|

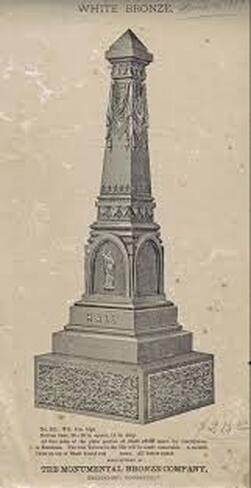

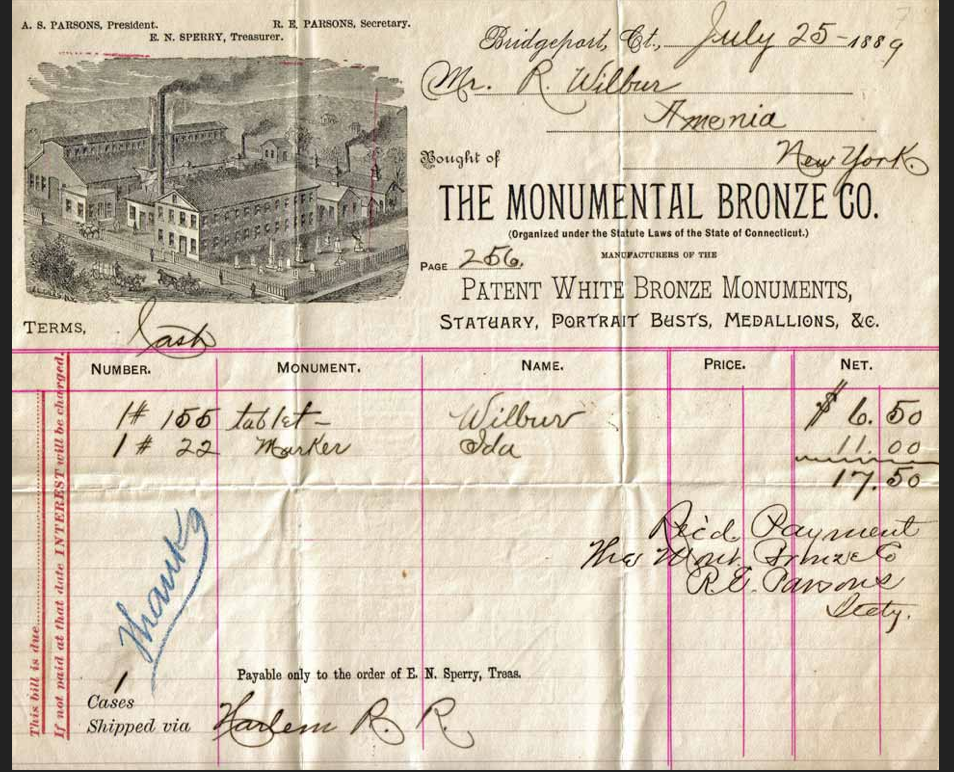

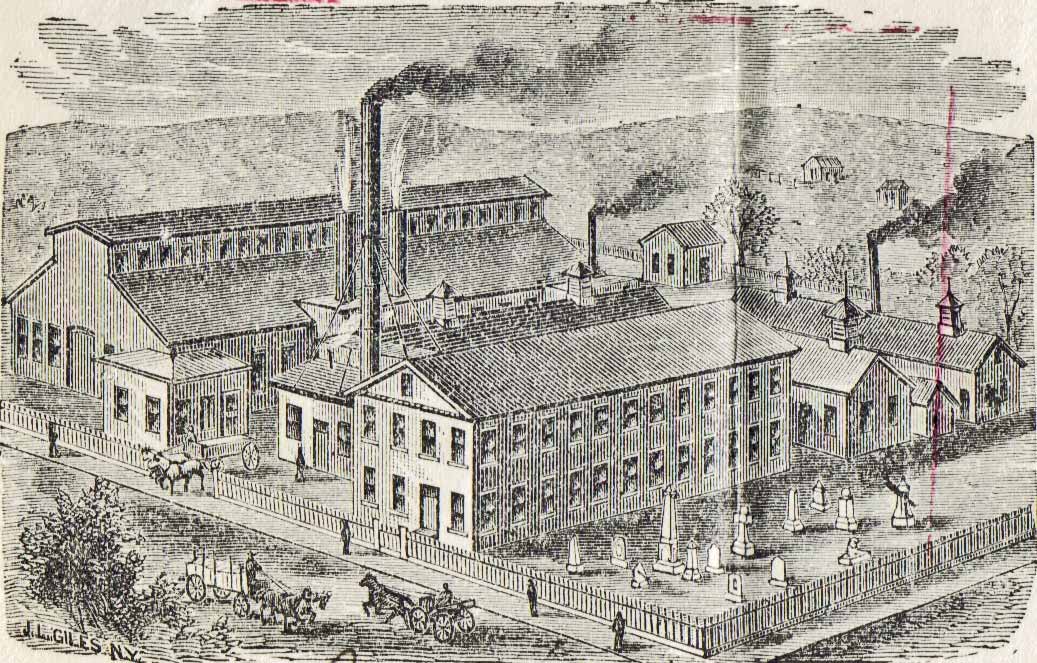

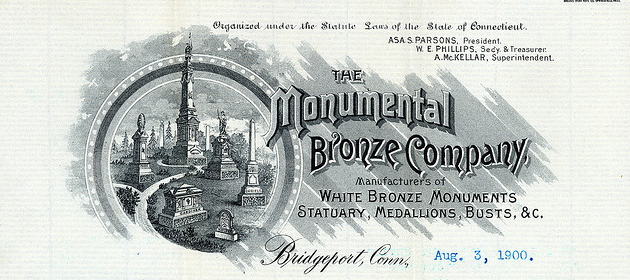

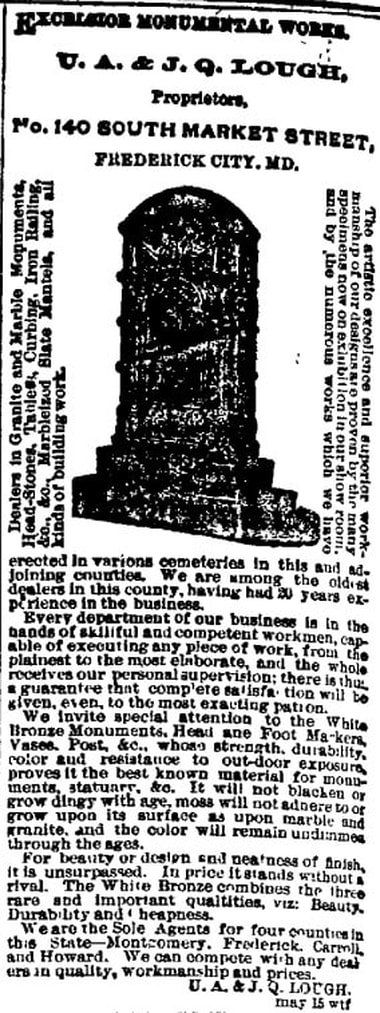

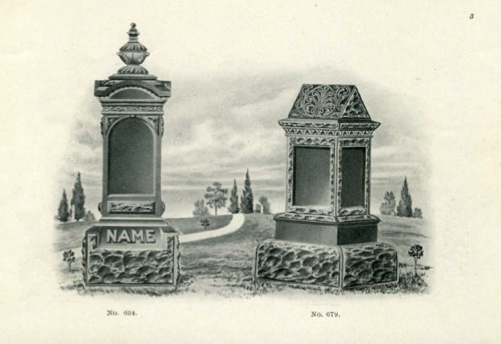

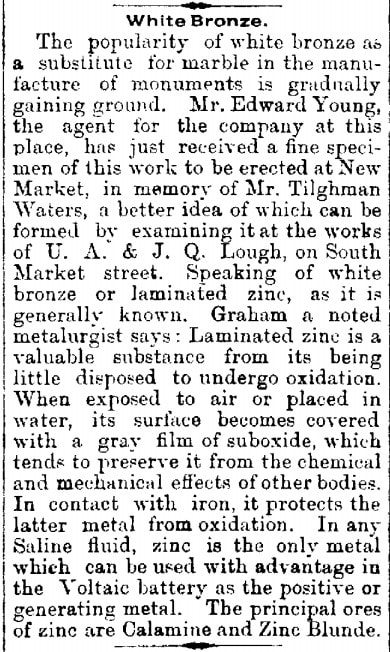

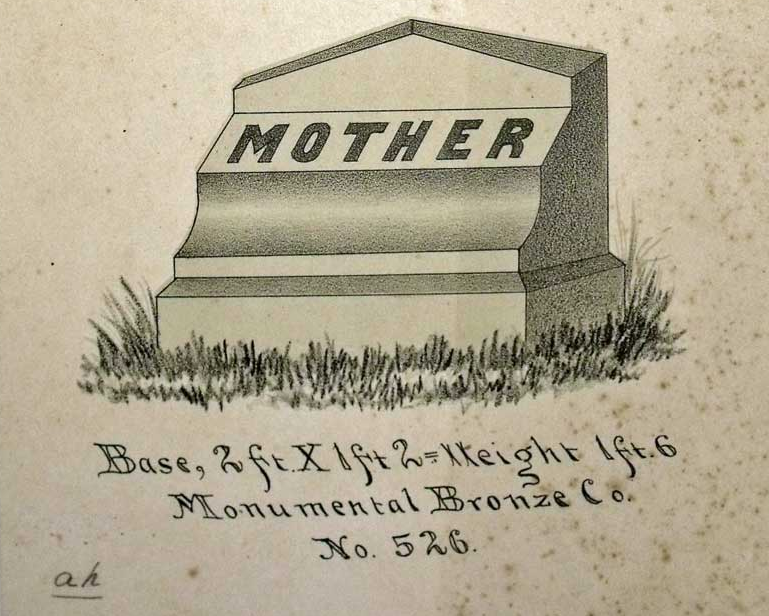

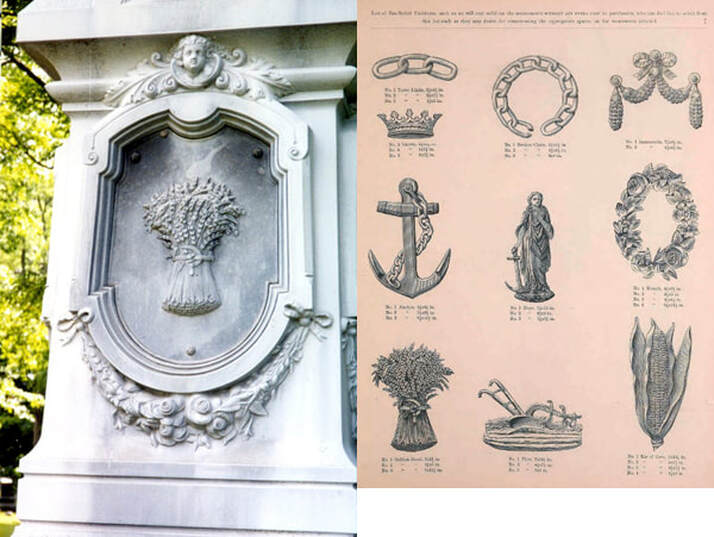

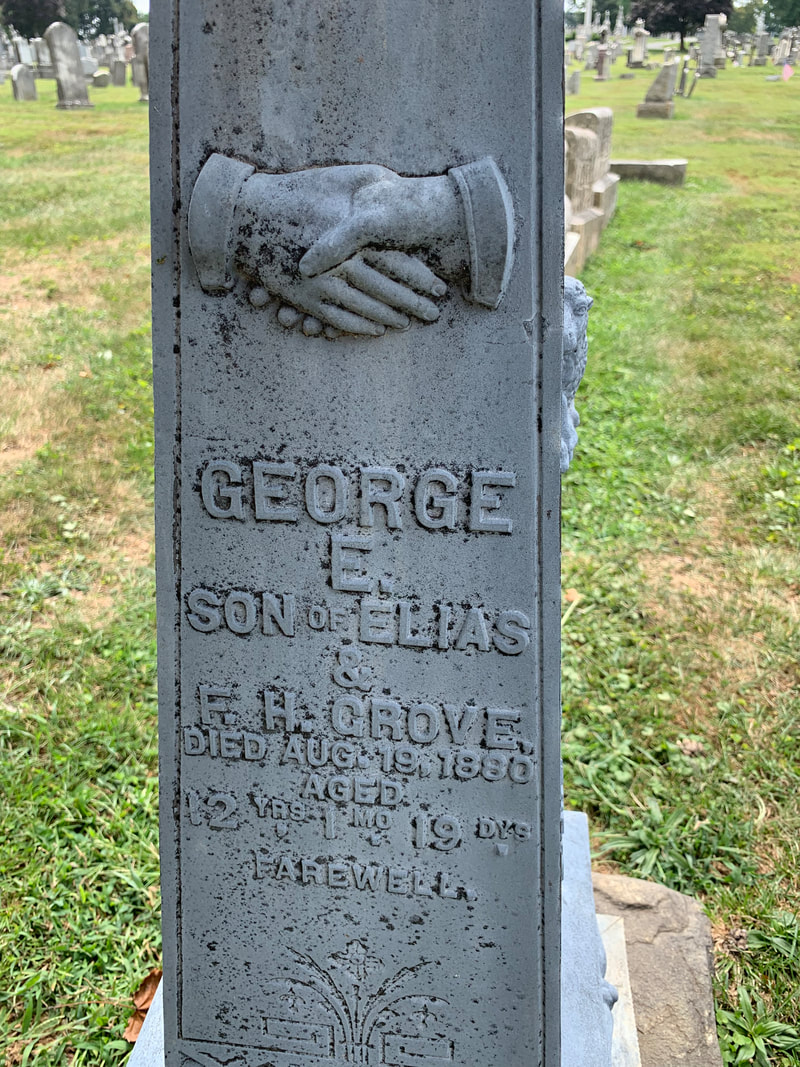

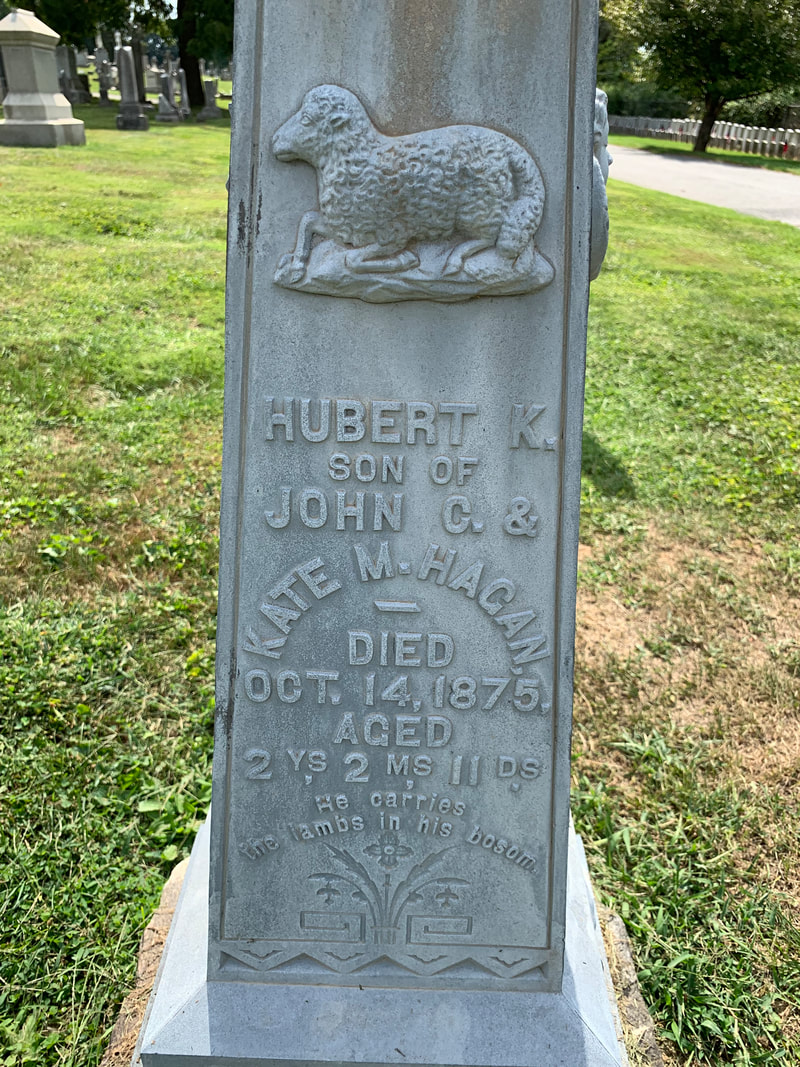

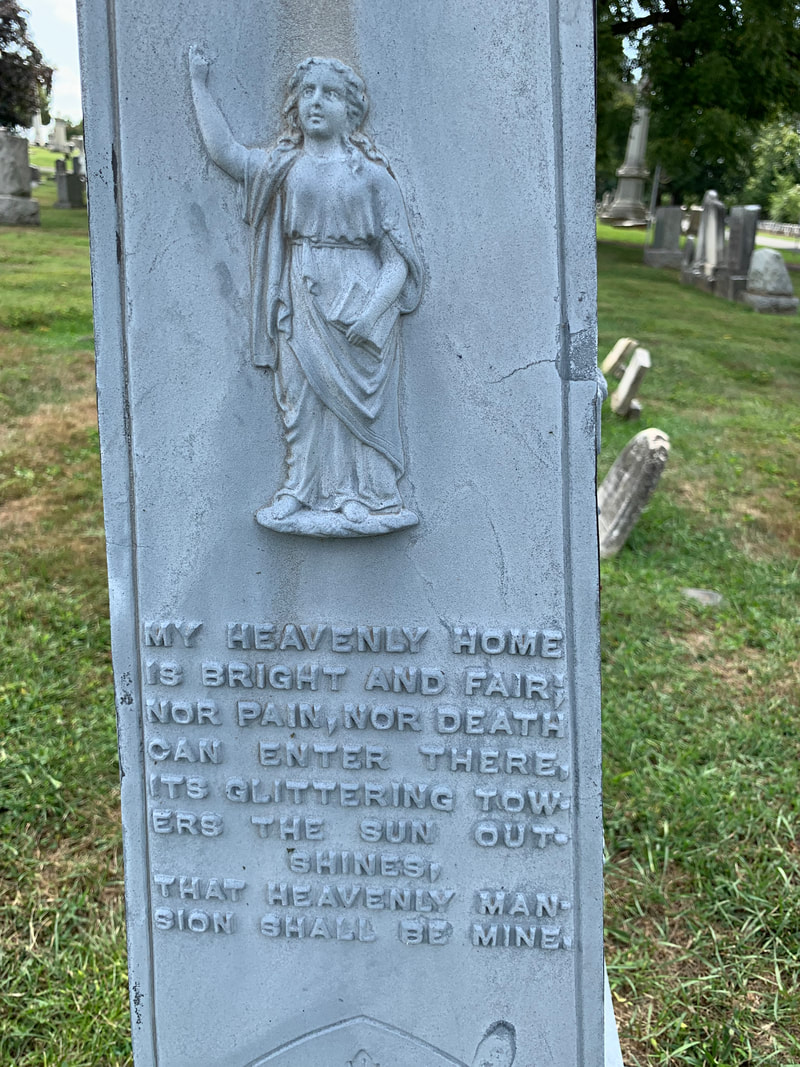

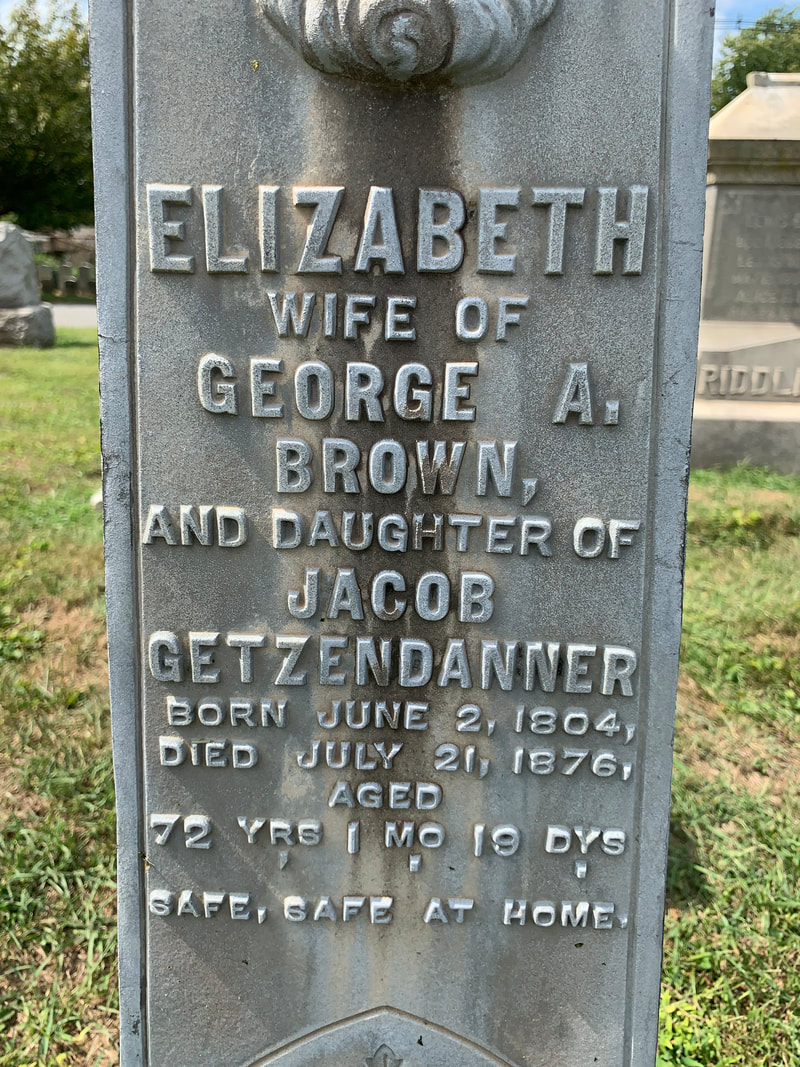

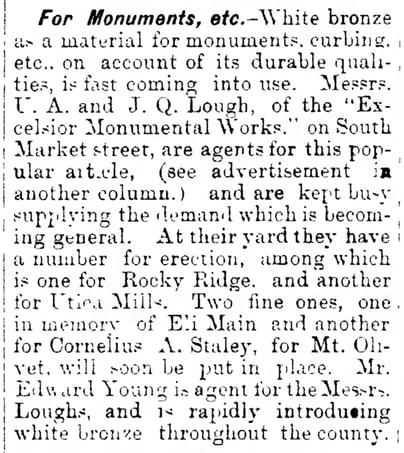

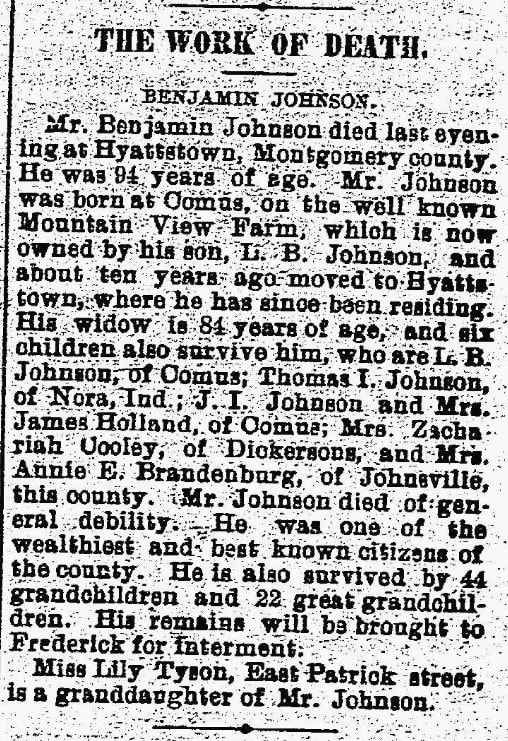

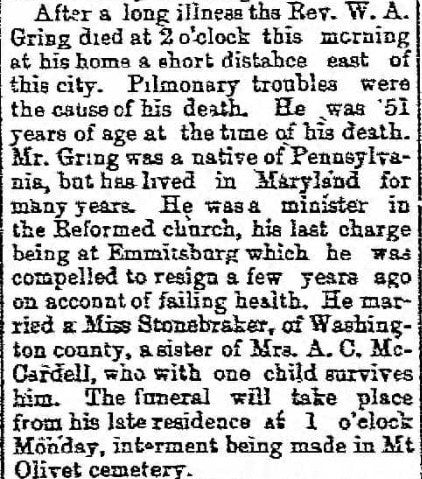

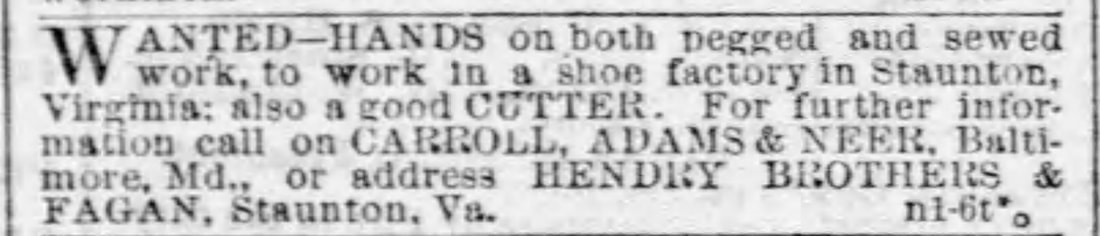

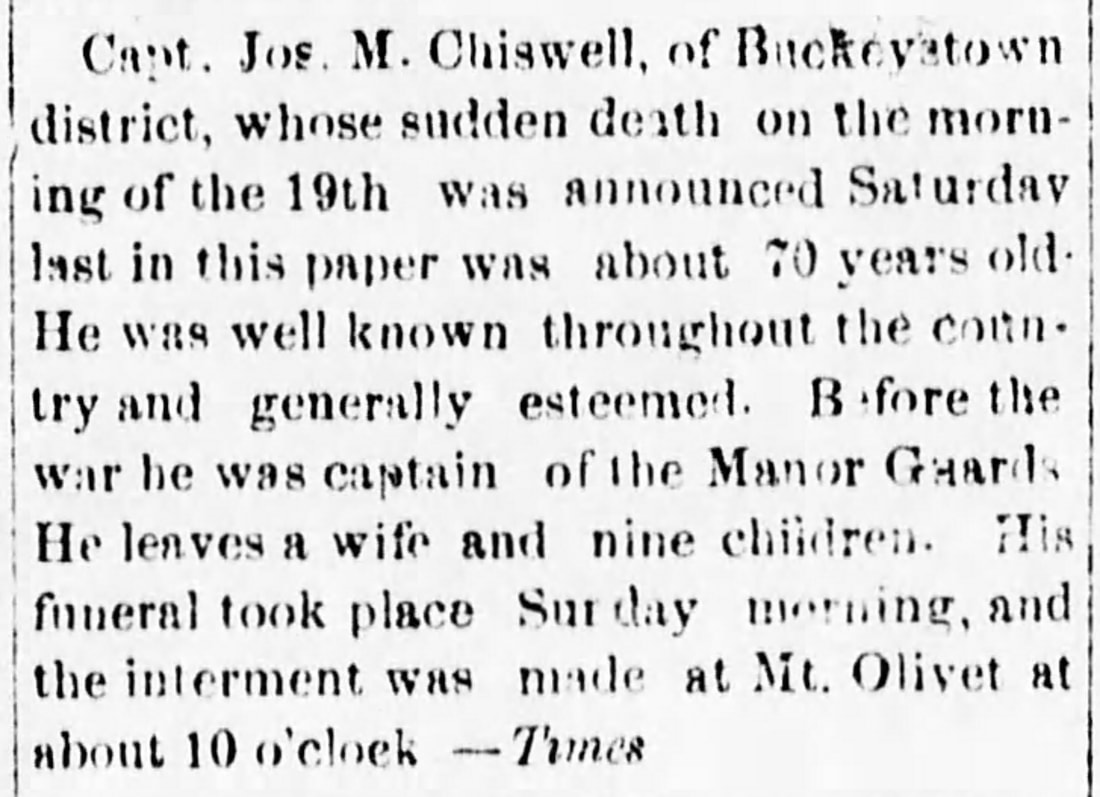

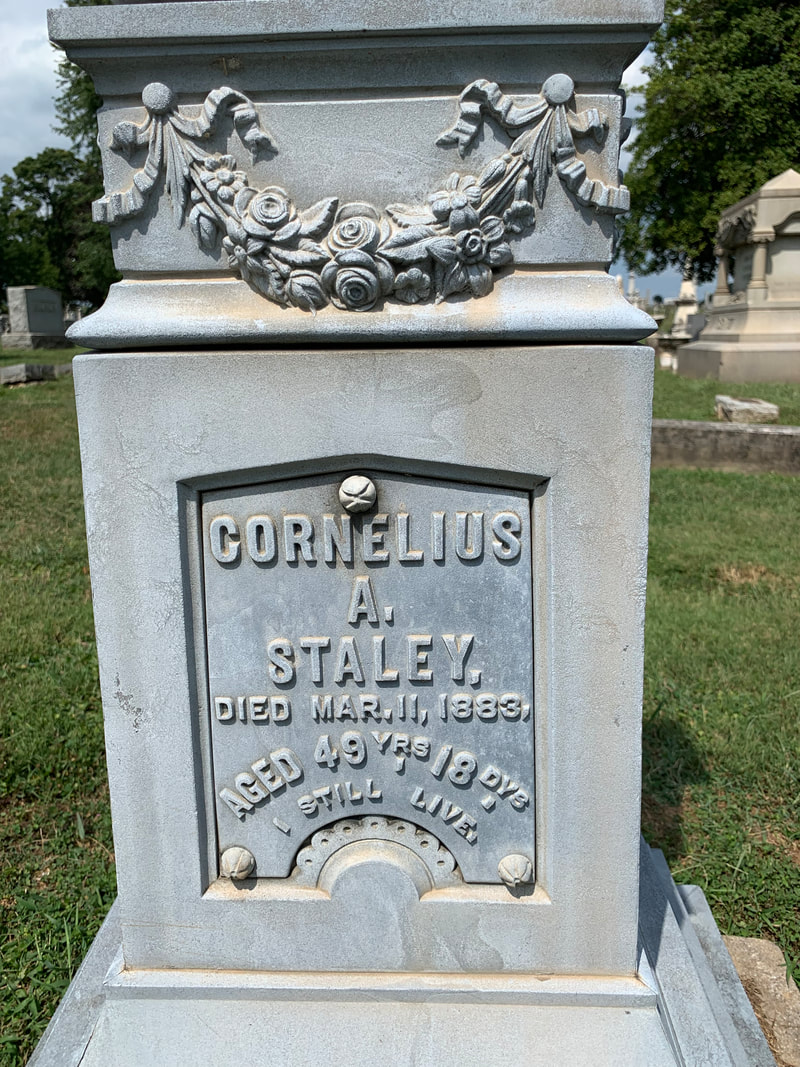

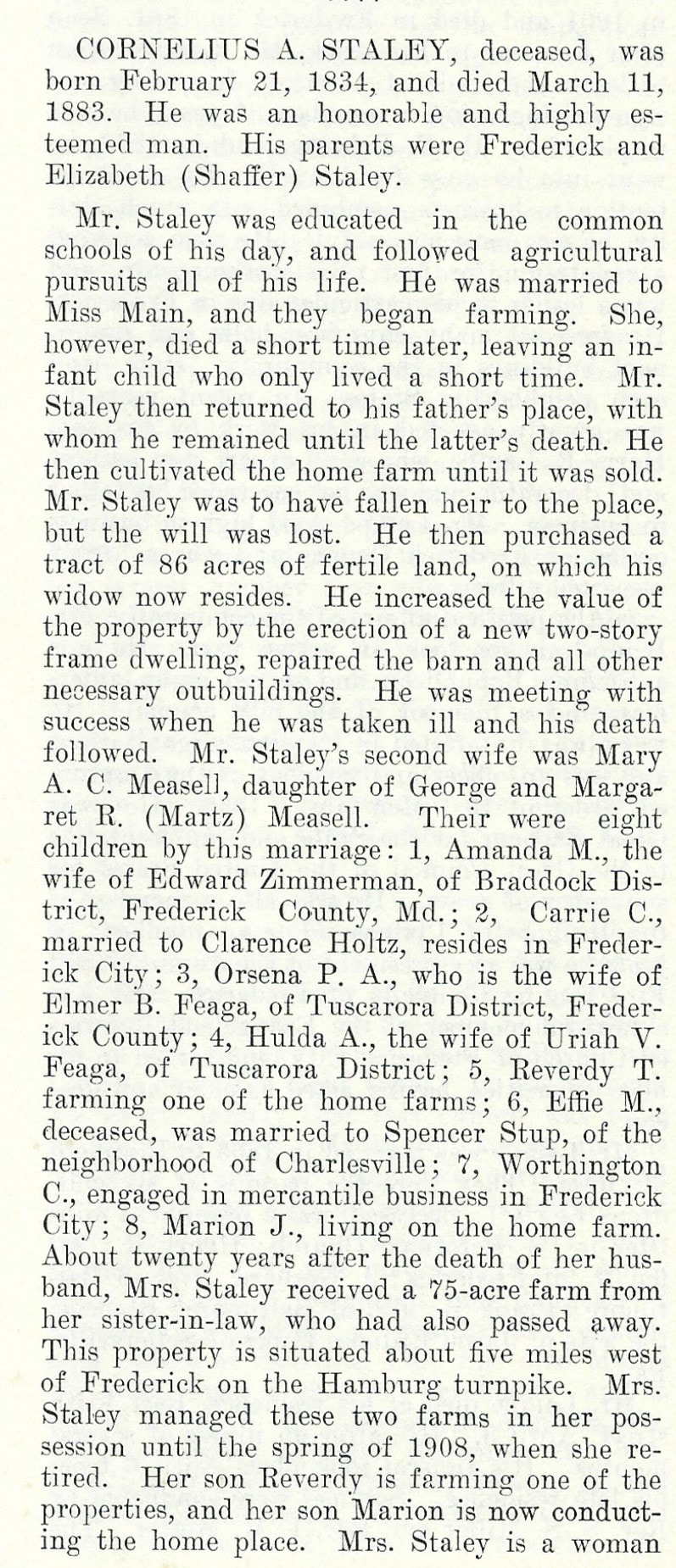

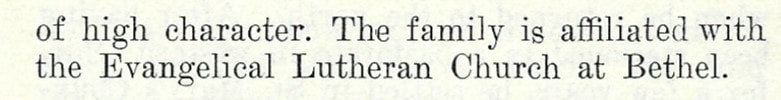

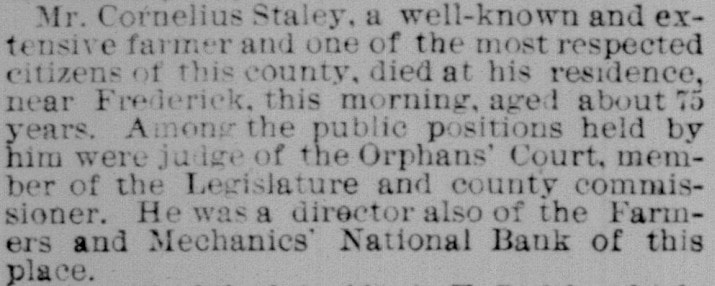

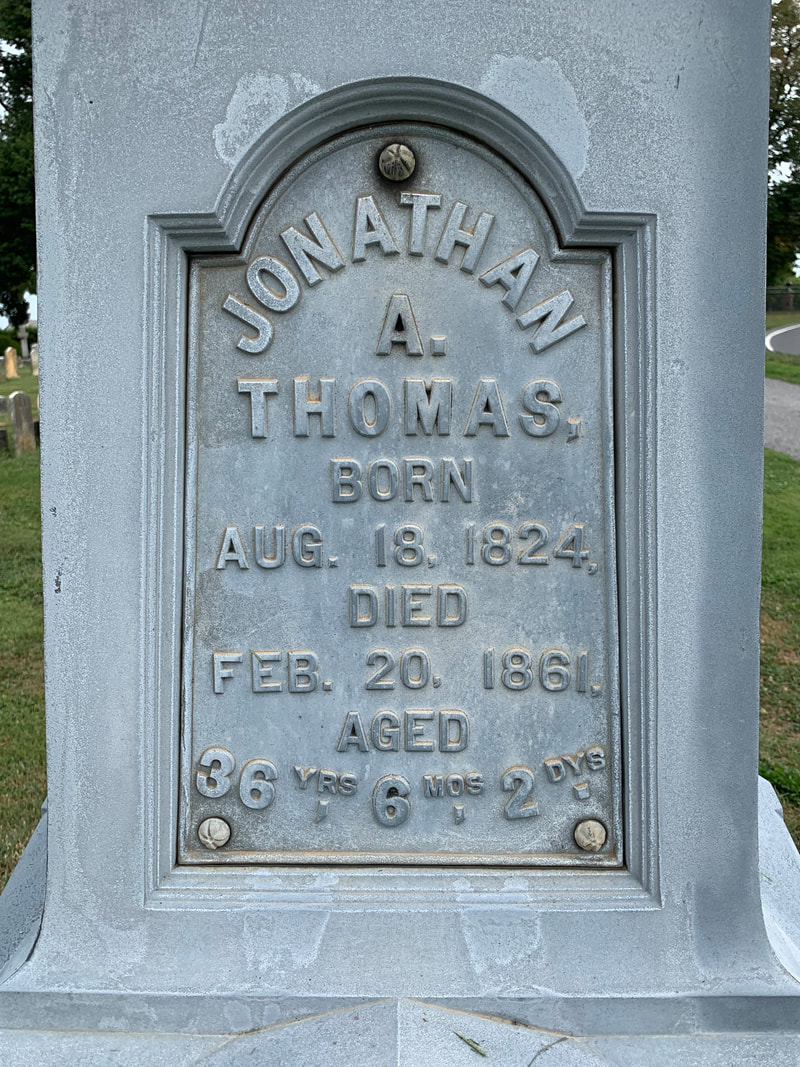

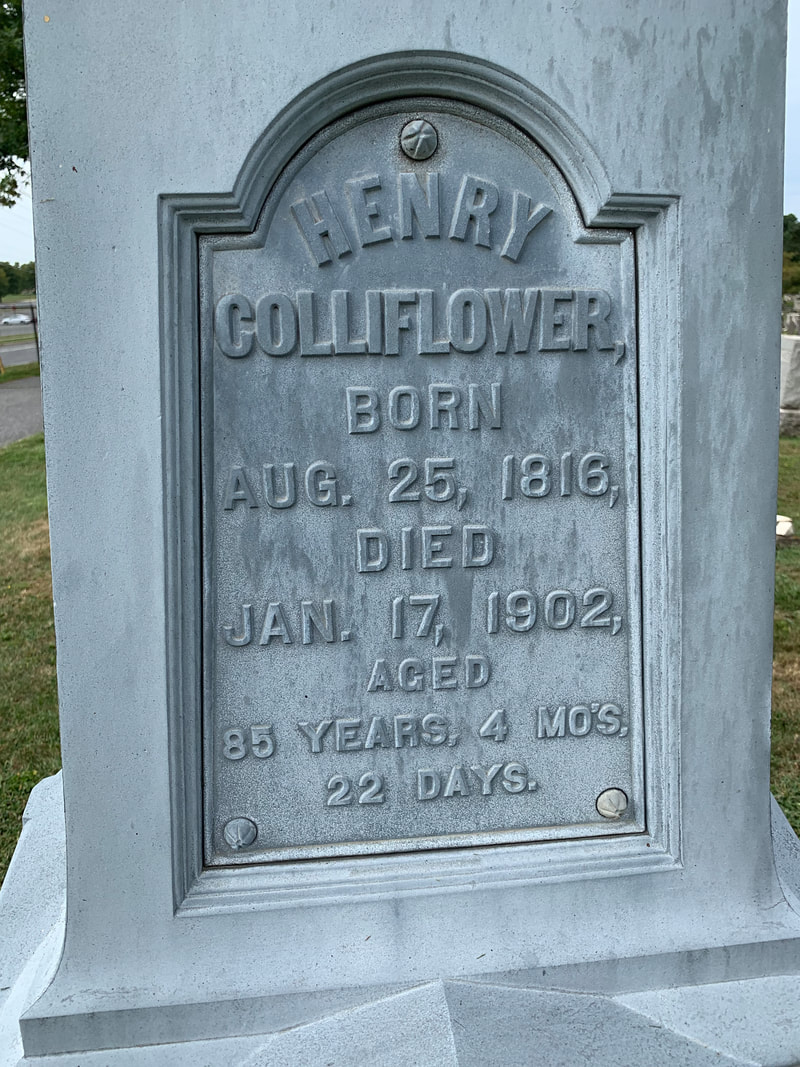

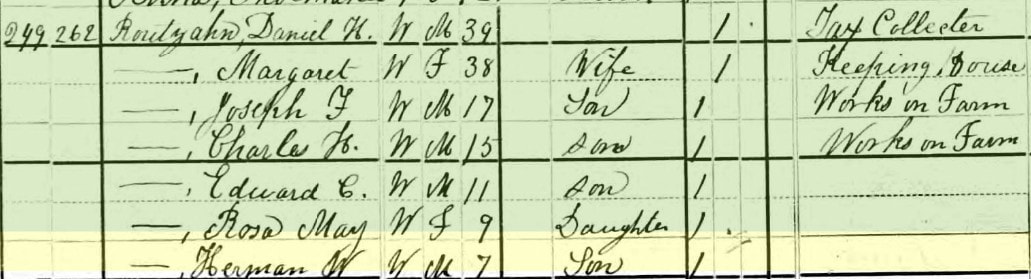

Have you ever wandered through Mount Olivet (or any other historic cemetery) and eyed a bluish-gray colored headstone or monument that appeared to be in stellar condition? Upon closer inspection, you likely noticed that it wasn’t derived from a rock material such as the traditional suspects of marble, granite or sandstone? Hopefully you went one step further and used a few other of your senses—that of touch, and that of hearing. It should feel like metal, and when knocked on with your hand or (gently) tapped with a metal object such as a key or screwdriver, you should hear a hollow “clang.” Chances are you found something very popular and stylish in the last few decades of the 19th century and known as “white bronze” markers. These standout funerary memorials were the brainchild of a man named Milo Amos Richardson (1820-1900) and business partner and brother-in-law, C. J. Willard. Mr. Richardson worked as a cemetery superintendent in Chautauqua County, New York, and had observed the need for a new and better material for cemetery monuments. He set out to develop a solution of creating a material for memorials that would repel moss, algae and lichen, invasive and unwelcome guests that takes up residence on traditional gravestones, especially monuments in shady locations within cemeteries characterized by abundant tree cover or dampness. Richardson and Willard’s formula centered on the use of zinc carbonate and found its home at a foundry in Bridgeport, Connecticut called the Monumental Bronze Company. Richardson, along with two business partners, tried to get a company off the ground but failed. In 1879, the rights were sold and a new company, the Monumental Bronze Company, was incorporated in Bridgeport, Connecticut. One more innovation (that white bronze made possible) resided in the opportunity for customers to employ a myriad of popular symbols and designs of the late Victorian period on these unique monuments. These beautifully ornate memorials became a high-selling novelty especially in the northeast, and the examples that have remained are well over a century old and look virtually new, so to speak! The name “white bronze” was given as it certainly sounded more elegant than zinc. Characteristics of a White Bronze Marker As already mentioned, the headstone will be a lovely bluish-gray, or dare I say “powder-blue” in color. The lettering on the marker will stand out as being made in a cast and put together in panels. The assured way to tell is to literally knock on the marker itself. Tombstone tourists have affectionately refer to these monuments by a nickname coined at the time of their popularity—“zincies.” In some cases, these specimens were often viewed as a status symbol for the deceased solely based on their uniqueness from the norm found in a burying ground. In other cases, they were frowned upon as cheap imitations as white bronze monuments offered a less expensive alternative for a custom designed and detailed gravestone as opposed to a solid granite stone. Some cemeteries even banned them, likely due to the urging of local granite and marble monument companies. Cost ranged anywhere from $10.00 to $5,000.00, depending on design. If attainable, there were often difficulties in finding a salesman in particular states, especially as you headed south and westward. Branches of the Monumental Bronze Company were established in Chicago (American White Bronze Company), Des Moines (Western White Bronze Company), New Orleans (New Orleans White Bronze Works), and St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada (St. Thomas White Bronze Monument Company). Here in Frederick, customers could go to Lough's Excelsior Monumental Works on S. Market St. to order a white bronze marker. The firm began their affiliation with Monumental around 1883-1884. White bronze markers came in all shapes, sizes and styles. They could receive additional customization in many ways including decedent(s) name, dates, epitaphs, and bible passages. Other designs were added as personal expression that can be found on stones today. Some represented religious, fraternal and popular Victorian iconography of the day such as particular flowers, leaves, or other objects often characterizing the personality of the deceased, or the hopes of those left behind. These could be “read” at a glance, part of the popular and material culture of the day. For example, a sheaf of wheat symbolizes a long and fruitful life and symbolizes immortality as part of the harvest cycle. “Rock of Ages” is the title of a hymn popular in the 19th century and still is today. The zinc monuments were made for only forty years, from 1874 to 1914. With the advent of World War I came the demise of the trade. Zinc was needed for the war effort and the Monumental Bronze Company of Connecticut was taken over by the government to manufacture gun mounts and munitions. Although the company continued to exist until 1939, they never produced another monument. Instead, they tried to maintain the industry by crafting panels for existing monuments. Some Romantic stories exist involving the use of white bronze monuments by bootleggers during the Prohibition Era that followed soon after the war. Alcohol was said to be stashed behind panels and inside the hollow portions of the White Bronze monuments, as they seemed to be the last place authorities would search for illegal spirits. In Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, I found 20 individual examples of white bronze funerary monuments. Some of these even carried the stamp of the Monumental Bronze Company near their base. To create a white bronze marker required several steps. An artist would begin the process by carving similar designs used on traditional granite and marble headstones into wax forms. Plaster would be poured into the wax forms and allowed to set, creating a plaster cast. A second, identical plaster cast would then be made. This would be the cast that the sand molds were made from and cast in zinc. The zinc castings were then assembled and fused together with molten zinc. Once assembled and fused, the monuments were sandblasted to create a stone-like finish. And the final step, a secret lacquer would be applied to chemically oxidize the monument, creating the bluish-gray patina – hence the name white bronze. Multiple designs and various sizes are represented in Mount Olivet. It’s hard to determine which one was the first, as some of the decedents memorialized predate the 1874 date given as the start of the “white bronze age.” Some families may have left graves unmarked at the actual death of their loved one until finding this cheaper alternative to a granite or marble marker. This particularly makes sense in connection to the death of a child, especially those of infant and toddler age. Other children and siblings are memorialized here as well. Let's take a look at our 20 markers, shall we? George Elias Grove (1868-1880) Hagan Children  Three children of John C. Hagan and Catherine Brining are listed on a small marker located across from Confederate Row in Area H/Lot 301: Marion Hampden Hagan (1879-1880) and two others that died of Scarlet Fever. These are Emma Claudine Hagan (1868-1875), Hubert Kemper Hagan (1873-1875) who died just 19 days after his older sister. The Olands The Mahoneys  Another brother and sister are located on Area E (Lot 116) Here, Edward Shriver Mahoney (1851-1857) has his own marker, and sister Sarah Kate Mahoney (1848-1872) has a larger memorial to the right of her brother who had died 15 years before her. Both are the children of Eleanor A. (Ervine) Mahoney and William Mahoney. Zimmerman Brothers  I did find it interesting, however, that the majority of the decedents appeared to have died from 1882-1884. Two such were young brothers, the sons of Milton Shuford Zimmerman and wife Alice Diehl Zimmerman. I found the graves of Murray D. Zimmerman (1881-1882) and Norman S. (1882-1884) in Area Q/Lot 98 as perhaps the most unique white bronze examples in our cemetery. Side by side, each is fashioned with a bird in flight. Burial here in Mount Olivet was made in early April, 1891 signifying that they were re-interred from another burial ground. German Roots Some white bronze monuments went to some folks with deep roots to early German families of town. The Staleys The Schmidts Mrs. Elizabeth Brown (1858-1883) Main Family Cousins Noteworthy "Stories in White Bronze" The Johnsons of Comus Benjamin Johnson IV (1813-1902) and wife Martha House Johnson (1819-1906) are located in Area P/Lot 152, not far from ancestor Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr.’s large monument and memorial in Area MM. Benjamin’s great-grandfather was an older brother to Maryland’s first elected governor. The Johnsons lived in Comus, Maryland in Montgomery County, at the foot of Sugarloaf Mountain. Their daughter Louisa Catherine (1866-1883), named for the cousin who married John Quincy Adams, is honored by another white bronze monument. Rev. William A. Gring Another style that differs from the rest is that of Rev. William Augustus Gring (1838-1889). Rev. Gring was the son of Daniel Gring, a German Reformed Church minister in York County, PA. William Augustus was a native of Pennsylvania and at the time of his death had charge of the church in Emmitsburg from 1881-82. Rev. Gring's brother Ambrose was the German reformed Church's first missionary to Japan. The white bronze marker is crafted in the shape of a traditional cross upon a pedestal and contains the name of Rev. Gring’s ten year-old daughter, Vida Rebecca (1875-1885), and his wife, Emma Alice (Stonebraker) Gring (1838-1889). Emma appears to have been the last individual to have a name placed upon a white bronze marker because she died latest (of all decedents) in the year 1930. If you look closely, you can see that Emma’s panel seems out of place as it had to be specially crafted as the fad was long since over, the Monumental Bronze Company having closed years earlier. Hendry the Shoe Salesman Nathaniel Burwell Hendry (1831-1883) was a native of Urbana who worked as a successful shoe merchant who ran his business in places such as Staunton, VA and Baltimore in addition to Frederick. Hendry's widow, Candace E. C. Windsor ran a popular boarding house in Ijamsville after his death. It was called the Windsor Inn. She is buried beside him but has a traditional granite stone marker. Captain Joseph N. Chiswell Capt. Joseph Newton Chiswell (1812-1883) was a native of Poolesville, but spent most of his life as a farmer in Buckeystown for many years. At the time of his death, he was serving as the Treasurer of the Maryland State Grange. I found a reference online that he was a great nephew of Sir Isaac Newton which is sort of gravity defying. He is buried in his plot in Area H/Lot495 with wife Eleanor (White) Chiswell (1822-1864) and a second wife named Virginia Catherine White (1830-1903). Eleanor and Virginia were sisters. Captain Cornelius Staley Capt. Cornelius Augustus Staley (1834-1883) was an American Civil War veteran for the Union. He is joined by wife, Mary Ann Catherine E. (Measall) Staley (1838-1913). The Staleys lived north of Frederick City at a place called Charlesville. Colliflower and two other Sides The largest, and presumed, most expensive white bronze marker in Mount Olivet can be found near the front entrance in Area A/Lot 86. This is a stone likely erected shortly after the death of Elizabeth Ann (Long) Colliflower who died in late December, 1882 at the age of 57. Mrs. Colliflower was married twice and the names of both appear on opposite sides of her monument. Jonathan A. Thomas (1824-1861) was her first, and Henry Colliflower her second. Incidentally, Henry (1816-1902) outlived his late wife by just over 19 years. The Monumental Bronze Company always claimed that the white bronze monuments were superior to granite and marble gravestones. And after 100 years, this claim has proven true. The outstanding quality and durability of the white bronze monument has indeed survived, and become even more popular, right into another century. Routzahn Children The lamb is a widely used symbol in cemeteries used to signify innocence. It is frequently used to denote the grave of a child. This white bronze monument marks the final resting place of two young children belonging to Daniel Henry and Margaret Catherine (Fulton) Routzahn. The childrens names are Richard Henry (who died as an infant in 1877), and Herman W. (who died at the age of 8).

Mr. Routzahn owned a farm in Mount Pleasant and served as the Collector of State and County Taxes at the time of his sons' deaths. He would pass in 1898, but his grave would be marked with an upright granite marker which sits adjacent the white bronze lamb marker for the boys.

6 Comments

Sherry

9/10/2019 12:17:29 am

I noticed these when I was a teenager. I asked my uncle (Wilson Waltz, owner of U.A Lough) about them. He explained them, & took me on a tour of Mt Olivet to see all his favorites

Reply

10/22/2019 10:50:38 am

I didn't realize that grave markers could be made of metal, which was popular in the latter end of the 19th century. Thank you for expanding my understanding of what is possible with memorials. My husband and I are trying to pre-plan our funerals, and I've been trying to decide between colored granite or a different material. I'll be sure to keep the option of metal in mind.

Reply

Glenda Rickard

1/30/2020 11:35:19 am

I read the quotes from these beautiful old headstones and I thought they were beautiful words..I absolutely love history and you not only showed us what they looked like way back then but you included the history of these people that I was amazed to read..thank you for letting us know something of them and the way they met their days of dismiss..

Reply

I love that you talked about having a bluish-gray or powdery blue headstone that will look perfect with a white bronze marker. I will suggest this to my mom regarding the custom engraved headstone services that she plans to get for my grandmother. She passed away earlier because of her old age which is why we are looking for our options now that we need to prepare for her funeral. And we definitely want the best for my grandmother, especially using the things that she likes such as the color and design.

Reply

3/5/2023 10:53:25 pm

The art and craft of creating headstones is a fascinating and deeply personal process. Using materials such as Pal Tiya Premium can offer a unique and long-lasting tribute to a loved one. It's important to work with experienced professionals who can guide you through the process and ensure a high-quality result.

Reply

4/10/2023 07:15:01 pm

I appreciate that you explained that every monument would provide durability because of its materials. My aunt told me the other day that she wanted to have a custom engraved headstone with the finest quality natural granite for my uncle. She asked me if I had any idea what would be the best monument approach. Thanks to this helpful monument article, I’ll tell him we can consult a trusted grave monument service as they can help with our ideal design.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed