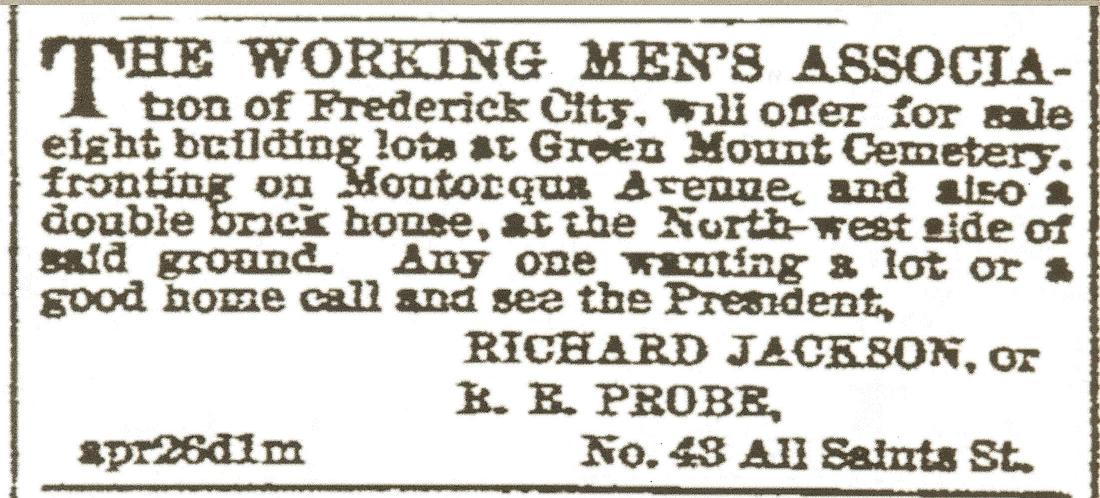

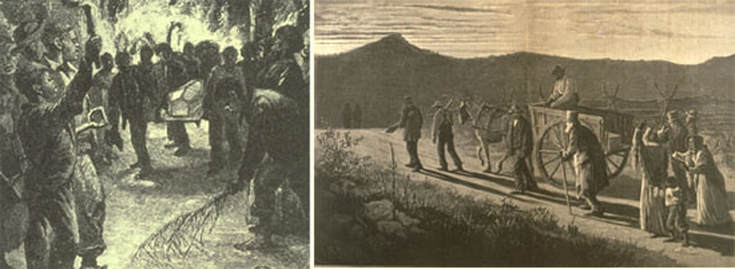

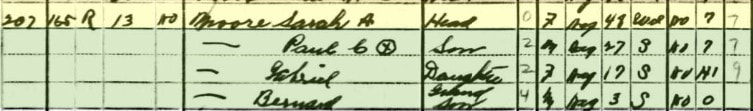

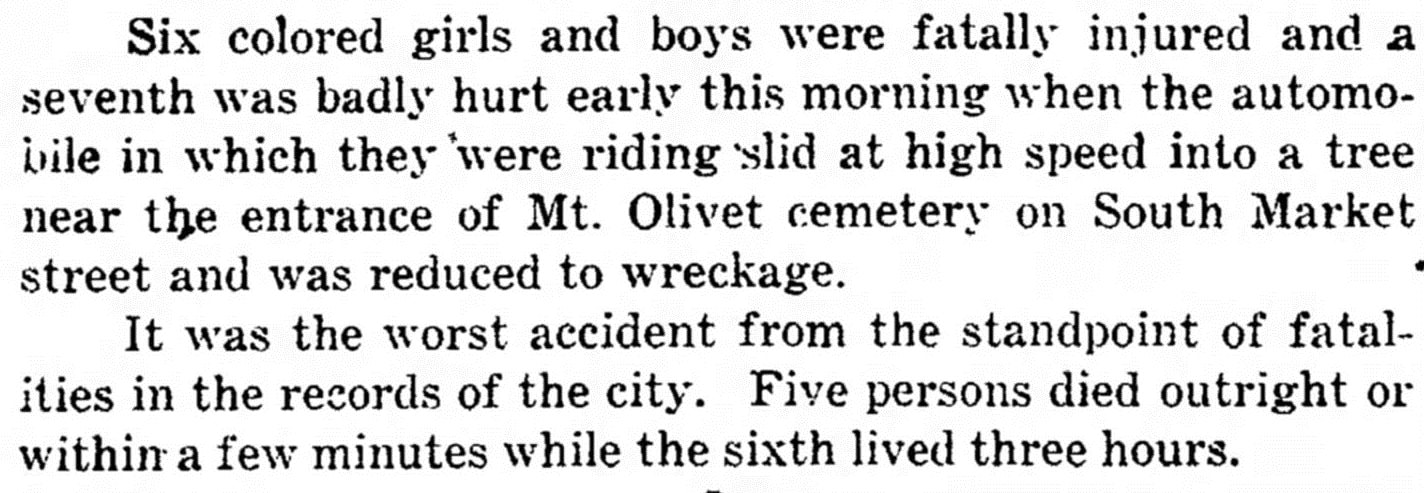

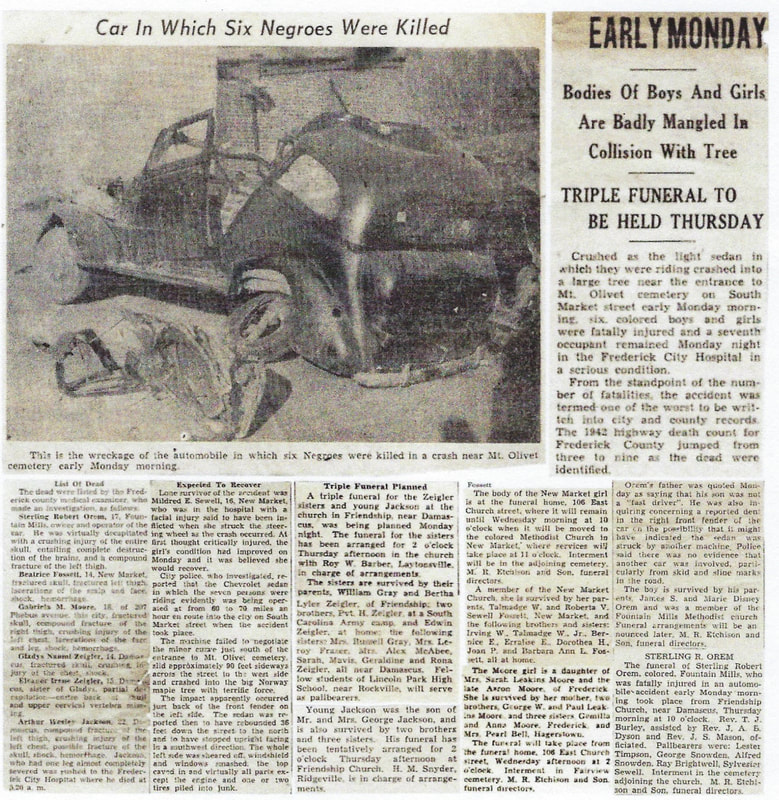

Grave of Dr. U.G. Bourne, Sr. in Fairview Cemetery Grave of Dr. U.G. Bourne, Sr. in Fairview Cemetery As February is quickly coming to a close, I was interested to see if I could tie-in topic relating to Black History Month. Some of you may recall the three-part series we featured (on this blog) last year at this time entitled: Sidestepping a Color Barrier: The first Black residents to be buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Yes, Mount Olivet, like so many institutions here in Frederick, was segregated up through the Civil Rights Movement. Although, I had a pretty good understanding of the genesis and evolution of Frederick’s “separate but equal” burying grounds, there is so much more to be gleaned by reading primary source materials of old to attempt to interpret or explain history. Of particular interest to me was the rise of Fairview Cemetery on Gas House Pike, which quickly filled the void left by the sale of W. 7th Street’s Greenmount Cemetery to the City Hospital (today’s Frederick Memorial Hospital) in the second decade of the 20th century. Fairview is the final resting place of Dr. U.G. Bourne, Sr., Frederick’s first Black physician and NAACP founder—a man who did so much over his lifetime to change mindsets and perceptions. Other Black history luminaries resting here include William O. Lee, Esther Grinage, John W. Bruner and Charles Brooks. As far as Greenmount, it was the predominant burying ground for Black residents of Frederick up until the time of its sale—if you will, it was “the Black Mount Olivet.” This sizeable cemetery was located on the ground now occupied by FMH’s west parking lot and garage. In reading last year’s series, you will also learn about the former All Saints’ Burying Ground (adjacent Carroll Creek) in the heart of Downtown, and the controversial story of Laboring Sons Cemetery. Much has been written about this latter location, sandwiched between E. 5th and E. 6th streets, employing a good measure of misinformation and embellishment which has caused media sensationalism and unique political posturing over the last two decades. Take it from someone who has thoroughly investigated the subject, the demise of Laboring Sons was self-inflicted by its trustees more than anything else. The most rewarding part of producing the 3-part series came as I tasked myself with finding the first individuals of color to be buried in Mount Olivet. I was pleasantly surprised with some of the revelations that came with discovering individuals such as Maria Harper, Laura Hill, Hester Houston, Abe Brighton, Martha Snowden and Bird Smith. All but Ms. Smith were former slaves, and death to them could have taken on the cultural mantra of “Homegoings.” As with other traditions, practices, customs and norms of Black culture, this ritual for dealing with death was shaped by the African-American experience. Author Sara J. Marsden, editor in chief for US Funerals Online, recently posted a feature on the topic entitled: “Homegoing Funerals: An African American Funeral Tradition.” Here’s an excerpt: The simplest explanation for the term “Homegoing” is that it represents the religious connotation of the deceased “going home,” to heaven and glory, and to be with the Lord. It is a Christian-based service, most commonly held in a chapel or church. The deceased is most commonly buried, after a very elaborate service, as the belief is held that their body will be resurrected. A homegoing funeral is often referred to as a “homegoing celebration” as it is considered to be an uplifting event celebrating the return of the soul to the eternal glory. The heritage of the homegoing funeral ritual has its origins back in Ancient Egypt. The ancient African Egyptian people had a rich culture of preparing for a funeral and preserving the deceased for their “after-life.” This could be noted as the origins of people of color demonstrating elaborate funeral practices. This rich Black heritage was brought to the United States during the era of slavery. During slavery the Black communities were not permitted to gather to conduct their funeral rituals for fear that they would conspire to revolt. Slaves that died were ordinarily just buried without any ceremony in un-marked graves in non-crop producing ground. However, at the same time slaves would be responsible for the preparation of the deceased plantation owner’s family following a death and preparing the elaborate family gatherings held to mourn the deceased. Controlling the repressed slaves and preventing an uprising was an ever-difficult task for the plantation owners, especially as the number of slaves on a plantation could begin to outnumber the plantation owner’s family and managers. So white Christian religion was introduced to the slaves to help pacify and subjugate. Many enslaved Blacks believed death meant their soul would return home to their native Africa. The Old Testament stories of God and Moses freeing a captive and enslaved race resonated with the slaves. The New Testament stories of Jesus and promises of glory in heaven and a far better after-life allowed slaves to forge through the turmoil of mortal life and look forward to the day when they would return home to the Lord. They fully embraced Christianity and death, for slaves, was viewed as freedom. Their death rituals were jubilant and it became one of the earliest forms of African American culture. Anyway, I invite you to partake in last year's 3-part story, you'll find links at the end of this article. Deaths occur within feet of FSK Monument While performing research work last year for the above-mentioned “Stories in Stone,” feature, I came across an especially traumatic and chilling event which occurred at Mount Olivet Cemetery 76 years ago. I found this article innocently enough while plugging word combinations into the search engine for the online Newspapers.com archival site. Among my searches, I eventually typed the words Mount Olivet Cemetery, Frederick, Negro, and death. Sadly I immediately found the following article headline, dated February 23rd, 1942. It appears that a horrific early morning car accident occurred just outside Mount Olivet’s picturesque front gate. Then superintendent Cyril Klein would be the first to see the grisly scene. The driver of a sedan entered town from the south on S. Market Street, going at a rate of 60-70 miles/hour. He lost control while attempting to negotiate the slight bend in the road. This was coupled with a wet road surface. The car subsequently slid 90 feet to the west until slamming into an aged Maple tree—one planted around the turn of the 20th century in front of the Superintendent's House and outside of the cemetery’s fence (fronting on S. Market Street). The reckless driving of an inexperienced driver was blamed for triggering the crash. Only one of the passengers was a Frederick City resident, hailing from nearby Phebus Avenue, roughly six blocks from the accident scene. This was 18 year-old Gabriela M. Moore. It was thought that the group was solely in town to bring Gabriela home. Unfortunately for the young lady and her friends, there would be six “homegoings” and only one homecoming. Six out of the seven occupants in the ill-fated sedan perished as a result of this tragic event—most expiring on impact. The driver was 17 and the others in the car ranged from 22-14 years of age. A lone survivor, Mildred E. Sewell of New Market, would spend the next month in the hospital, but would make a full recovery. I would eventually come across a better copy of the article from a scrapbook. This clearly shows the vehicle involved in this tragic accident. Up to that time, this was the single, deadliest automobile accident in Frederick County’s history. I venture to guess that it remains the worst in Frederick City history, and among the worst in county history. All in all, I was somewhat taken aback by the graphic level of reporting for this story, which also included a photo of the smashed-up automobile, but I couldn’t quite make it out clearly from the newspaper copy I had found. Nationwide, north and south, it was not uncommon in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s for newspapers to include reports of odd and awful accidents and deaths befalling Blacks and immigrants. I have included the initial report of this accident appearing in the February 23rd edition of the Frederick News. I still find the description of injuries a bit too much, especially in respect to an era with a backdrop of the Second World War. Frederick’s Gabriela Moore was laid to rest in Gas House Pike’s Fairview Cemetery on Wednesday, February 25th. A triple funeral would be held in Damascus, and others took place in New Market and Fountain Mills near Kemptown. Burying grounds are no strangers to victims of automobile accidents. Within Mount Olivet, there are hundreds. However, anyone would find it puzzling, and moreso ironic, to learn that a cemetery had played a contributing role in the deaths of six young people. So very sad.. Click any of the above icons to read more.

6 Comments

Joe Fitzgerald

2/25/2018 07:07:02 am

The headstone for Gabriela appears to be misdated....1941 instead of 1942?

Reply

Chris Haugh

2/26/2018 08:47:05 pm

Yes, I noticed that too, not to mention that Gabriela's middle initial should be an M. And not an N. Must have been placed many years later.

Reply

Irene Packer-Halsey

2/25/2018 12:28:10 pm

Your articles always fascinate me. This so sad.

Reply

Lorraine Blakeslee

2/25/2018 05:28:33 pm

Could you please identify the cemetery behind the current Heslth Dept. I was under the impression that was s Black cemetery or was it a general pauper testing ground

Reply

Chris Haugh

2/26/2018 08:57:07 pm

The burying ground at Montevue was a puaper's cemetery, referred to as Potter's Field. And Montevue was the area's second almshouse, Home to indigent, and needy folks. I have also seen references to "the Institutional Cemetery," and as others think this was downtown (either another name for Laboring Sons or adjacent Laboring Sons) I seem to believe this to be another name for the Montevue cemetery since Montevue, was in fact, an institution, itself.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed