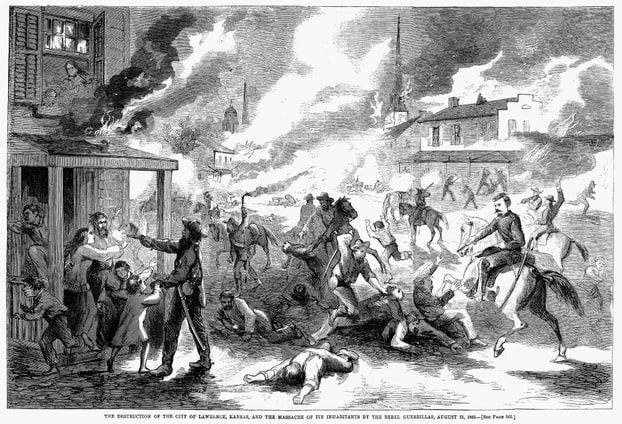

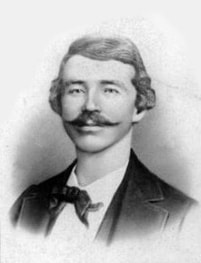

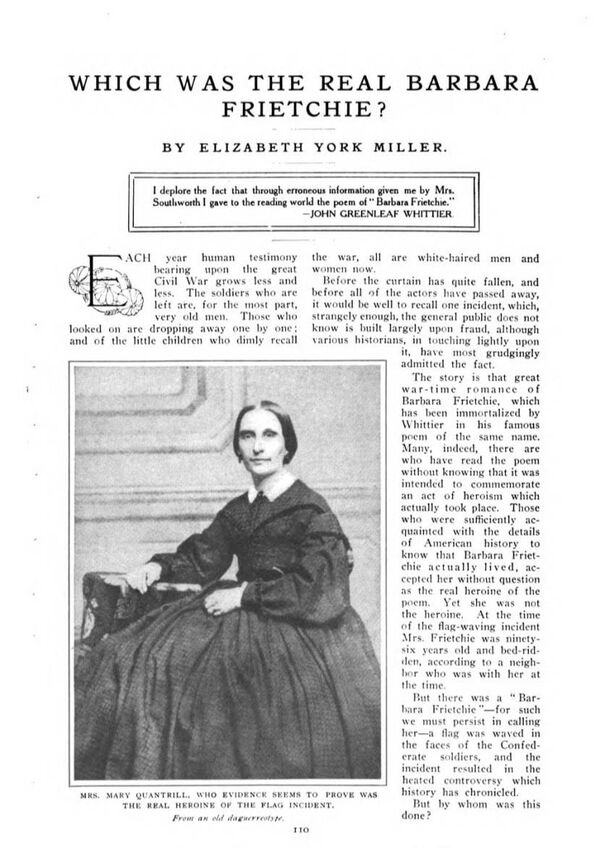

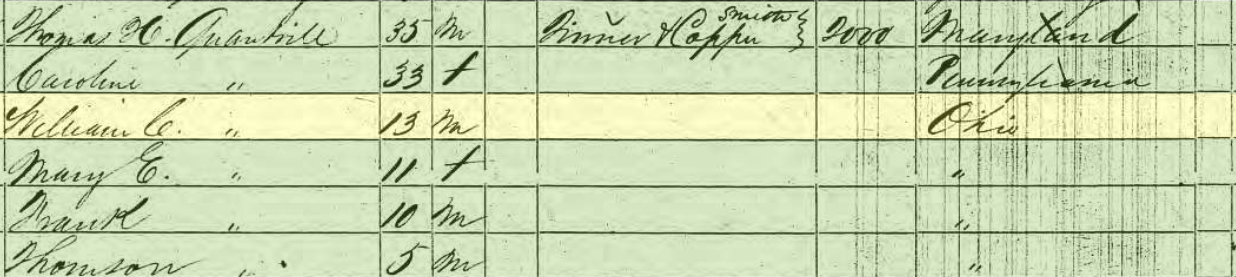

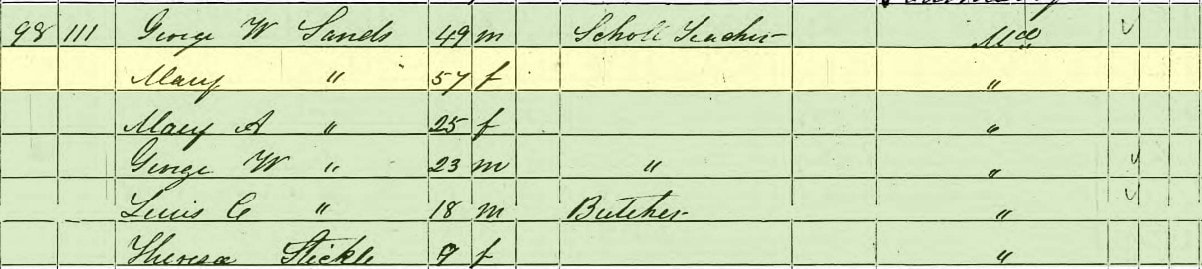

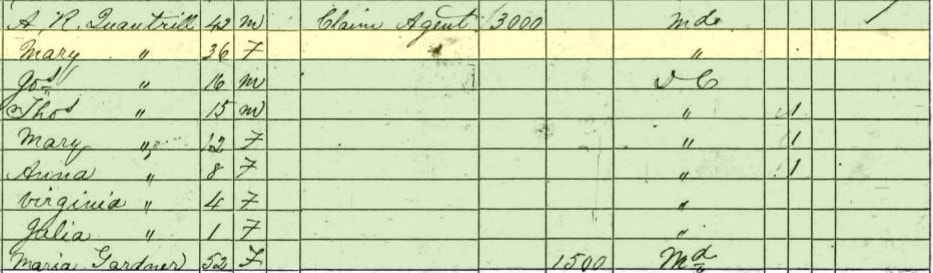

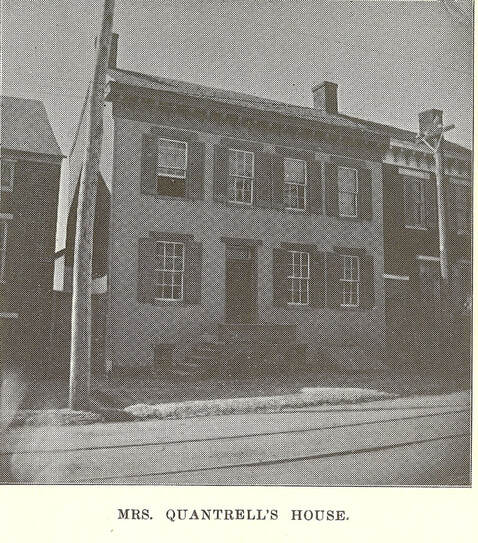

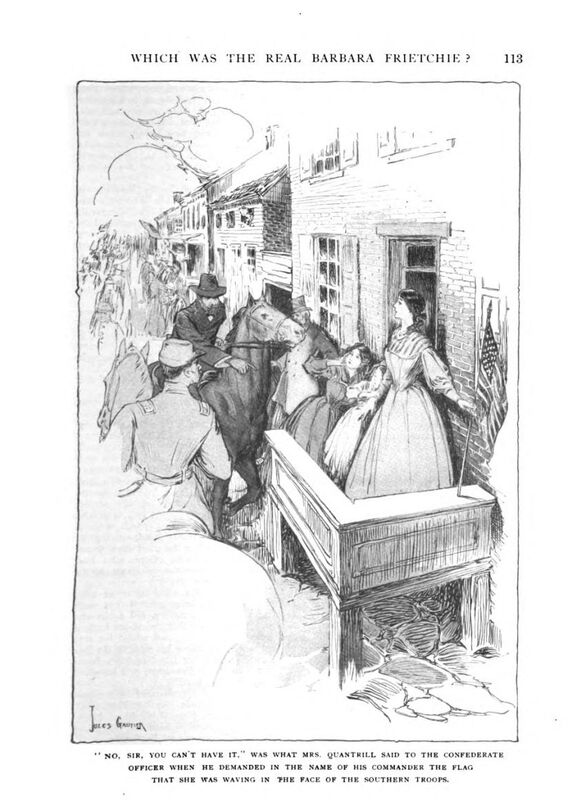

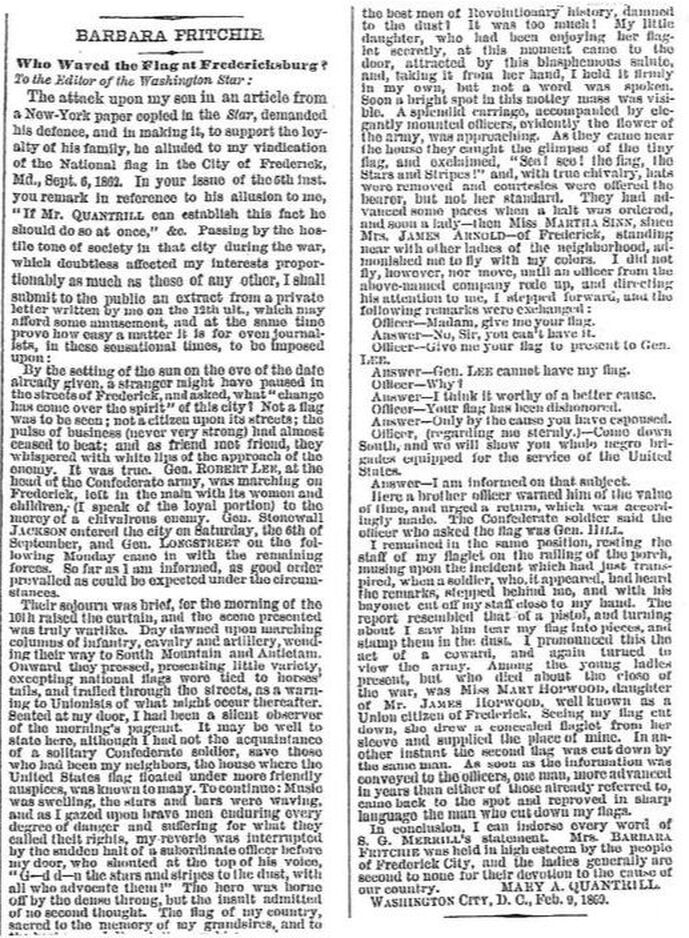

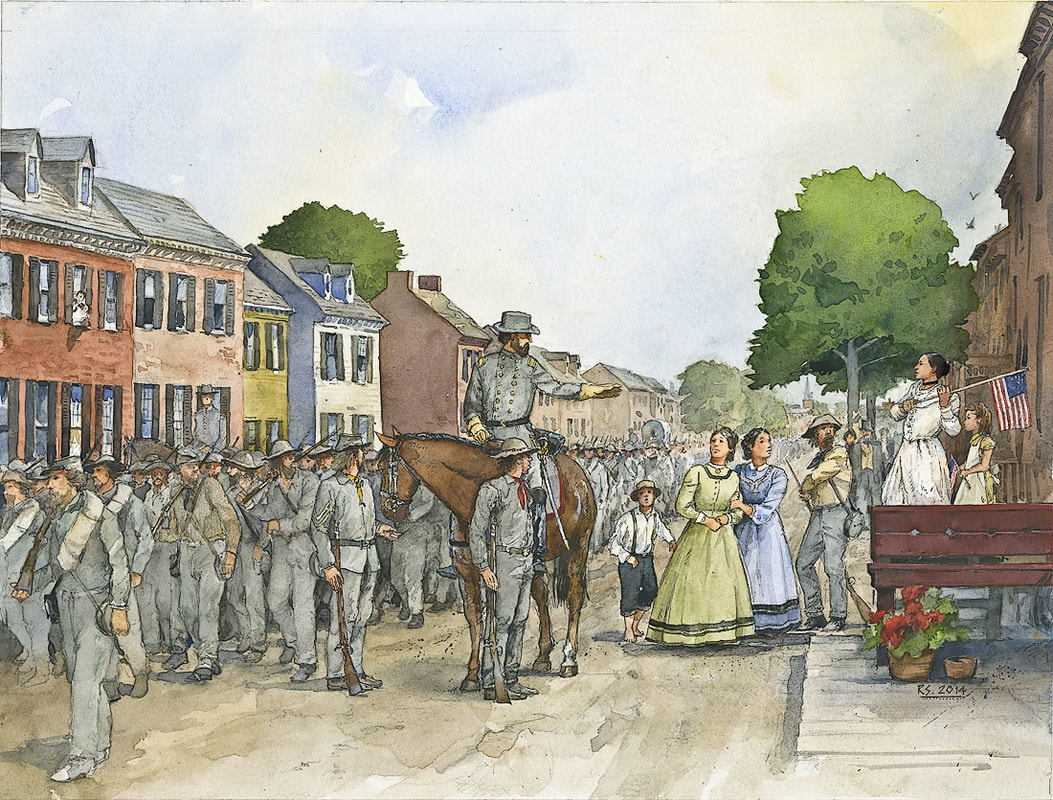

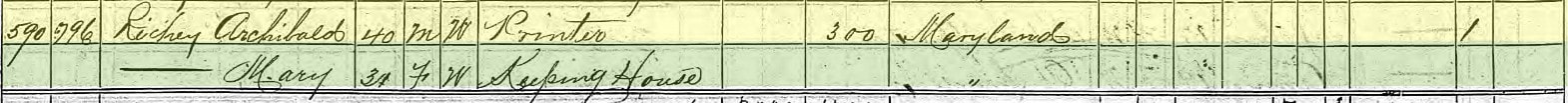

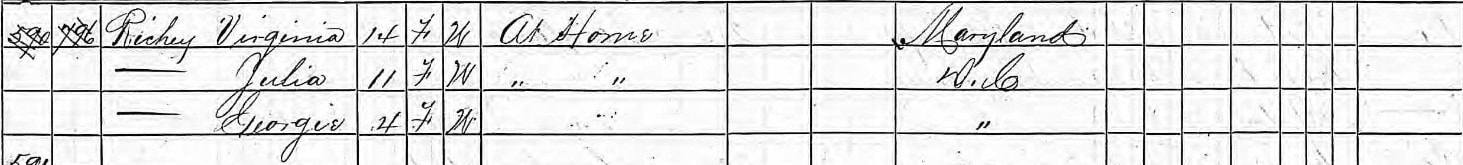

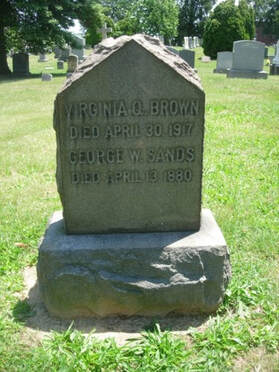

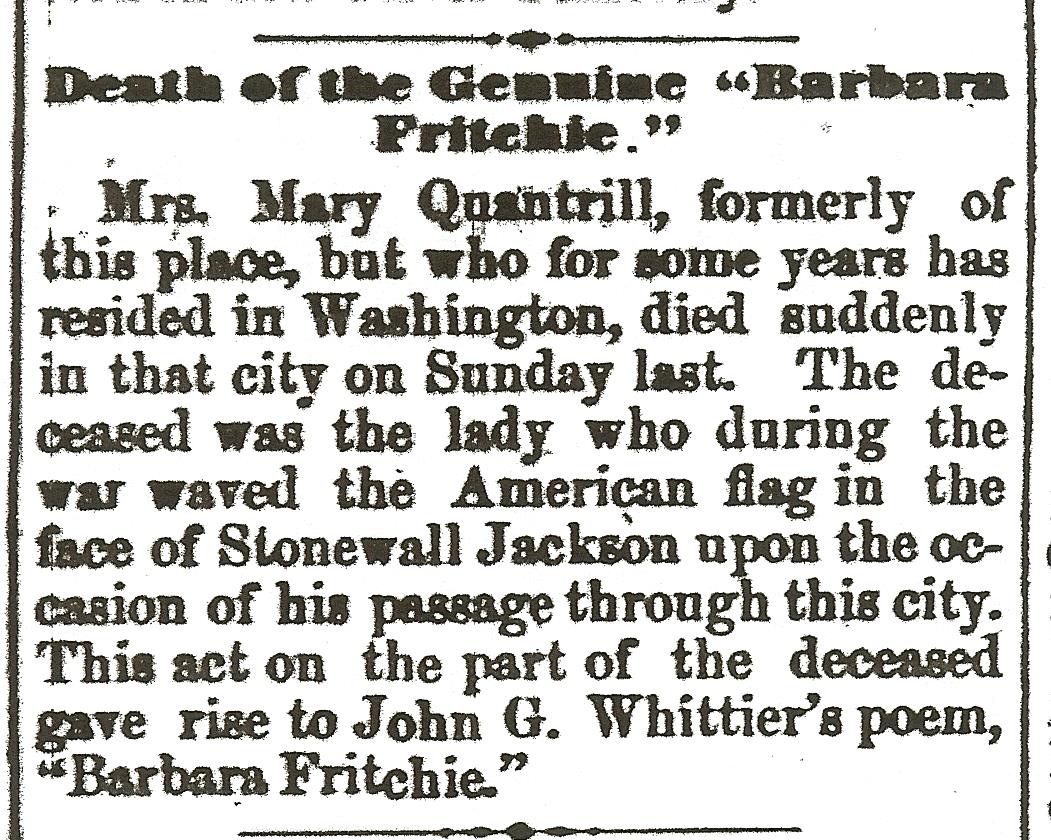

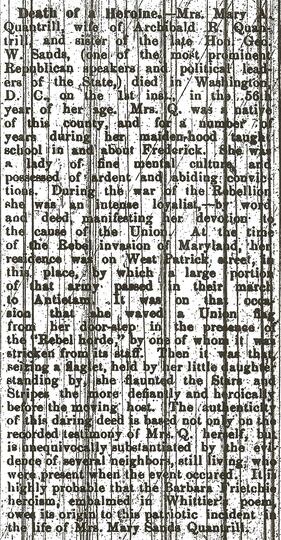

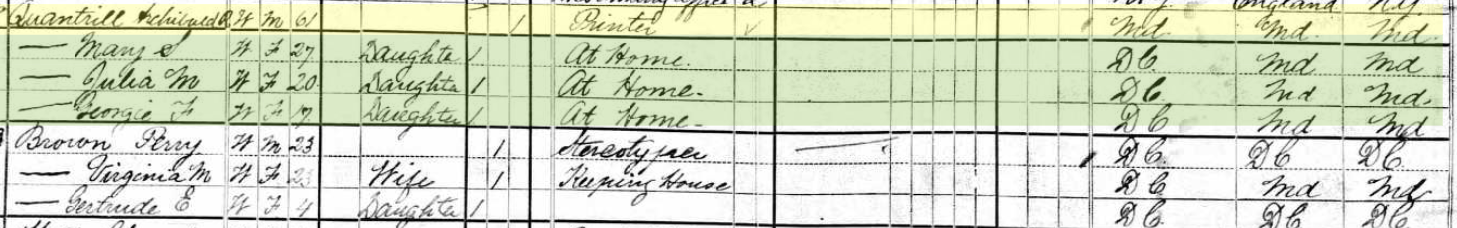

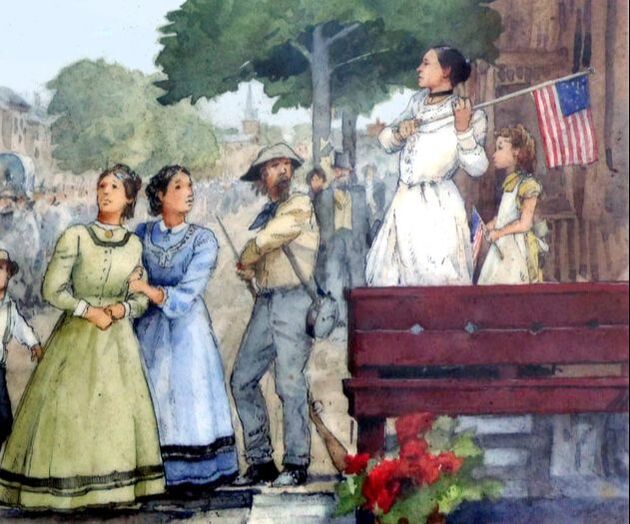

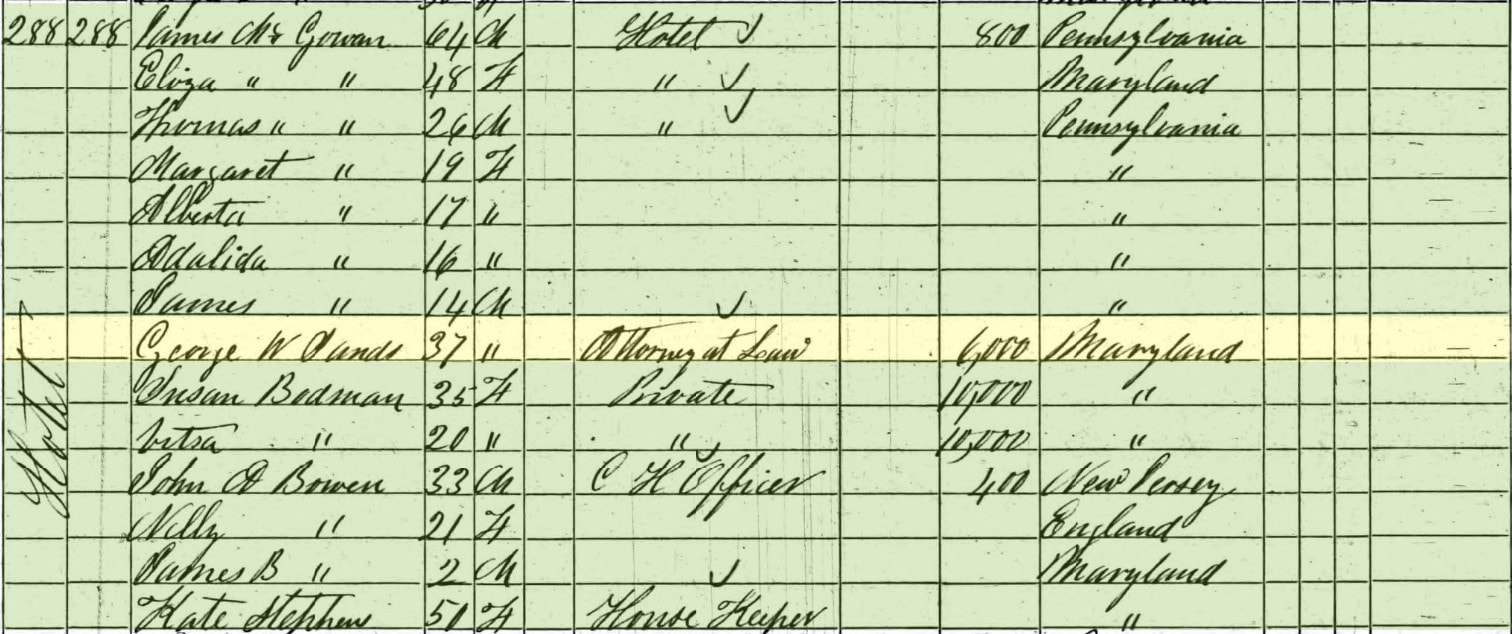

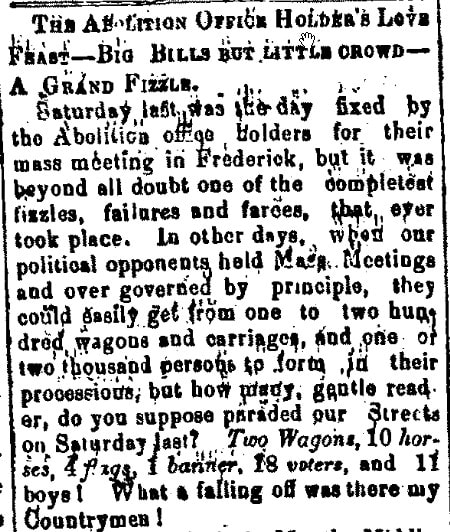

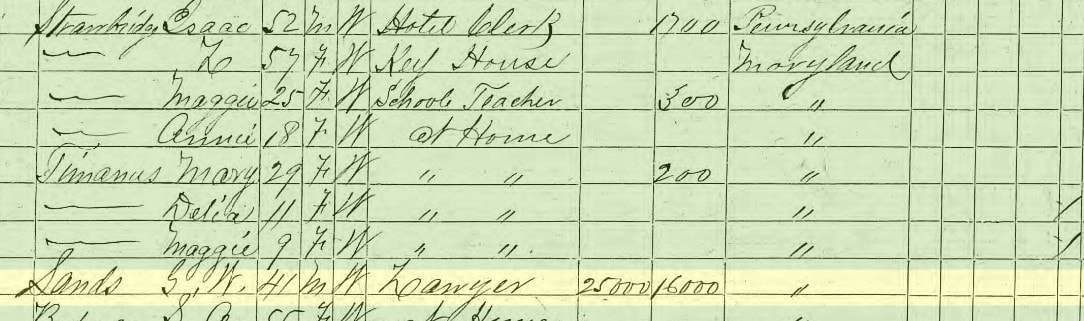

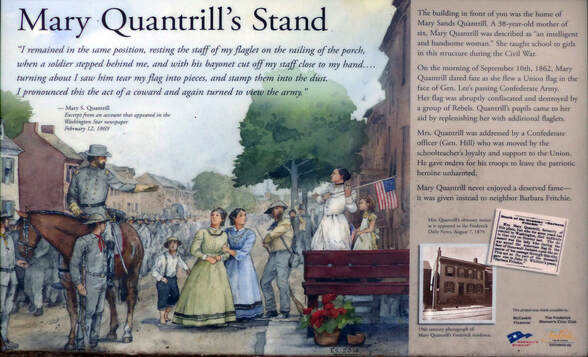

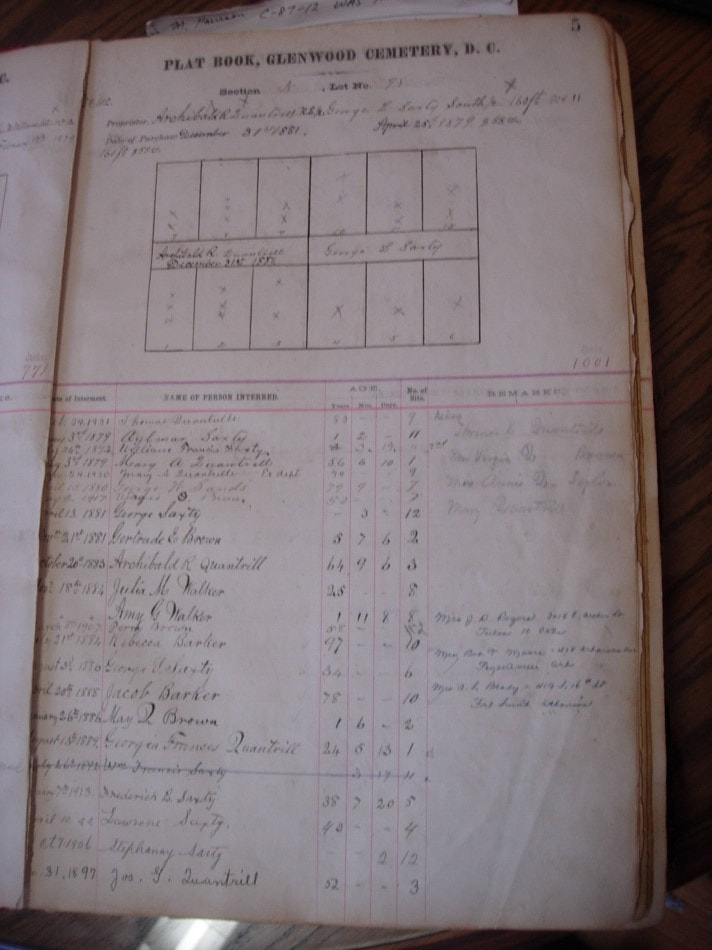

Well, I made it into this month’s edition of Frederick Magazine. Better yet, I was interviewed by writer Kate Poindexter in her fine story about Barbara Fritchie entitled “Legendary Tale.” Of course, I’ve been studying the nuances of the Fritchie episode for over 25 years, as it is has certainly been one of my favorite local research topics. Those who know me also are aware that I’m always up for challenging and busting age-old myths, and new ones too. But, I will confess, I get just as much satisfaction in proving myths true as well. As you may have seen (in the Frederick Magazine article), or already know otherwise, the Barbara Fritchie tale consists of many twists, turns and layers. It also possesses an interesting cast of supporting characters as well, featuring two other viable “flag-waving” understudies who could have easily been blessed with the lasting fame that Dame Fritchie has received. One of these ladies, Nannie (Nancy) Crouse, hailed from Middletown but eventually spent all her adult life a short distance from the cemetery as she lived in the first block of West South Street. Like Barbara, she is buried next to her husband (John Bennett) here in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery in Area B/Lot 2. The other “flag-toting Barbara” in question has always been shrouded in mystery and controversy. She also just happens to be one of my sentimental favorite individuals from our county’s rich heritage story. Her name is Mary Quantrill. Mary Quantrill lived a sad and desperate life after the events that played out in September of 1862 and were compounded by writers and reporters for many years to follow. Writer and humorist Mark Twain is responsible for saying: “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” This is so fitting to sum up the downfall of Mrs. Quantrill. You see, she was a victim of “cancel culture,” a century and a half before it was even a thing. This was the result of her situation not getting the press and embellishment garnered by Fritchie by a well-known poet who was deeply connected in the media of his time. However, there’s something about Mary that also “did her in” so to speak—a highly controversial surname. As rare as the last name of Quantrill still is, it had, at that time, gained an unpopular reputation thanks to a nephew living out west. Mary would never meet this individual during her lifetime. William Clarke Quantrill Quantrill's Raiders were the best-known of the pro-Confederate partisan guerrillas (also known as "bushwhackers") who fought in the American Civil War. Their leader was William Clarke Quantrill (1837-1865) and the gang included legendary outlaws Jesse James, brother Frank James, and Cole Younger. Early in the war, Missouri and Kansas were nominally under Union government control and became subject to widespread violence as groups of Confederate bushwhackers and anti-slavery Jayhawkers competed for control. The town of Lawrence, Kansas, a center of anti-slavery sentiment, had outlawed Quantrill's men and jailed some of their young women. In August 1863, Quantrill led an attack on the town, killing more than 180 civilians, supposedly in retaliation for the casualties caused when the women's jail had collapsed. Many of those slaughtered in broad daylight included young boys whose ability to hold a firearm resulted in their executions by “the Raiders.” William Clarke Quantrill was born at Canal Dover, Ohio. His father was Thomas Henry Quantrill, formerly of Hagerstown, Maryland, and his mother was Caroline Cornelia Clark, a native of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. The oldest of twelve children (four of whom died in infancy), Quantrill endured a tempestuous childhood. By the time he was sixteen, he found himself teaching school in Ohio. A year later (1854), his abusive father died of tuberculosis, leaving the family with a huge financial debt. Quantrill's mother had to turn her home into a boarding house in order to survive. During this time, Quantrill helped support the family by continuing to work as a schoolteacher, but he left home a year later and headed to Illinois where he took up a job in the lumberyards, unloading timber from rail cars. One night while working the late shift, he killed a man. Authorities briefly arrested Quantrill even though he claimed that he had acted in self-defense. Since there were no eyewitnesses, and the victim was a stranger who didn’t know anyone in town, William was set free. Nevertheless, the police strongly urged him to leave the town of Mendota (Illinois) where he was living. William Clarke Quantrill continued his career as a teacher, moving to Fort Wayne, Indiana in February 1856. The school district was impressed with Quantrill's teaching abilities, but the wages remained meager. Quantrill journeyed back home to Canal Dover that fall, with no more money in his pockets than when he had left. The frustrating experience seems to have struck a nerve with the young educator, as he would leave his classroom for a drastically different life—as a slave catcher. William Clarke Quantrill joined a group of bandits who roamed the Missouri and Kansas countryside and apprehended escaped slaves. Later, the group became Confederate soldiers, who were referred to as "Quantrill's Raiders.” It was a pro-Confederate partisan ranger outfit that was best known for its often brutal guerrilla tactics, which made use of effective American Indian field and combat skills. Quantrill is often noted as influential in the minds of many bandits, outlaws and hired guns of “the Old West” as it was being settled. In May 1865, Quantrill was mortally wounded in combat by Union troops in Central Kentucky in one of the last engagements of the Civil War. He died of wounds in June. Meanwhile, the James brothers formed their own gang and conducted robberies for years as a continuing insurgency in the region. Miss Sands William Clarke Quantrill’s grandfather, Captain Thomas Quantrill, spent considerable time in Frederick, primarily at the old Hessian Barracks grounds—land that once graced the fields located across from our cemetery’s front gate. A British immigrant who raised a company of soldiers in Hagerstown for the War of 1812, Captain Quantrill was described as “a brave soldier” who participated (and was injured) in the Battle of North Point in Baltimore in September, 1814. Thomas Quantrill would eventually move to Washington, DC with his family following his wife’s death. His oldest son, Thomas Henry Quantrill (William Clarke Quantrill’s father) would move to Stark Ohio to open a blacksmith business. Meanwhile, Thomas Henry’s younger brother, named Archibald Richey Quantrill, spent the bulk of his life in Washington DC, and would eventually go into the newspaper business, serving as a printer and compositor for the National Intelligencer. Archibald would marry his second wife, Mary Ann Sands, on February 8th, 1854. Mary Ann Sands was born in Hagerstown on January 21st, 1823. She was the oldest of three children born to George Washington and Mary Ann (Cronise) Sands who were married in Hagerstown in August of 1821. The family moved to Frederick County and resided in the northwestern part of the county first, eventually making their way to Frederick City. They would reside in a rented dwelling in the 200 block of West Patrick Street, just a short distance up the hill and west from the Barbara Fritchie household. This Sands family can be found back to the 1830 census as living in Frederick. Mary’s father was listed as a school teacher in the 1850 census and also as an esquire, serving later as a judge in the city court of Lacon, Illinois. He apparently had an interest in writing poetry too. The Sands family consisted of three children with Mary as the oldest, followed by two brothers: George, Jr. and Louis . The older of the two, George W. Sands, Jr. (@1824-1874), would become a lawyer and politician. Louis would relocate to Suffolk County, New York (Long Island) and work for the railroad and later became a patent dealer. Our lead subject, Mary Quantrill, married Archibald Quantrill in 1854 and can be found living in Washington DC’s 1st Ward in the 1860 census, with husband Archibald’s profession listed as that of a claims agent. The family at this time included six children, four of which from Mr. Quantrill’s first marriage to a Frederick native named Mary Westenberger. By September of 1862, Mary would be back in Frederick and residing in her earlier home of 220 West Patrick St. in Frederick. With the serious threat to the Union’s “Capital City” during wartime, Archibald thought it best that Mary and their children reside in Frederick with Mary’s elderly mother, as Washington was thought to be a prime target for Confederate attacks. Mary's father was living in Illinois at this time. The elder Mrs. Sands is listed as blind in the 1860 census, so perhaps Mary was also involved in care-giving for her mother as well. Regardless, Archibald Quantrill remained in Washington at this time. During the Civil War, several accounts say that Mary Quantrill operated a small private school from the home on West Patrick at this time. “Mrs. Quantrill at the time of the incident was a handsome woman,” says author William E. Connelly in his 1909 biography of William Clarke Quantrill entitled Quantrill and the Border Wars. Connelley goes on to state that Mary Quantrill was the “The True Heroine” of the day (not Barbara Fritchie), and that “Mrs. Quantrill appears to have been a woman of superior intelligence. She has for many years a teacher in Frederick, and was a frequent contributor to the “Evening Herald” of York (PA). It is said that she always felt keenly the injustice Whittier had done her.” Archibald Quantrill was proven wrong in early September, 1862, when Frederick was the first, major Northern town Gen. Robert E. Lee would bring his Rebel Army of Northern Virginia, after crossing the Potomac River. Many are familiar with the fact that the Confederates were basically given a cold reception here at that time, save for a smattering of southern-leading residents. Not getting the assistance he had hoped for, Gen. Lee headed west toward South Mountain and Washington County, utilizing the National Pike to transport his large fighting force. West Patrick Street was part of this great road, and Mary Quantrill would have a front row seat for the Confederate parade out of town which began in the early morning hours of Wednesday, September 10th. She even had her Union flag proudly displayed from a railing on her front porch to give the Rebel horde a proper “send-off.” Mrs. Quantrill made a lot of noise that particular day, and was certainly noticed by soldiers, officers and a number of her Patrick Street neighbors. However, she didn’t make a lasting name for herself—or should I say, she didn’t receive help from a Georgetown novelist (E.D.E.N Southworth) or Quaker poet from Massachusetts (John Greenleaf Whittier). In late summer of 1863, these literary luminaries had an Abolitionist agenda to tend to, and fast-tracked a work of prose that featured Mary’s feisty neighbor—the nonagenarian who lived a football field’s length down the street whose name rhymes with “bitchy.” Yes, the name of Barbara Fritchie (or Frietchie) would ring true as not only Frederick’s heroine, but that of a nation—or at least the part of it that was still intact as the Union at that time. So, what exactly transpired on September 10th, 1862 in the 200 block of West Patrick Street? Well I have enclosed a vital article which appeared in the Washington Star newspaper (Washington D.C.). This particular letter to the editor was re-published in the New York Times on February 15th, 1869. A pretty colorful scene, wouldn’t you agree? Regardless, Dame Fritchie had died in December, 1862 and never lived to enjoy (or possibly refute) her fame, as she died at age 96, eleven months before the poem was published in the Atlantic Monthly Magazine October, 1863. The above newspaper clipping from 17 years later (1869) provides incredible context to Mary’s interaction with boisterous Confederates on that “Cool September morn.” Mary’s son, Thomas C. Quantrill had been mistakenly admonished in a Washington newspaper for being associated with the infamous Missouri Raider, William Clarke Quantrill. Thomas pointed out the error and exclaimed that he knew the man only as well as the general public knew the man. Thomas offered that he had volunteered for US Army duty in advance of the First Battle of Bull Run but was rejected due to physical limitations. In expressing his devotion to the Union, and not Confederacy, he made mention of his mother's heroics in Frederick on the morning of September 10th, 1862. He thought his mother had stood humble and tight-lipped long enough and should get at least some credit and accolades for her heroic role played in Frederick during the Civil War. This renewed interest in Barbara Fritchie came at a time when the original Fritchie house was being razed by the Frederick municipality in an effort to combat Frederick flood measures for Carroll Creek. Mary Quantrill had moved back to the nation’s capital in either 1863 or 1864. She was unable to escape the constant adoration her former neighbor (Barbara) continued to receive posthumously. And amazingly, no one definitively saw Barbara harass the Confederates on that fateful day, including our famed diarist, Jacob Engelbrecht, who lived directly across from the Fritchie house. He would make a journal entry in October of 1863 upon reading Whittier's Barbara Frietchie poem in a newspaper, commenting that this was the first he had heard of such an event and puzzled as he had watched the Confederate Army pass his door that entire day without a monumental incident occurring across the street. Mary Quantrill lived a lonely and broke life in her later years. In my initial research on Mary Quantrill back in 2007, I lost track of Mary save for the newspaper items I had found above. I could not find her in the 1870 US census. After countless attempts utilizing the popular internet site Ancestry.com, I finally found the family in question under the name of Archibald and Mary Richey. The infamy associated with the Quantrill family name, thanks to the exploits of William Clarke Quantrill, must have been too overwhelming for a peaceful existence free of criticism in the nation’s capital. Archibald’s middle name would serve as a less auspicious identifier. Mary Ann (Sands) Quantrill died on August 1st, 1879, and I have surmised it was likely from depression and a broken heart. The actual cause on the death certificate is cardiac-related so I’m not entirely off in my medical assessment. Mary is not buried in Mount Olivet, but rather Glenwood Cemetery in Washington, DC. Sadly, her “Story in Stone” has never been fully told, as she is buried in an unmarked grave. As a matter of fact, most of her immediate family has the same predicament. I have often wondered if this was a result of “cancel culture” for being thought of as a “want to be” hell bent on riding on Barbara’s coattails, or worse yet trying to steal the fame belonging to the defiant and deceased 95 year-old? Or were her detractors simply upset with that pesky Quantrill name, and the familial relation to one of the baddest men in the entire country? I think it was a lethal combination of both. One of the most gratifying finds in my “search for Mary Quantrill” came in the form of obituaries in the Frederick papers. As not to influence your judgment, I will simply present both from our two Frederick newspapers of record of that time. By the 1880 census, the Quantrill family name would reappear in print again as Archibald and three daughters (Mary, Julia and Georgie) are found living on K Street in the Northeast part of the District of Columbia.

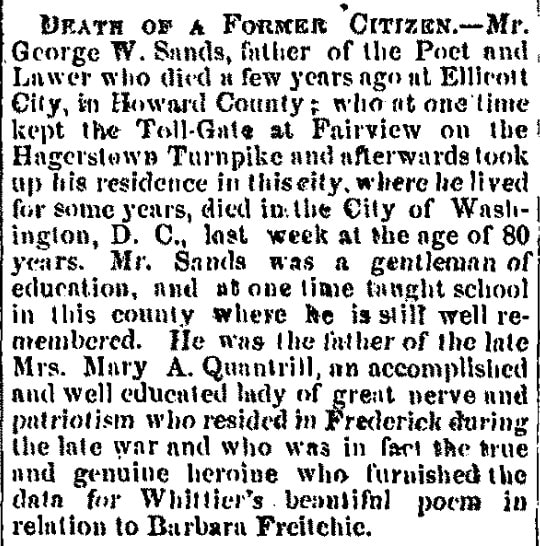

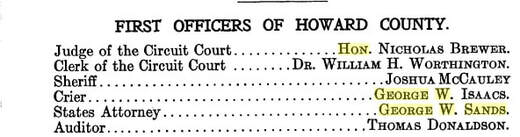

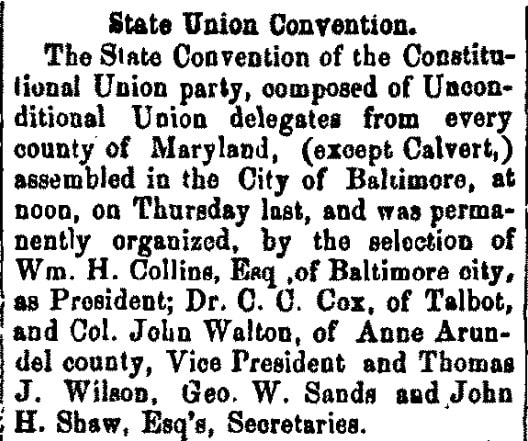

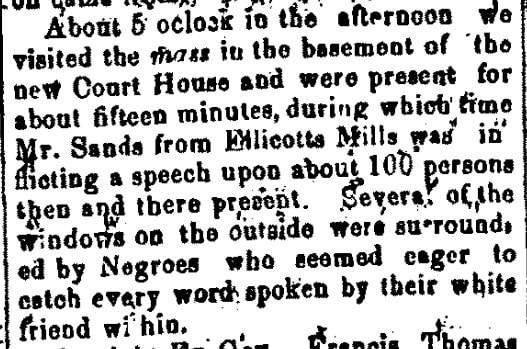

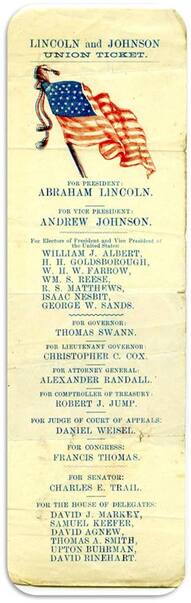

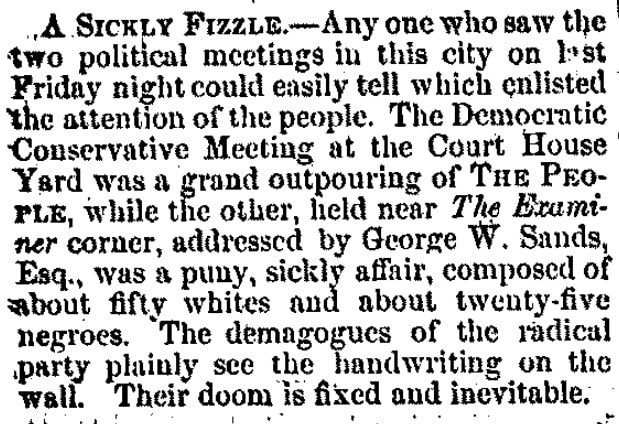

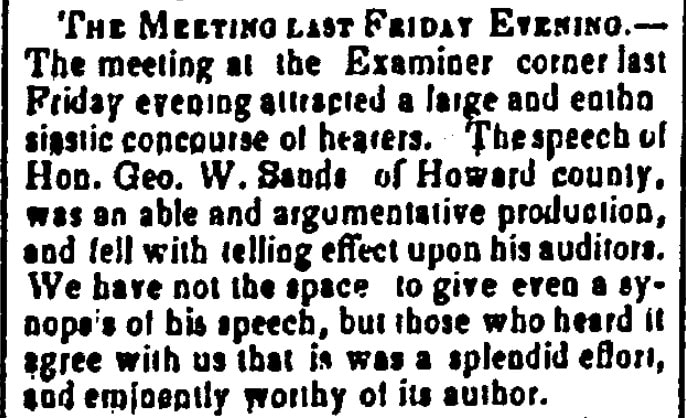

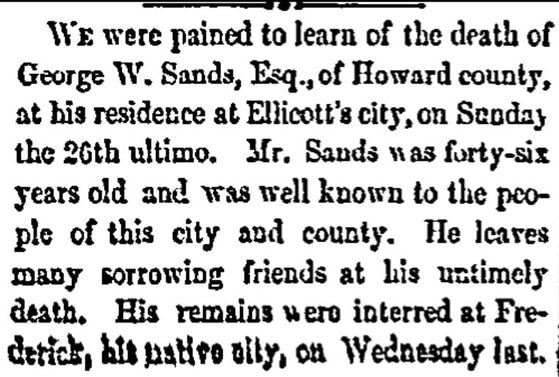

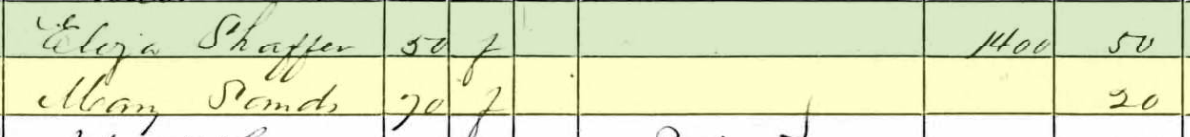

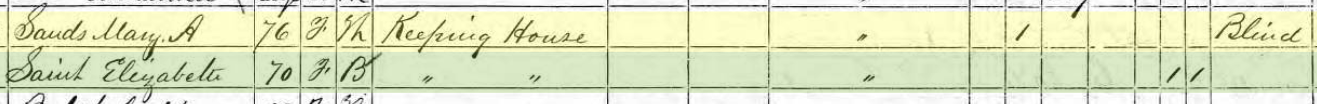

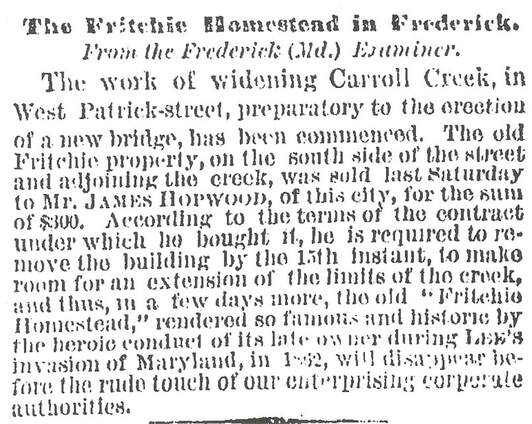

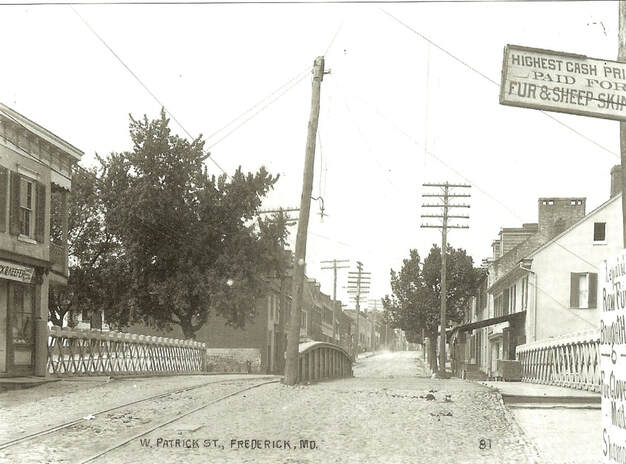

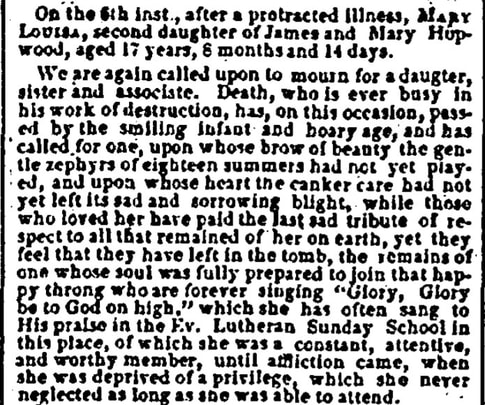

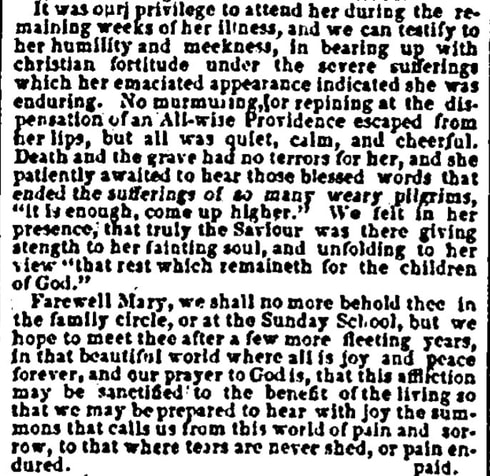

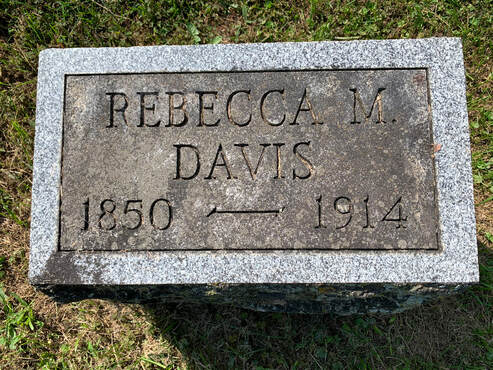

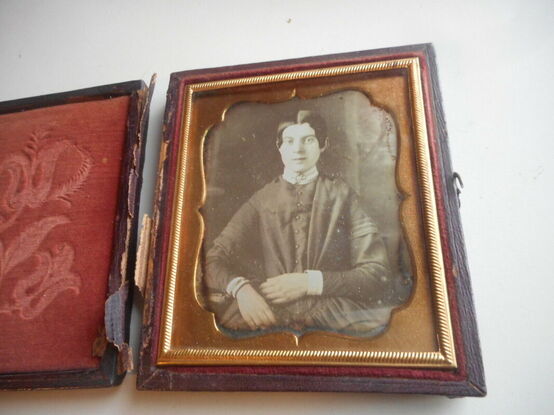

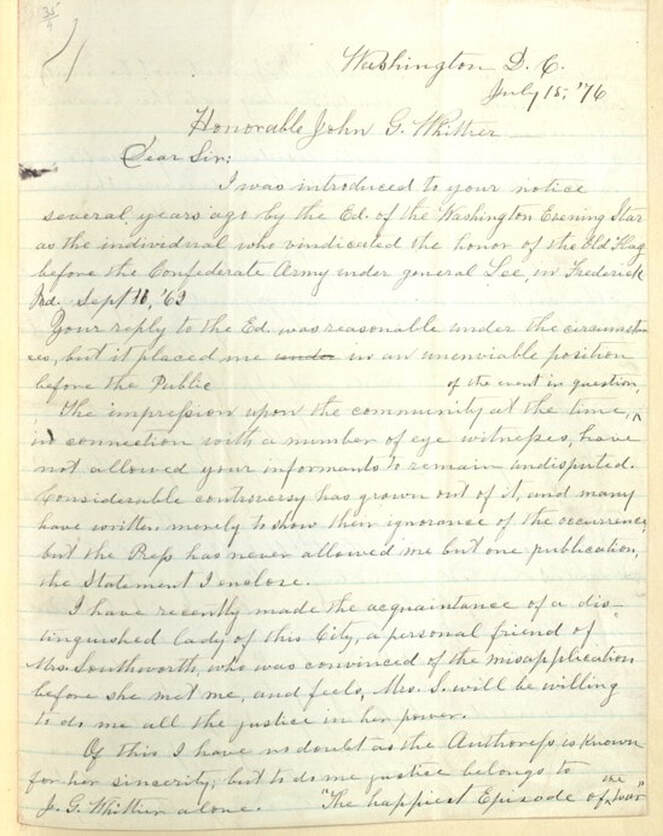

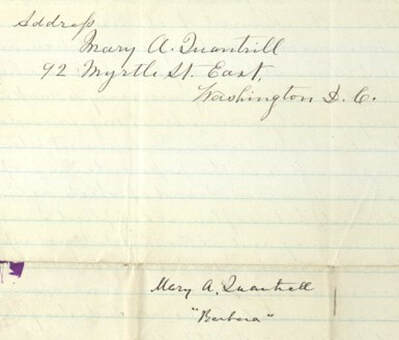

Mount Olivet and Mary Quantrill What we do have here in Mount Olivet are some close connections to Mary Quantrill. One of which is her brother, George W. Sands Jr. Mr. Sands had been practicing his legal career in Howard County and would become States attorney for the county by the mid-1850s. He would be elected state delegate from that county and, unlike his midwestern cousin William Clarke Quantrill, served as an outspoken Unionist and opponent to slavery. Sands would participate as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1864 and was quite active in constructing the third state constitution of Maryland which abolished slavery, taking effect November 1st, 1864. He was also a US collector of internal revenue under President Lincoln. George W. Sands, Jr. died on July 28th, 1874 and was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 156 Strangely, he too is buried in an unmarked grave. Our records show that he is definitely here in space #3, and has two unknown individuals buried to each side of him. Could one of these graves be his (and Mary’s) mother (Mary Ann Sands)? I continue to search for the answer as our cemetery records books cannot confirm Mary Sands being here, or anywhere else in Frederick. She is definitely not recorded being at Glenwood in DC with husband George, Sr. or her daughter and the rest of the Quantrill family. Mary Sands is found in the census of that year and residing with a woman named Eliza Shaffer, perhaps a relation of some sort. Mrs. Shaffer was widowed at the time. A decade later, Mrs. Sands was living with a 70 year-old black woman named named Elizabeth Saint. I decided to see if Mrs. Shaffer was buried in Mount Olivet and I discovered from our records that an Elizabeth Matthews Shafer was buried here in March,1867, but her gravesite is listed as unknown. So I ask the question again, could Mrs. Sands and Mrs. Shaf(f)er be buried in Area H/Lot 156 with George W. Sands, Jr.? I found Mrs. Sands' husband was elsewhere during both these census years, but I haven't found him yet. I'm assuming he was either in Illinois, or in Ellicott City as his obituary claims he was a one-time resident of the Howard County town.  Grave of James Hopwood Grave of James Hopwood The Hopwoods As I said earlier, the Sands home was on the south side of the 200 block of West Patrick Street, about 50 yards west of the Bentz Street intersection. I found that the family had been renting this home for years from landlord, James H. Hopwood (1811-1883). Mr. Hopwood was one of the city’s busiest construction contractors. He also was heavily connected to the flag-waving incidents at hand. James and wife Mary Ann Hopwood lived a few doors west (234 W. Patrick St.) from Mary Quantrill and were the parents of a few of Mary Quantrill’s students. Of particular interest is Mary Hopwood (b. 1847), Mary’s oldest student and referenced by name in Mrs. Quantrill’s first person narrative of her experience on September 10th, 1862. Shortly after Barbara Fritchie’s death in December, 1862, her heirs sold their famous relative’s house to a Mr. George Eissler for use as a dyeing and scouring business. In late July of 1868, a disastrous flood washed away part of the old Fritchie property and caused the home to be condemned by the city. Mr. Eissler moved to a new home across the street, and the Fritchie house was put up for auction. The town fathers under Barbara’s Southern leaning grandnephew, Frederick Mayor Valerius Ebert, were interested in widening Carroll Creek at this location. The original Fritchie household was purchased from the city for $300 in early April and, upon the terms of sale, was fully dismantled and removed by May 15th of 1869 amidst the protest of the Frederick Examiner’s editor and others around the country. Jacob Engelbrecht even comments on this in his diary. It is fascinating to note that the sole bidder and eventual new owner of the property would also be the man in charge of the demolition operation of said heroine’s home. Simple “addition by subtraction” as James H. Hopwood’s wrecking ball would help initiate flood control overtures in an effort to help tame Carroll Creek. I’m thinking that Mr. Hopwood and other leaders in town had simply heard enough about Barbara Fritchie over a seven-year span. Mr. Hopwood was awarded the 1869 bid to dismantle the original Fritchie house and, afterwards, would build a two-story brick house on the property and was responsible for building a new wooden bridge over Carroll Creek at this location. He was surely in the Quantrill camp of loyalty as his daughter had been a hero as well, standing beside Mrs. Quantrill in her defiance of the Confederate Army earlier in the decade. The bittersweet part of the story here is that Mary died at age 17 on October 6th, 1864. She would be forgotten by the history books as well. Mrs. Davis Some of the Ebert children (Barbara Fritchie’s grandnieces) were also students of Mrs. Quantrill and under her tutelage on that fateful day in September, 1862. T.J.C. Williams History of Frederick County, published in 1910, contains a biography that makes specific reference to Mrs. Quantrill as a teacher. This can be found in the biography of Samuel Davis, a miller and storekeeper in Fountain Mills (New Market district). It is stated that he was married to Rebecca Maria Ebert (b.1850), a former student and next-door neighbor to Mary Quantrill. At the end of his bio, the author makes a point to say: “In the connection it might be said that Rebecca Ebert, (daughter of John Ebert and second wife Ann Fritchie), was a pupil of Mary Quantrill, who was really the woman who waved the flag which occasioned Whittier’s famous poem.” Ironically, Mrs. Davis’ maternal grandmother was Maria Rebecca (Fritchie) Ebert, sister of John Caspar Fritchie. John Caspar Fritchie was Barbara (Hauer) Fritchie’s husband of course. You may also recall Rebecca (Ebert) Davis’ brother named William Augustus Ebert of whom I wrote a story titled “The Lost Whitesmith” back in November, 2020. William accidentally shot himself while performing a repair on a pistol. The wound proved fatal and his grave can be found in the same plot of his sister (Area G/Lot 202). I missed out on bidding successfully for his photo which was up for auction on eBay. However, another photo of a young girl was up for auction at the same time from this family. I assume that this could be Rebecca Ebert in earlier days of the 1860s, however it could have been another sister as well.  Nixdorff's Affidavit Mary’s first-hand account is corroborated by another neighbor, a man named Henry M. Nixdorff who operated a general store a half block east of Mary’s home on West Patrick Street. The location was the same as the former Jennifer’s Restaurant (owned by Jennifer Dougherty), and most recently known as Le Parc Bistro. Mr. Nixdorff was the son of one of our War of 1812 soldiers buried in the cemetery. He was an intimate friend of Mrs. Fritchie and felt compelled to write a book in 1887 entitled Life of Whittier’s Heroine Barbara Fritchie. In this work, the author defended Ms. Fritchie’s real-life persona as a patriotic woman, kind neighbor and God-fearing Christian above all. This offering, with its personal anecdotes and colorful depictions of the aged town character, countered the more fact driven/no nonsense book written by Caroline W. H. Dall entitled Barbara Frietchie: A Study. Nixdorff’s book which underwent subsequent re-publishings, included an account of the Quantrill event that goes as follows: “I happened to look up the street, and saw a very intelligent lady, a neighbor, standing on her front porch, with a small Union flag in her hand waving it and making apparently the most earnest remarks to a Confederate officer who had ridden his horse over on the pavement up to the porch where she was standing. I was afterward assured by those who had the pleasure of being present that such glowing words of patriotism fell from the lips of Mrs Quantrell that the officer looked on and listened with wonder and surprise, and whilst he was present would not allow his men to do her the least of harm. After his departure however, some of the soldiers belonging to the army came and knocked the flag from her hand, breaking the staff into several pieces.” Mr. Nixdorff even went so far to have five neighbors, who had apparently witnessed the event up close and personal, sign a statement that said his account was genuine. I found all five of the signers buried here in Mount Olivet: Mrs. Matilda (Hauer) Fleming (1820-1887), Mrs. Harriet “Hallie” M. (Fleming) McDonald (1848-1906), Mrs. Kate (Hauer) Cashour (1850-1891), Nicholas Hughes Fleming (1852-1913), William W. Fleming (1854-1926). Mr. Nixdorff is buried in Area B/Lot 1. This man was connected to all three flag-wavers as he was close friends with Barbara Fritchie as mentioned, and helped exonerate Mary Quantrill. The last connection is to Nannie (Crouse) Bennett, who just happens to be buried in the next lot over. Another neighbor and eyewitness who kept the heroic story of Mary Quantrill alive for friends and later generations of family was a lady named Laura A. (Hiteshew) Railing (1843-1923). Mrs. Railing lived with her husband George across the street from the Sands home on West Patrick Street. She told the story to whoever would listen up to her dying days. These witnesses to history just saw Mrs. Quantrill as a mirage, a woman who displayed great bravery and then suddenly disappeared shortly thereafter, never to return. She was an enigma of sorts to those who heard the story. One more nugget I’d like to add. In the year 1876, Mary fruitlessly tried to get aid from author John Greenleaf Whittier in the form of clearing her name and admitting that she perhaps was owed the same fame as Ms. Fritchie. Three years before her death, she was in poor health, and literally destitute as being unhire-able due to the court of public opinion and favor which had turned against her. I saw this letter with my own eyes in the collection of the Quaker Reading Library at Swarthmore College in Philadelphia. The piece was exquisitely written by this highly gifted woman. My heart sank at the very end as it seems that Whittier, himself, inscribed a solemn sobriquet beneath Mary's name on the back of the letter—“Barbara.” As stated earlier, Mary’s final resting place is an unmarked grave in Glenwood Cemetery in Northeast Washington, DC, off Lincoln Ave. Look for the lone stone on the Quantrill lot belonging daughter Virginia (Quantrill) Browne, who participated in the underplayed flag-waving incident as well. A few years ago someone pointed out to me that Mary’s grave had been added to the internet’s FindaGrave site within Glenwood’s interments. He said that I had a hand in this occurrence which made me quite happy. As I said, I have developed an incredible fondness for this unsung historical figure of Frederick’s past. If only she was buried in Mount Olivet, I could do more. I’ve been to her gravesite three times down at Glenwood. The last time was back in 2015. It was a Sunday morning and I had just dropped off my stepson Jack at Reagan National as he was flying to Orlando with classmates for a marching band trip at DisneyWorld. When I drove closer to the Quantrill family plot, snow flurries began falling. I parked, and walked over to the hallowed ground of my old friend from countless hours of study and deduction. I immediately felt the pity for Mary all over again. As I stood there, I felt inclined, however, to tell Mary a bit of good news since I had last visited her. Thanks to some grant money I had obtained, and a generous contribution from a local financial planner (Scott McCaskill) with help from the Frederick Womens Civic Club, there was now an interpretive wayside marker in front of her old house in Frederick (220 W. Patrick St). Her story could now be learned by those passing by. As I turned to walk away, I could have sworn I heard a woman’s voice faintly say, “That’s great history boy, now work on getting me a proper tombstone.”

2 Comments

Kathleen and John Spry

9/19/2021 11:09:37 am

Really enjoyed this article. Thank you.

Reply

Gloria Swift

9/19/2021 05:13:59 pm

A wonderful article! Thank you! It's always a disservice when a true story is overshadowed and/or taken over by one of fiction! Now, we just need to get the rest of the folks of Frederick on board with the REAL story and to stop perpetuating a myth!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed