|

One of the smallest grave monuments within Mount Olivet is also the most thought provoking. In addition, this final resting place of a child, who died in 1874, is among the most eye-catching, as it clearly stands out against a backdrop of 40,000 other gravesites. The memorial in question is not made of marble or granite, and deceives some into thinking that it could be an above ground crypt—crafted in the shape of a small sarcophagus from ancient time. Before receiving a thorough cleaning a few years back from cemetery superintendent J. Ronald Pearcey, you wouldn’t have even noticed this memorial to Arfue Brooks. And if, indeed, you did find it, an attempt to read the name carved on the exterior would have been a futile and frustrating chore—but not anymore. A bas-relief figure of a sleeping child conjures up a melancholy feeling as the onlooker is tipped off to the occupant’s age and innocence. In contrast, a sudden feeling of warmth (in any season) may follow, thanks in part to the brown-orange hue of the monument— a diversion from the vast sea of whites, grays that can be found throughout the grounds. As far as I know, this is the only terracotta monument of this color and design within the cemetery. Terracotta is a type of ceramic pottery, used to make flower-pots, pipes, bricks, and sculptures. The word (Terracotta) comes from the Italian words for “baked earth.”

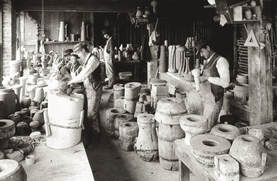

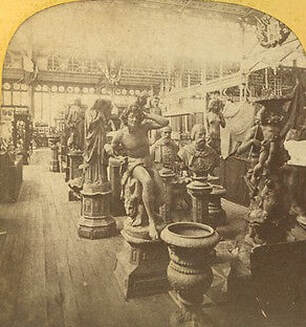

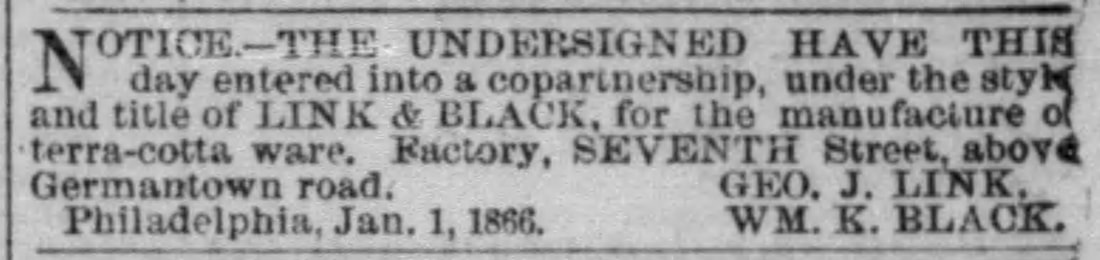

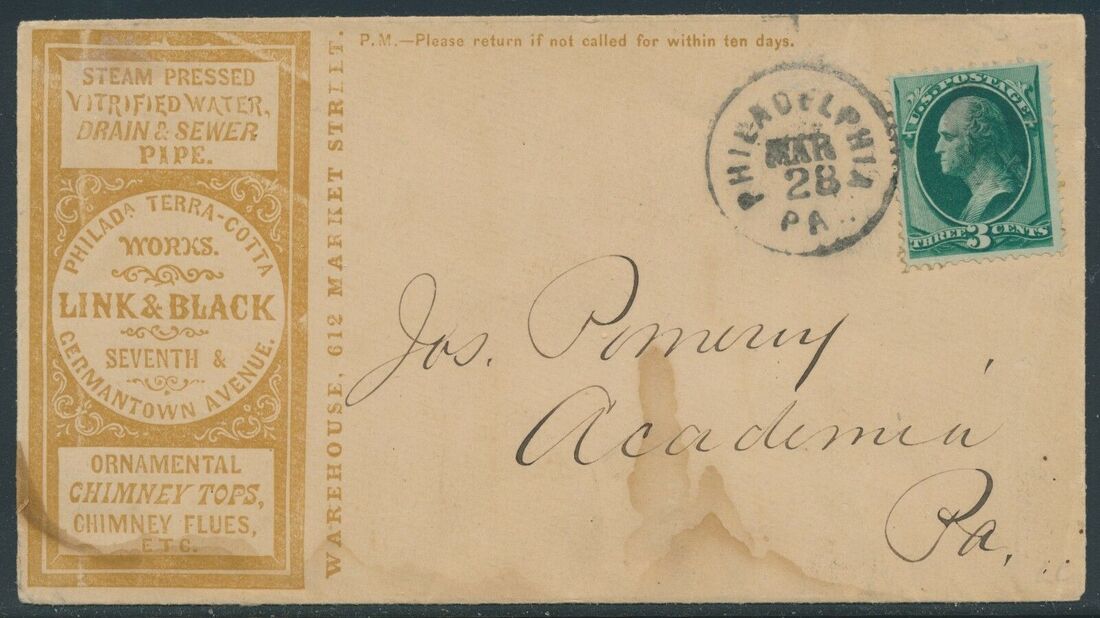

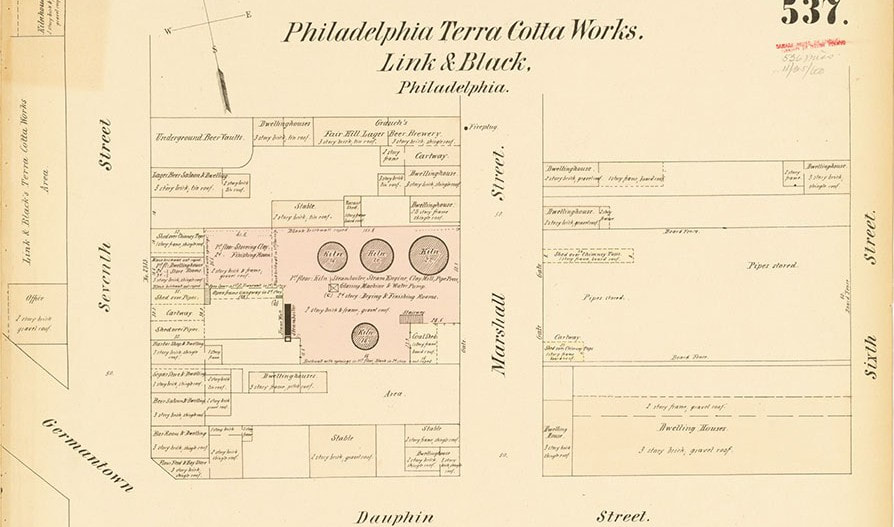

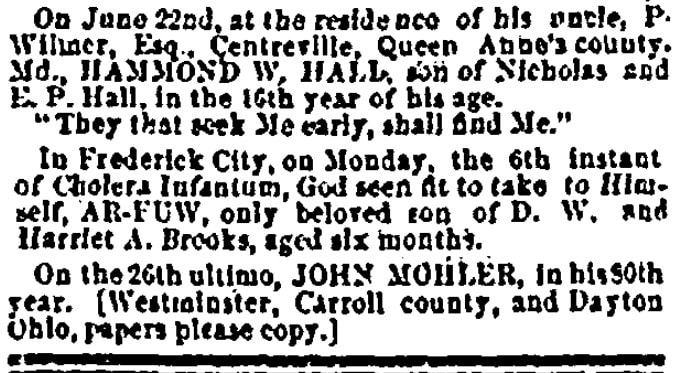

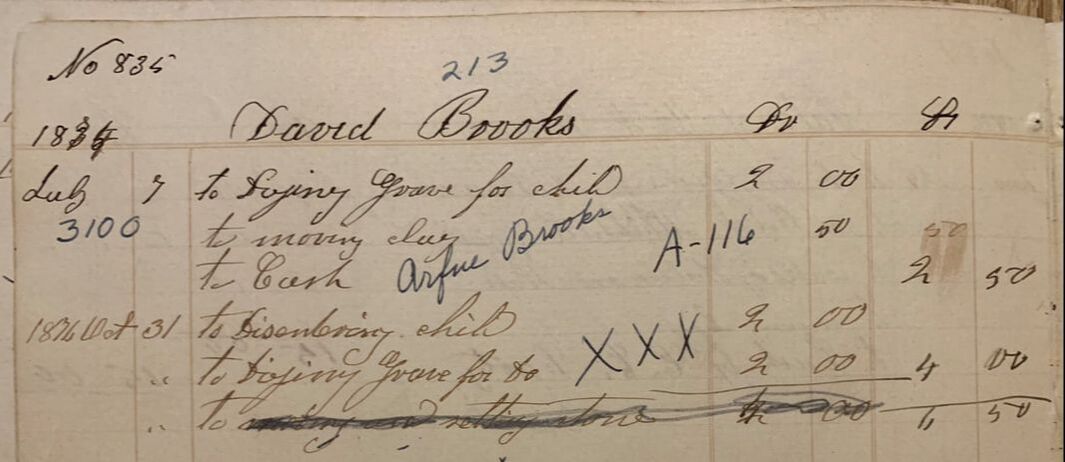

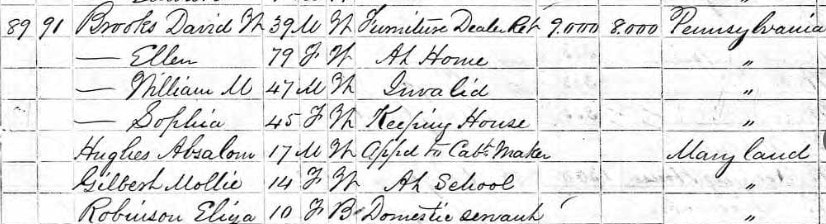

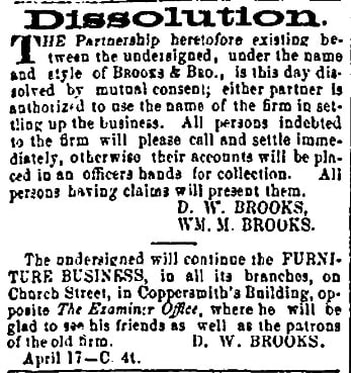

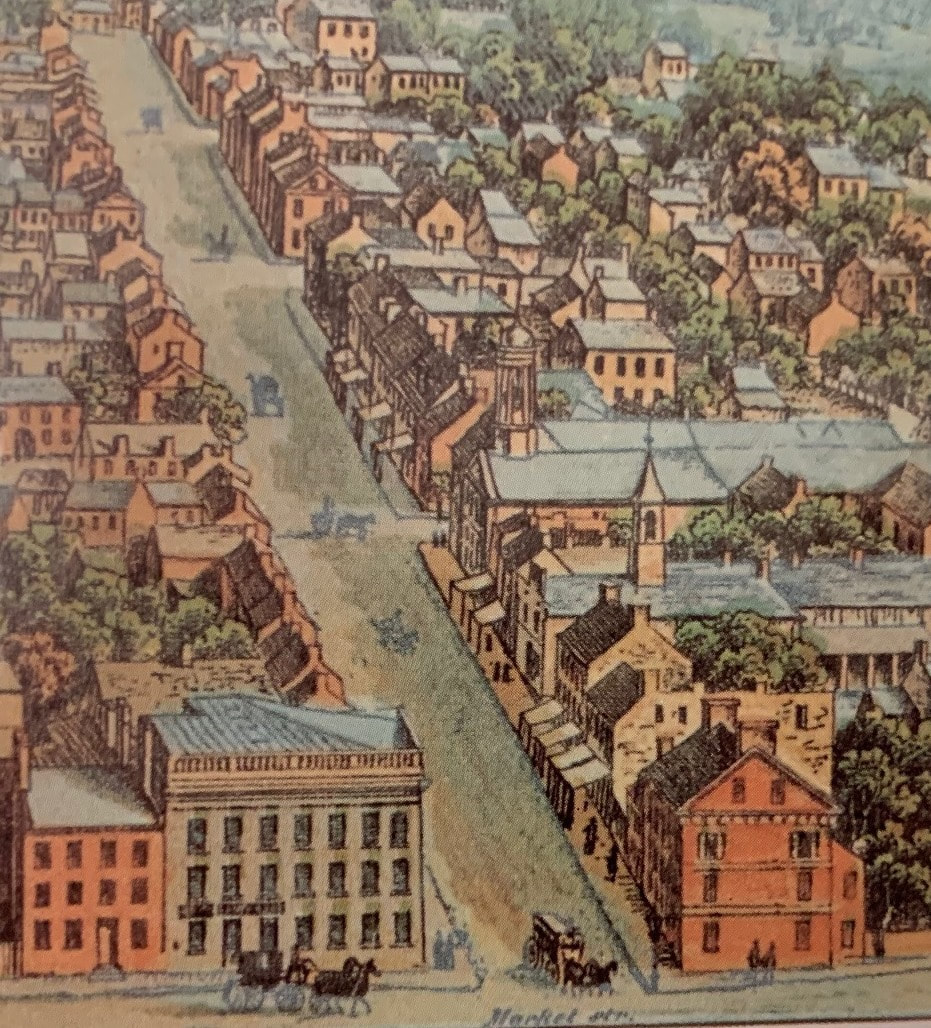

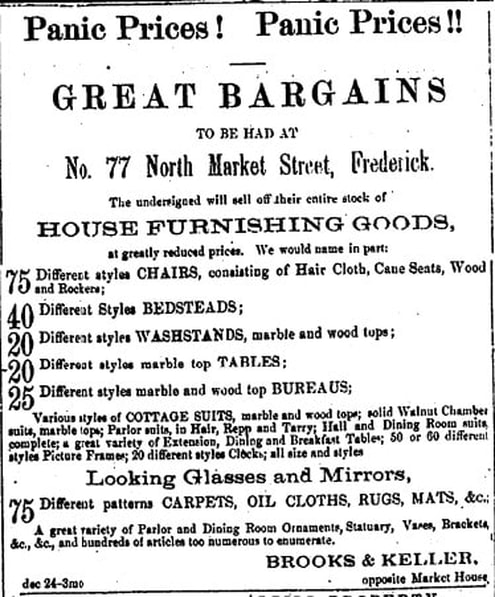

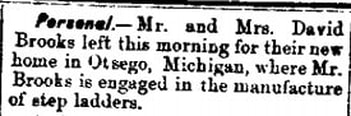

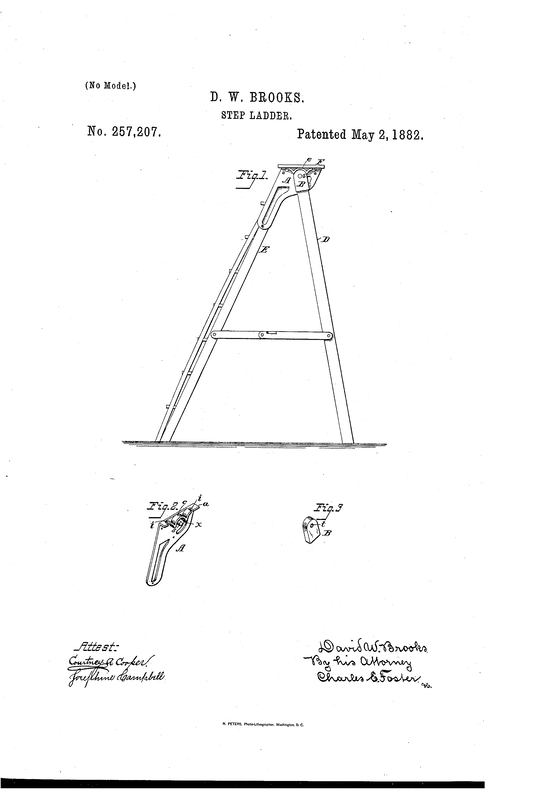

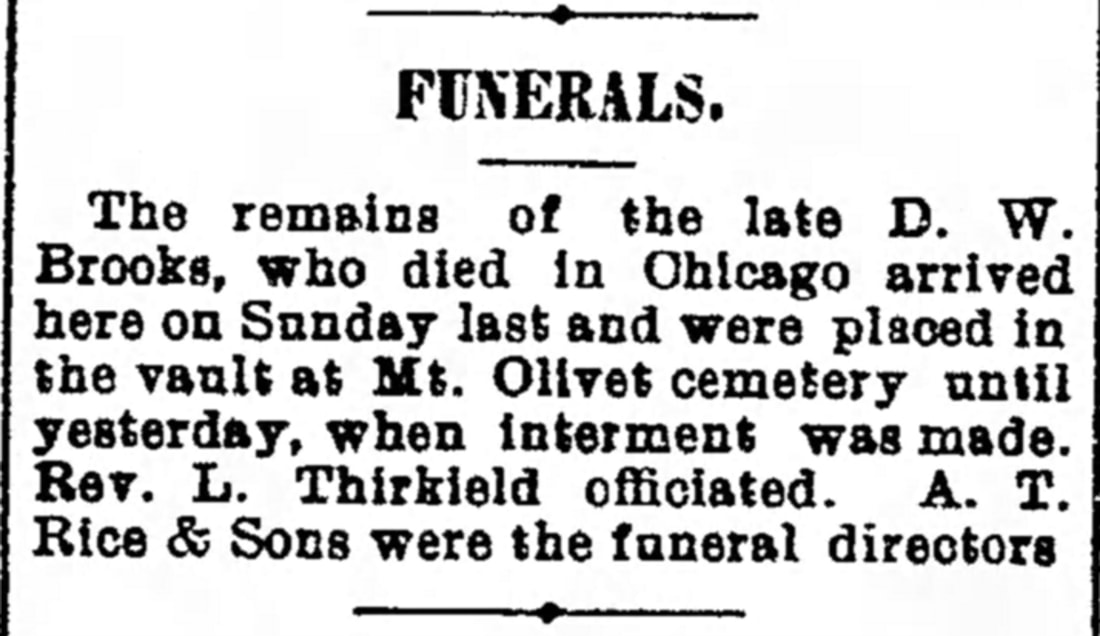

The terracotta comprising grave markers is not simply the brick-red composition of flowerpots and utilitarian redwares. It is called architectural terracotta, a form of ornamental ceramic cladding made from sculpted and molded clay. The body has a fine texture that allows it to be molded, sculpted, and glazed. Terracotta was often made in the form of hollow blocks with internal webbing or supports that allowed it to be both strong and light. Nineteenth-century architects viewed terracotta as a sort of “wonder material.” Less expensive than stone, it could be mass produced to exacting specifications, easily took glaze, was fireproof, could be sculpted and molded, was easy to clean, and billed as lasting forever. I found a study of these memorials online and the researcher had documented 175 terracotta grave-markers in New Jersey and adjacent parts of New York State. Other examples have been reported from upstate New York, near the site of a terracotta factory, as well as from California, Louisiana, and Ireland. The markers were produced in a variety of forms and sizes, most of which fall within the standard canon of Victorian mourning art. They include crosses, tablets, pedestals surmounted by urns, obelisks, and statues. Small marble tablets were often attached with personal information about the deceased. The earliest terracotta grave-markers date from the 1870s and 1880s. They gradually grew in popularity from the 1870s until roughly 1910. Then, they exploded in popularity. After 1920, they rapidly lost their appeal. The latest examples date from the 1930s. Some grave-markers appear to have been sculpted, whereas others were molded. The latter were made in plaster molds, reinforced with strap iron or wires, which could be reused over and over. Pressing the clay into the molds took great strength. After a mold was filled, the pressers would set it aside to dry. The piece was then removed and allowed to sit for several days. Next it was finished by rubbing and trimming. It was then taken to a drying room heated to about eighty-five degrees Fahrenheit. After two days of drying, glazes and slips were applied to the hardened unfired body. Red, buff, and gray was the triumvirate of colors on which the industry initially built its strength. In the 1880s a variety of new colors was introduced. The Brooks terracotta marker here in the cemetery’s Area A/Lot 116 is thought to be one of the earliest of the trade. The decedent, Arfue Brooks, died on July 6th, 1874. A small obituary mention can be found in the Frederick Examiner newspaper dated July 15th (1874) and mentions that Arfue was only six months old and died from cholera infantum (infant cholera). For those, like me, who don’t completely understand this malady, it is defined as an acute noncontagious intestinal disturbance of infants formerly common in congested areas of high humidity and temperature. Although rare today, it was a common form of death back in the day and was nicknamed “the blue death.” I will spare you the explanation, however. A common question we receive from visitors who happen upon Arfue Brooks' grave marker is whether or not Arfue's body was placed within the terracotta crypt which sits about 1 foot off the ground. The answer is a resounding "No," as the decedent was placed in a dug (and back-filled) grave below the monument. Arfue Brooks was the child of a local cabinetmaker from Pennsylvania named David William Brooks (1831-1904). Mr. Brooks operated a successful furniture business with his brother (William M. Brooks) once located at Coppersmith's Hall on the corner northeast corner of Church and Market streets. David and William dissolved the partnership in 1863, but the former would take on a new colleague shortly thereafter and continued operation of his retail store at 77 N. Market intothe 1870’s. Brooks and new partner, John H. Keller, sold a wide variety of household wares and continued to from a new location across from old City Hall on N. Market St. (today’s Brewer’s Alley). David W. Brooks got married in February, 1873. His bride was Miss Harriet Ann Rice, born in 1835, the daughter of George Rice, Jr. and Harriet Trego. Harriet kept the family household located at 417 N. Market St., and soon found herself expecting the couple's first child in January, 1874. Unfortunately, we already know the sad set of circumstances that beset the couple in regard to Arfue's death that following summer. The couple would not have any other children. Mr. Brooks seems to have continued with focus on his business with Mr. Keller, but also appears to have been aspiring to get to new heights—both literally and figuratively. Along these lines, I found an article in a Frederick newspaper from May, 1886 that reported that Mr. and Mrs. Brooks were moving to Otsego, Michigan. Here, David would be engaged in the manufacture of stepladders.

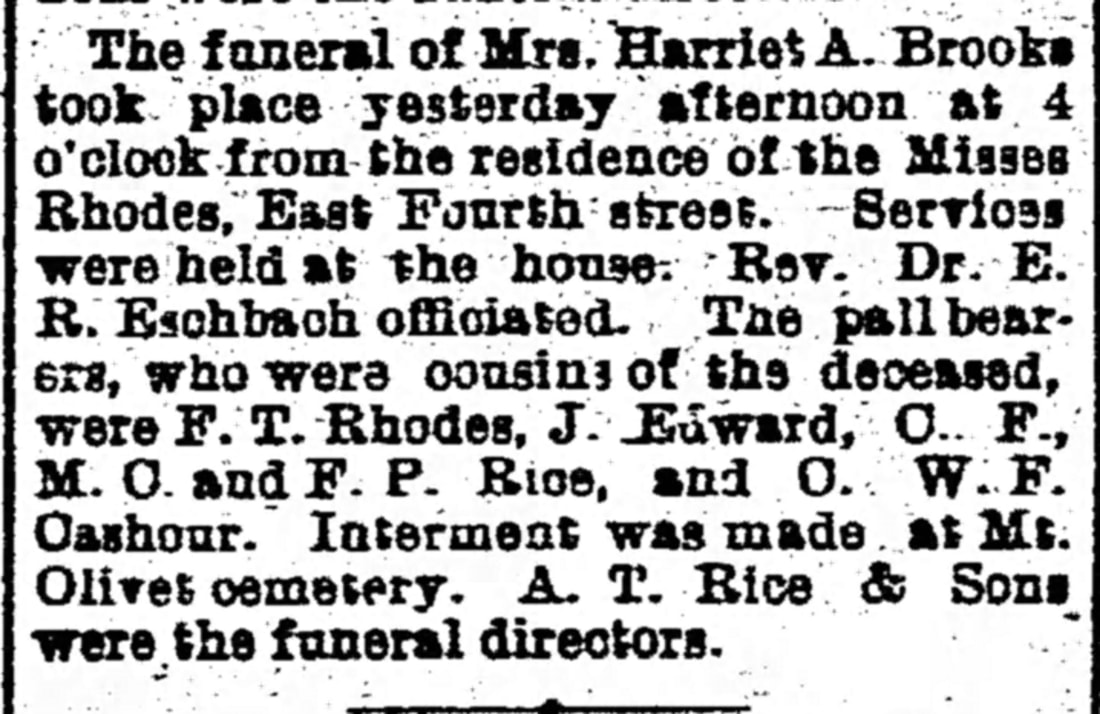

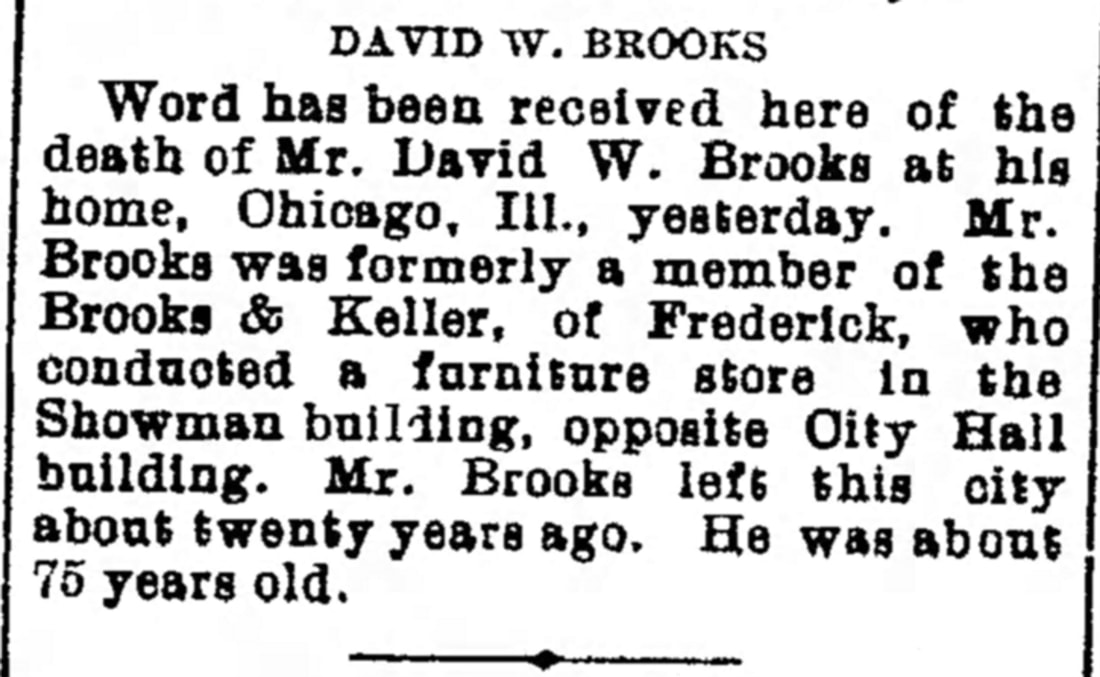

Of the time the couple spent living and working in Michigan, I know not. I hope it was fruitful as we don’t have the 1890 census to give us any clues. A decade later, I found the couple living in the Hyde Park area of Chicago in the 1900 census. Here the couple took up residence in the "Windy City's" south side at an address listed as 82 Avenue L. Daniel’s profession is listed as a cabinetmaker as it appears he had come “full circle” in his professional life. Harriet died in late August of 1902. Her body was returned back home to Frederick, where it was interred a few feet away from son Arfue’s which had been placed here nearly 30 years earlier. As for David W. Brooks, he would live the following two years as a widower at Chicago’s aptly named “Old Peoples Home.” Here he would die on August 15th, 1904. David, too, would return to Frederick and the Brooks family lot in Mount Olivet's Area A/Lot 116 containing the magnificent terracotta grave marker of the son he only had the chance to father for six months.

8 Comments

8/6/2019 05:18:14 pm

This was such a touching article, also very interesting about the terracotta marker

Reply

shane shanholtz

8/8/2021 01:48:12 pm

Great job

Reply

Frederick G. Wood Sr

8/8/2021 02:35:37 pm

Very good article

Reply

Kathryn Zeender

8/9/2021 09:25:46 am

Heartbreaking image....but also interesting article.

Reply

Ann Beall

8/10/2021 12:38:41 pm

Nice story and very interesting. You really did your homework!

Reply

It's interesting to know that terracotta has been used since the 14th century, and it is a clay product or material. I would like to know if there are headstone monuments that would be made from such materials these days. It would be perfect for my grandmother, because she has always been someone who seems traditional which is why it would be perfect for her personality to represent her.

Reply

11/23/2022 03:37:20 am

I find it interesting when you talked about memorial stones that seem sculpted while some are molded. For me, I would like those that are sculpted for the marker for my grandmother's grave. She deserves the best because of how she helped us all to become a better person as we all go through various events in our lives.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed