|

Like so many of these “Stories in Stone,” I seem to just fall into them by accident every once in a while. Something usually catches my eye, be it an interesting name, an intriguing newspaper story, an anecdote from a visitor or family historian, a trigger relating to one of my past research projects, or in this week’s case—it’s “the stone” itself that got me thinking. Mid-last week, I found myself walking around Area B, one of Mount Olivet’s oldest sections, not far from the cemetery’s main entrance. I was taking photographs of World War I veteran graves for our www.MountOlivetVets.com website when a large monument came clearly into view. It was roughly 12-foot tall and I had never really taken notice of it before. The memorial is a very attractive marble monument, with intricate architectural features and topped with a shaft with an urn at the top. Around the shaft is a sculpted laurel wreath which is said to represent great distinction and “victory over death,” in the form of eternity or immortality.

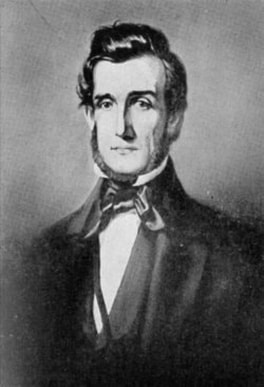

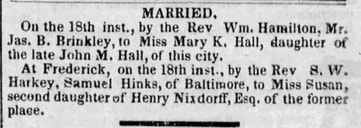

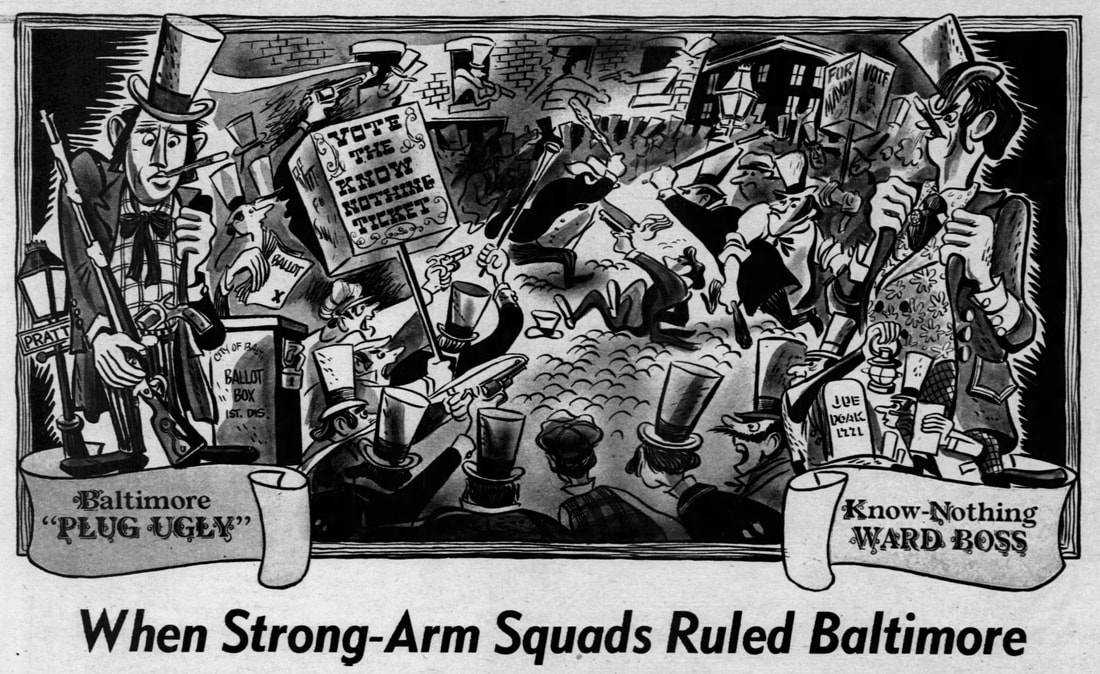

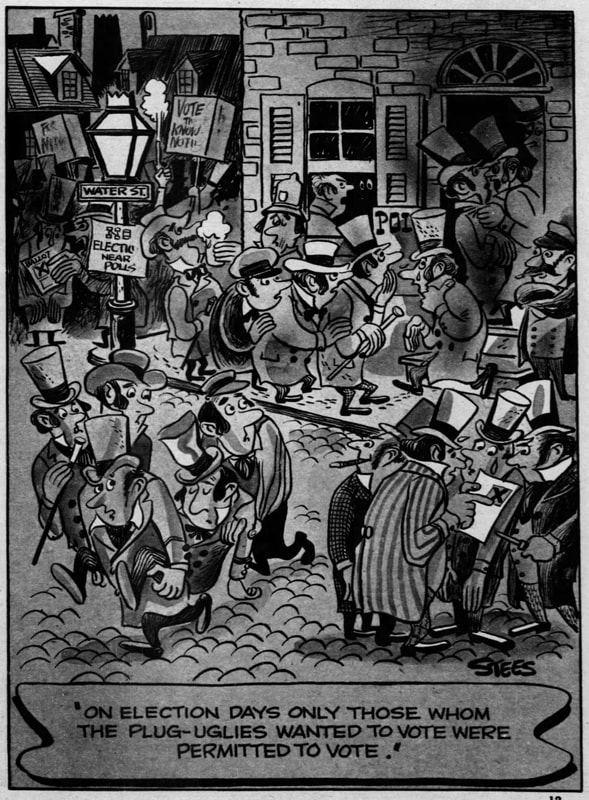

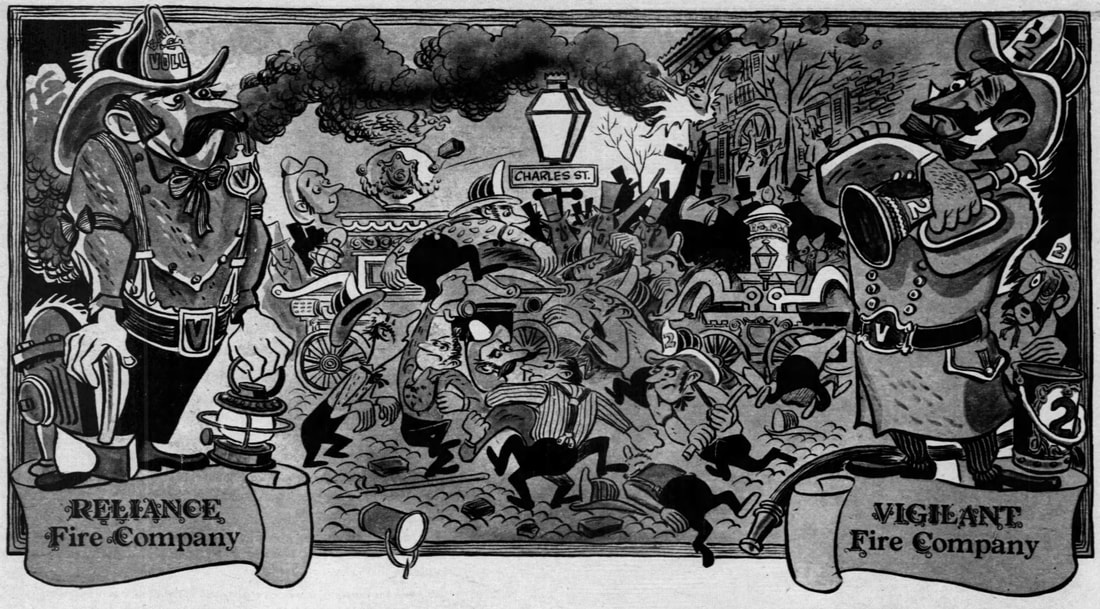

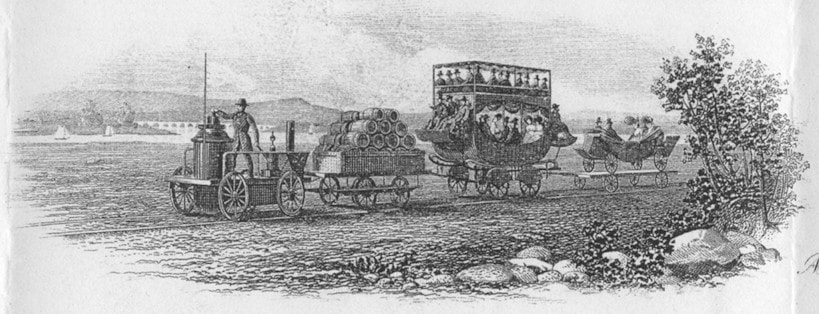

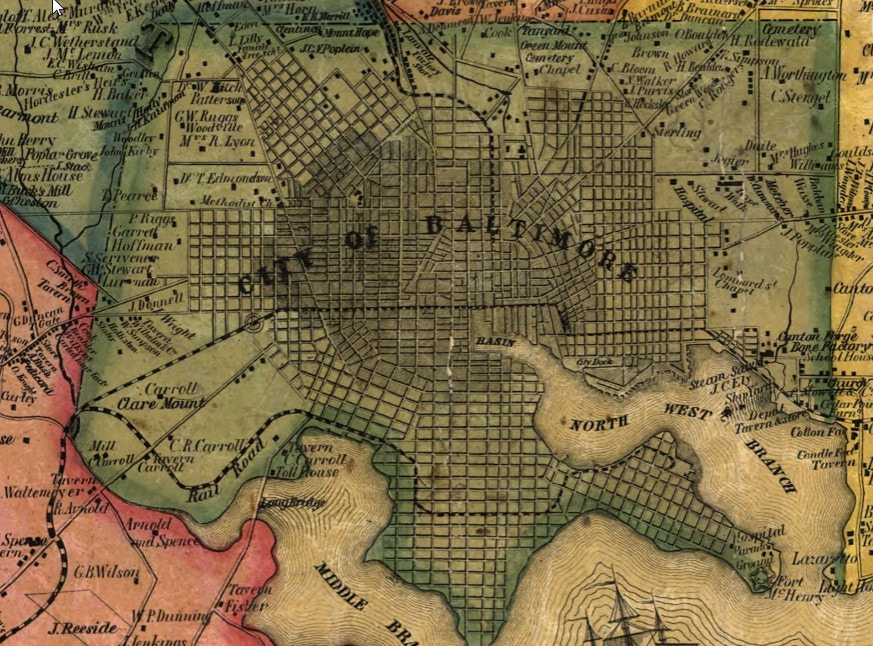

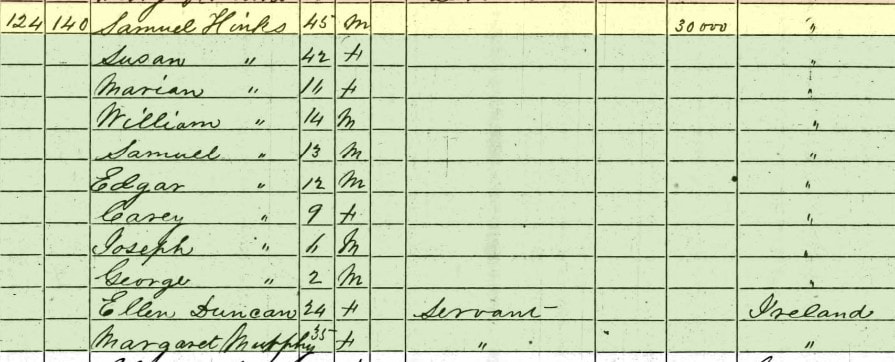

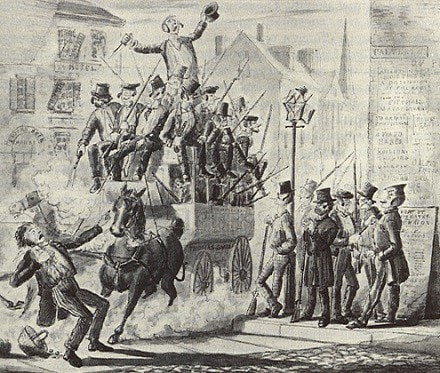

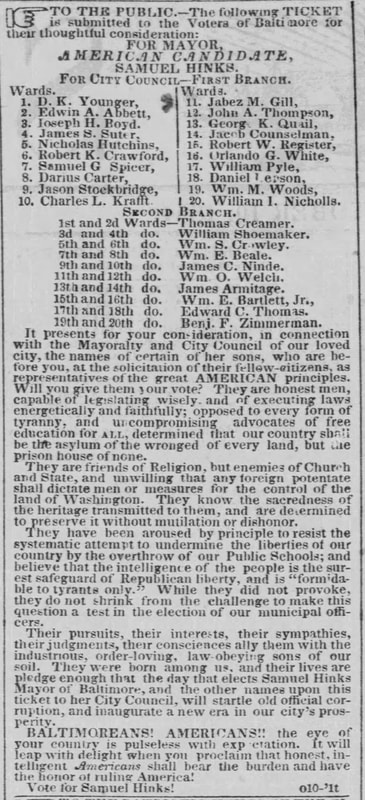

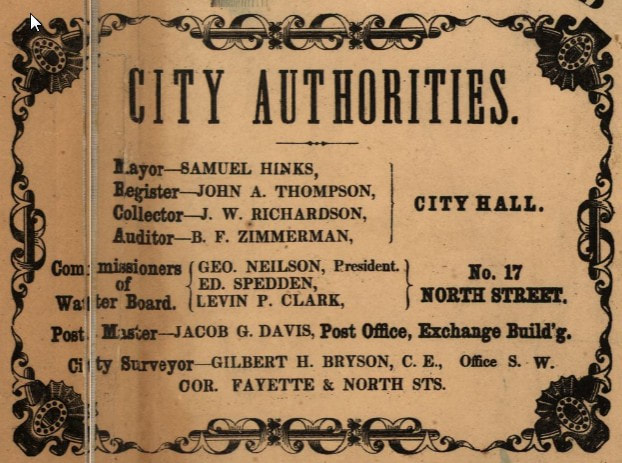

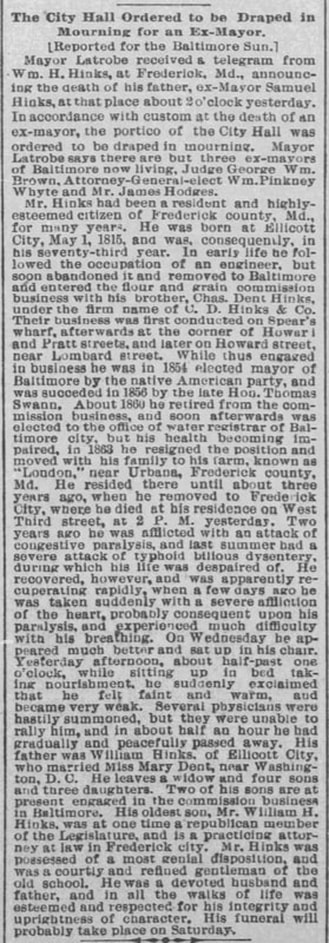

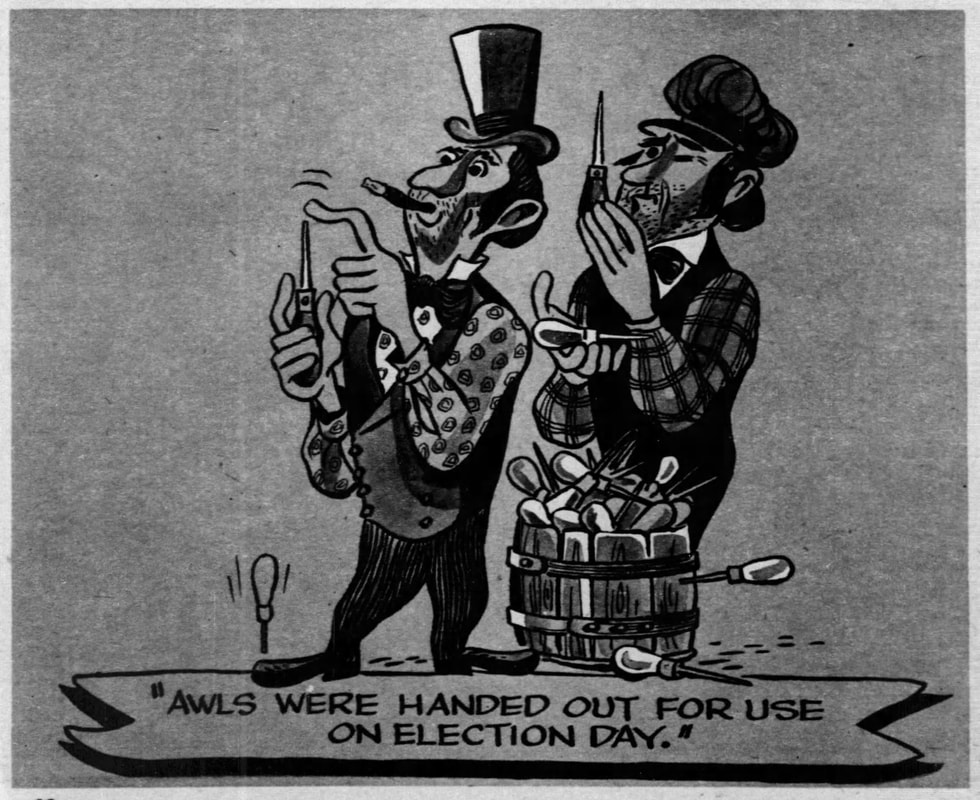

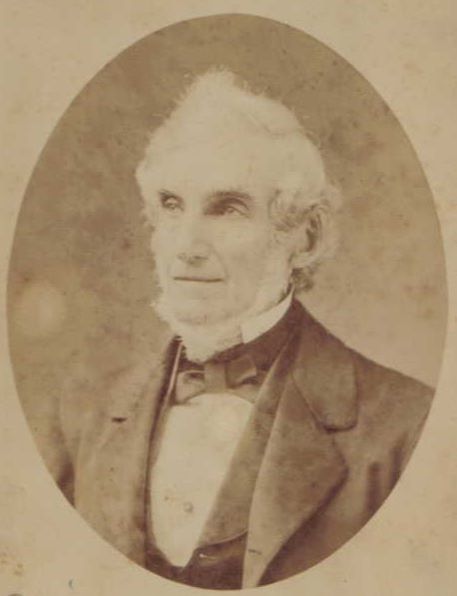

Samuel Hinks (1815-1887) MSA SC 3520-12475 Biography: Samuel Hinks was Mayor of Baltimore from November 13th, 1854, to November 10th, 1856. During this administration an ordinance authorizing the erection of a new City Jail was passed and the contract for the building was signed. The waterworks, which supplied Baltimore, were acquired from the Baltimore Water Company and a Water Department was organized to operate the system as a municipal plant. An ordinance passed during the latter part of this administration provided for taking water from several mill-dams on the Jones Falls and Stony Run, conducting this water to a reservoir and thus supplying the City. Other legislation authorized the construction of a new Western Female High School, Fayette, near Paca Street; two other school buildings and establishing a floating school for training youths for nautical pursuits. Provision was made for placing iron bridges over Jones Falls at Pratt, at Gay and at Baltimore Streets, and for a new market house for Lexington Market from Paca to Greene Streets. Legislation to open large portions of Hanover and Eager Streets was approved. A Councilmanic resolution was passed requesting Congress to establish a Marine Hospital at Baltimore. Agents representing the City in executing the McDonogh will were named and directors for the school (McDonogh) were appointed. Authority to sell the City's interest in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was granted. A resolution petitioning the Legislature against a bill then pending to erect the Long Bridge over the Patapsco River and Middle Branch was passed. The bridge, however, was built and but recently razed, being replaced by the new Hanover Street structure. The House of Refuge (Maryland School for Boys) on Frederick Road was opened. One of Mayor Hinks' messages contained a proposal to sell Richmond and Cross Street Markets.  Samuel Hinks Samuel Hinks The Continued Search The Maryland archives page gave me a pretty good start. I was fascinated with the fact that we had a mayor of Baltimore buried here in Mount Olivet, something likely not known by cemetery staff and local historians over the last century. My questions now centered around the obvious: “Why was he buried here in Frederick, and not Baltimore?”; “Did he die here?”; “Was he originally from Frederick?”; “Are other family members buried within Mount Olivet?” I knew I’d soon be looking at such local sources such as Mount Olivet’s cemetery records, Ancestry.com, T.J.C. Williams History of Frederick County, and Jacob Engelbrecht’s Diary. Before I did, however, I wanted to see what the Wikipedia page for Samuel Hinks had to say. It was definitely less flattering than the State Archives biography, possessing the innuendo that Hinks perhaps acquired his job by “mob rule,” both literally, and figuratively. Here is what Wikipedia had to say: Samuel Hinks was born in Ellicott City, May 1st, 1815. In early life he followed the occupation of steam engineer. Removing to Baltimore he entered the grain and flour commission business, later establishing a partnership with his brother, Charles Dent Hinks. Samuel Hinks was elected Mayor by the "American Party" in 1854. In 1860 he retired from the grain commission business and shortly thereafter was elected Water Registrar, which position he held until 1863. He died November 30th, 1887. In 1854 Samuel Hinks was elected Mayor of Baltimore, standing as a candidate for the nationalist anti-Catholic “American Party.” Members of the party were popularly known as "Know-Nothings" because, when asked about their secret organizations, their members were said to reply "I know nothing.” I learned that this led to something referred to as the Know-Nothing Riot of 1856. I quickly switched gears to find out what that was all about. The Know Nothing Riot of 1856 (courtesy of Wikipedia) During the mid-1850s, public order in Baltimore had been threatened by the election of candidates of the American Party. As the 1856 Mayoral elections approached, Samuel Hinks was pressed by Baltimorians to order the militia of General George H. Steuart in readiness to maintain order, as widespread violence was anticipated. Hinks duly gave Steuart the order to ready the militia, but he soon rescinded it. In the event, violence broke out on polling day, with shots exchanged by competing mobs. In the 2nd and 8th wards, several citizens were killed, and many wounded. In the 6th ward, artillery was used, and a pitched battle fought on Orleans St between gangs of Know Nothings and rival Democrats, raging for several hours. The result of the election, in which voter fraud was widespread, was a victory for the Know Nothing candidate, Thomas Swann, by around 9,000 votes. Swann duly succeeded Hinks as Mayor of Baltimore. Wow, this info all came to me thanks to curiosity in wanting to know who was buried under that handsome monument in Area B of Mount Olivet. I would have been simply satisfied with his accomplishments as mayor, but I had learned that this was a man embroiled in an amazing time in our history—the eve of American Civil War. Baltimore would serve as a microcosm of what was taking place on the national stage. Civil War Connections A few years ago, I had the once in a lifetime opportunity to work with some of the best Maryland Civil War authors and historians, as I assisted in producing a film documentary with Maryland Public Television entitled “Maryland’s Heart of the Civil War.” One of the “on-camera” commentators for the project was a great historian named Daniel Carroll Toomey. Dan recently served as special curator for the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore throughout the 150th Sesquicentennial commemoration of the “war between the states.” One of the topics I asked Dan to talk about (within the documentary) was the infamous Baltimore Riot of 1861, commonly called the "Pratt Street Riots.” This was a civil conflict that took place on Friday, April 19, 1861, on Pratt Street, in Baltimore. The combatants were anti-war "Copperhead" Democrats (the largest party in Maryland) and other Southern/Confederate sympathizers on one side, and members of Massachusetts (and some Pennsylvania) state militia regiments en-route to the national capital at Washington. These men came to Baltimore via the railroad as they had been called up to protect the Union capital in response to recent actions at Fort Sumter and the secession of states. The fighting began at the President Street Railroad Station, spreading throughout President Street and subsequently to Howard Street, where it ended at the Camden Street Station. The riot produced the first deaths by hostile action in the American Civil War and is nicknamed the "First Bloodshed of the Civil War.” The gangs of Baltimore played a large role in the violence, thus resulting in Baltimore being put under martial law for the duration of the ensuing war. Federal Hill was constructed by the Union Army, and large artillery guns were pointed at Baltimore’s harbor and center city area as a deterrent. Dan Toomey shared with viewers the fact that Baltimore was often seen as the northernmost “Southern city,” having more in common with Richmond (154 miles away) than with Philadelphia, only 89 miles distant. Add to that a penchant for raucous gang activity, and you surely have a powder keg on your hands. So seldom do we see unhappiness with particular politics actually escalate into anger and irrational behavior. I’m being sarcastic of course.  In case you are interested in learning more about the Pratt Street Riots, click on the following link to see our MPT interview with Dan Toomey regarding the April 19th, 1861 event: https://vimeo.com/95439373 I set out to glean some information on gang makeups in Baltimore preceding the 1861 Pratt Street event. I also had a small visual in my head from modern times, in which many of us saw a more recent riot play out 154 years later live on our television and electronic device screens just three years ago on April 27th, 2015. This ugly episode was brought in response to the death of 26-year-old Freddie Gray at the hands of officers with the Baltimore City Police Department. Following Gray’s funeral, civil disorder intensified with looting and burning of local businesses and a CVS drug store, culminating with a state of emergency declaration by the governor. Maryland National Guard was deployed to Baltimore, and a curfew was established. Another major period of unrest and upheaval occurred 50 years ago this month in Baltimore with the infamous race riots of 1968. This followed the April 4th assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Mobtown To get a feel for the earlier Civil War period that preceded the Civil Rights movement by a century, there is no better illustrative tool than the 2002 Martin Scorsese film “Gangs of New York” starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Daniel Day-Lewis. Saying this feature includes a pretty violent depiction of large city “gang life” of the mid-nineteenth century is an understatement. As the title implies, this movie is about New York City’s historic gangs that were centered in the Five Points area of lower Manhattan. Elements of ruthless crime and political corruption pepper this film, amidst the legendary historical event of the New York City Draft Riots of July 13-16th, 1863. So what was the “gang atmosphere” like in Baltimore at the time of Samuel Hinks’ rise to power in the 1850’s? Well, I checked another source to learn more about Baltimore’s earlier nickname, the one before “Charm City.” It was known as “Mobtown.” The earliest print documentation of the term Mobtown occurs in an 1838 copy of The Baltimore Sun; yet, it is said that by that time the name was already well established. One of the earliest tales comes from the turmoil of the American Revolution in 1777. A group of anti-British Baltimoreans called the Whig Club congregated outside the home of William Goddard. Goddard was the editor of the Maryland Journal who expressed pro-British sentiments. The mob forcefully removed him from his home and tarred and feathered him in the street. In response to the violence of the Whig Club, then Governor of Maryland stated the following on April 17, 1777 “all bodies of men associating together… for the purpose of usurping any of the powers of government, and presuming to exercise any powers over the persons or property of any subject of this State, or to carry into execution any of the laws thereof on their own authorities, unlawful assemblies.” A similar attack would happen to Federalist publisher Alexander Contee Hanson who successfully warded off a mob during the War of 1812. Ironically, Baltimore would erupt in riot in protest again in 1835 and 1839 in addition to the aforementioned 1856 and 1861 unfortunate events—all connected with local and national political developments. As stated before, Samuel Hinks was associated with the Know Nothing faction. To review, this group earned its name because members answered that they “knew nothing” when questioned by authorities regarding their aggressive activities. The Know-Nothings were particularly strong in Baltimore, where they included groups in the majority of wards with such unusual and colorful names as the Blood Tubs, McGonigan’s Rip Raps, Natives, Rough Skins, Tigers, Black Snakes, Wampanoags, Regulators, Double-Pumps, Hunters, American Rattlers, Butt Enders, Blackguards and so on. I found other great sources for information on these gangs courtesy of the Baltimore Sun with an article from May, 1951 by Ernest V. Baugh, Jr.; and by content provided on the Baltimore City Police Department website. The following is an excerpt from the history section of the website: “Gangs of young men parade public thoroughfares, armed with knives and revolvers,” wrote the Baltimore Sun in 1857, describing the makeup of these groups, which relied on violence and intimidation. “Collisions have been frequent between Americans and citizens of Irish and German extraction. The most bitter hostility has been encouraged between native and foreign-born citizens.” One of the most notorious gang of Know-Nothings in Baltimore was called the Plug Uglies. In 1857, the Washington Star called it “as pestilent and scrofulous a brood of scoundrels as hell itself could vomit from its vilest crater.” Growing out of the Mount Vernon Hook-and-Ladder Company—an all-volunteer firefighting group—the Plug Uglies were nasty, contemptible political gangsters who generally ran with McGonigan’s Rip Raps and often tangled with any Democrats in the city. According to folklore, the name “Plug Ugly” possibly refers to a specific gang member who was considered ugly to look upon but generous with his tobacco plugs—an inverse of the expression “ugly plug” or the “ugly blows” the gang delivered in its fights. Eventually, the term would be linked to anyone who was considered a “rowdy.” Members took pride in their brutal actions, even composing songs about their “valor” and strength. One such ditty was entitled “The Plug Uglies!” The song praises the gang’s ability to help elect or run out particular political candidates, including mayoral candidates, as well as former president Millard Fillmore, who ran an unsuccessful reelection campaign in 1856 as the American Party candidate. During the election, he only carried Maryland. In 1858, Maryland would receive its governor, Thomas Holliday Hicks, courtesy of the American Party and its Know Nothings. Although it may sound strange today to hear of a firefighting company described as violent, members of the Plug Uglies’ Mount Vernon Hook-and-Ladder Company were just as likely to get into a fight with a rival company while on the scene to extinguish a fire. As flames raged and threatened surrounding buildings, the firefighters would regularly ignore their duties to engage in “battle royales” with one another, using their axes, picks, hooks and even the street cobblestones and sidewalk bricks. In fact, some of the members were accused of starting several fires. So our Samuel Hinks must have quite an individual to have gained the support of the Plug Uglies, at least in that municipal election of 1854. Samuel Hinks (before Baltimore mayoral term) TJC Williams’ “History of Frederick County” states that Samuel Hinks was a native of Frederick County, where he was born on May 1st, 1815. This already contradicts the Wikipedia biography which claims that he was born in Ellicott City. Samuel’s father, William Hinks was associated with Ellicott City, however, and the town’s namesake progenitors—the Ellicott brothers. William Hinks was a machinist who would supposedly serve as superintendent of the Ellicott Mills operation. Through further research, I found that, in the year 1823, William Hinks purchased a stone dwelling structure from the trustees of John Ellicott. The location is on the eastern approach to Ellicott Mills coming from Baltimore on the famed roadway that would become known as the National Pike. This building is still standing and is commonly referred to as the Bridge Market house.  In 1828, William Hinks received a contract from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad “to lay the first track, on about seven and a half miles, of the second division, next above Ellicott’s Mills.” This was a big deal as the famed railway broke ground on July 4th, 1828. It would reach Frederick in December, 1831. I read that Mr. Hinks also had a hand in the design of the first railway carriages, pulled at first by horses, and then by the initial iron steam engine developed by Peter Cooper and named “the Tom Thumb.” Samuel Hinks is said to have worked for the B & O as a “steam engineer,” which seems to make perfect sense as his childhood home was next to the tracks, built in part by his father. He next moved to Baltimore and joined his brother, Charles Dent Hinks, in operating the firm C. D. Hinks & Company, a flour and grain dealer that had a siding connecting to the B & O. The Hinks brothers were known for their “forceful personalities,” which helped give their business in prosperity and prestige. Apparently Samuel “directed the affairs of the establishment with an ability, foresight and sagacity that stamped him as a man of high executive and business capacity. Within no time, he would become highly active in Baltimore civic causes, politics and political circles.  Baltimore Sun (Oct 20, 1842) Baltimore Sun (Oct 20, 1842) On October 17th, 1842, Samuel would marry a local Frederick girl by the name of Susan Nixdorf. They would go on to have seven children, the first, a boy named William Henry, in 1844. In 1845, Samuel Hinks became treasurer for the Relief of the Poor in Baltimore’s 12th Ward. He would eventually take up residence in the city’s 14th Ward.

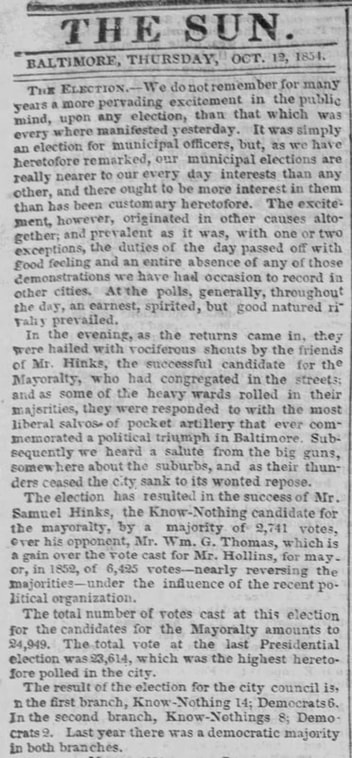

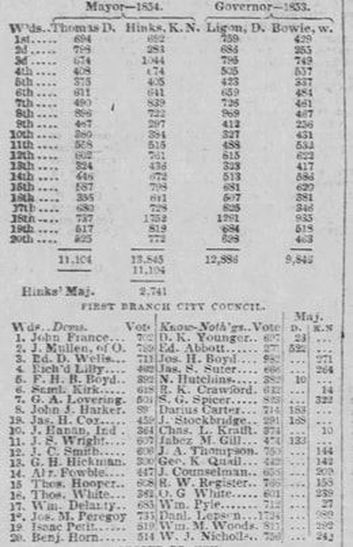

The Hinks brothers were entrenched in this group, belonging to a secret lodge. Up to this point, Samuel Hinks had never held a public office. He announced his candidacy only two weeks before the mid-October election, and followed by doing little if no campaigning. Even the convention that nominated him was held in secret. On Wednesday, October 11th, Hinks won by a margin of 2,741 votes—13,845 to 11,104 over Democratic challenger William G. Thomas. The total vote tally in this municipal election had even bested the presidential election of the previous year. Hinks’ victory came as an utter shock to the Democrats who had controlled the city for the past decade.

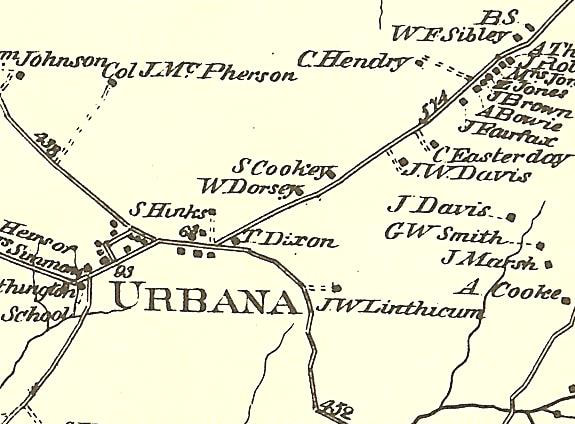

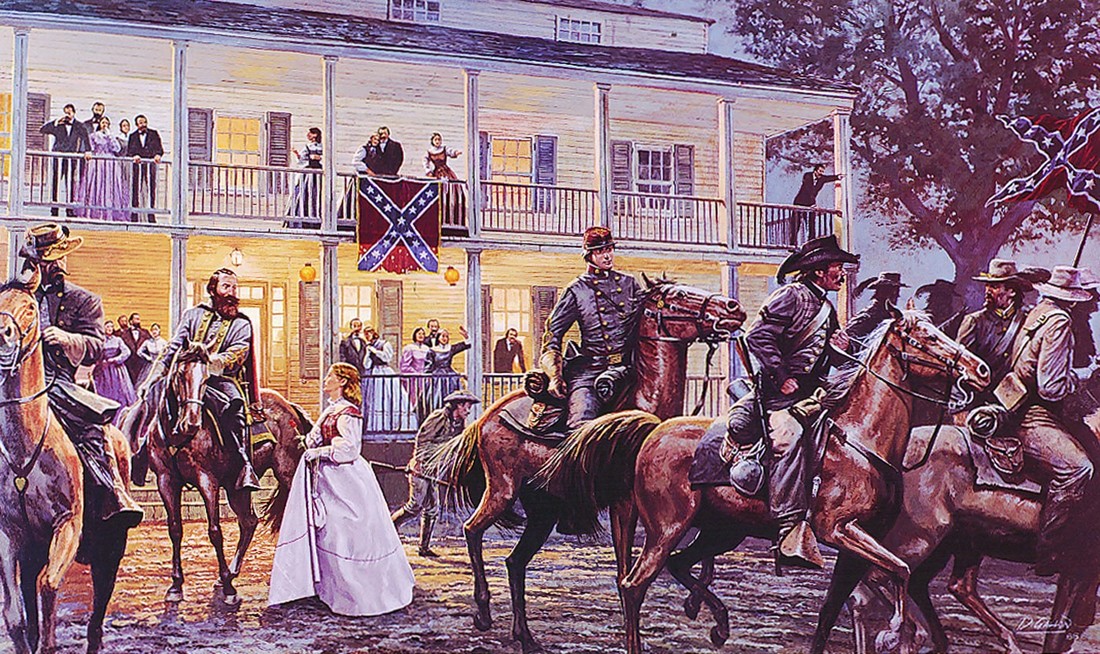

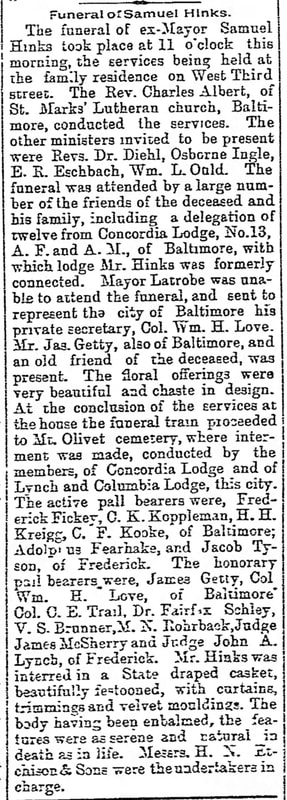

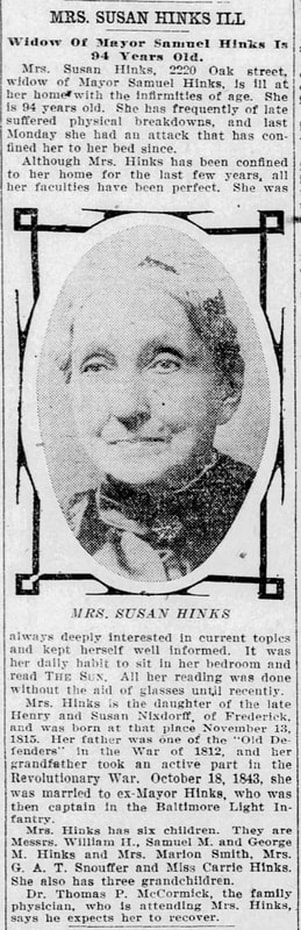

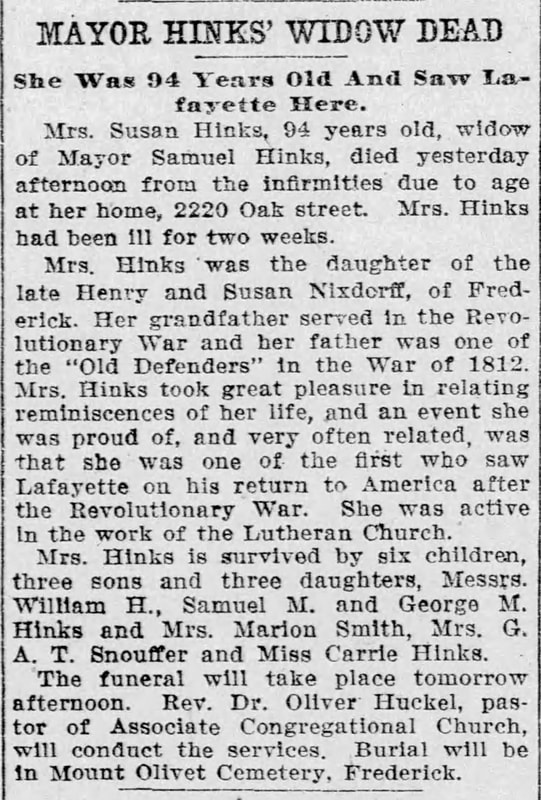

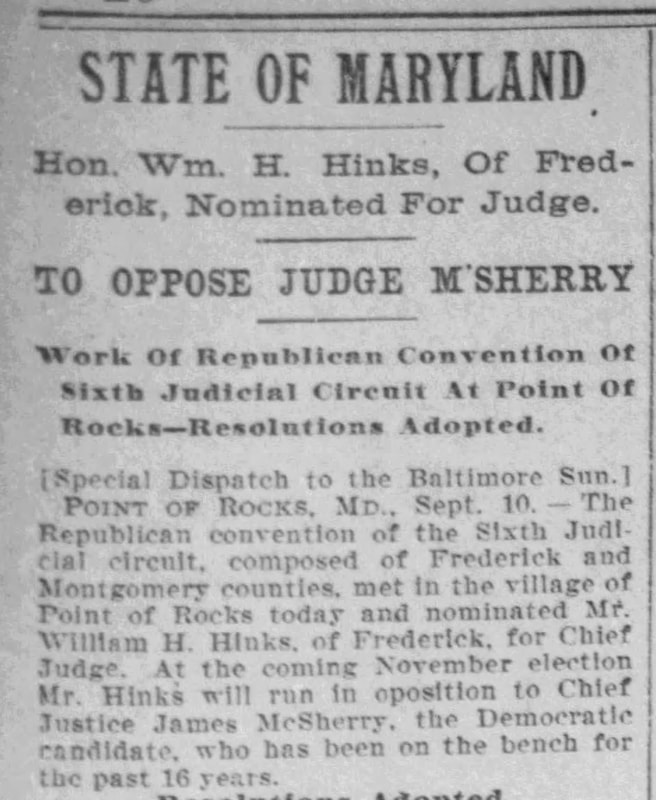

It was business as usual again for the Know Nothings. In opposition, Baltimore’s pro-slavery segment consisted of an uneasy coalition of “conservative businessmen, partisan Democrats, and beleaguered immigrant groups that had spent six years battling Know Nothing Rule.” These groups united to form the Reform party to challenge the Know Nothings in 1859. They would regain control in 1860—just in time for the Civil War. Samuel Hinks (after Baltimore mayoral term) In 1860, Samuel Hinks retired from the grain commission business and shortly thereafter was elected Water Registrar of Baltimore. In addition, he was a director of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. He even was nominated for president of the railroad, but lost convincingly to incumbent John W. Garrett. In 1863, Hinks experienced health issues, necessitating him to give up his municipal post. He also made the decision that country life would help him regain his health. He moved to Frederick County, and to the former 128-acre estate owned by Susan’s Nixdorf family, more recently known as the Dudderar Farm. Today, this comprises the Villages at Urbana subdivision. For his domicile, Samuel Hinks would purchase the neighboring Landon Academy structure (Landon House), scene of J.E.B. Stuart's Sabres and Roses Ball in September, 1862.  He settled into the role of country farmer quite nicely, far from the intricacies of Baltimore. Hinks used the opportunity to further groom his oldest son, William Henry, in the art of politics. William H. Hinks (1844-1912) had worked in the family grain business in Baltimore as a teenager, but would go on to study law at the University of Maryland, graduating in 1872. He moved to Frederick with his parents and was admitted to the Frederick Bar. William H. Hinks would gain election as a state delegate representing Frederick County to the Maryland General Assembly for two terms, 1875-79. In 1895, he was nominated to be a Republican candidate for Mayor of Frederick. Ironically, he would lose by a total of 11 votes. Shortly thereafter, he was nominated for State’s Attorney and elected. As for Samuel, he stayed active in Frederick affairs, moving to Frederick City’s West Third Street after selling his Urbana estate to Luke Tiernan Brien in 1883. He would die four years later on November 30th, 1887. Hinks obituary was featured in several newspapers around the state and many attended his funeral service at Mount Olivet, held Saturday, December 3rd. Susan would live to the ripe age of 92, joining her husband under the shadow of their fine monument on May 5th, 1909. William H. Hinks and second wife Janet Chase Hinks would also be laid to rest in Area B/Lot 21.

1 Comment

5/6/2018 09:24:06 pm

What an outstanding article! Enjoyed reading it!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed