|

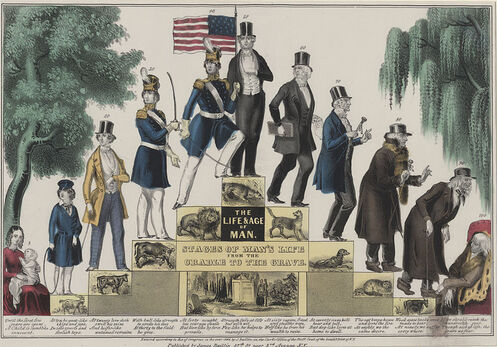

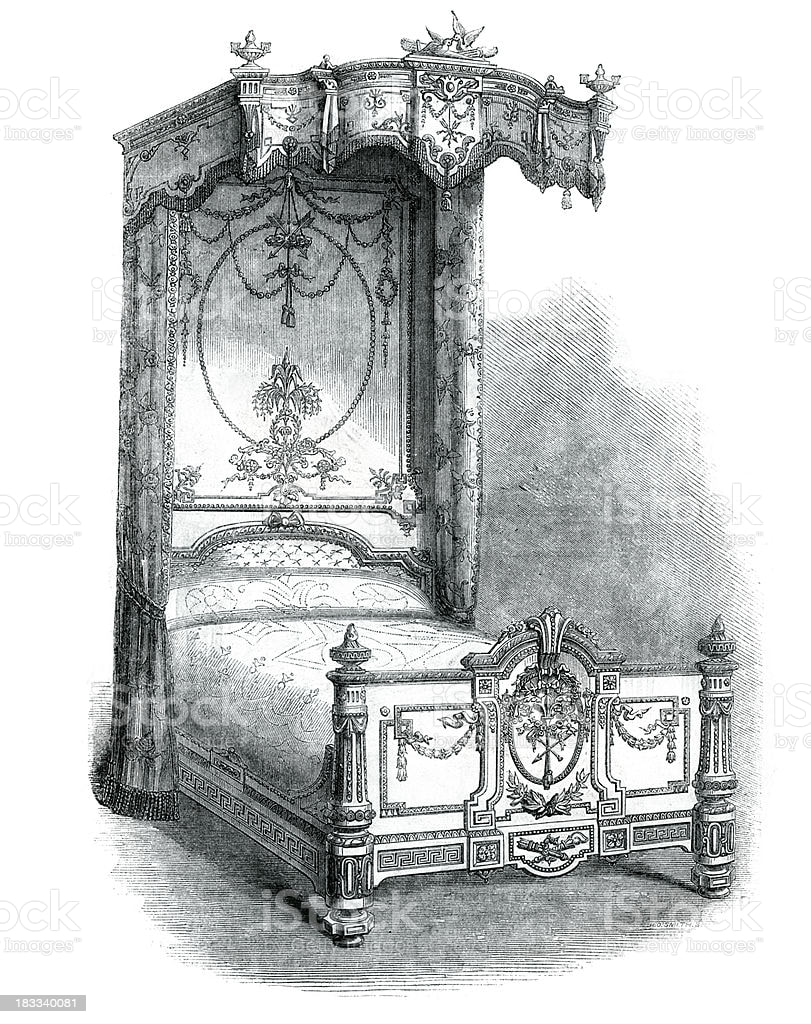

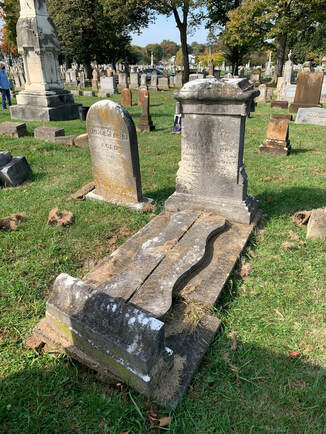

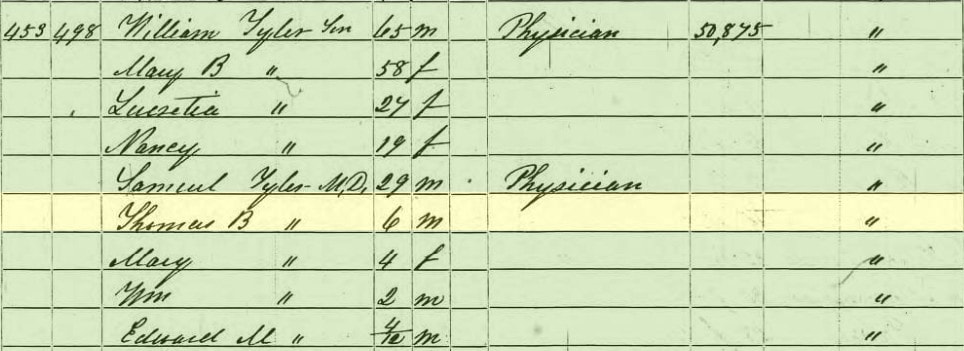

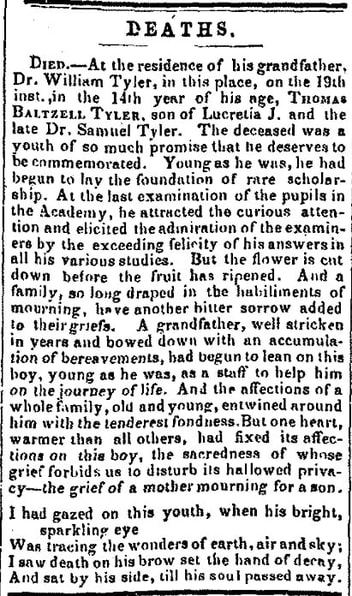

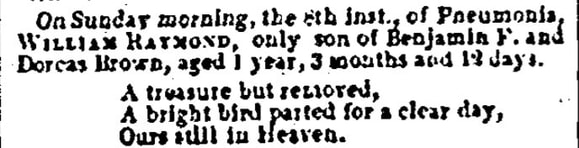

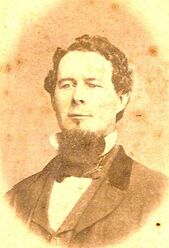

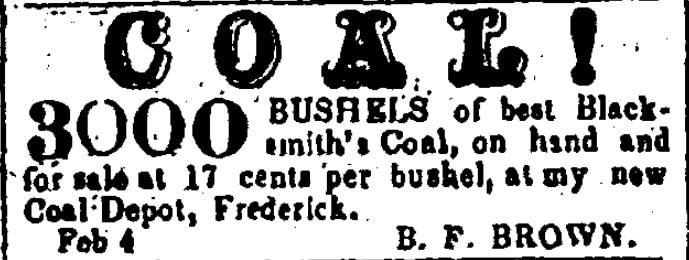

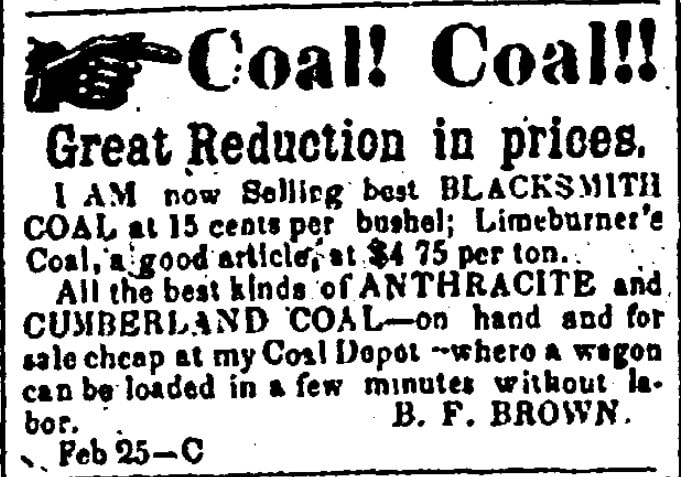

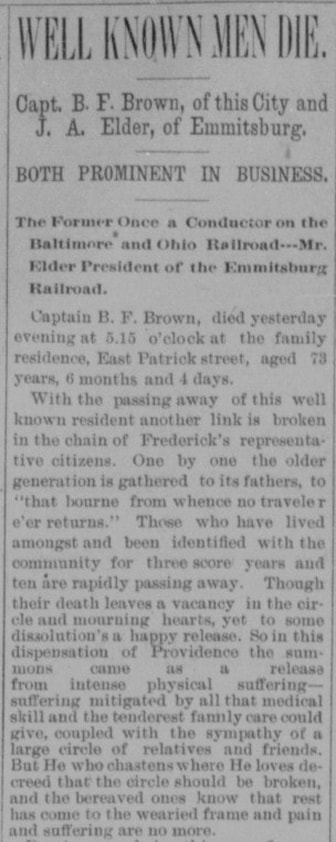

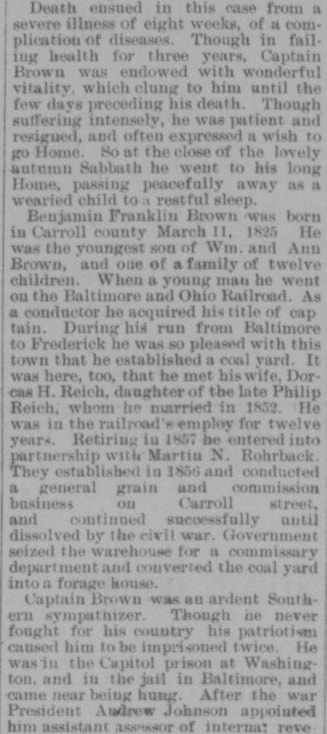

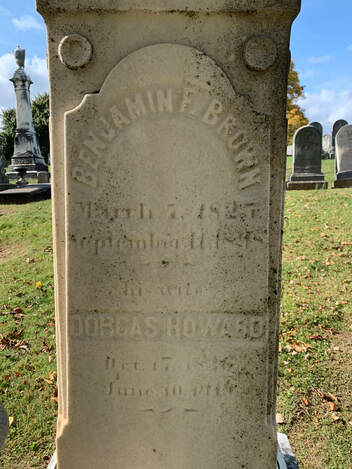

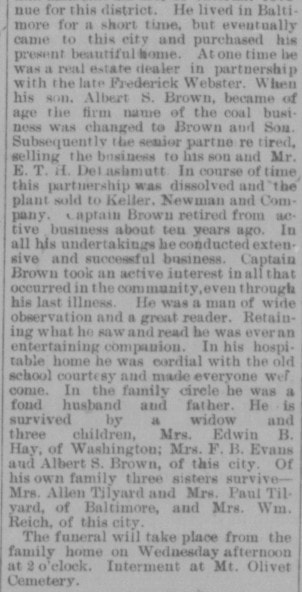

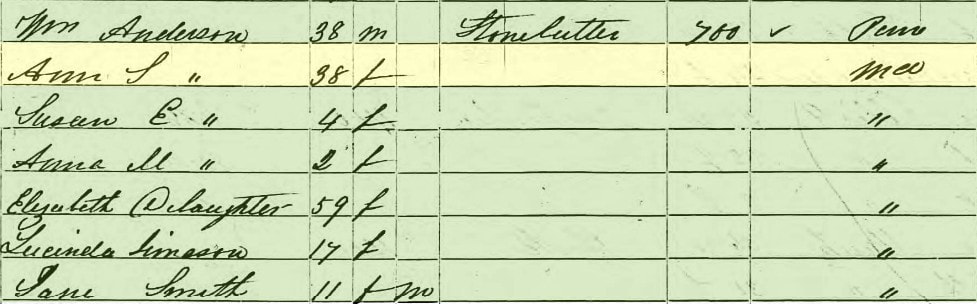

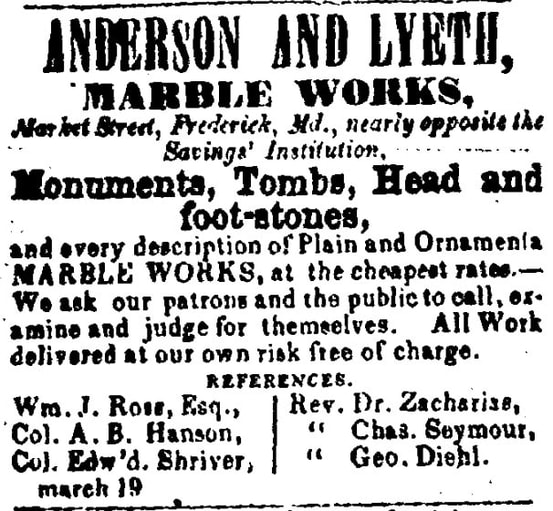

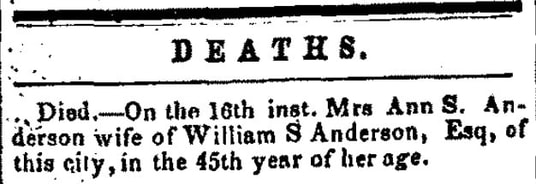

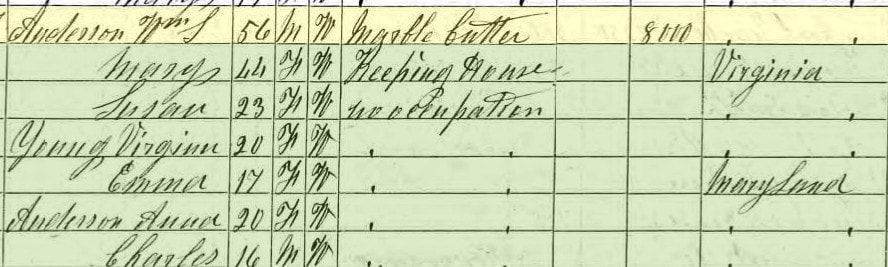

As I walk through the cemetery on a crisp, autumn day, I’m suddenly reminded of an idiom found often in British literature—“From the Cradle to the Grave.” It seems so fitting for a stroll through this hallowed place, as I look from gravestone to gravestone and contemplate the lives of the local tenants. Defined, the idiom beckons “From birth to death; the entire period of one’s life; throughout one’s life.” Simply put, this is what the hyphen stands represents on each and every monument, strategically sandwiched between birth and death dates of the decedent. The “Cradle to Grave” expression is usually used as an adjective, and has been around since the year 1709 when it appeared in author Richard Steele’s British literary and society journal entitled The Tatler. Steele used the idiom as follows: “In a word, to speak the characteristical difference between a modest man and a modest fellow; a modest man is in doubt in all his actions; a modest fellow never has a doubt from his cradle to his grave.” I thought this expression ("Cradle to Grave") would serve as a nice title for this week’s edition of “Stories in Stone” in which we could explore another unique style of cemetery markers referred to as “cradle graves.” These are also known as “bedstead monuments,” and were very popular in the 19th century, around the time of the American Civil War. A cradle or bedstead is composed of a headstone, footstone, and cradling. These elements represent the headboard, footboard, and bed rails on a bedframe. In 2016, preservation specialist Ashley Shales of Oakland Cemetery (Atlanta, Georgia) wrote that cradle grave monuments portrayed a particular style that appealed to Victorian-era sentiments for three reasons: “First, heaven was likened to “returning home,” which was comforting to loved ones left behind because they could hope for a future where they were eternally reunited. A bed is a natural symbol of home. Second, the 19th century witnessed a phenomenon referred to by historians as the “feminization of death.” Public displays of mourning became fashionable, as did more beautiful, peaceful, and pleasant monuments and iconography. The bed is not only a symbol of the home, but of femininity and domesticity. The third — and the most frequently cited — reason for the bedstead’s popularity is that it likens death to sleep, a notion that undoubtedly eased the sorrows of many mourners.” Bedsteads come in several forms and are made from a variety of materials, depending usually on the purchaser’s economic means, available stone, and current fashions. Headstones may be quite elaborate, often featuring iconography such as lambs or lilies, symbolizing purity and innocence. Most bedsteads are made of marble. Headboard and Footboard On some cradle graves, the top is designed to resemble the headboard of a bed and the bottom looks like the footboard. Plain or decorative curbing (or molding) can also be used to outline a single grave in the shape of a bed; hence these graves are also known as bed graves. A perfect example of this survives in the final resting place for Thomas Baltzell Tyler in Area B/Lot 113. Hailing from the prominent Tyler family of Frederick City, Thomas died at age 13 after an illness of three weeks. He was the son of Samuel Tyler (1820-1856) and Lucretia Josephine Baltzell Tyler (1823-1901) and was born on August 9th, 1843. The oldest of four children, he was a grandchild of the prominent Dr. William Tyler, a physician who served as the first president of the Farmers & Mechanics Bank, a post he would hold for 55 years from 1817 until his death in 1872. Young Thomas Tyler passed less than a week before Christmas in the year 1856. His obituary says the 19th, however his stone says December 20th. Child's Cradle Grave Although they can be found throughout the country, cradle graves were more popular in the South and Midwest regions. William Raymond Brown died of pneumonia at the age of one year and three months. He was born at the advent of the American Civil War on November 26th, 1861. The beautiful example of this grave style can be found near the drive on the east side of Area E, where Lot 126 holds several members of the deceased' immediate family. William’s father, Benjamin Franklin Brown, has the most auspicious monument of the group. He was an ardent Southern sympathizer during the war who was arrested on more than one occasion for his sentiments. Mr. Brown ran a successful warehouse business at the lower train depot on Carroll Street. He specialized in providing coal for his patrons, but bought and sold several other commodities. Although little is known about young William, his father’s life story is well-told through his obituary which appeared in the local papers in mid-1898. Adult Cradle Grave Despite the name, cradle graves were not just for children. Adult graves were also marked in this manner. One such is just up the hill from young William Raymond Brown within Area E. In lot 34, one lone soul exists in a space capable of holding several other family members. Ann Savilla (Delauter) Anderson is the only one here as I surmise her husband and two daughters left the Frederick area a few years after Mrs. Anderson’s untimely death at age 44. Ann was born on April 11th, 1813. Little is known about this parishioner of the Evangelical Church. Interestingly, however, she was married in Frederick’s German Reformed congregation on February 5th, 1845 to William S. Anderson of Pennsylvania. The couple would have two little girls, Susan Elizabeth and Anna Mary and a boy, Charles, born in 1855. It is thought that the family lived on E. Church Street near the intersection with Chapel Alley. Mr. Anderson was a stone cutter and monument maker who specialized in marble works. It appears he commenced his business in the late 1840s as is mentioned by Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht with an entry dated July 24th, 1851: “Mr. William S. Anderson, Stone Cutter of our town has eleven tomb-stones to make for the Catholic Priests of our town. They are all buried in the graveyard just at the north end of the old church.” Sadly, William S. Anderson’s wife Ann, would die on March 16th, 1858 and he was saddled with the responsibility of carving her gravestone. For one reason or another, he felt compelled to mark her gravesite with a bedstead design. He would include an inset relief carving of a woman with an anchor, symbolizing hope. At this time, his business was located in the first block of N. Market Street.

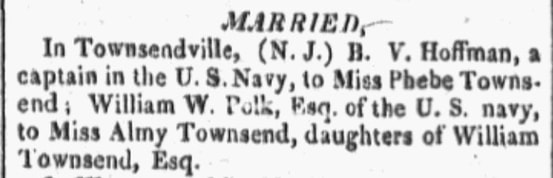

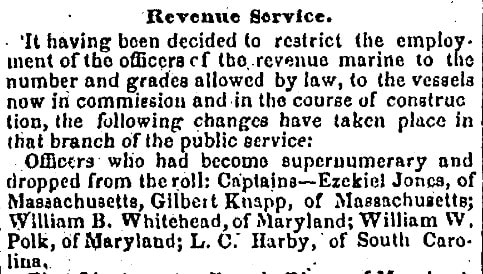

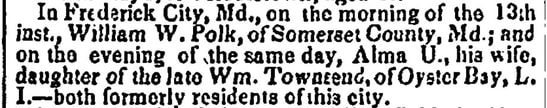

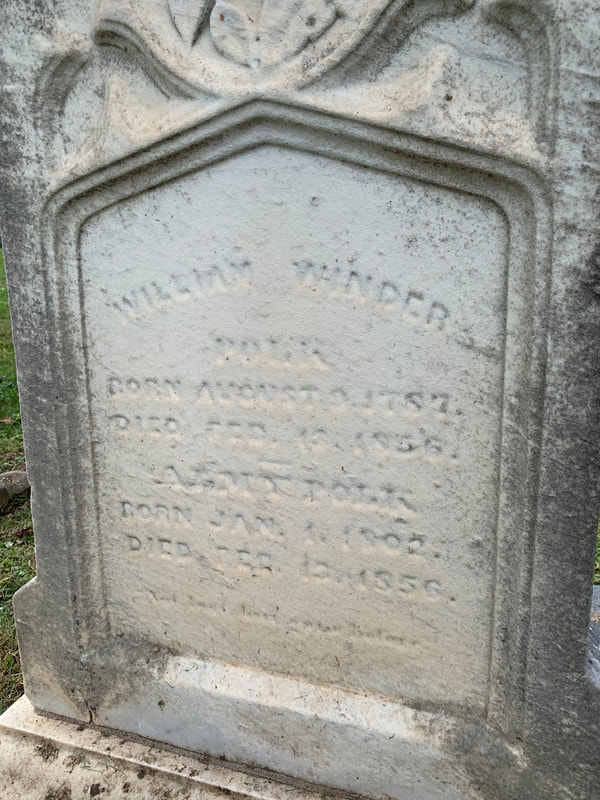

Leaves and Grass on Cradle Grave The empty space between the curbed sides was usually filled with “blanket plantings” – flowers, grasses, or bushes that filled up the inside of the cradle grave, giving it the full and lush appearance of a bedspread, from spring through fall. In the winter, snow would take on the appearance of a blanket drifting over the grave. A short distance from the Key Memorial chapel towards the front of the cemetery, lies a bedstead dedicated to the memory of a well-traveled couple, neither hailing from Frederick originally—William Winder Polk and wife Almy. Mr. Polk was a native of Coventry parish, Somerset County on the eastern shore. He was the son of Wesley William Polk (1752-1814) and first wife, the widow Esther Polk Handy. The youngest of eight children, he was born on August 3rd, 1787. Mrs. Polk was the former Almy U. Townsend of Oyster Bay, Long Island and born on January 1st, 1802. She was married in a double ceremony involving her sister Phoebe on November 27th, 1817. Both girls married Navy officers. Shortly after marriage, the couple could be found in New Haven, Connecticut. Mr. Polk was a member of the US Marines. William and Almy had seven children, but raised five into adulthood. New Haven marked the birthplace of daughter of Mary Townsend Polk, born September 8th, 1822. She married a Victor Monroe of Kentucky, a cousin of former president, James Monroe. Their son, Francis Adair Monroe (1844-1927) became a judge in the court system of Louisiana. Mary would live a majority of her later life in Milledgeville, Georgia where she passed. Capt. William Winder Polk’s career in the US Navy and Marine Service, as it was called back then, does not seem to fit the fact and story-line of most sailors. It seems to be a career he began while in high school. Details are slim, but it appears he worked in various positions including Hawaii, the northern central states, and New England and the long Island Sound. Eventually, Capt. Polk would be one of four Maryland officers who actually received petty cash, while working for the revenue service. An article found in a vintage newspaper announced that he was dismissed from duty in February, 1856. I haven't been able to figure out why this couple came to Frederick, most likely after living for years in Annapolis. I am also searching for a fuller obituary in the local Frederick newspaper archives, but don't have access to microfilm of the specific year which I need. Interestingly, both husband and wife are said to have died on the same day. William died on the morning of February 13th, 1856. Wife Almy was said to have died that very evening of the 13th. The Polks would be buried on February 14th (Valentine's Day), 1856 in a lot located on Mount Olivet's Area H/Lot 26. To this day, they remain the only tenants in this lot which contains several more grave spaces. Although we can replace the expression "Cradle to the Grave" with synonyms such as lifetime and existence, the bed analogy brought about by Victorian era is surely something to behold, especially as can be evidenced by these unique grave monuments.

2 Comments

12/5/2023 11:55:53 am

I wanted to express my gratitude for your insightful and engaging article. Your writing is clear and easy to follow, and I appreciated the way you presented your ideas in a thoughtful and organized manner. Your analysis was both thought-provoking and well-researched, and I enjoyed the real-life examples you used to illustrate your points. Your article has provided me with a fresh perspective on the subject matter and has inspired me to think more deeply about this topic.

Reply

12/5/2023 12:11:07 pm

I wanted to express my gratitude for your insightful and engaging article. Your writing is clear and easy to follow, and I appreciated the way you presented your ideas in a thoughtful and organized manner. Your analysis was both thought-provoking and well-researched, and I enjoyed the real-life examples you used to illustrate your points. Your article has provided me with a fresh perspective on the subject matter and has inspired me to think more deeply about this topic.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed