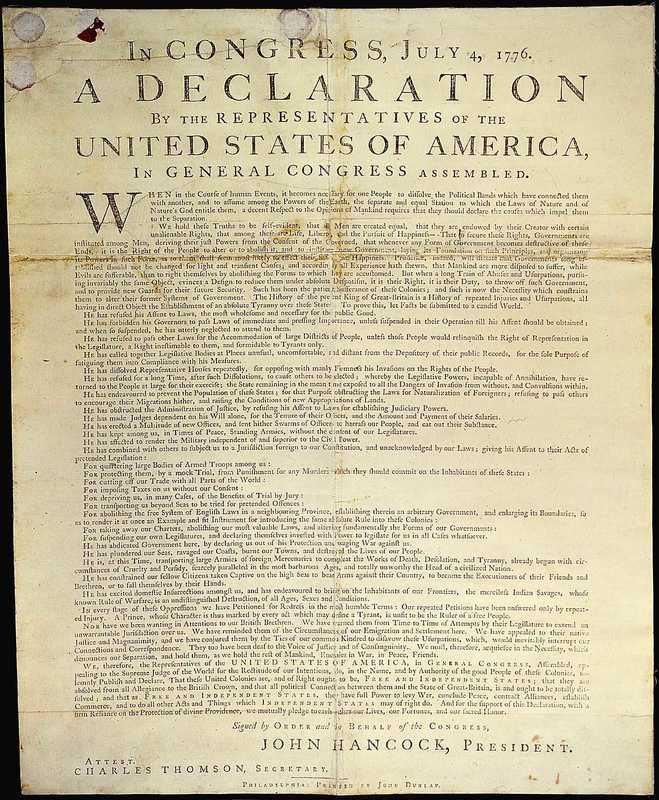

Trumbull's masterpiece "The Declaration of Independence, July 4th, 1776" Trumbull's masterpiece "The Declaration of Independence, July 4th, 1776" The town of New Castle, Delaware was bubbling over with nervous excitement in early July, 1776. Three weeks earlier on June 15th, the Assembly of the Lower Counties of Pennsylvania met here in the courthouse and declared itself independent of British and Pennsylvanian authority. This brash action thereby created the state of Delaware, as it hadn’t even existed as an independent colony under British rule. Since 1704, Pennsylvania had two colonial assemblies: one for the “Upper Counties,” (originally Bucks, Chester and Philadelphia), and one for the “Lower Counties on the Delaware” (New Castle, Kent and Sussex). All of the counties shared one governor. Now, New Castle was chosen the new capital of Delaware. Meanwhile just up the Delaware River in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress was convened and discussing a permanent break with Great Britain. On July 4th, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, which proclaimed the independence of the United States of America from Great Britain and its king. Contrary to popular belief, the legendary convention of delegates adopted Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence from Great Britain on July 2nd, not July 4th. Furthermore, the document wasn’t signed by all delegates on July 4th as has been assumed, partially thanks to John Trumbull's iconic depiction. Most of the signatures were pledged and affixed one month later on August 4th, while some autographs wouldn’t be gotten until October and November. Two individuals did sign off on the corrected draft on July 4th, 1776 after edits were properly made. These were John Hancock, President of the 2nd Continental Congress, and lesser known Charles Thomson, Secretary to the Continental Congress. The day we celebrate each year is the day that these gentlemen signed the rough draft, and delivered to the official printer, a man named John Dunlap. Finished copies of the Declaration of Independence were brought to the Pennsylvania State House (later named “Independence Hall”) on July 8th. Philadelphia citizens were summoned for the first public reading of the document by the ringing of a very famous bell, one which had announced the battles of Lexington and Concord some fifteen months before.

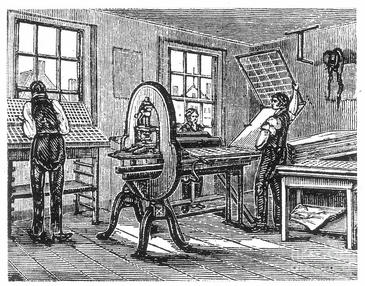

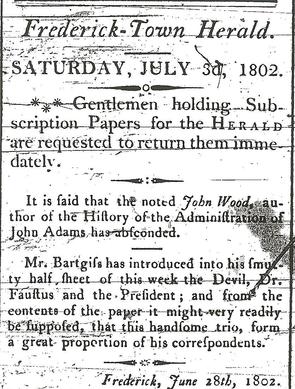

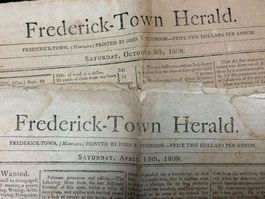

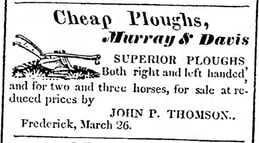

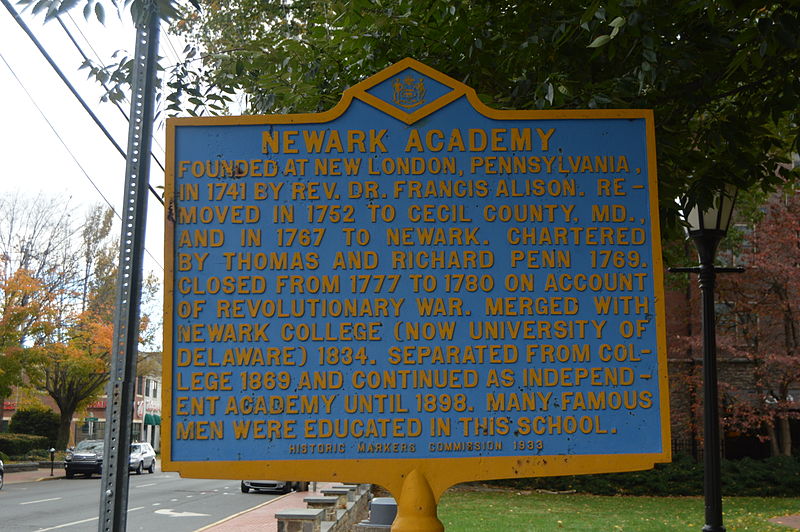

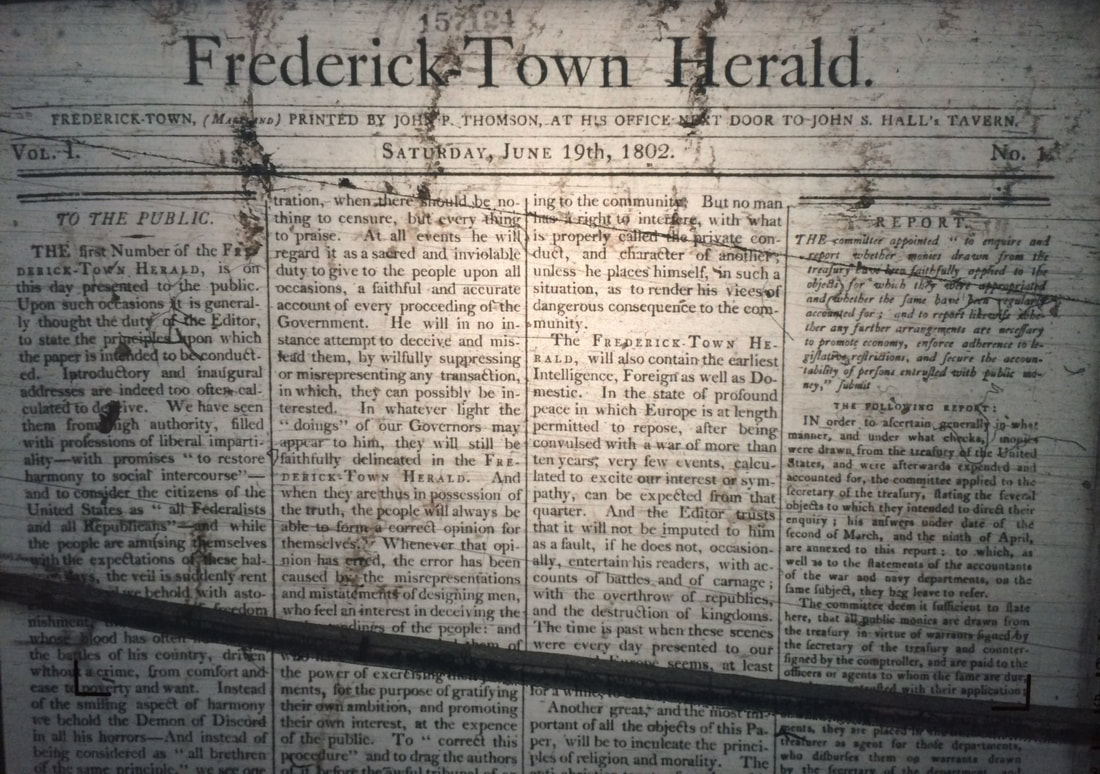

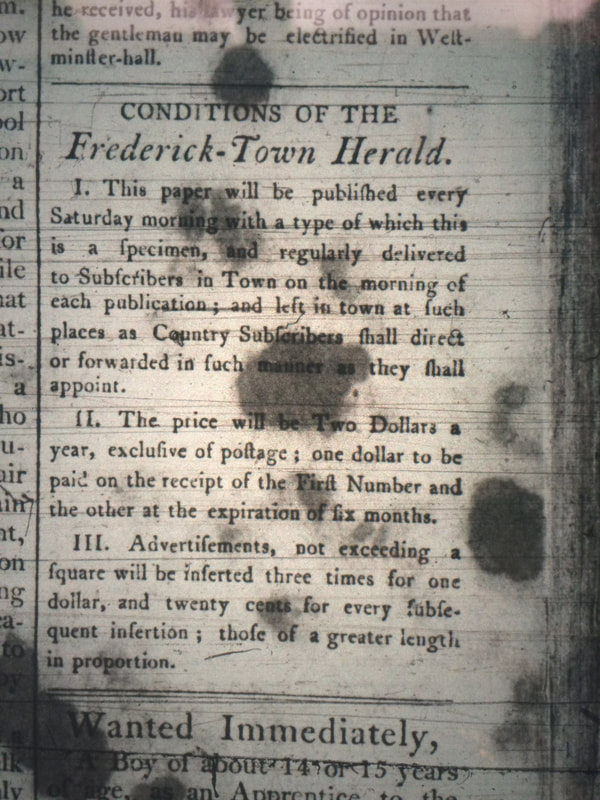

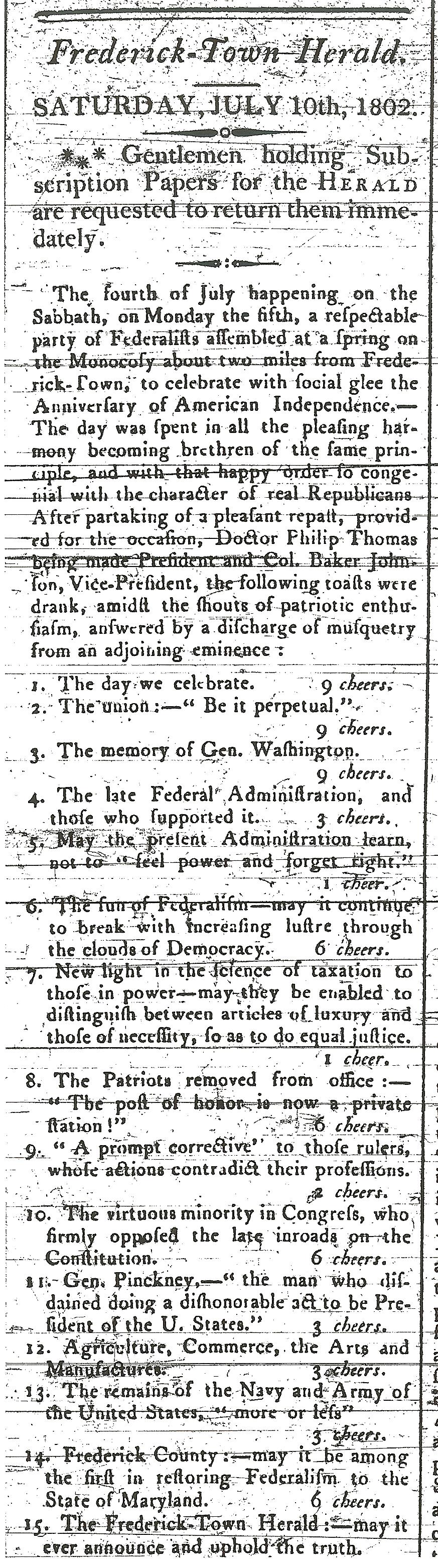

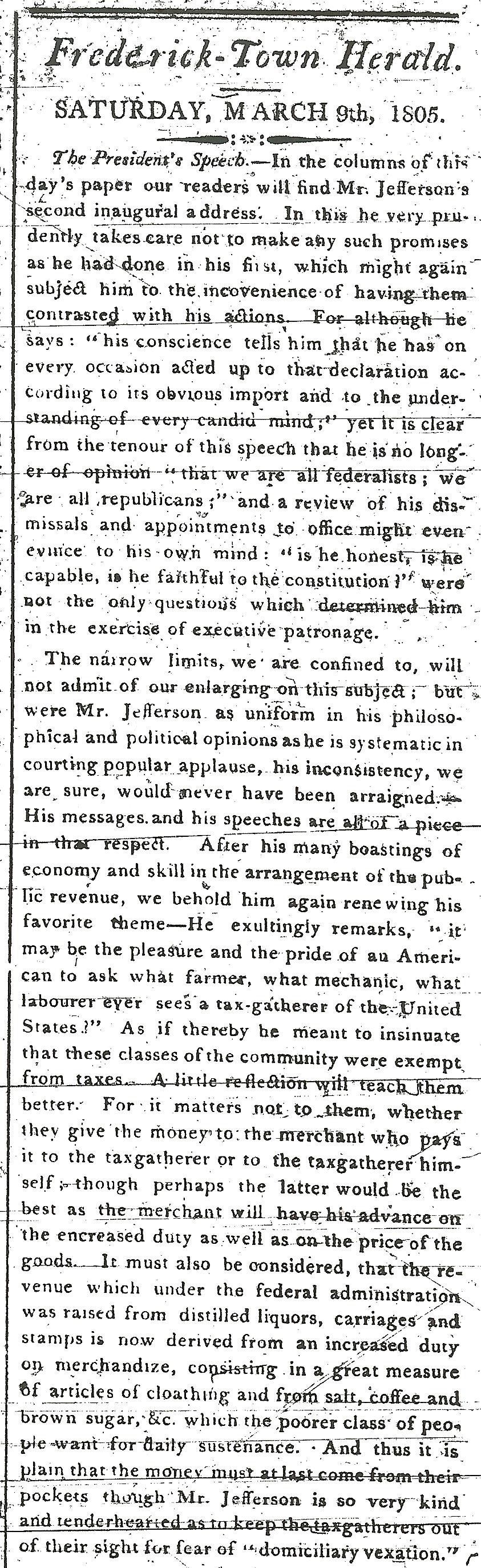

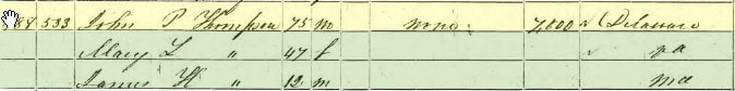

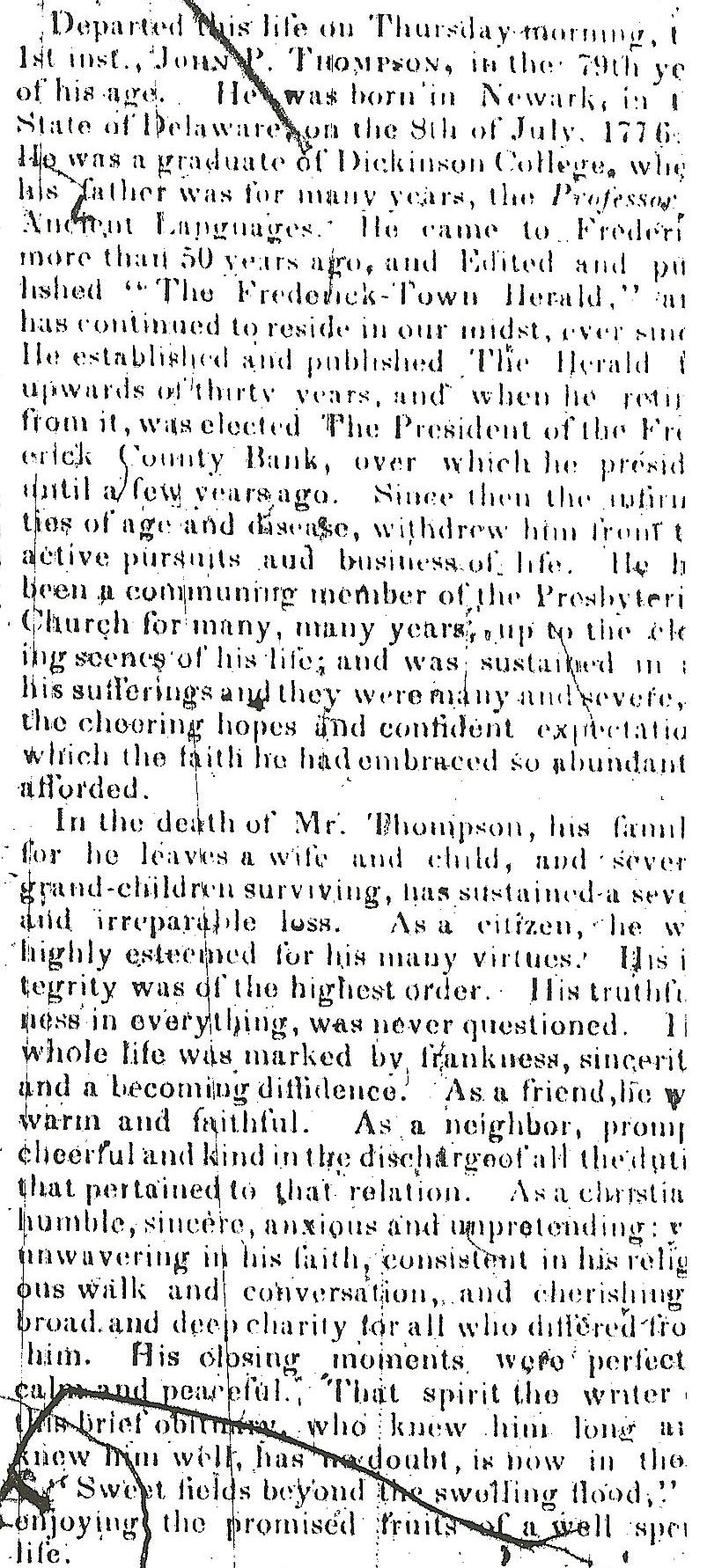

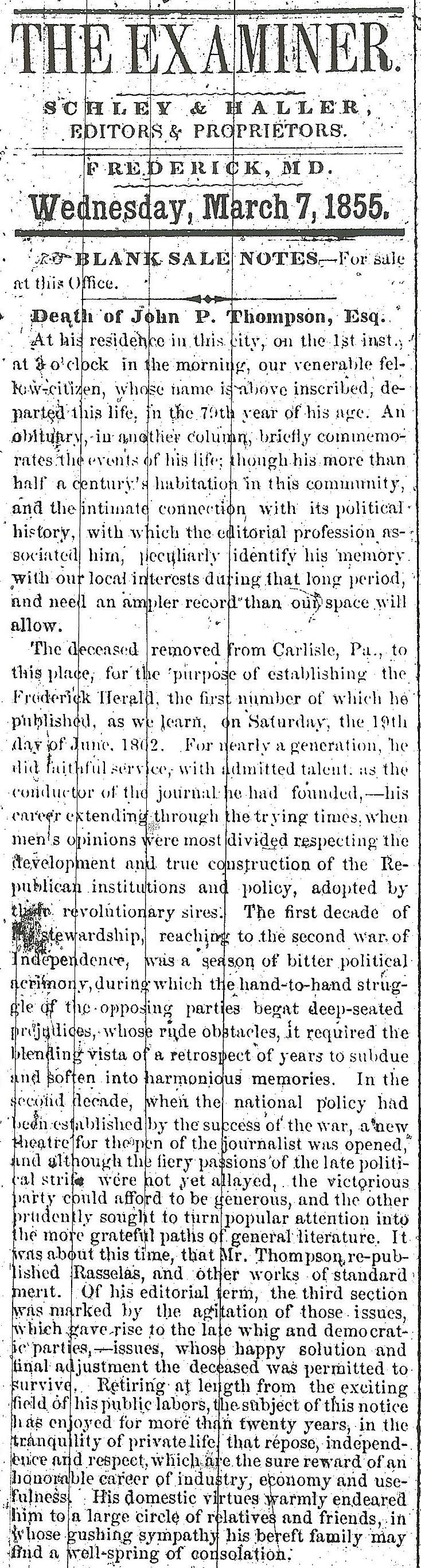

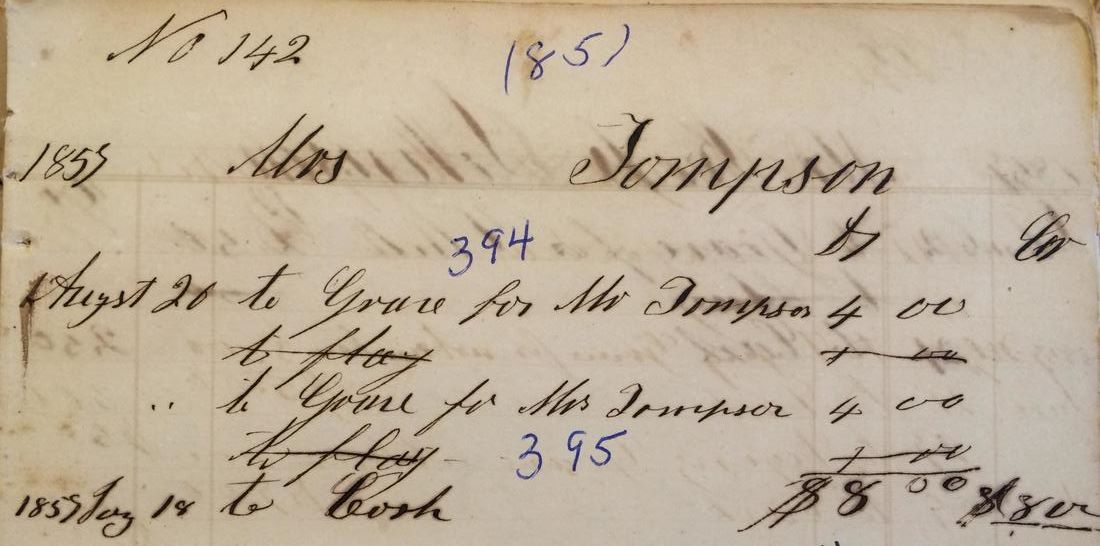

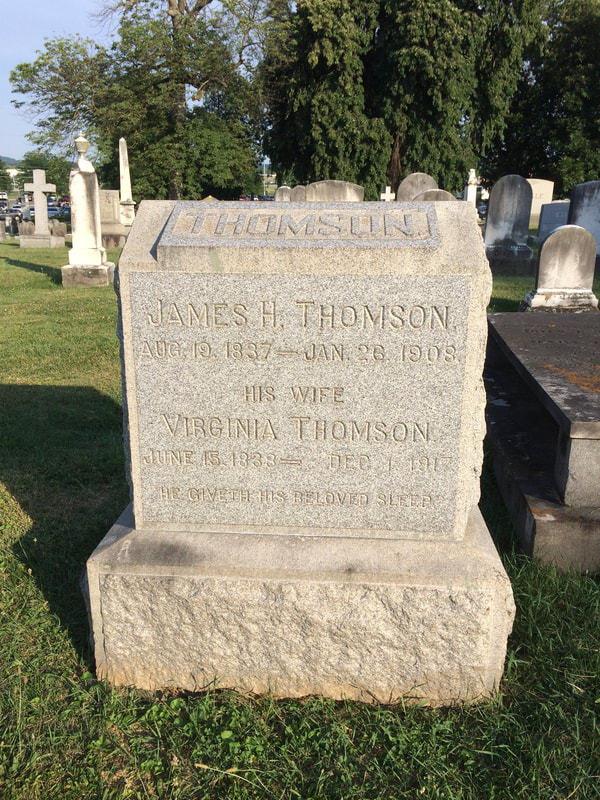

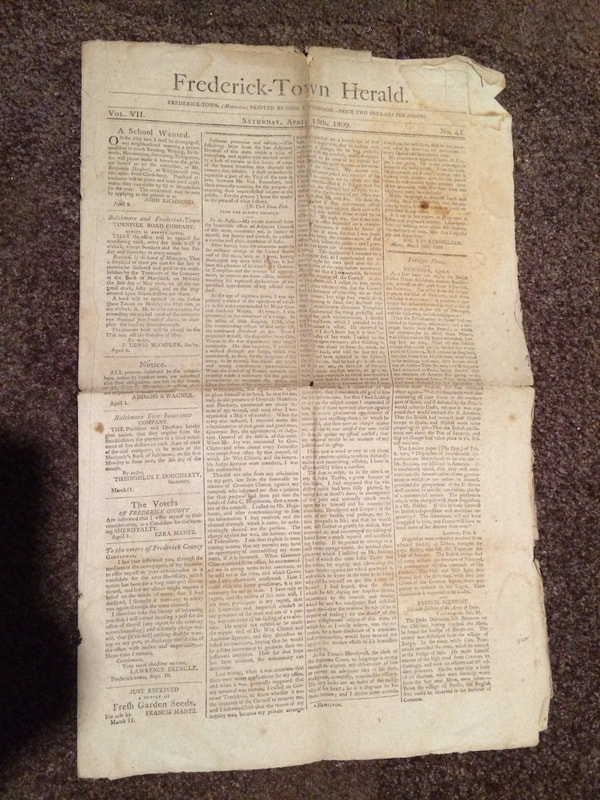

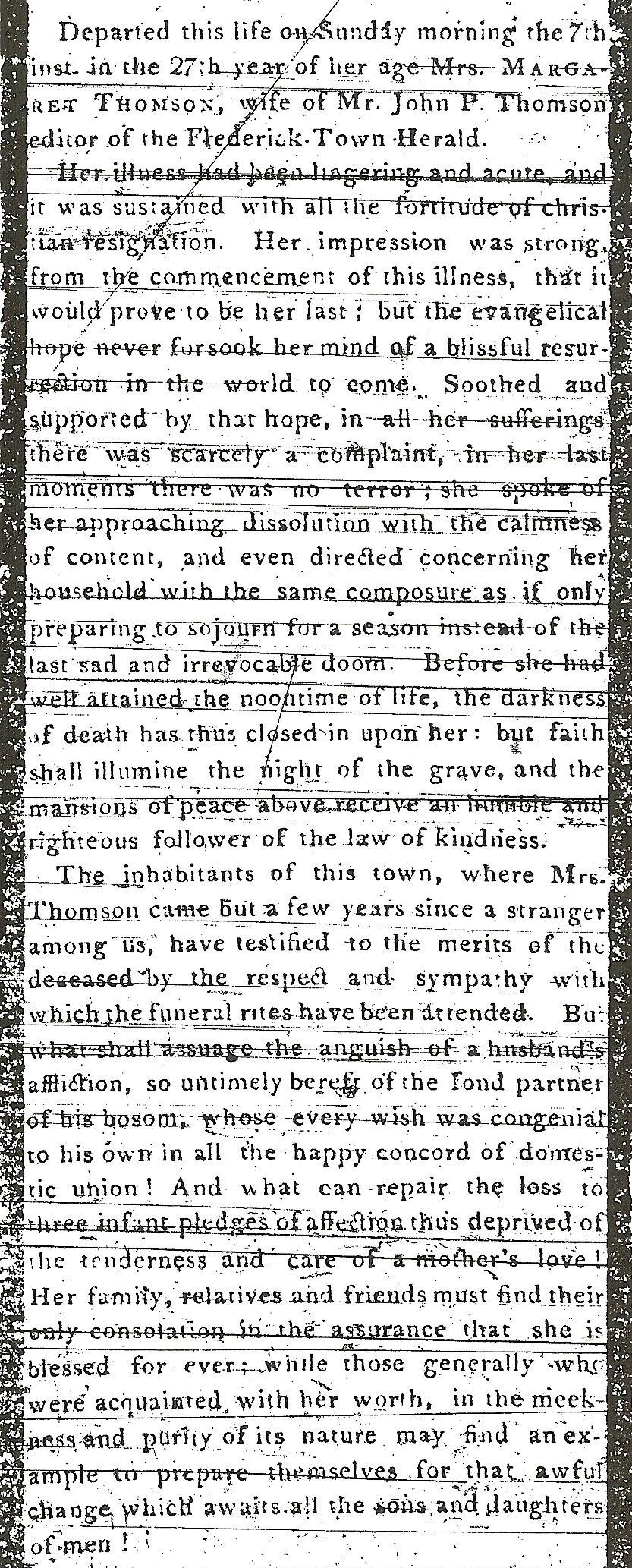

CharlesThomson's grandson would also declare his own independence of thought to the masses, criticizing some of the almighty 1776 signers in the process, especially the man who receives the majority of credit for authoring the Declaration— first presented to public audiences on the day of his birth. John Popham Thomson Future Frederick resident, John Popham Thomson was born to William and Margaret Thomson. William was the son of Continental Congress Secretary Charles Thomson. At the time of young John's entrance into this world, soldiers under Col. John Haslet’s Delaware Blue Hen Regiment came from Wilmington and “took out of the Court House all the insignias of the monarchy…all the baubles of royalty and made a pile of them before the Court house…set fire to them and burned them into ashes and a merry day we made of it.” John’s life was just as colorful as the events surrounding his birth. His first seven years were spent during the American Revolution. His father, William Thomson, was a 1772 graduate of the nearby Newark Academy, a continuation of Rev. Alison's New London endeavor. He married Miss Margaret Popham three years later. Mr. Thomson would become the principal of his alma-mater, having re-opened the school (because of a closure due to the war) in 1780. He remained here until 1794, at which time he and Margaret moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania to take the post of Professor of Languages and librarian at Dickinson College. William Thomson would become the principal of his alma-mater, having re-opened the school (because of a closure due to the war) in 1780. He remained here until 1794, at which time he and Margaret moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania to take the post of Professor of Languages and librarian at Dickinson College. This school had been founded by Declaration of Independence signer, Benjamin Rush, and named for another, John Dickinson. Things got off to a rocky start. In 1795, family friend Henry Ridgely wrote a telling letter home describing the state of the affairs for the Thomsons in their new home: "Mr. Thomson has been very sick since he has been at Carlisle, and kept his bed light on nine days, and Mrs. Thos. had the ague and fever, and James Thomson fell over a cellar door and broke 3 of his ribs.” Henry (Ridgely) and his brother George had been "under (the) care and tuition" of William Thomson at the Newark Academy in 1794 and had been sent by their mother to Dickinson to be under the same by the educator. As can be imagined, William’s son, John Popham Thomson, would experience a great educational upbringing. He would attend his father’s school, Dickinson College, and graduate with a law degree in 1797. Although well-versed in law and politics, John P. Thomson chose journalism and would soon embark on an illustrious, lifelong career as a newspaper publisher. The 23-year-old founded The Eagle or Carlisle Herald newspaper on October 3rd, 1799. It was mockingly labeled a “Tory paper” by critics for its Federalist stance and anti-Jeffersonian sentiment. John Thomson ran the paper while simultaneously performing duties as Carlisle, Pennsylvania’s postmaster. (John's grandfather Thomson had held the role of Postmaster General for the US under the Articles of Confederation.) Unfortunately, Thomson was soon fired from the postmaster gig, forcing him to give up the newspaper. The cause of dismissal resulted from his editorial attacks on President Thomas Jefferson (within the paper). A fellow publisher wrote in March of 1802 that Thomson: "proposed that the grand jury then sitting would present the election of Mr. Jefferson as a national curse." A competing newspaper in March ran the headline: "O Johnny Thomson, Johnny Thomson O!" upon hearing that John demanded to know why he was fired as town postmaster. The rival paper went on to call Thomson’s paper "slanderous." This was a major setback for the Delaware native, but John P. Thomson would not be unemployed for long. Several prominent citizens of Frederick asked the young publisher to move south and set up a Federalist paper. These included Judge Richard Potts and John Hanson Thomas, son of Dr. Philip Thomas and grandson of John Hanson. Thomson’s friend and former Dickinson classmate Roger Brooke Taney had come to Frederick a few years prior, launching his illustrious law career here. The new town newspaper would take the name of the Frederick-Town Herald.  John P. Thomson's printing office and headquarters was advertised as being next to John S. Hall’s tavern. I place this tavern on the northwest corner of N. Market and W. Church streets, location of today's Tasting Room restaurant. The next door (to the north) was the Frederick-Town Herald office, also serving as Thomson’s home address in the beginning. This would have sat on the footprint of present day Firestones restaurant. The first issue of the Frederick-Town Herald hit the streets on June 19th, 1802. The inaugural edition contained a long three-column preamble by Thomson explaining his political and editorial beliefs. He said that he supported Washington and Adams, but views "...with horror the late unpardonable attack of the Legislature on the independence of the Judiciary - an attack, that had proved but too successful, and which had effectually demolished one of the great pillars of the Constitution." John Thomson reassured readers that: "...he will in no instance attempt to deceive or mislead them, by willfully suppressing or misrepresenting any transaction." Maryland historian/writer Walter Arps labeled Thomson "...an unabashed polemicist” in an article that appeared in the spring, 1979 edition of the "Maryland Magazine of Genealogy” (vol. 2, #1, p. 30). Arps went on to say: “His (Thomson’s) chief target was Thomas Jefferson, whom Thomson said was embarked on a systematic campaign of subtle denigration of the achievements of Washington and Adams." Arps continued claiming that Thomson accused Jefferson of being in cahoots with Napoleon Bonaparte when the two leaders solidified the Louisiana Purchase: "Mr. Thomson was enflaming the political passions of the good burghers of Frederick County. With Bonaparte terrorizing Europe and the Barbary pirates plundering American shipping lanes, as well as Thomson's weekly multi-column tirades, there was relatively little page space left in the Herald for local news."  Thomson did not waste time taking shots at competing newspaper publisher Matthias Bartgis Thomson did not waste time taking shots at competing newspaper publisher Matthias Bartgis Thomson was partially recruited to do battle with Matthias Bartgis (1756-1825) an established Frederick publisher of several weekly papers under various different names in both German and English. These included The Hornet (1802-1814), Bartgis' Republican Gazette, The Independent American Volunteer or Der Americanische Voluntair (1807-1808), and the General Staatsbothe (1810-1813). The Hornet possessed strong Republican leanings and carried the motto: "To true Republicans I will sing, But aristocrats shall feel my sting" Bartgis' Republican Gazette (1800-1820) generally avoided politics and lasted much longer than The Hornet. In 1811 Bartgis took his son, Matthias E. Bartgis (1791-1849), in partnership. A great rivalry was born between Bartgis and Thomson.  As one of the leading citizens of Frederick, his paper gave additional glimpses into the personal life of Thomson and his family. Sadly, unfortunate personal events were displayed for readers to see such as the death of Thomson’s oldest daughter Margaret in February of 1823—only 17 years old at the time. The Frederick-Town Herald also shared the obituaries of his first two wives: Margaret (Holmes) in 1809 and Mary (Barnhold) in 1832. Wife Margaret's obituary is included at the end of story.  The Frederick-Town Herald truly made its mark on Frederick as it thrived for three decades, where many competing newspapers folded. The weekly newspaper published on Saturdays had become a mainstay in the community, especially beloved by Federalists. Thomson passed the reigns to William Ogden Niles when he sold the paper in late 1831, likely influenced by the sickness/eminent death of his second wife, Mary. In his last edition, of October 23, 1831, the seasoned publisher and printer graciously thanked his patrons and readers, and made no apology for his rhetoric and conduct over the past three decades. John P. Thomson's name would next appear in the Frederick-Town Herald a few months later in March (1832) an advertisement offering agricultural implements for sale. One week later, the Frederick-Herald would run the obituary announcing the death of Mary Thomson. The Frederick-Town Herald would survive another 30 years under various publishers until its abrupt end at the start of the American Civil War. The paper was suppressed in 1861 for its political stance, at this time, showing Southern sympathies. The Herald had supported presidential candidate John C. Breckinridge, former vice-president and Democrat, in the highly contested election of 1860. Abraham Lincoln won by the electoral vote as Maryland had overwhelmingly been in support of Breckinridge as he took 46% of the votes (42,482) compared to Lincoln’s 2% (2, 294 votes). From that point forward, the paper, under publisher John W. Heard, vehemently supported the Confederacy until its demise, caused ironically enough, by the federal government’s order of prohibiting the postmaster to send it through the mail. In a letter written in 1836 by Thomson’s niece, she describes her “Uncle John” as being a banker who had lived in Frederick for more than 30 years. She talks of his son Charles choosing to be a farmer, and that his daughter Elizabeth had died. Lastly, she mentioned that he had remarried– "...for the third time about a year ago." At the occasion of the marriage, John was on the verge of his 60th year, while his new bride, Mary Lucas Hamner (1802-1857) was nearly half his age—born in the year Thomson started the Herald. The union produced another son, who would be named James H. Thomson (1837-1908). Retirement was a busy time for John P. Thomson. He dabbled in politics, being named to the National Republican Central Committee in 1832. Thompson could now devote more time to his place of worship, the Frederick Presbyterian Church. He also served as the President of Frederick County Bank, being elected president in 1833 and serving the institution up through the early 1850’s in this capacity. In 1850, Thomson held real estate valued at $7,000. He lived with wife Mary and son James in downtown Frederick within the Court House Square area, but it could have well been the original N. Market Street location of his printing business. Thomson’s will was fittingly prepared and signed at the time of his 76th birthday, in July 1852. The man born within “the Spirit of ‘76,” possessing a childhood amidst the Revolution and experiencing a young adulthood framed by the experiment of self-government for a new nation, would pass three years later on March 1st, 1855. He would be buried in the old Presbyterian graveyard, once located near the intersection of Fourth and Bentz streets. Mary Hamner Thomson would die just two and a half years after her husband in August 1857. Son James would purchase lot 47/Area E within Mount Olivet at this time. Mary was placed here and the dutiful son would have his father reinterred and buried next to his mother. A large ledger or tablet monument marks their gravesite. James and his wife would be buried here in time. In 1907, the Presbyterian Church purchased lots in Mount Olivet’s Area NN in advance of a mass removal of the bodies from their downtown graveyard. This occurred in 1907, and brought the mortal remains of Thomson’s first and second wives, along with daughter Margaret and John’s brother James (1778-1847) who followed his older sibling to Frederick-Town and worked as a teacher.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed