|

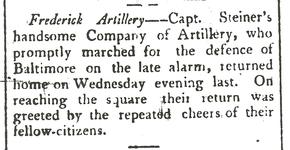

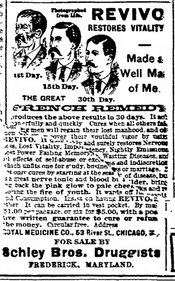

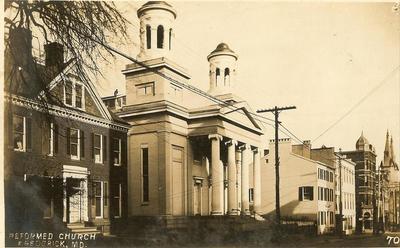

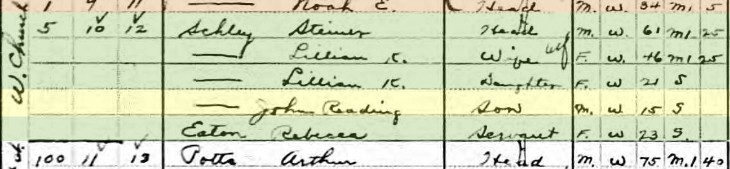

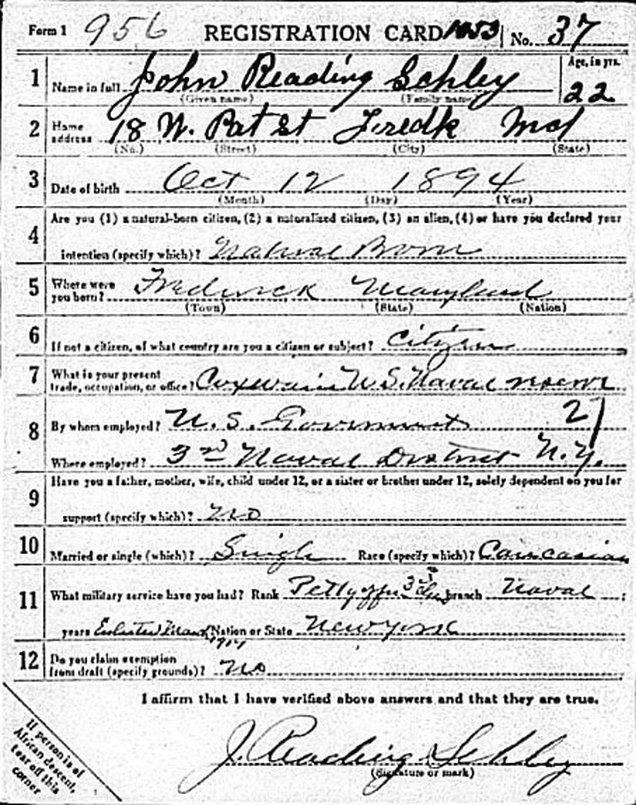

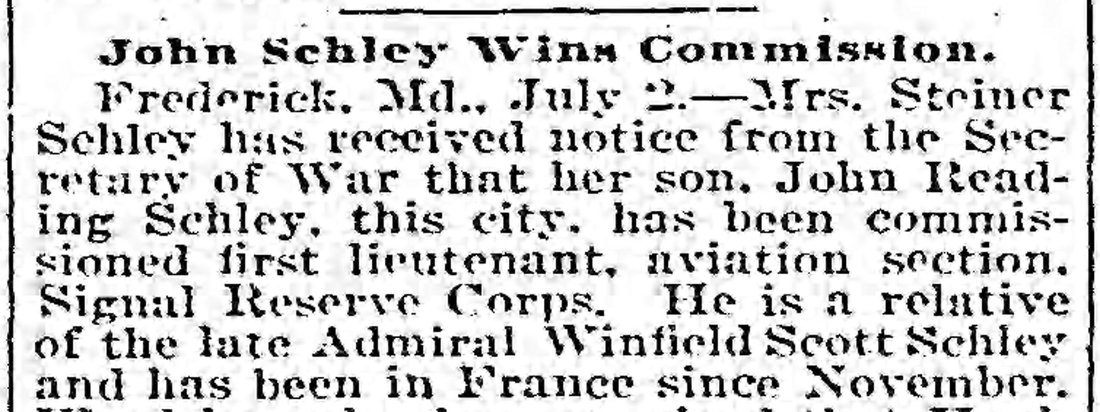

Frederick, Maryland has always taken great pride in its rich German roots. The area north of Frederick City is commonly known to genealogists and historians as the Upper German settlement. Frederick itself was named after a German prince from the House of Hanover. This was likely done as a “marketing ploy” to attract hard-working, frugal and God-fearing people—ones who soon showed that they were willing to escape the hardships of their homeland, for the opportunity to make a new life in the “New World.” Many of the earliest inhabitants of today’s Frederick County would come via Pennsylvania’s recently established Dutch country (Hanover, York, Lancaster areas). This first occurred in the mid 1700’s. Frederick Town, itself, was laid out in 1745 as a planned community on the western frontier of the Maryland colony. Founder Daniel Dulany sent circulars advertising the many benefits of settling here. These went to Germany (then a confederation of states) itself, and, naturally, had distribution and testimonials targeting those who had already migrated to William Penn’s colony. Two of the earliest German families to settle in Frederick were the Schleys and the Steiners. Both fill the local history books as pillars of the community through a multitude of endeavors, particularly civic leadership and the field of medicine. John Thomas Schley is reputed to have built Frederick Town’s first house, had the first native-born child and became the first schoolmaster (affiliated with the German Reformed church). Meanwhile, Jacob Steiner (Stoner) constructed the legendary Mill Pond house north of the town (proper) and built/operated the first principal inn at the southwest corner of the Square Corner (intersection of Market and Patrick streets).  Frederick Town Herald (October 1, 1814) Frederick Town Herald (October 1, 1814) In addition to being savvy business people, these two families are also known for their patriotic contributions. There was participation in the American Revolution. The grandsons of Jacob Steiner were Frederick's respective leaders of local militia units in the War of 1812: Stephen Steiner (infantry) and Henry Steiner (artillery). Both participated in the "Star-Spangled" defense of Baltimore. Henry’s grandson, Dr. Lewis H. Steiner, made a name for himself through his leadership of relief efforts put forth by the United States Sanitary Commission. He rose quickly through the ranks of the commission to become Chief Inspector for the Army of the Potomac.  Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley (1839-1911) Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley (1839-1911) Admiral Winfield Scott Schley was the GGG-grandson of John Thomas Schley, and enjoyed a much-decorated career in the United States Navy. After graduation from the Academy in Annapolis, he served during the Civil War. His greatest moment came more than three decades later in Santiago, Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Here, Schley commanded Admiral George Dewey’s flagship “the Brooklyn.” Ahead of the main squadron, “the Brooklyn” trapped the entirety of the Spanish fleet with Santiago Harbor, meanwhile exposing itself to a monstrous barrage of fire. Schley’s US comrades used this opportunity to successfully destroy the entire Spanish Fleet. This resulted in the cutting off of valuable aid and support to Spanish land troops who were currently doing battle with Teddy Roosevelt and his Roughriders.  Newspaper advertisement for Schley Bros. Druggists from Frederick News (April 10th, 1895) Newspaper advertisement for Schley Bros. Druggists from Frederick News (April 10th, 1895) Both families (Steiner and Schley) collided in 1847 with the wedding between local druggist Dr. Fairfax Schley and Anna Rebecca Steiner. The couple had four children—the oldest would be named Steiner Schley. Steiner Schley (1849-1911) would learn the trade of pharmacist and continued his father's successful drugstore business in town. He also tinkered in other endeavors, including his tenure as a longtime Board of Visitors member of the Maryland School for the Deaf, and is credited with building the Monocacy Valley Railroad, a four-mile track that connected the Western Maryland Railroad’s main line with Catoctin Furnace. He also served in the boards of the Central National Bank and the Mutual Fire & Insurance Company. Although Dr. Steiner Schley missed serving in active military duty over his lifetime, his son John would eagerly enlist in America’s first conflict against Germany—the country from which his Schley and Steiner ancestors hailed. This was certainly a conflicted time for some local residents boasting Dutch heritage, while others would recount the reason their families had originally left Germany, be it in the 1700’s or 1800’s. John Reading Schley holds the distinction of becoming the first Frederick Countian to become a military pilot. He joined the US Army air service in World War I, just 14 years after the Wright brothers had made their legendary first-powered flight of 1903. Born in Frederick City on October 12th, 1894, John Reading Schley was the son of Lillian F. (Kunkel) Schley-daughter of one-time Catoctin Furnace owner John Baker Kunkel. Through the Kunkels, young John could trace lineage to namesake John Reading, one of the Colonial-era governors of New Jersey and among the founders of Princeton University. Somehow along the way, John Reading earned the nickname of “Slip.”  The Steiner Schley family lived at 5 W. Church St, located immediately to the right of Evangelical Reformed Church The Steiner Schley family lived at 5 W. Church St, located immediately to the right of Evangelical Reformed Church As a boy, John Reading Schley became a member of Evangelical Reformed Church of Frederick, formerly known simply as German Reformed. The family lived directly next door to the east at 5 W. Church Street. John spent several summer vacations at a YMCA camp on Lake George, New York and conducted by one of the leading secretaries of the organization. Early education was attained at the Frederick Academy (Frederick College), from which Schley graduated in 1912 at the head of the class. He was known as a hard-working student and expert debater. Schley's father passed away at the age of 61 in 1911 after a six-month fight with pancreatic cancer. This prompted his mother to move with 17-year-old John and sister Lillian. They sold their fine townhouse and took up residence a block south in an apartment located at 18 W. Patrick Street. John eventually completed his preparatory course at Mercersburg (PA) Academy in 1915. Described as “strong, and well built,” he excelled in athletic sports, while being highly popular with classmates. Above all, his associates said “he was high-minded and honorable.” In the autumn of 1915, "Slip" Schley entered Lehigh University, expecting to take a four year-course track in electro-metallurgy. He soon was initiated into Sigma Phi fraternity. At the end of his freshman year, trouble with his eyes caused him to postpone studies, taking up work in one of the foundries in South Bethlehem, PA. One year later, he found another calling as the US Congress voted to enter what was then the largest, and bloodiest, war in history on April 6th, 1917.  John Reading Schley went to a recruiter’s office on April 12th (1917) and enlisted in the New York Naval Reserves as a coxswain on a submarine chaser. He apparently became weary waiting to be placed on active duty. At his request, he was transferred to the Aviation Signal Corps Service at Fort Myer, VA, on August 18th, 1917. From here, Schley was then sent to the United States School of Aeronautics at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He received his diploma as “flying cadet” from the Atlanta-based institution on October 19th, 1917. One week later, John Reading Schley was sent to France to be trained to fly. This was the war that boasted the early flying aces, using single seat biplanes such as France’s Nieuport models and Britain’s Sopwith Camel. This was also the era of the immortal Manfred von Richthofen, known more commonly as “the Red Baron.”

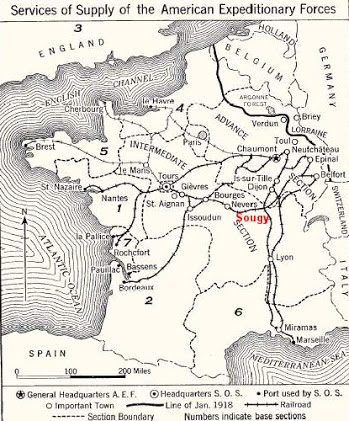

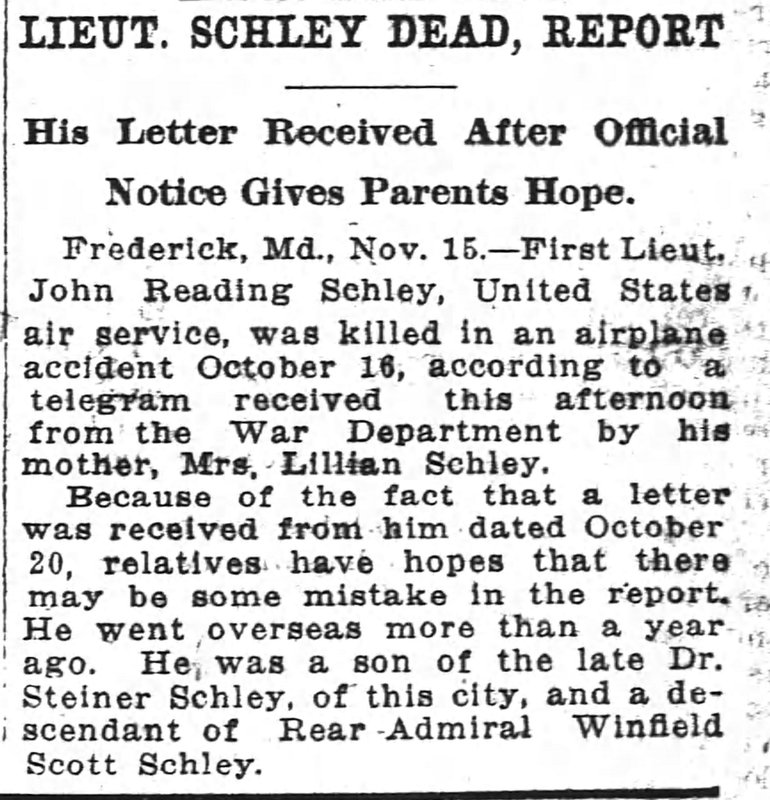

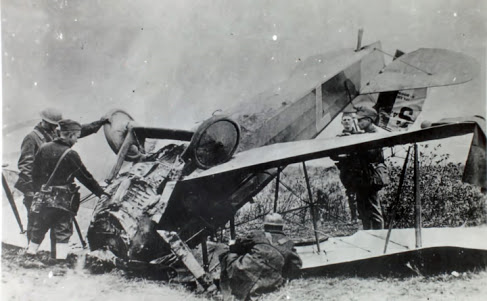

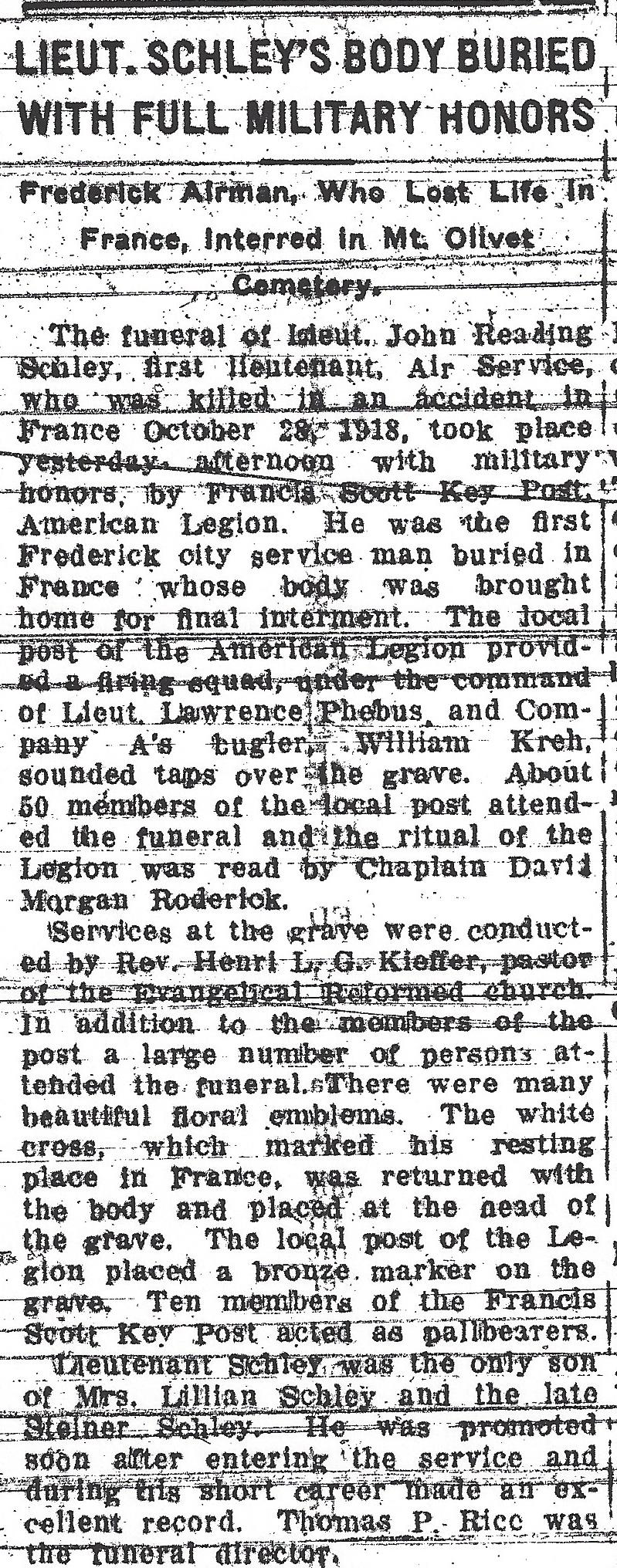

In mid-October (1918), Schley was granted leave to be spent on the Mediterranean in the luxurious French Riviera (southeast part of the country). He had been ill, and this furlough was thought to help him make a full recovery. Upon his return, he hastily resumed advanced training flights at Issoudun. He wrote a letter home on October 20th to his mother and sister. In hindsight, it is thought that he may not have been well-enough to resume the rigorous training schedule. Unfortunately, Schley would never get his chance to make the history books with wartime gallantry like so many of his ancestors. He would lose his life on a cross-country flight that commenced on October 22nd, 1918, 20 days before the war’s end. Lt. Schley was only 24 years old. A fellow-cadet, who originally befriended John Reading Schley at Mercersburg, wrote a letter home to friends of the Schley family. This gave further information to a scant and misleading telegram that reached Frederick and Schley's mother and sister with news of his death. The classmate's letter stated that “He (Schley) died a mighty clean and noble death. He was on his advanced training and was doing well, but on a cross-country flight something went wrong and he fell from a great height.” Military records report that Schley actually suffered a heart attack and lost control of his airplane on that fateful day. He was said to have drifted for a while, before hitting the ground. The young aviator was found unconscious and immediately taken to a hospital. He died and was buried in a military temporary cemetery on the grounds of the 3rd Aviation Center at Issoudun. Two years later, his body would be dis-interred and sent back home to his hometown of Frederick for reburial. Accompanying his remains, was the “military issue” marble cross that had marked his original gravesite. John Reading Schley would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet on November 20th, 1920 with full military honors. He holds the distinction of being the first military pilot from Frederick County. He is also the first Frederick serviceman buried in France whose body was brought home for final interment. Meanwhile, many of his Issoudun comrades were moved to the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery (France). For a number of years afterwards his grave would be decorated by the American Legion Auxiliary on Armistice Day (November 11). Across the Atlantic Ocean and "Over There," a monument was erected in the 1920’s near the Issoudun base, bearing the names of 171 Americans who died at the U.S. training facility during the war. Between 1917 and 1919, some 7,500 Americans were stationed at the 3rd Aviation Instruction Center of the United States—which included seven camps, 11 landing fields, and two field hospitals. Many of the fatalities resulted from flight training accidents. American participation in “the Great War” lasted only a year and a half, but in that time, an astounding 117,000 American soldiers were killed and 202,000 wounded. By the time of the Armistice, 766 pursuit pilots had completed their training at Issoudun, of whom 139 were retained as testers, staff pilots and instructors. The remaining 627 were sent to the Zone of Advance. 171 Americans died here in training accidents.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed