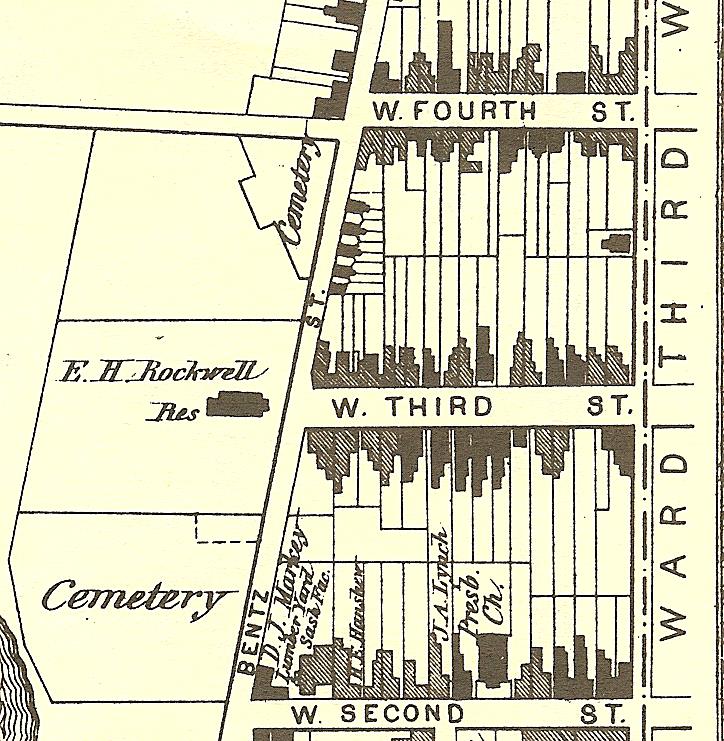

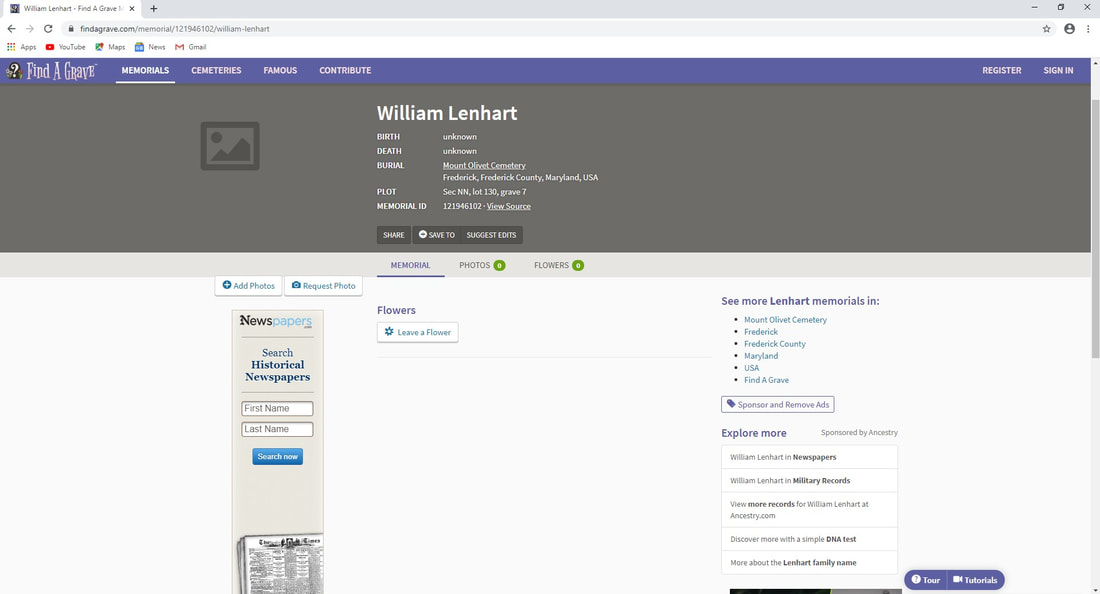

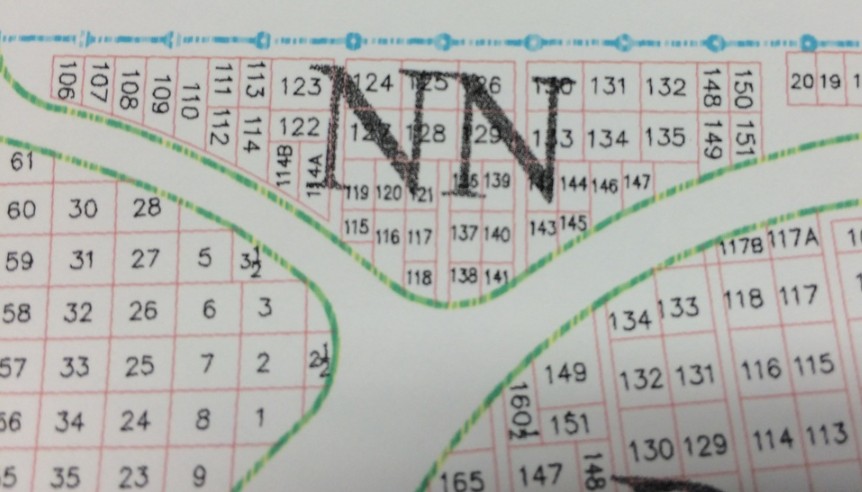

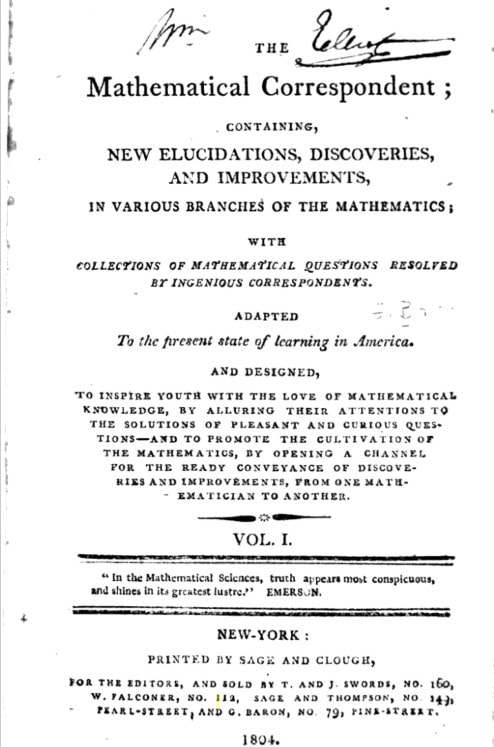

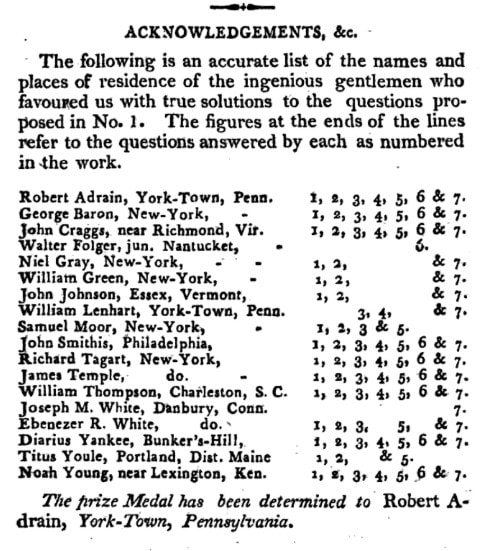

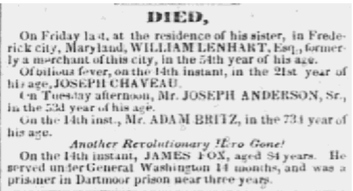

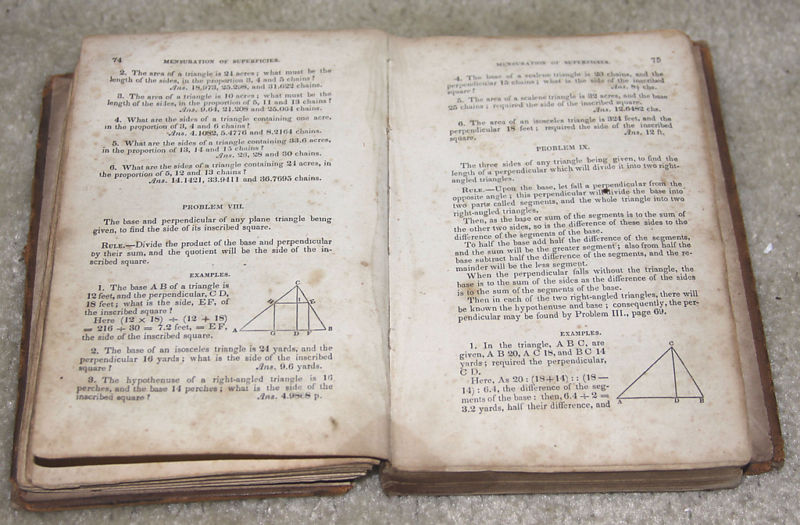

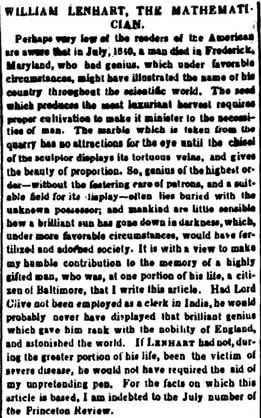

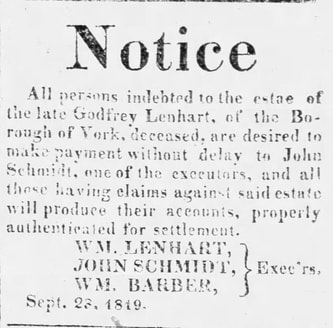

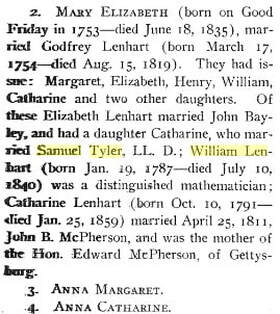

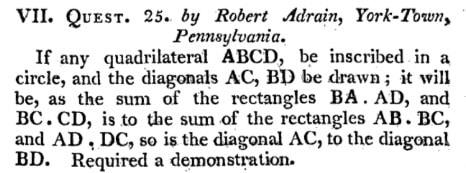

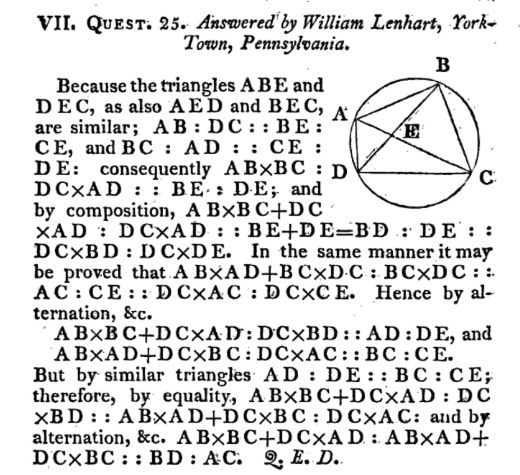

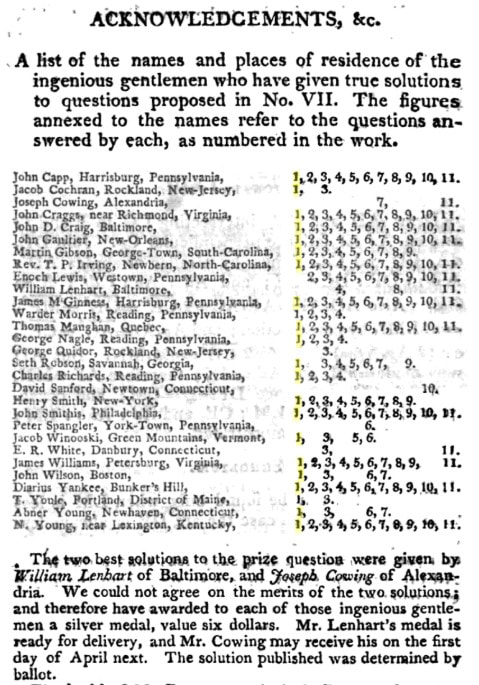

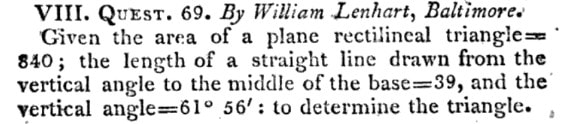

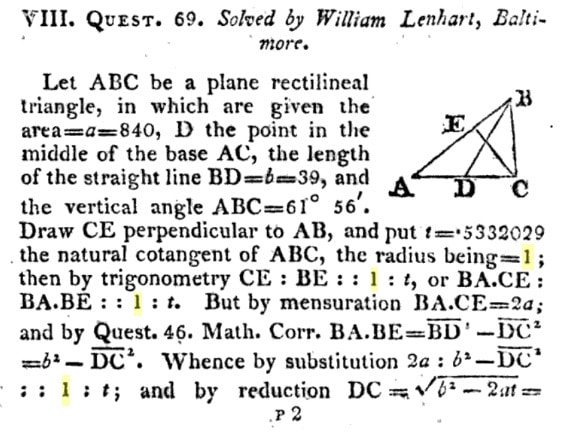

Well, with St. Valentine’s Day having recently hit us again, it’s nearly impossible to avoid images of hearts, roses, greeting cards and candy—specifically chocolate . And with the latter, the most popular chocolate chosen for this commercially-hyped day of “love-reckoning,” isn’t the typical household variety such as Hershey Bars, M & M’s or Reeses Cups (my personal favorite). No, no, no, we’re talking the “top shelf” stuff, packaged of course in box form, with an assortment of delicacies. Whether it’s a familiar name like Godiva, Lindt, Whitman’s or Russell-Stover, I’m always reminded of the legendary line from Forrest Gump—“Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.” However, when it comes to candy, I think I’d be more satisfied sometimes with plain ol’ Reeses Cups—but it’s the thrill of the quest, I guess, that makes boxed-chocolate something exciting. As I near my four-year anniversary working for Mount Olivet, I reflect upon the great satisfaction I've had in writing these “Stories in Stone” blog articles—this is number 140. The most gratifying part of it for me can also be explained by that Forrest Gump quote, however with one simple difference by interchanging the word life with the word death--“Death is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.” A few years ago, I wrote the following to describe my articles: “They are essays about former Frederick residents buried within Mount Olivet’s gates. Yes, some of these individuals stand out for their achievements. Others can be remembered for misfortunes. All in all, most of those “resting in peace” just lived simple, ordinary lives. To borrow a line from George Bailey in Frank Capra’s legendary film It’s a Wonderful Life: “Just remember Mr. Potter, that this rabble that you’re talking about...they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community.” We can just assume that the people here that you've never heard of before, simply lived ordinary, average lives. However, I have found that not to be the case, over and over again. That point hit home again last weekend while falling into a subject topic by pure accident. It is the genesis for this story here. I had been researching online within old Virginia newspapers of the early 1800s in hopes to learn more about my previous "Story in Stone" profile, artist John J. Markell. Out of the blue, a front- page article in the Staunton Spectator and General Advertiser caught my eye. Under the bold headlines MIscellany and Interesting Biography, appeared an extensive, two-column ode to a gentleman named William Lenhart, the Mathematician. Mr. Lenhart apparently had been living in Frederick, Maryland, before his death at the same place in the summer of 1840. I was certainly intrigued by seeing the words “Frederick, Maryland” in the story, and much more than I was in seeing “mathematician.” I’ll be the first person to tell you that I love numbers, especially as they pertain to history—dates, population totals, ages, casualty numbers, etc. I don’t mind basic arithmetic and entry-level statistics, but higher math in its various forms (ie: algebra, geometry, trigonometry, calculus, number theory and mathematical physics) scares the hell out of me. It’s a good thing I married a high school math teacher, who, ironically, has very little use, or interest, for history. “The Math Guy” With 40,000 former residents in my midst at Mount Olivet, roughly the same population as our state capital of Annapolis, I still pass countless gravesites without a thought, as their names are still nothing more than “names in stone.” With that said, I was certainly hoping that William Lenhart was possibly one of our own since he lived, and died, in Frederick back in the early 19th century. One minor conundrum was knowing that Mount Olivet opened in 1854, 14 years after Lenhart’s death. However, many of those early Frederick residents that had been buried in the existing church-owned graveyards of that era, would eventually be moved to Mount Olivet by the early 1900s. When I found that article in the Staunton newspaper, I was at home with no immediate access to Mount Olivet’s interment database. I will share a tip here with those finding themselves in the same predicament of wanting to check if someone is buried in a certain cemetery or not. Simply search the inventory of a particular burying ground on the www.FindaGrave.com site via the internet. It’s certainly not “fool-proof,” as some graves haven’t been added yet by hard-working volunteers, but generally most gravesites are included that have markers. In respect to Mount Olivet, here’s some basic math: our Find-a-Grave page shows that 34,058 interments have been added—that’s 73%! I simply typed "Lenhart" into the name search option and found the following result as part of a long list of Lenharts. Normally, I would be very disappointed to find this result. However, with this particular research mission, I became ecstatic because just in the sheer fact of getting this return, I now knew that there was a statistical chance and probability of William Lenhart, (Mathematician) being buried in our cemetery. Although there were no birth or death dates listed here, and no photo of tombstone (if one at all), I held optimism because here was a William Lenhart that could be him. I wish I could tell you the odds at the outset of this being a perfect match, but I already painfully divulged my math deficiencies earlier. Another source of delight for me (in looking at the scant Find-a-Grave entry for William Lenhart) was the fact that his grave location was listed as Area NN/Lot 130/Grave 7. This particular area is shaped somewhat like a small triangle on the cemetery’s western perimeter, only about 30 yards from the landmark Barbara Fritchie and Thomas Johnson monuments in the middle of Mount Olivet (in Area MM). Here, three local church congregations of yore bought property around 1907 and made arrangements to move bodies from former downtown churchyards. Interments from Frederick's former Methodist graveyard (once located at the SE corner of E. 4th St and Middle Alley) occupy the south side of the triangle (left). Evangelical Lutheran holds the center of NN, with these bodies coming from the second burying ground of the congregation, once located on the SE corner of E. Church Street extended and East Street (today's Everedy Square vicinity). Frederick’s Presbyterian Church holds the northern (right) portion closest to Confederate Row, roughly 30 yards away. In particular, bodies occupy lots 130-135 as shown on the above map section. I will tell you more on that church cemetery's history later. The William Lenhart I had just found on Find-a-Grave is shown as occupying Area NN/Lot 130, and because of this, I now knew that although loosely documented, this man had died before 1854, and had been buried elsewhere in town before being brought here. I would also soon lean that he had been previously buried in another part of Mount Olivet before coming to this current spot. Now I found the rationale to devote time to solve the problem: Does the Mount Olivet William Lenhart = William Lenhart, the Mathematician? I now had reason to read through a very lengthy article about a “math guy” in an effort to “solve my equation” or “prove my postulate” of these two being one and the same. After perusing the article, I engaged in the painful task of transcribing the lengthy two-column article for your reading pleasure. This had first appeared in print within the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser of October 2nd, 1841 (nearly a month earlier than it had appeared in the Staunton, VA newspaper). With no further adieu, here it is in its entirety as I think that this author’s presentation, although extremely lengthy and embellished, runs circles around anything I could wordsmith for telling his story:  WILLIAM LENHART, THE MATHEMATICIAN. Perhaps very few of the readers of The American are aware that in July, 1840, a man died in Frederick, Maryland, who had genius, which under favorable circumstances, might have illustrated the name of his country throughout the scientific world. The seed which produces the most luxuriant harvest requires proper cultivation to make it minister to the necessities of man. The marble which is taken from the quarry has no attractions for the eye until the chisel of the sculptor displays its tortuous veins, and gives the beauty of proportion. So, genius of the highest order—without the fostering care of patrons, and a suitable field for its display—often lies buried with the unknown possessor; and “mankind are little sensible how a brilliant sun has gone down in darkness, which, under more favorable circumstances, would have fertilized and adorned society. It is with a view to make my humble contribution to the memory of a highly gifted man, who was, at one portion of his life, a citizen of Baltimore, that I write this article. Had Lord Clive not been employed as a clerk in India, he would probably never have displayed that brilliant genius which gave him rank with the nobility of England, and astonished the world. If Lenhart had not, during the greater portion of his life, been the victim of severe disease, he would not have required the aid of my unpretending pen. For the facts on which this article is based, I am indebted to the July number of the Princeton Review. William Lenhart was the son of a respectable silversmith, of York, Pennsylvania, where he was born in 1787. His education received but little attention, until when he was about fourteen years old. Dr. Adrain,—then obscure, but since so extensively known as a mathematician,—opened a school in York, and young Lenhart became one of his pupils. Owing perhaps to the scanty means of his father, he did not remain at school more than eighteen months: yet in that short period, the rock was smitten and the waters of genius flowed out in an abundant stream. Adrain soon discovered the great mathematical talents of his pupil; and assumed towards him much of the relation of a companion in study. At this time he evinced life disposition of his mind by making in miniature, with great perfection, various machines which he had seen—fire engines, water mills, &.c. Before he left the school of Mr. Adrain, he became a contributor to the “Mathematical Correspondent,” a periodical published in New York. When he was about seventeen, he became a clerk in a store in Baltimore. I have no means of ascertaining the house in which he was placed. At that time, he was remarkable for the beauty of his person and the agreeableness of his manners. Having become tired with selling goods, he entered on the discharge of some duties in the office of Sheriff. In both these situations he was—as he continued through life—unequalled as a penman. While he remained in Baltimore, he occupied his leisure hours with reading and mathematical studies; and also made contribution to the “Mathematical Correspondent,” and the “Analyst,” published by Dr. Adrain in Philadelphia. When only seventeen, he obtained a medal for the solution of a mathematical prize question. After remaining in Baltimore about four years, Lenhart undertook the care of the books in the commercial house of Messrs. Hassinger and Reese, of Philadelphia. On account of his abilities, his employers doubled his salary at the end of the first year. His books were models of book-keeping, and the accounts he made out for foreign merchants were long kept by them as forms. As a clerk and book-keeper he was unrivalled. Such was the estimation in which he was held by the house, that after three years they offered him a partnership, by the terms of which they were to supply the capital, as his eminent personal services were considered by them as an equivalent. During this period, he cultivated mathematical science. Young Lenhart was now about twenty-four years old; and thus far his career—considering the difficulties with which he had to contend—had been one of great prosperity and promise. As to the remainder, “shadows, clouds and darkness rest, upon it.” It gives me pain to record the events of his subsequent life. When the pride of the forest is preyed upon by the worm, we are not pained by its gradual decay. The rude tempest passes by audit falls in the beauty of its foliage, the majestic oak, as it stands upon the mountain top, maybe splintered by the lightning; but our feelings of regret, as we survey the prostrate trunk, are absorbed by the contemplation of the power of the Almighty. We have different emotions when it has been scathed, and withers, and every wind of Heaven blows through its leafless branches. Deep must have been the anguish of Lenhart as he contemplated his situation, and felt that the bright prospects of his life were overcast almost as soon as the morning sun had arisen But he calmly bowed his head to the stroke; and his noble spirit enabled him to endure with a martyr’s patience, that which in the amount of suffering surpassed the torture and the flame. Before Mr. Lenhart entered upon his duties, as a partner in the house of Messrs. Hassinger and Reese, he made a visit to his father at York. While taking a drive in the country, his horse ran away, breaking the carriage and his leg was fractured. After his recovery he returned to Philadelphia. While pitching quoits he was attacked with excruciating pain in the back, and partial paralysis of the lower extremities. He was under the care of Drs. Physick and Parish for eighteen months; and after they had exhausted all their skill, they told him his case was hopeless. The injury he sustained, when thrown from his carriage was probably the cause of his spinal affliction. Had any other circumstance been required to make his cup of misery overflow, it would have been derived from the fact that he was at this time engaged to be married to a most interesting young lady; they having been mutually attached from early life. His sufferings during the subsequent sixteen years were indescribable: the intervals of pain being employed with light literature and music. In the latter art he made great proficiency, and was supposed to be the best chamber flute player in this country. He composed variations to some pieces of music, expressive of the anguish produced by the disappointment of his fondly cherished hopes of domestic happiness: and these he would perform with such exquisite feeling as deeply to affect all who heard him. In 1828, having so far recovered as to walk with difficulty—he again fractured his leg by a fall. His sufferings at this time were almost too great for human nature lo endure. From this period the greater portion of his time was passed with a sister in Frederick, Maryland. The progress of his disease paralyzed his lips, and he could no longer amuse himself by playing on the flute: and as light literature did not give sufficient employment to his active mind, he relieved the tedium of his confinement by the pursuit of mathematical science. It was under such unfavorable circumstances that he made those advances in abstruse science which have conferred immortality on his name. A year before his death he thus wrote to a friend: the beauty of the sentence will be appreciated by the mathematical reader :—“My afflictions” he says “appear to me to be not unlike an infinite series, composed of complicated terms, gradually and regularly increasing—in sadness and suffering—and becoming more and more involved; and hence the abstruseness of its summation; but when it shall be summed in the end, by the Great Arbiter and Master of all, it is to be hoped that the formula resulting, I will be found to be not only entirely free from surds, but perfectly pure and rational, I even unto an integer.” From 1812 to 1828, Mr. Lenhart was oppressed to such a degree by complicated afflictions, that he did not devote his attention to mathematical science. After the latter period, he resumed these studies, for the purpose of mental employment; and contributed various articles to the mathematical journals. In 1836 the publication of The Mathematical Miscellany was commenced in New York: and his fame was established by his contributions to that journal. I do not design to enter on a detail of his profound researches —He attained an eminence in science of which the noblest intellects might well be proud; and that too as an amusement, when suffering from afflictions which, we might suppose, would have disqualified him for intellectual labor. It will be sufficient for my purpose to remark, that he has left behind him a reputation as the most eminent Diophantine Algebraist that ever lived. The eminence of this reputation will be estimated when it is recollected that illustrious men—such as Euler, Lagrange and Gauss—are his competitors for fame in the cultivation of the Diophantine Analysis. Well might he say that he felt as if he had been admitted into the sanctum sanctorum of the Great Temple of Numbers, and permitted to revel amongst its curiosities.  Dr. Robert Adrain (1775-1843) Dr. Robert Adrain (1775-1843) Notwithstanding his great mathematical genius, Mr. Lenhart did not extend his investigations into the modern analysis and the differential calculus, as far as he did into the Diophantine Analysis. He thus accounts for it:—“My taste lies in the old fashioned pure Geometry, and the Diophantine Analysis, in which every result is perfect; and beyond the exercise of these two beautiful branches of the mathematics, at my time of life, and under present circumstances, I feel no inclination to go.” The character of his mind did not entirely consist in its mathematical tendency, which was developed by the early tuition of Dr. Adrain. Possessed as he was of a lively imagination—a keen susceptibility to all that is beautiful in the natural and intellectual world—wit and acuteness—it is manifest that he wanted nothing but early education and leisure to have made a most accomplished scholar. He was also a poet. One who knew him well says:—“He has left some effusions which were written to friends as letters, that for wit, humor, sprightliness of fancy, pungent satire, and flexibility of versification, will not lose in comparison with any of Burns' best pieces of a similar kind.” Mr. Lenhart was very cheerful and of a sanguineous temperament; full of tender sympathies with all the joys and sorrows of his race, from communion with whom he was almost entirely excluded. Like all truly great and noble men, he was remarkable for the simplicity of his manners. That word, in its broad sense, contains a history of character. He knew he was achieving conquests in abstruse science, which had not been made by the greatest mathematicians; yet he was far from assuming anything in his intercourse with others. During the autumn of 1839, intense suffering and great emaciation indicated that his days were almost numbered, His intellectual powers did not decay; but like the Altamont of Young, he was "still strong to reason, still mighty to suffer.” He indulged in no murmurs on account of the severity of his fate.—True nobility submits with grace to that which is inevitable. Caesar has claims on the admiration of posterity for the dignity with which, when he received the dagger of Brutus, he wrapped his cloak around his person, and fell at the feet of Pompey’s statue. Lenhart was conscious of the impulse of his high intellect, and his heart must have swelled within him when he contemplated the victories he might have achieved, and the laurels he might have won. But then he knew "his lot forbade" that he should leave other than “short and simple annals” for posterity. He died at Frederick, Maryland, on the 10th of July, I840, with the calmness imparted by Philosophy and Christianity. Religion conferred upon him her consolations in that hour, when it is only by religion that consolation can be bestowed: and as he sank into the darkness and silence of the grave, he believed there was another and a better world, in which the immortal mind will drink at the very fountainhead of knowledge, unencumbered with the decaying tabernacle of clay, by which its lofty aspirations are here confined as with chains. The life of William Lenhart is not without its moral. Of him it may with great appropriateness be said: “Genius will be fired with new ardour, as it beholds the triumphs of his intellect over the difficulties of science, amid so many disadvantages and discouragements; and misfortune, disappointment and disease, will be reconciled to their lot, as they view the afflictions with which he was scourged from youth to the grave.''—Baltimore American. S. C. All I could say, during and after reading this, was “Wow!” My head quickly filled with several new research questions, along with potential methods to attempt to answer each. Who was this article’s author, simply referred to as “S.C.?” What more did the referenced Princeton Review article have to say about Lenhart? What exactly were Lenhart’s disabilities, and how were they caused exactly? Who was Lenhart’s sister, and where did Lenhart live in Frederick? Were there any direct heirs to Lenhart or his immediate kin (as it appears Lenhart never married or had children)? What religion was Lenhart (hopefully Methodist, Lutheran or Presbyterian)? The answers to these problems would surely give me my answer.  Clock made by Godfrey Lenhart (c. 1777) Clock made by Godfrey Lenhart (c. 1777) “Show Your Work” My wife (the math teacher) always stresses to her students that one of the most important aspects of solving a math problem is to “show your work,” letting others know how you reached a particular answer to a problem. I will follow suit and share my "work" with you as well. You’ve already witnessed my first steps in scouring the Staunton newspaper article for clues, while tracking down the original article in the Baltimore American. I next went to Ancestry.com to search for a potential Family Tree that would include William Lenhart the Mathematician. I found one immediately, and learned parental names: Godfrey Lenhart (1754-1819), who I successfully verified as a prominent silversmith and noted grandfather clockmaker in York, PA. William's mother was Mary Elizabeth Harbaugh (1753-1824). The Family Tree was a little shaky, so I sought out other genealogical histories of the Harbaugh family that could be found on the internet. One such gave me exactly what I was searching for, including the knowledge that Mary Elizabeth (Harbaugh) Lenhart was a daughter of early Swiss immigrant Yost Harbaugh. Her brothers, George, Ludwig and Jacob, left York in 1760 and brought their families to northwestern Frederick County. Settling in the vicinity of today’s Sabillasville, their last name soon became synonymous with the locale still known as Harbaughs Valley. And just in case you were wondering, Baltimore Ravens head football coach John Harbaugh is a descendant of this same family. William Lenhart had a sister named after his mother. Mary Elizabeth Lenhart, who somehow met a gentleman named John Bayly. I found that Bayly operate a store in the first block of West Patrick Street which sold linens, broadcloths, groceries and seasonable goods. I'm assuming that the family lived above or behind the store, as was commonplace in the early 1840s. The Bayley’s had a daughter named Catharine, who would marry a noted former Fredericktonian, Samuel Tyler (1809-1879). Mr. Tyler was a lawyer, author and Georgetown College professor. I was already familiar with some of Tyler’s other writings, including a memoir of Roger Brooke Taney. I now surmise that Samuel Tyler was S.C., the original newspaper memorial's writer, as Mr. Lenhart was his wife’s uncle. (I can’t explain S.C. instead of S.T. but perhaps we can chalk it up to a typo).

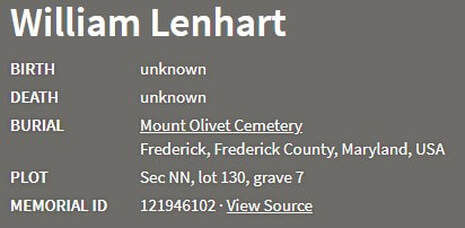

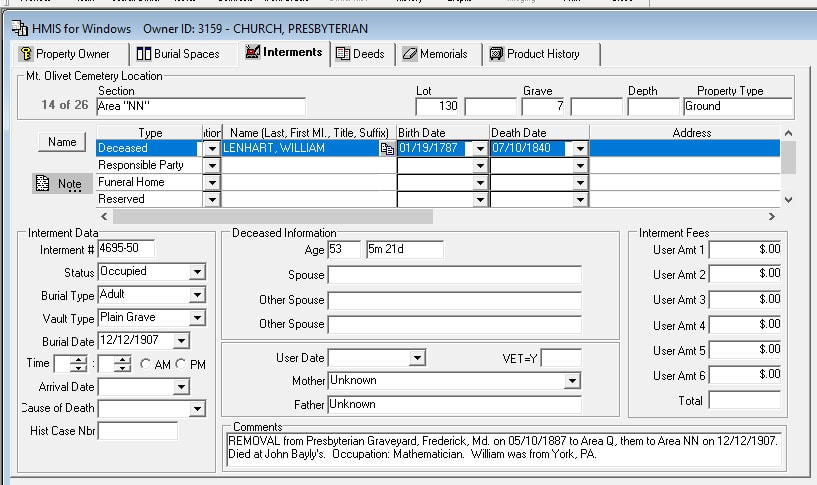

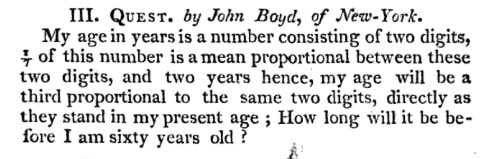

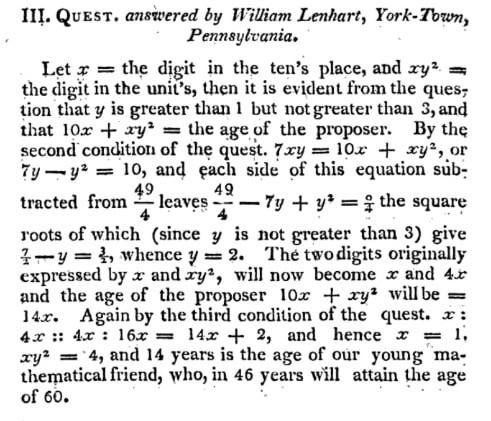

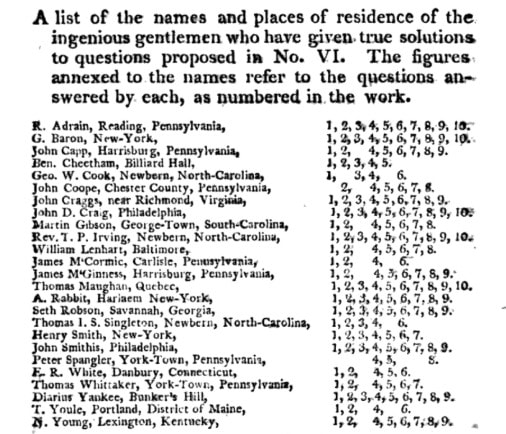

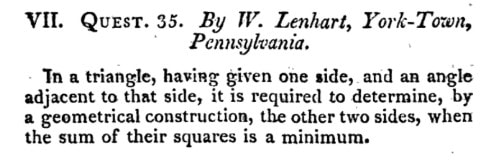

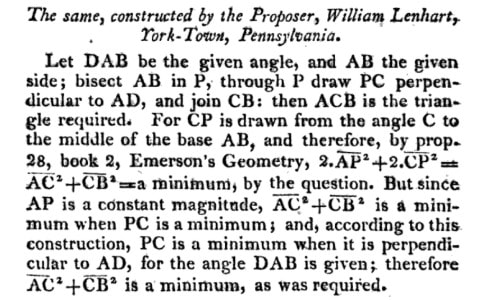

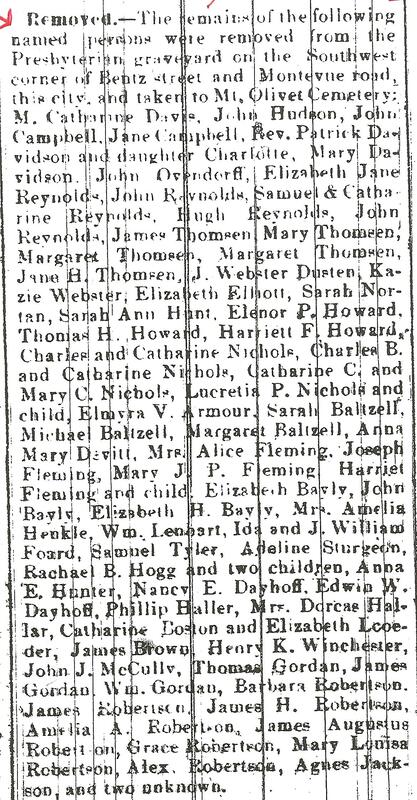

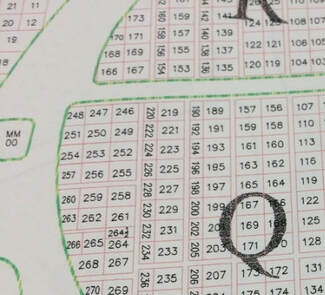

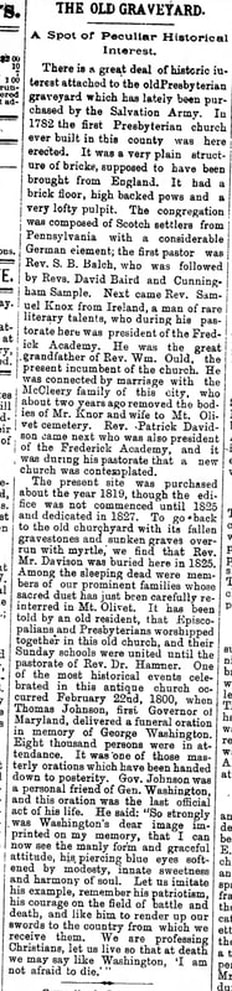

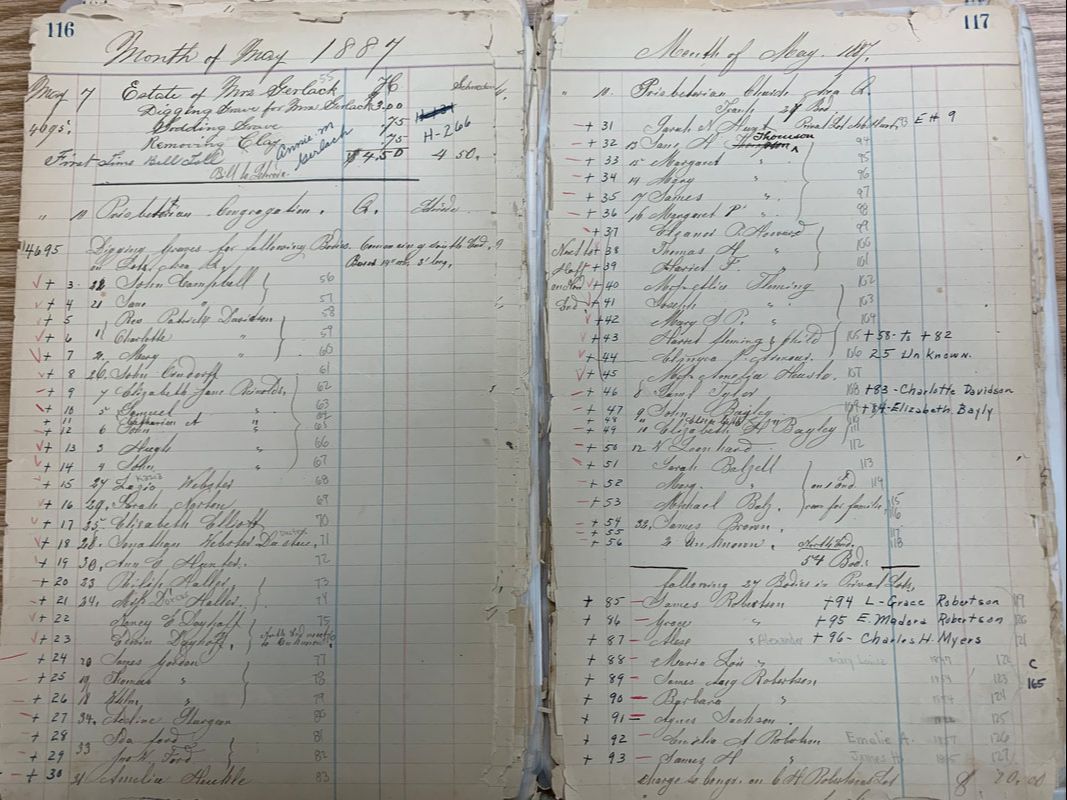

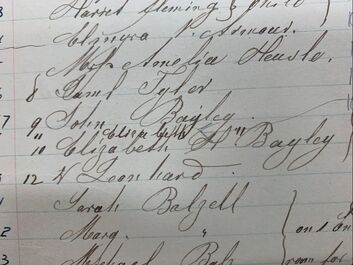

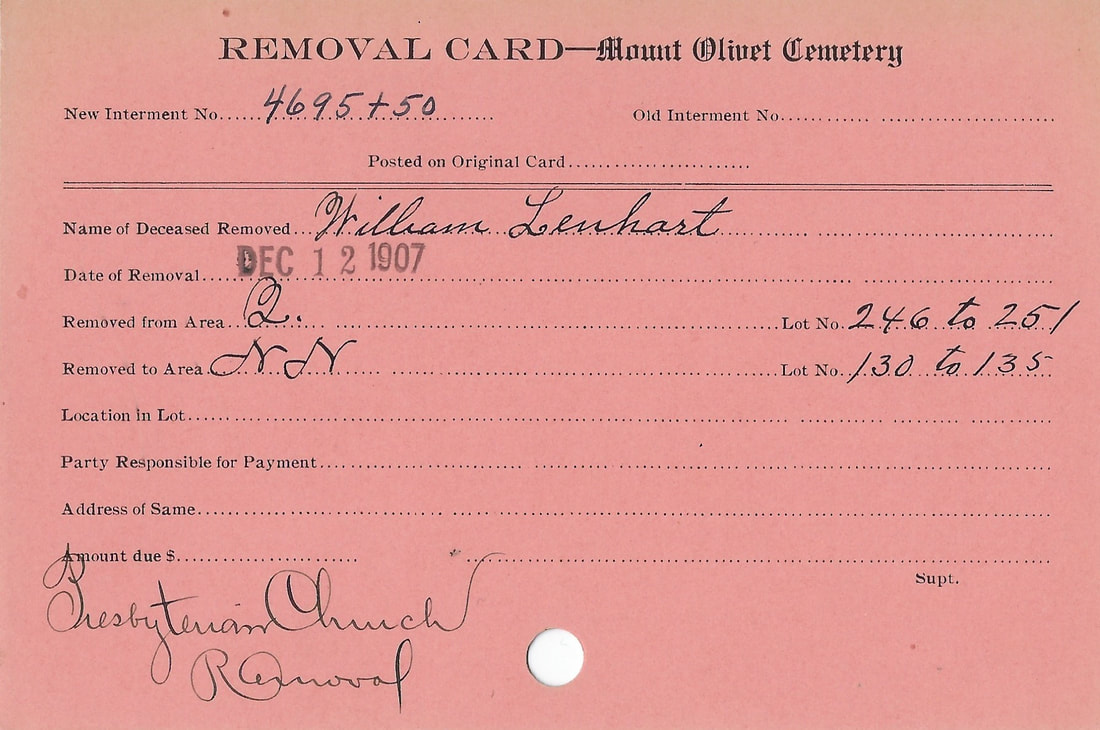

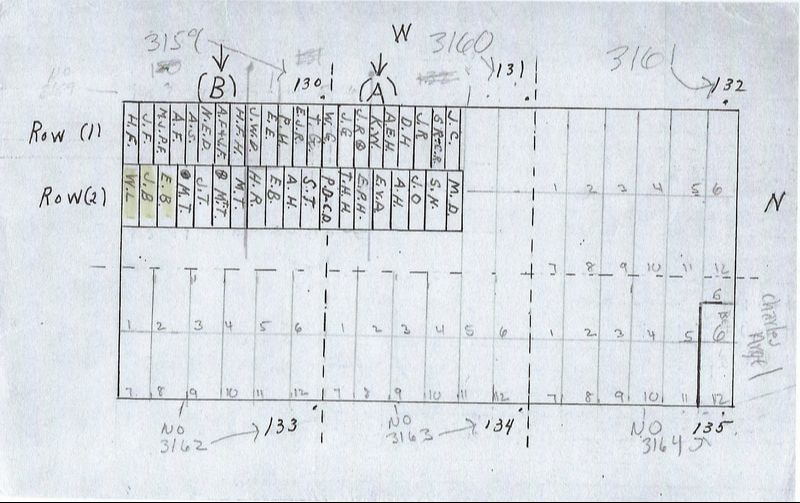

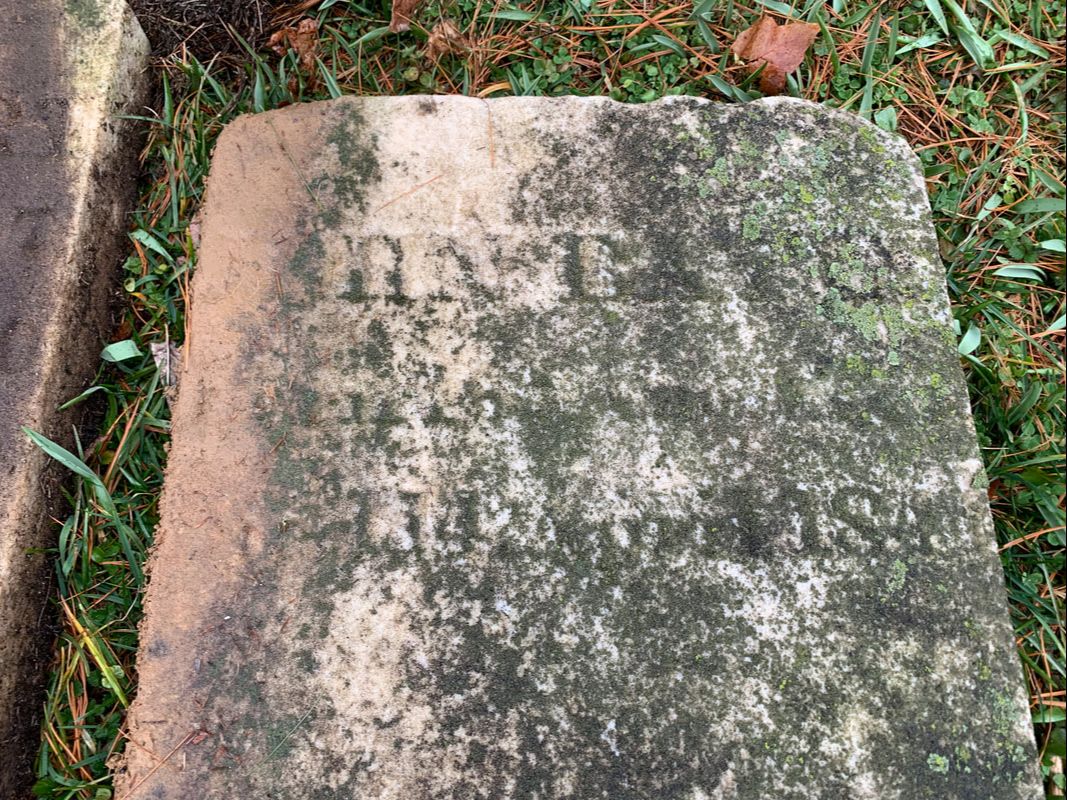

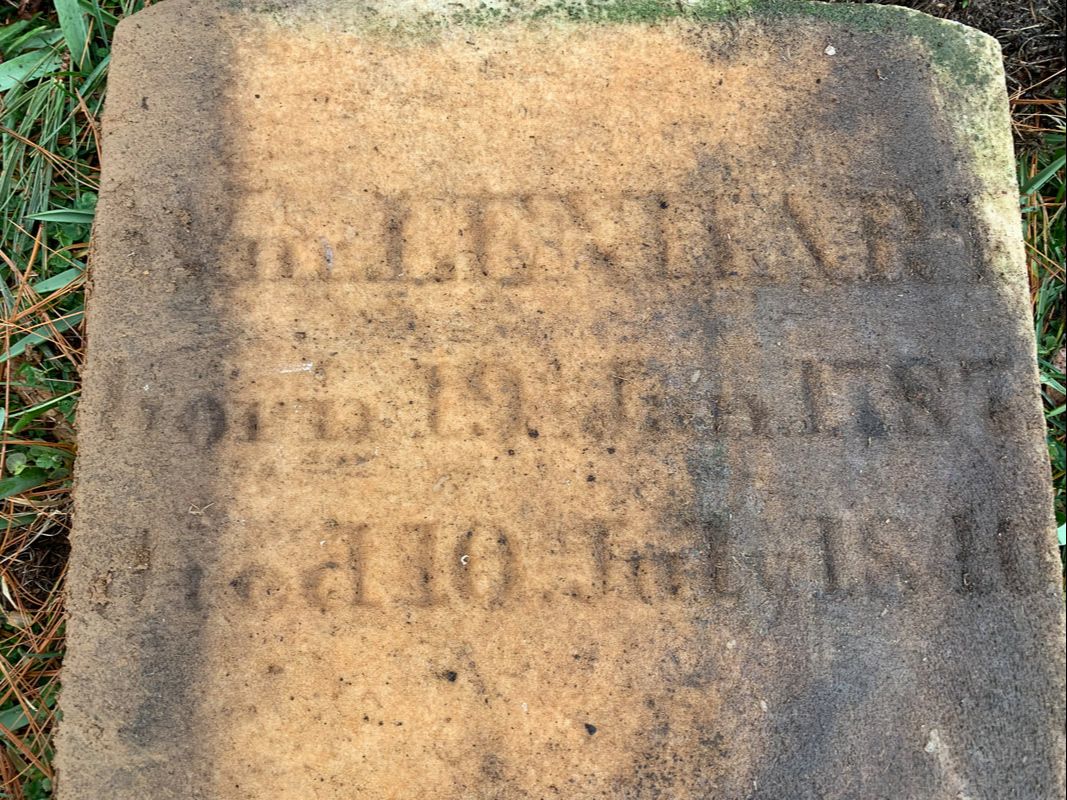

I quickly returned to Find-a-Grave and found both John and Mary Bayly buried in Mount Olivet. No pictures of stones either, but elation struck me when I found that they, too, were residing in Area NN, Lot 130, graves 7A and 8. I had successfully proven the relationship between Lenhart brother and sister (now a Bayly), and more so, decedent and famed mathematician! Of course, when I came into work on Monday, our database included information pertaining to Area NN's William Lenhart ranging from vital dates, to stating the fact that he was a removal from Frederick’s Presbyterian Cemetery on May 10th, 1887. Our data also had him as hailing from York, PA, dying at the residence of John Bayly, and, finally listed as an occupation that of a mathematician. Oh well, “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger” as they say—an interesting expression to recite as a full-time employee of a cemetery, for sure! Several old math journals from the 19th century mention Lenhart’s heroics answering prize questions offered up in monthly publications like the Mathematical Correspondent under the leadership of editor George Baron. The Correspondent presented problems to subscribers inviting them to solve and send in answers, which if correct, would be published in upcoming volumes. Lenhart was a regular contributor of both questions/problems, and answers. The following clippings come from the pages of various editions of The Mathematical Correspondent (1804).  I really didn't find much more on William Lenhart in old newspapers. Town diarist Jacob Engelbrecht recorded the mathematician's death, but not anything more. Lenhart’s name came up in several online searches connected with scholarly articles on math and its history in America. A particular interest to me was exploring how modern academics viewed William Lenhart today? I found an impression of his legacy in an article on early American mathematics journals, in which D.E. Zitarelli writes: When it comes to the study of mathematics in this country, we describe six of its major contributors, two of whom are known somewhat (Robert Adrain and Robert M. Patterson), but the other four seem to have slipped into obscurity in spite of accomplishments that deserve more recognition (William Lenhart, Enoch Lewis, John Gummere, and John Eberle). In 2005, Lenhart was ranked as the 7th top problemist of the early 1800s by Zitarelli , a bonafide expert on the subject having published his 2019 book entitled: A History of Mathematics in the United States and Canada: Volume 1: 1492–1900. An online journal article from the periodical Historia Mathematica (aka The International Journal of History of Mathematics) found at (https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/82122927.pdf) and entitled: The Fading Amateur: William Lenhart and 19th-Century American Mathematics by Edward R. Hogan of East Stroudsburg University (East Stroudsburg, PA). This work was published in 1990 by the Academic Press. Dr. Hogan writes: "There were amateur mathematicians in the United States after William Lenhart (1787-1840); there still are today. But Lenhart, although strictly an amateur in the sense that he neither received nor sought to receive revenue from his mathematical work, was one of the leading American mathematicians of his generation. He is the last person, to my knowledge, who was both. Lenhart was highly regarded by his countrymen. By the time of his death, he was heralded as a mathematician of extraordinary ability. Samuel Tyler, although not a scientist, was one of the foremost Baconians in America and Lenhart’s nephew by marriage. He said of his uncle’s contributions to the Mathematical Miscellany: “They have gained for him a reputation as the greatest Diophantine Algebraist that ever lived; and this is no mean renown, when it is considered that a Euler, a Lagrange, and a Gauss are his competitors." Such words might be dismissed as exaggerated praise from family and friends, but others with far more mathematical knowledge gave Lenhart similar compliments. Probably the most impressive came from Charles Gill, a competent, if self-taught, mathematician. He wrote to Lenhart: “No one will now deny that you have done more with the Diophantine analysis than any man who ever lived." In addition, the mathematical astronomer Daniel Kirkwood described Lenhart as an “eminent mathematician” and cited Gill’s evaluation, implying his agreement." Dr. Hogan also shed a bit more light on how William Lenhart suffered his life altering afflictions. After being offered a partnership in a business firm in 1812, Lenhart went home on a holiday to see his family, friends, and fiancee, and met with a freak accident. He was taking a ride in a gig when he passed by a traveling menagerie. The roar of a lion in the caravan frightened his horse, and Lenhart, thrown from his gig, fractured a leg and seriously injured his back. He never recovered; for the rest of his life he suffered extreme pain, exacerbated by a second fracture of the same leg.  Daniel Kirkwood (1814-1895) Daniel Kirkwood (1814-1895) The article goes on, but I think you are now likely feeling overwhelmed. I certainly am at this point in writing, and am starting to have uncomfortable flashbacks to certain math classes in my high school and college career. A final article of note was found in math periodical entitled The Analyst (Volume II, No. 6). A piece in this November, 1875 edition was penned by a colleague and friend of Lenhart’s, the fore-mentioned astronomer Daniel Kirkwood. The professor recounted that Lenhart was extremely fond of smoking cigars, owned a small library of books with some volumes dating to the early 1700s, and oftentimes replied to math publications with solution submissions to math questions under pseudonyms because he had found various ways to solve problems. He used the name Diophantus on a number of occasions, and more surprisingly answered as a supposed female contributor as well—using the name Mary Bond of Frederick Town, MD.  Frederick's Presbyterian Church on W. 2nd Street (c. 1900) Frederick's Presbyterian Church on W. 2nd Street (c. 1900) The Gravesite My last task was to seek out Lenhart’s exact gravesite. Since there was no picture on the Find-a-Grave website, I pondered if our local math genius was simply buried in an unmarked grave? This was often common as the re-interment process was quite complicated. Many graves were unmarked in former cemeteries, and old stones from the early 19th and 18th centuries didn’t hold up well in some instances. Those deemed shabby, were oftentimes banned from public display in the once- uppity places like our sparkling new “garden cemetery” during its earlier days. Some ragged stones hit the trash heap, others were buried. This would happen regularly when certain families "ponied" up the funds to have new stones made, and sometimes elaborate family memorials crafted, as replacements. Our records are pretty good here at Mount Olivet, and extensive work has been done over the years to document interments in places like Area NN in an effort to compensate reburials lacking gravestones or any other kind of marking. An interesting wrinkle in this particular re-interment case relates to the Presbyterian Cemetery removal of 1887. The church graveyard in question was originally located at the southwest corner of Dill and N. Bentz streets. Various clergy members and other VIP's would be buried behind the church itself, located on W. Second Street. The majority of burials of this congregation were placed in the other graveyard. Back in the day, Dill Avenue was originally known as New Cut Road. Upkeep for these cemeteries was difficult and costly for churches, especially when the burial business was now going to Mount Olivet—a well-established professional cemetery in town.  The old Presbyterian graveyard is located on this 1873 Titus Atlas map near the upper left of this image at the intersection of N. Bentz Stand Dill Ave (as it becomes W. 4th Street to the east). The larger burying ground below the E. H. Rockwell residence is the former German Reformed Cemetery, today known as Memorial Park Many congregations simply bought land in the form of lots within Mount Olivet, in an effort to transfer their own graveyard inhabitants. Since 1854, individuals had been removed here and there across town from various churchyards and associated graveyards and brought to the new cemetery by families with the means to do so. Mount Olivet was "the place to be,” even in death. Younger generations purchased extra lots in an effort to remove bodies from elsewhere in an effort to reunite themselves one day with parents, grandparents and other members of extended family in one location. The Presbyterian Church bought lots 246-251 in Area Q in 1887, just across from the Barbara Fritchie monument. Bodies were brought from the former burial ground—among them William Lenhart, his sister and brother-in-law (the Baylys) and buried on May 10th. I would find their names among those appearing in a newspaper article from the May 18th, 1887 edition of the Frederick Examiner which reported the mass removal from Frederick’s Presbyterian graveyard. You may recall, that earlier in the story, I gave Area NN as the location of William Lenhart’s grave, not Area Q? In December of 1907, a decision was made to rebury the Presbyterian bodies in Q (hailing from the old graveyard on N. Bentz) in Area NN. The move was only about 30 yards away. So William Lenhart was buried three times, a charming way to be handled in death. Armed with cemetery diagrams, I went to Area NN to find Lenhart’s grave and subsequent gravestone. All the while, I said to myself, “If this guy doesn’t have a stone, can I actually call this a “Story in Stone?” This was a logical question that I’m sure would make Lenhart and a host of ancient Greek math philosophers smile for sure. Once on the scene, I sadly went to the spot where Lenhart and the Baylys were supposed to be located. I found nothing but unmarked grave here. I double and triple checked the area and maps, but still with no success. Upon closer examination, I noted two downed-headstones, innocently leaning behind the row in front that Lenhart and the Baylys were supposed to be within. I strained to read a faded name on the top of these two stones, after brushing off debris. I then found the name "John Bayly.” I was once again very excited, well, you know, not as happy as at the birth of my son, but pretty happy. I carefully pulled that stone off the other to expose the second gravestone leaning underneath Bayly’s. Bingo!!!--it was that of William Lenhart, and I won’t confirm, or deny, that I may have done some sort of crazy math celebratory dance, then and there, in Area NN. I next carefully laid both stones out in the places they were supposed to occupy. I questioned the whereabouts of Mrs. Bayly’s gravestone, as it was visible, yet noted on the old diagram I held. I then thought perhaps she didn’t have one, or shared her husband's. The next morning, I made a visit to the gravesite to see the stone faces of the Lenhart and Bayly monuments. I had hoped overnight rain showers had helped clean off additional mud and debris. I soon flagged down our assistant grounds foreman, Rob Reeder, who was passing by the Area. I told him a bit of the story and how I found these stones stacked behind other graves. I also asked if he would kindly re-set the Lenhart and Bayly stones in place sometime in the coming months? He said sure, and even told me that he could do this later that same day. I certainly was expecting an answer of March or April. Excavation work began later that morning, and the original bases of each stone were found, having been placed within a cement trough. This method was responsible for serving as a foundation for the entire row of vintage stones from the former Presbyterian cemetery. I was called to the scene a short while later as a third stone foundation was found in the spot where Mary Elizabeth Bayly appears on lot maps. This was the base of a missing stone. Another search ensued and her gravestone (somewhat illegible) was found in two pieces, hidden behind the back row of Presbyterian congregation monuments and against the perimeter fence. The bottom piece of Elizabeth Bayly's stone fit against the foundation base like a "Cinderella shoe." Unfortunately though, erosion had rounded the major break area showing that this marker had been broken for a very long time, perhaps 50-60 years and never repaired. The other stones (Lenhart and Mr. Bayly) must have fallen more recently, but sometime before 2013, at which time the Find-a-Grave contributor posted the additions of William Lenhart and the Baylys to the Find-a-Grave website without photographs. I’m proud to say that in less than one week, we discovered a famous mathematician buried in Mount Olivet, found out more about his life and times, and set into motion the repair and resetting of his tombstone. This is the essence of our Mount Olivet Preservation and Enhancement Fund with a 3-part mission to preserve the history, structures and gravestones of our amazing cemetery. Our newly-formed Friends of Mount Olivet membership group will further this mission as volunteers will assist in documenting and assisting in the "resurrection" of fallen and damaged stones, while helping to raise needed project funds and support to benefit our historic monuments and memorials through repair.

It has been said that each of us dies two deaths. The first is when the physical body ceases to exist. The second is when you are forgotten, and disappear from the written and spoken record. I’d say that we successfully brought William Lenhart back to life—a great "addition" to our varied cemetery population. Just like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get.

3 Comments

Nancy Droneburg

2/16/2020 12:29:42 pm

It is always a surprise to read your stories. Please don't stop because history is passing us by.

Reply

Mary-Margaret Staley Myers

2/20/2020 03:40:29 pm

I am wondering if you grew up on Opossumtown Pike. Do you have a brother Donald and a sister, I believe her name is Shirley. I lived about a half mile closer to Frederick, if you are part of that family. Opossumtown Pike was a great place to grow up in those days. Just interested.

Reply

Maria Lenhart

4/23/2021 03:25:06 pm

This is an interesting history of a distant ancestor of mine. I wish I had inherited even a little of his mathematical abilities. We are both descended from Johann Peter Lenhart who immigrated from Germany in 1748 and settled in York, Pa. William's father Godfrey was an extremely talented clockmaker whose clocks are still highly prized today, including the one in the historic York courthouse where the second Continental Congress convened during the Revolution.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed