|

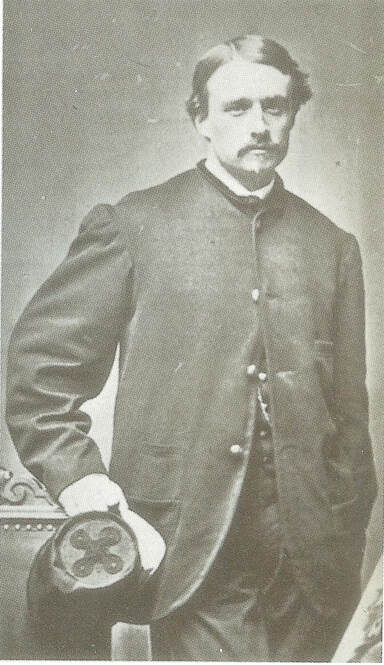

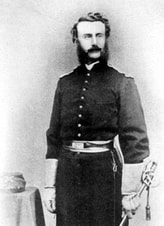

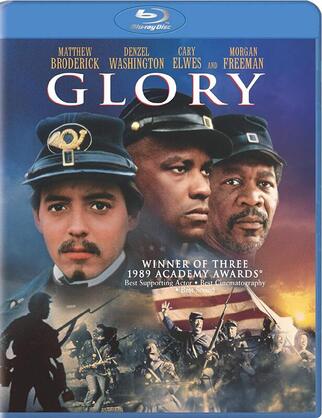

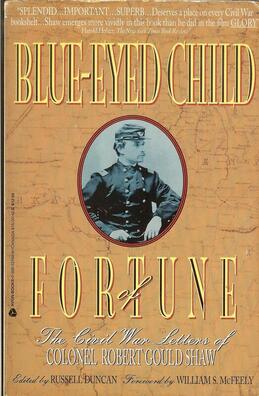

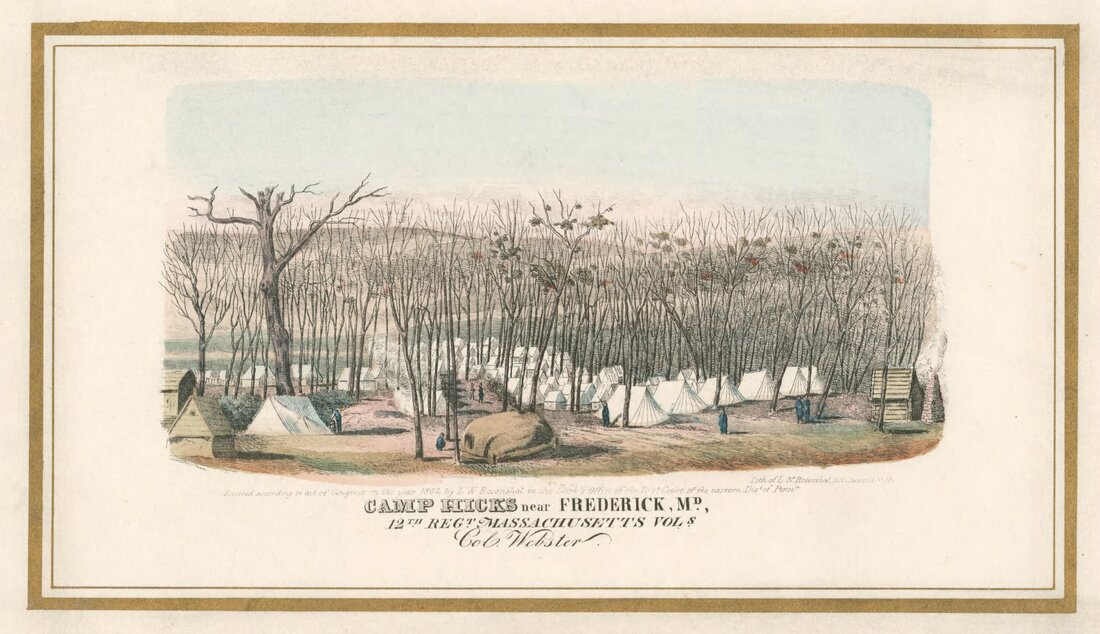

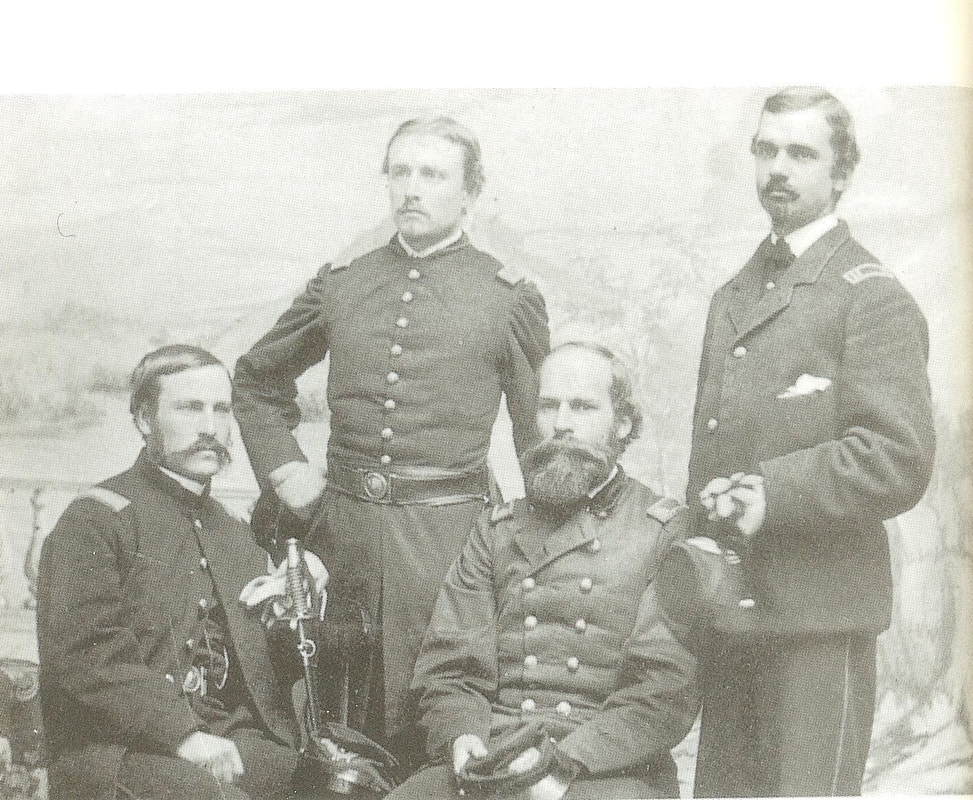

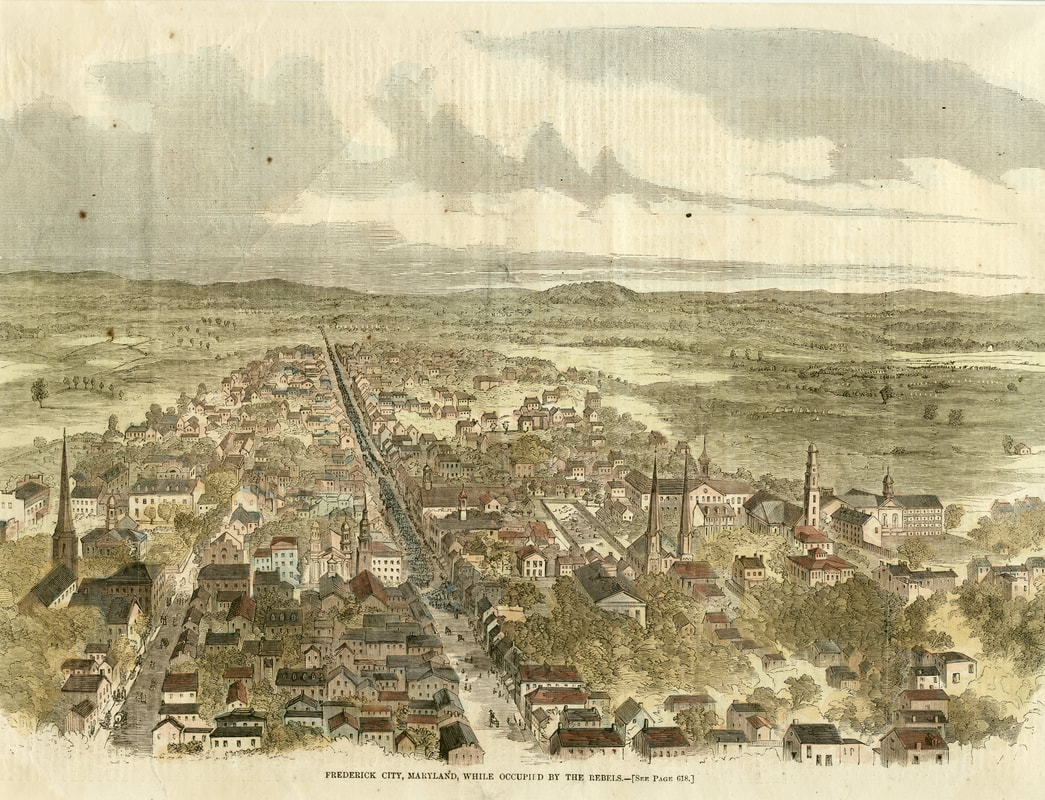

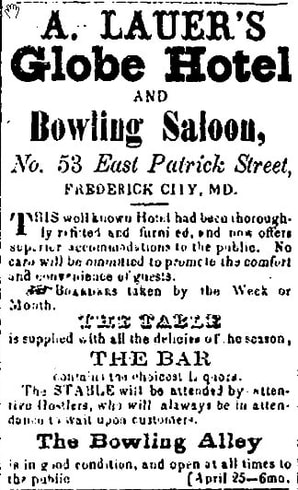

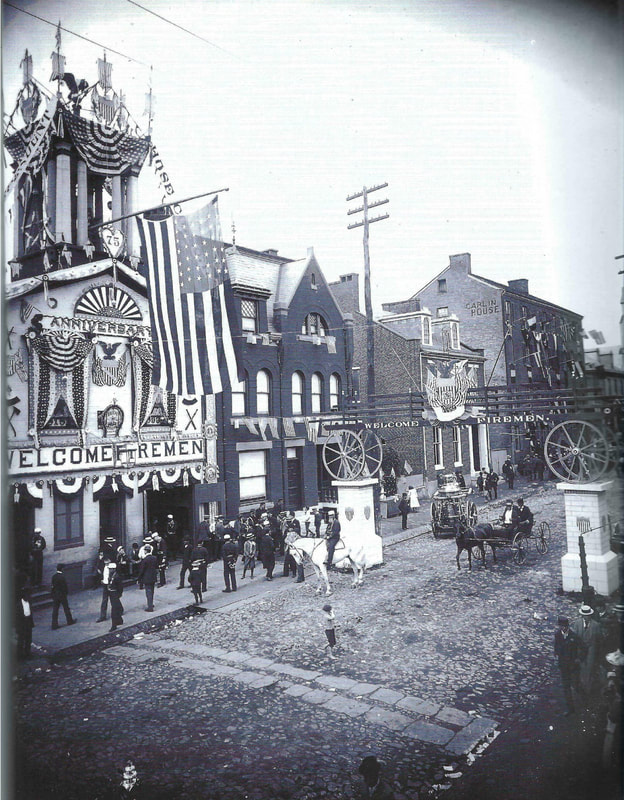

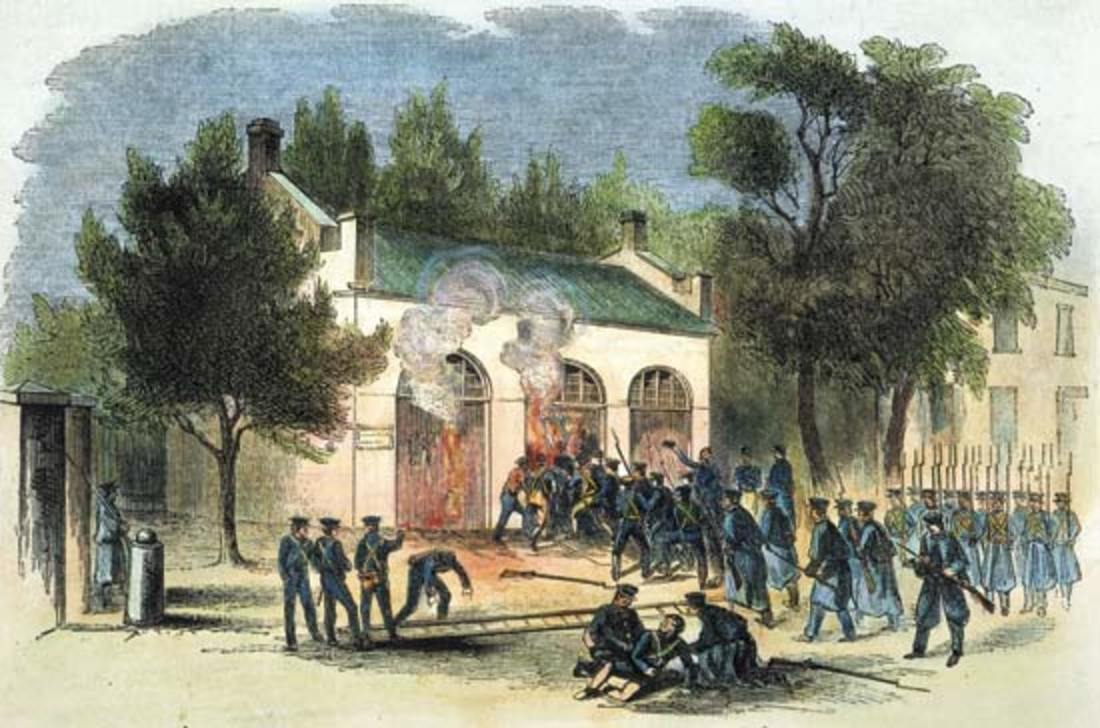

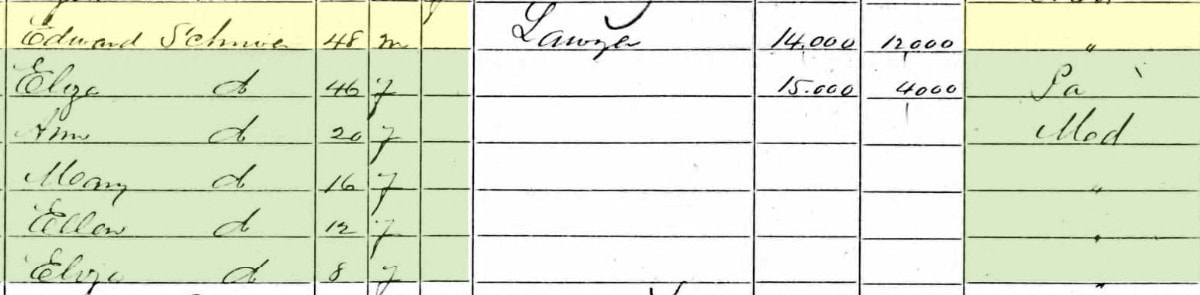

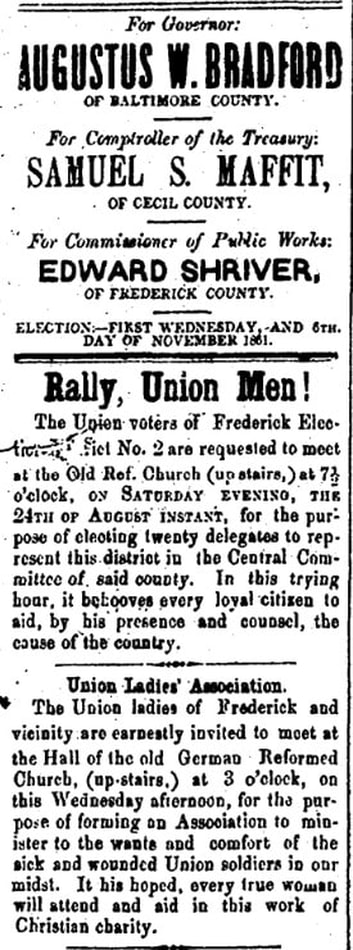

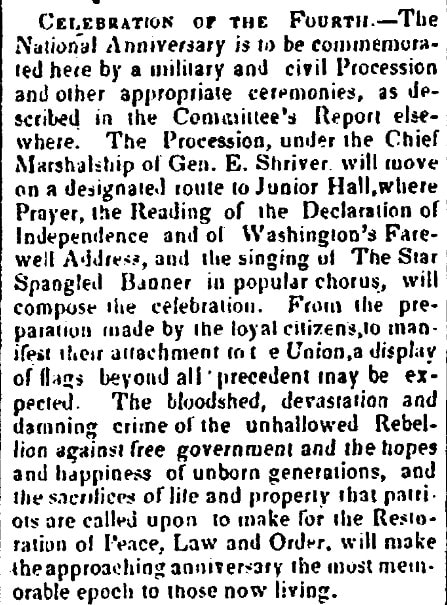

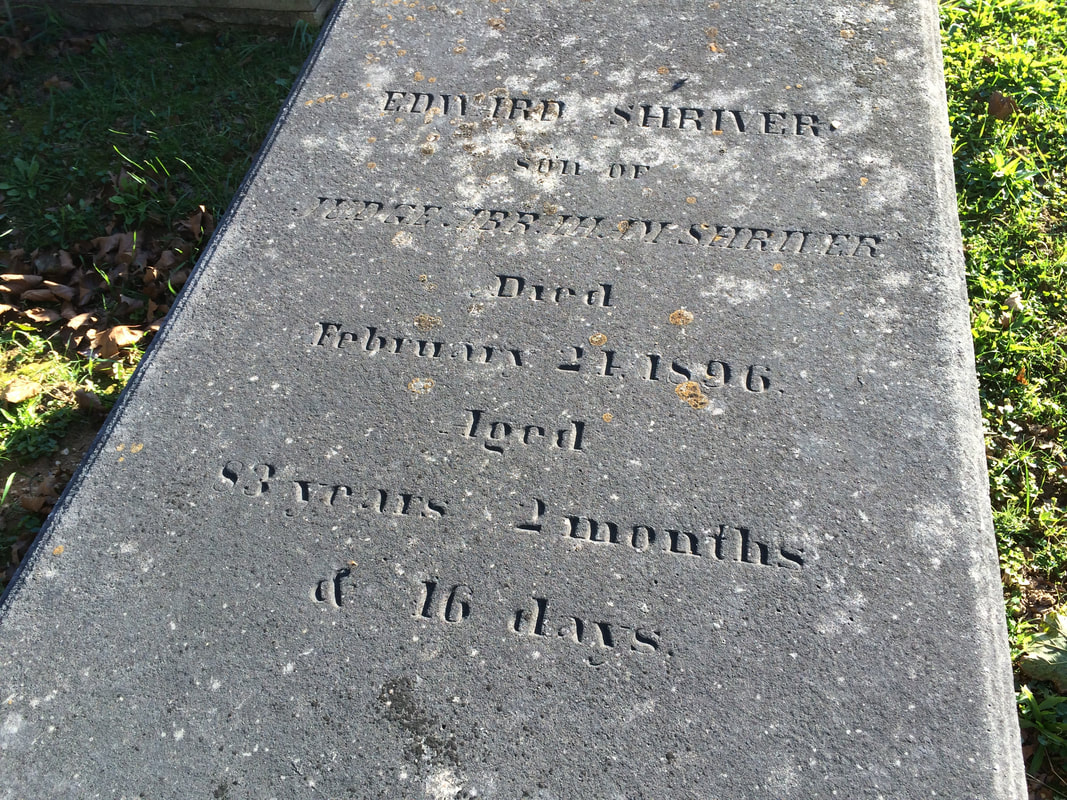

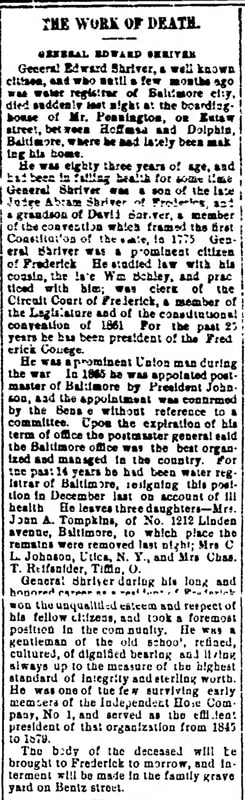

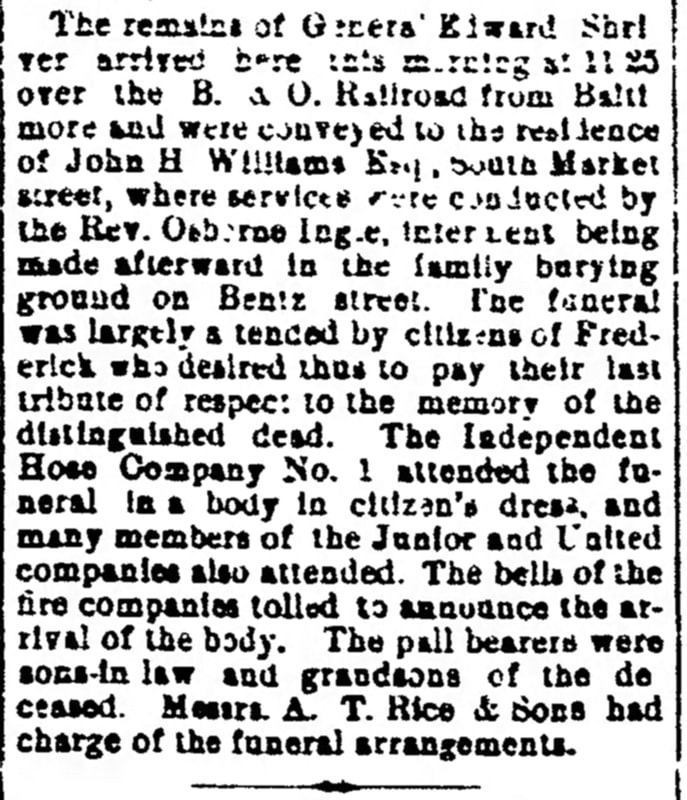

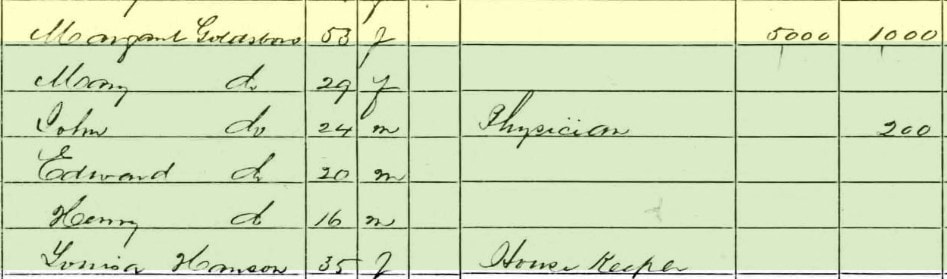

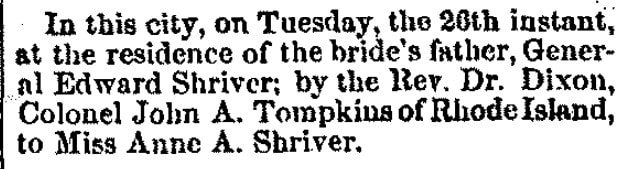

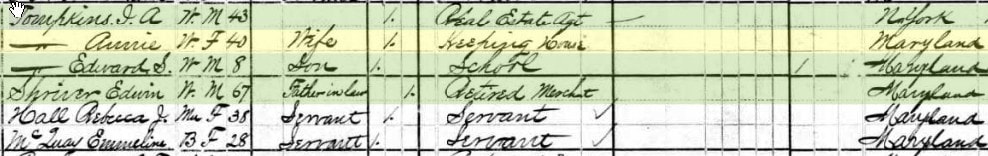

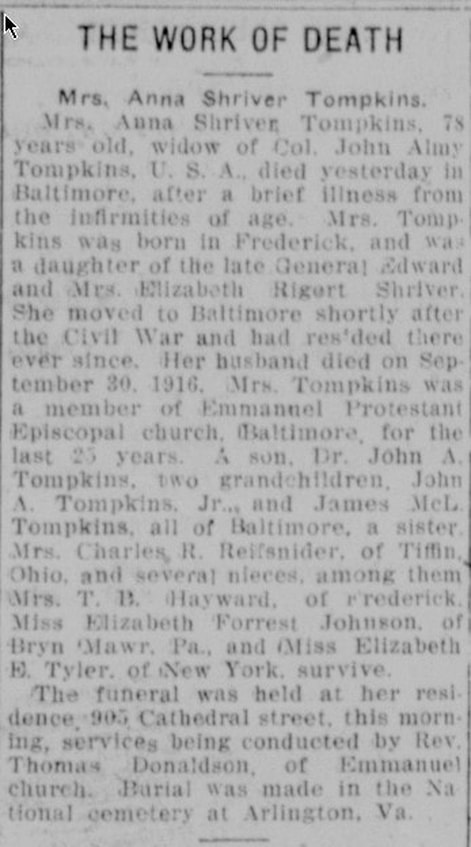

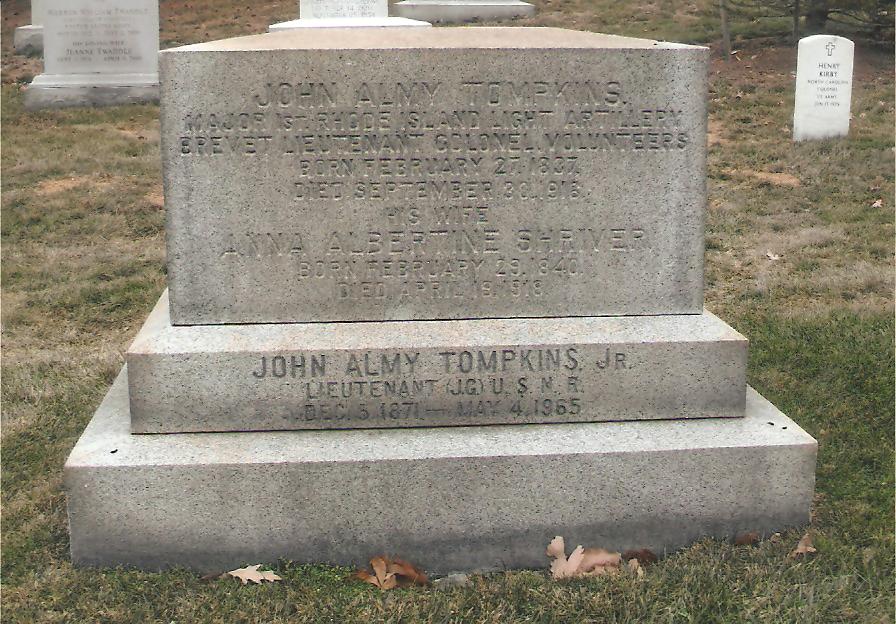

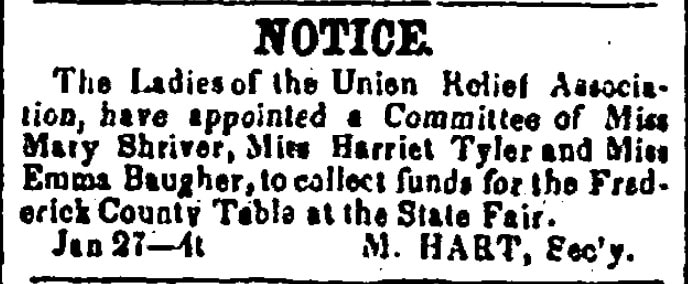

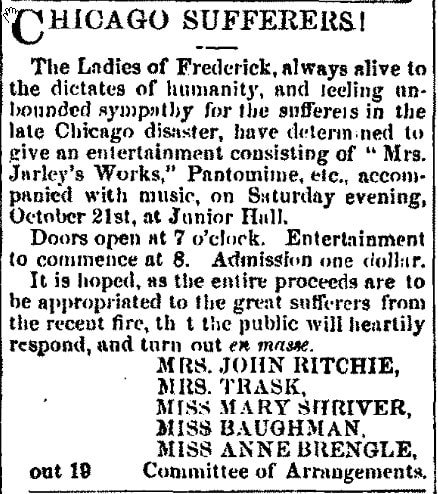

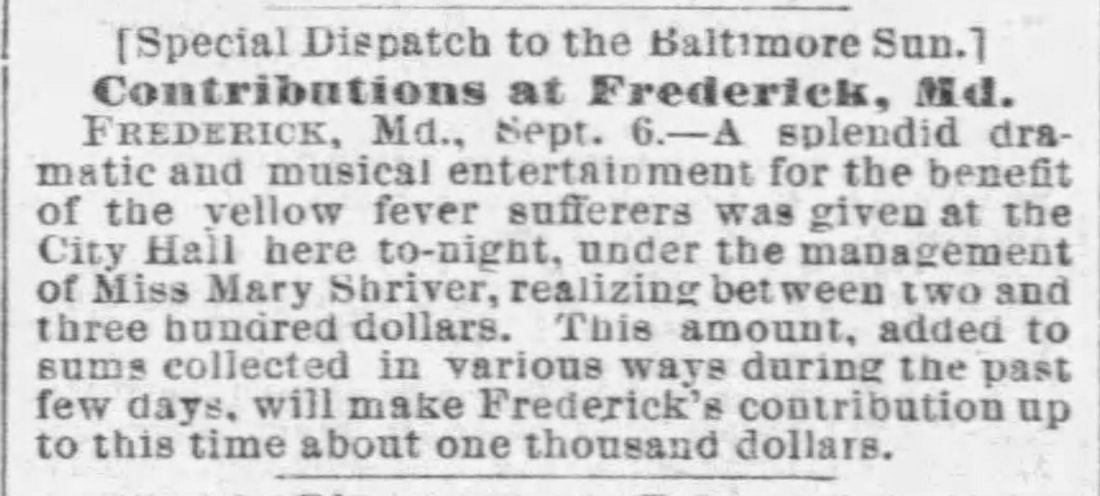

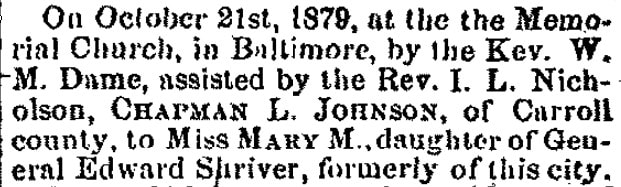

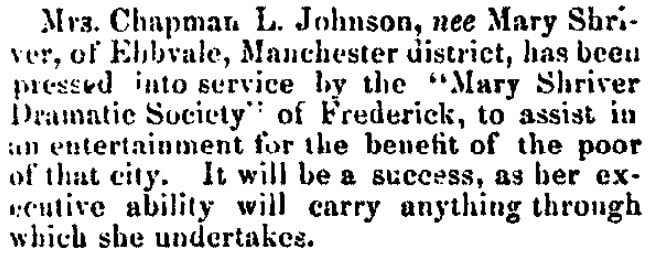

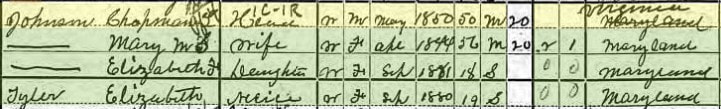

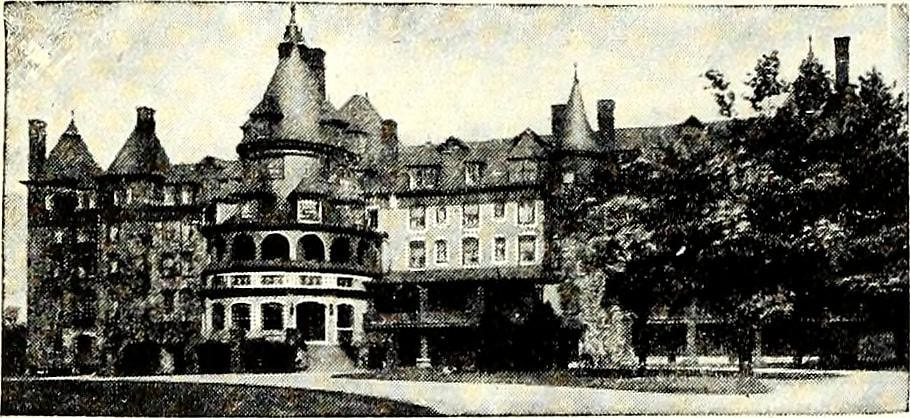

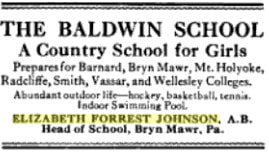

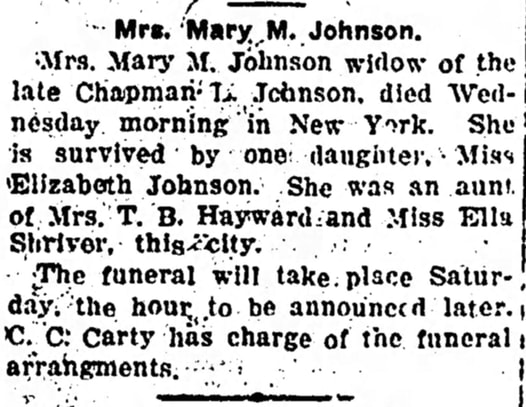

Well this year's Black History Month has one extra day in it this year, which gives me the opportunity to squeak-in and give context to a unique story with links to Mount Olivet on this final day. This two-part odyssey has nothing to do with a person of color, per se, but connects Frederick to one of the most interesting white characters found in the story of struggle for freedom and equality related to the American Civil War—Robert Gould Shaw. We are lucky to have several incredible, well-produced, historical motion pictures about warfare within reach. Many tell the story from the perspective of the human experience more so than simply battle strategies and execution. Examples include the recent Academy-award nominated 1917, along with classics such as Apocalypse Now and Saving Private Ryan. The HBO miniseries John Adams is also among my favorites as it gives a more authentic view of the American Revolution and shows the frailties and quirks of our founding fathers. Add to that list a movie which debuted 30 years ago and became an instant classic— Glory. This film, directed by Edward Zwick, chronicles the legendary 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the Union Army's second African-American regiment in the American Civil War. It stars Matthew Broderick as Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the regiment's commanding officer, and Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes, Andre Braugher and Morgan Freeman as fictional members of the 54th. For many viewers that grew up in the 1980s like myself, part of the magic of this movie was seeing this virtually unknown hero (Col. Shaw) played by high-school slacker “Ferris Bueller.” The film depicts the soldiers of the 54th from the formation of their regiment to their heroic actions at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. The screenplay by Kevin Jarre was based on the books Lay This Laurel by Lincoln Kirstein and One Gallant Rush by Peter Burchard, and the personal letters of Shaw. Glory was nominated for five Academy Awards and won three, including Best Supporting Actor for Denzel Washington. It won many other awards from, among others, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Golden Globe Awards, the Kansas City Film Critics Circle, the Political Film Society, and the NAACP Image Awards. The film premiered in limited release in the United States on December 14, 1989, and in wide release on February 16, 1990, making $27 million on an $18 million budget. So what does this have to do with Mount Olivet and Frederick? Well, Col. Robert Gould Shaw was stationed here in Frederick before he received his own glory on the battlefield. He walked our streets, stayed in homes and interacted with our citizenry—some of which reside here in the cemetery for eternity.  Robert Gould Shaw as part of the 7th New York State National Guard (Mass Historical Society) Robert Gould Shaw as part of the 7th New York State National Guard (Mass Historical Society) Robert Gould Shaw (1837-1863) If you have seen the movie, you may recall that it opens on the nearby battlefield of Antietam in nearby Sharpsburg on the morning of September 17th, 1862. Shaw, then a 2nd lieutenant, is felled by a bullet in the early morning fighting at the Cornfield. Here is some background information on the man, courtesy of Wikipedia: Shaw was born in Boston to abolitionists Francis George and Sarah Blake (Sturgis) Shaw, who were well-known Unitarian philanthropists and intellectuals of Scottish descent. The Shaws had the benefit of a large inheritance left by Shaw's merchant grandfather and namesake Robert Gould Shaw (1775–1853). Shaw had four sisters— Anna, Josephine (Effie), Susanna, and Ellen (Nellie). When Shaw was five years old, the family moved to a large estate in West Roxbury, adjacent to Brook Farm. During his teens he traveled and studied for some years in Europe. In 1847, the family moved to Staten Island, New York, settling among a community of literati and abolitionists while Shaw attended the Second Division of St. John's College, a preparatory school, at Fordham. These studies were at the behest of his uncle Joseph Coolidge Shaw, who had been ordained as a Roman Catholic priest in 1847. He converted to Catholicism during a trip to Rome, in which he befriended several members of the Oxford Movement, which had begun in the Anglican Church. Robert began his high school-level education at St. John's in 1850, the same year that Joseph Shaw began studying there for entrance into the Jesuits. In 1851, while Shaw was still at St. John's, his uncle died from tuberculosis. Aged 13, Shaw had a difficult time adjusting to his surroundings and wrote several despondent letters home to his mother. In one of his letters, he claimed to be so homesick that he often cried in front of his classmates. While at St. John's, he studied Latin, Greek, French, and Spanish, and practiced playing the violin, which he had begun as a young boy. He left St. John's in late 1851 before graduation, as the Shaw family departed for an extended tour of Europe. Shaw entered a boarding school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland where he stayed for two years. Afterward, his father transferred him to a school with a less strict system of discipline in Hanover, Germany, hoping that it would better suit his restless temperament. While in Hanover, Shaw enjoyed the greater degree of personal freedom at his new school, on one occasion writing home to his mother, "It's almost impossible not to drink a good deal, because there is so much good wine here." While Shaw was studying in Europe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, an abolitionist friend of his parents, published her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1854). Shaw read the book multiple times and was moved by its plot and anti-slavery attitude. Around the same time, Shaw wrote that his patriotism had been bolstered after encountering several instances of anti-Americanism among some Europeans. He expressed interest to his parents in attending West Point or joining the Navy. Because Shaw had had a longstanding difficulty with taking orders and obeying authority figures, his parents did not view this ambition seriously. Shaw returned to the United States in 1856. From 1856 until 1859 he attended Harvard University, joining the Porcellian Club, and the Hasty Pudding Club, but he withdrew before graduating. He had been a member of the class of 1860. Shaw found Harvard no easier to adjust to than any of his previous schools and wrote to his parents about his discontent. After leaving Harvard in 1859, Shaw returned to Staten Island to work with one of his uncles at the mercantile firm Henry P. Sturgis and Company. He found work life at the company office as disagreeable as some of his other experiences. With the outbreak of the American Civil War, Shaw volunteered to serve with the 7th New York Militia. On April 19th, 1861, Private Shaw marched down Broadway in lower Manhattan as his unit traveled south to man the defense of Washington, D.C. Lincoln's initial call up asked volunteers to make a 90-day commitment, and after three months Shaw's new regiment was dissolved. Following this, Shaw joined a newly forming regiment from his home state, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. On May 28th, 1861, Shaw was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the regiment's Company H. A great way to examine this man (at this time and beyond) is through the book Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. This work was edited by Russell Duncan and published Avon Books in 1992. In July of 1861, his regiment was sent to today’s panhandle area of West Virginia where he encamped at Martinsburg, Charles Town and Harpers Ferry. In early fall, Shaw and his fellow “Bay Staters” were encamped in Montgomery County, primarily Darnestown, with forays at Muddy Branch and Seneca Creek. In December, the 2nd Massachusetts came to Frederick to set up winter quarters. The chosen place was located roughly three miles east of Frederick City, just across the Monocacy River in the vicinity of Linganore Road in what one soldier called “a beautiful wooded area on a hill.” The government called this site Cantonment Hicks after the Maryland governor (Thomas Holyday Hicks), but the soldiers would refer to it more lovingly as “Camp Hicks.” Here, troops had tents and built some small, wooden barracks, each boasting iron coal stoves. Robert Gould Shaw wrote the following letter home on December 8th, 1861. Camp Hicks near Frederick, Md December 8, 1861 My dear Effie, Your weekly & welcome letter came yesterday. I look for it regularly now and shall be much disappointed the first time it misses, if such a thing can be imagined after your long & faithful regularity. I didn’t have time to write again from Seneca, before we left, as I said I should, for the order to march came at 12 ½ A.M. We got off early in the morning. It was tout ce qu’il y a de plus unpleasant to be waked up at Midnight, the weather icy cold, to wake up in their turn the cooks, & see about rations. We had a good two days march, for the cold weather kept us going. The roads didn’t soften even at noon. The day after we arrived it changed and we have had almost an Indian summer for 5 days, during which time we have made ourselves comfortable & can defy Jack Frost when he comes again. Yesterday I went into Frederick to see Capt Mudge who has been ill for about 3 weeks. I found him much better & was coming out, not having any acquaintances top visit when I fell in with Copeland & it turned out to be a fortunate rencontre for me. He took me to a house where I was presented to two young ladies & we shortly sallied forth all together & after picking up Mrs. Copeland, another lady & Capt. Savage, we repaired to a bowling alley where we had a perfectly jolly time all the afternoon. We then took a walk, after which we went home to the house of the afore-mentioned young ladies, & took tea. In the evening there was a great deal of playing on the piano & chorus singing, in which latter we all howled, & made as much noise as we could. I can’t describe to you my sensations at sitting once more in a nice parlor & seeing real ladies with petticoats about. I had hardly realized before that for 5 months we had been living like gypsies & seeing only men, I had really not spoken to a lady since we left New York. These two are daughters of Genl Shriver, a Union man here, who was very active in helping break up the Maryland legislature 2 months ago. One of them is a very nice girl indeed, I should think, if one can judge on so short an acquaintance. She sings very well too. The letter goes on about other things at camp, but of key interest to me here is the mention of downtownFrederick—in particular, fascinating elements include a bowling establishment and the Shriver family. I found a bowling alley advertised in a Frederick newspaper from 1866 and located within the Globe Hotel of Mr. A. Lauer and located at 53 E. Patrick Street. I’m not sure when it originated, but there was also a bowling lane located within the Independent Hose Company on East Church Street. I am well aware of Col. Edward Shriver and made mention of him in an earlier “Story in Stone” published back in October of 2018. The blog dealt with eyewitnesses to the legendary John Brown Raid of Harpers Ferry in October, 1859. Edward Shriver was born on December 8th, 1812, the second son of Judge Abraham and wife Ann Margaret Shriver. The colonel was a Frederick lawyer who in 1854 had provided the Agricultural Society of Frederick County with the land that has served home to the Great Frederick Fair to this day. Shriver served in Maryland’s House of Delegates from 1843-1845 and was asked to serve as Secretary of State by two different governors, but declined. Between 1851 and 1857, he was a clerk of the Frederick County Court. Edward Shriver was also active in the Maryland Militia, and became colonel of the Sixteenth Regiment. In the fall of 1859, Col. Shriver quickly began assembling the three town companies of militia, and went to Harpers Ferry by train to survey the chaotic scene for himself, before bringing the larger militia contingent on the scene. He would oversee the Frederick men as the group holds claim to being the first responders on the scene, and successfully kept Brown “holed up” in the engine house until Robert E. Lee and his US Marines arrived from Washington, DC. Col. Shriver even talked personally with Brown, hearing his demands regarding the hostages he had taken, including one Frederick man who is buried in our cemetery by the name of George Brengle Shope. The Shrivers lived in the house that still stands today at 114 N. Court Street, diagonally northeast of Court Square. This was a convenient location for Col. Shriver’s occupational pursuits and likely housed his law business, as it still serves that purpose today as a sign above the front door calls it the Court Square Law Building. Sadly, Edward Shriver lost his wife, Elizabeth Lydia (Riegart), on December 2nd, 1860. The widower had the task of raising four daughters into adulthood, amidst his busy working and civic life. During the outbreak of the Civil War, Shriver, called a “staunch Unionist,” helped mobilize the citizenry of town and assisted Governor A. W. Bradford in administering the draft and served as the governor’s judge advocate for matters pertaining to conscription. Shriver also has received credit for preventing the meeting of a Maryland Secession Legislature. Through devotion to the Union, he would pick up the moniker of “General” along the way. After the war, Col. Shriver would be appointed postmaster of Baltimore by President Andrew Johnson, a job he held from 1866-1869. He also would serve as registrar of Baltimore’s water department. He died In Baltimore at his residence on Eutaw Street on February 24th, 1896. He was first buried in the Shriver family burial plot, once located on the west side of N. Bentz Street, south of Rockwell Terrace. This was an extension of the old German Reformed Graveyard, today comprising Frederick’s Memorial Park. The entire family plot would be removed to Mount Olivet on May 11th, 1904, and now these burials can be found in the northern part of Area MM (Lot 23). Here, he was buried beside his wife Elizabeth. But what of the Shriver daughters mentioned by Robert Gould Shaw? These were the ones that accompanied Shaw in the bowling foray, and a walk about town to follow. This culminated in a return to the Shriver household in which the hostesses engaged the 24-year-old Massachusetts’ soldier in singing and gave him the warm visual of ladies in petticoats? From the letter, we can sense that one, in particular, caught Lt. Shaw’s eye as he referred to her as “a very nice girl indeed, I should think, if one can judge on so short an acquaintance. She sings very well too.” Well the 1860 US census shows that the Shrivers had four daughters. Two, Ellen and Eliza, can be ruled out because they would have been far too young in late 1861. That leaves Anna Albertine Shriver (b. 1840) and Mary Margaret Shriver (b. 1844).  John A. Tompkins John A. Tompkins Anna (aka Annie) seems like the first choice as she was 21 at this time. She would marry Col. John A. Tompkins of New York in 1867. Perhaps Anna fits the description because it’s obvious she fancied a military man like her father? As a captain in 1862, John Almy Tompkins commanded Battery A, 1st Rhode Island Artillery at the Battle of Antietam. His battery was part of the Second Corps attack toward the Sunken Road, also known as Bloody Lane. Captain Tompkins and his men fired over 1,000 rounds of ammunition in about three hours and withstood a Confederate infantry attack right into their guns that led to hand to hand fighting. Tompkins and the 1st Rhode Island had visited Frederick the previous summer of 1861, encamped for a night at the Hessian Barracks from June 17th-18th. He would participate in some of the most famous battles in the war including the Wilderness, Fredericksburg and Gettysburg. After the war, Mr. Tompkins served as Superintendent of the Baltimore Chrome Works, and later became a real estate broker in Baltimore. In the 1880 census, the Tompkins can be found living on Linden Avenue. Note that Anna’s father is living with her at this residence. Anna died in April of 1918 and is buried with her husband in Arlington Cemetery. Mary Shriver is the only other option for Col. Shaw’s possible “Frederick crush.” She was born on April 18th, 1844, making her 17-and-a-half at the time of the December 7th excursion with Col. Shaw—certainly not out of the question. From what I have gleaned of Mary, she seemed to have been an incredibly kind woman as there are several articles describing her as such through her benevolent work during the war and beyond. Not only did she raise money and volunteer to care for wounded soldiers, she also headed up relief missions to help the victims of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and was director of Frederick’s Poor Fund for many years. She seems to have possessed theatrical talent as she helped produce and present entertainments that served as fundraisers in town. Mary wouldn’t marry until later in life, October of 1879 to be exact. Her groom was Chapman Love Johnson (1850-1915), a schoolteacher from Richmond, Virginia. She may have met him through her vast array of relatives living in Carroll County, site of her family’s ancestral home of Union Mills. The Johnsons would reside in the hamlet of Ebbvale, just outside Manchester and northeast of Westminster. They had one daughter, Elizabeth Forrest Johnson, and eventually removed to Utica, New York. Chapman was later employed as a civil engineer. Chapman Johnson passed in Lansdale, PA as the Johnsons were staying with their daughter at that place. Elizabeth, a 1902 graduate of Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, NY) had just been hired as head of the Baldwin School in Bryn Mawr and founded in 1888 by namesake Florence Baldwin. This was a private school for girls offering educational instruction from pre-K through 12th grade. The Johnson’s daughter took the reins from Ms. Baldwin, herself. Mary Margaret Shriver Johnson died four years later in New York on November 5th, 1919 at the age of 75. She would be buried next to her husband on Mount Olivet’s Area MM/Lot 2. Their graves are roughly fifteen yards from Mary’s parents.  Perhaps it’s a good thing that Mary, if she was indeed the apple of Col. Shaw’s eye for one cold, December day in Frederick in 1861, charted a different life for her life away from Glory’s famed Robert Gould Shaw. Her daughter, Elizabeth, would lead and grow the Baldwin School for 26 years until stepping down in 1941. The school thrives today, thanks in part to the tremendous fundraising, marketing and recruiting done by Miss Johnson. Today it boasts a strong theater and music departments and an extensive computer lab located in a recently renovated wing named for the former leader. The chief fundraising arm of the institution is fittingly named "The Elizabeth Forrest Johnson Society." Miss Johnson never married, but moved on to making further educational contributions at the Woodstock Country School in Woodstock, Vermont. The school which closed its doors in 1980, had a library that bore Miss Johnson’s name, and she is buried in nearby Riverside Cemetery. Look for my “part two” of this story next week as I share a few more connections to Col. Robert Gould Shaw, Frederick places and Mount Olivet residents

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed