|

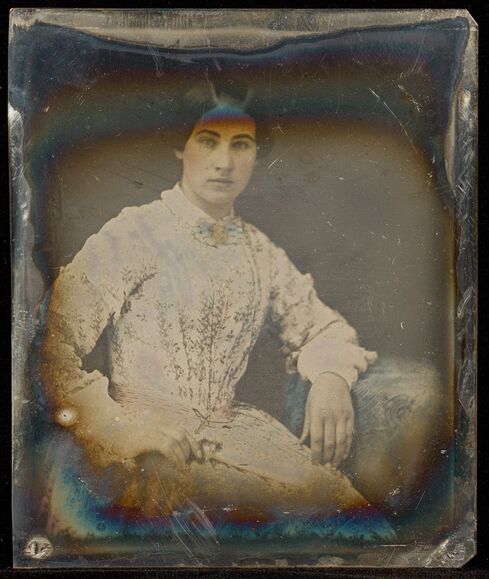

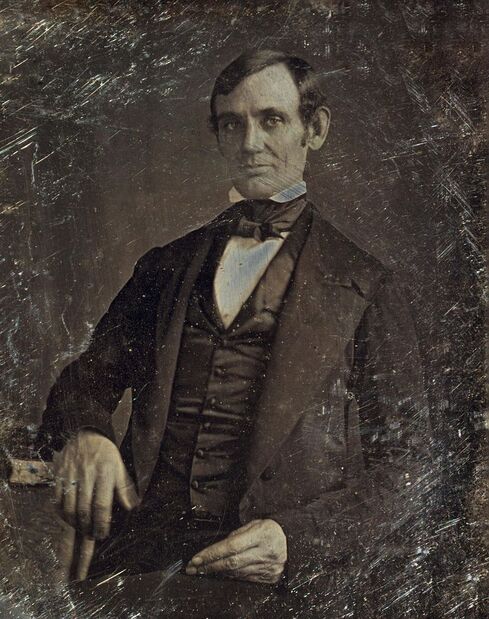

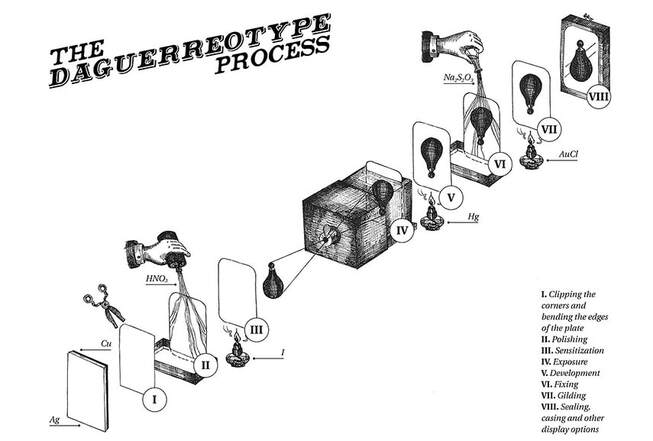

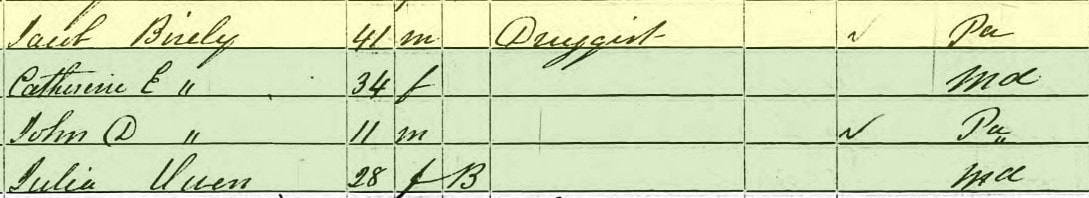

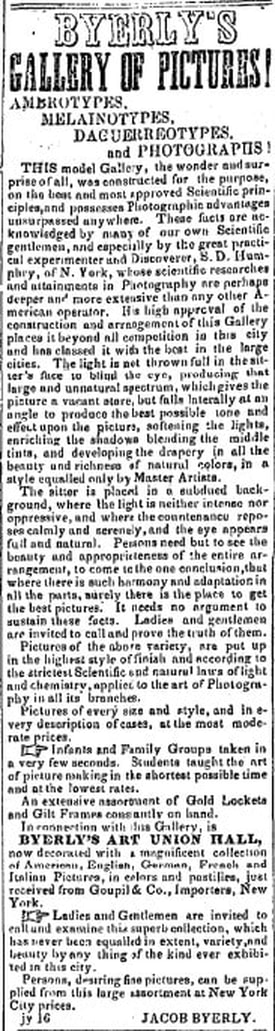

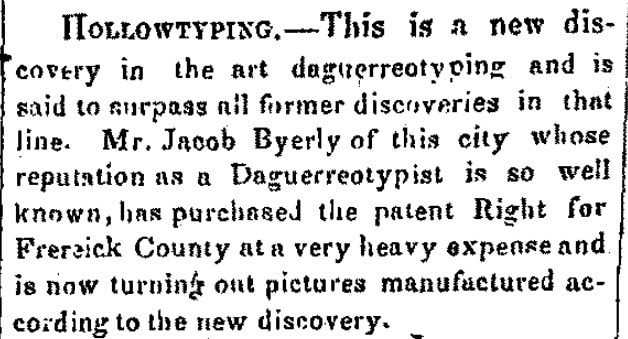

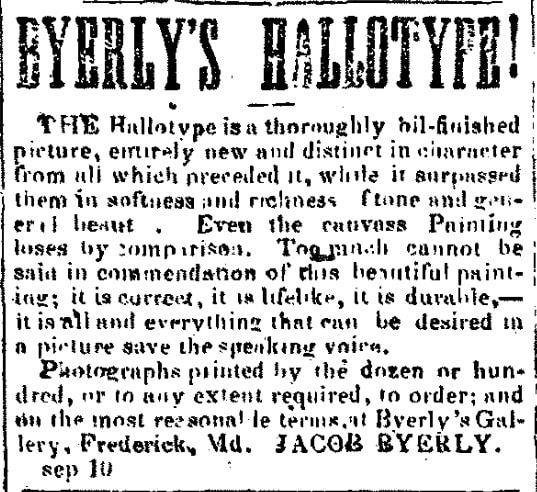

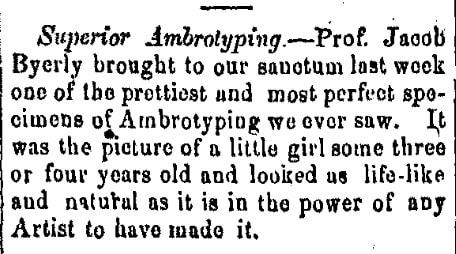

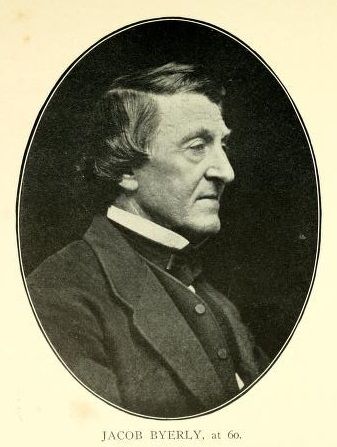

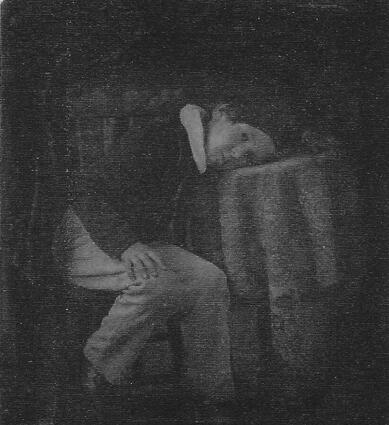

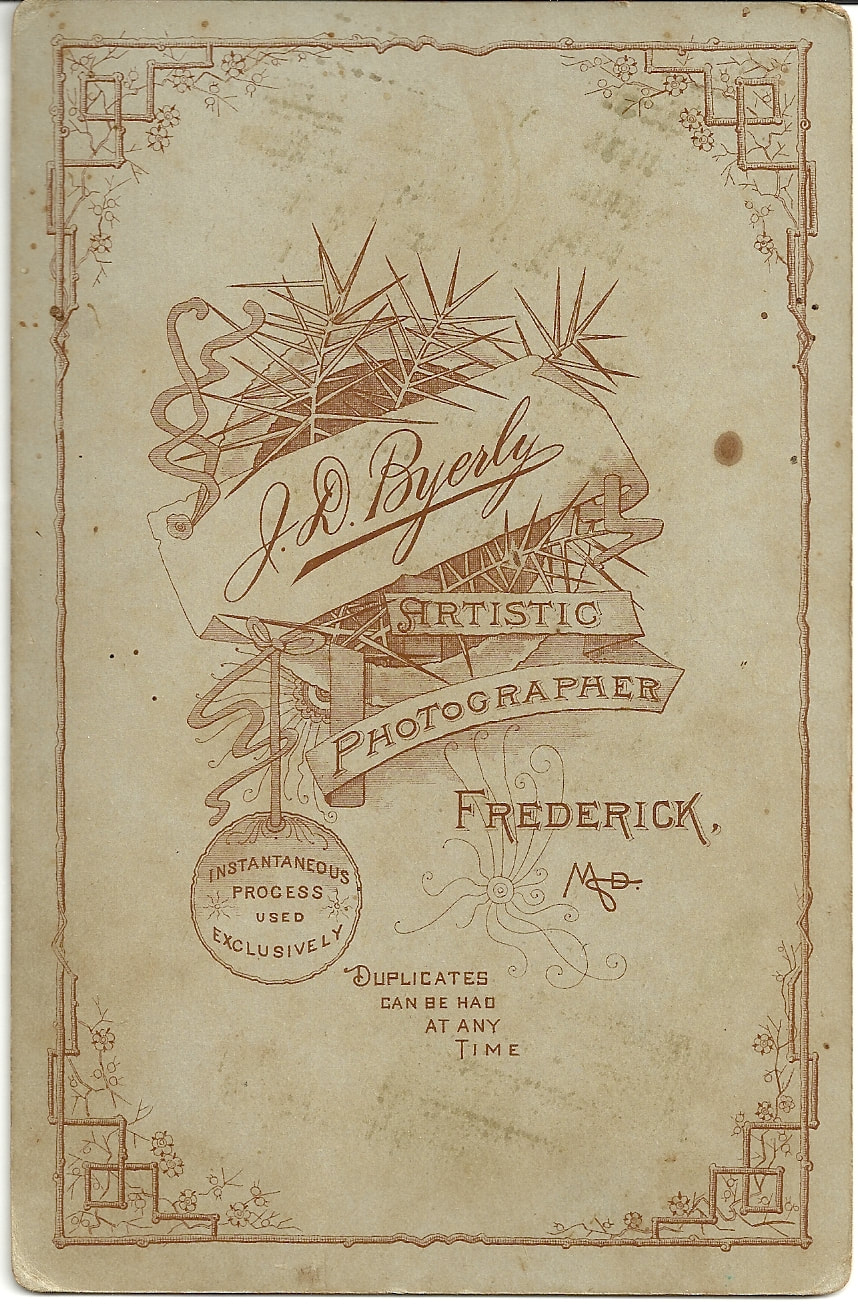

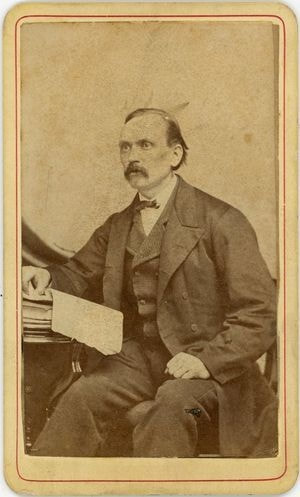

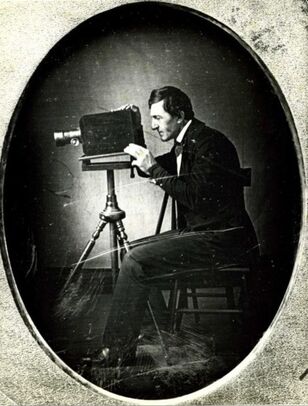

This is a continuation of a “Story in Stone” begun last week and features a proper chronicling of the famed Byerly family of photographers here in Frederick which spanned a century beginning in the 1840s. For those that read last week’s story entitled “Up From the Meadows,” you were introduced to a photograph featuring a former slave turned freeman named Luther Potts, holding a five year-old boy on his lap. There is a discrepancy as to whether the child in question is either John Davis Byerly (Jr.), or kid brother Charles Byerly. I surmised John D. (Jr.) and hedged my bet based on a Byerly family descendant’s unknowingly stating that the boy was John Francis Byerly. I proved the error, and deducted that John was the name of the pictured child regardless, as John Francis Byerly was a grandson of the photographer, not born until 25+ years after this photo was taken. This photograph, along with hundreds more that dominate local history books in the era mentioned, is part of a portfolio collection of antique images equivalent to Jacob Engelbrecht’s masterful diary. Each photo is reminiscent of one of Jacob’s colorful journal entries, magically documenting an earlier Frederick, with emphasis on the 19th century. We owe a great deal to both these men named Jacob.  CDV of Unknown young lady (c. 1860) CDV of Unknown young lady (c. 1860) As professional photographers, three generations of Byerlys took staged portraits in their studio once located in the first block of Frederick’s North Market Street. In addition, these talented artists captured unique town events and typical street scenes. In all cases, we have “photographic” proof of many former residents of both Frederick (and Mount Olivet), town happenings and Frederick structures—many still standing, and others long gone. Sadly for historians and genealogists, many Byerly portraits of individuals, couples and families have survived the test of time, but have no identification of who is pictured. A common practice in days of old involved writing names of those appearing in pictures in ink on the photo album page itself that once held and housed these photographs. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line, loose photographs became separated from their identification. Today these appear on eBay and in antique shops and thrift stores with a nearby label announcing “Instant Relatives.” We certainly commend those ancestors who wrote names on the back of portraits, or, in other cases, wrote on the photo themselves (at least) giving us an “inkling” of who was photographed, and/or where and when. I appreciate these old-time photographs so much, and in my personal family history collection have both marked, and unmarked, photos. My sleuthwork has been utilized as well in identifying several based on period dress, and facial features. In thinking of photography, I have to smile while reminiscing about the traditional 24 or 36 exposure rolls of film utilized in my younger days in the era before digital photography. Who would have imagined a handheld smart phone computer/camera/”Walkman” doo-hickey that you could carry with you at all times? Do you remember having to “ration” remaining film “exposures” on a limited film roll while on vacation or social events? One had to treat them like gold and be judicious in using up remaining pictures just in case something incredible happened like Bigfoot coming out of nowhere, a visit from a unicorn, or meeting Olivia Newton-John. Maybe I digress, as I am confusing my adolescent dreams with the possibilities of reality on that last one—as evidenced by my seeing the movie Grease multiple times at the theater by myself. I just shudder (or should I utilize the camera term, “shutter”) to think of the future where we will likely be overrun as a society by unidentified digital .jpg photograph files of people, places and events. Luckily, the Byerlys didn’t have any of these problems, but being pioneers in their field, brought several other challenges. It’s obvious that trying to get the right picture back in the 1800s was a hundred times harder than today with the equipment involved, and lack of automatic features to adjust lighting, filters and shutter speed. Jacob Byerly The most prolific photographer in Frederick County history was Jacob Byerly, born in Newville, Pennsylvania in 1807. Newville, near Chambersburg, was founded in 1790 and is located in Cumberland County, due west of Carlisle. The Byerlys (or Birelys before Jacob changed the spelling for himself) were a typical Pennsylvania German family, hailing from immigrant John Andrew Birely (1715-1774) who came to America and the Penn’s colony in the year 1738 from Rohrback, Heidelberg, Baden-Wurttemburg. This was Jacob’s great-grandfather who eventually settled and died in Lancaster. Named for his grandfather, Jacob Byerly (the photographer) was the son of John Henry Birely (1773-1813) and wife/cousin Rebecca Baer (1782-1851). Jacob Byerly was the oldest of four children and is said to have started as a teacher, but made the transition to the new field of photography at its introduction to this country. He possibly learned his future trade from a daguerreotypist in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, but information is not definitive. If you have never heard of the profession of daguerreotypist before, an individual in this line of work made daguerreotypes, the first publicly available photographic process and widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. Invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839, the daguerreotype was almost completely superseded by 1860 with new, less expensive processes, such as ambrotype (collodion process), that yield more readily viewable images. The first authenticated image of Abraham Lincoln, a daguerreotype of him as U.S. Congressman-elect in 1846, is attributed to Nicholas H. Shepard. Wikipedia does a nice job describing the process employed in making these early photographic images: “To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish; treated it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive; exposed it in a camera for as long as was judged to be necessary, which could be as little as a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or much longer with less intense lighting; made the resulting latent image on it visible by fuming it with mercury vapor; removed its sensitivity to light by liquid chemical treatment; rinsed and dried it; and then sealed the easily marred result behind glass in a protective enclosure. The image is on a mirror-like silver surface and will appear either positive or negative, depending on the angle at which it is viewed, how it is lit and whether a light or dark background is being reflected in the metal. The darkest areas of the image are simply bare silver; lighter areas have a microscopically fine light-scattering texture. The surface is very delicate, and even the lightest wiping can permanently scuff it. Some tarnish around the edges is normal.” I’m sure being a daguerrotypist was a highly rewarding job based on customer satisfaction and ego stroking. He was a true pioneer in this new field, one that fast rivaled portrait painters, and made the acquisition of family images possible for the less affluent. However, as the description above reads, it was tedious work that involved great patience, while exposing the technician to very dangerous chemicals without the necessary protections we expect today.

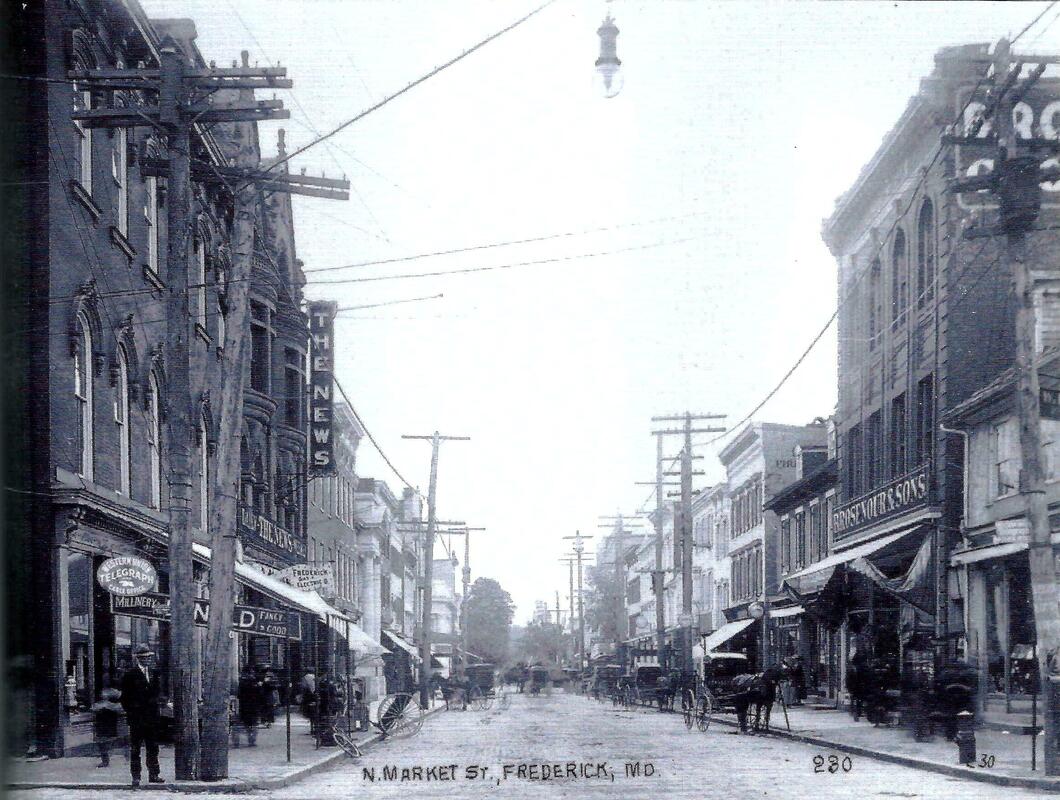

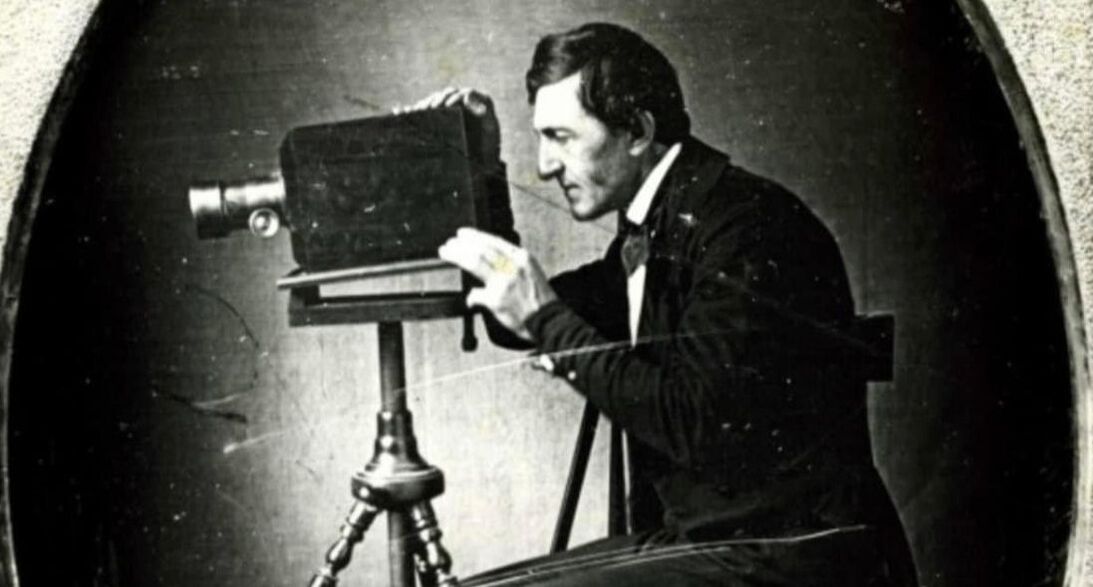

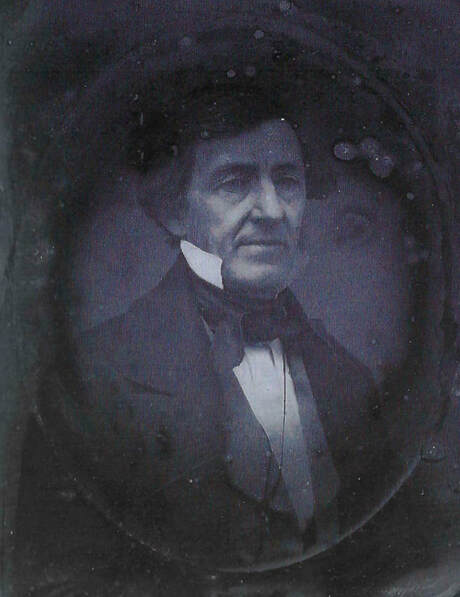

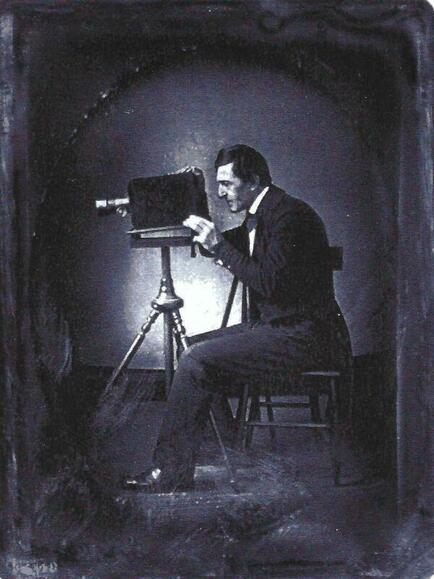

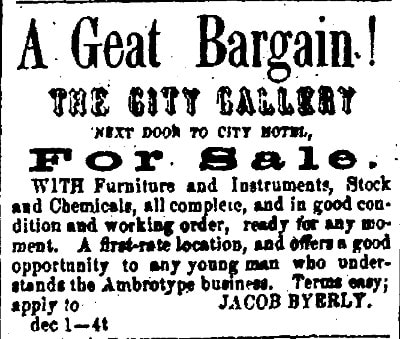

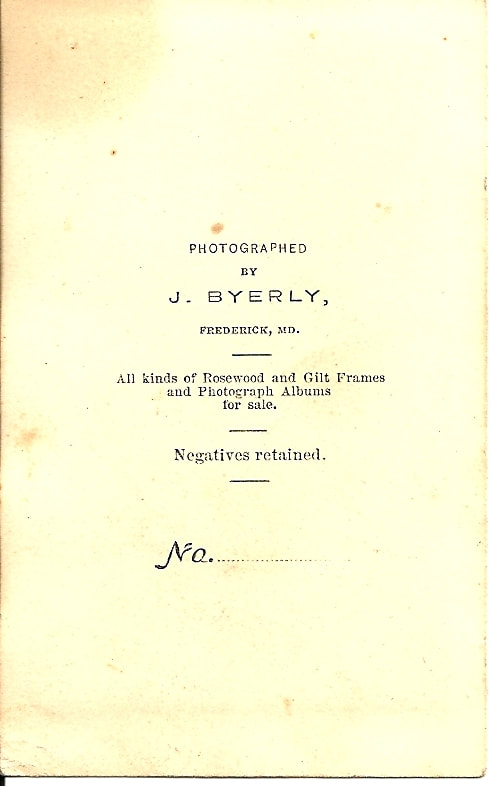

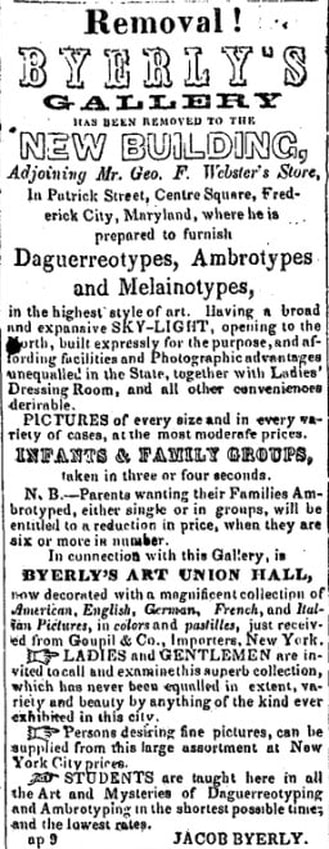

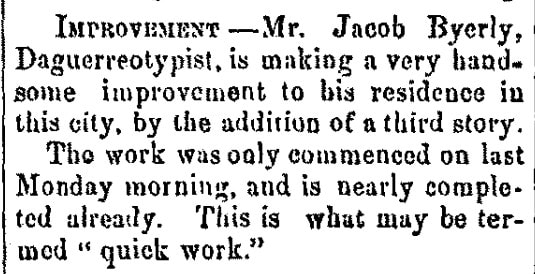

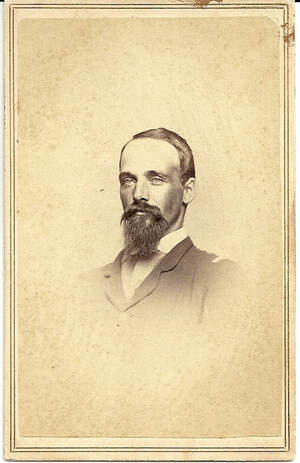

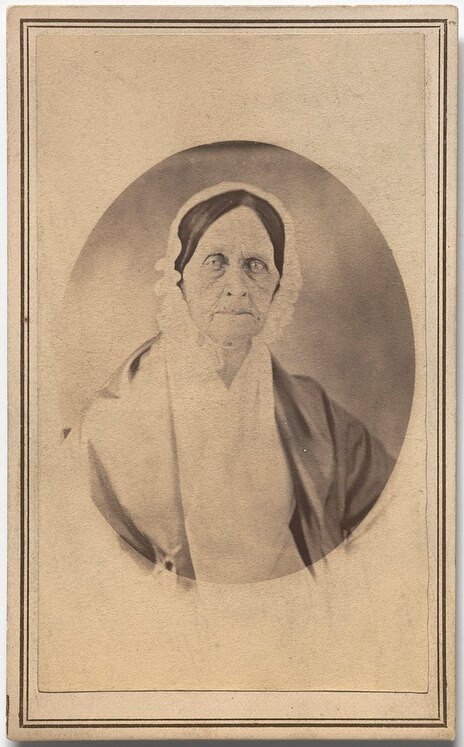

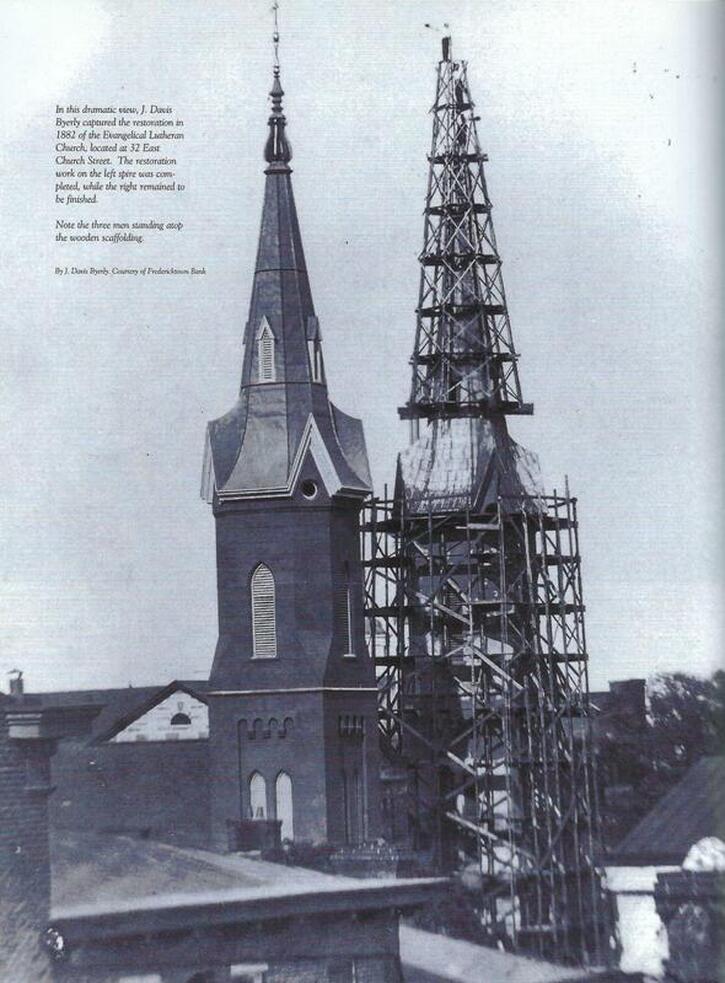

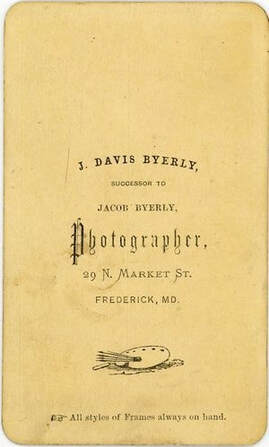

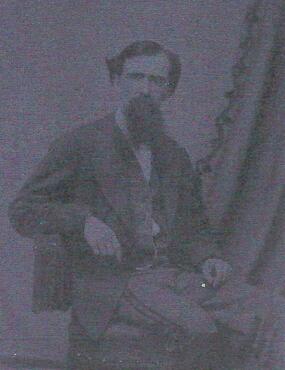

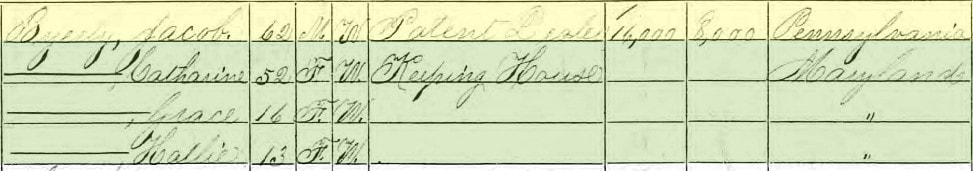

Jacob Byerly eventually set up shop as a daguerreotypist, one of the first people in Maryland to sell this new technology. He was originally located next to the City Hotel on West Patrick Street, and he named his business "The City Gallery." I feel that his first place of business doubled as his home as well. Jacob Byerly later established an artist studio at 29 North Market Street, which later became the Young Men's Shop and also served recently as Hunting Creek Outfitters and has recently re-opened as loulou, a store that will specialize in ladies accessories, gifts and fashion. He bought 29 North Market in 1851, and the structure, later to be named the Byerly Building, stayed in the family until its sale in 1965 by his great-grandson John Francis Byerly.  Looking south on N. Market St. from intersection with Church St. The Byerly Gallery is on the right (west side of street) and is the second building down (left) of the visible large brick store of Rosenour & Sons. In the magnified view below, see the letters "PHO" (the start of Photographer) on north side of building. The word Byerly was most likely stacked over the word Photographer(s) or Photo Gallery. The family lived on West Patrick Street in the 1850 Census, and earlier in the 1840s. I think this was in conjunction with Jacob's "City Gallery" next to the City Hotel. In 1853, Jacob purchased 108 West Patrick Street, and a few years later installed a third story. And if I’m not mistaken, this same West Patrick property was the earlier home of Revolutionary War era patriot John Hanson. Hanson’s statue stands in front of the Frederick County Courthouse, and he is best remembered for his tenure as president of Congress assembled under the Articles of Confederation. You may also here his name spoken by your car’s GPS if you happen to be traveling in the Annapolis Area on US Route 50—aka John Hanson Highway. The US-50 freeway from the District of Columbia to Annapolis was opened around 1957. Shortly after taking ownership of the house, the couple welcomed two children—Grace in 1855 and Harriet (aka Hallie) in 1857. I saw a few instances that pointed to another child who died in infancy but could find nothing definitive. Jacob's work earned him a mention in a book entitled The Camera about the history of photography published by Time Magazine in 1970. In this, he is hailed as a “trailblazer” in the photographic field, and held in the same company as the legendary Matthew Brady, who would open his studio in New York City in 1844—two years after Byerly opened his gallery in little old Frederick. An article written by a distant relative, Carol Zeigler claims that Jacob Byerly was personal friends with Matthew Brady, and for a short time may have photographed with him although there exists no real proof. At the onset of the Civil War, Jacob Byerly is said to have produced 1,500 images annually with the help of two male employees, one being son Charles. While Matthew Brady gained his fame with depictions of battlefield carnage, Byerly is credited with at least a few surviving documentations of his adopted hometown during the war. These photographs were taken from his upper-story studio while looking out the window onto North Market Street. He captured each of visiting armies at different times of the war. In fact, a few of the most famous civilian-related portraits dealing with the American Civil War came to light thanks to Jacob Byerly. These helped put Frederick on the map, so to speak, because they assisted in providing photographic proof of the existence of a particular resident “patriotic heroine” and the home from which she apparently waved a flag at Gen. Stonewall Jackson and his “invading Rebel horde” in early autumn of 1862. It is said that his portrait of Barbara was not done in his Market Street studio, but rather was taken at his “demonstration” booth which was set up at the Frederick Fair in 1860. The Agricultural Exposition was then held at the Hessian Barracks, the site that serves as home to the Maryland School for the Deaf today. Barbara was a Hauer family relative and great aunt of Jacob’s wife, Catherine, and this was probably the only reason the fabled nonagenarian allowed her image to be captured. I first encountered information about Jacob Byerly while researching the Fritchie images for a history of Frederick documentary back in 1994. A year later, I would learn so much more about Mr. Byerly from Tom Gorsline, former publisher of Diversions and Frederick Magazine. A huge fan of vintage photography, Tom has amassed a great collection of local imagery and regularly published many of his finds in his publications for all to enjoy. He was a great admirer of the Byerlys, so much so, he devoted an entire chapter of his 1995 Pictorial History of Frederick to educating readers about the incredible legacy left us by this legendary artist and his son and grandson. Tom’s book is packed with Byerly images, and naturally gives us an opportunity to see what the photographers, themselves, looked like. These were the first official “selfies” in Frederick history! Tom includes a few of Jacob's iconic town shots in his pictorial history, in which he was greatly assisted by talented history researchers/ writers Nancy Whitmore and Tim Cannon. One such image included the restoration of one of the famed “Clustered Spires” belonging to Evangelical Lutheran Church. If you look closely, you can see workmen waving to the camera from their scaffolding. Another shot features the disaster scene of Frederick’s first “Great Flood,” this one occurring in late July of 1868. His view of West Patrick Street (looking west) vividly shows the devastation. This scene was right outside his home and ironically, the legendary freshet was responsible for the destruction (and subsequent dismantling) of the earlier photographed Barbara Fritchie House. (Note: The replica house you see today was constructed around in the late 1920s). Text from the Pictorial History of Frederick states: “Jacob remained on the cutting edge of the technology of his day, switching to the glass-plate technique. Remarkably, at least a thousand glass-plate negatives from the three Byerly photographers have survived the decades. Jacob produced portraits, slides for the stereopticon (the TV of the time), and carte de viste, a popular form of calling cards with photographs on them. He sold the business for $2,000 to his son, John Davis, in 1868, but continued to take pictures until his death in 1883.” Years before, in 1852, Jacob is said to have written the following passage in a letter to his 14-year-old son, John Davis Byerly: "My son, remember the instructions of your Father; — trifle not away your time; reflect, and be careful, read your bible, neglect not its precepts, But take good heed to its instructions, and live accordingly; trample not upon the many good admonitions I have given you . . . “ Jacob was always the teacher, and looking back at the life of John Davis Byerly, it’s safe to assume “he knew the assignment” as the kids say today. Davis was brought in as a named partner to his father in 1863, as the firm became known as J. Byerly & Son. Davis apparently had a stormy relationship with his stepmother according to other letters. He received education both here in Frederick and abroad as a biographical sketch in the Maryland State Archives summarizes: “According to Williams and McKinsey's History of Frederick County, Davis received his education in the schools in Frederick; however, he was probably not at school in the city, because a letter from his father in November of 1853 or 1854 expresses his concern at the fact that Davis had to share a room with the three Fischer boys, who seem to have been disapproved of by the elder Byerly. Exhorting his son to 'be studious, make the most of your time you possibly can, recollect you are costing upwards of fifteen dollars a month,' Jacob continues later in his letter, 'Try to excel; and stand among the first in your school in the estimation of your Teachers. This will reward me, and be a plume in your Cap; I don't want you to be running home every few weeks, it looks badly. I don't expect you home until Christmas . . .' Due to the fact that Davis was far enough away to be boarding, and his parents to be sending him things rather than bringing them, but close enough to be 'running home every few weeks,' it is probable that he was at one of the private schools in Frederick County.”

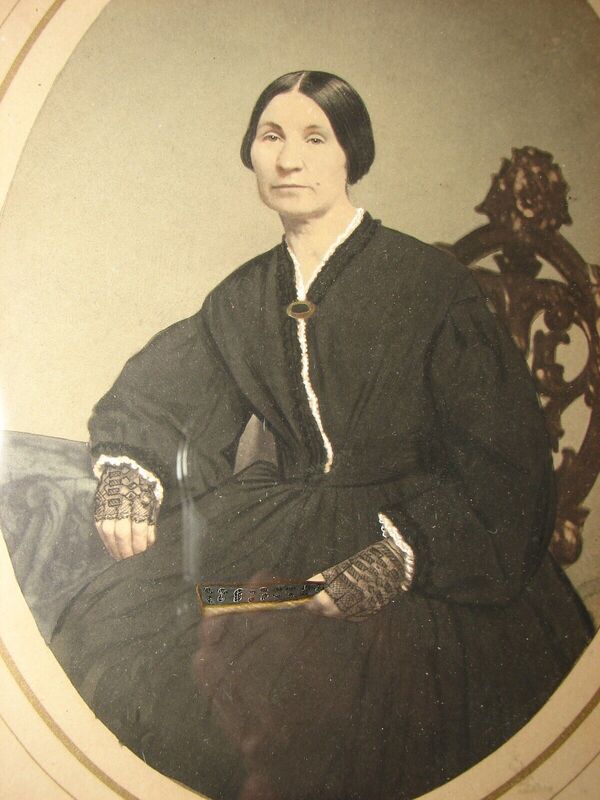

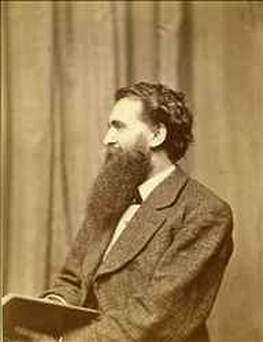

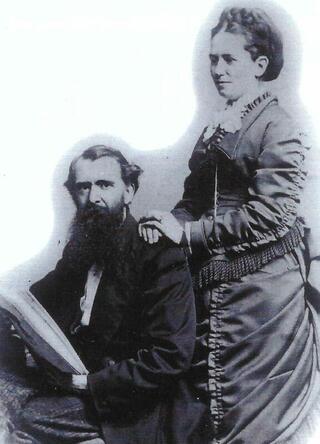

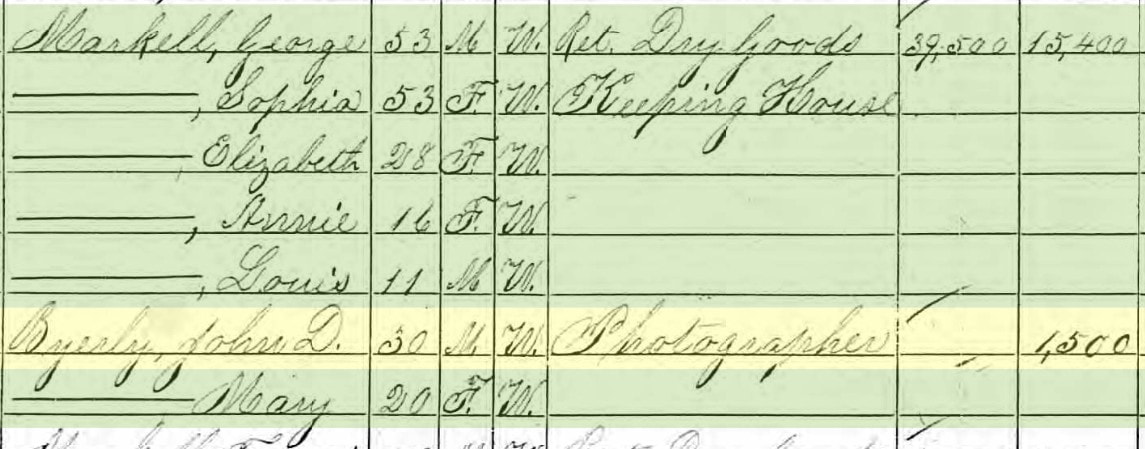

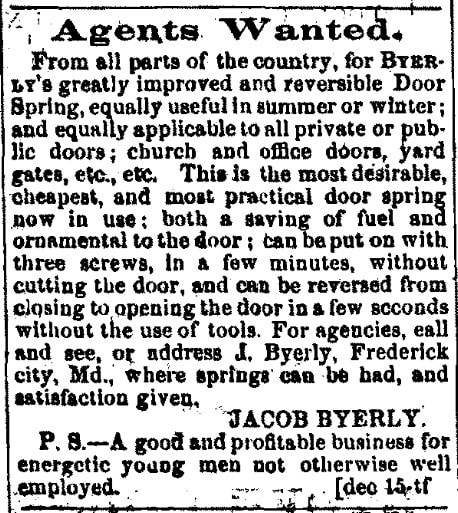

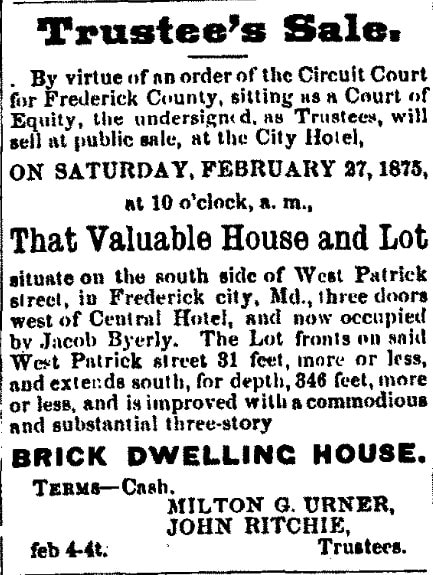

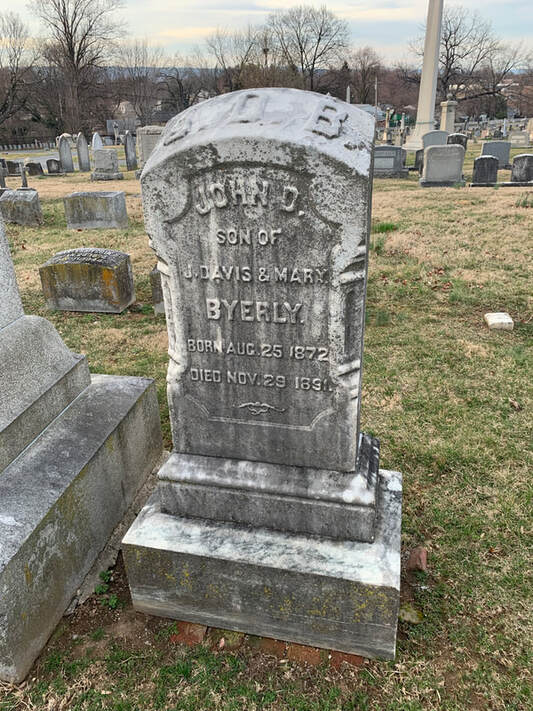

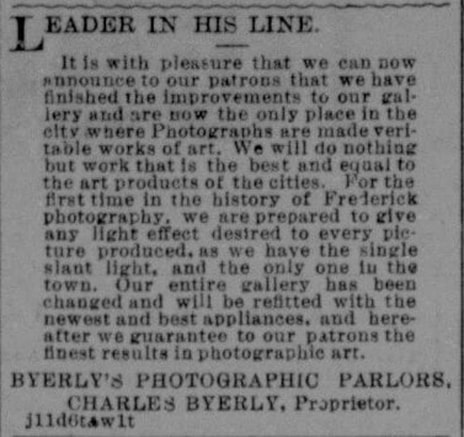

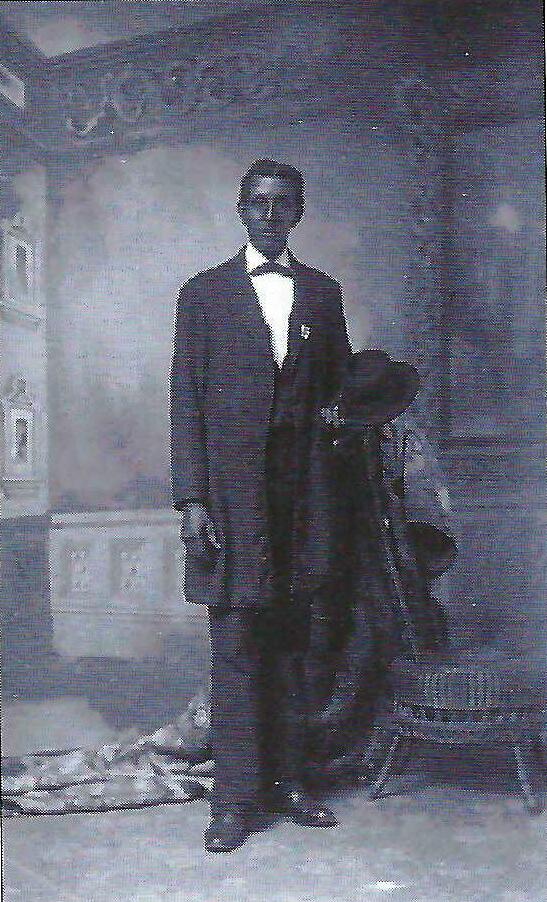

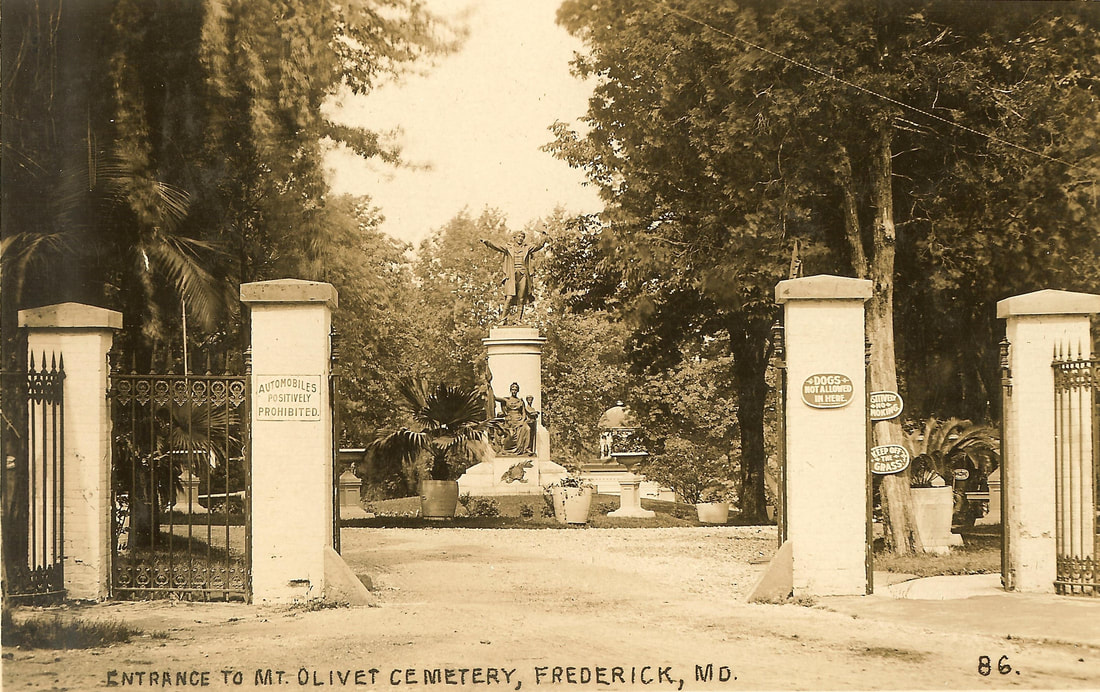

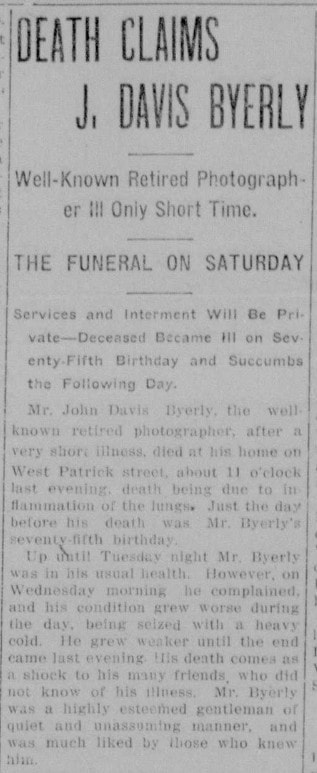

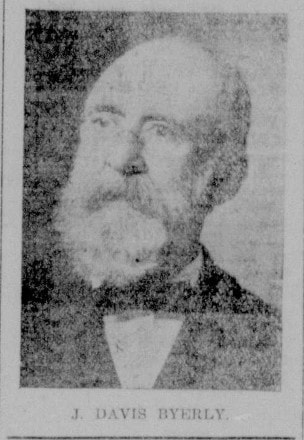

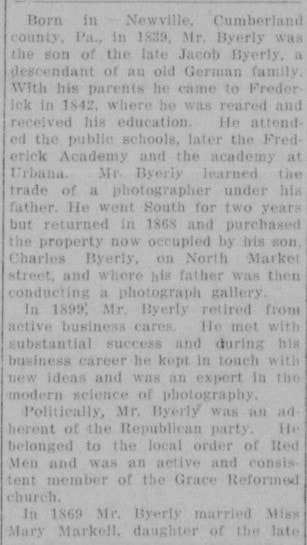

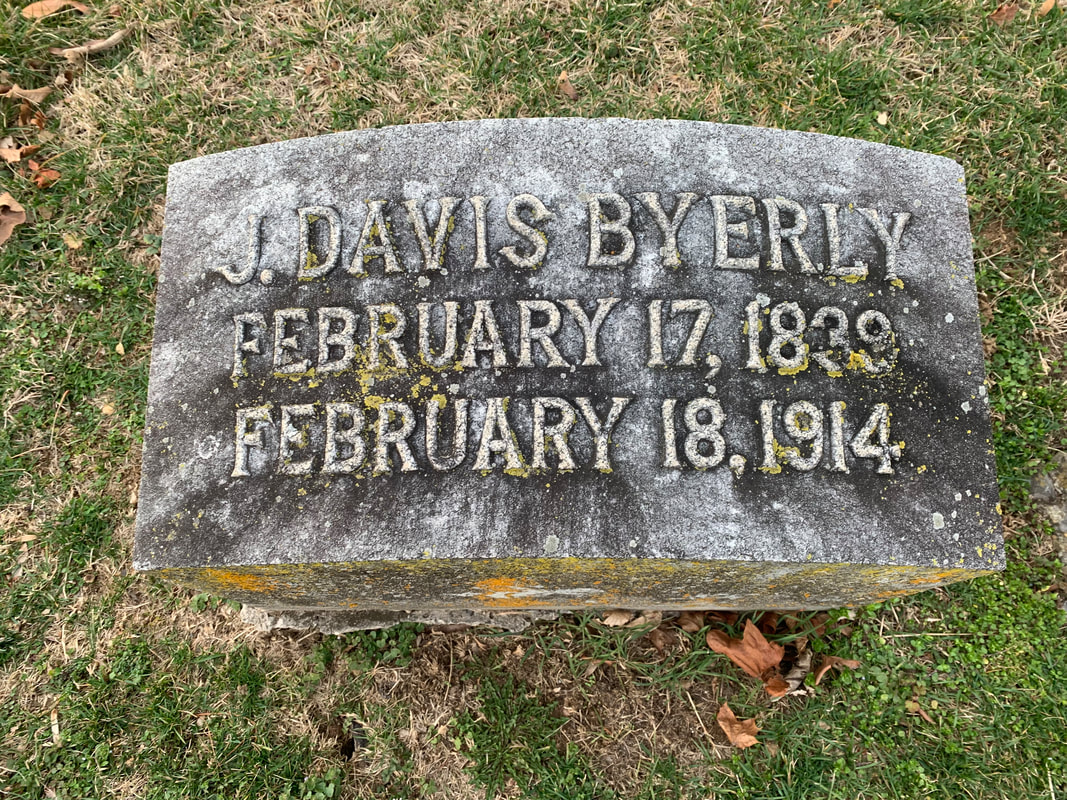

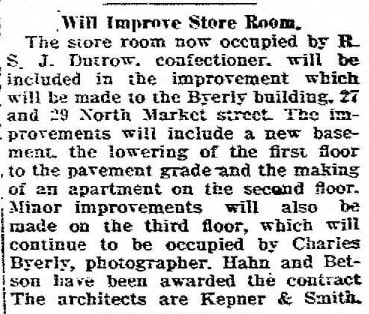

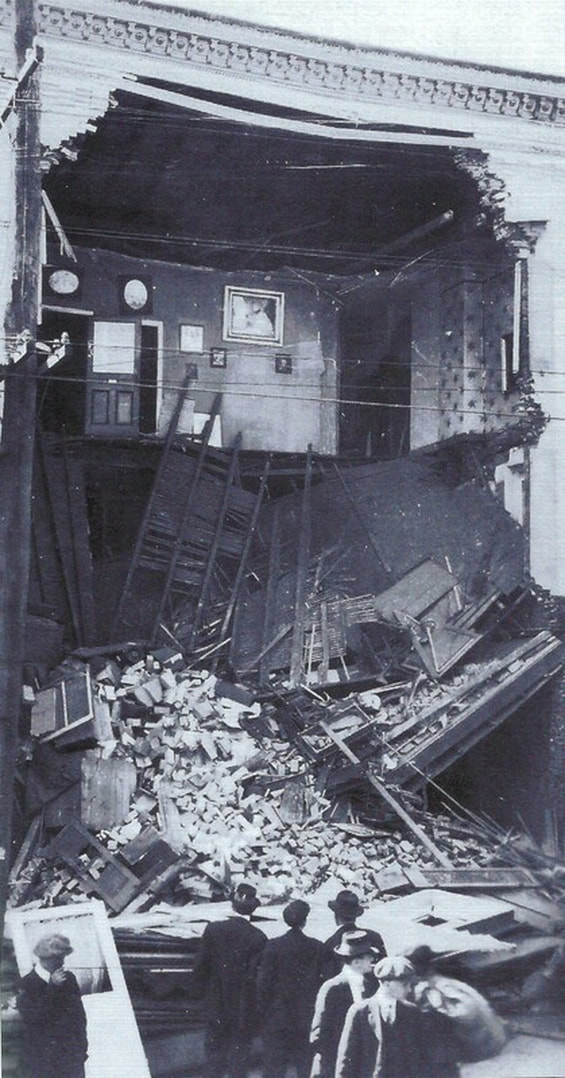

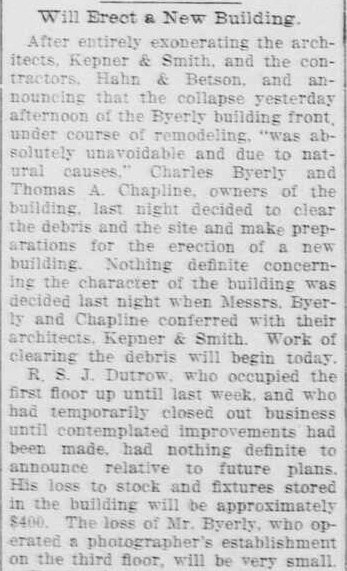

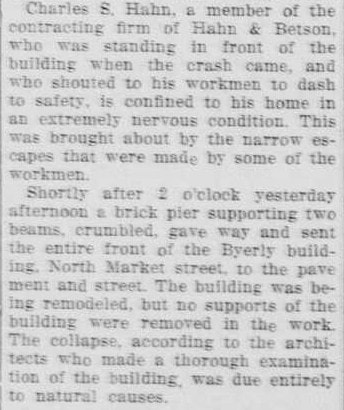

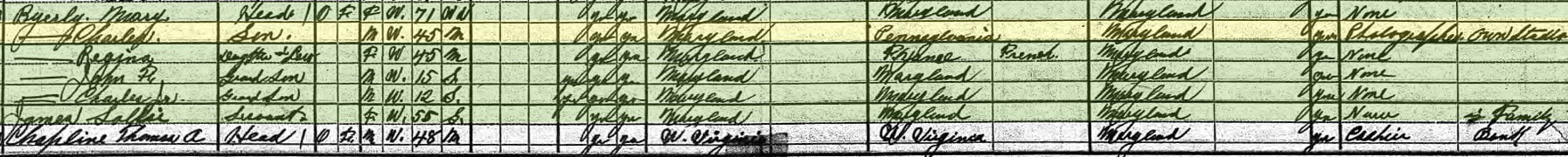

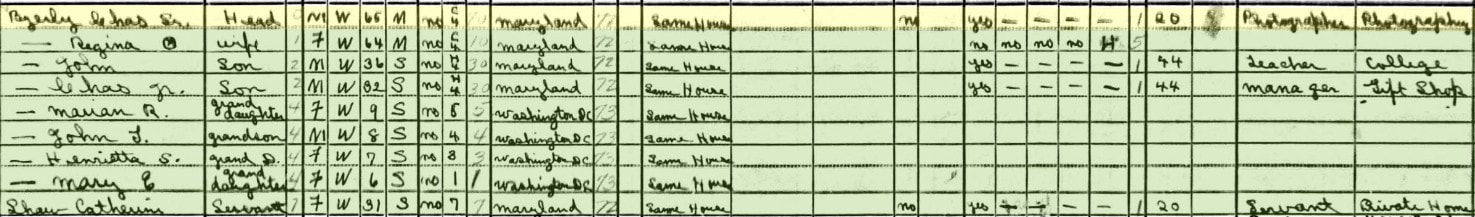

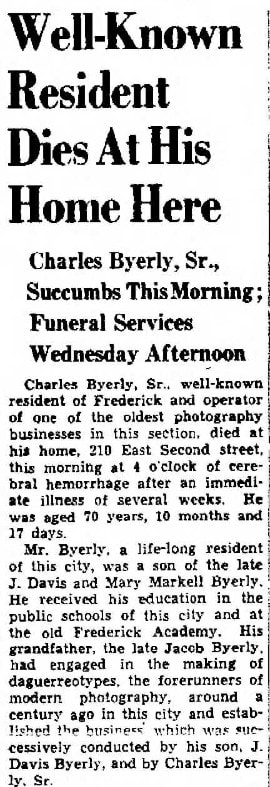

“Mame” Markell lived next door to the Byerlys in a connecting townhouse. Her father (George Markell) had bought 110 West Patrick (the other part of the former Hanson House) in 1852. J. Davis Byerly would wed his neighbor in late October of 1869 and they would soon become the parents of three children—Mary Catharine (1871-1937); John Davis (Jr.) (1872-1891); and Charles (b. 1874-1944). In addition to un-posed, event-driven pictures, Davis Byerly experienced great success as a portrait photographer as well. Heritage Frederick apparently has a copy of a booklet the Byerly photo studio gave out to patrons before they sat for a portrait. It reads: "Photography is not a branch of mechanics, whereby a quantity of material is thrown into a hopper and with the grinding of grim, greasy machinery, beautiful portraits may be turned out. The day when a daub of black and a patch of white pass for a photograph, you are well aware is ended; for you will not receive such abominations yourself as likenesses of those near and dear to you, and especially of the one dearer to you than anyone else, namely your own dear self." Hints are given to "never come in a hurry or a flurry" because a red face does not photograph well. "Ladies who have shopping and an engagement with the photographer on the same day, will please be careful to attend to the latter first." As to how to dress, the Byerlys rebuke those "who place upon their persons, when about to sit for a picture, all sorts of gew-gaws and haberdasheries which they never wear when at home or when mingling among their friends." Meanwhile, Davis’ father, Jacob, kept occupied with work as a patent dealer and advertisements in local papers showed him marketing door springs. He also busied himself with hobbies and activities of town, however had his own mortgage foreclosed upon in 1875, and the house at 108 West Patrick ended up being bought by Mary “Mame” (Markell) Byerly (wife of J. Davis Byerly). In her will, Mary would leave the house and lot to her daughter, Mary (Byerly) Chapline and it would stay in the family until 1971. The Byerly Picture Gallery flourished under Davis' direction as he was able to hire and train several assistants, two at least of whom later became competitors of his in Frederick in W. A. Burger and William F. Kreh. Business continued to be good for the Byerlys. In 1880, John Porter described the Byerly Picture Gallery in his book Maryland and its Industrial Developments: "It is situated in the best possible location in Frederick City, has large, well lighted rooms, and possesses every advantage which modern invention can suggest . . . Examination of his portraits shows a pleasing and agreeable variety -- the positions given have an ease and grace not often attained by photography, and in this, together with the admirable finish of his work, may be found the secret of Mr. B's great success. . . ." J. Davis' great success in the 1880s and 1890s was marred, however, by a series of personal tragedies. Jacob Byerly died March 21st, 1883, at the age of 76. He was originally buried in the German Reformed burial ground on North Bentz Street at the intersection with West 2nd Street. (This is Frederick’s Memorial Park today). Forty years later, Jacob’s body would be brought to Mount Olivet and laid to rest in Area G/Lot 182. Davis' stepmother, Catherine, died in 1885, and in 1890, his sister Grace, who had entreated him to return from his travels in the south in 1867, died at the age of 35 of paralysis. They are buried with Jacob in the same plot. Daughter Harriet "Hallie" (Byerly) Sweet and grand-daughter Catherine (Byerly) Chapline are buried in adjacent graves. Difficult as these deaths must have been for Davis, the next year brought a loss that must have been particularly hard for the photographer. Davis' eldest son, John Davis, died on November 29th, 1891 at the age of 19. The Frederick News' obituary column poetically titled "The Work of Death," began his obituary, "When death comes to the aged we look upon it as a visitation of the inevitable, but when it comes to one so young, so inestimable as a friend and companion, so thoughtful of the comfort and happiness of those about him, we feel to pang more keenly and sensibly.” A photo of John and his siblings, parents and extended family was taken shortly before his untimely passing. He would be buried in Area G/Lot 37.  My initial thought was “Who took this photo?” as all the professionals are within the shot. Interesting people of note here include J. Davis Byerly (Third Row extreme left with beard and moustache); Charles Byerly (Second Row extreme left); Mary Markell Byerly (second row to the immediate right of Charles); John Davis Byerly (Jr.) (second row extreme right); and Mary (Byerly) Chapline (front row, second from right in black and white dress and elbow on her grandfather George Markell’s knee). It can be assumed that John D. Byerly (Jr.) would have had a career in photography as well. His younger brother would play a greater role in assisting his father (Davis) throughout the 1890s leading to his eventual coronation by century’s end. In 1899, J. Davis Byerly retired from the photographic studio. He was 60 years old and had been running the studio for 30 years, surpassing his own father’s run of 27 years from 1842-1869. However, his retirement did not mean the end of the Byerly Picture Gallery, for like his father, Davis gave the business to his son Charles. Davis could now enjoy family and personal pursuits including his daughter Mary Catherine’s wedding that same year of 1899. She married Thomas Chapline, the son of a successful merchant family. J. Davis Byerly continued to be active in the community, in his church, the Republican Party, and his social club, the Order of Red Men. Just as his father before him, Davis was one of the most prominent men in Frederick, and was well liked and respected by the entire community. Charles married Regina Eisenhauer in 1903 and had two sons—(the previously mentioned ) John Francis Byerly (1904-1981) and Charles Byerly Jr. (1907-1983). He carried on the family business and continued the peerless brand that Frederick had come to expect. The Byerly Gallery was among the most prominent in western Maryland. Heritage Frederick has the works below by Charles Byerly in their extensive collection. The Black gentleman (lower right) is thought to be William Grinage, a former assistant of Charles Byerly and artist responsible for a portrait of Francis Scott Key that hung in the lobby of the FSK Hotel for several decades. We are very fortunate to have several images of Mount Olivet thanks to the lens of Charles Byerly. One such picture was taken of his brother John’s grave (at the photographer’s future burial spot) in Area G/Lot 37. This was taken in 1905. Charles took other images of Mount Olivet in the first decade of the 1900s, and we have several prints from the original glass negatives. I have incorporated one of these as the header, and logo, for this blog. J. Davis Byerly passed in 1914, February 19th to be exact, just one day following his 75th birthday. Wife Mary “Mame” (Markell) Byerly would die eight years later. Charles had shared his parent’s house on West Patrick until moving to 201 East Second Street in 1923 following his mother’s death. He continued running the family business up through 1915, at which time a terrible event beset the Byerly Studio. In spring of that year, the building was undergoing a major restoration. A month later, on April 14th, workmen hurriedly dashed for their lives as the front façade and floors of the building at 29 North Market Street collapsed. On the first floor of this building was located Dutrow’s Soda Fountain. Fortunately, patrons were not frequenting either business due to the construction work. No injuries were reported to the contracting crew, but Charles Byerly faced a total loss and the destruction of his 3rd floor studio with all its equipment and props. This event would promptly ended the business after a 73 year run. Many sources say that Charles would never pursue photography as a commercial venture again, but the census records of 1920, 1930, and 1940 continue to list his occupation as that of photographer. Perhaps it became a part-time or free-lance venture, instead? All the while, cameras were becoming more portable over time. Regardless, I can’t imagine a man surrounded by photography his entire life, would stop taking pictures. The 1940 US Census shows Charles’ sons and grandchildren living in the family home on Frederick’s East 2nd Street with their parents. John worked as a schoolteacher, and Charles as a gift shop manager who specialized in selling chinaware. Both appear to be single at time, however grandchildren are present. Like his father before him, Charles Byerly, Sr. kept busy with civic affairs. He would die on December 11th, 1944 and is buried directly behind his parent’s gravesite, and diagonally within a few yards of his older brother, whom he had photographed 39 years earlier. Charles, his father (J. Davis) and grandfather (Jacob) likely did not imagine the great importance of their work in their own lifetimes, as it was art, yes, but moreso a means to make an honest living. As mentioned earlier, it was also demanding work that took creativity, technical skill, patience and a toll on the respiratory system in working with all those chemicals.

I certainly can’t speak for all local historians, genealogists, and family historians, but what a tremendous legacy and gift the Byerlys have given all of us—worth billions of words, if the old adage is true about a picture’s worth?

1 Comment

Lisa Abbott

3/6/2023 12:39:29 pm

I really enjoy reading the “Stories in Stone” articles as each is published. I have lived in Frederick for almost 10 years now and love learning a lot of the local history. Thank you so much for sharing it with those of us who find it extremely enjoyable. Is there a way of getting copies of some of these articles? I would especially like to have a copy of the Byerly article.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed