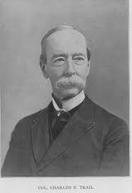

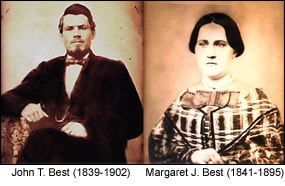

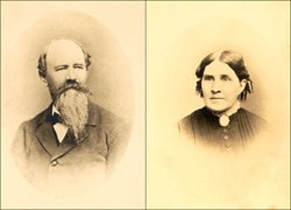

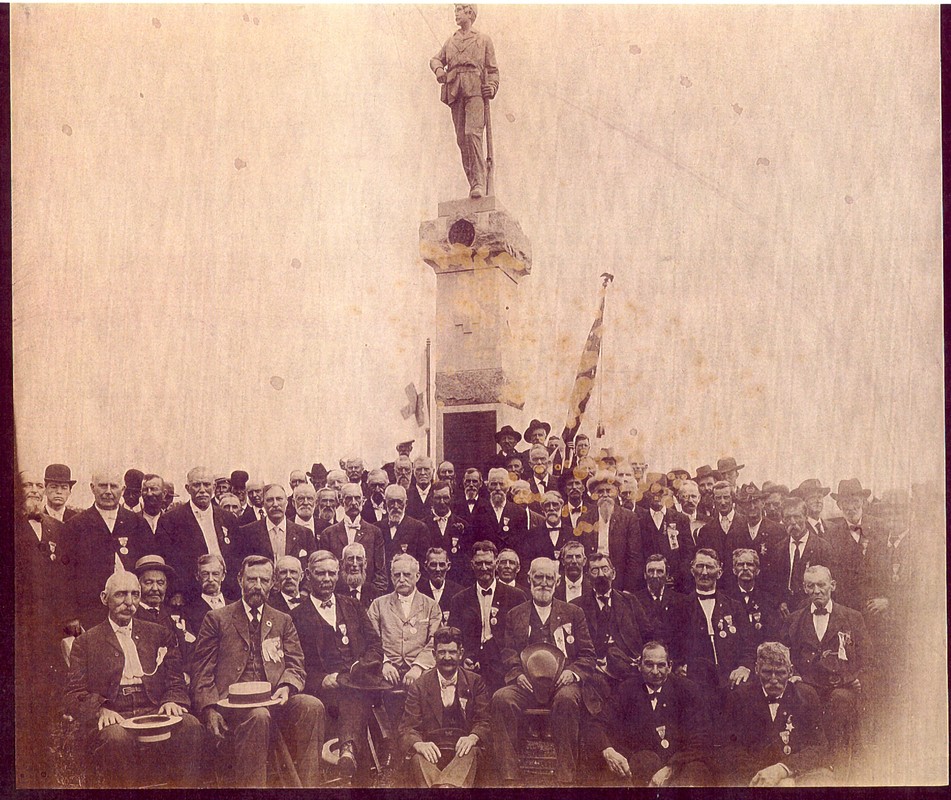

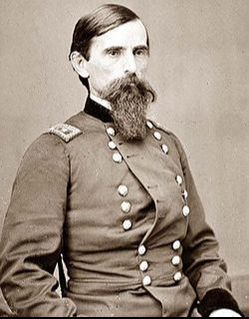

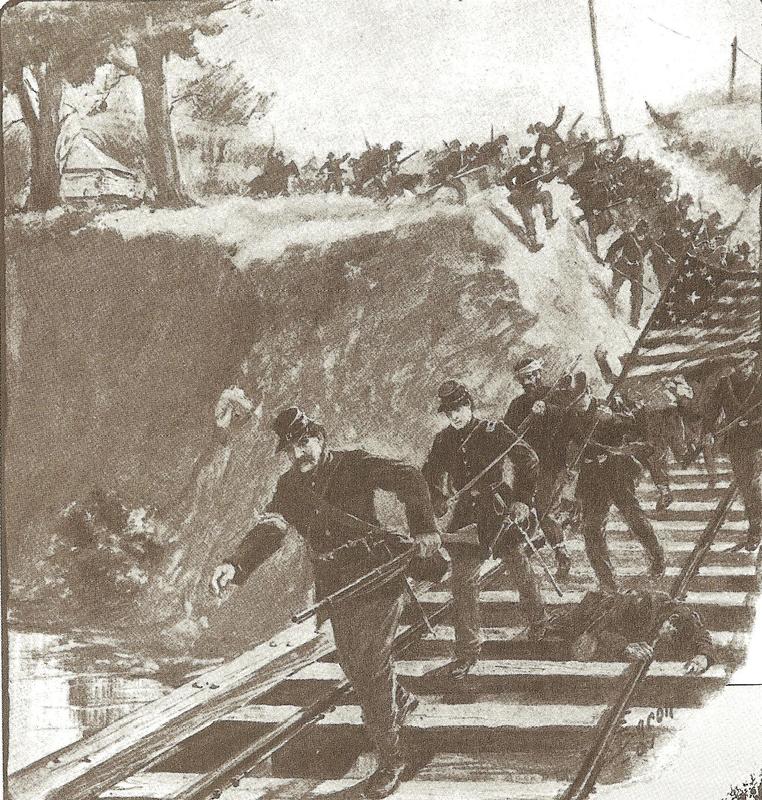

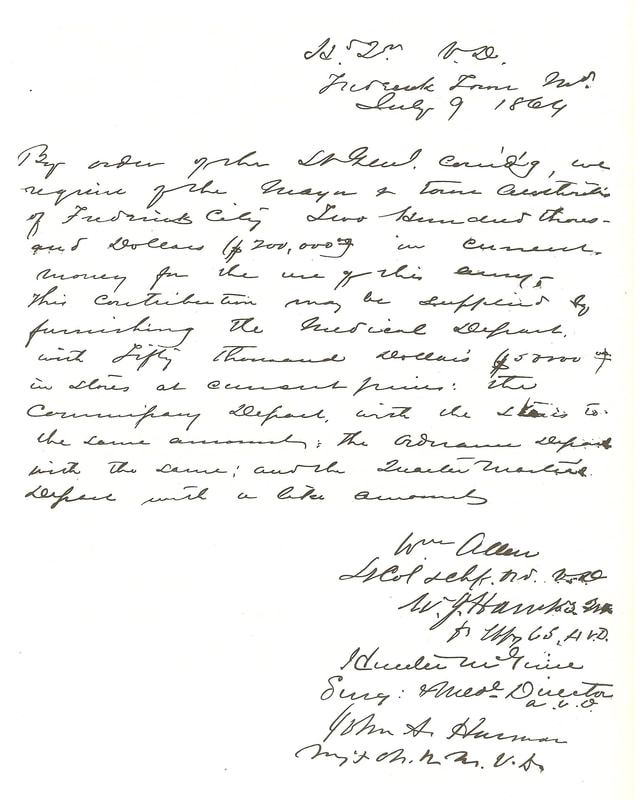

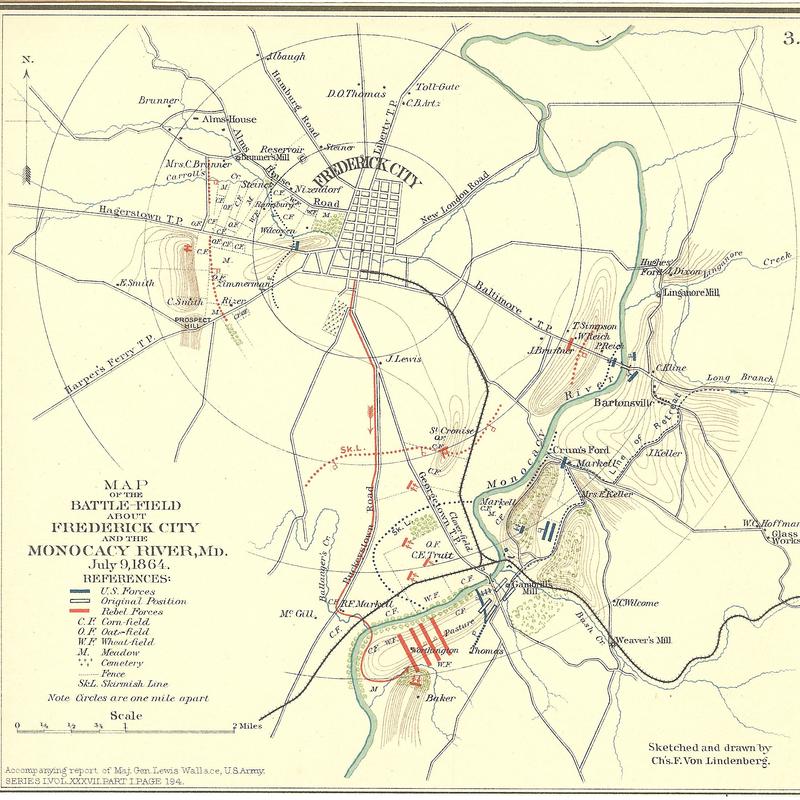

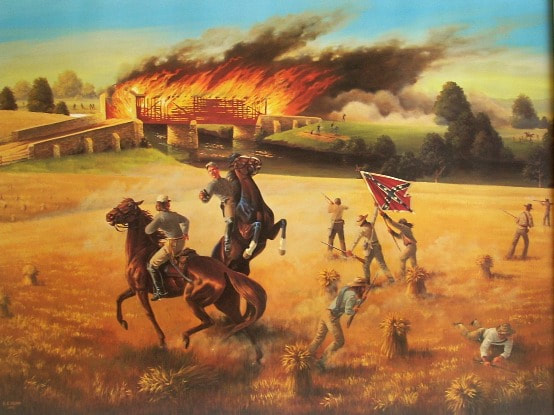

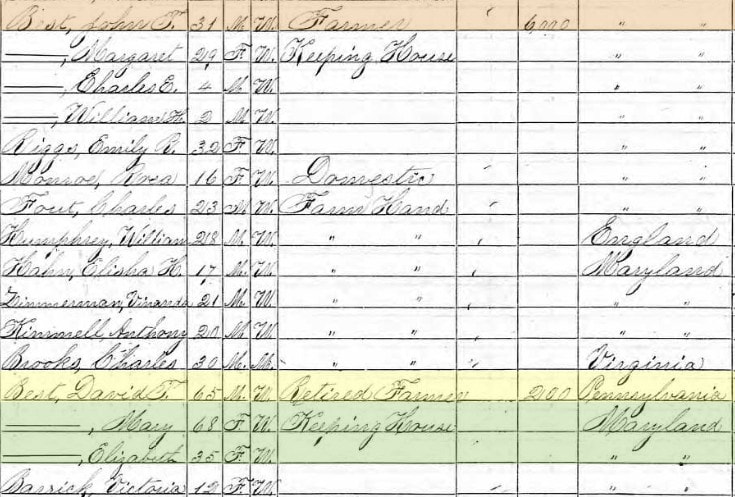

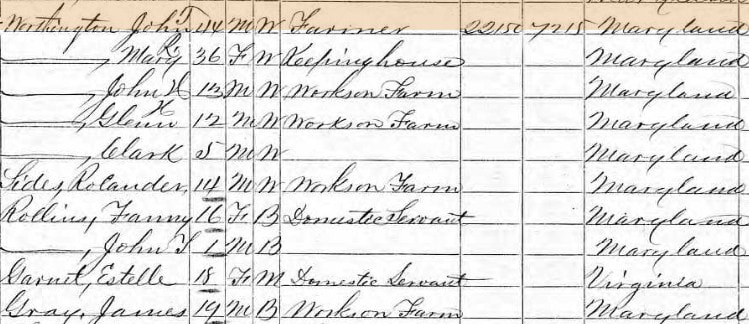

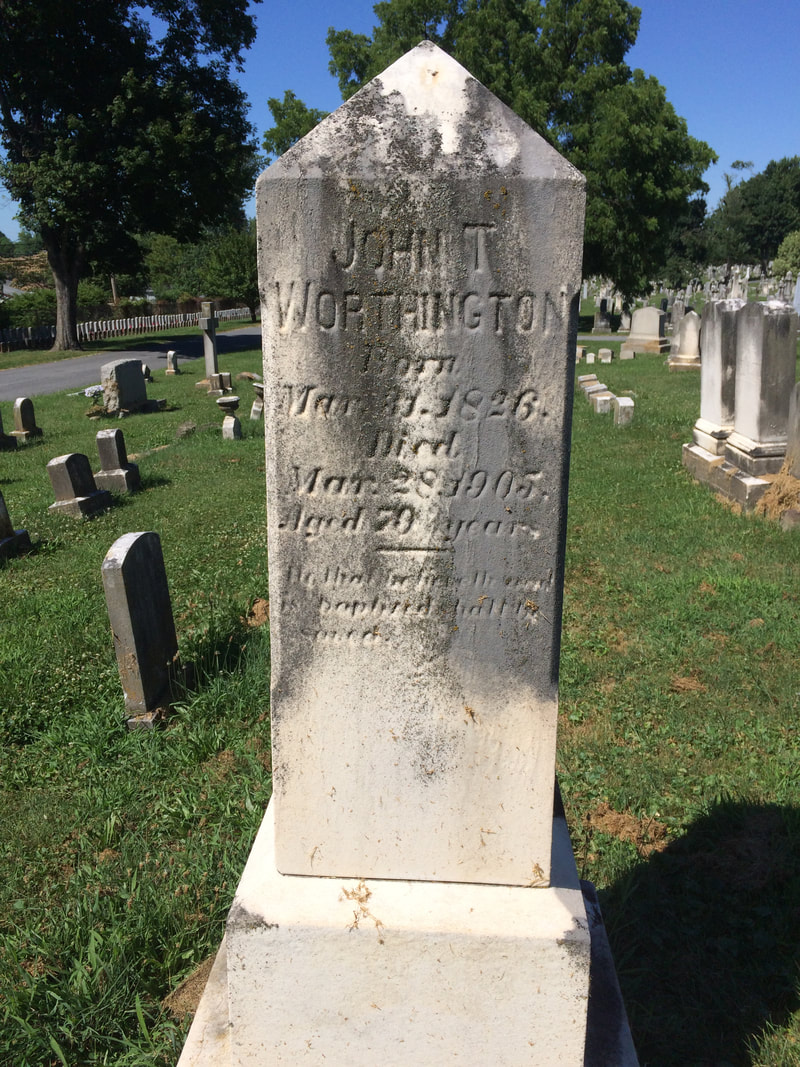

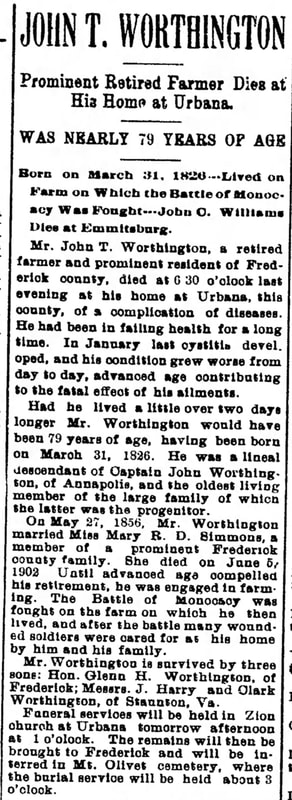

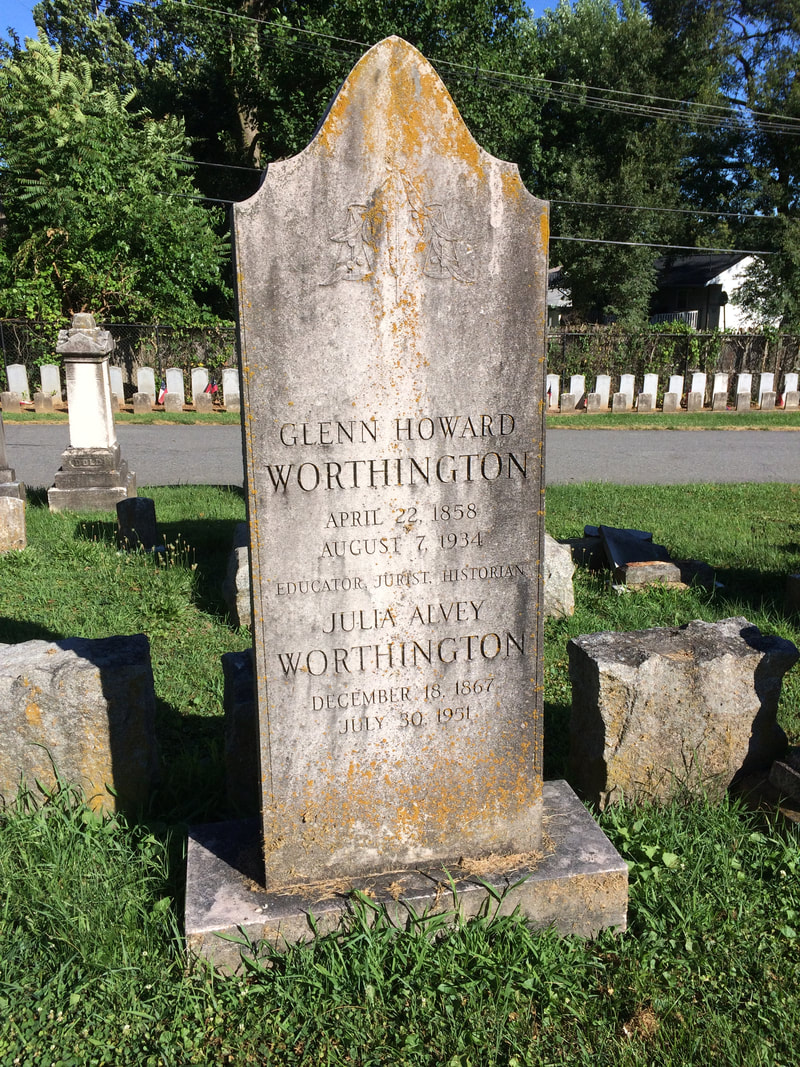

Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) “Captured again -Our old City of Frederick was captured by the Rebel forces under General Jubal Early on Saturday, July 9th forenoon or rather morning. They first entered about 6’oclock am from the west. We had no army to protect us except 2 or 3000 while the Rebels had from 10-15,000 men. General Early levied a contribution on Frederick of $200,000 which I am told was paid on Saturday. The money was got from the banks and the Corporation became responsible. About 8 o'clock AM on Saturday their wagon train commenced passing through town and it lasted 4 or 5 hours. 4 or 500 wagons must have passed. Down at the Monocacy Junction they had a battle and a goodly number were killed and wounded on both sides.” Jacob Engelbrecht July 11,1864  Monocacy National Battlefield Visitor Center (Frederick, MD) Monocacy National Battlefield Visitor Center (Frederick, MD) July 9th is the anniversary of the Battle of Monocacy, also known as “The Battle that Saved Washington, DC.” For many years now, this date continues to be commemorated at the NPS unit located a few short miles southeast of Mount Olivet Cemetery and the City of Frederick. Much of the Monocacy battlefield remained in private hands for over 100 years after the Civil War. In the decades after the battle, veterans’ organizations placed monuments and markers to specific units on the battlefield, including the 14th New Jersey (dedicated in 1907), the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, and Vermont markers. Other monuments have been added.  In 1928, Glenn H. Worthington, the owner of a large portion of the northern segment of the battlefield, petitioned Congress to create a National Military Park at Monocacy. Though the bill passed in 1934, the battlefield languished for nearly 50 years before Congress appropriated funds for land acquisition. Once funds were secured, 1,587 acres of the battlefield were acquired in the late 1970s and turned over to the National Park Service for maintenance and interpretation. The historic Thomas Farm, scene of some of the most intense fighting, was acquired by the National Park Service in 2001. Preservationists lost fights in the 1960s and 1980s when Interstate 270 was constructed and later widened, bisecting a portion of the battlefield.  Monocacy Junction Monocacy Junction One-hundred and fifty-four years ago, a very eventful week was kicked off on July 5th, 1864, when Union Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace arrived at Frederick Junction, also known as Monocacy Junction from Baltimore. The future author of Ben Hur would personally take command of the force concentrated at the railroad junction adjacent the intersection of the Old Georgetown Pike (MD 355) and the Monocacy River. By July 7th, the Union Army that had converged on Frederick totaled about 3,200 men. Wallace and his men were about to square off against Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early and a Rebel force of around 14,000. Wallace found himself commanding the only army protecting Baltimore and Washington from the Confederates. He was facing an opponent of unknown strength and intention. The Confederate Army’s presence came as a major surprise to war weary Frederick County. They had seen these men a year before in July, 1863 with the Battle of Gettysburg. Nine months earlier, Gen. Robert E. Lee had brought his Army of Northern Virginia for the Maryland Campaign and occupied Frederick for nearly a week. Soon after, the first major battles on northern soil would be fought at South Mountain (Sept. 14, 1862) and Antietam (Sept. 17th, 1862). On July 8th, Gen. Early levied his infamous ransom of $200,000 on Frederick, with the perceived threat of burning the city. Frederick’s mayor and other leaders hastily raised the money from the towns’ banks. Meanwhile, Wallace had doubled his number of union defenders to nearly 6,000 troops. The next day, July 9th, Early’s advance southward toward the nation’s capital was delayed at the Monocacy River below Frederick by the Union contingent under Maj. Gen. Wallace. Wallace knew he had very little chance of defeating Early’s veterans, but hoped to stall the Confederates in order for reinforcements to refortify Washington. In the vicinity of Monocacy Junction, a handful of families would soon find their idyllic properties turned into killing fields. A series of farms is usually talked about as encompassing what is now the Battle of Monocacy. These include the Best Farm, the Worthington Farm, the Thomas Farm, and the Gambrill Mill and Farm. All are named according to current owner (or in one case tenant) during the battle. The Confederate approach came primarily from the north via South Market Street as it doubled as the Old Georgetown Pike (MD Route 355). Many soldiers passed by Mount Olivet on their way to battle. Some of these, perhaps, would find their way back inside the cemetery’s gates as a casualty of war. The Union men were lying in wait on the south side of the Monocacy River. There would soon be an engagement at the Best Farm, the former headquarters site of generals Lee, Jackson and Longstreet during the earlier 1862 campaign. The fiercest fighting north of the river occurred to the immediate east of the Best Farm around the railroad junction area and where a covered bridge aided the Georgetown Pike in crossing the river.  The Rebels were successful in fording the river at multiple spots. Throughout the day there would be fighting between the Worthington and Thomas farms. The Union retreated back towards the Gambrill Farm, a place that had earlier received some of the first artillery shots because its proximity to the river. Fittingly, the battle concluded back on the Best Farm and resulted in the only Confederate victory in a major battle on Maryland soil. It basically took an entire day—an important day of travel that was lost to Gen. Early and the Confederates. The Rebel victors camped in this vicinity for the night, while the Federal soldiers retreated back toward Baltimore. While Early was free to march on Washington, the delay at Monocacy bought the needed time for the Union to bolster its defenses around the nation’s capital. Days later, Gen. Early would be thwarted at Fort Stevens (near present-day Silver Spring, Maryland). They now Rest in Peace We hear so much about the military officers of war, and the soldiers who did the bulk of the fighting, and dying. In most cases, these individuals made the choice to do so. As for the civilians of a place, be them in Frederick or elsewhere, the war came to them. This was not a choice that they had a say in. Battles happened with little, or no warning. In most cases, property owners lost their livelihoods, and farms that had been in the same familial hands for generations could be demolished in a day. I did a little searching around Mount Olivet to find connections to the Battle of Monocacy. Of course we have here plenty of the soldiers who participated in the battle, including those who “they here gave the last full measure of devotion” on our battleground south of town. I specifically looked for the familiar civilians linked to the farms on which the battle was fought. Monocacy Battlefield’s website, https://www.nps.gov/mono/index.htm was a huge help in garnering background on these folks.  Charles E. Trail (1826-1909) Charles E. Trail (1826-1909) The Bests The Best Farm comprises the southern 274 acres of what was originally a 748-acre plantation known as L'Hermitage, and was home to the French expatriates known as the Vincendière family. The Vincendieres sold the farm in 1827, and after several transfers of ownership it was acquired by Charles E. Trail in 1852. This was the same year that Mr. Trail and other leading citizens were in the process of establishing the Mount Olivet Cemetery Company. Trail was on the cemetery’s first Board of Directors, and was influential in getting the cemetery created in the first place. Back to the Best Farm, the Trails never occupied the farm and instead operated it as a tenant farm until it was acquired by the National Park Service in 1993. For many years during Trail's ownership, members of the Best family leased the farm, beginning with David Best and wife Anna Mary (Lantz) Best and their four children. Because of its proximity to the Georgetown Pike and Monocacy Junction, portions of both the Union and Confederate armies camped at the Best Farm throughout the Civil War.  The property included 375 acres at the time with 50 acres of wooded/unimproved land. This portion was known as “Best Grove.” This is where Gen. Lee had his camp in September, 1862. On September 13th, 1862, during the Maryland Campaign, Lee's lost order No. 191 (which outlined his army's movements) was found near the Best Farm by soldiers from the 27th Indiana. Passed up through the chain of command, the captured order gave Union Gen. George B. McClellan advance notice of his enemy's movements. In 1864, John Thomas Best (and wife Margaret J. (Dorsey) Best) took over operation of the farm from his father David. The first year of farming on his own looked promising, but soon proved disastrous. During the Battle of Monocacy, Confederate artillery set up on his farm and sharpshooters took positions in the barn. They fired at Union troops guarding the covered bridge over the Monocacy River on the Georgetown Pike. The Union returned fire, however, setting the Best's barn ablaze and destroying the grain, hay, tools, and farming implements kept there. Confederate infantry, using the farm as a staging area, soon destroyed any crops left standing in the fields. The covered bridge over the Monocacy would be destroyed as well. Undaunted by this disastrous first year, John Best continued to successfully operate the farm for many years following the Civil War. John T. and Joanna Best can be found in Area H/lot 331, adjoining that of his parents.  John T. and Mary Worthington John T. and Mary Worthington The Worthingtons John Thomas Worthington was born in 1826 into an extended Frederick County family of “prominent” farmers. John married Mary Ruth Delilah Simmons in 1856 and the couple eventually had four children, three of whom survived childhood. In 1862, Worthington purchased “Clifton Farm” adjacent to the Monocacy River, renamed it “Riverside Farm,” and settled his family into their new home. The morning of July 9th, 1864 was spent preparing for the impending battle. Hoping to minimize his loss of property, Worthington instructed the family’s slaves to gather wheat from the field, and then to take the horses to nearby Sugar Loaf Mountain and hide them in the “darkest and loneliest place you can find.” However, Confederate soldiers discovered and confiscated all nine horses, at a substantial cost to John Worthington. After the horses were hidden, the slaves busied themselves placing tubs of water in the cellar and boarding up the windows.  Depiction of Glenn Worthington watching the battle from his cellar (Keith Rocco) Depiction of Glenn Worthington watching the battle from his cellar (Keith Rocco) During the Battle of Monocacy, Confederate troops crossed the Monocacy River onto the Worthington Farm, initiating three attacks from the farm fields. Worthington and his family took refuge in the cellar, and through the boarded-up windows, six-year-old Glenn Worthington watched intently as the fighting raged in front of the house. In his memoir Fighting For Time, Glenn Worthington recalls that, “Glimpses of blue could be seen as they passed windows. More than one received his death wound close to the house and fell there to die, in Worthington yard.” After the battle, John Worthington and his family assisted with the care of the wounded soldiers. Glenn and his seven-year-old brother Harry were sent into the nearby fields to gather sheaves of wheat for use as a bed for a wounded Confederate soldier. While the wounded were being cared for, other Confederate soldiers gathered the muskets that had been thrown away by the retreating Union soldiers. The muskets were placed in a pile in Worthington’s back yard and set on fire, leaving only the gun barrels and bayonets. Glenn desired one of these bayonets as a souvenir. He procured a stick and began to drag the bayonet from the embers, and as he stooped to retrieve his prize, an ember touched a discarded paper cartridge which exploded in his face. A Confederate soldier carried him, blinded and yelling, into the house. Luckily Glenn’s eyesight was not damaged by the explosion and he made a full recovery. After the Civil War, John Worthington continued to be a successful farmer, managing to acquire an additional farm as well as improve “Riverside Farm.” The Worthingtons also maintained a townhouse in Frederick until the 1890s, which John inherited from his father, James W. Worthington. John and Mary Worthington remained at “Riverside Farm” until their deaths in 1902 (Mary) and 1905 (John). The farm passed to Glenn and his brother Clark, and although neither lived there, it remained in the Worthington family until 1953.

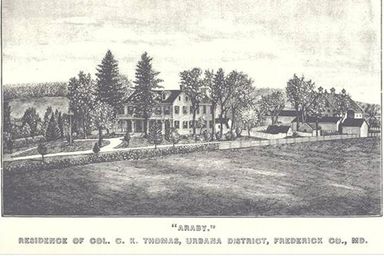

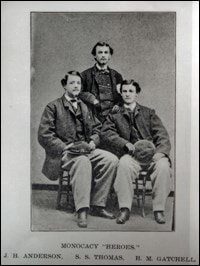

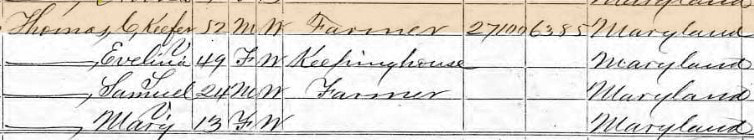

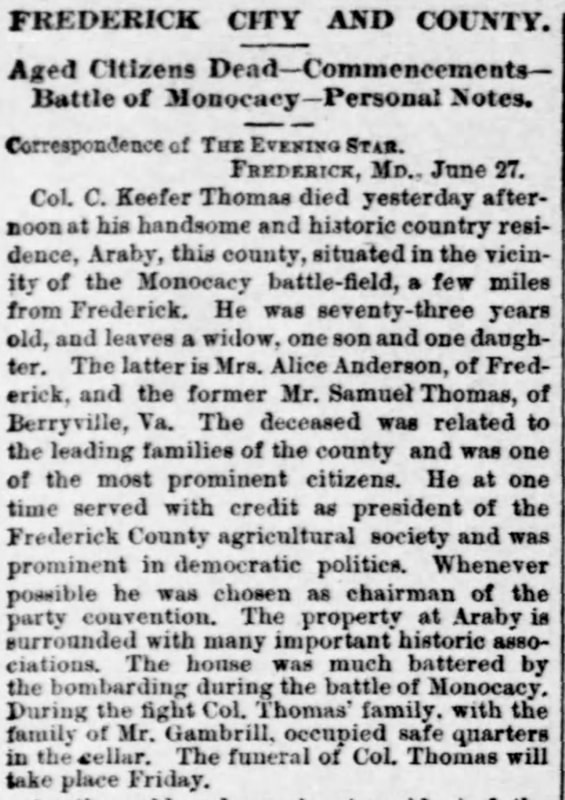

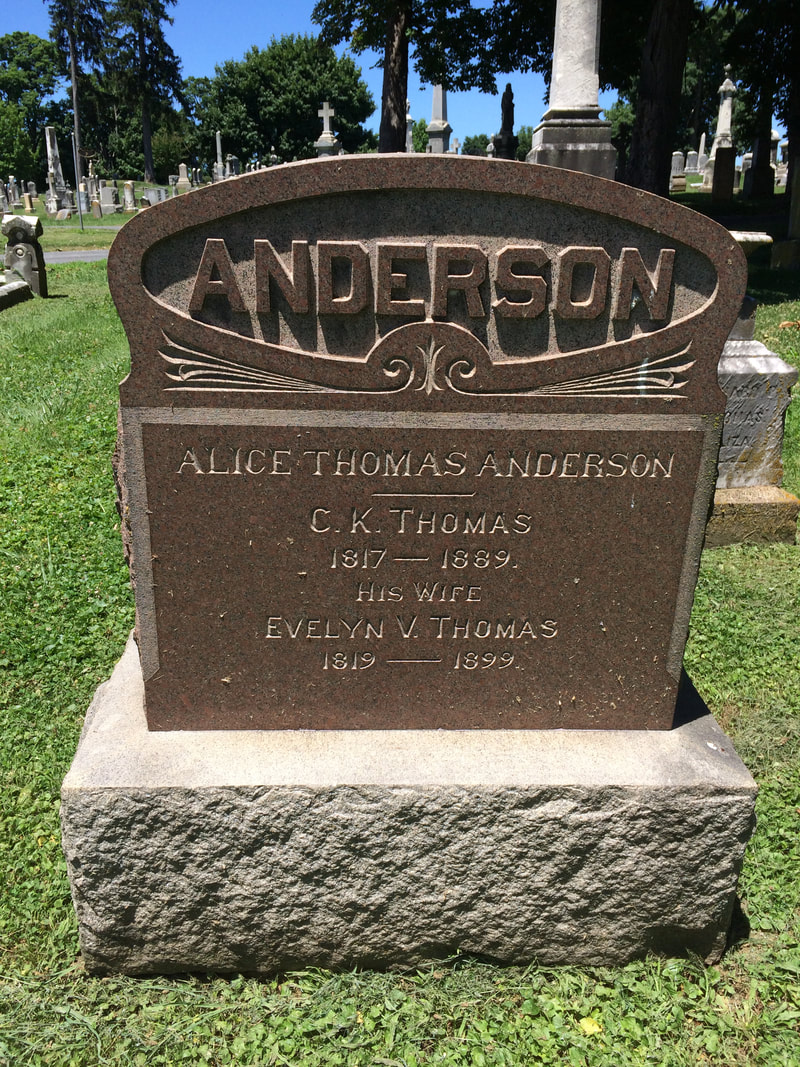

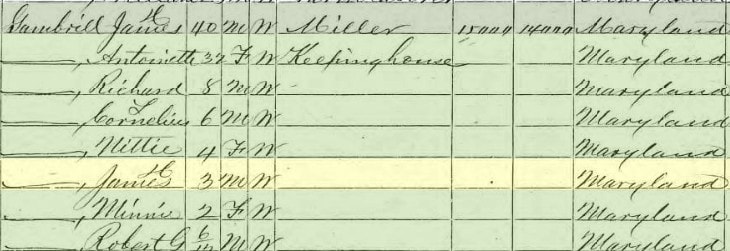

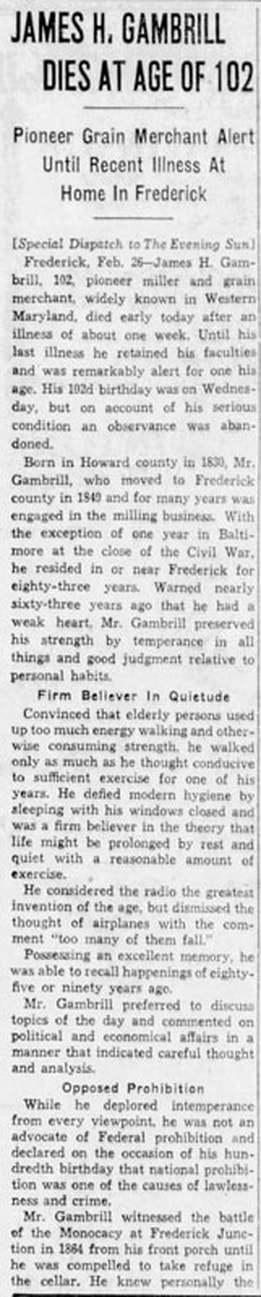

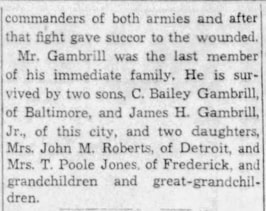

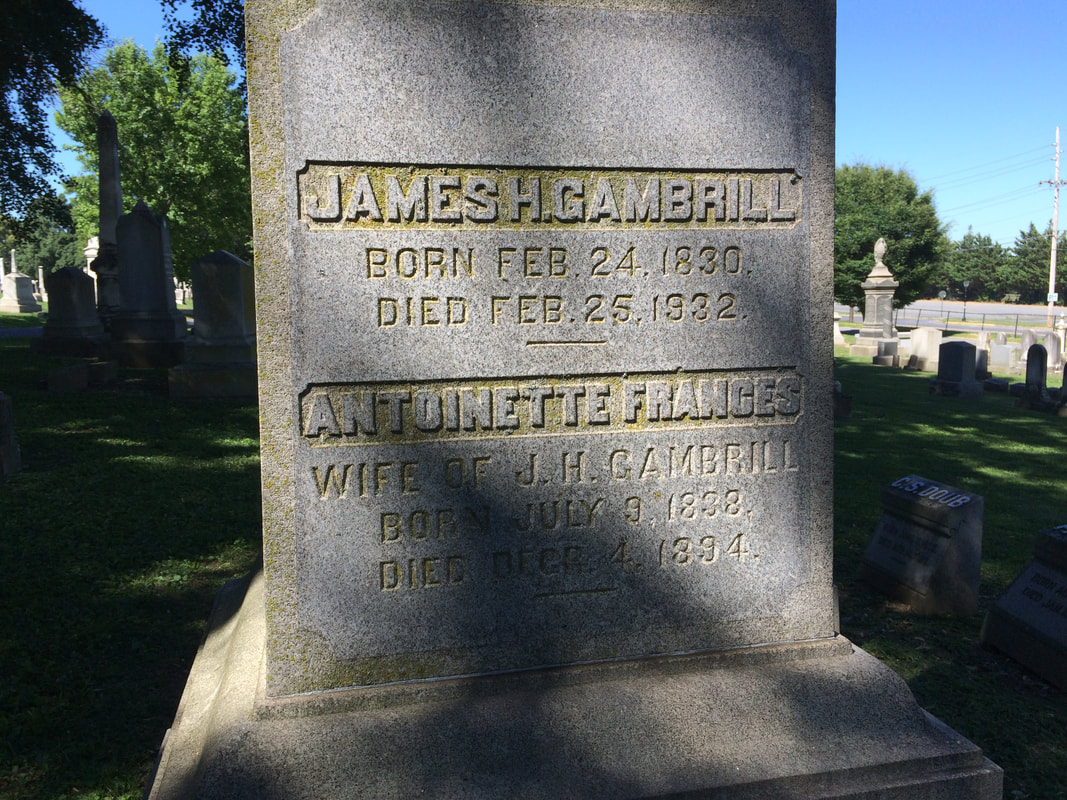

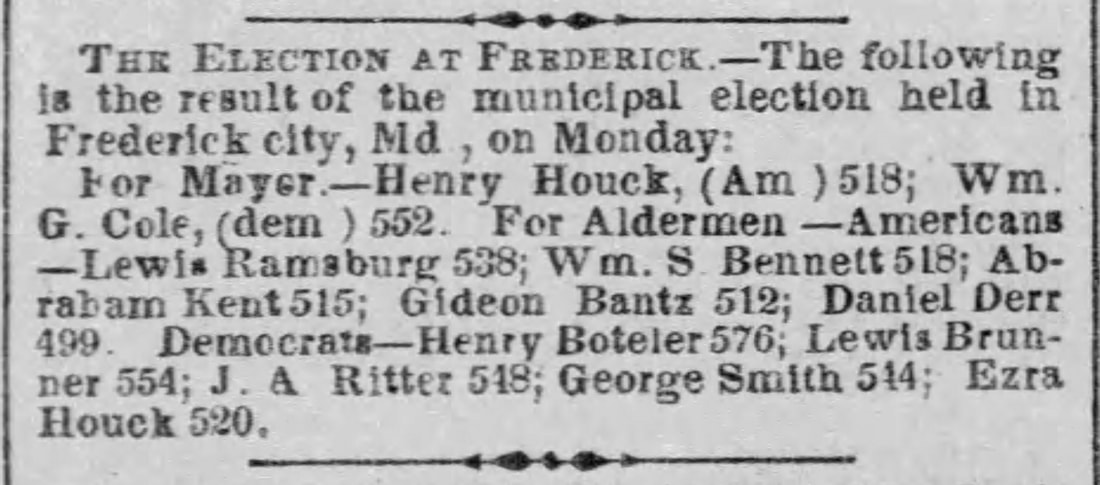

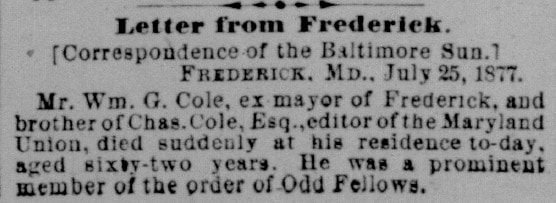

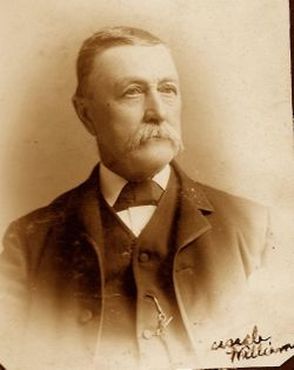

Thomas Family Born in 1818, Christian Keefer Thomas was a Frederick County native. For a large part of his professional life, however, he resided in Baltimore, where he was a partner in the wholesale dry goods firm of Devries, Stevens, and Thomas. In 1839, Thomas married Evelina Virginia Buckey, and within a few years their son Samuel was born. Around 1860, Thomas sold his interest in the dry goods business, and purchased the Araby Farm that same year for $17,823.75. Thomas returned to his native Frederick County to retire, hoping to avoid the impending violence and unrest of the Civil War. The Thomas family had hardly settled in before the Civil War came to them. Because of its strategic bridges, roads, and railways, both Union and Confederate forces were active in the Monocacy area throughout the period of conflict, particularly during the Antietam (1862) and Gettysburg campaigns (1863).  Samuel B. Thomas standing behind his two friends Samuel B. Thomas standing behind his two friends Although he owned slaves and is generally thought to have been sympathetic to the Southern Cause, C. K. Thomas had extensive interactions with the Union army. During the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863, Union Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock headquartered in the Thomas House. Thomas was also friendly with several soldiers from the 14th New Jersey Regiment, who camped nearby at Monocacy Junction during the winter of 1862 and 1863. During the Battle of Monocacy, the Thomas family hid in the cellar while heavy fighting raged around them. Battle accounts record that the fighting "swarmed" around the Thomas House and outbuildings. The house changed hands several times over the course of the day, and Union sharpshooters occupied the upper floors before being flushed out by Confederate artillery. Unfortunately, C. K. Thomas' son Samuel and two friends had come to visit for the weekend. They were captured by the Union Army and impressed into service. These young men were eventually released and managed to escape to neighbor James Gambrill's mill where they hid for the rest of the battle. They were eventually reunited with their families back at the Thomas farm.  Thomas House Thomas House Barely a month after the battle, a Union soldier named John Rodgers Miegs passed by the farm and in a letter to his mother, he gave the following description: “I stand at the house of Mister Thomas the other day where our headquarters were camped on the Monocacy battlefield. I have rarely seen a house more scarred by battle than was his. His daughter, Miss Alice, a lovely and accomplished girl was driven for safety with her mother and the rest of the family to the cellar. She declares that she did not feel very badly frightened though the muskets were popping out of the windows and the balls were rattling against the house until a shell crashed through the wall of the dining room and burst just over their heads with only a thin flooring between. Seven shells struck the house and I counted the marks of twenty-six musket balls on one side of the house and discovered many more afterwards. Her father, she thinks, caused them a great deal of unnecessary anxiety by continually going upstairs to see how the fight came on. Our men and the rebels fought hand to hand around the house and the marks of the bloody contest were everywhere visible.” While the Thomas family survived the battle unharmed, the farm continued to be a focal point of military activity—in August 1864, Union generals Grant, Hunter, Ricketts, Crook, and Sheridan used the Thomas House to plan the Shenandoah Valley campaign. After the Civil War ended, the Thomas family began the process of rebuilding. By 1868, the farm had recovered sufficiently to serve as the setting for 21-year-old Alice Thomas's wedding. In the 1870s, C. K. Thomas became active in local politics, serving as president of both the Frederick Agricultural Society and the local school board. C. K. Thomas died in 1889, after a prolonged respiratory illness. His obituary described him as a "gentleman of pleasant manners" and remarked that "his beautiful home was noted for its hospitality and delightful social entertainments." The family plot is on Area C, (lot 171). One will find daughter Alice and son Samuel buried here with their parents. The farm remained in the Thomas family until 1910. It was acquired by the National Park Service in 2001.  James H Gambrill and family James H Gambrill and family The Gambrills In 1855, James H. Gambrill purchased the Araby Mills complex from his former employer and mentor, a miller named George W. Delaplane. Gambrill was born in Howard County, Maryland in 1830 into an extended family that comprised a virtual "milling dynasty" in the Baltimore area. James Gambrill married Antoinette Staley in 1860 and the couple eventually had ten children, nine of whom survived childhood. By 1872, Gambrill had achieved a level of prosperity that allowed him to construct a lavish Second Empire-style mansion, one of the largest single-family residences ever built in Frederick County, and one its very few full-scale Empire-style houses. Known as Edgewood, it featured an elegant double parlor, intimate library, wine cellar, and spacious dining room, as well as a third-floor ballroom with a built-in stage. The commodious rooms were accented by imported Italian marble fireplaces, elaborate plaster ceiling medallions, elegant wallpaper, and large crystal chandeliers. The house was richly furnished throughout; in 1876, the Gambrill's furniture was valued at $1,200. John Worthington, owner of the nearby Worthington Farm, owned furniture valued at just $350. James Gambrill's success as a miller and businessman continued through the 1870s and 1880s. Described as "a characteristic American merchant, active, thorough, and full of energy and vim," Gambrill took over a large steam-powered flour mill in downtown Frederick in 1878. In 1882, Gambrill installed roller milling machinery in his Frederick City mill, thus becoming an early participant in the "roller revolution" which transformed the American milling industry. Araby Mill was not converted to rollers, but still produced as many as 12,000 barrels of flour per year at its peak. By the close of the nineteenth century, Gambrill's milling business had failed, primarily as a result of competition with the large-scale milling operations of the Upper Midwest. In 1897, Gambrill sold his house and mill, and while the house continued to be occupied by a succession of owners over the years, the mill never resumed operation. In spite of the ultimate failure of Gambrill's milling operation, when he died in 1932 at the age of 102, his obituary described him as a "pioneer miller." James Gambrill and wife Antoinette are buried in the shadow of a stately obelisk monument on Area C/Lot 24. Mayor William G. Cole William George Cole was born near York, Pennsylvania on June 12, 1815. He came to Frederick, Maryland with his brother Charles Edward around 1835. He was mayor of Frederick, Maryland, from 1859 to 1865, two three year terms. He was mayor in 1864 when during the Civil War General Jubal Early assessed a ransom of the City of Frederick of 200 thousand dollars which was not paid off until 1951.

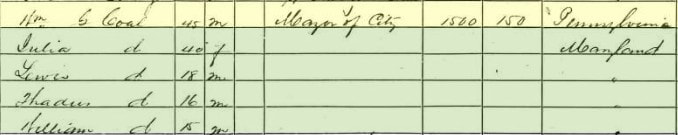

The 1860 Federal Census lists William as Mayor of the City of Frederick. Listed also are wife, Julia, and sons Lewis, Thaddeus and William. After his terms as mayor, Cole would go on to serve as Superintendent of the Frederick Water Works. He died on July 25th, 1877 and was laid to rest in Area P/Lot 39. Mount Olivet is final resting place to countless others who experienced the American Civil War firsthand. We certainly will present more interesting connections through “Stories in Stone” into the future.

6 Comments

shane shanholtz

7/11/2018 09:12:31 pm

another great story thanks

Reply

Michael Kulczak

7/15/2018 06:17:42 pm

Excellent research and linking of the the narrative of the battle and many of the persons involved. The human aspect of the battle and its aftermath were most interesting to me.

Reply

Connie Houtz

10/26/2018 04:21:18 pm

I appreciate the fact that Mt Olivet acknowledges the contributions of Wm G Cole, Mayor of Frederick from 1859-1865. I especially appreciate the picture of his tombstone which shows his death date but not his name. However, much of the information and two of the pictures have been taken from my family tree entry on him from Ancestry.com. I personally own the copies of these pictures which I inherited from a Cole cousin whose husband was Wm Cole’s nephew. As you can see in the picture she has marked it “Uncle Wm”. William George Cole was my 3rd great Uncle. I was born and raised in Frederick and my relatives are all buried at:Mt Olivet where I own the family plot.

Reply

7/17/2024 05:49:31 pm

Hi Connie, I am currently wrapping up writing a story about my recent visit to Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass two weeks ago. of course the burying ground is amazing, and I picked out some famous descendants buried there with ties to Frederick. I also hoped to find a former Frederick resident and did in the person of Nellie Pauline Cole Knisell, your relative!!! I visited her grave and took some photos. I mention her in my story and plan to use the photo of her and her parents that you put on Findagrave and the info too. I will certainly acknowledge you for the fine work you have done in documenting the Coles (with info and photos) on online sites such as Findagrave and Ancestry.com. Give me a call or drop a line as I will be in office tomorrow working on it. My # here is 301-662-1164 if you have anything to add on her! Thanks Connie!

Reply

Jean Graef

2/9/2023 07:40:59 am

My grandmother was Louise Ebert, whose family lived at 147 W Patrick Street. She married my grandfather, George Flavius Linthicum, in 1920 and died 3 years later when my father was a little over 1 year old. George Flavius’s father, George Frederick Linthicum, owned the Seneca Ayr farm — the subject of another PBS documentary.

Reply

Dyre holland

11/21/2023 06:56:26 pm

You saved my history project I love you pookie

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed