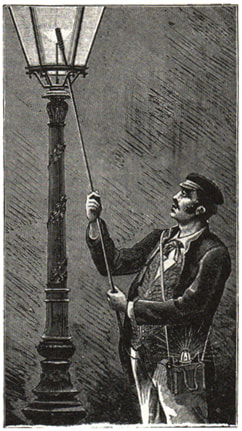

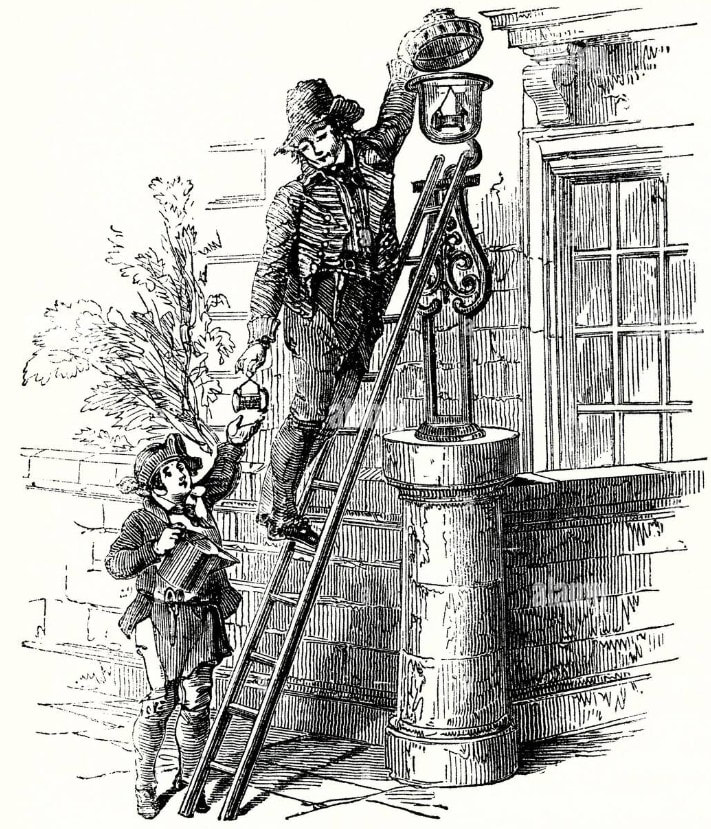

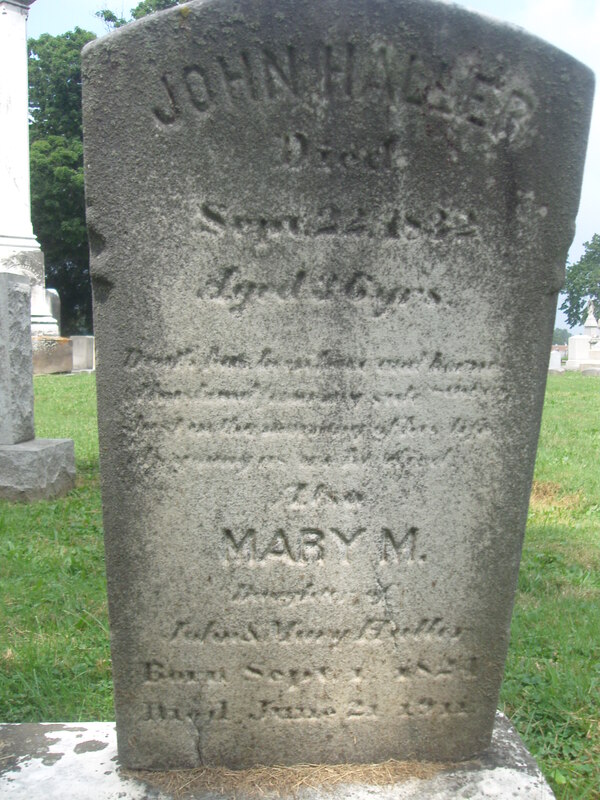

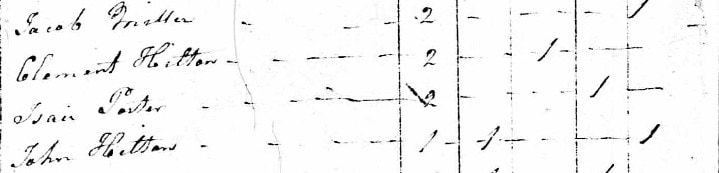

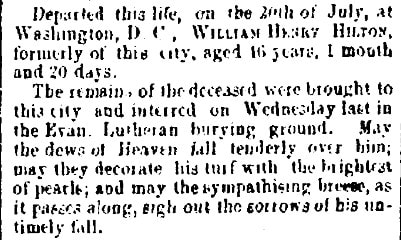

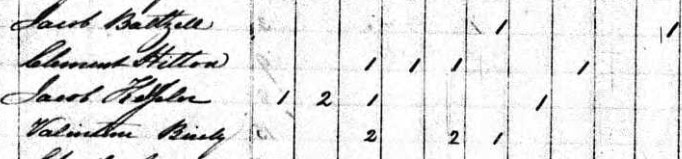

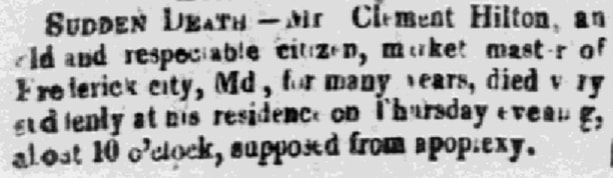

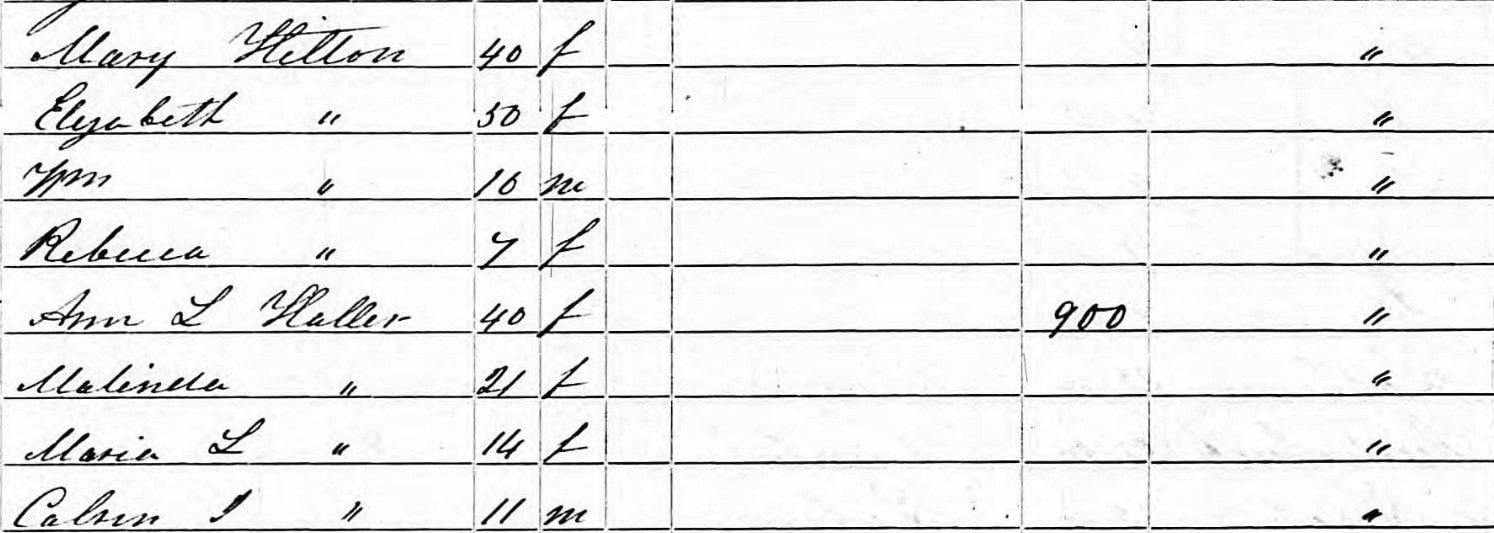

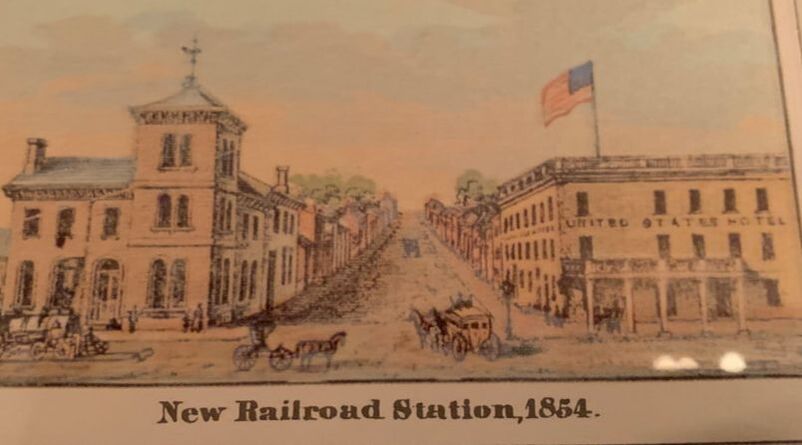

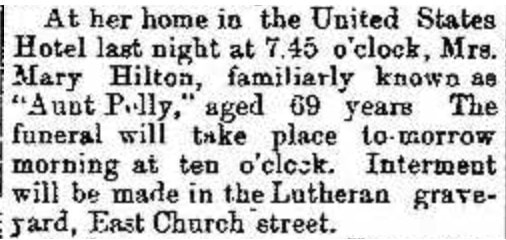

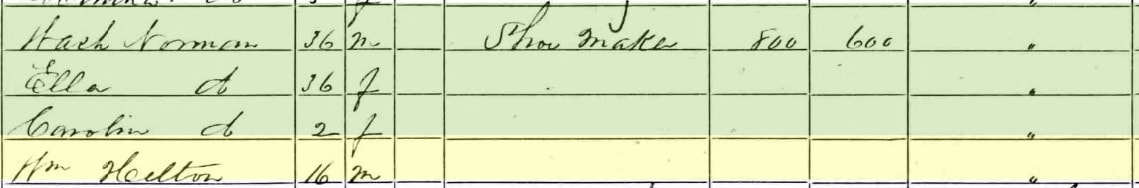

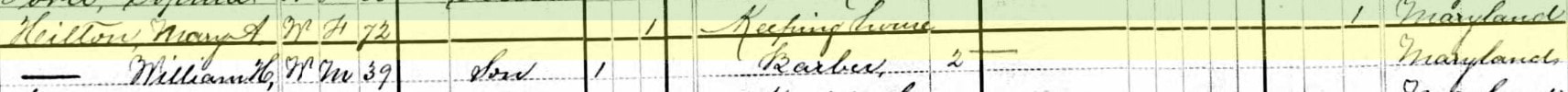

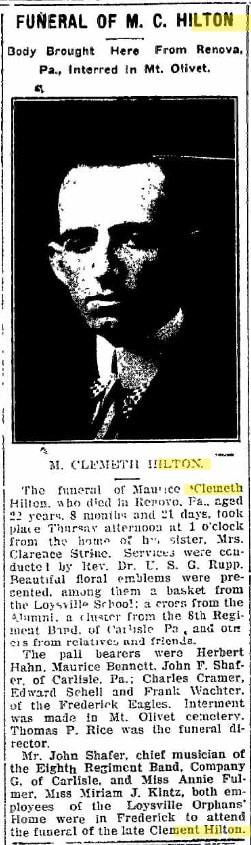

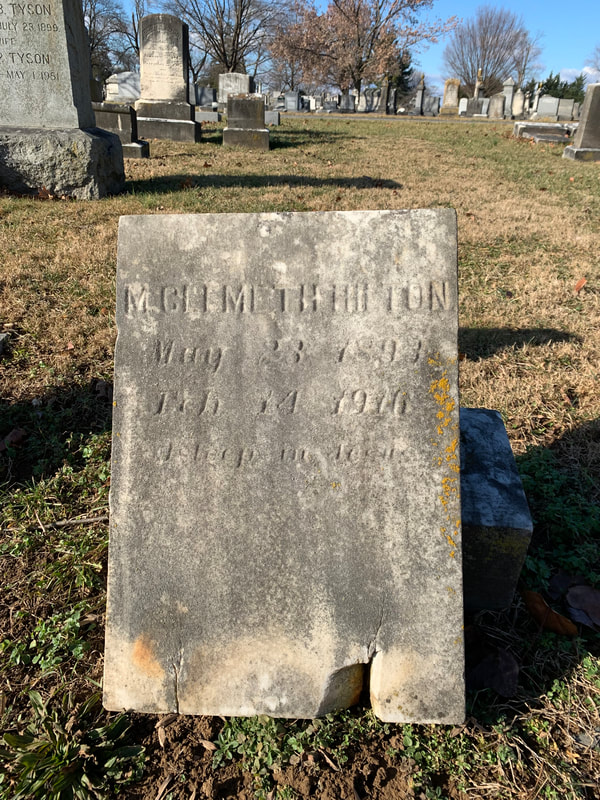

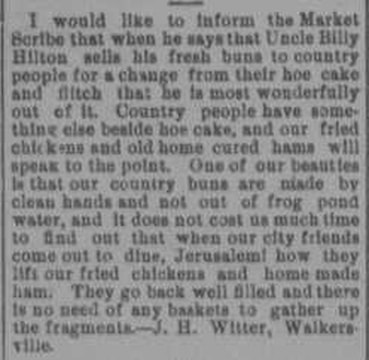

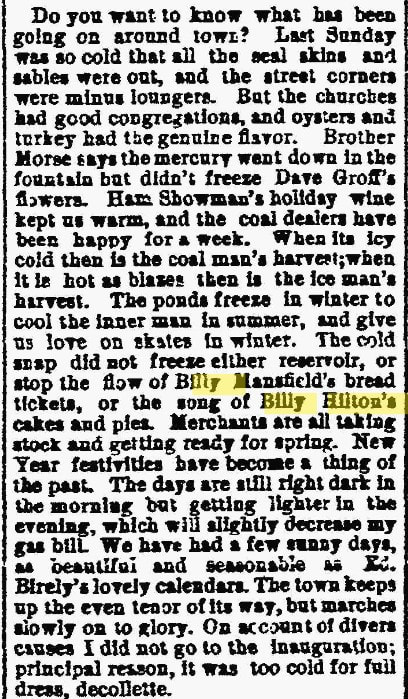

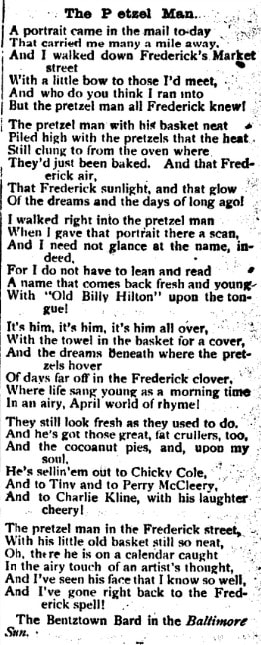

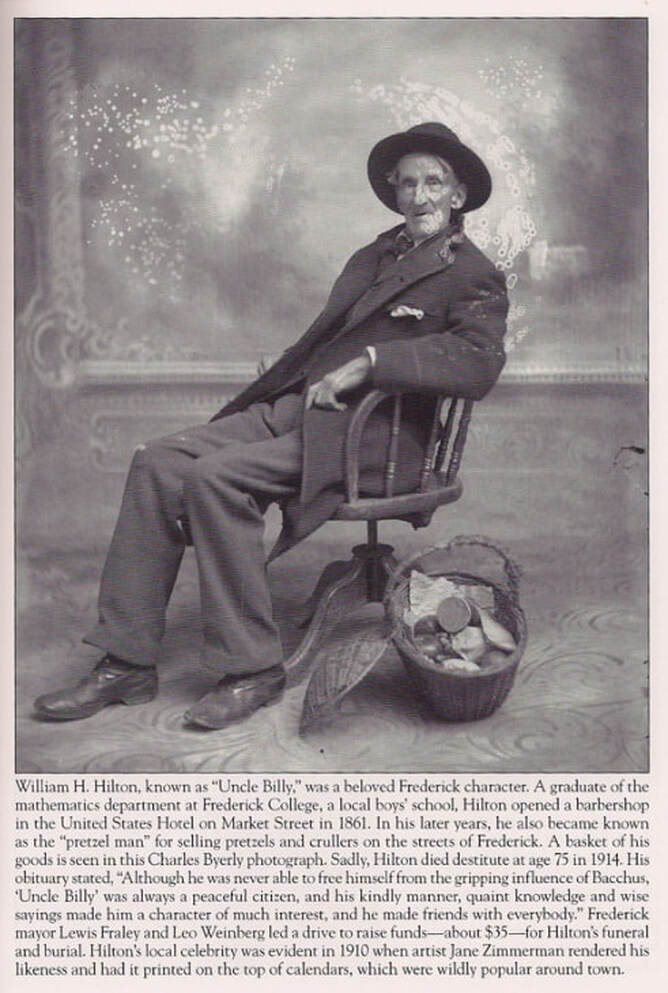

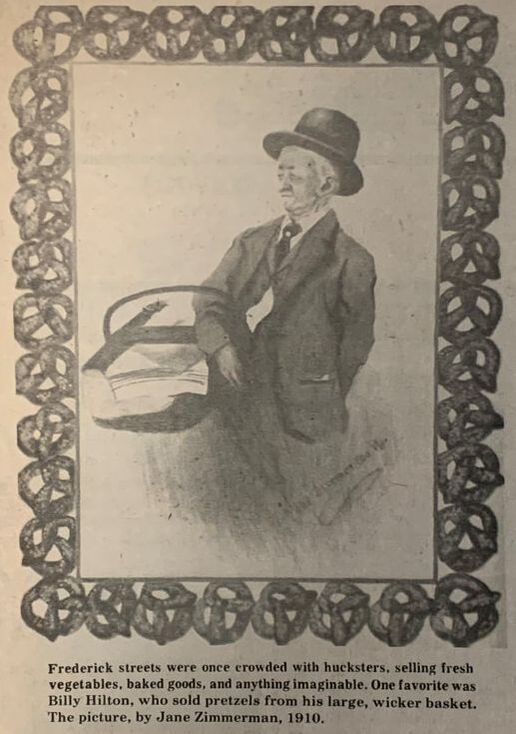

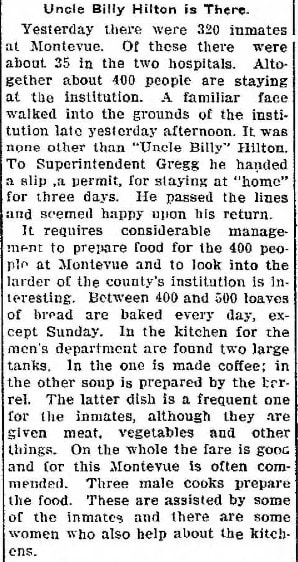

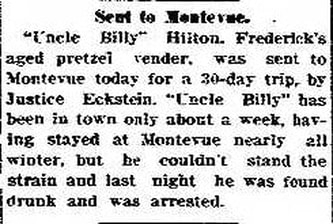

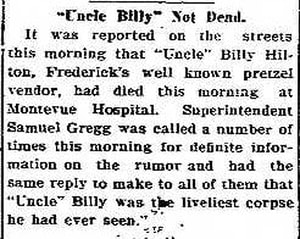

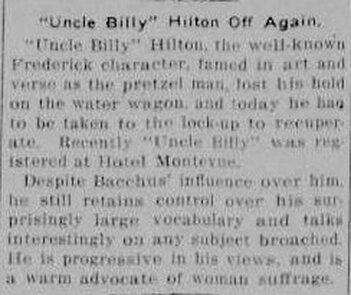

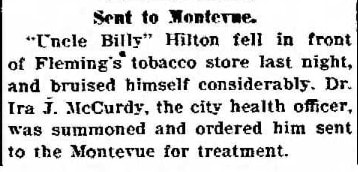

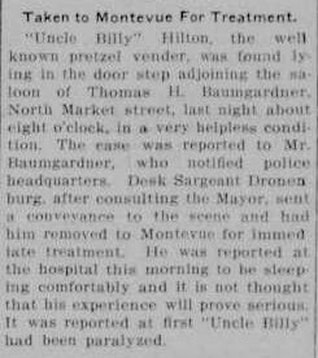

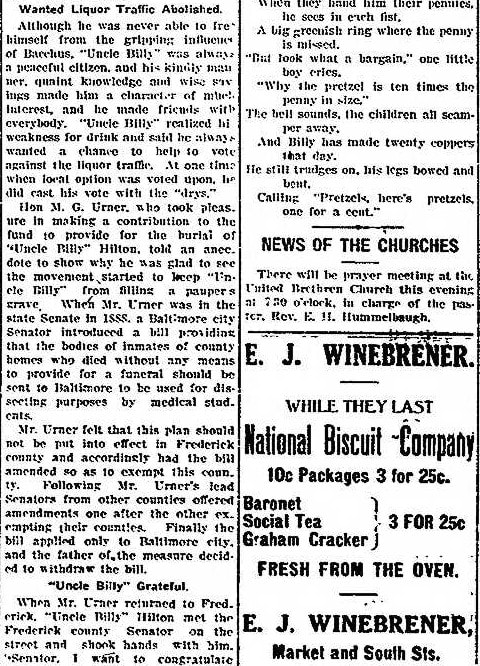

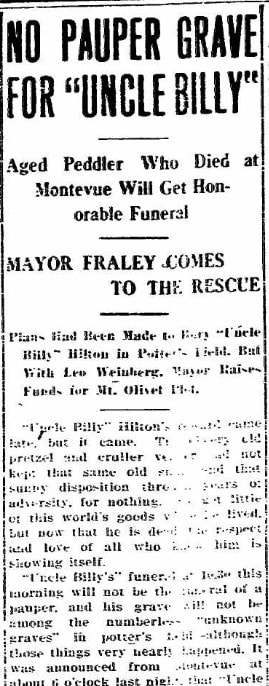

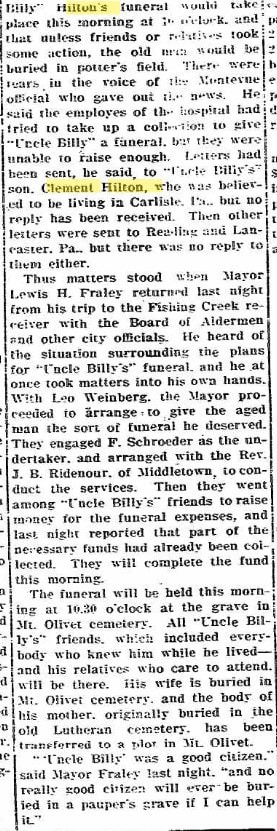

I’m going to try to tell you this “Story in Stone” at “the speed of light.” And speaking of light and dark, it’s hard to imagine Downtown Frederick without radiating brilliance unless, of course, you visit Mount Olivet Cemetery after sundown. With my old friend Ron Angleberger (owner/operator of Maryland Heritage Tours), we regularly guide people through the cemetery on candle-lit history sojourns in late fall (and certain other times of year). Ron is the true veteran, however, as he has been leading the Downtown Ghost Tours of Frederick for over two decades. The nocturnal ambiance is a little better for cemetery tours, but the side streets of the 50-block historic district make for a perfect backdrop for some pretty cool and chilling tales about people and events from the past. Another unique night-time feature of Frederick City is the fact that our beloved town mascots, the “clustered spires,” forever keep alive the legacy of Barbara Fritchie and the nonagenarian’s supposed interlude with Gen. Stonewall Jackson and his “Rebel horde” back in September of 1862. With the holiday season, our seats of city and county government are illuminated, as are the main thoroughfares of town (Market and Patrick streets) with annual decorating of trees with string lights. Frederick becomes a “festival of light” to use a well-worn cliché. Even the “old town creek” is lit, hosting the maritime players of “Sailing Through the Winter Solstice.”  Believe it or not, there once was a time when Frederick was “in the dark.” Certainly not figuratively or intellectually, but plain and simply devoid of light. People utilized candles by necessity, and it’s nice to see faux, electric candles these days in so many historic homes as part of holiday decorations. This gives us a glimpse, or should I dare say a “flicker” of what the scene may have resembled in the 1700s and early 1800s. Prior to the 1800s, lighting of streets was confined to only the most prosperous of communities, and was provided by torches or lamps which burned oils rendered from animal fat. While animal fat lamps were a blessing, they were also a curse, requiring daily scraping and cleaning to remove gummy deposits. With the exception of reflectors to diffuse (spread out) or concentrate the light, few improvements occurred in lamps until the late 1700s. In the 1780s, a Swiss chemist named Aime Argand invented a lamp with the wick bent into the shape of a hollow cylinder. Such a wick allowed air to reach the center of the flame. As a result, the Argand lamp produced a brighter light than other lamps did. Later, one of Argand's assistants discovered that a flame burns better inside a glass tube. His discovery led to the invention of the lamp chimney, a clear glass tube that surrounds the flame. During this period, whale oil, because it burned with less odor and smoke than most fuels, and colza oil, an oil from the rare plant, became important fuels for lamps. As a result, a thriving whaling industry developed to provide whale oil for lighting. In the United States alone, the whaling fleet swelled from 392 ships in 1833 to 735 by 1846. At the height of the industry in 1856, the United States was producing 4 to 5 million gallons of whale oil annually. Frederick finally “saw the light” in the spring of 1832. A town ordinance authorized the installation of 36 oil lamps. Up until this time, those venturing onto the unpaved muddy streets at night had to take lanterns with them, or rely on the lamps shining from store windows or taverns. Enter two former residents who were given the job to show others the way. Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht introduces us to them with a journal entry dated May 21st, 1832: “City Lamps. The corporation of Frederick some months ago appropriated money for the erection of lamps at the different squares in this City. They are, I believe now completed and this might well be for the first time. Mr. Clement Hilton and Mr. John Haller have been appointed Superintendents or lighters.” Now again, these were strictly oil lamps at the beginning. The lamplighter was employed to light and maintain the candle, whale oil and, eventually, Kerosene, known in those days as "Coal Oil", which was much easier to produce, along with being cheaper and smelling better than animal-based fuels when burned. Kerosene also did not spoil on the shelf as whale oil did. Gas lighting would become a reality in the late 1840s, and that is a story for another day and was spurred on by another Mount Olivet resident. Lights were lit each evening, generally by means of a wick on a long pole. As depicted below, a lamplighter is climbing a ladder to replenish the oil in the light. At dawn, they would return to extinguish the light. Early streetlights were generally solid candles or oil (and similar liquids) with wicks. These methods would eventually give way to gas lighting. So, I went in search of our first lamplighters. I didn’t learn much about their lives, but I did find their final resting places here in Mount Olivet. John Haller is buried in Area D/Lot 52 with his wife Mary Magdalene (Brown). He was born in 1796 and the couple lived in Bentztown, the area of Frederick around the intersection of Bentz and Patrick streets. Haller died relatively young at age 36, a victim of a cholera epidemic that ravaged the city (and country). Unfortunately, John Haller's time on the job was relatively short as his death date is September 22nd, 1832. Originally buried in the town’s Lutheran graveyard on East Church Street extended, he would be re-interred here in Mount Olivet. Mr. Clement Hilton, on the other hand, had a bit more longevity to offer in terms of life story. Clement G. “Clem” Hilton was born May 31st, 1779. He was the son of Thomas Francis Hilton, who had connections to Washington County, Maryland. Clemm married Ann Maria Christina Herrlein (1772-1833) on September 12th, 1800. The couple are buried together in the unique Area NN of the cemetery. This is where three local congregations removed decedents from the former Presbyterian, Methodist and Lutheran graveyards of town for reburial here around the turn of the 20th century. The Hiltons were part of the Evangelical Lutheran congregation who had two cemeteries on East Church Street, the original behind the historic church and stretching to East Second Street. The one in question, however, was the second burying ground that once existed on the site of today’s Everedy Square. More specifically, this cemetery was located on the southeast corner of East Church Street (extended) and East Street, across from today’s Frederick Coffee Company. The bodies, and tombstones, of Clem and Ann Maria Hilton appear to have been moved here in 1907, and are placed tightly next to one another, along with other remains that hail from the ancient Lutheran burial ground. Outside of that, Clement can be found in the early census records of town, but it’s been hard to discern his occupation until that of town lamplighter in 1832. Through Ancestry.com, I found that the couple had seven known children mature to adulthood, four of which I definitively found buried here in Mount Olivet. These include Ann F. (Hilton) Cole (1803-1877) in Area R/Lot 98; Henry Konig Hilton (1805-1887) in Area B/Lot 104; Susan Columbia (Hilton) Young (1810-1849) in Area B/Lot 123; and Rosanna E. (Hilton) Boyer (1817-1847) in Area NN/Lot 124. The other three Hilton children are Elizabeth R. Hilton (1800-1856), Mary Polly Hilton (1815-1886) and William Herrlein Hilton (1811-1849). I’ve exhausted my search on Elizabeth, was frustrated with my attempt to find Mary Polly, and William Herrlein gave me three options within the cemetery, but the birthdates are from the next generation down (being in the 1840s and 1850s). One of these was a local celebrity of sorts, or at best a town character, who was the son of the fore-mentioned “missing Mary Polly Hilton.” As for Clem’s son William Herrlein (also referred to as William Henry Hilton), I learned that he married a Baltimore girl in Charm City, and actually died in Washington, DC. An obituary says he was brought home to Frederick to be buried in the Lutheran Graveyard. My research assistant, Marilyn Veek, found that in 1831, Clement Hilton was indebted to his son Henry for $105, so to secure that debt he sold Henry a cow, a desk, a ten plate stove, four bedsteads, four beds and the necessary bedclothes, three shoats (young pigs), eight chairs, two tables, one looking glass, one meat tub, one large iron pot, a kitchen cupboard, three washing tubs, and all his kitchen furniture. The sale would be void if Clement paid off the debt in two years. Although the deed is marked "paid", Henry sold essentially the same list of items in 1836 to his older sister Elizabeth, to secure his debt of $125 to her. That debt was also paid off. Ann Maria Hilton died in 1833 at the age of 62 and was buried in the fore-mentioned Lutheran graveyard on East Street. As for Clement, Jacob Engelbrecht makes mention of additional appointments as lamplighter over the next few years. In 1834, he would be given the additional honor as “market master.” This has nothing to do with stocks, but more with the town Market House constructed in 1769. He was the supervisor of the Market House, which once stood on the site of today’s Brewer’s Alley Restaurant. This structure (and Market Space behind) was the mall of its day, containing stalls that could rented for people to sell their products to the town citizenry. This primarily consisted of farmers and butchers selling their food products. Scales could normally be found here as well in order to measure crop items such as hay, wheat and barley for resale. The Market House was also the home of early offices for the town of Frederick, and I read recently that a school for girls was conducted here at one point in the late 1840s. By 1835, Clement Hilton’s sole job was that as Frederick’s market master. In time, he would be given an additional assignment as town messenger. The Corporation appointed him to both posts for consecutive years culminating in March, 1846, two months before his passing on May 21st of that year. Clement Hilton was well respected in Frederick, but must have earned a positive reputation outside of town, as I found his obituary in the Baltimore Sun newspaper. Clement Hilton’s son, Henry Konig Hilton, never owned property either, but daughters (with unknown gravesites) Mary and Elizabeth Hilton certainly did. In 1850, they bought a property at what is now 232 East Church Street, which Mary sold in 1871. Pictured below, it is within arms-reach of the Old Lutheran burying ground that would hold their parents—temporarily of course. After residing on Church Street, Mary apparently lived in the United States Hotel, where she died in 1886. This building was located on the southwest corner of All Saints and South Market streets, and still stands today. Mary should be here in Mount Olivet, but I can’t find her grave in our database system. We have a Mrs. Hilton in the mass grave in Area MM which includes re-interments from the All Saints Protestant Episcopal Cemetery brought here in 1913. However, the only bit of information captured from an ancient tombstone (which no longer exists) was that this woman died on November 11, 1821. This is not our Mary, but could it be Clem’s mother? Presumably born in 1732, I doubt it, but could be wrong. I’d love to be able to identify the woman therein. I strongly think Mary Polly Hilton was buried at the Lutheran Cemetery, but had no gravestone, and was unfortunately lost in the move. A gentleman named Bill Hilton created a FindaGrave.com memorial page for her connected to our cemetery back in 2012 (Mary Hilton (1815-1886) with appropriate links to other family members we have discussed here. Perhaps Bill Hilton had information, or family lore, that we don’t? Our main precursor for a burial is an interment card, which we don’t have for Mary Polly Hilton. In doing a little more genealogy in my search for Mary Polly Hilton’s gravesite, I came up with the fact that she had a son. However, this gentleman would continue the family name of Hilton and was named for his maternal uncle who I theorize lived, died and is buried in Baltimore or DC. I could not locate a father, who may, or may not, have married Miss Mary Polly Hilton. The child, William Herrlein Hilton, has also turned up as William Hugh Hilton in certain records. He was born on New Years Eve of 1841. In addition to being a “Baby New Year,” I soon realized that I had made a connection to a gentleman I had stumbled over before. He is prominently pictured in one of the Historical Society’s photo books, and was the subject of a Frederick Magazine article in 2004. He is best known as “Uncle Billy,” and pulling on the holiday theme, I don’t know if his was truly “a wonderful life.” This gentleman appears in the early census records as an apprentice shoemaker in 1860, and a barber in 1863 (Civil War Draft information) and 1880. I’m assuming he received an education in local schools, but can’t be sure, along with living with his mother and aunt on East Church Street. I also found that he married Miss Emma Melissa (Kimmell) Hilton (1851-1898) on January 3rd, 1888, and had a son. Maurice Clement Hilton was born in 1893 and moved to Pennsylvania where he spent the bulk of his life. Upon his death in 1916, he would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet next to his mother. Unfortunately, we don’t have the 1890 census to assist us with William H. “Uncle Billy” Hilton’s profession. I couldn’t find him in 1900 or 1910 either. I do know from several newspaper articles of the 1890s that he had given up his clipping shears for baker’s whisk and mixing bowl. He was known near and far for his flour-based creations. Uncle Billy Hilton was also captured in the poetry of Folger McKinsey, the Bentztown Bard who started his career in Frederick and transferred to the Baltimore Sun. We are lucky to have two photographs of Uncle Billy. The first is part of Heritage Frederick’s amazing collection and was taken by Charles Byerly. It is featured in Frederick County Revisited, published by the Historical Society of Frederick County (aka Heritage Frederick) in 2004 with the caption included. Another photo was included with the 1976 Bicentennial supplement of the Frederick Post. A story told of Uncle Billy’s unique operation of selling pretzels around town. He was certainly a town legend of yesteryear—maybe not holding the national prestige of Bryan Voltaggio, but in a time without radio, television and social media, he was pretty darn close on the local level. Uncle Billy also had flaws, and this was well known. He was frequently drunk and had mishaps that were covered in the paper. He continually made trips to the Montevue Hospital and home north of town. One such event led to a rumor reporting that Uncle Billy was dead. This was quickly debunked. Billy Hilton did get really sick in 1914 and passed on August 10th, 1914. He outlived his mother and wife, and apparently was estranged from son, Maurice Clement in Pennsylvania. It was thought that “Uncle Billy” would be buried in a pauper’s grave at Montevue. However, Frederick’s sitting mayor (Lewis Fraley) and a leading attorney (Leo Weinberg) could not let such a “shining light” as “Uncle Billy” not be buried in Mount Olivet. They would garner the amount necessary ($35) to bury Uncle Billy with dignity in proximity to other relatives. “Uncle Billy” Hilton is in Area M/Lot 26. This particular part of the cemetery, north of Confederate Row, was once called “Stranger’s Row.” This was a place for destitute individuals and unknown guests to town who unfortunately expired while here and far from family and native homes. He has never been given a gravestone, but his mortal remains are here among others of the same plight. As Hilton family member’s “life lights” were illuminated, they were also naturally extinguished in due time. The same fate will soon take the beautiful holiday lighting from our homes, city streets and creek. But don’t worry, there’s always next holiday season in 11 months, and it will be here in a flash.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed