|

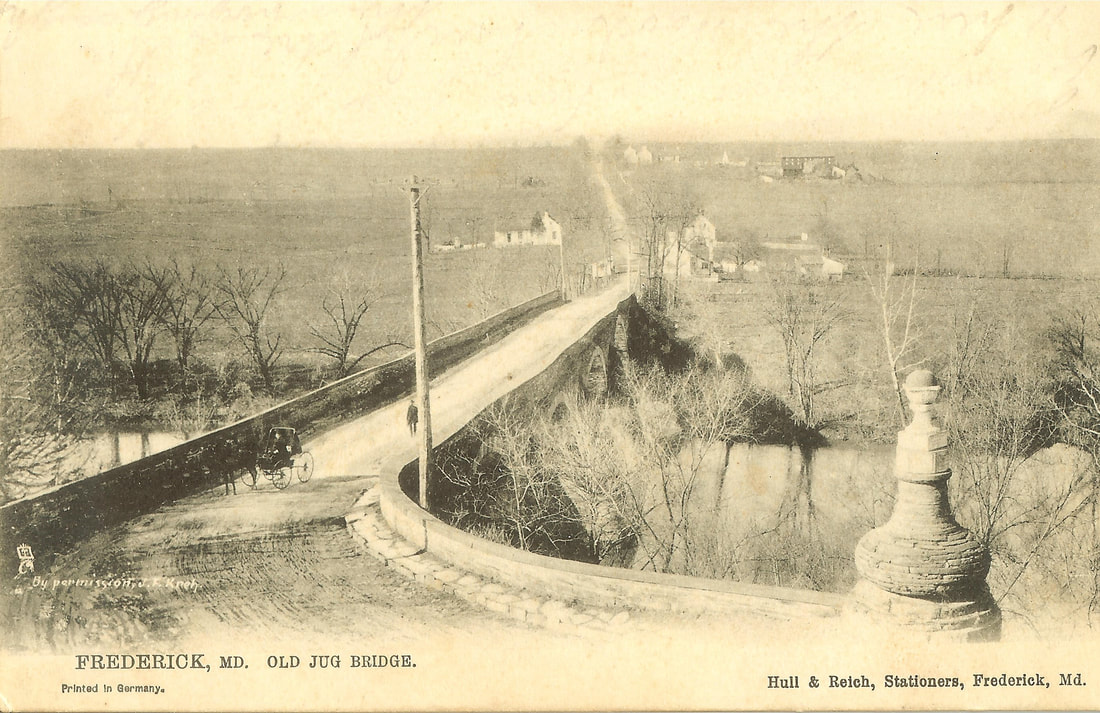

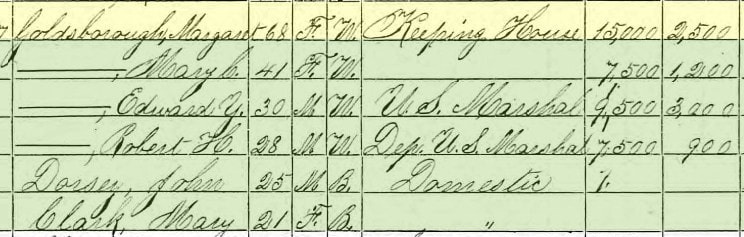

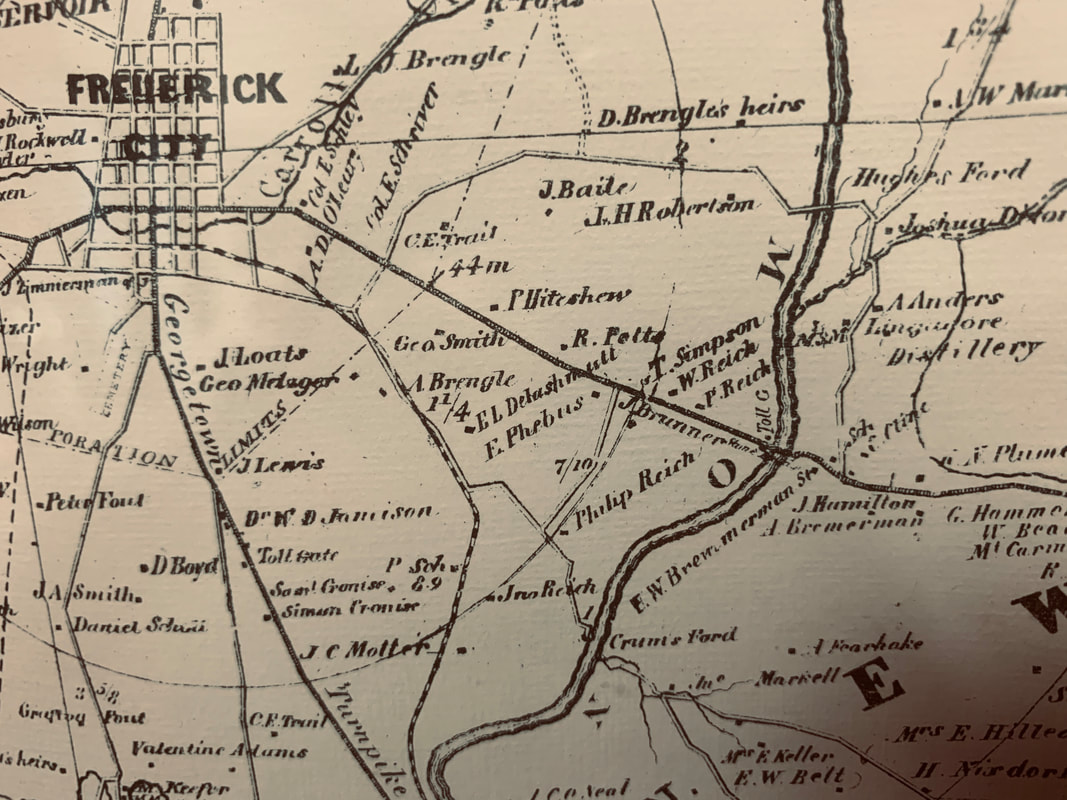

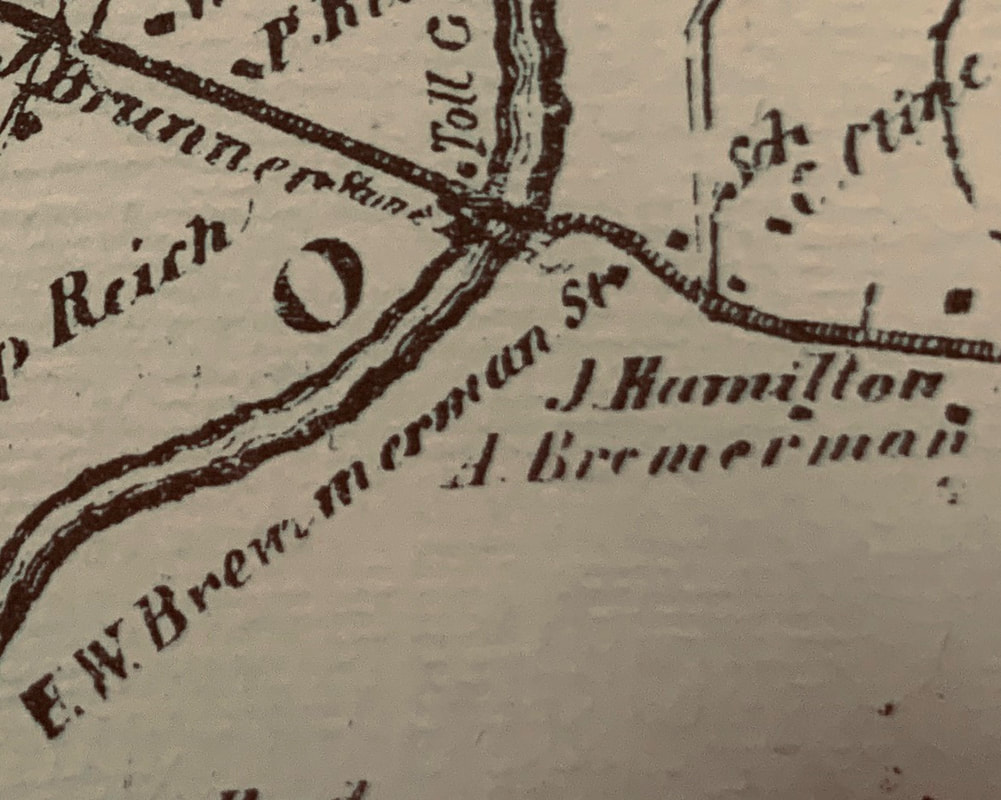

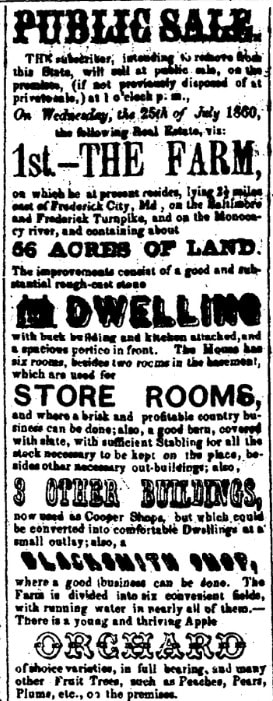

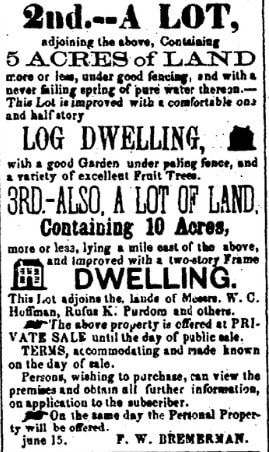

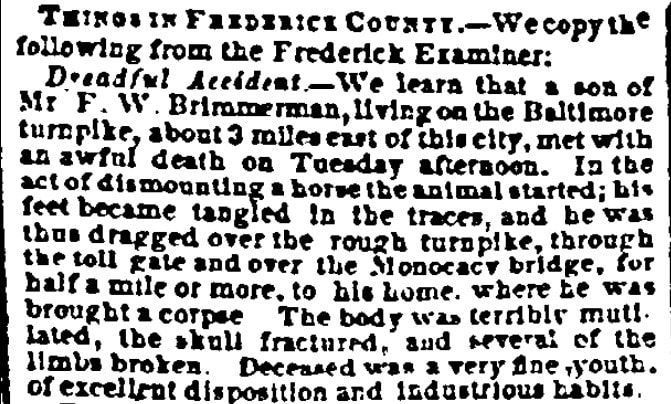

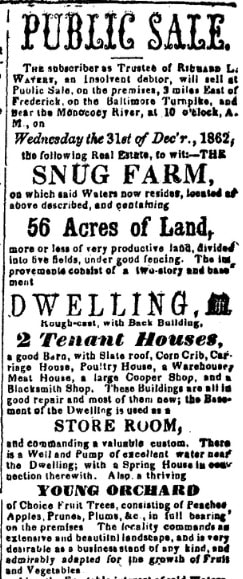

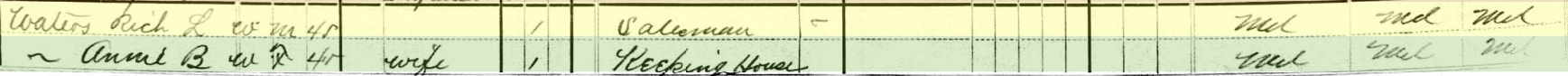

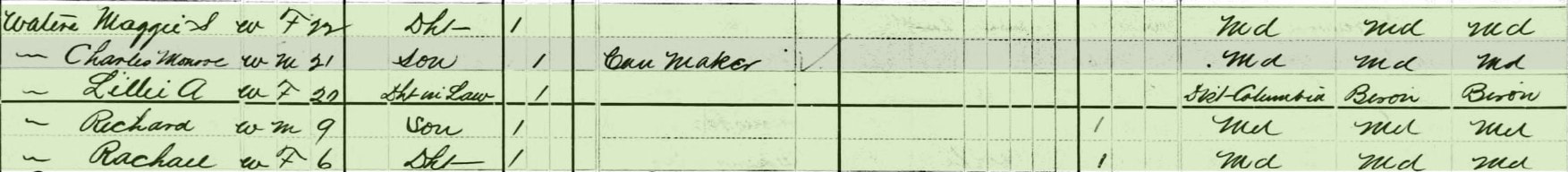

This is part-two of a story chronicling some of the local places frequented, and people met, by Col. Robert Gould Shaw of the American Civil War. If the name seems eerily familiar, you may recall being introduced to Shaw as the fearless leader of the 54th Infantry Regiment of Colored Troops who stormed Fort Wagner in the motion picture Glory. Shaw was formerly with the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment as a 2nd lieutenant, and spent the winter of 1861-1862 encamped just east of the Monocacy River and Frederick City at a place called Camp Hicks. In part 1, I shared a letter written home (by Shaw) to his sister, Effie, in which he talked warmly of spending a day with two of the daughters of Col. Edward Shriver, a lawyer, politician, officer and all-around, key Union man here in town. This correspondence was found in a work called Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. The work was edited by Russell Duncan and published Avon Books in 1992. My fascination, in respect to “Stories in Stone,” lies in the fact that the above-mentioned Col. Shriver and a daughter, Mary, are buried here in Mount Olivet. To think, each had a brush with greatness. I often have wondered how the colonel and his daughters reacted upon hearing news of Shaw’s untimely death on July 18th, 1863 in South Carolina while recalling their fond encounter(s) with the dashing young, soldier the previous year?  Camp Hicks Camp Hicks More Letters Home The next few correspondences written by Lt. Shaw were atypical of the time of year. It was December, and more importantly, Christmastime. In letters written on the 14th and 25th, Shaw laments the fact of being away from family and the pleasures of home during this special time of year. Apparently, we soon learn that Shaw had received a special gift from his sister mid-month—42 pairs of mittens. With the holidays behind him, Shaw in his first letter of the new year recounts some of the non-glamorous experiences of his military duty. Cantonment Hicks Jany 15 1862 My dear Effie, I have, I believe three letters from you unanswered, the last received day before yesterday in which you relate your encounter with, and defeat by the invidious fog. I hope he relented at last and that you have got away. I proceeded immediately after receipt of yours to inspect my checks and I don’t think you w’d find them much less flabby than formerly. Indeed, Mother’s account of my corpulency must have been a little exaggerated for I don’t perceive much increase my-self. I returned yesterday noon from the Monocacy bridge, between here and Frederick where I was on guard for 24 hours, and where I should have had a very pleasant time if it hadn’t been for three brats who tormented me. I stayed in a house near the bridge, and thought at first that the landlady was a very pretty & pleasant woman, but the bad behavior of the above-mentioned children soon brought out some little characteristics which were, to say the least, not ladylike. She got very much enraged and said to the nurse: “Hang you, you black imp, I’ll knock your black head off”—and to the children “Get out of this or “I’ll smack your jaws!” and made use of many other expressions. At night instead of putting the children to bed, the plan was, to get them asleep downstairs & then carry them up. Of course, this was a tedious process & involved much screaming, swearing, bawling & blubbering. Three times it was tried & three times they waked up on the way upstairs. After the third failure the noise was something terrible—all the three children screamed at the top of their lungs. Mrs. waters cussed & swore at the black girl. The black girl cried and actually said it wasn’t her fault. Mr. Waters consoled himself & vainly tried to amuse the 2 children by vigorously playing upon the most infernal old fiddle that ever was manufactured and beating time very hard with his cowhide boots. I sat with a smile on my face, but despair in my heart trying to concentrate my ideas sufficiently to understand "Halleck’s Elements of Military Art & Science.” May I be preserved in the future from such scenes at these! I didn’t bargain for anything of the kind when I joined the regiment. I originally read this particular letter for the first time about 15 years ago and pondered the location of this residence of the Waters family. I knew it was in the vicinity of the old Jug Bridge’s eastern approach, today’s MD144 over near Bartonsville and Spring Ridge, and not far from the site of Camp Hicks off of Linganore Road. Jug Bridge itself was a marvel in engineering for its time, having been built in 1808-1809 as part of the Baltimore-Frederick Turnpike. It was a true asset in the transport of travelers, pioneers, and natural resources and farm products from western Maryland to eastern manufactories and the port of Baltimore. It was equally important in the American Civil War for moving troops. It behooved the Union Army to protect this important gateway from being sabotaged by the Confederates--hence Shaw’s guard duty assignment. So the next question is this: "Who was this family whose house Shaw and other soldiers took refuge in during the war?" I looked at two old Frederick maps: the Isaac Bond Map of Frederick County (1858) and the Titus Atlas Map of 1873. I could not find a Waters family name associated with any houses in the immediate area on either map. The US census records of 1860 and 1870 were of no help as well because I didn't find any Waters in this specific location. I started to deduce “Waters” families by looking at those buried here in Mount Olivet, because otherwise they wouldn’t be relevant to me for my story’s sake (as this is a blog about folks buried in Mount Olivet.) The exercise limited me down to three gentlemen who seemed to match up age-wise to being of “young father age” in the year 1862. Two, of the three men, had little kids in 1862, and only one had three at this time. This latter suspect perfectly fit the bill of siring the “brats” that tormented the man who would lead the legendary “54th Mass” later this same year. My person of interest was Richard Linthicum Waters. I would soon find that his wife, Ann Virginia (Hobbs) Waters, had family in the immediate area—father Rezin Hobbs (1810-1891) and wife Margaret Galezio (1810-1881). The neighborhood was known more commonly by the name of Pearl, nearly a century-and-a-half before the name Spring Ridge would come around. I still didn’t know where this house was, but asked my research assistant, Marilyn Veek, to search real estate records for a clue. I shared with her my “non-findings” on the maps earlier mentioned, not to mention census records. I had found Richard L. Waters living in Carroll County in 1860 within the Freedom District at the hamlet of Freedom. This is the approximate location of Centennial High School today, just northwest of Eldersburg in southern Carroll County. He was listed as a farmer, and I found other supposed relatives of his father-in-law (Rezin Hobbs) in the area. In 1870, the Waters family was living in Frederick City and Richard was listed as a green-grocer and living on East Patrick Street. Richard Linthicum Waters was born February 11th, 1834, the son of Ignatius and Susan R. (Linthicum) Waters. In 1850, the Waters lived in the Howard District of Anne Arundel County, and Ignatius was listed as a Methodist minister. This area would become Howard County in 1851. Family history pointed towards the family being slaveholders. Richard married wife Anna Virginia Hobbs on October 7th, 1856. As far as I could ascertain, the Waters had the following children: Sarah Margaret “Maggie” Waters (1857-1887) Charles Monroe Waters (1859-1909) Amelia Waters (1860-1863) Minnie Waters (1862-1865) Ida Kate Waters (1866-1869) So this proved my postulate of Richard and Ann Waters having three children with the potentyial for extreme "brattiness" in January, 1862 at which time Lt. Shaw would have stayed in their home in between guard duty shifts atop the old Jug Bridge. However, where was the Waters’ home in 1862, as I could not prove that the family was living here in the Bartonsville/Pearl area on the east side of the Monocacy River, and along the National Pike? That’s when the “smoking gun” was discovered by my trusted assistant. In August 1860, Richard L. Waters obtained the property named “Snug Farm” from Frederick W. and Malinda Bremerman. Ann Waters father (Rezin) and husband (Richard) would enter into an agreement to mortgage the parcel for $4,500. It can be found on the 1858 Isaac Bond map and labeled under the name of F. W. Bremerman. The property is the first dwelling found on the east side of the Monocacy along the Frederick-Baltimore turnpike, on the southside of the road.

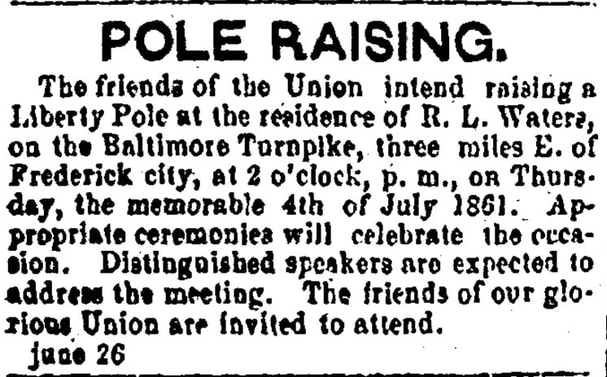

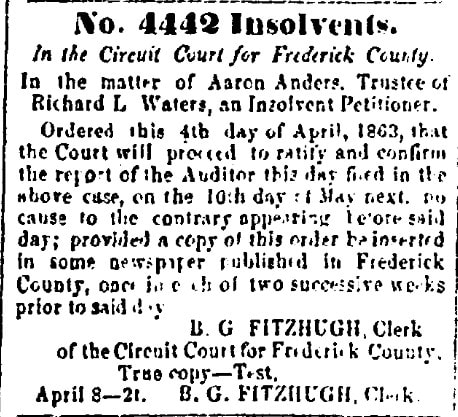

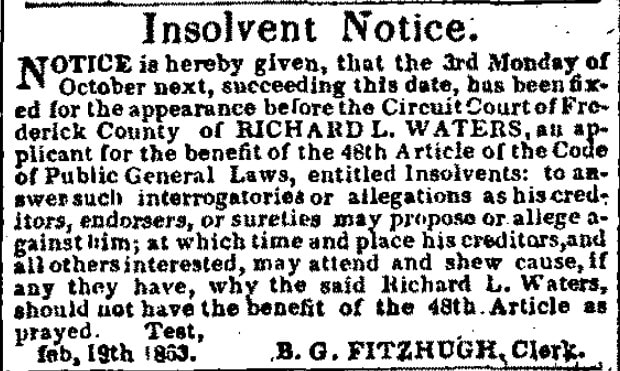

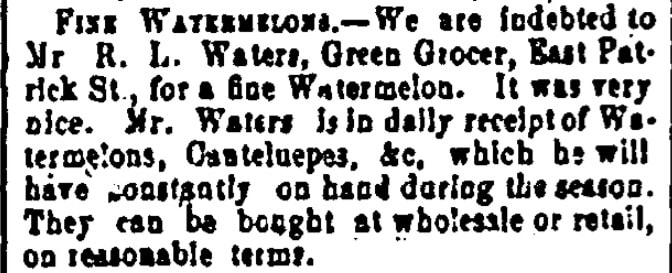

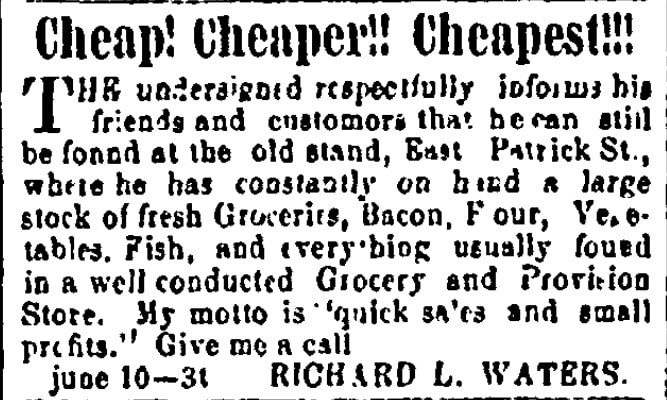

While the Bremermans were losing children in the late 1850s, the Waters were gaining them. Perhaps, family help was needed from Ann Waters’ family ( the Hobbs) who lived here in this vicinity. This would have been a comfort for the young mother in childbirth, along with relatives to look after her other small children. Besides, if we can trust Lt. Shaw’s judgment, those Waters' kids were a handful to say the least! The Waters owned slaves in the 1860 census and possessed a domestic servant in 1870. So it is not far- fetched that the family had at least one slave in January, 1862, whom Mrs. Waters verbally attacked in front of Robert Gould Shaw. Interestingly, this would be one of the first images of slavery and oppression witnessed by the wealthy New Englander who would help mold the most famous Black fighting regiment in US history (the 54th). An interesting paradox, found all to often in Frederick’s history as “a border county within a border state,” is that Mr. Waters was a die-hard Union Man. He even hosted a Union rally on his property back in the summer of 1861. One of the speakers at this event was Col. Edward Shriver. The Shriver family, one of the town’s most loyal and patriotic, (of whom I mentioned in part I of this article) also owned slaves, as did Frederick’s greatest Union supporter of all-time—Barbara Fritchie. So don’t let anybody tell you that the American Civil War was solely an act to end slavery as there were many factors at play, and motivations for men to fight on both sides (states rights, nationalism, patriotism, economics and capitalism, abolition of slavery, humeris, etc). Now back to the family of Richard L. Waters, host to Robert Gould Shaw in December, 1861. The couple would have other children born later in the decade so I’m sure the sleepless nights didn’t end for several years to come. As much as I feel sorry for Mr. and Mrs Waters, I, of course, feel more sorry for the slaves and servants that had to dote on the brats with little say in matter. So what happened to the Waters family? Well, it appears Richard declared bankruptcy in spring of 1868. This led to the Waters family losing the fore-mentioned property and likely precipitated the move into Frederick. I found a few ads beginning in 1866 where Richard is advertising his business wares as a green grocer. By 1880, the Waters had moved again—this time to Baltimore. In the 1880 census, Richard is listed as a salesman, and the family was living on Lombard Street. Two more children blessed the family in the forms of Richard Vincent Waters (1870-1926) and Rachel N. Waters (German) (1873-1947). Sadly, the Waters had endured the deaths of three children in the 1860s, perhaps leading to financial woes and the original move from “Snug Farm” to Frederick. Daughter Amelia, the youngest of the “three brats,” died in February, 1863. Two other daughters, Minnie and Ida Kate would die in 1865 and 1869 respectively.

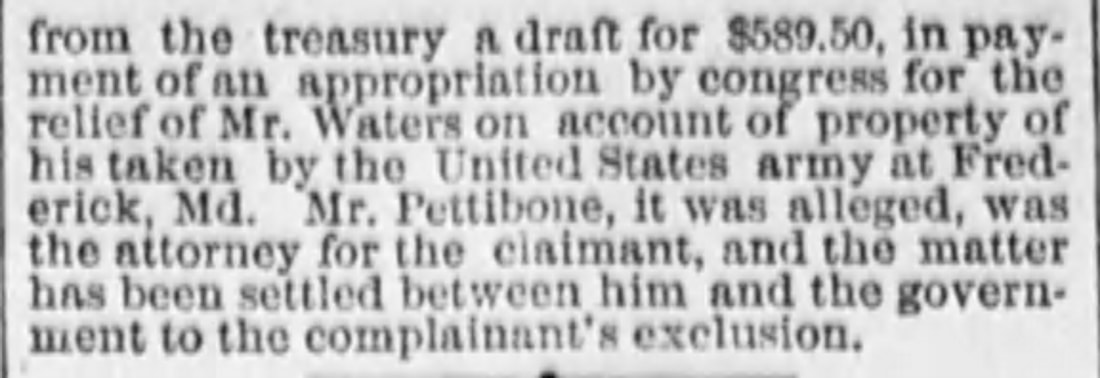

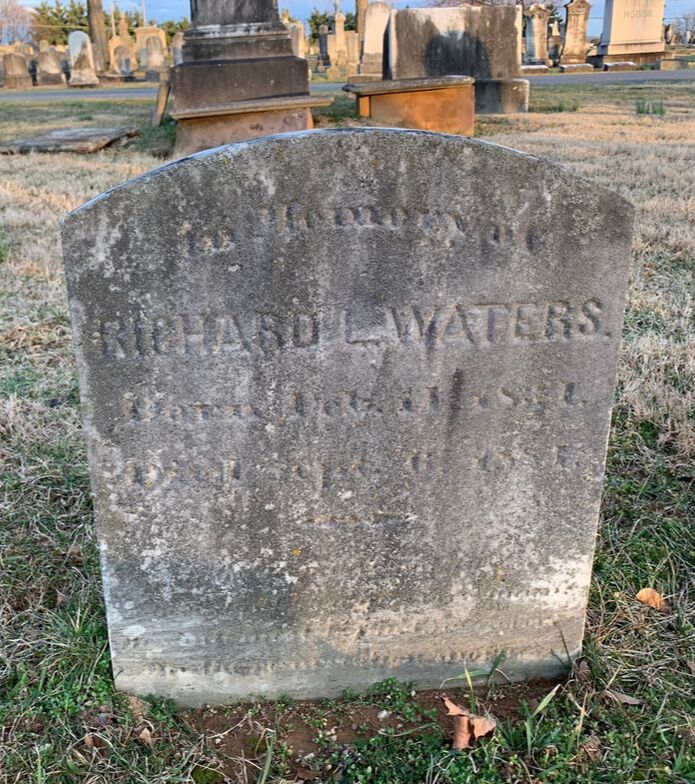

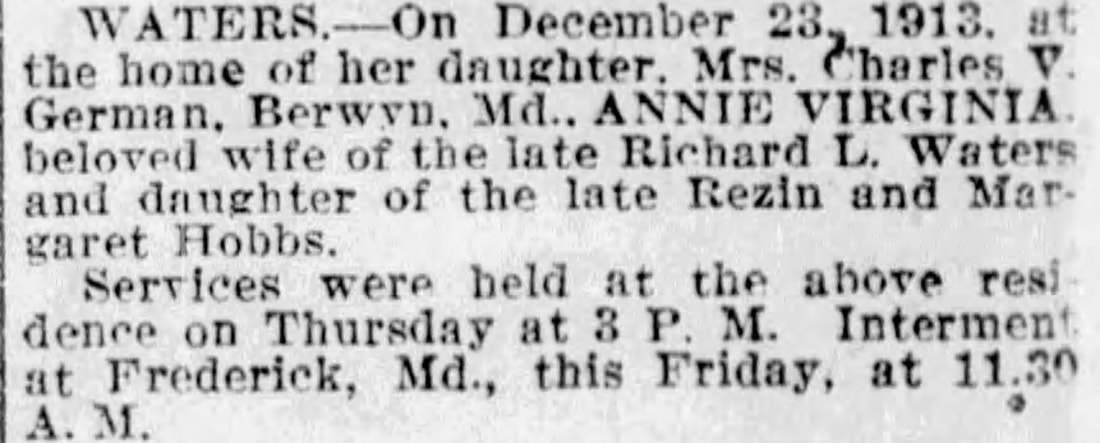

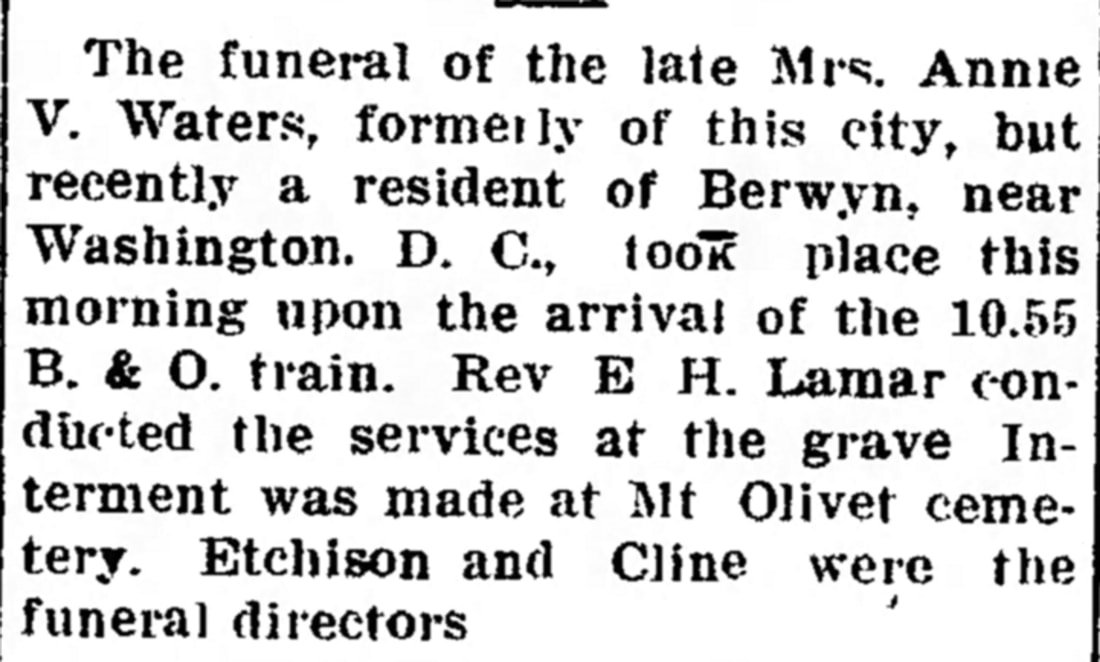

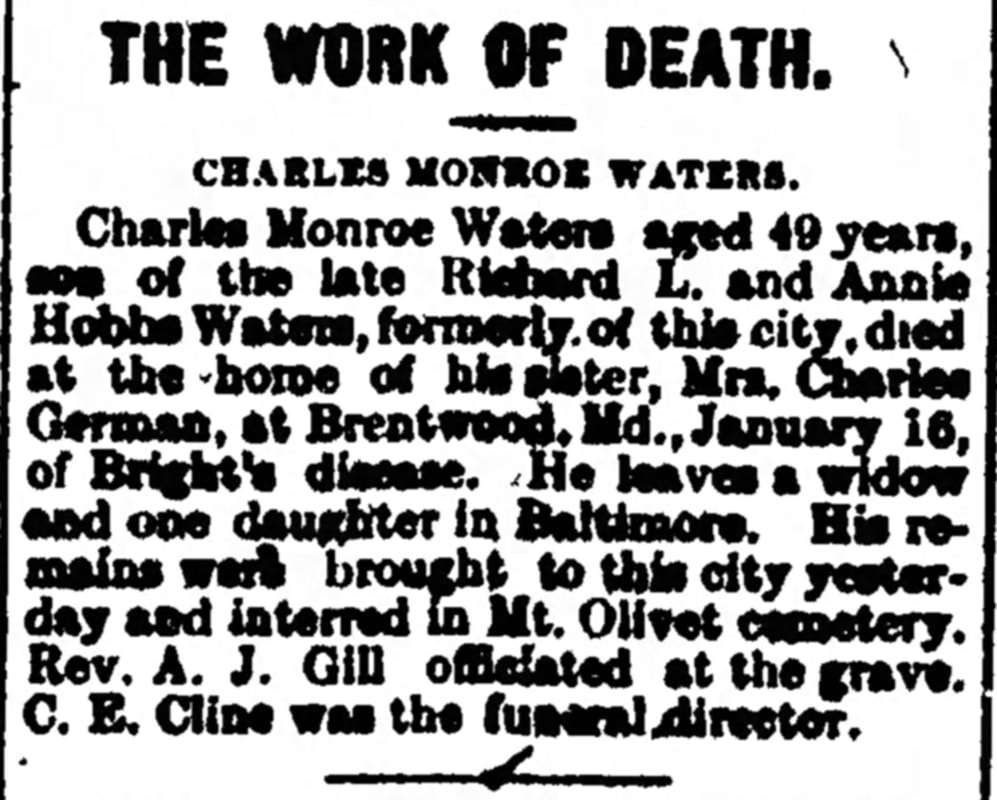

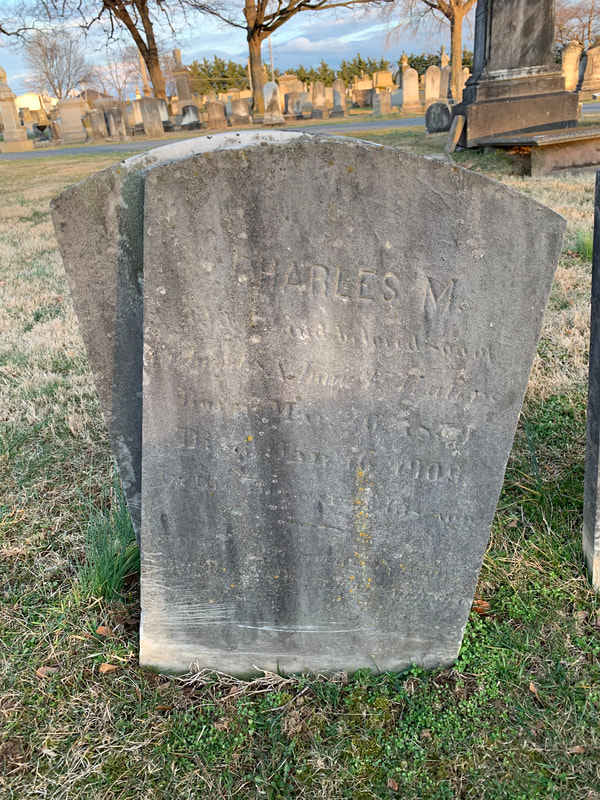

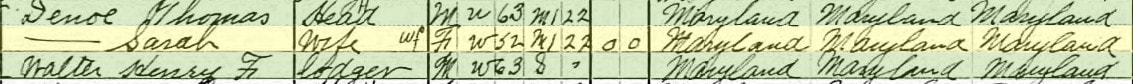

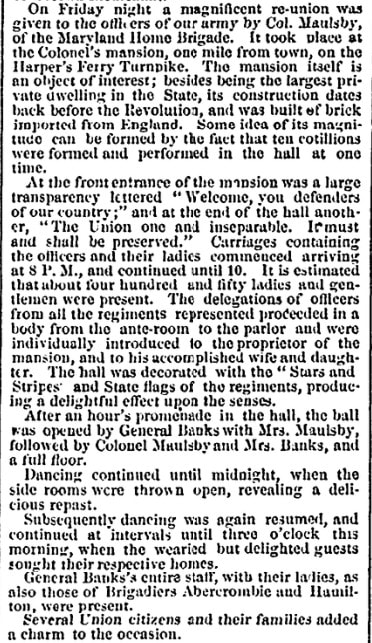

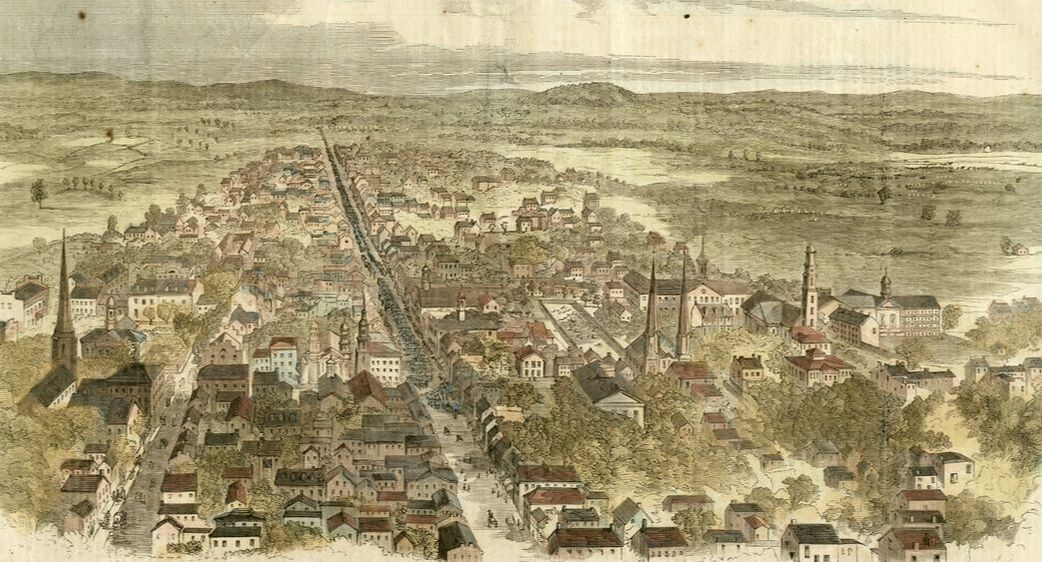

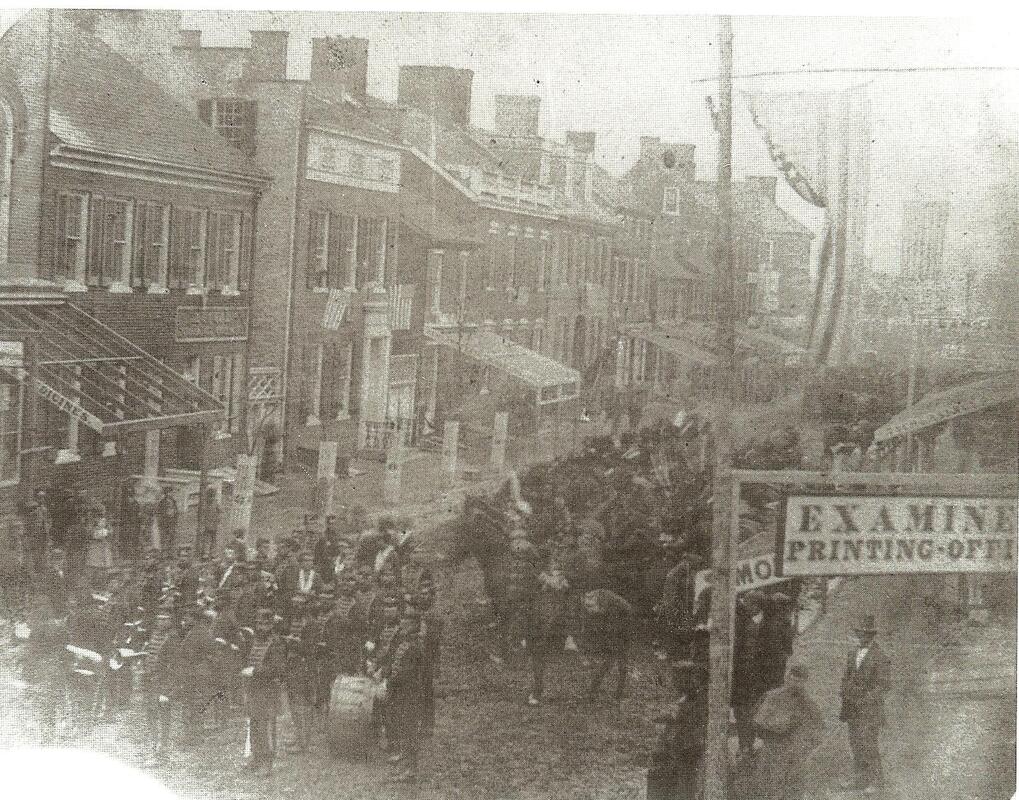

Richard L. Waters was duly buried in the Hobbs family plot in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 139, alongside his three previously deceased daughters. The “sharp-tongued” Ann Waters would live until 1913, dying in Berwyn, MD. Brat number two, Charles Monroe Waters, grew up and eventually worked as a foreman for the American Can company in Baltimore. In 1880, he married an Irish immigrant named Catherine and had two daughters and two sons. When Charles died in January of 1909, he was living in Brentwood, MD in Prince Georges County. His body was brought to Frederick to be buried beside his father and sisters. Sarah Margaret Waters, “Maggie,” married Thomas Edward Denoe in 1887. Interestingly, Mr. Denoe was a grocer in Baltimore and had a successful career, primarily running his store on West Baltimore Street. The couple never had any children. Maggie died in 1923 and is buried in historic Loudoun Park Cemetery in west Baltimore. Unfortunately, I could not come across a visual of the old Waters house that Lt. Shaw visited. The former house no longer exists as it was torn down long ago to make way for the new alignment of the National Pike/MD144. As many know, the original Jug Bridge collapsed on March 4th, 1942, when heavy rains and high winds caused a 65-foot span of the bridge to collapse. A few years later the stone arch bridge was demolished and little remains of it. The replacement bridge was in operation for decades until a new crossing over the river was built to the immediate south of the old bridge.  From this aerial shot of MD144 on the eastern approach to Jug Bridge over the Monocacy, the Waters homestead was located at the site of the blue swimming pool pictured above (very fitting-Waters). Below features a view from the intersection of Linganore Road and MD144 looking southwest toward the former location of the R. L. Waters residence. "Prospecting" in Frederick In early December, 1861, Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht estimated more than 16,000 Union soldiers had recently come to town and were encamped around it. They were under the command of Gen. Nathanial Prentiss Banks who set up his headquarters at the southeast corner of N. Court and W. Second streets, a few doors north of Col. Edward Shriver’s home and courthouse square. Regiments, here at that time, were not just from Massachusetts, but hailed from New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Indiana. The streets were packed with “boys in blue” as Frederick had never been so populated ever before. Unfortunately, liquor and libations got the best of many of these soldiers, far from home with time to kill. In one of his letters, Robert Gould Shaw talks about a “sobering” experience while attending a great party here in town in early January, held at a landmark structure that still stands today.

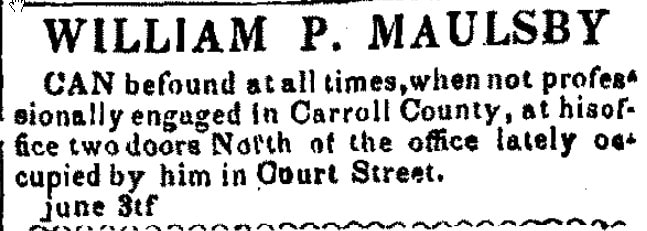

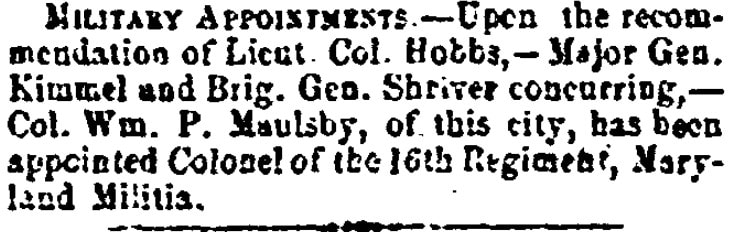

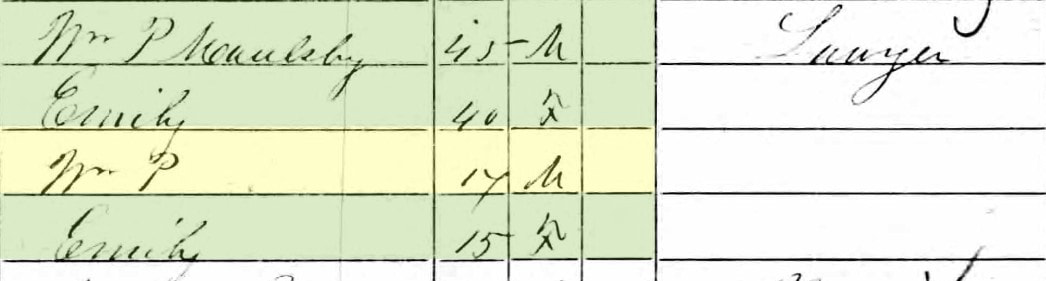

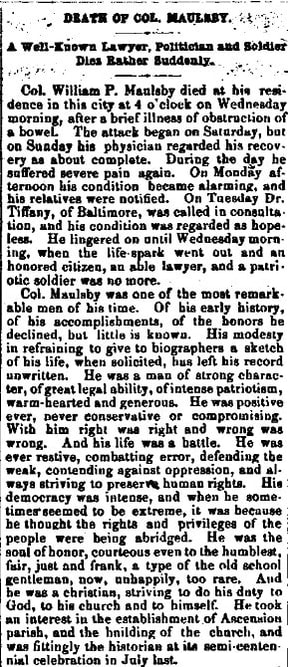

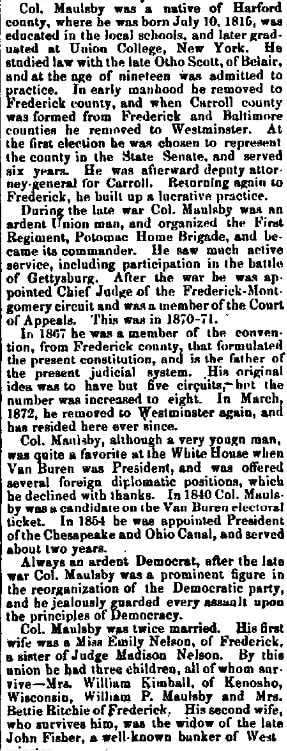

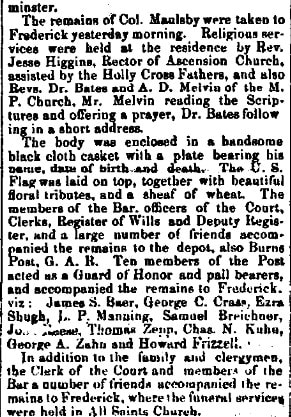

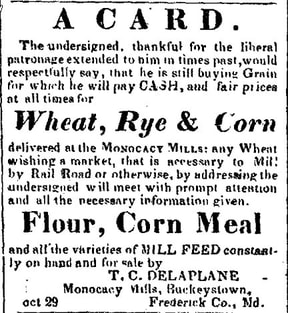

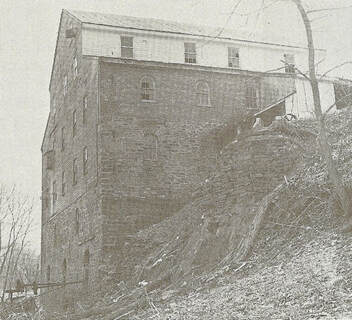

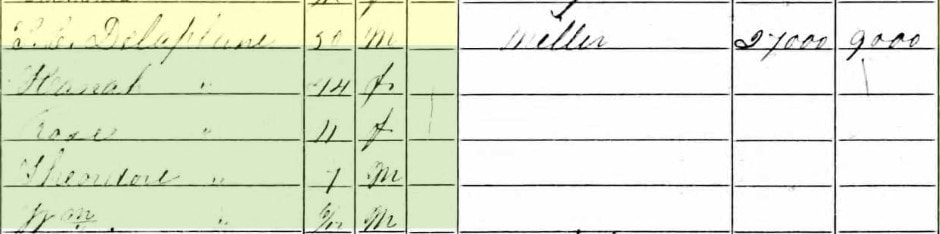

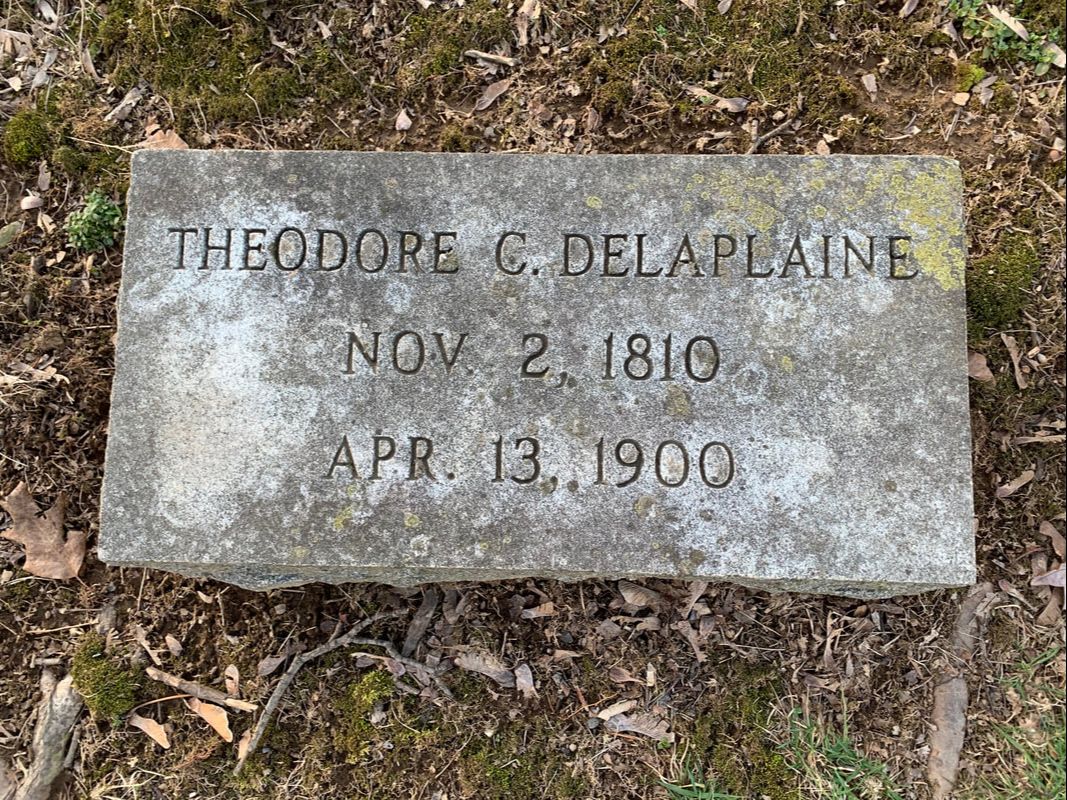

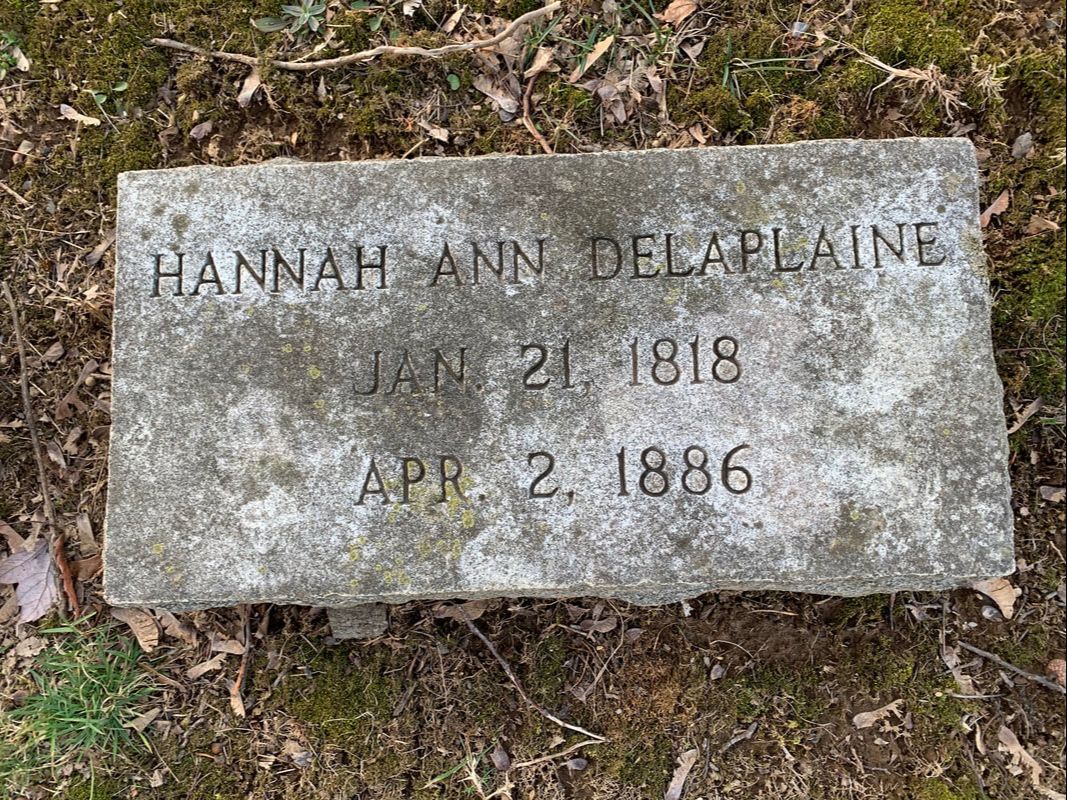

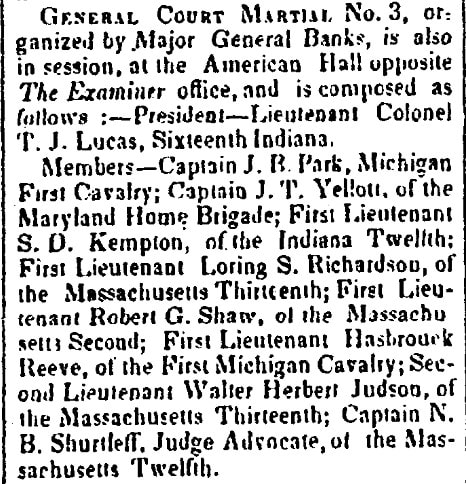

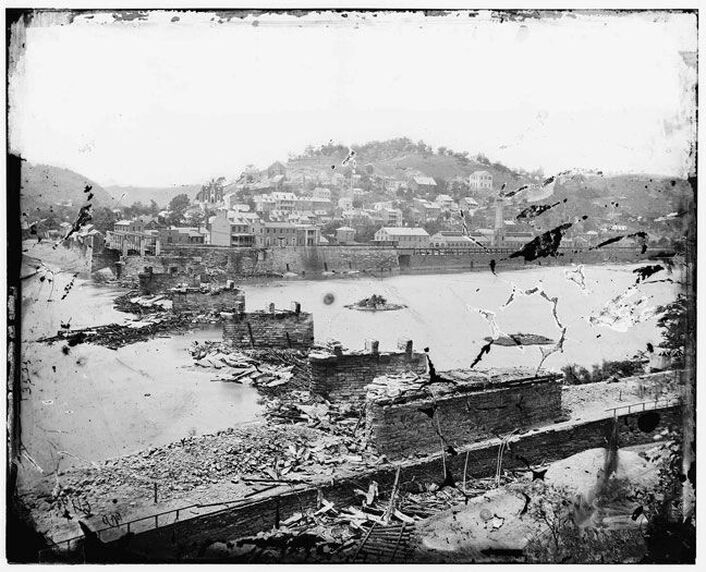

The party in question was held on Friday, January 10th (1862) at Prospect Hall, former site of St. Johns Literary Institution later known as St. John's Catholic Prep (College Preparatory School). The owner in 1862 was local lawyer William Pinkney Maulsby, Sr., born July 15th, 1815 near Bel Air in Harford County. Maulsby had been commissioned a colonel during the war and was the first commander of the 1st Potomac Home Brigade, organized at Frederick, Maryland, beginning August of 1861. It was mustered into the Union Army under Gen. Banks on December 13th, 1861. As a young man, Maulsby studied law in Baltimore under the tutelage of John Nelson (who would later go on to serve as the US Attorney General). In 1835, William married John Nelson’s daughter, Emily, and embarked on a legal and political career. You may recall a story I published a few years back about William and Emily Maulsby’s daughter Betty Harrison Maulsby (Ritchie) who was was the driving force in organizing Frederick’s first DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) chapter in 1892. Betty’s daughter, Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean would serve as President General of the national organization from 1905-1909.  Prospect Hall Prospect Hall Upon the creation of Carroll County in 1837, Col. Maulsby represented the county first as a state senator, then as a state’s attorney. By 1850, he had moved his family to Baltimore before again moving to Frederick for business and political reasons. In 1856, Maulsby purchased “Prospect Hall,” a large Greek Revival style mansion just south of the city. Prospect Hall would serve home to the Maulsby family from 1856-1864 and the location did more than host the future hero of Glory, as this would be the site where Gen. George Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac in late June, 1863. Col. Maulsby headed his regiment (Potomac Home Brigade) for three years, leading his men at Harper’s Ferry, Gettysburg, Monocacy, and countless smaller skirmishes. After leaving the US Army, he sold Prospect Hall and moved to downtown Frederick and a home on East Second Street. Despite his service to the Union, William P. Maulsby earned the wrath of many Republicans in the post-war years due to his affiliation with the Democratic party and his leniency towards the defeated secessionists. In 1866, he ran an unsuccessful bid for congress. Maulsby continued his career as a judge and eventually moved to Westminster where he died October 3rd, 1894. He is buried under a large cross monument in Mount Olivet’s Area G/Lot191. A Very Queer Old Party Lt. Shaw talked of a “party” of another kind in a letter sent to sister Effie in February, 1862. His hosts were prominent mill-owners in Buckeystown who had a son whose later printed creation would “shower good news” down on Frederick County for well-over a century. I also owe this same man homage as his direct descendants gave me my first real job, and the opportunity to work professionally in public history. Frederick Md. February 9,1862 My dear Effie, I have received two letters from you since I last wrote and I admire your constancy in writing so regularly. Susie is in Washington & I have just telegraphed to Cousin John to know if he can’t go home this way and make us a short visit. I can’t possibly go away, so if they don’t come to Frederick I shan’t see Susie at all. That would be too bad when we are so near together. Today, for the first time, I think, for five weeks the weather is fine—but it looks as if it were going to cloud over again in a little while. I have very pleasant lodgings here in a family consisting of a very queer old party, named Delaplane, and his wife. The latter has a most wonderful appetite and an extraordinary love of good dinners, the result of which is, that we live remarkably well. Capt Savage & Dr. Stone of the 2 Mass. Live here too, but will soon be going back to the regt. I am afraid I shall be rather lonely then. We have two rooms adjoining each other, one of which has a large open fire-place, which is very comfortable & cozy. I go round to the Court-Martial around 10 o’cl. A. M. and we usually get through at 2 P. M. so that I have a good deal of time to myself. I find though, that camp is the best place for me. I am always in good spirits out there—probably because it is such a wholesome life. As soon as I get a horse, I shall have a much pleasanter time here, for I have much difficulty in getting about now—especially out to camp where I want to go quite often. Robert Gould Shaw was living with Theodore Crist Delaplaine and wife Hannah (Wilcoxen) Delaplaine, proprietors of the Monocacy Flour Mill located southeast of Buckeystown along the Monocacy River. This property still exists today off of Michaels Mill Road. Mr. Delaplaine was born in Georgetown on November 2nd, 1810. Two weeks after his birth, his mother died. At this point he was taken to Frederick to live. In T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County (published 1910), shares the following anecdote about young Theodore: “On the way from Georgetown to Frederick the stage coach broke down but the little fellow was passed through a window, and was quite unharmed.” I don't know whether that means if he was thrown out of the vehicle, or simply handed out, but it piques curiousity. Young Theodore's childhood was spent on a farm near Ladiesburg and he was educated in the country schools. He got his first job at Greenfield Mills in southern Frederick County and then added to his “milling” experience and education by working at like operations in Halltown (WV), Bladensburg (MD), Georgetown (DC), Alexandria (VA), Highland and Germantown (OH), and Missouri. Delaplaine returned to Maryland and owned/operated various mills in Frederick County along with getting further instruction as an employee of the famed Ellicott Mills in Ellicott City (Howard County). In 1851, Theodore Delaplaine acquired the Monocacy Mills outside Buckeystown which he would operate successfully for the next 24 years. Williams’ History goes on to say: “During the Civil War his output reached one hundred barrels a day. The quality of his flour was excellent and much of it was sold wholesale to South America." In 1862, General Lee’s Confederate troops made a raid on Delaplaine’s mill and took seven hundred barrels of flour. The general is said to have offered to pay in Confederate money as far as he was able but, knowing that it was practically useless, Mr. Delaplaine refused the money. This story illustrates the importance of Union protection for the mill, not unlike the old Jug Bridge, as it was a prime target of the Rebels. It's no wonder the Delaplaines were so willing to provide soldiers accommodations in their humble abode.  Wm T Delaplaine Wm T Delaplaine Theodore Crist Delaplaine was married in 1848 to widow Hannah A. Wilcoxen (b. April 21st, 1818), daughter of Capt. Eden Edmonston and Lucretia Waters. And yes, Mrs. Delaplaine, through her mother's family, was a distant cousin of the fore-mentioned Richard Waters. The couple had three children: Rosanna Delaplaine (Dutrow) (1849-1883), Theodosia Waters Delaplaine (1854-1944), and William Theodore Delaplaine (1860-1895). From all accounts, these children seemed a little better behaved than those of Richard L. and Annie Waters mentioned earlier. To some of you, the Delaplaine’s youngest child’s name may seem familiar because William T. Delaplaine started the Frederick News in 1883. He would die young of pneumonia at the age of 35, leaving his four young sons to carry on the family business which was handed off to future generations. I had the great pleasure of working for, and under the tutelage of, Theodore Crist Delaplaine’s great-grandson, George B. Delaplaine, Jr. and great-granddaughter, Frances Delaplaine Randall while at Frederick Cablevision and GS Communications for 12+ years. If it wasn't for them, I likely wouldn't be writing this article for you today. Hannah Delaplaine died on April 2nd, 1885 and was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 257. The old miller, Theodore, would join his wife here five years later, dying on April 13th, 1900 at the age of 90. Theodosia is buried in this plot with her parents, and William T. in an adjoining lot. Sister Fannie (Delaplaine) Dutrow is buried in Urbana’s Zion Cemetery. Parting Words A final letter was written from Frederick by Robert Gould Shaw to his mother on February 16th, 1862. In this, he talks of calling on the prettiest girl on town, but her name is omitted in the publication. Unfortunate, as I bet she’s here in Mount Olivet, whoever she was. Shaw also speaks of attending a church service at All Saints Episcopal Church on West Church Street (Frederick) and finding himself, along with the church sexton, the only men in the building full of ladies. Sadly, Shaw ends the letter on a sour note in respect to Frederick, but one that would likely to have subconsciously fed his drive for the job ahead that he was destined for: “How do you feel about the good news from the South and West? All I want or wish for this week is to hear that Fort Donelson and Savannah are taken. Next week I should like to have Burnside take Norfolk. I am very much afraid, though, that we shan’t have such a run of luck as that. Some of the Secession people here were enraged at the news. I heard one girl say to another, when I was standing near them in the street, 'I like a nigger better than a Massachusetts soldier!' This same young person turns up her nose, and makes faces, whenever she meets us riding or walking. Most of the Secession ladies, though, have good enough manners to refrain from any such demonstrations. Love to Father, Anna, and Nellie. Ever your loving son, Robert G. Shaw All of Shaw's wishes would come to fruition: Fort Donelson and Savannah were captured within days, and Gen. Ambrose Burnside would have full control over Norfolk within weeks after the March 8th ironclad showdown in the Battle of Hampton Roads in which the Union's USS Monitor defeated the Confederate CSS Virginia (aka the Merrimack). This fully opened the area to serve as a base of operations for Gen. Burnside to launch an expedition on North Carolina's coast. Outside of these letters, the only proof of Shaw’s presence in town is within a small article that appears in the Frederick Examiner newspaper on February 19th, 1862. The lieutenant’s name is mentioned with others who made up a court-martial tribunal that was meeting in the newspaper’s office. Today this exact location is better known to Fredericktonians as The Orchard restaurant on the southwest corner of North Market and West Church Streets. On February 22nd, 1862, George Washington’s birthday was celebrated in fine form here in Frederick, complete with a grand review of the Union Army on Market Street. We are lucky to have a few photographs of that momentous occasion in the archives of Heritage Frederick (the former Historical Society of Frederick County). One was taken just outside the previously mentioned Examiner Building. The grand marshal was Col. Edward Shriver with whom Shaw had spent time while here. Could Robert Gould Shaw be pictured among the Union men captured in the photographs on Market Street? We’ll never know. On Sunday, February 22nd (1862), resident Jacob Engelbrecht penned in his diary the following passage: “Today Washington’s birthday was celebrated by the people of Frederick by the ringing of bells & firing of cannon by the military. Two flags were presented by the ladies of Frederick to the First Maryland Regiment under Colonel William P. Maulsby. The presentation was made by James T. Smith & received by William P. Maulsby. Addresses made by both. The different regiments in our neighborhood were present on the occasion numbering 4 or 5,000 who paraded through the streets. The presentation was made at the veranda of the Junior Hall where nearly all the staff officers were. Major General N. P. Banks, Colonel Geary, General Abercrombie, &c were present. After the presentation the “Star Spangled Banner” was sung—led by William D. Reese. And Mrs. General Banks sung in style. Among the singers your humble servant was among the singers and I would remark that I sang the same old “Star Spangled Banner” a few weeks after it was composed say about October 1814.” The next day, Lt. Shaw and his regiment were given orders to be ready in one hour’s notice, with three day’s cooked rations, and cartridge boxes filled. A fellow soldier from Massachusetts, named Henry Newton Comey, wrote in a letter: ”The wagons started off immediately as did the artillery and pontoons. We expected to leave about that time as well, but alas we did not. We later heard that the pontoons, floated by canal from Washington, were too wide for the canal locks at Harpers Ferry, and could not get into the river. Our departure came on February 27th, when we abandoned Camp Hicks after breakfast. At 4:00am, the 2nd, Rgt. Slogged through the wet boggy ground which laid between the camp and the road, and marched into Frederick. From there we took railway cars southwest to Sandy Hook.” At this point the regiment crossed the Potomac and spent the night in the empty houses on Shenandoah Street (Harpers Ferry). Over the next seven months, Shaw fought with his fellow Massachusetts soldiers in the first Battle of Winchester, the Battle of Cedar Mountain and at the bloody battle of Antietam. Robert Gould Shaw served both as a line officer in the field and as a staff officer for Gen. George H Gordon. Twice wounded, by the fall of 1862 he was promoted to the rank of captain. It’s fascinating to think that Shaw walked the streets of Frederick. He would have traveled by Mount Olivet regularly, and I’d bet money that he strolled through Mount Olivet at least once. If anything else, we have several folks interred here that shared conversation, libations, meals and social interaction with this brave young soldier, destined for "Glory." If you've never seen the movie of the same name (Glory), please make a point to watch as you will witness Shaw's promotion to the rank of colonel and the rest of his amazing story--one shared with the brave men of the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Ironically, Col. Robert Gould Shaw doesn't have a marked gravesite. He was buried in a mass grave at Fort Wagner, South Carolina along with his fallen troops. He is remembered in his hometown with the famous bronze-relief sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and located at the edge of Boston Common. Shaw also is honored with a cenotaph in nearby Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

2 Comments

Nancy Droneburg

3/7/2020 11:35:42 am

Excellent

Reply

Ronald Washington

12/18/2021 12:04:59 am

I live on Staten Is and represent the Shaw family (Google my name and Col. Shaw) I am not sure of your reasoning for referring to Colonel Shaw as "Henry Gould Shaw" ??

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed