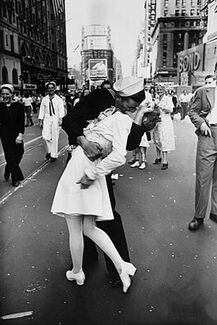

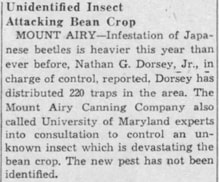

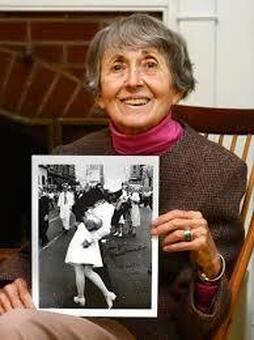

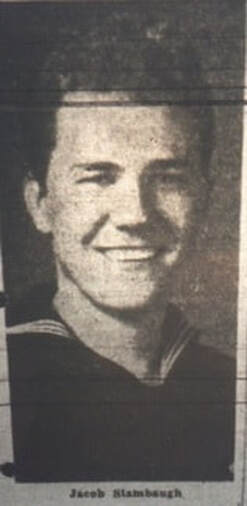

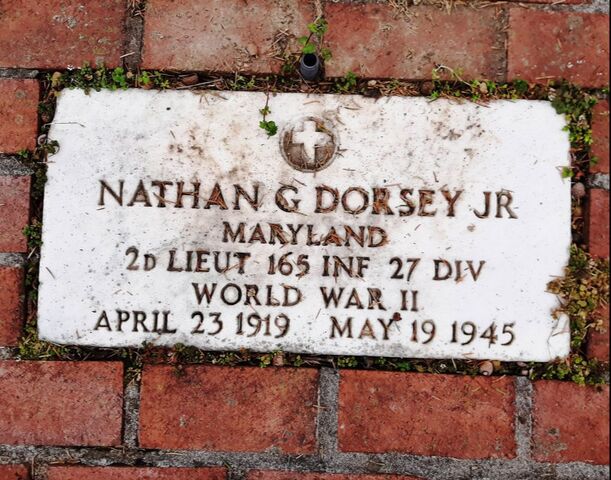

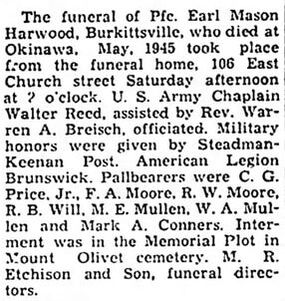

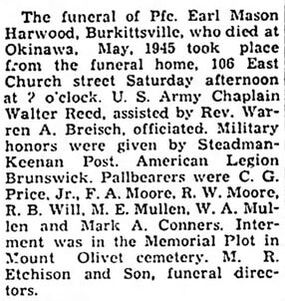

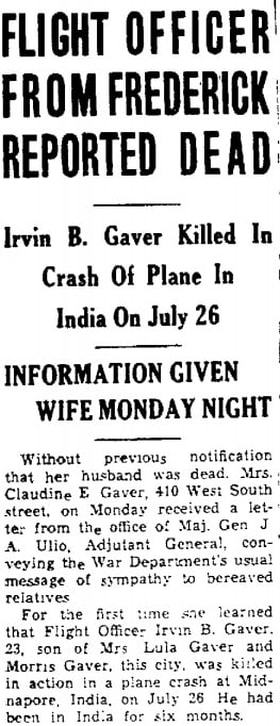

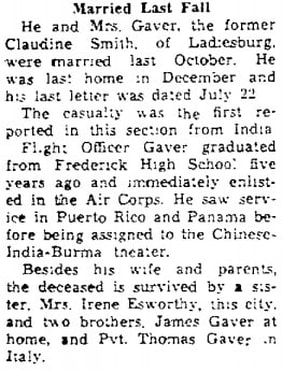

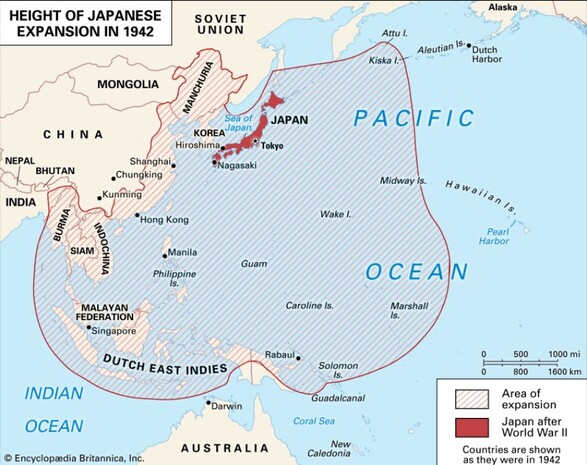

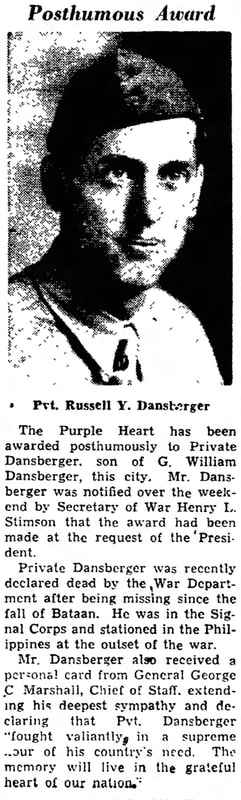

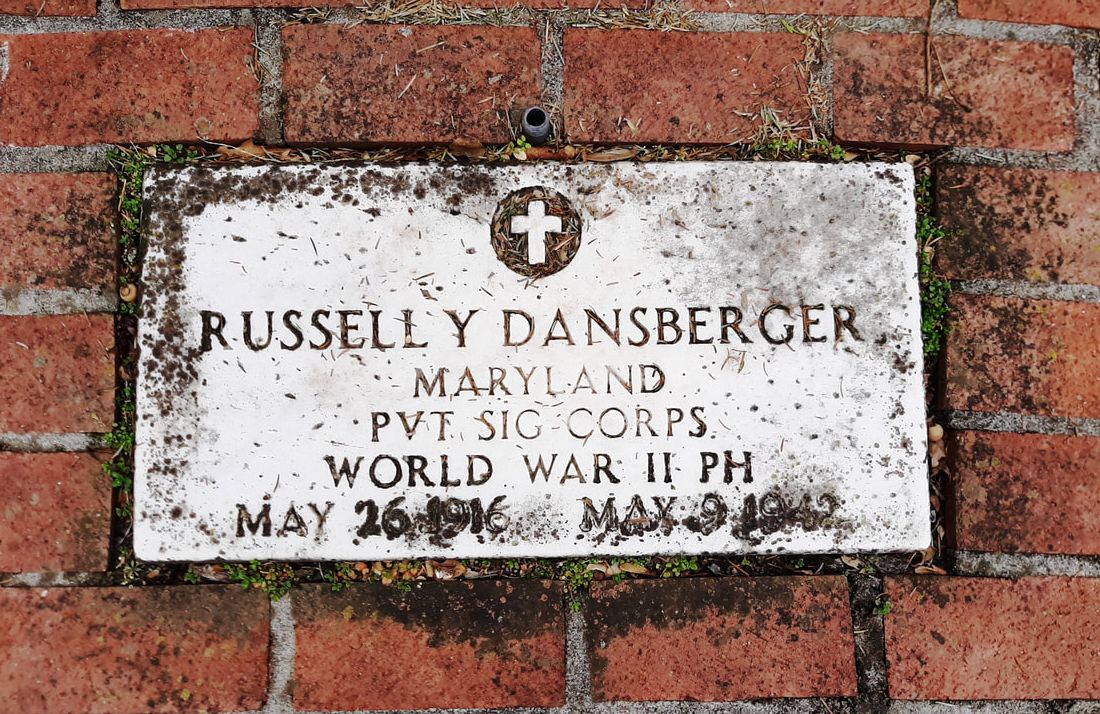

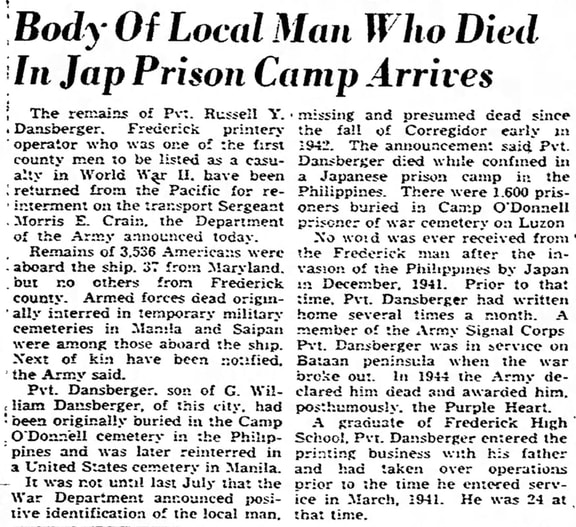

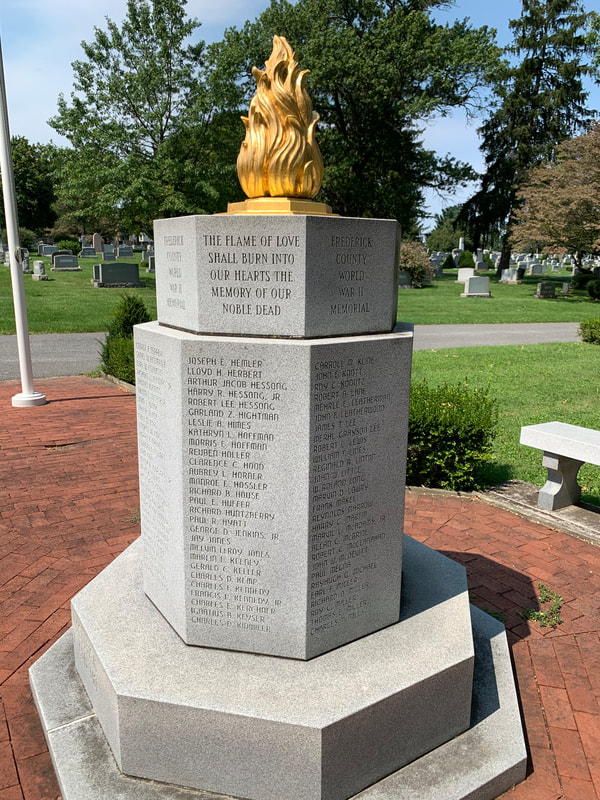

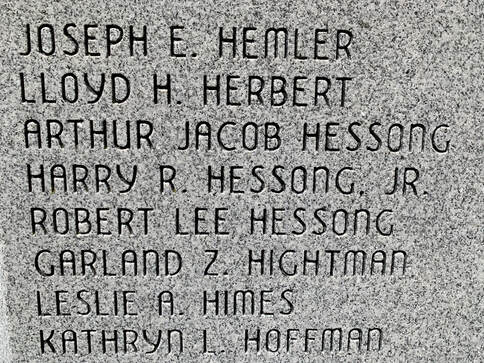

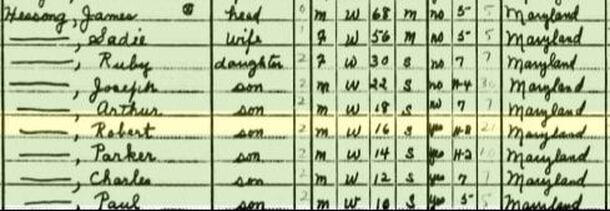

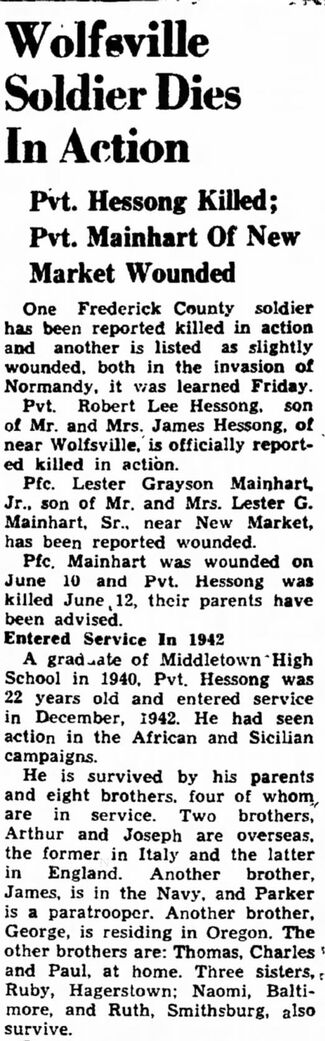

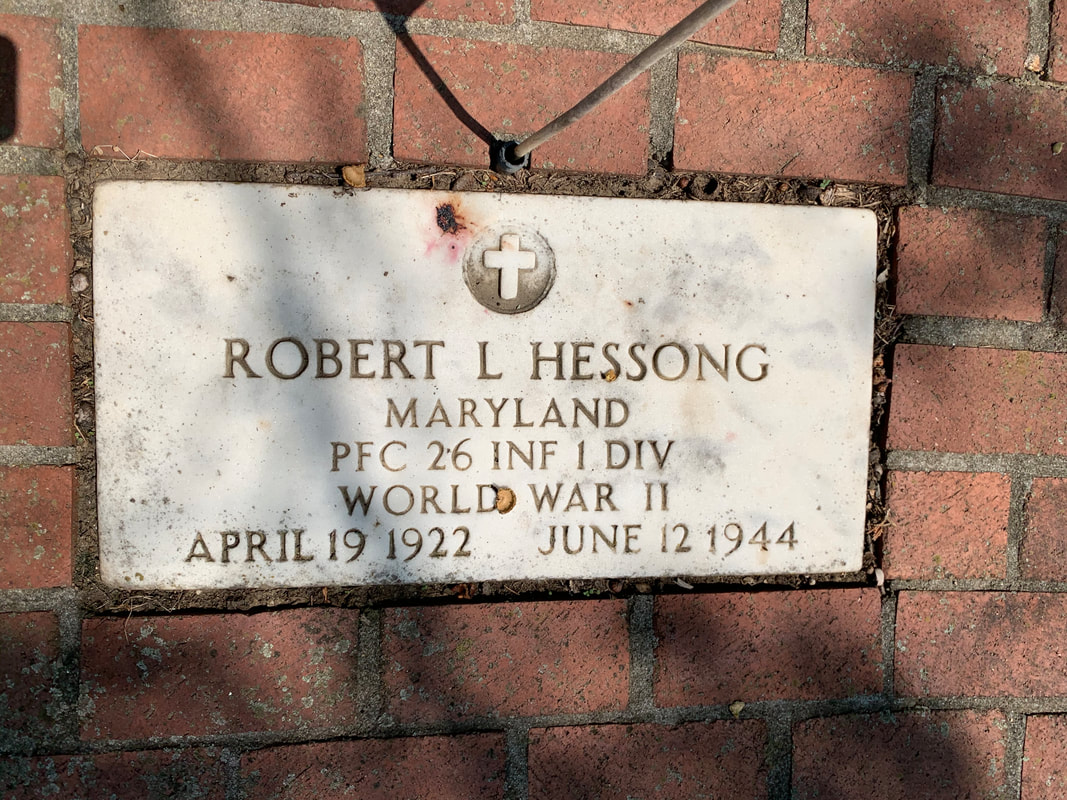

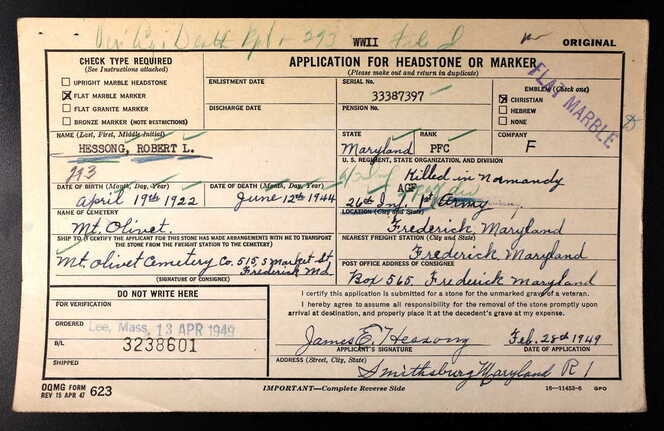

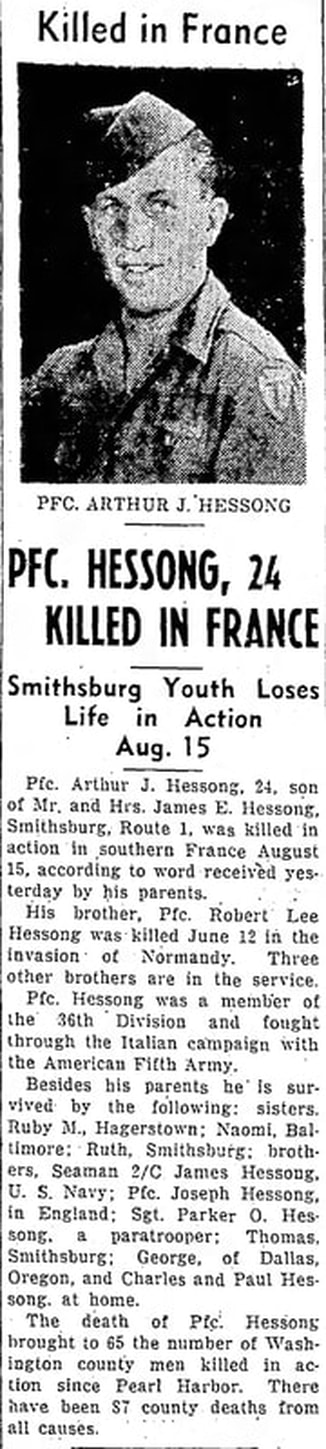

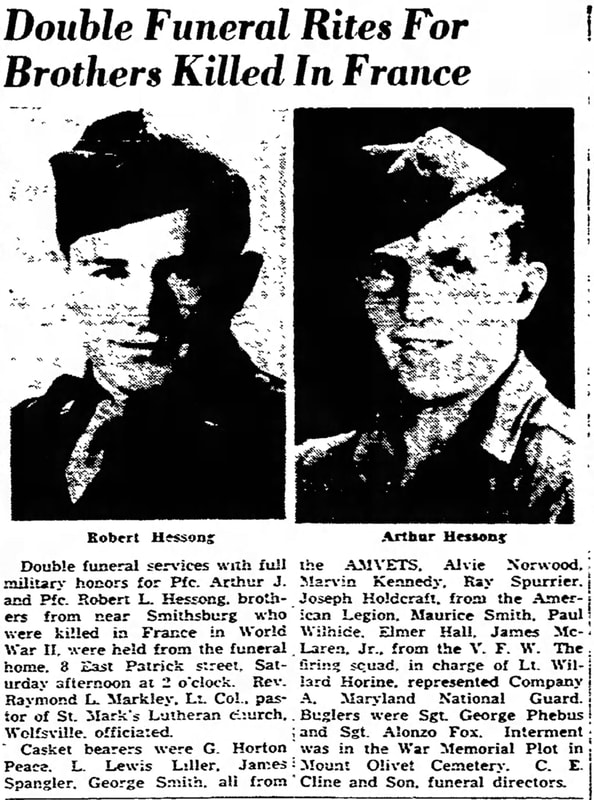

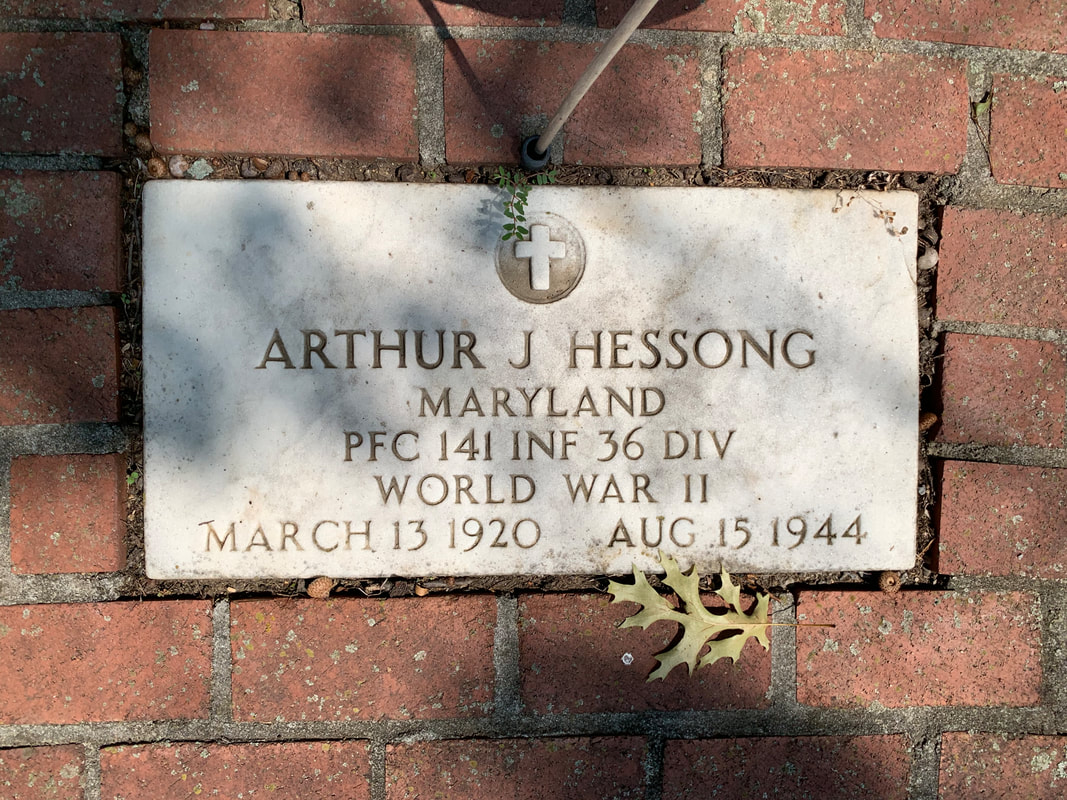

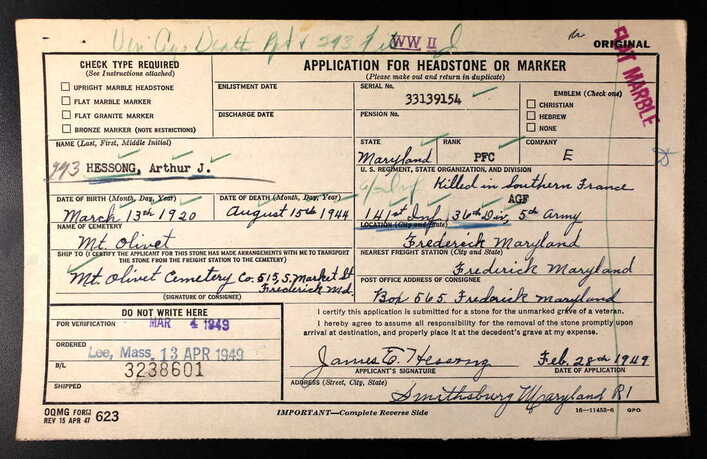

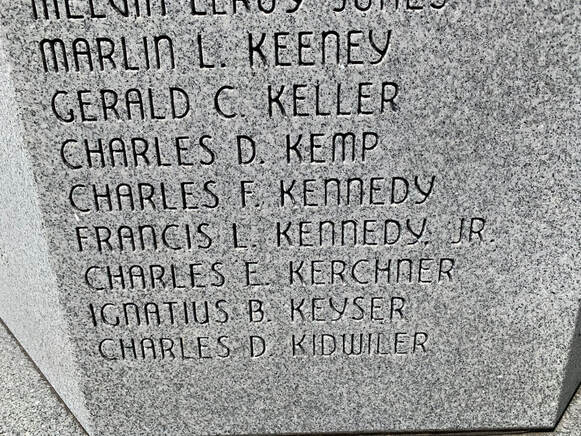

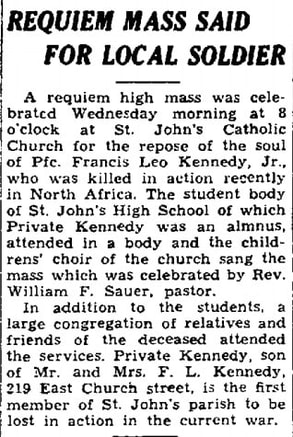

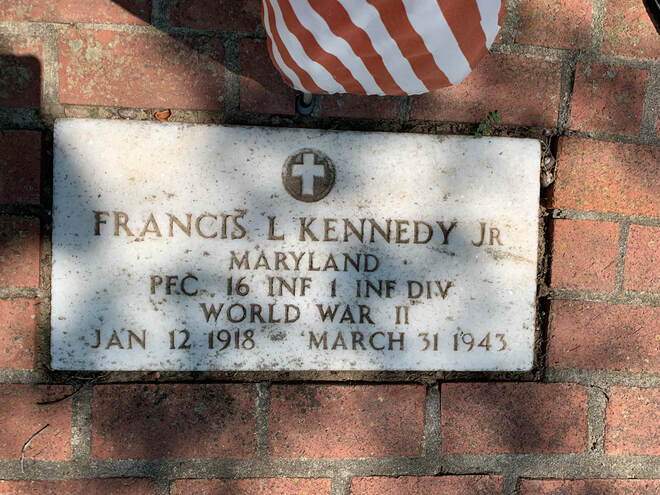

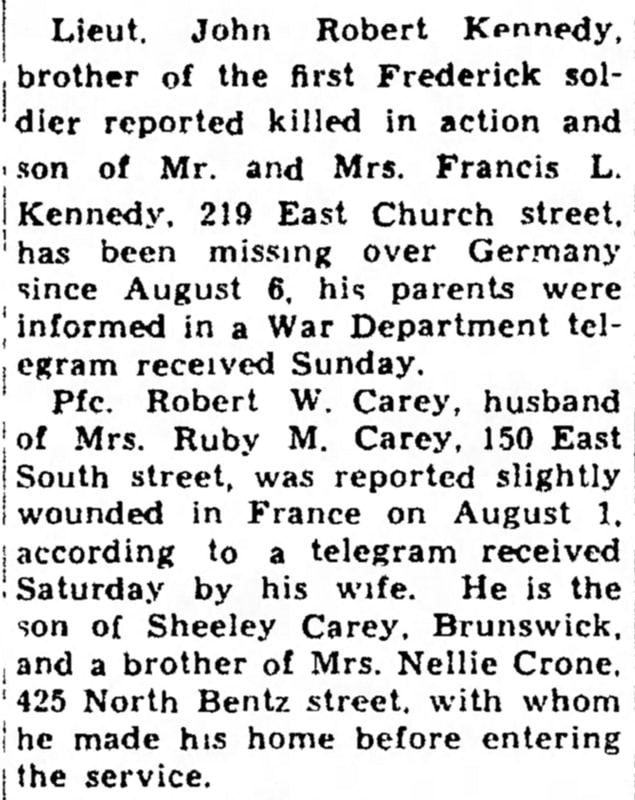

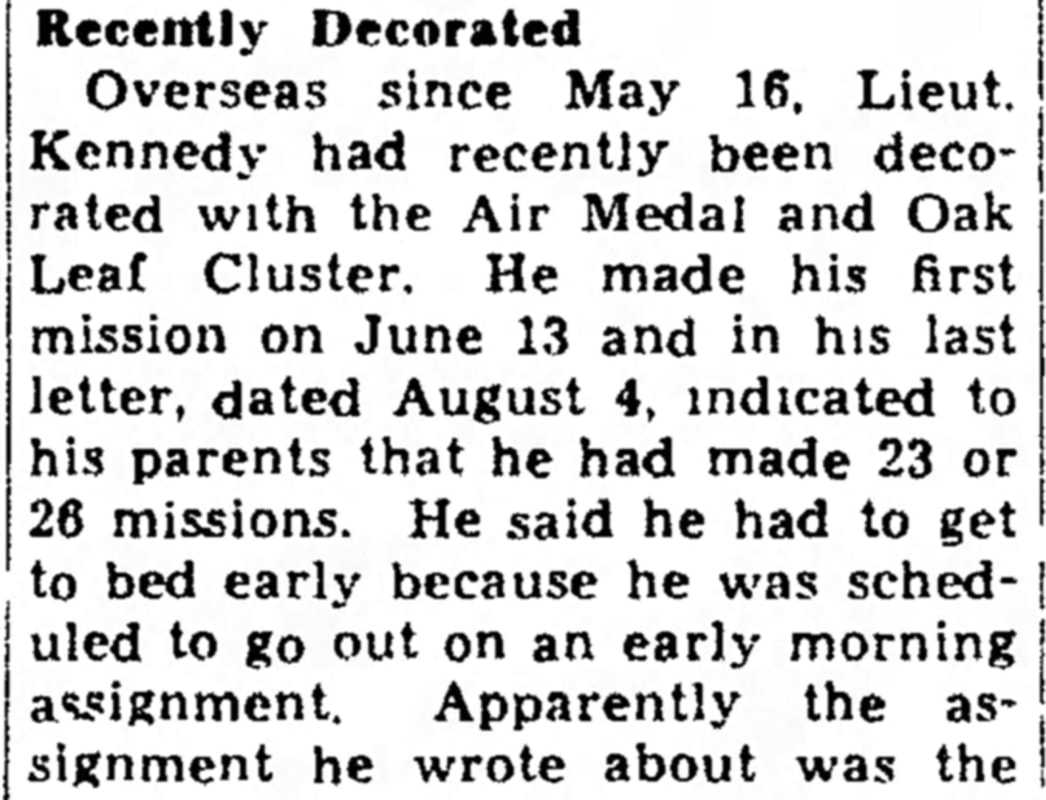

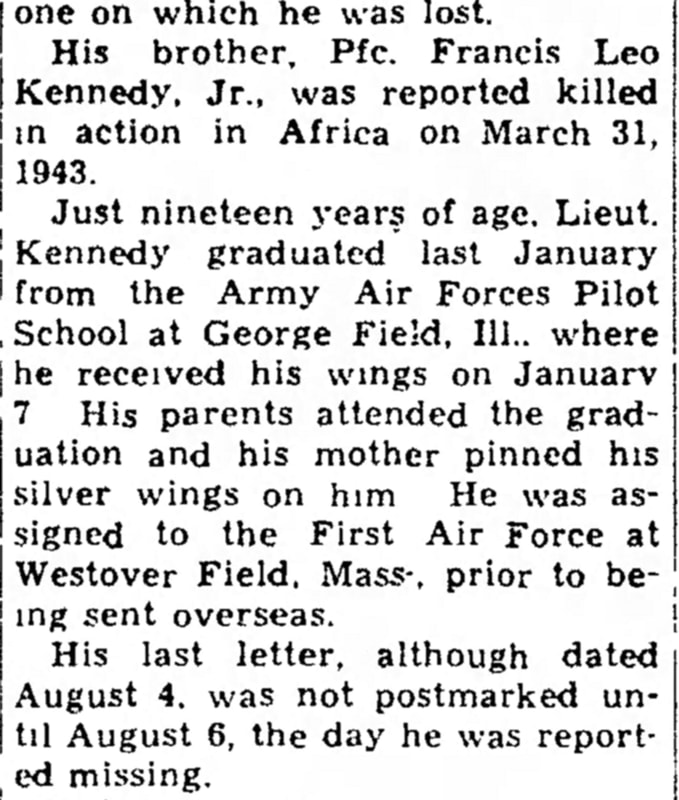

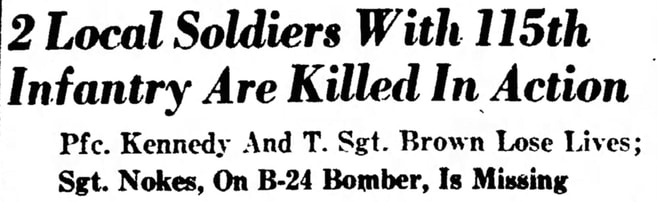

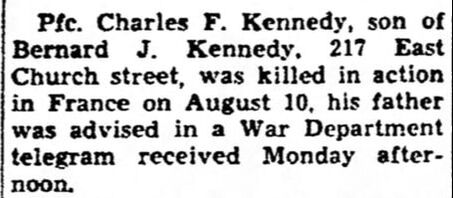

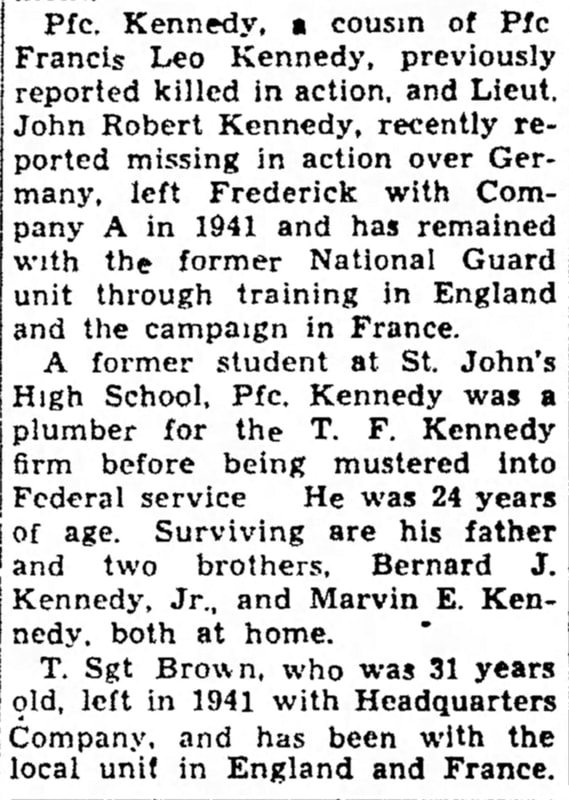

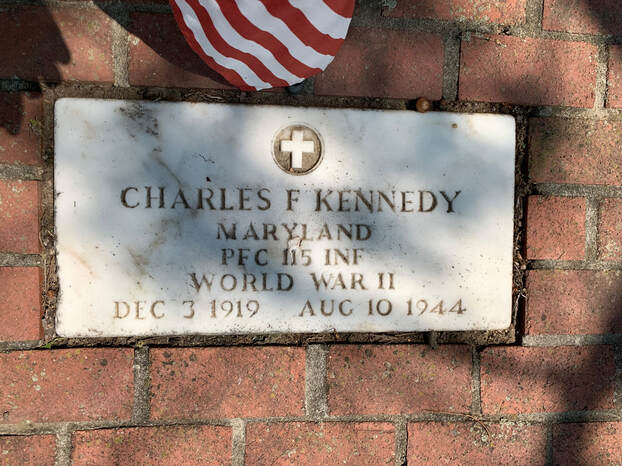

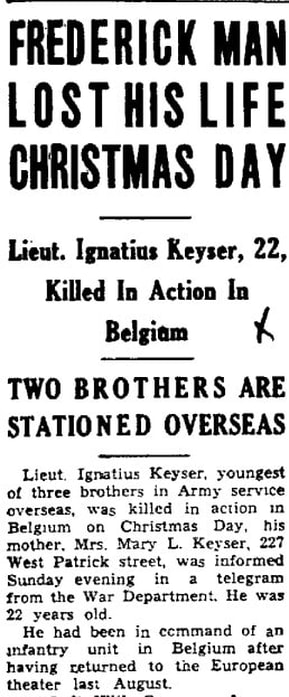

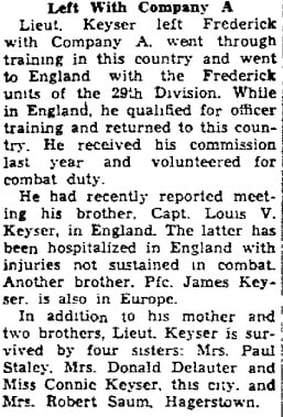

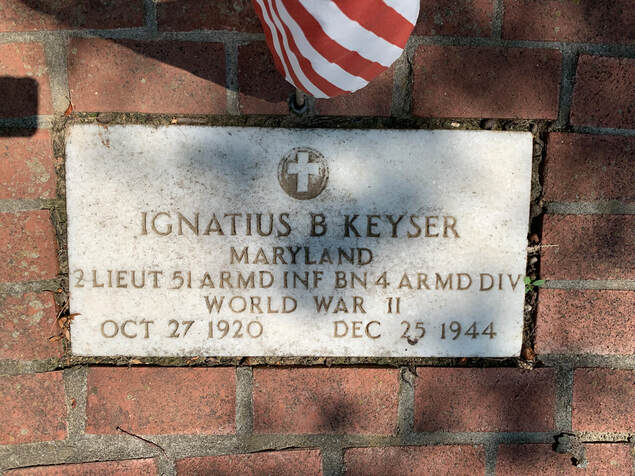

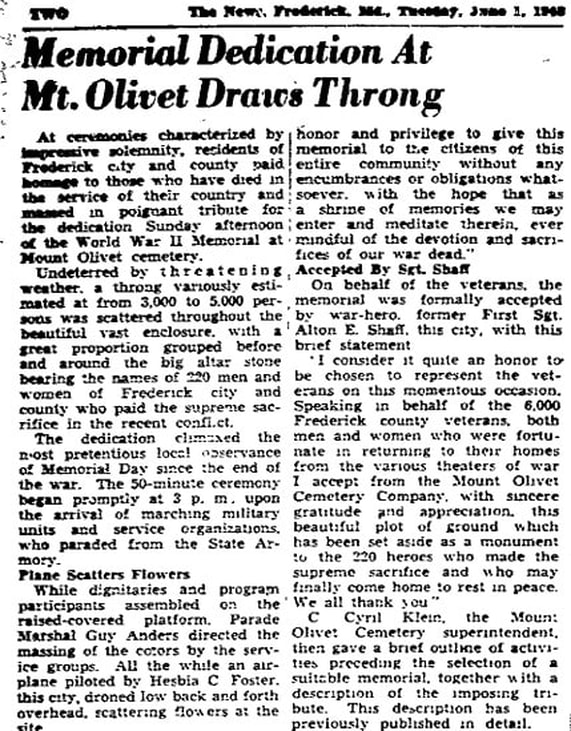

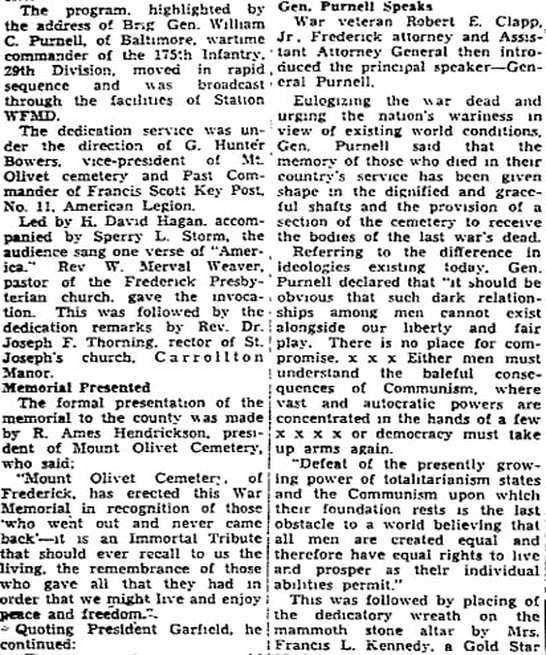

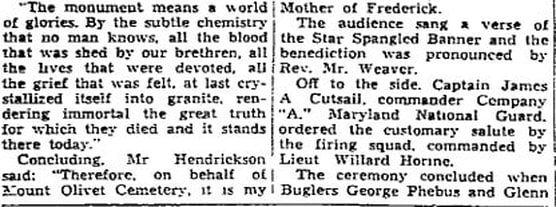

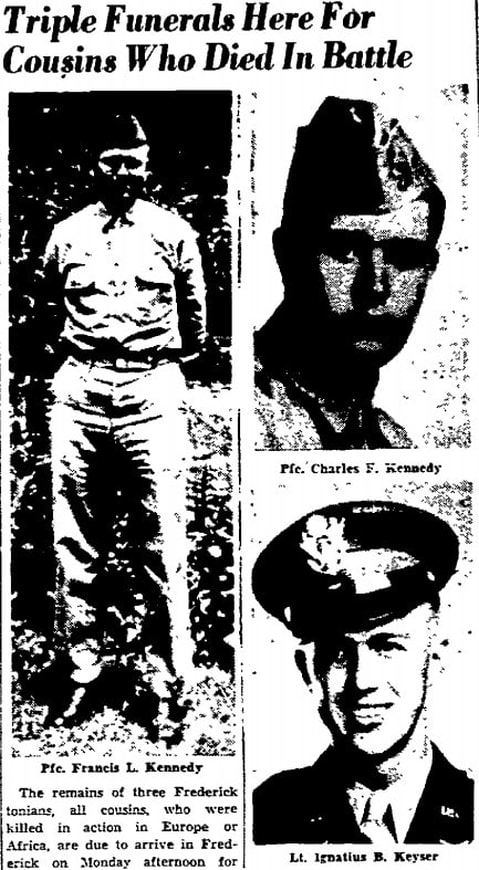

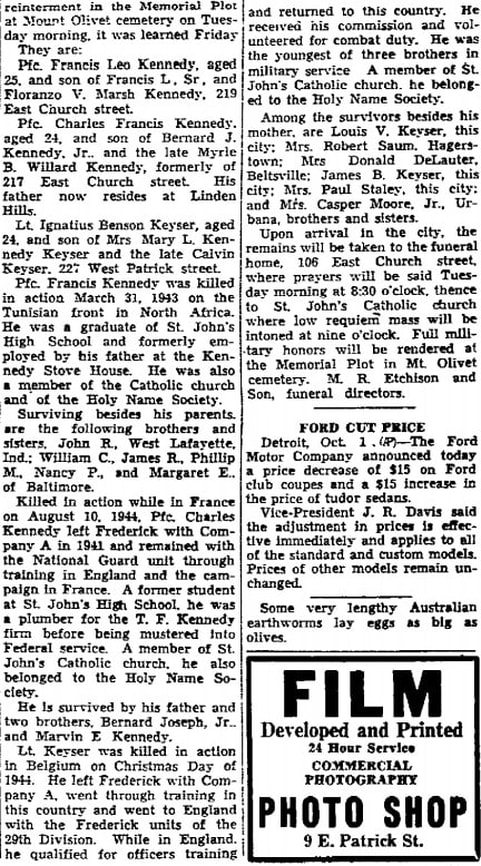

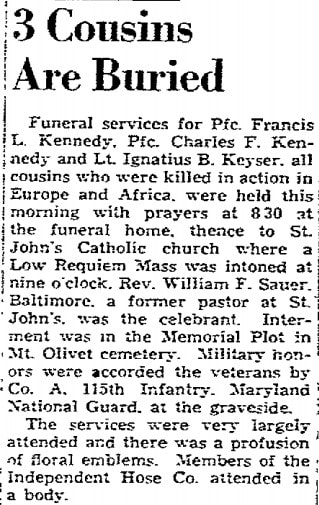

On September 2nd, 1945, Japan’s formal surrender took place aboard the USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. There is a little bit of controversy tied up in the date of surrender because Americans first heard Japan’s emperor Hirohito actually make his announcement of surrender on national radio on August 14th. Again, to clarify, September 2nd marks the formal signing of the surrender document. Regardless, both later dates came several months after the surrender of Nazi Germany, and hold a bit more weight as they officially ended World War II. The significant “lettered” day(s) became known as “V-J Day,” and was added to the vernacular along with “V-E Day” (May 8th, 1945) and “D-Day” (June 6th, 1944). Japan’s defeat brought an end to six years of hostilities in the Pacific Theater of War. As can be imagined, this event was highly anticipated in bringing a peaceful return to American life, especially in the form of having soldiers, sailors and others serving in the armed forces( and hospital centers) back home. Nothing better describes the feeling of “V-J Day” back home than an iconic picture most of us have seen. It captures an impromptu kiss in New York’s Times Square featuring a US sailor and a nurse. Entitled V-J Day in Times Square, the photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt was published in Life Magazine in 1945 with the caption, "In New York's Times Square a white-clad girl clutches her purse and skirt as an uninhibited sailor plants his lips squarely on hers."  While I have the opportunity, Frederick has a connection to this world-renowned photo. The nurse was a one-time Frederick, Maryland resident named Greta (Zimmer) Friedman (June 5th, 1924 – September 8th, 2016). The Austrian native was actually a dental assistant with a uniform similar to that of a nurse. At the time of the photograph, Greta suddenly found herself grabbed and kissed by Navy sailor, George Mendonsa (1923–2019) on that celebratory day of August 14th, 1945. It was a happy day of sorts for Greta as much as her veteran counterpart. She had experienced much heartache and fear over the previous six years. In 1939, at the age 15, Greta emigrated to America from Nazi-controlled Austria in with her younger sisters Josephine and Belle. Their parents, Max and Ida, unable to leave Europe, died in concentration camps during the Holocaust. A decade after the photo was taken, Greta was married in 1956 to Dr. Mischa Friedman, a WWII veteran of the U.S. Army Air Corps and a scientific researcher for the Army at Fort Detrick. She would move to Frederick and lived at 314 W. College Terrace. She eventually attended Hood College, studying oil painting, printing, sculpture, and watercolors. She did not graduate until 1981, the same year her two grown children (Mara and Joshua) also graduated from college. Friedman worked for ten years at Hood restoring books. Greta Friedman died at age 92 on September 8th, 2016, in Richmond, Virginia. She is not in Mount Olivet, but instead inurned at Arlington National Cemetery beside her husband. As for Greta’s photo counterpart, memorialized forever in a photograph—George Mendonsa died last year after seven decades of proudly recounting the kiss that brought him fame. Just as important to him, were his stories told about his time aboard the USS The Sullivans, a ship named for five brothers from Iowa who died when their ship, the USS Juneau, was sunk by a Japanese submarine in 1942. This family tragedy was part of the impetus for the storyline in the motion picture “Saving Private Ryan.” United States Army Rangers Captain John H. Miller (Tom Hanks) and his squad were tasked with the search for a paratrooper, Private First Class James Francis Ryan (Matt Damon), the last surviving brother of a family of four, with his three other brothers having been killed in action. The Sullivan brothers enlisted in the US Navy on January 3rd, 1942, with the stipulation that they serve together. The Navy had a policy of separating siblings, but this was not strictly enforced. George and Frank Sullivan had served in the Navy before, but their brothers had not. All five were assigned to the light cruiser USS Juneau.The Juneau participated in a number of naval engagements during the months-long Guadalcanal Campaign which began in August 1942. Early in the morning of November 14th, 1942, during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, the USS Juneau was struck by a Japanese torpedo and forced to withdraw. Later that day, as it was leaving the Solomon Islands' area for the Allied rear-area base at Espiritu Santo with other surviving US warships from battle, the Juneau was struck again, this time by a torpedo from a Japanese submarine. The torpedo likely hit the thinly armored light cruiser at or near the ammunition magazines and the ship exploded and quickly sank. As a direct result of the Sullivans' deaths (and the deaths of four of the Borgstrom brothers within a few months of each other two years later), the US War Department adopted the Sole Survivor Policy: "Special Separation Policies for Survivorship" describes a set of regulations in the Military of the United States that are designed to protect members of a family from the draft or from combat duty if they have already lost family members in military service.” Some may recall a “Story in Stone” written back in December 2016 about former county resident Ray Jacob Stambaugh, buried here in Mount Olivet within the confines of our World War II monument. He was a native of Jimtown, a small crossroads southeast of Thurmont where MD route 550 and Hessong Bridge Road intersect Moser Road. Jacob Stambaugh served as a fireman on a ship in the US Navy. He would die not far from where the Sullivan brothers perished near Espiritu Santo. He was reported missing in action in early September, 1942. An article in the Frederick News (dated October 3rd, 1942) confirmed Stambaugh’s death at the age of 21. He would be the first World War II Naval casualty from Frederick County. Interestingly, Jacob’s death would inspire his only brother, Luther M. Stambaugh, to immediately enlist in the US Navy upon hearing of his sibling’s death. Ray Jacob Stambaugh actually died on August 4th, 1942 aboard the USS Tucker. I soon found the following account documenting an event that occurred off the South Pacific island of New Hebrides: “The Tucker entered the harbor at Espiritu Santo's western entrance, leading the cargo ship SS Nira Luckenbach, unaware they had entered a minefield laid earlier by US Navy minelayers. After striking at least one mine, the destroyer was almost torn in two at the No. 1 stack, killing all three of the crew in the forward fireroom. The rest of the crew survived but Tucker did not. The destroyer slowly settled in the water and sank. An investigation revealed that the USS Tucker had not been given information about the existence of the minefield.” I wrote the particular story (about Stambaugh) as the cemetery co-hosted a solemn commemoration with our DAR partners in December, 2016 in accordance with the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Interestingly, Jacob Stambaugh was aboard the USS Tucker the previous year which survived Japan’s devastating surprise, aerial attack on the US naval base on December 7th, 1941 at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Hawaii. This “day of infamy” capped a decade of deteriorating relations between Japan and the United States and led to an immediate US declaration of war the following day. Japan’s ally Germany, led by Adolf Hitler, then declared war on the United States, turning the war raging in Europe into a global conflict. Over the next three years, superior technology and productivity allowed the Allies to wage an increasingly one-sided war against Japan in the Pacific, inflicting enormous casualties while suffering relatively few. By 1945, in an attempt to break Japanese resistance before a land invasion became necessary, the Allies were consistently bombarding Japan from air and sea leading to V-J Day in mid-August and the formal surrender just weeks later on September 2nd. Cemeteries: War's Grim Reality Over 200 soldiers, sailors and pilots from Frederick County lost their lives in World War II. In the years following the conflict, the federal government offered families the option of having fallen loved ones returned to the United States for reburial, or memorialized in one of 25 national veteran cemeteries abroad and located in ten foreign countries including France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, Panama, Italy, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands and Tunisia. As was the case in World War I, the bodies of many local casualties returned home and are buried in cemeteries throughout the county. Several are here within Frederick's Mount Olivet. With assistance from a myriad of local groups and donors, a monument was proposed and built here to honor the memory of those 200+ former residents who made the ultimate sacrifice. It lies within Mount Olivet Cemetery’s Area EE, and was originally dedicated on May 30th, 1948. The double-columned monument, made of Indiana limestone, features a central obelisk containing the names of 219 individuals from all parts of Frederick County. Atop this pilaster is a sculpted eternal flame of gold, below which read: “The flame of love shall burn into our hearts the memory of our noble dead.” What makes this memorial even more sacred is the fact that it is flanked by the remains of 30 World War II veterans who died in the line of duty in both Europe and the Pacific. These men are buried in a semi-circular design around the monument and their final resting spots are marked by flat, military-issue stone markers of white marble.  Baltimore Sun (July 10, 1939) Baltimore Sun (July 10, 1939) Here is a brief overview showing the location of death for the 30 active-duty casualty victims interred here within MOC’s World War II monument: Traditional Pacific Islands/Pacific Theater 7 Southern Pacific (India) 1 Traditional Europe/ European Theater (France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, England) 19 Southern European Theater (Italy) 2 Africa (Tunisia) 1 In addition to the fore-mentioned Ray Jacob Stambaugh, a breakdown of those seven other boys who died in the Pacific Theater shows that two men, 2nd Lt. Nathan G. Dorsey, Jr. (1919-1945) and PFC Earl Mason Harwood (1924-1945), died on the Japanese Island of Okinawa. Nathan G. Dorsey was a former schoolteacher from Mount Airy, somewhat reminiscent of Capt. Miller (Tom Hanks) in Saving Private Ryan. Ironically, I found a newspaper article dating from July, 1939 which reported the College Park (Maryland) grad was responsible for Japanese Beetle control in his hometown as it was affecting farm crops and the local canning business. Dorsey’s father was a well-known businessman who dabbled in politics at various levels. He would serve as mayor of Mount Airy at the time of his son’s participation in the war. 2nd Lt. Nathan G. Dorsey would die in May, 1945 and was buried in a military cemetery in the Pacific. His body would be brought back to the US in 1949, and soon after re-interred in Mount Olivet within the World War II Memorial. PFC Harwood was a native of Burkittsville and a standout baseball player at Brunswick High who was drafted by the New York Yankees and expected to play for one of their minor league teams after the war. He was the youngest of six sons, five of whom served in the Armed Forces. He landed on Okinawa on Easter Sunday, April 1st, 1945, and was killed in action on May 11th. Harwood was buried in Mount Olivet on March 12th, 1949, three days before 2nd Lt. Dorsey was laid to rest. Irvin B. Gaver (1921-1944), a resident who once lived at 410 W. South Street in Frederick, perished in a plane crash at Midnapore, India. The recent newlywed and Frederick High grad was serving as a flight officer within the US Army’s Air Force. Sadly, Mrs. Gaver (the former Claudine Smith) learned of her husband’s death on August 14th, 1944 through the War Department’s usual message of sympathy to bereaved relatives, and not through an initial telegram with such news as was customary. Flight Officer Gaver had died on July 26th, and Mrs. Gaver had last received a letter from him dated July 22nd. I was able to find the following official report of the accident on the internet courtesy of the Flight Safety Foundation: The Boeing B-29 Superfortress crashed at Midnapore, Paschim Medinipur district of the Indian state of West Bengal, India (at approximate Coordinates: 22.424°N 87.319°E) due to engine failure after take-off from Chakulia Airfield, Purbi Singhbhum district, State of Jharkhand, India 26 July, 1944. Nine of the thirteen crew were killed (seven in the crash, two died later in hospital). "STATEMENT OF CAPT ALVIN E. HILLS, JR. AIRPLANE COMMANDER #42-6291 As told to Major R. M. McGlinn, Accident Officer “We took-off from Chakulia, India, at 07:35 IST, climbed on a course of 72 degrees for 5 to 10 minutes and then changed course to 84 degrees, continuing our climb until reaching an altitude of 1,000 feet. The flight engineer advised #2 Cylinder head temperature was reading 270 degrees, and advised levelling off for cooling. We flew for approximately ten minutes in level flight when Co-Pilot noticed #3 engine on fire. I feathered #3 engine, advised the flight engineer to cut #3 engine fuel shut-off valve off, and use the fire extinguisher. The use of the fire extinguisher showed no help what-so-ever. I started a slow turn to the left and after 10 or 15 degrees were accomplished, #2 engine started to cut out, dropping from 2400 to 2000 back to 2400 and then 1500 RPM. I advised the Bombardier to salvo the bombs and forward bomb bay tank. (The Bombardier had a little trouble operating the salvo mechanism.) The Co-Pilot advised crew members, over the interphone, to prepare for an emergency landing. I did not try to feather #2 engine, (I believe the Co-Pilot in the confusion tried to un-feather #3 engine, as there was a terrific drag on that side.) A moment later, #1 and #4 engines began cutting out. I could not maintain level flight, dropped the nose to pick up air speed and broke through the clouds at approximately 100 feet and found a clear area. I made a normal approach for a normal belly landing. Just before contact, I notified the flight engineer to cut the switches. Normal contact was made with the ground at about the radar section, and an explosion occurred on the right side. We slid along the ground for quite a distance and then came to a sudden stop. By this time, the entire cabin of the plane was filled with flames. I proceeded through the Pilot’s window to safety. I then helped Lt Houston, the co-pilot, out to the bank of a creek, away from the flames. Lt. DiLollo was dazed and was walking around in front and to the left of the front." Four other victims of the Pacific Theater buried within the the proximity of the Mount Olivet World War II Memorial died while in active duty in the Philippines. The Philippines campaign (also known as the Battle of the Philippines or the Fall of the Philippines) occurred from December 8th, 1941 – May 8th, 1942 and featured an invasion by Imperial Japan and the defense of the islands by United States and Philippine forces. In November, 2019, I wrote a “Stories in Stone” article about Brigadier General Allan Clay McBride, entitled “Marched to Death.” A former resident of both Jefferson and Frederick City, Allan C. McBride (1885–1944) was an American brigadier general and chief of staff in the Philippines at the time of the Japanese invasion. He would survive the infamous Bataan Death March, but would die in a Japanese Prisoner of War camp on the nearby island of Formosa, better known today as Taiwan. The Japanese launched the invasion by sea from Formosa, over 200 miles north of the Philippines. The defending forces outnumbered the Japanese by 3 to 2, but were a mixed force of non-combat experienced regular, national guard, constabulary and newly-created Commonwealth units. The Japanese used first-line troops at the outset of the campaign, and by concentrating their forces swiftly overran most of country's largest island, Luzon, during the first month. The Japanese high command, believing they had won the campaign, made a strategic decision to advance by a month their timetable of operations in Borneo and Indonesia, withdrawing their best division and the bulk of their airpower in early January 1942. This, coupled with the defenders' decision to withdraw into a defensive holding position in the Bataan Peninsula, enabled the Americans and Filipinos to successfully hold out for four more months. Japan's conquest of the Philippines is often considered the worst military defeat in United States history. About 23,000 American military personnel and about 100,000 Filipino soldiers were killed or captured. Three individuals who died there are buried here in this hallowed ground immediately surrounding the eternal flame monument: Cpl. George William Ford, PFC Mehrle E. Leatherman, and Pvt. Russell Yinger Dansberger. Now, I’ve just summarized the lives, and deaths, of simply seven of the 30 servicemen buried by our World War II monument/memorial. Keep in mind that there are several other World War II vets buried in the cemetery who also died in active service, but with this article I am just focusing on those buried in the semi-circle at the memorial. Outside of those connected to the War in the Pacific, and especially revered on this monumental 75th anniversary of “V-J Day,” nineteen others died in northern Europe, primarily in France and Germany, with a few succumbing in Belgium, Holland and England. Two additional soldiers fell in Italy and another perished in Tunisia while seeing combat in the war's North African campaign. Of special note, I'd like to tell you about a few other slabs of marble which rest over the bodies of a set of Frederick County brothers killed during active duty during World War II. Next to them is a trio of cousins, I’d also like to introduce their story to you. The Hessong Brothers Your familiarity with this peculiar name may be based more on the famed Frederick County road (and bridge) mentioned earlier in conjunction with Ray Jacob Stambaugh’s home than by knowing an actual acquaintance by this surname. John T. Hessong (1848-1922) was a farmer whose property was located at the intersection of Black Mills Road and his namesake, Hessong Bridge Road. The Hessongs, or earlier Hessons, came from the Alsace region between France and Germany and settled here locally atop the western slope of Catoctin Mountain in the northwestern area of Frederick County of Wolfsville and Ellerton. Although I'd love to continue this genealogical study, I will skip ahead to descendants that distinguished themselves in the Second World War. Hailing from the Wolfsville area, the Hessong brothers, Robert and Arthur, were sons of farmers James Ellsworth Hessong and Sadie Ellen Brandenburg. There were 12 Hessong siblings in all, the last of which, Paul, passed away in October, 2018 at the age of 89. Robert Lee Hessong was born on April 19th, 1922 and went by the nickname of Bob. He served in the 26th Infantry of the 1st Division of the US Army and reached the rank of Private First Class. Hessong was killed in action in Normandy, France on June 12th, 1944, having taken part in the legendary D-Day Invasion. His unit landed on Normandy at 7:30pm on D-Day. He would die a week later in the coastal town of Caen. Instead of having their son buried in the family’s home church of St. Mark’s Lutheran in Wolfsville, the Hessongs opted to have him buried in Mount Olivet on September 18th, 1948. PFC Robert Lee Hessong occupies lot #10 within the cemetery’s World War II memorial area. In addition to the fore-mentioned “Bob” Hessong, three other brothers were serving in various branches of the armed services. However, less than two months after the death of Robert, the Hessong family would receive more terrible news—the death of son Arthur Jacob Hessong. PFC “Art” Hessong was a member of the Army’s 141st Infantry Regiment assigned to the 36th Division. He too would die in France, but in the southern part of the country. The 24-year-old was born on March 13th, 1920. Like his younger brother, Arthur was buried in Mount Olivet under the shadow of the World War II Memorial on the same day of September 18th, 1944. He occupies Lot #11. As can be seen in the articles, both Robert and Arthur had experienced earlier combat action in Italy. Thankfully for Mr. and Mrs. Hessong, they would be reunited once again with sons Joseph (1915-1972) and Parker (1924-1990), upon their safe returns home after the war. Kennedy Cousins Next to the Hessong brothers, lie three cousins, buried side by side within Mount Olivet’s World War II Memorial. They are PFC Francis Leo Kennedy, Jr., PFC Charles Francis Kennedy and Lt. Ignatius Benson Keyser. The Irish Catholic family of brothers who would dominate political fame would come a few decades later, but this one would certainly be known to Frederick Countians during wartime because of losses experienced. That seems to be an interesting irony as well? Francis Leo Kennedy, Jr., the son of Francis Leo Kennedy, Sr. and Flora Victoria Marsh was killed on the Tunisian front in North Africa on March 31st, 1943. He lived at 219 E. Church Street in downtown Frederick and attended St. John’s Catholic High School a block from his home. Previous to going into the service, he worked with his father at the Kennedy Stove House. He served in the US Army’s 16th Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division. Francis Kennedy's parents received additional bad news the following year in 1944 as their son John would be reported "missing in action." There is some good news tied to this story as John Robert Kennedy did not perish, instead spending the remainder of the war in a POW camp. The B-24 pilot in the Army Air Corps was assigned as part of the 489th Bomb Group consisting of all B-24 bombers. He was a prisoner of war in Germany, having been shot down on August 6th, 1944, on his 24th mission. He was imprisoned in Frankfurt, Germany, then taken by boxcar to Sagen, East Germany, to Stalag VIIA. He was liberated on April 29th, 1945. John Robert (an ironic name as well for this Kennedy connection) returned to Frederick and soon headed to Indiana where he received an associate's degree from Vincennes University in May 1947, and a bachelor's degree in aeronautical engineering from Purdue University in May 1949. He worked for the Department of Defense at Camp Detrick back in Frederick from June 1949 to November 1958. John would return to Indiana and lived there until his death in 2007 at the age of 81. (Note: John Robert Kennedy is buried with his immediate family in Vincennes). Charles Francis Kennedy, the son of Bernard Joseph Kennedy, Sr. and Myrtle Blanche Woullard, grew up next door to his cousins Francis and John in a rowhouse located at 217 E. Church Street. Born December 3rd, 1919, he was a member of the 115th infantry regiment of the US Army’s famed 29th Division. Charles lost his life on August 10th, 1944 as he was killed in France. Francis and Charles had a paternal aunt named Mary Louise (Kennedy) Keyser, the wife of Calvin Vincent Keyser. The Keysers were the parents of Ignatius Benson (born October 27th, 1920). Lt. Ignatius B. Keyser was a member of the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion of the US Army’s 4th Armored Division under Gen. George S. Patton. He was killed in action near Bastogne, Belgium on Christmas Day, 1944. The sacrifices made by the Hessongs, Kennedys and countless others in uniform led to "V-E Day," celebrated on May 8th, 1945. Their county, countrymen and fellow soldiers would not forgot their loss. A monument listing the names of all World War II servicemen and women from Frederick County was dedicated in Memorial Park at the corner of W. Second and N. Bentz streets. As I recounted earlier, plans were made for an eternal reminder here in Frederick's "Garden Cemetery" as well. The dedication ceremony was held for Mount Olivet’s World War II Memorial on May 30th, 1948 at 3:00pm. The ceremony was well-attended and featured an address by Brig. Gen. William C. Purnell, War Time Commander of the 175th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Division. One of the most poignant moments of the ceremony came with the placing of a wreath of dedication to all those Frederick young men who made the greatest sacrifice on behalf of their country. A Gold Star mother was chosen for this important honor. It was Mrs. Flora Kennedy, mother of Francis Leo Kennedy, Jr. and former POW John Robert Kennedy. Mrs. Kennedy’s son, Francis Leo, and her two nephews would be buried five months later on October 5th, 1948 in Mount Olivet, after having been buried first overseas. We think we've had it rough in the year 2020? We will forever be "holding the beers" for those of the "Greatest Generation" who truly knew sacrifice for our freedoms, while celebrating life's blessings always and often. One of the greatest was the final end of World War II, seventy-five years ago on "V-J Day."

2 Comments

Nancy Droneburg

9/2/2020 08:06:46 pm

wonderful

Reply

6/28/2023 12:43:49 am

Thanks for posting and all the research: above all, thanks for remembering our veterans. God bless them.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed