|

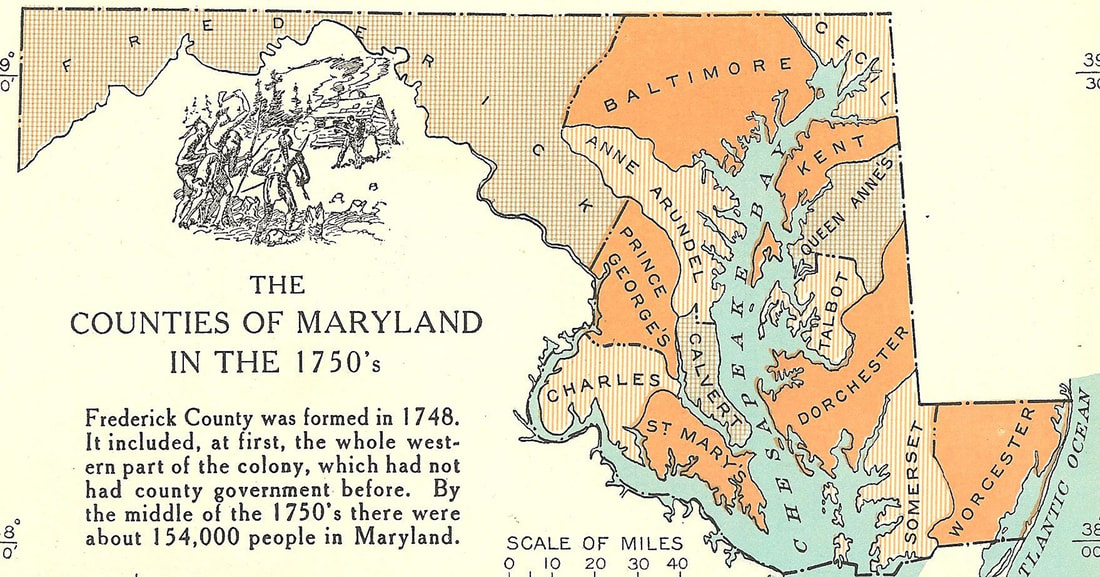

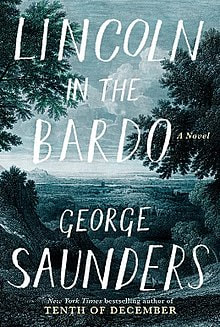

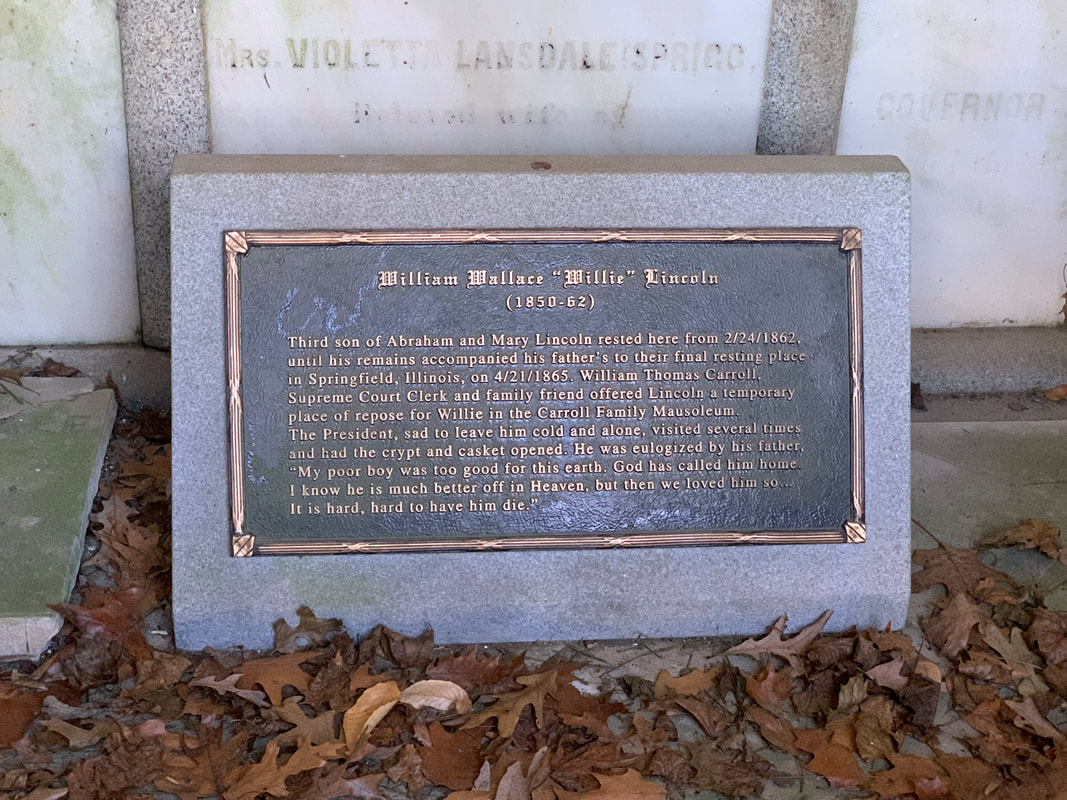

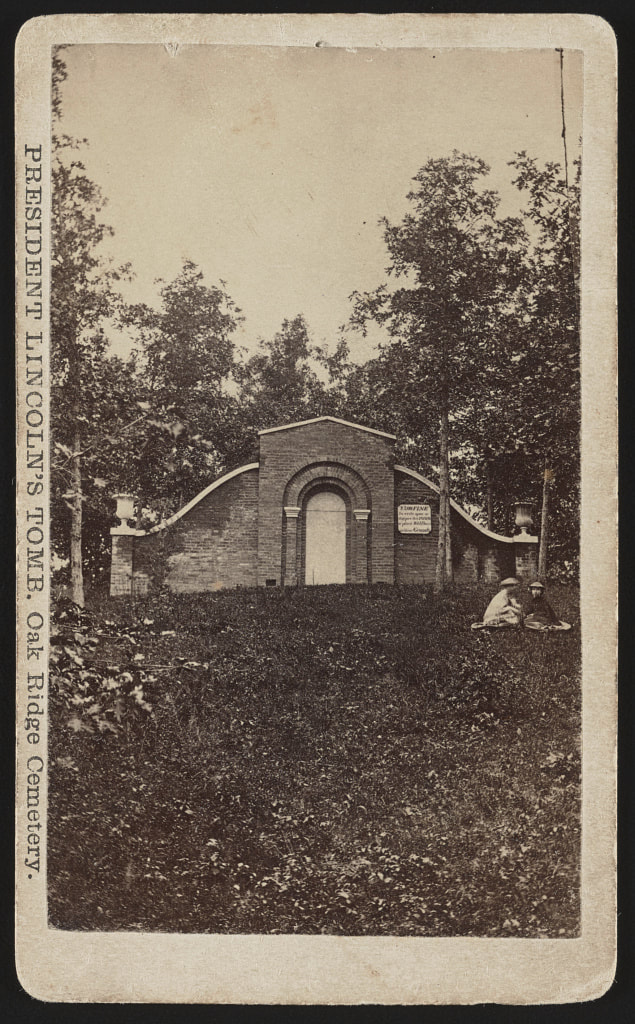

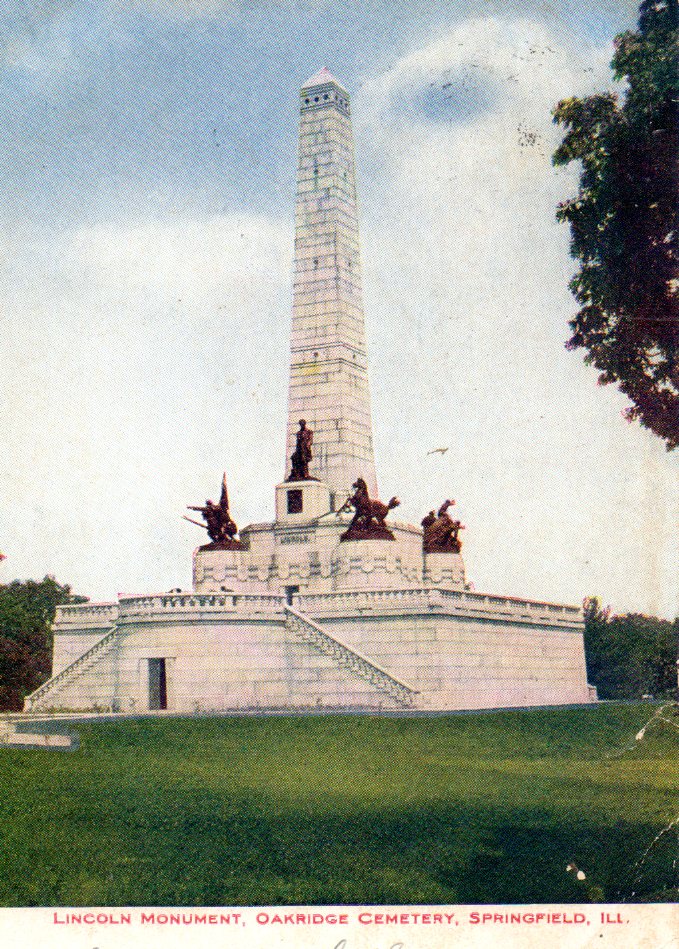

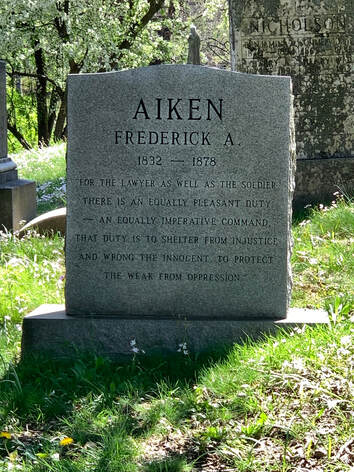

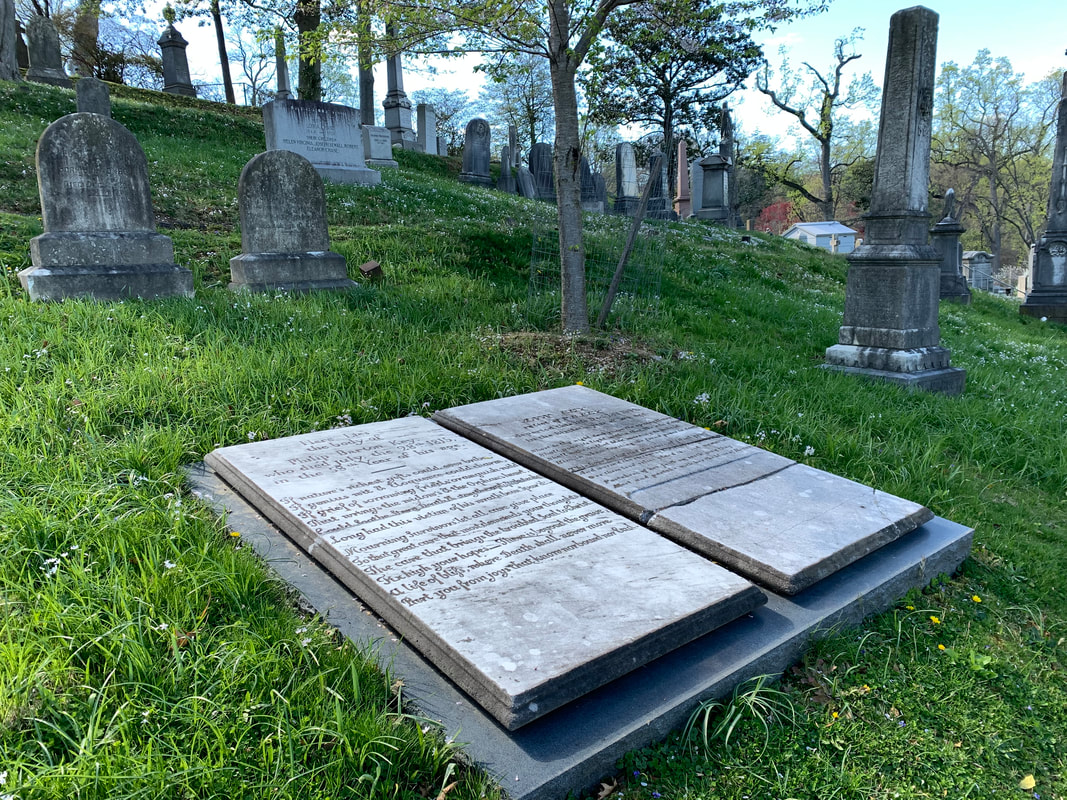

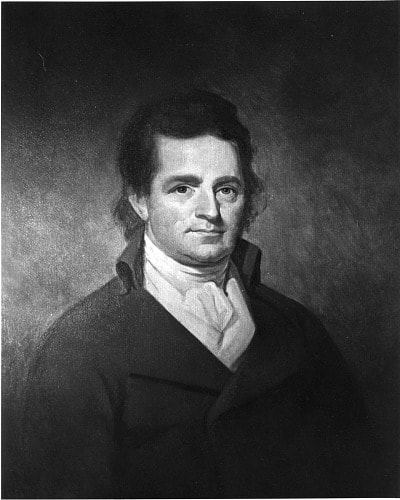

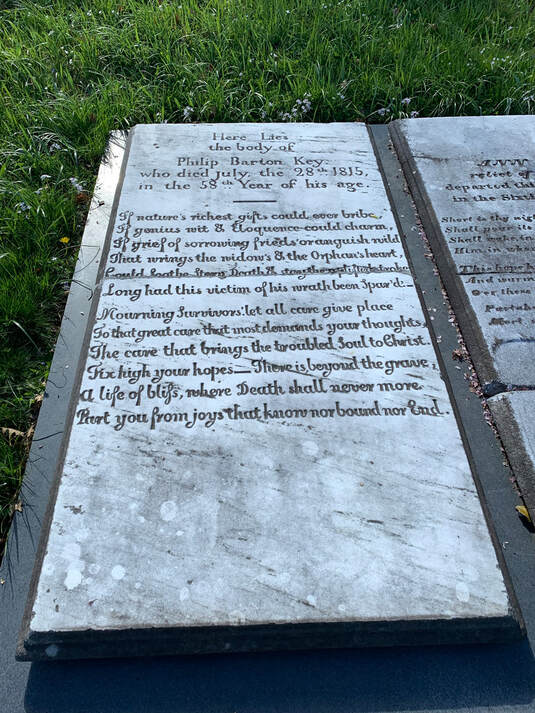

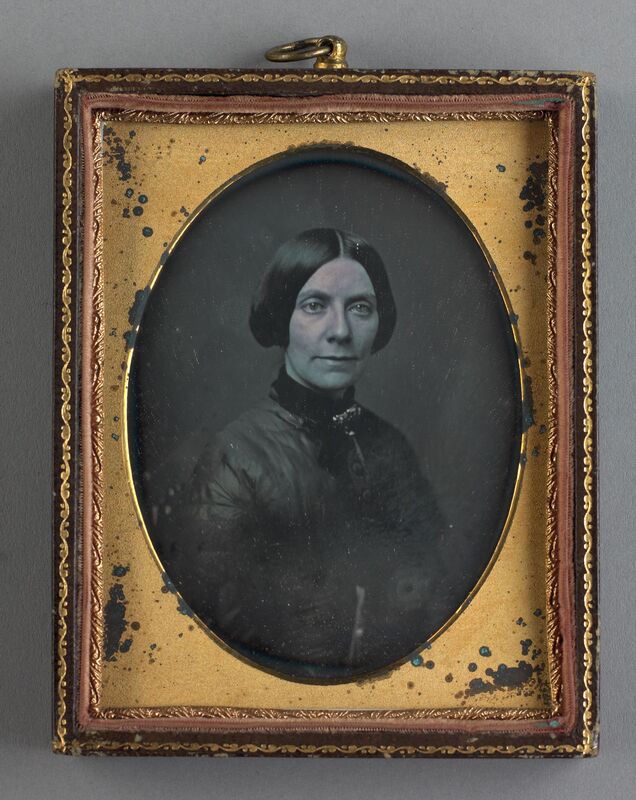

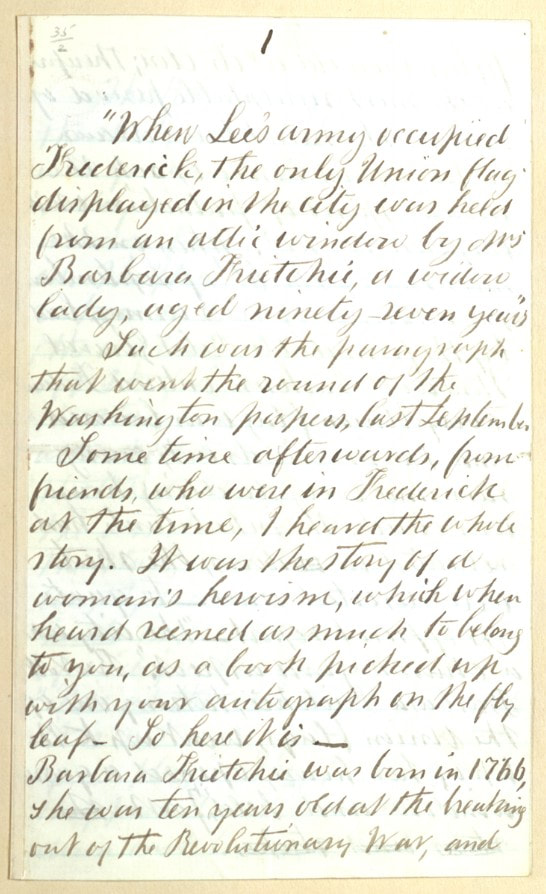

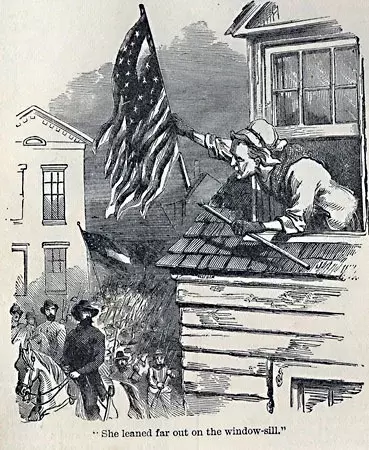

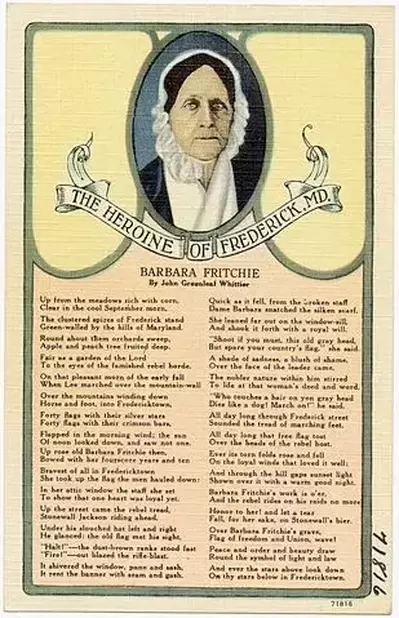

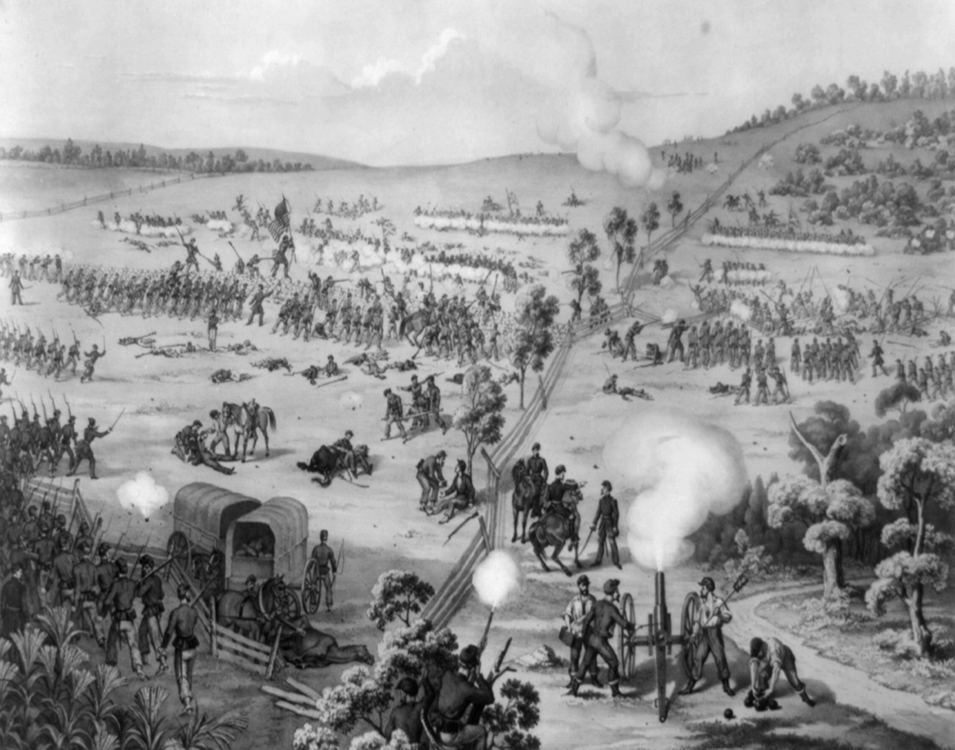

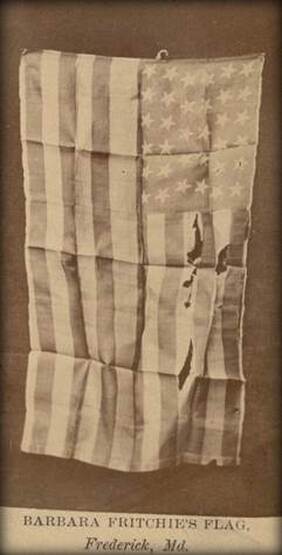

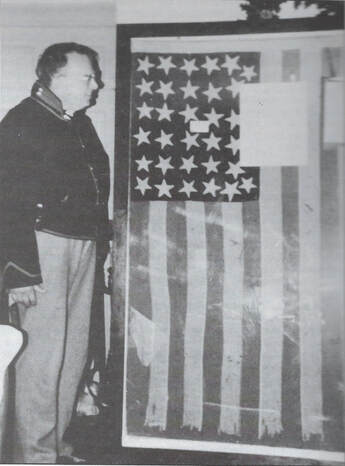

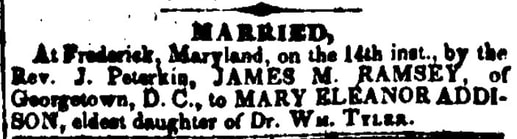

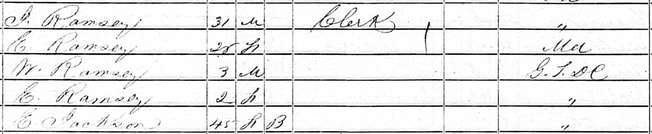

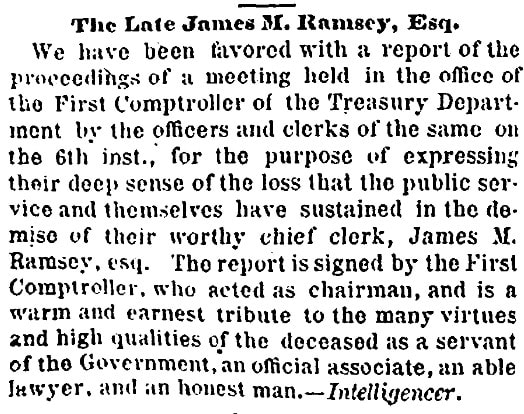

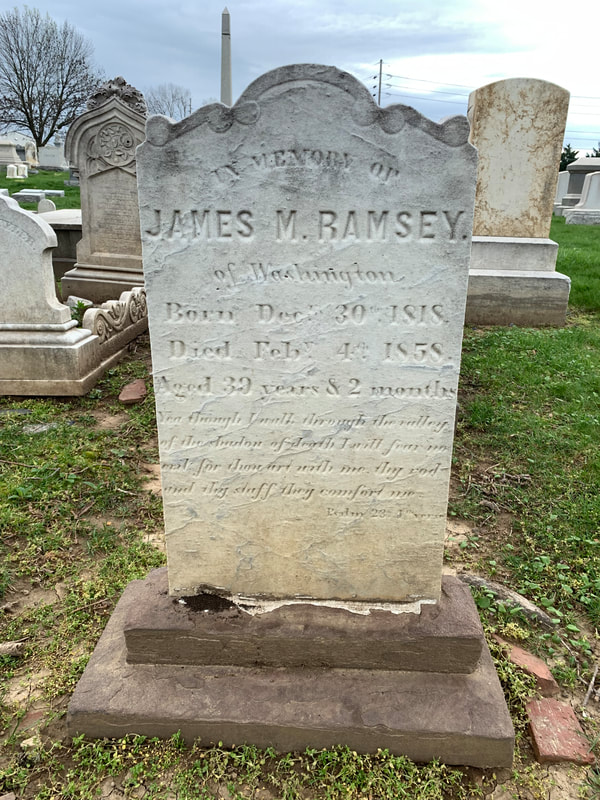

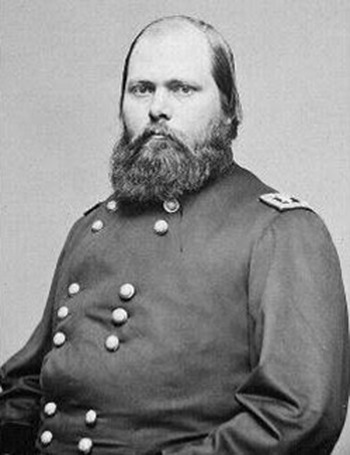

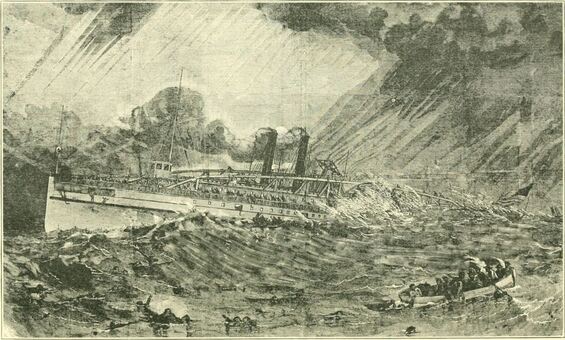

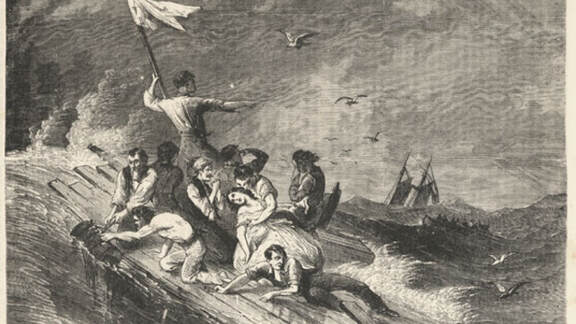

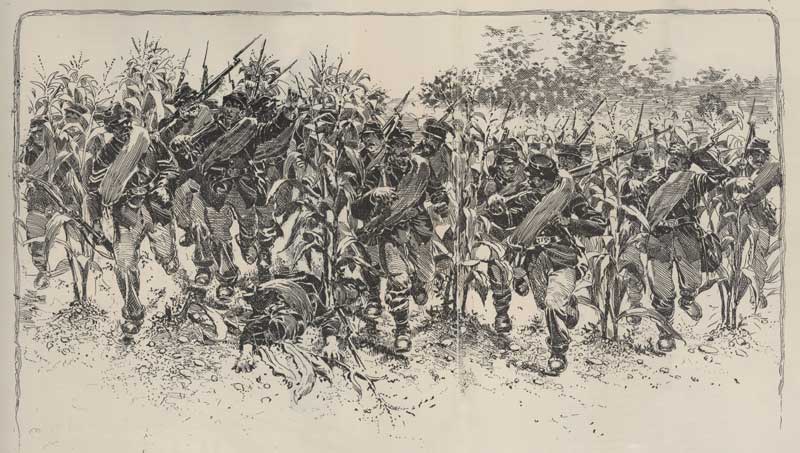

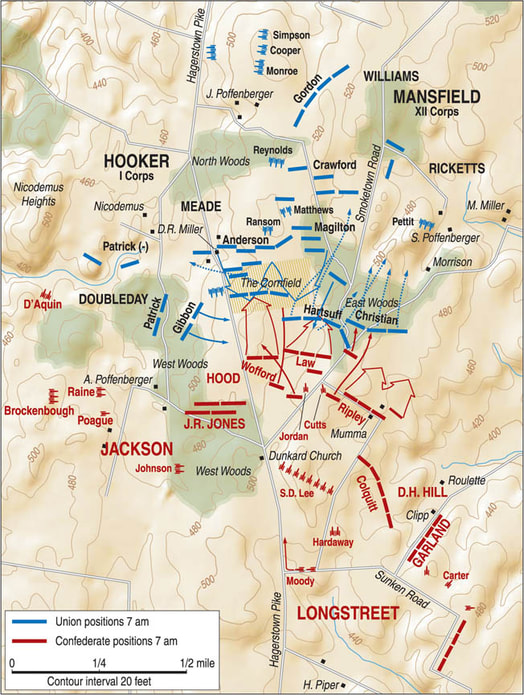

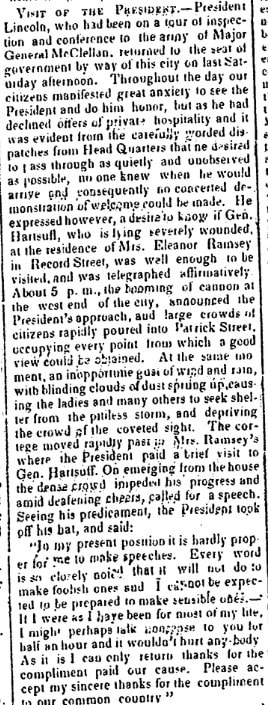

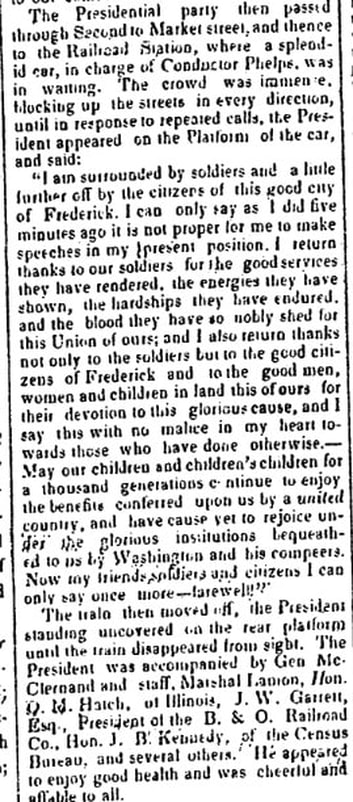

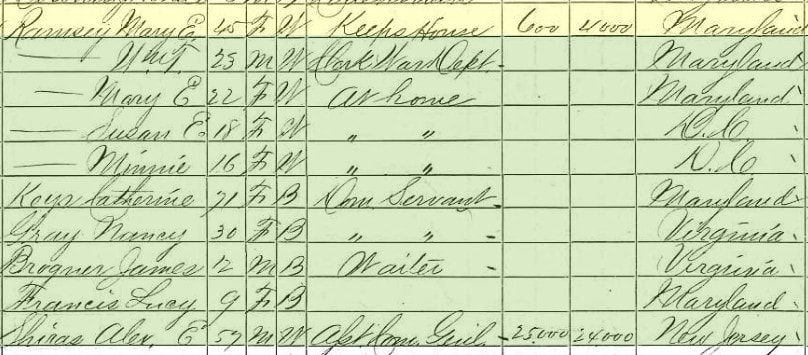

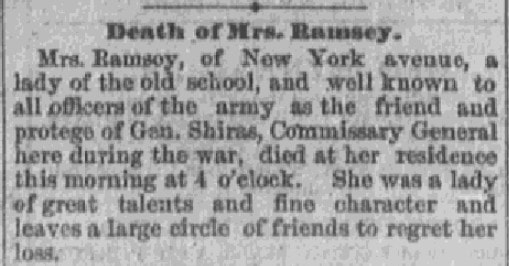

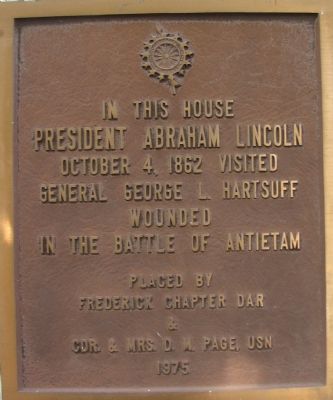

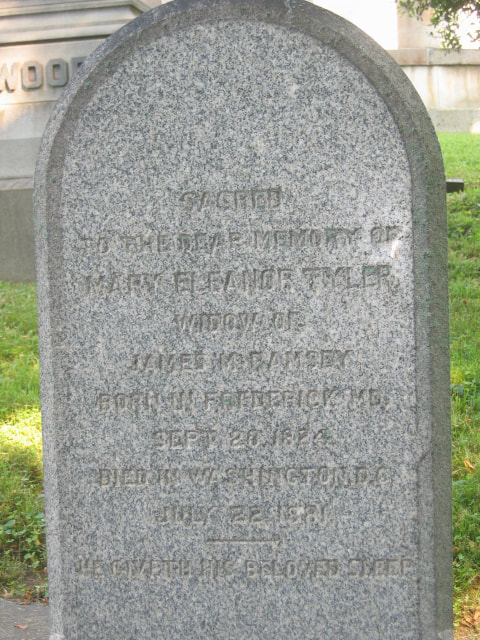

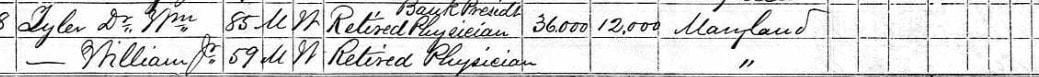

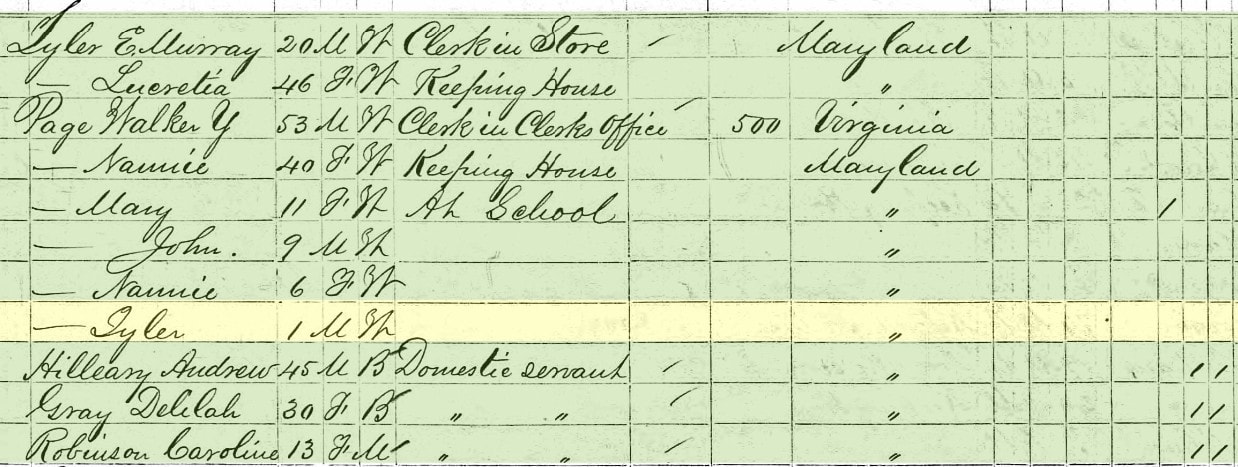

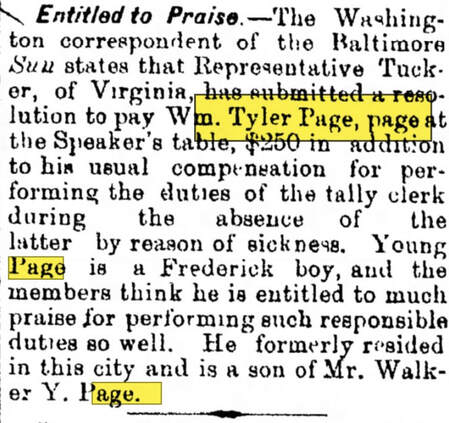

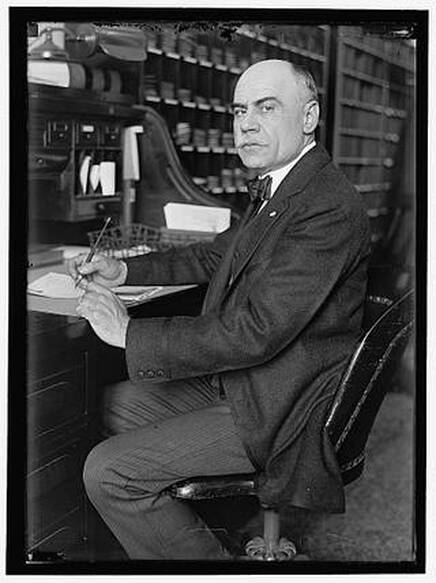

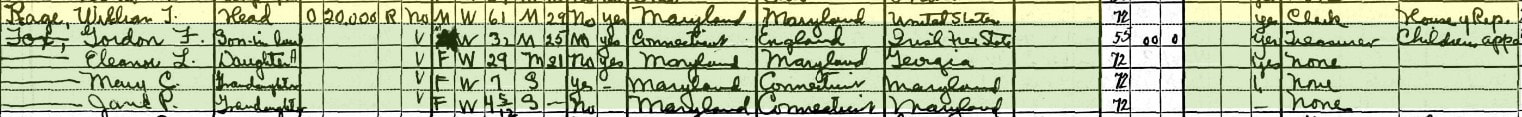

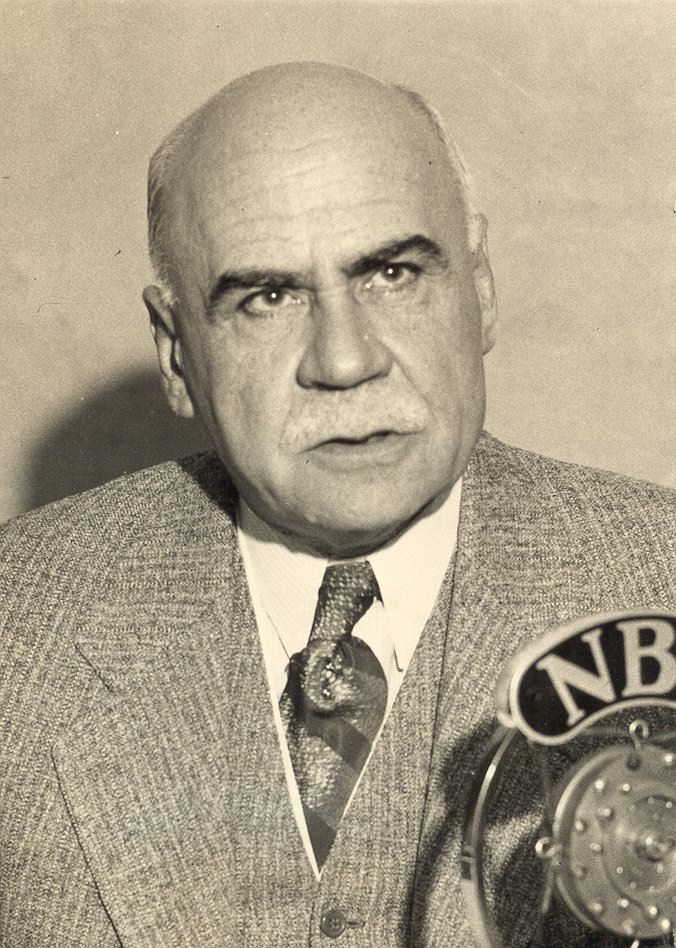

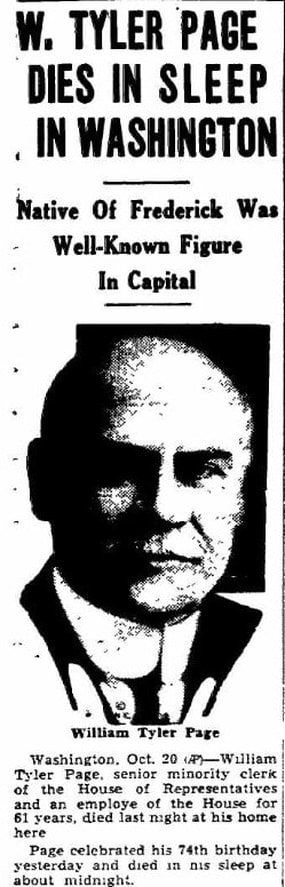

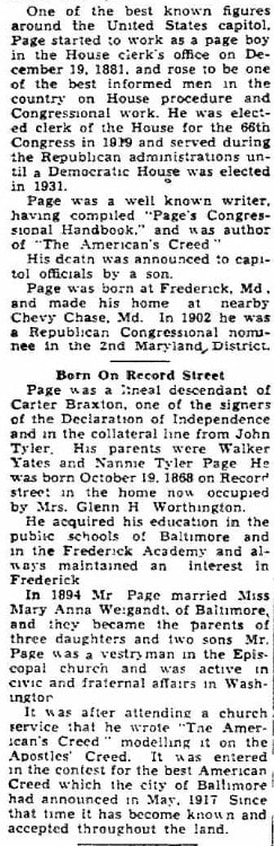

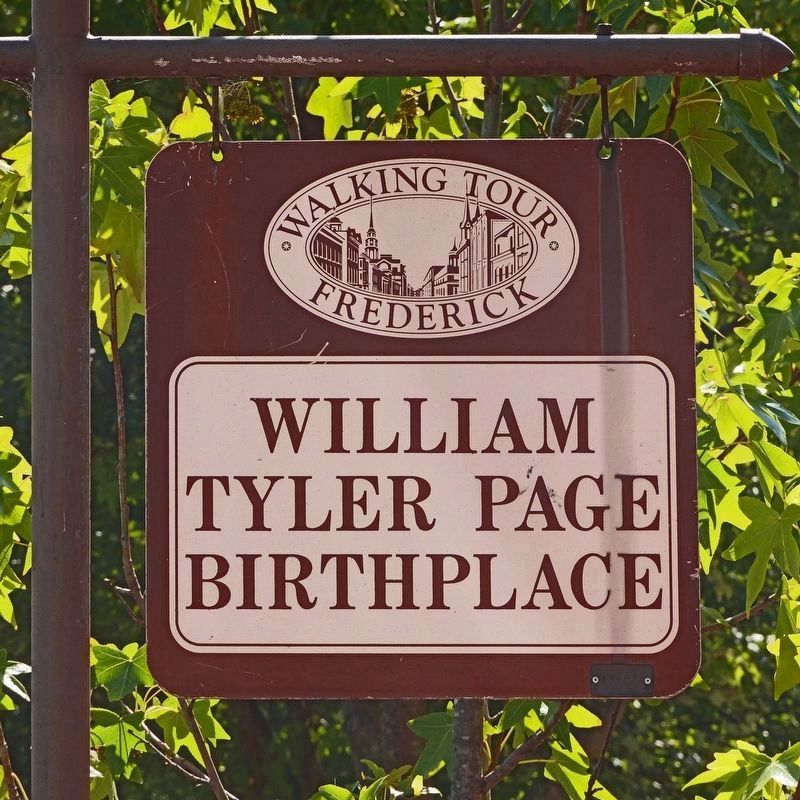

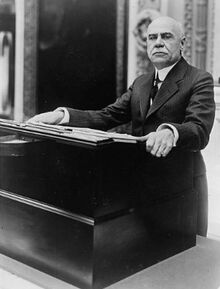

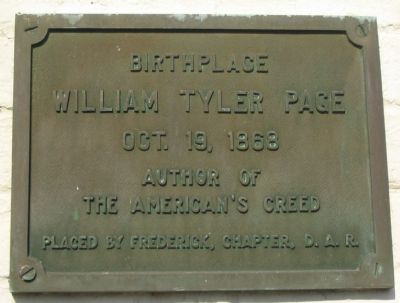

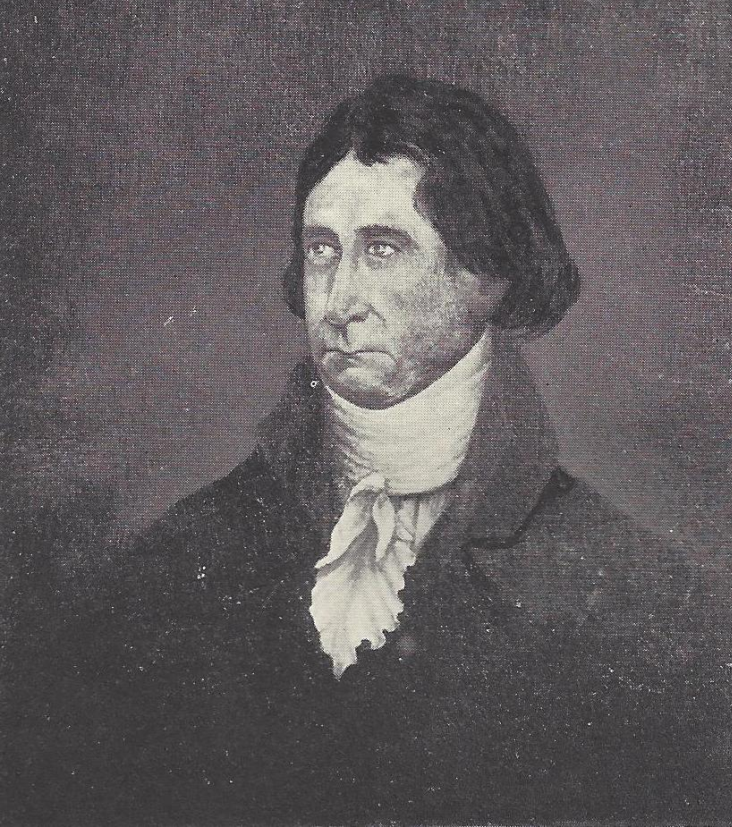

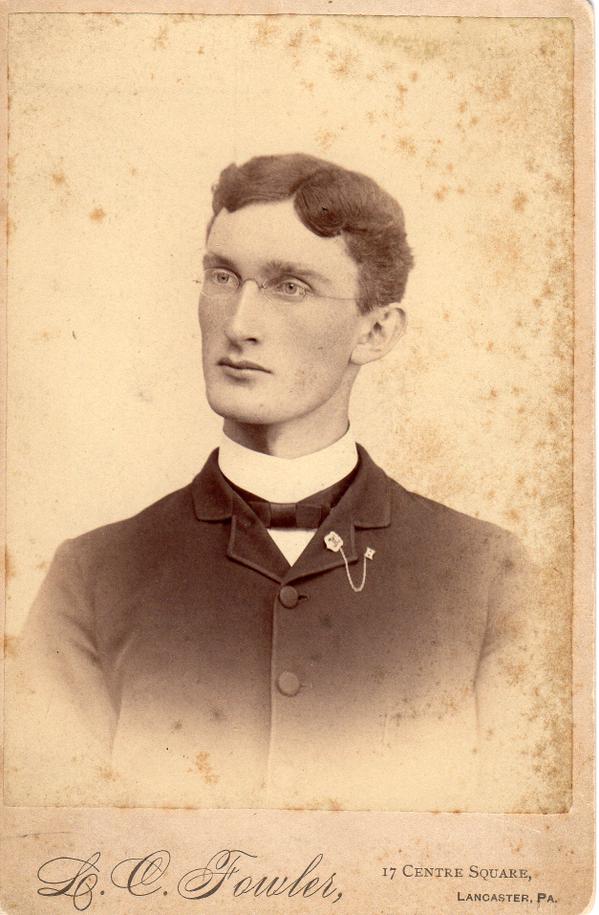

A few weeks back, I had the opportunity to visit another beautiful “garden/rural cemetery” like ours at Mount Olivet. This was Oak Hill Cemetery in Northwest Washington, DC, located at 3001 R Street next to Dumbarton Oaks Park. This area, near historic Georgetown, can be seen by travelers using the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway. And when I say this is a cemetery "like ours," I mean there are a lot of common features and elements, but just as many differences based on a natural topography affording the opportunity for more trees and private family crypts. For those unfamiliar with this brand of burying ground, here is an explanation. A garden, or rural, cemetery is a style of memorial burial ground that became popular in the United States and Europe in the mid-19th century due to the overcrowding and health concerns of urban cemeteries. They were typically built on the outskirts of major cities—far enough to distance itself from town centers, but close enough for visitation. They often contain elaborate monuments, memorials, crypts, chapel spaces and mausoleums in a tree-filled and landscaped park-like setting.  Early 1900s garden cemetery "social scene" Early 1900s garden cemetery "social scene" The garden cemetery movement mirrored changing attitudes toward death in the nineteenth century. Images of hope and immortality were popular in rural cemeteries in contrast to the puritanical pessimism depicted in earlier churchyards. Statues and memorials now included depictions of angels and cherubs as well as botanical motifs such as ivy representing memory, oak leaves for immortality, poppies for sleep and acorns for life. From their inception, “garden cemeteries” were intended as civic institutions designed for public use. Before the widespread development of public parks, the garden, or rural, cemetery provided a place for the general public to enjoy outdoor recreation amidst art and sculpture previously available only for the wealthy. The popularity of rural cemeteries decreased toward the end of the 19th century due to the high cost of maintenance, development of true public parks and perceived disorderliness of appearance due to independent ownership of family burial plots and different grave markers. Lawn cemeteries would soon become the norm. Oak Hill Cemetery was founded by Mr. William W. Corcoran, banker and founder of the Riggs National Bank, which is now known as PNC Bank today. A man of many tastes and philanthropies (e.g. the Corcoran Art Gallery), Mr. Corcoran purchased 15 acres along Rock Creek in 1848 from George Corbin Washington (a distinguished lawyer and a great-nephew of our first president) and his son Lewis W. Washington. When the Oak Hill Cemetery Company was incorporated by an Act of Congress on March 3rd, 1849, Mr. Corcoran contributed the land for the cause. Captain George F. de la Roche, a master engineer, supervised the grading, including the creation of a grand wall along Rock Creek, and the plotting. James Renwick, Jr., architect of the Smithsonian Building and the original Corcoran Gallery (now the Renwick Gallery), designed the iron gate pillars and the onsite mortuary chapel. Oak Hill calls itself "a major example of the 19th Century Romantic movement, the natural and not formal English garden, an acceptance and blending of nature rather than a geometrical imposition." Interestingly, this location was originally granted by Queen Anne and the British throne back in 1702. The recipient was Ninian Beall (1625-1717). It would later be owned by the Hammond family who built the first house that one day would serve home to Sen. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. Eventually, the Bliss family came into ownership and donated the beautiful historic home and grounds to the National Park Service. Both Dumbarton Oaks and Oak Hill were part of Maryland before they became assets of the national capital. As a matter of fact, from 1748-1776, this land was actually Frederick County! We had Frederick a much bigger county at the time of our founding in 1748. Over time, Montgomery, Washington, Garrett, Allegany and Carroll would be carved out of the original Frederick “super county.” Turnabout, however, is fair play as our land mass was originally part of Prince Georges County when Frederick Town was established in 1745 and before. But wait, just like the land, there are plenty more connections to Frederick County here, and more so, Mount Olivet Cemetery that I’d like to share with you. First off, I want to tell you of my purpose for this particular trip to Oak Hill. I was attending a cemetery walking tour sponsored by the Politics and Prose Bookstore and based on a book titled Lincoln in the Bardo. Written by George Saunders, this 2017 experimental novel is its author’s first full-length novel, and was The New York Times hardcover fiction bestseller for the week of March 5th, 2017. I was introduced to this book by a gentleman named Jerry Webster , Ph. D., who has taught numerous courses in literature for the University of Maryland and Montgomery County Public Schools. Currently, he teaches ongoing programs for Frederick Community College, but also Johns Hopkins University and Washington College in Chestertown. The novel takes place during, and after, the death of President Abraham Lincoln's son William "Willie" Wallace Lincoln and deals with the president's grief at his loss. The bulk of the novel, which takes place over the course of a single evening, is set in "the bardo"—an intermediate space between life and rebirth. The term (bardo) comes from Buddhist teachings and is a Tibetan word that translates to “gap, interval, transitional process, or in between.” In the Tibetan School of Buddhism, there are three death bardos: the painful bardo of dying, the luminous bardo of dhartma, and the karmic bardo of becoming. According to the Tibetan Book of the Dead, Afterlife Guide: “While in the bardo between life and death, the consciousness of the deceased can still apprehend words and prayers spoken on its behalf, which can help it navigate through its confusion and be reborn into a new existence that offers a greater chance of attaining enlightenment.” Lincoln in the Bardo continues to receive critical acclaim, and won the 2017 Booker Prize. Many publications later ranked it one of the best novels of its decade. The majority of the work takes place in Oak Hill Cemetery, an evocative setting, as home to the central characters of this fictional story which showcases “ghost residents” interacting with each other against the backdrop of the Lincoln family’s personal loss during the American Civil War era of the 1860s. Willie Lincoln died of typhoid fever in February 1862 at the tender age of 11. His death was a devastating blow to his parents, and cast a dark shadow over the remaining years of the Lincoln presidency. Willie’s body would be laid to rest (temporarily) in the mausoleum vault, or crypt, of William Thomas Carroll, cousin of Charles Carroll of Carrollton and clerk of the US Supreme Court. Of course, our Carrollton Manor takes its name from William Carroll’s great-grandfather, Charles Carroll the Settler who surveyed and patented his 17,000 land grant in the lower Monocacy River Valley in 1723. Abraham Lincoln actually made trips to the Carroll crypt to visit Willie’s body directly after the initial funeral ceremony and entombment. This plays out within the book. After Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Willie’ body accompanied that of his father on the funeral train bound for Springfield, Illinois and Oak Ridge Cemetery where both are buried. Well, I certainly don’t want to give anything away, but I recommend George Saunders' Lincoln in the Bardo, and you can order it from Politics & Prose Bookstore. It was a nice read, and included plenty of “cemetery color.” Best of all, Jerry Webster took the tour as well, and provided me with great insight as we drove down to DC together. I had planned to do a little more Oak Hill exploration once the formal walking tour had concluded. There are plenty of notable graves to visit ranging from the aforementioned William Corcoran to former Ohio senator and governor Salmon P. Chase. Lincoln connections include his domineering secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, and assassination conspirator Mary Surratt’s lawyer, Frederick A. Aiken (1832-1878). You may remember him if you saw the 2010 movie The Conspirator with James McAvoy playing Aiken and Robin Wright in the role of the lone female accomplice to the death of the president. More modern decedents include Madeleine Albright (first female US secretary of state)(1937-2022) and Katharine M. Graham (1917-2001) former editor and president of the Washington Post. A slew of former politicians and Union Civil War officers are buried here too. I actually did some advance work in researching a few interesting connections between specific individuals interred here in Oak Hill and others back home in Frederick at Mount Olivet. I will share five of these with you, although I’m sure many more exist. Getting back to the concept of the bardo, I wonder if their was such an experience for any of the following "souls" within either respective “garden cemetery?” In many cases, relationships or interactions actually took place between these individuals as mortals, shortly before the respective death of one, or the other. Philip Barton Key (1757-1815) Here lies the beloved uncle of Francis Scott Key—Philip Barton. Mr. Key sacrificed his inheritance to fight for a Loyalist regiment in the American Revolution and was eventually captured, paroled and sent to England, where he studied law at the Middle Temple of the Inns at Court in London. He returned to Maryland in 1785 and was one of few disgraced Tory Loyalists to resurrect his career and reputation. Admitted to the bar, he first practiced law in Leonardtown and Annapolis. In 1801, Key was appointed by President John Adams to the Fourth United States Circuit Court, and served until 1802, at which time the court was abolished by political rival Thomas Jefferson.  Former Key home in Georgetown Former Key home in Georgetown Philip Barton Key would re-locate his law business to Georgetown. He would build a mansion, calling it Woodley, on land originally owned by Ninian Beall. Today the neighborhood where the home still exists is called Woodley Park. You may know it as a Metro stop, and the home of the National Zoo. Key would eventually serve counsel to Associate Justice Samuel Chase during Chase's impeachment trial in 1805, and later became a United States Representative to Congress from Maryland, serving from 1807 to 1813. Most pivotal for our discussion, Philip Barton Key is responsible for mentoring his “soon to be famous” nephew, and beckoned him to take up residence in Georgetown, not Frederick, because this was the new home of the national capital. If Francis Scott Key had stayed in Frederick with his family and professional law career, would he have participated in trying to gain the release of Dr. William Beanes in September, 1814? Would he have had the opportunity to personally eyewitness the fierce attack on “Charm City” and Fort McHenry with her Defenders of Baltimore? Without need to write an ode to the American Flag, would this man be compelled to put pen to paper in writing what would in time become our national anthem? Great questions to ponder in the bardo or out. The elder Key died in 1815, nine months after his nephew gained eternal fame for penning the "Star-Spangled Banner." Philip Barton Key was originally buried on his nearby Woodley estate in Georgetown, but was later reinterred at Oak Hill Cemetery. Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte (E.D.E.N.) Southworth (1819-1899) The most popular American female novelist of her day, Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte Southworth was an American writer of more than 60 novels in the latter part of the 19th century. She was a supporter of social change, abolition of slavery and women's rights. In Ms. Southworth’s novels, her heroines often challenge modern perceptions of Victorian feminine domesticity by showing virtue as naturally allied to wit, adventure, and rebellion to remedy any unfortunate situation. Ms. Southworth would live in a Georgetown cottage for most of her later life. The schoolteacher turned professional writer was well acquainted with Harriet Beecher Stowe and other New England luminaires. In 1863, she would communicate an interesting event to John Greenleaf Whittier of Amesbury, Massachusetts. This fireside poet was a member of the Quaker religion and also an ardent Abolitionist. In July of 1863, Mrs. Southworth wrote two known letters to Whittier, retelling a story that she had heard second-hand. It involved a spunky senior citizen said to have taunted invading Confederate troops in her hometown of Frederick by waving her Union flag out of an upstairs window of her house located on Patrick Street, one of the principal routes through town. Southworth told Whittier that a neighbor had shared the story with her, and upon hearing it, knew it was “specifically made for Whittier’s pen.” In response, Whittier wrote: “I heartily thank thee for thy kind letter and its enclosed message. It ought to have fallen into better hands, but I have just written out a little ballad of “Barbara Frietchie,” which will appear in the next “Atlantic.” If it is good for anything thee deserve all the credit of it.” Whittier’s poem would be published in the Atlantic Monthly Magazine’s October, 1863 edition. The rest, as they say, is history. This Union propaganda “hit piece” on Gen. Jackson and the Southern Army was fast-tracked into the New England-based publication of literary and cultural and nature (Atlantic Monthly), while simultaneously making Frederick’s Barbara Fritchie into the definitive female heroine of the American Civil War. Much like Francis Scott Key in the War of 1812, Barbara Fritchie quickly became a household name by the end of the American Civil War. I had the opportunity to personally peruse Southworth’s 1863 letters to Whittier. They reside in the collection of the Friends Historical Library Reading Room of Swarthmore College outside Philadelphia. While conducting additional research (about 15 years ago), I found that Ms. Southworth was friends with a real estate broker named Cornelius Stille Ramsburg (1839-1915). This Frederick export was the gentleman who originally told Southworth the flag-waving story of Barbara Fritchie during the Maryland Campaign of fall, 1862. He apparently heard it while visiting his hometown on the tail-end of his honeymoon trip of the Northeast. Mr. Ramsburg was a relative of the Fritchie family, and supposedly heard tall tales of Barbara’s bravery at the funeral of his great aunt, here in Frederick. Speaking of funerals, Mr. Ramsburg was here in Oak Hill on the occasion of E.D.E.N Southworth’s funeral in early July, 1899, and performed duties as one of the decedent’s pall bearers. Later, Cornelius Ramsburg would take his everlasting place here as a permanent resident himself. Cornelius S. Ramsburg occupies an unmarked grave in a plot containing other unmarked family members. If it had not been for Mr. Ramsburg and Mrs. Southworth, Mount Olivet would not have this memorial to Barbara Fritchie placed in 1913. They are to blame for her posthumous fame. The validity of the Fritchie “flag-waving” legend has been challenged ever since it first went into print in fall, 1863. Spoiler Alert: It is highly doubtful that Barbara waved the flag at the Rebel Army and, more so, generals Jackson and Lee on September 10th, 1862. However, it is known that the following days could have featured Barbara waving a Union flag in support of Gen. McClellan and the pursuing Union Army. One account specifically mentions a rising military star who would unfortunately become an interred member of Oak Hill before his rightful time. This Union officer from Wheeling, Virginia (later West Virginia) had become the division commander of the Union Army’s IX Corps before the famed Maryland Campaign of 1862. This was Maj. Gen. Jesse Reno. Jesse Reno (1823-1862) Jesse Lee Reno was a career US Army officer who served in the Mexican–American War, the Utah War, the western frontier, and finally as a Union General during the Civil War. Known as a "soldier's soldier" who fought alongside his men, Gen. Reno had recently opposed his former West Point classmate and friend, Stonewall Jackson, during the Second Battle of Manassas (or Bull Run) just over three weeks earlier. It’s ironic that both of these men, Reno and Jackson, are alleged to have had poignant conversations with Frederick’s famous nonagenarian, Ms. Fritchie, in September, 1862. It has been reported that Reno actually spent time with the patriotic maven just a two days removed from her alleged “wrangling” with Gen. Jackson. When passing through town on the 12th, Reno and his brother are said to have encountered Barbara waving her flag in front of her home on West Patrick Street. The Union Army was heading west after the Confederates on the National Road. While seeing Barbara holding her flag on the south side of the street, and Rev. Joseph Trapnell, a resident also in his 90s on the north side directly across from Barbara, he is said to have cheerfully called out to his soldiers: “Behold the Spirit of ’76!” He then told his brother Frank that the aged civilian reminded him of his deceased mother. With that, the Renos apparently stopped to visit with Barbara at her house by Carroll Creek. Barbara is said to have given the officer currant wine, along with supplying an opportunity to write a letter home from her family desk. As a parting gift, Dame Fritchie would present Reno with a flag, perhaps the one she supposedly waved at Jackson the previous day. Ironically, it would be this flag that would accompany Reno’s dead body on its trip home to Massachusetts for proper burial a few days later. Gen. Jesse Reno died atop South Mountain on September 14th, 1862 while leading his men against Rebel forces in the vicinity of the Wise Farm at Fox’s Gap. This was the result of a sharpshooter’s bullet as Reno was surveying the field prior to twilight after a long day of battle. Jesse Reno’s funeral would be held at Boston’s Trinity Chapel. The Fritchie flag is said to have draped his casket. His body was placed in a vault in the church with the intent of reinterring it at some future date. Reno’s widow eventually moved back to her hometown of Washington, DC at the end of the war and purchased a large circular burial plot in Oak Hill Cemetery. She chose a centrally located knoll that commanded a view in all directions. On April 9th, 1867, Jesse Reno was placed here under a memorial in the form of a draped shaft. Three days later, Mary Cross Reno had three children, who had all died in youth, reinterred in this plot with their father. Mary is said to have kept her husband’s uniform, sword and the Barbara Fritchie flag in an army chest. She would join them upon her death in 1880. The year prior to Mary Reno’s death, the pro-Union Society of the Burnside Expedition and IX Army Corps dedicated a monument atop Fox’s Gap on South Mountain to the memory of Gen. Jesse L. Reno. This occurred on September 14th, 1889. The monument is said to mark the location where the prominent Union commander was felled on that fateful day of September 14th, 1862. As a reminder, we still have the aptly named Reno Monument Road atop the mountain. The 39-year-old Gen. Reno is remembered by the naming of “Reno County, Kansas,” “El Reno, Oklahoma,” “Reno, Nevada,” “Reno, Pennsylvania” and Fort Reno in Washington, D.C. after him. By January 1863, the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) had begun laying tracks east from Sacramento, California, eventually connecting with the Union Pacific Railroad at Promontory, Utah, to form the First Transcontinental Railroad. Land was deeded to the CPRR in exchange for its promise to build a depot at a place called Lake's Crossing. Once the railroad station was established, the town of Reno officially came into being on May 9th, 1868. CPRR construction superintendent Charles Crocker named the community after Major General Jesse Lee Reno, the Union officer killed in the American Civil War at the Battle of South Mountain. The flag would be handed down to descendants of the family and was at Fox’s Gap for the 100th anniversary of the general’s death in September, 1979. Mary Eleanor Addison Tyler (1824-1881) The former Mary Eleanor Addison Tyler was the daughter of Dr. William Tyler and wife Mary Belt Addison. Dr. Tyler (1784-1872) lived at the intersection of Record and Counsel streets and was a prominent physician in Frederick. He was heavily involved in local and state politics, and is best remembered for his work in banking—as a founder and the first president of the Farmers and Mechanics National Bank, a branch of the Westminster Bank. F&M was founded in 1817 and chartered in 1823 as a separate bank. Tyler would serve the bank for 54 years up through his death in 1872. Eleanor, or “Nellie” as she was also referred to, was born September 20th, 1824 and grew up in Courthouse Square in Frederick. She still lived in the family home when the Tylers experienced a terrible fire in 1842 that would become the subject of a well-known local art-piece by itinerant Frederick painter John J. Markell. Four years later, Eleanor would marry James Murphy Ramsey of Georgetown on April 14th, 1846. They went on to have six children. The family lived in Northwest D.C. as James Ramsey, Sr. worked as the chief clerk for the First Controller’s Office of the federal government. Sadly, Eleanor’s two youngest children would not reach maturity as Alex Shiras Ramsey (b. 1856) died in 1857, and James Murphy Ramsey, Jr. (b. 1857) died in 1860. In between these losses, Mrs. Ramsey would experience the death of her husband, James. All three are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area B. The widowed Mrs. Ramsey can be found living in Washington in the 1860 census on the eve of the American Civil War. However, she would re-locate to what was thought to be a safer environment during the war, itself, as the Union capital was thought to be a prime target for a Confederate attack. Mary Eleanor came back to her hometown of Frederick and resided in a commodious dwelling (likely owned by her father) just a few doors north of her childhood home. Mrs. Ramsey would earn a degree of “historical fame” during the Civil War. She didn’t wave a flag like Frederick’s Barbara Fritchie or Mary Quantrill, but she did care for a prominent convalescing military officer in the fall of 1862. In doing so, she would briefly play host to that unique grieving visitor to Oak Hill Cemetery I mentioned earlier—Abraham Lincoln. Three days after the Battle of South Mountain, the conflict responsible for the death of Gen. Jesse Reno at Fox’s Gap near Boonsboro, another Union general would be shot in the early morning action in David Miller’s cornfield during the Battle of Antietam in nearby Sharpsburg, Maryland. This man would be much more fortunate than Reno, as he would survive from his wounds—and some of that credit should be given to Mrs. Ramsey. The patient was Gen. George Lucas Hartsuff, one of the luckiest “unluckiest” guys to wear the uniform. George Hartsuff (b. 1830) spent the first twelve years of his life in the small western New York village of Tyre, in Seneca County before moving with his family to Livingston County, Michigan, in 1842. He received an appointment to West Point six years later, graduating in 1852 and ranked nineteenth in a class of forty-three. Two slots behind him, ranked 21st was Ulysses S. Grant. Upon graduation, Gen. Hartsuff was commissioned a second lieutenant by brevet in the 4th U.S. Artillery and assigned to frontier duty in Texas where the young officer fell seriously ill with yellow fever. In 1855, after recovering from his sickness, he was sent to Fort Myers, Florida. Given command of a surveying expedition in December of that year, George Hartsuff led ten soldiers into Seminole Territory near the Big Cypress Swamp. During a fight with Seminole Indians, Hartsuff was wounded three times. The most serious injury was a musket ball buried deep in his chest. The officer told the surviving members of his party to save themselves and then sought shelter. Stumbling through the forest, he fell into a pond. Neck-deep in water and suffering from his two wounds, Hartsuff had a difficult time getting out but was eventually able to do so. Without food or fresh water, the soldier laid on his back for three days before being rescued by American troops sent out from Fort Myers. Doctors cared for Hartsuff but were unable to remove the bullet that entered his left breast and struck his lung. He would recover and rejoin his men less than two months later. Having sufficiently recovered from his wounds, George Hartsuff, by this time a first lieutenant, was appointed as an instructor of artillery and infantry tactics at West Point in 1856, and held this position for three years. His next assignment was to the frontier post of Fort Mackinac, Michigan. With misfortune seemingly his lot, Hartsuff was on board the steamship Lady Elgin on the storm-tossed night of September 8th, 1860, as the boat made its way across Lake Michigan traveling between Chicago and Milwaukee. With visibility poor and the waters rough and restless, the Lady Elgin was struck by the schooner Augusta. A total 373 passengers of the Lady Elgin were lost as the steamer sank. Lt. Hartsuff was one of the 155 survivors. On March 22nd, 1861, George Hartsuff was appointed assistant adjutant general with the brevet rank of captain and was assigned to duty under Rosecrans in West Virginia. He held under staff positions, eventually serving briefly as chief of staff of the Mountain Department. Hartsuff became a brigadier general on April 15th, 1862. He served in third corps Army of Virginia and then in the Army of the Potomac. Gen. Hartsuff was severely wounded in the hip at Antietam while leading a brigade in second division I Corps at “the infamous Cornfield.” Reports vary as to whether Hartsuff was felled by a sniper’s bullet or shell fragment. He tried to remain in the saddle, but he soon grew faint and had to be helped off his mount. Carried off the field, Hartsuff was taken to a nearby home where a doctor examined his wound. All efforts by him and other doctors later in the day to locate a bullet were unsuccessful and they surmised that the bullet had come to a stop deep within the pelvic cavity. Hartsuff recovered from his “Antietam inflicted” wounds here in Frederick at the house of Mrs. Eleanor Ramsey on Record Street in Frederick. A few weeks later, Gen. Hartsuff was visited by an old friend in President Abraham Lincoln. This occurred on October 4th, 1862. His full recuperation would take eight months. The Frederick Examiner of October 8th, 1862 explains the visit by Willie Lincoln’s father. By war’s end, Gen. Hartsuff was a major general, commanding all the Union forces on Bermuda Hundred. Following Gen. Lee’s evacuation of Petersburg, (VA), Hartsuff made his headquarters at Center Hill, Virginia. He was visited here by Abraham Lincoln on April 7th, 1865—just eight days before the president’s dramatic death. After the Civil War, ill health would keep George Hartsuff in office jobs in Washington, DC through the remainder of his military career. He resigned in 1871 due to intense pain and moved to New York City. Early in May 1874, he developed a cold that quickly developed into pneumonia. He was dead just one week later, passing away on May 16th, two weeks shy of his forty-fourth birthday. His remains were taken to West Point for burial. An autopsy revealed that Hartsuff’s pneumonia was caused by the infection on a scar on his left lung. The scar was itself caused by the wound he received nineteen years earlier battling Seminoles in the swamps of Florida. Remarkably, neither this bullet nor the one that entered his hip at Antietam were ever located. As for our subject, Mrs. Eleanor Ramsey, she returned to Georgetown after the war where she resided at 1341 Q Street, Northwest by the intersection with 14th Street. She would die on July 22nd, 1881 and was buried in nearby Oak Hill, instead of Mount Olivet with her husband. Two daughters would eventually join her in Oak Hill (at the location of Van Ness/Lot 240 East). These were Minnie (Ramsey) Bradenbaugh (1855-1884) and Susan Elizabeth (Ramsey) Gassway (1851-1926). Today, a plaque and visitor trail sign can be found marking the home where she cared for George Hartsuff, and welcomed President Lincoln in early October of 1862. William Tyler Page(1868-1942) My final grave “haunt” to find on this particular day at Oak Hill was that of Mrs. Ramsey’s nephew, William Tyler Page. He was the son of her sister Anna Christiana “Nannie” Tyler. Nannie Tyler married Walker Yates Page of Virginia, a direct descendant of Carter Braxton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. The couple went on to have five children. Interestingly, two of these were conceived during the American Civil War period, which is surprising as Mr. Page fought for the Southern Cause of his native state as a member of Mead’s Confederate Cavalry, Company K. The youngest of the Page children was born well after the war on October 19th, 1868. This was William Tyler Page, named for his physician/bank president grandfather. William Tyler Page attended schools in Frederick and in Baltimore as the family relocated to that place in 1885. His mother died in 1888 and was brought back to Frederick for burial in Mount Olivet. His father would be buried here too upon his death in 1903, but in an unmarked grave. A marker would finally be placed over him in 2017 by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. William Tyler Page was appointed a Congressional "page," ironic as it sounds, in the House of Representatives at a young age. He then served as a clerk of the House of Representatives and would spend 50 years working for the federal government. In May 1917, during World War I, Baltimore’s Mayor James Harry Preston announced that a contest would be held to find the best American’s creed. The mayor offered a prize of $1,000. Our subject received divine intervention while walking home from church on a particular Sunday. He would put pen to paper and submitted an entry. Meanwhile, other offerings came from every state in the Union. The award committee picked an entry that was less than 100 words. This was the one written by Frederick native William Tyler Page. On April 3rd, 1918, the House of Representatives accepted Page’s paper as the American Creed on behalf of the American people. It reads as follows: “I believe in the United States of America as a government of the people, by the people; whose just powers are derived from the consent of the governed; a democracy in a republic; a sovereign nation of many sovereign states; a perfect union, one and inseparable; established upon those principles of freedom, equality, justice, and humanity for which American Patriots sacrificed their lives and fortunes. I therefore believe it is my duty to my country to live it; to support its Constitution; to obey its laws; to respect its flag; and to defend it against all enemies.” William Tyler Page is said to have used the money from the award to purchase a liberty bond. He lived the following 25 years of his life as a pseudo celebrity while residing at 220 Wooton Avenue in Friendship Heights in Bethesda. Mr. Page died at the age of 74 on October 20th, 1942. He died peacefully in his sleep, after celebrating his birthday just hours before on the evening of the 19th. Instead of being brought back to Frederick to be buried on his parent’s funeral plot in area B/Lot 120, he would be buried not far from his Aunt Nellie Ramsey in Oak Hill’s Amphitheater section/lot 635 East. His wife Mary Addison (Weigandt) Page (1865-1929) had already been laid to rest here 13 years earlier next to a daughter Catharine L’Hommedieu Page who died at age 6 in 1910. Just like that of his aunt's temporary home down the street, William Tyler Page's birthplace on Frederick's Record Street is marked with a plaque and trail sign. Frederick's links to patriotism and connections to Oak Hill are boundless, spanning the War of 1812 to the Civil War and up to Mr. Page's contribution for World War I. He even has an elementary school named in his honor in Silver Spring (MD). What a fabulous cemetery to visit, filled with plenty of history and historical figures. Best of all, for me, I was able to gain a greater appreciation for our Frederick history and that of Mount Olivet Cemetery thanks to some of those individuals interred in this beautiful garden cemetery located in Northwest DC above meandering Rock Creek. I look forward to a return trip, as I have more Frederick connections to make. ATTENTION LOCAL FREDERICK HISTORY FANS! Learn history from this author with two cemetery separate tours coming up over the next month. "Frederick History 101" walking tours in Mount Olivet will feature two different versions and two date opportunities to take each: "Early history 1700s/1800s" (Sat, May 4th @10am or Tues, May 21st @6pm) "1900s -Current Day" (Tues, May 7th@ 6pm &or Sun, June 2nd @1pm) $20 for each of these 2+hour tours. Learn more below!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed