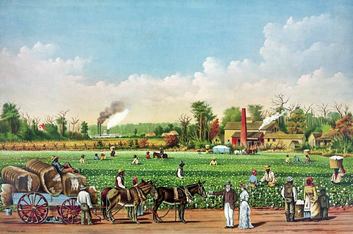

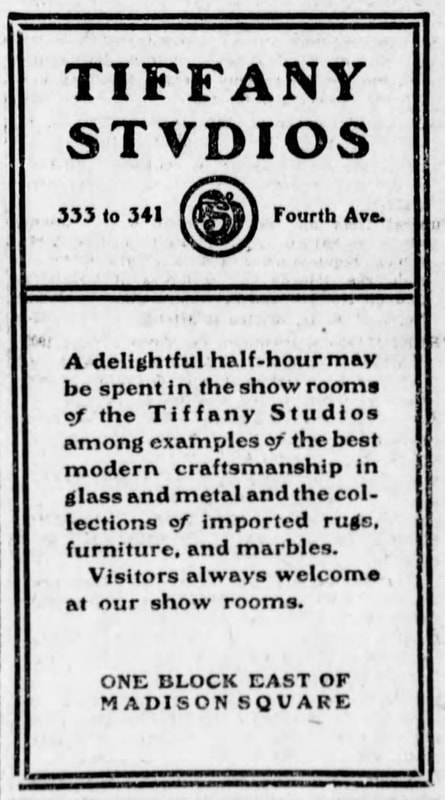

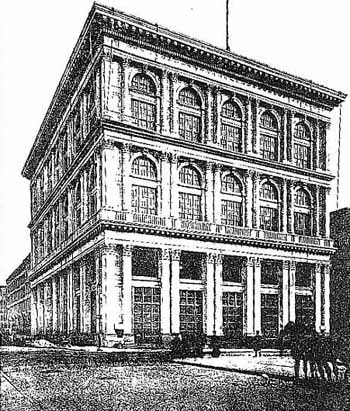

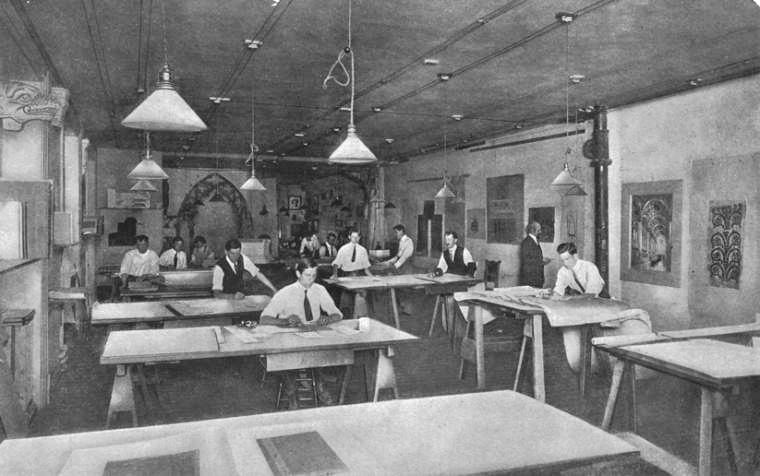

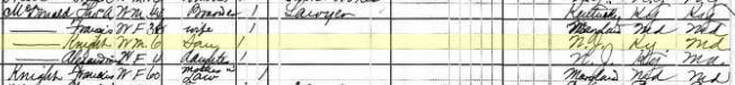

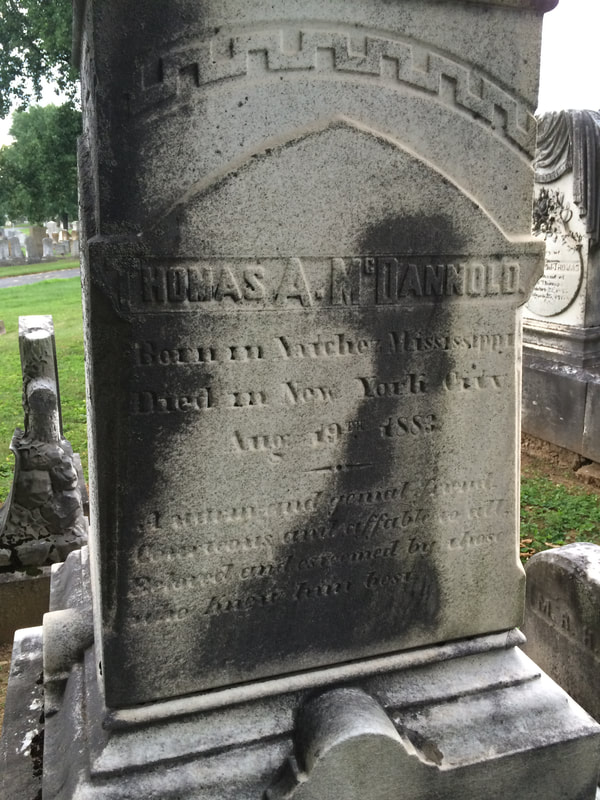

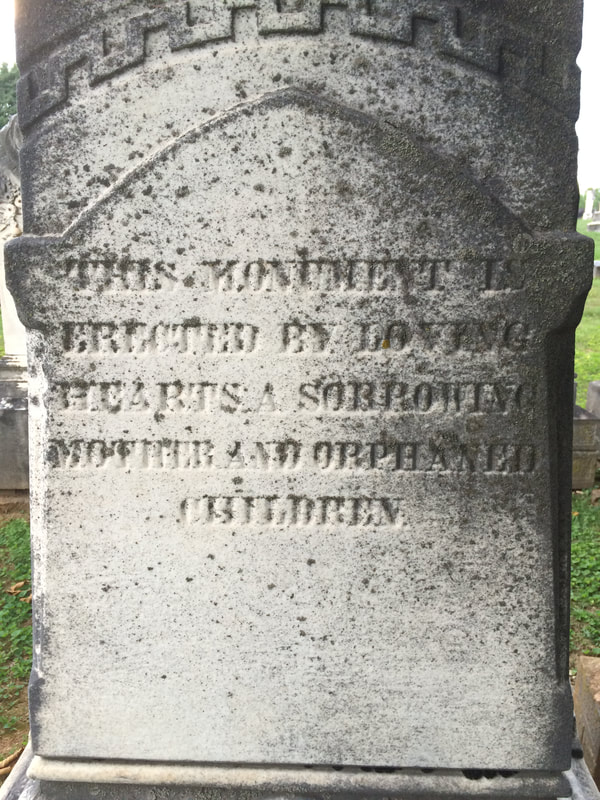

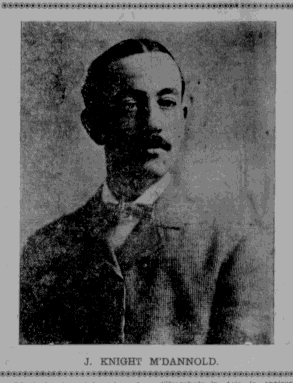

One of the most beautiful “stones” in Mount Olivet Cemetery was pointed out to me a few years back by my friend Theresa Mathias Michel. Over the years, Mrs. Michel has taught me a great deal about local history since our first meeting back in 1994. At that time, I was compiling a video documentary entitled Frederick Town for my employer GS Communications. More so, “Treta” Michel has been responsible for giving me several lessons on her own family members, and other notable figures in the rich annals of our town and county. Many of these folks reside in our fair cemetery, including Mrs. Michel’s brother, a former United States senator, the Hon. Charles “Mac” Mathias—a masterful local historian himself. A year-and-a-half ago, I found myself walking through Mount Olivet on a crisp autumn day, taking pictures of gravestones and the scenic grounds. My cell phone rang, and on the other line was Mrs. Michel’s personal assistant, Jennifer, asking if I would be available for an upcoming lunch date the next week. I replied in the affirmative and told her to pass on (to Mrs. Michel) that I was currently within yards of the burial spots of Mrs. Michel’s aforementioned brother, late husband Glenn, and parents. She abruptly directed me to stay where I was, and instructed her assistant to drive her out to the cemetery because she wanted to show me something special. Just fifteen minutes later, Jennifer pulled up to me in the cemetery, and Mrs. Michel told me to get in the car. I was driven to the southern tip of Area F, with a commanding view of the stadium entrance to Nymeo Field at Harry Grove Stadium. I helped my friend out of the back seat, and she proceeded to lead me up to a large, marble monument located not far from the car. It stood over eight feet tall and took the shape of an ornate Celtic cross. And when I say ornate, I mean master craftsmanship, designed with the inclusion of exquisite bas relief designs and portals. I asked, “So who is this John Knight McDannold?” (the name of the deceased individual lying under this monument). Mrs. Michel replied, “I have no idea, I just brought you here to show you this magnificent gravestone.” She then told me that her mother relayed to her the fact that this marble memorial was created by Tiffany’s of New York. I replied: “Thee Tiffany’s of jewelry and glass fame?” ”Yes, indeed!," she retorted.  Louis Comfort Tiffany Louis Comfort Tiffany I can’t do justice in describing the beauty and grandeur of this amazing art piece residing within Mount Olivet. However, a picture is worth a 1000 words, so I’ve included a few for this story. The Celtic cross is a form of Christian cross featuring a nimbus or ring that emerged in Ireland and Britain during the Early Middle Ages. A type of ringed cross, it became widespread through its use in the stone high crosses erected across the islands, especially in regions evangelized by Irish missionaries, from the 9th through the 12th centuries. In recent centuries, the Celtic cross became a popular design to incorporate into cemetery memorials. Through my research, I have failed to find any stories related to the creation of this particular monument, or a stamp or label saying Tiffany’s on the work itself (perhaps it’s on the bottom). I did find that other historic cemeteries in New York, Illinois and Kentucky have stones attributed to artist/designer Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933). The example in Illinois provided me with important context for our “Tiffany” here in Mount Olivet. This was a commissioned work for Edmund Cummings, an officer who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War under Gen. Ulysses Grant and Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. After the war, Cummings moved to Chicago and founded successful real estate company. Afterwards, he constructed an electric streetcar line called the Cicero & Proviso Street Railway Company. It should come as no surprise that the Cummings family had the necessary funds to approach the Tiffany Studios in New York. The testament to this prominent Chicago businessman resulted in a bas-relief angel carved into a soaring Celtic cross. It can be found in the Forest Home Cemetery at Forest Park, Illinois. Started as a stationery and fancy goods store in New York City in 1837, Tiffany’s became known for creating high-end silverware, glassware, and, of course, jewelry. Flash forward to the turn of the century (1900), still 60 years before Tiffany’s would surprisingly become known as a popular breakfast spot (at least for Audrey Hepburn in 1961). The firm, under the direction of Louis Comfort Tiffany, could be found designing and creating funerary monuments. I presume that our elaborate cross monument in question here in Mount Olivet was created in, or around, the year 1900 at Tiffany’s original studio located on Manhattan’s Fourth Avenue, between 24th and 25th streets. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find an exact delivery date to Frederick or project cost figure. I’m guessing like many “out of area” grave stones, and corpses, this was shipped via the railroad, and via cart or wagon to the cemetery from the freight station on South Carroll Street. Two other things are for sure: the monument was pricey, and likely did not arrive in one of those trademark Tiffany Blue Boxes. Mystery Person So back to the question I asked of Mrs. Michel back in October 2015, “Whose gravestone is this?” The answer—John Knight McDannold. At the time of his death, McDannold was arguably one of Frederick’s wealthiest residents. But why is he unknown? While we have plenty of McDonald’s Restaurants in the area, we lack a McDannold street, building or park. Who was this guy? I found John Knight McDannold to have an amazing pedigree. He seems to have lived a gilded life during the Gilded Age—one certainly deserving of a Tiffany headstone. Born in Orange, New Jersey on January 23rd, 1874, John Knight McDannold was the son of Capt. Thomas Alexander McDannold and Frances “Fanny” Beall (Knight) McDannold . Nearly a decade before John’s birth, Capt. McDannold was an unwelcome guest here in Frederick, the former hometown of his in-laws (John Knight and Frances Zeruiah S. Beall). It seems that the good captain (Thomas McDannold) was an officer in the Confederacy. More so, he was a member of Gen. Jubal Early’s staff. Of course, Gen. Early and staff are best remembered for inflicting a ransom of $200,000 on town back in July 1864. These Rebels threatened to burn the town to the ground at the time of the Battle of Monocacy. Luckily, the banking institutions came through with the necessary funds, and Frederick was spared…unlike Chambersburg, Pennsylvania a month later after failing to “ante up.” Ironically, it was Mrs. Michel’s brother, the aforementioned Sen. “Mac” Mathias, who in 1986 introduced legislation to Congress for the Federal government to repay Frederick for the money the municipality had to repay the banks for saving said hides. It was unsuccessful, but a noble attempt. After the war, Capt. McDannold, a native of Natchez, Mississippi took up residence in New York City and continued his pre-war occupation as a lawyer. In the 1880 census, six-year-old John was living with his family in the boarding house of Henrietta Knauff, located at 126 17th Avenue near the intersection with Irving Place. This is in the Gramercy Park neighborhood of east Manhattan. It is very likely that the McDannold family was no stranger to the many offerings of the Tiffany Company, located roughly 14 blocks away. John K. McDannold had a twin sister named Frances Celia, and another named Alexandra, born in 1876. Not much could be found on the McDannolds outside their fondness for traveling, which was said to have been done extensively. Perhaps all the jet-setting took its toll because the majority of the family was gone by the next census. Sister Frances Celia had passed in 1878 (age four). John’s mother, Frances, died in September of 1882. His father would follow his wife to the grave less than a year later in 1883.  Currier & Ives lithograph of a period cotton plantation in Natchez along the Mississippi River Currier & Ives lithograph of a period cotton plantation in Natchez along the Mississippi River The orphaned children (John and Alexandra) went to live with their maternal grandmother, Frances Zeruiah S. (Beall) Knight in Frederick, Maryland. Grandmother Knight was born in Frederick County in 1813, the daughter of William Murdoch Beall, a county sheriff hailing from the Urbana area. Mrs. Beall’s grandfather, Elisha Beall (1745-1831) was a veteran of the Revolutionary War—serving as a lieutenant in the Maryland battalion of the Flying Camp under Capt. Reazin Beall at the Battle of Long Island. His home, named Boxwood Lodge, still stands north of Urbana along MD355. Like her grandchildren, Mrs. Knight was supplied with a hefty inheritance left by her late husband John Knight, a successful merchant. Mr. Knight was originally from Frederick, but moved to Indiana with his family when he was ten. His father (Elijah) died that same year (around 1816), and his mother (Sarah Dix) followed suit three years later. He instantly became responsible for six little siblings. Knight soon hiked to Cincinnati on his own, and apprenticed in the printing trade. At 19, he went to Natchez, Mississippi and made a fortune as a cotton plantation owner and merchant. The young man came back to Frederick in 1833 and took Fanny Beall as his bride. Two sons were born to the couple in 1834 and 1835 respectively, but both died in the years following their birth. The Knights, likely devastated with grief, returned to Mississippi where their daughter Frances (Knight) McDannold (John’s mother) was born.  Enoch Pratt Enoch Pratt John Knight retired in the early 1850’s and took his wife and daughter to live in Europe. He shopped around and left his money and assets in the hands of a keen investor, a transplanted native from New England named Enoch Pratt (1808-1896). Pratt had moved to Baltimore and took an interest in civic affairs, later establishing a noted hospital and free library system. Mr. Knight had another notable philanthropist handling his monetary affairs in London—George Peabody (1795-1869). Letters found by a descendant in the 1950’s show that Enoch Pratt, an ardent Unionist, advised Knight to stay abroad during the turbulent years of the Civil War, thinking that his southern leanings could cause confiscation of his monetary holdings.  Biarritz, France Biarritz, France John Knight would not return to Maryland, and the US for that matter, during his own lifetime, dying in October 1864, just a few months after the Battle of Monocacy delayed Gen. Early (and his future son-in-law), allowing Gen. Grant to refortify Washington, DC against a Rebel attack. At the time of his death, the Knights were living in Biarritz, France, a resort town on the southwest coast of the country. Fanny Knight had the means in 1866 to have Mr. Knight’s body shipped across the Atlantic to be re-interred in Frederick’s new, “garden style cemetery,” originally opened in 1854. The two Knight children who died in the mid 1830’s had already been re-interred here in 1856, after being removed from the All Saints Episcopal graveyard. A large obelisk-style monument would be erected over his gravesite.

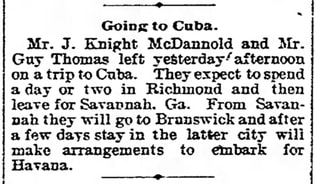

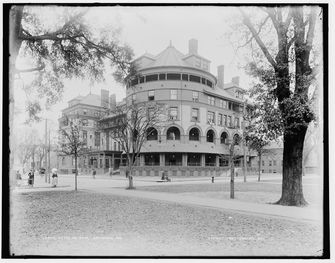

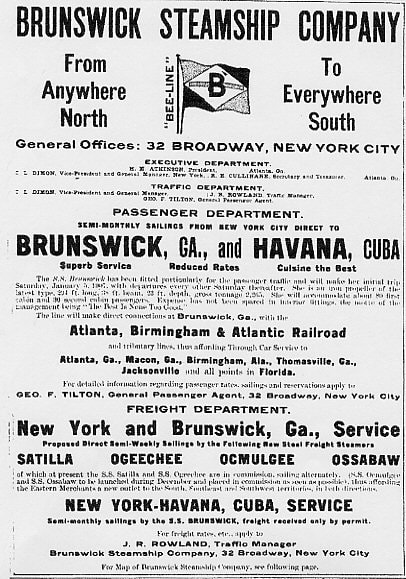

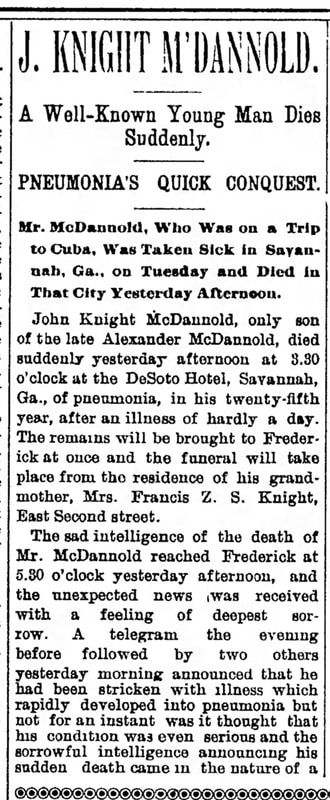

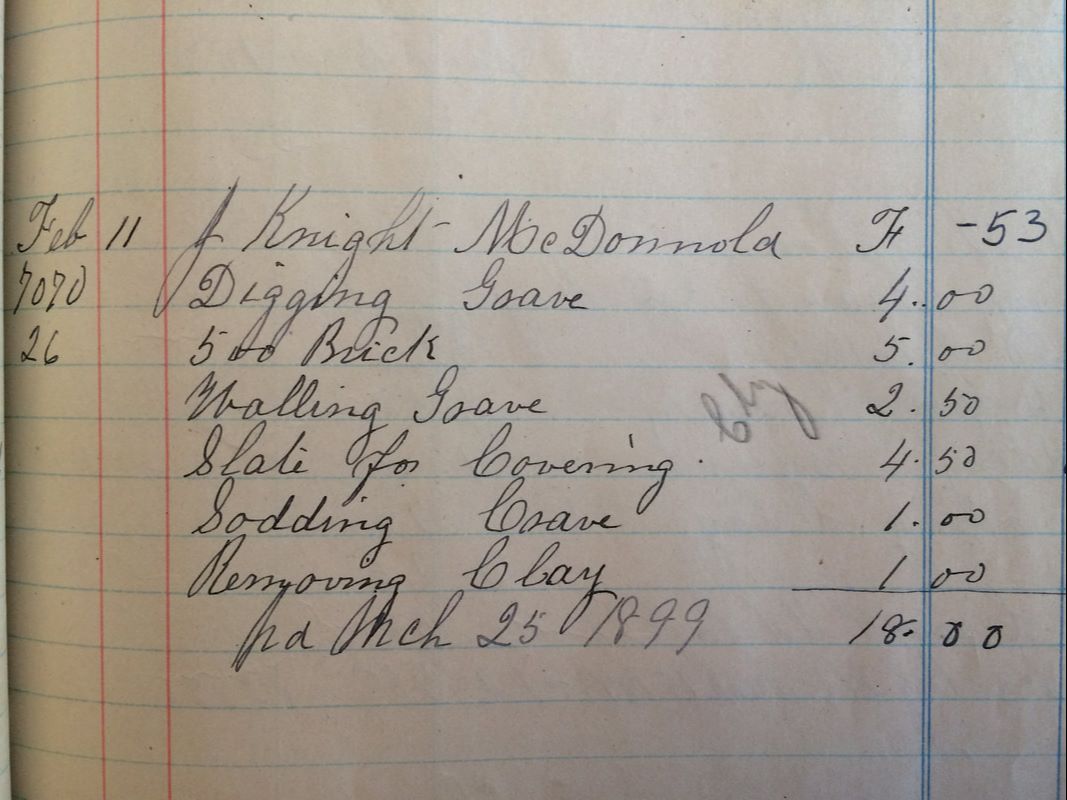

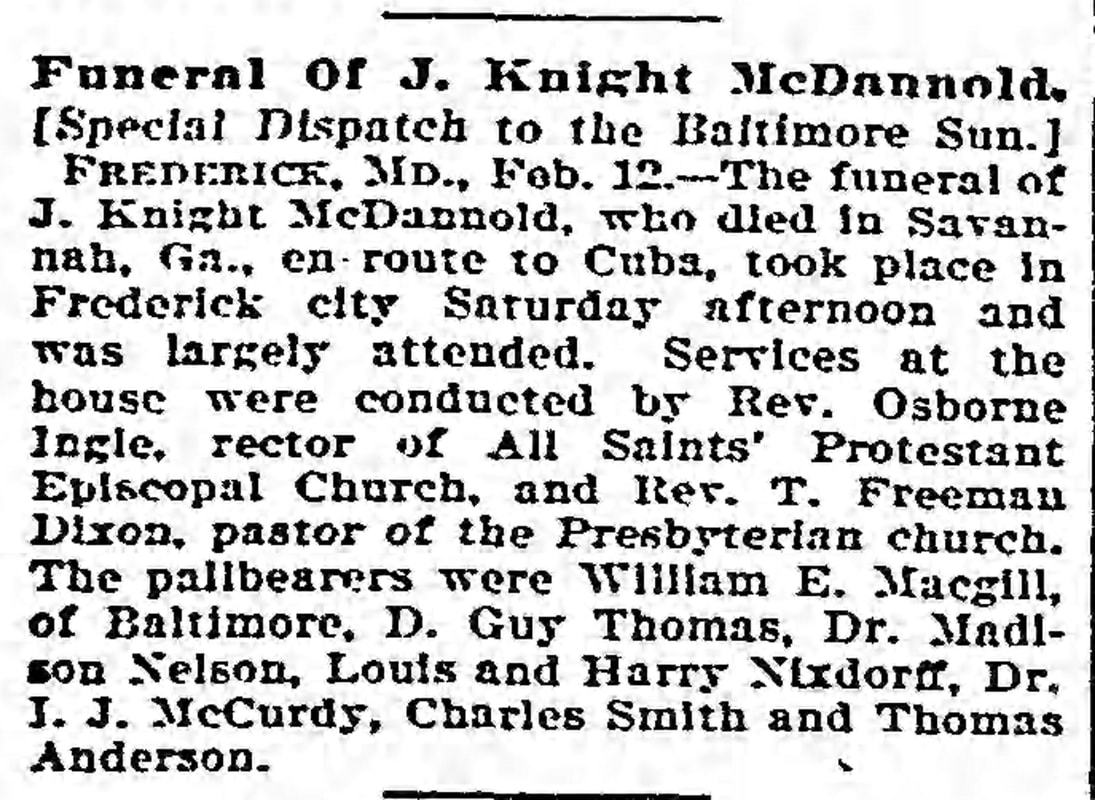

The Ill-Fated Mystery Trip In early February, 1899, John and friend Guy Clifton Thomas set out for a six-week sojourn with hopes of spending the remainder of winter in the warm sun of Cuba.  The Frederick Daily News (Feb 1, 1899) The Frederick Daily News (Feb 1, 1899) The departure of McDannold and Thomas from Frederick was a town event. It occurred on Tuesday, February 1st, 1899 and was even chronicled in the local newspaper. After spending a night in Richmond (VA), the duo next set out for Savannah (GA). The plan was to spend some time here visiting old friends before embarking for Brunswick (GA) where they would catch a boat for their tropical end destination. While in Savannah, McDannold and Thomas took up residence at the DeSoto Hotel.  DeSoto Hotel, Savannah (GA) DeSoto Hotel, Savannah (GA) John suddenly found himself hampered with an ailment which progressed into a heavy cold. Soon this inconvenience changed to pneumonia. Thomas telegrammed John’s grandmother and sister back in Frederick on February 7th, informing them of his companion’s malady. The next morning (February 8th) another telegram received in Frederick reported John’s condition having worsened overnight. Alexandra and her cousin Nannie Floyd quickly decided to make their way to John’s bedside in Georgia. The young women hastily packed bags and boarded the first train heading south. All the while, John K. McDannold’s condition continued spiraling downward. He would lose his fight at 3:30pm on February 8th. Word of John’s death was received in Frederick by telegram at 5:30pm. Alexandra would receive the heartbreaking news in Richmond while waiting to board a connecting train bound for Savannah. McDannold would never make it to his final destination of Cuba. Fate would instead carry his body back to Frederick, accompanied by devastated companion Guy Thomas. His death would make from page news, above the fold. John Knight McDannald would be laid to rest in the family plot (Area F/Lot 53) beside his deceased parents and grandfather. The funeral of John K. McDannold was very well-attended, and included friends with notable Frederick names remembered even today, such as Harry Grove, Ira J. McCurdy, Charles Doll and Harry Nixdorff. Alexandra and grandmother Fanny Knight likely placed the order in with the Tiffany Studio in New York for John’s elaborate grave monument. It may not have been in place for Mrs. Knight to see with her own eyes, as she would soon join her grandson in Mount Olivet, dying 17 months later (to the day) on July 8, 1900.  Miss Alexandra McDannold was now alone, but not for long. She kept up a life within social circles here and abroad, marrying in January, 1901. Her groom was Lawrence Rust Lee, a descendant of the famed Lees of Virginia, whose great-grandfather, Edmund Jennings Lee, was a first cousin to Gen. Robert E. Lee. The young couple made their home in Pittsburgh, where Alexandra’s husband worked for a large pump manufacturer. They would eventually have residences in nearby Leesburg and Washington, DC as well. Sadly, the Lees marriage would end in divorce in the 1930’s. Alexandra would die in the nation’s capital in April, 1955 at her Northwest residence at 3411 Newark Street. Alexandra McDannold Lee too would join her brother and extended family in Mount Olivet. This story certainly tested my genealogical skills, as I commend readers for keeping all the Knights, McDannolds, Bealls and lees straight. My biggest personal research surprise of all came in finding that Lawrence Rust Lee would marry again in 1956. He wed a lady named Louise Goldsborough (1888-1962)—an ancestral cousin of my wife, Ellen. Ellen’s middle name is Louise, and actually came from this woman, as she was a first cousin to Ellen’s grandfather. I guess it’s safe to assume, that when conducting history research of this time, one should always “GO LIGHTLY,” as you never know what you will find.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed