|

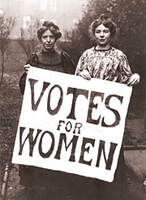

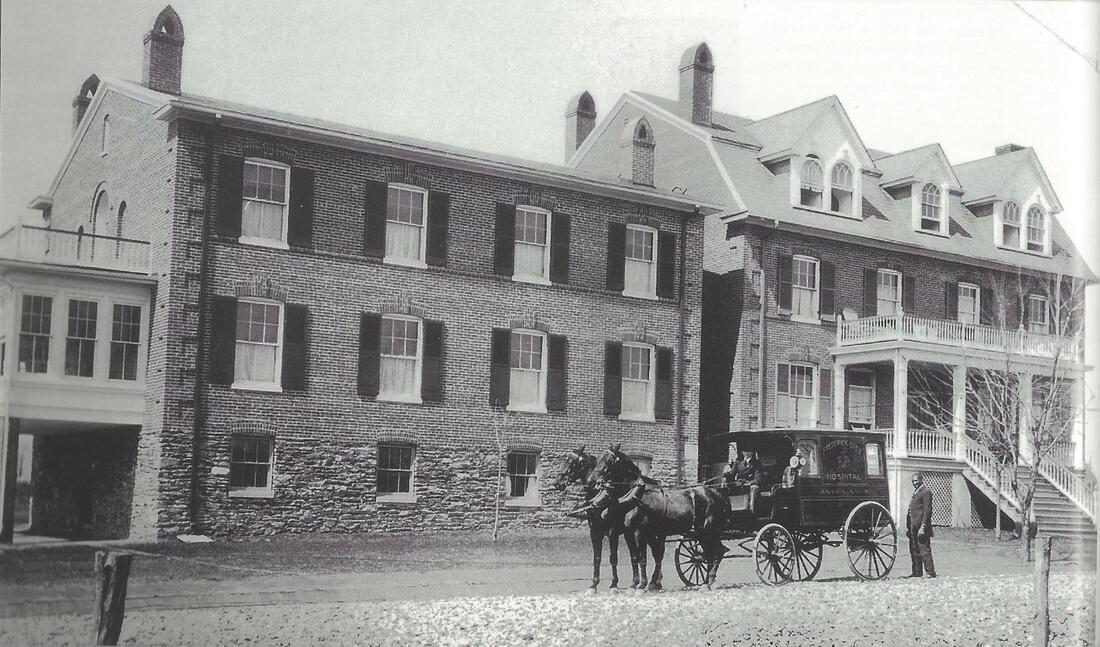

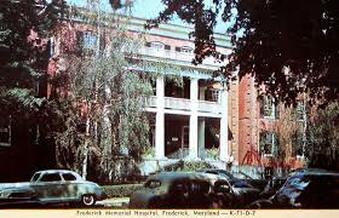

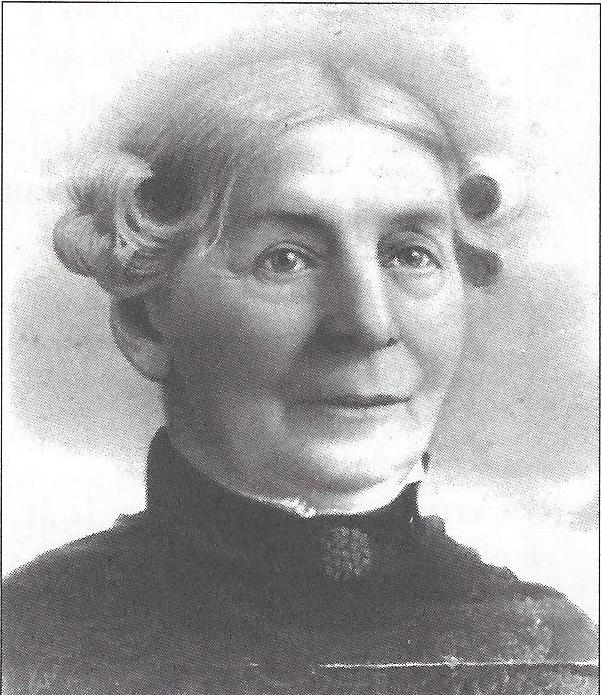

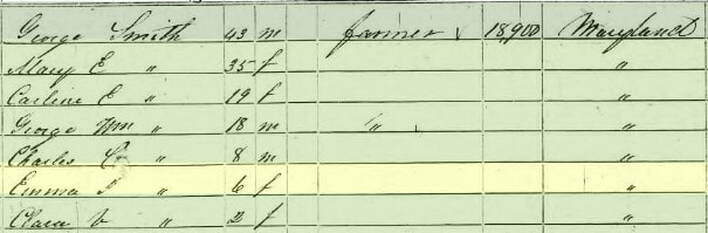

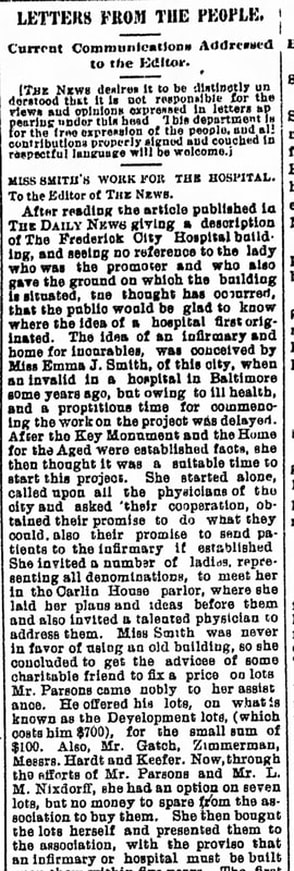

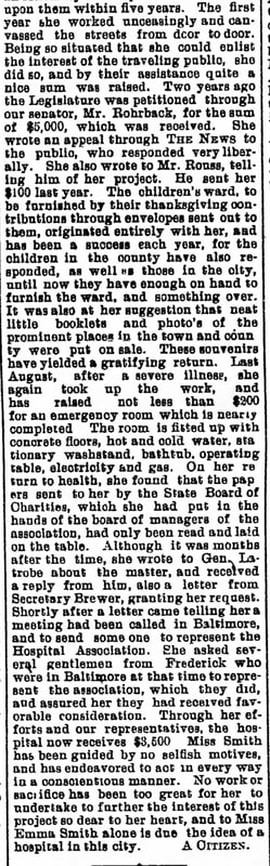

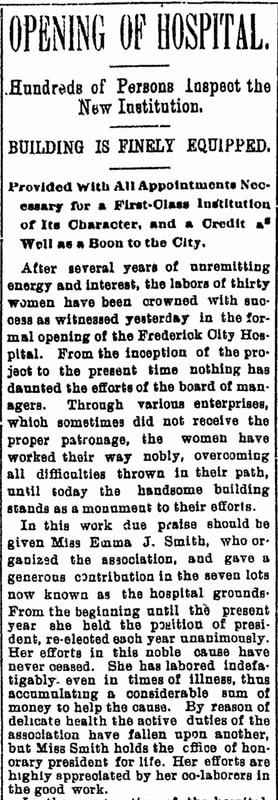

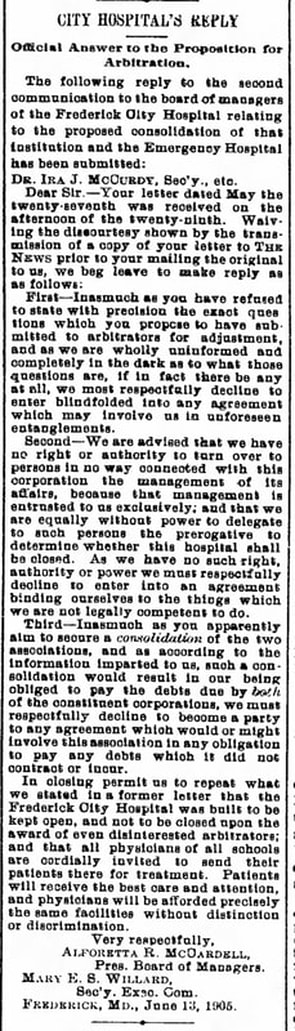

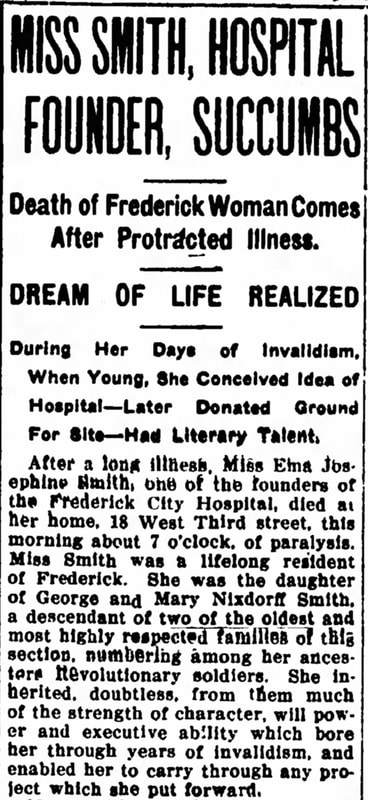

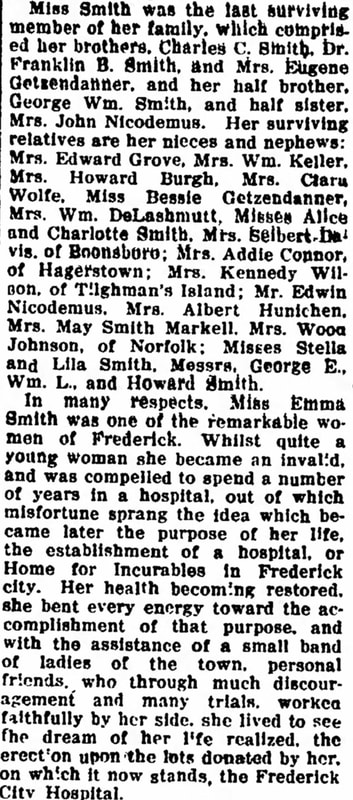

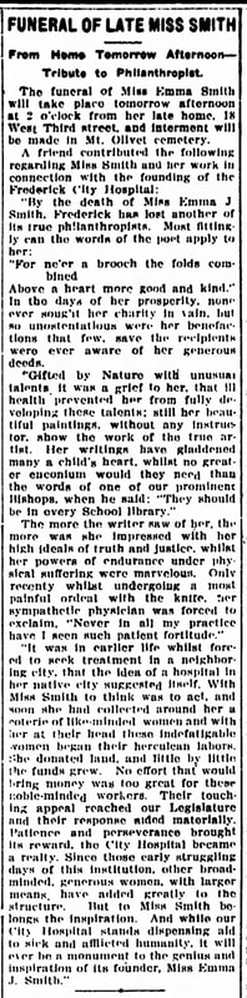

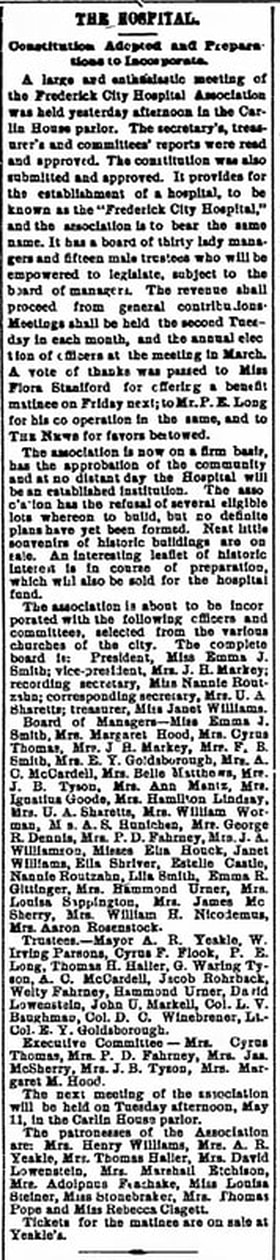

As we recently recognized Martin Luther King Day this year on January 21st, many were reminded that this holiday serves as a humble memorial to an extraordinary human being who dedicated his life to the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. King brought hope and healing to the America, and the memory of his sacrifice and tireless work continues to hold true for young and old. This same date of the 21st of January also is significant as the birthday of a Frederick woman who dedicated her later life for the literal construct of “hope and healing." In the 1890's, she would voice the importance of both (hope and healing) in our community's need for a healthcare facility in her hometown. Her name was Emma Josephine Smith, a tremendous leader in her own right, who spent the entirety of her 72 and-a-half years unable to vote, and oftentimes was viewed as an unequal to peers and colleagues. Emma was white, and came from an affluent family here in Frederick. Her father was an Orphan's Court judge, her brother a physician, and her half-brother was a well-known businessman credited with developing an inter-urban trolley system in 1896 known as the Hagerstown & Frederick Railway. Interestingly, Emma J. Smith is better known today (or should be) than all three of the above-mentioned immediate male family members for the impression she left on Frederick. While the county’s old “clanging” trolley line came and went, the innovation Emma helped bring to light is still in operation today, and ever-growing larger each year. In addition, this institution continues to serve as one of Frederick County's prime employers and has been a place that has given many a locals their start in life. For countless other fortunate residents, Emma’s creation has also been a true “life saver.” And then there are those that spent their last living days and hours here. We are of course talking about Frederick Memorial Hospital. Frederick Memorial started out under the name of Frederick City Hospital, a facility that grew considerably over a century. It began (and remains) at a location on the northwest outskirts of Frederick City on Montonqua Avenue, later to be named W. Seventh Street. For years, local residents have simply referred to this facility as FMH. Today, it is much larger in scope, and has expanded to a great extent over recent decades to keep up with the demands of a growing population. Today, “Frederick Memorial” is synonymous with the hospital on Seventh Street, yet the much larger Frederick Regional Health System (FRHS) includes the RoseHill facility and a dedicated cancer patient facility (off Opossumtown Pike), Hospice of Frederick County, Corporate Occupational Health Services and a myriad of other facilities featuring consultants, specialists and practitioners located throughout the area. While Emma could serve on a hospital board, and vote on early hospital matters, she would never in her lifetime have the right to vote for politicians, ranging from Frederick mayors to US presidents. Suffrage was the keystone of a larger women’s rights movement, a reform effort that evolved during the 19th century, but would not find its ultimate resolution until the 20th century. The women's movement initially emphasized a broad spectrum of goals before focusing solely on securing the franchise for women. Four years and five days after Emma J. Smith’s death, August 26th, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was finally ratified, enfranchising all American women and declaring for the first time that they, like men, deserved all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship.  Seneca Convention of 1848 Seneca Convention of 1848 Emma Josephine Smith and a group of “fellow” women worked hard to give Frederick its first public hospital structure. She was born on January 21st, 1844, four years before the famed Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman" and was held in Seneca Falls, New York (July 19-20, 1848). Here, some 300 women and men signed the Declaration of Sentiments, a plea for the end of discrimination against women in all spheres of society. Emma experienced the American Civil War while in her late teens. After the conflict, she would see the 14th Amendment passed by Congress in 1866 (ratified by the states in 1868), saying “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective members, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. . . .But when the right to vote . . .is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State . . . the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in proportion.” It is the first time that “citizens” and “voters” are defined as “male” in the Constitution.  Three years later in 1869, the first woman suffrage law in the US was passed in the territory of Wyoming. The following year, the 15th Amendment received final ratification, saying, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” By its text, women were not specifically excluded from the vote. Here are a few other highlights of the women’s movement over Emma’s lifetime, courtesy of the Virginia Commonwealth University’s Social Welfare History Project: *1870 The first sexually integrated grand jury hears cases in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The chief justice stops a motion to prohibit the integration of the jury, stating: “It seems to be eminently proper for women to sit upon Grand Juries, which will give them the best possible opportunities to aid in suppressing the dens of infamy which curse the country.” *1873 Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130 (1872): The U.S. Supreme Court rules that a state has the right to exclude a married woman (Myra Colby Bradwell) from practicing law. *1875 Minor v Happersett, 88 U.S. 162 (1875): The U.S. Supreme Court declares that despite the privileges and immunities clause, a state can prohibit a woman from voting. The court declares women as “persons,” but holds that they constitute a “special category of nonvoting citizens.” *1879 Through special Congressional legislation, Belva Lockwood becomes first woman admitted to try a case before the Supreme Court. *1890 The first state (Wyoming) grants women the right to vote in all elections. Emma’s privileged upbringing allowed her the advantage of travel. Her many sojourns brought the Frederick girl to towns and cities throughout the region and country. She noted how other places took proactive roles in securing healthcare facilities for their populations. The point was made even more personal when Miss Smith became incapacitated for a period of time in the late 1880’s due to illness. The episode made her an invalid, not being able to leave her current residence at the time of Frederick’s City Hotel, which once stood near the intersection of W. Patrick and Court streets. The Genesis of a Remarkable Lady Emma J. Smith never married. Her parents included the fore-mentioned George William Smith, Jr. (1807-1871) and Mary Ann Elizabeth Nixdorff (1815-1859), thus descending from some of Frederick's earliest settlers on both the Smith and Nixdorff sides. Emma's father was one of the founders of the Frederick County National Bank and served as a Judge of the Orphans Court. Mr. Smith is said to have "served with notable credit for many years as Judge of the Orphans' Court, in which capacity he displayed an ability and judgment that added materially to his repute. He was frequently called upon as a referee in the disputes that arose among his neighbors and it is worthy of mention in this connection that in many instances he proved an effective factor in the adjustment of such cases without the necessity of an appeal to the courts." Emma was one of nine children, only five of which would grow into maturity. She had two brothers (Charles Colvin Smith and Dr. Franklin Buchanon Smith) and two sisters (Mary Thomas Smith and Clara Virginia (Smith) Getzendanner), all of whom predeceased her. Emma had four additional half-siblings because her father had been married previously. One of these was the earlier mentioned George William Smith III (1832-1915) of trolley fame. Emma spent her early years on the family farm and received schooling. She attended the Evangelical Lutheran Church and had many friends. She learned business and political acumen from her father, and most likely, gained valuable medical knowledge from brother Dr. Franklin B. Smith (1856-1912), a local physician. Without kids to raise, the maiden lady had time, energy and money, to give. She busied herself with two fine projects in the mid-1890’s as a leading proponent and Charter Member of Frederick’s Home for the Aged on Record Street, and participated as a member of the Francis Scott Key Monument Association and was equally successful in helping Mount Olivet receive the grand memorial that greets visitors entering our S. Market Street entrance. From here, Emma set her sights on a new target.  The former Carlin Hotel (c. 1903) at the southeast corner of W. Church and N. Court streets The former Carlin Hotel (c. 1903) at the southeast corner of W. Church and N. Court streets In late 1896, and early 1897, Emma helped spearhead a series of meetings held at the Carlin House, a hotel once located at the southeast corner of W. Church and Court streets, today the parking lot for M&T Bank. The conversation centered on the need, and process to establish a hospital facility for Frederick. She was joined in these talks by a fine group of some of the leading women in town including Mrs. Ida N. Markey, Miss Nan E. Routzahn, Mrs. A. Gertrude Sharretts, and Miss Janet Williams. At another meeting held at the Carlin Hotel on March 26th, 1897, Miss Smith was elected president of the hospital venture. The four other women mentioned above rounded out the slate of elected officers for the inaugural board of directors. Unfortunately, Emma and the other ladies could not go further in forming a legitimate corporation. At this time, only men could perform this feat based on state law. Fourteen men were selected to accomplish this task and the Frederick City Hospital Association became a reality. The following year, a charter was received allowing the group to build a structure Meanwhile, Emma and a determined group of talented and resourceful women performed the arduous task of fundraising the fundraising. Many possible locations were discussed for the proposed hospital including Groff Park (future home of Hood College), the Groff Hotel lot atop W. 7th and Market streets which would become home to Frederick's first radio station), and the site of the old Stone Tavern at W. Patrick and Jefferson streets. Emma offered another option, donating seven acres of her own property, land positioned across from Park Avenue. This generous gift was duly accepted.  The original Frederick City Hospital as it looked in 1902 The original Frederick City Hospital as it looked in 1902 Emma and her lady Board of Managers worked earnestly to fund the hospital project. They went door-to-door, approached businesses and lobbied the state. In just five years, a new, "state of the art," two-story (and soon to be three-story) hospital building opened to the public. This was early May, 1902. The structure cost $8,000 to build, and featured 16 private rooms and would soon boast three wards. A school of nursing was also established in 1902 adjacent the Frederick City Hospital and named the Georgianna Simmons Nurses’ Home. Mrs. Simmons was the former Georgianna Houck (1832-1915) who contributed the bulk of the money needed to build this facility. Her gravesite is located in the same section of the cemetery as Emma and another major early benefactor of the hospital, Margaret S. Hood. Emma could not have been happier with making her dream a reality. Unfortunately though, there were many community medical professionals who were not. Trouble had been brewing for quite some time. Controversy soon followed between the new hospital and Frederick County Medical Society because the bulk of the doctors of town felt jilted that they had little to no say in the hospital's construction. Moreso, they were unwilling to take instruction from an all-female Board of Managers, headed by a woman administrator without medical training. Yes, they thought that these women were incapable of running a hospital. Another struggle with the Medical Society would ensue over a refusal by the Lady Board of Managers to hand over the hospital to allopathic (alternative medicine) physicians, a suggestion made by the Frederick County Homeopathic Physicians Society.

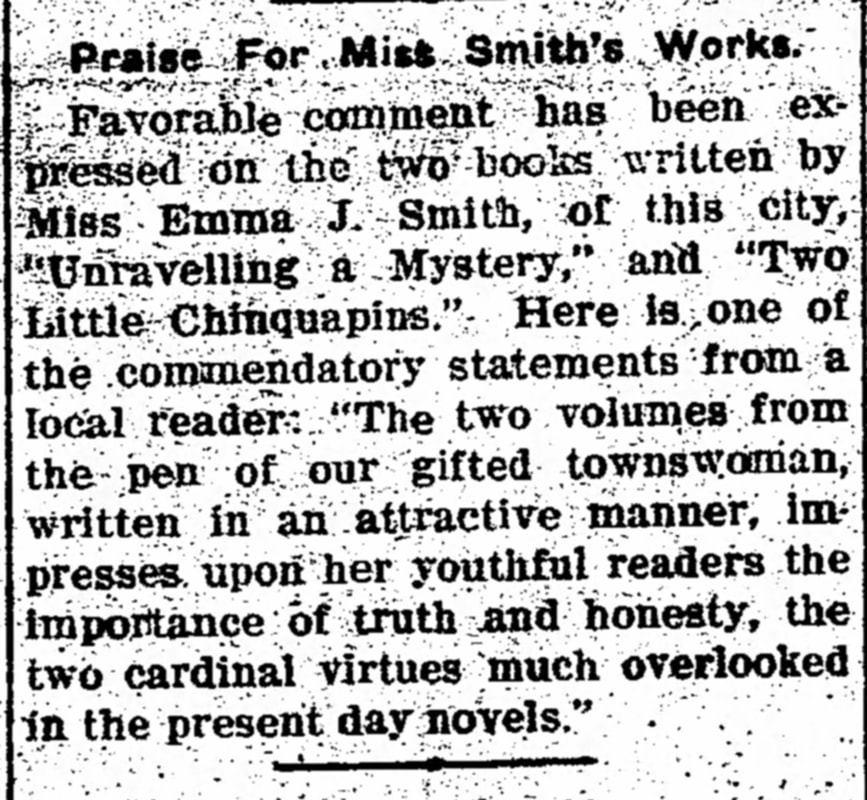

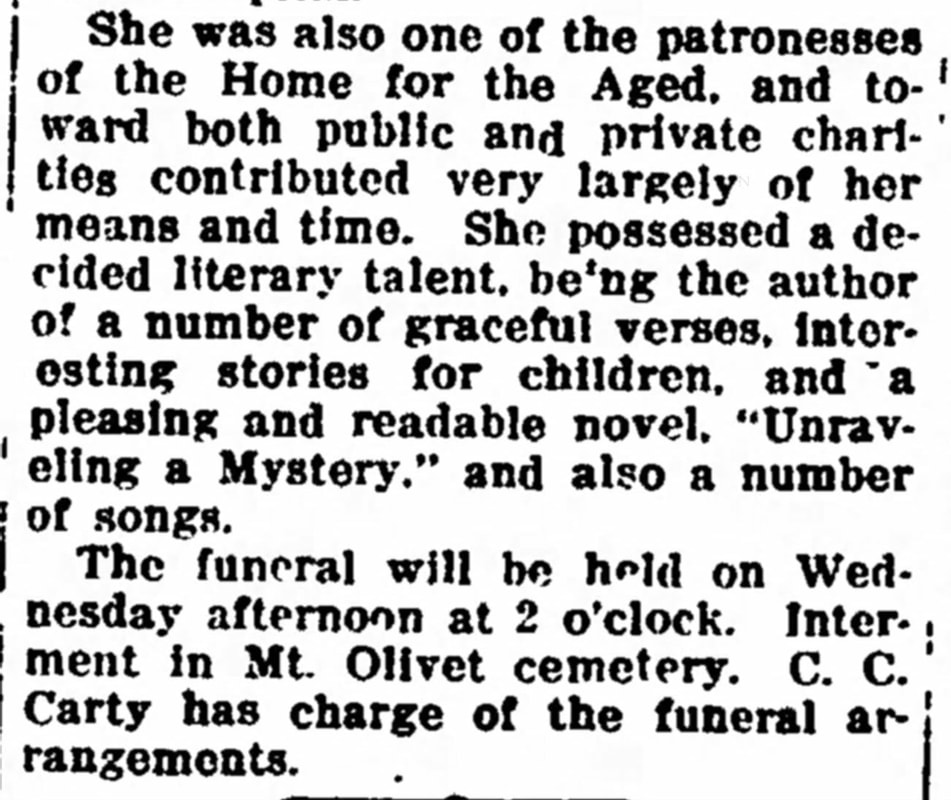

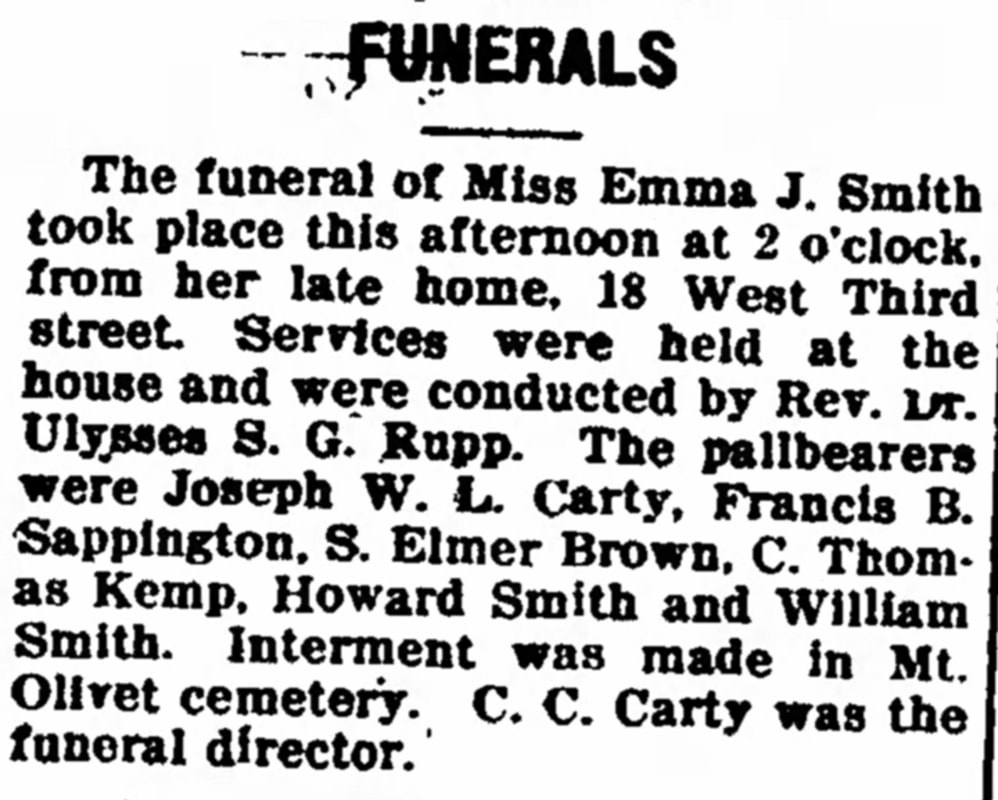

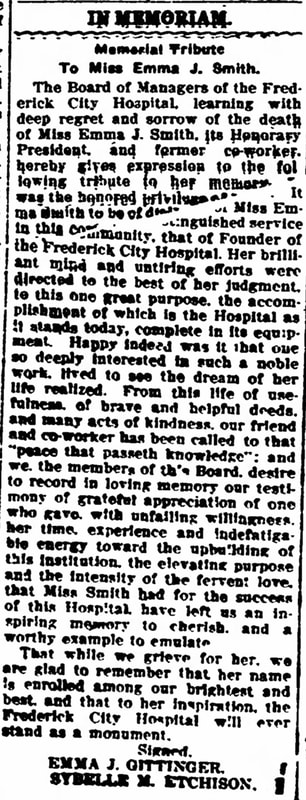

The Emergency Hospital closed its doors on October 31st, 1906 after a three-year stint. The doctors joined the Frederick City Hospital initiative and we have had one unified, community hospital ever since. This is certainly a testament to the tenacity of Miss Smith who would eventually step down from her position as president to take a lesser role in leadership due to health issues. She would now be given the title of Honorary President for Life of the Frederick City Hospital, one that was continuously upheld until her death. Emma spent her final decade of life continuing to give her energies to the hospital and the Record Street Home. She, herself, maintained a home at 18 W. Third Street, where she soon took to professional writing. In 1912, she published two novels, printed and distributed by Cosmopolitan Press of New York. These were entitled Unraveling a Mystery and a children’s book Two Little Chinquapin & Other Tales. Emma Josephine Smith died on August 21st, 1916 of a cerebral hemorrhage. Her obituary was given plenty of space in the local papers, one of which deemed her "one of the remarkable women of Frederick." She was buried under the shadow of a large monument erected in honor of her parents who had predeceased her. This is located in Mount Olivet’s Area E/Lot156). In the weeks to follow, several glowing tributes and memorials appeared in the newspapers.  Seven years after Emma’s death, the National Woman’s Party proposed the following Constitutional amendment in 1923: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and in every place subject to its jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” Things would not be firmly rooted until 41 years later in 1964, when Dr. King’s push for equality among races joined the women’s fight for equality with males. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act was passed, including a prohibition against employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. Miss Smith is still remembered by some in Frederick, and the hospital. Recently, Frederick Health honored Miss Smith by naming their westernmost entrance (off Seventh Street) Emma Smith Way. Thanks for the facility Miss Smith, Frederick couldn't live without it! *Bonus articles of note:

4 Comments

1/22/2019 07:48:59 pm

Thank you, this cleared up some confusion for us. My grandmother was Clara Virginia Getzendanner Wolfe, one of Miss Emma Smith’s nieces.

Reply

Jackie Dinterman

1/22/2019 09:51:49 pm

Hi Chris,

Reply

1/23/2019 12:07:06 pm

Hi Jackie,

Reply

Walter J. Wolfe

2/15/2019 01:59:09 pm

Thank you for your edifying article about my great aunt, Emma Josephine Smith, older sister to my great grandmother, Clara Virginia Smith-Getzendanner. Your article compliments a 1972 booklet I have about Emma Josephine Smith. By the way, my late father, Harry Howard Wolfe, always maintained that he was the first baby born at Frederick City Hospital [11/27/1903], but I have never been able to verify this. His mother, Clara Virginia Getzendanner - Wolfe, was the niece of Emma Josephine Smith.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed