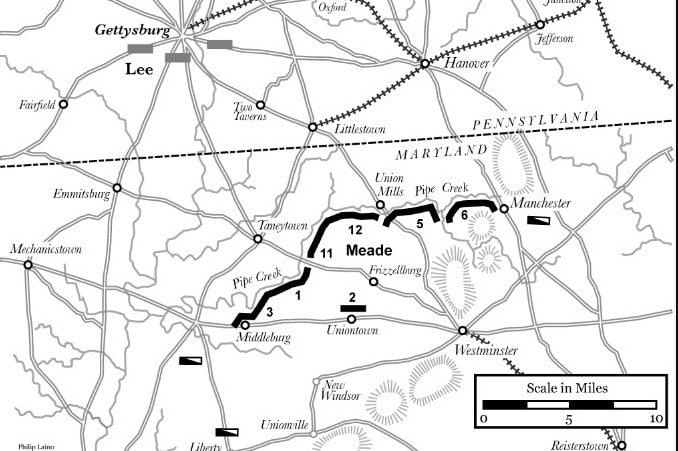

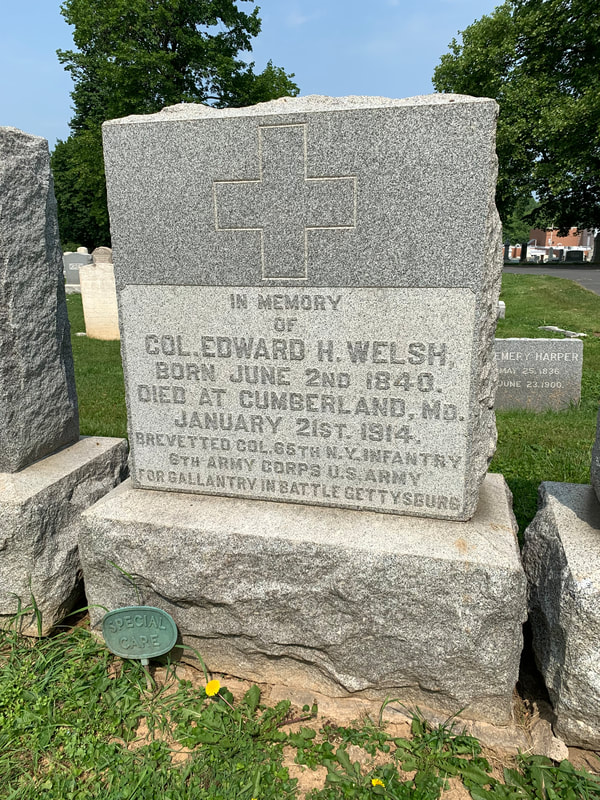

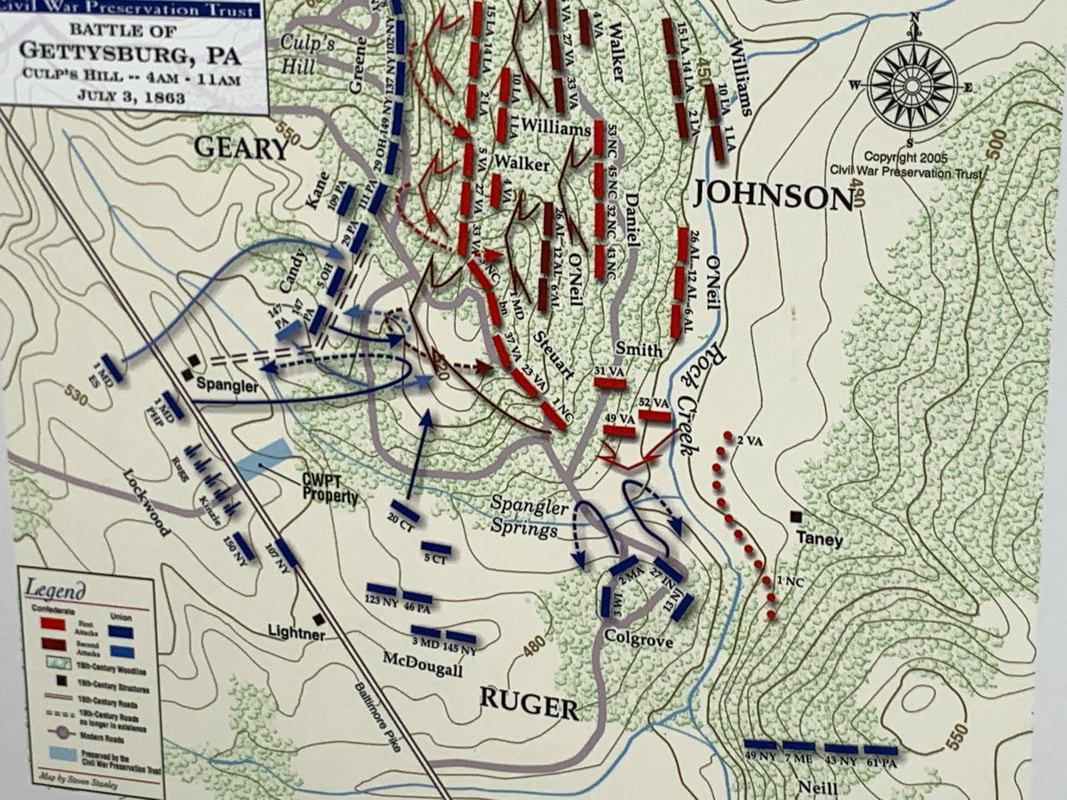

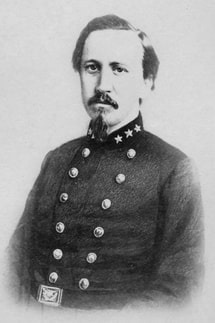

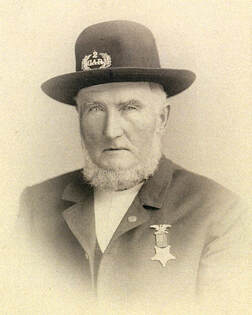

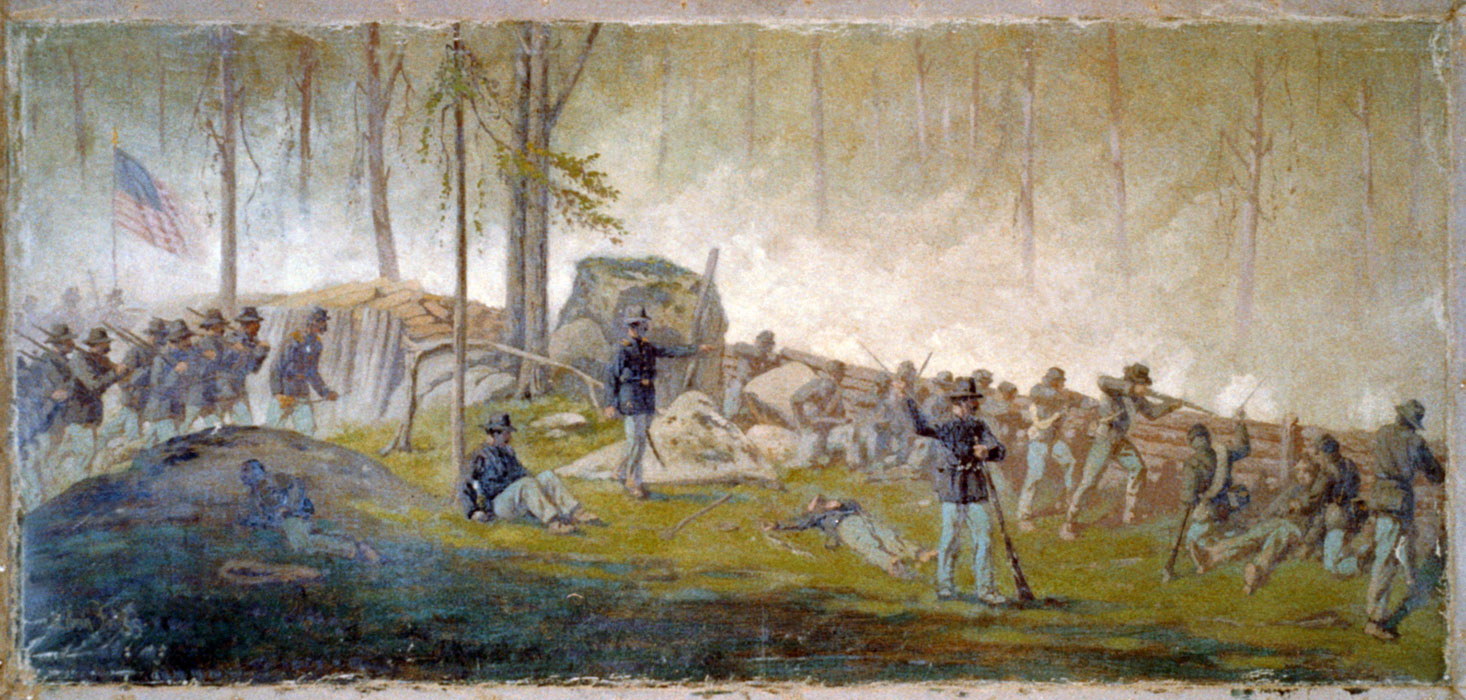

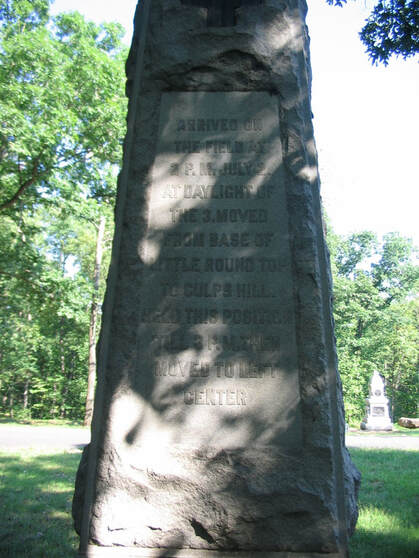

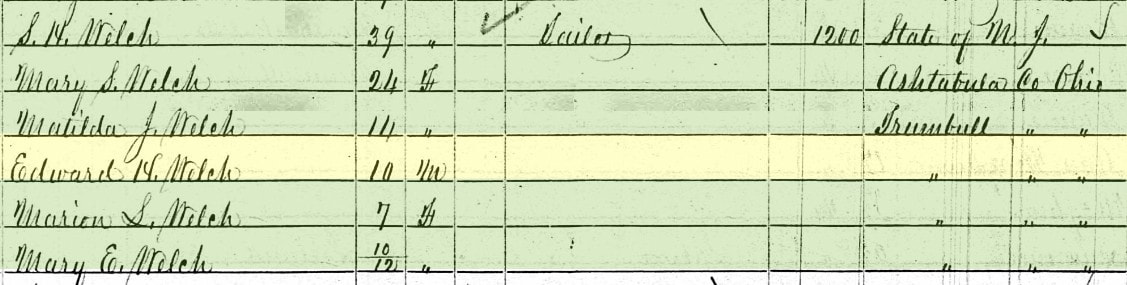

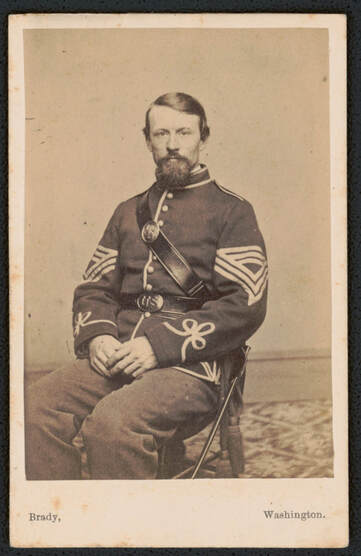

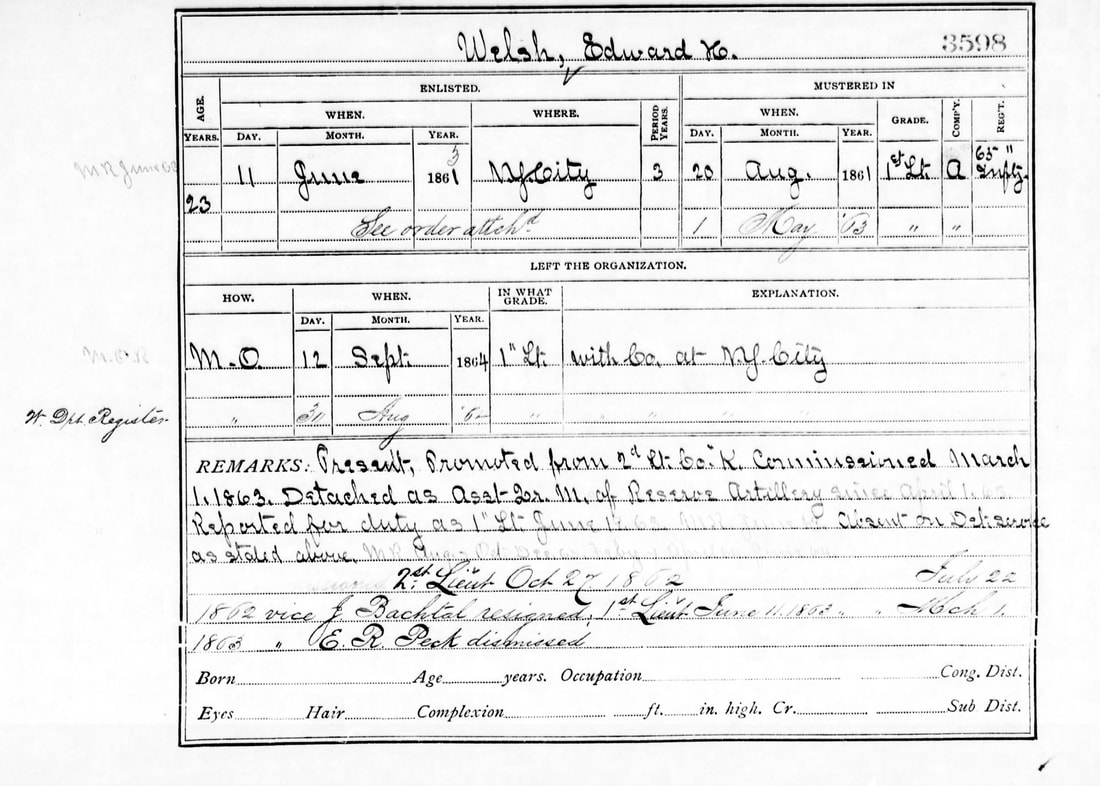

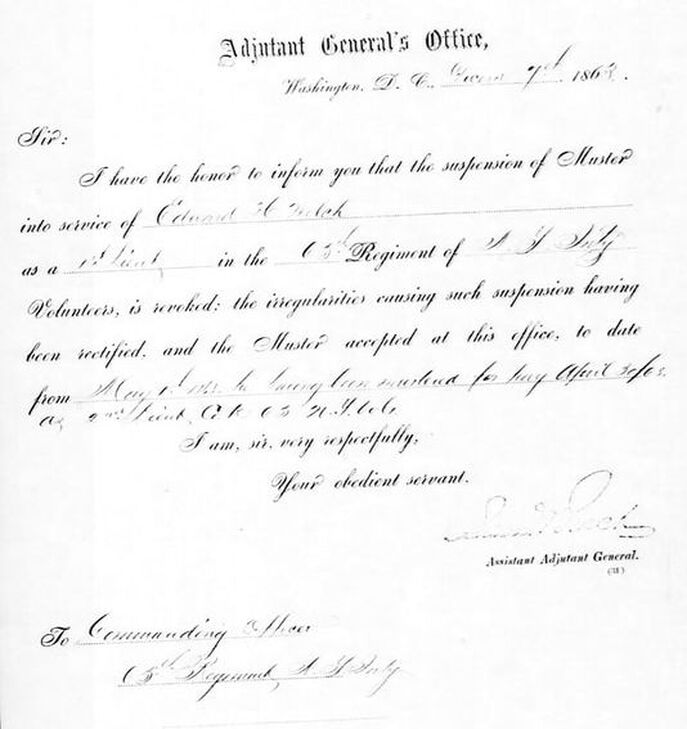

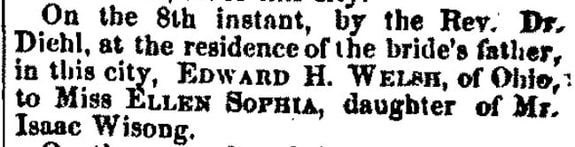

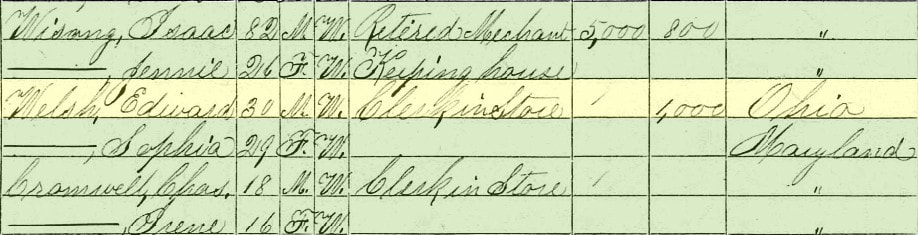

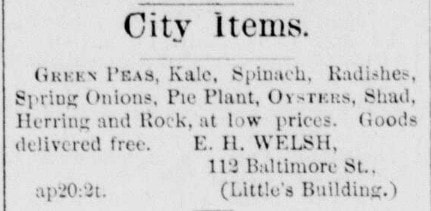

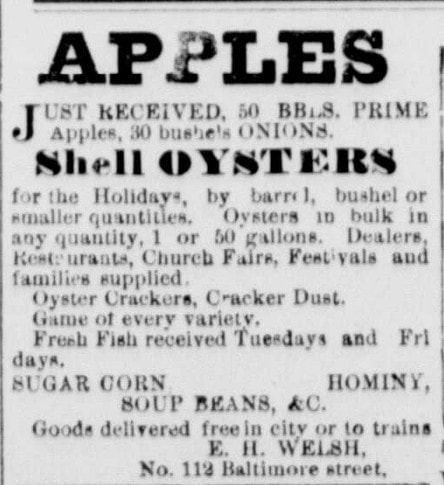

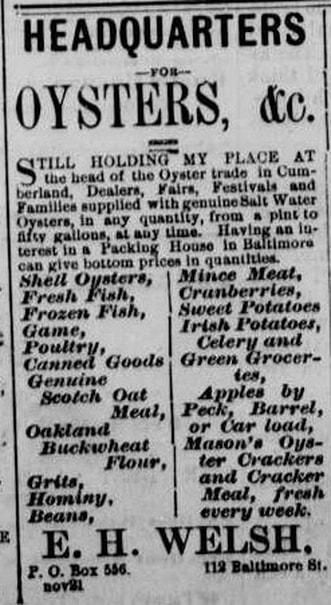

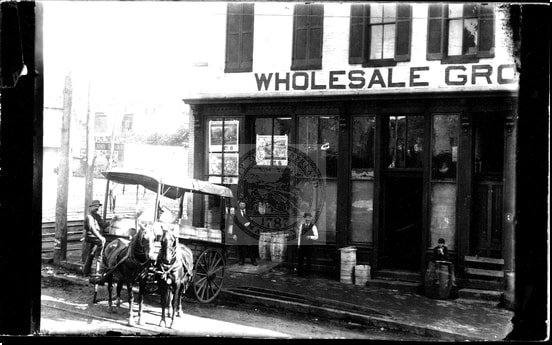

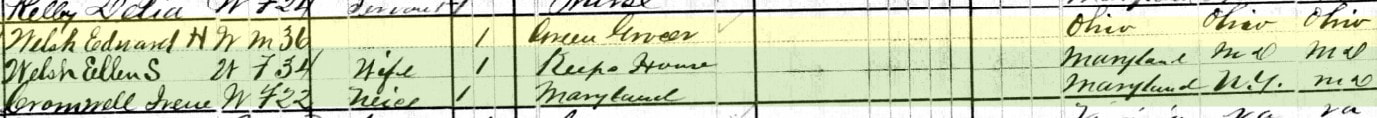

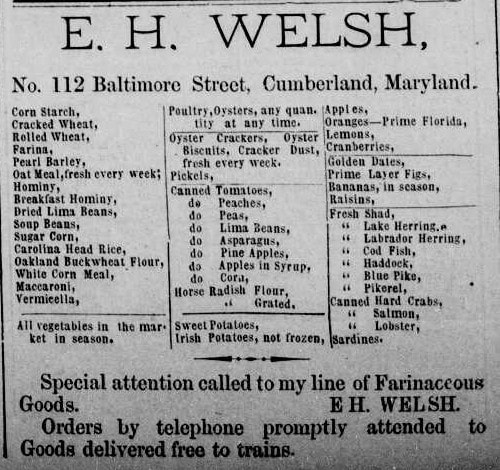

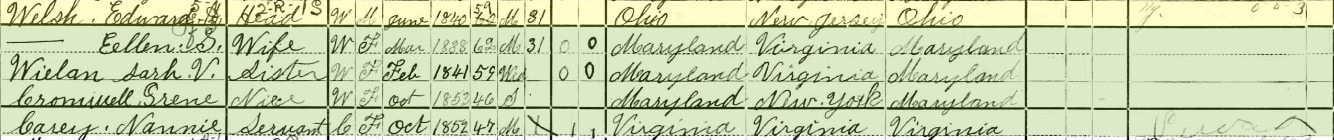

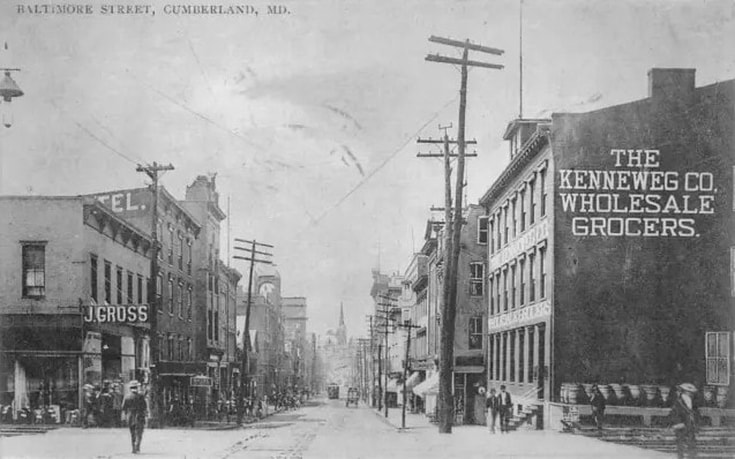

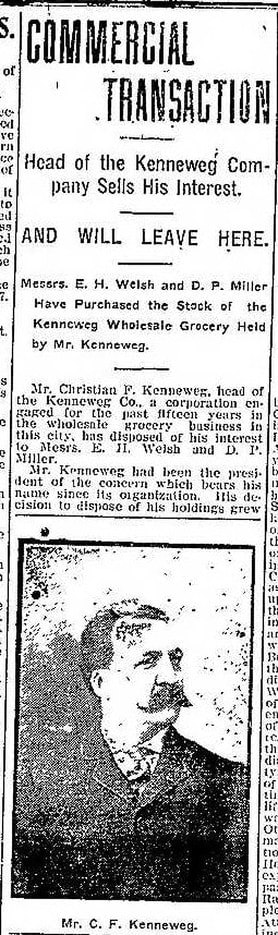

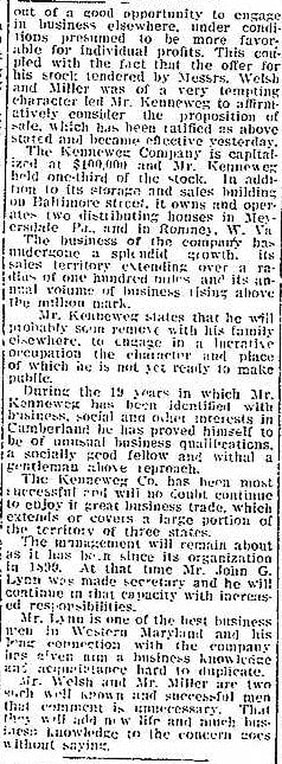

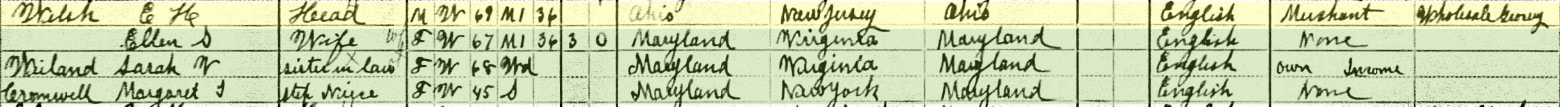

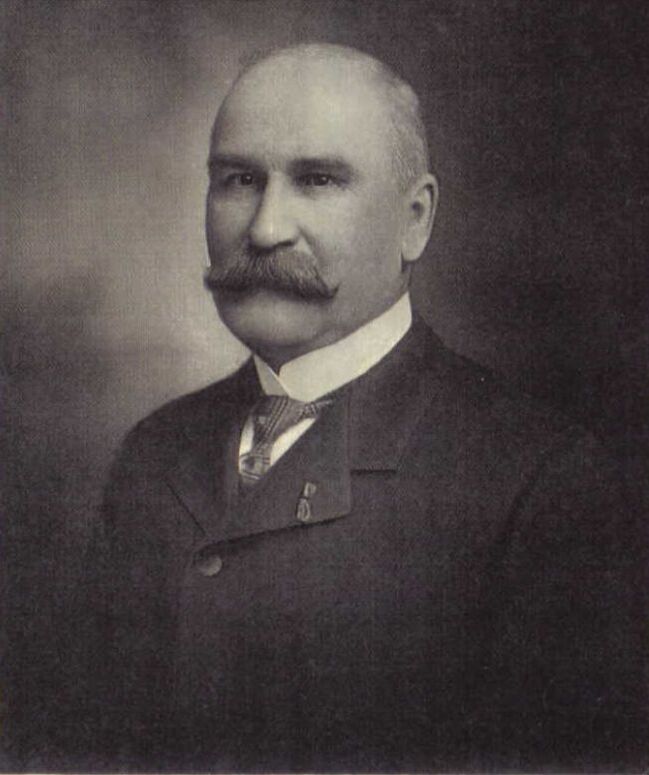

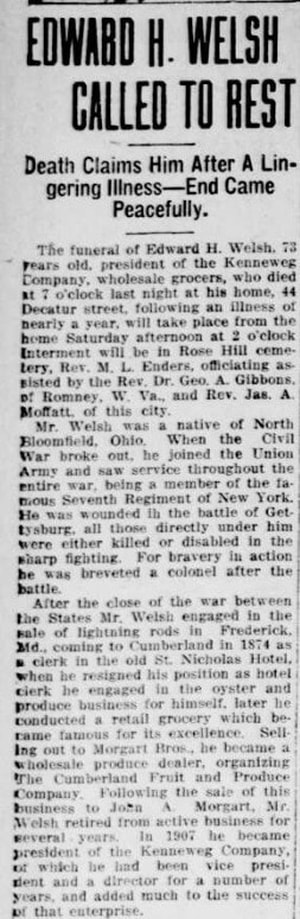

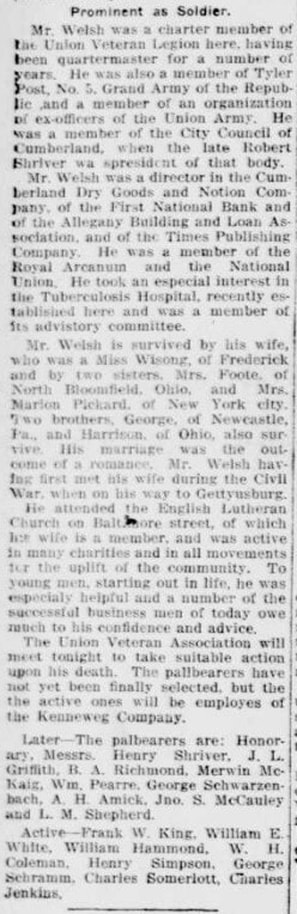

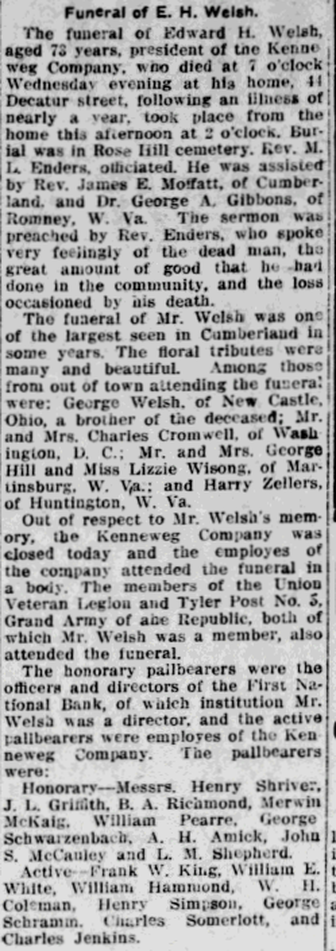

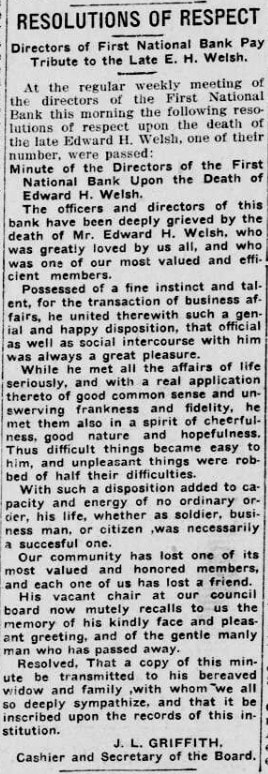

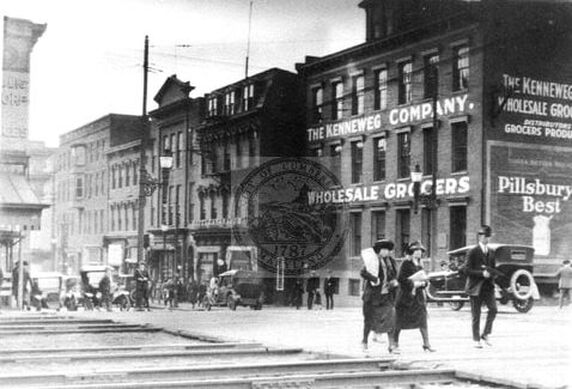

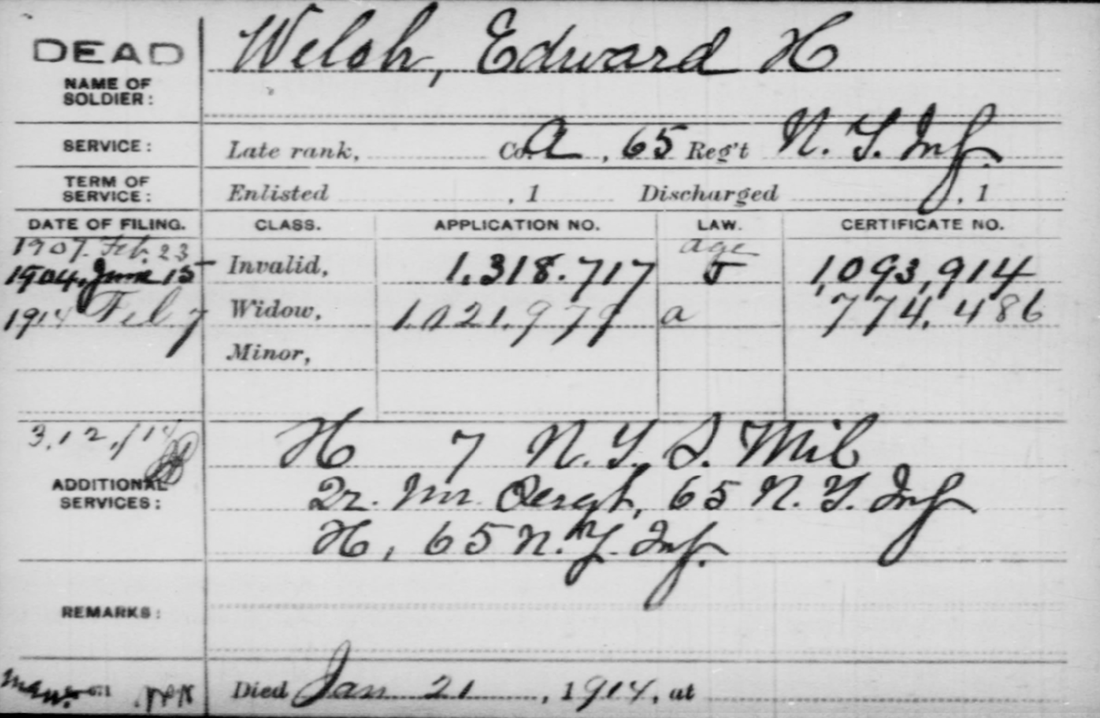

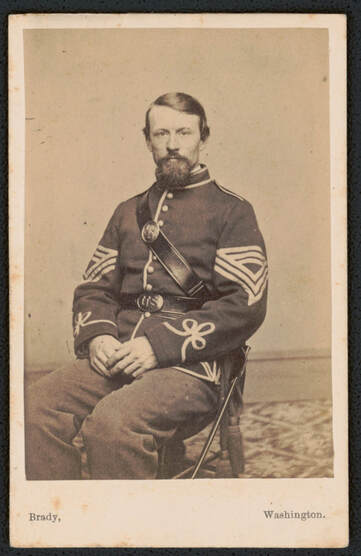

With the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg upon us, I thought it would be fitting to highlight a participant of that legendary conflict for this week’s story subject. His name is Col. Edward H. Welsh, and his gravestone in Frederick’s historic Mount Olivet spells out the fact that he was brevetted for gallantry shown in battle at Gettysburg in early July, 1863. And in case you are not familiar with the word “brevet,“ here is the definition: In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. An officer so promoted was referred to as being brevetted. Those of you who read last week’s “Story in Stone” know that the Union Army of the Potomac spent a few days in Frederick in late June, 1863. With Gen. Joseph J. Hooker in command, the Army was in pursuit of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee who had crossed the Potomac into Maryland a few weeks earlier with Rebel forces. Lee’s objectives were unknown to the Union forces and the leadership in Washington as this marked his furthest foray into northern territory. Cities such as Washington, Baltimore, Harrisburg and Philadelphia found themselves on high alert. Meanwhile back in Frederick, a messenger had been sent to town with an order from President Lincoln to relieve Gen. Hooker of his duties, and put Gen. George G. Meade in his place atop the Army of the Potomac. Meade and his men of the 5th Corps were encamped at Arcadia, a fine manor house on the Buckeystown Pike, located just north of the small hamlet of Lime Kiln. The actual change of command would occur at Gen. Hooker’s temporary quarters in the early morning hours of June 28th, at Prospect Hall a few miles to the northwest. With little time to plan strategy, Gen. Meade gathered his army which had been encamped in and around Frederick City, and marched them northwards toward the Mason-Dixon Line and Pennsylvania where intelligence reported Gen. Lee and his men to be. Every major roadway leading north from Frederick was utilized by the expansive Union force. Meade would make his next headquarters at Middleburg (Carroll County) on the 29th, and then northeast of Taneytown on the Shunk Farm where he directed the early concentration of his forces between June 30th and July 1st. Ironically, Meade had come from the south northward to meet his rival (coming from the north). His initial plan was one of a defensive nature requiring the spreading out of his troops across a series of entrenchments in northwestern Carroll County utilizing Pipe Creek as a line of demarcation. This has an interesting connection to Mount Olivet, and our most famous resident in Francis Scott Key who grew up along Pipe Creek near Keymar (MD). Key’s birthplace was the family plantation of Terra Rubra. What if the battle had been fought here and not Gettysburg? Could it have spilled over into northeastern Frederick County such as Thurmont (known then as Mechanicstown) or Graceham or Emmitsburg? What if? Instead, the greatest battle of the American Civil War would be fought July 1st–3rd, 1863, in and around the small town of Gettysburg just over the Pennsylvania border. In the conflict, Gen. Meade's Army defeated attacks by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, halting Lee's invasion of the North. The battle involved the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is often described as the war's turning point due to the Union's decisive victory and concurrence with its victorious Siege of Vicksburg. There are soldiers here in Mount Olivet that found themselves in Gettysburg on the field of battle in early July, 1863. One of them was a gentleman named Edward H. Welsh. His gravesite is marked by a substantial chunk of granite located adjacent the Key Memorial Chapel in Area H/Lot 5. The gravestone employs a mixed exterior of both polished surface along with rough-hewn sides and base. The lower face of his gravestone has raised, polished lettering and a simple cross. The cross, however, has nothing to do with traditional religion per se, but has a special military meaning as I would soon find out. The simple cross on Col. Welsh’s gravestone can be found throughout Gettysburg National Battlefield Park and signifies the Union Army of the Potomac’s 6th Corps. The 6th Corps had 37 infantry regiments and 8 artillery batteries at the Battle of Gettysburg, organized into 3 divisions of two or three brigades each and an artillery brigade. The military cross that appears on Col. Welsh’s gravestone in Mount Olivet, also appears on a very special monument on the battlefield on Culp’s Hill. As an aside, please check out a website called CivilWarCycling.com in which author Sue Thibodeaux has written an article (geared towards bicycle-bearing tourists) about the monument shapes and symbols at Gettysburg. It is a key to unlocking the symbols on regimental monuments that honor the Army of the Potomac. Sue has written books about other Civil War battlefield sites as well. The 65th New York Monument on Slocum Avenue honors Maj. Gen. John Sedwick’s 6th Corps. (Gen. Henry Slocum, of whom the avenue is named, was in command of the army’s right wing, which included Sedwick’s Corps.) The geographical location of the battlefield here is Culp’s Hill, as mentioned earlier. Particularly interesting for us locally, the action that involved the 6th Corps here occurred on the Union Army’s right on Day 2 and Day 3 of the battle (July 2nd and 3rd), and featured Marylanders of the Union Army pitted against Marylanders of the Confederate Army. On the second day of battle, most of both armies had assembled. The Union line was laid out in a defensive formation resembling a fishhook. In the late afternoon of July 2nd, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flank, and fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil's Den, and the Peach Orchard. On the Union right, Confederate demonstrations escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. All across the battlefield, despite significant losses, the Union defenders held their lines. In addition to Edward H. Welsh, two prominent Frederick men were on opposing sides at Culp’s Hill—Bradley Tyler Johnson and Joseph Groff. Brigadier Gen. Bradley Tyler Johnson was a former attorney from Frederick who left town after gathering men to fight for the Confederacy. He would be among the most prominent Marylanders who fought for the South, and led the 1st Maryland Regiment, C.S.A. (Confederate States of America). He is descended from the Tyler and Johnson families of town with roots going back to Baker Johnson, brother of Gov. Thomas Johnson. Bradley Tyler Johnson was born in 1829, the son of Charles Worthington Johnson and Eleanor Murdock Tyler and graduated from Princeton in 1849. He read law with William Ross of Frederick, and finished his legal degree at Harvard. He was admitted to the bar in 1851. Johnson is not buried here, but rather in Loudon Park Cemetery in Baltimore. About 100 yards directly behind (and west) of Edward H. Welsh’s grave is that of Capt. Joseph Groff of the Union’s Potomac Home Brigade. This outfit was made up of local men from our area. I wrote a “Story in Stone” on Captain Groff and you can read more on him at your leisure. On the third day of battle, fighting resumed on Culp's Hill, and cavalry battles raged to the east and south, but the main event was a dramatic infantry assault by around 12,000 Confederates against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, known as Pickett's Charge. The charge was repelled by Union rifle and artillery fire, at great loss to the Confederate army. Lee led his army on a torturous retreat back to Virginia. Between 46,000 and 51,000 soldiers from both armies were casualties in the three-day battle, the most costly in US history. Both Capt. Groff and Lt. Welsh would be wounded at Culp’s Hill, not far from Spangler’s Spring. The landmark is down below the hill from the 65th New York Infantry Monument marking the ground Welsh, and his fellow soldiers, stood upon 160 years ago. One side panel of the monument reads: “Arrived on the field at 2 P.M. on July 2. At daylight of the 3rd, moved from the base of Little Round Top to Culp’s Hill. Held this position til 3 P.M. then moved to the left center.” The 65th’s brigade commander, Col. Alexander Shaler, was relatively new in his position. His recent promotion came following heroics at the Battle of Salem Heights (VA) in which he, himself, displayed gallantry under fire leading him to earn the Medal of Honor, the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration. Lt. Colonel Joseph E. Hamblin was promoted to colonel as a result, and took direct command of the regiment. At Gettysburg, he had brought 319 men to the field, including Lt. Welsh. Hamblin lost 4 men killed and 5 wounded during the three-day engagement between July 1st-3rd, 1863. One of those wounded was our subject Edward H. Welsh. Edward Horace Welsh was born on June 2nd, 1840 in North Bloomfield, Trumbull County, Ohio. His parents were Samuel H. Welsh (1811-1900) and Matilda (Flower) Welsh (1815-1846). A biography of Col. Welsh can be found in the History of Allegany County, Maryland by James Thomas and Thomas J. C. Williams (published 1923). It reads: “He was reared and educated in his native state. When still a lad, moved to Cleveland, Ohio, and later became a member of the Cleveland Grays, a company organized in that city. When war broke out between the States, he enlisted as a member of the Seventh New York Militia, and served with it until it was mustered out ninety days later, and he then enlisted, with the First Regiment of United States Chasseurs, also called the Sixty-fifth New York Volunteer Infantry, and July 11, 1861, was appointed quartermaster-sergeant of this regiment because of his patriotism and valor. At the time of this later enlistment he was only twenty years of age, and yet in spite of his youth served with distinction throughout the entire campaign. At the battle of Fair Oaks, or Seven Pines, as it is sometimes called, he was wounded in the breast, leg and ankle, and, as a reward for meritorious service, was made a second lieutenant. On October 28, 1863, Mr. Welsh was appointed first lieutenant of the Sixth Artillery, New York State Volunteers, and served with distinction during the three days battle of Gettysburg, and was very active in the placing of artillery at strategic points, and for this splendid service was brevetted colonel. A monument in honor of the service performed by his regiment now stands near the entrance to the Gettysburg National Cemetery. Subsequently he was assigned to the personal staff of General Hunt, of the Artillery of the Army of the Potomac, where he served with distinction until the close of the war. In spite of his severe wounds he never drew a pension, nor did he ever apply for one, "it being his pleasure that he served his country and was wounded in its service because of his patriotic love for it, and not for any material reward.” The History of Allegany County biography continues: “After his honorable discharge, Mr. Welsh went to Frederick City, Maryland. On November 8th, 1869, Mr. Welsh married Ellen Sophie (Wisong) (1838-1923) of Frederick City. She grew up in a house found on East Patrick Street.” Welsh supposedly came to Frederick and sold lightning rods. After marrying, the couple lived together with Ellen’s widowed father, Isaac Wisong, and sister Jennie. Also living here were Ellen’s 16-year-old niece Margaret Irene Cromwell and nephew 18-year-old Charles Cromwell. The men (Edward and Charles) are listed as working as store clerks, and I would bet they worked at the Excelsior Stove House of N. J. Wilson located on E. Patrick Street. which featured a lightning rod department; or in either of grocery stores, as two were located near their home in the 100 block of East Patrick Street. (The Wisongs lived at 117 E. Patrick according to records). These groceries were Holbrunner’s Grocery and Plummer’s Grocery at the time (1870). Welsh worked as a hotel clerk in Cumberland as early as 1873. Another excerpt from the biography found in the History of Allegany County by Williams and Thomas tells of Welsh's move from Frederick to western Maryland but mentions the job he would "leave the hotel" for: “In 1873, he came to Cumberland, and established himself in the wholesale and retail green grocery business on Baltimore Street, and later became associated with the Kenneweg Company, wholesale grocers, was its president for a number of years until his death January 21st, 1914. He was a director of the First National Bank, and the Cumberland Dry Goods & Notion Company, both of Cumberland, and never lost his deep interest in the welfare of the city, and the development of its enterprises. Mr. Welsh took an active part in the operation of the Allegany Building, Loan & Savings Company, and demonstrated his faith in the city and county by investing in their different enterprises. A strong Republican, he was honored by being the successful candidate of his party for the office of city councilman, and was returned to that office after serving one term.” Let’s break this published bio down a bit, shall we? In the 1890 Cumberland Directory, the Welshs lived on Baltimore Street, next door to their grocery business. Ads from 1889 say that the E. H. Welsh Grocery was located at 150 Baltimore Street. Perhaps a renumbering occurred, or a move to a different building occurred. Regardless, they would re-locate from this home at some point before the 1900 census was taken, as they can be found living in a house they owned on Decatur Street. Edward was active in the National Civil War Veterans fraternal organization known as the Grand Army of the Republic, or G.A.R. for short. In 1903, Edward H. Welsh was appointed as an Aide-de-Camp of the National Commander in Chief of the G.A.R., and in 1905 he could be found serving as Commander of the Tyler Post #5 in Cumberland. Welsh represented the Department of Maryland at the National Encampment of the G.A.R. in Denver, Colorado in September, 1905. He also represented the Cumberland G.A.R. Post at the annual Department Encampment in Baltimore in April, 1906. In business, our subject was re-elected as a director of the Inter-State Trust Company in 1907, and again in 1909. In 1907, Edward and a business associate bought the large Kenneweg Company Wholesale Grocery store, a chain store affiliate of the Pittsburgh firm of the same name. Mr. Christian Kenneweg had come to town in the late 1880s, and Col. Welsh seems to have kept his composure and competed for years without issue. Mr. Kenneweg likely saw something in Welsh to eventually sell the location/franchise to him.

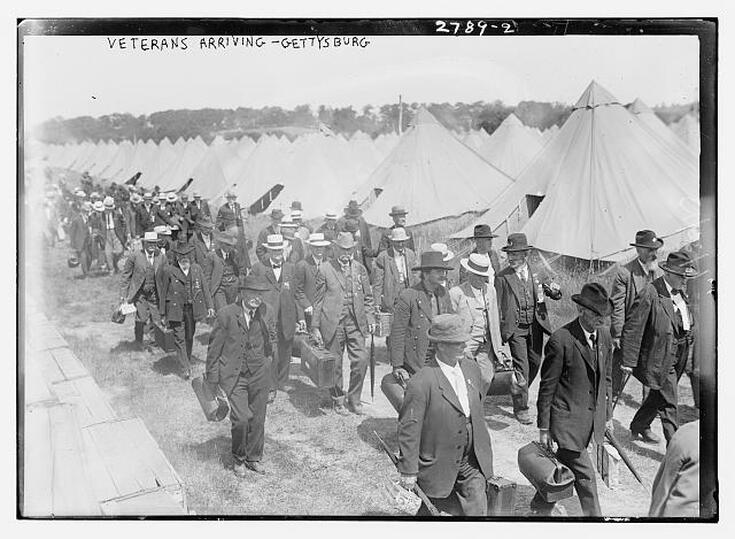

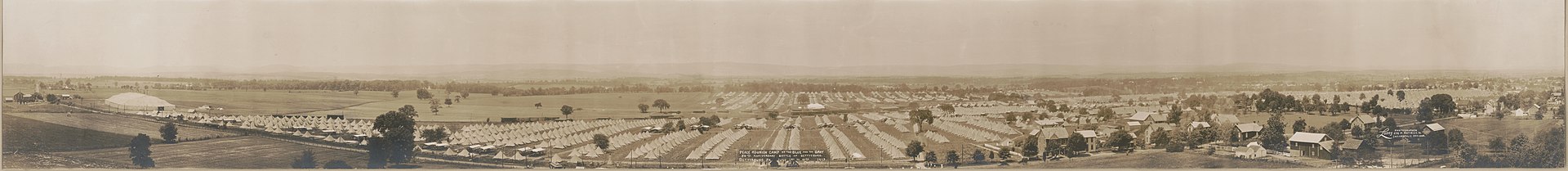

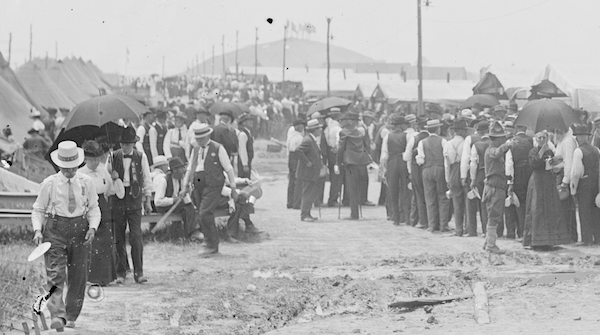

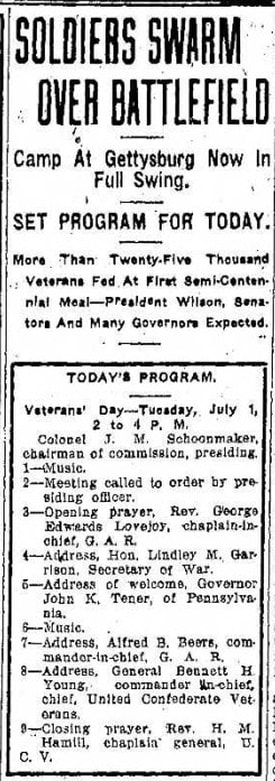

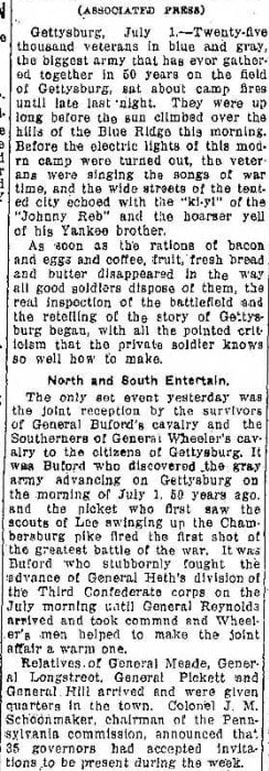

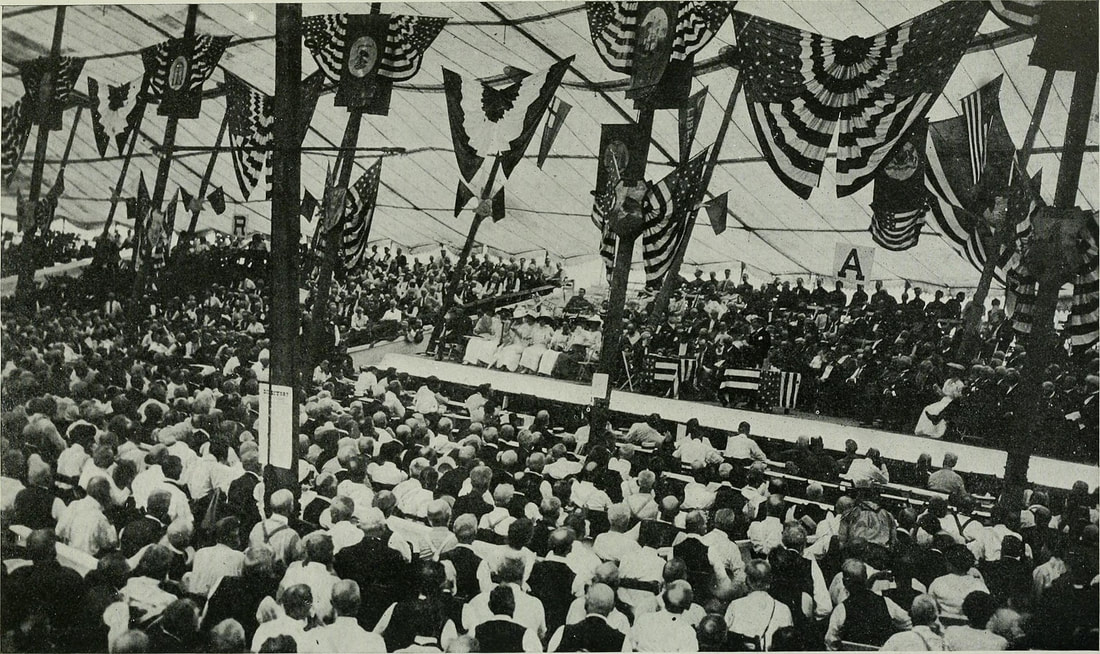

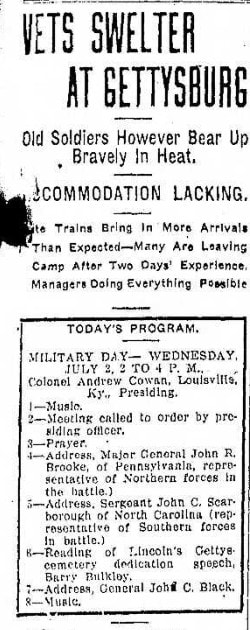

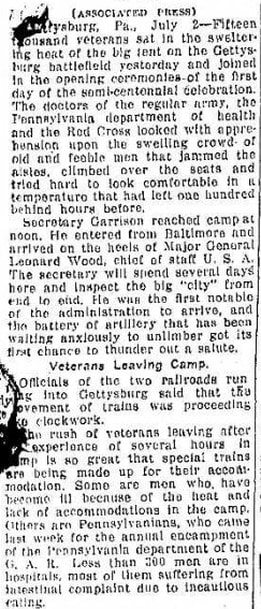

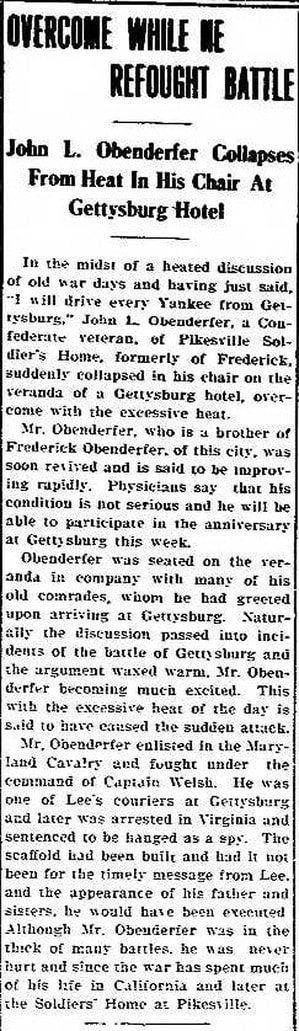

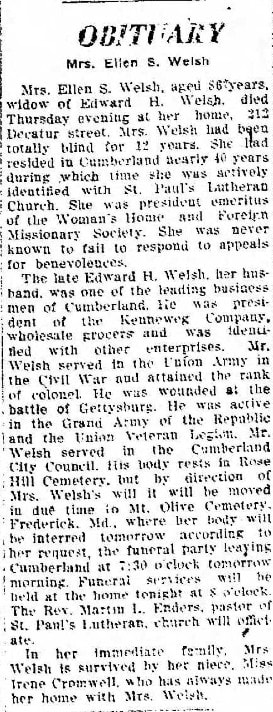

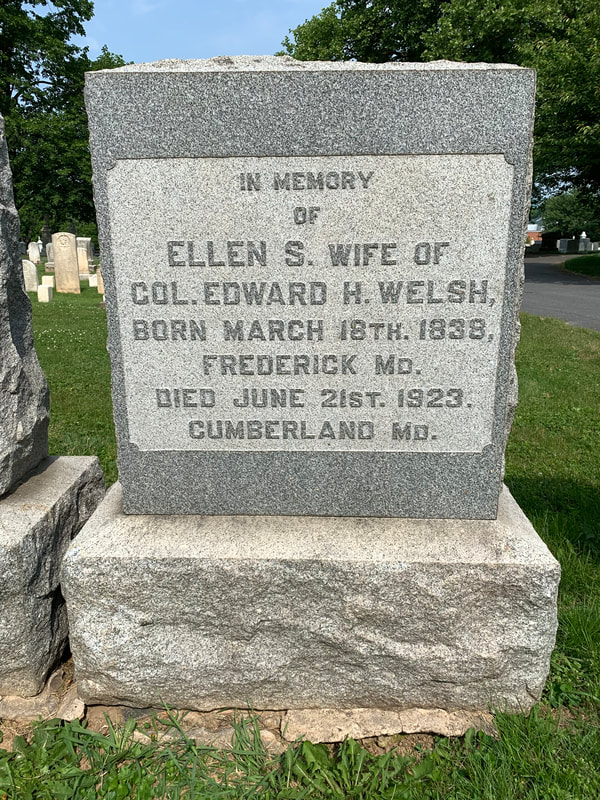

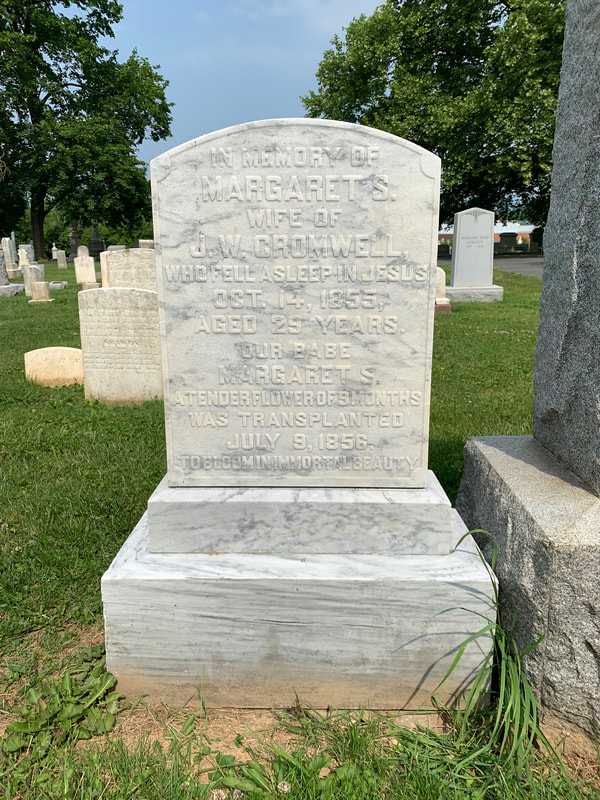

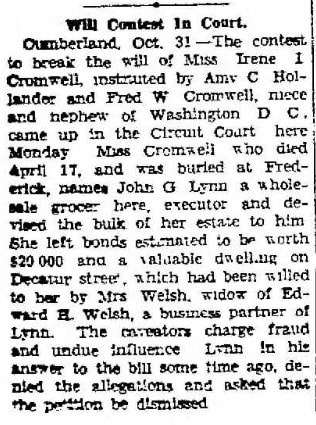

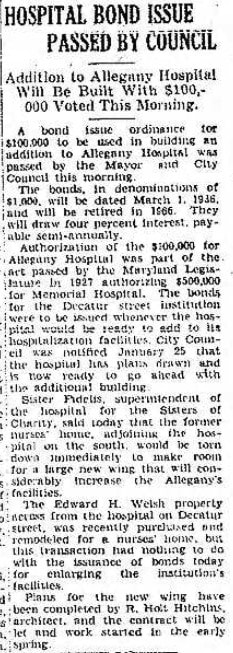

Col. Welsh was now 70 years of age by early July, 1910 and the 47th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. He continued his activities in business, civic and personal life. I searched the local papers for any mention of Col. Welsh’s participation in the activities marking the 50th anniversary of the most famous battle fought on American soil. This was a big deal as thousands of soldiers gathered in the central Pennsylvania town to participate in commemorative events marketed as "The Great Peace Reunion." It would be held in sweltering heat, and was attended by President Woodrow Wilson, former officers of the battle and other dignitaries. I would have to assume that Col. Welsh was there in Gettysburg with old friends and foes from 1863 for that amazing commemoration. Here was a man very proud of his military service, exemplified by participation at the highest leadership levels in the G.A.R. activities, and having a gravestone that makes special note of his participation in the Battle of Gettysburg. I’d bet money that Edward H. Welsh was there in Gettysburg from July 1st-4th, 1913. I thought I had something when a Frederick newspaper online search provided me with a Welsh result pertaining to the Gettysburg commemoration of 1913. However, I soon deducted that this gentleman was not our Edward H. Welsh. The article centered on another former resident named John L. Obenderfer who once reported to a “Capt. Welsh” in the Confederate ranks. It is a comically written story so I decided to share with you nonetheless. Getting back to our Col. Welsh of Frederick and Cumberland, I am happy to think that he had this amazing experience in Gettysburg of attending the 50th anniversary commemoration. This is even more poignant because five months later, Edward H. Welsh would be gone. He died on January 21st, 1914 in Cumberland. The History of Allegany County states: “For about a year prior to his demise Mr. Welsh was in poor health, but his death came as a shock to his many friends in the city and county. His funeral was largely attended by the leading citizens of this region, who flocked to honor one who in life had rendered so public-spirited a service, and set so high an example of honorable living. Interestingly, interment was not made here in Mount Olivet. Instead, Col. Welsh was interred in Cumberland’s Rose Hill Cemetery.” Ellen S. Welsh continued living in the couple’s home in Cumberland. She also would receive her late husband's pension. Her live-in companion remained niece Margaret Irene Cromwell. She died in 1923 at the age of 85 in Cumberland, however her body was brought to her native home for burial. She would be laid to rest in her family plot in Area H/Lot 5 just outside Key Memorial Chapel, newly constructed less than a decade before. Mrs. Welsh left quite an estate behind, a testimonial to her late husband’s business acumen. It was worth an estimated $200,000 according to her will. Without any direct heirs, the majority of the estate would go to niece Margaret Irene Cromwell. Mrs. Welsh’s last wishes directed that the body of her late husband Edward be exhumed and re-interred next to her in Mount Olivet at the time of her death. This would be completed six months after Ellen’s funeral . Edward’s body arrived at the cemetery on November 23rd, 1923. An additional bequest included $200 to be paid to Mount Olivet for the upkeep of the family plot. Margaret Cromwell had started her life in Frederick, but would stay in Cumberland living in the home on Decatur Street until her death in 1933. Margaret's executors would sell the former Welsh family home to Allegany Hospital of the Sisters of Charity in 1935. Ms. Cromwell's body would be brought back to Frederick like the Welshs. She would be buried next to Col. Welsh and Ellen, her adopted parents for the bulk of her life one could say. A final person of note in this plot was Margaret’s mother of the same name. She was Ellen Welsh’s sister who died at age 29 in October 1855. This was less than two weeks before daughter Margaret’s second birthday. So on this 160th observance of the Battle of Gettysburg, let us not forget that "freedom is not free." The idiom expresses gratitude for the service of members of the military, implicitly stating that the freedoms enjoyed by many citizens in many democracies are possible only through the risks taken and sacrifices made by those in the military, drafted or not. The saying pertains to Col. Welsh and thousands of others in Mount Olivet who participated in conflicts that allow us to attend baseball games, eat hotdogs and drink beer at family picnics, go to the beach, and watch fireworks this holiday weekend if we so please. So be sure to give the colonel's "illustrative" gravestone a nod of respect if you happen to be in the cemetery anytime soon. AUTHOR'S NOTE: Special thanks to Karl "Woody" Woodcock and Gary L. Dyson for the advance research work both gentleman have done on our Civil War soldiers at Mount Olivet. Some of that research was utilized in pulling together this story. History Shark Productions presents:

Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101" Are you interested in Frederick history? Want to learn more from this award-winning author and documentarian? Check out his latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101," with a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings in late August/early September, 2023 (Aug. 22, 29 & Sept 5, 12). These will take place from 6-8:30pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes 4 classes). In addition to the lecture class above, four unique "Frederick History 101 Walking Tour-Classes" in Mount Olivet Cemetery will be led by Chris this summer. These are available for different dates (July 11, July 25th, Aug. 8th and Aug 23rd) Cost $20. For more info and course registration, click the button below! (More courses to come)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed