|

Veterans Day weekend and thousands of flags are gently blowing in the breeze here in Mount Olivet Cemetery. These were placed on the graves of former military personnel last Saturday November 5th by hundreds of volunteers, both young and old. The Veterans Day holiday, itself, is recognized on November 11th each year, symbolic as the date when World War I officially ended in 1918. For over a century, November 11th has been a national holiday in France, and was declared a national holiday in many Allied nations. However, many Western countries and associated nations have since changed the name of the holiday from Armistice Day, with member states of the Commonwealth of Nations adopting Remembrance Day, and the United States government opting for Veterans Day. At the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, the Great War ended. At 5 am. that morning, Germany, lacking manpower and supplies and faced with imminent invasion, signed an armistice agreement with the Allies in a railroad car outside Compiégne, France. World War I left nine million soldiers dead and 21 million wounded, with Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, France and Great Britain each losing nearly a million or more lives. In addition, at least five million civilians died from disease, starvation, or exposure. Twelve Frederick boys, buried in Mount Olivet, died while engaged in active duty. I’ve written previous stories about each of these individuals. 600 other veterans, including four known women, joined their comrades here when their lives on earth came to fruition.

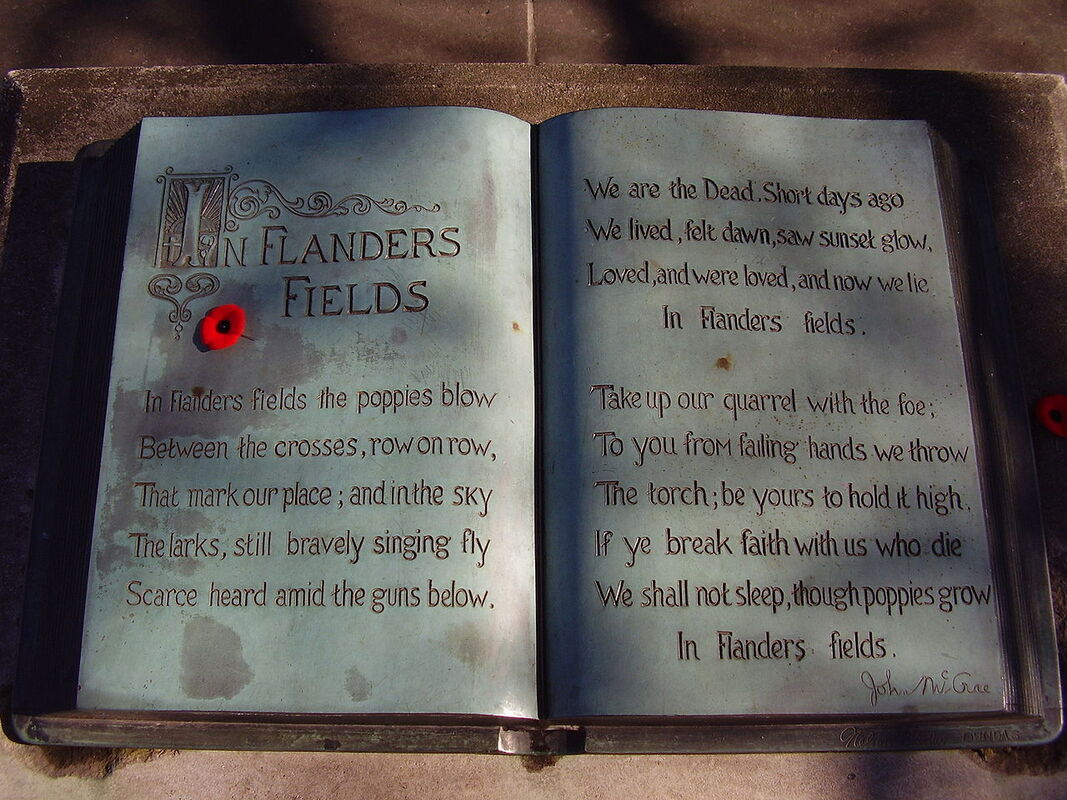

As part of the ceremony, we acknowledged 11 knockout roses which were planted on the perimeter of the gazebo as part of a Never Forget Garden. This idea “germinated” from Arlington Cemetery through an initiative started in 2018. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Never Forget Garden is a nationwide invitation to all Americans and freedom loving people to plant gardens as a visual way to represent America’s unwavering commitment to our sacred duty to recognize, remember, and honor our veterans, many who continued to serve as first responders, and their families now and for many years to come. There are many ways and traditions that are available to express patriotism, love, mourning and remembrance. The Never Forget Garden Marker, designed in collaboration with the artists at Carruth Studio, was inspired by the sacred duty of the American people to never, ever forget or forsake all those who have served and sacrificed on behalf of America in times of war or armed conflict. Its message beckons the visitor "to pause in this special place, and with a quiet soul open your heart to allow these plantings to speak; to reflect upon the deeds of those who we owe a debt that can never be fully repaid; and to think about those immutable truths that define us as Americans secured by their full measure of devotion." Occasioned by the Centennial of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a Never Forget Garden and this marker are intended to be a place to remember, to honor, and to teach. It is a place of remembrance and renewal of our commitment to the living, the dead, and those yet to serve our Country. We originally scheduled our dedication event for October 1st but it was postponed to month’s end due to rain, the remnants of Hurricane Ian which did a number on western Florida. On our second try, we had perfect weather, and an equally nice ceremony to go with it. The late October event featured a few highly talented speakers. One of which was Richard Azzaro, a former guard of the Tomb of the Unknown soldier from March 1963-April 1965. Mr. Azzaro is co-founder of the Society of the Honor Guard, Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and served as the organization’s inaugural Vice President and later as President. He is the current director of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Never Forget Garden Committee. He was joined by Chaplain Charles J. Shacochis, Jr., who also served as part of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier honor guard from February 1965 until February 1967.  tri-color cockade tri-color cockade These gentlemen explained that the recent Centennial of World War I was not only a celebration to remember the burial of the World War I Unknown Soldier, but an opportunity to reflect on what the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier means to America. The legislation that created the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, written by Congressman Hamilton Fish, viewed the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier as a focal point to bring all Americans together—that its meaning be not limited to the Great War and the exclusive claim of that War’s veterans. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington is an American symbol of remembrance that has a connection to an organization to Le Souvenir Francais. In 1887 this organization began in northern France in an area known as Alsace-Lorraine that was claimed by Prussia after the War of 1870. To remember French soldiers who had died fighting Prussian (German) soldiers, young French girls placed flowers and tri-color cockades of the French flag on the tombstones of these departed warriors despite the orders of Prussian officials who occupied Alsace-Lorraine not to decorate the graves. A professor from the area, Xavier Niessen organized the Le Souvenir Francais to honor these dead soldiers. As word spread throughout France, a swell of patriotism grew. On March 7, 1887 Professor Niessen petitioned the French government to join Le Souvenir Francais and they did. Up until 1914 and the start of Great War, Le Souvenir Francais created monuments and participated in ceremonies across France honoring war dead. In 1914 the organization began affixing tricolor cockades on tombstones of France’s dead near hospitals and cemeteries. Following the end of World War I, Le Souvenir Francais was unable to access the graves of the dead still on French battlefields. The government was concerned about the spread of disease, unexploded ordnance and other hazards. Around the 1st of November, All Saints Day, ceremonies were organized away from the battlefields to place flowers on graves and help bereaved families. It was during one of these ceremonies that Francis Simon asked the French government to transfer the body of an Unknown French Soldier from the battlefield to Paris. The commanding general of American forces in France, Brigadier General William D. Connor, learned of the French project while it was still in the planning stage. Favorably impressed, he proposed a similar American project to the Army Chief of Staff, General Peyton C. March, on October 29, 1919. Gen. March ultimately did not approve Gen. Connor's proposal. Mrs. M. M. Melony, editor of the Delineator, made a similar suggestion to Gen. March. In his reply Gen. March explained to Mrs. Melony that while the French and English had many unknown dead, it appeared possible that the Army Graves Registration Service eventually would identify all American dead. Furthermore, the United States had no burial place for a fallen hero similar to Westminster Abbey or the Arc de Triumphe. In any case, March pointed out, the matter was one for Congress to decide. On December 21st, 1920, Congressman Hamilton Fish, III of New York introduced a resolution calling for the return to the United States of an unknown American member of the overseas Expeditionary Force killed in combat in France and his burial with appropriate ceremonies in a tomb to be constructed at the recently built Memorial Amphitheater in Arlington National Cemetery. The measure was approved on March 4th, 1921 as Public Resolution 67 of the 66th Congress. Fish had originally intended for the ceremony to take place on Memorial Day 1921 but it was too late for that date. Then on October 20, 1921, Congress declared November 11th, 1921 a legal holiday to honor all those who participated in World War I; an elaborate ceremony in Washington would pay tribute to the symbolic unknown soldier. On September 9th, 1921 the Quartermaster General received orders from the War Department to select an unknown soldier from those buried in France. Following the selection ceremony, he was to deliver the body to Le Havre, where the Navy would receive it for transportation to the United States. The necessary arrangements were completed by the Quartermaster Corps in France in cooperation with French and U.S. Navy authorities. According to plans, the selection ceremony was to take place at Chalons-sur-Marne, ninety miles east of Paris, on October 24th, 1921. The honor of making the selection went to Sergeant Edward F. Younger, a decorated World War I veteran sent from his posting in Germany to support the selection ceremony. To indicate his choice of the Unknown Soldier, Younger placed a spray of white roses upon one of four caskets that contained the remains of unidentified American service members. These roses held deep meaning. They were donated by Brasseur Brulfer, a former member of the Châlons City Council who lost two sons in the war, including one whose remains were never identified—just like the American Unknown being honored that day. Grown in the earth of France, these roses formed a tangible connection between the American Unknown, the unknown dead of France and the French nation itself.  Thousands — including President Harding — gather for the burial of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery on Nov. 11, 1921. (Library of Congress) Thousands — including President Harding — gather for the burial of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery on Nov. 11, 1921. (Library of Congress) After the selection ceremony, the roses were placed on top of the flag-draped casket of the newly designated Unknown Soldier. Various sources, images and motion picture footage indicate that the roses from the selection travelled with the Unknown through many stages of his journey back to the United States, and may have been buried with him inside the Tomb. In the years after 1921, the white rose came to symbolize the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. To this day, it is frequently used in commemorations related to the Tomb, such as a recent ceremony at Sgt. Younger’s grave on October 24th, 1921, to mark the 100th anniversary of the selection. Mr. Azzaro wrapped up his comments by placing a bouquet of white roses on our Never Forget Garden marker. Additional remarks were given by Corey Campion, Associate Professor of History and Global Studies Program Director, Master's in Humanities and Chair, Dept. of History. Corey has conducted much research on World War I, which has culminated in him co-authoring a book with teaching colleague Trevor Dodman (also of Hood College), creating a curriculum to instruct educators and leading a tour a few years back to the former battlefields of France. Corey spoke to the importance of remembering not only the war dead, but also the veterans of any and all military conflicts. He referenced the Victory monument in Frederick’s Memorial Park, site of the annual Veterans Day program, along with other such sites in the county such as the Doughboy Memorial in Emmitsburg, Middletown's Memorial Hall and the William Bunke Memorial in Libertytown’s St. Peter’s Catholic Cemetery. Now our Mount Olivet World War I Memorial Gazebo joins that esteemed collection. Professor Campion took the opportunity to continue on the theme of flowers representing life, yet connecting to battlefield sacrifice as our earlier speakers had explained the importance of white roses in Mount Olivet’s Never Forget Garden. He spoke on the symbolism behind the red poppy flower and read the epic poem “In Flanders Fields.” The opening lines of this work refer to poppies growing among the graves of war victims in a region of Belgium. The poem is written from the point of view of the fallen soldiers and in its last verse, the soldiers call on the living to continue the conflict. The poem was written by Canadian physician John McCrae on May 3rd, 1915 after witnessing the death of his friend and fellow soldier the day before. The poem was first published on December 8th, 1915 in the London-based magazine Punch.

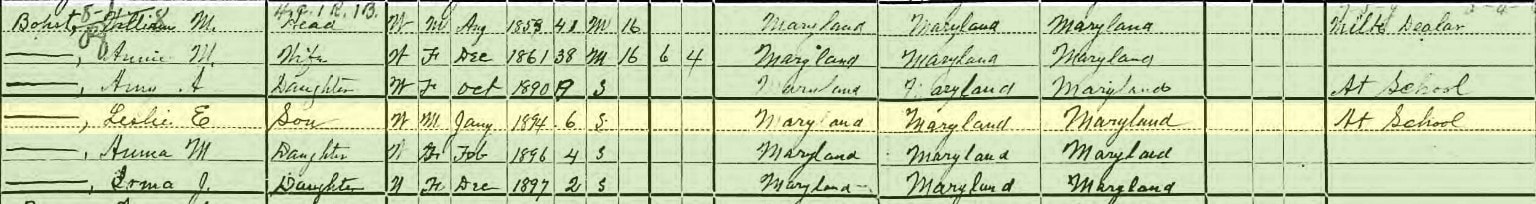

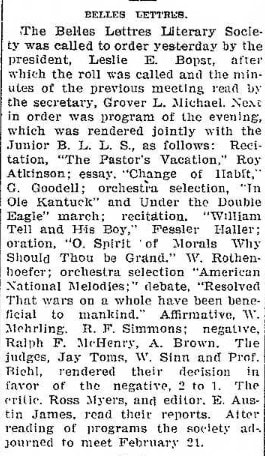

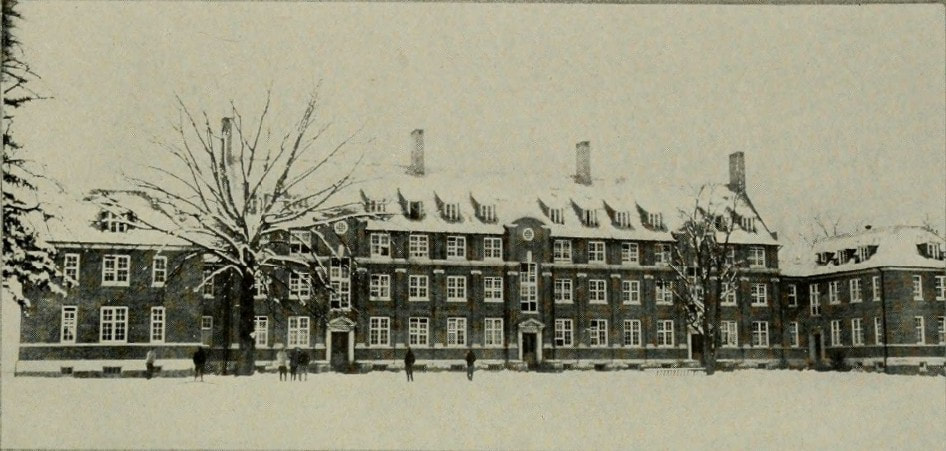

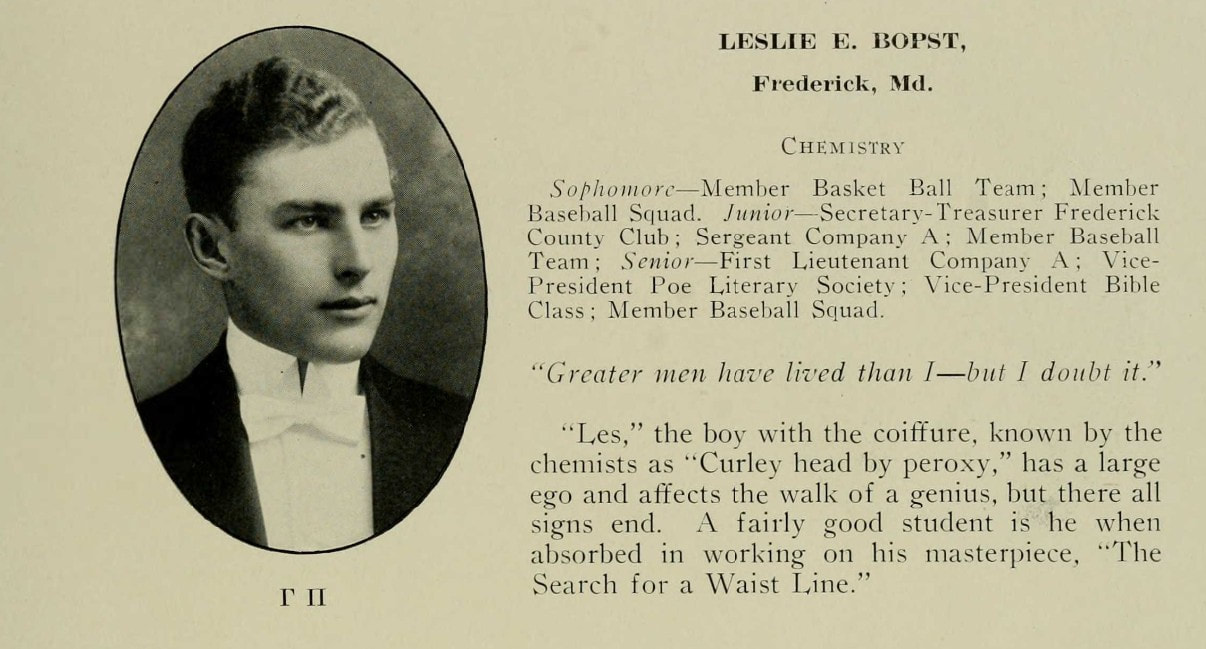

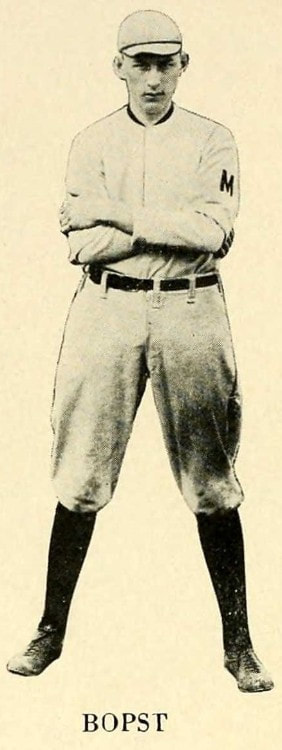

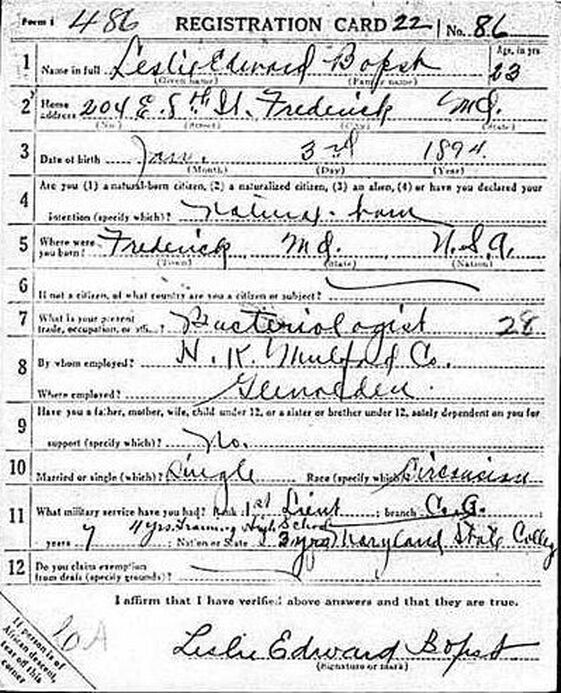

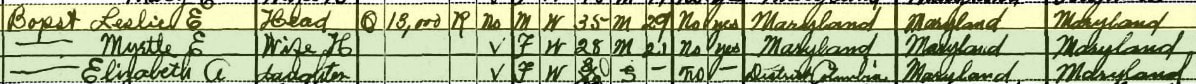

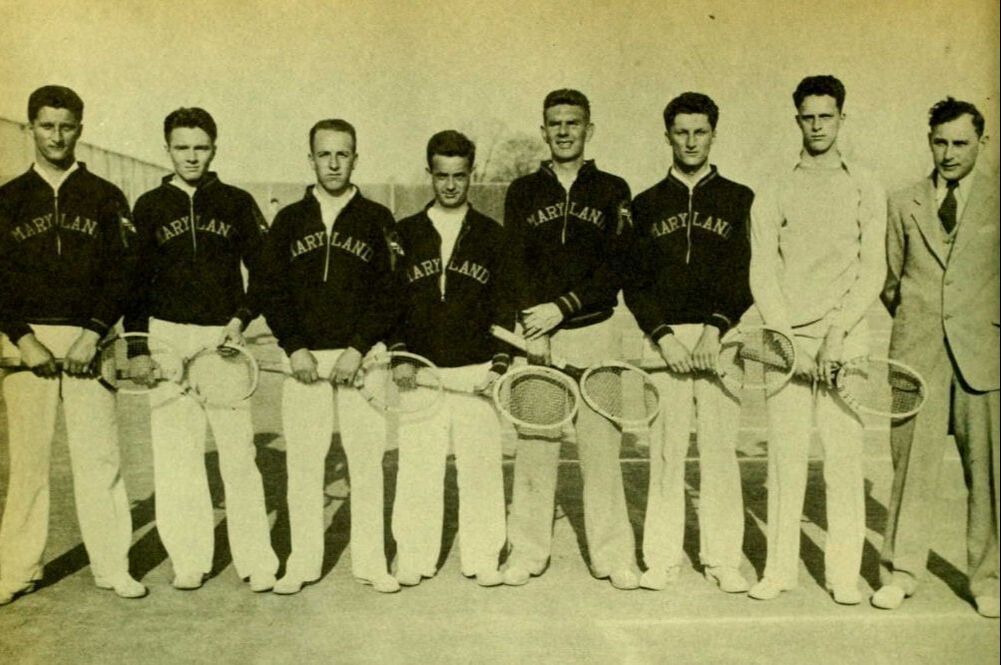

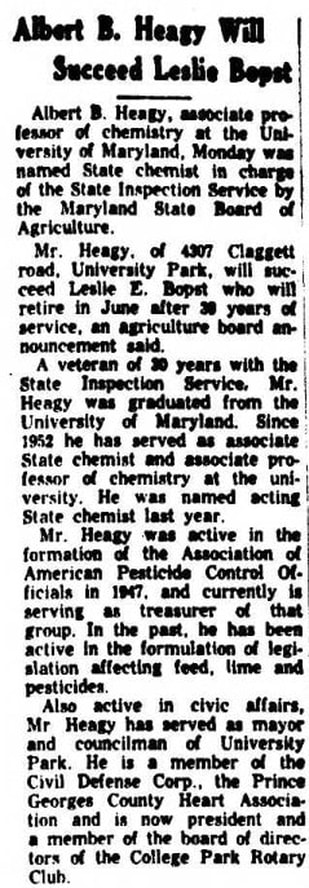

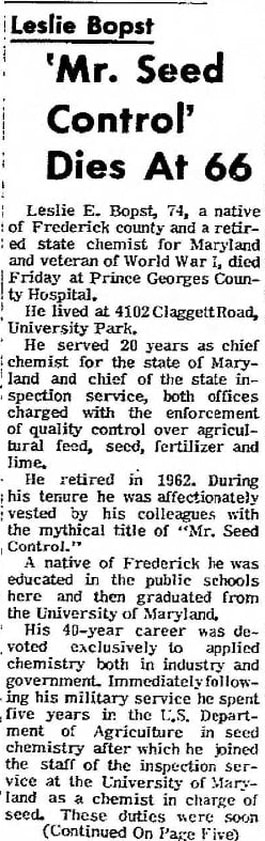

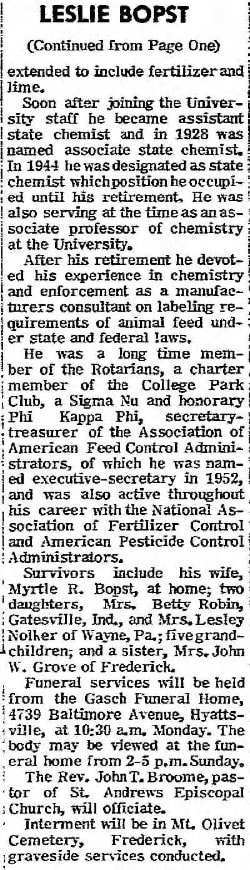

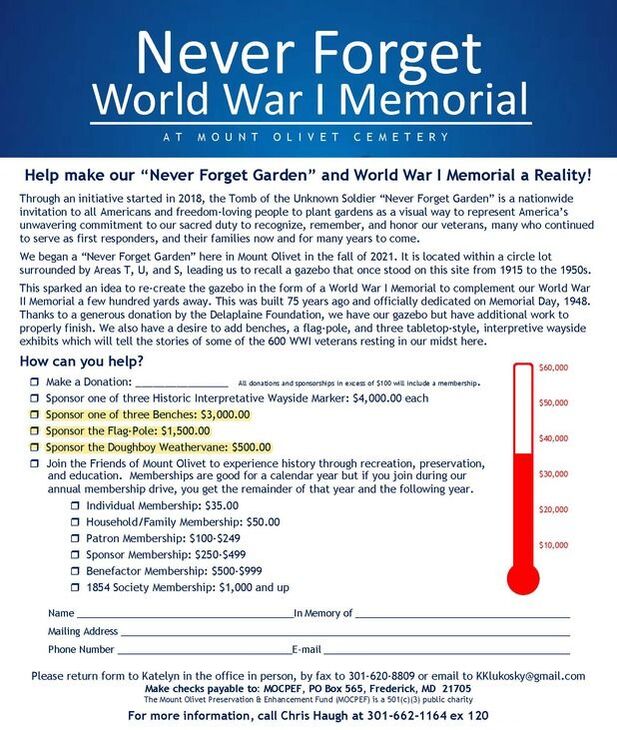

Moina Michael, who had taken leave from her professorship at the University of Georgia to be a volunteer worker for the American YMCA Overseas War Secretaries Organization, was inspired by the poem. She published a poem of her own called "We Shall Keep the Faith" in 1918. In tribute to McCrae's poem, she vowed to always wear a red poppy as a symbol of remembrance for those who fought in and assisted with the war. At a November 1918 YMCA Overseas War Secretaries' conference, she appeared with a silk poppy pinned to her coat and distributed twenty-five more poppies to attendees. She then campaigned to have the poppy adopted as a national symbol of remembrance. At the conclusion of our Mount Olivet Gazebo ceremony, we invited participants and onlookers in helping us spread red poppy seeds around the gazebo to further enhance our Never Forget Garden. We may not have poppies springing up in all other areas in our cemetery, but the flags (I referenced at the beginning) in a way represent the beautiful red flowers of Flanders Fields and battlefields everywhere our ancestors toiled. Thank you again to the volunteers who help us place these in advance of both Veterans Day and Memorial Day as its a big project. In five weeks on Wreaths Across America Day, these gravesites will also be covered with wreaths of evergreen symbolizing HONOR, RESPECT, and VICTORY. While on the subject of flowers, I can’t help but think of seeds and seasons. Of course, I could wax poetic for hours about the symbolism of both flowers and seasons and their relationship to life and death. One of the greatest principles in life is the concept of sowing seeds. This teaches us that if we give something, we can receive something in return. If we plant something in the proper conditions, water, feed and grow it, we can reap something bigger and greater. On Veterans Day, we honor all current and former members of the Armed Services. Our country's greatness is built on the foundation of your courage and sacrifice. Veterans Day calls out the sacrifices made by all service members in their decision to protect our freedoms by pledging their time, efforts, energies and expertise in addition to their lives. Mr. Seed Control With the flow of this story, it is obvious to me that at least one Mount Olivet veteran, in particular, needs to be recognized this Veterans Day weekend. He was a Frederick native and veteran of World War I, but of greater intrigue, his nickname was “Mr. Seed Control.” His name was Leslie Edward Bopst, a peculiar name, to go along with an even more peculiar nickname. There are 49 people with the Bopst moniker resting here in Mount Olivet, and I’m told the name is pronounced with a long O sounding similar to boast, but with a “p” sandwiched in the middle of that one-syllable word. Born January 3rd, 1894 to William Mortimer Bopst and Anna Mary (Brunner), Leslie spent his childhood at 8 East 8th Street on the outskirts of downtown Frederick in the early 20th century. His father started the Excelsior Dairy and ran the operation until 1920 at which time he sold it to Charles F. Rothenhoefer. Leslie had three sisters and was educated in local schools. He was a 1913 graduate of nearby Frederick Boys’ High School under the watchful eye of Professor Amon Burgee. Bopst busied himself with athletics and served as president of the Belles Lettres Literary Society. Fittingly, he also had charge of his high school’s floral committee. Leslie Bopst would go on to further his education at the Maryland Agricultural College, later to be known as the University of Maryland. He would graduate in 1916. While in school, Leslie, or Les as he was more commonly called, partook in athletics for the M. A. C. The Reveille yearbook of 1916 includes a picture of him as a senior, and another as a member of the college’s baseball team. The yearbook also makes mention of him having the rank of 1st Lt. in Company A. I believe this to be the college's Company A of an ROTC program as opposed to Frederick’s unit in the Maryland National Guard, which had its home at the former armory building standing on the southwest corner of N. Bentz and W. 2nd streets across from Memorial Park. Les would formally enlist in the US Army on September 27th, 1917. At this time, he found himself as a private in the 154th Depot Brigade. Twelve days later he was transferred to Company I of the 313th Infantry Regiment. Bopst would receive a promotion to the rank of corporal five weeks later. The following year, Les would be transferred on April 12th to a unique new wing of the United States Army. This was the Battalion Research Division of Chemical Warfare Service. The Great War was the first to utilize deadly and debilitating gasses thus necessitating such a division. Bopst would not be sent overseas to France, but would be based in Washington, DC. He would attain the rank of corporal for this entity one week before the end of the war, and would be honorably discharged one month later on December 10th, 1918. After completing his military service, Les embarked on a five-year career with the Department of Agriculture in seed chemistry. I found Les Bopst in the 1920 census living in an apartment building located on P Street in the nations capital. In this record, his occupation was listed as chemist, and his place of employment was labeled “private concern.” By 1922, his workplace would be the Maryland Agricultural College at today’s College Park. He joined the staff of inspection service at his alma mater as a chemist in charge of seeds with fertilizer and lime to fall under his purview shortly thereafter. On September 19th, 1923, our subject was a resident of Bethesda (MD) and married a fellow Bethesdan by the name of Myrtle R. Rabbitt. They would raise two daughters into adulthood. In 1928, Les would be named associate state chemist after spending a number of years as assistant state chemist. While a faculty member at the college, he naturally taught chemistry. I also learned that he was an advisor to Sigma Nu fraternity, and also coached the college’s tennis team. In 1944, Les Bopst was named state chemist, a position he would hold until his retirement 18 years later in 1962. His career at the college spanned 40 years. Bopst spent his remaining years as a corporate consultant, and remained active with Rotary and the College Park Club of which he was a charter member. He and Myrtle lived in the College Park-Hyattsville area and doted on the seeds of their personal life, two daughters and five grandchildren. Leslie E. Bopst died on December 20th, 1968. He would be buried in Area L/Lot 160, located behind our Key Memorial Chapel, along the drive that leads west to Confederate Row. Wife Myrtle would join him here in late May of 1990. Our last phase of the World War I Memorial Gazebo includes necessary fundraising for the addition of three, tabletop-style interpretive exhibits to be placed around the structure. These will tell the stories of the Never Forget Garden and Memorial Gazebo, along with highlighting the lives of some of the WW I veterans buried here, including individuals killed on the battlefield and others who fell victim to the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918. Please help us if you can.

2 Comments

Joanie Freeze

11/12/2022 08:00:03 am

I so enjoyed your article about WWI. My father, Edgar Merriman Freeze was in WWI. It’s nice to have these soldiers remembered. He and a group of friends, all from Thurmont, joined at the same time.

Reply

NANCY M DRONEBURG

11/14/2022 07:38:54 pm

What a enjoyable article this time about the unknown and the gazebo. Keep the stories coming.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed