|

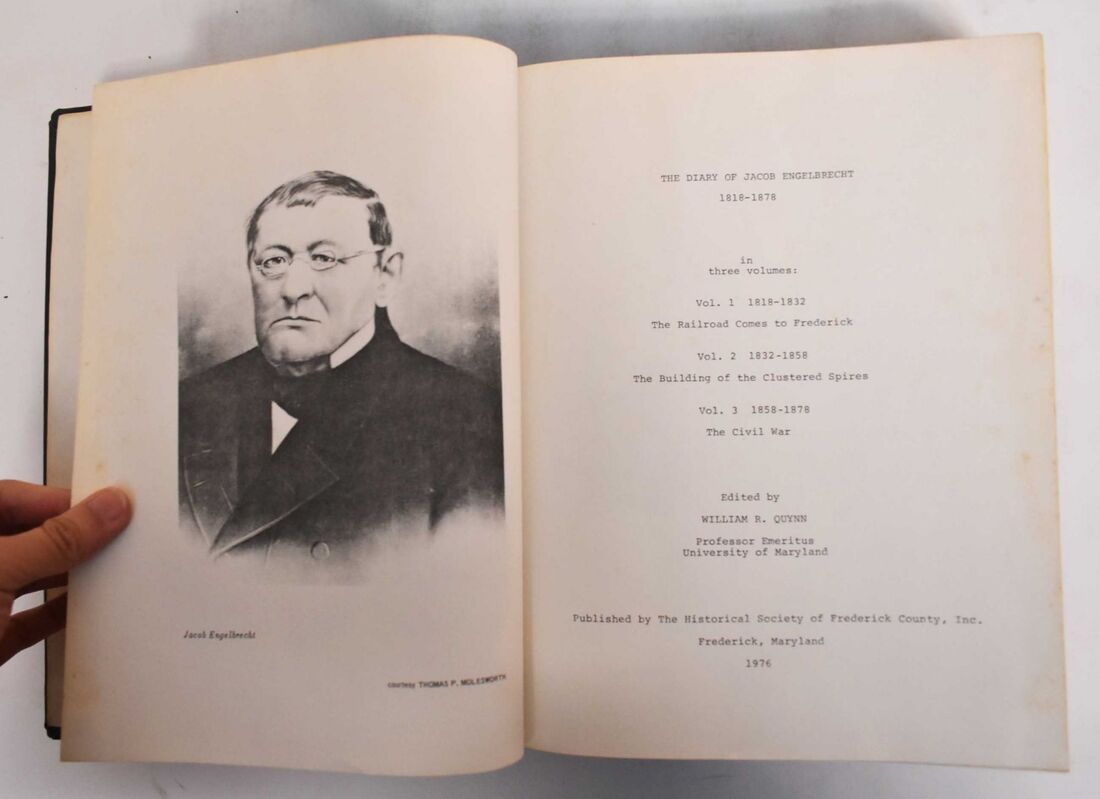

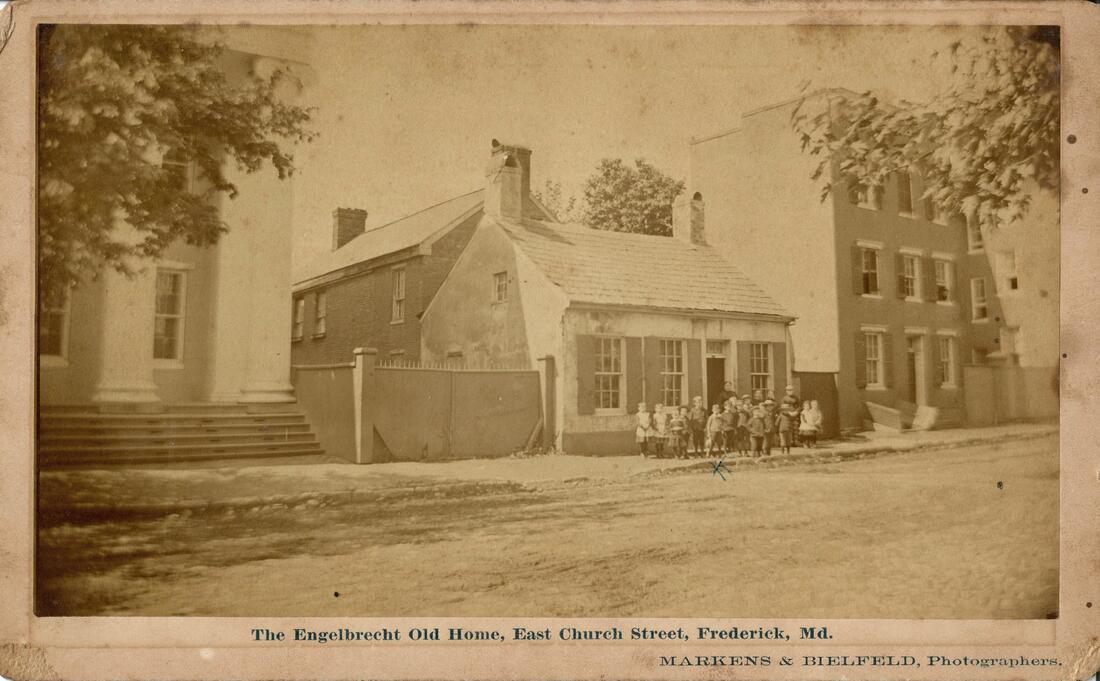

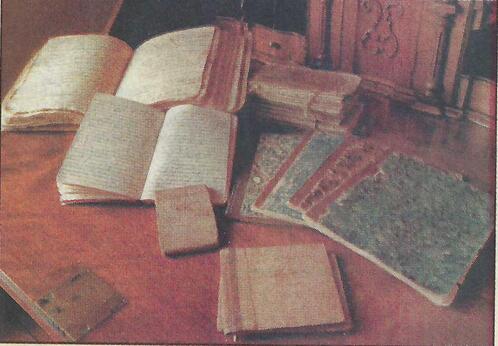

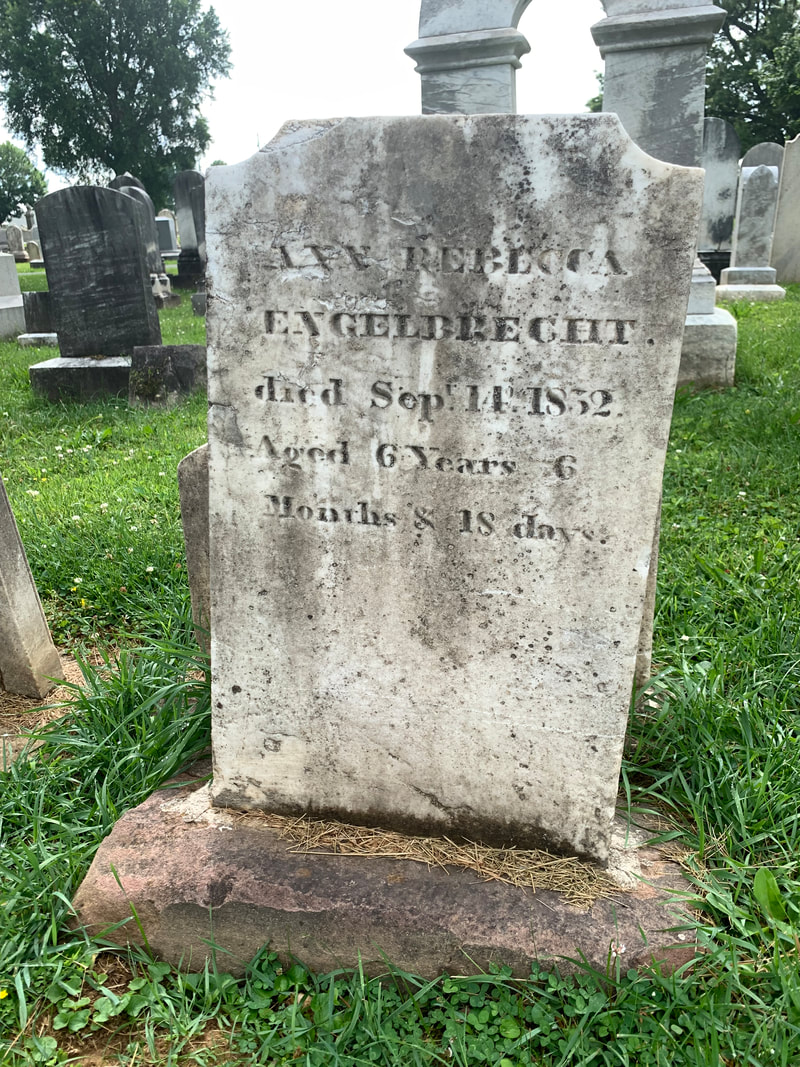

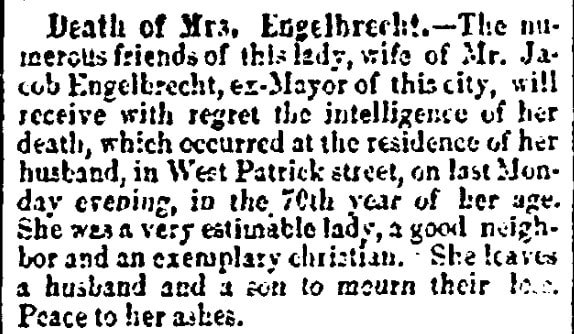

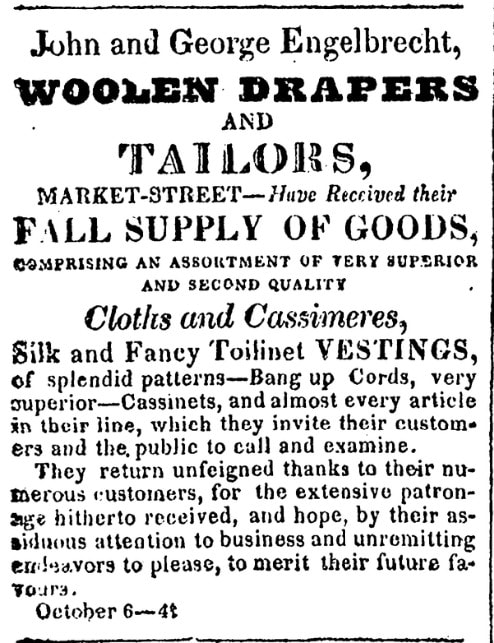

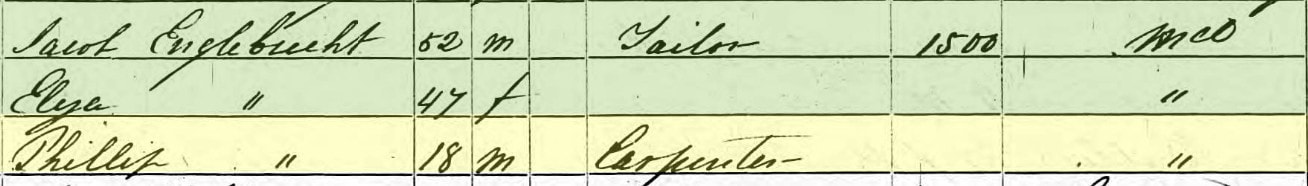

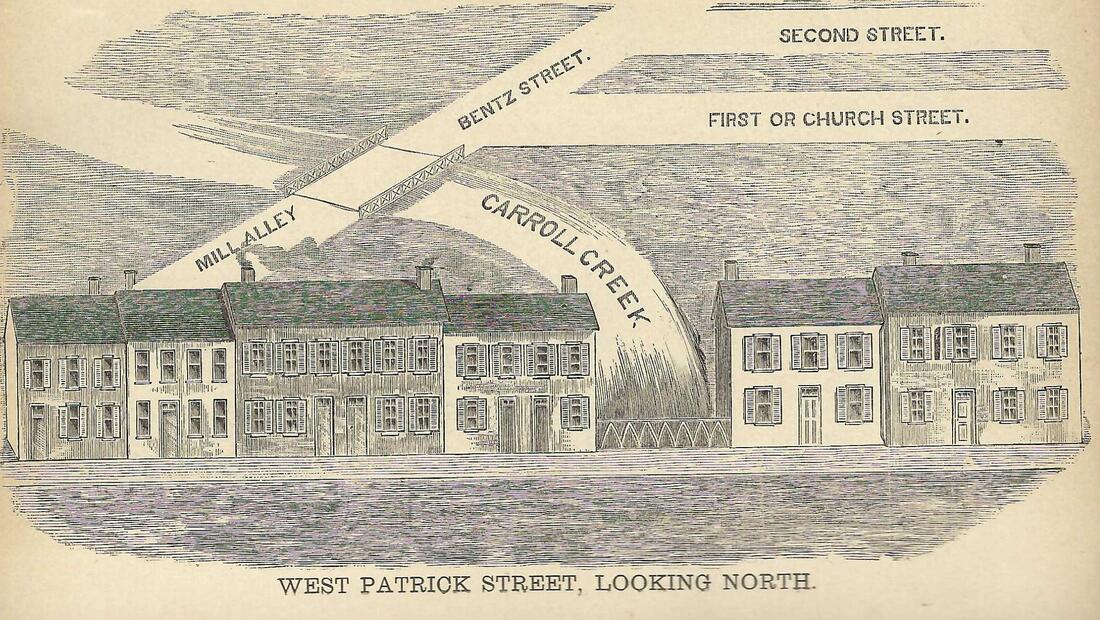

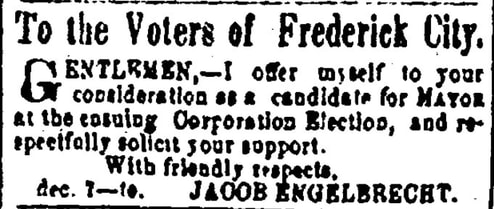

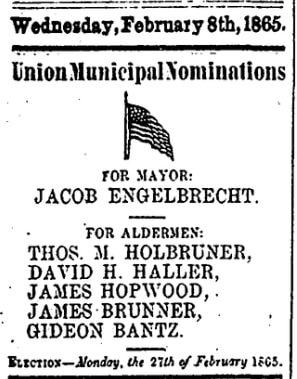

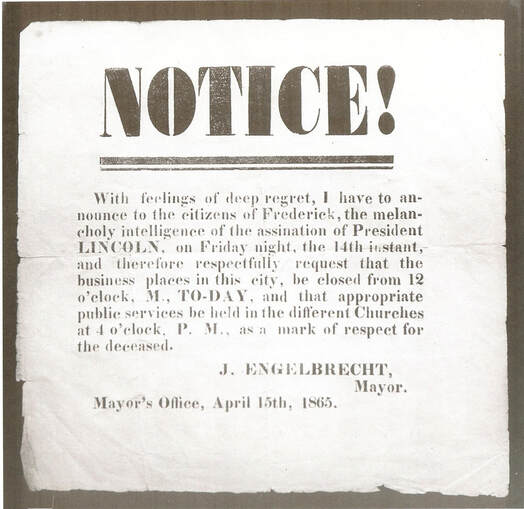

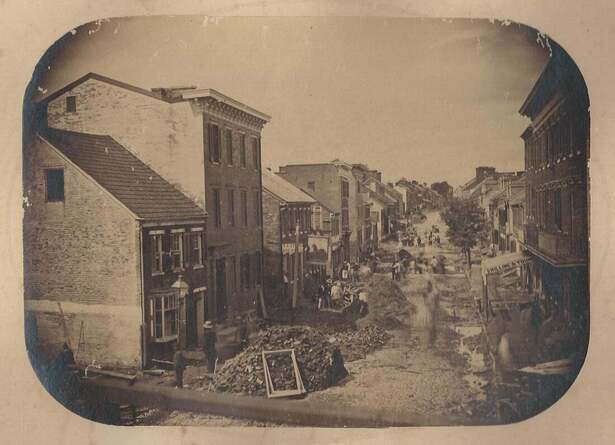

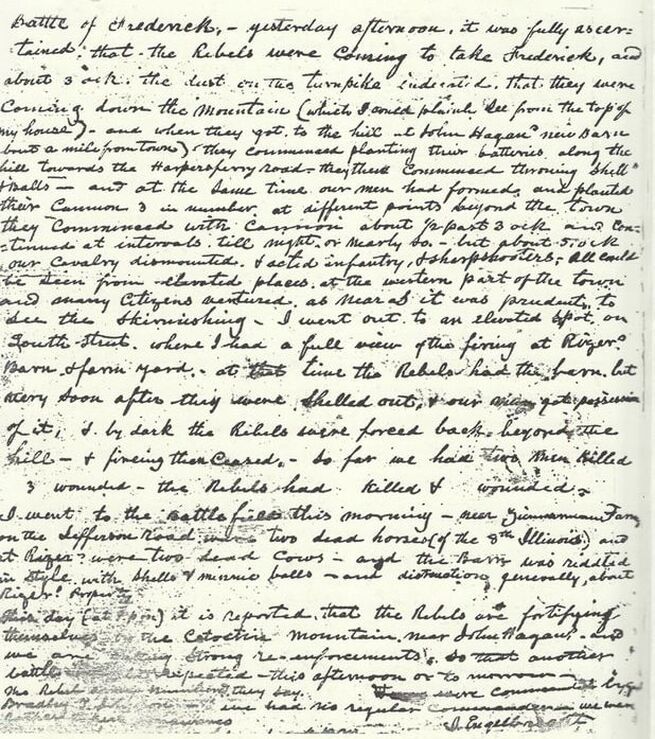

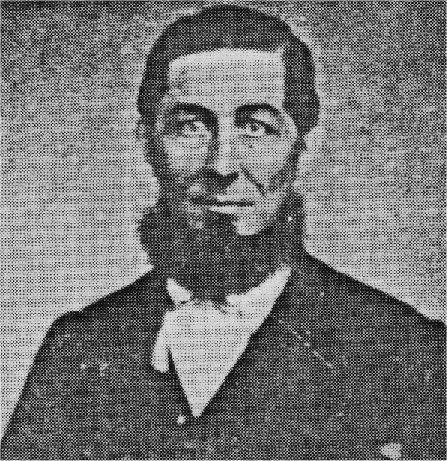

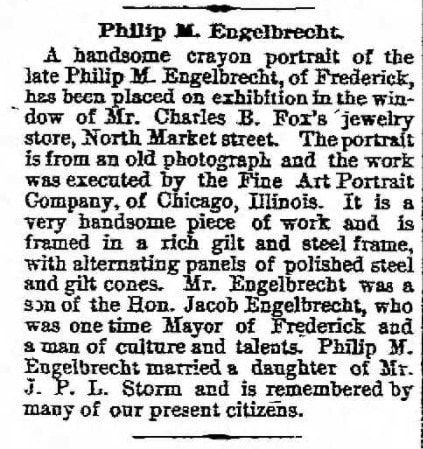

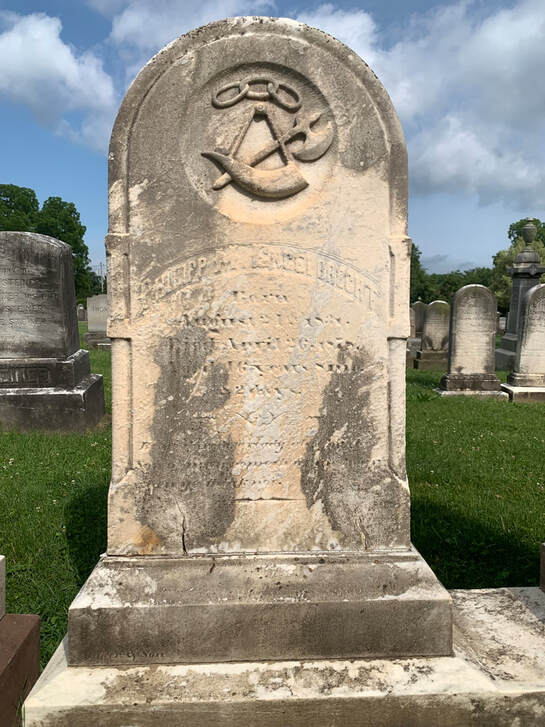

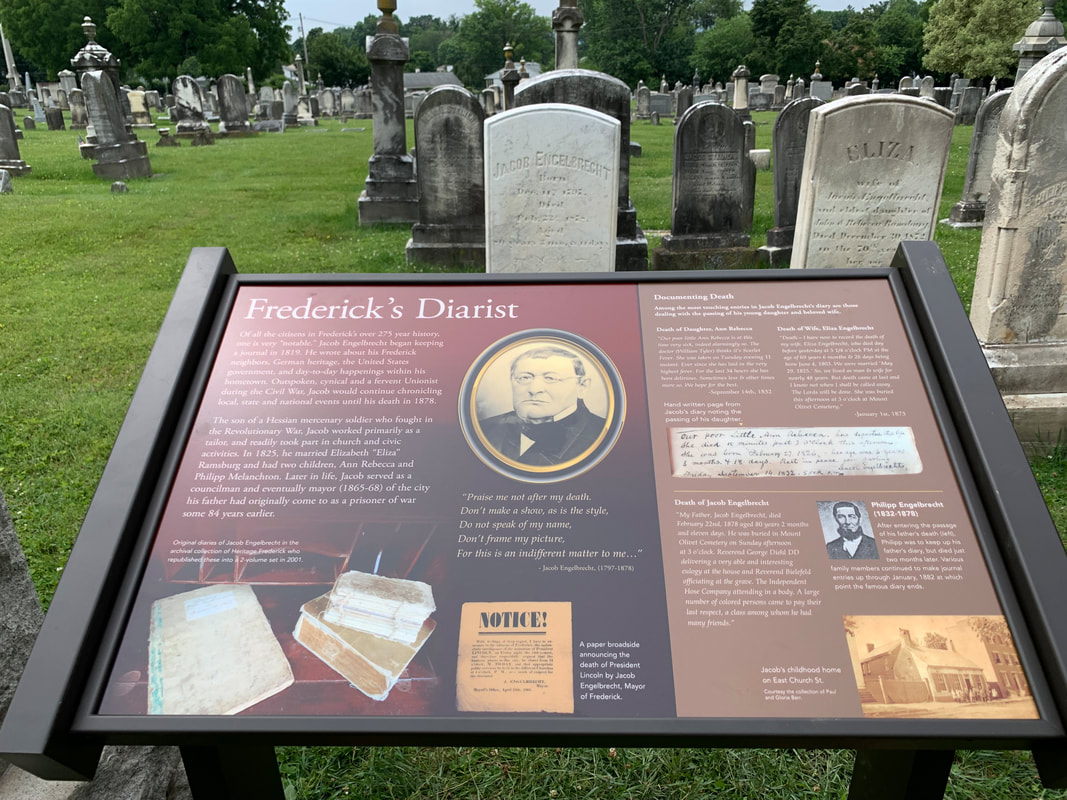

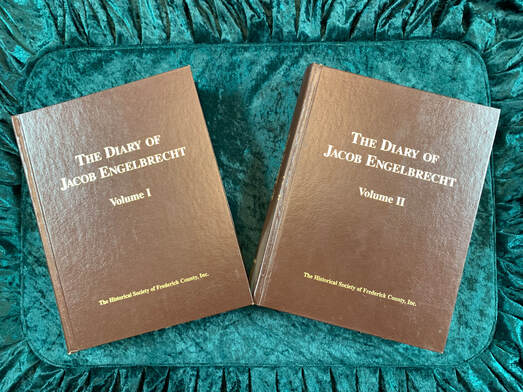

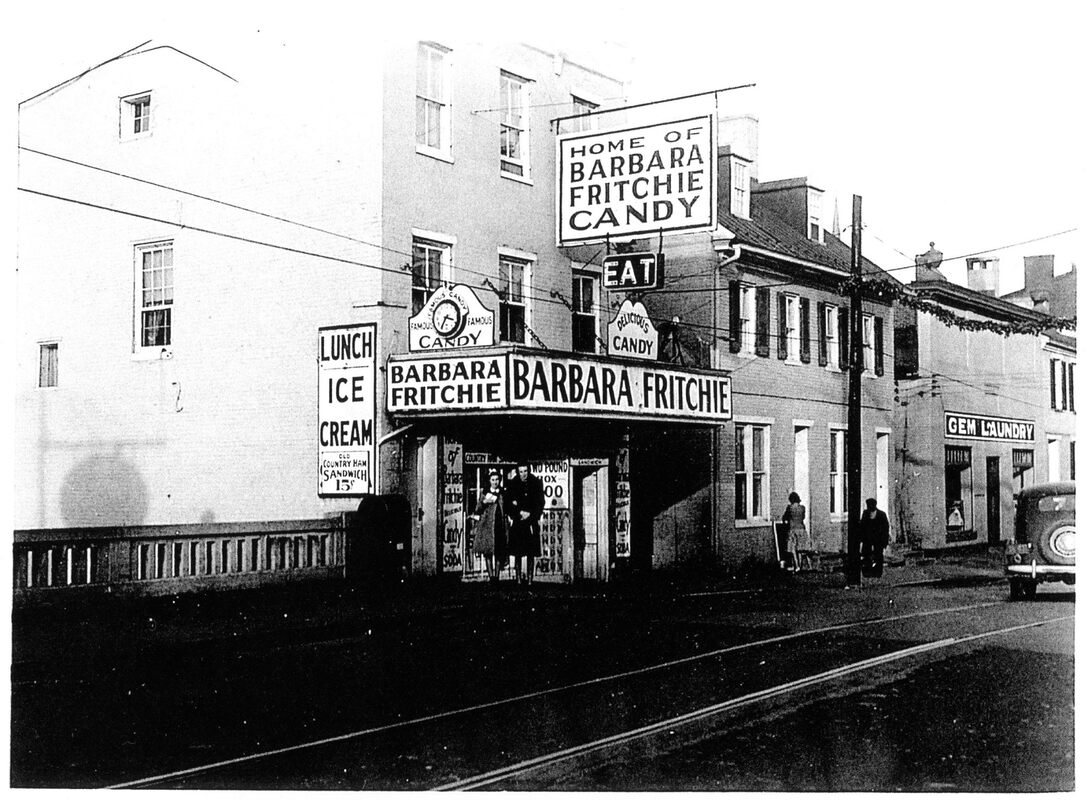

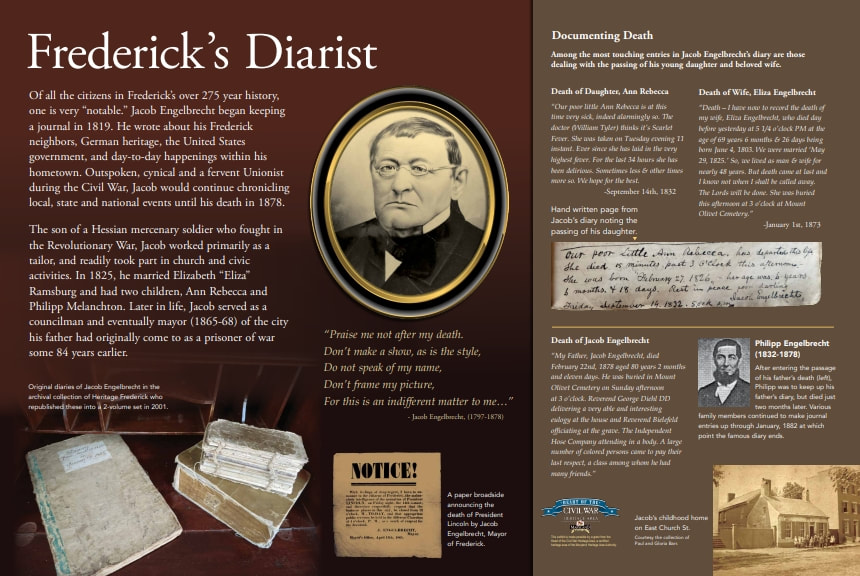

Tuesday, June 14th marked "Flag Day," the annual observation that celebrates the day in 1777 when the United States approved the design for its first flag. Although not a federal holiday, the observance dates back to the 1880s, although there is a claim that it could have started with a first formal celebration in 1861. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed June 14th as the official date for Flag Day, and in 1949 the U.S. Congress permanently established the date as National Flag Day. One more interesting fact is that Pennsylvania celebrates Flag Day as a state holiday. Last year, in 2021, our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group thought it important to recognize Flag Day with some sort of commemoration on site at the cemetery within clear view of the US flag, the same that gave inspiration for our most famous decedent to write what, in time, would become our national anthem. Of course we are talking about Francis Scott Key. We went one step further with creating a Flag Day lecture tradition in which we would feature a local author who has written something connected to Mount Olivet or those buried within. Last year, it was Lori Swerda who wrote a novel called Star-Spangled Scandal about the murder of Francis Scott Key's son, Phillip Barton Key. The dastardly act of 1859 was performed by a sitting congressman from New York, who would later lead troops at the Battle of Gettysburg. This was Daniel Sickles, who eventually beat the charge with the first successful use of the temporary insanity plea. This year's lecture focused on a true Frederick patriot and one-time mayor, whose father came to Frederick in "literal" chains as a prisoner of the American Revolution. Jacob Engelbrecht's father was a mercenary soldier from the German state of Hesse, what we would call a Hessian soldier. He was housed only a block and a half from our cemetery at the Frederick Barracks, which have held the title of the Hessian Barracks since housing these soldiers in the early 1780s. Within a century, the name of Engelbrecht would gain great reputation and respect in the Frederick community. Jacob had a big hand in "turning lemons into lemonade" through his work as a tailor and civic involvement. Interestingly, his neighbor Barbara Fritchie helped the public relations aspect of her last name as well because her father-in-law was on the wrong side of history during the Revolution as a Tory Loyalist. He unfortunately was executed for his treason, where the Hessian soldiers were welcomed warmly into the community with definitive German settlement origins dating back to the 1730s and 1740s. June 14th, 2022 was a beautiful night to salute the flag and learn about a gentleman who kept a diary of Frederick events from 1819 up through his death in 1878. To recount his life story and achievements, Heritage Frederick docent and tour guide Jim Callear prepared a nice speech to share with our participants. It was so nice and original, in my humble appraisal, that I asked Jim, a professional antique appraiser, himself, if I could republish here as the crux of a "Story in Stone" article. The following is a transcript of Jim Callear's presentation on Jacob Engelbrecht. I am honored to be speaking on Jacob Engelbrecht and his diaries on this special occasion. Before I address Engelbrecht and his work, I want to acknowledge the work of those who ensured that his diaries could be printed and accessible to the public: his family, who preserved the diaries and made them publicly available; Professor William Quynn who first published the diaries in 1976; Paul and Rita Gordon, whose tireless efforts led to the republication of the diaries in the current, expanded format; Mark Hudson, executive director of Heritage Frederick; and others who handled all phases of the editorial work that went into moving the words from Englebrecht’s handwritten diaries to the printed page. Even without the diaries, the Engelbrecht family would have merited our attention because of their role in the early settlement of Frederick. Jacob’s father, Johann Conrad Engelbrecht, was born in Bavaria, fought for the British, and came to Frederick by way of Yorktown, where he became a prisoner of war in 1781. After marching from Virginia to Maryland, he joined other prisoners at the Hessian Barracks. After news of the peace treaty with Great Britain reached the colonies in 1783, the Hessian Barracks prisoners were given the choice of staying in this country or going back to Europe. Engelbrecht stayed and soon married the daughter of a local schoolmaster. They went on to have 10 children, one of whom was Jacob. The story of Conrad, Jacob, and their succeeding generations embody the assimilation and success of many of the immigrant settlers in Frederick. I want to turn to the diaries now. In his forward to the diaries, Paul Gordan noted that Jacob Engelbrecht had several occupations – tailor, shopkeeper, cabinet maker, council member, and mayor – but had many other “preoccupations.” We know of his passion for music – he was both a member of a choir and a band member, playing the French horn. He loved to garden and he was an expert in the care and development of fruit trees, frequently telling us of his experiments in grafting the branch of one fruit tree to another. He was a traveler going to other cities on the East Coast, where he would act as his own tour guide, finding churches, government buildings and historic sites to visit and observe. And, of course, he liked wandering around Frederick. In reading Engelbrecht’s diaries, one thing is clear: he had an insatiable curiosity about his world and the people in it. I am going to briefly explore five areas where Engelbrecht recorded facts that reveal something about his world. Not only do we learn about the people and places he recorded, but we also learn what kind of person Englebrecht was. First and foremost, Englebrecht was a dispassionate recorder of facts, particularly when it came to the weather, prices of food items, deaths and marriages. We might be told whether the bride or groom was an immigrant from Europe, or the son or daughter of a family in Frederick, and who the officiating minister was. With regard to deaths, there are few character judgments and even less on how the individual deaths may have affected him. An exception to this was his diary entry regarding his daughter who died at the age of 6 from scarlet fever. “Rest in peace poor darling.” (9/14/1832). His brief entry hides the real pain he must have felt because on September 14, 1861, he wrote, “This day it is 29 years since the death of my little daughter Ann Rebecca . . . . Were she now alive, she would be 35 years 6 months & 18 days old. She died of scarlet fever.” His wife’s death was recorded with a few more details than his usual death entries but with more apparent acceptance than his daughter’s death because of his wife’s age. (1/1/1873). Another death that warranted more than his usual factual recitation was that of Roger Brooke Taney, whom he tells us was buried “in first rate Catholic style.” (10/15/1864). Another area where Engelbrecht is very guarded in what he tells us is his work. What is clear from the diaries is that Engelbrecht is very good about separating his work life from his personal life (or as Paul Gordan stated his “preoccupations”). There are few entries that deal his work as a tailor or shop keeper. One entry documents that Engelbrecht sold the contents of his shop and returned to tailoring with his brothers in the shop that his father formerly ran. (5/7/1841). Another entry describes how he had to stay up late to finish work on mourning clothes for a customer who had to attend a funeral the next day. (11/26/1821). But, Engelbrecht does not tell us much about who his customers were, where he bought his supplies, or whether he had help in his shop. He had several apprentices, but he records only when they came to work for him and when they left. Third, there were areas of Engelbrecht’s life that he was deeply passionate about: politics, abolishing slavery, and preserving the Union. He was a diehard Republican and kept score on wins and losses in both local and national elections. Engelbrecht’s views on slavery were clear. When the new Maryland constitution was adopted in 1864, Engelbrecht writes, “From this day forward and forever . . . Maryland is free from the foul blot of slavery – until yesterday there were more than 90,000 slaves . . . (& about 80,000 free blacks). ‘All men are created free.’” (11/1/1864). His view on the Union and its preservation are equally unequivocal. Just prior to the Civil War, he recorded the secession of several southern states and stated, “Maryland will never leave our glorious union, at any rate not by my consent.” (1/21/1861). At a Union pole raising signifying opposition to secession, he wrote, “The Constitution and the Union, now and forever, one and Indivisible.” (1/21/1861). Four years later at the end of the Civil War, Engelbrecht noted that the cost of the war was $2,600,000. He concluded, “the Union of this government is cheap even at that price . . .. In the gloomiest time, I did not believe that God would forsake our government & country.” (8/8/1865). Fourth, we see glimpses of his humor, his interests in entertainment, and his humanity in his diaries. Engelbrecht’s efforts at humor were sporadic and subtle: “There is an eclipse of the moon . . . at twelve o’clock, but I can’t think of staying up to see . . . a corner of the moon off. If I get sleepy, I’ll eclipse it to bed that’s better.” (2/5/1822). “Yesterday morning I bought a half ticket to the ‘Maryland State Lottery’. . . . So I have half a chance to win nothing.” (7/31/1821). Engelbrecht showed us that Frederick was not just a place where people worked – they also played (at least a little bit). There were domesticated snakes at Talbot’s Tavern (10/4/1822); there was rope dancing with Jacob Engelbrecht and his band providing the musical accompaniment (8/29/1822); and lions, tigers, and talking parrots on North Market Street (4/7/1835) – all available at low admission prices. It seems that we must include in the entertainment category, public executions. One in particular was noteworthy – John Markley, who murdered 6 people in the Newey house, was hung at the barracks before a crowd of three or four thousand, Engelbrecht estimated. (6/24/1831). I am not sure whether this rates as humor or entertainment, but as I was looking through the index under Engelbrecht’s wife’s name, I saw “weight” listed as a diary item. In fact, there were two entries. Well, to my surprise, getting weights taken back then was no easy matter – there were no bathroom scales were there? Jacob, his wife and their daughter made a trip to a local mill and were weighed, and if you need to know Jacob weighed in at 160 lbs. and his wife at 113 lbs. (4/18/1826). Humanity is defined as one’s compassion to his fellow man. We see incidents of Engelbrecht’s humanity in his diary entries. He tells us of an enslaved boy of 13 who was in his shop, and Engelbrecht learned that he did not have a name. “I took the liberty with his consent of naming him . . . . I gave him the name on a piece of paper which he promised to preserve and be governed accordingly.” (12/21/1824). On another occasion, Engelbrecht appeared before a lawyer to verify under oath that an African American was free and had been born to parents who were free. The purpose of this was to enable the man to obtain a certificate of freedom from the clerk of the Frederick County Court. 7/12/1825. Finally, where Engelbrecht excels as a diarist was in recording events in Frederick. For instance, there are nine diary entries pertaining to the flooding of Carroll Creek. Engelbrecht describes how Barbara Fritchie’s original house on the creek was torn down so the creek could be widened. (4/8/1869). Who knew the city’s flood control efforts started back them? Engelbrecht used that diary entry to write that the flag waving incident, memorialized in the poem by Whittier, “is not true.” (4/8/1869). Another interesting event he recorded was the beginning of the McMurray Canning Co., which he said many had predicted would fail. Engelbrecht’s response was that it might as well fail in Frederick Co. as else any other county. (3/27/1869). Of course, McMurray went on to employ nearly 1000 workers and produce 1 million cans of corn in one season. Of tremendous importance are his diary excepts that relate to the Civil War, Antietam, and the Battle of Monocacy, because they illustrate Engelbrecht’s view of major events going on around him that also affected the city, state, and nation. These diary entries reminded me of a program in the early days of television where news anchor Walter Cronkite would be at history-making events during the past centuries. At the end of the program, after Cronkite summarized what had happened and stated, "What sort of day was it? A day like all days, filled with those events that alter and illuminate our times... all things are as they were then, except you were there." That is the way these diary entries affect me. Jacob Englebrecht’s diaries are a gift to us, because they are our unique connection to the history of Frederick, Maryland, and the nation for a span of 60 years. I have come to understand that my appreciation for the diaries rests on their being a very personal connection to Frederick’s past, more so than our historic houses and the antiques in them. For this, we owe Jacob Englebrecht our recognition and gratitude. In addition to giving us a connection to our history, he also shows us what it means to be connected to a community, not only through his words in the diaries, but through his life, his public service, his loyalty to his city and country, and his humanity. It is fitting that we honor him as we do today. In conclusion, I will simply say as Engelbrecht did in many of his early diary entries, “So we rub along.” 5/22/1822 Jacob died on February 22nd, 1878 at his home in Frederick along Carroll Creek on W. Patrick Street. He would be buried in the family plot (Area H/Lot 276) alongside his wife and daughter. His son Philipp would take up the charge of recording this event in his father’s diary: “My Father, Jacob Engelbrecht, died February 22nd, 1878 aged 80 years 2 months and eleven days. The immediate disease of which he died, inflammation of the bowels. He was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery on Sunday afternoon at 3 o'clock. Reverend George Diehl DD delivering a very able and interesting eulogy at the house and Reverend Bielefeld officiating at the grave. The funeral was largely attended. The Independent Hose Company attending in a body. A large number of colored persons came to pay their last respect, a class among whom he had many friends.” Philipp was to keep up his father’s diary, but died just two months after Jacob. Various family members continued to make journal entries up through January, 1882 at which point the famous diary ends. After Jim's lecture presentation, participants were invited to take part in a special wayside interpretive marker unveiling at Jacob's gravesite. The honors (of unveiling) were done by Beth Molesworth, Jim Callear and the marker's graphic designer Ruth Bielobocky of Ion Design (Charles Town, WV). Ms. Molesworth is a descendant of Jacob Engelbrecht and helped make the marker possible, with additional monetary support in the form of a mini-grant from the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area. She was kind enough to say a few words about her famous ancestor, and gave thanks on behalf of her family that the famed diarist's story would be shared with visitors, tourists, lot-holders and local residents alike through this cemetery amenity. Ms. Molesworth shared that her uncle, also named Jacob L. "Jake" Engelbrecht was the one who inherited the diaries, and later donated them to the Historical Society. This gentleman was the grandson of the diarist and made this gift to the Society in 1958. In 1976, the diaries were transcribed and published for the first time. They would be republished in 2001.

1 Comment

Judith Kline Ford

6/18/2022 07:46:12 am

I regret not being able to be present for the lecture (and plaque unveiling) honoring Jacob Engelbrecht. He was my ggg great uncle.His brother, Michael Engelbrecht, also a tailor, was my ggg grandfather.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed