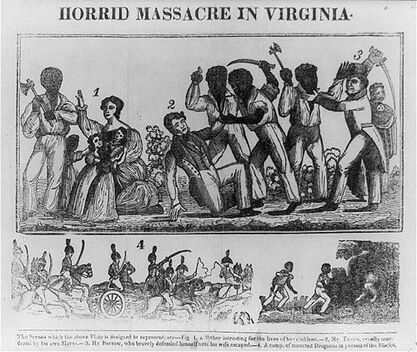

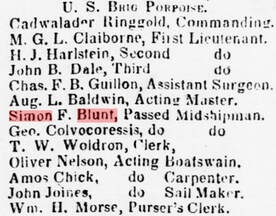

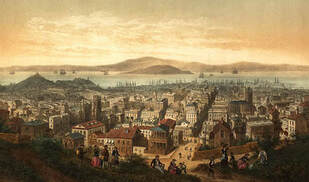

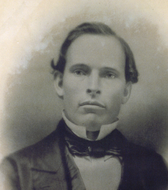

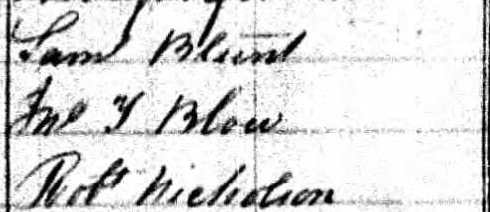

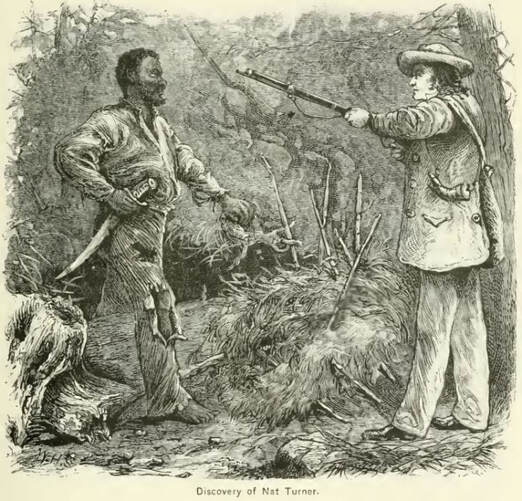

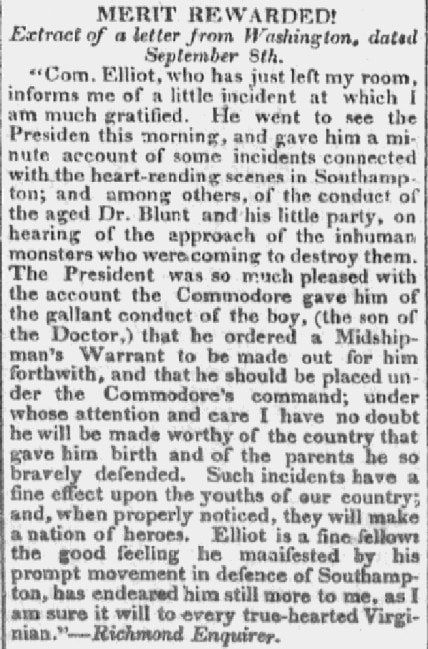

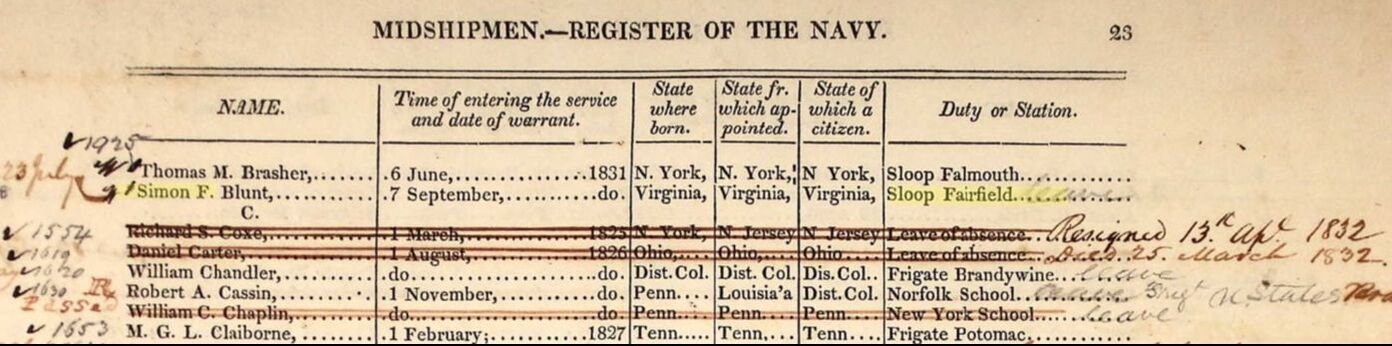

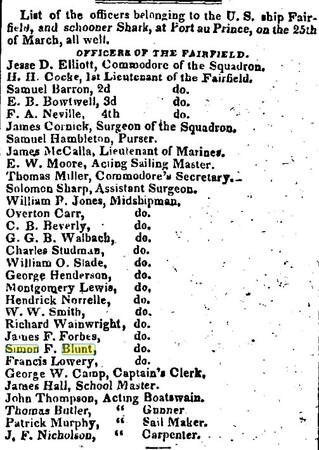

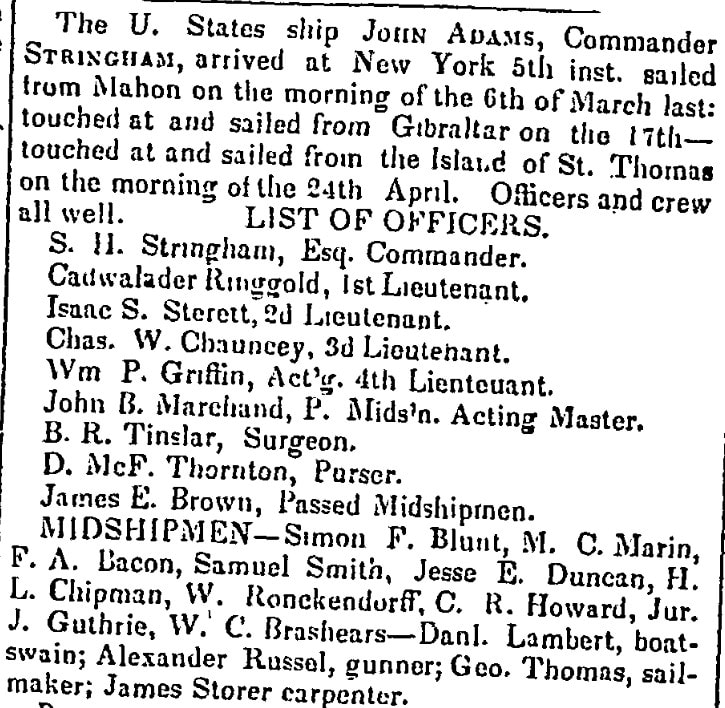

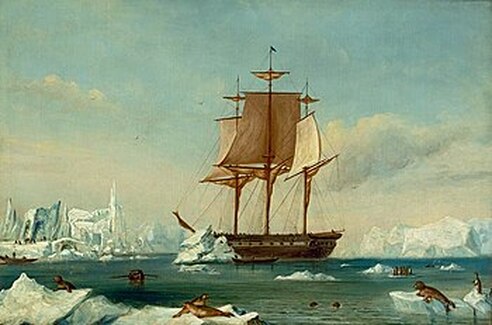

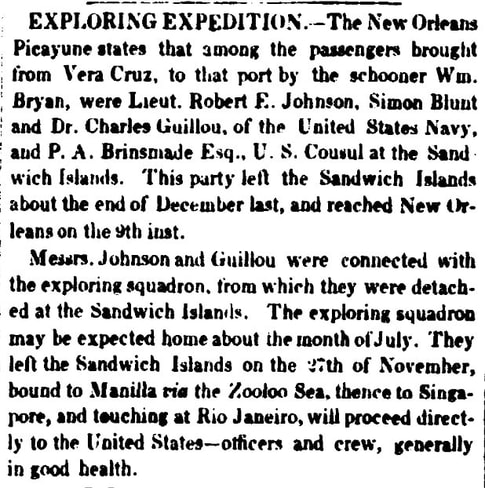

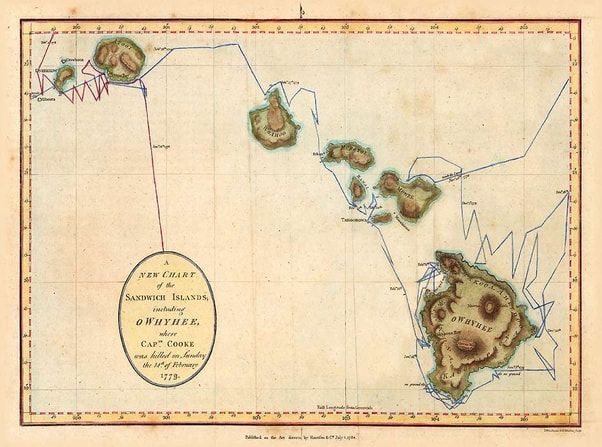

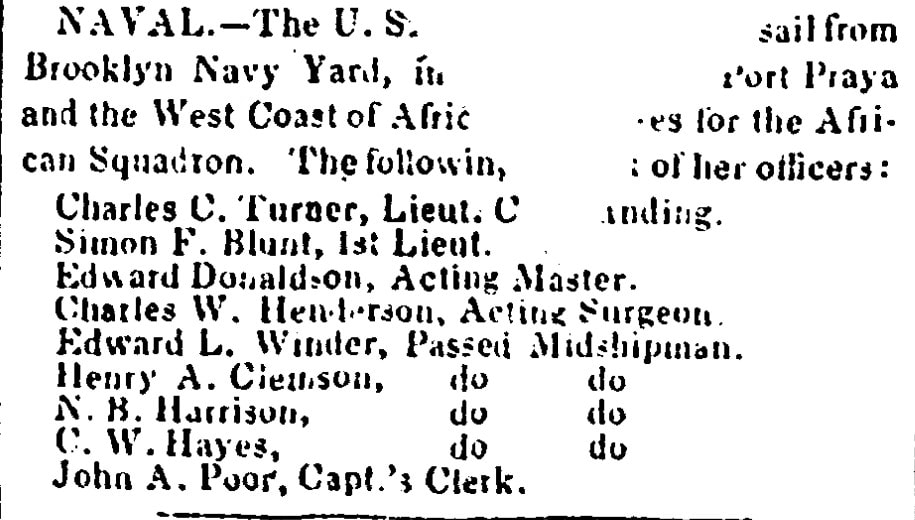

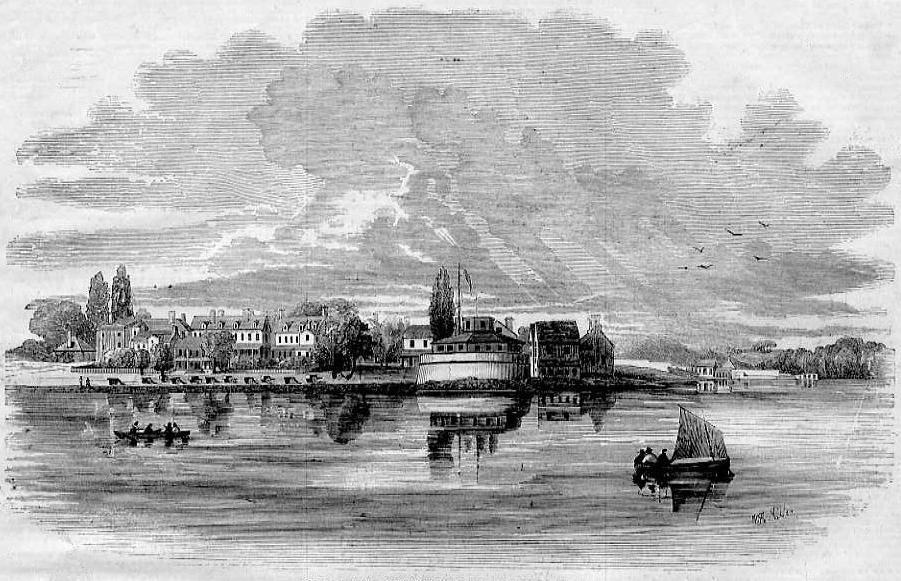

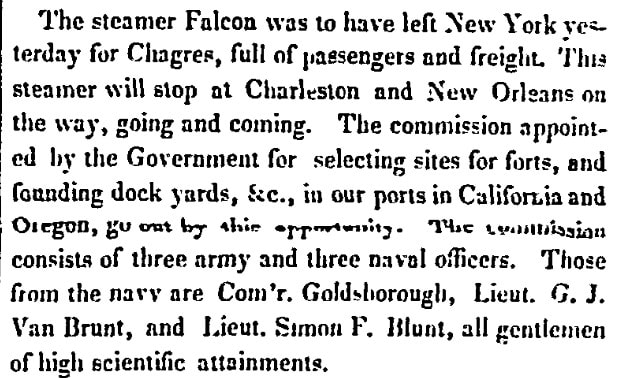

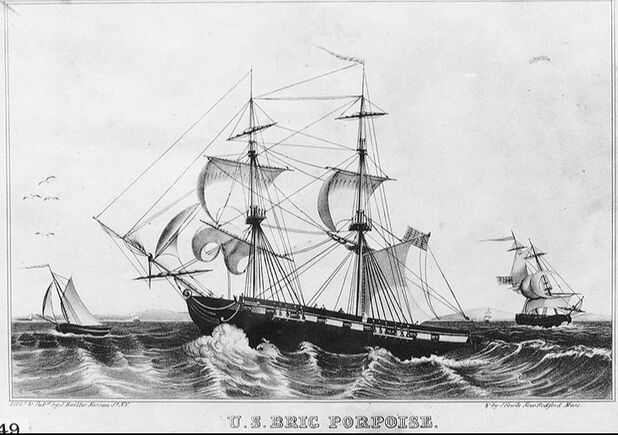

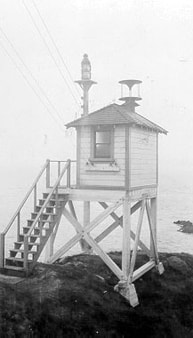

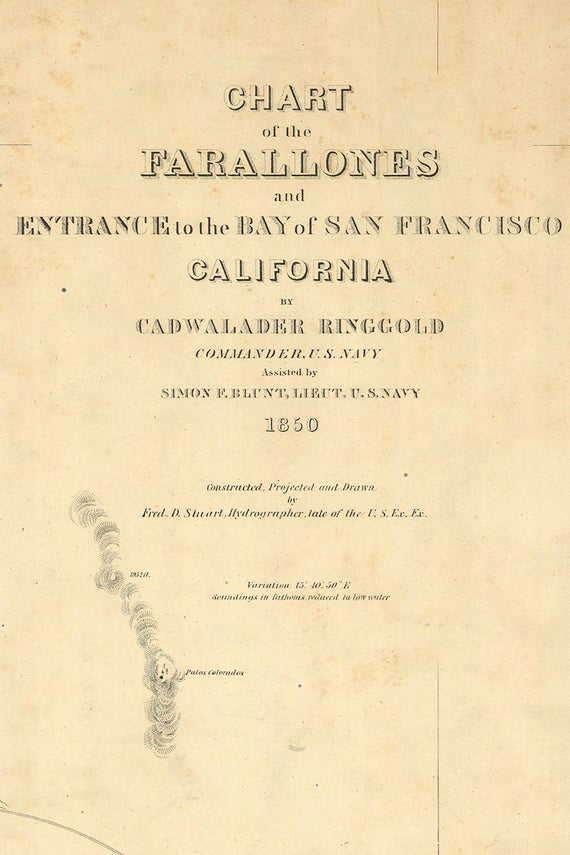

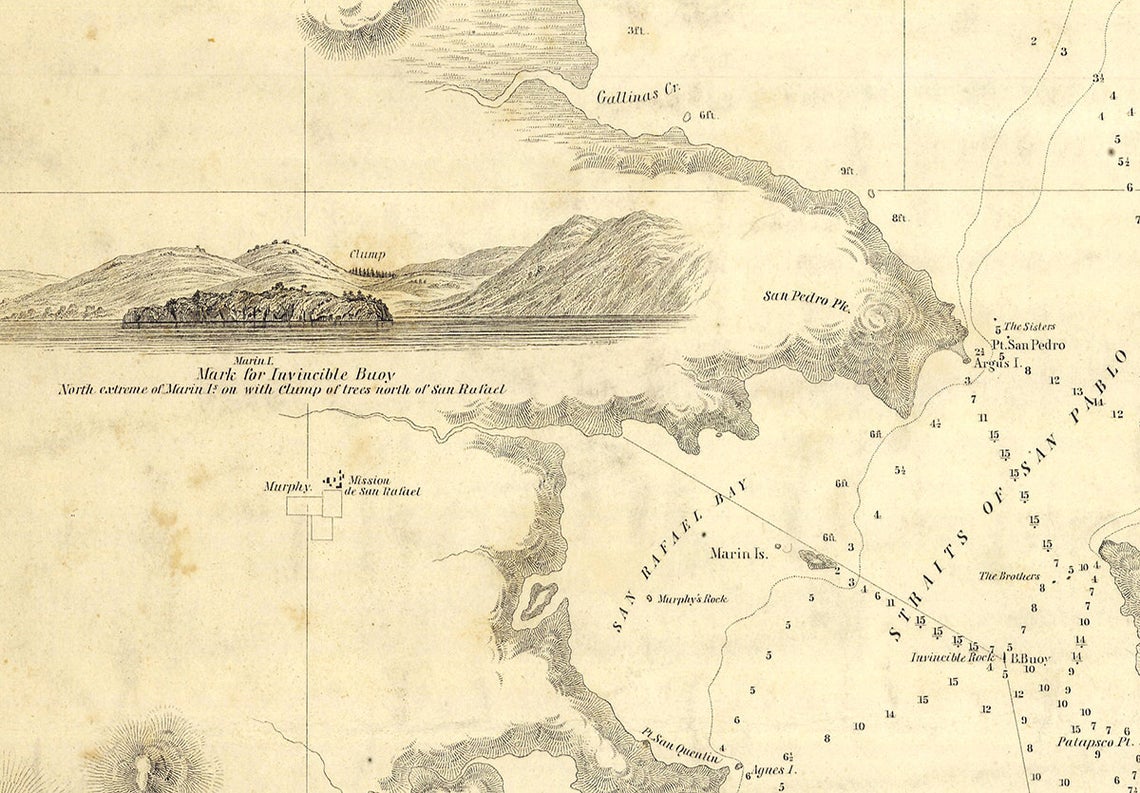

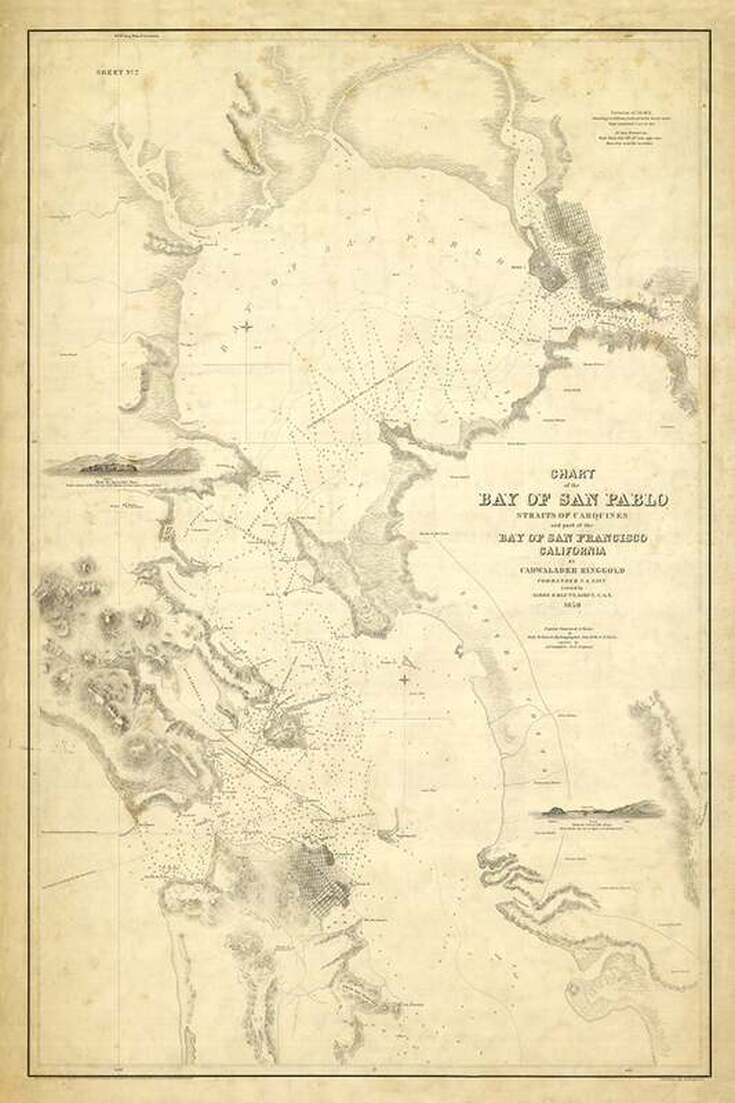

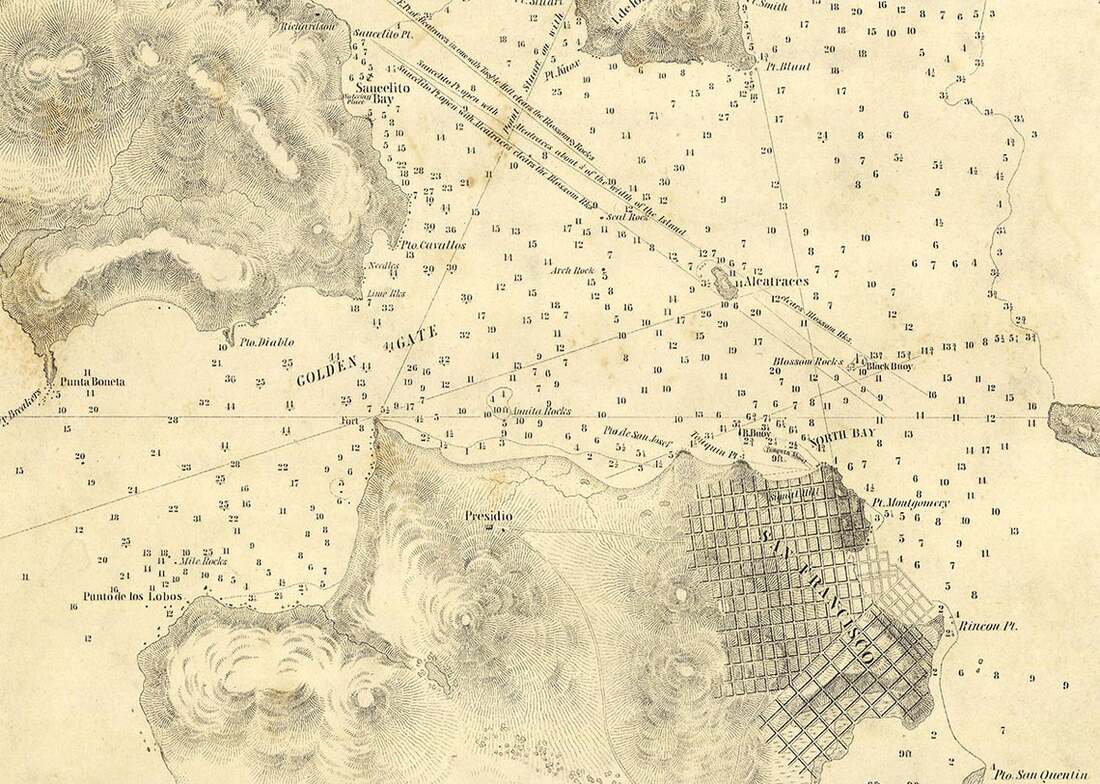

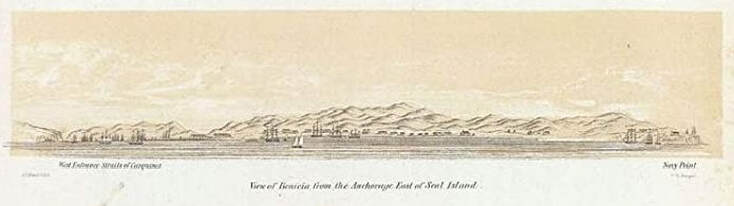

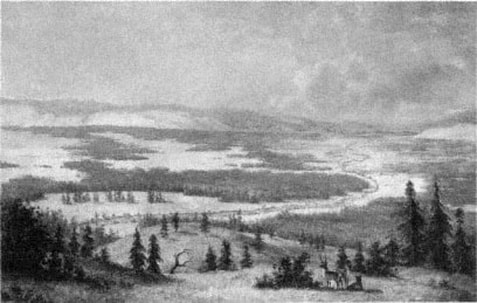

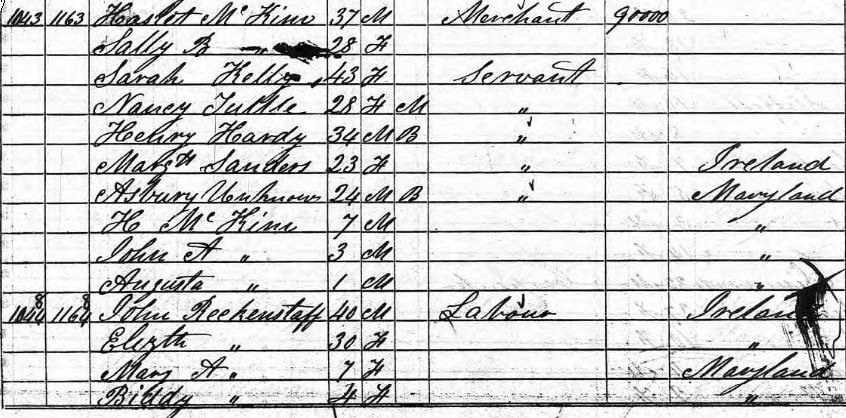

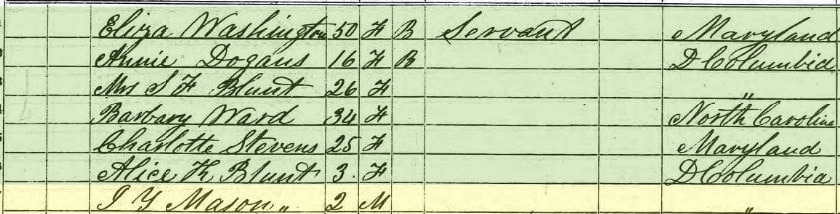

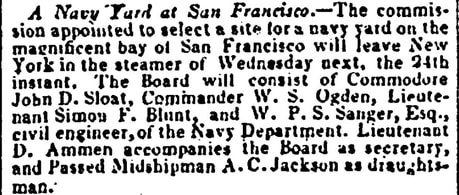

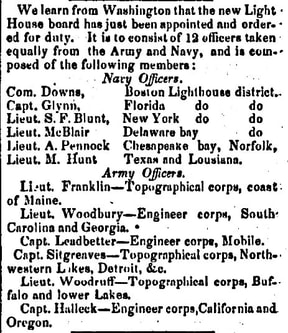

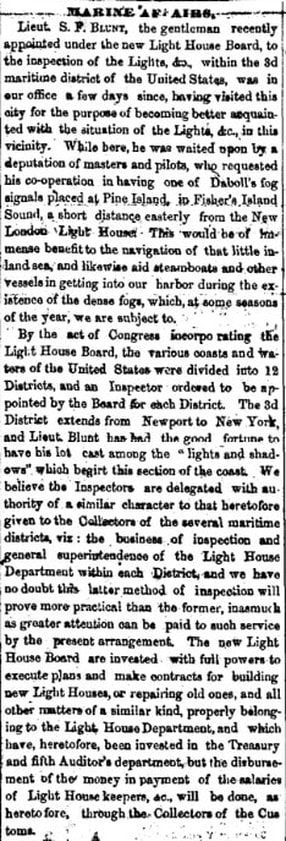

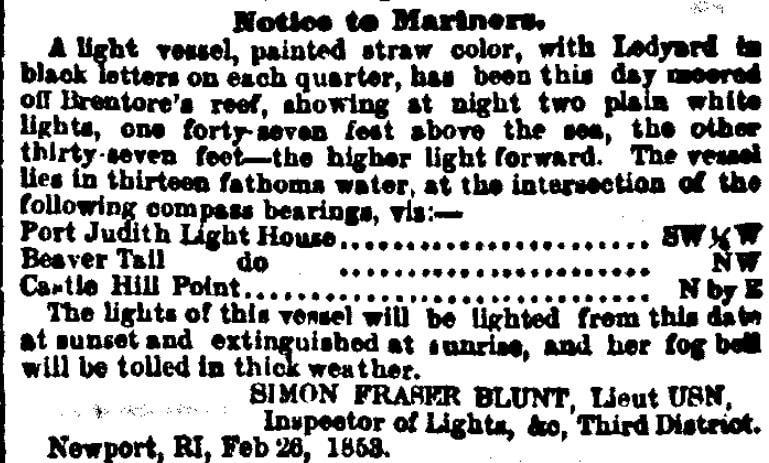

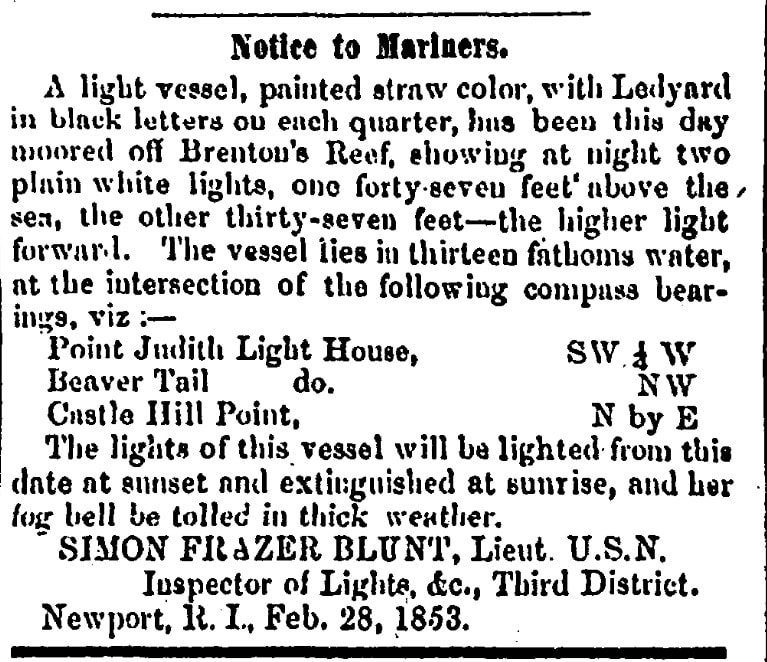

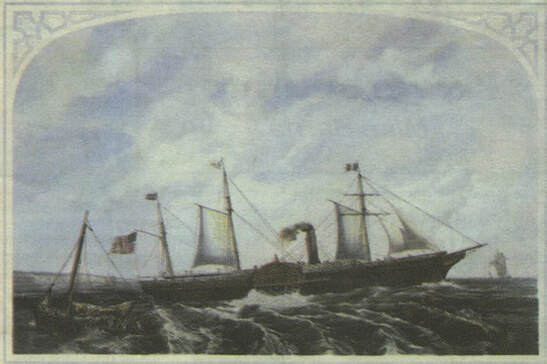

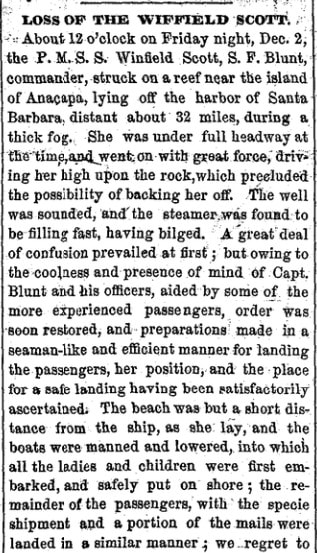

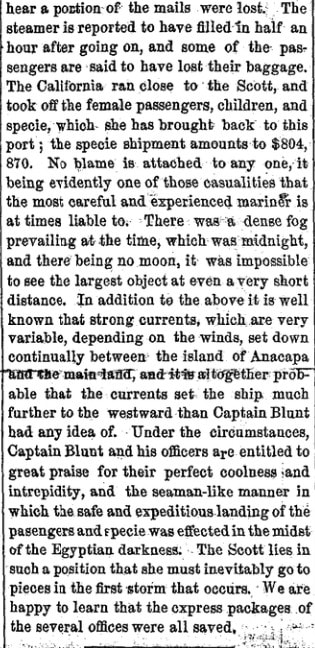

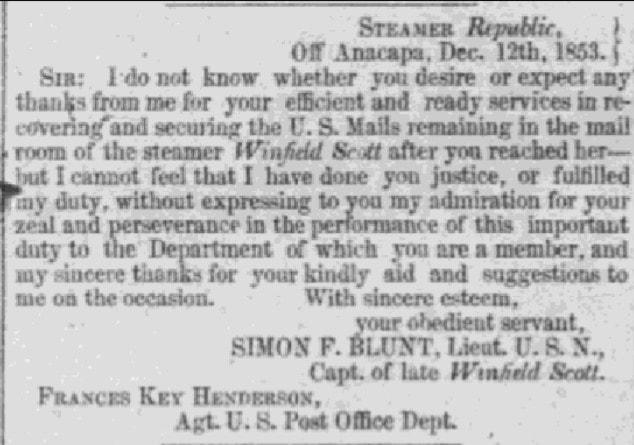

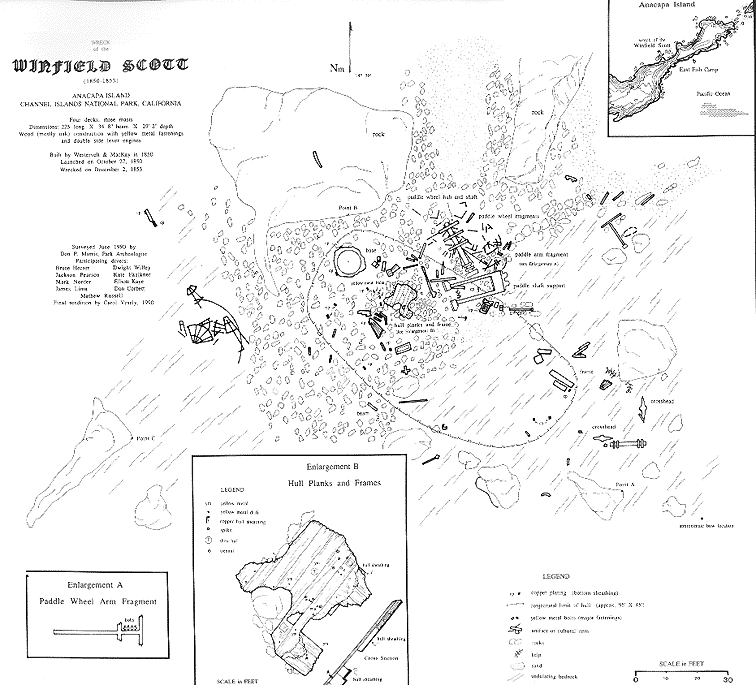

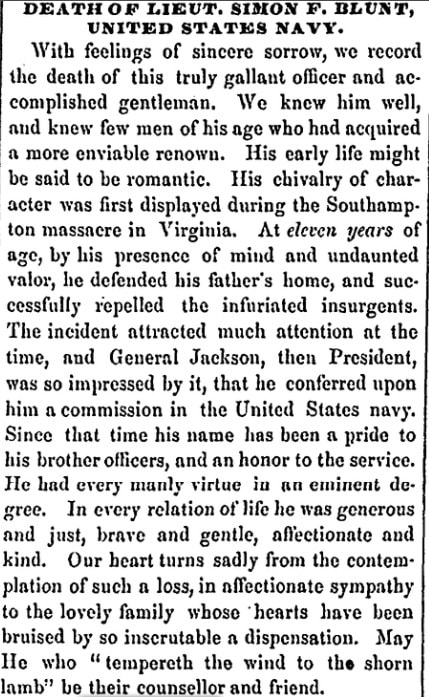

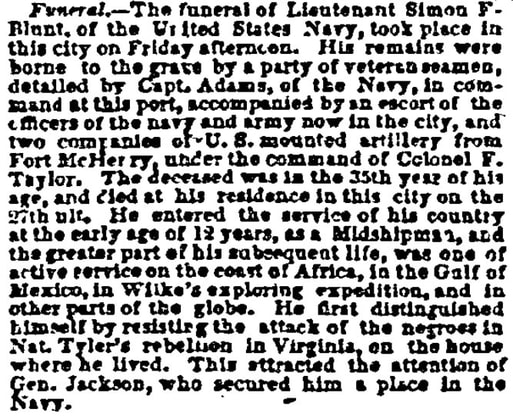

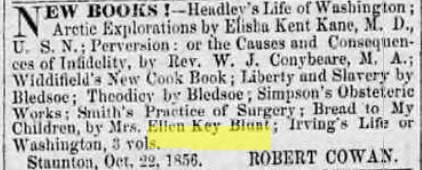

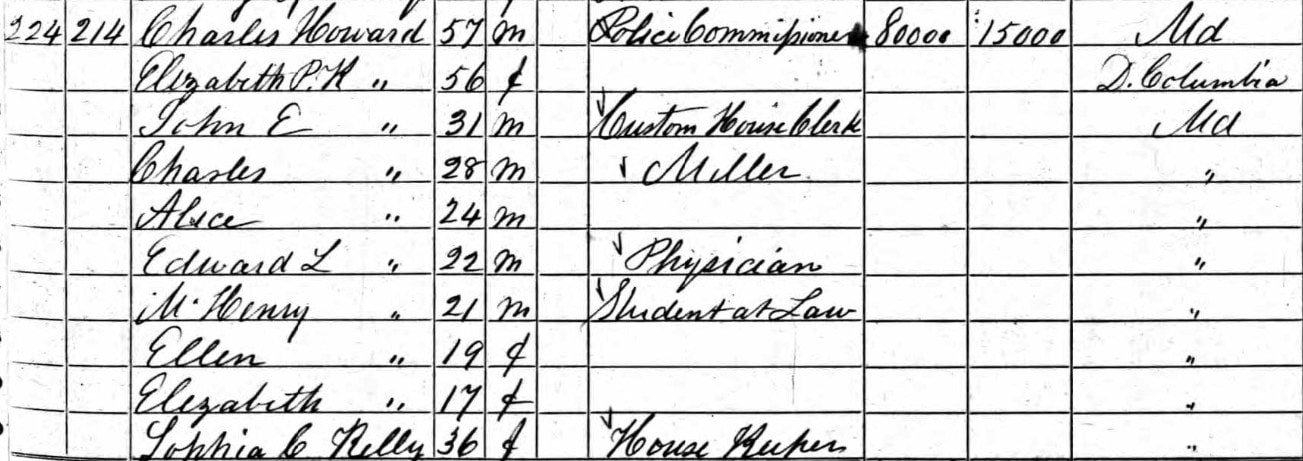

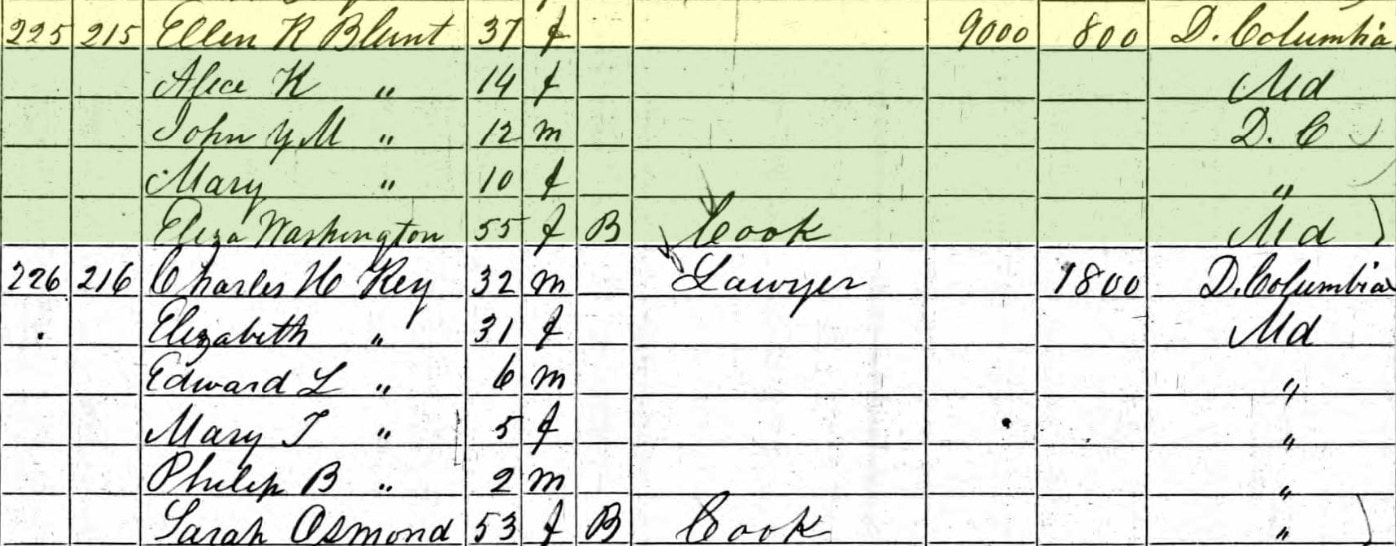

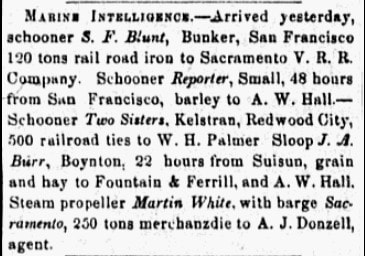

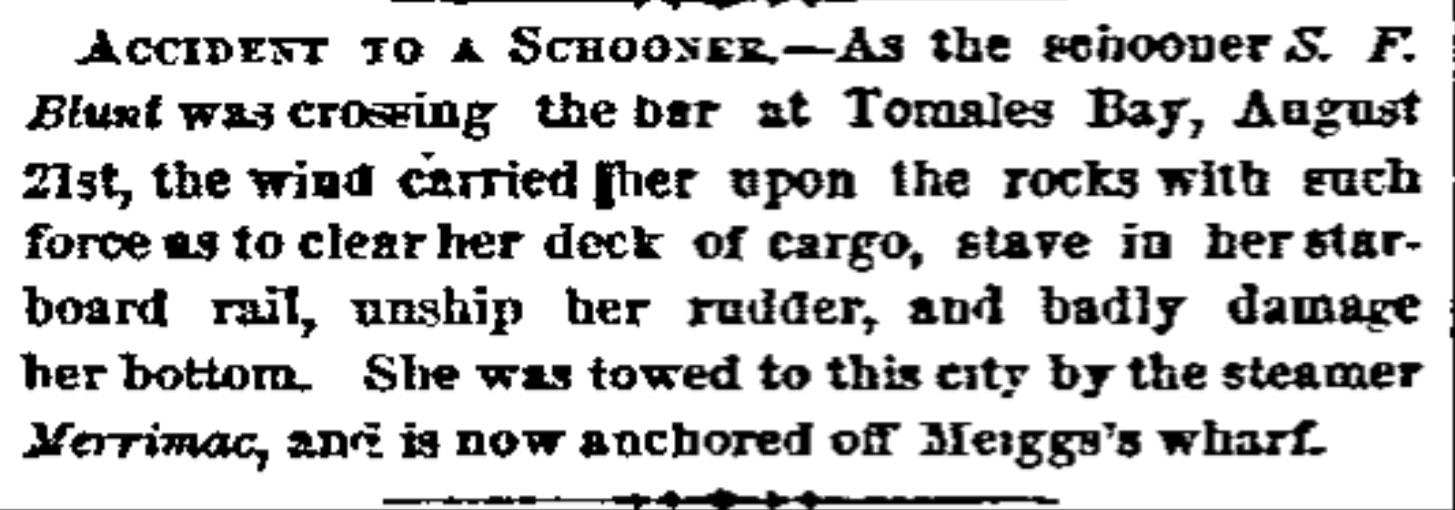

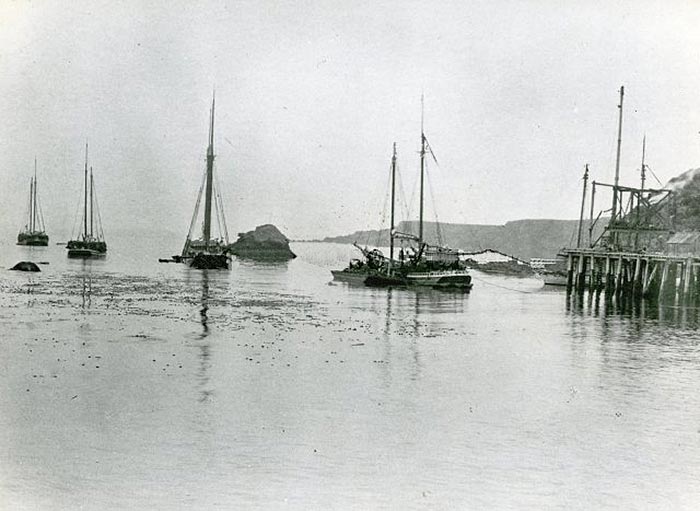

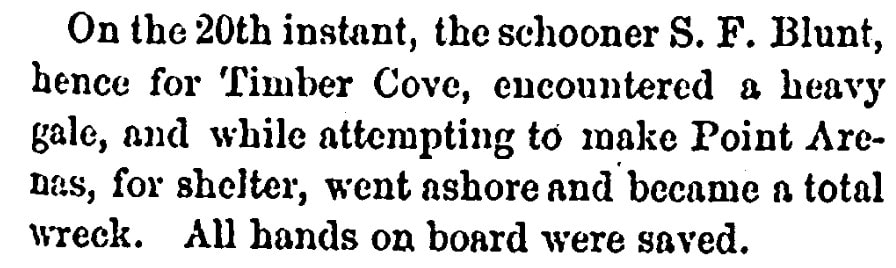

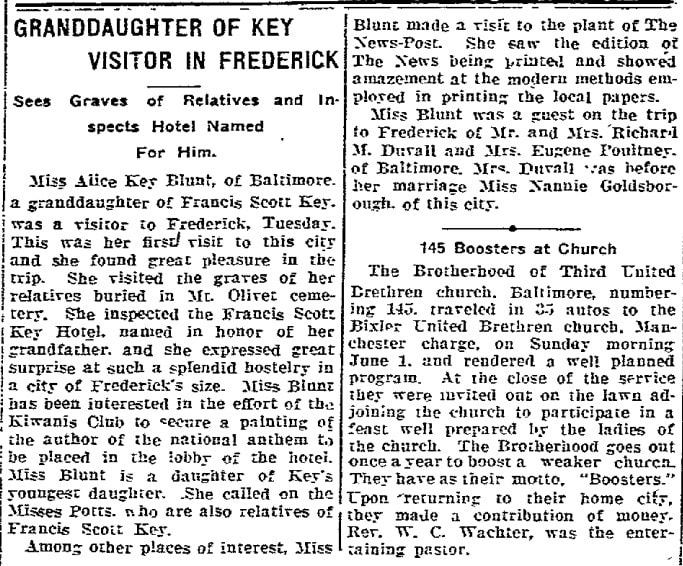

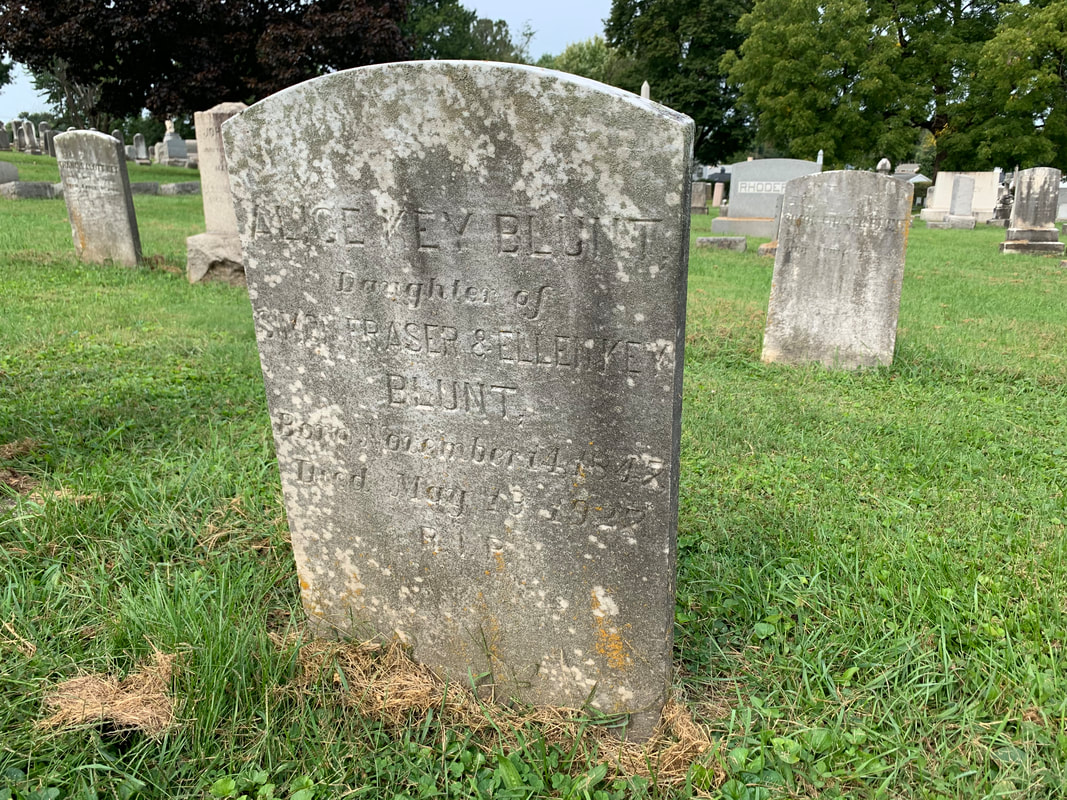

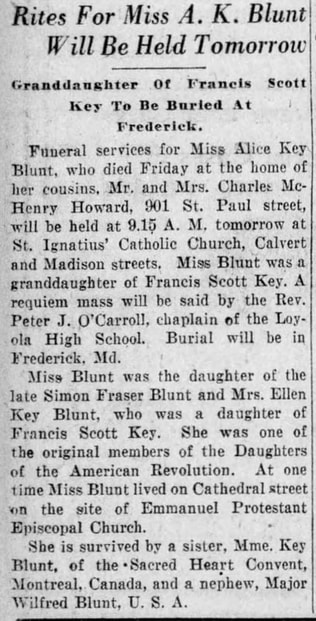

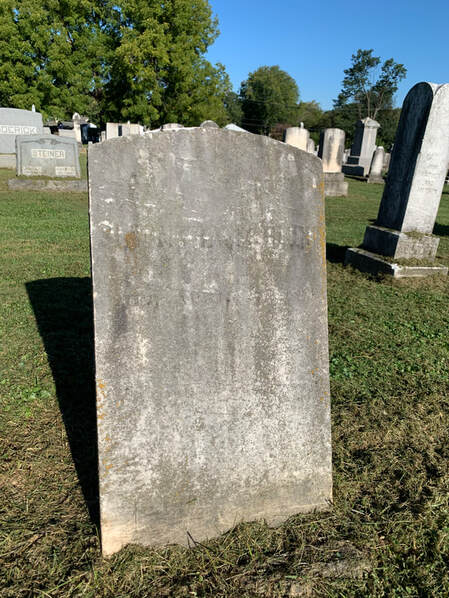

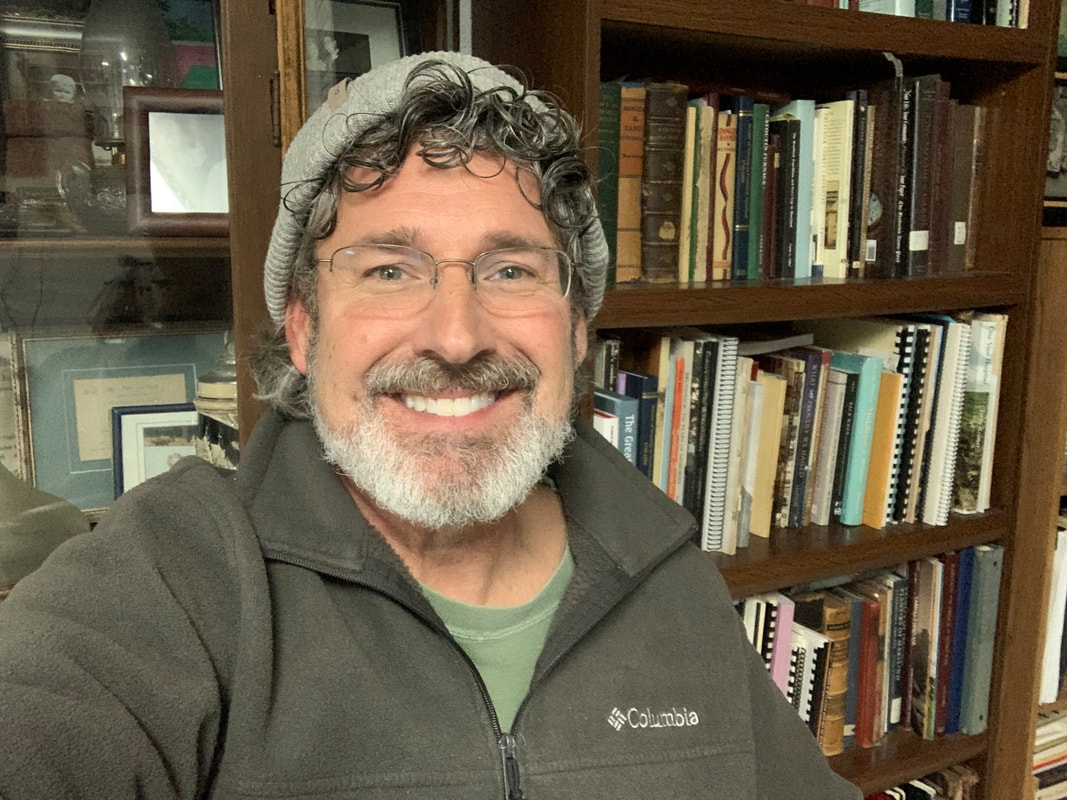

Original Key family combined plot in Mount Olivet's area H/Lot 436 & 439 Original Key family combined plot in Mount Olivet's area H/Lot 436 & 439 "What's in a name?" an age-old question usually credited to William Shakespeare for introducing the proverb to us through Romeo and Juliet. A person's name is said to be the greatest connection to their own identity and individuality. Interestingly, one can walk for hours through a cemetery like Mount Olivet and read hundreds of different names on gravestones and monuments. Some may be familiar and recognizable, perhaps friends, acquaintances, or relatives. However, I would definitively bet that the vast majority of tombstones gazed upon would represent names and people completely foreign to you and, hence, desirous of intrigue and curiosity. Well that's the sole reason I have been doing this blog for almost four years now! Even I have little to no idea of who these people are, what they did, how they died or what they were like. And that's why the hours of research I pour into these stories is so fulfilling, I actually come away not only learning about an individual (usually forgotten over time), but in bringing their memory back to life, I usually learn local, state, national and world history some how. These lives are reflections of the time periods in which they lived, allowing me to see the world through their lens, not manipulated by how we look back today and see/judge things. The above mentioned statement I made about names (A person's name is said to be the greatest connection to their own identity and individuality)really rang true to me last week as I encountered two gentlemen I knew relatively nothing about. However one had a name in which I associated a greater quality of life experience, while the other I thought would be hum-drum and ordinary. In fact, both men's last names also double as adjectives—talk about descriptive irony. The first man was Francis Scott Key, Jr. "Key" when used as an adjective is defined: "of paramount or crucial importance" (ie: The quarterback made a key throw in the final touchdown drive to win the game.") The other gentleman in question is Simon Fraser Blunt. "Blunt" as an adjective is defined as "having a worn-down edge or point; not sharp" (ie: The blunt knife was virtually useless as it couldn't cut anything.") Blunt also has another meaning when it pertains to a person or remark, and means "uncompromisingly forthright." (She was very blunt with her date, saying that there was no need for him to bother asking her out again." Last week’s story focused on a son of Francis Scott Key, one who had the same name as his father, but certainly the opposite fortune of leaving a lasting legacy. To my surprise, Francis Scott Key, Jr. didn’t do anything of particular note outside being a loving husband and father. Newspapers had scarce mentions of him during his lifetime, and he is non-existent in any history book. FSK, Jr.’s proud estate, named “the Elms” in Howard County, is long gone, without a trace. His children really didn't stand out in their own way either. Key, Jr. died in mid-1866 and was first entombed in a graveyard in Baltimore, but would be re-interred a few short months later in Frederick’s Mount Olivet along with his parents and another gentleman (who I am very excited to introduce you too). All four individuals had previously rested within the Howard family vault in Old St. Paul’s Cemetery. Francis Scott Key, Sr. and wife Mary Tayloe Lloyd Key were moved yet again, in 1898, to their present location (within a vault under a fine memorial more befitting the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner,”) by our cemetery's front gate. With this move, the memory and acknowledgement of Francis, Jr. sank further into obscurity as few visitors would travel to the vicinity of his grave and notice his slab of marble. I enjoyed the research challenge nonetheless, and fed my curiosity to learn more about this gentleman and, in the process, more about the immediate family of the guy who wrote our national anthem. I mentioned a fourth individual of the “Key entourage” to be reburied from Baltimore to Mount Olivet back in the year 1866. This was Simon Fraser Blunt, and the exact date of his burial in Mount Olivet’s Area H/lot 439 occurred without fanfare on October 1st, 1866. Mr. Blunt was Francis Scott Key’s son-in-law, having married daughter Ellen Lloyd Key in 1846. Blunt is only about five yards away from brother-in-law FSK, Jr., but a comparison of life stories is “night and day,” as they say. I was astounded with what I found out about Simon Fraser Blunt, and am prepared to show you that although short, he had an adventurous 35 years here on Earth. To be perfectly "blunt," our subject's life was uncompromisingly forthright, and the furthest thing from dull. Simon Fraser Blunt enjoyed a distinguished career in the US Navy, one that would encompass the majority of his life. He was a member of the Wilkes Expedition which explored and surveyed the Pacific Ocean, a cartographer of San Francisco Bay and served as captain of the SS Winfield Scott when it shipwrecked off Anacapa Island in 1853. Two geographic features, Blunt Cove and Point Blunt are thought to be named for him. Yet, there are few, if any, individuals today who have actually ever heard the name of 1st Lt. Simon F. Blunt. In particular, two chapters of his life are particularly amazing and worth telling as these would bookend his Naval career front and back. Blunt Force Simon Fraser Blunt was born August 1st, 1818 in Southampton County, Virginia. His father, Dr. Samuel Blunt, owned a fine plantation named Belmont, located a few miles northeast of the small crossroads town of present-day Capron. According to the 1831 slave census, Dr. Blunt’s father owned nearly 36 slaves. This fact would play out during “the dawn’s early light” on the morning of August 23rd, 1831. Belmont would take part in the bloodiest and best-known slave revolt in American history. Nat Turner (1800-1831), an enslaved black preacher was living at the home of Southampton County craftsman Joseph Travis in the summer of 1831. He had been recently acquired by Mr. Travis, having been bought and sold by a few different slave-owners throughout his life. Having believed he was divinely selected to lead his people out of bondage, Turner took this as a sign in the form of an eclipse of the Sun caused Turner to believe that the hour to strike was near. His plan was to capture the armory at the county seat of Jerusalem, and, having gathered many recruits, to press on to the Dismal Swamp, 30 miles to the east, where capture would be difficult.  On the night of August 21st, together with seven fellow slaves in whom he had put his trust, he launched a campaign of total annihilation, murdering Travis and his family in their sleep and then setting forth on his bloody march toward Jerusalem. In two days and nights about 60 white people were ruthlessly slain. Doomed from the start, Turner’s insurrection was handicapped by lack of discipline among his followers and by the fact that only 80 Blacks rallied to his cause. Just before dawn on August 23rd, Turner and about 20 of his followers had covered a distance of about 15 miles and arrived at Belmont, home of our subject, Simon Fraser Blunt, then having just turned 13 years of age a few weeks prior. Forewarned of the dangers ahead, Dr. Samuel Blunt insisted that his slaves remain and defend the plantation and his family, or join the insurgents. All stayed and successfully defended the home and its occupants. Tradition states that young Simon Blunt fired the first shot at the insurgents, either from the front porch or an upper window as there are two account variations. Belmont would serve as Nat Turner’s “Waterloo” of sorts, and the site of the next-to-last skirmish of the rebellion. Many of his followers had perished upon reaching the Blunt plantation and the remainder were captured and executed upon arrival. Turner, himself, escaped and would be the focus of a multi-month manhunt, before being captured on October 30th, 1831. He was convicted and hanged twelve days later on November 11th, 1831. As an aside, I will share that the Nat Turner rebellion prompted the Virginia General Assembly to spend much of its December 1831 session debating the possible abolition of slavery, something state governor John Floyd had hoped to accomplish. Contrary to Floyd’s wishes, the legislature enacted more stringent slave laws and attempted to suppress abolitionist writings. Turner’s short, but violent revolt, so alarmed the South that a much stricter regimen was soon instituted against slaves and free blacks alike, leading to further hardening of attitudes between the North and South. As Nat Turner had made a name for himself, but lost his life for it, our subject Simon F. Blunt would gain newfound fame and be set on his career path because of Turner’s ill-fated insurrection plot. The plucky teen would be rewarded for his heroism and bravery in battle and summoned to the White House to meet President Andrew Jackson. The president bestowed on the lad immediate commission in the US Navy. His enlistment date states September 7th, 1831. In the Navy What a series of events for 13-year-old Simon F. Blunt—one day he is living peacefully on his father’s plantation, and the next in a fight for his life against Nat Turner, and now he finds himself in the confines of the US Navy. The rebellion attempt on Belmont changed his life incredibly, leading him on a path of world travel on the high seas for the next 23 years. Thankfully (for me), his career in military service is fairly-well documented, but not until 1837, save for one mention in a Philadelphia paper in 1832 mentioning him serving in the Caribbean. I imagine he just "learned the ropes" and trained as a Midshipman on the high seas for those first five to six years in service.  Alexandria (VA) Gazette (Aug 23, 1837) Alexandria (VA) Gazette (Aug 23, 1837) In 1838, Blunt was assigned to the USS Porpoise, under the command of (Washington County native) Captain Cadwalader Ringgold (1811-1867) and passed midshipman on June 23rd before the ship joined the Wilkes Expedition in early August. A passed midshipman, sometimes called as "midshipman, passed", is a term used historically in the 19th century to describe a midshipman who had passed the lieutenant's exam and was eligible for promotion to lieutenant as soon as there was a vacancy in that grade. The Wilkes Expedition is also known as the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 and served as an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands. Funding for the original expedition was requested by President John Quincy Adams in 1828, however, Congress would not implement funding until eight years later. In May 1836, the oceanic exploration voyage was finally authorized by Congress and created by President Andrew Jackson. The expedition is referred to as the "Wilkes Expedition" in honor of its commanding officer, United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. The expedition was of major importance to the growth of science in the United States, in particular the then-young field of oceanography. Lt. Wilkes had a reputation for hydrography, geodesy, and magnetism. Personnel included naturalists, botanists, a mineralogist, a taxidermist, and a philologist. They were carried aboard the sloops-of-war USS Vincennes (780 tons), and USS Peacock (650 tons), the brig USS Porpoise (230 tons), the full-rigged ship Relief, which served as a store-ship, and two schooners, Sea Gull (110 tons) and USS Flying Fish (96 tons), which served as tenders. During the event, armed conflict between Pacific islanders and the expedition was common and dozens of natives were killed in action, as well as a few of the American explorers. In March, 1839, at Orange Bay, Simon Blunt transferred to the USS Vincennes. On January 16th, 1840, the expedition sailed close enough to Antarctica to see the actual continent and it has been said that Blunt Cove is named for him. Going from one temperature extreme to another, the expedition would next visit the Sandwich Islands in the South Pacific. Formerly this group of tropical islands was known to Europeans and Americans as the Sandwich Islands, a name that Captain James Cook chose in honor of the then First Lord of the Admiralty John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. The contemporary name, dating from the 1840s, is derived from the name of the largest island, Hawaiʻi Island. The islands were first known to Europeans after the expedition of Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón in 1527. Interestingly, they would become known to all US residents, and the world to a greater degree, exactly 101 years after the Wilkes Expedition made their explorations. The famous naval station at Pearl Harbor would be established here in 1899, after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and subsequent annexation of the territory in 1893. Our friend, Mr. Blunt, however, would not have the nicest time in paradise. He apparently took sick in April, 1841 in Honolulu, possibly from participating in the trip to the summit of Mauna Loa Volcano. He eventually rallied and made it back home to the US east coast. A few weeks after the expedition had arrived back in New York City, Simon Blunt was promoted to the rank of lieutenant on July 28th, 1842, In 1844, Blunt was assigned to the USS Truxtun which departed Philadelphia in June of that year and would participate in patrolling activities off the coast of Liberia (Africa). In particular, the ship took up station off Tenerife in the Canary Islands to begin duty suppressing the slave trade. This tour lasted 16 months and when Simon returned, the young man attended the newly formed United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.  Cadwalader Ringgold Cadwalader Ringgold Lt. Blunt's time spent back in Annapolis, put him on a collision course with his future wife, Miss Ellen Lloyd Key, daughter of Francis Scott Key. The ninth child of the famous lawyer and songwriter was born in Georgetown in 1821 and was said to have been “especially attractive, a fine writer and even better public speaker.” On January 27th, 1846, Simon married Miss Key in Washington DC. Ellen’s famous father was not in attendance as he had died three years previously. Also absent was Ellen’s older brother, Daniel Key, a former midshipman of Annapolis who was killed in a duel in Bladensburg (MD) in June, 1836 by a fellow Navy midshipman named John Sherburne. It’s highly likely that Blunt and Sherburne knew one another, and quite possible that Simon had met Daniel Key in his younger days as a midshipman of similar age. One more unique connection could have helped “match-make” this particular marriage. Blunt’s former commander and colleague, Cadwalader Ringgold, was the half-brother of Virginia Ringgold Key. The former Miss Ringgold had married Ellen’s older brother, John Ross Key (1809-1837) in 1834. Mr. and Mrs. Blunt went on to have three children: Alice Key Blunt (1847–1927); John Yell Mason Blunt (1849–1910); and Mary Lloyd Key Blunt (1850–?). In 1849, Simon F. Blunt was appointed to a Joint Commission of Army and Navy Officers whose purpose was to identify potential sites for lighthouses and defense facilities along the Pacific Coast of the California and Oregon territories. The Joint Commission consisted of three army engineers: Maj. John L. Smith, Maj Cornelius Austin Ogden and 1st Lt. Danville Leadbetter; and three naval officers: Commodore Louis M. Goldsborough, Commodore G.J. Van Brunt, and Blunt, himself. It had assembled in San Francisco by early April 1849. Blunt, either on his own or with the rest of the members of the Joint Commission, presumably joined his former Captain on the USS Porpoise. This was "Commodore" Cadwalader Ringgold who led an expedition on the chartered brig Col. Fremont in an effort to chart the San Francisco Bay region, suddenly important because of the recent discovery of gold in the area—the Gold Rush of '49. Ringgold is reputed to have named Point Blunt on Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay for our friend Simon. Afterwards, Lt. Blunt assisted Commodore Ringgold in the creation of two charts for the Bay area: Chart of the Farallones and entrance to the Bay of San Francisco, California (1850) Chart of the Bay of San Pablo, Straits of Carquinez, and part of the Bay of San Francisco (1850) Blunt also drew a lithograph, View of Benicia from the anchorage east of Seal Island for Ringgold's Chart of Suisun & Vallejo Bays with the confluence of the rivers Sacramento and San Joaquin, California. A colored version of the lithograph was published in 1852.  The USS Massachusetts (built 1845) The USS Massachusetts (built 1845) A summary of the further activities of this group state the following: The Joint Commission may have been joined by members of the land branch of the Pacific division of the United States Coast Survey. The USS Massachusetts was transferred to the Navy in San Francisco on August 1st, 1849, and detailed for the use of the Joint Commission to take up and down the coast, however they could not recruit a crew. They borrowed some crewmen from another ship and Blunt may have made his second trip to Hawaii, where the Massachusetts wintered and hired native crewmen. Upon its return, the Joint Commission made preliminary recommendations to President Millard Fillmore to reserve various islands and coastal regions in and around San Francisco Bay. Then they and the Massachusetts sailed up to Puget Sound. After a cursory examination of the mouth of the Columbia River, the ship and the Joint Commission returned to California in July 1850. After a trip to San Diego, the Joint Commission made its final recommendation on November 30th, 1850. If Blunt went with the Joint Commission to Hawaii, immediately upon his return he separated from it and the Massachusetts. On March 10th, 1850 Blunt was in command of the Schooner Arabian with another military survey party en-route to Trinidad Bay. Upon reaching the bay, a boat with a landing party from the schooner swamped, resulting in the drowning of five men. Five more men survived. Blunt appears to have continued to the Columbia River and explored the Willamette Valley, and by August 1st, 1850, to have attached to the Survey Schooner Ewing of the Pacific Coast Survey. In a letter of that time period from William Pope McArthur (the first leader of the hydrographic branch of the Pacific Coast Survey) to his father-in-law, Commander John J. Young, McArthur wrote of his group’s foray into what had been recognized officially as the Oregon Territory in 1848: "Lt. Blunt who is now with me has traveled considerably through the country (the Willamette Valley) and is so much pleased with it, that he has taken a section of land and made a regular claim to it, he has also taken one for myself and one for Lt. Bartlett, both adjoining his!"  San Francisco San Francisco The forementioned Lt. McArthur was commander of USS Ewing, and Washington Allon Bartlett was one of its officers. By August 31st, 1850, the USS Ewing had already worked its way south to San Diego. At the end of December 1850, the USS Ewing was severely damaged in a storm while attempting to take the new land branch of the Pacific Coast Survey to Monterey Bay. Upon her repair, she traveled up the coast to the Columbia River. If Blunt was with still with the USS Ewing, he was back by early to mid-summer of 1851, when he was a signer of the constitution of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance. This was a vigilante group formed in response to rampant crime and municipal government corruption in a town that had grown from 900 residents to over 20,000 in a short period thanks to the famed Gold Rush. While here, Blunt spent time with friend John Charles and wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, at their home in the same city. Frémont (1813-1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He had recently been elected a US Senator from California, and later in 1856 would become the first Republican nominee for President of the United States. Simon likely discussed with the couple an idea that he was developing that would help lower lifeboats into the water from ships. This would be foreshadowing at its very best. Meanwhile, I wondered what was occurring with Lt. Blunt's young family back east? At the very least in the year 1850, I found Ellen Key Blunt and Simon’s children living in Baltimore in the large household of Haslett McKim, a wealthy businessman, banker and broker. The residence was located at 27 West Franklin Street, not far from the Baltimore Cathedral. I'm assuming that based on the life of a sailing man, more time for the couple was spent apart than together. Perhaps Ellen traveled out to see him on the west coast? Or maybe a furlough home at some point was enjoyed for the young US Navy veteran with a decade's service logged up to this point. Simon would be back home soon, but not for long. On January 15th, 1852, Secretary of the Navy, Will A. Graham ordered a Naval Commission to select a site for a west coast naval yard. Simon F. Blunt, along with Commodore John Drake Sloat, Commodore Cadwalader Ringgold, and William P.S. Sanger (former overseer of construction of Drydock Number One, Norfolk Naval Shipyard) were appointed to the commission. On July 13, 1852, Sloat recommended the island across the Napa River from the settlement of Vallejo, as it was "free from ocean gales and from floods and freshets." The Navy Department acted favorably on Commodore Sloat's recommendations and Mare Island was purchased for use as a naval shipyard in July 1853 at a cost of $83,410. On September 16, 1854, Mare Island became the first permanent US naval installation on the west coast, with Commodore David Farragut, as Mare Island's first commander. Lt. Blunt was reunited with his family for the Christmas holidays of 1852. The following year of 1853 would prove another busy year for Simon Fraser Blunt. It began with him being named to the new, national Light House Board, in which he would oversee the New York district. It appears that Blunt had a home in Washington, DC, but had made a permanent move to New York, and I assume that his family was in the plan as well, but I'm not positive about this. I do know that he was soon to work inspecting and building lighthouses with particular focus on the Long Island Sound and vicinity.  Not so “Golden” Moment Somehow, Simon F. Blunt switched gears and left lighthouse inspection to become a steamship captain. I don't know if it was just a factor of his tenure expiring after the initial review of lighthouses or not, but he was now going to shuttle back and forth to the west coast. By mid-1853, Lt. Blunt had been hired as the captain of the SS Winfield Scott, which carried passengers, mail and cargo between San Francisco and Panama. The discovery of gold in California brought thousands of fortune seekers from the east and around the world. To meet this new demand for travel and resources, shipping and maritime activity increased dramatically. Sailing ships and steamers carried people, food, and supplies up and down the coast and from the eastern United States. A typical voyage from New York to San Francisco brought passengers first to Panama and, once there, it often took over a month for another ship to arrive and take them up the Pacific seaboard. In 1847 two steamship companies connecting New York with San Francisco and the Oregon Territory and charged primarily with the important task of delivering mail were subsidized by the federal government. The Steamship Company and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company acquired many steamships to travel the Panama route. Independent steamship companies competed with the mail steamships by promising shorter voyages. To reach their destinations more quickly, ships often risked navigating the narrow Santa Barbara Channel rather than traveling around the Channel Islands. The Winfield Scott was owned by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Loaded with over 300 passengers and crew, bags of mail, and between $1-$2 million in gold, the steamship departed San Francisco for Panama on December 1st, 1853. The next evening Captain Blunt chose to pass through the Santa Barbara Channel to save time. The fog was dense, but he knew his course. Believing he had passed the islands, Blunt turned southeast, an unfortunate and tragic miscalculation. At 11:00 pm, the Winfield Scott crashed into a large rock off Middle Anacapa Island at full speed, striking two holes in the bow. The stern then struck, knocking away the rudder, and the ship began to sink.  Asa Cyrus Call Asa Cyrus Call Captain Blunt sent a boat to find a place onshore for the passengers and ordered everyone on board to abandon ship. The large group was brought to the beaches of Anacapa where they camped for nearly a week. Another ship, the California, saw the smoke from the passengers’ fires and rescued the women. It returned on December 9th and removed the rest of the passengers. The company of the Winfield Scott was left on the island to attempt to recover mail, baggage, furniture, and some of the machinery from the wreck, but there was little hope of saving the ship or of getting it off of the ledge. An eyewitness account by one of the passengers, an Ohio native named Asa Cyrus Call (1826-1888),can be found online thanks to descendants John and Virginia Call who transcribed/published Cyrus’ diaries (kept between 1850-1853) back in 1998:  The initial departure of the USS Winfied Scott The initial departure of the USS Winfied Scott The Winfield Scott Dec. 5th, 1853. A rock in the Pacific, 20 miles from the coast - Monday, Dec. 5th, 1853. I embarked on the Steamer Winfield Scott last Thursday, and at 12 o’clock we left Vally’s St. Wharf for Panama. We had fine weather till Friday evening, when it became foggy. One of the boilers had been leaking through the day which had retarded our progress, and the Sierra Navada had passed us, but it was repaired on Friday afternoon, and we were running about twelve miles an hour, when I went to bed on Friday night. This was about 9 o’clock. I had just got to sleep, when I was awakened by a tremendous shock. I knew we had struck a rock and hurrying on a part of my clothes I hurried up on deck where I found a general panic, but the steamer was backed off and with the assurance that all was right the most of the passengers retired again to their rooms. But I didn’t believe she could have struck a rock with such force without sustaining some injury, and not knowing what the upshot of the matter might be, I went down to my state room and put my money and all other valuables in my trunk into my saddle bags, and went into the upper saloon intending to be ready for what was to come next. I had hardly taken a seat when the steamer struck again, and with such force, that it seemed as if the ship was breaking into a thousand fragments. I again hurried on deck, and went forward to see if I could see land. It was so dark I could see nothing, but I could distinctly hear the roar of the breakers ahead, and on the larboard side. The steamer was unmanageable, and the order was given to let off the steam and to extinguish the fires to prevent the ship's taking fire. The decks were densely crowded but considering the circumstances the people behaved remarkably well. It was a perfect jam. And all I could distinguish was an occasional small shriek as the ship lurched to one side giving evidence that she was sinking. About ten minutes after we last struck the long boat was lowered, and I heard the Captain call for the ladies to go aboard. Some men pressed towards the boat but the Captain’s orders were “knock the first man overboard that attempts to get into the boat.” Meanwhile some life preservers were got up and were being distributed among the passengers. There was now a great breach in the steamer and the water pouring in like a river. Our only hope was that she might not sink entirely, as we could feel her sliding down the side of a ledge of rocks. Pretty soon the fog began to break away a little and we could see the light in the longboat as she was coasting along in search of a landing. We could also see the top of a high peak just ahead of the ship and pretty near, but it seemed perpendicular and the white foam and the roar showed that we could never hope to land there. As soon as the life preservers were distributed, the other ships boats (five) were lowered, and filled with passengers. They all held about one hundred and fifty, and there were five hundred and twenty on board. After being gone about half an hour, the long boat returned, having found a landing. And in about two hours all hands were taken off, and were landed on a rock about fifty yards long by twenty five wide. The next day we came to a larger rock or Island, about half a mile long by 100 yards wide. We have succeeded in getting provisions and water enough from the wreck to do us so far. The sea has been quite smooth, or we should have been all lost. A boat went off to the mainland day before yesterday and returned last eve. An express has been sent to San Francisco and I shall look for a steamer in three or four days. Robbery and plunder has been the order of the day since the wreck. But today we appointed a committee of investigation and have had everything searched. A good deal of property has come to light, and two thieves have been flogged. I have recovered a pair of revolvers, a Bowie knife, and some clothing, but I am a good deal out of pocket yet. But probably my other things never came ashore. We are on short allowance, but I today shot a seal with my pistol, and we shall have a luscious dinner. We are expecting a schooner from the main land with supplies of water and provisions. December 9th 7 p.m. The old steamer California came to our rock sometime in the night last night, and made her presence known by firing cannon. We climbed to the top of the rock and made a large fire of weeds, which is the only fuel we have on the rock. The sea was very rough which made it dangerous getting onboard, but we finally accomplished it without any very serious accident. It is now supposed that there were one or two men lost when we were wrecked, as they have never been seen since. One was a Mr. Underwood, a butcher by trade. After seeing to the rescue of the passengers and salvage of the mail and cargo, Captain Blunt continued “to Atlantic States on a visit to his family and for the purpose of representing in person, the loss of the steamer of which he formerly had commanded." Blunt would be cleared of any wrongdoing. An article from the time gives the sentiment of the passengers in regards to the accident. As an aside, between 1850 and 1900, at least 33 ships were wrecked in the same Channel. The Winfield Scott still lies beneath the clear waters of Channel Islands National Park. Divers regularly visit it still to this day. Simon Fraser Blunt and the passengers of the USS Winfield Scott made it back to New York City on January 29th, 1854 as evidenced by two news mentions in the New York Herald. Sadly, this would be Simon Fraser Blunt’s last big adventure. I don’t know how he spent his last four months after returning home to the east coast from California, but he would die in Baltimore on April 27th, 1854 at the age of 35. His funeral was covered by the Baltimore Sun as his mortal remains were placed alongside his famous father-in-law within the Howard family vault in Old St Paul’s Cemetery in Baltimore. To support herself, and her children, Ellen Blunt worked as a copyist for the US Patent Office , where, by 1855, Patent Commissioner Charles Mason was employing four women clerks, including Clara Barton, who later founded the American Red Cross. In mid-1855, however, when Mr. Mason resigned, the women were forced to work at home because Secretary of the Interior Robert McClelland, who had assumed supervision of the Patents Office, objected to "the obvious impropriety in the mixing of the two sexes within the walls of a public office." Their pay was reduced to the piecework rate of ten cents per hundred words, and during some of the following months, they were given little or no work at all. Interestingly, Ellen was the subject of a March 7th, 1856 letter by Jessie Benton Frémont (wife of the fore-mentioned California Senator and presidential candidate) to Washington DC socialite and “Navy commander wife” Elizabeth Blair Lee. In this correspondence, Mrs. Fremont laments Ellen Key Blunt's financial situation, one that took a nose-dive following the sudden loss of her husband (Simon). Frémont attempted to intervene on Blunt's behalf by writing to George W. Blunt, a prominent publisher of nautical charts and maps (with no known relationship to Simon Blunt), imploring him to buy a patent for a device developed by Simon Blunt to lower lifeboats into the water. By the end of 1859, Frémont was somehow exasperated with George Blunt and “gave up the ship” so to speak. Mrs. Blunt made ends meet by writing and lecturing around the east. She received help from her siblings, as her sister Mary Key Pendleton helped her reputation in her home of Cincinnati, Ohio. By decade's end, Ellen and her three children could be found living with her sister, Elizabeth Howard, and brother, Charles Key, in Baltimore at Mount Vernon Place. The home must have been a great scene of sadness at the time of brother Philip Barton Key's murder (February 27th, 1859) by New York congressman Daniel Sickles. The subsequent court proceedings, in which Sickles would be acquitted, was said to have been the trial of the century and featured the first successful use of the temporary insanity plea–but that's a story for another day. Thankfully, the Key children's mother, Mary Tayloe Lloyd Key would be spared from enduring the trial as she died on May 18th, 1859 at the age of 74. Ellen would relocate to Paris in 1861. While there she gave dramatic readings or her works. She most likely moved due to the American Civil War and the instability of both Baltimore and Washington, DC at that time. The family was Southern leaning and some of her poems and essays reflect this sentiment wholeheartedly. Her reputation was preceded by her father's patriotic tune, and her brother's brutal murder. While in Paris, she must have okayed the move of Blunt’s body in October, 1866 to Frederick, Maryland. He would be buried in the new Key family plot in Area H/Lot 439. This was made possible by Fredericktonian George Murdoch Potts who it is said persuaded two of Francis Scott Key’s daughters to move the patriot’s body back to his native Frederick for re-interment in the town’s new cemetery, opened just 12 years earlier. Key, his wife Mary, son Francis Scott Key, Jr. and Simon F. Blunt were buried here on October 6th, 1866 after being brought from Baltimore aboard train. Blunt's Lasting Legacy The schooner the S F Blunt was built in 1854-1855 at Puget Sound by William Ireland. It would make many journeys off the coast of northern California, especially between San Francisco and Sacramento. You may think of California's capital city as being far inland from the coast. This is true, but the real city of Sacramento was developed around a wharf, called the Embarcadero, on the confluence of the American River and Sacramento River which had been developed in 1849 as a result of gold discoveries at Sutter's Mill in the area of Coloma. The port was used increasingly as a point of debarkation for prospecting Argonauts heading eastwards, and supplies were readily needed. Unfortunately the S F Blunt would suffer a series of mishaps. It became waterlogged at Albion, California in November, 1862. Another accident occurred in 1865 in Tomales Bay. The two-masted sailing schooner was repaired and would sail another day until it was waterlogged again off the Mendocino Coast in May, 1868. This was the proverbial "strike three!," as the schooner was refloated and wrecked off Point Arena in 1868. Simon F. Blunt's journal and a collection of his letters are archived in a collection in his name at the Virginia Historical Society. More letters can be found in the Mason Family Papers, 1825–1902 collection at the same institution. Simon and Ellen’s son and grandson are buried in Arlington Cemetery. John Yell Mason Blunt, received his education in Washington and Paris. He was fluent in English, French, Spanish, and German and the author of two books: Maxims for Training Remount Horses for Military Purposes, and An Army Officer's Philippine Studies. John was 12 when he and his two sisters moved to Europe. While still a teenager, John enlisted in the French Army and became a member of the Red Cross Corps. He later transferred to the Papal Zouaves, a unit formed by the Papal States to fight their incorporation into the new Kingdom of Italy. John was among the last troops to surrender when the Italians took Rome in 1870. John returned to France with a French unit of the Papal Zouaves, and fought in the Franco-Prussian War. Subsequently, he lived with his mother in Paris during the Commune of 1871. He next went to Spain and fought as a cavalry captain in the Carlist War of 1872 and 1873 on the side of Juan Carlos, the Pretender to the Spanish throne. After the war, he remained in the service of Juan Carlos in Paris and Marseilles until 1880. At this time John's mother moved to Great Britain for health reasons. Accompanying her, he joined the British Army and served in the First Royal Dragoons, a cavalry unit that did police work. Meanwhile Ellen continued her writing and elocution opportunities throughout Europe. Ellen Key Blunt died on March 30th, 1884 in the coastal resort town of Tendy, Wales. I assume she was buried here instead of being brought back to the United States and laid by her husband’s side in Mount Olivet. I couldn’t find her exact burial location. Following his mother's death, John Y. M. Blunt resigned from his British employment and returned to the United States. He joined the US Army and served in the cavalry. He rose again to the rank of captain, serving in Maryland, Kansas, Cuba, and the Philippines. He retired in Manila after seventeen years of service in 1902. John remained in Manila and worked as a translator in the Philippine Constabulary until his final illness and death in 1910.  John’s son, Wilfrid Blunt was a veteran of World War I and World II, having graduated from the US Military academy at West Point in 1911. During World War II, he was the commander of Camp Carson in Colorado Springs, CO. He would retire in 1948. Simon Blunt had two daughters, Alice Key Blunt and Mary Lloyd Blunt. Neither daughter married, but led very different lives. The former traveled extensively and lived with relatives, and in various hotels in Baltimore throughout her adult life. She spent summers in Canada, which afforded opportunities to visit her sister. Ms. Blunt was quite active in patriotic affairs and regularly sat on planning and social committees in her home of Baltimore. In fact, she was co-founder of the Baltimore Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution in March 1892. This group is also known (fittingly) as the Francis Scott Key Chapter. Ms. Blunt would serve as Maryland's second state regent in 1894, and was followed in succession by Betty Maulsby Ritchie, founder of the Frederick Chapter, DAR and buried only 30 yards to the south of Mrs. Blunt's gravesite. Alice Key Blunt was the subject of a Frederick News article in early summer of 1924 in which she visited her grandfather's hometown and made a visit to Mount Olivet to see the graves of her father, uncle and grandparents. The town and garden cemetery must have made a good impression on her, as she would choose to be buried here three years later. Alice Key Blunt would die on May 13th, 1927 at Baltimore's Hotel Sherwood. She is buried here in Area H directly in front of her seafaring father. I couldn’t find Mary Blunt’s grave, but from John Y. M. Blunt’s obit, I learned that she was a nun and teacher in Montreal. I found Sister Mary Blunt in the 1921 Canadian Census living at Sacred Heart Roman Catholic School and Convent. The Sacred Heart School of Montreal was founded in 1861, and built around the principles that were at the core of the Society of the Sacred Heart, which was begun by Saint Madeleine Sophie Barat in 1800. Among those principles was to educate girls to take part in society beyond the home or the church. I’m assuming that Mary’s time abroad in Europe likely influenced her to become a sister. One more individual of note is buried in this Key plot in Area H. In between the graves of Simon Blunt and his brother-in-law, Francis Scott Key, Jr., lies the grave of a nephew to both gentlemen—John Ross Key III (1837-1920). I wrote a story about this talented fellow back in July, 2019 entitled “Star-Spangled Artist.” John Ross Key III was a world class painter and grandson of Francis Scott Key. He was born in Hagerstown on July 16th, 1837, two months after the death of his father, John Ross Key II (1809-1837). Young Key’s mother, Virginia Ringgold Key (1815-1903), was the sister of Commodore Cadwalader Ringgold, a continual figure in the life and career of Simon Fraser Blunt.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed