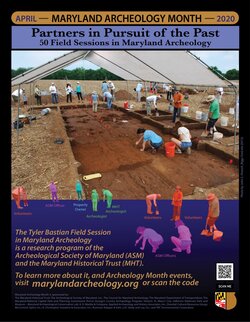

You may not be aware of this, but April is Maryland Archeology Month. This has been the case since 1993 when Archeology Month was officially proclaimed by Governor William Donald Schaefer as “ a celebration of the remarkable archeological discoveries related to at least 12,000 years of human occupation here in “the Old-Line State.” Maryland Archeology Month has annually provided the public with opportunities to become involved and excited about archeology. With a variety of events offered statewide every April, including exhibits, lectures, site tours, and occasions to participate as volunteer archeologists, “Archeology Month elicits the gathering of interested Marylanders at various occasions to share their enthusiasm for scientific archeological discovery.” This according to the Maryland Archeological Trust, the chief sponsor of activities. Well, scheduled Maryland Archeology Month activities for 2020 were postponed because of the Covid-19 pandemic. These include featured lectures across the state, but most importantly the Field Schools, or Sessions, which are open to the general public. This year’s theme was Partners in Pursuit of the Past: 50 Field Sessions in Maryland Archeology. The Field Sessions are 11-day intensive archeological research investigations held every spring in partnership between the Archeological Society of Maryland, a State-wide organization of lay and professional archeologists, and the fore-mentioned Maryland Historical Trust, a part of the Maryland Department of Planning and home to the State’s Office of Archeology. While these two partners host the event every year, others are required to make the Field Sessions happen, including researchers/principal Investigators, archeological supervisory staff, property owners, and volunteers from the public.

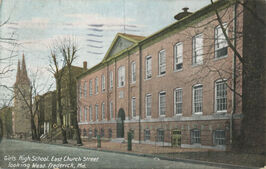

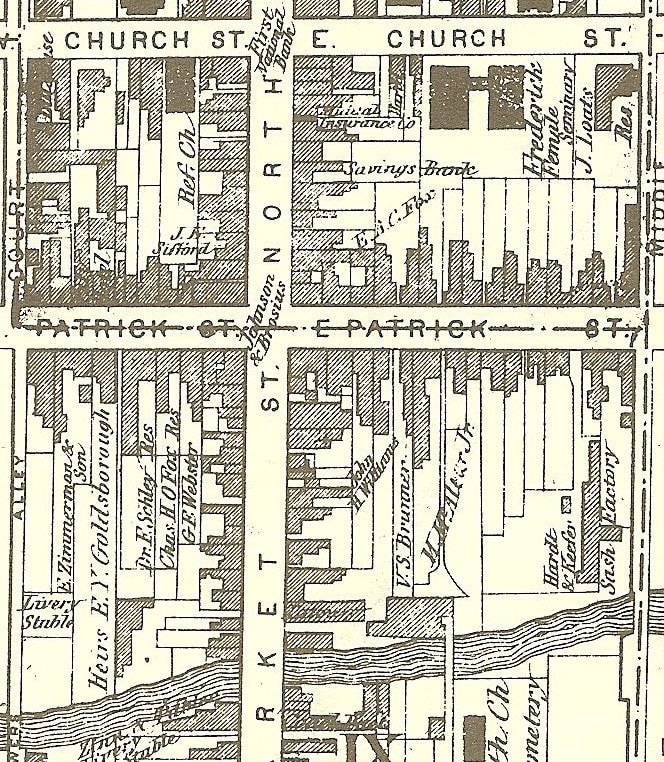

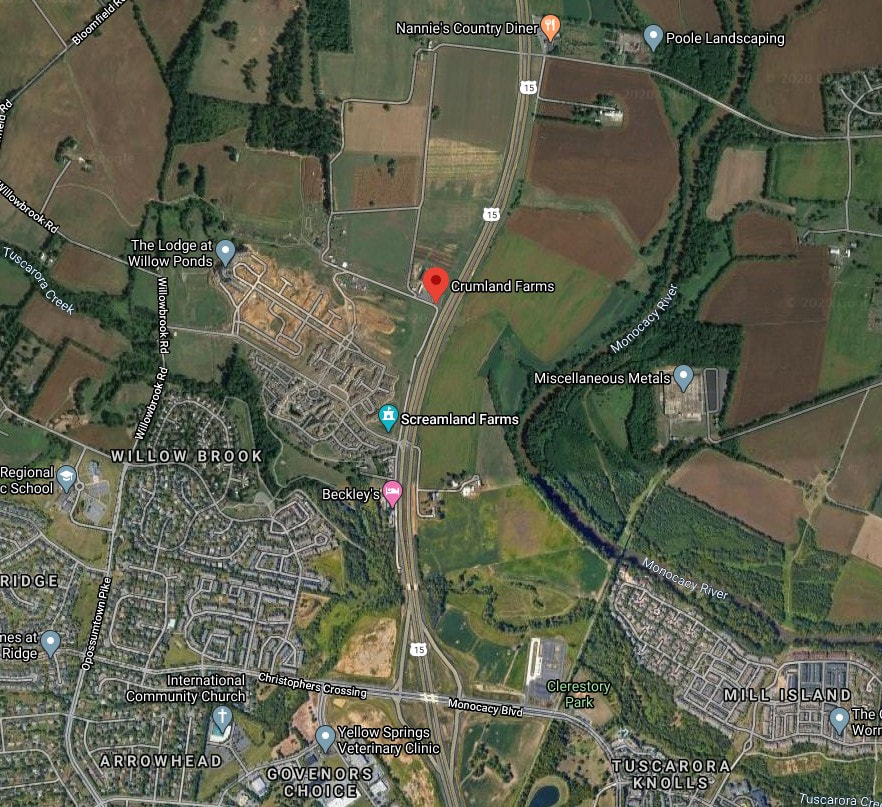

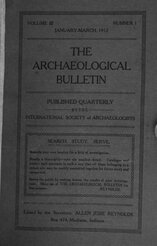

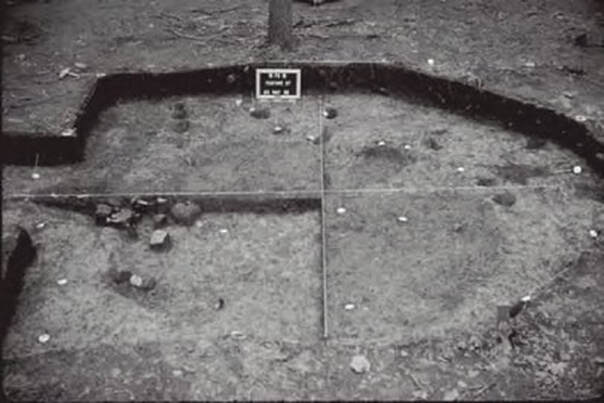

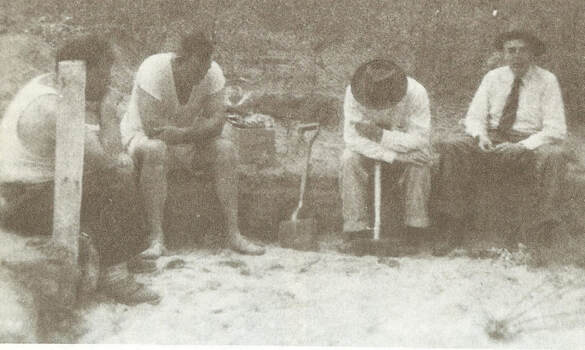

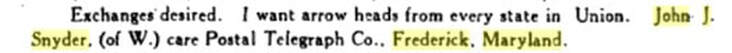

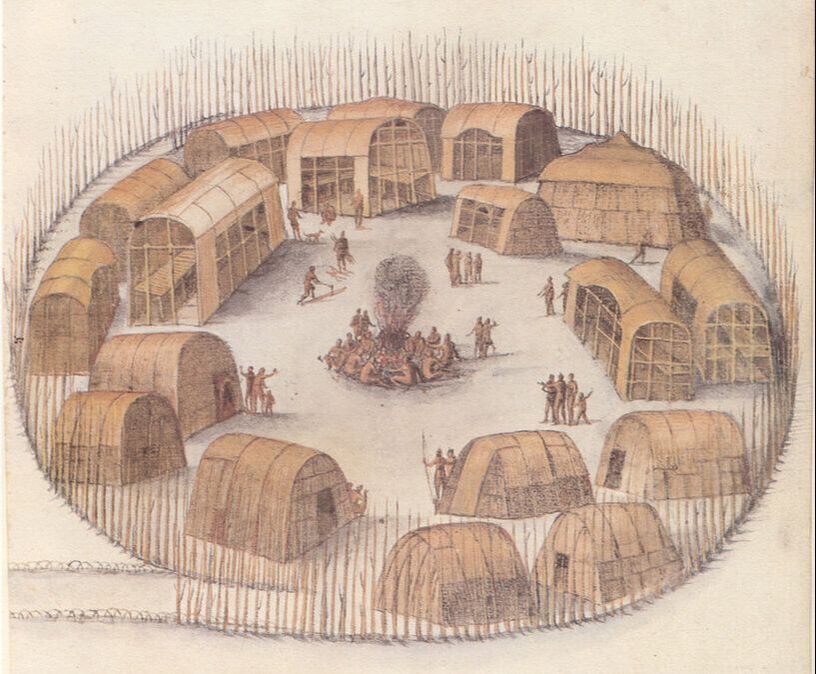

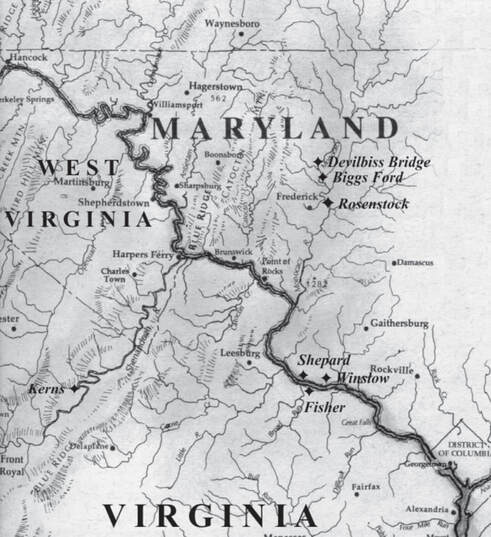

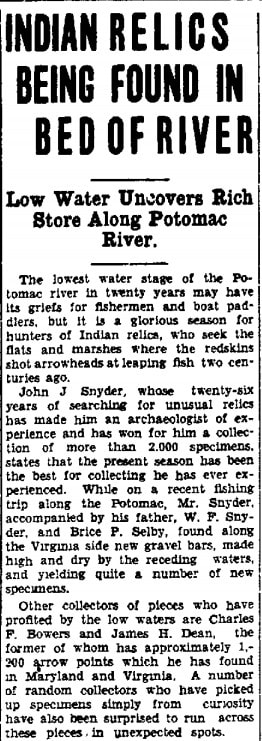

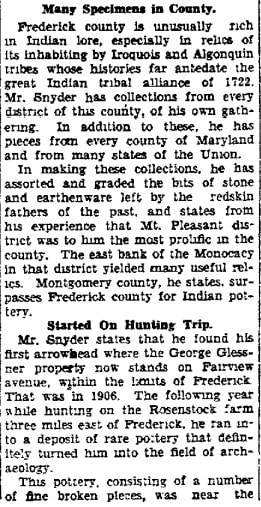

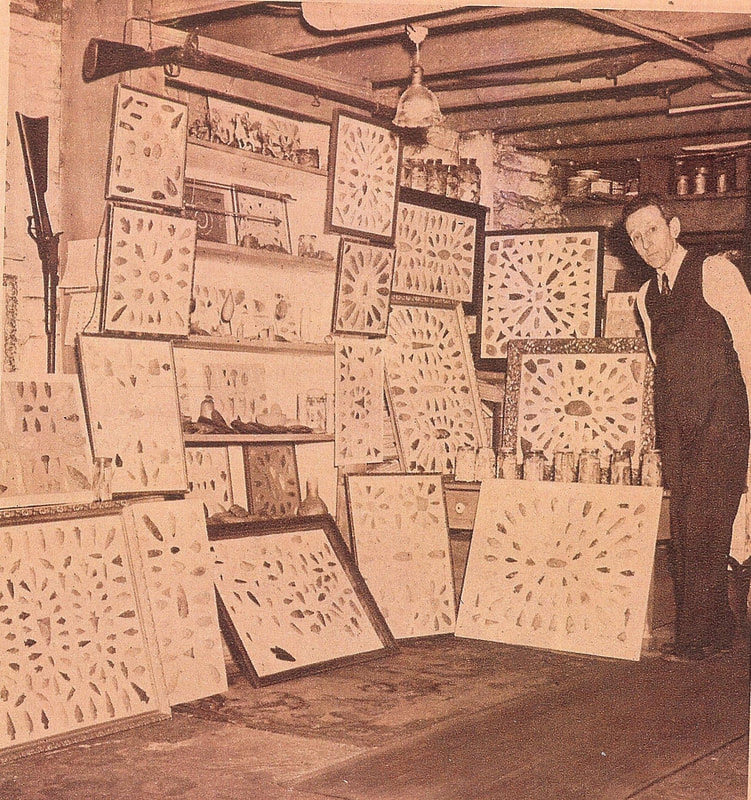

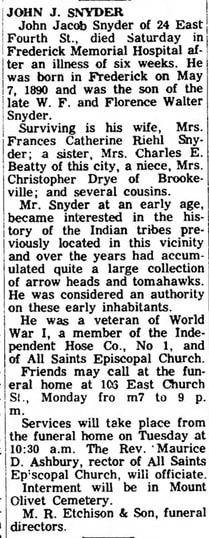

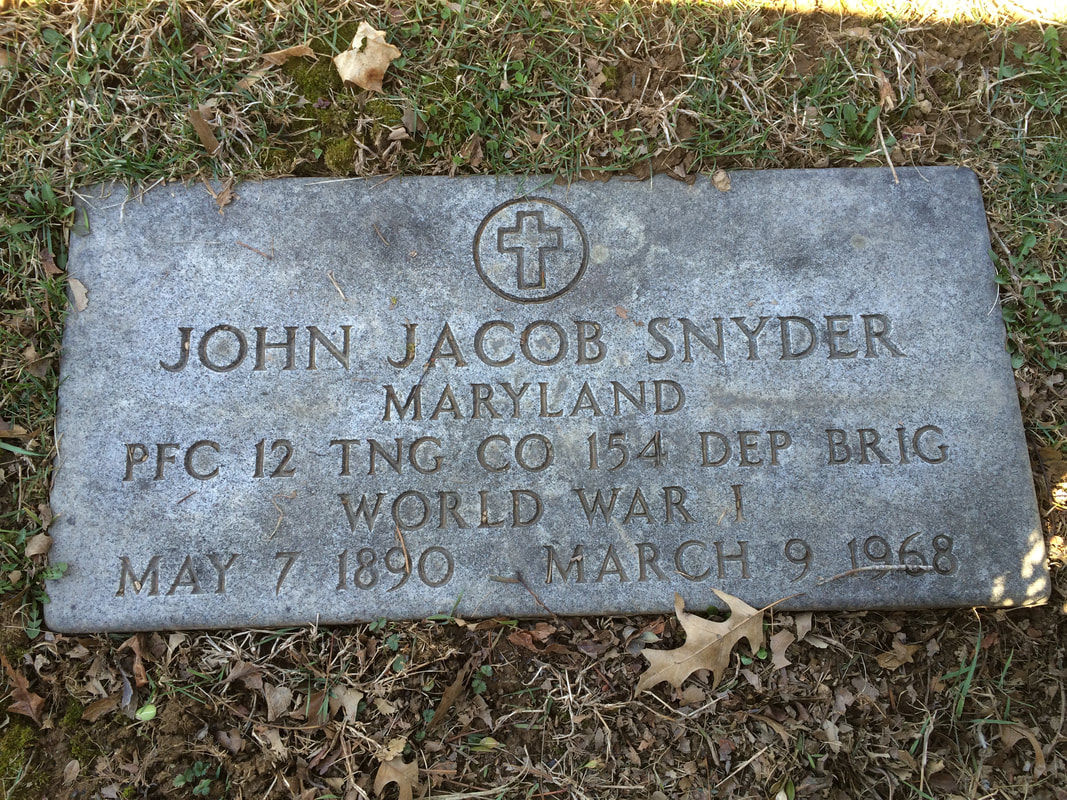

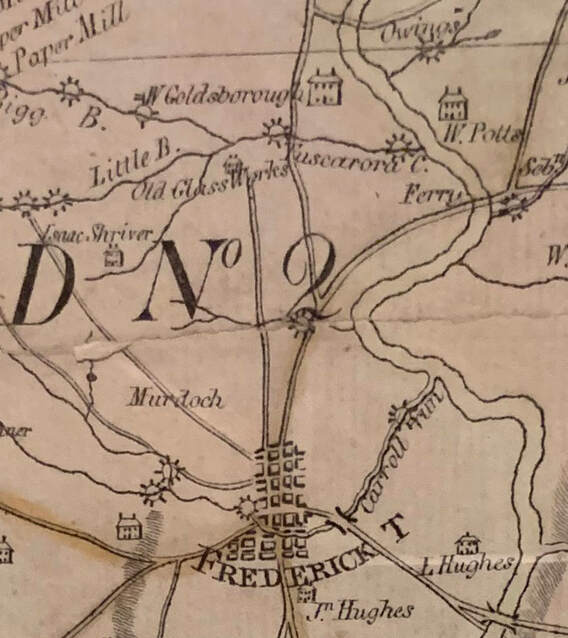

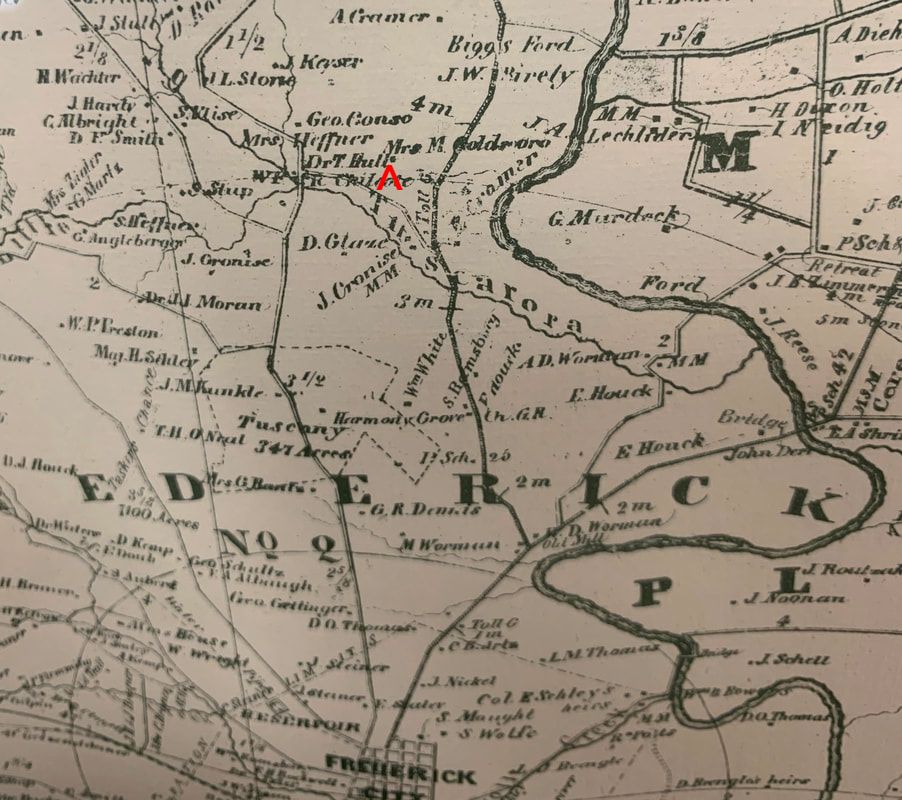

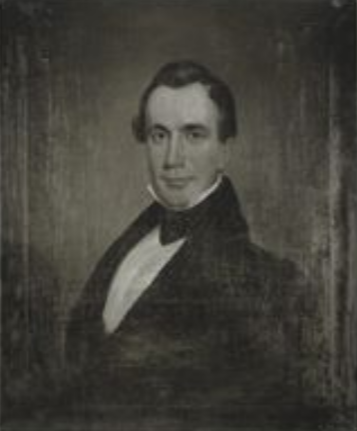

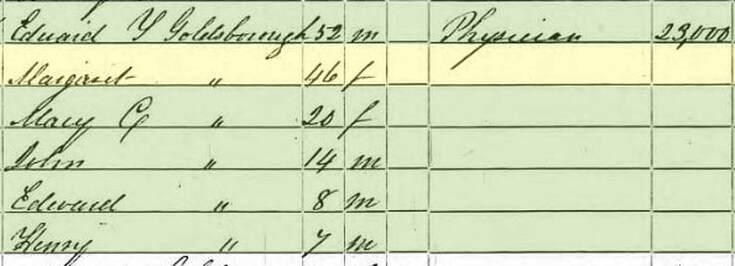

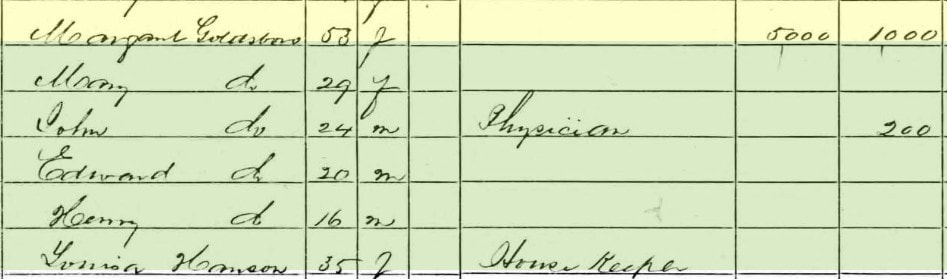

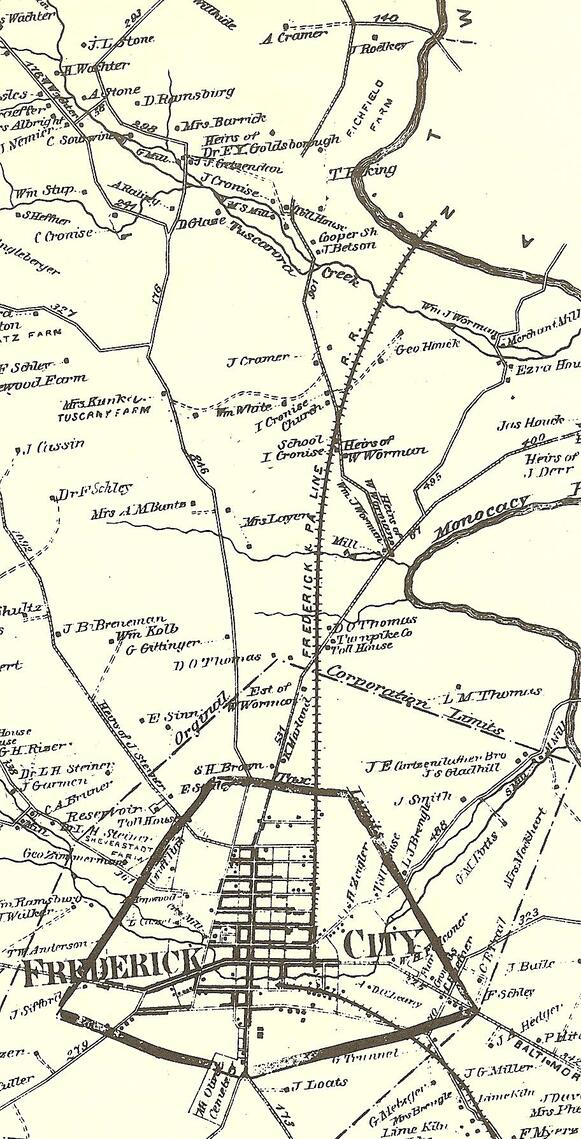

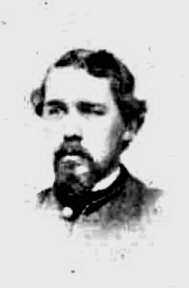

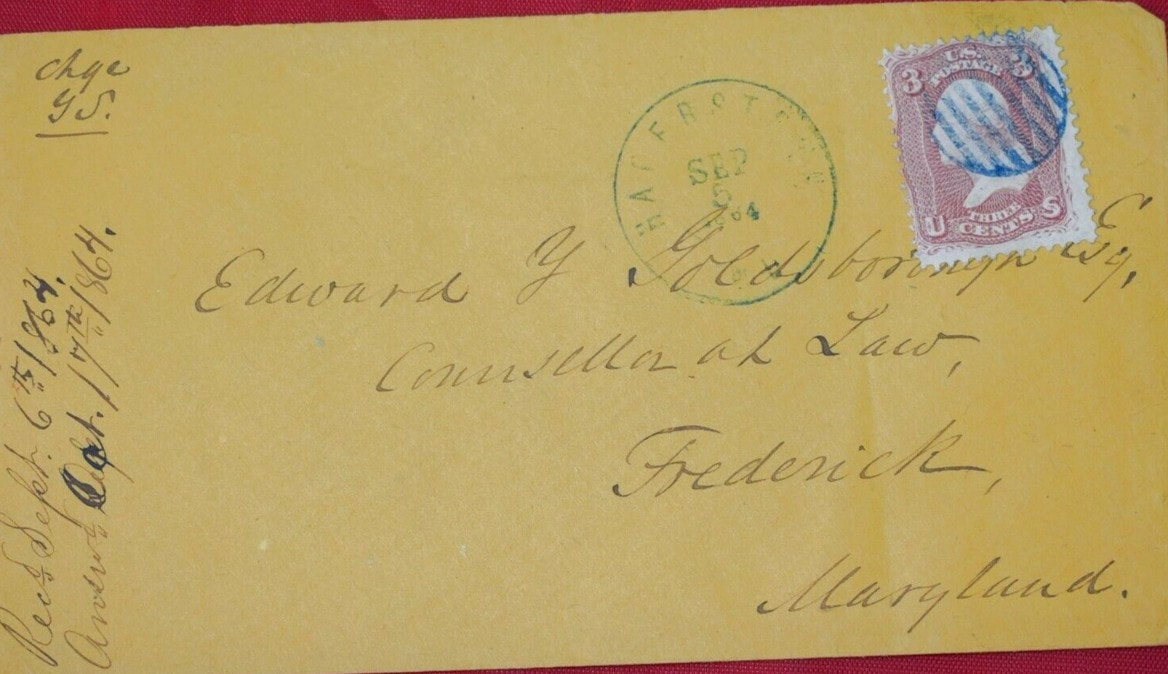

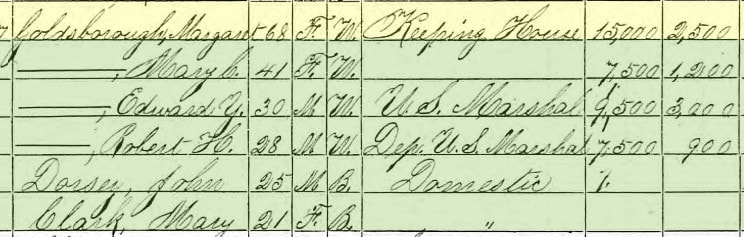

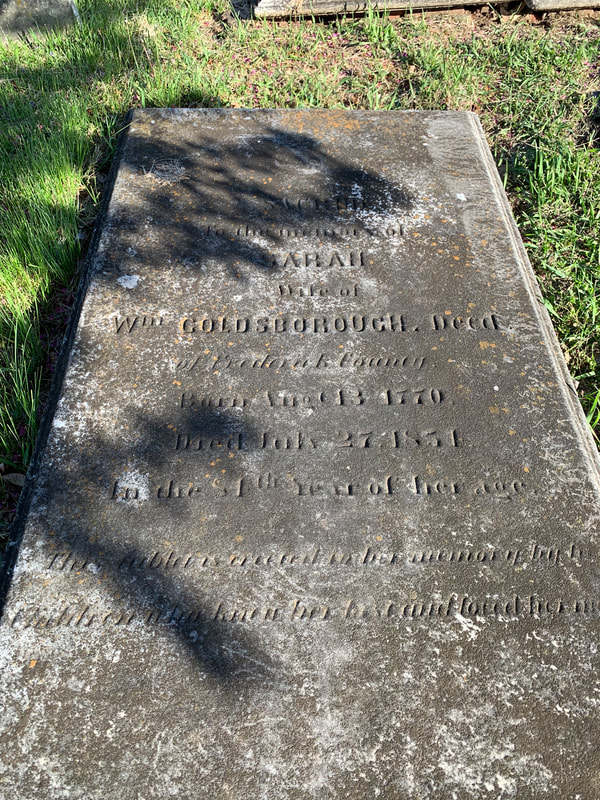

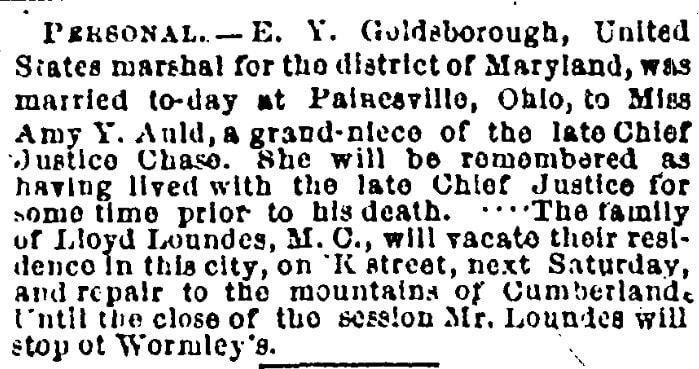

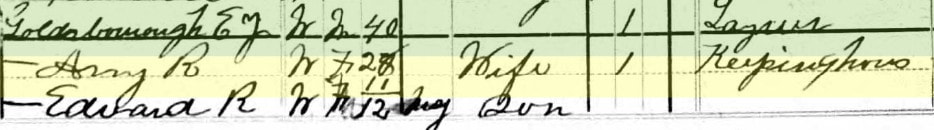

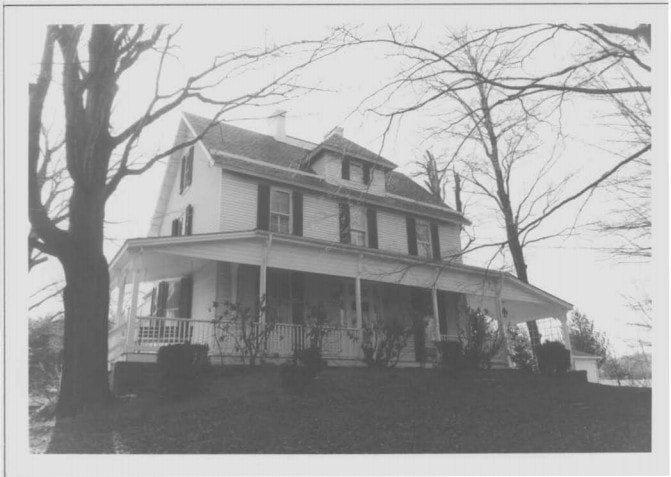

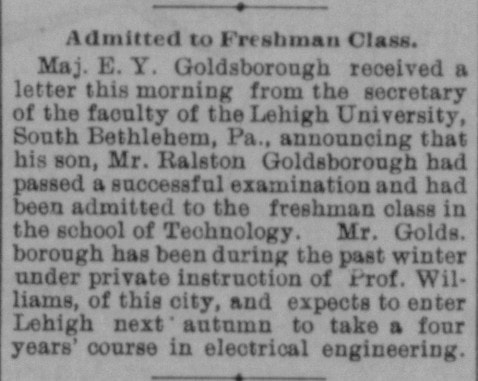

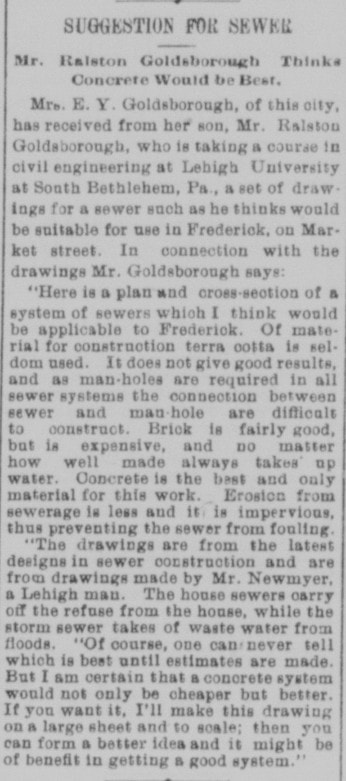

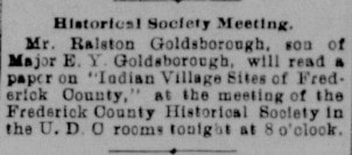

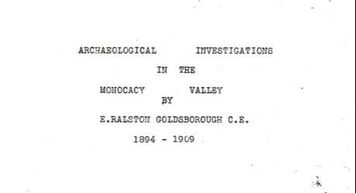

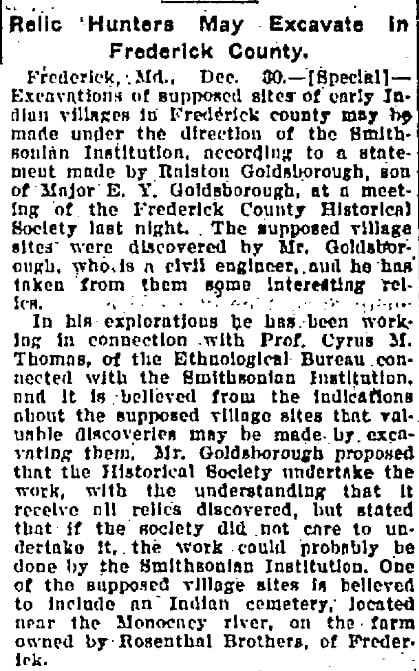

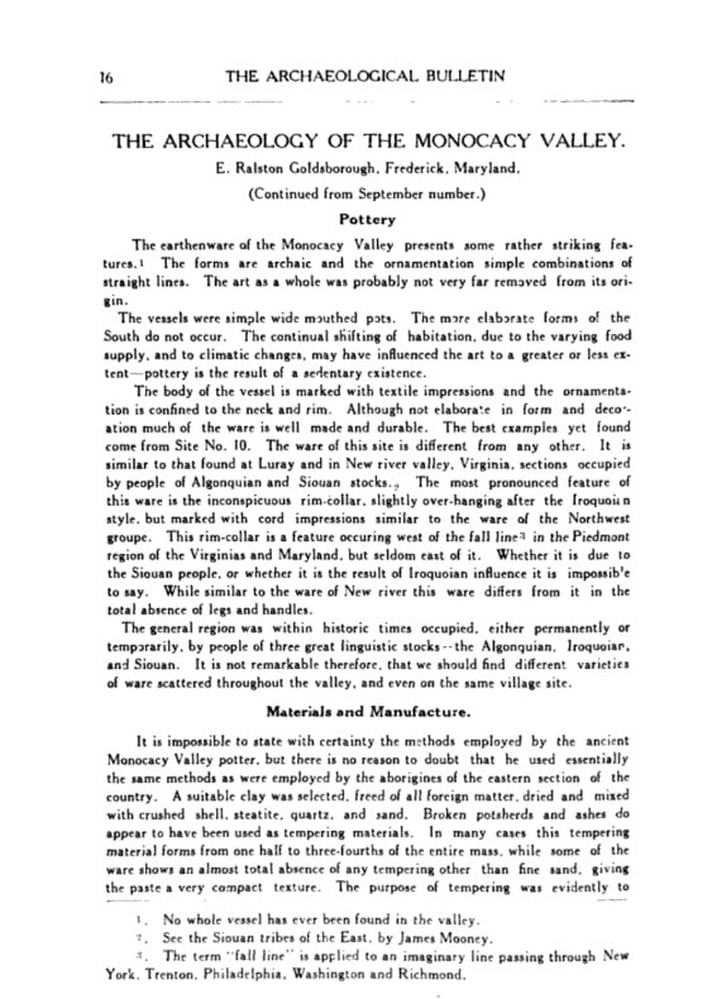

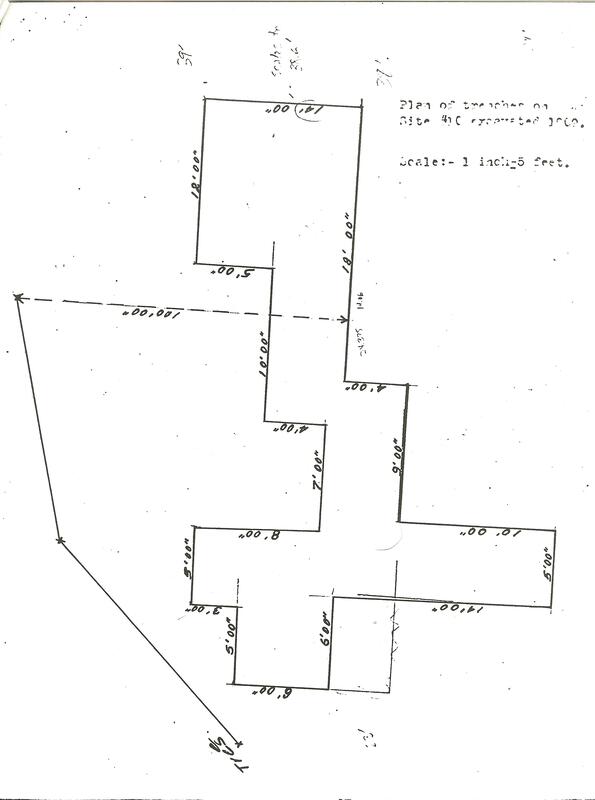

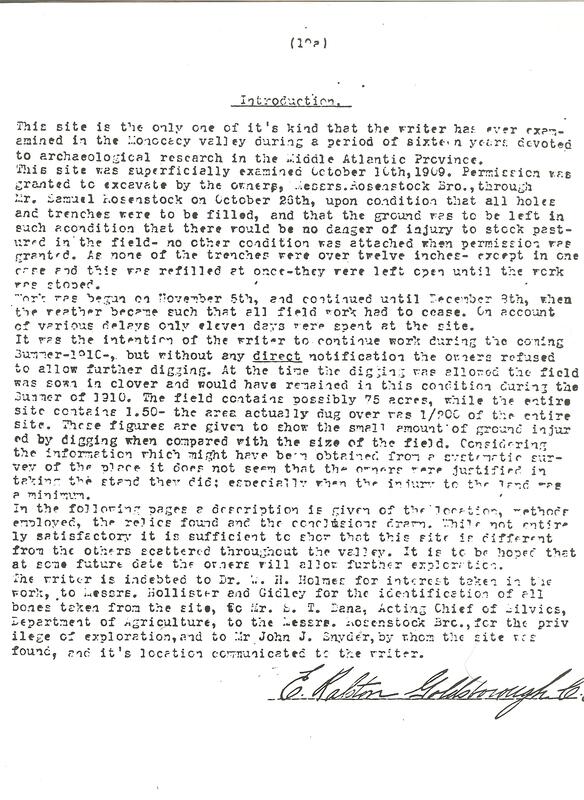

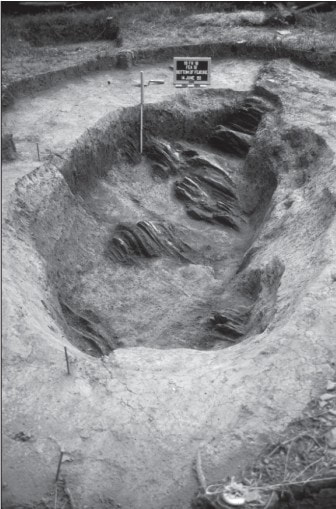

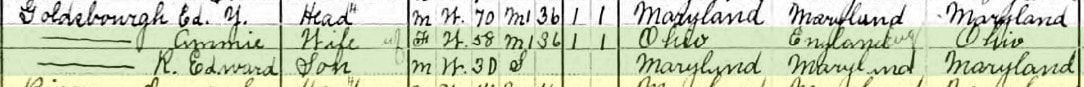

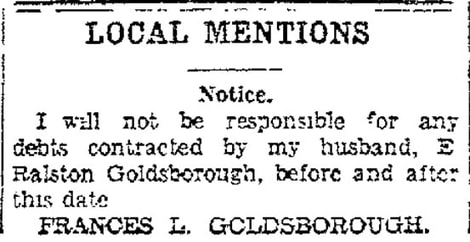

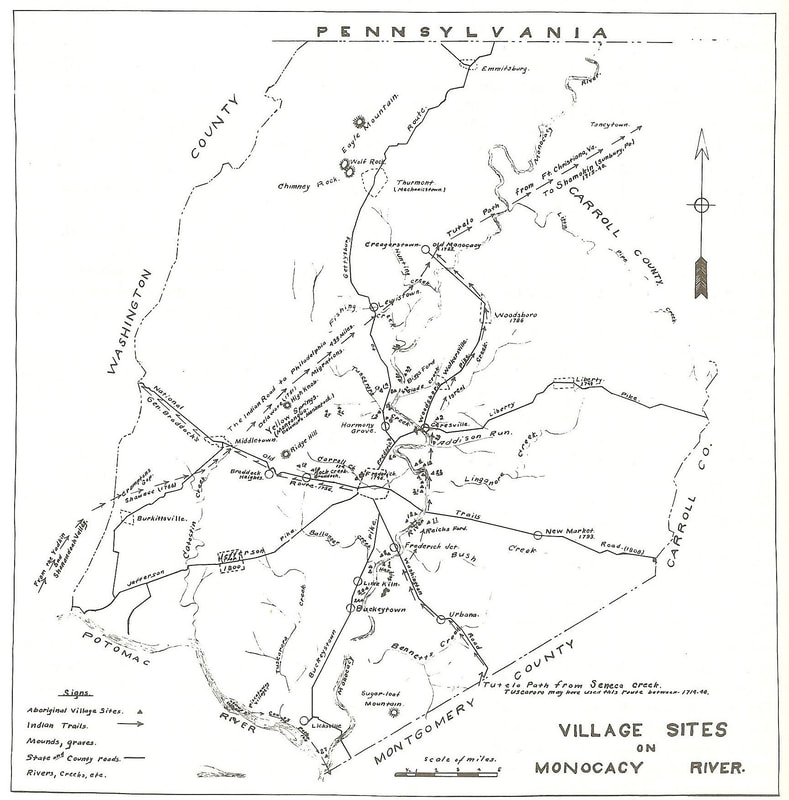

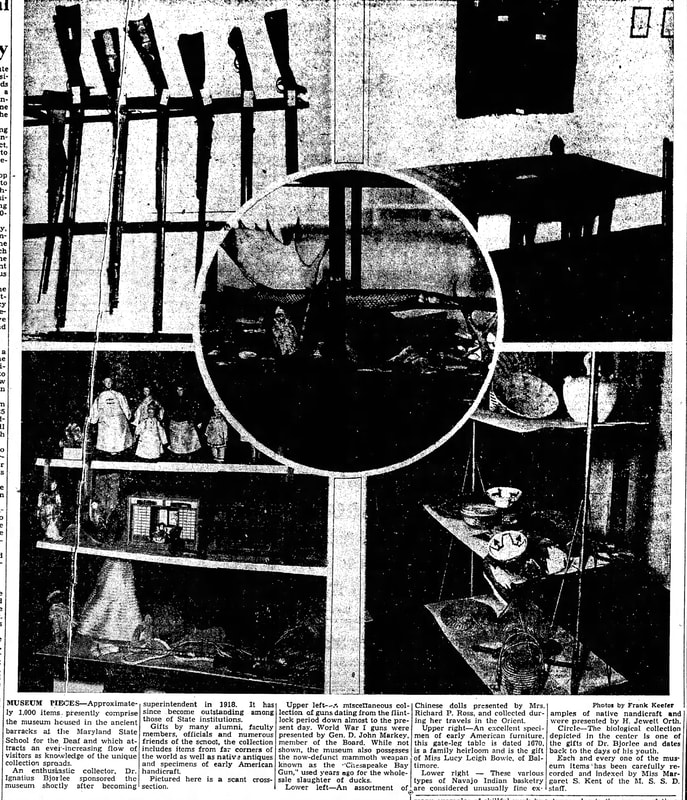

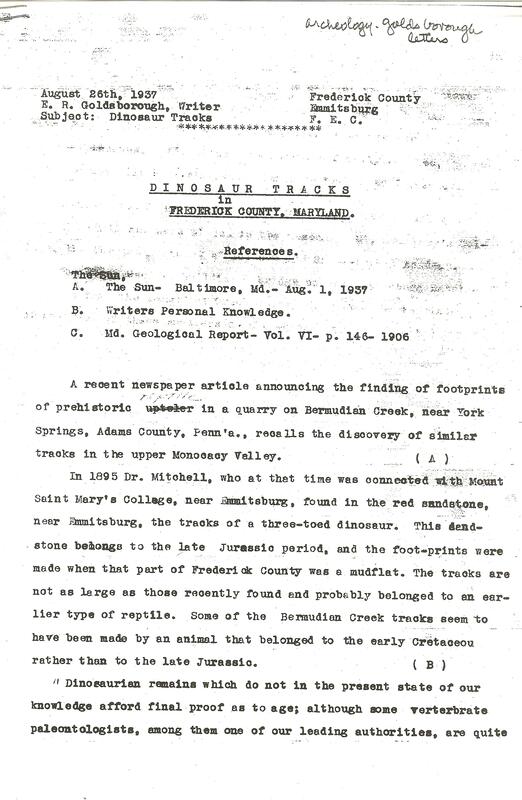

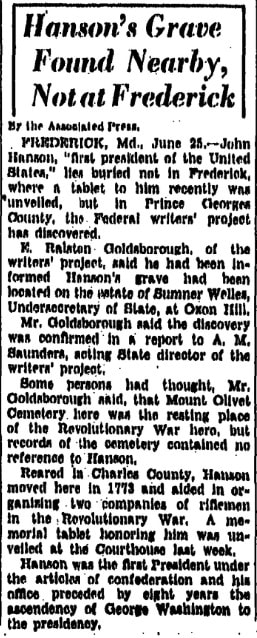

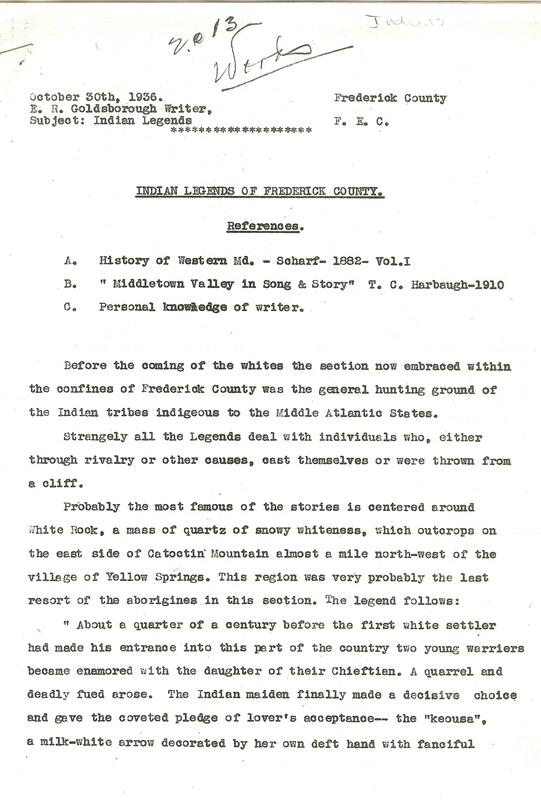

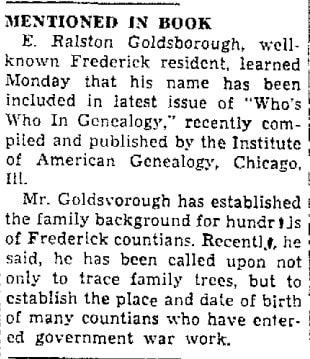

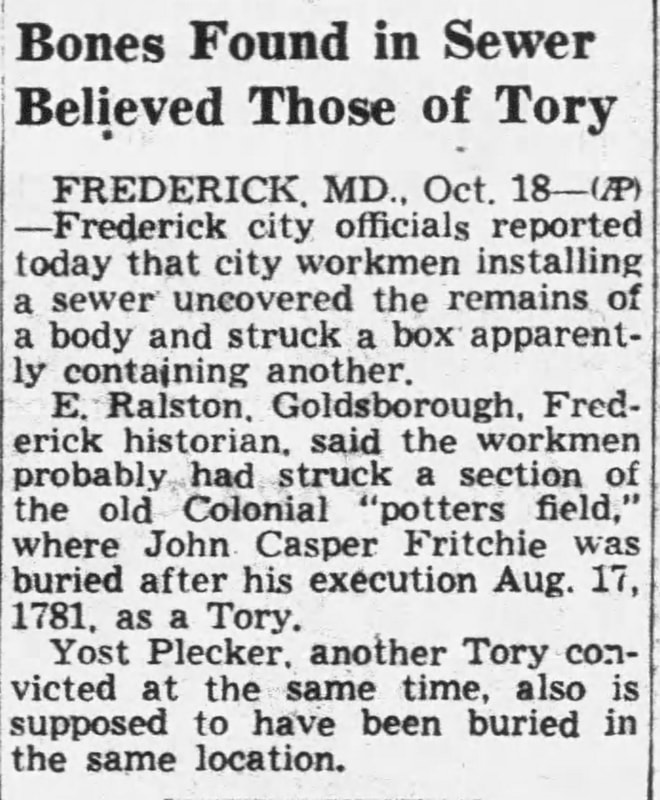

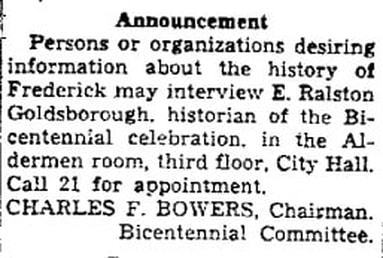

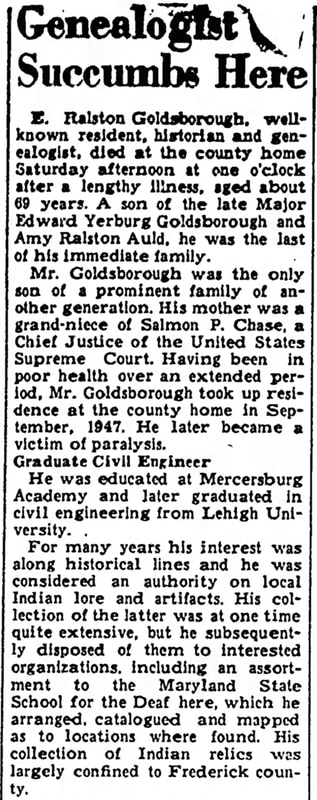

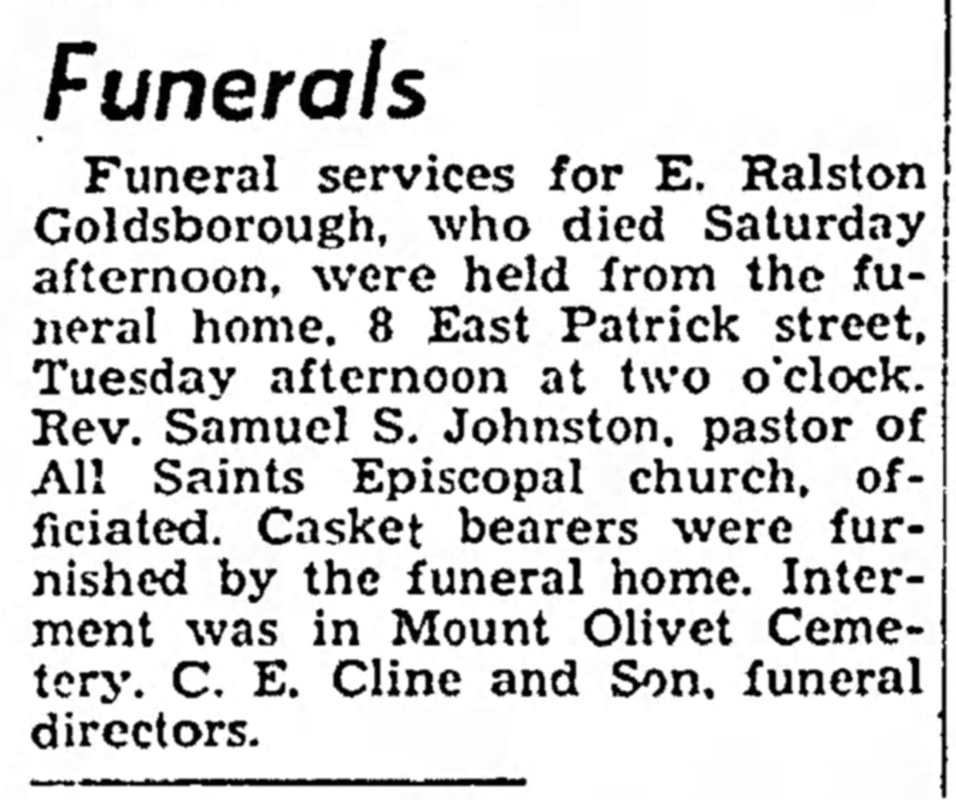

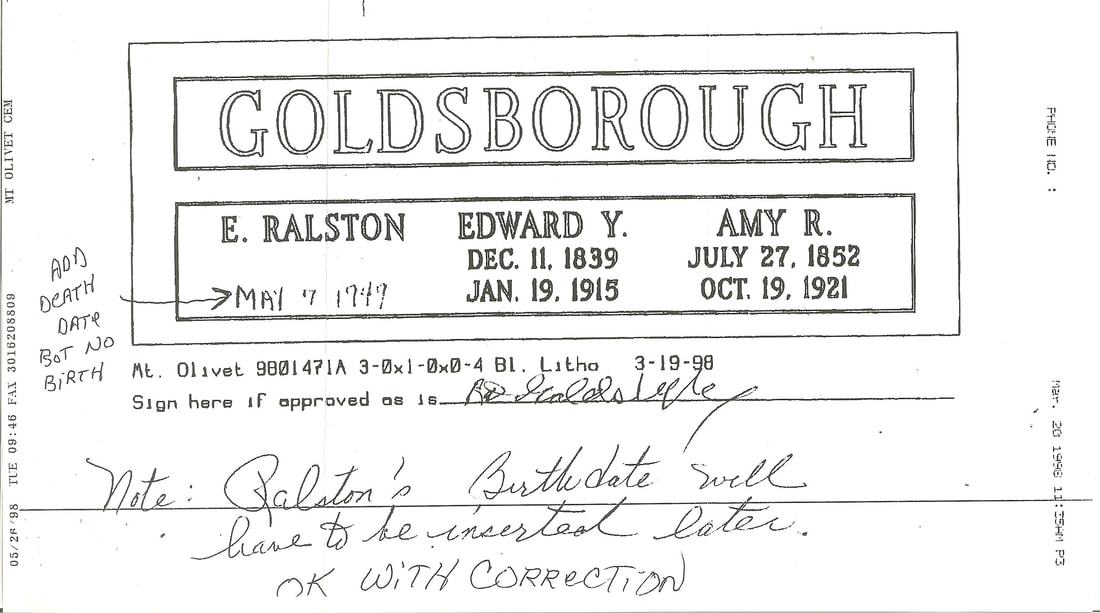

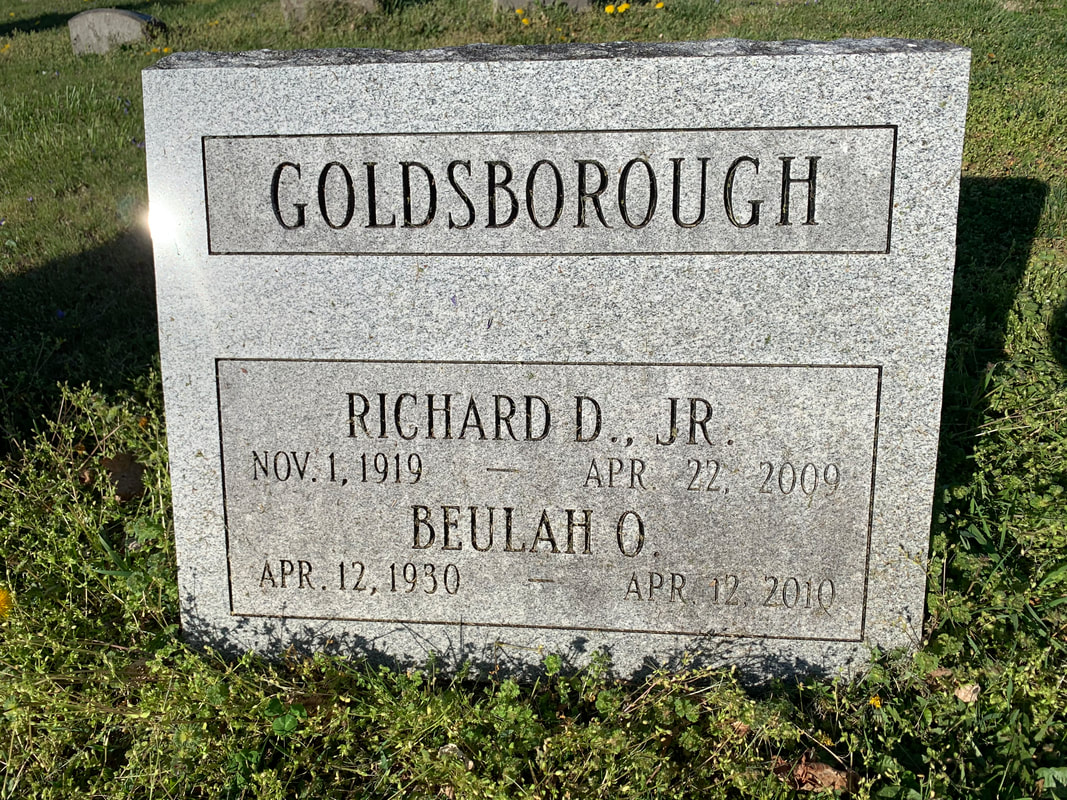

Spencer O. Geasey Spencer O. Geasey I had some prior knowledge and experience in the realm of archeology thanks to my work with a documentary produced in 1999 and entitled Monocacy: the Pre-history of Frederick County, Maryland. Here I got to learn first-hand from state archeologists and local/avocational lay people. One of these was my chief mentor for the project, Spenser O. Geasey (1925-2007). I would love to write a comprehensive “Story in Stone” on this New York native who spent the majority of his life in Frederick County, but he is buried in Mount Prospect Cemetery up in Lewistown (MD). This was close to his boyhood home of Mountaindale, which helped inspire his interest with arrowhead finds as a child. He always made it a point to tell me he was nothing more than an “avocational archeologist”—avocational translating to hobbyist without holding a degree in the field. Spencer was a World War II vet (304th Infantry/76th Division) who would make his living as Housing Manager at Fort Detrick. After retirement from the Army base, he worked as an archeological field assistant for the State Highway Administration. Although not formally trained in the field, his favorite hobby and passion would have him advising local, state and national professionals as he became an expert on Frederick’s native peoples through weekend exploration for fun. He walked the fields and carefully took notes which blossomed into extensive scientific reports for state archeological periodicals. Spencer regularly surface collected (with permission) and donated these artifacts (nearly 41,000) to the state collection housed at Jefferson-Patterson Park & Museum of Archeology in Prince Frederick in Calvert County. The MAC (Maryland Archeological Conservation) Laboratory has research space for working with the collections, a library of site reports and other material (such as field notes) and a variety of analytical equipment. Interestingly, this site along the Patuxent River in southern Calvert County is less than a stone’s throw from the birthplace of the famed Johnson brothers buried in Mount Olivet: Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr., James Johnson, Baker Johnson, Joshua Johnson and perhaps Roger Johnson (but the latter is debatable). Spencer kept his proverbial “ear to the ground” and notified state officials when he felt that local sites were in danger of being disturbed. This most often happened with commercial or residential development and roadways. He helped organize the Maryland Archeological Society, regularly spoke to school children and civic groups about native peoples and was involved in the publication of several articles about the topic here locally in Frederick County and the State of Maryland. All of these “avocational“-archeological activities led to Spencer receiving the Calvert Prize in 1993, the highest award for preservation in Maryland. In fact, he was the first archeologist to win the coveted honor.  Spencer's gravestone in Mount Prospect Cemetery, Lewistown Spencer's gravestone in Mount Prospect Cemetery, Lewistown In my special time spent with Spencer, we built a great friendship. He showed me prehistoric rock shelters and fish wiers in the river. We walked several, freshly plowed farm fields in springtime. Best of all, he took me on personal tours of three of the state’s most studied and important sites: the previously mentioned Biggs Ford site (north of Frederick), the Rosenstock site (east of Frederick City) and the Noland’s Ferry site (in southern Frederick County along the Potomac). You could not have had a better guide than the one I had. I also gained the opportunity through Spencer to learn about Frederick’s early archeologists, and others who dabbled in collecting under a bit more unscrupulous title as “relic hunters.” The noble archeologist goes about his search of artifacts in the name of science and history exploration, taking careful notes and handling any and all human remains with the greatest of respect. The relic hunter is generally looking to cash in on his finds, raiding ancient gravesites and selling off local treasures to collectors throughout the country. I want to note here that some of these “relic hunters” did not have bad intentions as they simply participated in a hobby, and kept the prized finds for themselves and unselfishly shared their artifacts with the community in terms of education as their efforts were a labor of love and learning. Spencer introduced me to two of these men, that not only were Frederick County natives, but are buried within the confines of Mount Olivet Cemetery—John Jacob Snyder (1890-1968) and Edward Ralston Goldsborough (1879-1949). John Jacob Snyder I will start with a man that Spencer Geasey interacted with personally. John Jacob Snyder was reintroduced to me when I created a memorial page for him a few years back in building our MountOlivetVets.com website. Snyder was a Frederick native and military veteran of the First World War. He was born on May 7th, 1890, the son of William F. Snyder and wife, Florence Walter. He grew up in a house located at 127 N. Market Street and attended Frederick City public schools. On his MountOlivetVets.com memorial page, I included the following information regarding military service after his induction as a 27 year-old private on March 23rd, 1918: 5/14/1918, Headquarters School for Radio Mechanics (College Station, TX) 7/2/1918, C Squadron, Ellington Field (Texas) 8/10/1918, Field Artillery Training, Fort Sill (Oklahoma) 10/9/1918, Promoted to Private First Class, 328th Aero Squadron 1/11/1919 12th Company, 154th Depot Brigade Honorable Discharge 1/28/1919 I’m assuming that John J. Snyder had an opportunity to add to his interests and experiences with native cultures while serving with the US Army in the western states of Texas and Oklahoma. It seems to have been a love nurtured in his youth in Frederick. While conducting internet and newspaper searches on him, I came across a small classified ad in the Maryland Archeological Bulletin dated January 12th, 1912 on page 34: In a later Maryland archeology publication, I found a story in which Snyder caught the attention of the state’s professional community. John had discovered what is commonly called today, the Rosenstock site. This is a Late Woodland village located atop a 7-meter-high bluff overlooking the Monocacy River. First off, the Woodland period is a cultural classification roughly representing the time period of 1000BC to the time of European contact in the 1600 AD. The bluff location of the former native village is a narrow, level promontory bounded by a deep ravine on the north, the river on the west, and a small stream on the south. The site, known since just after the turn of the century, has remained uncultivated since 1913 and currently is wooded. Since an initial exploration in the early 1900s, the Rosenstock site lay largely forgotten until it was reported to the State Archeologist in 1970. Subsequently, the State Archeologist’s office, in cooperation with the Archeological Society of Maryland, Inc. (ASM), carried out systematic testing of the site in 1979, and more extensive excavations in 1990-1992. Each of these projects was undertaken as part of the ASM Annual Field Session in Maryland Archeology. John Jacob Snyder discovered the particular site on October 15th, 1907. Snyder, then a 17-year-old, was apparently “hunting for dogwood” on the Samuel Rosenstock farm, today making up Clustered Spires Municipal Golf Course. Snyder related at the time, “I was keeping to windward that was to the east on account of the Dogs [Russian Wolf Hounds], and hiding behind a shock of fodder saw 3 nice arrows about the shock so it was found by mere coincidence but I never got the dogwood.” At the time of discovery, the site—having been cleared of timber in 1884—was plowed. Snyder reported finding abundant pottery shards, triangular projectile points, clay, stone, and bone beads, discoidals, shale discs (about 3” in diameter with a hole drilled in the center), celts, and clay and steatite pipes at Rosenstock, which he considered the “most outstanding site” in the Monocacy Valley. The valuable location took the name Snyder’s “Site #1,” and farm cultivation would cease in 1913 in an effort to assist future researchers. John J. Snyder married Frances Catherine Riehl and raised his family at 24 E. Fourth Street in Frederick. In addition to his work as an avocational archaeologist, he spent his career as an electrical repairman and vulcanizer (skilled worker with rubber). He proudly displayed his Indian artifact collection to professionals and county residents for decades until his death on March 9th , 1968. He is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area GG/Lot 170. Edward Ralston Goldsborough Although Spencer Geasey could only talk about “Ralston” Goldsborough anecdotally through his past research and findings, I actually had the opportunity to meet one of his close relatives. I was particularly interested in this man (Ralston) who, like Spencer, made an incredible contribution through his research and work resulting in scholarly research by a non-professional. Edward Ralston Goldsborough was born on July 8th, 1879, the product of a very interesting pedigree which included Robert Goldsborough (1735-1788), a delegate to the Continental Congress, and Frederick Town’s supposed first settler, John Thomas Schley. Ralston was the only son of a prominent attorney and veteran of the American Civil War, Major Edward Yerbury Goldsborough. I need to tell you a bit about this Goldsborough family first as valuable context can be gleaned in respect to Ralston’s interest in archeology, genealogy and local/Maryland history. Ralston’s 5th great-grandfather, Nicholas Goldsborough, arrived from England (via Barbados) a few decades after Maryland’s founding and settled near Kent Island in the late 1660s. The next two Goldsborough generations would accumulate wealth and settle in the Eastern Shore areas of Easton in Talbot County and further south in Cambridge, Dorchester County along the Chesapeake Bay and Choptank River.  Robert Goldsborough and family by artist Charles Willson Peale Robert Goldsborough and family by artist Charles Willson Peale The fore-mentioned Robert Goldsborough would rise to the highest ranks of Maryland politics and play a substantial role as delegate to the Continental Congress and Maryland’s participation in the American Revolution. He narrowly missed his chance at eternal fame as being a Founding Father. Like Thomas Johnson, Jr., he was not present in Philadelphia on July 4th, 1776 for the signing of the Declaration of Independence, having withdrawn his position six weeks earlier to help frame Maryland’s first state constitution. Robert Goldsborough was friends with fellow patriot, Thomas Johnson, Jr., and this likely guided a future Goldsborough connection to Frederick County. Robert’s son, Dr. William Goldsborough (1763-1826), moved to Frederick and bought several properties from Thomas Johnson, including Johnson’s 138-acre plantation of Richfield. Johnson, whose health was frail at the time, had accepted an invitation to live with his daughter and son-in-law at Rose Hill Manor. He had built the latter for the couple as a wedding gift.  Dr. William and wife, Sarah Worthington Goldsborough, lived here at Richfield until moving in town shortly before his death in 1826. The location for a new domicile was another property acquired earlier from Gov. Johnson. It sat on 115-117 East Church Street, later destined to be Frederick’s first public Female High School and later the headquarters of Frederick County Public Schools. Dr. William Goldsborough died without a will, but with debts which seems to be a recurring theme for family members in the future. His wife, Sarah, sold the Richfield property with mansion house on the east side of the Frederick-Emmitsburg turnpike road to John Schley in 1829 and granted the property on the west side to son, Edward Yerbury Goldsborough, Sr. (1797-1850). Edward, Sr. was our subject Ralston’s paternal grandfather, and had married Margaret Schley (1802-1876) a descendant of John Thomas Schley, the German Reformed Church’s first choirmaster and builder of Frederick’s first house. The wedding occurred in 1826. Edward and Margaret Goldsborough would have five children: Mary Catherine (1827-1899); William (1830-1853); John (1835-1885); Edward Yerbury, Jr. (b. 1839) and Robert Henry (1842-1882). The family obtained a town-home in downtown Frederick in the first block of W. Patrick Street, where Dr. Goldsborough based his work office as well. William's History of Frederick County says the following about Dr. E. Y. Goldsborough, Sr. : He was educated for the medical profession, graduated from the medical department of the University of Maryland, and began to practice in Frederick City in 1826. His untiring energy, his skill, and his devotion to his profession, soon brought him a large practice. Dr. Goldsborough was a polished gentleman, and was not only respected for his skill as a physician, but was beloved and esteemed for his kindness to all of his patients, especially to the poor. He died while out on his visits to patients, November 4, 1850. After her husband's death, Margaret Goldsborough continued to raise her children into adulthood from the residence on West Patrick Street, while still holding the farm property north of the city purchased by her late husband's parents from Thomas Johnson.  The Titus Atlas map of 1873 shows the Goldsborough residence in the first block of W. Patrick Street on the south side with a back yard stretching to Carroll Creek. This is approximately the site of today's Weinberg Center. (c.1910) view of the first block of W. Patrick St. (looking east). In the photo below, the author believes the former Goldsborough residence is the three-story home with twin dormer windows (3rd structure from right) captured in this photograph taken around 1910 Two of Mrs. Goldsborough's sons became noted professionals in their fields and participated in the American Civil War. Both received their early education at the Frederick Academy just a few short blocks from their home. John Schley Goldsborough chose the medical profession and graduated from the University of Maryland. On the outbreak of the Civil War, he volunteered as a surgeon in the Union army and was actively engaged in hospital work at Harpers Ferry and in this city. When the war came to a close he had become somewhat disenchanted of his profession. The doctor devoted himself to agricultural pursuits, having ample means for the purpose and lived as a gentleman. Upon graduation from the Academy in 1859, John's younger brother, Edward Yerbury Goldsborough, Jr., became a law student in the office of Joseph M. Palmer and was accepted to the Frederick bar in October, 1861. He opened his own practice at this time as the winds of war were swirling. In August of 1862, he would receive a commission in the Union army as a second lieutenant in the Eighth Regiment, Maryland Volunteer Infantry. In 1863, he was nominated by Frederick County's Union party to serve as State's Attorney (for Frederick County). Another historical account says that Edward "served briefly in the Maryland Infantry of the U. S. Army in 1862-1863, but was mustered out due to illness. Still, he was a volunteer on General E. B. Tyler's staff during the Battle of the Monocacy in 1864, for which he earned the rank of Major. Beginning in 1869, he served as a United States Marshal for the district of Maryland, and he is often referred to by either ''Major" or ''Marshal" in historical accounts. He was known as a fine lecturer on the Civil War and his foreign travels and as an active Agricultural Society member. Margaret Schley Goldsborough died on Christmas day, 1876. A few years before her death, she took great pride in the fact that her son Edward had courted a young debutante from the Midwest with familial ties to one of the most famous politicians and legal minds in the country. The couple married in 1874. Margaret was laid to rest beside her oldest son William, who died in 1853 at the age of 23, in Mount Olivet's area E/Lot 15. Her husband is buried on the other side of William. A large obelisk and ledger stones mark these gravesites. Within a few yards are the graves of Margaret's in-laws, William and Sarah Worthington Goldsborough, and her husband's brothers: Nicholas W. Goldsborough (1795-1840), a War of 1812 veteran, and Dr. Charles H. Goldsborough (1800-1862). These monuments are exactly across from the Potts Lot, the only area remaining "gated" in the cemetery. Finally getting back on track with the biography of Edward Ralston Goldsborough, his parents married in June of 1874. Ralston’s mother, Amy Ralston Auld, was a grandniece of politician/jurist Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873) who served as the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, replacing Roger Brooke Taney. She was born in St. Louis, Missouri and I'm assuming they met in Washington, DC where she lived with her famous relatives. Ralston spent his childhood in Frederick City at a family home then located at 54 West Patrick Street, this would be 114 W. Patrick Street with today's numbering system. Ralston attended school in the city and took an interest local figures in Frederick's history, and those that came long before. More history of the Frederick County Goldsborough family can be found within a Maryland Historic Trust' State Historic Sites Inventory property summary for another residence of Edward Y. Goldsborough, Jr. The aptly named Edward Y. Goldsborough House is located at 6739 Clifton Road west of Frederick. This was a family summer home and farm located on the eastern slope of Catoctin Mountain below Braddock Heights. Edward Y. Goldsborough, Jr. bought the property in the 1860s and Ralston places this as his birth location in later records.  Richfield Richfield Continuing through his youth, Ralston Goldsborough took delight in finding Indian artifacts in the fields that surrounded his grandparent’s former plantation of Richfield, located a few short miles north of Frederick City. The plantation house of the Schley’s (named Richfield) exists today and was the birthplace of Admiral Winfield Scott Schley, a naval hero of the Spanish-American War. He was also a cousin of Ralston. The Richfield mansion was childhood home to Ralston's grandfather as I had earlier said it had been the site of Thomas Johnson's former mansion, with a house rebuilt by Ralston's grandfather William after a devastating fired destroyed the original Johnson dwelling in 1815. It sits between today’s US route 15 and the Monocacy River. Ralston's grandparents had kept the property to the west of the turnpike which is basically today's site of Crumland Farms and Homewood Retirement Community. Many of the artifacts found by young Ralston likely came from inhabitants of the neighboring Biggs Ford site on the east side of the Monocacy. This was their immediate hunting ground, a primeval forest before the European settlers cleared the land for farming. Ralston began hunting other local Indian sites, tracing Indian trails and collecting artifacts. His early interests were encouraged by his mother, who worked as an assistant in the office of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute. Ralston would graduate from Lehigh University and afterwards serve as a civil engineer in Frederick County, with an office at one time in Winchester Hall.  The modern-day aerial view captures the former Goldsborough properties north of Frederick City and on both sides of US15 below the intersection with Biggs ford Road and Sundays Lane. The Richfield House is located within the small cluster of buildings across the highway from Beckley's Motel marked on the map. Goldsborough was in contact with professional archeologists at the Smithsonian, but most were too busy with research in far-off parts of the world to study the nearby Indian locations which he pointed out in Monocacy Valley. He too ingratiated himself to Maryland’s earliest professionals in the field and became one of them. Sometime between the Rosenstock site discovery in 1907 and October 1909, John J. Snyder—who communicated closely with other artifact collectors in the Frederick area—revealed the site location to E. Ralston Goldsborough. Goldsborough visited the site on October 10th, 1909, and on October 26th received permission from Samuel Rosenstock to carry out excavations. Here is a summary of his notes written in 1911.  Goldsborough said that the village site was visible on the ground as a dark discolored area covering either 1.5 or 1.6 acres “by actual survey.” Between November 5th and December 8th of that year, Goldsborough spent eleven days excavating a series of trenches at Rosenstock, which was then planted in clover. With one exception, which is not specified, the depth of the trenches did not exceed 12 inches. The trenches—situated “one hundred and ten feet from the river, about the center of the site and parallel with it” —are depicted on a plan map, but there are no identifiable landmarks shown; discrepancies between written measurements and with the scale also detract from the map. From these excavations, estimated at 361 ft, Goldsborough recovered nearly 3,000 objects, including pottery, clay pipes, steatite beads, bone implements, and triangular arrow points. Several thousand animal bones included those of deer, raccoon, bird, dog, turtle, and beaver. This research was included in various editions of The Archaeological Bulletin in 1912. E. Ralston Goldsborough had truly arrived! In a report from 1912, Goldsborough notes that the pottery at Rosenstock, with its distinctive rim collar, is different from the pottery types found at other sites in the Monocacy valley, and speculates that it is the result of Iroquoian or Siouan influence. He also illustrates some of the decorative motifs used in a series of “restored” pots. Despite being taken out of cultivation in 1913, the Rosenstock site continued to attract artifact collectors. According to Snyder, around 1920 two collectors (Dudley Page and Alan Smith) had the site plowed; “it paid off well in broken pipes discoidals ceremonial & other material.” The subsequent decades-long unplowed condition of the site notwithstanding, Rosenstock’s location remained known and it was occasionally surface-collected by various individuals, including Spencer Geasey, who brought the site to the attention of then-State Archeologist Tyler Bastian in 1970. Nonetheless, the fallow and/or overgrown nature of the site since 1913 afforded a measure of protection not seen at most village sites in the region. Sadly, although the notes and writings of Snyder and Goldborough survive, the fate of the early artifact collections is less certain. Snyder’s collection from Rosenstock (which came to include the collections of Dudley Page, Allen Kemp, and some of Alan Smith’s material from the site) was owned by a Mr. Dennis Murphy as of 1979. A small sample of ceramic shards collected from Rosenstock by Dudley Page is curated by the Maryland Historical Trust. Spencer Geasey’s surface-collected material from Rosenstock is included in the extensive collections he donated to the Maryland Historical Trust in 1992. Ralston’s Personal Life Let's return to E. Ralston Goldsborough's home life, shall we? Ralston can be found living with his parents well into adulthood and his thirties. His father died in 1915, which came as somewhat of a shock. He would stay with his mother until her death in 1921. Not long after, he finally settled down, at least temporarily. Ralston married divorcee Frances Lillian Roger (nee Ashbaugh) on November 22nd, 1922. The bride was the daughter of William Ashbaugh and Rachel Dyer. She had divorced her husband two years prior and was teaching school in Emmitsburg. The couple was married in Gettysburg and took up residence at his family farm on Clifton Road on the mountain. He inherited the farm upon his parent’s death. It appears that he raised chickens as several newspaper articles point to fair and other competition entries under his name. He began selling off portions of his property in the late 1920s before parting with the whole in 1930. During this time, the house was rented as a summer residence by wealthy Fredericktonians and others attracted to the vicinity of nearby Braddock Heights, the mountaintop village developed by the Hagerstown & Frederick Railway alonq with its amusement park. According to Anne Hooper's Braddock Heights: A Glance Backward, the Goldsborough House during this period was an unofficial "Frederick Country Club,” with prestigious social events and parties. Oh, the "Roaring Twenties," but apparently not a great ending to the decade, or start to the first for our subject. I found a 1931 directory that shows the couple living at 29 Jefferson Street. Sadly I also found the following classified ad printed in the Frederick paper that year: I had heard that Ralston battled the demon of alcoholism during his life, and this perhaps contributed to a Sheriff’s sale of his property and a subsequent divorce in the early 1930s at the onset of the Great Depression. A story exists that at this time Ralston could regularly be found walking the streets of Frederick offering to produce family genealogies for the price of a dollar. Although the Stock Market Crash of 1929 could have cost him his home, fortune and marriage, the Depression did eventually provide Goldsborough employment with an opportunity to continue his dream as an archeologist. He would be tapped as the local director of WPA (Works Progress Administration) work relief in the field of archeology for Frederick County. Through US government funding, Ralston had as his official sponsor the Maryland School for the Deaf. He investigated a number of local American Indian sites, including a rock-shelter and a small village. Although he maintained a healthy correspondence with other archeologists in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC, Goldsborough does not seem to have completed a formal report on his WPA investigations. Virginia Commonwealth University alumnus Brenna McHenry Godsey assembled and examined the available archival record on Goldsborough’s work housed at the Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland, while she was still a student. These records focused largely on Goldsborough’s pre-New Deal archaeological work. It remains unclear exactly what the nature of his relationship was with the Maryland School for the Deaf. Was the School simply a project sponsor, or did some of their charges participate in the WPA excavations? Regardless, Goldsborough produced a map showing numbered sites of special interest in Frederick County, and collected a vast array of artifacts which remain in the Bjorlee Archival Collection of the Maryland School of the Deaf. It is also thought that the Rosenstock material excavated by Goldsborough decades earlier may also be included in this same artifact collection prepared for the Maryland School for the Deaf during the WPA project. I had the opportunity to work with MSD back in 1997 in an effort to access and film Goldsborough’s map and hundreds of artifacts for my Monocacy documentary. I’m hoping Goldsborough’s treasures at the school will make their way out of storage again one-day, and go on display for local residents and visitors to behold.  Frederick's Pythian Castle (c. 1920) Frederick's Pythian Castle (c. 1920) Census records and directories show me that the couple apparently never formally divorced. Frances took up residence at 347 S. Market Street. in 1935 and can be found renting an apartment at 306 N. Market Street. in 1940. Ralston made his home during this time in Room 3 of the Pythian Castle, located in the middle of N. Court Street, a half block north of his childhood town home located near the corner of Court and W. Patrick streets—the site of today’s county courthouse. The files of the Frederick County Historical Society (Heritage Frederick) remain filled with Ralston’s research in the form of newspaper clippings and original manuscripts typed on onion skin paper. Many of those manuscripts and writings/research on Frederick history have the Pythian Castle address typed as their place of origin under Goldsborough’s hand. The last decade of his life saw him working as a top-tier genealogist. With his vast knowledge of Frederick's past, he was an easy choice to serve as Frederick City's official historian for the town's Bicentennial celebration in 1945. He wrote several articles and presented lectures on local topics and helped create a successful history pageant and other related events. Sadly, E. Ralston Goldsborough would suffer failing health in his final several years. This would not only throw him in poverty, but also led to a domicile change to the Frederick County Home at Montevue, northwest of town. Here he died on May 7th, 1949. He was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Area G/Lot 162. His grave, in the shadow of a large obelisk erected to the memory of his paternal uncle, Dr. John Goldsborough (1835-1885), was unmarked until a marker stone was placed around here in 1998 by a relative. This was during the time I was doing my research on Ralston for my documentary. I vividly recall contacting Superintendent Ron Pearcey back in late 1997 for help in finding the grave of E. Ralston Goldsborough. He took me to the unmarked grave and let me know that he had been working with a family relative living in Delaware who was paying for a monument to be done. I hoped this gentleman may be able to provide me with a picture and more insight into the man few remembered, but was responsible for a tremendous body of work on the native peoples in our area.  Richard D Goldsborough, Jr Richard D Goldsborough, Jr Ron gave me the name and address of Richard Duvall Goldsborough, Jr. of Bayville, DE. I was excited in contacting Mr. Goldsborough and soon found that he lived just a mile from my family’s beach trailer located near the Fenwick Lighthouse in Fenwick Island (DE). Mr. Goldsborough graciously invited me to dinner to discuss his “archeological cousin” the next time I was “down the shore.” This visit eventually transpired in the summer of 1999. No pictures came about of E. Ralston (as I am still in search of one), but Richard shared the story of his remembrance of attending Ralston’s funeral with his parents. Richard lived in Baltimore, as did his folks, at the time and said that his father had kept a long-time correspondence with Ralston. He recalled childhood visits to Frederick with his dad to visit the peculiar man who told them rich stories of family history and local Indians on each trip. Upon learning of his failing health in spring of 1949, Richard and his father traveled to Frederick to make plans for Ralston’s burial as the archeologist had made none for himself, and had no immediate family. It would have been customary for Ralston to have been buried in Montevue’s potter’s field. As the next of kin, Richard’s father made arrangements for Ralston to be buried with his own parents in a lot adjoining the previously mentioned Dr. John Goldsborough. Dr. John was Richard Sr.’s grandfather and Richard Jr’s great-grandfather. Dr. John named his son Edward Yerbury Goldsborough as well, and he is buried in this lot. Of course this man is Richard Sr.’s father, and was named in honor of Ralston’s grandfather—Edward Yerbury Goldsborough. Dr. John’s father was William Goldsborough, the Confederate brother of Ralston’s father, Edward Yerbury, Jr. So to review the complicated family genealogy, my friend Richard’s great-grandfather (William), and Ralston’s father (Edward), were brothers. My dinner host shared with me the fact that Ralston had lost all his money through personal vices and never got around to putting a proper headstone on his own parent’s gravesite. Ralston’s father had passed suddenly in 1915 leaving wife Amy in dire straits. She would die in 1921 and things never really straightened out for Ralston financially speaking. Richard said that his father had always spoke of putting a stone on the graves of Ralston and his parents but never got around to it either. This was unfinished business, and Richard, Jr. never forgot his father’s intention. With medical issues of his own, Richard contacted Mount Olivet in the late 1990s to pre-plan burial arrangements for both himself and wife Beulah in a pair of grave-lots within Dr. John Goldsborough’s family plot. His parents were laid to rest here back in the 1970s. The new stone was finally completed in 1998 and placed over the grave of Ralston and his parents. Although I talked to Richard on the phone just once more after our dinner and shared a mail correspondence a few years later, we lost touch with each other. Not knowing his fate, I took solace in knowing that he is here buried in Mount Olivet, having died in 2010—a decade after our dinner meeting. His wife, Beulah, died the following year. That night at his house, I would learn that Beulah’s sister was married to an elderly third cousin of mine living in northern Delaware, the oldest member in a family line. Author's Note: I originally wrote this blog in April 2020 and have tried over 15 times to boost this post (marketing terminology) so a larger audience could see it. I found that Facebook was actually limiting the number of people who could see it. When I attempted to boost which puts it in people's newsfeeds for a fee, I kept getting rejected due to breaking Facebook's political and election policy. This had me perplexed because I had briefly mentioned the following regarding E. Ralston Goldsborough's ties to earlier Maryland governors in the 1830s and 1916. The first was Robert Goldsborough. You recall that it was Robert’s son William who came to Frederick around 1800. Robert had another son (William’s brother) named Dr. Richard Yerbury Goldsborough (1768-1815). He is buried at Christ Episcopal in Cambridge, MD along with plenty of other Goldsborough relatives including Phillips Lee Goldsborough (1865-1946). Phillips Lee was Maryland's 47th governor, serving from 1912-1916. He later was elected US Senator and held that seat from 1929-1935.

In either case, E. Ralston Goldsborough, could trace his amazing Maryland lineage back to Continental Congress delegate Robert Goldsborough, and original immigrant to America, Nicholas Goldsborough (1640-1670). History is complicated and tedious at times, but it's certainly worth the "dig!" Somehow, this was dangerous info? I even removed this from the story to no avail. I soon learned that bots and AI perform the screening of stories and the fact checking on this social media outlet. I desperately tried to reach Facebook for further discussion on the subject. First, its nearly impossible to make human contact with them, and second, the international team-member I spoke to in 2020 (and another again a year later) had no clue what I was talking about and kept reiterating/parroting corporate policy. My story on Gov. Thomas Johnson in October 2019 experienced a similar fate, and I was accused of electioneering. But I pleaded, "TJ was a politician in the 1700s!!!" They still rejected my boost attempts. All my research work and writing and basically I was censored from having a larger audience seeing it. So I've tried to run this Goldsborough story in April 2021, April 2022 and again in April 2023 to highlight Maryland Archeological Month, but to no avail. So here I am, in May, 2023, and trying to circumvent "The Powers That Be"....Facebook. Hope you enjoyed this special "Story in Stone." ;)

1 Comment

Tyler

10/6/2023 11:16:57 pm

Thanks for the history lesson. Was wondering about native tribes around Frederick and came across this. Awesome!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed