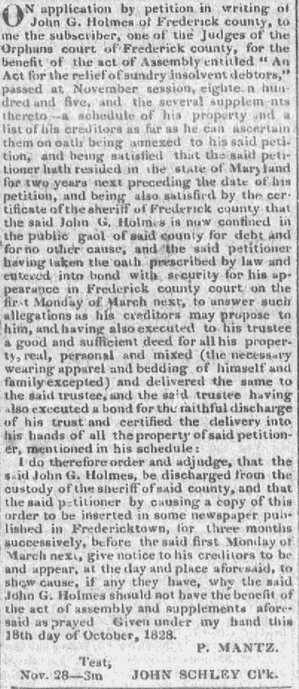

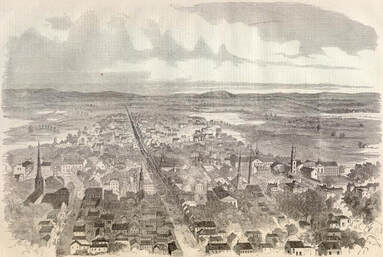

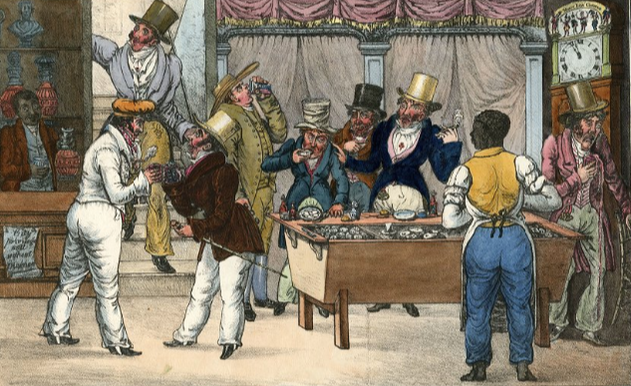

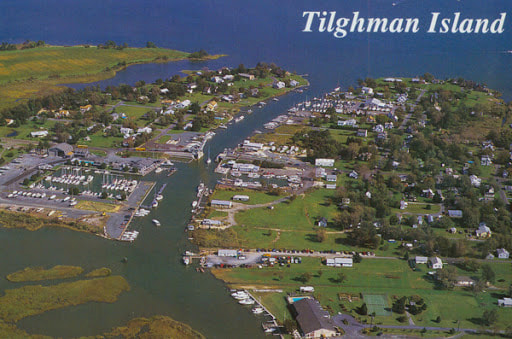

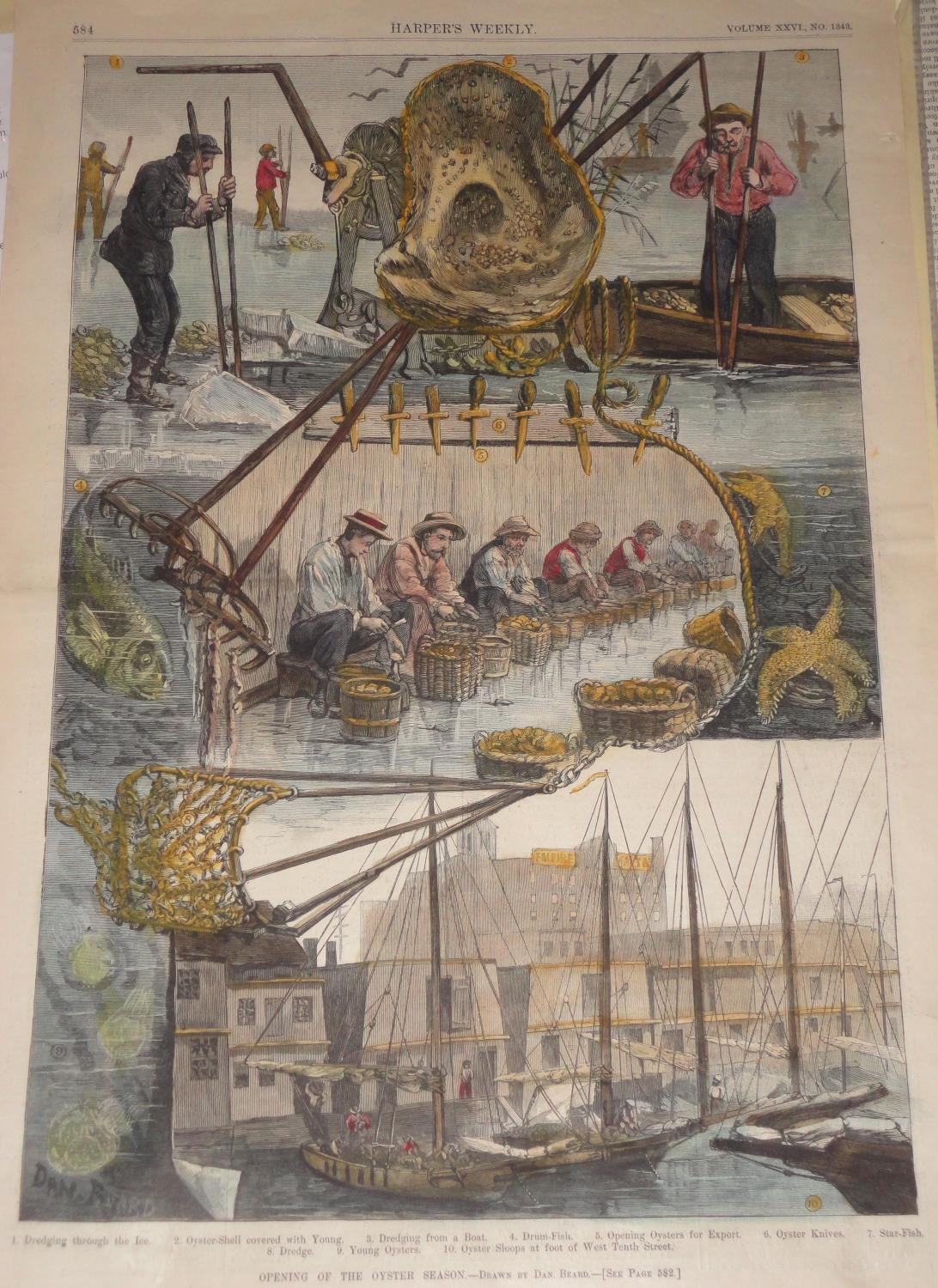

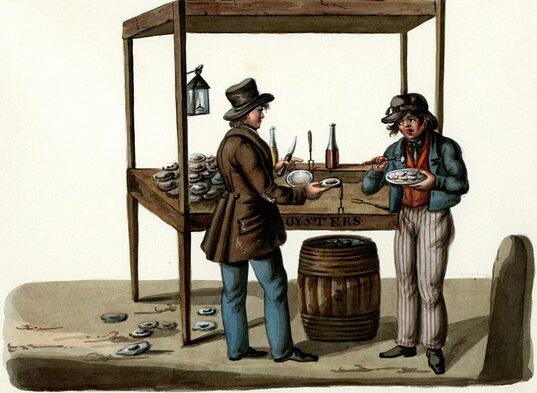

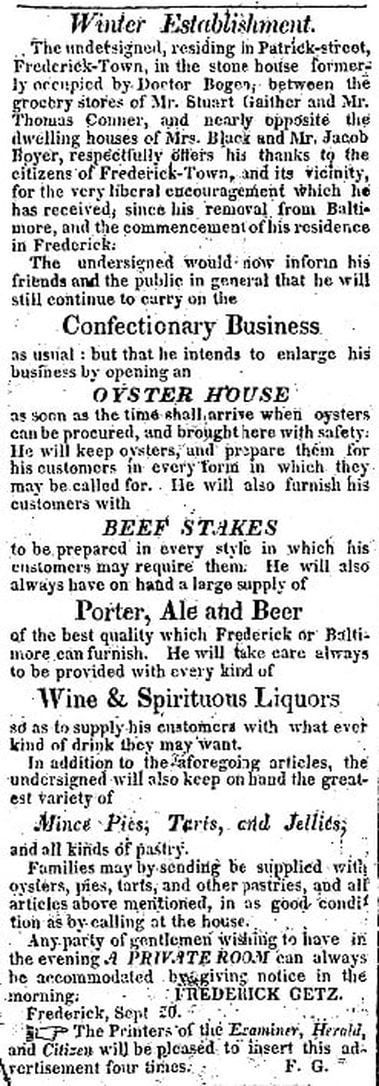

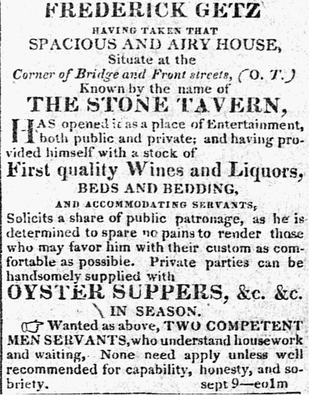

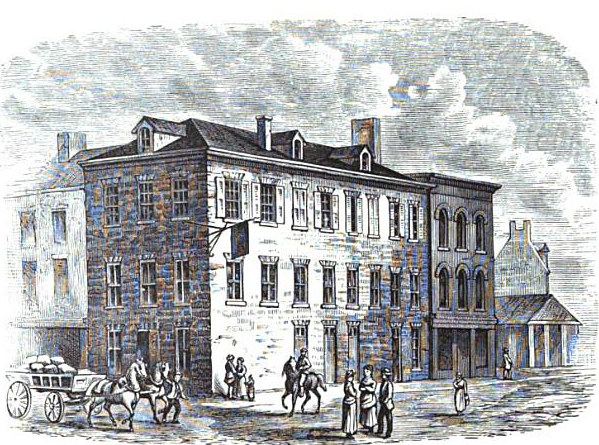

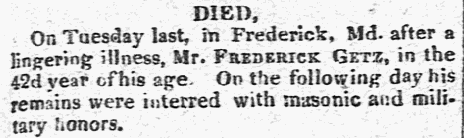

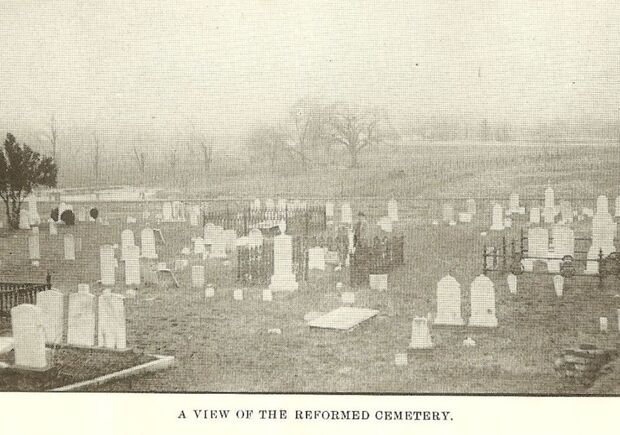

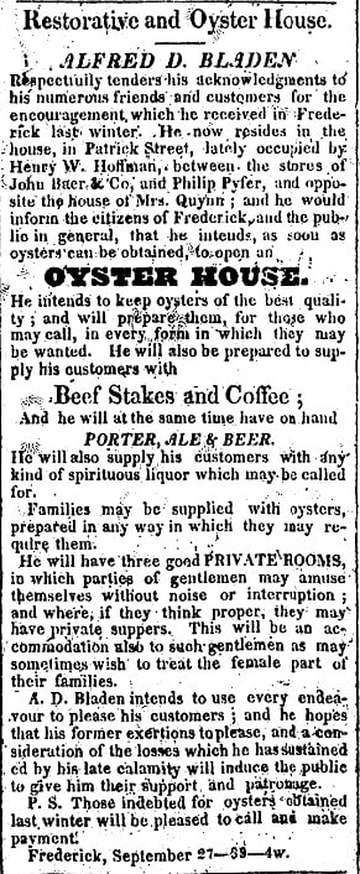

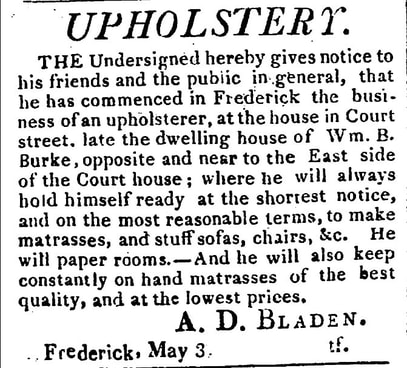

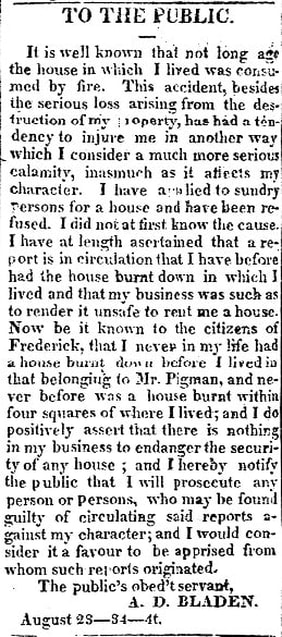

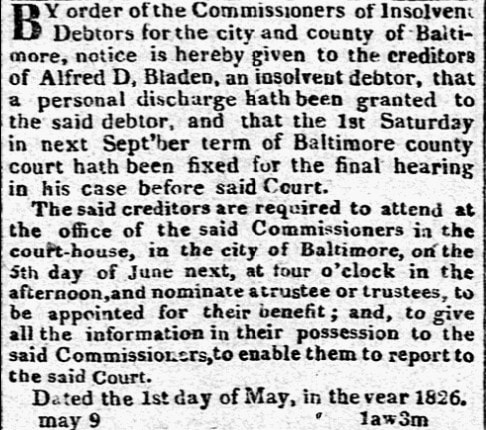

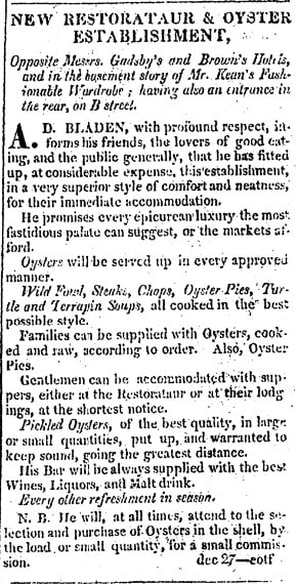

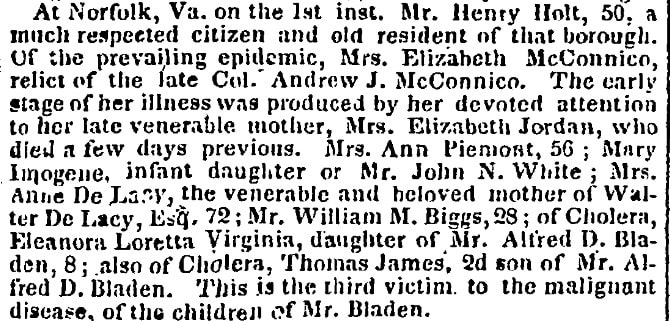

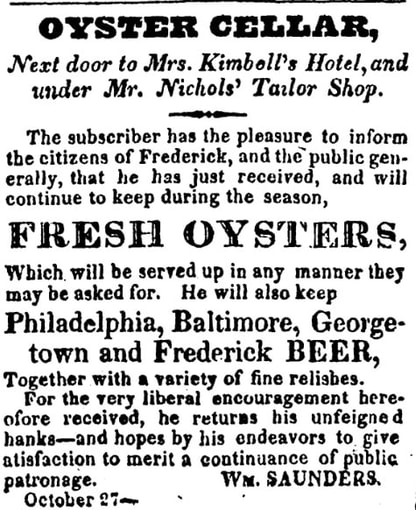

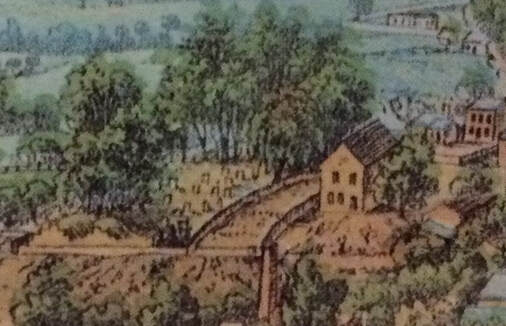

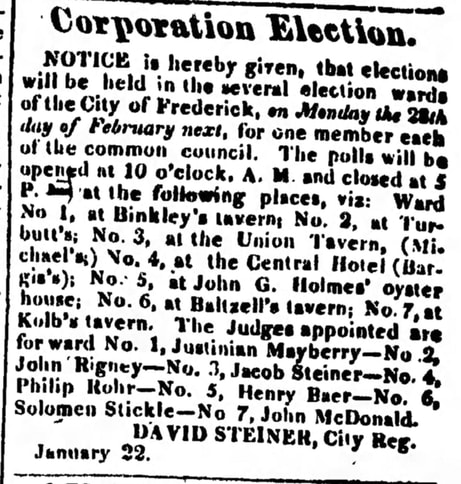

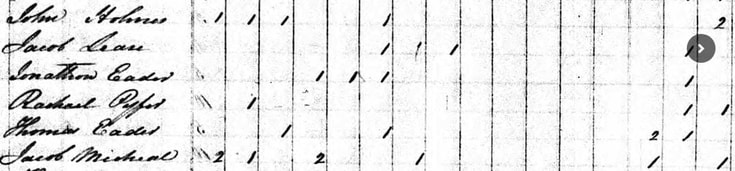

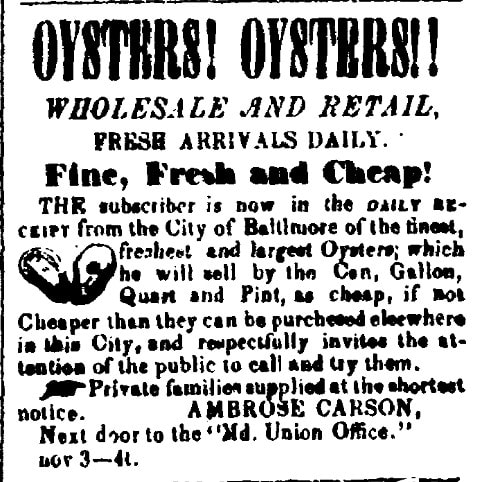

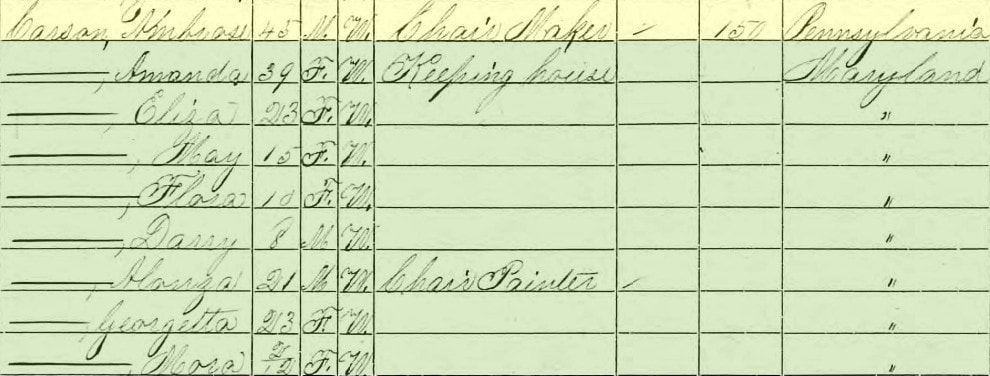

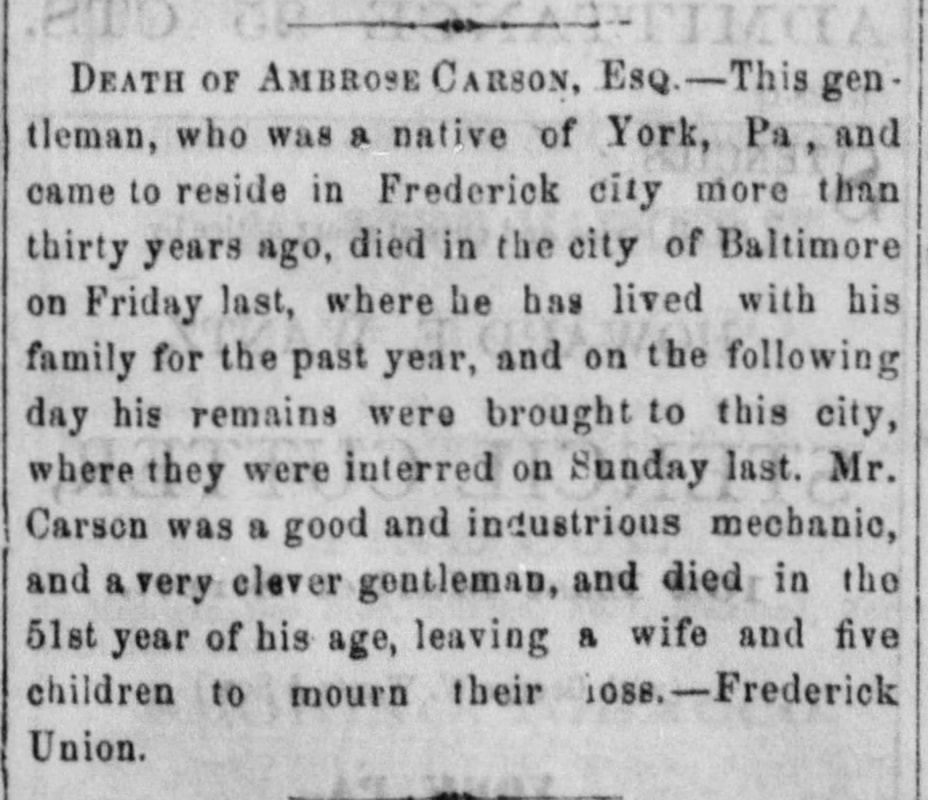

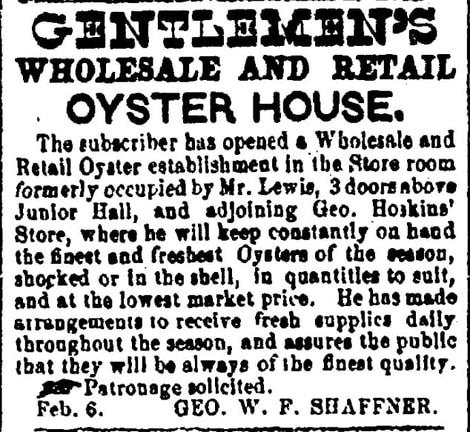

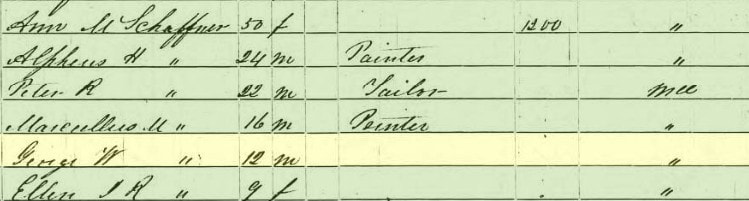

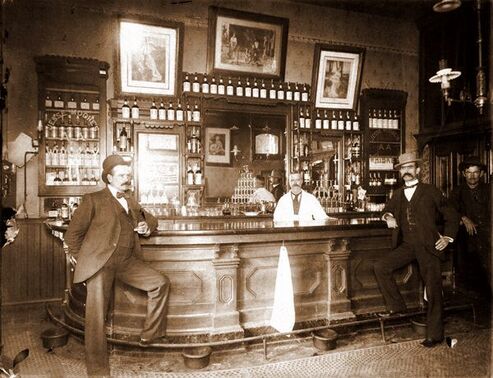

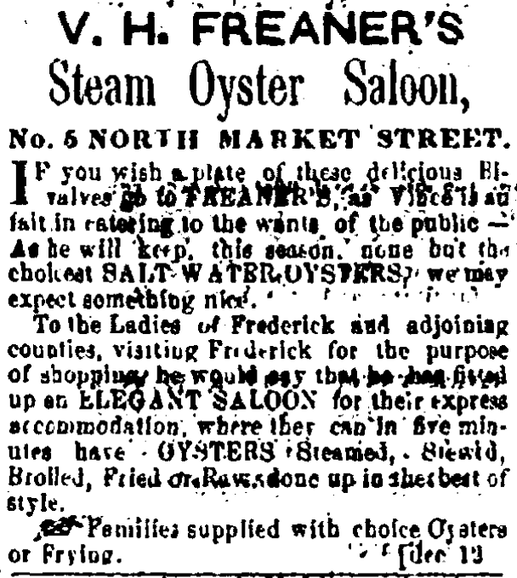

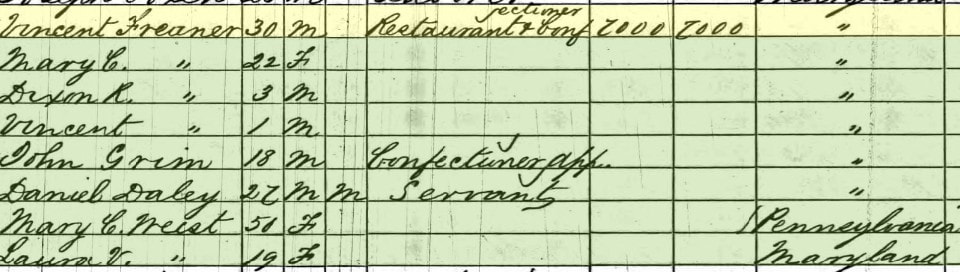

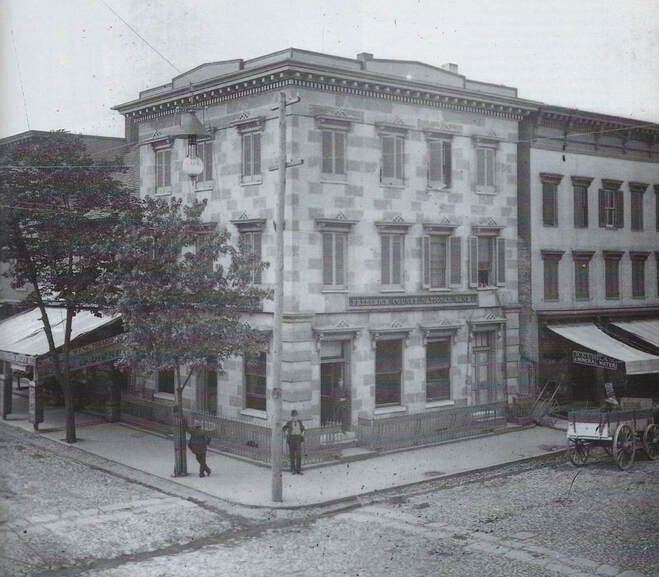

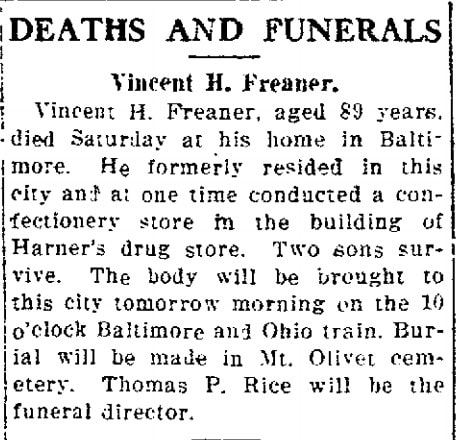

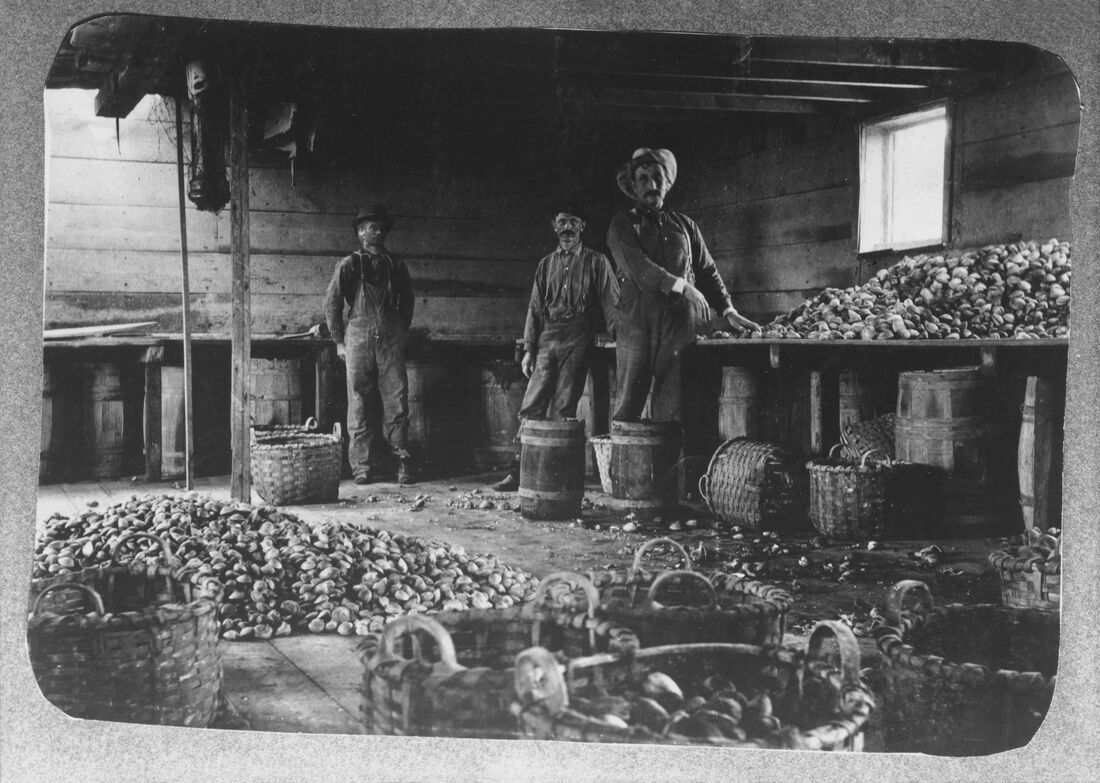

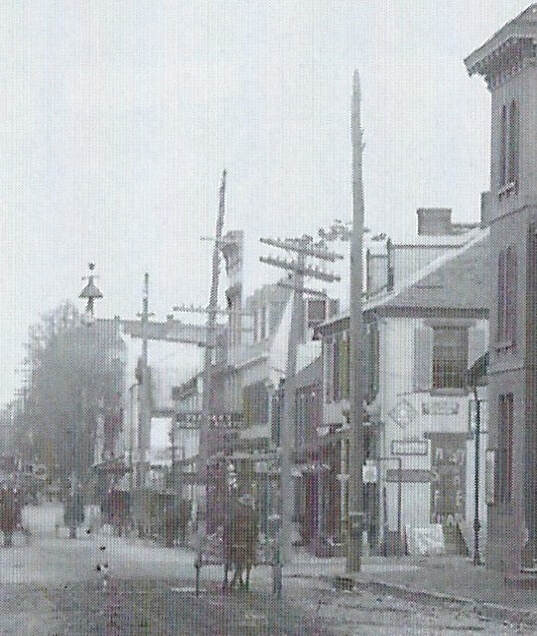

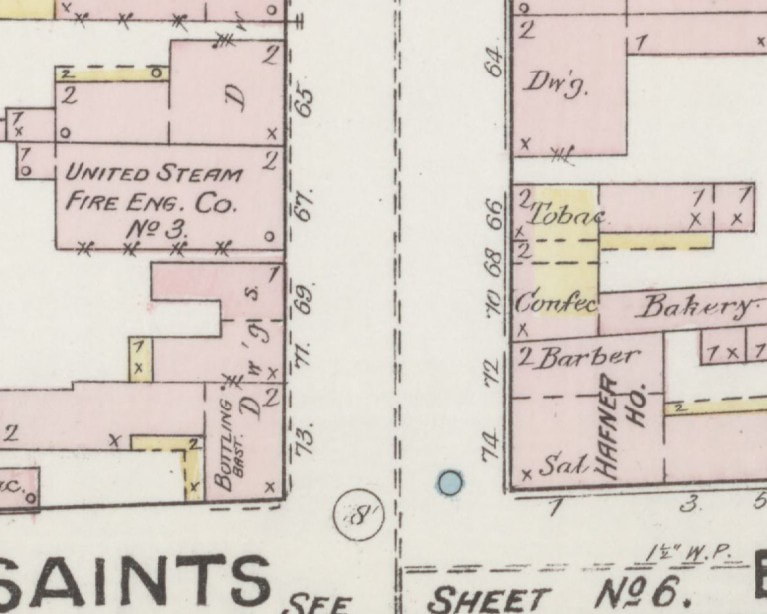

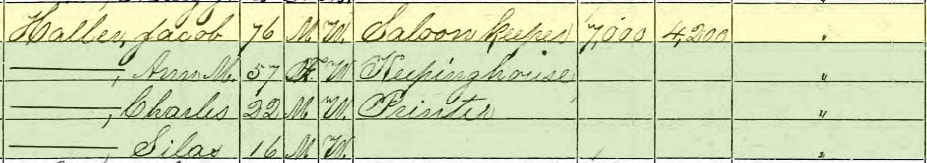

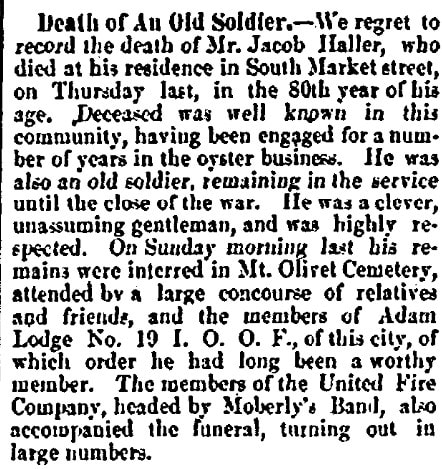

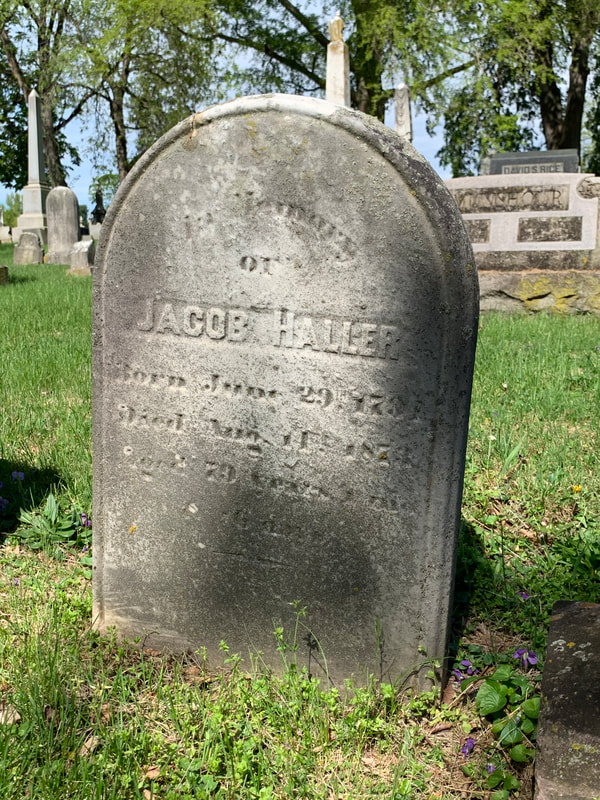

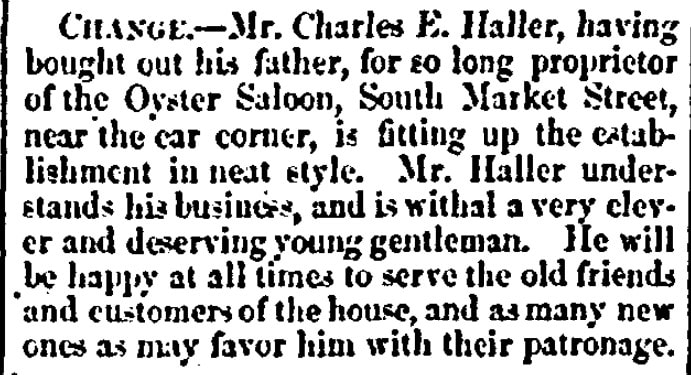

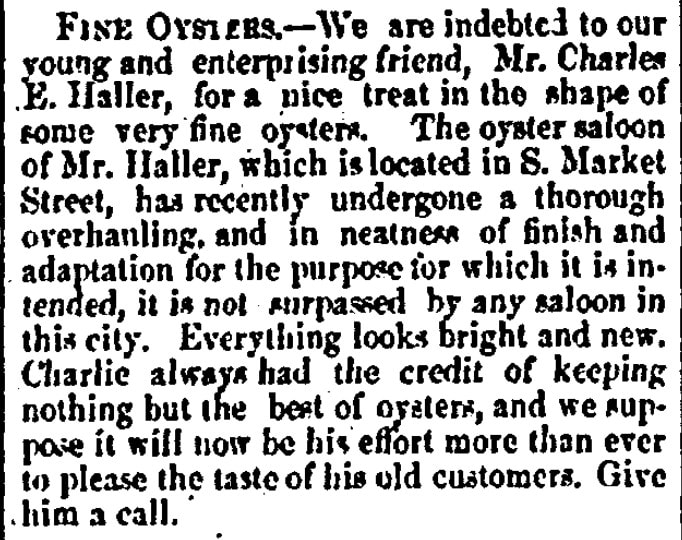

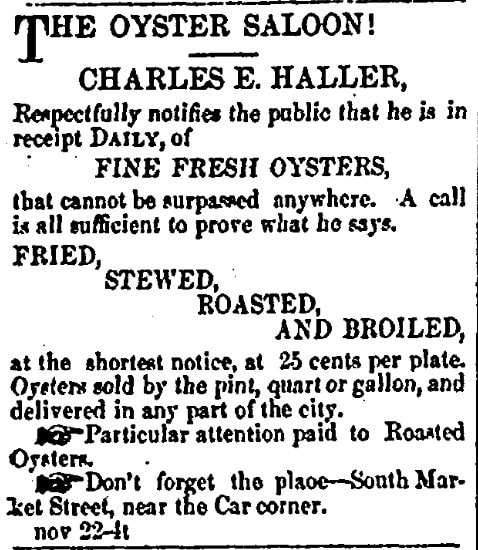

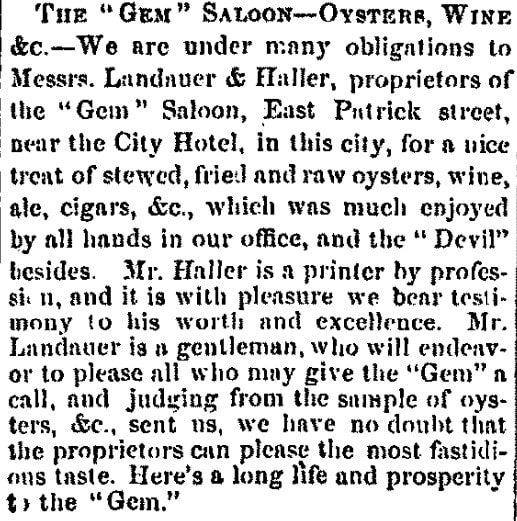

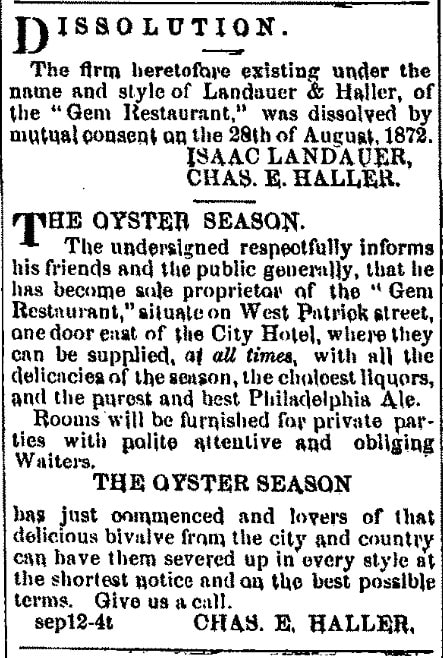

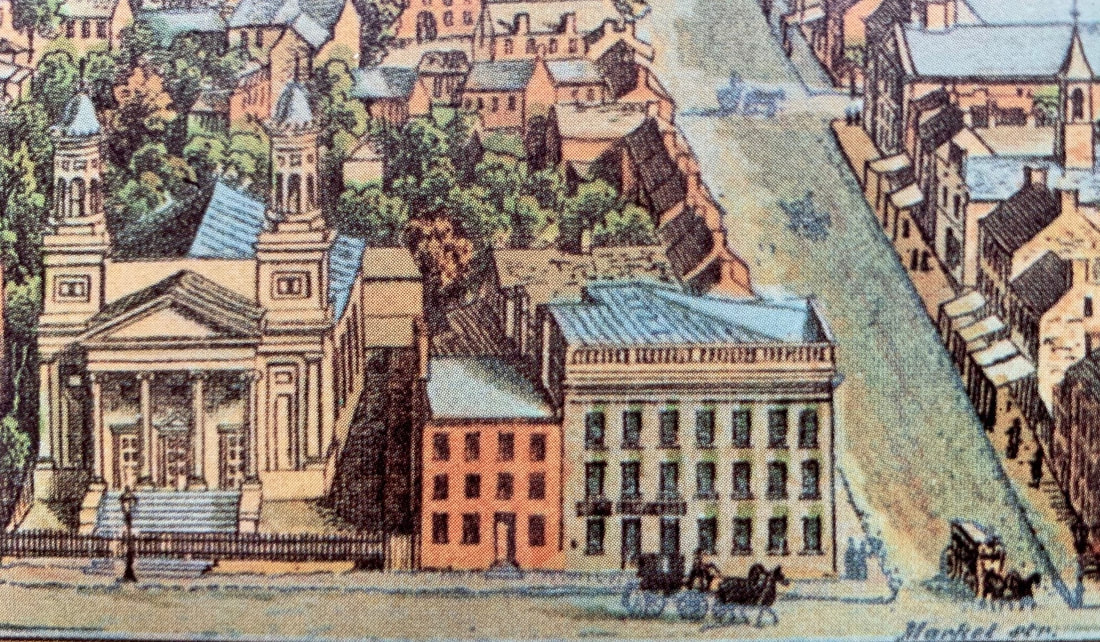

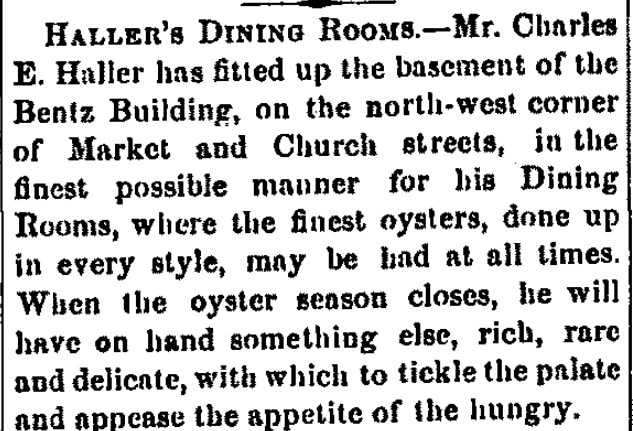

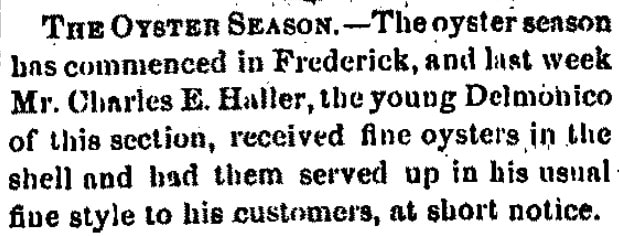

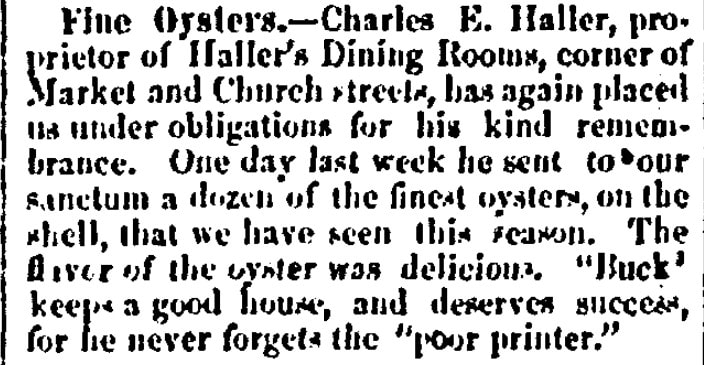

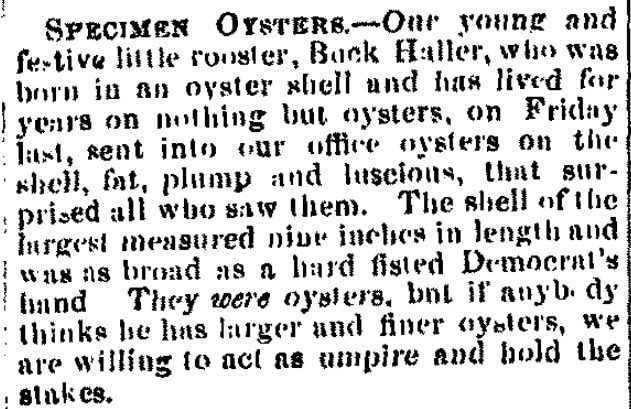

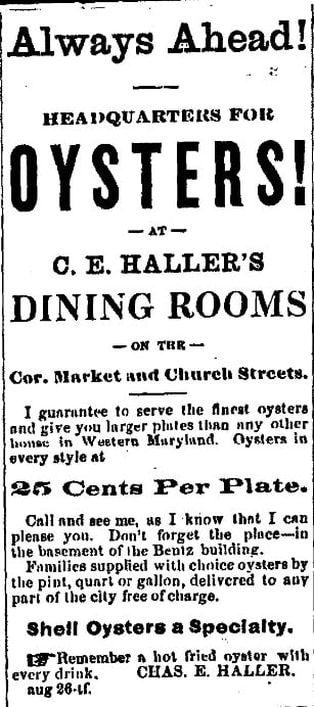

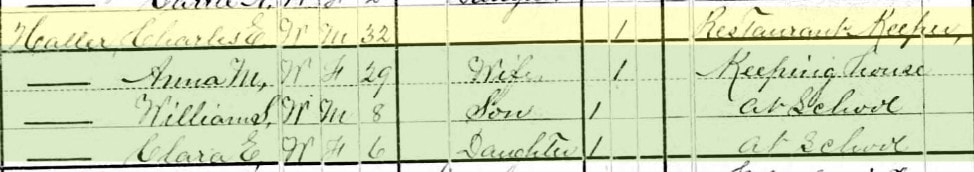

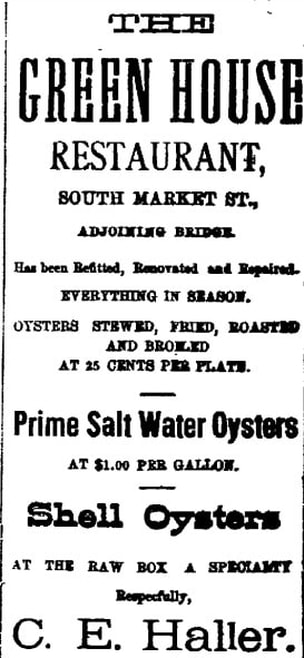

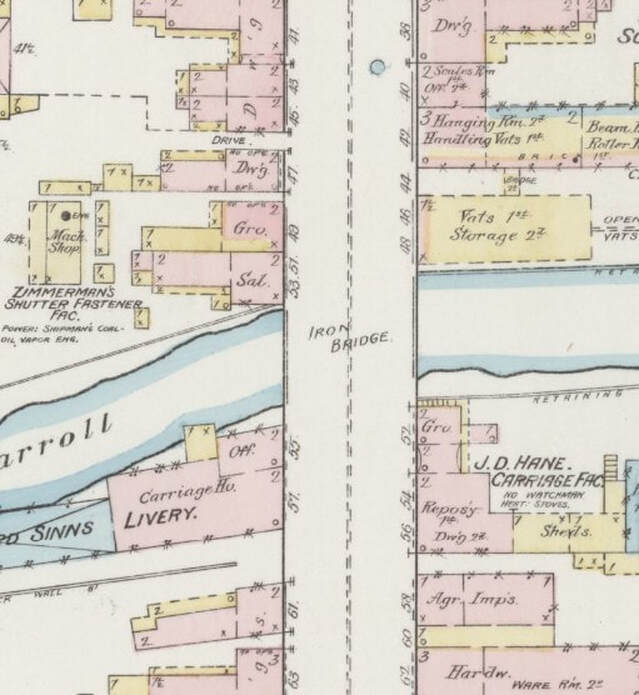

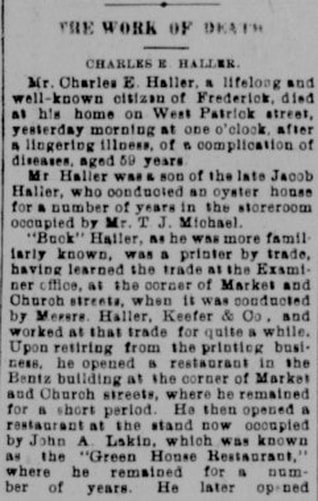

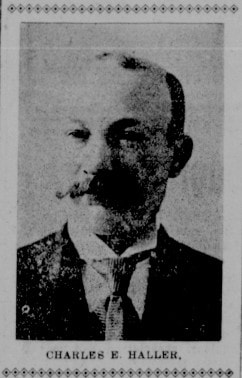

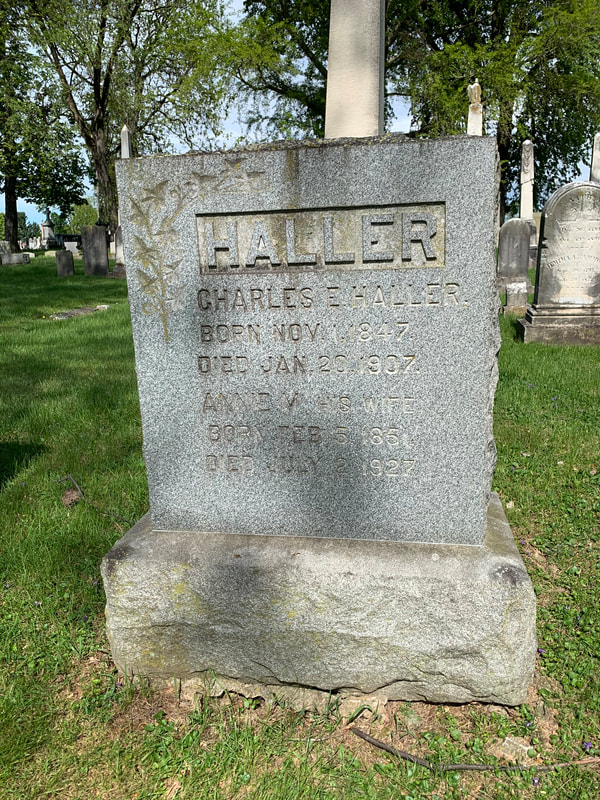

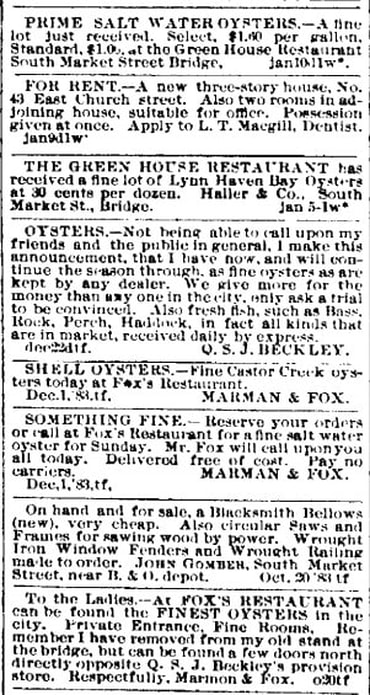

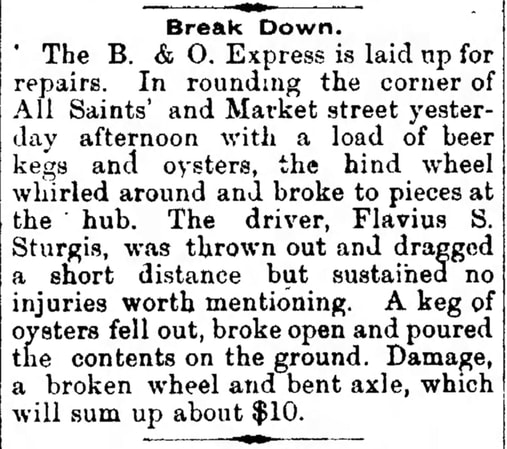

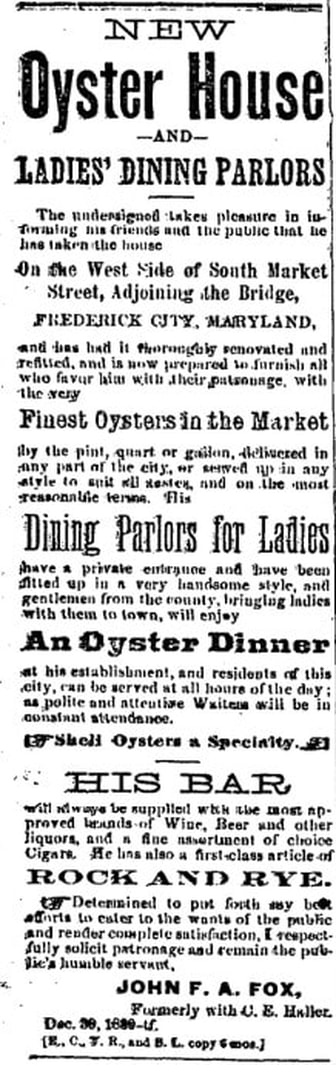

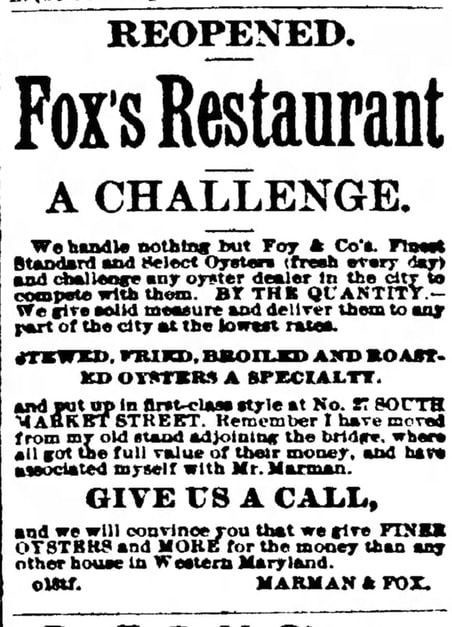

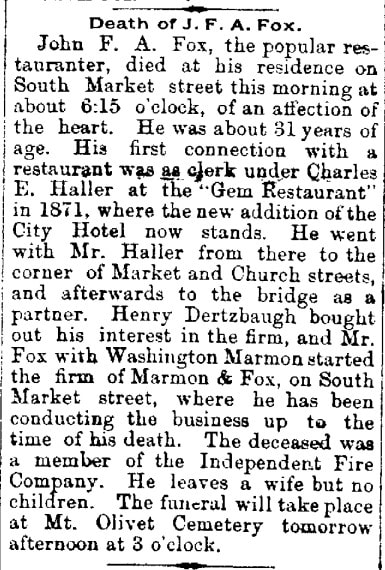

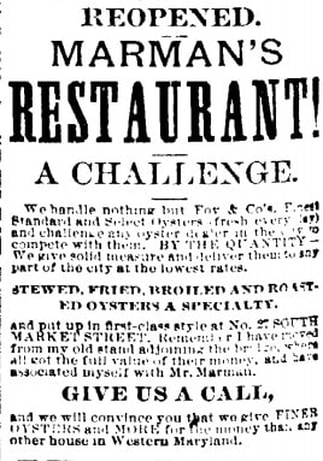

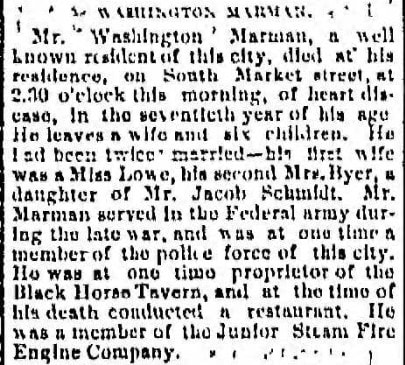

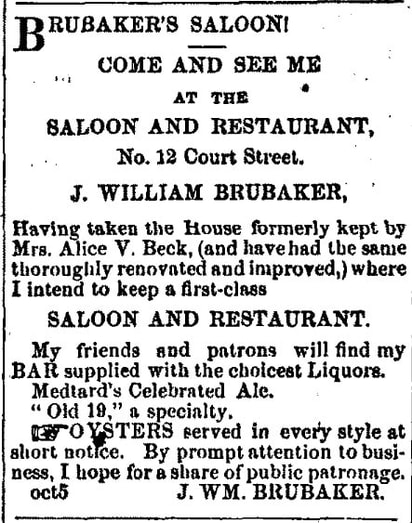

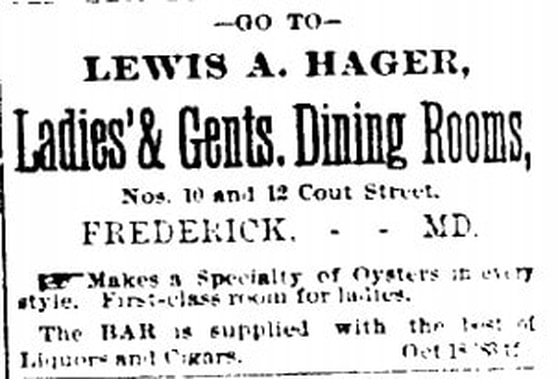

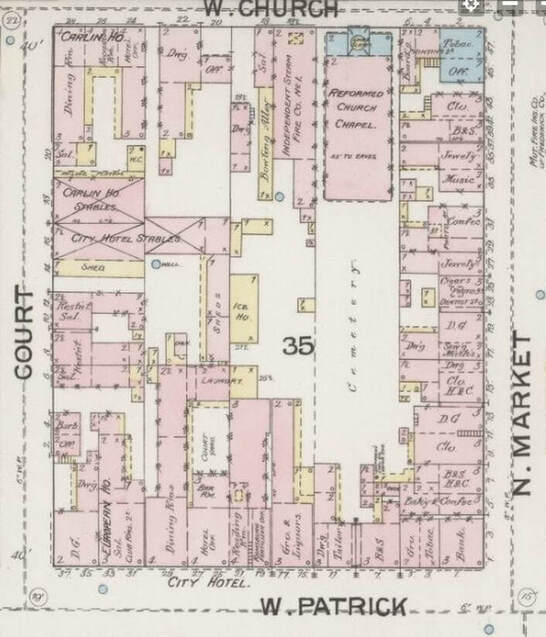

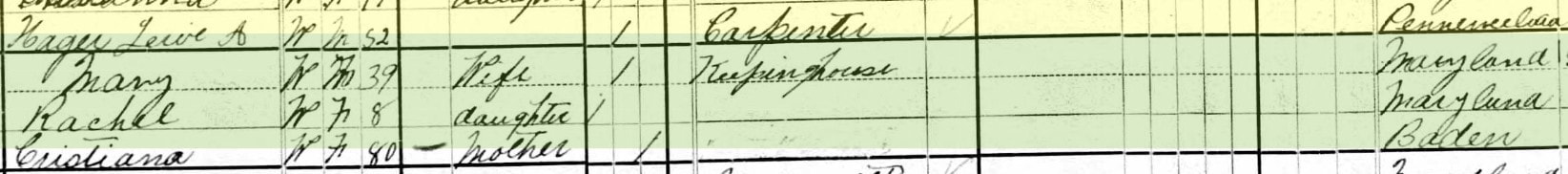

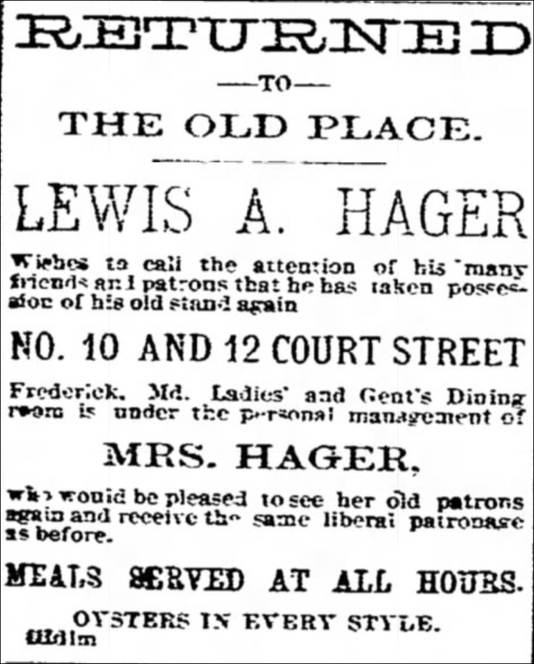

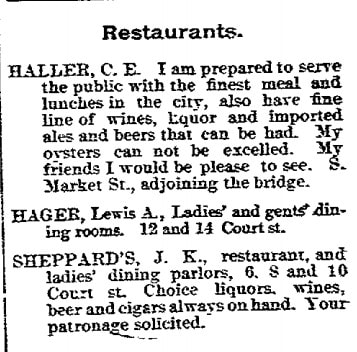

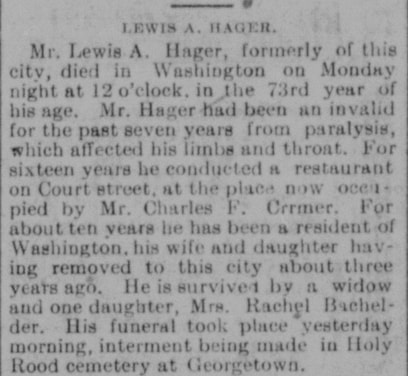

Wait a minute, did I miss Maryland oyster season? May is here already? What the heck happened to March and April?! It’s like they were here and gone in “the blink of an eye”—and this even with time seemingly on our hands while in self-quarantine with social distancing. Ah yes, Maryland oyster season. Many of us missed it --as it officially ended on March 31st. Those in the know are well aware that May does not contain an “R.” Neither does June, July or August for that matter. Luckily, here in Maryland, “the seafood gods” offer us the crustacean consolation of steamed crabs to help us get by until September. According to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources website: “The oyster season runs from October 1 through March 31. Harvesting Methods: A person may catch oysters recreationally only by hand, rake, shaft tong, or diving with or without scuba equipment. Also a resident may not catch oysters recreationally while on the boat of someone who is catching oysters commercially."  As is true today, oysters are only to be eaten in months with an “R.” This idea is an ancient one, dating back to sixteenth and seventeenth-century England. While some think it is just a superstition, there are actually good reasons for it, grounded in the fact that oysters spoil much more readily in warm weather. Furthermore, oysters are thin and have a less desirable texture and flavor during the summer, the period when they spawn. Oh well, Maryland oyster season has officially ended, but there are still some ways to get them as they are mostly farm raised this day, and plenty of frozen specimen are on, or in, ice as we speak! I usually revel in getting my fill as I enjoy frying up my own oysters on holidays, other special occasions, and for an occasional football tailgate. In addition, I have some friends that have the same adoration for oysters—a love borne out of annual treks made to Tilghman Island for all-you-can-eat oyster buffets in earlier, more care-free days before family obligations curtailed the practice.  "Tilghman" Haugh "Tilghman" Haugh I love both oysters and Tilghman Island, so much so, that I gave the place name to a former dog of mine. I chose the moniker "Tilghman" over naming him “Oyster," as that would have been a weird name for a canine. For those not familiar with Tilghman Island, Maryland, it is a small town located at the end of Talbot County’s Bay Hundred peninsula on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay. Wedged between the Bay and the Choptank River, Tilghman Island is less than three miles long and a mile wide. It is named for an old Maryland family. Although Tilghman Island has seen 13,000 years of human habitation, many families came here after the American Civil War, attracted by the booming oyster industry and the opportunities it presented— ranging from dredging/tonging the oysters to packing/shipping the animals to nearby market centers. Tilghman Island became Maryland’s pre-eminent watermen’s community and home to the famed skipjack fleet.  The Chesapeake is justifiably famous for its oysters. Indeed, one translation of the word Chesapeake from the Algonquian Indian language is “Great Shellfish Bay.” This was certainly the case when the first Europeans arrived to establish the colony in the 1600s. These numbers were the result of virtually ideal conditions for oysters in the Bay. It offered relatively shallow waters that were rich in nutrients and with generally firm bottom conditions. Forest-covered lands that bordered the rivers and creeks deterred erosion, which meant that little silt would cloud the waters and clog the gills of oysters. Ocean water from the Atlantic was diluted by fresh water flowing into the Chesapeake to produce the moderately salty water in which oysters thrive. Apparently, no serious diseases infected the shell beds. Finally, since the number of people living in the Chesapeake region for most of its existence was low, and since they had relatively simple technology for harvesting shellfish, oysters could grow and flourish without major disruption by humans. There is little evidence of seafood marketing during the colonial era in newspapers. It was the 1800s that saw oysters viewed as something more than just a local Maryland delicacy and food resource. The rise of cities such as Baltimore, Norfolk, Washington, DC, and Richmond spurred more demand for seafood, and harvesting of oysters and fish began to increase. In the 1830s and 1840s, several key events occurred that had a profound impact on both oysters and the Chesapeake Bay. One was the discovery of massive oyster reefs in the deep waters of Tangier Sound off Crisfield (MD). Another was the development of canning technology that made it possible to preserve oysters effectively. At the same time, the emergence of steam-powered ships and railroads meant that transportation became more dependable, and perishable seafood could be carried to distant markets. These innovations sparked commercial harvesting and the take of live oysters expanded rapidly. The boom began and later, so did “the oyster wars.” As for Frederick, we are certainly not considered to be on the water as Carroll Creek and the Monocacy River don’t count. However, we are well-connected to Baltimore, and have always been a bustling transportation crossroads kind of town with ample access to “the bounty of the Bay,” so to speak. In doing my usual research in vintage local newspapers, I often stumble across advertisements for purveyors of this particular bivalve mollusk. Here in Frederick, you could dine on these creatures in grand restaurants, blue-collar bars and at home thanks to carry-out retailers who provided “curb-side service” back in the day. There were actually hucksters who use to sell oysters out of a portable stand in the same manner of hot dog and pretzel vendors in big cities. Long gone, I sought to “dredge-up” a few of those “brackish” oyster entrepreneurs of the 19th century, hoping of course to find some of them buried here in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Here are the results, however, I may warn you that I found plenty of pearls which extended a single story into three-parts herein contained. Bon appetit! Frederick Getz One of the earliest mentions found of an oyster establishment in Frederick was that of Frederick Getz, who advertised in the Republican Gazette newspaper of Frederick in 1823. Mr. Getz was born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in March, 1781. He had recently re-located to Frederick from Baltimore, likely seeking the opportunity the inland town represented as a new market for the Chesapeake Bay delicacy. According to ads, Frederick Getz opened a confectionary store in Frederick in 1823, and was residing with his wife, Mary, on East Patrick Street in the stone house formerly occupied by Dr. Bogen between the grocery stores of Stuart Gaither and Thomas Conner. Gaither's grocery store was on the south side of East Patrick, roughly where Jojo's Restaurant and Serendipity Market are now. Little is known about Mr. Getz because his time here in town was brief. While in Baltimore, he had opened an oyster establishment in a landmark structure known as the Stone Tavern at the northeast corner of Bridge (today’s North Gay Street) and North Front streets in Baltimore in 1822. He advertised this as a place of entertainment featuring oyster suppers. Beforehand, Getz had a confectionery business in Charm City.  J. Engelbrecht J. Engelbrecht Frederick Getz' big plans for Frederick, the town that shared his name, were short-lived as he would suddenly pass--just one year after he arrived in town. Diarist Jacob Engelbrecht chronicled the event in his diary on Tuesday, September 14th, 1824: “Died this forenoon in the 42nd year of his age, Mr. Frederick Getz (resident of this place about 2 years). In all probability he will be interred with Masonic honors as he belongs to that “Parish.” Buried German Reformed graveyard.” Getz, along with over three hundred others, remains at the Old German Reformed burying ground, today better known today as Frederick’s Memorial Park, located at the corner of North Bentz and West Second streets. His name appears on a plaque on the east end of the park. His grave could be under one of several 20th century war monuments. Alfred D. Bladen In late September, 1823, advertisements began running in the local Frederick paper for the oyster establishment of one, Alfred D. Bladen. This was the same time that Mr. Getz opened his business in town. Bladen can be found living in Richmond, Virginia in the 1820 census. His foray into Frederick occurred in the winter and start of 1823 in which he apparently sold oysters. We next get a glimpse of him in May (of 1823)at which time he is advertising his services as an upholsterer and located in the old law office building on Court Street across from the Frederick County Court House. As a side note, this is not the small building that exists today, but one that existed slightly north of this site and likely served as an early office for Francis Scott Key as it had been used primarily by lawyers as such. The following month, Jacob Engelbrecht reports that Bladen’s rental dwelling, also used as his residence, was involved in a fire. Apparently there was a high degree of gossip and hearsay attached to this unfortunate incident—enough indeed for Mr. Bladen to acknowledge his displeasure, complete with a stern warning to his critics. The oyster house ad above states that he (Bladen) has found a new home on Patrick Street by the fall of 1823, and asks patrons to “consider his losses sustained in his late calamity.” The next mention I could find of this man is in the Baltimore papers in May, 1826. Alfred D. Bladen seems to have turned things around and eventually opened a new establishment in Washington, DC called the Eagle Tavern, and positioned near the capital, in 1828. He experienced nice success at first but was subsequently kicked out by his landlord for failure to keep up with his rent. Apparently, he would make another move to Norfolk. Virginia in spring, 1832. Tragedy struck the following September as he had two children die in the infamous cholera epidemic that hit our country. Mr. Bladen, himself, would die in May, 1833 at the age of 39. I'm assuming that he was buried in Norfolk, but his gravesite may be unknown at this point. William Saunders The oyster cellar of William Saunders must have been one to behold. In addition to having oysters prepared anyway you'd like, you had the greatest beer selection in all of western Maryland at the time! The location in which Mr. Saunders would conduct business was smack dab on the National Pike and in the middle of Frederick's early hotel district. This exact location, on the northeast corner of West Patrick and Court streets, would be the scene of several oyster establishments in the decades to follow. Upon finding the above advertisement, I immediately became curious as to the label of "oyster cellar" used by Mr. Saunders. I soon learned that establishments serving our "shellfish in question" went by various names, especially when paired with beer in a bar-like setting--case in point, oyster bars. Oysters were seen as a cheap food to accompany beer and liquor so you could also find both in oyster parlors, oyster saloons, or oyster cellars. These establishments were often located in the basement of establishments where keeping ice was easier. As the ad above declares, Saunders kept his "oyster cellar" under a tailor's shop at that time. William Saunders was operating a bar of some sort here in town as early as 1822, this based on newspaper listings. He, himself, only had a five-year run as I would learn from Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht who mentions Saunder's death in a brief entry made on October 18th, 1827. "Died this day in the year of his age, Mr. William Saunders (oyster man) of this place a native of England." I also learned from Engelbrecht that Saunders had a business associate who had "crossed the pond" with him to America. This was a man named Abraham Sherwood, a right hand man in running the oyster cellar in Frederick. Sherwood was a tailor from Kent County, England, and I'm thinking that he could have kept the business above ground during the day. Mr. Sherwood died two years after Saunders in 1829. Both men were originally buried in the old All Saints Protestant Episcopal burying ground, once located atop the hill between East All Saints Street and Carroll Creek. They shared a headstone here that gave more information about each. It read: "Cemented by Love (displaying a Masonic Compass and Square) William Saunders died Oct'r. 18th 1827, aged 41 years. Native of England." and "Abm. Sherwood died April 15, 1829, aged 42 years, Native of England." I'm not going to read anything into the "cemented by love" expression, but I assume the two were very close, regardless.  In 1913, the bodies of these two gentlemen were moved to Mount Olivet. Saunders and Sherwood are buried in Mount Olivet's Area MM in lots purchased by the All Saints' Vestry in 1913 as part of a mass removal project of the church' s old burying ground. Saunders is recorded as being buried in Lot 52. As was customary with shabby looking grave markers, the headstone mentioned above is noted as being buried beneath ground here in the vicinity. Sherwood is within Area MM/Lot N-35, the mass grave which holds n 285 other bodies.  John G. Holmes Another early spot in town for oysters doubled as an early election precinct location in 1831. This was the oyster house of John G. Holmes, of whom I have been able to find little except him living in Frederick at the time of the 1830 census. Perhaps Holmes picked up the former business of Getz, Bladen or Abraham Sherwood, but I have not made a definitive connection. He appears to have overcome some financial challenges a few years previously and was operating fine. The interesting thing about the timing here is that the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad came to town that same year. As mentioned earlier, this surely provided a more dependable means to safely bring oysters in regularity to the people of town.  Republican Gazette and General Advertiser (Jan 16, 1829) Republican Gazette and General Advertiser (Jan 16, 1829) My assistant, Marilyn Veek, found a brief article from 1828 regarding John G. Holmes being jailed for being insolvent. I have included it to the right for your reading pleasure. On the bright side, Holmes was an "engine man" for the Washington Hose Company in 1829. We also found that the John G Holmes Oyster House would serve as a voting precinct for Frederick's Ward 5 in the Corporation election of 1831. Thanks again to the Diary of Jacob Engelbrecht, we have an idea of what eventually became of Mr. Holmes, another oyster promoter who died far before his time: Died last evening in the year of his age (38), Mr. John Glen Holmes, Shoemaker, son-in-law of the late Daniel Cassel. His death was rather sudden, having been struck on the neck by Harrison Knight in a dispute which took place in George Rice’s cellar (a Restarature kept by a Mr. Keach). His neck was broke and instantly died. Mr. Knight was not aware that he had killed him and left the cellar for home. He delivered himself to the Sheriff immediately thereafter, say several hours. Mr. H. was buried this evening at 6’o’clock on the Lutheran graveyard, east end of Church Street. Sunday, July 29th, 1838 Engelbrecht mentions a second Lutheran burying ground in downtown Frederick. This was located on the southeast corner of today’s Everedy Square at the intersection of East Church Street extended and East Street. Most of these bodies were re-interred to Mount Olivet in the early 20th century. I found that we have several members of the Holmes family here at the Mount, but not John G. Holmes. There is a possible son by the name of John Lewis Holmes (1824-1893). He and other Holmes relatives are in Mount Olivet’s Area P/Lot 110. I've even theorized that there is a remote chance that John G. Holmes is here without a stone, or there could have been a bit of record confusion upon the time he was brought in to our cemetery. Not to be a downer, but these large-scale reburial operations always had good intentions of having "no one left behind"—but it was a difficult task, and some bodies didn't make the trip. I’m not saying that Mr. Holmes is residing under Talbot’s Department Store, but since he's not clearly visible in our cemetery records, there is a mathematical chance. That said, I was delighted to find Holmes’ killer, Mr. Knight, buried within Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 96. With the early demise of all five of our earliest known “oystermen of Frederick,” I began to think that there could have been some curse associated to their business staple, as it clearly can be seen that “the world was not their oyster.” I also started wondering how healthy oysters were for you back in the day. I'm sure it was merely coincidence that each of these men died before they were 44 years old. Regardless, Frederick was very progressive to have multiple oyster purveyors dating back to the 1820s.  Frederick (c. 1862) Frederick (c. 1862) By 1850, nearly every major town in North America had some sort of oyster bar in their vicinity. The oyster was well on its way to becoming arguably the most popular food of the 1800s. Following its earlier popularity in Great Britain, the celebrated mollusk was as American as apple pie. So the next time you want to honor your nation’s culinary past, why don’t you try serving this wonderful seafood. It was a common thread between old and young, rich and poor, black and white, and in the early 1860s, North and South! During the Civil War era, I found a few wholesale and retail establishments advertised. These included men such as Jefferson Boteler, Ambrose Carson and George Freaner, buried here in Mount Olivet, and another named George Shaffner. I could find very little on each, probably because they seem to have been journeyman as opposed to locals for life. It also seems that some of these men tried a hand at living in Baltimore, perhaps in order to achieve a deeper connection to their trade. Perhaps this was a deadlier task than eating oysters daily? A native of York, Pennsylvania, Ambrose Carson was a carpenter whose specialty was making chairs. His wife was from Baltimore and likely had a pipeline to oysters. Ambrose appears as an early supplier to Frederick in the wholesale/retail realm. George Washington Tice Shaffner was the son of Peter and Ann Shaffner, who were re-buried in Mount Olivet after original interment at Evangelical Lutheran's burying ground off East Street. Shaffner's oyster house location, mentioned in the above ad, says that he was three doors above the Junior Fire Hall which had its original home on North Market Street to the immediate north of today's Brewer's Alley Restaurant. George Shaffner married Mary Exline in 1875 and bought a house on East Patrick Street in 1877, but seems to disappear from the record, at least locally. It's interesting to note the former occupations of some of these oyster purveyors. I often see confectioner, which I always thought was something that related to a person whose occupation is making or selling candy and other sweets. I guess there is a close relationship to cakes, doughnuts and fried oysters, (sometimes called oyster fritters) than I had originally thought. Vincent Freaner is an example of someone that made the leap. Freaner's location was near Frederick's Square Corner intersection of Market and Patrick streets, just one door north of the old Frederick County National Bank building. "Frederick's Oystermen" Part II I would venture to say that one of the most colorful of "oyster salesmen" during the period of the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s was Jacob Haller, Jr. —a former veteran of the War of 1812. From mentions I have read of this man, his oyster business at least dates back to the year 1860 where the census lists "the old defender of Fort McHenry and Baltimore" as a restaurant keeper. Jacob Haller, Jr. was born on June 29th, 1795 to Jacob and Anna Maria (Hockwerdter) Haller. He grew up in south Frederick and served in the 1st Regiment, Maryland Militia under Capt. Nicholas Turbutt from July 23rd, 1814 to January 10th, 1815 during the War of 1812. Haller was twice married, the father of ten, and began his working career as a saddle-maker. Haller was very active with the fire community and also dabbled a bit in politics, elected as a member of the town's Common Council in 1841. In 1850, he can be found living in Baltimore but returned home somewhere within the decade, likely to begin his retirement. For one reason or another, he decided to open up a bar/restaurant on South Market Street near its intersection with All Saints Street. Jacob Haller's Tavern, also known as Haller House, was in operation until the early 1870s. The location consisted of current day properties 68, 70 and 72 on the east side of the street. Mr. Haller was a loyal member of Frederick's Washington Hose Fire Company, and later United Fire Company whose "Swamp Hall" was practically across the street. I’m sure he made a killing off his fire company buddies who I assume loved nothing more than beer and oysters. Jacob Haller, Jr. died on August 14, 1873 at the age of 79. His property would be auctioned off at the City Hotel shortly thereafter. Phillip Haller obtained ownership of the Haller property in September 1874. Philip appears to have run the establishment for a few years before selling it in 1878. Jacob’s son, Charles Edward Haller (1847-1907) would graduate into the oyster business as well in the early 1870s. Born November 11th, 1847, Charlie Haller had taken over the main responsibilities of his father a few years before the elder Haller's death. A printer by trade, "Buck" Haller successfully made the transition to restaurant keeper. He gave the old place a makeover and certainly left a lasting impression on the city as having the most industrious, progressive and successful bivalve run of anyone. Charles E. Haller would move on from the Haller House location and join Isaac Landauer in operating an oyster eatery named "the Gem" on West Patrick Street. This place, once the site of Turbott's Tavern, run by his father's old military commander, was made a new addition to the City Hotel, and located near the intersection with Court Street. This was almost the same locale of the oyster bar run by William Saunders and Abraham Sherwood some fifty years earlier. After a year and a half, Haller would serve as sole proprietor. In 1875, "Buck" Haller made another move of two blocks to another location. He would set up shop in the basement of the Bentz Building on the northwest corner of Church and Market streets. Today, this location is home to the popular Tasting Room restaurant. Haller's youth, drive, charisma and marketing brilliance, exhibited by delivering free samples to the newspaper staffs of town, set him apart from his competitors. After a couple years, young Charlie Haller was on the move again, this time choosing a a location closer to his roots on South Market Street. The destination was on the north side of Carroll Creek, on the west side of Market. Today's La Paz restaurant's patio marks the approximate location. A former employee, John F. A. Fox had tried giving this location a go, likely bankrolled by Mr. Haller himself, but surrendered it to his former employer and selling a partnership to his own brother-in-law in an effort to go to work selling oysters for a man named Washington P. Marman. Mr. Haller would give this saloon a makeover as well, attracting a higher brow clientele then those it had been dredging up for years. He renamed the establishment the “Green House Restaurant." I found that Mr. Haller did some novel advertising in the local papers, and even placed ads in Thurmont’s Catoctin Clarion to attract north county patrons. The 1887 Sanborn Insurance Map shows clearly the location of the saloon on S. Market at Carroll Creek, operated by C. E. Haller as "the Green House Restaurant." Haller would run The Green House, the premiere place for oysters and seafood in town, until 1893, when he decided to sell it. He would set up shop again on East Patrick Street and then would attempt to retire later in the decade. This would be short-lived as he would be hired by a former employee named Charles N. Hauer to be the manager of the Buffalo Hotel's restaurant in 1898. Ironically, The Buffalo been the site of the earlier Gem Restaurant he oversaw some 25 years earlier. Haller helped Hauer on his way, and stepping aside after a year to lead a quieter life for health reasons. Mr. Haller died in 1907, and would be buried in Area C/Lot 94. His extensive obituary tells the story of a very successful businessman in various endeavors in addition to oysters. In my opinion, he should hold the title of "Oyster King" of Frederick City. Frederick's Oystermen Part III By the late 1880s, an "oyster craze" had swept the United States, and oyster bars were prominent gathering places in Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Denver, Louisville, New York City, and St. Louis. An 1881 U.S. government fisheries study counted 379 oyster houses in the Philadelphia city directory alone, a figure explicitly not including oyster consumption at hotels or other saloons. In 1892, the Pittsburgh Dispatch estimated the annual consumption (in terms of individual oysters) for the city of London at one billion, and the United States as a whole at twelve billion oysters. The 1880s seems to have been "the high water mark" of competing “oystermen” in business here in Frederick. A prime example is the clipping above featuring several oyster-related advertisements found in the January 14th, 1884 edition of the Frederick News. As a matter of fact, if you were one of the "shuckin' lucky ones," you could have found oysters and beer in the streets of Frederick on one glorious day that same year. Fox & Marman John Frederick Augustus Fox was born on September 29th, 1852. His father, a successful tinsmith, was born in Stadthagen, Germany, and came to this country in 1841, where he settled in Middletown. Interestingly, tinsmiths played a major role in the growing commercialization and consumption of oysters through their ability to make storage cans. Perhaps young John was brought into the industry through this avenue? Whatever the case, John F. A. Fox worked as clerk under Charles E. Haller at the "Gem Restaurant" dating back to 1871. He was only 19 years-old at the time. Fox followed Mr. Haller to various other locations and eventually became a partner in The Green House location along Carroll Creek. Around 1883, for one reason or another, Fox’s brother-in-law (Henry Dertzbaugh) bought out his interest in the firm. John F. A. Fox went to work for Washington Marmon as a salaried clerk. Interestingly, his name would be used as a member of the firm--Marmon & Fox operated on South Market Street. John F. A. Fox was married, but had no children. He was a member of the Independent Fire Company. Sadly, in January, 1884, just weeks after announcing a reopening of the business, John F. A. fox died at the age of 31. He was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 53. Washington P. Marman conducted the oyster business until the time of his own death (February 25, 1892). This was just over eight years after that of Fox. Born September 15th, 1823, Mr. Marman had an interesting background that included being a Union soldier in the Civil War, along with working on Frederick's earliest police force. He had previous experience in the hospitality trade as a one-time owner of the Black Horse Tavern that once graced the bend on West Patrick Street. He is buried in Mount Olivet's Area R/Lot 71. Lewis Hager For a guy who earlier in life was called upon to help quell John Brown's ill-fated insurrection attempt at Harpers Ferry in 1859, keeping control of rowdy patrons within an oyster saloon was likely not much of a challenge. The native Pennsylvanian was born in 1837 and living here in Frederick by the 1850s. Lewis Hager was a member of the Independent Riflemen (a fire company which doubled as a local militia group) and was among the first responders on the scene in Harpers Ferry, 25 years before he opened his business at a location on Court Street which was formerly operated by a J. William Brubaker since 1872. Mr. Brubaker would relocate to Columbia, Pennsylvania (between York and Lancaster) in 1885, opening the door for the cagey former militiaman, who was cursed with a rival town's name. Hager set up shop at #12 Court Street in the basement of Black's Hotel. Mr. Hager's parents were natives of Germany and the he can be found living in Frederick in the 1860 census. He was likely born in Perry County, Pennsylvania, and came to Frederick to live with his uncle after his biological father died in 1852. His birth mother seems to have died around 1839. Hager is listed as a carpenter, the profession of his stepfather/uncle Henry Hager, in the 1870 and 1880 census records. Lewis had married the former Mary C. Burck in 1862, and the couple owned two properties in the vicinity of the intersection of West South and Burck streets. He bought one property in 1875 from his mother-in-law, Christiana Burck, who can be found living with he and his wife in the above-mentioned census records. The Hagers also had a daughter named Rachel. It appears that Mrs. Hager assisted her husband as dining room manager. I could not find out why they chose to use the verbiage "re-opened" in the 1886 advertisement above? Perhaps they closed shop temporarily for personal reasons, or had a brief closing based on the oyster season, although I found nothing in newspaper searches of 1885. In 1890, the Hager's restaurant was among three dining establishments mentioned in a commercial directory feature in the Frederick News. The others included the previously mentioned Charles E. Haller, and a Mr. Job. K. Sheppard. Mr. Sheppard was a staple in the neighborhood, and would locate right next door in the summer of 1885 or so it appears in the papers. Interestingly, this is a period when the Hagers stopped advertising. Perhaps there was a business handoff for a while? I think that the property the Hagers were leasing was subdivided by ownership to accommodate both entities.

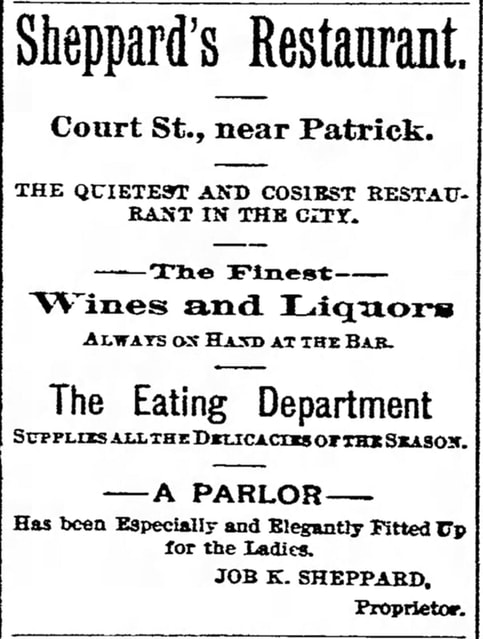

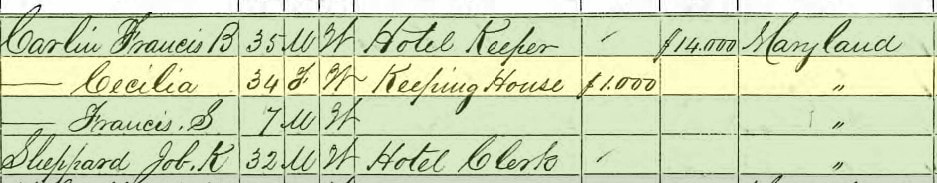

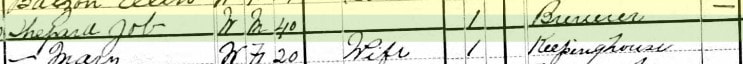

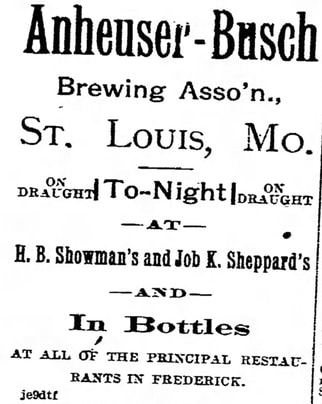

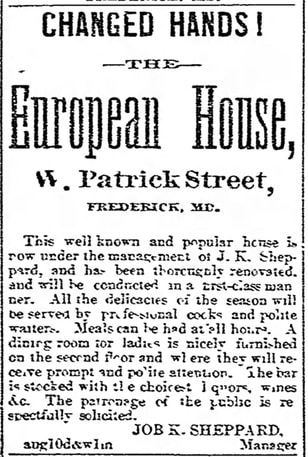

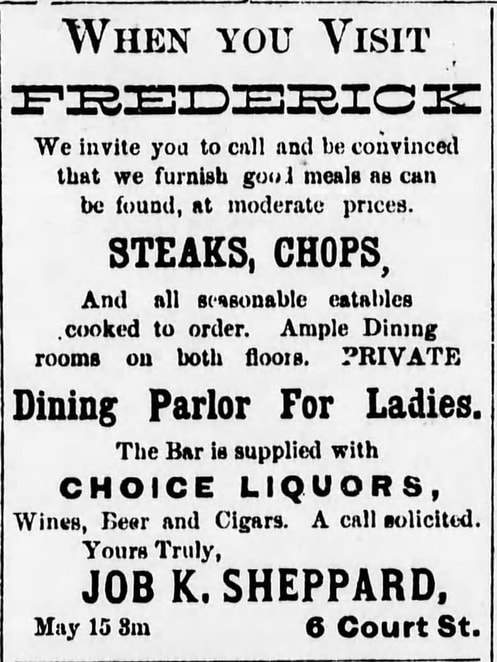

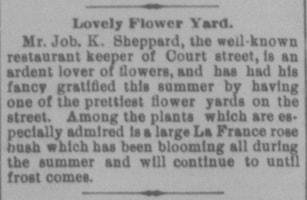

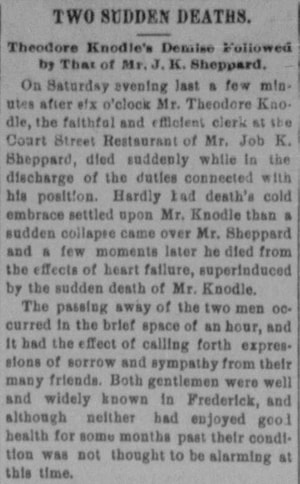

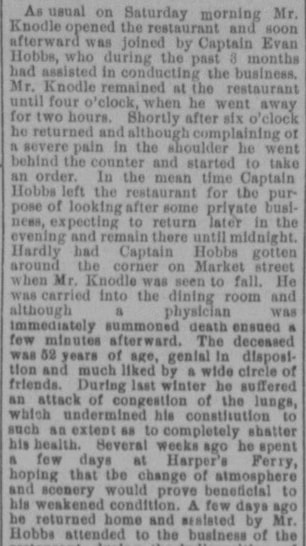

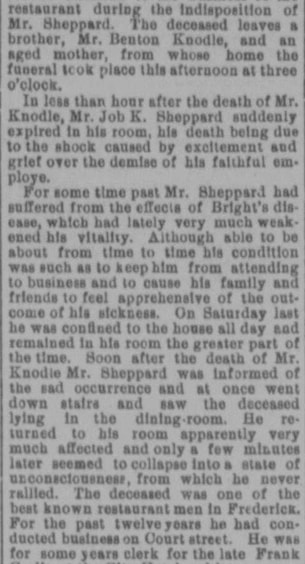

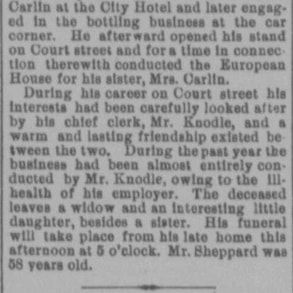

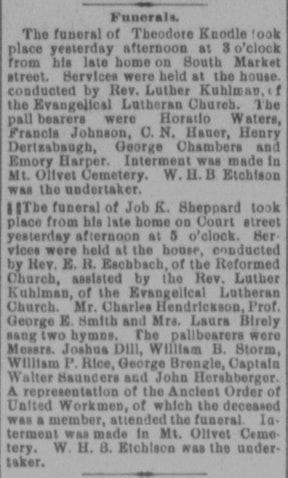

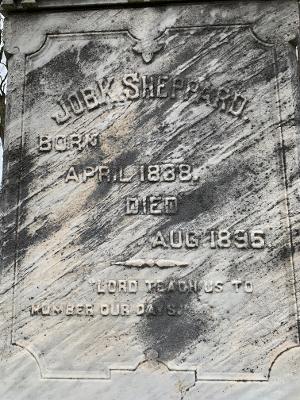

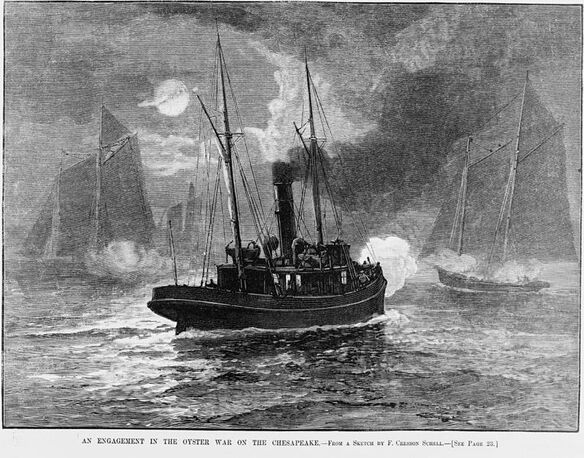

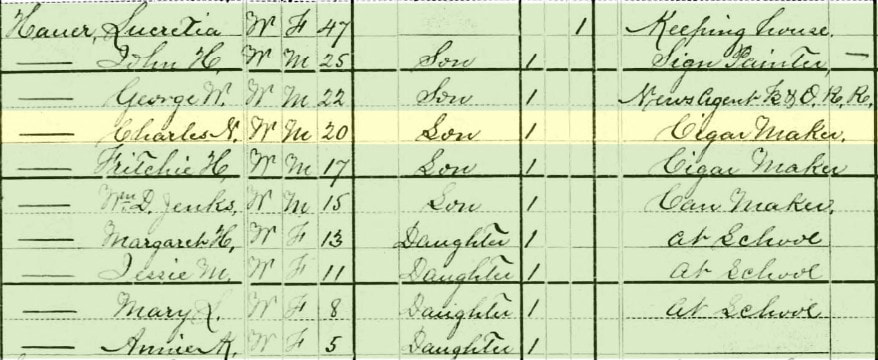

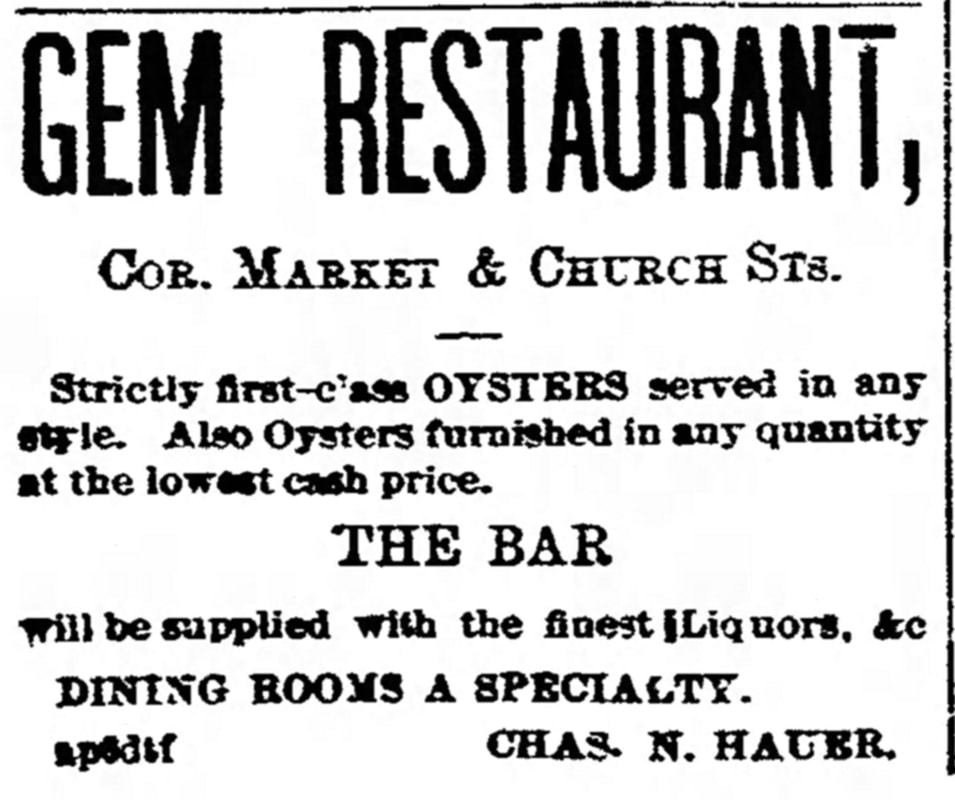

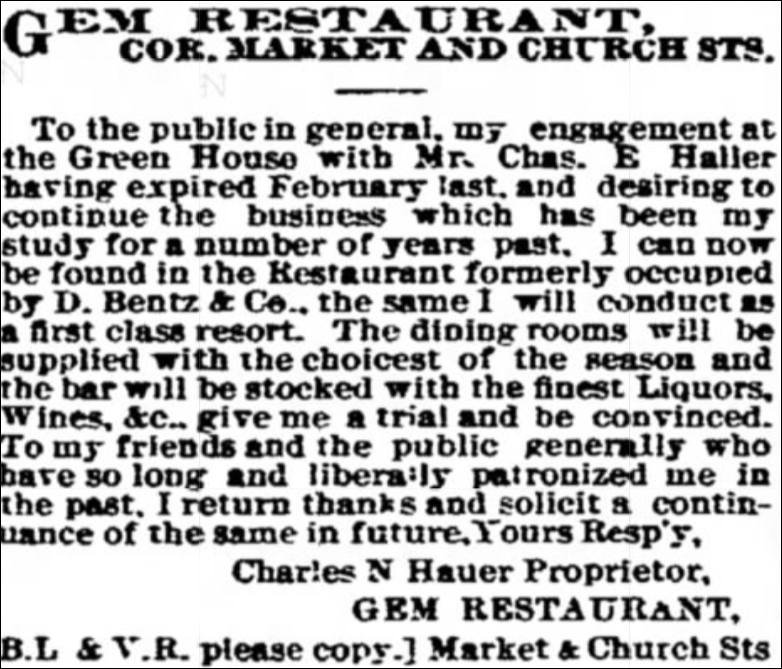

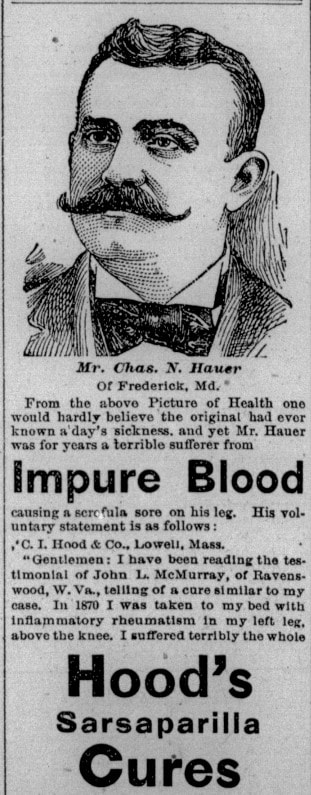

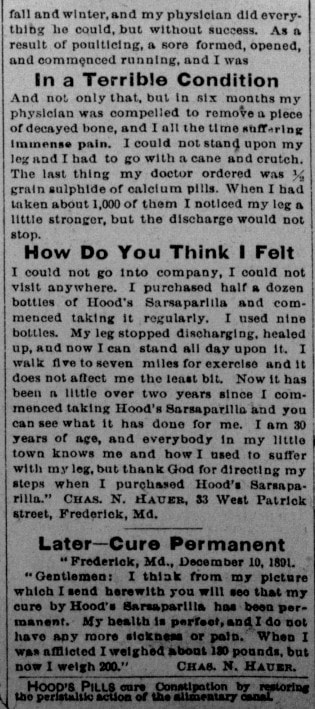

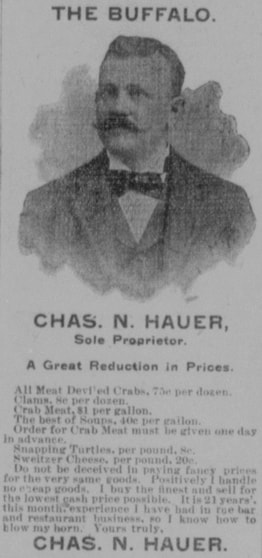

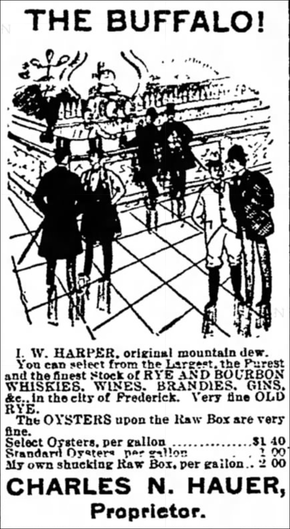

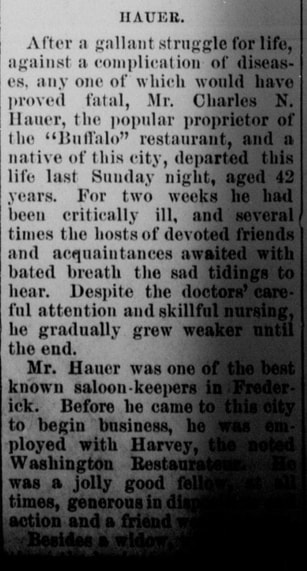

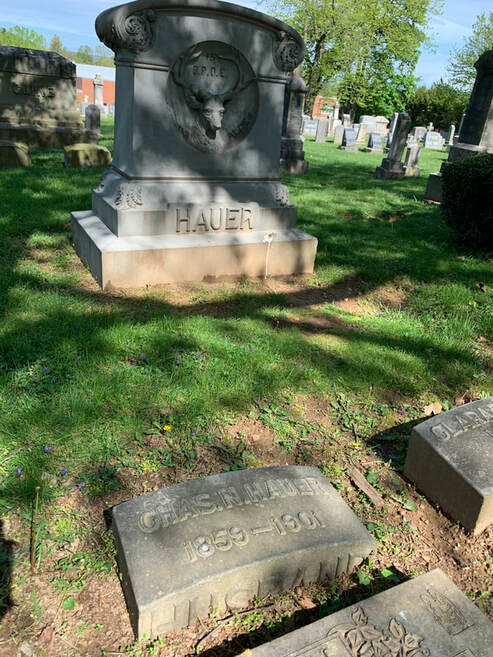

Job K. Sheppard I mentioned Job Kelsy Sheppard earlier in conjunction with Lewis and Mary Hager. He was born on April 14th, 1838 in New Jersey and came to Frederick as a shoemaker, at least according to the 1860 census. He was a member of the Junior Fire Company at this time and served in the Junior Defenders militia company. From a newspaper article of that time, he was praised as the company's best marksman. This came in handy as he would serve in the ensuing Civil War. In 1870, Sheppard was working as a hotel clerk for Mr. Frank B. Carlin who took over operation of the former Dill House at the corner of West Church and Court streets. Job came into the "oyster business" from another angle as he was listed as a brewer according to the 1880 census. Mr. Sheppard seems to have begun operation of his own dining establishment in 1885. I have a strange feeling that he may have been bankrolled by his old boss, Frank B. Carlin, who also happened to be married to his sister, Ann (nee Sheppard). Maybe Mr. Carlin could have owned the Court Street properties next to his hotel and livery stables and simply set-up Sheppard in an effort to compete with the Hagers?-- as his hotel guests were going somewhere to eat, and the eateries on Court Street were the closest choices. I also found that Mr. Sheppard was among the first restaurateurs in town to carry a familiar beer that is still with us today. In 1888, Job was given the "job" as manager of The European House, the elegant dining hall associated with the City Hotel. This had been run under the name of "The Gem" by Charles E. Haller a decade earlier. I'm thinking the selection of Job K. Sheppard came due to the fact that Mr. Carlin took ownership of the City Hotel at this time, and brought his faithful brother-in-law with him. Meanwhile, Sheppard still continued to run his popular restaurant around the corner on Court Street. Life marched on for Job Sheppard and almost every article I read about him talks about how nice and personable he was. He also seems to have possessed a great sense of humor and did some things to make himself stand out as the manager of what would become known as the finest dining location in town. Sheppard was aided by his right-hand man and barkeeper, Theodore Knodle. In looking for info on Knodle, I found him living on West Patrick Street in the 1880 census and working as a barkeep. He seemed to be the Yogi Berra of his day in regard to seafood talk, as he was regularly quoted in the Frederick News. Everything was going fine for this awesome duo until the fateful night of August 22nd, 1896. Charles N. Hauer The enormous demand for oysters was not sustainable.The beds of the Chesapeake Bay, which supplied much of the American Midwest, were becoming rapidly depleted by the early 1890s. Increasing restrictions on oyster seasons and methods in the late 19th-century lead to the rise of oyster pirates, culminating in the Oyster Wars of the Chesapeake Bay that pitted poachers against armed law enforcement authorities of Virginia and Maryland (dubbed the "oyster navy"). In 1883, an understudy of Charles E. Haller, named Charles N. Hauer, took charge of the Haller Dining Rooms establishment at Church and Market when his boss relocated to the Green House a few blocks to the south. This was quite an opportunity for Hauer, a distant relative of Frederick's famed heroine, Barbara (Hauer) Fritchie. Just a few years prior he found himself a cigar maker, along with his brother, Fritchie Hauer. Their father was a cigar-maker. Charles Nicholas Haller was born October 5th, 1859, the son of George N. and Lucretia (Poole) Hauer. He was one of nine children and spent most of his life living on South Market Street. He got the chance to learn the business from a great teacher, Charles E. Haller. Now at the helm, he took the opportunity to re-use the name of "Gem Restaurant" for the restaurant on the corner of Church and Market streets. Charles continued to run The Gem for years at this locale. He married Clara Filby in 1887, but the couple had no children. Charles would really experience a strange degree of fame in the form of a medical testimonial he would give for Hood's Sarsaparilla in the year 1892. His face would appear in newspapers coast to coast. The following ad appeared in the March 2nd edition of the Philadelphia Times. Perhaps if one had bad blood, the tempting intake of raw oysters and alcohol, readily available at work, may not have been the best career choice. But what do I know? Charles would eventually leave the Gem to take a job at the establishment on West Patrick earlier mentioned and named European House. Ironically, this was the original "Gem" location for those keeping score at home. Actually, the City Hotel next door would receive a makeover under new ownership after the death of Frank B. Carlin. It became the New City Hotel. The European changed hands as well and would come to be known as "The Buffalo Hotel and Restaurant." Wisely, Charles Hauer soon brought in his mentor with like name to help him manage the new venture. Mr. Charles E. Haller moved into retirement in 1899, leaving Charles N. Hauer to make a name for himself. The world was clearly his oyster, or buffalo, take your pick. Mr. Hauer was at the top of the oyster heap at the start of 1901. The Buffalo restaurant was roaring and the "Roaring Twenties" were still a few decades away. Unfortunately, Hood's Sasparilla would not be a sure-fire cured for what "ill-ed" Charles N. Hauer. He would pass on March 10th, 1901 at the age of 41. His death certificate in our cemetery files gives pneumonia as cause of death. He would be buried two days later in Area L/Lot 82. His gravesite can be found directly behind the Key Memorial Chapel. Just look for the sizeable monument with the BPOE Elks symbol on it, as Hauer's widow (Clara) would remarry a man (William Myers) belonging to the fraternal order, and proud of the fact, I might add.  Oyster boats in Baltimore Harbor Oyster boats in Baltimore Harbor Nowadays, tavern food has expanded to things such as hamburgers, nachos, hot wings, and mozzarella sticks. But hail to the bivalves! Raw bar items such as oysters, mussels and clams, along with decapod crustaceans in the form of steamed shrimp, are a special treat, and go incredibly perfect with beer any day of the week, and twice on Sundays. Frederick has continued to welcome oyster establishments and retail sales since the bawdy 19th century and height of the "oyster craze." The mollusk can be found at a multitude of restaurants throughout Frederick City and county and serve them up in a variety of ways. On top of that, oyster fritters are still a delicacy sold as fundraisers by groups ranging from churches to fire companies. As I said earlier, firemen love oysters! Ironically, my last "meal out" was the night before the mandatory quarantine of dining in restaurants went into effect. I enjoyed a fried oyster dinner at Callahans. Now that was a heavenly "final supper" so to speak—I wouldn't have traded it for anything.

1 Comment

Nancy Droneburg

5/8/2020 12:24:27 pm

You notice all these people died before the age of 50. Could it have been the oysters! Great stories.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed