s bedside earlier in the evening, treating his private patient for a double fracture of the upper jaw caused by a carriage accident which occurred a week earlier. Later that night, John Wilkes Booth’s conspirator, Lewis Powell, attacked the secretary in his bedroom on that ill-fated night of April 13th, 1865. Norris returned that night and treated Seward for his new wounds which could have proven fatal. He continued his intensive care of the secretary over several weeks to follow.  William H. Seward recuperating after the assassination attempt on his life William H. Seward recuperating after the assassination attempt on his life I found an official public commendation in the form of a resolution by the New York State Senate in regards to Col. Norris’ care of Secretary of State Seward. This was found in the 1883 Journal of the Senate’s proceedings. Here, a letter written by Secretary Seward to Col. Norris in July 1870 was read to the body and recorded for posterity: “Dr. Basil Norris, Surgeon U.S.A.: My Dear Sir—I cannot doubt that I have long since made you understand, in our pleasant social intercourse, how lightly I appreciate the surgical skill and care with which you treated me in the year 1865 when I fell under the blows of an assassin, inflicted while I was lying helpless in my bed in my own house at Washington. A season of rest, however, which I long desired, and needed, has come to me at last, and I am improving it as well as I can by performing personal domestic and social duties which were neglected when I was engaged in the public service. It seems to me to be an important duty of this kind to record, in a manner that may be lasting, my acknowledgements of the appreciation which I have mentioned of the gratitude I owe you as a savior of my life, of my profound respect and of my sincere and affectionate esteem. —William H. Seward” The testimonial gave thanks to Col. Norris for saving Seward’s life in 1865. This is especially interesting because Norris’ actions would make possible Secretary of State Seward’s greatest career achievement two years later. The United States purchased Alaska on March 30th, 1867. Seward brokered the deal with Russia for $7 million, which equaled two cents an acre. The deal almost didn't pass the Senate and was mocked in Congress. They called the new territory “Seward's Folly” or “Seward's Icebox.” The rest is history, and our native son had a hand in it, per se. Basil Norris bought his Mount Olivet burial plots on the occasion of his father’s death on October 3rd, 1868. His mother Sarah Ann had passed back in November, 1852. Son Basil made the burial arrangements for his father, and at the same time, had his mother re-interred here from All Saints Protestant Episcopal burial ground. Another note of interest is that I found the widowed Otho living with his brother, Basil Norris (the grocer) in the 1860 US Census. He likely lived with them up through his death. Presidential Encounters Basil Norris subsequently became the physician for Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson and his family. Johnson suffered from recurrent kidney stones during his abbreviated tenure as president through early 1869. His ailment was described by a colleague: ”Afflicted with gravel, he found no cessation from pain, and but little relief in standing while at work for hours in preference to remaining in a sitting posture, or from a variety of an occasional “fit of the grave with its excruciating torture.” This malady was both serious and episodic, and it felled the president in the summer of 1865, and again in the late winter and spring of 1867. Johnson, in order to obtain relief, “had taken to working at a high desk, standing up.” Just weeks after leaving office, Andrew Johnson became extremely ill in March, 1869, probably from a recurrence of renal stones. Col. Norris expeditiously traveled to the ex-President’s home in Greenville, Tennessee, where Johnson eventually wrote: ”…In my extreme illness after my return from Washington, when my life had been despaired of, your presence at my bedside, after so short a notice, seemed almost to be the work of magic power.” The military surgeon from Frederick would return from Tennessee and tend to the personal needs of newly-elected president Ulysses S. Grant and his family. This continued for the next eight years. During this tenure, however, Norris became embroiled in a debate between civilian members of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia and those army and navy members who maintained private medical practices in Washington. This was 1877, and Norris became a major figure in the question of whether a military physician could ethically provide professional care to a civilian, even though that civilian was the former US commander in chief. (Fifteen years later In 1892, US Surgeon General Charles Sutherland ordered that the tradition of civilian practice by Army doctors be discontinued.) President Grant, and his family, suffered from no significant illness during their eight years in the White House. Grant, upon departing the presidency, expressed to Col. Norris his “…gratitude and that of his family for your many acts of kindness and professional attendance in every case occurring with us for the past eight years.

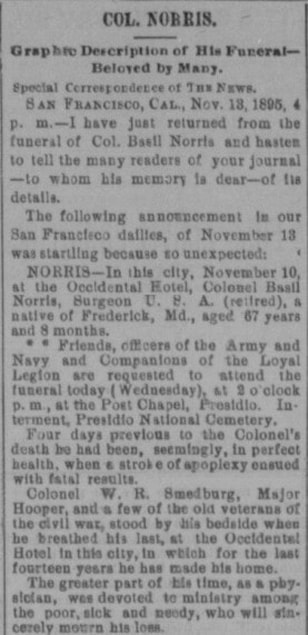

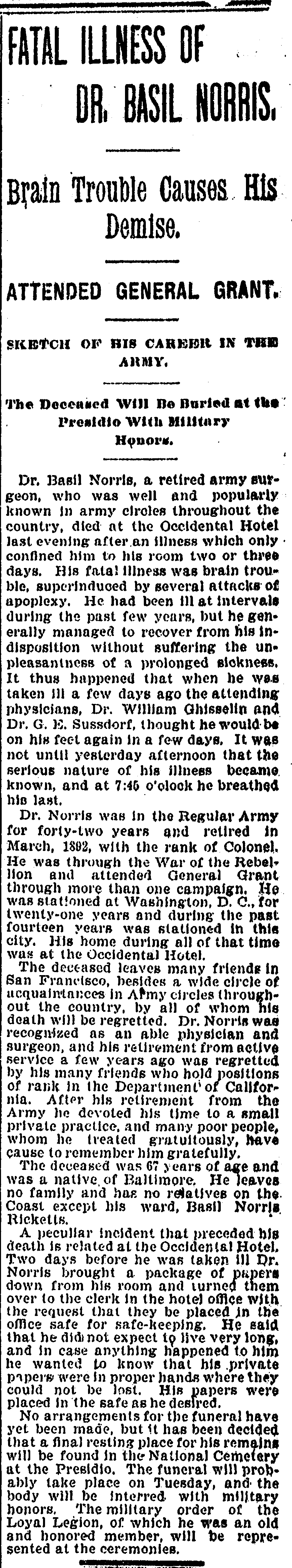

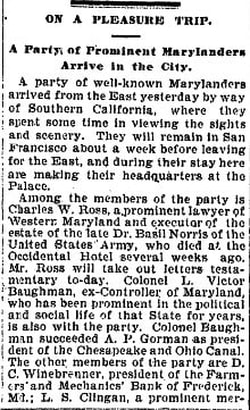

Historians agree that massive infection was a significant factor in President Garfield's demise. Norris wasn’t the principal physician on the scene, but was among the group. The president recuperated for a few months, but finally succumbed to infection and blood poisoning on September 19th, 1881, the second US president to die from an assassination attempt. In 1884, Col. Basil Norris left the nation’s capital after a 21-year stint. He relocated to San Francisco, California to serve as Medical Director of the US Army’s Division of the Pacific. He took up residence at San Francisco’s Occidental Hotel. Col. Basil Norris retired from the military in 1894 but kept his private practice in which it is said that he helped provide medical care to San Francisco's poor and indigent. His medical writings are said to have been numerous and scholarly. He was described as having been a genial man, an accomplished physician and an efficient officer. Norris died of apoplexy in San Francisco on November 11th, 1895.

Additional obituaries featured in the San Francisco papers

2 Comments

7/17/2019 01:22:10 pm

Hi

Reply

7/17/2019 01:56:06 pm

Hi John,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed