|

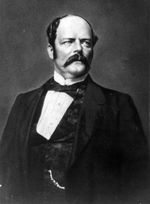

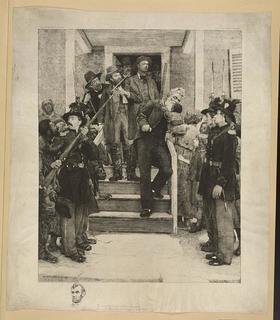

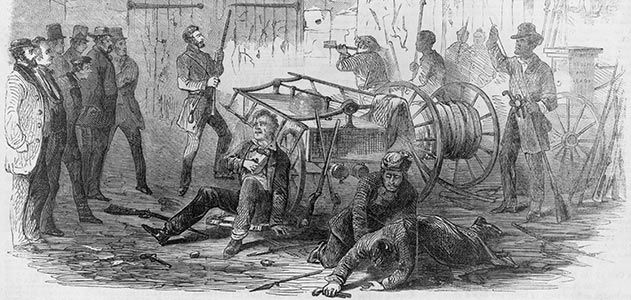

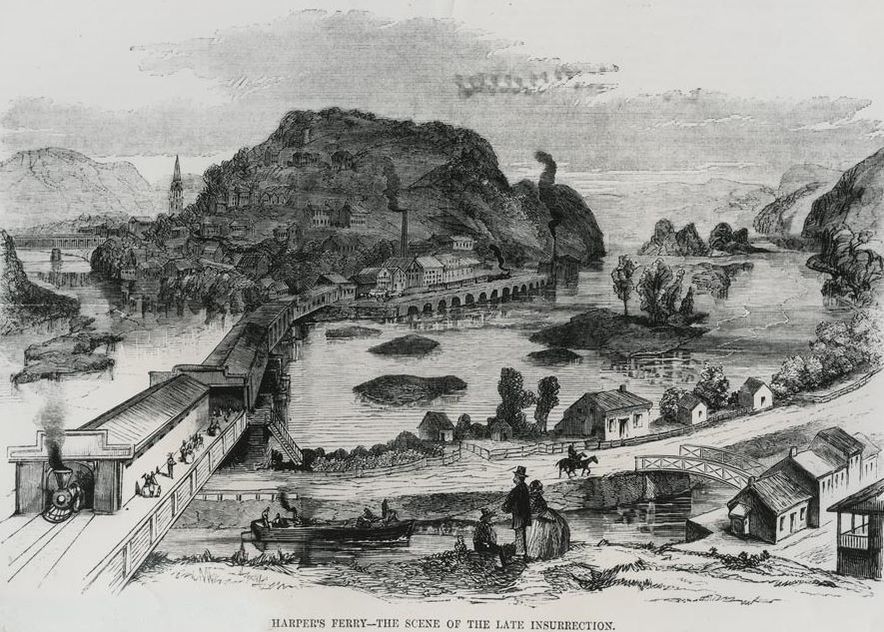

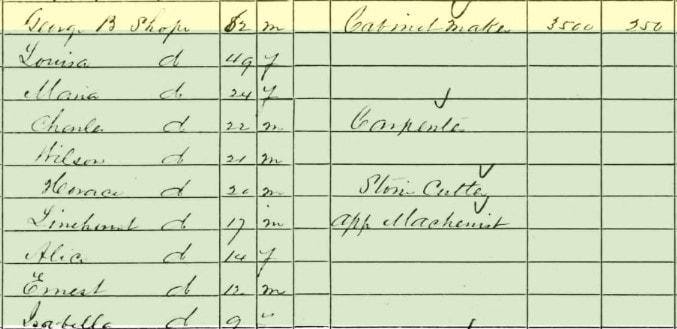

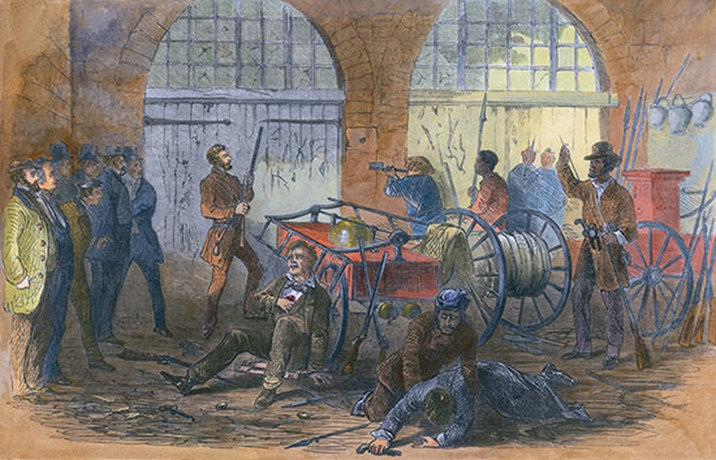

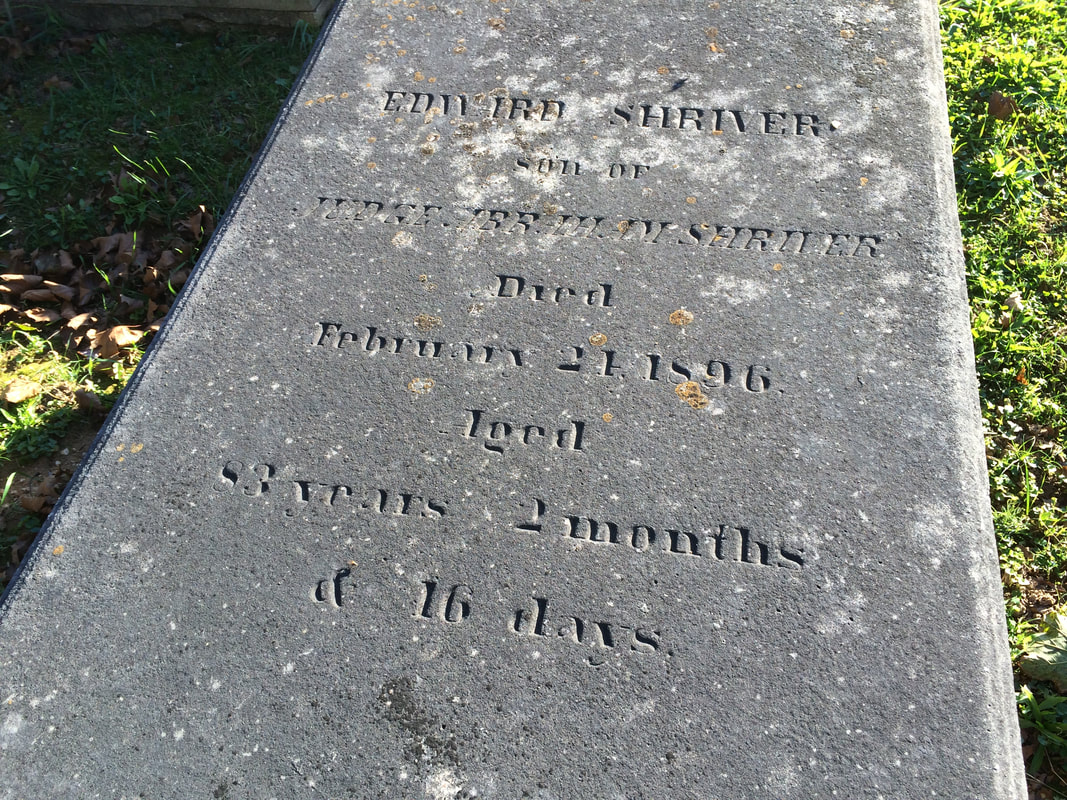

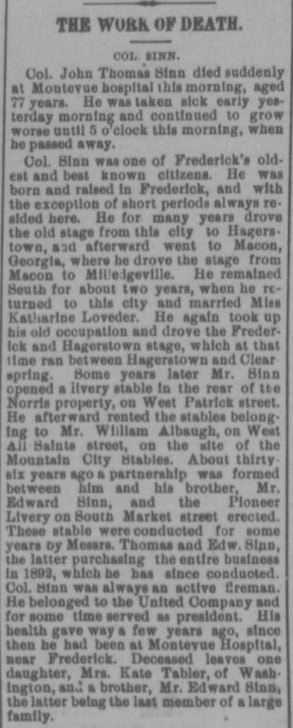

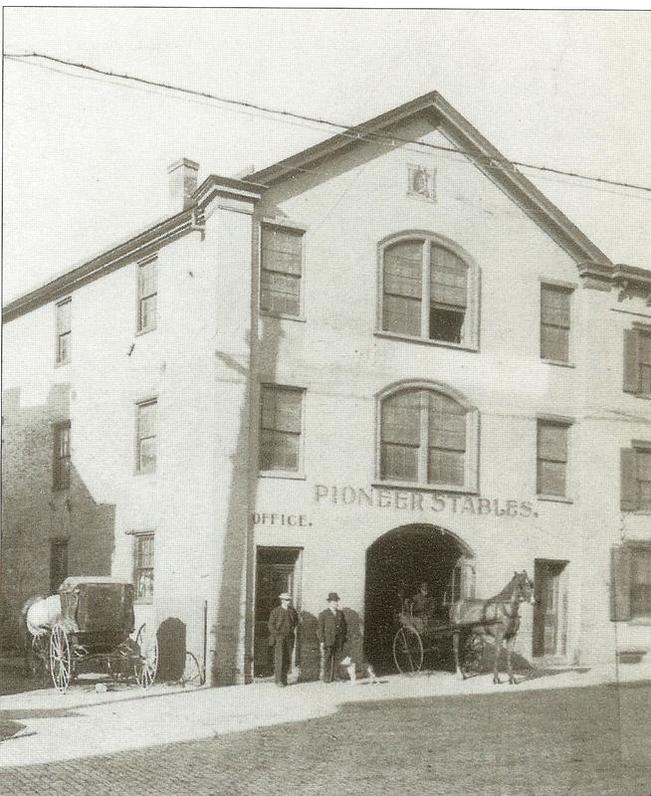

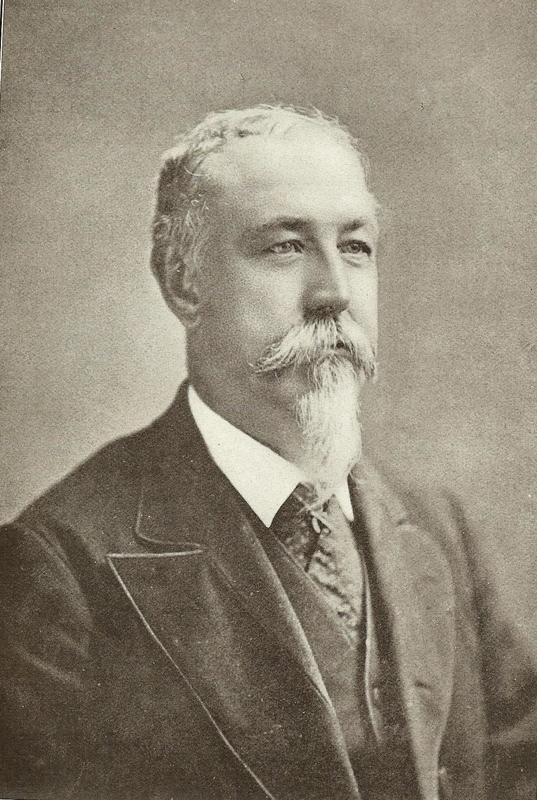

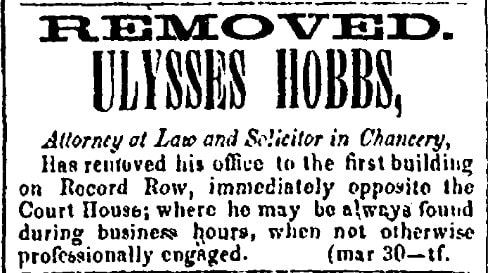

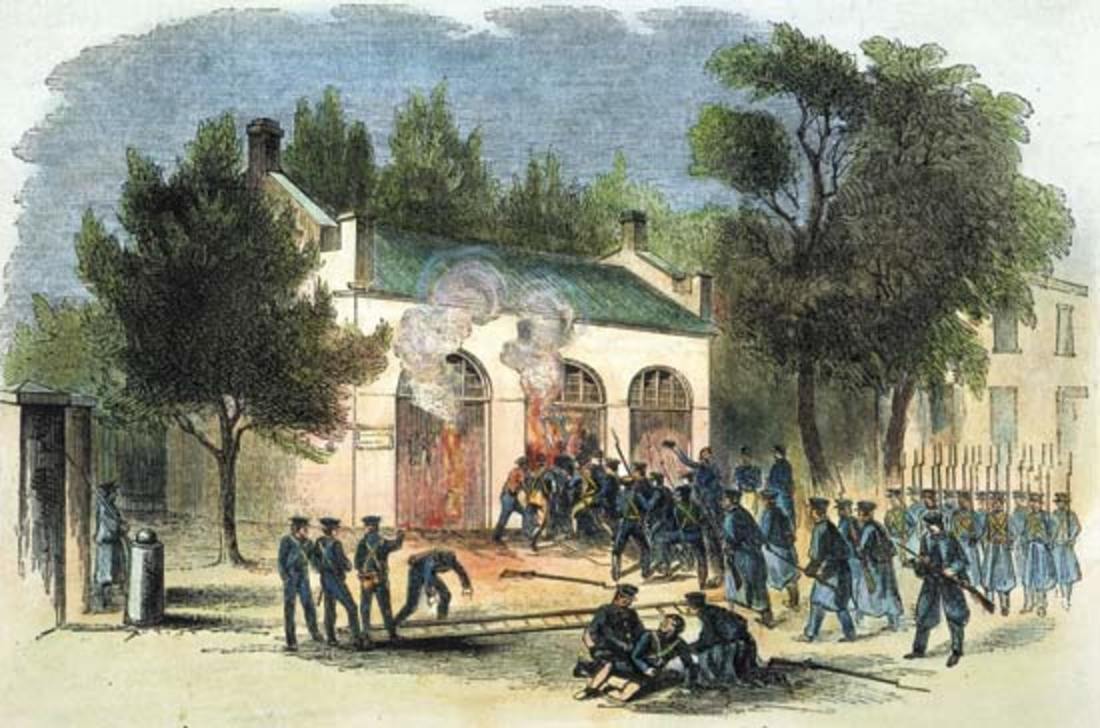

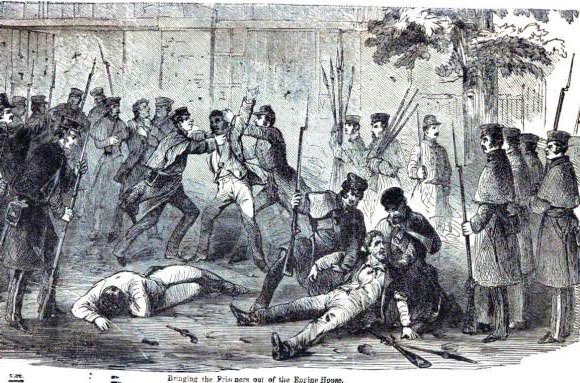

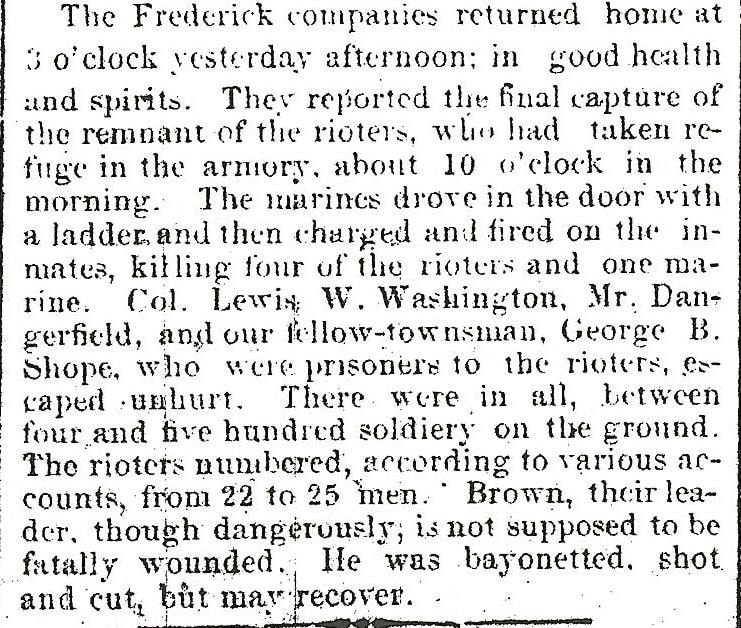

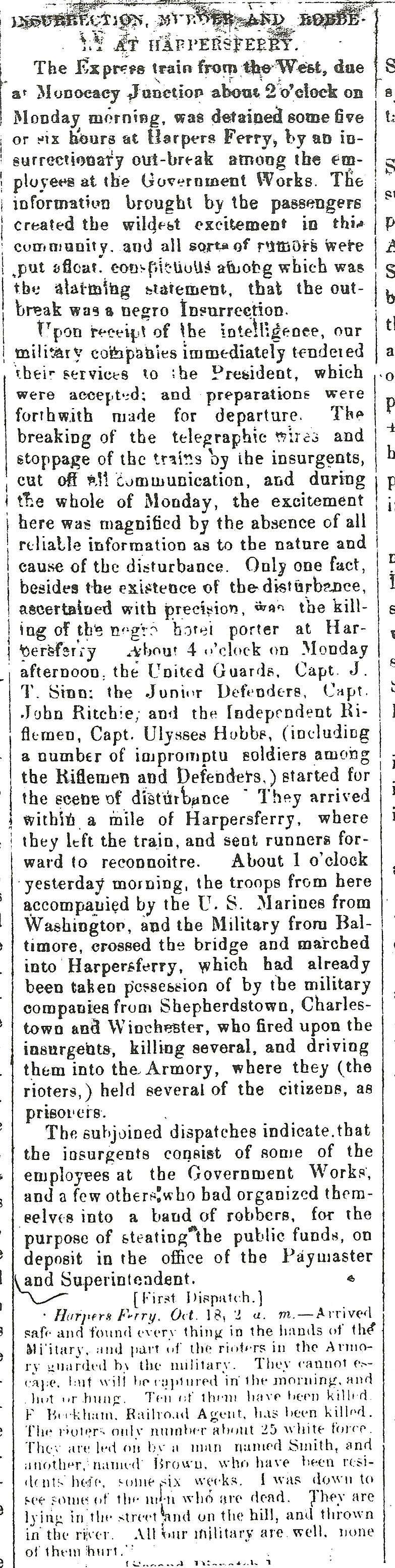

A lesser known gravesite in Mount Olivet (and its occupant) holds a definitive connection to one of the most famous events in US history. It was a long, frightening couple of days (and nights) for a Frederick man who found himself in the wrong place, at the wrong time—Harpers Ferry (VA) during the third week of October, 1859. On the night of Sunday, October 16th, 1859, a band of anti-slavery men under John Brown captured the US armory at Harpers Ferry. Earlier in the year, Brown had settled into the Kennedy Farmhouse, located just over South Mountain in Washington County’s Pleasant Valley. Here, he secretly trained his 18-man army in military tactics, and supplied them with pikes to be used as thrusting spears. John Brown’s goal was to seize weapons from the national armory at Harpers Ferry and arm slaves, who would then overthrow their masters. The raid quickly turned into a fiasco. Brown’s first victim at Harpers Ferry was a railroad night watchman, Hayward Shepherd—a free black man. Armory workers discovered Brown's men in control of the building on Monday morning, October 17th. Shortly after 7:00 am, a Harpers Ferry townsperson and armory employee, Thomas Boerly, was shot and killed near the corner of High and Shenandoah streets. During the day, two other citizens were killed, George W. Turner and Fontaine Beckham, Harpers Ferry’s mayor. When Brown realized he had no way to escape, he selected nine prisoners and moved them to the armory's small fire engine house, which later became known as John Brown's Fort. Infuriated—and mostly drunken—townspeople grabbed their rifles and trapped Brown’s men in the armory’s fire engine house. Shortly thereafter, local militia companies surrounded the armory, cutting off Brown's escape routes. One of the hostages inside was from Frederick. His name was George Brengle Shope.  Col. Lewis Washington Col. Lewis Washington The following excerpt is taken from THE OFFICIAL REPORT OF JOHN BROWN'S RAID UPON HARPER'S FERRY, VIRGINIA, OCTOBER 17-18, 1859. “About 11 a. m. the volunteer companies from Virginia began to arrive, and the Jefferson Guards and volunteers These companies, under the direction of Colonels R. W. Baylor and John T. Gibson, forced the insurgents to abandon their positions at the bridge and in the village, and to withdraw within the armory enclosure, where they fortified themselves in the fire-engine house, and carried ten of their prisoners for the purpose of insuring their safety and facilitating their escape, whom they termed hostages, and whose names are Colonel L. W. Washington, of Jefferson County, Virginia; Mr. J. H. Allstadt, of Jefferson County, Virginia; Mr. Israel Russell, Justice of the Peace, Harper's Ferry; Mr. John Donahue, clerk of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; Mr. Terence Byrne, of Maryland; Mr. George B. Shope, of Frederick, Maryland; Mr. Benjamin Mills, master armorer, Harper's Ferry arsenal; Mr. A. M. Ball, master machinist, Harper's Ferry arsenal; Mr. J. E. P. Dangerfield, paymaster's clerk, Harper's Ferry arsenal; Mr. J. Burd, armorer, Harper's Ferry arsenal.” The hostages were lined up against the back wall of the engine house. The most prominent of these individuals was Col. Lewis Washington, the great-grand-nephew of President George Washington. His great-grandfather was Charles Washington, George’s younger brother. Charles Washington took up residence in this vicinity in 1780, and founded Charles Town, established in 1787. In 1794, President Washington selected Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and Springfield, Massachusetts, as the sites of the new national armories. In choosing Harpers Ferry, he noted the benefit of great waterpower provided by both the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. Jefferson County was formed in 1801 as Charles Washington had anticipated, and the county court house stands on one of the lots he donated, as did the historic jail. In 1817, the federal government contracted with John H. Hall to manufacture his patented rifles at Harpers Ferry. That’s all well and good, but my interest, by George, is solely connected to another one of the luckless pedestrians kept hostage in the famed Harpers Ferry armory engine-house—George Brengle Shope.  Shope's 1812 soldier marker in Mount Olivet Shope's 1812 soldier marker in Mount Olivet George B. Shope George Brengle Shope was born on December 11th, 1796 to Jacob and Maria Elizabeth (Brengle) Shope/Schopp. He worked as a cabinet-maker by trade. Shope served as a private in the 1st Regiment of the Maryland Militia under Capt. John Brengle from August 25th to Sept. 29th, 1814. He would marry Elizabeth Dofler in February of 1818. The couple had two children (William Brengle Shope and George Dofler Shope) before Elizabeth’s untimely death in 1829 at the age of 27. George would soon-after marry a second time to Louisa Keller, and the couple went on to have eight additional children. Apparently, George considered, or made, a move to “Georgetown” in the District of Columbia as he was recorded as “having a sale of his personal property in late November, 1829.” Whether he followed through on the relocation at that time is not quite known, but records show he was back in Frederick by March, 1832 and serving as a Frederick City alderman. On July 4th, 1837, the Shope family did leave town for Ohio—but returned in 1838. The family appears in the 1850 US Census, living on N. Market Street, the site of George’s carpentry shop. The only other thing I could glean was that our future hostage was a member of Frederick’s Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Independent Fire Company. And now let’s get back to our insurrection and kidnapping in Harpers Ferry, already in progress.  Jacob Engelbrecht Jacob Engelbrecht Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) made poignant entries in his legendary diary the following morning: "Monday, October 17, 10 o'clock AM. — Harpers Ferry Riot — The Independent Bell & the United or Swamp Bell are both now ringing (Swamp first) calling together the military companies of our city." News of Brown’s Raid had reached Frederick before anywhere else, thanks to a train that Brown, himself, let pass out of Harpers Ferry. Frederick officials sent a telegram to President James Buchanan offering help. It was quickly accepted. The Frederick militia units, which doubled as the town’s fire companies, quickly grabbed their arms, ammunition and uniforms as they began the movement towards Harpers Ferry on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. All three were placed under the leadership of Col. Edward Shriver. Edward Shriver was born on December 8th, 1812, the second son of Judge Abraham and wife Ann Margaret Shriver. The colonel was a Frederick lawyer who in 1854 had provided the Agricultural Society of Frederick County with the land that has served home to the great Frederick Fair to this day. Col. Shriver quickly began assembling the three town companies of militia and went to Harpers Ferry by train to survey the chaotic scene for himself before bringing the larger militia contingent on the scene. Jacob Engelbrecht continued writing in his diary with another entry: "Monday October 17, ½ past 3 o'clock — Our three town companies, Captain Sinn, Captain Ritchie & Captain Hobbs just started for the cars at the Depot for the scene of War — Harpers Ferry." Interestingly, Col. Shriver and all three of his militia commanders are buried here at Mount Olivet. Here is a quick look at the group: Capt. Sinn Capt. John Thomas Sinn headed the United Home Guards (1817-1894). He was a stage coach driver earlier in life and operated livery stables in town including one named the Pioneer Stables located where LaPaz Restaurant sits today on the west side of S. Market St. at Carroll Creek. From spot accounts I have read, he was a beloved citizen but in his younger days seemed like a guy ready to pick fights with anyone who wanted a piece of him. Capt. Ritchie Capt. John Ritchie (1831-1887) had charge of the Junior Defenders. The Harvard graduate would have an illustrious career as a lawyer, rising to the position of Chief Judge of the Judicial Circuit and Court of Appeals of Maryland. He also would later serve as a representative in the US Congress. Ritchie grew up in a house that afforded a view of his future gravesite. Capt. Ritchie’s wife and daughter were featured prominently in two former stories written in September, 2017 about the founding of the Frederick Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Capt. Hobbs The Independent Rifleman were led by Capt. Ulysses Hobbs (1832-1911). Hobbs eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Maryland Militia. For years, he was one of the leading attorneys in Frederick County. Hobbs left for a while to practice in Howard County but returned to Frederick. He also served as a member of the Maryland Legislature. At the time of his death in 1911, Ulysses Hobbs was the oldest member of the Frederick Bar. He would die at the State Sanatorium in Sabillasville after a prolonged illness of several months. When Col. Shriver and the Frederick militia companies arrived at Harpers Ferry just after sunset, they experienced difficulty in getting across the Potomac River and into the town. The militiamen eventually came across the main railroad bridge into Harpers Ferry, where they were quickly put into position in an effort to help corner Brown’s surviving men holed up in his makeshift “fort,” the Armory’s guard and fire engine house. Ultimately they would surround John Brown, remaining until the US Marines under Col. Robert E. Lee would relieve them the next morning. Despite being fired on repeatedly by the raiders holed up in the engine house, Shriver’s men sustained no injuries during their night of guard duty. From their first arrival at the armory, his soldiers had “unanimously and warmly” favored storming the engine house, but Colonel Baylor from a Virginia militia outfit objected because the raiders had with them several prominent local citizens as hostages. A night assault would pose too great a risk, Baylor argued, so the Frederick troops settled in to their guard duties. Shortly before midnight (on Monday, October 17th), Capt. Sinn, while on guard in front of the engine house with some of his men, was hailed by one of the outlaws and asked to approach the building “for the purpose of conference in regard to the terms on which the Insurgents proposed to surrender.” Sinn spoke with a person who identified himself as “Captain Brown.” This of course was John Brown. Brown complained to Capt. Sinn that his men had been shot down like dogs in the street while carrying flags of truce. Sinn indignantly replied that men who take up arms in such a way must expect to be shot down like dogs. Brown replied that “he knew what he had to undergo before he came there, he had weighed the responsibility and should not shrink from it.” Brown said his terms deserved consideration for he had treated his captives well, refrained from massacring citizens when he had the power to do so, and that his men did not shoot any unarmed citizens. Captain Sinn informed Brown that Mayor Beckham was unarmed when killed. For this, Brown expressed deep regret. Brown mentioned the mortal wounds of his two sons and said that if he, his men, and their hostages were escorted to the Maryland shore, he would release the hostages unharmed and “the Insurgents would take their chance for their lives in an open fight.” Sinn relayed Brown’s proposal to Col. Shriver, who promptly went to the engine house where he personally “held a parly with Captain Brown and the gentlemen whom he held as prisoners.” John Brown repeated his offer to Col. Shriver, with one additional condition. He asked that after releasing the hostages he and his men should not be shot instantly, but rather be “allowed a brief period for preparing for fight.” Shriver told Brown that he was surrounded by an overwhelming force, and that his life was already “assuredly forfeited.” The Maryland colonel urged Brown to release the “innocent unoffending gentlemen” he was holding as hostages, but Brown retorted that “he had secured them as hostages for his own safety and the safety of his men and he should use them accordingly.” Shriver concluded there were no further grounds for discussion, and terminated the conference with Brown. The Maryland and Virginia field commanders met and decided to storm the engine house at dawn, using bayonets instead of gunfire to “secure as far as possible the safety of the prisoners.” On the morning of October 18th, Col. Lee and the US Marines sent from Washington, DC arrived at Harpers Ferry. Brown and his surviving eight men were quickly overwhelmed by the marines. In Shriver’s words, “in a very short time, all were killed, badly wounded or made prisoners.” Col. Shriver noted that the surgeons of each of the three Frederick militia companies were “at hand to render any service which might be required,” commending especially Dr. William Tyler, Jr., of Captain Ritchie’s Company, who “obtained a position inside of the yard, followed the Marines to the charge and was the first to receive and attend to the Marine who was mortally wounded.” US Marine Israel Greene is credited with being the leader of the group that captured Brown. Greene said afterwards of the captives that the eleven prisoners “were the sorriest lot of people I ever saw. They had been without food for over 60 hours, in constant dread of being shot, and were huddled up in the corner where lay the body of Brown’s son and one or two others of the insurgents who had been killed,” said Green. After the engine house was secured, effectively ending John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the Frederick militia were kept on guard duty inside the armory compound for a short time and then dismissed. During the early morning hours, Robert E. Lee supposedly had offered the honor of leading the attack to Colonel Shriver and the Frederick Militia. Shriver refused noting his men had families at home. He told Lee: “I will not expose them to such risks. You men are paid for doing this kind of work.” The Frederick militia returned to Frederick that afternoon, Tuesday, October 18th. Col. Shriver concluded his official written report by commending the “soldierly bearing, discipline, and readiness to discharge every duty assigned, displayed by each officer and private of the companies which formed the Battalion under my command.”  A wounded John Brown was taken to the Jefferson County jail and courthouse in Charles Town for trial. Documents also indicate the United Guard, and in particular Captain John Thomas Sinn, guarded John Brown and his men. In fact, Captain Sinn developed such a close relationship with John Brown that he was later asked to testify as a character witness for Brown at his trial in Charlestown. George B. Shope also gave testimony at the legendary trial which began on October 26th. Five days later, a jury found John Brown guilty of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. He would be hanged a short distance away on December 2nd, six weeks after the ill-fated attack on Harpers Ferry. I never found out why George B. Shope was in Harpers Ferry, or how exactly he got captured. The book The Strange Story of Harpers Ferry written by Joseph Barry in 1903 simply says this: “Of Mr. Schoppe (sp) little is known at Harpers Ferry. As before stated, he was a resident of Frederick City, Maryland, and his accidental presence at the scene of disturbance on the memorable 17th of October.” Elsewhere in the book, the author states that the Frederick resident happened to be on a business visit to Harpers Ferry at the time. In 1861, George B. Shope would join the newly-formed, Brengle Home Guards of Frederick City. On March 19th, 1866, he would be elected a Commissioner of Tax for Frederick City. George B. Shope died at his residence on E. Patrick St. on June 6th, 1871, at the age of 74. He would be laid to rest in the cemetery’s Area H/Lot 324. Below is the story of the John Brown Harpers Ferry Raid as it was reported in the Frederick Examiner newspaper on October 19th, 1859.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed