|

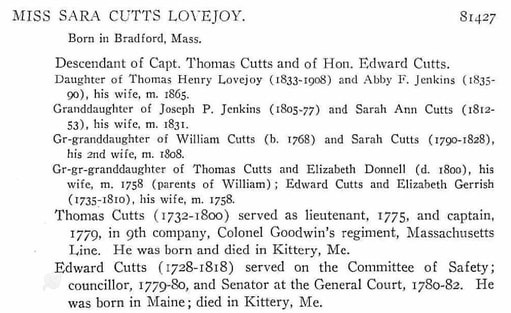

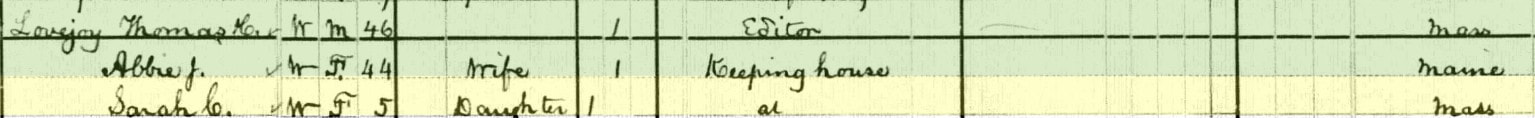

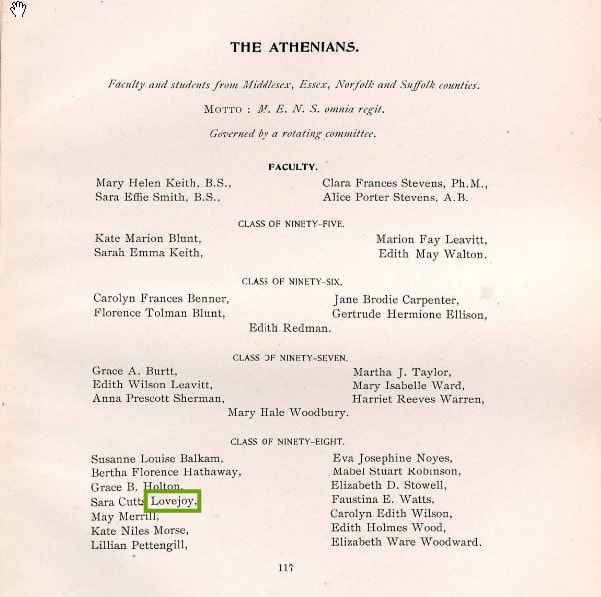

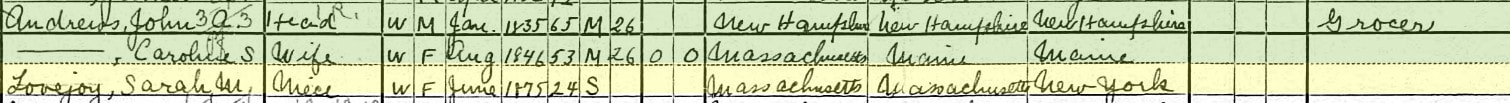

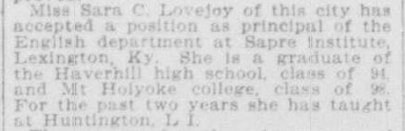

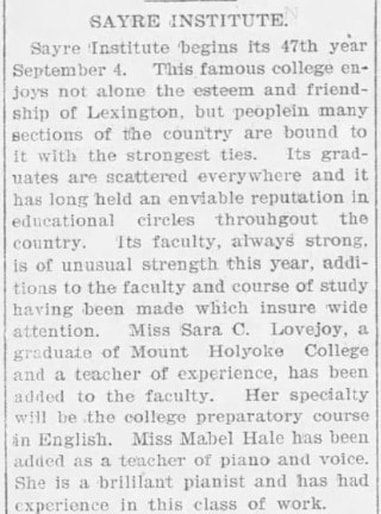

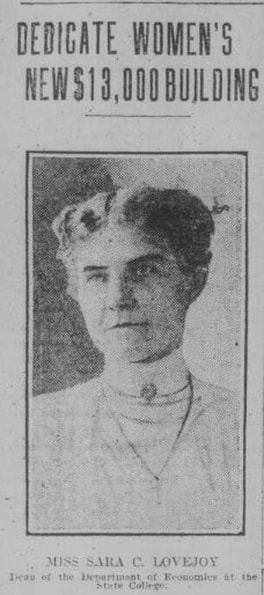

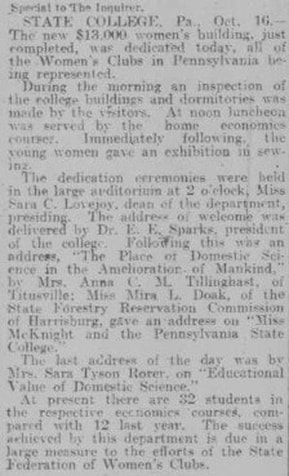

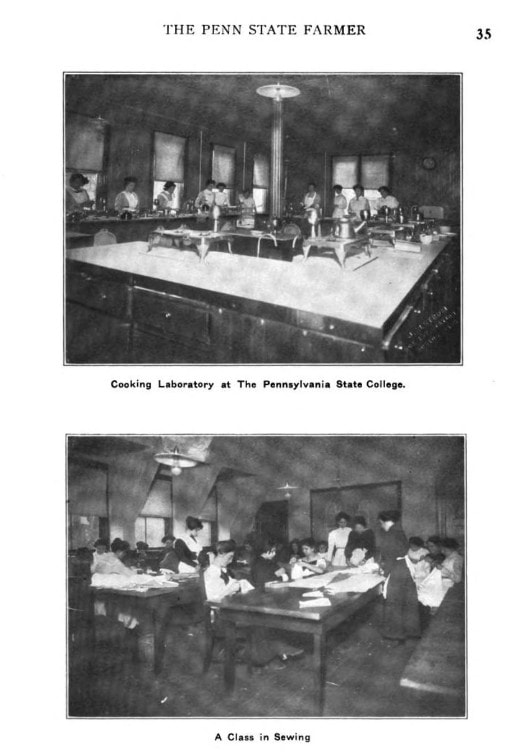

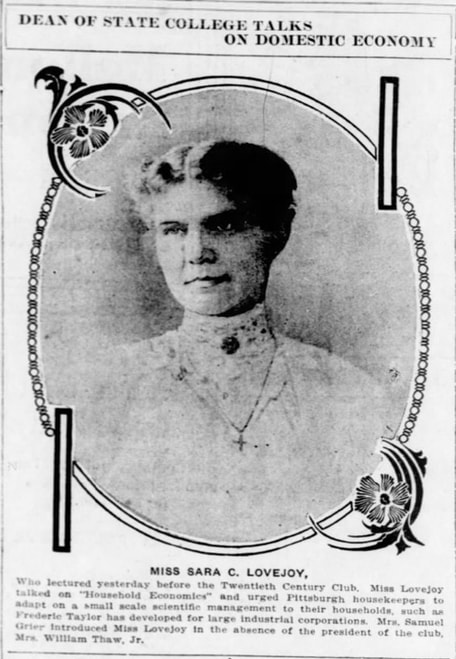

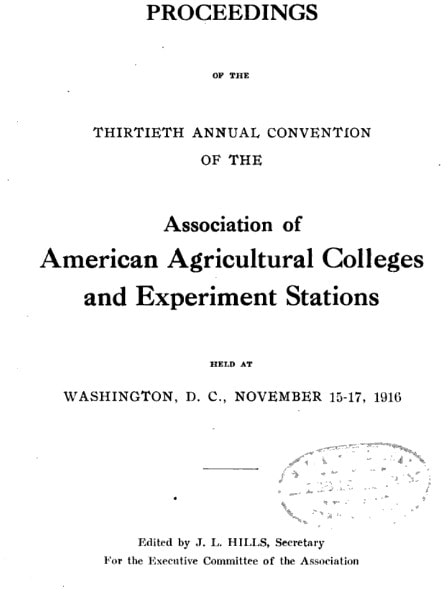

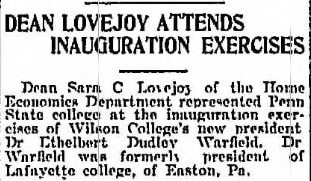

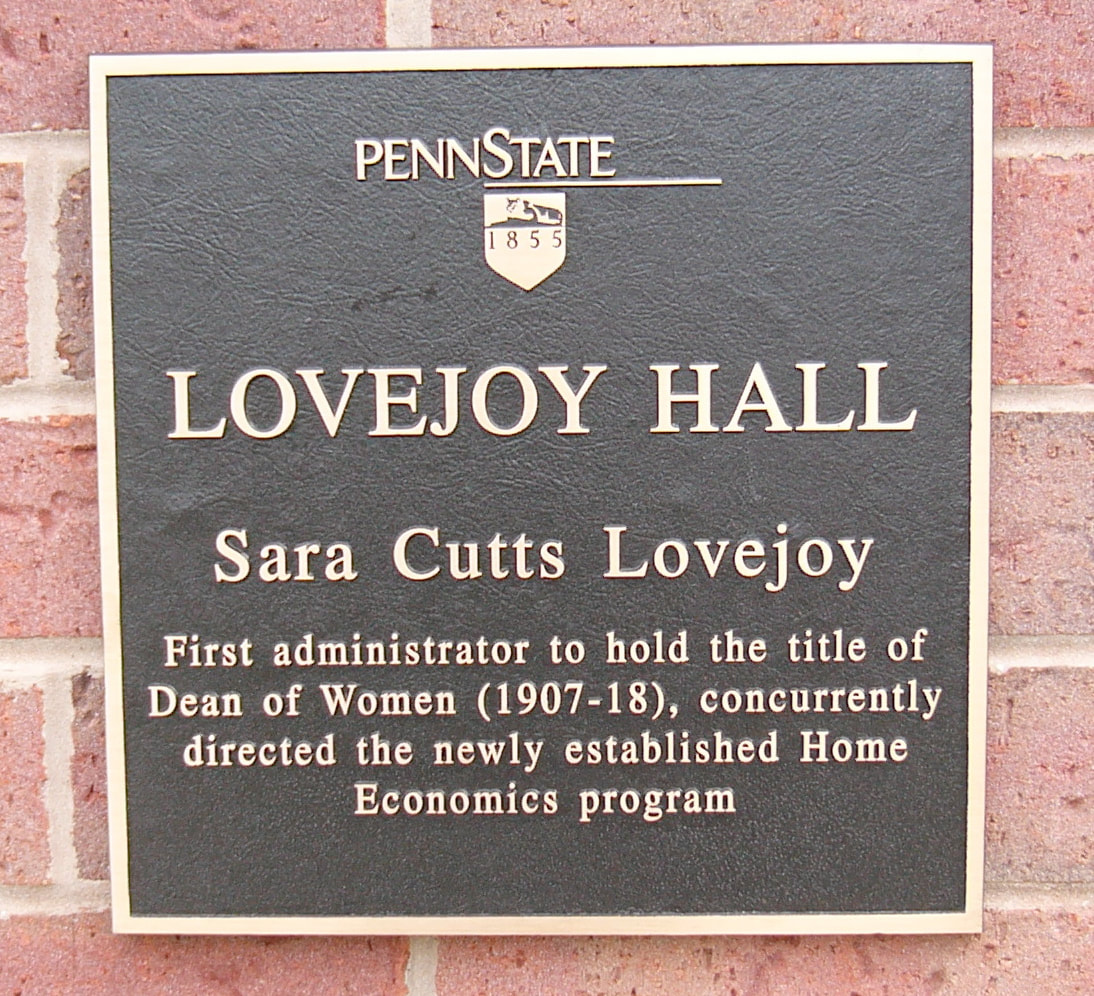

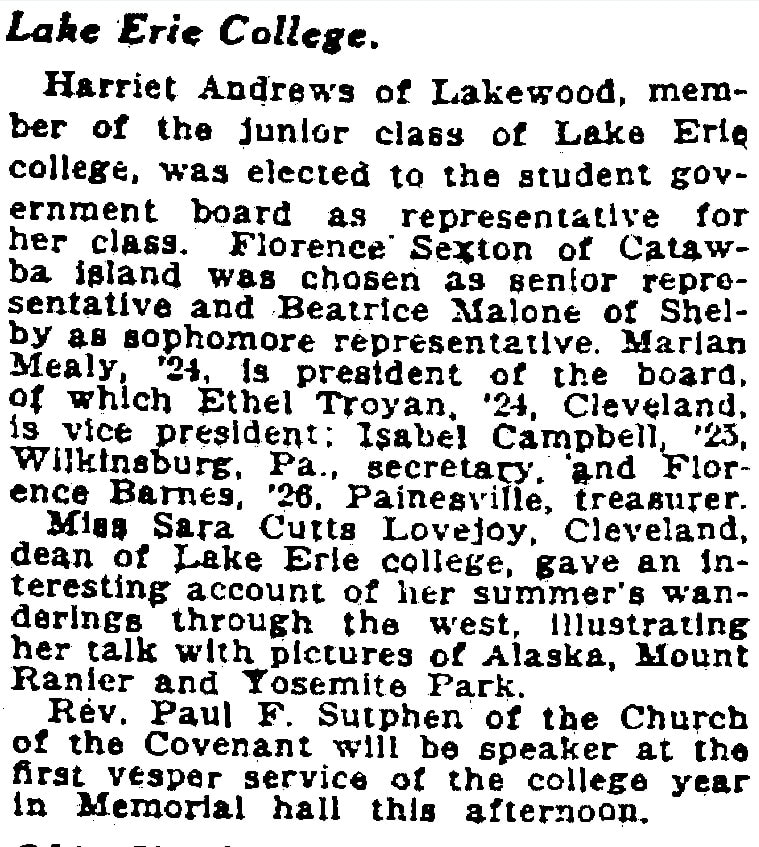

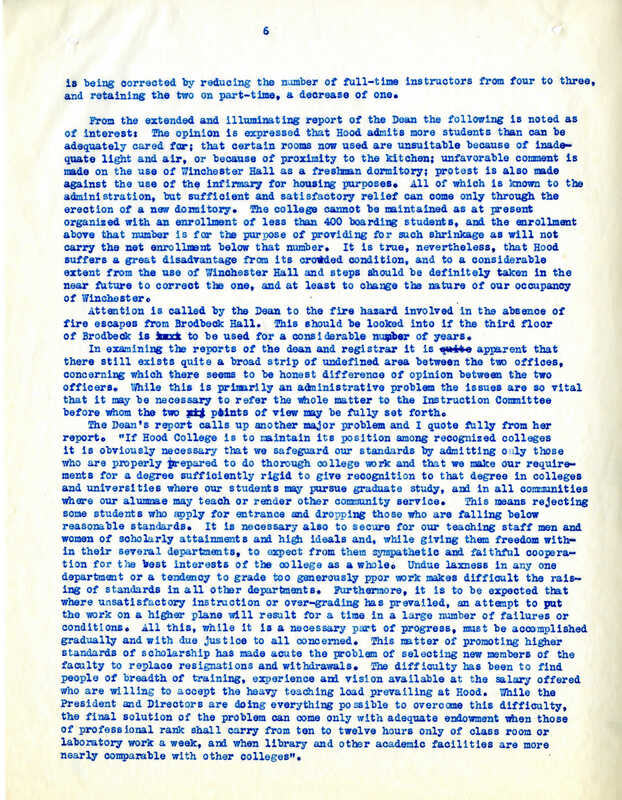

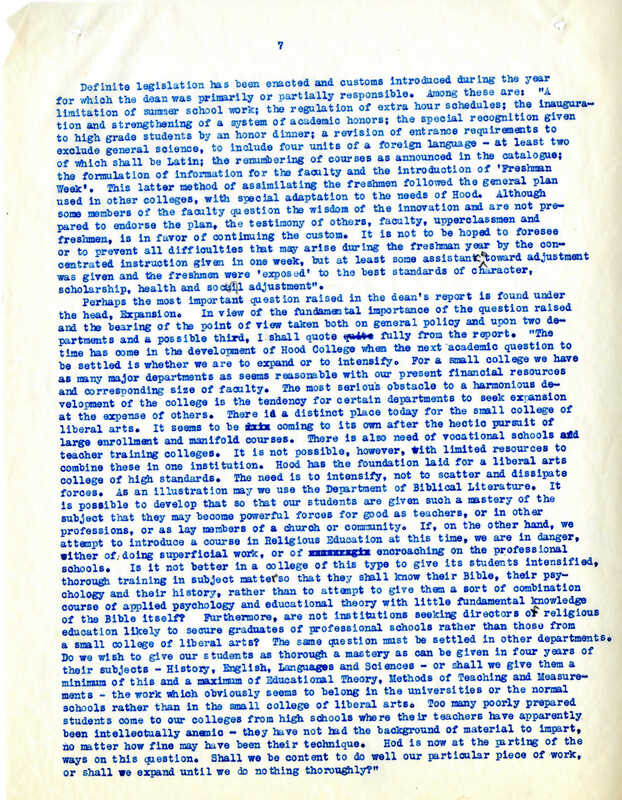

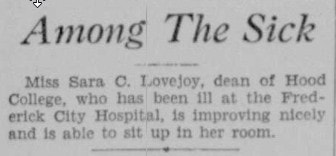

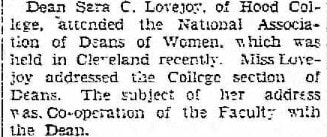

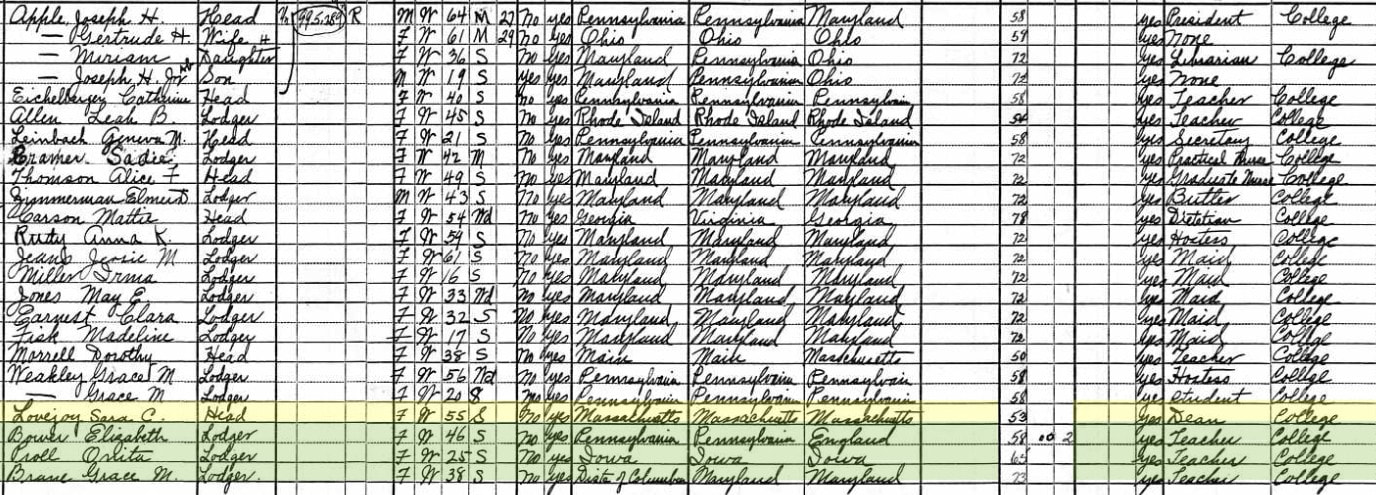

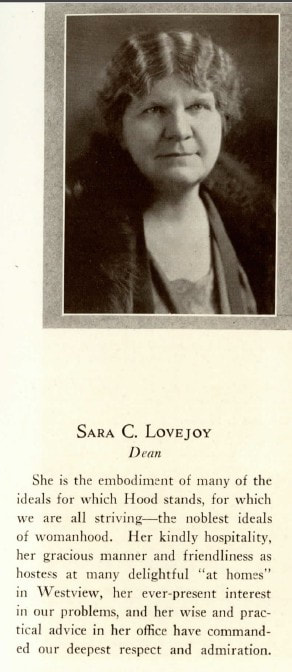

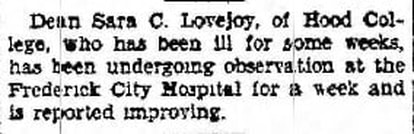

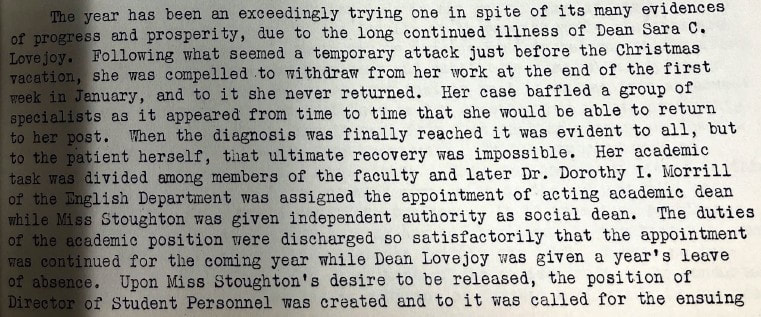

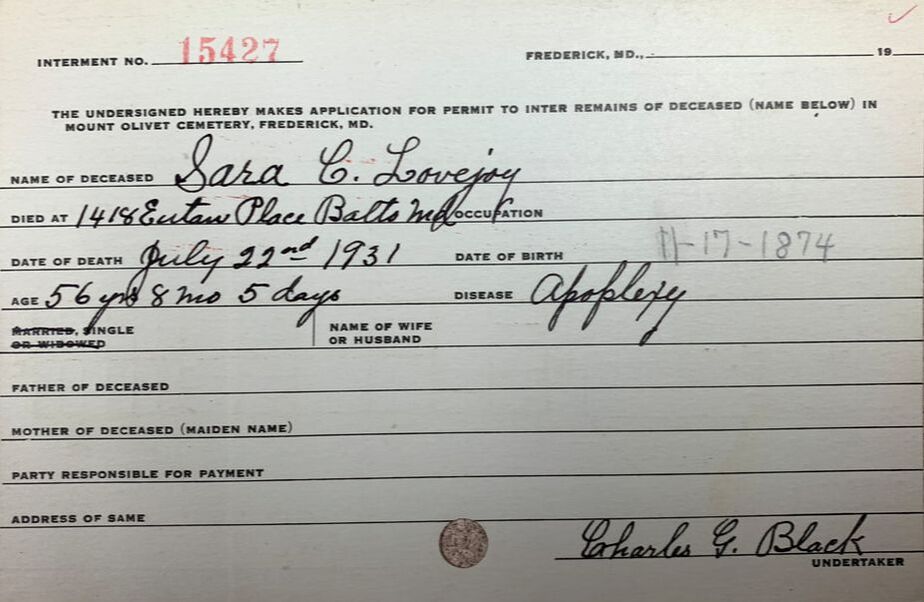

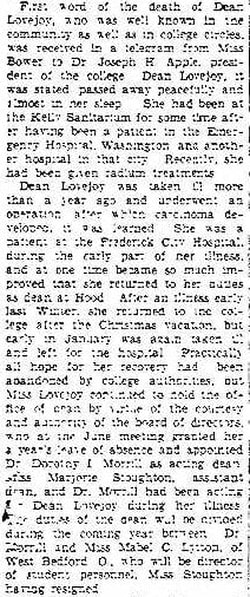

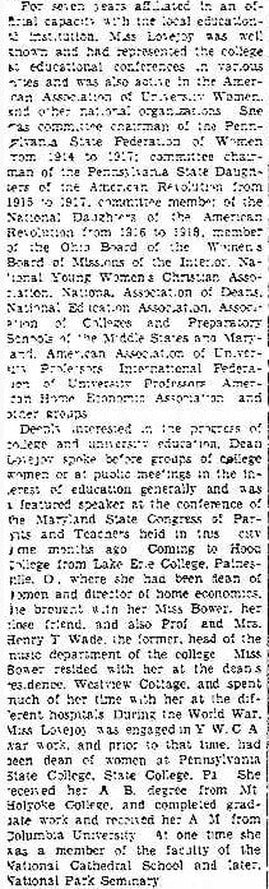

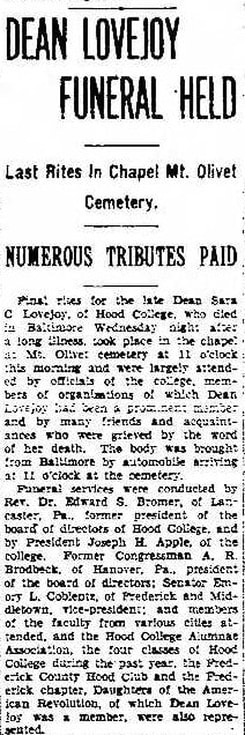

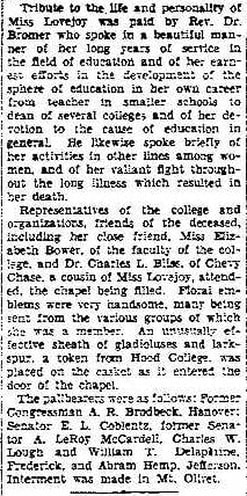

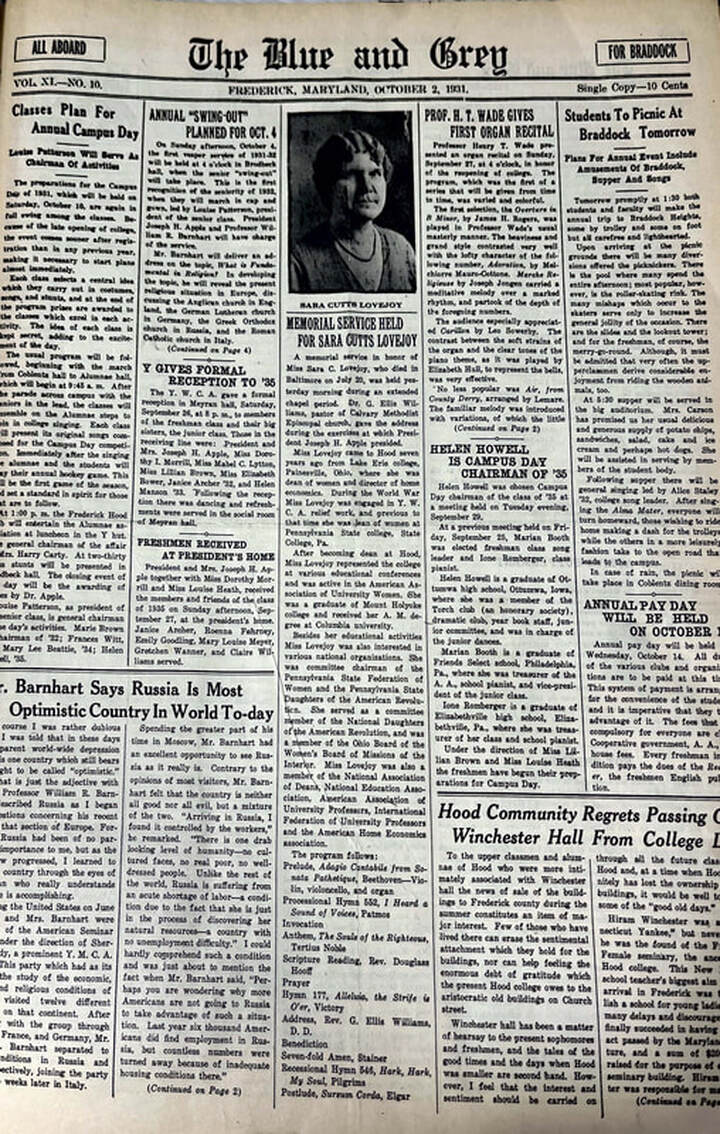

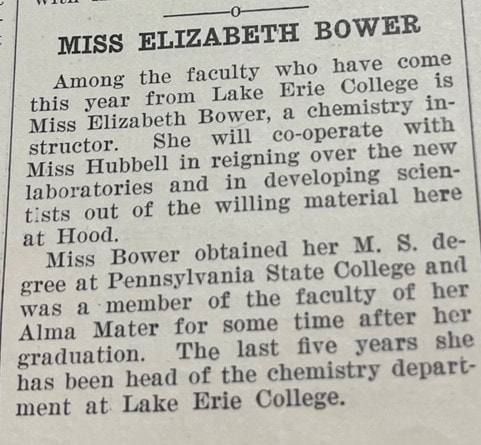

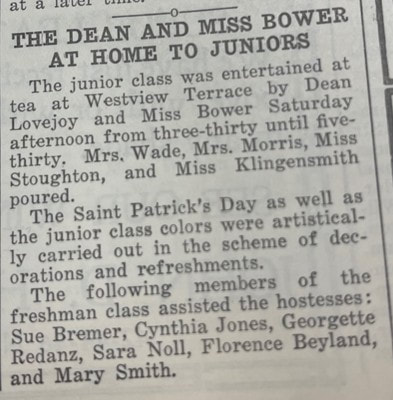

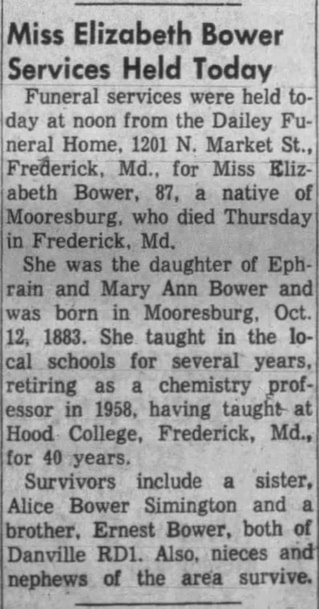

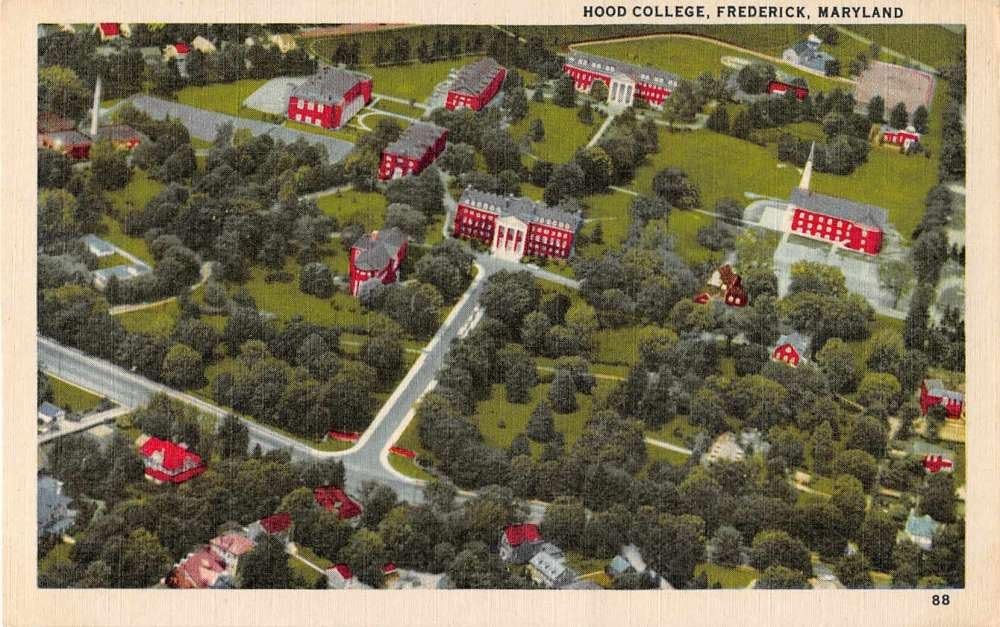

Love is certainly in the air as Valentines Day is coming up once again. We’ve featured “Stories in Stones” in the past exploiting this romantic holiday theme. One of my favorites included a 2022 inventory of people named “Valentine” and entitled “Mount Olivet Valentines,” while another was about a "love quadrangle" in the early 20th century called “Maryland’s Prettiest Girl stars in Too Many Valentines.” So, I thought I’d try my hand again at playing up the Valentines Day theme. Now all I needed was a willing participant from our cemetery population of 41,000 to write about. I consulted my trusted assistant Marilyn Veek, and we sat down at our computer database and starting looking at names that have possible connections to Valentines Day and what it represents, not simply a vital date that includes February 14th. We began looking for names such as “Rose,” of which we have 16 individuals by that name here in Mount Olivet. Next, we searched “Flowers” in which we have two. This was followed by two strikeouts with "Candy" and "Chocolate." The late comedian John Candy proves that the former last name is indeed a real thing, while, low and behold, I learned that Chocolat is actually a surname that can be found in Argentina and the Congo according to the website: www.Forebears.io and is the 4,532,898th most common surname in the world. Nothing was truly captivating us, so we looked up the name "Heart." There were no entries of decedents having that name, however, we hit the motherlode by tweaking the spelling to “Hart.” Here is a rundown of those with “Hart” as a surname and the number of interments in Mount Olivet: I still wasn’t feeling it. I needed a name that conveyed the essence of Valentine’s Day—the unbridled “joy of love.” That’s when Marilyn suggested we look to see if we have anyone by the name of "Love" in our cemetery. We soon discovered four folks with the name of “Love,” and four others whose surname had the root of “Love.” These latter examples include: an infant Elizabeth Loveder (1834), Allene I. Lovelace (1908-1979), and Susan R. Loveless (1950-2001) and one more, which would be our overwhelming choice to research. Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to introduce you to Sara C. Lovejoy—a sweet and sugary surname that says it all! I’m well aware of the term “killjoy,” and this is its polar opposite or antithesis. As for our proposed subject, I would quickly learn that she was a career educator who served as the Dean of Students for Hood College during the second half of the “Roaring 20s” up through her premature death in 1931. Sara C. Lovejoy Sara Cutts Lovejoy was born November 17th, 1874 in 1910 in Bradford, Essex County, Massachusetts. She was the daughter of Thomas H. Lovejoy (1833-1908) and wife Abigail F. Jenkins (1835-1890). Her father worked as an editor and Sara came from a family with deep roots going back to the Revolutionary War and early Massachusetts and Maine on her mother's side. She was named for her maternal grandmother. Sara experienced childhood in Haverhill, Massachusetts and grew up in a “learned” household, gaining a fine, early primary education. She attended college in Hadley, Massachusetts at Mount Holyoke, and would be a graduate of the Class of 1898. In the summer of 1900, Sara can be found living with an uncle and aunt (John and Caroline Andrews) in Newton City, Massachusetts. She had just performed two years of instructional teaching in Huntington, Long Island while earning her masters from Columbia University in New York City. Miss Lovejoy received her first administrative position at this time, which would call for a move to Kentucky. I found that the spelling of the school’s name was off in the first article I had found, as it should read the Sayre Institute in Lexington, Kentucky. This school was founded in 1854 by David Austin Sayre for the education of young women. Sayre believed that women deserved an “education of the widest range and highest order.” Originally named Transylvania Female Institute, the school was renamed in honor of Sayre in 1885. The school’s original curriculum included French, Latin, German language and literature, and vocal and instrumental music, which were typical courses of study for women in that era. But, true to Sayre’s educational philosophy, other classes offered by the school included algebra, geometry, trigonometry, geology, chemistry, astronomy, history, English literature, and philosophy. These courses were somewhat of a departure from the traditional female academies which primarily focused on music and languages. The institution still exists today and is known as the Sayre School. Sara C. Lovejoy served here until 1906, at which time she moved to State College, Pennsylvania to take the job as Director of the Household/Home Economics Department. While here at Pennsylvania State College (aka Penn State), she would be named Acting Dean of the school's Woman’s Department. In 1908, Miss Lovejoy was promoted to Dean of Women. I had my memory refreshed by reading about Home Economics and wondered, to myself, why this class isn’t taught today in public schools as was the case in my youth? I soon came across an article Sara had written for the February, 1912 edition of an agricultural journal published by the school and called The Penn State Farmer. I think I have a good handle on the job duties associated with a school principal, and also those of a collegiate president. I thought it would be good to revisit the job duties of a college dean, and in particular, a “Dean of Women.” I consulted Wikipedia and here is what I found: “The dean of women at a college or university in the United States is the dean with responsibility for student affairs for female students. In early years, the position was also known by other names, including preceptress, lady principal, and adviser of women. Deans of women were widespread in American institutions of higher education from the 1890s to the 1960s, sometimes paired with a "Dean of Men", and usually reporting directly to the president of the institution. In the later 20th century, however, most Dean of Women positions were merged into the position of dean of students. The Dean of Women position had its origins in the anxiety of the first generations of administrators of coeducational universities, who had themselves been educated in male-only schools, with the realities of coeducation. The earliest precursor was the position of matron, a woman charged with overseeing a female dormitory in the early years of coeducation in the 1870s and 1880s. As the number of women in higher education rose dramatically in the late 19th century, a more comprehensive administrative response was called for. The Deans of Women served both to maintain a protective separation between the male and female student populations and to ensure that the academic offerings for women and academic work done by women were kept at a sufficiently high standard. In the initial years, the responsibilities of the dean of women were not standardized, but in the early 20th century it quickly took on the trappings of a profession. The first professional conference of deans and advisers of women was held in 1903. In 1915, the first book dedicated to the profession was published, Lois Rosenberry's The Dean of Women. In 1916, the National Association of Deans of Women was formed at Teachers College. By 1925, there were at least 302 deans of women at American colleges and universities.” This background on the title speaks volumes, and demonstrates that Sara C. Lovejoy was not just one of many women to serve in this role within the educational profession, but was a pioneer and trailblazer. This woman destined to be the very first “Blazer” Dean to serve at our local Hood College helped shape and mold this position, and attended the National Association of Educators Conference in New York City in early July, 1916 where a special session was held for Deans of Women. I also found that Sara had attended the 13th Annual Convention of the Association of American Agricultural Colleges and Experiment Stations, held in Washington, DC in November of 1916. She was quite an ambassador for her employers. One more find of mine in conducting Google searches on Dean Lovejoy showed that our subject was a stickler for holding students to a high standard as she is quoted as saying that too many female students "show a lack of previous training that hinders their rapid progress." Sara C. Lovejoy is remembered on the Penn State campus by having a dorm, Lovejoy Hall, named in her honor. It provides on campus hous ing for graduate students. By 1919, Sara found herself in the position of Dean of Women at Lake Erie College in Painesville, Ohio. Over her five years here, she continued her shaping of young women’s minds and I found a clipping where she spoke on the benefits of recreation for females as exemplified by the Y.W.C.A. (Young Women’s Christian Association). Miss Lovejoy would make her way to Frederick, Maryland in 1924 as she would be appointed to the position of "Academic Dean" and "Dean of Women" for Hood College. She worked under Dr. Joseph Henry Apple, first president of the institution, and lived on the new campus which had only opened less than a decade earlier. In 1925, Sara would travel to Indianapolis to take part in the American Association University Women Conference bringing together some of the brightest women educators across the globe. She would go on to serve as president of Frederick’s local chapter of the AAUW from 1927-1929. To illustrate the experience and insight that Sara C. Lovejoy brought to Hood College, we can look at President Apple's yearly reports. Hood College archivist Mary Atwell shared with me a few pages from Dr. Apple's 1925 Annual Report on the College which shows that Dean Lovejoy was a force to be reckoned with, even in her first year on the job here in Frederick. The local newspapers are filled with mentions of Dean Lovejoy hosting school functions and events and presenting talks and lectures both here and abroad. She was certainly at the pinnacle of her career and had worked hard at her craft. However, I find it interesting that she never married or had children. An expert on teaching women how to properly conduct households, she would never quite be in that position herself. Instead, she worked in high-end academic positions. As this article is supposed to be about the “joy of love,” I presume that her career in education was the “love of her life,” without rival. In the summer of 1928, Miss Lovejoy spent the months abroad in Europe. She would return to Frederick and her duties in mid-September prior to the start of the fall semester but had to be hospitalized at Frederick City Hospital due to contraction of Typhoid Fever. She would make a recovery after a month’s hospitalization. By November, she would be performing her regular duties in earnest, including the hosting of the annual Thanksgiving banquet. In March of the following year, she traveled to Cleveland to participate in a Deans of Women conference. The 1930 US Census shows Sara C. Lovejoy living in Frederick on the Hood campus in a building once named Westview, which sat behind the President's original home. In the 1930 census, Dean Lovejoy is residing here with three other women teachers: Elizabeth Bower, Onita Prall and Grace Brane. The only building on the Hood College campus named for a faculty member is the Onica Prall Child Development Laboratory. This is the former Westview. Built in 1921 by the College’s workmen, it was a residence for the vice president, Charles Wehler. The building was renovated as a child development laboratory school after Miss Prall’s arrival at Hood and was further renovated in 1966. Miss Prall’s life was devoted to improving the quality of early childhood education and in 1971 the building was named in honor of her pioneering work. (Today this is shown on the current Hood map as Georgetown Hill Lab School). For the next few years, Dean Lovejoy continued with performing her regular duties until she became ill again in January, 1931 after her return from Christmas break. There would be no full recovery this time as Sara was suffering from cancer. Dr. Apple and Sara's co-workers sadly saw that this was a dire situation and began making succession plans. Dr. Apple's Annual Report of 1931 shows his concern. Sara Cutts Lovejoy succumbed to her illness six months later on July 22nd, 1931 in Baltimore. Her death certificate states that she died of apoplexy at the Kelly Clinic, a private hospital operated by noted physician Dr. Howard A. Kelly (1858-1943) at 1418 Eutaw Place in Baltimore. Dr. Kelly was one of the founding “Big 4” professors of Johns Hopkins University and is credited with establishing gynecology as a specialty by developing new surgical approaches to gynecological diseases and pathological research. Miss Lovejoy’s funeral service was held in our Key Chapel here at Mount Olivet with services conducted by Dr. Joseph Henry Apple, himself. Her body would be laid to rest in Area LL/Lot 132. A special memorial service for Dean Lovejoy would be held at Hood a few months later when school was back in session. This would be for the benefit of the students who had been on summer break at the time of her death. I found it interesting that Sara would be buried here in Frederick, a place she had only lived for barely seven years. Her half grave plot contains six spaces but only one other individual is buried here. This woman’s name is Elizabeth Bower, and she died in November of 1970. In looking a bit closer, I learned that Miss Bower had a very special relationship with Dean Lovejoy. At the very least, she was a teaching colleague, housemate, and “close friend.” She is even listed as such in Miss Lovejoy’s obituary. I also found that Elizabeth Bower would serve in the role of Sara C. Lovejoy’s Executrix, and it seems she assumed much of Miss Lovejoy’s estate including the grave plot here at Mount Olivet. Miss Elizabeth Bertha Bower was born on October 12th, 1883 in Mooresburg, Montour County, Pennsylvania. She was the daughter of a Union Civil War soldier and had attended Pennsylvania State College where she would receive her Bachelor of Sciences degree in 1909, and her Masters in 1912. She most definitely met Miss Lovejoy at the college while the latter was serving as Dean of Women. Elizabeth Bower was a professor of chemistry, and from what I’ve read, was called for by Miss Lovejoy to take a position at Hood in 1925. I went back and searched the ship log of the SS Minnekahda which sailed from London to New York in August of 1928. This was the ill-fated journey that would precede Sara’s bout with Typhoid fever. Low and behold, I found Miss Bower as Sara’s travel companion to Europe. Whatever the relationship these two women had, and considering neither married, I take heart in knowing that they were the closest things to Valentines for each other, and hopefully found joy in their close friendship on many "February 14ths" up to Dean Lovejoy’s last in early 1931. Miss Bower stayed in Hood College’s employ until her retirement in 1958. Miss Bower’s legacy lives on at the college through the Elizabeth B. Bower Prize, awarded annually to an outstanding student in chemistry. The prize was established in 1956 by the late Rebecca Ann Eversole Parker '55, who was inspired by Professor Bower to make chemistry her career. At the time of her untimely death, Rebecca was studying for her doctorate in chemistry at Oxford University. In 1962, the Eversole family endowed the prize as a memorial to Rebecca. Elizabeth Bower kept herself busy in retirement by traveling and taking part in various civic groups. She gave many presentations as historian for the local Daughters of the American Revolution chapter. Elizabeth Bertha Bowers died in November 1970, and at that time was placed in the gravesite next to her old friend Sara who had preceded her in death nearly forty years earlier. A woman by the name of Beatrice Malone of Lutherville, MD took care of Elizabeth's burial plans and was the Personal Representative for her estate. She was a student of Dean Lovejoy at Lake Erie College and again in the Hood class of 1926. She would become a supervisor for the Children's Aid Society of Maryland. Sara C. Lovejoy and Elizabeth Bower helped build the great tradition of Hood College, one that continues on. Think of them with both love and joy as you cherish loved ones, past and present, this coming Valentine’s Day. AUTHOR'S NOTE: Very special thanks to Mary Atwell, Archivist and Collections Department Librarian at Hood College, for her assistance with visuals and additional information for this story.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed