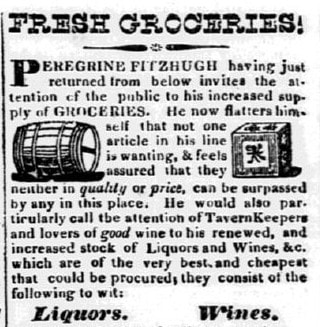

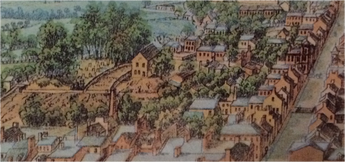

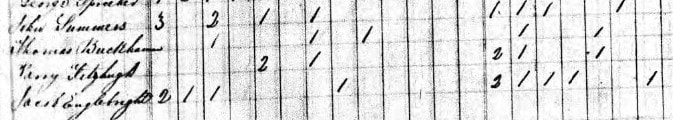

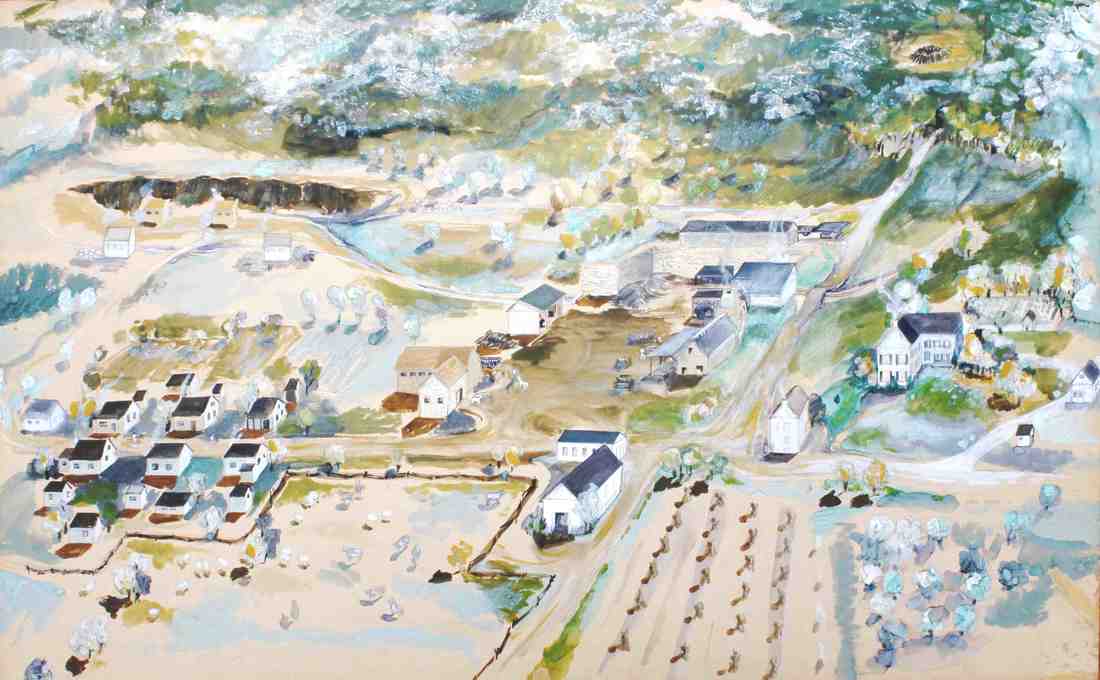

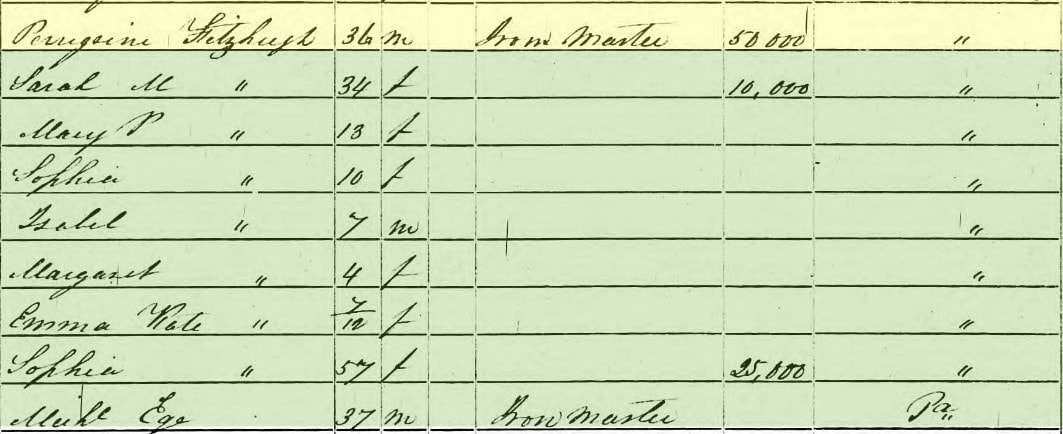

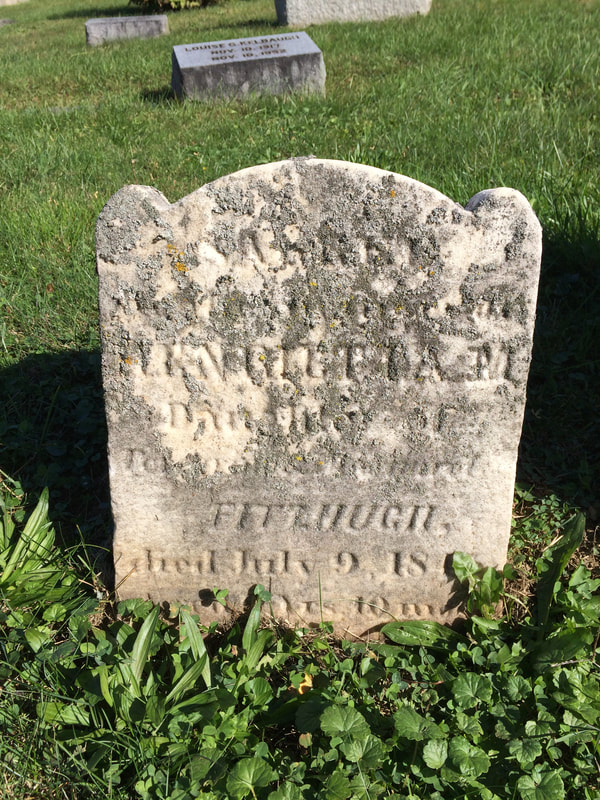

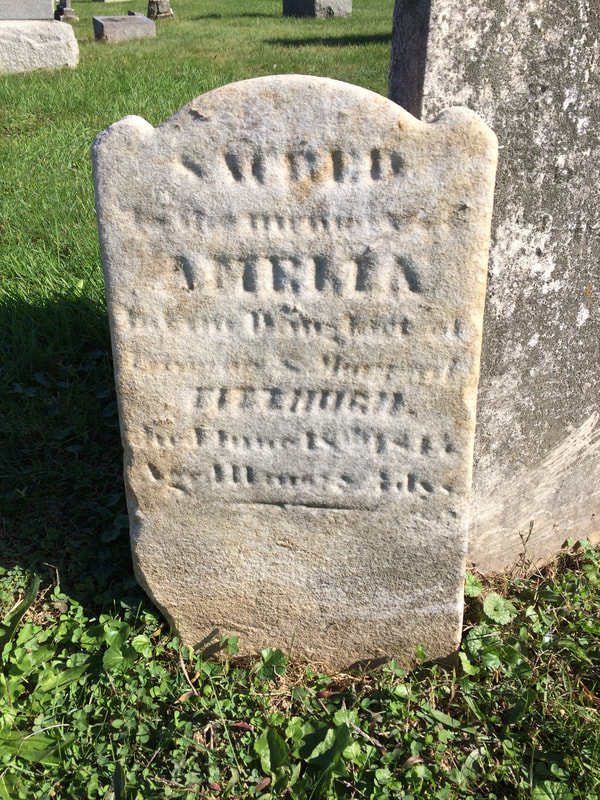

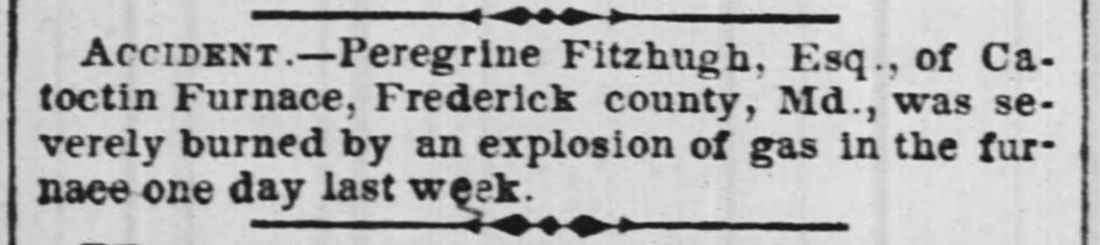

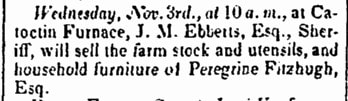

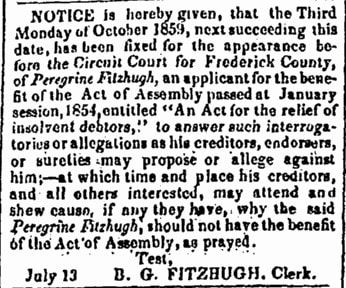

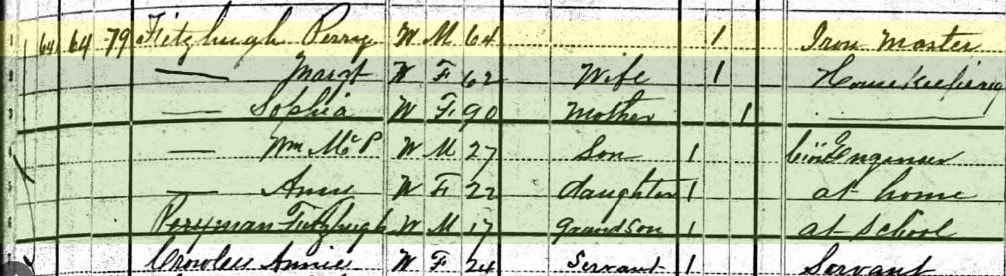

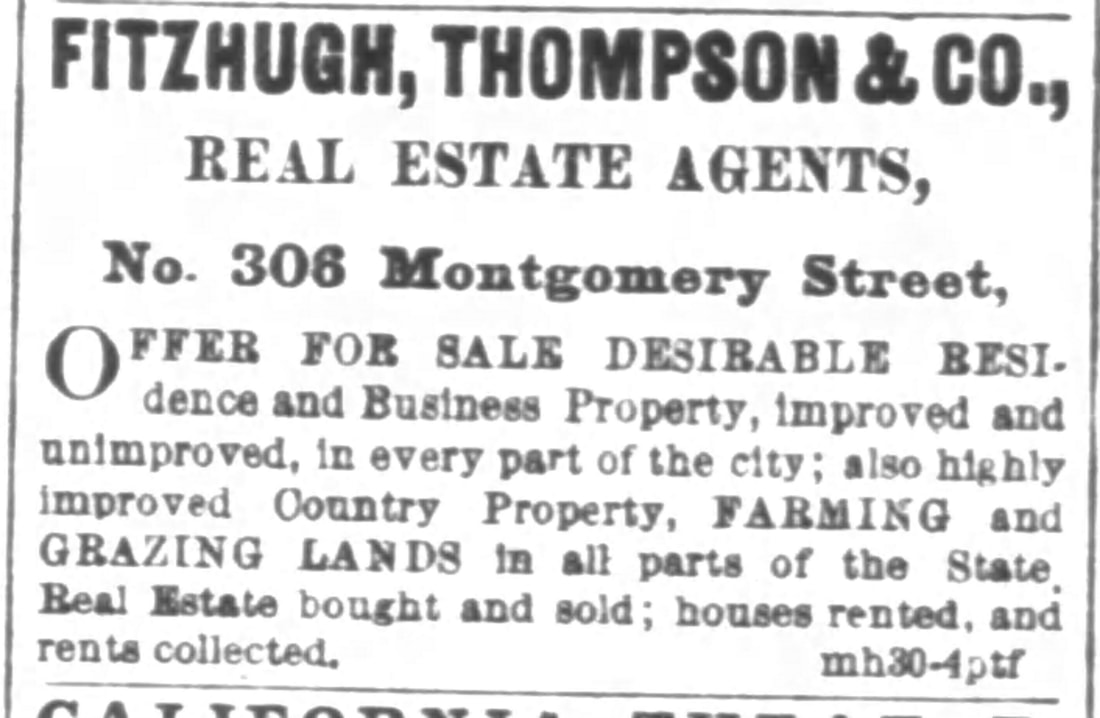

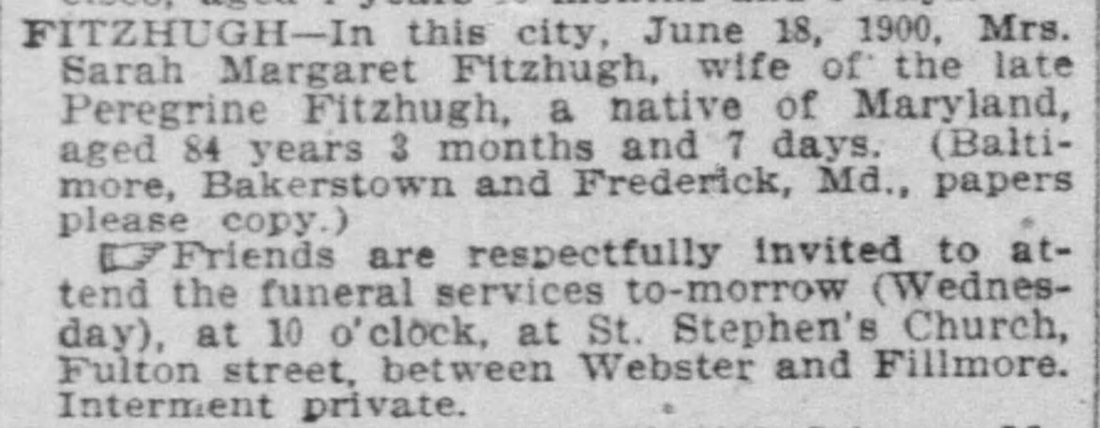

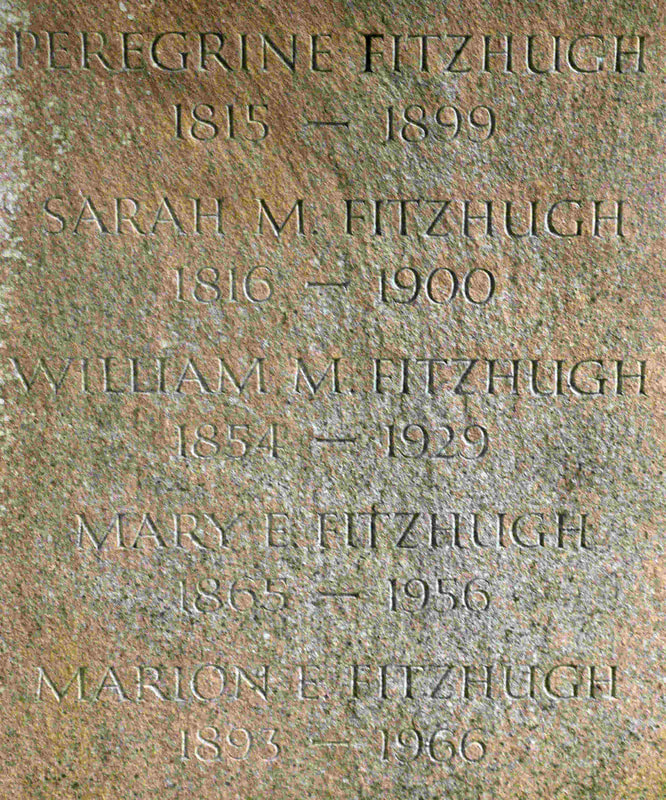

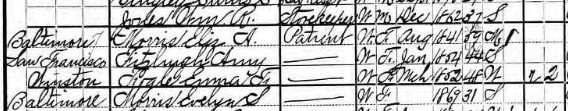

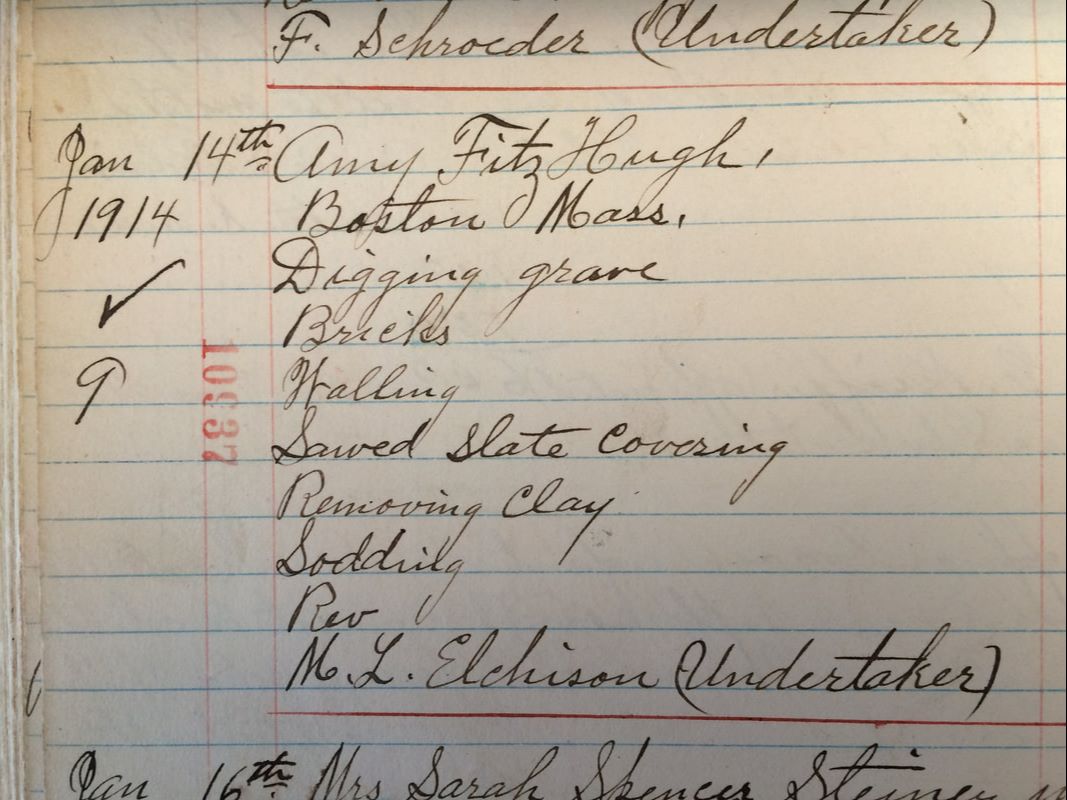

I borrow the title of this week’s article from a popular guided night hike that occurs this time of year up at the historic Catoctin Iron Furnace and surrounding village. Located just below Thurmont, this seasonal offering features tour stops at historic structures such as workers’ homes, an ancient slave cemetery, Harriet Chapel, the remains of the Ironmaster’s House, and best of all, “Isabella”—the iconic second stack structure of the once-booming pig-iron furnace operation. Here in Mount Olivet Cemetery, a trio of lonely looking gravestones can be found in the southernmost section of Area H. They have direct connections to the north county furnace industry and encompass a sort of transient spirit, one that can be traced to their removal here in the cemetery’s first year of existence. This was 1854, and two of the graves within Lot #416 were opened on October 24th of that year. Received were two young daughters of a prominent businessman named Peregrine Fitzhugh. Perhaps I perceive “loneliness” because these women are resting some 2,775 miles from their parents and siblings, interred on the other side of the continent.  The bust of Thomas Johnson, Jr. sculpted by local artist and architect Joseph Urner in 1926. The bust of Thomas Johnson, Jr. sculpted by local artist and architect Joseph Urner in 1926. To give some context, I want to bring into the story former Frederick resident Thomas Johnson , Jr. (1732-1819). TJ, as he is often referred to, has his name on a local high school (my alma-mater), a county park and children’s museum (Rose Hill Manor), and a roadway in town which contains a cornucopia of medical offices and offerings—Thomas Johnson Drive. More importantly, Mr. Johnson rests in peace in Mount Olivet. His grave monument lists his many accomplishments in life: lawyer, planter, Continental Congress member, Revolutionary War veteran, Maryland’s first elected governor, surveyor of the District of Columbia and US Supreme Court justice. Johnson was also a successful businessman, and we generally give him credit for creating, and operating, the famed Catoctin Furnace. The truth is that Thomas’ brother, James, (also buried here in Mount Olivet), was the true force behind the furnace’s first iteration, and was followed by a long list of subsequent operator/owners up through the early twentieth century. One of these “unsung heroes” was the gentleman mentioned above, Peregrine Fitzhugh. A Wandering Man For starters, I had never seen the name Peregrine before. So I looked it up in the online dictionary. It is defined as: “having a tendency to wander.” After looking into this man’s past, I can vouch that Peregrine Fitzhugh certainly did his share of “wandering” over his lifetime. Born on the 8th of February, 1815, Peregrine Fitzhugh was the son of William Fitzhugh (1784-1819) and Sophia Claggett (1792-1884). He was named for his grandfather, a wealthy planter of Virginia and officer in the American Revolution. Peregrine’s grandmother, Elizabeth Chew, was a native of early western Frederick County (today’s Washington County). These people came from Chewsville, located midway between Hagerstown and Smithsburg. The hamlet obviously took its name from the Chew family, but some old histories say the place name is derived from a shortened, slang version of Fitzhughsville—hence Chewsville. In the early 1840’s, the Catoctin Furnace was owned by John McPherson Brien (son of former Catoctin Furnace owner John Brien and grandson of another, Col. John McPherson). The young Brien had bought the operation from his late father’s estate in 1841, but he instantly encountered financial trouble and found himself in the position of having to sell the floundering operation. This occurred in April, 1843, a time of drastic change in the furnace industry based on the introduction of coke as a coal-based combustible agent over charcoal (created from bark and timber). Enter the “wanderer” from Chewsville, Peregrine Fitzhugh.  Hagerstown Torch Light (July 17, 1834) Hagerstown Torch Light (July 17, 1834) The Fitzhughs were connected through marriage to other “furnace-experienced” families of Maryland including the fore-mentioned McPhersons, and the Hughes. As for his own upbringing, Peregrine enjoyed the childhood that Washington County afforded. Family members were plentiful in the area. This was fitting because his grandfather had named his family plantation “the Hive,” because he saw it as the center of social, economic and familial life in its remote, rural setting. As for employment, Peregrine supposedly had some prior introduction and experience in the furnace and forge industry. I found an advertisement in an 1834 Hagerstown newspaper in which he was operating a general store. This operation offered groceries, wine and liquor. Peregrine Fitzhugh married Sarah Margaretta Pottinger (1816-1900) on September 24th, 1833. The couple welcomed their first child, a daughter, on September 6th, 1835 and named her Henrietta Maria. More daughters would follow: Mary Pottinger (b. 1837), and Sophia (b. 1840). The 1840 US census shows Peregrine Fitzhugh’s family living in Williamsford, known today as Williamsport.  All Saints' Cemetery in left center of lithograph in this view looking southeast from Square Corner (from 1854 Sachse lithograph) All Saints' Cemetery in left center of lithograph in this view looking southeast from Square Corner (from 1854 Sachse lithograph) Home and Hearth After purchasing the Catoctin Furnace in April, 1843, Peregrine took up residence at the Auburn mansion, formerly inhabited by distant ancestors and cousins, not to mention the stately home’s builder Baker Johnson, another brother of famous Thomas. As Peregrine dealt with the challenges associated with running a furnace operation, he would also be faced with familial triumphs and tragedies. A fourth daughter, Isabella Hudson, would be born in January, 1844. It’s interesting to note that this was nine months after the Fitzhughs took ownership of the furnace. This daughter was such a welcome addition and favorite of her father that her name would be used to grace a later built feature of the Catoctin operation. Another baby girl, Amelia, would follow, in 1845. Unfortunately, she would die shortly after on June 19th, 1845. While in the midst of mourning their infant daughter, the Fitzhugh’s oldest child, nine year-old Henrietta, would pass on July 9th. Just 20 days separated the deaths of these sisters. Both girls were laid to rest in the old burying ground of the All Saints Episcopal-Protestant Church congregation in Frederick City, located between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. Life at the furnace went on for the Fitzhughs. The family welcomed yet another little girl in 1846 and named for her mother, Sarah Margaretta. She would be given the nickname “Meta.” The next year, Peregrine received a financial boost when a wealthy great aunt died, leaving him a large chunk of money from her estate. This allowed Fitzhugh to make necessary improvements to his pig iron operation. He also took the opportunity to recruit some talented work associates with the mission of making the entity profitable again. This was exemplified by a man named Michael M. Ege. Another daughter, Emma Katherine (Kate), was born in 1848.  Stack #2, better known as "Isabella" Stack #2, better known as "Isabella" Hard Times Business success was short-lived, however, and a financial downfall would beset Peregrine Fitzhugh in the early 1850’s after the departure of Mr. Ege. Production was at a minimum, and little iron shipped out. The family would be forced to sell their spacious home of Auburn mansion, plus surrounding lands. With debts mounting, Peregrine borrowed heavily from relatives, namely his wife and mother. He would have to enter into a business partnership with Jacob M. Kunkel of Frederick. This occurred in 1856. Kunkel’s money allowed Fitzhugh to “right the ship” so to speak. Debts were paid and more improvements were made to the furnace. He installed a “mule powered” rail line to move ore from the banks to the furnace. He also built a second furnace stack next to the original. This steam-powered, hot-blast charcoal furnace was given the name Isabella, after Peregrine’s daughter. Peregrine was also a highly religious man and did his part to continue a close relationship between both his faith and furnace. He was a member of All Saints Parish in Frederick and was supportive of the previously built Harriet Chapel within the Catoctin Furnace hamlet. Fitzhugh deeded seven acres of land surrounding the small, stone chapel and went on to help build the Catoctin Parish Rectory. In 1854, a boy was born to Peregrine and Sarah Margaretta—William McPherson Fitzhugh. Another momentous thing happened within that year, Mount Olivet Cemetery opened in late May. Peregrine would invest money into the newly incorporated Mount Olivet Stock Company, buying five cemetery shares for a total outlay of $100. In return, these shares were surrendered for five burial plots in Area H. He would have his two deceased daughters removed from All Saints Cemetery and brought to the new non-denominational, “garden” cemetery for re-burial. Henrietta and Amelia would be re-interred into Mount Olivet on October 24th, 1854. While Jacob Kunkel now held the property mortgage, Peregrine continued the day-to-day management of the furnace, and his family lived in the Catoctin Manor house, also known as the Ironmaster’s home, located immediately north of the furnace operation. A few years went by and Peregrine worked diligently to pay off debts. Two more setbacks would hit the Fitzhughs in 1858. First off, Peregrine was severely burned by an explosion of gas at the furnace in January. Second, debtors brought suit against Fitzhugh and a local court actually appointed trustees culminating in a trustee’s sale. The furnace was bought by Jacob Kunkel’s father (John Kunkel) as an investment. After the sale of Catoctin Furnace, Peregrine left the area and headed west to find subsistence for his family. He went to Texas, and a few accounts say that he studied opportunities in the oil well business. Meanwhile, his name was constantly appearing in the newspapers back home, having lawsuits brought against him. This would continue in earnest over the next 3 years. Whatever the case may have been, Sarah Margaretta Fitzhugh and the children had been left behind at the Catoctin Furnace vicinity, still living within the Ironmaster’s House. Apparently, the records of the business were left in a drawer of Peregrine’s private desk. Mrs. Fitzhugh would soon be evicted when Jacob Kunkel’s brother (John Baker Kunkel) moved into the Ironmaster’s residence. From here Mrs. Fitzhugh migrated back to Auburn to live. Peregrine reappeared in spring of 1859, and immediately went about the process of relocating his family to the other side of the country. California Dreamin’ I guess you could say that their family wandered off. Thomas J. Scharf’s The History of Western Maryland (published in 1882) says this about the Fitzhugh family: Thomas J. Scharf’s The History of Maryland says this about the family: “This business catastrophe was promptly ascribed by the opposition papers to the effects of the Democratic tariff of 1846. Peregrine Fitzhugh left the county after the sale of his property in Washington and Frederick counties, including the Catoctin Furnace. In California there were a number of leading citizens including Major Richard P. Hammond, the surveyor of the Port of San Francisco during President Pierce’s administration, who had gone from Western Maryland and a few years after Mr. Fitzhugh left Catoctin Furnace he joined the Maryland Colony in California with his family consisting of his wife, a son and five daughters. Most articles say that the Fitzhughs actually left Maryland around 1862. Perhaps the American Civil War helped influence the family to vacate Maryland for the less chaotic environs of San Francisco. They likely sailed out of Baltimore to the West Coast. Once there, Peregrine found work as a land clerk, and later became a real estate mogul. He did very well for himself, as did his offspring. The California experience for beloved daughter Isabella Fitzhugh was short-lived, however. She would die in San Francisco not long after her marriage to Rev. Edward G. Perryman, at the age of 20. She had a child named Fitzhugh Perryman in 1863, who would be raised in part by his maternal grandparents. Isabella’s body would be shipped back to Frederick and Mount Olivet. She was placed next to her sisters Henrietta and Amelia, buried here a decade earlier.

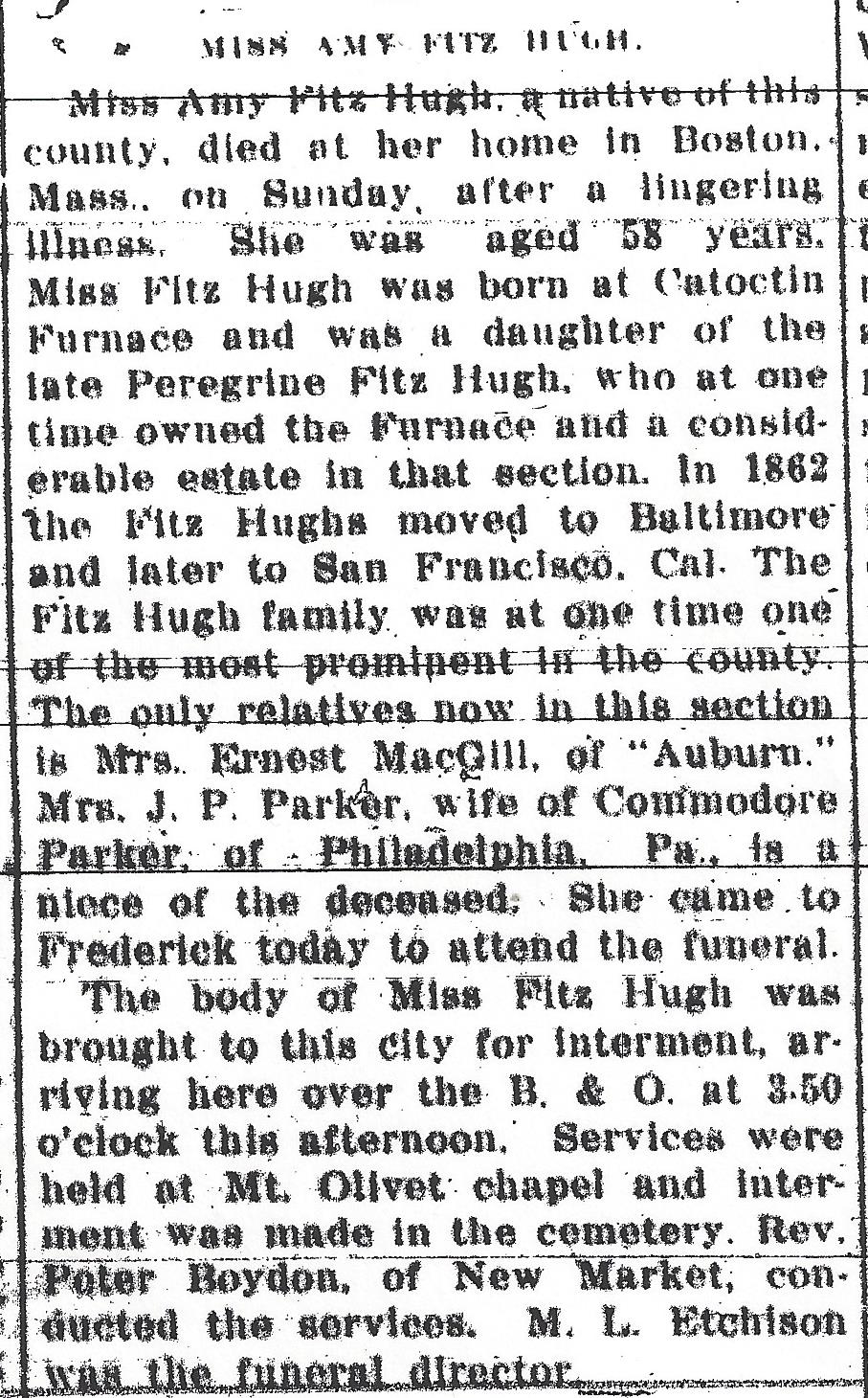

Amy’s body would be transported back to Frederick by train from Boston. Three of her sisters were waiting for her in Mount Olivet Cemetery in the old Fitzhugh family lot. I’m glad to know that these four “Spirits of the Furnace” could be reunited here in Mount Olivet.

5 Comments

shane shanholtz

10/25/2017 10:14:33 pm

Great article . I love reading your stuff

Reply

Russ Poole

10/26/2017 09:42:15 am

Great article Chris! Very informative!

Reply

Carol Newmann

10/27/2017 02:12:25 pm

Very much enjoyed your recent article. Informative and interesting.

Reply

3/12/2019 02:35:03 pm

Hello. Thank you for this wonderful account of the Fitzhugh family. One of their distant Fitzhugh relatives married Wilmer Dent Corse in Virginia and their grandson married my aunt, Carita Doggett Corse. She was a well-regarded Florida historian (profiled on Wikipedia). As an amateur genealogist, I am interested in those in my families who were players in 19th century mining. This is what brought me to this great story. Emma Catherine Fitzhugh Hammond is related. I have developed details on others who ended up in SF. Also, one of our families is the NH Smiths that include Hamilton Smith, Jr an historically significant player in mining and also involved in South Africa working for the Rothchilds. John Hays Hammond mentions him in his autobiography. Also, distantly related, are the Janin family who mining engineer, Henry Janin married Mary Belknap Smith, the daughter of above mentioned Hamilton Smith. She lived in SF and is buried here in Colma. All these people knew one another! Sorry for going on at length but I wanted to illustrate why your great article meant so much to me. Thanks again. - John L. Doggett

Reply

1/31/2022 07:28:16 pm

Hello, Peregrine Fitzhugh purchased over 5,300 acres of the Rancho La Puente, about 20 miles east of Los Angeles, from one of its grantees, William Workman, whose house and cemetery are part of the museum I manage in the City of Industry. Fitzhugh ran sheep there, but there was a legal dispute over the land and, in April 1872, a few years after the purchase, the property was sold to Edward F. Beale, well-known Indian agent and founder of Fort Tejon north of Los Angeles, and Robert S. Baker, a founder of Santa Monica. Our collection has a remarkable letter written in August 1870 from Los Angeles by Fitzhugh to Workman urging a settlement of the suit's costs.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed