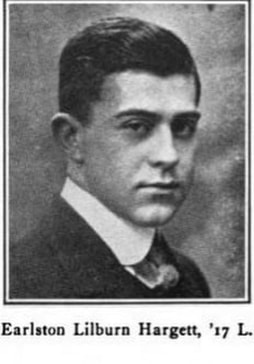

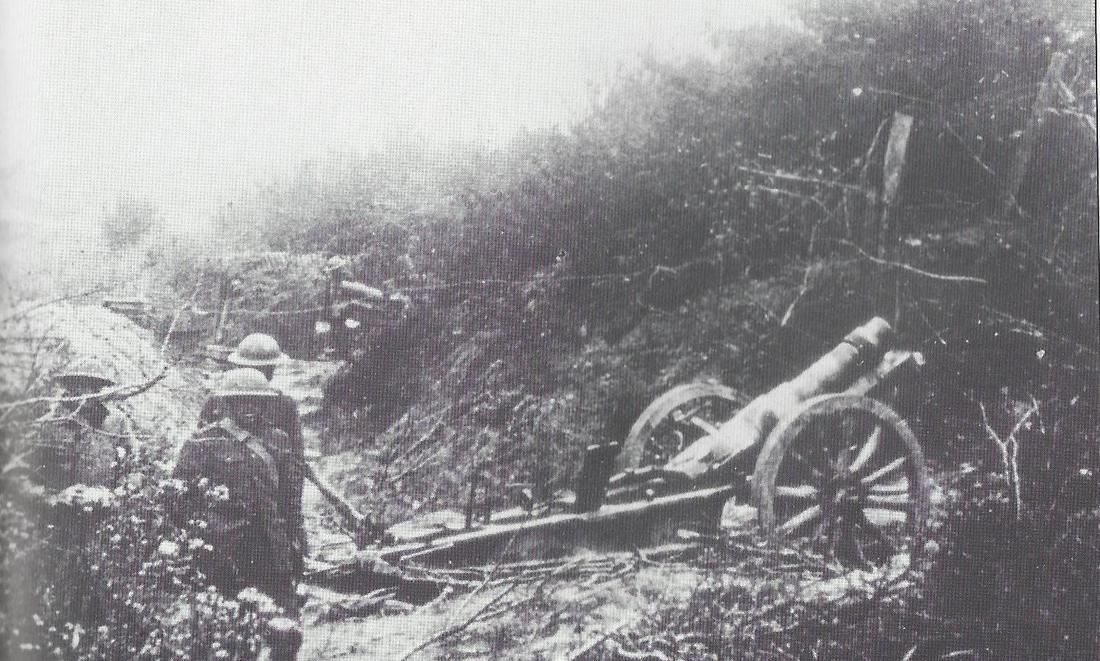

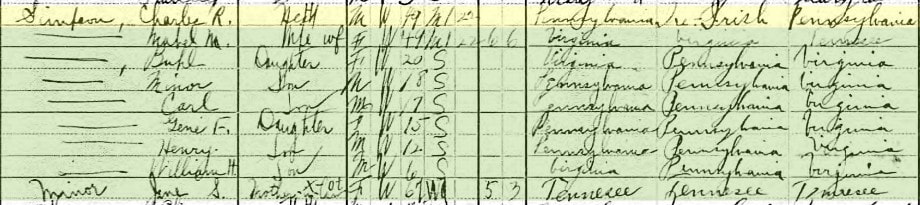

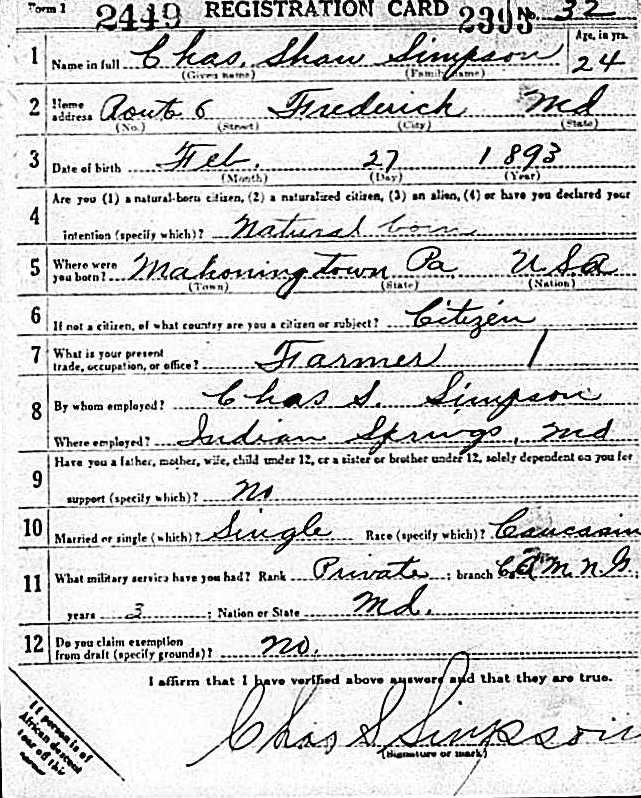

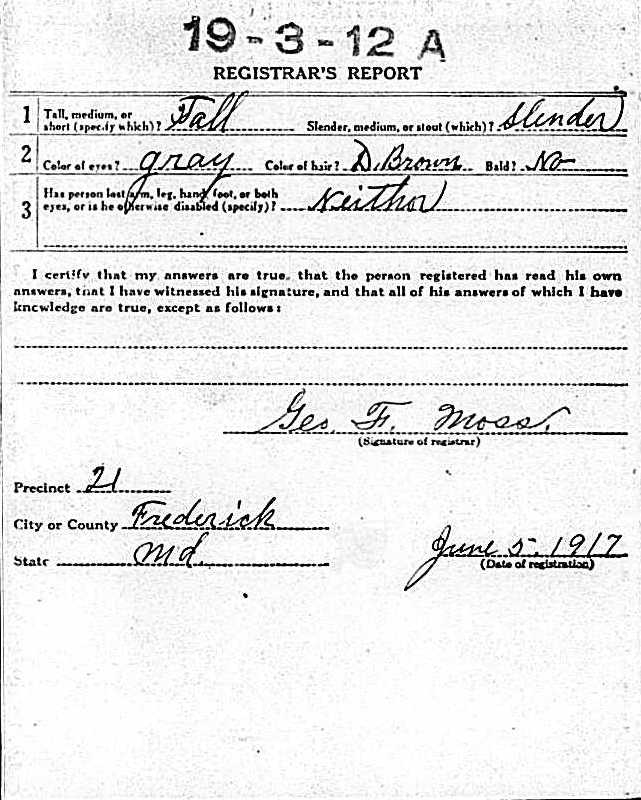

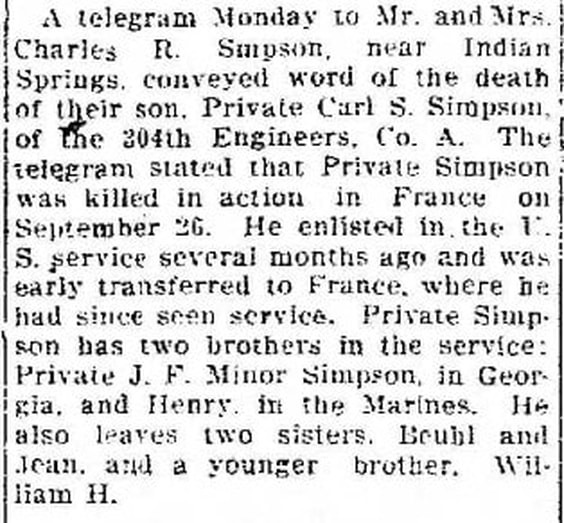

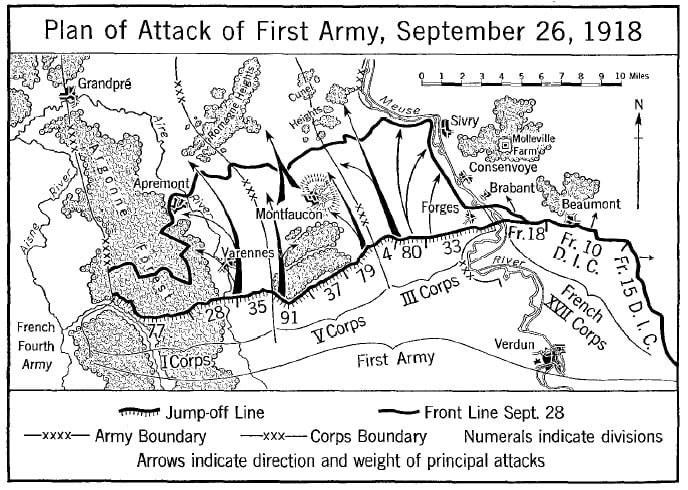

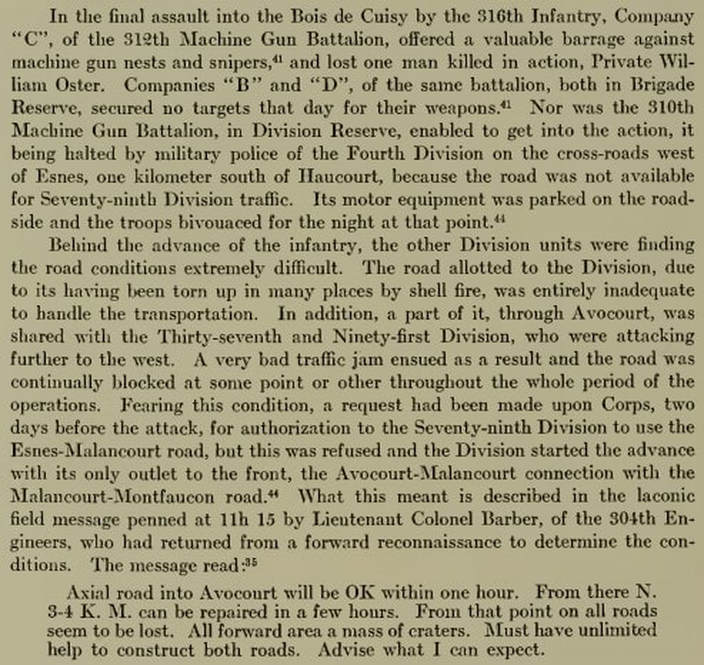

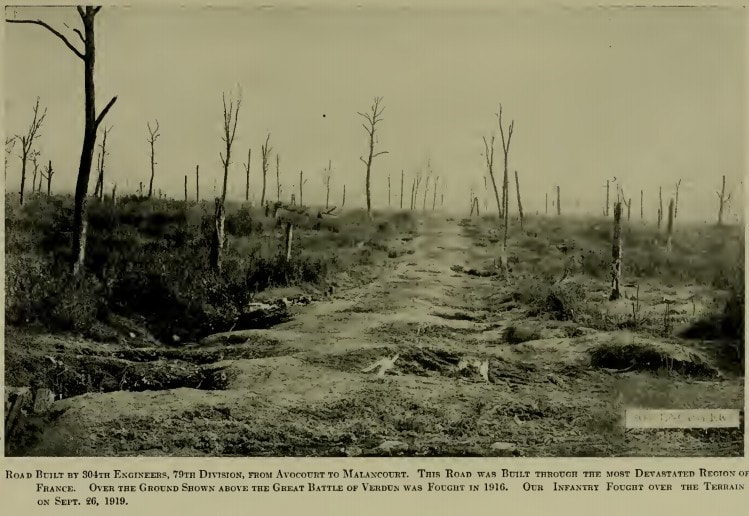

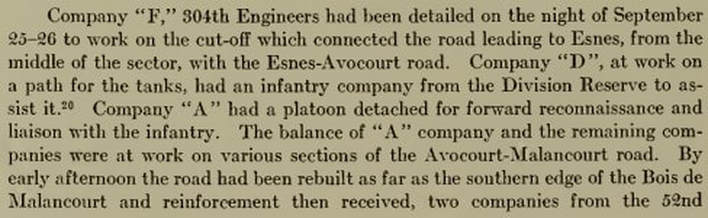

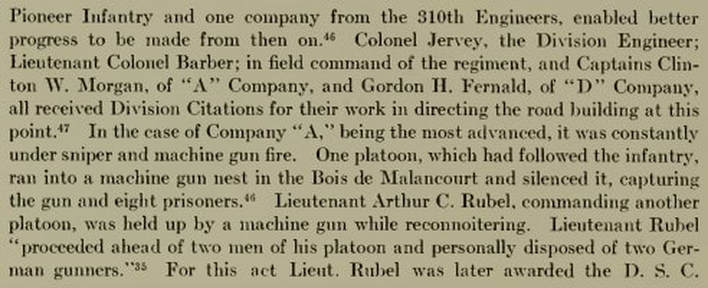

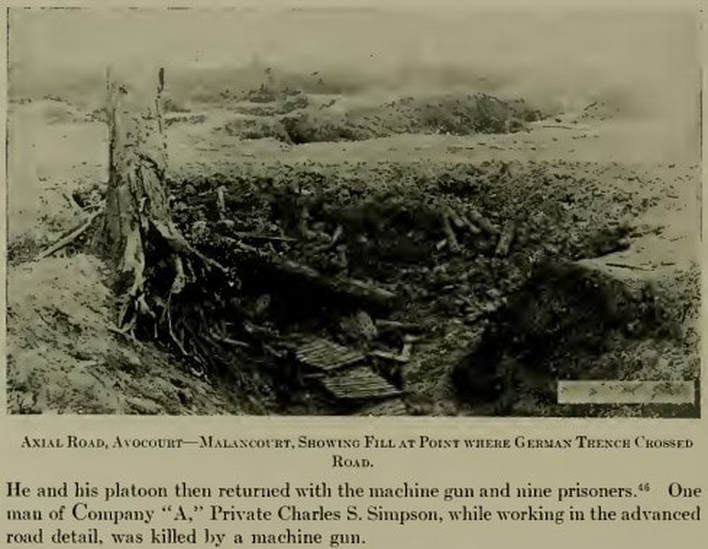

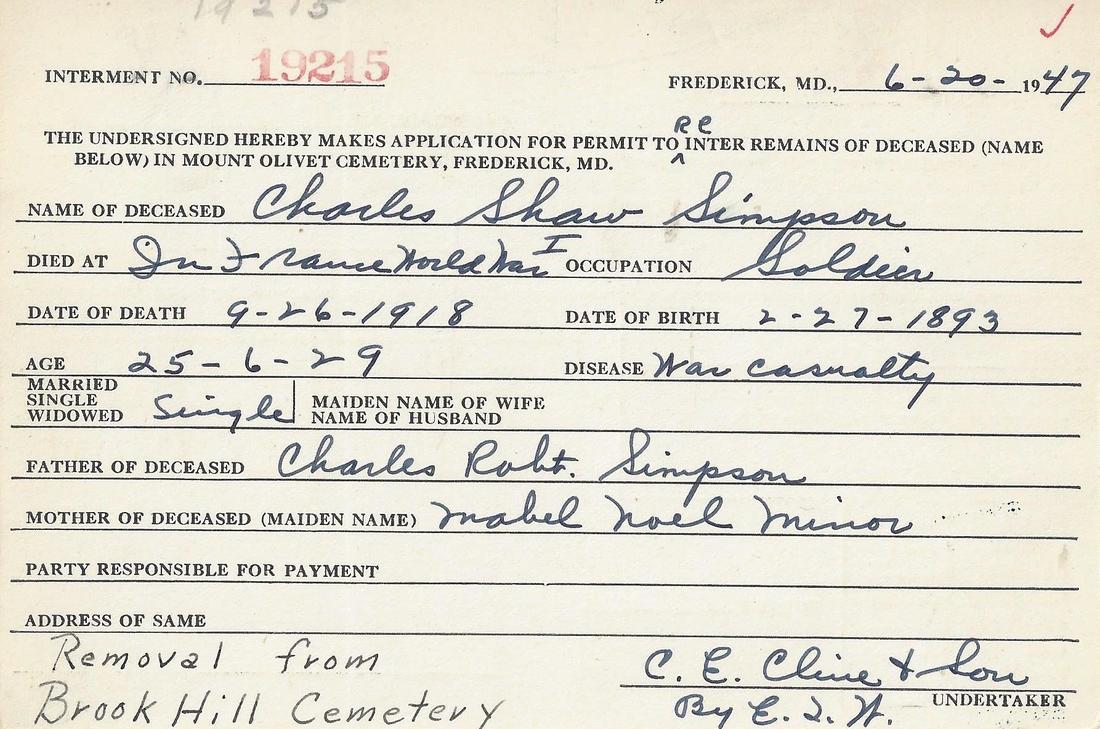

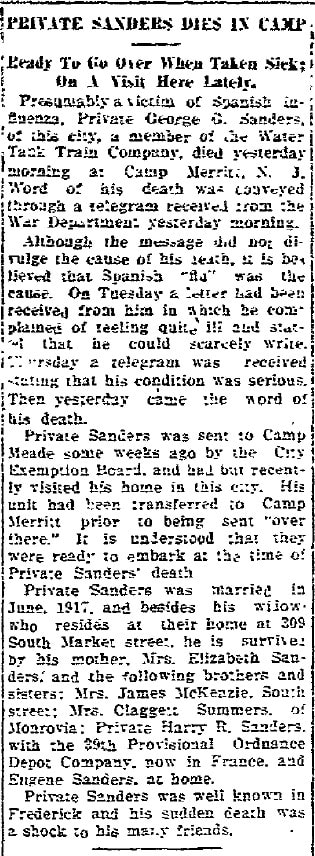

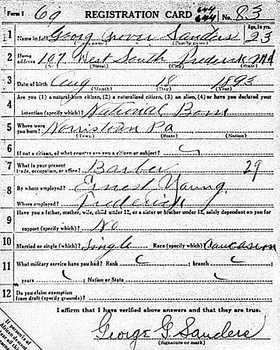

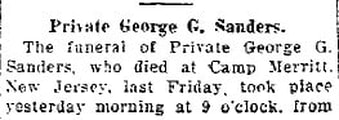

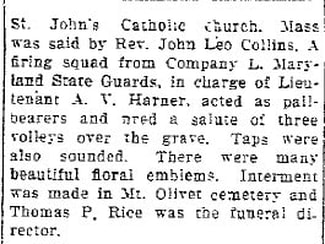

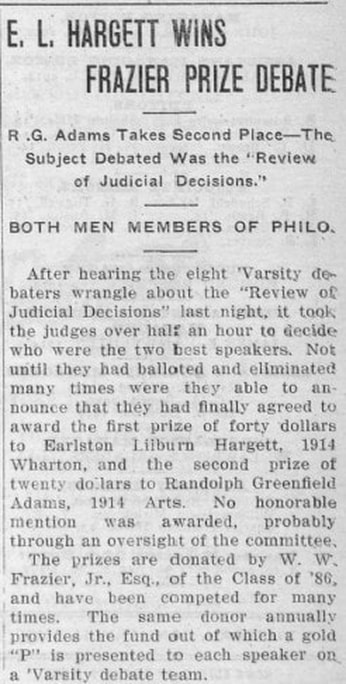

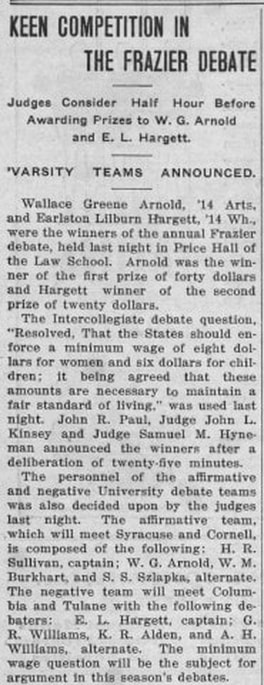

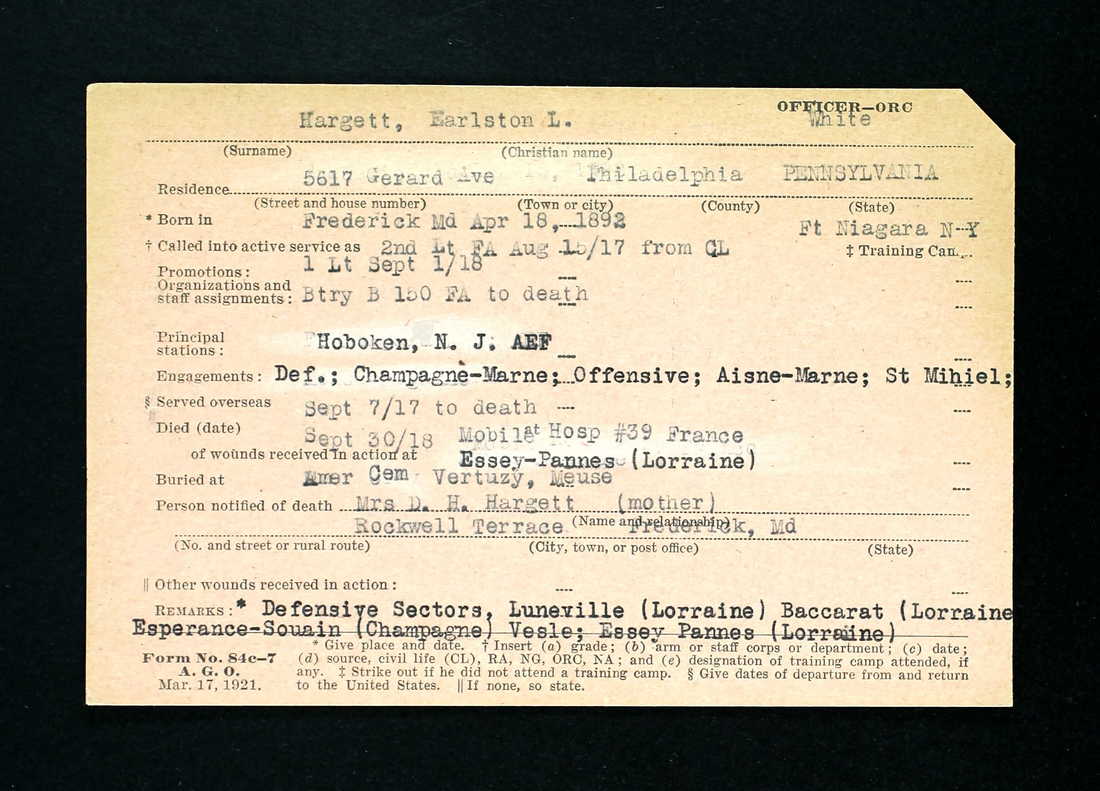

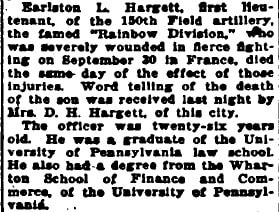

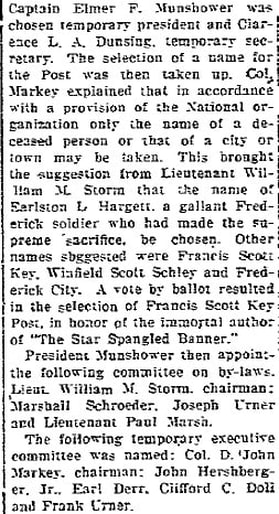

Col. R. H. Tyndall would receive the Distinguished Service Medal during the war and rose to the rank of Major General afterward. Later he would serve as the mayor of Indianapolis from 1942 until his death in 1947. Col. R. H. Tyndall would receive the Distinguished Service Medal during the war and rose to the rank of Major General afterward. Later he would serve as the mayor of Indianapolis from 1942 until his death in 1947. Mrs. D. H. Hargett, 303 Rockwell Terrace Frederick, Md. My Dear Mrs. Hargett: Allow me at this time to express my deep and most sincere sympathy for the great loss you have suffered in the death of your son, 1st Lieutenant Earlston L. Hargett. Being wounded by an enemy shell while performing his duties with his Battery, on September 30, 1918, he died later in the hospital, giving all that a man can give in this great cause. He was admired and respected by all his officers and comrades, and his Battery realizes the great loss of such a man, not only to our organization, but to his Country. You, as his mother, have made the greatest sacrifice that a mother can make, and no doubt you feel great pride in knowing that your son died while fighting civilization’s common enemy. I personally was talking to Lieutenant Hargett a few hours before his death. He was unusually spry and very much interested in the particular work he was doing at the time. I can assure that it was quite a shock to me to learn of his death. His grave will be marked with a cross and the emblem of the Rainbow Division, where it will stand as a monument that will inspire future generations with the willingness of the sacrifice made by this young man. Sincerely yours, Robert H. Tyndall Colonel USA 150th Field Artillery, Commanding  Over 2017-2018, I have placed a great deal of time into researching and writing about military veterans of World War I. There are 500 of these individuals resting here within Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. Earlston L. Hargett is one of these. Others such as John Reading Schley, Charlotte Berry Winters, Harry Burke, Jacob Holdcraft and Miriam Apple have been fodder for other “Stories in Stone” articles, while the entire group of 500 comprises much of the current content of Mount Olivet’s secondary website: www.mountolivetvets.com. One of the biggest historical events of this year (2018) will be the 100th anniversary of the end of that First World War. The November 1918 armistice, which took effect on ‘the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month,’ ended the four-year conflict and marked a victory for the Allied Expeditionary Forces. Will people take notice on the national, state or local level?  April 2016 April 2016 "Leroy Pence," None the Richer At the front half of our current decade, we had the opportunity to commemorate the bicentennial of the War of 1812, and the sesquicentennial (150th) of the American Civil War. At best, there was lukewarm interest shown, but these anniversaries failed to garner overwhelming appeal. I should know, not only because I’m a bonafide “history geek,” but more so because I had a hand in the design and management of several related, commemorative events in my former capacity with Visit Frederick/The Tourism Council of Frederick County. I dragged my sons to several activities, and for the most part, I think they learned some important lessons. One of the best was on July 9th, 2014 right here at Mount Olivet. My 8-year-old son, Eddie, and I spent the day traipsing across the farms comprising Monocacy Battlefield, part of incredible, “real-time” historical walks led by NPS rangers. Just prior to the last one tour in the vicinity of the Thomas Farm, children were instructed to make their way to NPS staff carrying backpacks. Each kid was to reach in the pack and take a small envelope for him or herself, but asked to refrain from opening this casing until after the tour. Each envelope had the name of a participating soldier in “the Battle that Saved Washington.” This was written on the outside, along with info ranging from age, hometown, marital status/children, and military rank and company. A card within the envelope would give the soldier’s fate after the battle. Eddie drew Confederate soldier Leroy Pence, a corporal in the 60th Georgia Infantry Regiment. He was 40-years-old and hailed from Gilmer County, Georgia (about 40 miles north of Atlanta). Pence had a wife named Ann, and nine children. After the tour, we got in my car and proceeded to drive to Mount Olivet Cemetery for a solemn roll call of Monocacy soldiers who were laid to rest in the “garden cemetery” in the days, weeks, months and years following the July 9th, 1864 battle. Along the way, Eddie asked if he could open up the envelope which he had received from the ranger. I obliged and with trepidation, Eddie carefully opened the small packet, and read the contents—"Leroy Pence was wounded in the Battle of Monocacy and captured the next day, July 10th. Sadly, he died of his wounds on September 12th and was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery." Well, we soon arrived at the cemetery, and made our way to Confederate Row, the staging area for the evening program. I exchanged pleasantries with some of the rangers and other friends and acquaintances gathered. Meanwhile, Eddie ventured off a few yards to look at headstones in Confederate Row. Within a few brief minutes, Eddie called from about 30 yards away, “Dad, come here, I found Leroy!” I made my way to the specific gravesite, with two rangers and an NPS photographer in tow. When asked what this was all about, I explained to the others that Eddie had drawn an envelope at the battlefield with Leroy Pence’s name. As Eddie reverently gloated over his find, the rest of us history professionals stood in amazement—the envelope lesson exercise had worked. History came alive (so to speak) for Eddie that day. He also understands that past wars were not glamorous, but rather terrible events where the ultimate sacrifice was made by participants. And therein lies the most important part. From that day on, Eddie will forever remember Corporal Pence, as will his father, as I drive by the fallen soldier's grave each and every work day. Eddie usually stops at the grave every chance he gets. A few years back, he had opportunity to place a flower during a Confederate Decoration Day ceremony. Uncertain Septembers History die-hards, like myself, do make time for heritage commemorations. It’s pretty amazing to wonder how people of the past reacted to the events going on around them. We can appreciate, empathize and ponder their apprehension of what would come next in times of intense chaos and change. I look at Frederick and so many uncertain Septembers from our past, such as: *September, 1745 and the founding of Frederick Town by Daniel Dulany. People could have thought to themselves, "Was this little village on the western frontier going to make it?" S*eptember, 1781 and the beginning of the Battle of Yorktown against the British. Gen. Lafayette arrives in the nick of time to help George Washington and the Continental Army defeat Lord Cornwallis. *September, 1814 had attorney Francis Scott Key wondering if he was really seeing the US flag still flying high atop Fort McHenry during the War of 1812—a rematch against Britain for American Independence. Had the ragtag Defenders of Baltimore saved the city, and country? Or will we go back to drinking tea in the afternoon, and paying high prices to import the stuff? *September, 1862 and Gen. Robert E. Lee had brought his Army of Northern Virginia for the first time to a substantial Union/Northern town. You guessed it—Frederick, Maryland, home of several flag-waving Union heroines no less. In the weeks to follow, major conflicts would be fought nearby on South Mountain and Antietam. The introductory letter(at the beginning of this article) sent to Mrs. Emma Hargett typifies the mood of Frederick 100 years ago. However, it’s hard to emphasize the true desperation of times past, with today's lens within today’s society. As for World War I, we today we live in a global society. “Over There” is not the same big deal as it was in 1918. World War I, and the Planet Earth, in the late teens just isn’t as romantic or exciting as the World War II era. The same can be said for the star personalities: WWI’s Gen. Pershing, Kaiser Wilhelm, President Woodrow Wilson vs. WWII's Gens. Eisenhower & Patton, Adolph Hitler, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, etc.). World War I gets overshadowed by World War II because it’s not as marketable. That’s what drives attention these days. If not, we as a society these days are simply numb to this stuff. It’s hard to believe that we can’t empathize with folks living a century ago. At least, we Americans as a whole, showed compassion 17 years ago in September, 2001 during and after the catastrophic events of the 11th day of that fateful month. Now that was a downright, scary September. Sorry to go off on an opinion-laden rant. It' just that one of my all-time favorite quotes comes from author Victor Hugo (1802-1875). He said: “What is history? An echo of the past in the future; a reflex from the future on the past.” This is the essence of what I am trying to do with this blog, and more so, this incredible cemetery and all those memorialized within it. Numbers, numbers, numbers: Frederick and the Reality of War in September, 1918 Speaking of Hugo, conflict, France, and all things “Les Miserables,” let’s get back to World War I. The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I was about 40 million: estimates range from 15 to 19 million deaths and about 23 million wounded military personnel, ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history. The total number of deaths includes from 9 to 11 million military personnel. The civilian death toll was about 8 million, including about 6 million due to war-related famine and disease. The Triple Entente (also known as the Allies—short for Allied Expeditionary Forces) lost about 6 million military personnel while the Central Powers (the bad guys in our minds) lost about 4 million. At least 2 million died from diseases and 6 million went missing, presumed dead. About two-thirds of military deaths in World War I were in battle, unlike the conflicts that took place in the 19th century when the majority of deaths were due to disease. Nevertheless, disease, including the 1918 flu pandemic and deaths while soldiers were held as prisoners of war, still caused about one third of total military deaths for all belligerents. How did the US fare? Well in a country boasting 92 million people at the time, combat deaths and those missing in action totaled 53,402. Total military deaths from all causes came in at 116,708. Even though the war was fought “Over There” on the European continent, the killing effects of war reached our civilians in the form of a deadly flu epidemic known more commonly as the Spanish Influenza. Frederick City and County were not spared in either case (military members and non-combatant civilians). Mount Olivet Cemetery sadly bears witness to several interments of both camps. The Frederick newspaper included a countywide roll of honor on Page 5 of each edition during the war period. Daily tallies showed casualties in varying scenarios ranging from killed in action to accidental deaths and those from disease. All in all, Frederick County lost 87 military personnel out of nearly 2000 that served, and197 civilians due to the flu that ravaged our area in fall of 1918. Here in Mount Olivet we have 13 gravesites representing known war related casualties, an unlucky number any way you look at it. One of these however is simply a memorial but more on that in a minute. We also have several interments thanks to the Spanish Flu, but more on that with a story I’m working on for next month. An Important Midpoint Since we are making some comparisons to Septembers of the past, I can tell you that 38 of our tally of 500 veterans in Mount Olivet passed in the month of September. Four, out of that number of 13, actually died in September of 1918. I know this because I have been creating memorial pages for each of these soldiers to display on our www.mountolivetvets.com website. I chose to enter these into the site by death date/week. While preparing my entries for late September, I knew I was entering into the period of service related deaths over the last week of September 1918. This also marked the midpoint of the famed 100 Day Offensive. The Hundred Days Offensive (August 8th to November 11th, 1918) was an Allied offensive that ended the World War I. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (August 8-12) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Central Powers back after their gains from the Spring Offensive. The Germans were eventually retreated to the Hindenburg Line, culminating in the Armistice of November 11th, 1918. The term "Hundred Days Offensive" does not refer to a battle or strategy, but rather the rapid series of Allied victories against which the German armies had no reply. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the largest of its kind in United States military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. Under the command of John J. Pershing, this was also the bloodiest operation of World War I for the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). “The Hundred Days Offensive” would also serve as the second-deadliest battle in American history, behind World War II’s Battle of Normandy. American losses were heightened by the inexperience of many of the troops, and tactics used during the early phases of the operation. The battle cost 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives and an unknown number of French lives. Meanwhile, Frederick would lose four local boys over the five-day period of September 26-30th, 1918. September 26th, 1918 —Charles Shaw Simpson Although the news was not known locally until mid-November, 1918, Charles “Carl” Shaw Simpson of my childhood home stomping grounds of Indian Springs (northwest of Frederick) had died on September 26th. Better known by the nickname of "Carl," Private Simpson was a native of Mahoningtown, Pennsylvania, located near Newcastle and northwest of Pittsburgh. Carls’ father, Charles Robert Simpson, purchased the Indian Springs Farm in 1907 and cultivated chestnuts. Carl’s mother, Mabel Noel-Minor, was from southwest Virginia, the daughter of a Confederate captain of the Civil War. Carl Simpson was inducted into the Army on January 10th, 1918. He began as a member of the 154th Depot Brigade's 24th Company. On January 28th, he was transferred to Company A of the 304th Engineers. Private Simpson would board a transport ship bound for France on July 9th. Meanwhile, two of Simpson's siblings were also engaged in the war effort. A telegram appeared in town on November 19th, 1918 announcing that Charles had been killed in action in France almost two months earlier. I conducted some research in an effort to find more specific details about Carl Simpson’s death. As a member of Company A of the 304th Engineers, the 25-year-old private would find himself under the umbrella of the 79th Division on September 26th, 1918. This particular day was also notable as the launch of the First phase of the Meuse-Argonne offensive near the remains of the destroyed village of Avocourt in northeast France. The key objective of this day, and those to follow, was to capture Montfaucon, a steep-sided 500-foot height that was the key to the Giselher Stellung, the first German line of defense. This fortress had to be seized quickly by the 79th Division if V Corps had any hope of taking Romagne and other strong points in the Kreimhilde Stellung, the second defense line. Unfortunately, “green” draftees from Pennsylvania and Maryland became badly confused as the fighting intensified. German machine-gunners, feigning to be dead, suddenly came to life and started shooting up the American rear areas. Men kept charging the machine guns en masse, enabling a single gun to mow down an entire platoon. Front-line elements lost all contact with their artillery. Not until dusk did one battalion of the 79th Division’s 313th Regiment get close enough to Montfaucon to make an attack.  Some of my prior knowledge of this assault came from looking into the death of Frederick resident Harry Burke who was fighting nearby Simpson as a member of Company L, 313th Infantry Regiment comprised of Maryland boys. Carl Simpson and his fellow engineers had the task of creating roads out of a war-torn terrain, and constantly assess the up to the minute volatility of these transportation corridors for other parts of the larger Allied fighting machine. I found a small reference to Private Simpson in a vintage history book about the 79th Division, published in 1922. I have included some book passages that provide context to Simpson’s assignment and subsequent death on that fateful day of September 26th, 1918. Originally buried on the field of battle near where he died, the body of Charles “Carl” Shaw Simpson was brought back home sometime after the war and buried in a family lot in Brook Hill cemetery in Yellow Springs, near the family farm. It appears that Carl’s siblings bought a lot in Mount Olivet (AA/92) in June, 1947. On the 20th of that month, Carl, parents Charles R. and Mable, and Carl’s maternal grandmother Sarah J. Minor were re-interred in Mount Olivet from Brook Hill. September 27th, 1918 —George Grover Sanders, Jr. George Grover Sanders, Jr. was inducted into the Army in late June, 1918. The native of Norristown, PA had been living at 309 S. Market St. with his bride of one year—Marie Frances Severa. He worked as a barber in the shop of owner Ernest Young. Private Sanders would become part of Company B of the 301st Water Tank Train Company. Sanders had originally been serving at Camp Meade and was said to have made a brief visit home to Frederick around this time. Meanwhile, Sanders’ camp had been transferred to Camp Merritt (New Jersey) prior to being disembarked over the prime summer months. A telegram from the US War Department would alert Sanders’ wife and family of the soldier’s sudden demise. He was thought to have contracted the Spanish Influenza. George G. Sanders would die on September 27th, 1917. Three days later, Sanders would be buried in Area T/Lot 126. He left behind a young widow, aged 23. A native of Czechoslovakia, Marie Sanders would remarry in 1922 and would continue to reside at 309 S. Market St. She wed another local WWI vet in Charles Smith Hobbs, Jr. of New Market. Hobbs was a wagoner and served overseas with Company D of the 103rd Ammunition train. He saw plenty of action, including activity at Meuse-Argonne.The couple would have at least one child, Charles Smith Hobbs, Jr. September 29th, 1918 —Harry Burke I previously mentioned Harry Burke in reference to Carl S. Simpson’s death while trying to take Montfaucon. Burke was reported “missing in action” just three days later. Back last February 2018), I wrote a full article on Harry C. Burke. He was born at Pearl, just east of Frederick in the vicinity of what locals know was the old Jug Bridge Seafood Restaurant on MD144, opposite the major development of Spring Ridge. Burke was with Company L of the 313th Infantry Regiment. At this time, the 313th was playing a major part in the principal engagement of the war—the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Harry C. Burke was one of the casualties as he went missing in action on September 29th. The folks at home in Frederick wouldn’t learn this fact until November 11th, 1918—Armistice Day. In the meantime, an earlier written letter by Burke had made it back to town, here. The Frederick native participated in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive’s “First phase,” which took place from September 26th to October 3rd, 1918. The 79th Division was assigned the deepest, first-day objective of any division of the Army even though it was facing some of the most difficult terrain in the Meuse-Argonne region. Private Burke’s body would be recovered in early November. Subsequently, his remains were placed at the US Meuse-Argonne Military Cemetery in Romagne, France. Burke’s father bought a gravesite in Mount Olivet (Area U/Lot 12), and, at least by November of 1923, a wreath and flowers were placed on the young boy’s grave during Memorial Day commemorations. Although Burke’s corpse still remains in France, Mr. Burke erected a large granite block monument in the 1920’s. (http://www.mountolivetcemeteryinc.com/stories-in-stone-blog/finding-private-burke)  September 30th, 1918 —1st Lt. Earlston Lilburn Hargett You were introduced to this young man at the onset. Born April 18, 1892, this was truly a talented and promising individual, cut down before he could leave an even bigger imprint on the world. Here is the contents of an article from the local newspaper regarding his death. The Frederick Daily News, November 2nd, 1918 EARLSTON L. HARGETT, first lieutenant of the 150th Field Artillery, the famed "Rainbow Division," who was severely wounded in fierce fighting on September 30 in France, died the same day from the effect of those injuries. The following telegram was received last night (October 16th, 1918) by his mother, Mrs. D. H. Hargett, Rockwell Terrace: "Deeply regret to inform you that it is officially reported that Lieutenant Earlston L. Hargett, Field Artillery, died September 30 from wounds received in action. Harris, the Adjutant General" Lieutenant Hargett was 26 years of age. Despite his youth he was an LLB, being a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania law school and also a graduate of the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce of the University of Pennsylvania. His early education was received in the public schools of Frederick and at the Boys High School, where he was a graduate. During his course at the University of Pennsylvania he participated in intercollegiate debates, being an orator of exceptional skill. Fought At Chateau Thierry Lieutenant Hargett was commissioned a second lieutenant at the Fort Niagara training school, and was promoted to first lieutenant while in France. He participated in the fighting at Chateau Thierry, coming out of the battle without a scratch. Having served in France for about a year, he wrote a number of interesting and entertaining letters of camp and trench life. His letters were distinguished by keen humor and graphic bits of description. These articles were widely read and were among the most interesting sent home by Yankees in France.

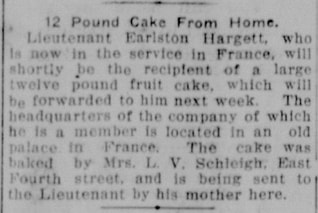

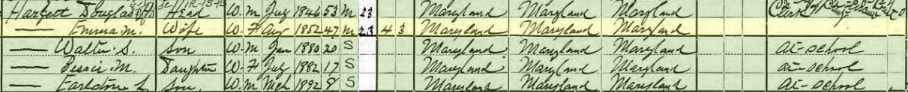

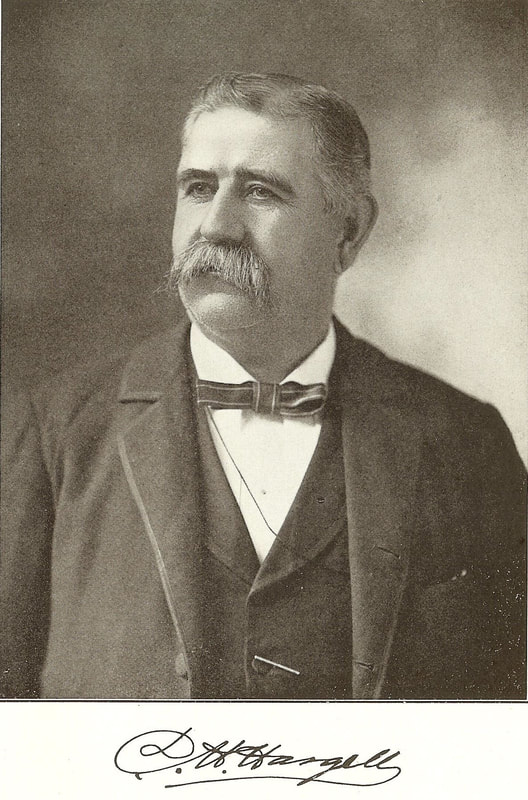

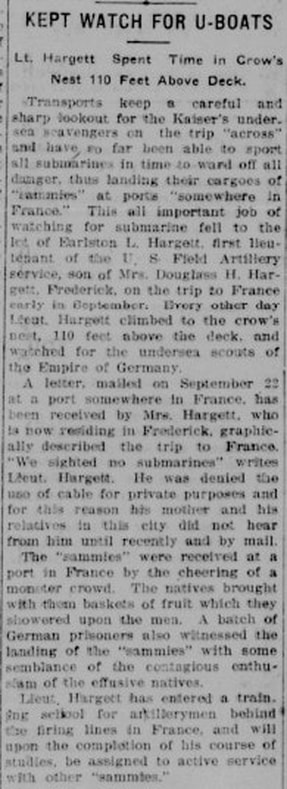

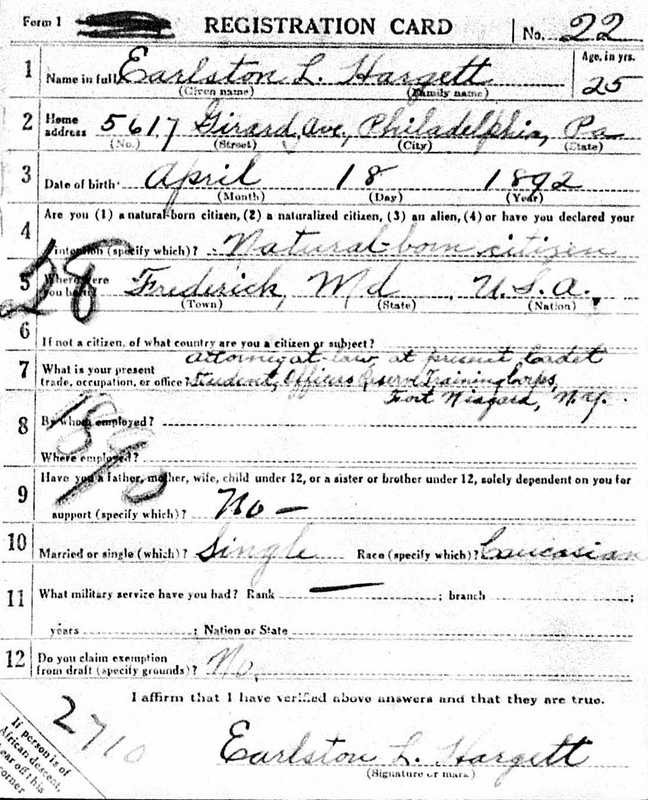

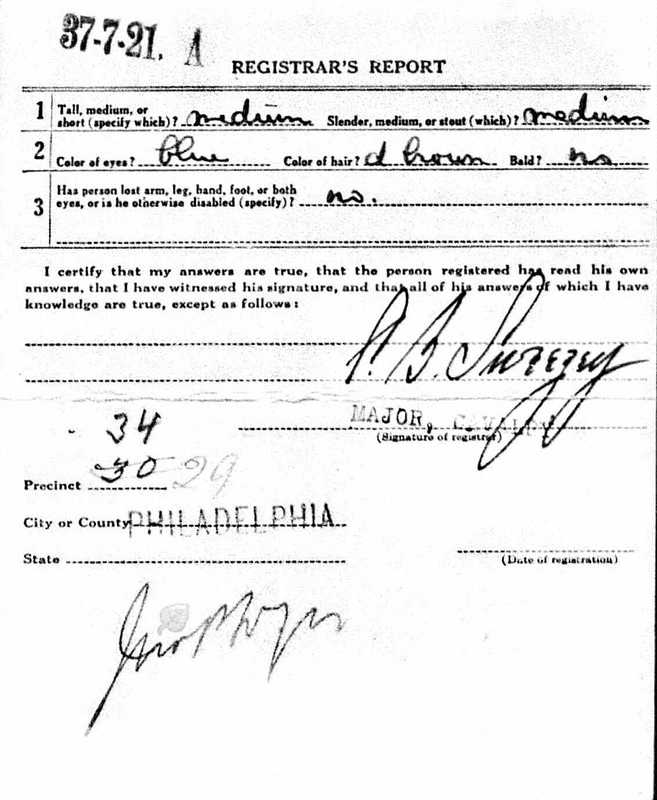

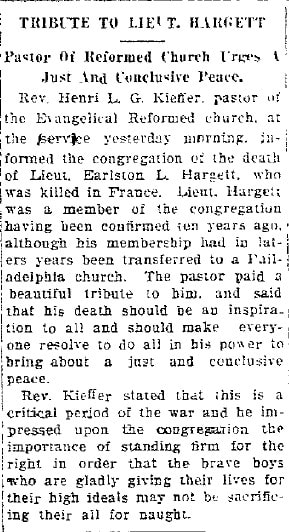

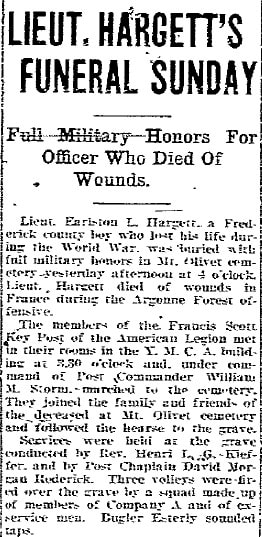

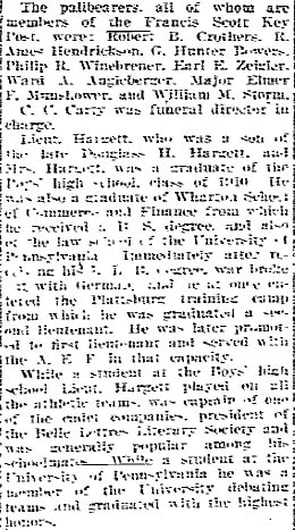

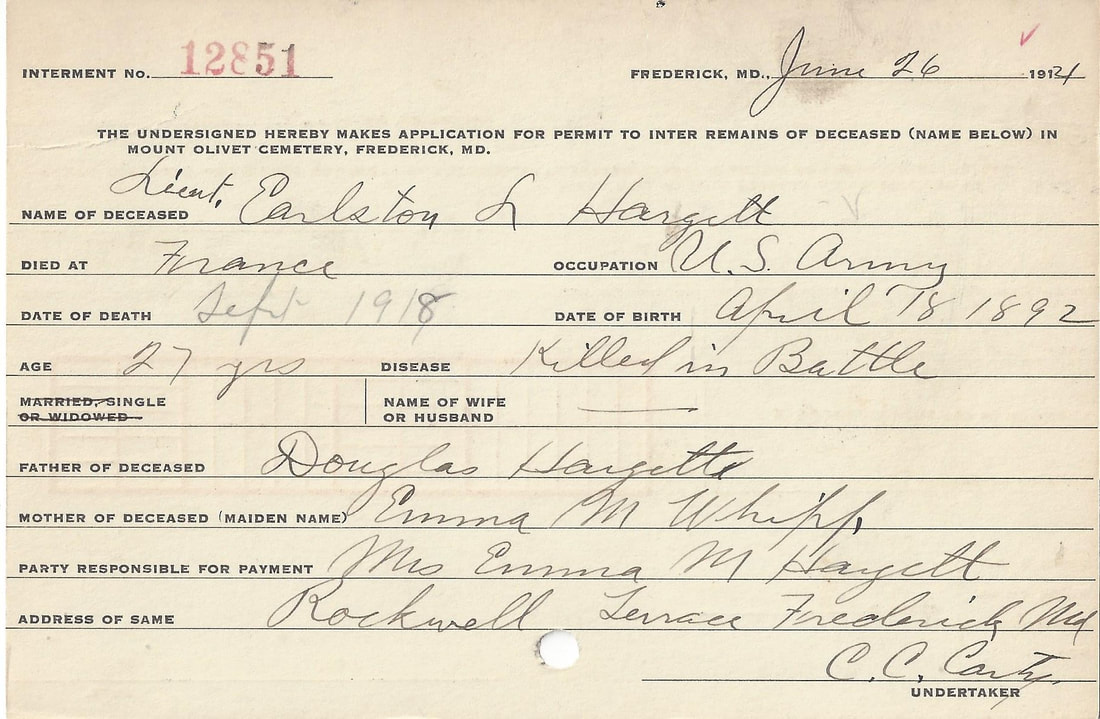

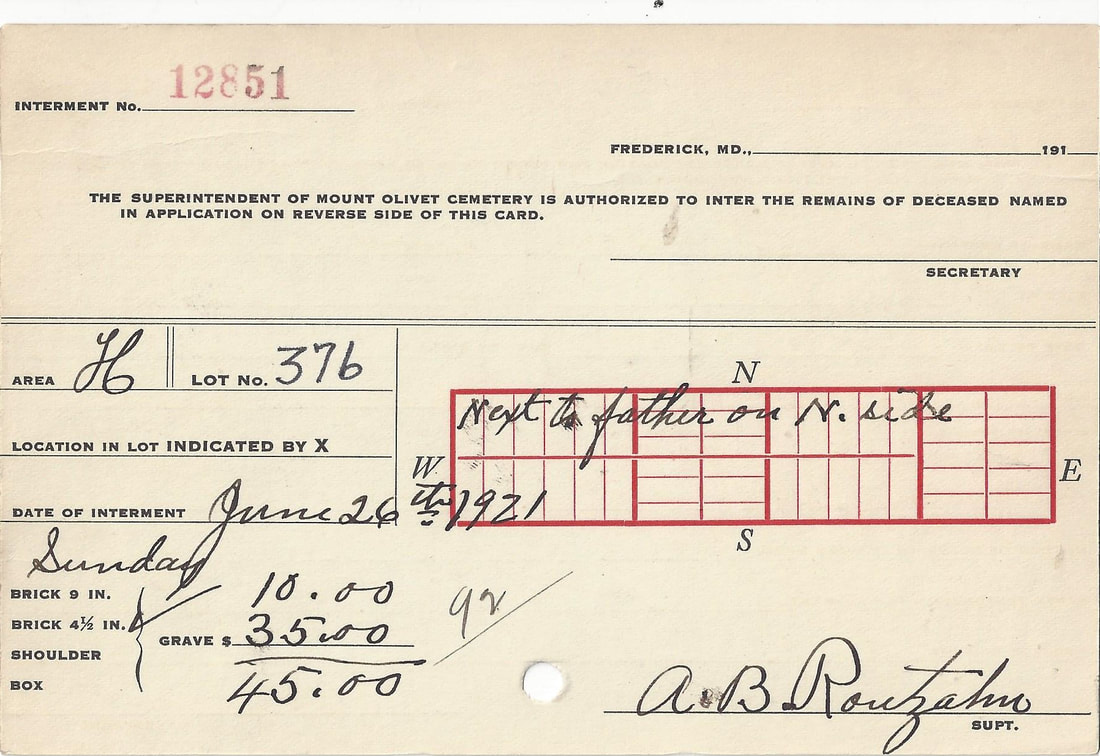

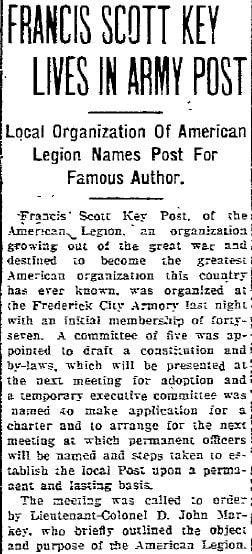

Frederick Post (Oct 27, 1917) Frederick Post (Oct 27, 1917) Before entering the Army, Hargett was living in Philadelphia and working as a attorney. Earlier he had attended Frederick Boys’ School and learned under the likes of Professor Amon Burgee. Hargett was one of the top cadets of his class and graduated in 1910. Sadness had engulfed the family a year prior in 1908 when Earlston’s father, Douglas L. Hargett, a local merchant and clerk of the circuit court died on September 29th, 1908. Mrs Hargett was left with Earlston and a sister named Bessie M. (Clapp). An older brother, Dr. Walter S. Hargett, had already moved out of the house and was living in Philadelphia. The family had endured heartache nearly 20 years earlier when Earlston's older brother, Burns, had died at 12 years of age in a farming accident back. Earlston had two strong uncles looking out for him, P. L. Hargett and Schaeffer T. Hargett, leading farmers and operators of a successful grain and milling business in town. A gifted student, Earlston excelled in grade school, and equally in college at the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with high honors. Earlston’s mother was the former Emma M. Whipp (1852-1931). She adored her youngest child and it can be assumed was worried throughout his wartime absence. I found an article in the newspaper from October, 1927 in which she had a special culinary surprise delivered to him while in Europe. He enlisted on August 15th, 1917, finding himself now a student cadet at Fort Niagara as part of the Officers Training Reserve Corps. Hargett was given the rank of 2ndLt of Field Artillery and shipped out to Europe a month later. Lt. Hargett would be promoted to 1st Lieutenant, a year later, on September 1, 1918. He found himself quite busy staging for the largest, and costliest, military offensive in American history. Just a few days before he went into the battle, in which he received the wounds which caused his death, Lieutenant Hargett wrote home describing his camp quarters. On September 26, just four days before his death, he sent his Christmas label, with a brief note attached. The letters: Piano at Field Camp Letter written Sept. 24: “Time has been skipping by so quickly that I hardly know when I wrote you last but think it has been about a week: a very busy one too for me. After our successful offensive, when we gained all our objectives, took more than 13,000 prisoners, and gained more than 130 square miles of territory, we are now resting and are stabilizing the lines for winter. I am in charge of the “echelon” or combat train. We are occupying a camp in the woods which the Germans constructed. There are barracks for the men, stables for the horses and splendid quarters for the officers. Some o the buildings were burned by the Germans before they left. There are enough remaining to accommodate our battery. We even have a piano which they were compelled to leave behind. I am living in a little building which is very attractively decorated with papered walls and mission work furnishings. Being the senior officer at the echelon, I am entitled to the best piano. I have a big mirror, four feet long, and two and a half feet wide with a gold frame. I have a splendid German stove and in camp there are about twenty cords of fine oak wood which the Germans cut and about fifteen tons of their coal. So we are well fixed for the winter if we are compelled to stay here. They had running water and even electric lights but neither of these are working now. One supply I wish they had not left as plentiful and that is German fleas. They have almost eaten us up since we have been here but I suppose they will quiet down after a while. I have not found any “cooties” recently and that is some consolation for the fleas. Oh, yes, we also have a big kettle which we use for a bath tub so that I will not now have to go eight weeks without a bath, as I did at one point this summer. Tell all the folks that I have not much time to write, but if all goes well, we will have things organized in a week or two and I can write again to everyone.” On September 26, a short letter was received advising what to enclose in the Christmas package and ending by saying: “I just wrote you day before yesterday. As I was up all last night, I am pretty tired now, I will get to bed now and write you again in a few days.” Earlston L. Hargett would not have the opportunity to follow up on his promise to write to his mother again. The distress and uncertainty she must have felt as days turned to weeks without word from her son. A Pennsylvania compensation records shows that Lt. Hargett was fatally wounded at a Essey-Panes (Lorraine) on September 30th. He succumbed of his wounds later that day at Mobile Hospital #39, and was buried at the American Cemetery at Vertuzey, within Aulnois-Sous, Department of Meuse. The newspaper article concluded by saying: "The death of Lieutenant Hargett brings the county’s honor roll up to 65 men, of this number, eight were killed in action; 4 died of wounds; one was killed in an accident; one died at sea; 28 died of disease; 20 were wounded in action and three were missing in action. The honor roll appears on page five of the morning edition." More casualties would be added to the Frederick Honor Roll in the weeks and months to follow. A few final notes on 1st Lt. Hargett. He was originally buried in a military cemetery at Vertuzey, France. In 1921, his body would be brought back home and he would be buried by his father’s side in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 376. This occurred in a formal ceremony on June 26th, 1921. The planning and logistical work was performed by Frederick’s American Legion Post #11, formed in July 1919. As a matter of fact, during the initial planning sessions for that organization, a discussion ensued about naming the Post after a deserving figure in history. Interesting entries were put forth, but most interesting was a strong suggestion by W.L. Storm. He lobbied for Post 11 to become the Earlston Lilburn Hargett Post #11 of the American Legion. The name however went to Francis Scott Key, an equally deserving veteran and patriot from an uncertain September, 100 years earlier. The planning and logistical work was performed by Frederick’s American Legion Post #11, formed in July 1919. As a matter of fact, during the initial planning sessions for that organization, a discussion ensued about naming the Post after a deserving figure in history. Interesting entries were put forth, but most interesting was a strong suggestion by W.L. Storm. He lobbied for Post 11 to become the Earlston Lilburn Hargett Post #11 of the American Legion. The name however went to Francis Scott Key, an equally deserving veteran and patriot from an uncertain September, 100 years earlier. Interested in learning more Frederick History from this author? Check out Chris Haugh's latest, in-person, course offerings including : "Prehistoric Frederick" (starting Monday, October 2nd) and "Indian Tribes, Explorers & Fur Traders in the Monocacy Valley." (begins Monday, November 6th). These will take place at Mount Olivet Cemetery's historic Key Chapel. For more info and course registration, click the yellow link below! More class offerings (and walking tours) to come! http://www.historysharkproductions.com/more-frederick-history-courses.html

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed