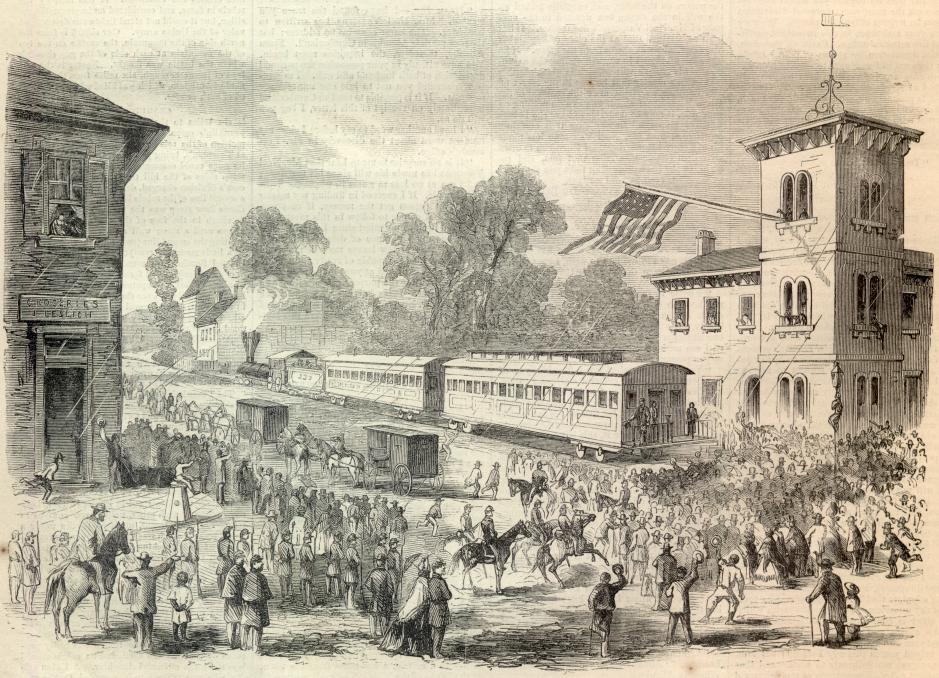

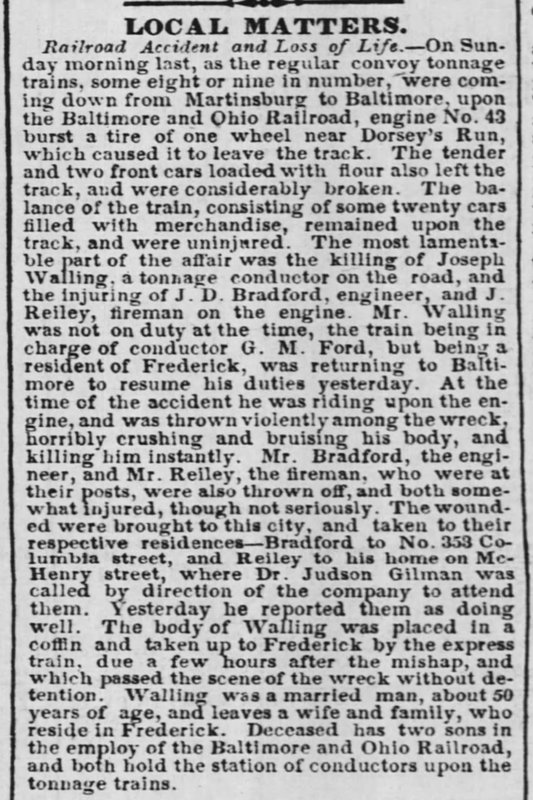

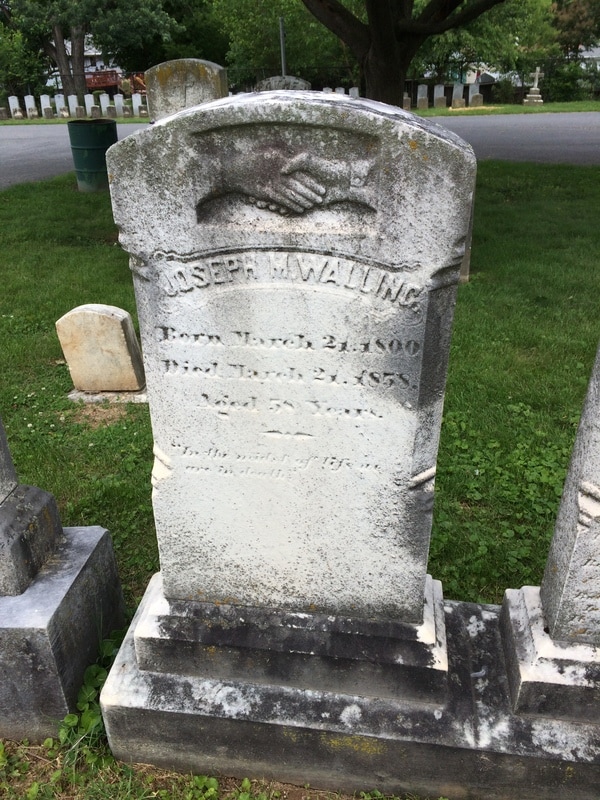

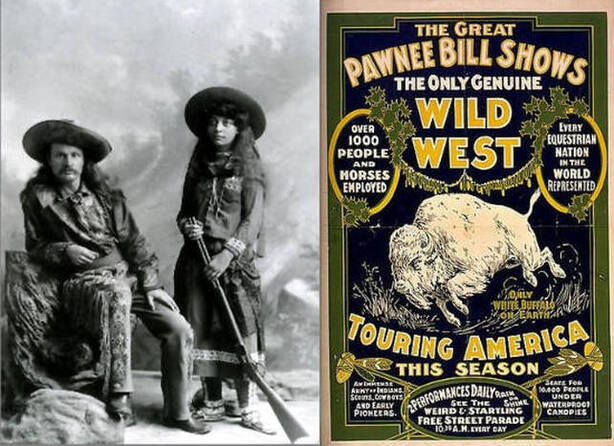

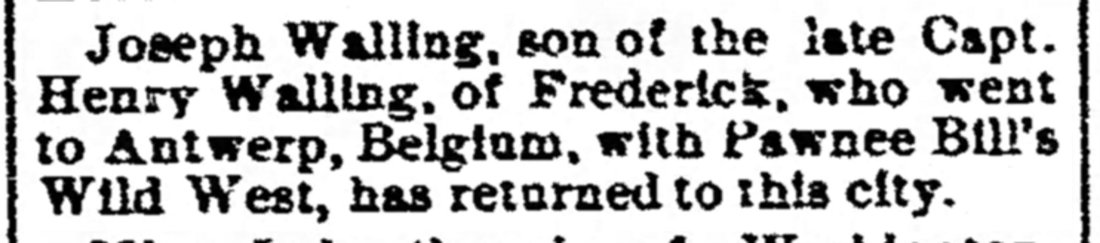

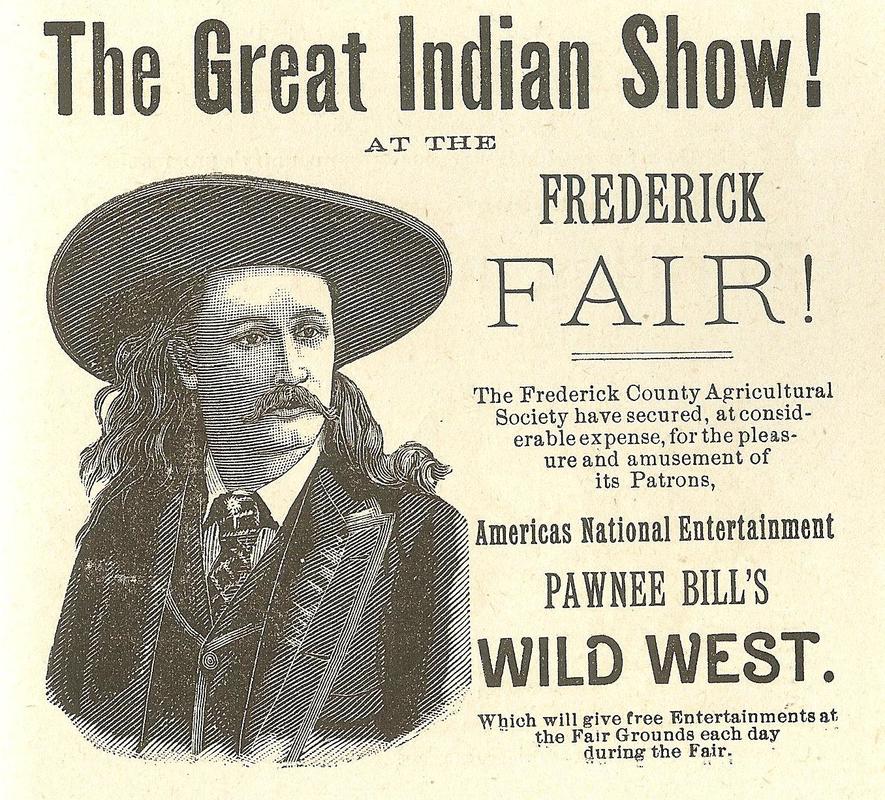

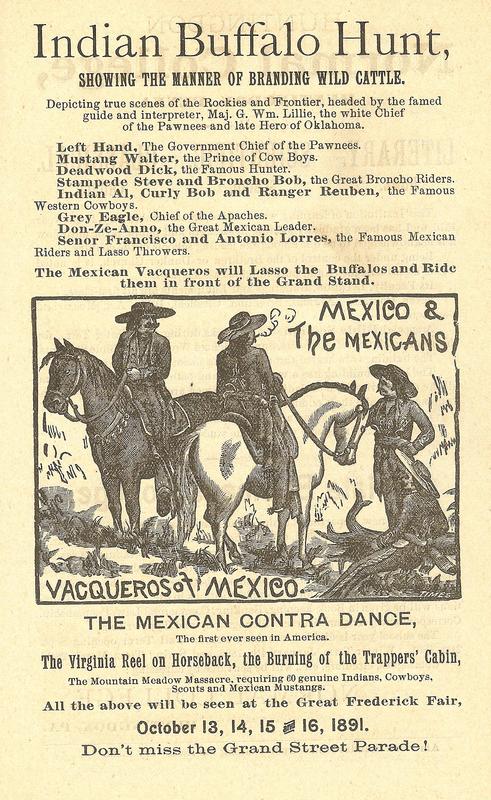

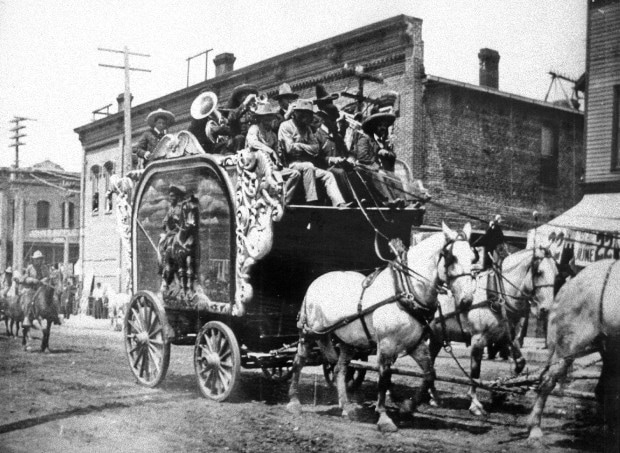

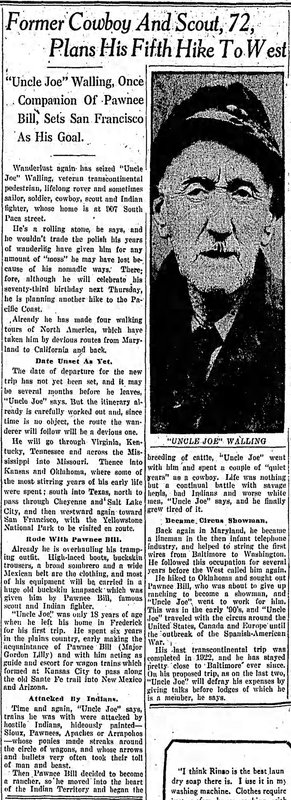

Horace L. Greeley (1811-1872) Horace L. Greeley (1811-1872) How did the concept of Manifest Destiny play to Frederick residents just three months after the close of the American Civil War? On July 13th, 1865, Horace Greeley, Editor of the New York Tribune newspaper, wrote an editorial promoting the Homestead Act which President Lincoln had signed earlier on May 20th, 1862. Young men working in Washington D.C. had complained about the cost of living and the low wages paid by the government. Greeley wrote: “Washington is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.” One young man was just too darn young to act on any impulse in 1865—but years later he would, multiple times. Eleven-year old Joseph Walling knew little of the world outside of his hometown, but appreciated the modes of travel afforded local residents wanting to see more of the country that had just been preserved by the recent four-year conflict. The young man’s father (Capt. Henry Jefferson Walling) was a popular passenger conductor for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, making trips to Charm City and elsewhere on a daily basis. Joe Walling would also understand the dangers involved in travel as well. His grandfather and namesake, Joseph M. Walling, was also an employee of the mighty B&O. He was tragically killed in a railroad derailment accident in March, 1858. Maybe travel was just in Joe Walling’s blood, and his childhood exposure to the carnage of the Civil War simply made him numb to danger? This can be hypothesized because Walling’s long-“road” ahead would be defined by two things: westward travel and engaging in risky professions and hobbies. Joseph Henry Jefferson Walling was born September 21st, 1853 in Frederick, Maryland. His family lived in a two story dwelling on East All Saints Street, located between the B&O Railroad Depot to the east, and the B&O Passenger Station to the west. "Joe" was five when his grandfather lost his life heading to work one day en-route to Baltimore. At eight, the American Civil War erupted, and Frederick would be visited by both major armies, North and South. Throughout the duration, wounded, sick and dying soldiers could be easily seen as they were brought for care to Frederick’s “one-vast hospital.”  The Walling family residence can be seen in this wartime sketch depicting the October 4, 1862 visit of Abraham Lincoln to Frederick which appeared in Harpers Weekly magazine. This is the old B&O Passenger Station located at the southeast corner of E. All Saints and S. market streets. The two-story Walling home appears on the south side of All Saints Street (just beyond the locomotive)  Wagon train on the Santa Fe Trail Wagon train on the Santa Fe Trail At 15, Joe followed in a first responder role, shared with both his father and grandfather as he joined the United Fire Company. He would spend the next 75 years in service to various fire companies, one day earning the moniker as “the oldest volunteer firefighter in the United States.” In 1871, Joe made his first big move and took up residence in Baltimore and worked for the railroad. Shortly thereafter, he earned a job as an Indian scout, guide and escort assisting wagon trains delivering shipments from Kansas City to points in the “Wild West.” Most of these were along the famed Santa Fe Trail, taking him to New Mexico and Arizona. He lived in the plains country for six years between 1872-1878. In between trips, he had proposed to the love of his life, Laura Staley. The couple married in 1876, but the life change didn’t seem to slow down Joe Walling one bit, as he would have plenty of stories to tell in the future of his western experiences. Nearly 70 years later, a newspaper writer of the Frederick News would write of Joe: “He could describe the markings painted on the faces of the Apaches and the sound of their battle cries as they attacked the wagon trains. He knew the Pawnee, the Arapahoes and the Sioux. Many a time their ponies streaked in lightning circles around the massed covered-wagons he protected, and he swapped bullets with the best of them.” Joe next ventured into the heart of Indian Territory (Oklahoma Territory) and became a bona-fide cowboy. For two years (1879-1880) he would ride the range, keeping a lookout for cattle rustlers and other unsavory men of the Old West. It was here that he met a young adventurer much like himself and named Gordon William Lillie. Lillie would later become a well-known American showman and performer under the name Pawnee Bill. He and wife May, a female marksman in the style of Annie Oakley, specialized in Wild West shows, including a short partnership with Maj. William F. Cody—Buffalo Bill. By June of 1880, Joe was back east in Frederick with wife Laura and son Henry Jefferson, who were living with Joe’s parents and grandmother in the family home on E. All Saints Street. He gained employment again with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad as a brakeman. The job of the freight train brakeman was a solitary one and was especially dangerous. Before the widespread use of airbrakes in the late 19th century, trains were stopped through the manual application of brakes on each of the train’s cars. Even after the airbrake came into universal use, the brakeman still had to be ready to climb atop the train to manually set the brakes when the airbrakes failed to work or when a section of cars had to be cut from the train. In the interest of train safety, the middle brakeman, if there was one, would ride out in the open in order to be ready to manually apply the brakes if the need arose. Middle brakemen were most frequently used on long freight trains as well as on local freight lines where freight cars had to be cut loose or added on regularly.

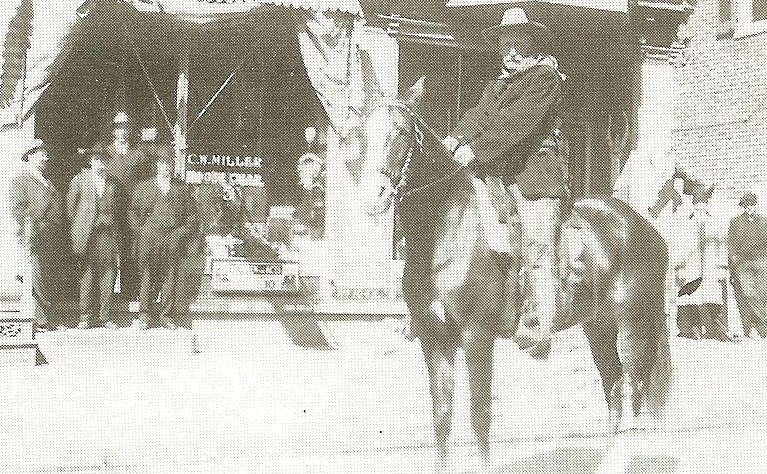

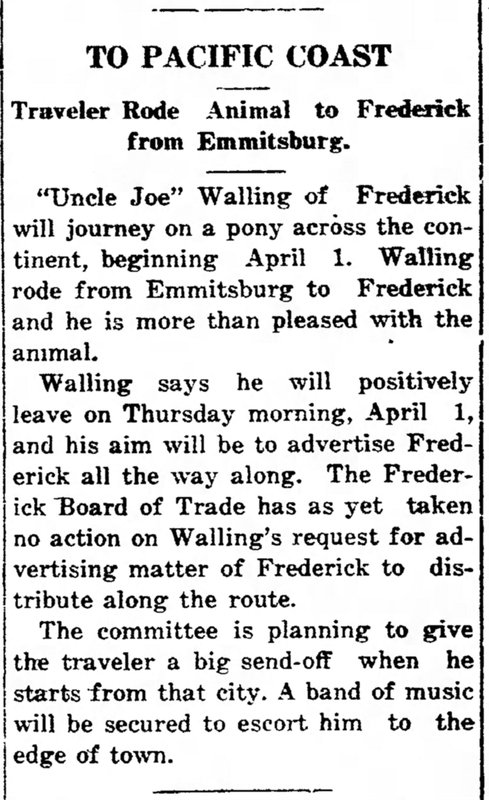

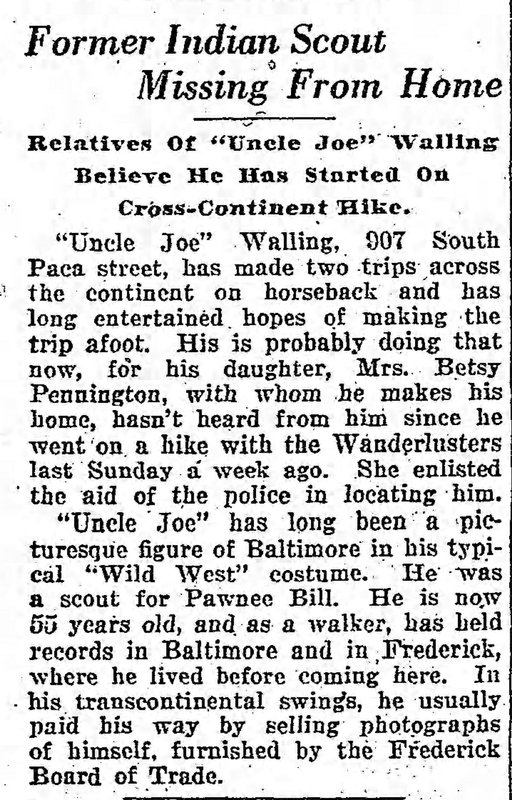

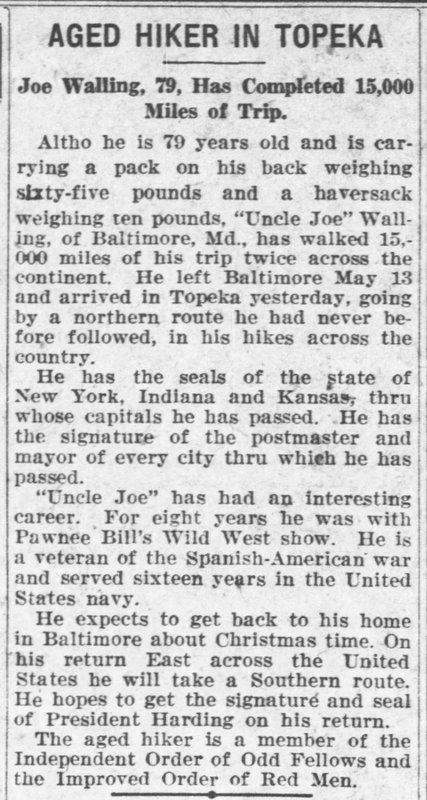

One month later, Joe Walling would experience another tragic event with the death of wife Laura. His four children were grown, but the pain was no less. He took up residence with his daughter Betty Pennington, and lived under her roof at 907 S. Paca Street in Baltimore, only a few blocks west of the current day sports stadium complex of Camden Yards and M&T Bank Stadium. Joe Walling’s personal storytelling ability to family and friends was legendary. He had a welcome invitation to visit and “conduct court” at a plethora of fire houses across Charm City. This is likely how he earned the nickname of “Uncle Joe.” Joe needed something to fill his desire for travel and danger. He was working for a Baltimore ironworks at this time, and his chief hobby was that of a member of the Baltimore Wanderlust Club, an organization that conducted hiking outings. Joe loved this group and regularly walked long distances to towns across the region, including many trips to and from Frederick on foot. As Joe was trying to fill the major void created in his life following the loss of Laura, he decided to head west once again, as he had done in his youth. However, he wasn’t going to stay out west, he just wanted to visit, and come back to Maryland. In 1910, Joe embarked on the first of five known transcontinental trips he would attempt over the next 22 years. To San Francisco and back on foot was “Uncle Joe’s” first major feat. It also brought him notoriety and standing as one of the state’s most colorful characters. In 1915, Joe Walling planned another transcontinental trip, but this time aboard a pony. Escorted by policemen and drum corps, Joe set out on his journey from Frederick on April 1st. Unfortunately, the trek had to be aborted later in the month. After traveling 300 miles, the 62 year-old rider was thrown from his mount near Wheeling, WV. He suffered a broken leg but remained in good spirits, determined to try again in the spring of 1916.

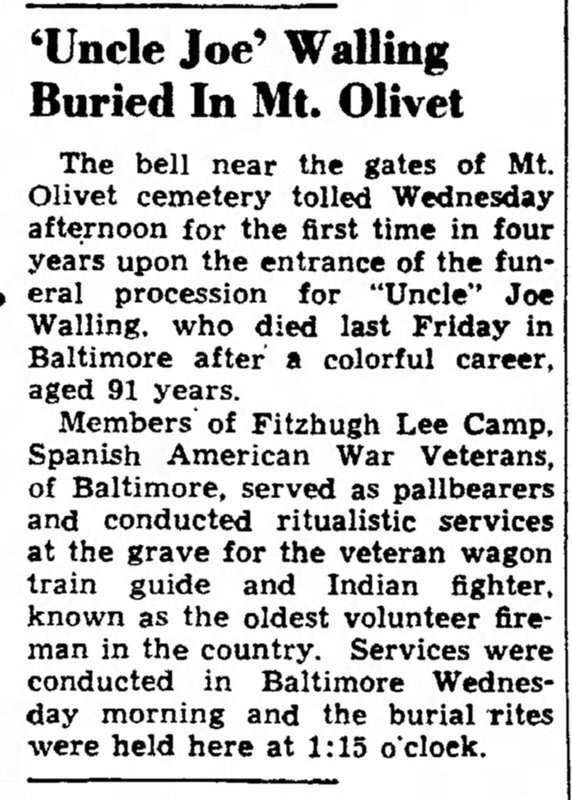

In his eighties, he would continue to walk all over Baltimore, but would not attempt another cross-country sojourn. His last decade of life found Uncle Joe in the familiar role as raconteur as he told the tales of a storied life, full of adventure, duty to others, travel and the romance of the famed “Wild West.” Joseph J. Walling died quietly in Baltimore on July 2nd, 1944 at the age of 91. The “old warrior” made one last trip west to his native Frederick, where he would be laid to rest in the family plot in Mount Olivet Cemetery. He would take his place next to wife Laura, with his parents and grandparents close at hand. His monument reads:

“Here he lies where he longed to be. Home is the sailor, home from the sea.”

2 Comments

Charles Thomas

6/6/2017 10:49:34 am

Love your articles and find them very interesting in knowing more about the folks buried in Mount Olivet and the history of Frederick. Maryland

Reply

John Simpson

6/6/2017 09:47:29 pm

In poolsville md there is a road name Ed Dr Walling any relation to the above article. Good article, enjoyed reading it

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed