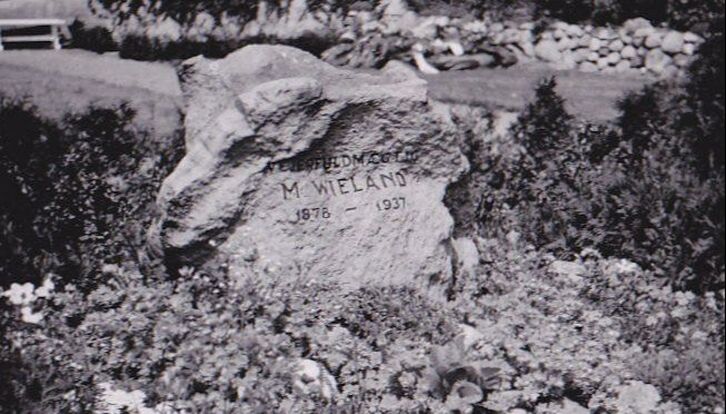

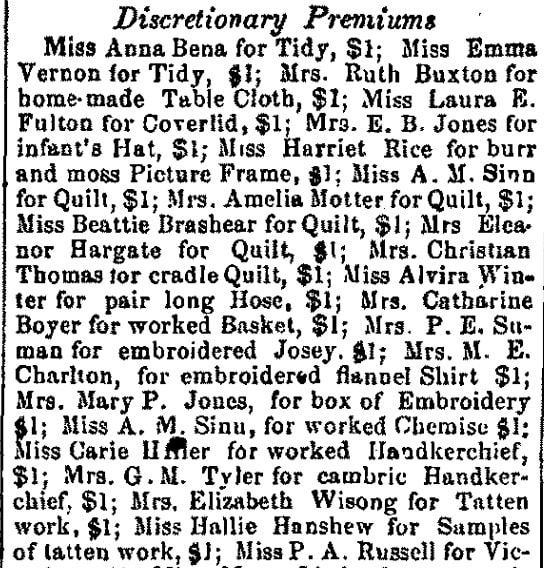

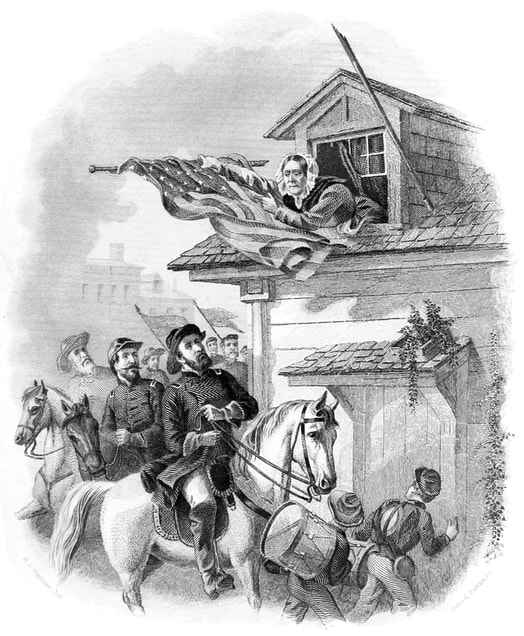

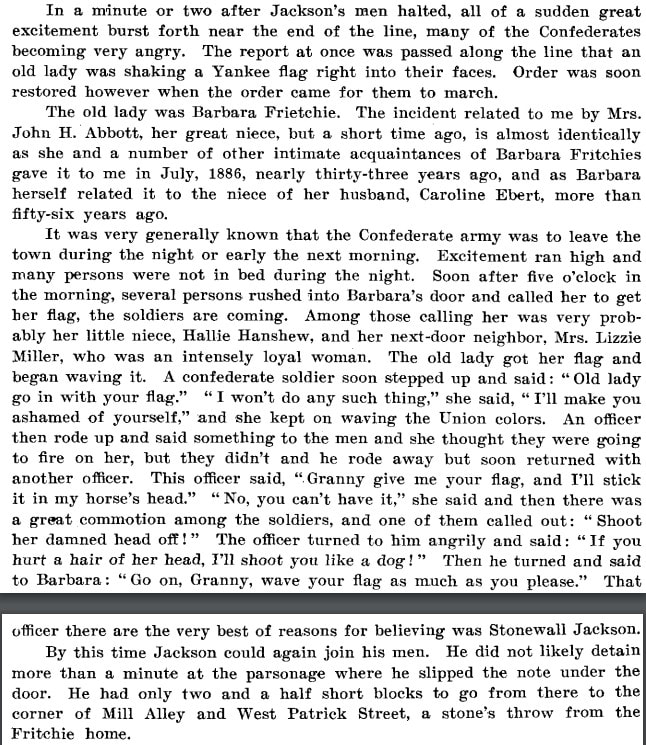

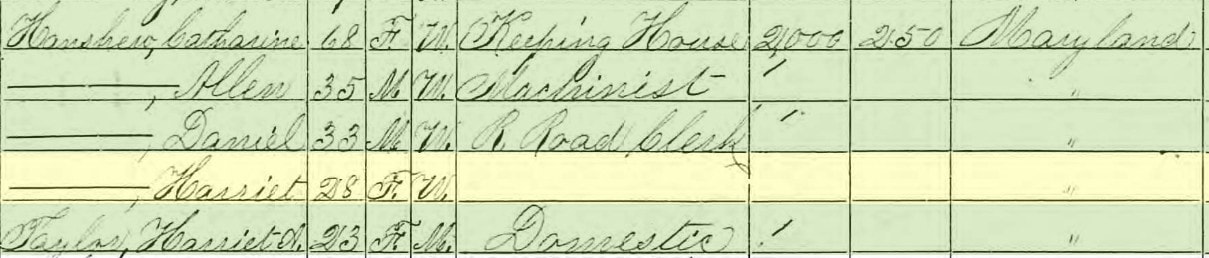

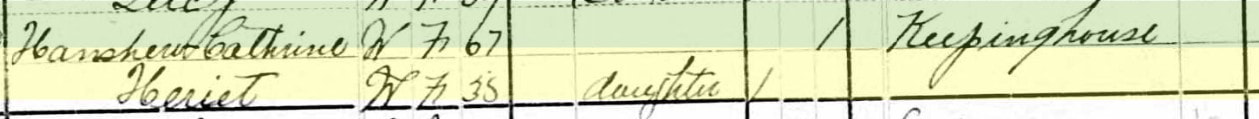

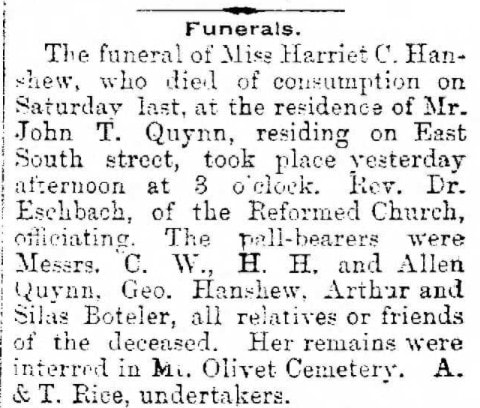

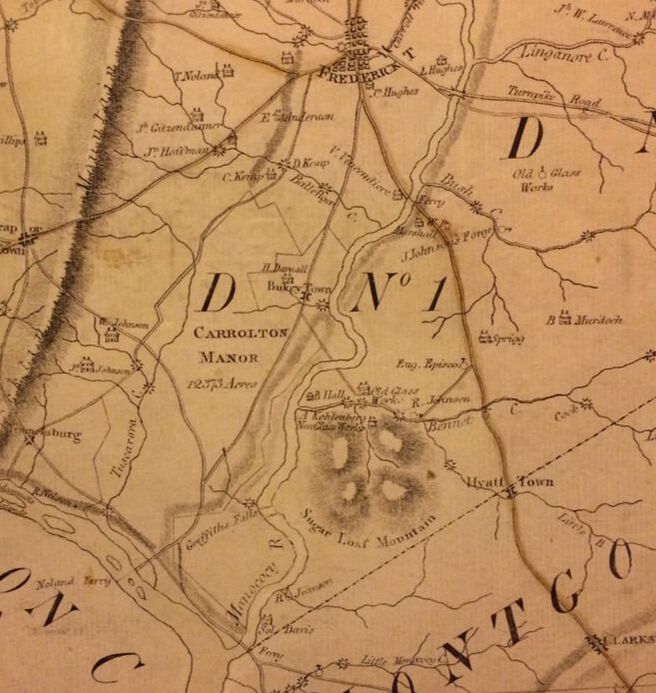

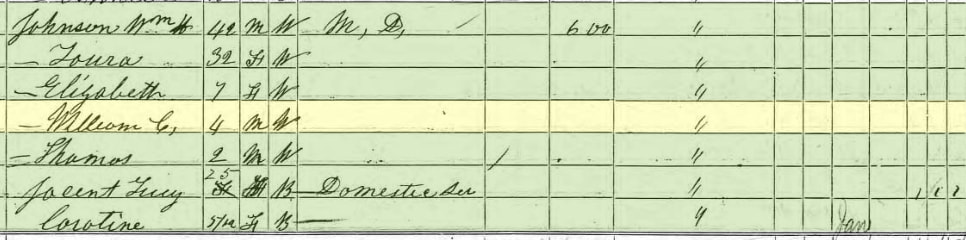

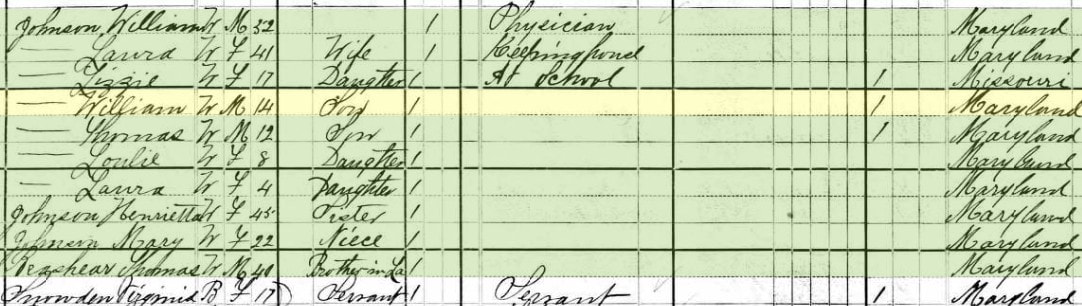

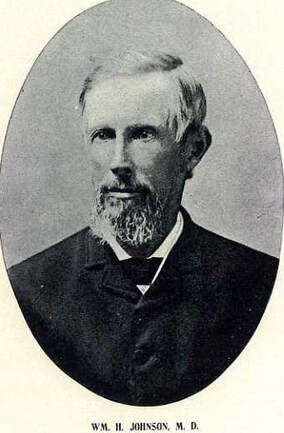

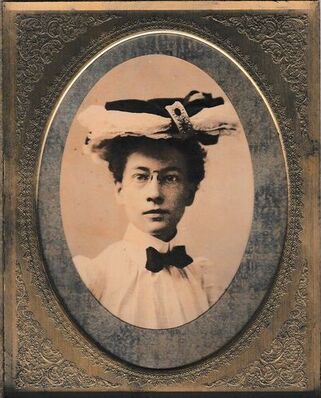

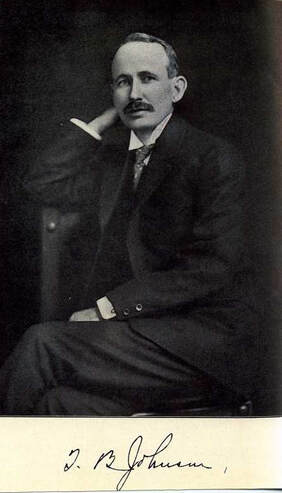

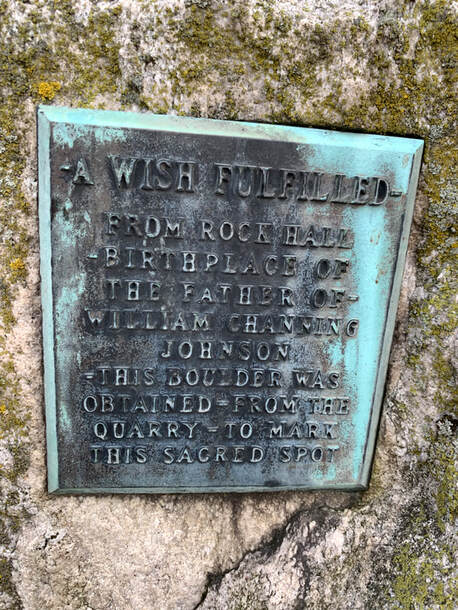

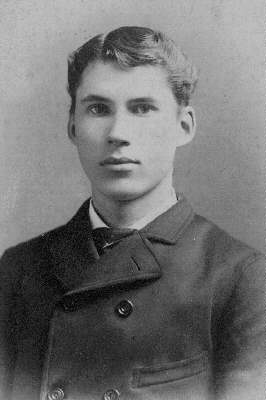

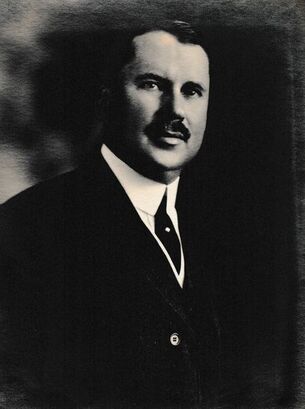

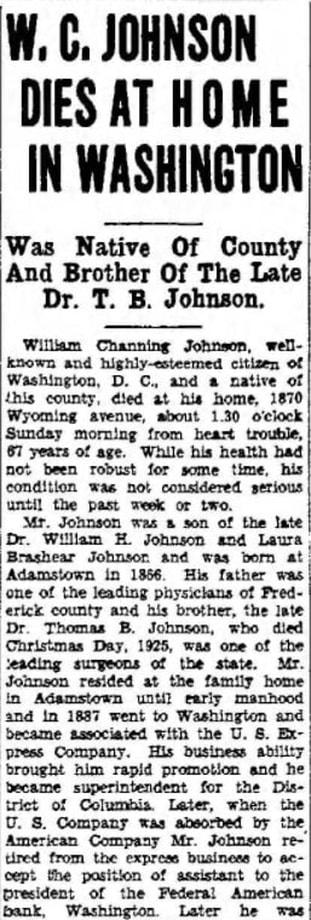

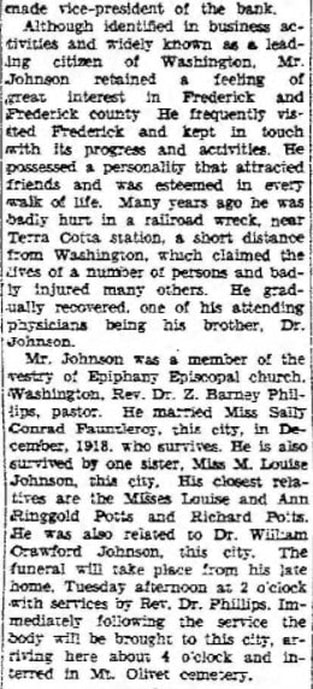

As one of the most risqué titles in my five plus years of writing this humble “Stories in Stone” blog, I can assure you that this week’s offering has nothing to do with Indiana-born, singer-songwriter John Cougar Mellencamp. I simply took poetic license from a song featured on this Rock and Roll Hall of Famer’s eighth album entitled Scarecrow—released in the waning months of my senior year of high school (1985). You may recall Mellencamp’s catchy salute to 1960’s music with “R.O.C.K in the U.S.A.,” the third single from the fore-mentioned Scarecrow which reached #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. It followed two other Top 10 songs previously released from the same album in “Lonely Ol’ Night” and “Small Town.” Where did the last 37 years go, as it truly seems like only yesterday, right? Gravestones come in all shapes and sizes. While some take the shape of the standard rectangle, others have been crafted into ornate obelisks, crosses and beautiful angels placed upon pedestals. This is a far cry from early, or more primitive grave markers still found in family farm burying grounds and remote places once considered on the frontier of American civilization. Here, rocks and boulders were used to memorialize the decedent. Of course, one can find this with surviving graves of native aboriginal peoples and former slaves of the Colonial period. There are over 40,000 monuments and markers here in Frederick’s historic Mount Olivet. Interestingly, I know of at least two instances in our cemetery where we have large boulders marking gravesites in lieu of traditional tombstones and fancy works carved in marble or granite. Although rustic in appearance, both of these examples are just as artistic and meaningful in their purpose of memorializing their respective decedents. The first of these can be found in Area E, one of the oldest and most prestigious sections of the cemetery as it constitutes the eastern slope of “Cemetery Hill.” Of course, the symbolic and spiritual aspect of graves facing eastward added to the popularity of this locale, especially at a time long before Costco and the truck stop that predated it. You could view from this vantage point a scenic and pastoral landscape, boasting a rolling countryside south of Frederick Town and dotted with farms and forests surrounding the old Georgetown Turnpike. In time, of course, would come intersecting superhighways in the form of I-70 and I-270, sparking the grand commercialization of Evergreen Point. While beggars can’t, or shouldn’t, be choosy, the baseball field complex (and adjoining parking lot) is a favorable neighbor here as it could be a shopping plaza or the highway itself. Thankfully when these lots were first bought, utilized and visited by immediate family members and those of the next few generations, the location afforded a greater sense of peace and tranquility, but such is growth and progress. A salute to the atmosphere of the 1860s instead of the 1960s as John Mellencamp’s song memorialized. A collection of prominent early Frederick families are buried here in Area E with names such as Ross, Worthington, Goldsborough, Johnson, Brengle and Tyler. You’ll also find former subjects of this blog in the personages Margaret School Hood, Elihu Rockwell, Peter Mantz and Dr. Charles McCurdy Mathias. A reminder of earlier times of our “Garden Cemetery” roots, comes with an odd and eye-catching monument found on grave #4 within Area E’s Lot 102. The mortal remains of one Harriet Catherine Hanshew were placed here on October 29th, 1883. What grabs attention the most with this large boulder is the puzzling, yet dutifully carved, identification on its face—“Hallie.” I would come to learn that “Hallie” was Harriet Hanshew’s nickname, although it doesn’t appear as so in her obituary or in census records. I did, however, finally find it within a list of fair premiums connected to the 1860 Frederick County Agricultural Exposition. Outside of Academy-Award winning actress Halle Berry, I was unfamiliar with this name and the different spelling utilized upon this rock. This prompted me so to do a little research. On a website entitled ohbabynames.com, I found the following etymology regarding the name Hallie: “Hallie was in regular usage during the late 1800s and at the turn of the 20th century. It turns out that Hallie is actually a diminutive form of the old-lady name Harriet (much like Hattie). Harriet is actually a female version of Harry which itself is an English diminutive of Henry. Henry is the English form of the German Heinrich meaning “ruler of the home”. Harry is also sometimes considered a short form of Harold which is also Germanic for “ruler of the army." So over 100 years ago when we see Hallie in use, we understand this as an independently given name derived from Harriet. In which case the name would be pronounced HAL-ee instead of HAY-lee (as In Halle Berry). Today, however, Hallie is just another commonplace respelling of Hailey (a tremendously trendy and currently overused female given name). Hailey is derived from an Old English surname meaning “hay clearing” to describe a topographical location. The etymology of Hallie as derived from Harry is much more powerful (meaning “ruler”) so we like this origin better.” According to our cemetery records, I found 18 decedents with the moniker of Hallie. One of these can be connected to this rock, but may not be under it. Hallie Cecelia Hanshew was born on December 21st, 1841 here in Frederick. She was the daughter of Henry Hanshew (1785-1862) and wife Catherine Susan Stover (1801-1892). Henry was a private in the 1st Regiment of the Maryland Militia from August 25th-Sept 27th, 1814. He served under Captain Henry Steiner and his Artillery detachment. According to the 1850 US Census, the Hanshews can be found living with Mrs. Hanshew’s mother, Margaret (Hauer) Stover. Margaret was a sister to the famed Barbara (Hauer) Fritchie, making Catherine (Hanshew) a niece, and our subject Hallie a grandniece of Frederick’s famous flag-waver. Hallie was the ninth of nine children. She and her siblings helped in the family business of skin dressing. Certainly not a glamorous profession, skin dressers are involved with the preparation and dying of furs and skins to make them suitable for the manufacture of clothing. More specifically in our case, the 1860 US census lists Hallie’s dad, Henry Hanshew, as a glove maker, and a neighbor to the Fritchies. He worked with Barbara’s husband, John Caspar Fritchie, also known to be a glove maker. In my research, I was only able to uncover two references to Hallie, one in childhood and one in adulthood. The first is from lecture delivered to the Lancaster County Historical Society in the early 20th century. This speech was later published under the title: A Lancaster Girl in History, written by John H. Landis, and published in 1919. Below is the portion of that work which briefly mentions Hallie and a supposed role in the Barbara Fritchie incident of September, 1862: A second mention regarding Hallie Hanshew came within a biography on Dr. Franklin Buchanan Smith (1856-1912) that can be found in a book entitled Men of Mark in Maryland (Vol. 3), by David H. Carroll and Thomas H. Boggs. The passage from this book, published in 1911, reads as follows: “Doctor Smith had the advantages of an excellent education. His rudimentary education was received under Miss Hallie Hanshew, niece of Barbara Fritchie. He attended Frederick College, and then went to Princeton University, where he was graduate in 1876. After deciding to enter the medical profession, he took up his studies in the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania and was graduated in 1878, being one of the three prizemen of that year, i.e., that in Anatomy; and began the practice of his profession at Frederick in that year, after being substitute resident physician for six months at Blockley and Presbyterian Hospitals, Philadelphia.” This bears witness to the fact that Hallie Hanshew worked as a teacher at the Old Frederick Academy, once located on Council (formerly Counsel) Street in downtown Frederick. Just as she had in life, many of her Courthouse Square neighbors surround her in death here in Area E. I’m assuming Miss Hanshew’s career here at the school took place in the early 1870s, although it is not verified by either the 1870 or 1880 census records. Hallie never married and can be found living with her mother in the 1880 census. I assume this home was the same she had lived in her entire life on the south side of West Patrick Street near Carroll Creek. She would die just a few years later in 1883 of consumption. This disease is also known as tuberculosis, a progressive wasting away of the body especially from pulmonary tuberculosis. Hallie was buried in Mount Olivet in the Hanshew lot, however upon further review, I found two stones bearing her name. The first of these is quite peculiar and puzzling. Atop this supposed grave, would be placed a monument that resembles a boulder more than a traditional tombstone. On its face, the carved letters that form “Hallie” look as if they are formed of trees or plants. It’s the only one of its kind in a large Hanshew compound consisting of four lots and boasting 34 individuals surrounding a principal obelisk featuring the family name in the center. In studying our cemetery lot cards, I found another grave site accredited to Hallie C. Hanshew. This was immediately to the right of her father’s grave, however it is not pictured on the popular www.Findagrave.com site that we often talk about on in this blog. Perhaps the reason that I missed this stone, along with Findagrave volunteers, lies in the fact that the traditional marble gravestone is down and off its pedestal. It seems to be a straightforward repair, as the pins are still intact to the dye of the monument, but need to be properly fastened back in place and leveled. I did my best to hold up the stone in its upside-down state so I could get a picture. Without additional information, I’m assuming this latter stone marks Hallie’s original gravesite, however, I have no earthly idea about the Hallie boulder stone just up the hill in the Hanshew lot. “A Wish Fulfilled” A much more pronounced boulder memorial than Hallie’s can be found a few hundred yards south in Mount Olivet’s Area Q. Here, under the shade of a large tree at the base of Cemetery Hill, you can find more descendants of the famed Johnson family originally hailing from southern Maryland’s Calvert County. Of particular curiosity is the grave monument of Dr. William H. Johnson’s first-born son, William Channing Johnson (b. 1866) and his wife Laura Fauntleroy Johnson. Not a direct descendant of our first governor and local high school namesake Thomas, William Channing Johnson and his father and four siblings found in this cemetery lot are direct descendants of T.J.’s brother, Roger Johnson. Roger Johnson was a major in the American Revolution and had established an early iron furnace in southern Frederick county in the late 1700s at the foot of Sugarloaf Mountain. This operation was located just east of where MD route 28 (Dickerson Road) crosses the Monocacy River. Johnson had built a house in 1812 up the hill to the northeast of this furnace site on this estate he named Rock Hill. Its location can be reached by Dr. Belt Road. The Rock Hall mansion was built of red and white quartzite rock, also used to build the nearby C&O Canal aqueduct over the Monocacy River and quarried on the property. The oldest section remains stone, and the addition has stucco over stone. Records show the stone mason was paid $550 for building the shell of the house. The home would be owned by Magill Belt a century after its original construction and was among the musings of author William Jarboe Grove in my favorite Frederick heritage-related work entitled: The History of Carrollton Manor (published in 1921). Mr. Grove states in his book: “Pig iron from Johnson’s furnace was processed into bar iron, the article of commerce, at the Bloomsbury Forge near Urbana, the two operations being connected by barge along the Monocacy and Bennett Creek, and by Mount Ephraim and mountain roads built by the early enterpriser.” Roger Johnson’s principal home is still standing about a half mile from Rock Hall. He died in 1835 at the age of 82 and may, or may not, be buried in Mount Olivet. Our records refute this claim, however there is a memorial stone for him here in Area H, supposedly erected at the time of a re-interment around 1915. Roger Johnson was originally buried in a small family cemetery at Bloomsbury, which no longer exists. I mentioned this in a story written back in May of 2017 on Roger Johnson’s grandson, Dr. James Thomas Johnson, Jr. (1828-1899). This gentleman’s father of the same name (Dr. James Thomas Johnson, Sr. (1794-1867)) would inherit Bloomsbury mansion house (on Thurston Road) the principal residence of his father Roger Johnson. James Thomas Johnson, Sr. was the brother of Joseph A. Johnson (1790-1835), the father of the fore-mentioned Dr. William Hilleary Johnson. Joseph would acquire Rock Hall, perhaps at the time of its building. Dr. William H. Johnson was born in 1827 at Rock Hall and spent a great deal of his adult life in Adamstown. He spent his childhood at Rock Hall, owned today by Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources. The old dwelling has walls that are eighteen inches thick, and the wood-work is in perfect condition. After his graduation from the University of Maryland, Dr. William H. Johnson married Laura Brashear in 1860 and, like his brother James Thomas Johnson, served in the Confederate army during the whole period of the war as a physician. At one point, his young family was positioned in Missouri where he was stationed during the Trans-Mississippi campaign. Dr. Johnson continued in the medical profession after the conflict, and for many years was associated with his son Thomas, Jr. at Adamstown. The couple had five children, all of whom are buried in Mount Olivet. Mrs. Laura B. Johnson died in 1895, and Dr. Thomas H. Johnson would join her here in 1901. Two years later, an adult daughter, named Laura Brashear for her mother, would be buried next to her parents in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 243. In time, Laura’s sister, Mary Louisa Johnson, would share the same gravestone upon her death in 1952. A few feet away is the final resting place of Anne Elizabeth “Lizzie” Johnson, who had married Robert Moffett. Mrs. Moffett was the mother of four and died in 1917. Behind her grave is that of brother Dr. Thomas Brashear Johnson, Jr., who had a very good reputation as being one of the best surgeons in western Maryland. He passed in 1925 and has an ornate Celtic Cross monument over his grave. Both stones are as artistic as they are beautiful. That leaves one remaining stone in this interesting collection of rocks that vary drastically from one another like chocolates in a Whitman sampler. The last monument to talk about is the most unique of all. While it lacks physical beauty, it more than makes up for it in personality. I only know this fact because of a special iron plaque screwed into this boulder’s backside. It begins with a title: “A Wish Fulfilled.” While it differs from every stone in the lot and section, it is one of the most fascinating in all of Mount Olivet. You see, this memorial to Mr. and Mrs. William Channing relates to the family heritage site of Rock Hall in more ways than one. We better understand by perusing the affixed placard. So, this rock boulder of gray sandstone was quarried at the Rock Hill property as were those that make up the Rock Hill mansion house, not to mention the nearby Monocacy Aqueduct, one of the most significant history spots and architectural marvels in western Maryland. Mr. William Channing Johnson was born on March 7th, 1866 according to Ancestry.com, although a plaque on his stone gives 1865 as a birthdate. The obituary below from the Frederick Post (Dec 11, 1933) paints a nice picture of the life of William C. Johnson. William Channing Johnson died on December 10th, 1933 at his home in northwest Washington, DC. His funeral service would be held there. Mr. Johnson's body would be transported to Frederick and placed in the family lot in Area Q. I’d be curious as to the preparation of Mr. Johnson’s burial boulder. Was it in storage for years before his death, or was it gotten at or around his time of passing? Regardless, it was a special “wish” this gentleman had, and was successfully fulfilled. This stone not only represents a special geographical location, but more so a Frederick County familial heritage going back three generations. “Rock On!,” as they say! AUTHOR'S NOTE: After originally publishing this story, my faithful assistant Marilyn Veek told me of yet another interesting, "au naturel" grave marker. It is a much newer addition to Mount Olivet and can be found in our Area TJ. This marks the grave of John W. Gastorf (1940-2020). From the brief text on the plaque, this small boulder seems to be very fitting of the mark of this man.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed