|

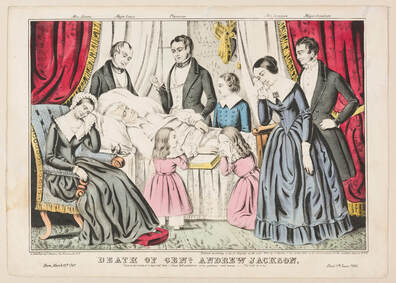

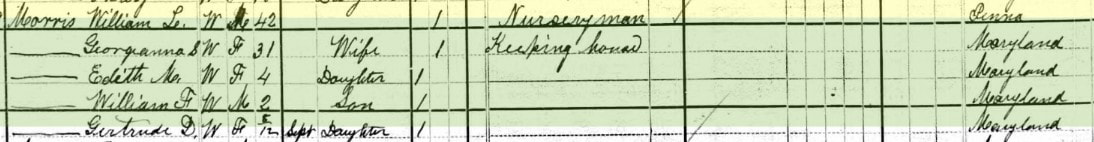

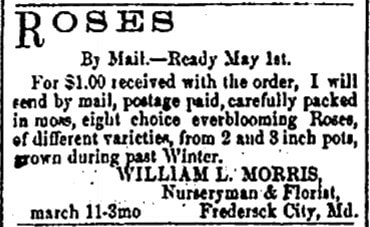

It’s Mother's Day, and the florist trade in Frederick, Maryland has been well-tested once again. Among the major recipients of florists' handiwork on this special holiday are cemeteries. For many burying grounds, such as Mount Olivet, Mother's Day is traditionally the day with the highest visitation totals each and every year. While Mother's Day includes the introduction of hundreds of new floral arrangements into the cemetery, others appear daily to commemorate birthdays and anniversaries. The most common occurrence of flowers in the cemetery however is quite obvious—funerals. Some of the most recognizable names for local flower fashions over the last century were Sharpe and Zimmerman, two family run operations that closed their doors in the last decade after “four score plus” of serving the needs of our community. Their story was told last week. We have a bit of a special mission with this week's blog as we’ll try to answer three questions: * Why are flowers synonymous with cemeteries and funerals? *Who were some of our earliest artisans in this trade? *What’s the deal with this week’s blog title?  Flowers & Funerals Flowers have always been a potent symbol for expressing many deep feelings. For both those who are gifted communicators, be it verbally or written, there’s not much of a problem. However, for others, flowers can do the talking for us. Just think about the greeting card industry as a perennial “lifesaver” as well. While flowers have long been traditionally given at many different times to help express feelings of sympathy or condolence, sending flower arrangements to a funeral have also served an ulterior motive for many centuries. Sending flowers to a funeral is not a modern custom. In fact, according to The Funeral Source, archaeologists have discovered evidence dating back to 60,000 BC of flower fragments surrounding corpses at ancient burial sites. It is unsure exactly what purpose these flowers served, but researchers hypothesize that the flowers were used in a type of burial ritual or ceremony.  In more recent history, flowers were used for their fragrance. Things get a little more delicate with this explanation as the art of embalming has certainly evolved over the centuries. In ancient times flowers were not only tokens of respect, but they were also used as a means to help cover up the unpleasant odors of decomposition. Depending on the environment, condition of the body and delay of the actual burial from the time of death, flowers were used in varying quantities to allow mourners to tolerate the smell of the dead as they grieved and paid final respects to the body before it was interred. An interesting case in point was that of our illustrious seventh US president, Andrew Jackson. The website My Funky Funeral recounts his post-mortem story: “He died at the age of 78 and by the time the funeral took place his body had begun to severely decompose. The stench from the closed coffin was so horrible that the undertaker at the time used a literal mound of flowers to cover up the entire coffin to contain it. The potent fragrance of the hundreds of flowers was just enough to overpower the stench for attendees to sit through the service. This particular act highlighted just how important flowers are for their beauty and scent.” I’ve now given you a colorful story to share the next time you pull a $20 bill out of your purse or wallet! I also learned another interesting fact involving President Jackson's funeral in that his beloved pet parrot had to be removed from the service due to incessant cursing. Aside from the practical use in covering up odors, flowers have also always served as sentimental tokens for the bereaved and by the mourning. In the Victorian era, emotions were not readily discussed or shared. Surrounding the casket with flowers served as a silent expression of emotion. This deep interconnection still survives today as flowers can convey what we can’t—the secret language of condolence that expresses everything that is too painful to speak of. They can also help create a beautiful final memory at the funeral service.  Flowers & Frederick In searching the old town newspapers, I came across the first floral experts of Frederick. One of the earliest was a gentleman named William L. Morris. He was a Civil War veteran from Lancaster, Pennsylvania who fought with Company A of the 97th Pennsylvania Regiment. Morris came to Frederick prior to 1870 and would begin advertising his services as a nurseryman and florist in the local papers in 1874. He would soon marry a local girl, Georgeanna S. Dill, whose family Dill Avenue is named. Morris appears in the 1880 census and was continuing his work with plants and flowers here in Frederick at a location on East Street across from E. 4th Street. The Morris family would re-locate to Nashville, TN by 1900. William died in 1918, and is buried in another Mount Olivet—the famed Mount Olivet Cemetery of Nashville.

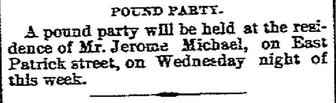

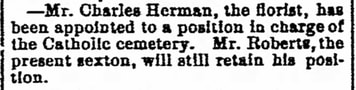

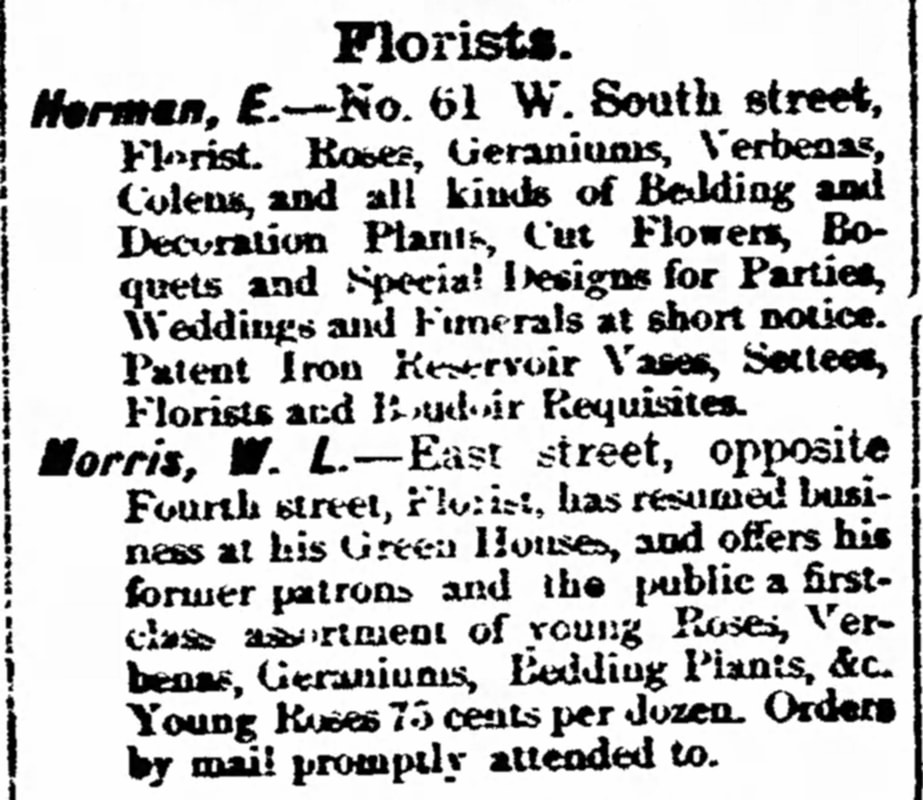

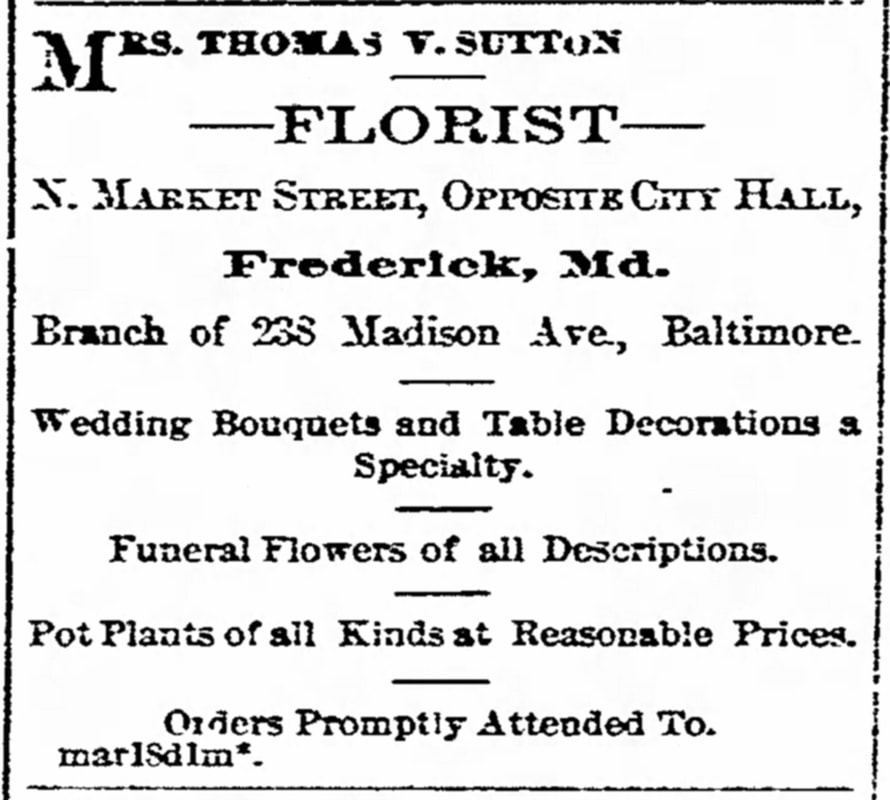

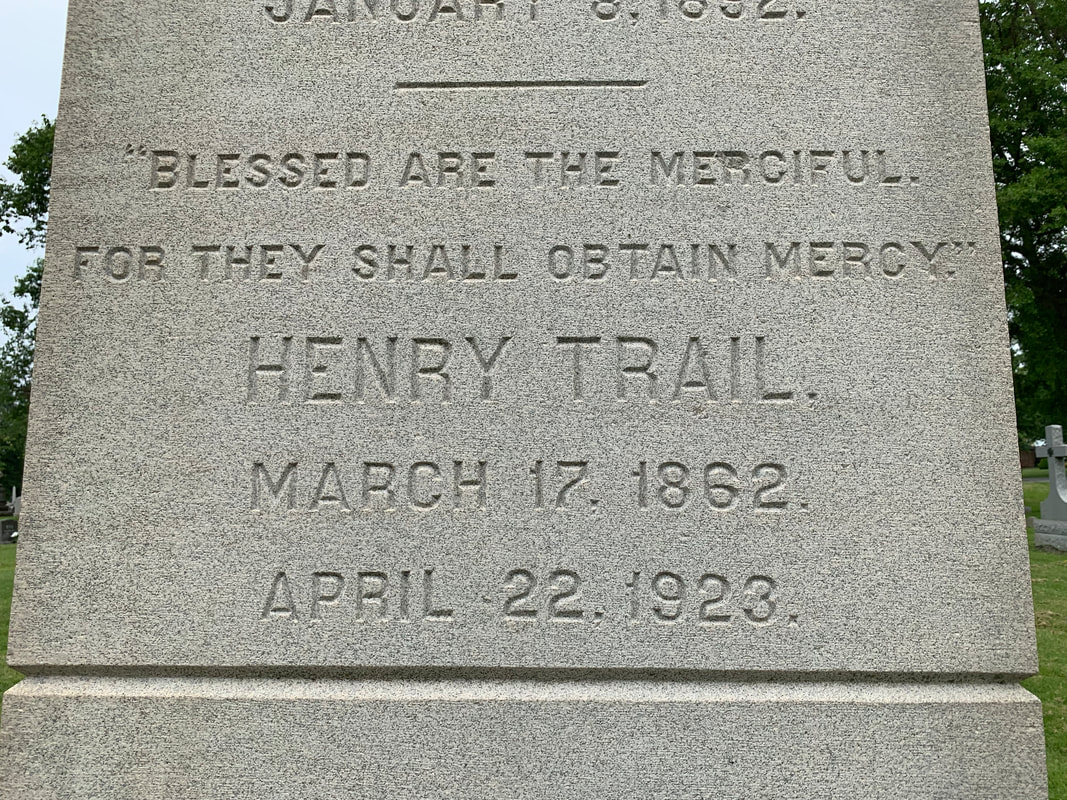

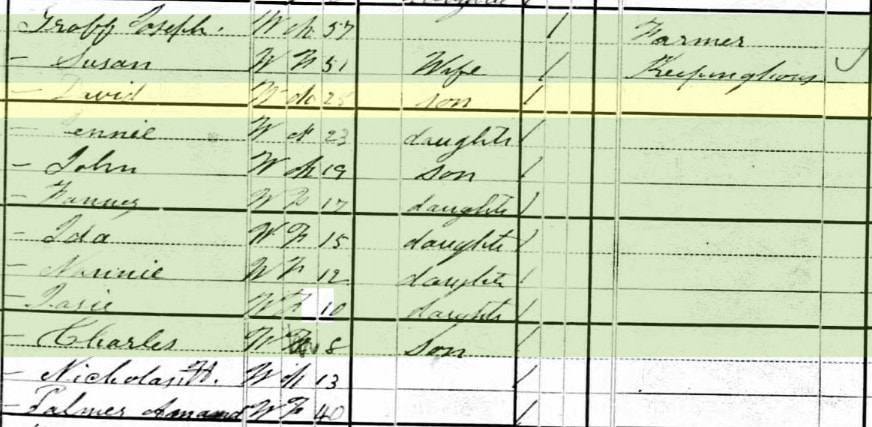

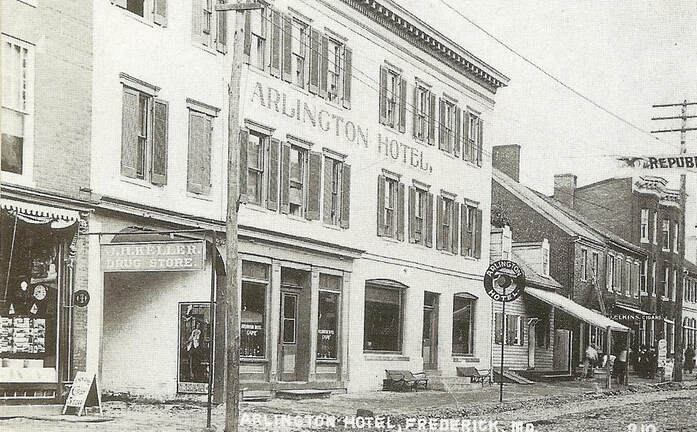

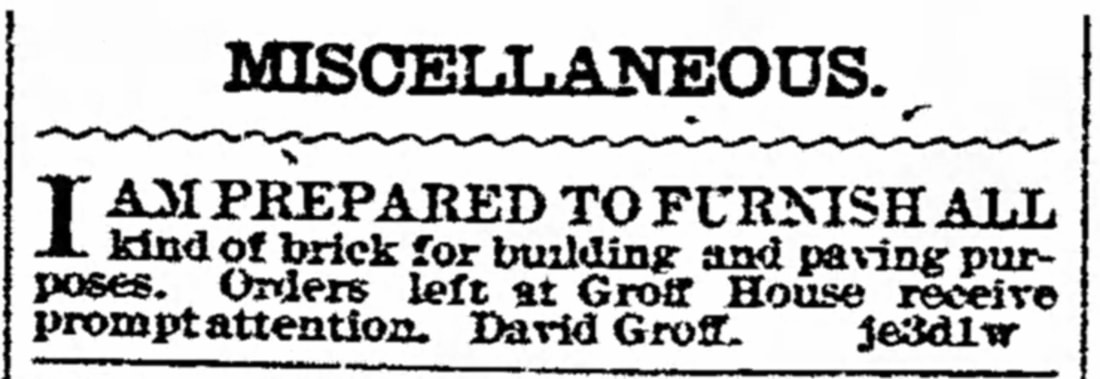

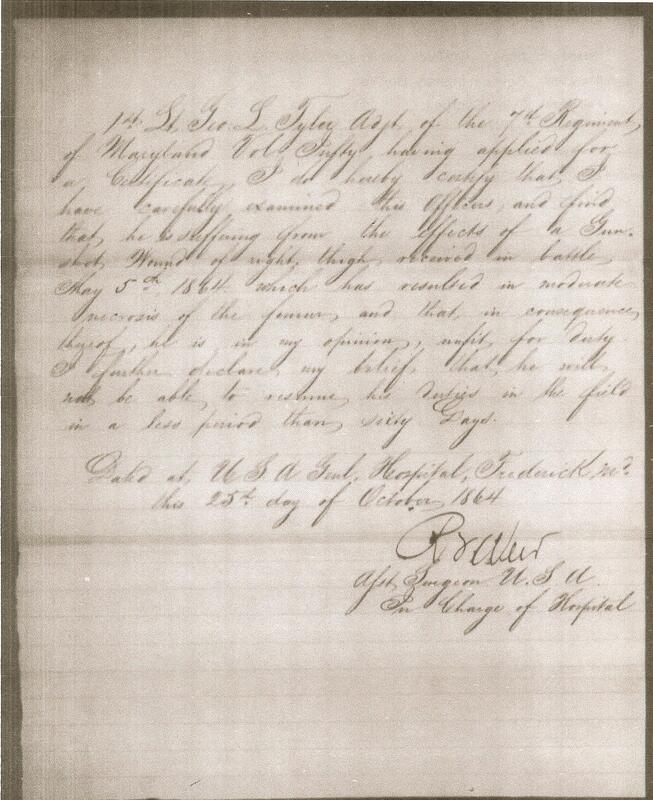

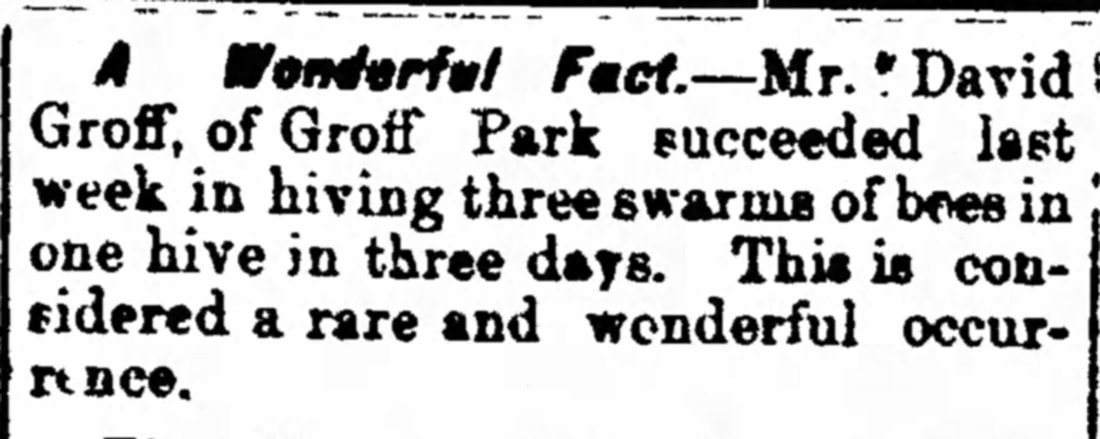

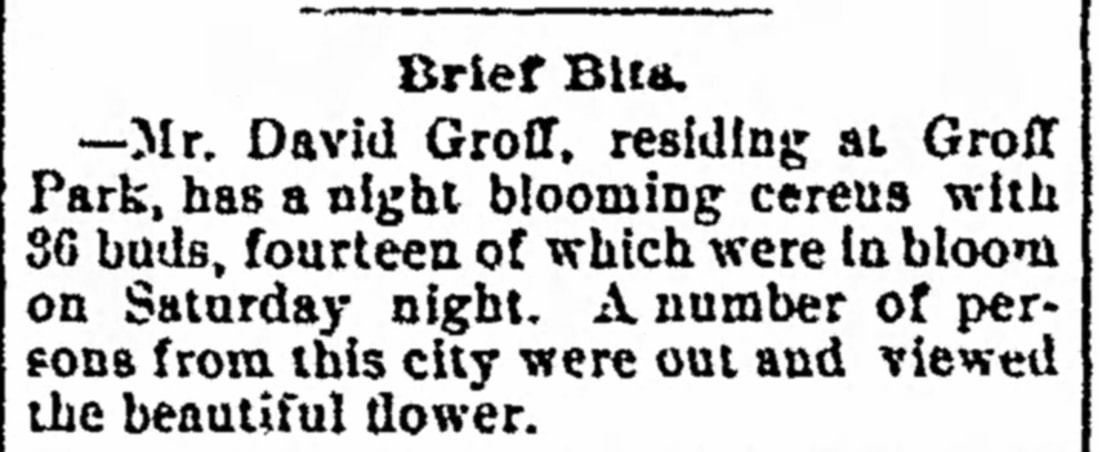

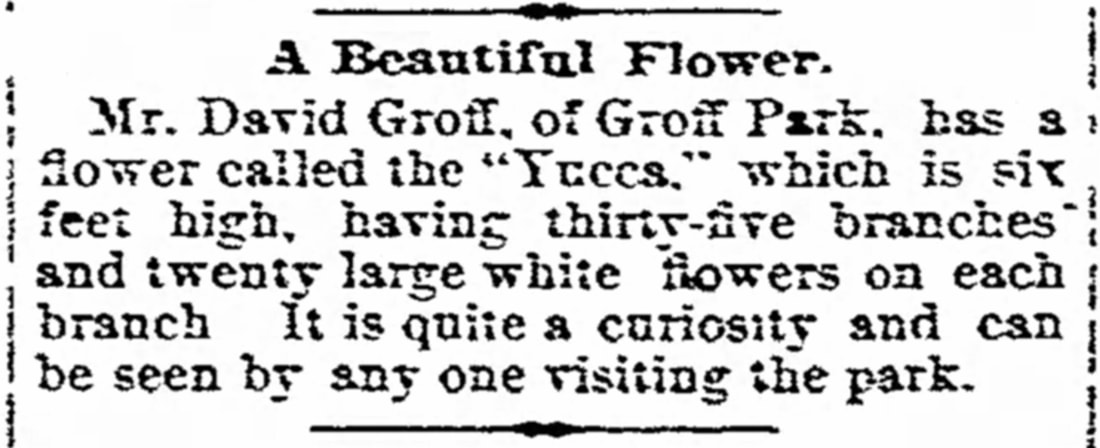

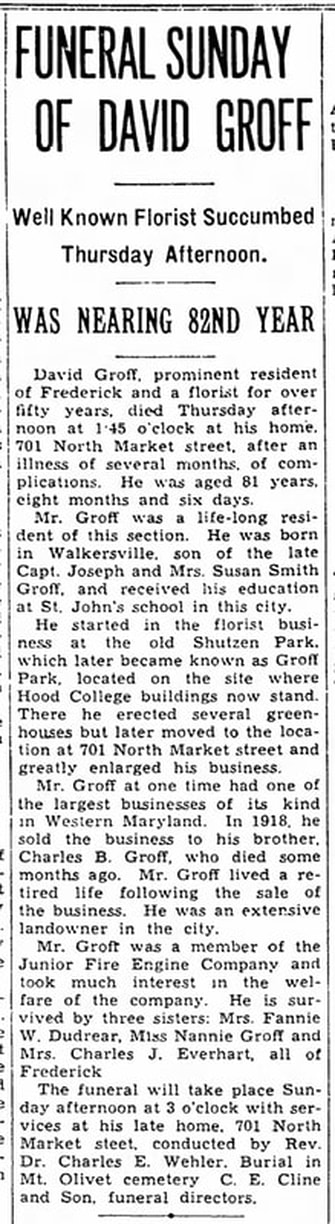

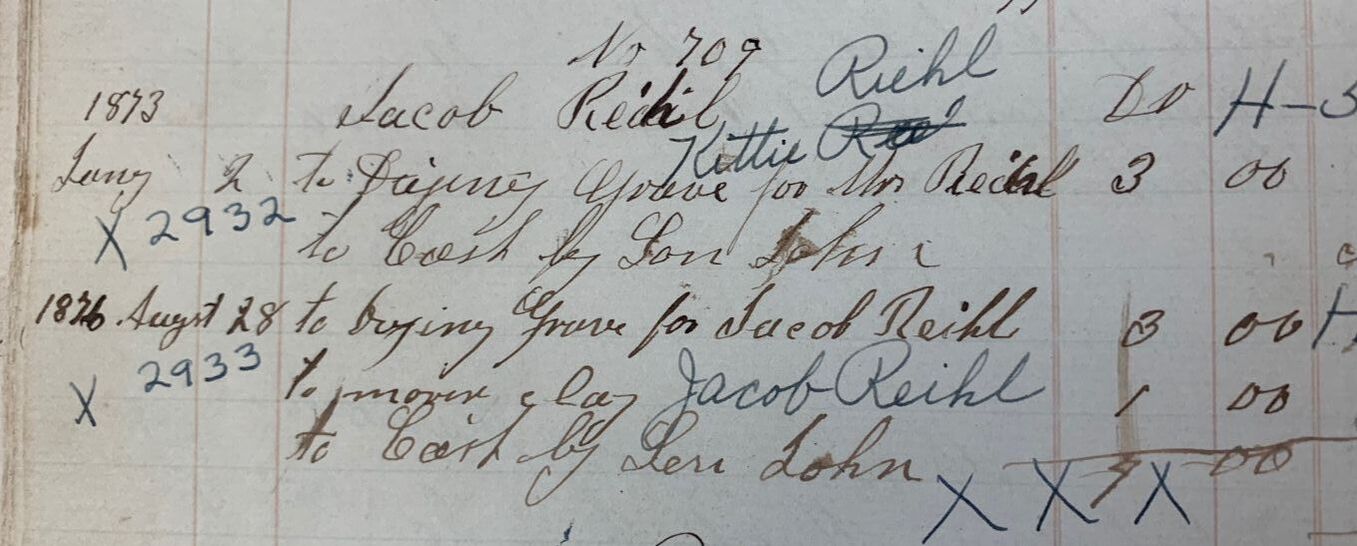

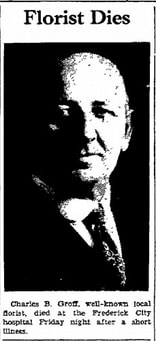

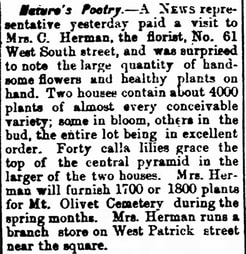

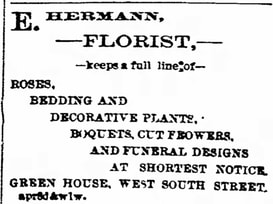

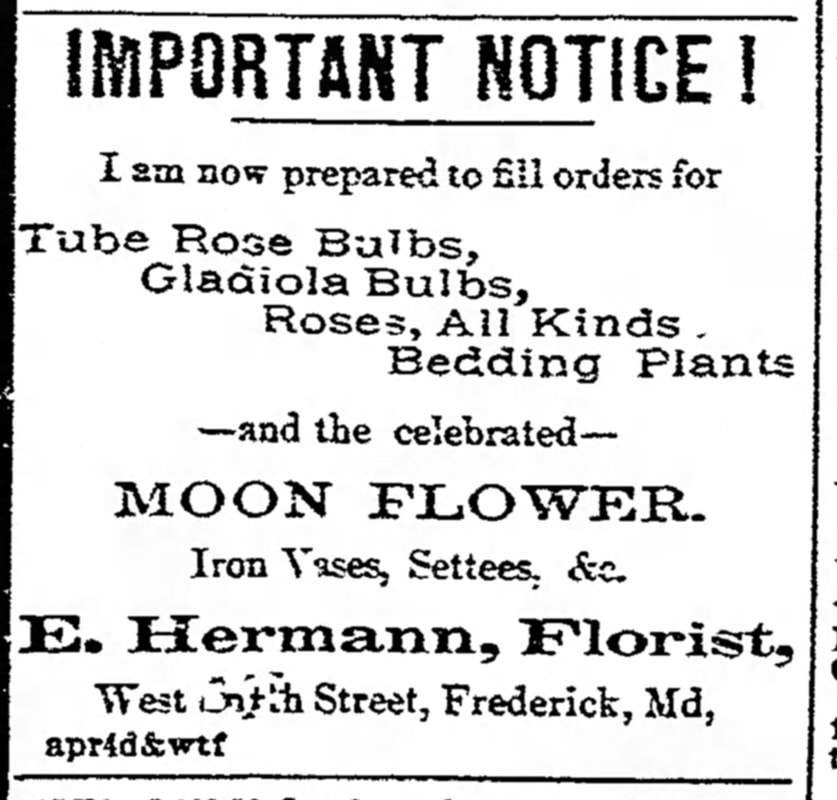

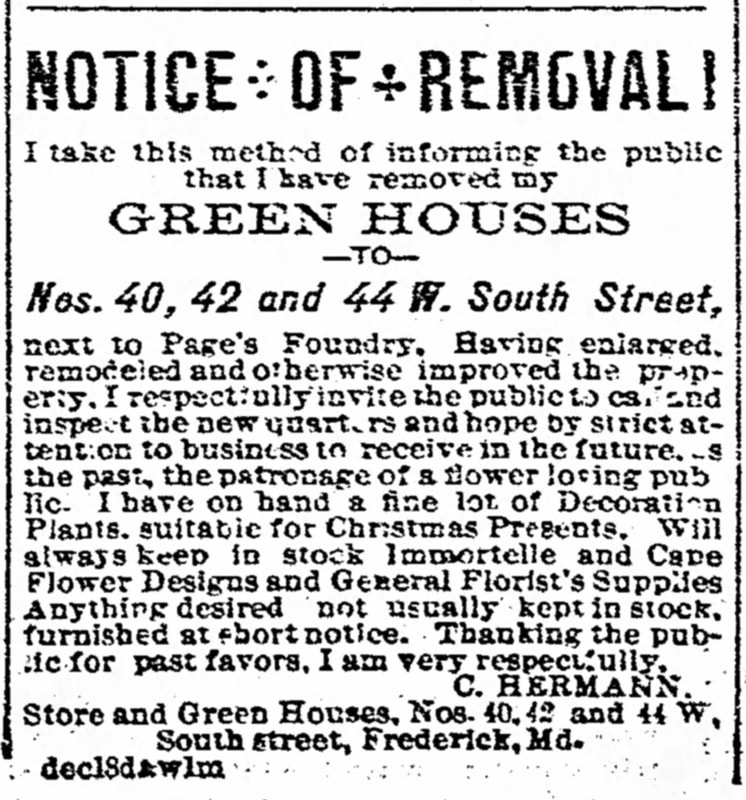

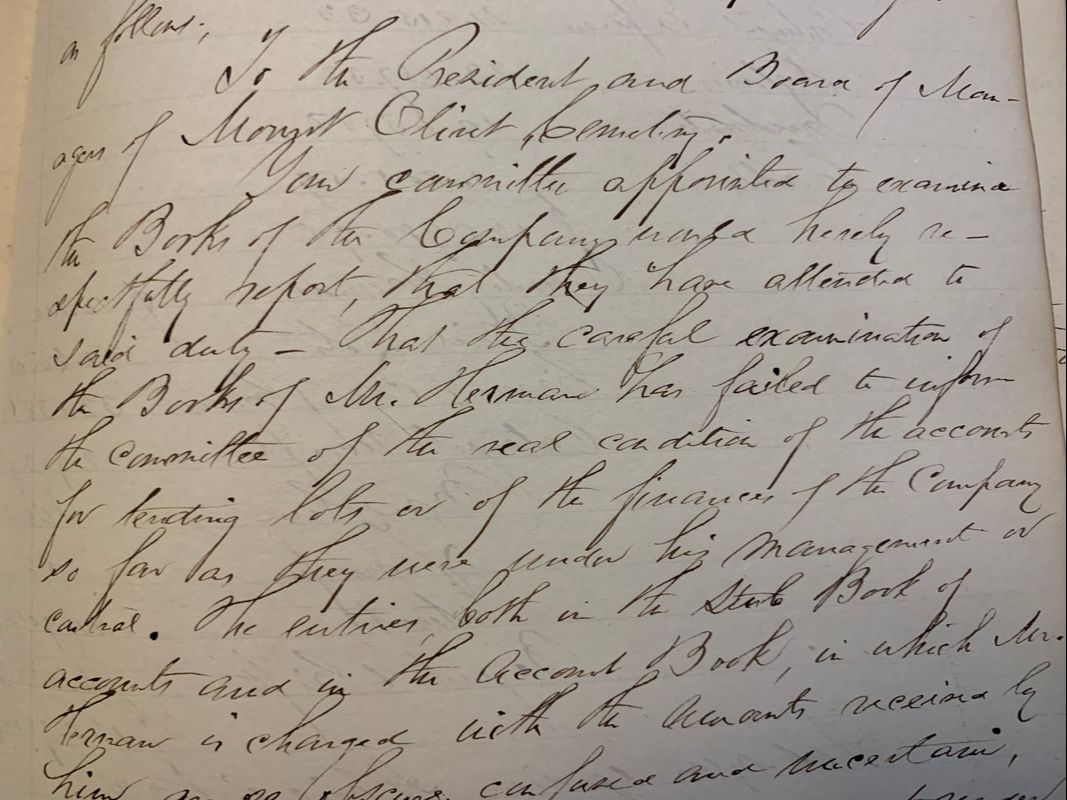

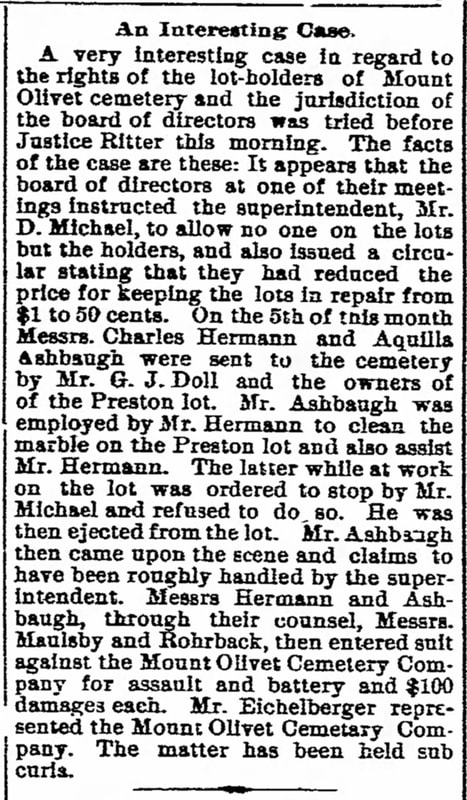

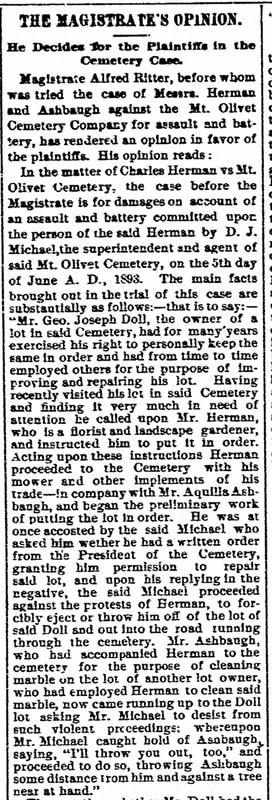

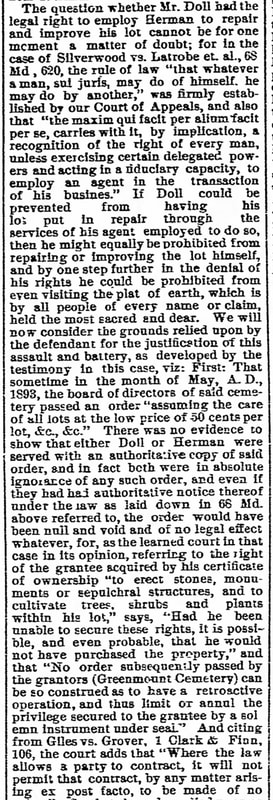

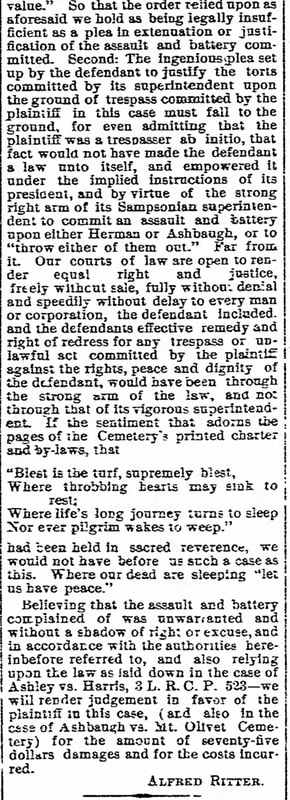

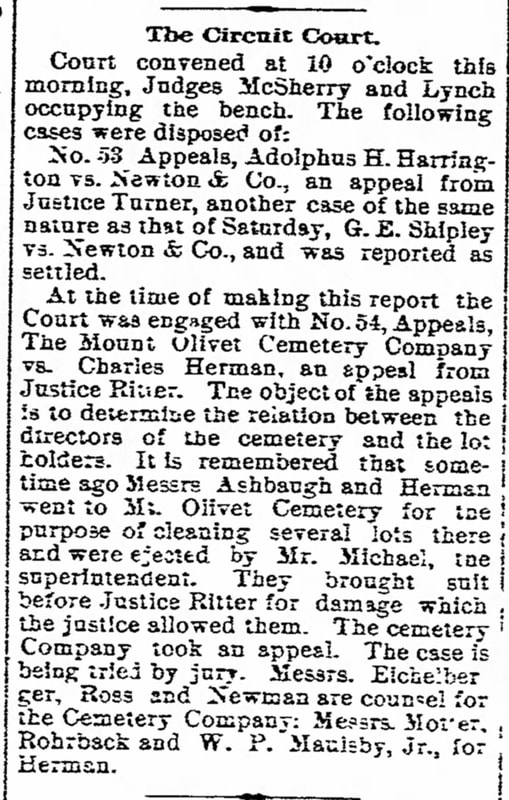

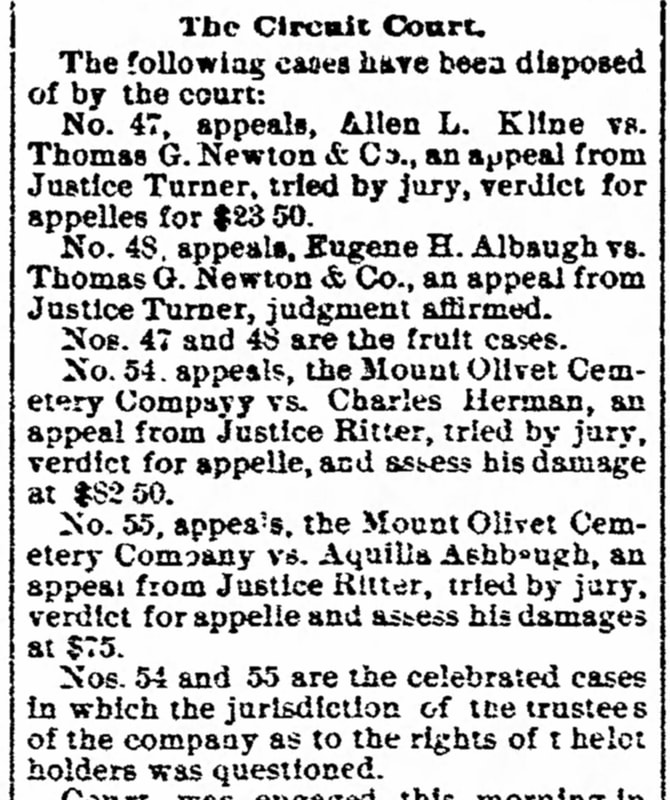

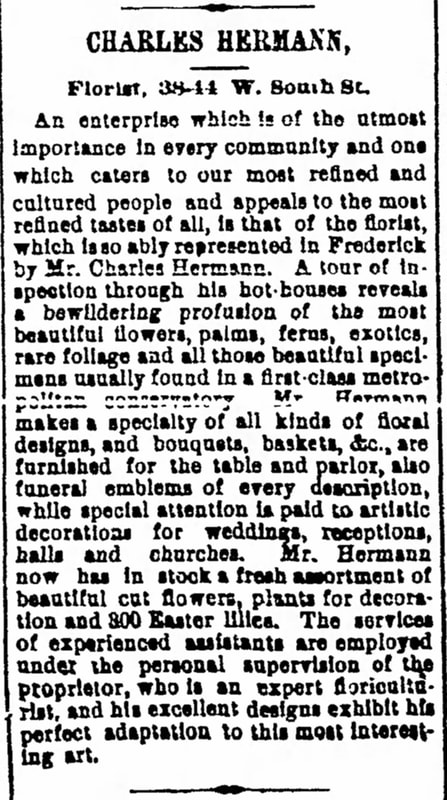

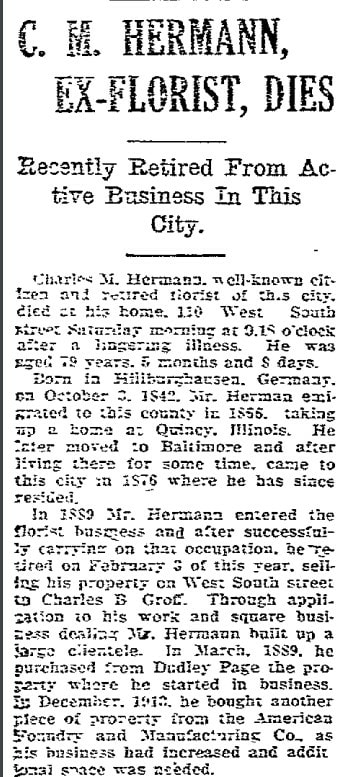

Henry Trail was the son of one of the cemetery’s founders, Col. Charles E. Trail. Col. Trail was a highly successful businessman who built the Italianate mansion on E. Church Street that today serves home to the Keeney & Basford Funeral Home. Henry was born March 17th, 1862 and lived his entire life at the Trail family mansion at 106 E. Church Street. He was a Harvard graduate who at one-time worked as a chemist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and traveled the world over his life of 61 years. Henry grew produce which would be sent to the finest restaurants of New York City and grew exotic flowers never before seen here in Frederick. This was done in “extensive greenhouses” that were erected on his father’s farm that adjoined the Frederick Fairgrounds on the east side of town. Henry Trail lived the life of a gentlemen and left the growing business of exotic plants in favor to raising exotic birds. Many Fredericktonians have heard stories of pheasants and peacocks strolling the grounds of the old Trail Mansion, at which Henry constructed a large aviary structure to be used for his hobby. He died of pneumonia on April 22nd, 1923 and is buried beneath the outstanding monument that adorns the Trail family lot on Area H/Lot 110. David Groff was born on Christmas Day, 1855 in Walkersville. His parents are known in the annals of Frederick history as prominent hoteliers and local heroes of the Civil War. Joseph and Susan Groff ran the Arlington House, located on N. Market Street during the turbulent era of the 1860’s. David’s father was a shrewd businessman who also ran a brickyard and dabbled in real estate acquisition. One such property was the site of a former German social club called Scheutzen Park. The site would come to be known as Groff Park and the former social group’s main club house would become the family’s new personal residence. In the next century, Groff Park would become the new site of the Frederick Woman’s College, renamed Hood College. David Groff’s childhood home was none other than Brodbeck Hall, the central facility associated with Hood College’s music department. Groff Park and Brodbeck would serve as the family residence until 1894, at which time they re-located to another stately dwelling at the intersection of 7th and N. Market Street. Here they would open a new hotel by the name of the Groff House. This location would later serve as the home of WFMD. David attended St. John’s School and began taking a keen interest in growing things from a young age. Groff Park was his showplace, and he would turn a hobby into a profitable profession. It was here (in Groff Park) where the family grew extensive gardens in which they harvested produce and flowers for their hotel guests. Greenhouses were built here for the express purpose. Locals were invited to see David’s handiwork as the location became known as somewhat of a “poor man’s” botanical garden—one that preceded Baker Park by nearly 50 years as a scenic destination for picnicking, leisurely strolls and carriage rides. The park would become a prime location for “drives” with the advent of the automobile in the 1890’s. The 1873 Titus Atlas of Frederick illustrates the lanes within Groff Park, and I assume that they were paved as the family-owned brickyard specialized its marketing efforts on advertising pavers for streets, alleys and driveways. David’s job was to run this family business, which was anchored in the 700 block of N. Market Street not far from the Groff House Hotel which was originally constructed by Captain Groff in 1884. David seems to have extended his floral hobby to competitions in the early 1890’s and was a prominent member of the Frederick Floriculture Club. He is mentioned in a newspaper article in November 1892 which talks about the Chrysanthemum Show in which he entered 20 varieties of the flower. Articles regularly appeared in the local newspaper boasting David Groff’s floral artistry and special growing experiments. When the family left Groff Park around 1897, David took charge of selling off properties for building lots on the eastern edge closer to town. He took up residence at 701 N. Market Street adjacent the family-run hotel. He would build greenhouses here that would help supply a florist business ran out of his new residence.  Charles B. Groff (c. 1889) Charles B. Groff (c. 1889) The florist operation of David Groff thrived and became his life’s work as he never married or would have children. David would run the business until early 1916, at which time the reins were handed to his younger brother Charles Benjamin Groff (b. 1873). The younger Groff had worked as a county clerk but assisted David for years. He, too, would make his mark as well on the community over the next 18 years until his death in December, 1936. An article appearing in the April 5th, 1917 edition of the Weekly Journal of Florists, Seedsmen and Nurserymen contained a small mention of the Groff-run business: “A grower whose long suit is performance and who has a reputation as a teetotaler, will find a good market for his services if he happens down Frederickway and stops in at Charles B. Groff’s stand where everything is grown, and grown well.” David Groff never stopped growing things. He devoted his time to selling family-owned land, newly constructed homes and renting apartments within the old Groff House (after the hotel closed as a business). In 1927, he ran advertisements for things such as potted tomato plants and celery. He died nine months after his brother at the age of 81 (August 26, 1937). His passing, and subsequent funeral were the source for a few nice articles that appeared on the pages of the Frederick News-Post. Of special notes was the fact that “floral offerings were beautiful and numerous.” One of his pallbearers was Alfred G. Zimmerman (1891-1961), the progenitor of Zimmerman Florists. David Groff is buried next to his parents in Area L/Lot 247. His kid brother can be found in Area Q/Lot 127. Not that far from the gravesite of Charles B. Groff is buried a true early giant in the field of Frederick floristry—Charles Hermann. He even became known as “Hermann, the Florist,” a slogan that can be found in several old news articles and advertisements. Charles Maximilian Hermann was a German transplant to Frederick who earned the nickname of “Hermann the Florist” by the mid 1880’s. Actually, I found that a good deal of this gentleman’s success should be given to his wife, Elizabeth (Diehl) Hermann. Evidence comes in the form of a news article that appeared in the Frederick News in mid-December 1883. I saw ads referencing Mrs. Hermann and her business and greenhouse located at 61 W. South Street in Frederick up through mid-1888. She is said to have had a branch office located on W. Patrick near the Square Corner and in 1885 was preparing to furnish Mount Olivet with 1700-1800 plants. In December of that year, her husband Charles announced that the Hermann floral business had moved to a new home down the street from their home and next to the old Page agricultural implements foundry that sat on the SW corner of the intersection of W. South and Broadway Street. Back in the day, Broadway Street was called Mantz Street and the Page foundry location is the home of the Gary L. Rollins Funeral home with an address of 110 W. South Street. Whether by design or accident, Mr. Hermann shared his talents with Mount Olivet Cemetery in more ways than a flower vendor. On March 16th, 1887, he was given the title of assistant superintendent of the cemetery, the first time such a position would exist after 33 years of operation as a burying ground. I searched to see if Hermann had been working for the cemetery in any other capacity before this date, but came up unsuccessful. So I deem it a case of “chicken or the egg.” Was Hermann hired for his special expertise in gardening and floral creation, or did he hone his skills here at the cemetery, which in turn, would benefit the business apparently started by his wife, Elizabeth? Interestingly, Mr. Hermann’s immediate supervisor, Edward Herwig, started in his position on March 16th, 1887—the same day Hermann began his duties as assistant super. Herwig was filling big shoes, as he would be the second superintendent ever chosen for the position, following inaugural cemetery head William T. Duvall who served from February 6th, 1854 until the day of his death on September 19th, 1886. Regardless, things seem to have “taken bloom” for the Hermann family business here in Frederick, perhaps tied to an increase in orders connected to Mount Olivet Cemetery. Was this a case of “double-dipping?” And I’m certainly not talking about ice-cream. As said, everything was coming up roses for Charles B. Hermann until one fateful day in early November, 1892. A special meeting of the cemetery board of directors had been called with the death of Board President Lycurgus Hedges. At this meeting, the Board secretary, Thomas M. Markell, was instructed to notify Superintendent Herwig that “his service would be disposed with after the first day of January next.” This was roughly a 8-week notice, and the board subsequently authorized interim president Lewis C. Clingan to find a new man to take Herwig’s place. Charles Hermann was not even considered for the job, but there was good reason as he could been a prime reason for Herwig’s downfall. The accounting associated with the cemetery’s books was in question as things weren’t quite matching up—floral and shrubbery expenses were way up.  Frederick News (Dec 6, 1892) Frederick News (Dec 6, 1892) Just over a week later, Mr. D. Jerome Michael was unanimously elected to become the cemetery’s third superintendent, a position he would hold for the next 14 years. In conducting research, I was more than pleased to find a celebration of sorts held at the Michael residence a few week’s after being awarded his new post at the cemetery. This would certainly not be the last “pound” party that Superintendent Michael would take part in.  Mr. Michael assisted the Board of Directors with research into the accounting and management issues discovered under the Herwig regime. Apparently, the trouble came under the purview of Mr. Hermann in the daily performance of his duties as assistant superintendent. It came as no surprise that Mr. Hermann was given the proverbial “pink slip” on January 1st, as his service was promptly disposed with as well. Superintendent Michael, the new sheriff in town so to speak, continued his research over the winter months. The Board of Directors reconvened for their annual meeting in early May, 1893. A special committee would be appointed by the Board to explore the cemetery books more in depth with a goal of “placing things in a satisfactory and intelligible shape.” Assistance would come from the Board’s secretary and treasurer as well. On May 22nd, a special meeting was called in which Board member Mr. Charles M. Tyson presented a report on the special committee’s finding. the following passage comes from the Mount Olivet Minute Book records: May 22, 1893 report To the President and Board of Managers of Mount Olivet Cemetery: Your Committee appointed to examine the books of the Company would hereby respectfully report that they have attended the said duty that the careful examination of the Books of Mr. Hermann has failed to inform the Committee of the real condition of the accounts for tending lots or of the finances of the Company so far as they were under his management or control. The entries, both in the Book of accounts and in the Account Book, in which Mr. Hermann is charged with the amounts received by him, are so obscure, confused and uncertain and the calculations so inaccurate, as to render it impossible to say what the status of this department. What was happening in the cemetery, behind the scenes, had been brought to light by the new superintendent and likely corroborated by existing grounds employees—Charles Hermann was not only using his personal business as a major vendor for the cemetery (for plants, shrubs and flowers), he was likely recommending his personal business services to lot-holders over the capable individuals on the Mount Olivet payroll. He was poaching customers for personal gain—a clear-cut case of conflict of interest. At another Board of Managers meeting, held May 31st, 1893, Mr. Edward S. Eichelberger made a pivotal motion. Eichelberger was one of the three Board members assigned to the special committee of inquest into the matter. His motion ordered that “no one other than Employees of the Company be allowed to take care of Lots, unless he files with the Superintendent of the Cemetery, a separate written authority from each lot holder of whose lots he is to have charge, which authority shall be countersigned by the President of the Company and which shall be kept by the Superintendent, as a defense against any complaint of the lot holders for any alleged neglect. “ Mr. Eichelberger went on to add that “the President be instructed to obtain a list of those persons whose lots have been placed in Mr. Hermann’s charge, and notify them of the above order, and correct any misapprehension as to the facts in regard to the lots, and the Secretary is instructed to send a written copy of the above order to Mr. Herman. It appears that Mr. Hermann had decided to continue accommodating “his” lot-holding friends and cronies by providing special services to them and their respective lots in the spring after his termination. The Board was not amused. They also understood the ramifications that they would be liable for the conduct, or better—misconduct or “neglect” of an outside vendor performing work in their cemetery—especially work they were plenty capable of doing themselves with their own staff. Well, just five days later, let’s just say that the “flowers” hit the fan so to speak. Mr. Hermann and a hired hand named Aquilla Ashbaugh came to Mount Olivet to perform work on lots, contrary to the recent order set forth and communicated by the Board of Managers. These lots belonged to local department store owner Joseph Doll (1829-1895), and another owned by the hiers/family of William T. Preston (1811-1879). Our minutes book say nothing of the incident that occurred on this day, however a vivid depiction of events was printed in the Frederick newspaper two weeks later as part of a court case that went before local magistrate Alfred Ritter. The case can be seen from two different vantage points. First and foremost was the obvious “assault and battery” on Hermann and Ashbaugh as Superintendent Michael decided to host another “Pound” party on June 5th as he threatened (and succeeded somewhat) in pummeling his adversaries. The other part centered on cemetery lot-holder rights vs the cemetery corporation’s authority and responsibilities of operating a cemetery. Judge Ritter ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, but simply looked at the case from the perspective of the unjustified act of assault and battery on these gentlemen at the hands of Superintendent Michael. Each plaintiff was awarded $75 and their court costs were paid by Mount Olivet. (For your reading pleasure, I have included below the full verdict as reported in the newspaper) It didn’t end there, as the case would be appealed by the cemetery. In late August, 1893, a jury listened to the facts of the case and ruled in favor of the cemetery. The end result was a study into the ultimate responsibilities of the Cemetery Board, and their standing as being nominated and duly elected to represent the mass congregate of active lot-holders. The jury found the cemetery “not guilty” of wrongdoing, and rewarded them back $82.50 in both cases (involving both men—Hermann and Ashbaugh).  Frederick News (June 12, 1893) Frederick News (June 12, 1893) The Hermann-Michael "Battle Royale of 1893" solidified a rule that still stands today under Article 31 of our official Mount Olivet booklet of rules and regulations published by the cemetery: “No one other than employees of the cemetery will be allowed to take care of lots, including but not limited to the mowing, trimming and watering of grass on their lots.” While Charles Hermann lost $75, court costs, and future earning potential with personal lot renovation work, it is important to know that he kept working. As a matter of fact, he would continue to have success in the floral business and would be appointed overseer of St. John’s Catholic Burying Ground off E. 3rd and N. East Street in June, 1893. Hermann would grow the business with the guidance of Elisabeth and help of his son (Charles) who he brought into the business. Charles eventually sold the family business upon his retirement in February, 1922. This would go to friend and fellow florist Charles B. Groff, brother of David Groff, whom we discussed earlier. Charles M. Hermann died on March 11th, 1922. He would be buried on a corner lot in Area H, directly across from Confederate Row. Wife Elizabeth, the unsung and original floral artist of the couple, died in 1941 at the age of 95. Hermann’s faithful sidekick, Aquilla Ashbaugh, is also buried in Mount Olivet with his wife Minnie. In finding his obituary, I was surprised to find that Mr. Ashbaugh was a former employee of the cemetery. This means that he left with Hermann when the latter was fired in January, 1893. Sadly, the Ashbaugh gravesite is devoid of an identifying marker or monument (Area B/Lot44). Must have been confusing for friends and relatives to find his grave in order to place flowers... “In joy or sadness, flowers are our constant friends”

-Okakura Kakuzo

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed