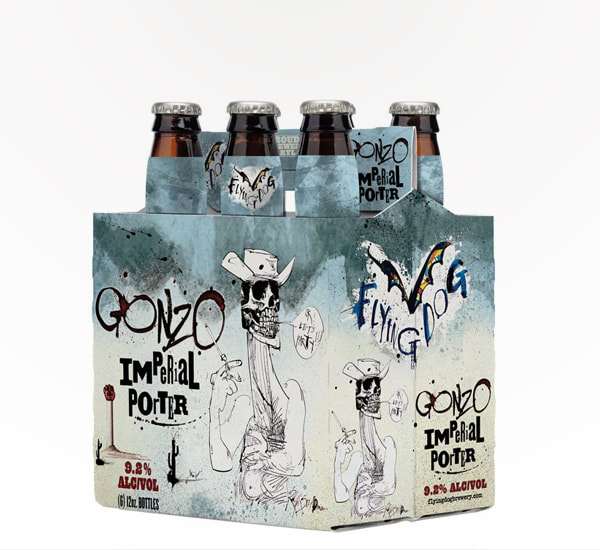

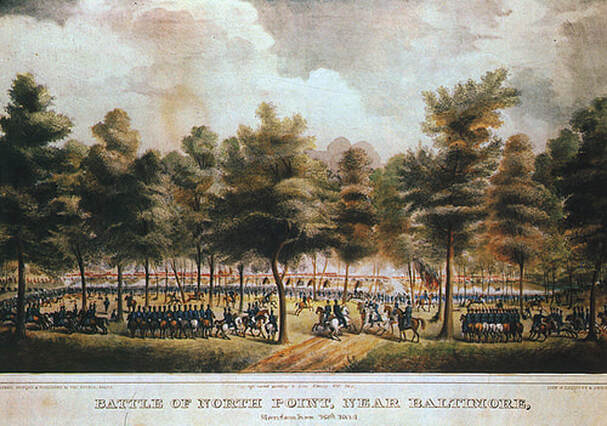

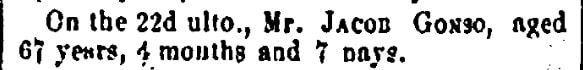

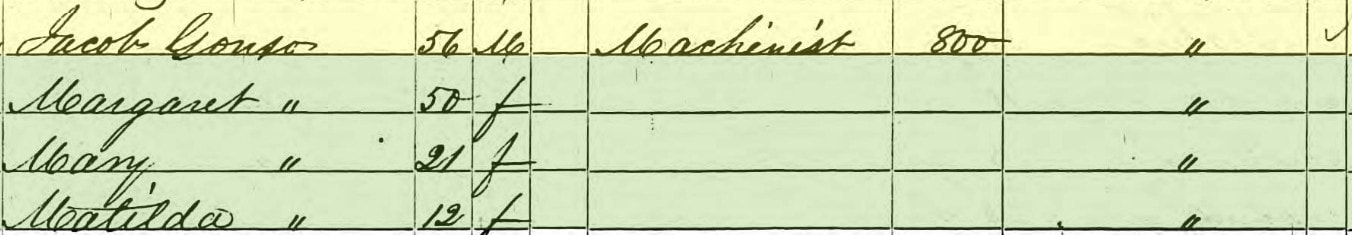

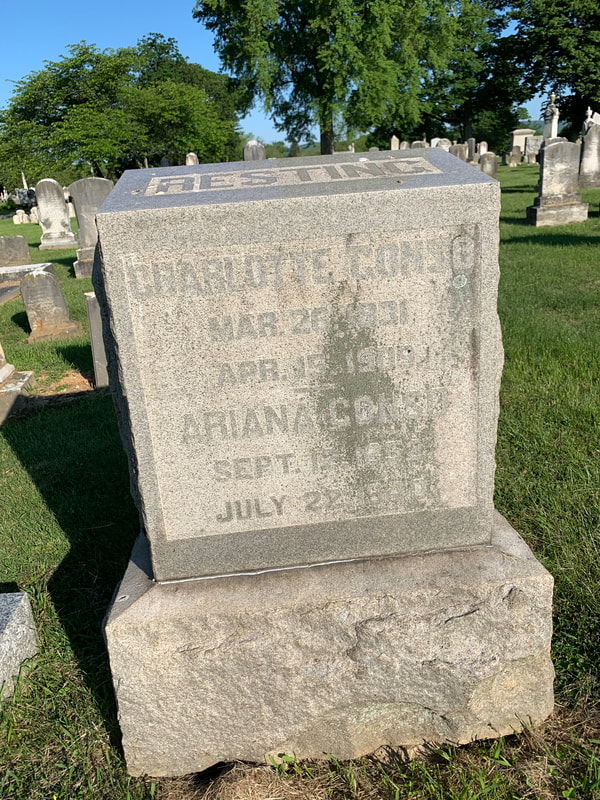

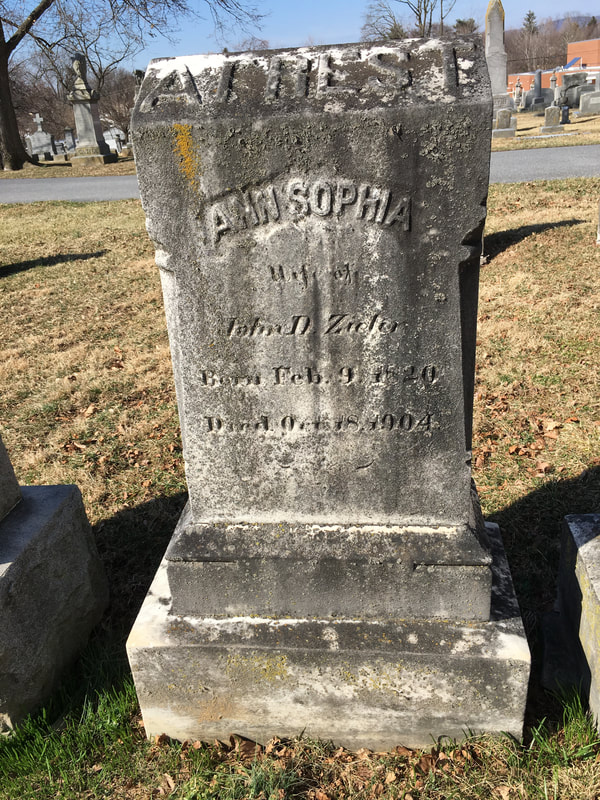

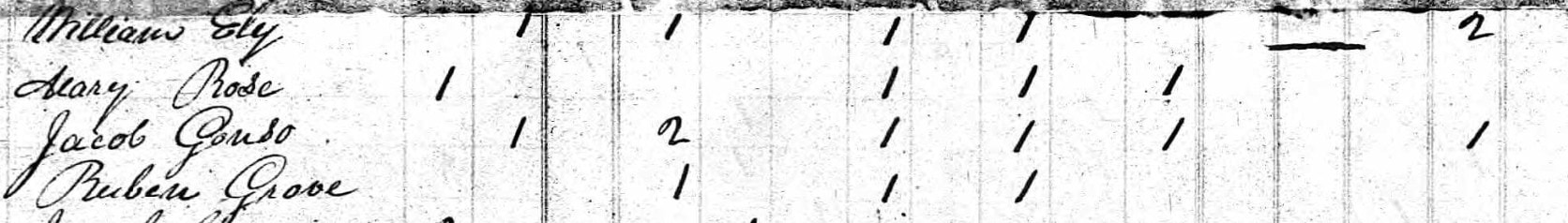

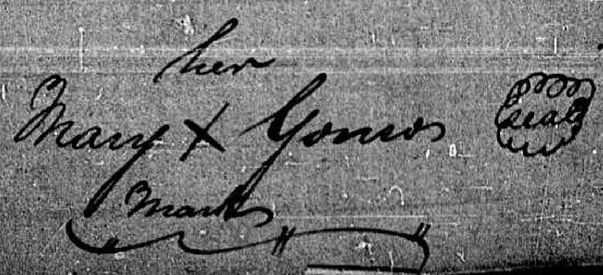

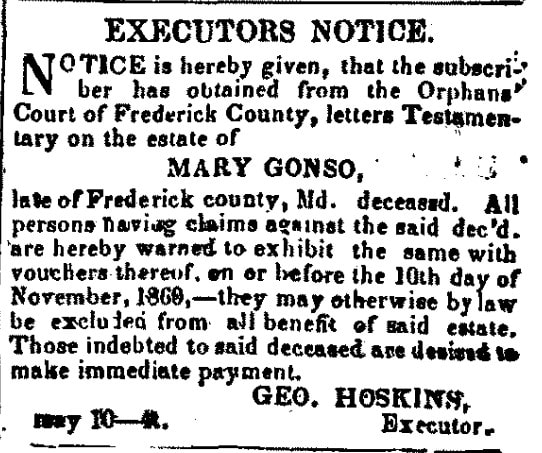

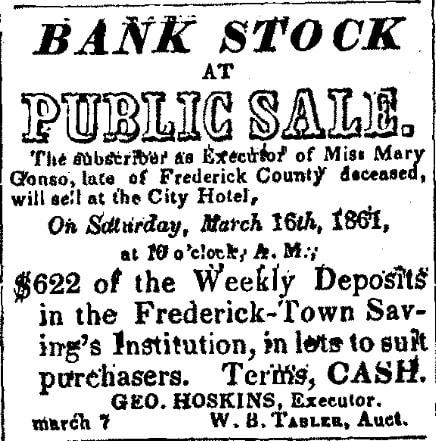

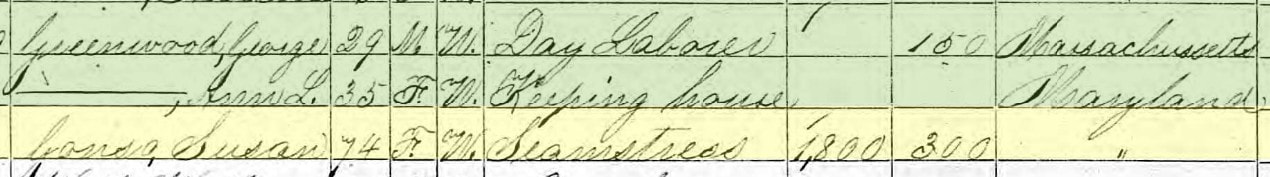

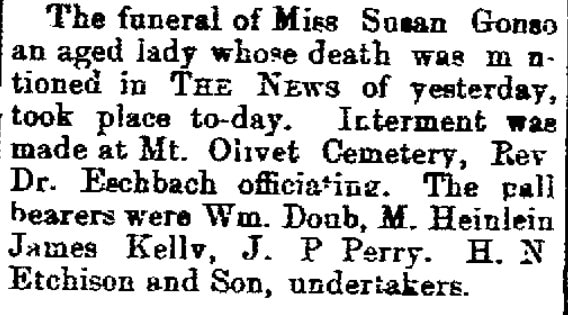

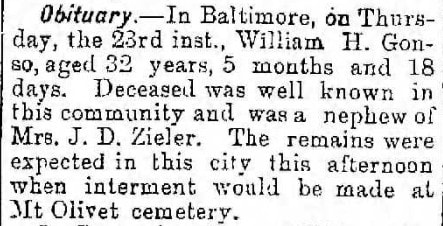

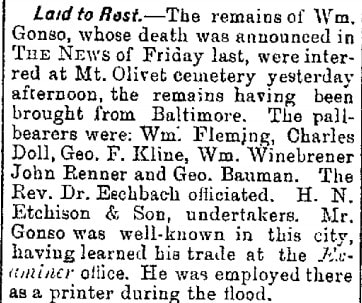

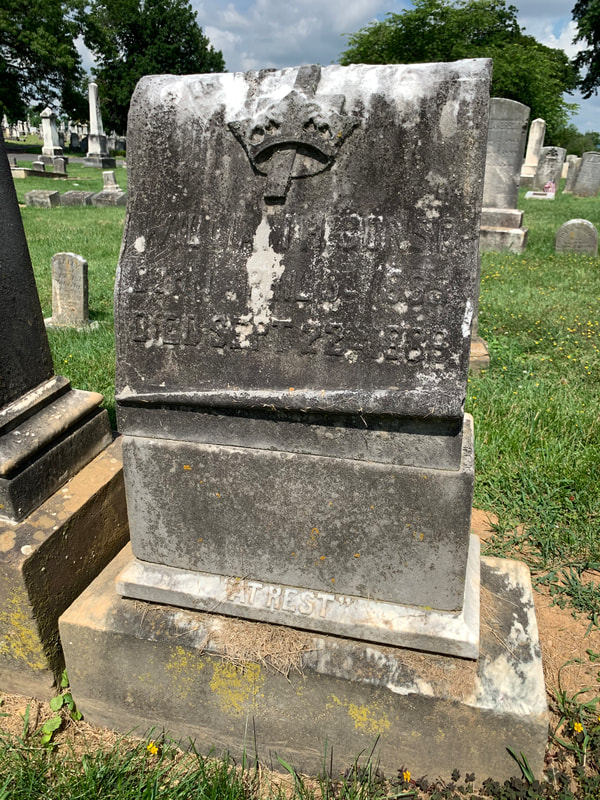

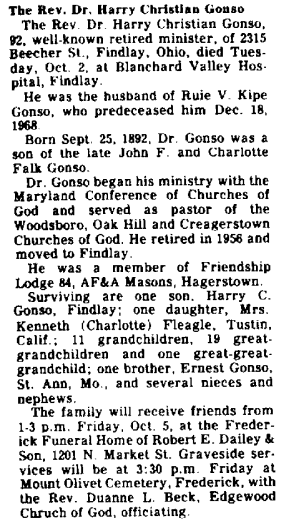

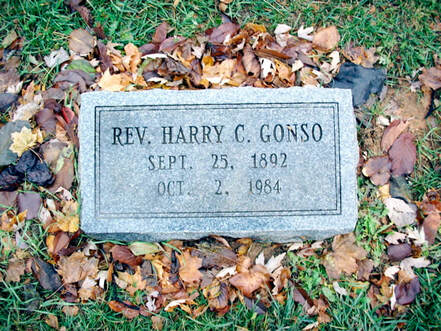

"Gonzo the Great" "Gonzo the Great" “Bizarre, unrestrained, or extravagant, usually used to describe a style of personal journalism.” That is what one will find when they seek the definition of the word “gonzo.” I can’t help but to have the image in mind of the famous cast member of Jim Henson’s Muppet Show—Gonzo, also known as "The Great Gonzo" or "Gonzo the Great," is known for his eccentric passion for stunt performance. Aside from his trademark enthusiasm for performance art, another defining trait of Gonzo the muppet is the ambiguity of his species, which has become a running gag in the franchise. Back to Gonzo journalism, this is a style that is written without claims of objectivity, often including the reporter/author as the story’s protagonist using a first-person narrative and it draws its power from a combination of social critique and self-satire. Gonzo journalism disregards the “strictly-edited” product favored by newspaper media and strives for a more personal approach commonly using sarcasm, humor, exaggeration, and profanity. The word "gonzo" is believed to have been first used in 1970 to describe an article about the Kentucky Derby by Hunter S. Thompson, who popularized the style. Mr. Thompson, a truly unique individual not all that different than Gonzo the muppet, may never have visited Frederick, Maryland during his lifetime (1937-2005), but certainly is linked through an affiliation with Flying Dog Beer, a popular craft offering brewed right here in the town of “clustered spires” since 2006. Author Hunter S. Thompson lived a few blocks from beer founder George Stranahan's Flying Dog Ranch in Woody Creek, Colorado. The two became good friends over common interests in drinking and firearms. In 1990, Thompson introduced Stranahan to Ralph Steadman, who went on to create original artwork for Flying Dog's beer labels in 1995. His first label artwork was for the Road Dog Porter, a beer inspired and blessed by Thompson who wrote a short essay about it titled "Ale According to Hunter.” In 2005, the brewery created a new beer in Thompson's honor, Gonzo Imperial Porter. One of the more peculiar surnames that I have seen in my exploration of Mount Olivet is Gonso, not quite Gonzo, but about as close as you can get. This piqued my curiosity, so I decided to explore the matter to find if this family could be described (according to the above-mentioned definition) as bizarre, unrestrained or perhaps extravagant? Although a long shot, could any of these folks be connected to journalism? I found 17 individuals holding this family surname buried here. I was most interested in exploring the earliest of these to hopefully find the origin of the name. I didn’t have to look far as I recalled a Jacob Gonso who served in the War of 1812. We had placed a special marker on this gentleman’s grave as part of our “Home of the Brave” project in which the burial sites of 108 like vets of this oft-misunderstood war were recognized with monuments, flags and a luminary ceremony that took place September 13th/14th, 2014. This was the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Fort McHenry, a momentous event that caused our most famous resident, Francis Scott Key, to write the “Star-Spangled Banner. Jacob Gonso served under Col. John Brengle in the 1st Regiment, Maryland Militia from August 25th to September 19th, 1814. He was among the 73 men hastily recruited by Brengle and Rev. David F. Schaeffer (1787-1837), then the acting minister of the town’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. We can get a feel for the mood of the day from an account from our esteemed resident/diarist Jacob Engelbrecht, merely a teenager at the time. Engelbrecht’s description would not be recorded until 42 years later (June of 1856), but still provides documented proof of a unique happenstance involving Rev. Schaeffer: “War of 1812. The following is the Muster Roll (copy) of Captain John Brengle’s Company of Volunteers, which Company was raised in four hours, by marching through the streets of Frederick, August 25, 1814, (the day after the Battle of Bladensburg, on which day we received the news) headed by Captain Brengle & by the side, with them, rode the Reverend David F. Schaeffer, encouraging the men to volunteer…” Engelbrecht proceeded to name all the men who joined up that day, including a John Gonso listed immediately before Jacob Gonso’s name. This is certainly a relation, but was John a brother, cousin or possibly a father? We will answer that in a minute.  Brengle’s Company, with Privates Jacob and John Gonso in tow, fought bravely at the entrenchments of the Battle of North Point. The Battle of North Point was fought on September 12th, 1814, between Gen. John Stricker's Maryland Militia and a British force led by Major Gen. Robert Ross. History accounts say of the battle: Although the Americans retreated, they were able to do so in good order having inflicted significant casualties on the British, killing one of the commanders of the invading force, significantly demoralizing the troops under his command and leaving some of his units lost among woods and swampy creeks, with others in confusion. This combination prompted British colonel Arthur Brooke to delay his advance against Baltimore, buying valuable time to properly prepare for the defense of the city as Stricker retreated back to the main defenses to bolster the existing force. The engagement was a part of the larger Battle of Baltimore, an American victory in the War of 1812. Jacob, John and colleagues would receive a hero’s welcome back in Frederick on September 21st, 1814. Two centuries later, Mount Olivet Cemetery pulled together a volunteer group of its own to conduct research on local 1812 vets in order to place the special, commemorative monuments. Biographies were researched and written by Larry Bishop and Ron Pearcey, and these appear in a book titled Frederick’s Other City: War of 1812 Veterans. On page 54, one will find the scant offering on Jacob Gonzo with information pointing to the name also appearing as Ganzau and Gonze in past written records. Jacob Gonso/Ganzau was born February 15th, 1795 in Maryland to parents who, at the time of the book's writing, were unknown to the authors. He was married at the age of 21 by Rev. David F. Schaeffer of the Lutheran Church in Frederick Town to Margaret Keller on September 5th, 1819. According to his obituary, Jacob Gonso died in Frederick on June 22nd, 1862 at the age of 67 years, 4 months and 7 days. Margaret was born about 1800 in Maryland, and died October 17th, 1867. She was laid to rest in Mount Olivet in Lot 52 of Area B. Jacob’s remains were removed from the Lutheran graveyard and placed beside her 27 days later. According to the 1850 Census, Jacob was a machinist with $800 in value of real estate owned. He can be found living with his wife and two children, Mary and Matilda. Research conducted shows he owned the property located between Market Street and Middle Alley at 17 East Fifth Street from 1839 until his heirs sold it in 1866. Jacob and Margaret Gonso had six known children: Ann Sophia Gonso (1820-1904) married John David Zieler; William Henry Gonso (1822-1865) married Louisa M. Stevens; Mary Elizabeth Gonso (1827-1893) married Isaac Philip Suman; Charlotte Keller Gonso (1831-1909) never married; Charles Jacob Gonso (1835-unknown); and Catherine Matilda Gonso (1839-1920) married William Amos Scott. Interestingly, Jacob, Margaret and some of their children ( Charlotte K. Gonso, Catherine M. (Gonso) Scott, and Charles J. Gonso (unmarked)) are buried in the Scott Family plot in Area B. Daughters Ann Sophia (Gonso) Zeiler and Mary Elizabeth (Gonso) Suman are buried nearby. A few other immediate family members can be found in Rocky Springs Graveyard, in the northern reaches of the city. I did locate Jacob in the census records dating back to 1820. The name was transcribed and spelled various ways which helped thwart easy efforts to obtain positive results via Ancestry.com. I didn’t find much in the local newspapers throughout his lifetime, save for a few mentions and his obituary appearing in 1862. As said earlier, Jacob Engelbrecht mentioned Jacob in his diary as being an active participant in the War of 1812. When searching real estate, my assistant Marilyn Veek didn't find any property owned by Jacob Gonzo before 1839. However, she did find that a George Gontzo owned the east half of lot 134 located between East 3rd and East 4th streets from 1798 until his heirs sold it in 1830. This turned out to be Jacob’s father, complete with a different variation on Gonso, but incorporating the “z” as discussed earlier. From this important find, the 1830 deed, George’s heirs are revealed as John Gontzo and Mary his wife, Eve (Gonso) Kieffer and husband Peter, Jacob Gontzo and Margaret his wife, Charlotte Keller, Mary Gontzo and Susannah Gontzo. Back to Engelbrecht’s diary, one can find a few early references to the name Gantsau/Ganzau which is one in the same with Gontzo and Gonso. In 1823, a three-month-old child of John Ganzau would be buried in the Evangelical German Reformed graveyard—today’s Memorial Park located at the intersection of North Bentz and West Second streets. On February 4th, 1828, Engelbrecht wrote: “Died this morning in the year of her age, Mrs. Ganzau (of East Third Street). Buried on the German Reformed graveyard.“ Mrs. Charlotte Keller, widow of Charles Keller and daughter of the late Mrs. Gantzau married Abijah Shepherd in 1835. Four years later, on February 17th, 1839, Engelbrecht penned the following: “Died yesterday in the 51st year of his age Mr. John Gantzau near Wormans Mill. Buried on the German Reformed graveyard today.” Using this information, I next went to Ancestry.com and began combing through user posted family trees. I eventually found that of George Gantzach (1754-unknown death after 1807), and also spelled "Gantzaug." Marilyn found his will (written in 1807) and filed under the name "George Gantzank." George is said to have been born in Hofgeismar, Kassel, Germany and arrived in America in 1775 as a Hessian mercenary soldier fighting for the British. He was supposedly captured at the Battle of Yorktown (VA), and was sent to Frederick and imprisoned at the Hessian Barracks that stand a few blocks north of Mount Olivet’s main gate. George Gantzach would marry a woman named Margaretha (b. 1772) and had the following children: John (1789-1839), George (1792-?); Charlotte (Gonso) Sheppard (1795-1838), Eve (Gonso) Kieffer (1795-1859), Jacob (1795-1862), Susannah/Susan (1798-1886) and Mary (1800-1860). I was very familiar with the gravestone of youngest daughter Mary Gonso as I drive directly past her stone every workday. It’s located on the main drive through the center of the cemetery and stands nearly five-foot tall. This white, marble stone in Area D reads “In Memory of Mary Gonso—Died May 2nd, 1860 Aged 59 Years, 7 Months and 15 Days.” I’ve often wondered about this woman as she has a substantial stone, but is the only person buried in this plot. I would soon learn that she was never married or have children of her own. I could not find her in any census records surprisingly. Once again, we had to glean info about her from land deeds of all things. In 1846, Mary Gonso bought the property that is now 237-239 East Church Street. She would leave it to her niece, Ann Cecelia (Gonso) Carlin, wife of hotel owner Frank B. Carlin, in her will of 1860. The property was still owned by Ann Carlin when she died in 1916, and it was sold to Gilmore Flautt in 1917. The tax records estimate a construction date of 1905, so Ann probably built the double house there. Outside of that, she remains somewhat of a mystery. She is buried in Area D/Lot 15. Mary Gonso's will includes the following language about her burial instructions: "I will and direct that my Executor purchase a Lot in Mount Olivet Cematary (sic) Company, and inter my body therein, and enclose the same, with Substantial Iron Railing and Erect Suitable Tomb Stones, such as I have directed him, at the charge of my Estate. I will and direct that One Hundred Dollars of my weekly deposits in the Fredericktown Savings Institution shall be reserved, and I do devise, & bequeath the dividends as they accrue, thereon, to be paid to the Mount Olivet Cematary (sic) Company, and such dividends be applied to keeping my lot which my Executor shall purchase, in good repair and properly attended to." In Mary's will, a provision was made for her estate to pay a surviving sibling a stipend of $18/year. I found an obituary and burial for this same woman, Jacob and Mary's older sister, Susan (Susannah) Gonso (1798-March 12th, 1886). Living until 1886, Susan would be the last surviving member from George Gantzach's immediate family. I could not find her, however, in our cemetery records. No tombstone exists either as no one stepped forward to do so, she having no children of her own. Susan would most likely have been buried in either Mary or Jacob's lots. Two other family members of note need to be brought up before we close out the article. William Henry Gonso, Jr. is buried in the Area B lot with his grandparents (Jacob and Margaret) and various aunts and uncles. He is the closest link to "Gonzo journalism" as he apparently worked for a short time at the Frederick Examiner newspaper. This is purely a stretch on my part because this man's talent was not in writing, but more blue-collar on the actual printing and fabrication side. He eventually moved to Baltimore, where he worked as a printer and also followed in the trade footsteps of his father (William Henry Gonso, Sr.) as a shoemaker. One other persons of note was Rev. Harry Christian Gonso, DDS (1892-1984). The great-great grandson of George Gantzach, great-grandson of Jacob Gonso, grandson of William Henry Gonso, Sr., and son of John Frederick Gonso can be found in Area L, Lot 132. His father worked as a blacksmith in the Yellow Springs area and lived at High Knob, now part of Gambrill State Park. The Rev. learned his father's trade at a young age, and used the images of "fire and brimstone" for saving souls on his future path as an evangelistic minister. It sure seems like something someone with a name close to gonzo should do. Well, one thing is for sure, the Gonsos, great or not, sure made a name for themselves in Frederick, Maryland dating back to George's incarceration here in the early 1780s. The anglicisation of names such as Gantzach is just one more thing that makes genealogy research so interesting, not to mention, bizarre, unrestrained, extravagant and just plain difficult at times.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed