|

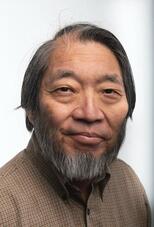

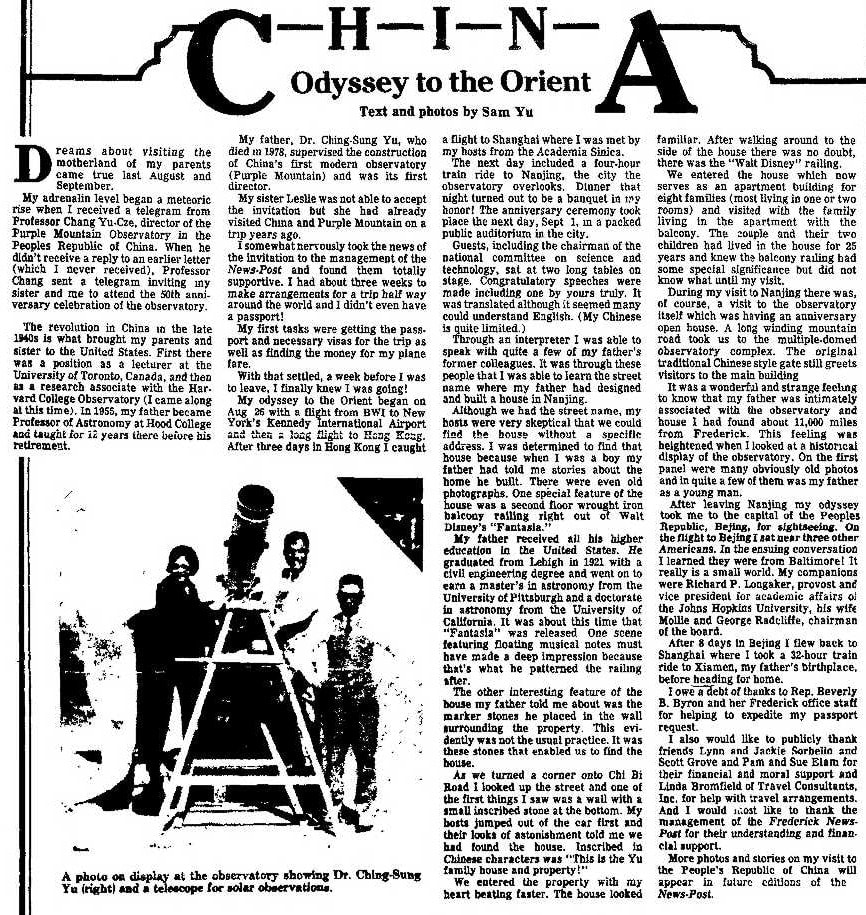

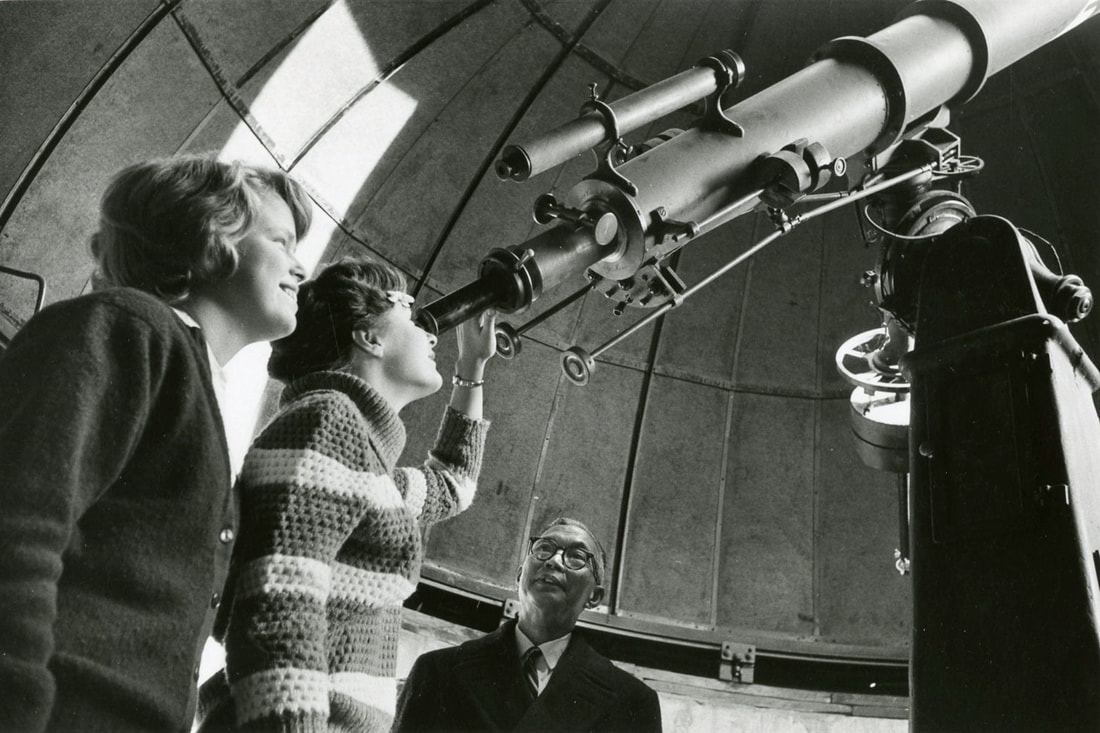

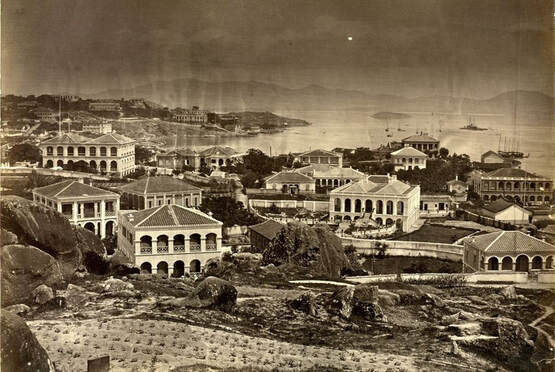

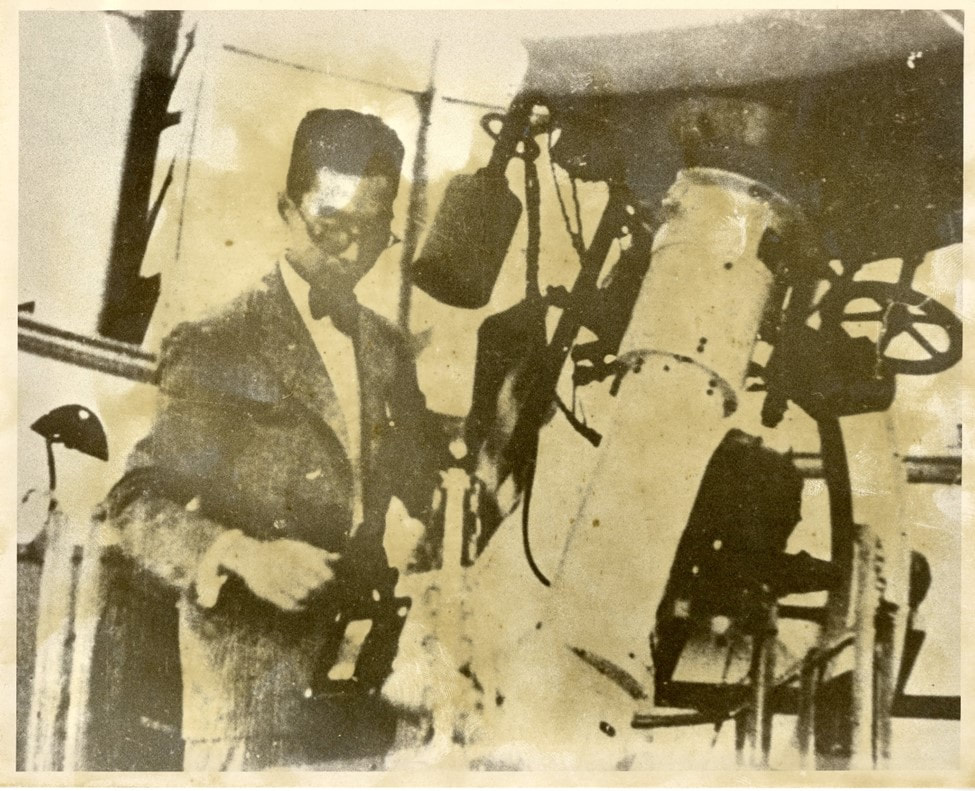

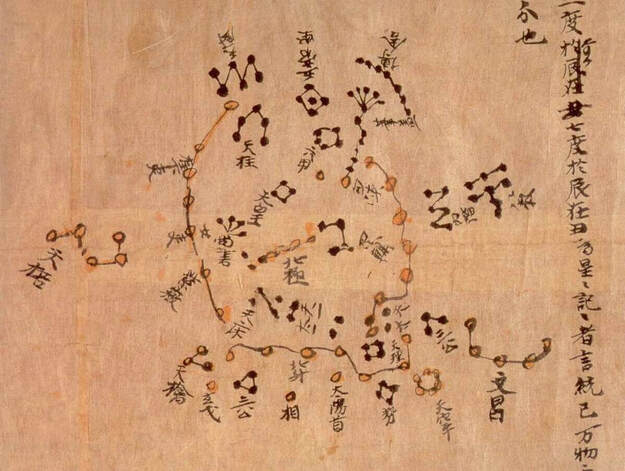

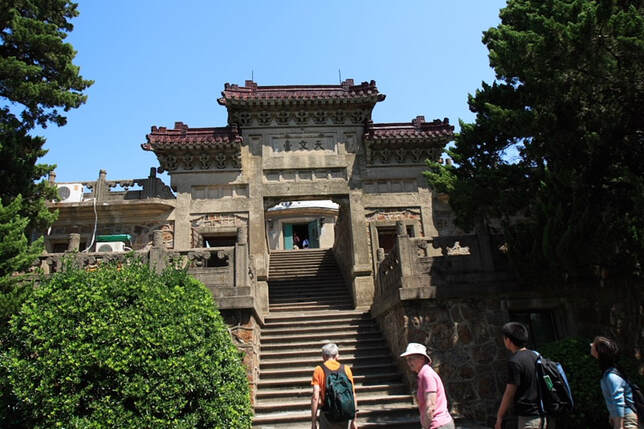

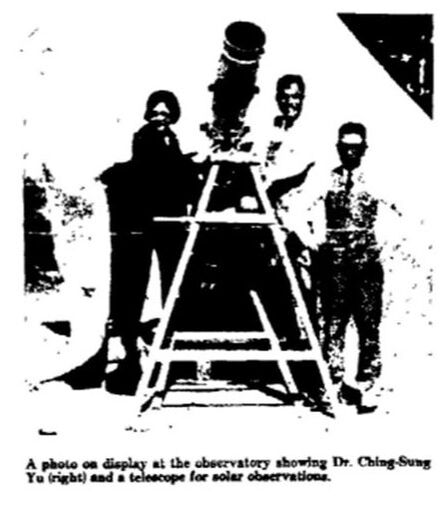

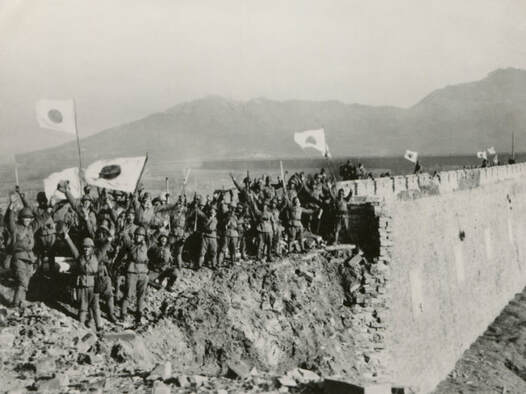

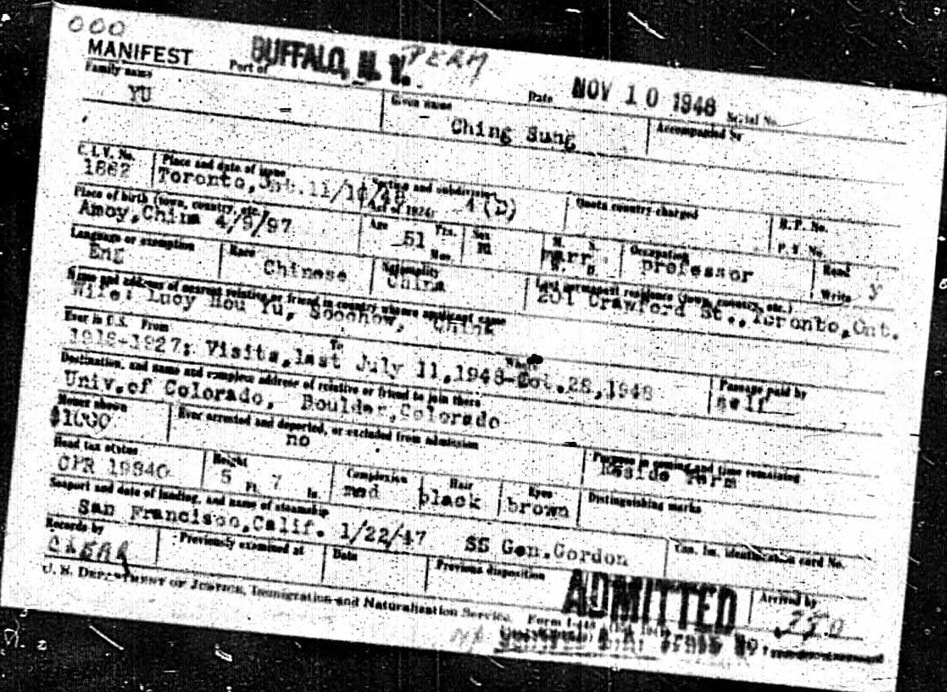

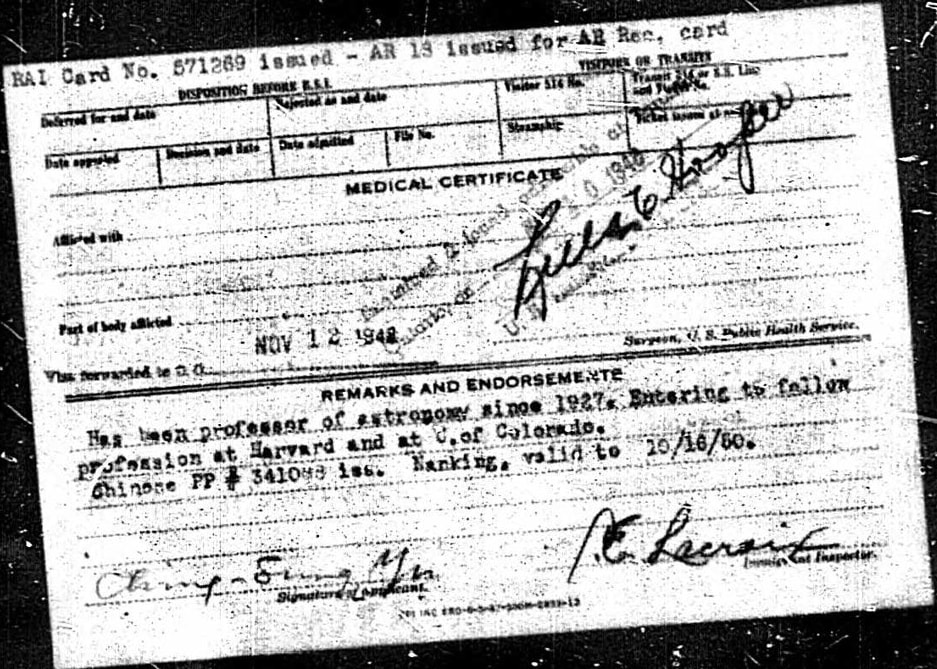

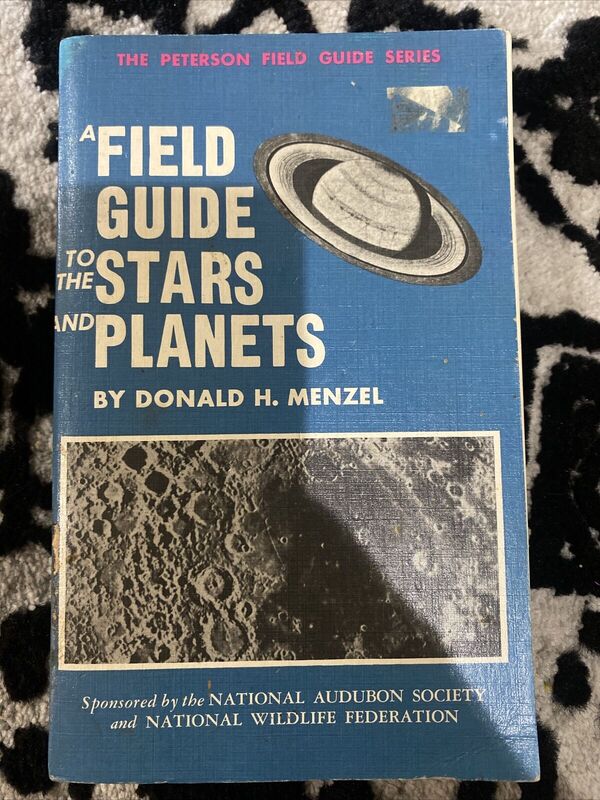

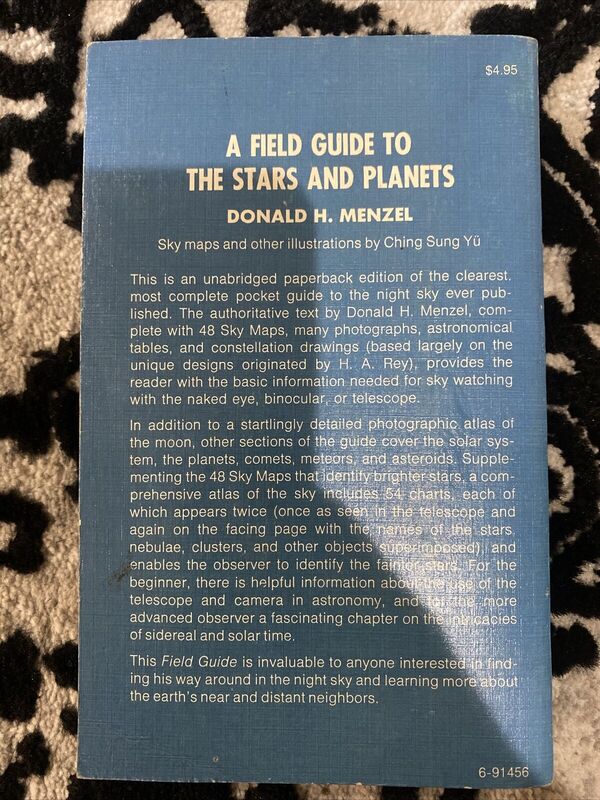

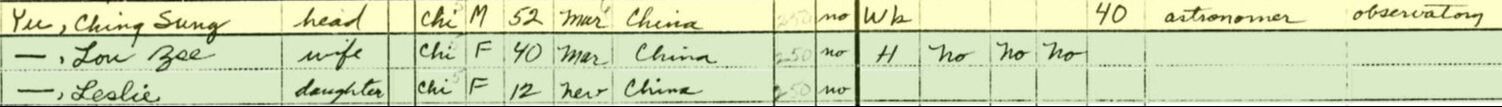

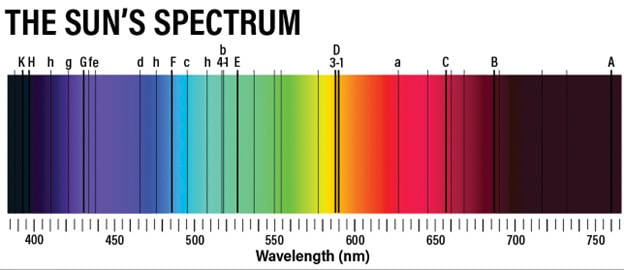

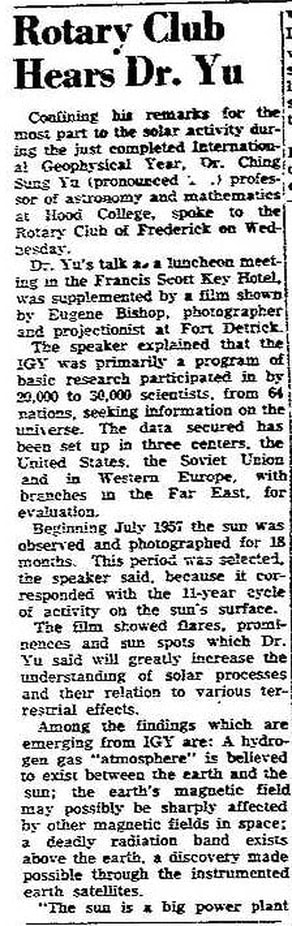

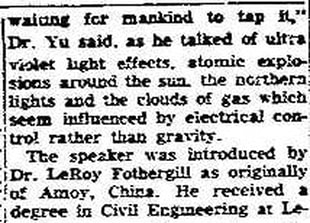

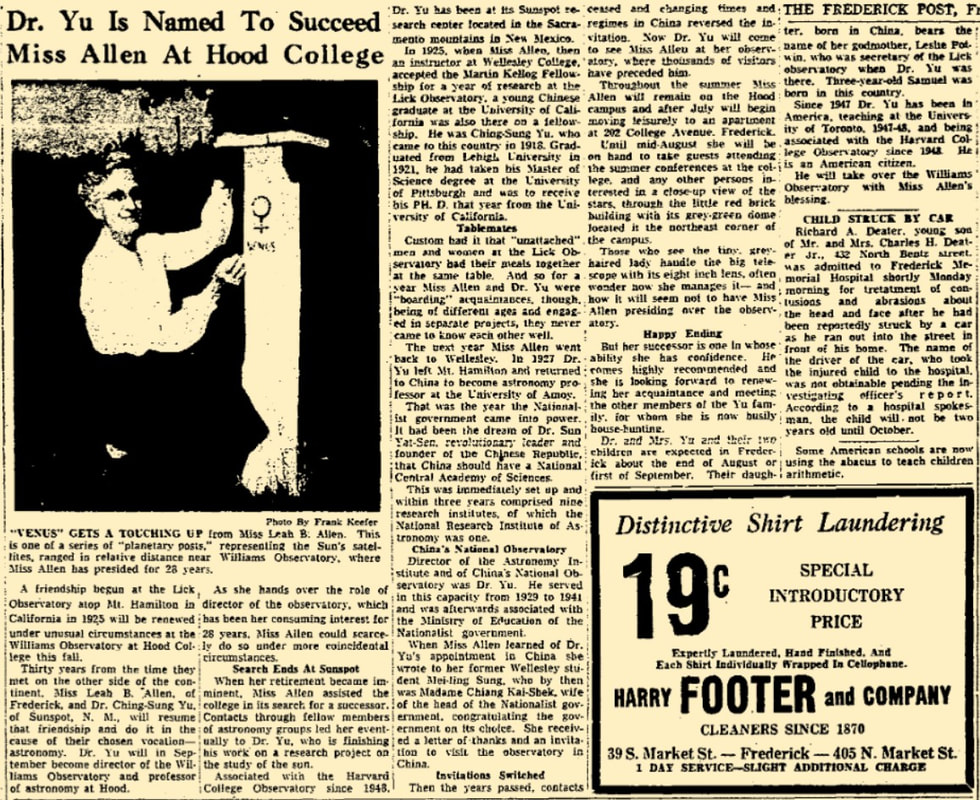

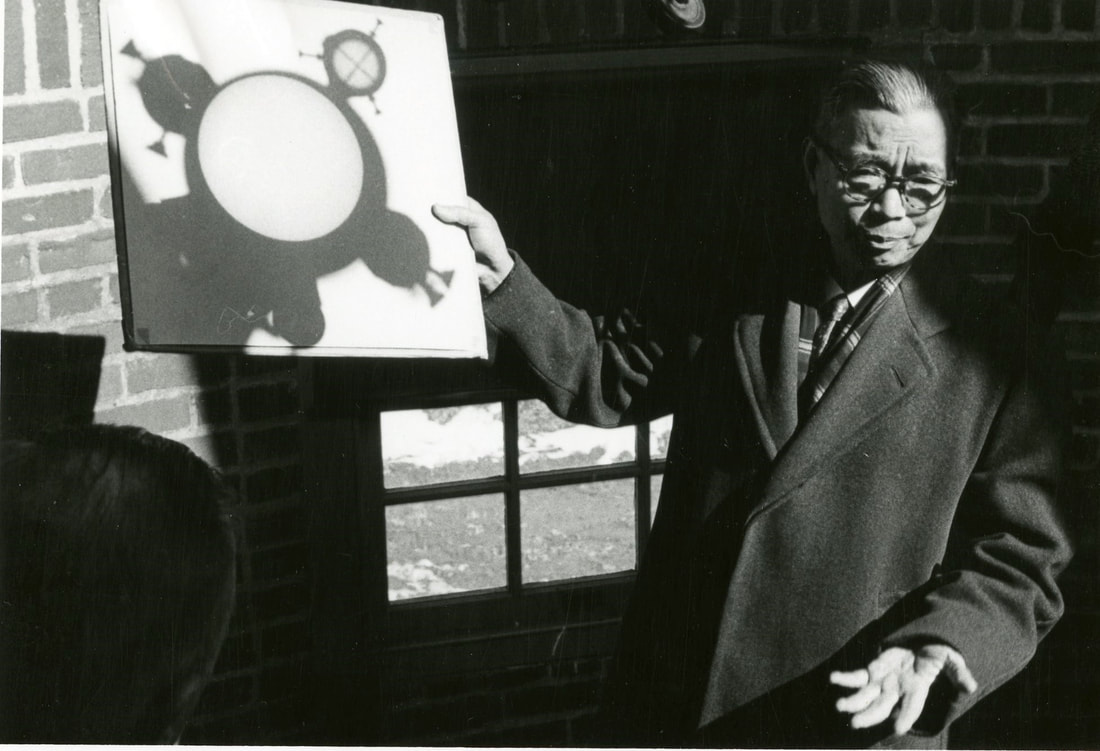

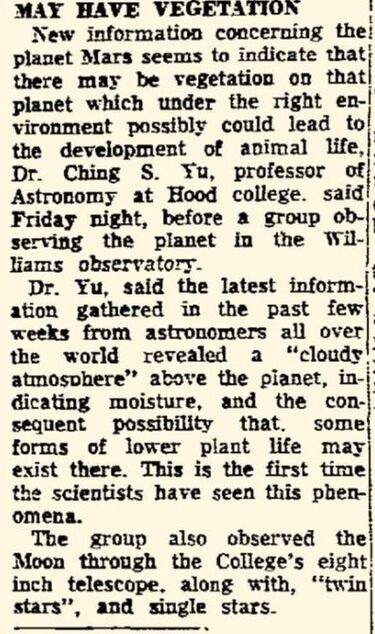

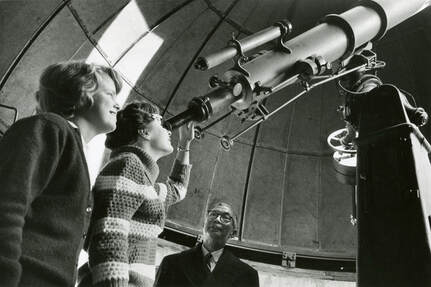

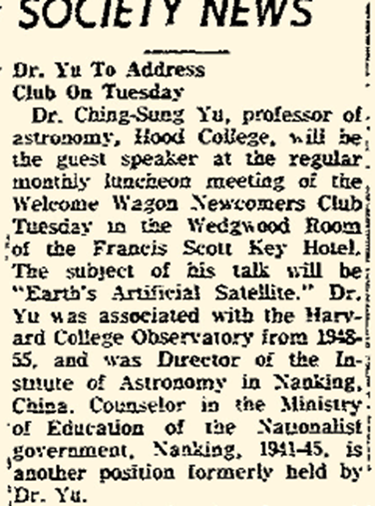

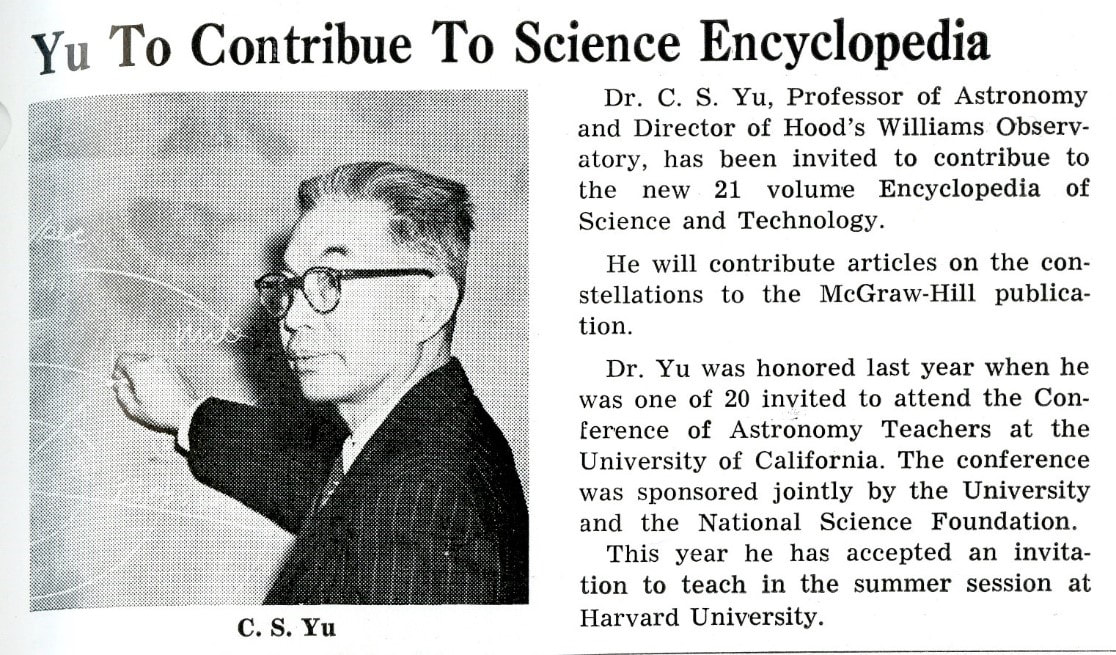

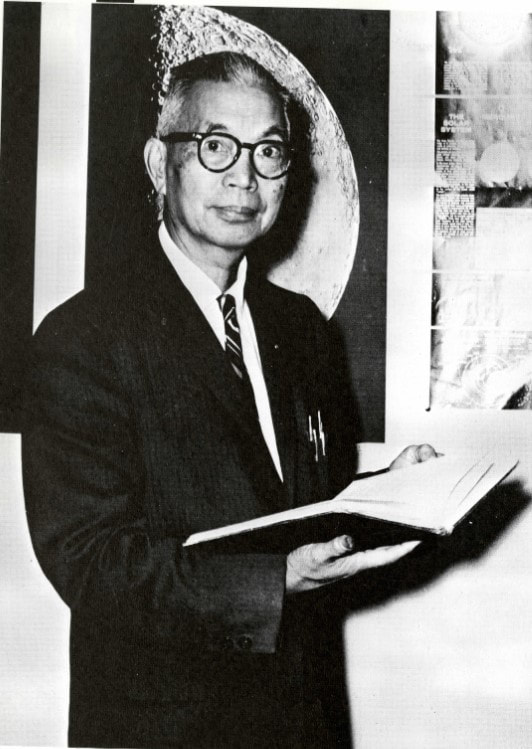

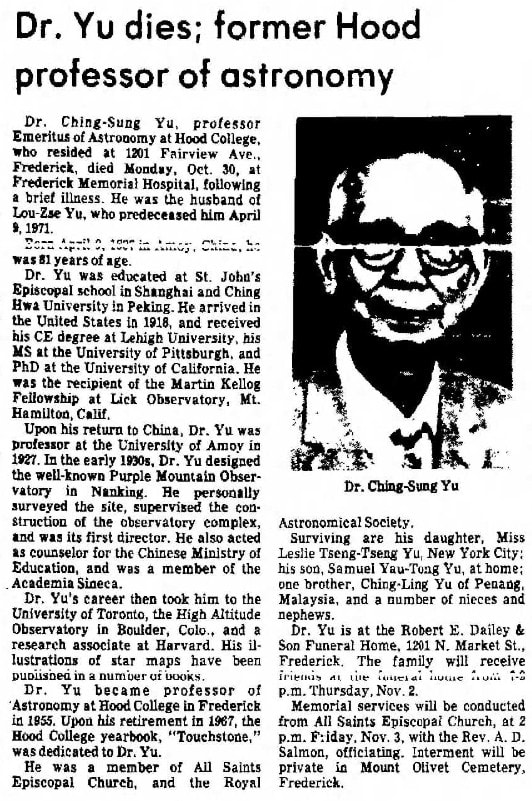

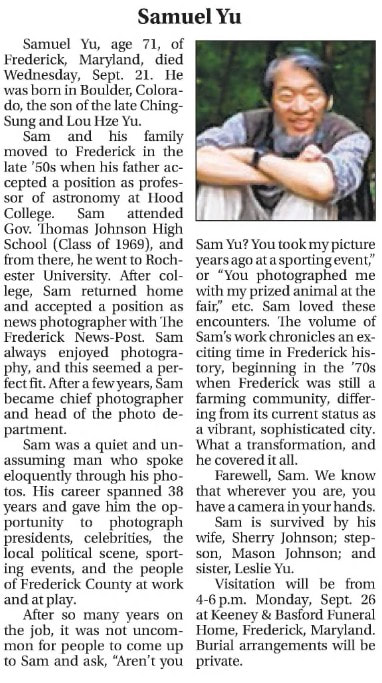

AUTHOR'S NOTE: The following "Story in Stone" was researched and written by Hood College senior Jake Frensilli as part of his internship with us here at Mount Olivet Cemetery (spring semester 2023) As some of the more astronomically inclined readers of this publication might know, SpaceX recently launched the largest rocket by weight in history. Furthermore, the progress of NASA’s Artemis mission should excite all Americans who care about our nation’s future in space. With all these recent advancements in space exploration, we should remember the debt we owe to the early pioneers in the field of cosmology. Without these intrepid explorers, our species would still be grounded here on Earth, and the beauty and immensity of space would still be hidden from us. One of these pioneering astronomers was Dr. Ching-Sung Yu, a Chinese-American cosmologist who worked at astronomical institutions all over North America before settling in Frederick County with his family. Dr. Yu was more than an astronomer; he was a modern-day Marco Polo. His profession many times took him across the Pacific, journeying between China and North America. During the early twentieth century, China was not yet the rising superpower it is today. Instead, by the turn of the century, China was still undergoing its “century of humiliation” at the hands of the Western powers. The nation that would eventually become the People’s Republic of China was then fractured into over a dozen warlord states, with a weak federal government headed by the Kuomintang party from the city of Nanking (Nanjing). It was during this tumultuous period of Chinese history that Ching-Sung Yu was born. Dr. Yu came into this world on April 4, 1897, in the Western-dominated port city of Xiamen, then romanticized as Amoy. Living during these times was tough, and life expectancy was extremely short. By the 1920s, China was engaged in a protracted conflict with the communists, warlords, and colonial powers, chief among them the rising sun of the Japanese Empire. Despite the odds, the young Ching-Sung Yu survived, traveled to the United States in 1918, and earned his degree in civil engineering from Lehigh University in 1921. After earning his undergraduate degree, he chose to study astronomy, earning his master’s degree in that field from the University of Pittsburgh and a doctorate from the University of California. Despite the dangers, Dr. Yu returned to his home country in 1927 after acquiring an education in America. Dr. Yu was determined to revive China’s past astronomical glory. China had been one of the original great innovators of astronomical study; from the time of the first emperor during the third century B.C.E (before common era) until the Ming dynasty, China was the world’s foremost visionary nation in science and astronomy. The early accomplishments of Chinese astronomers were tremendous; these intrepid astronomical visionaries advanced humanity’s knowledge enormously. However, by the time of the “century of humiliation,” China’s preeminent place in science had been lost. Beginning with the Ming Dynasty, China initiated a policy of intellectual suppression and national isolation. The subsequent Qing Dynasty continued these repressive policies, and they ultimately doomed China, one the most powerful nations in the world, to a period of decline and domination by outsiders. Upon traveling back to China, Dr. Yu was one of the leading astronomical scholars in the country; he was one of the few astronomers in China with a prestigious Western education. Subsequently, the Kuomintang government awarded Dr. Yu with the position of Head of the Chinese National Observatory. Dr. Yu also became a Professor at the University of Xiamen and an important figure in the Nationalist government’s educational department. In the early 1930s, as Head of the National Observatory, Dr. Yu designed and oversaw the construction of the Purple Mountain Observatory, located adjacent to the city of Nanjing. This observatory was to have the most powerful telescope in the Far East outside of the Japanese Empire. The observatory was to be one of Dr. Yu’s proudest achievements; hundreds of astronomical bodies were discovered from the observatory while it was in operation. During this time, Dr. Yu built a life for his family in the then-capital city of Nanjing. Ever the industrious visionary, Dr. Yu designed his own home, incorporating elements significant to him and his love of American culture. Unfortunately, Dr. Yu’s success and good fortune would not last, and the long-standing conflict between the Chinese factions and the Japanese Empire finally erupted into open warfare in 1937, forcing Dr. Yu and his staff at the Purple Mountain Observatory to flee. However, Dr. Yu and his team were determined to prevent the observatory’s expensive telescope from falling into the hands of the Japanese, so they dismantled and hid the prize. Somewhere along the way, Dr. Yu married the woman with whom he spent most of his adult life, Lou-Zse Hou. Lou-Zse would follow her husband on his adventures across the world until her death in 1971, seven years before the death of Dr. Yu himself. Dr. Yu and Lou-Zse had two children while living in China, a son and a daughter named Leslie. Unfortunately, the Yu's son perished due to illness outside Nanjing while the family was fleeing the Japanese Empire’s encroaching forces. Dr. Ching-Sung Yu and his family escaped China and went to Canada for safety. Sadly, Dr. Yu seems to have been largely erased from the official history of the Purple Mountain Observatory and from the history of Chinese astronomy; his name is not listed anywhere on the PMO’s official website. Following the Yus' exit from their homeland, China’s civil war raged on until the communists eventually secured complete victory, causing the Kuomintang forces of Generalissimo Chang Kai-Shek to retreat to the island of Taiwan, where they remain to this day. However, Dr. Yu’s beloved Purple Mountain Observatory was located on the mainland, now fully controlled by communist forces. Less than a decade after their decisive victory in the Chinese Civil War, the People’s Republic of China underwent a chaotic period known as the “cultural revolution.” During this time, memories of the individuals who had served the Kuomintang government, as Dr. Yu had, were expunged from the records and erased, the individuals being declared “counter-revolutionaries.” This is likely the reason for Yu’s exclusion from the official history of the Purple Mountain Observatory. After Dr. Yu left China, his Purple Mountain Observatory was re-opened by the communists; astronomer Zhang Yuzhe would now run the institution. Eventually, due to the rapid urbanization in Nanjing during the late twentieth century, Purple Mountain Observatory would have to be closed; the light pollution from the mega-city prevented the telescope from working properly. Although Ching-Sung Yu would never again be the director of the Purple Mountain Observatory, his distinguished astronomical career was not yet over. Dr. Yu worked at observatories and astronomical departments all over North America before settling in Frederick, Maryland. More on that later as his journey from China would have a few stops in between. Dr. Yu and Lou-Zse wound up in Toronto where our subject gained employment at the University of Toronto and the David Dunlop Observatory there. After a few years, he would return to the United States, scene of his former collegiate studies.  Original High Altitude Observatory Original High Altitude Observatory Dr. Ching-Sung Yu moved to Boulder, Colorado in 1948 to work as an astronomer for Harvard and the University of Colorado . He practiced his craft at the High Altitude Observatory (later affiliated with National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR)). The NCAR's website provides this brief history of their work in Colorado with significant ties to Harvard University: "In 1940, Harvard graduate student Walter Orr Roberts and his doctoral adviser, astrophysicist Donald Menzel, founded a small solar observing station high on the Continental Divide in Climax, Colorado. Roberts' assignment at the observatory was to last only one year, but, with the country's sudden entry into the war (World War II), he remained at Climax as sole observer, making daily observations of the solar chromosphere and corona. These coronal observations from Climax, with their implications for potential disturbance of terrestrial radio communications, became essential to the war effort. From these small beginnings, the station evolved into the High Altitude Observatory and grew substantially after the war. In the late forties, HAO's laboratory and administrative facilities were transferred to the University of Colorado and the gentler climate of Boulder. In 1960, HAO formally became a division of a newly-established research institute in Boulder, the National Center for Atmospheric Research." Dr. Yu would study the cosmos with help from the Sommers-Bausch Observatory, today connected with the University of Colorado. The building was dedicated on August 27, 1953, during the 89th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, of which Dr. Yu was a member. The 17 foot, 10-inch Bausch refractor, originally from the Bausch & Lomb building in Rochester, New York, was installed in the dome the same year. Harvard University’s High Altitude Observatory also had office space inside the Observatory. Dr. Yu would be published in association with his High Altitude Observatory colleague Donald Menzel, as he helped co-author and provided illustrations.  While in Colorado, the Yus would be blessed with another child in addition to daughter Leslie. Samuel Yautung Yu was born in 1951, and his name should be very familiar to many in Frederick today. "Sam" Yu, as he was more commonly known, lived the majority of his life here in Frederick, graduating from Gov. Thomas Johnson High School in 1969. After attending Rochester University, he came back home to Frederick and eventually gained employment as a photographer with the Frederick News-Post, beginning in the early 1980s. He would become a well-known fixture of the community over his 38 years with the paper, holding the titles of Chief Photographer and Head of the Photography Department. Much of Dr. Ching-Sung Yu's work focused on heliology: the study of the Sun. Dr. Yu was chiefly interested in the study of the sunspots, which appear on the surface of the Sun as thousands of small (relatively speaking; some are larger than the entire Earth), highly dynamic, brownish dots. Dr. Yu also invented a new method of making photographic images of spectrographic slits. This is a considerable contribution to not only heliology but also to cosmology in general. Observing the spectroscopy of astronomical objects, such as the Sun, is how cosmologists determine what objects are made of; thus, any advancement in the field of spectroscopy is a monumental achievement.  In 1995, Dr. Yu left Colorado to come with his family to central Maryland in order to accept the directorship of the Williams Observatory at Hood College. Longtime readers might recognize the benevolent family for the Williams Observatory from a previous “Stories in Stone” article titled “Possessors of ‘Charity.’” In 1922, the Williams family bequeathed Hood College $30,000 for the construction of an “astronomical building;” thus, the Hood observatory was named in the family’s honor. This would be constructed in 1924. Dr. Yu would be taking the place of an old friend in the process. This was Miss Leah Brown Allen who had held charge of Hood's observatory since 1927. Having directed a much larger observatory, which he, himself, had designed, Dr. Yu was highly qualified for this position. As the Frederick News-Post article points out, Dr. Yu had also been friends with former director, Miss Leah B. Allen. Allen had personally sought out Dr. Yu for the position once she decided it was time to retire. Dr. Yu would spend the next two decades of his life, and the last portion of his professional career, as the director of the Williams Observatory. The Williams Observatory here in Frederick is not as powerful as the Purple Mountain Observatory but Dr. Yu still participated in new discoveries and strived to push the envelope of space science. We now know for certain, using advanced modern instruments and also having had the benefit of on-planet probes, that Mars does not have life on its surface. Regardless, Dr. Yu’s commitment to remaining on the front line of cosmology, even as he approached his retirement, is demonstrative of an insatiable scholar. By all accounts, Dr. Yu valued his time as the observatory’s director and enjoyed working with the students at Hood College, then an all-female student body. He also taught mathematics and geology while here. The Yus resided at 1201 Fairview Avenue in Frederick, which made for an easy walking commute to Hood and the observatory for Dr. Yu. In addition to raising his children into adulthood, h e was also an avid stamp collector, and boasted many from his two homes of China and the United States. Lou-Zse died on April 9, 1971. Dr. Yu would retire that same year, having had a remarkable and highly successful career that took him across the United States and the world. During his time in Frederick, Dr. Yu was an active member of the community and enjoyed informing people about developments in Astronomy and Cosmology. Dr. Yu never returned to China, and despite his enormous success in America, one has to wonder if he ever felt homesick for the nation of his birth? Ching-Sung Yu died on October 30, 1978, in Frederick, Maryland, and is buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery alongside his wife, Lou-Zse in Area KK/Lot 125. In recognition of Dr. Yu’s academic achievements, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada named an asteroid after the accomplished scholar in 1987 nearly a decade after his death. In 1985, Dr. Yu's son Sam made plans to see his parents' homeland. He would travel to China at the behest of the Chinese government, which, interestingly enough, was honoring his father’s work at this time. This trip was significant for Sam, who discovered his father’s house that he, himself, had designed. Sam spent more than a month in China, being “wined and dined” by important figures from both the Purple Mountain Observatory and the Academia Sinica. Sam returned and told the story of his landmark adventure in the Frederick News-Post through a wonderful photo-essay. Like his father, Sam would go on to have a tremendous professional career looking through a lens. Sadly, Sam Yu passed away at the age of 71 on Wednesday, September 21, 2022.  Frederick News-Post (February 19, 1985) Frederick News-Post (February 19, 1985) Special thanks to Mary Atwell, Archivist at the Hood College Archives, Leslie Yu (Dr. Yu's daughter) and Sherry Johnson (wife of Sam Yu) for their assistance with this article.

3 Comments

Sylvia Sears

5/13/2023 11:25:51 am

Great job Jake.

Reply

Lois Keller-Poole

5/13/2023 12:58:53 pm

This brought up so many good memories of my friend Sam and filled in many gaps that I did not know about his extraordinary father and family of origin.

Reply

NANCY M DRONEBURG

5/14/2023 05:53:02 pm

very informative especially the history lesson.. Thank you

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed