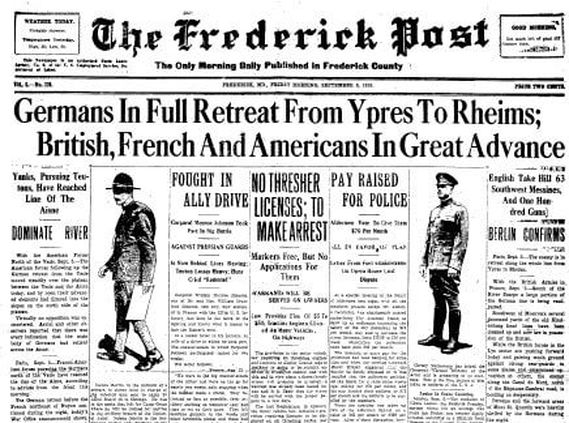

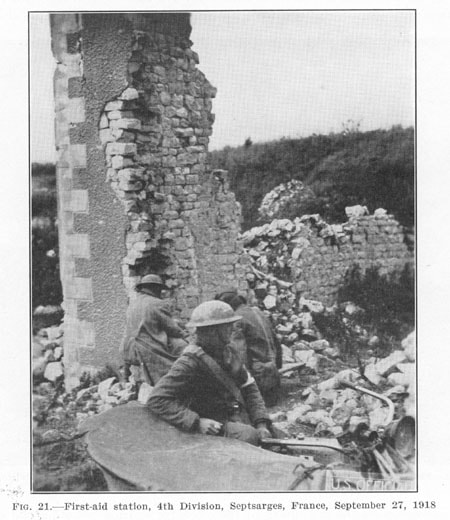

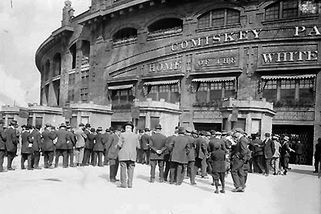

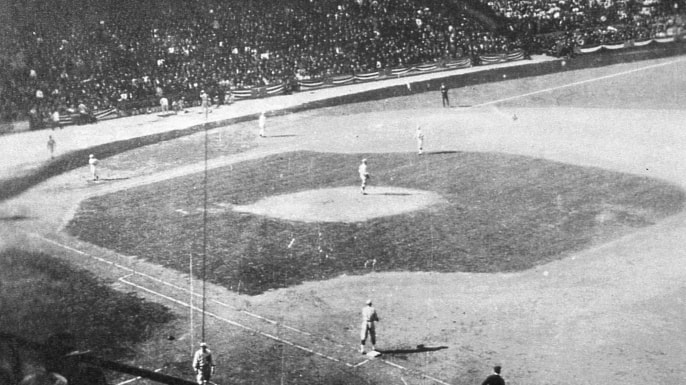

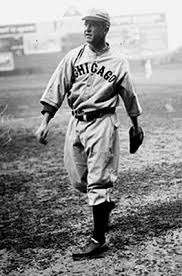

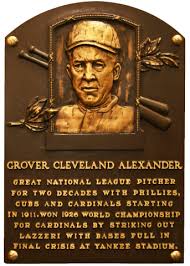

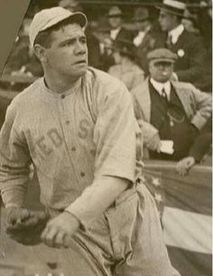

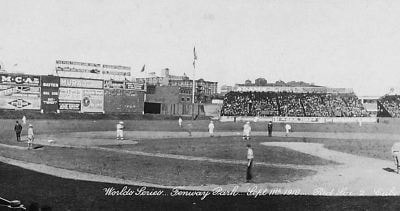

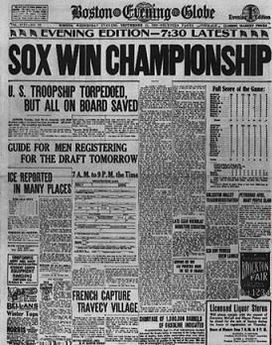

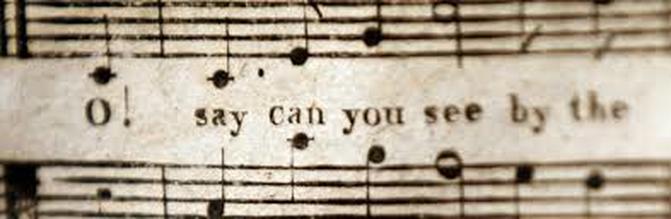

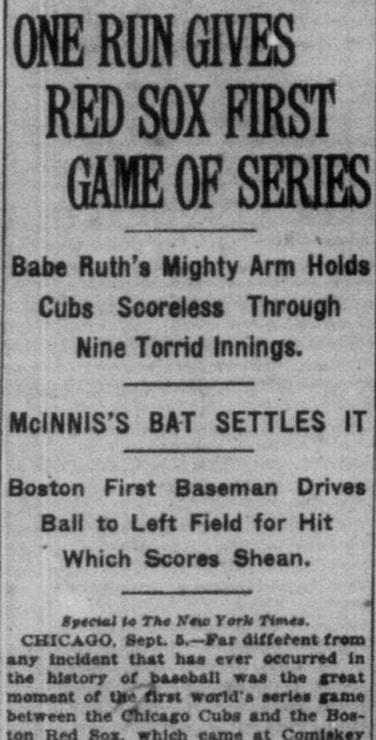

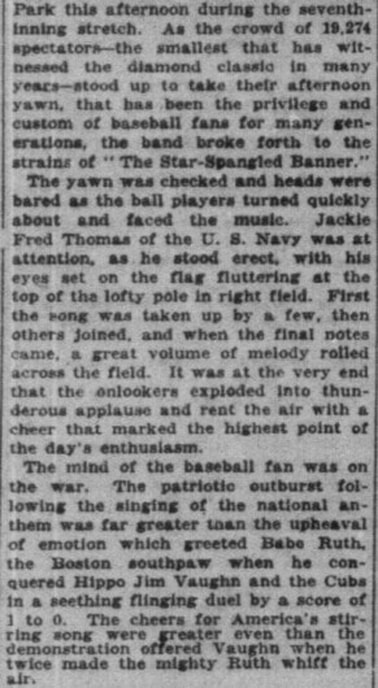

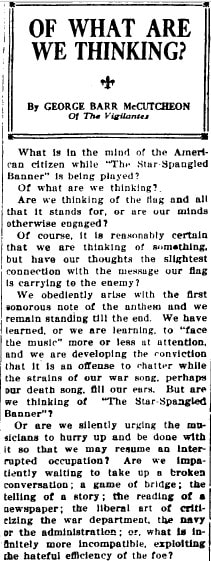

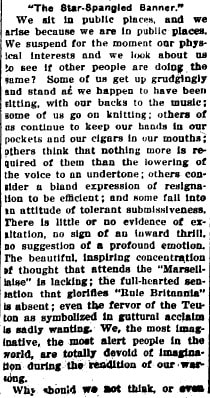

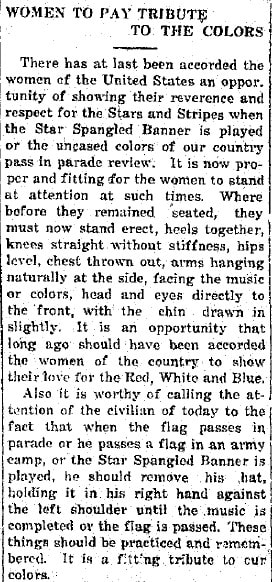

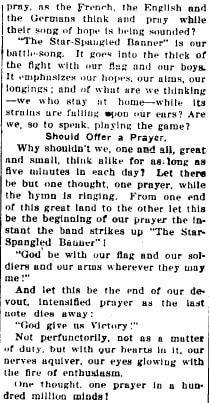

There are many rewards to working at a place like Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, so steeped in history. And I’m not just talking about the history of our fair city and county, but more so, the United States of America. One such perk is the unique opportunity to hear “The Star-Spangled Banner” being sung next door at Nymeo Field at Harry Grove Stadium. This is the home of our minor-league baseball team—the Frederick Keys. Now to be specific, our cemetery grounds are spacious, encompassing 100 acres adjacent the neighboring ballpark. The best place to be for this patriotic occurrence is in the shadow of the Francis Scott Key Monument near the front entrance off S. Market Street. This site doubles as the final resting place of the man who authored the legendary song, all the while being held captive aboard a British ship in Baltimore Harbor during the Battle of Fort McHenry on September 13-14th, 1814. Nowadays, the national anthem can be played about anywhere, especially where sports live and breed. When it comes to the gravesite of this guy who gave us the song (played at the Olympic Games and synonymous with “kicking off” most professional sporting events), the Frederick Keys are by far the closest in proximity. They are also named for him for goodness sake! And baseball and “The Star-Spangled Banner” seem to go together like peanut butter and jelly, don’t they? “The Star-Spangled Banner” has traditionally held high honor as the anticipated lead-in to major sports championships, and is usually performed by high profile musical artists. Who can forget Whitney Houston’s amazing rendition before Super Bowl XXV in late January 1991, made all the more meaningful as our country was entrenched in the Persian Gulf War at the time. A decade later, the song would take on heightened importance before games and matches of all kinds in the aftermath of the tragic 9-11 terrorist attacks. A “Star-Spangled Time” Exactly one century ago to the day (Thursday, September 5th, 1918), the country was embroiled in World War I. Frederick City and towns across the county had sent their boys into action. Many of these were in Europe, strangely taking on a major aggressor in German—a familiar country whom many here drew their heritage from in earlier generations. As an aside, Frederick Town (and later county) was so named in 1745 for Prince Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-1751). This was the son of King George II and hailed from the House of Hanover. His mother, Caroline of Ansbach, was also of German extraction. This was employed as a brilliant marketing strategy by town and county founder Daniel Dulany to attract German immigrants, some from Europe and others already settled in Pennsylvania. By September, 1918, Frederick County had already heard the news that 7 of its citizens had already made the ultimate sacrifice in the Great War. Only 53 years removed from the American Civil War, this location, along with our entire country experienced a wave of patriotism like never seen before. It had been 17 months since we entered the war and 100,000 American deaths had been recorded as a result. Many more would follow in the next few months. This was said to be “the war to end all wars” and boasted unified population in cause and effort. One could say that the collective “we” was very confident in the abilities of our “fighting team,” but at the time, it is safe to say that “we” were equally scared and nervous about the state of the union. This was a tough opponent, and warfare during this time had grown into a particularly ugly and non-Romantic affair as compared to how folks drew on the Civil War and American Revolution for inspiration. The fighting was rough, involving improved side weapons and artillery, trench warfare, poison gas attacks and flamethrowers. Many fighting men died from the disease, primarily the Spanish Influenza. This deadly “12th man” of the enemy even made its way back home that fall, killing thousands of US civilian, with hundreds right here in Frederick County. Many Americans, here at home, simply looked to the game of baseball as a tension release. Who would know at the time, and more importantly on that particular day of September 5th, 1918, that the sport would become synonymous with national pride and patriotism from this point forward? The national pastime would earn its “national” billing. And to think it was all primarily due to a nod to the song written by Mount Olivet Cemetery’s perennial greeter, Francis Scott Key. A “World” Series to Remember September 5th, 1918 and the scene was Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois as the hometown Cubs hosted the Boston Red Sox for Game 1 of the World Series. The fabled “October Classic” was in its 16th year and had purposely been moved up to September due to the war. The federal government’s Selective Service Division had issued a “work or fight” order requiring all able-bodied men to either serve in the military or work in a “necessary” civilian occupation. Professional athletes were not immune. The regular season had been shortened for this fact, having ended on September 1st.  Sgt. Grover Cleveland Alexander Sgt. Grover Cleveland Alexander Interestingly, the Chicago Cubs best pitcher, Grover Cleveland Alexander had already spent most of the 2018 baseball season with the US Army in France for the war effort as a sergeant with the 342nd Field Artillery. While he was serving in France, he was exposed to German mustard gas and a shell exploded near him, causing partial hearing loss and triggering the onset of epilepsy. Following his return from the war, Alexander suffered from shell shock and was plagued with epileptic seizures, which exacerbated a drinking problem. Although people often misinterpreted his seizure-related problems as drunkenness, Alexander hit the bottle particularly hard as a result of the physical and emotional injuries inflicted by the war, which plagued him to his grave. Meanwhile, the starting pitcher for the Red Sox was a man named Ruth—Herman “Babe” Ruth to be exact. The Babe was as dominant on the mound as he was at the plate. He would pitch a shutout in Game 1, with his Red Sox winning 1 to 0. He would win his second outing in Game 4 and the Red Sox would go on to win the World Series by a count of 4 games to 2. This was Boston’s third World Series win in four years as they had also won 5 out of the first 15 baseball championships. Many are familiar with the interesting things to follow in the realm of baseball as Babe Ruth would be traded to the Yankees and go down as one of the greatest human beings to ever play the game. We even have a youth sports organization in our community named for the man. Players ages 13 to 19 play on diamonds such as Loats Field, also located adjacent Mount Olivet and the grave of Francis Scott Key. As for the Red Sox, they would not win another World Series for 86 years. The Chicago Cubs went on to lose World Series in 1929, 1932, 1935, 1938 and 1945. After a drought of 71 years, the Cubs finally made it to another World Series in 2016. This time, the seemingly cursed franchise made the most of it by defeating the Cleveland Indians. Speaking of Cleveland, Sgt. Grover Cleveland Alexander would at least have the opportunity to come back to the United States, and more so, play professional baseball after his service overseas. Eight of his fellow major leaguers did not have this chance, having been killed overseas during World War I. Seventh-Inning Stretch The most notable thing to happen during that Game 1 of the 1918 World Series actually had nothing to do with the baseball action on the field. No, it was clearly something that was generated from the stands. It was something that would have an everlasting effect on the fans, players, baseball and the entire gamut of American sports. That something was “The Star-Spangled Banner” written by Frederick’s native son Francis Scott Key.  This wasn’t the first time “The Star-Spangled Banner” was played at a sporting event. Apparently it has been documented as having been played at a baseball game in 1862 during the Civil War. It was also played in the 1890’s, on several occasions during the time of the Spanish American War. The events of September 5th, 1918 served as a major lynchpin—a tradition was born. Key’s song was played again in Chicago during Games 2 and 3. When the Series moved to Boston for Game 4, the Red Sox played the song during pregame festivities and paired it with the introduction of wounded soldiers, a theatrical move by Red Sox owner Harry Frazee. “The Star-Spangled Banner” quickly became the nation’s de facto anthem not long after. Congress made it official in 1931, after World War I vets had been lobbying for it for years. The song was still not played at all games in those days as team owners didn’t have bands on-hand to play the song. However, it was a staple of large events such as Opening Days and playoff and championship games. Another technology non-existent at this time was that of public address and credible sound systems. These would, however, be put in place by World War II, and the tradition was popularized to regular games.  The rest, as they call it, is history. Unfortunately, you may have heard that in recent years, the patriotic ditty has somehow gotten caught up in controversy. Some folks have different perceptions of what the song means, along with its place in national importance, and its role in the sporting event realm. I won’t be the first to tell you that we can learn a great deal from our past, as my livelihood has depended on this notion for many years. This project was as interesting as it is timely with the advent of another professional football season. More importantly, we are approaching the 204th anniversary of the writing of our anthem by Mr. Key (September 14), and the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I with the Armistice of November 11th, 1918.  I came across several evocative articles in doing a newspaper “key word” search for “Star-Spangled Banner” on the same day of September 6th, 1918—the day newspapers reported what occurred between sides of the seventh inning of Game 1 of the 1918 Series. I found several accounts of the song being played at patriotic sendoffs of troops from railroad platforms and ship docks across the country. I also uncovered references to its sounding in small town park rallys and memorial services throughout the land. A few other articles really caught my eye, and I felt that I should include as an addendum for your reading pleasure. History is a great thing, a true roadmap for the future. It also represents music to this humble writer’s ears—sort of like hearing the national anthem being sung at Grove Stadium, from the vantage of Francis Scott Key’s gravesite in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

2 Comments

Nancy Droneburg

9/7/2018 04:41:38 pm

thank you

Reply

shane shanholtz

9/8/2018 12:28:19 am

great story

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed