|

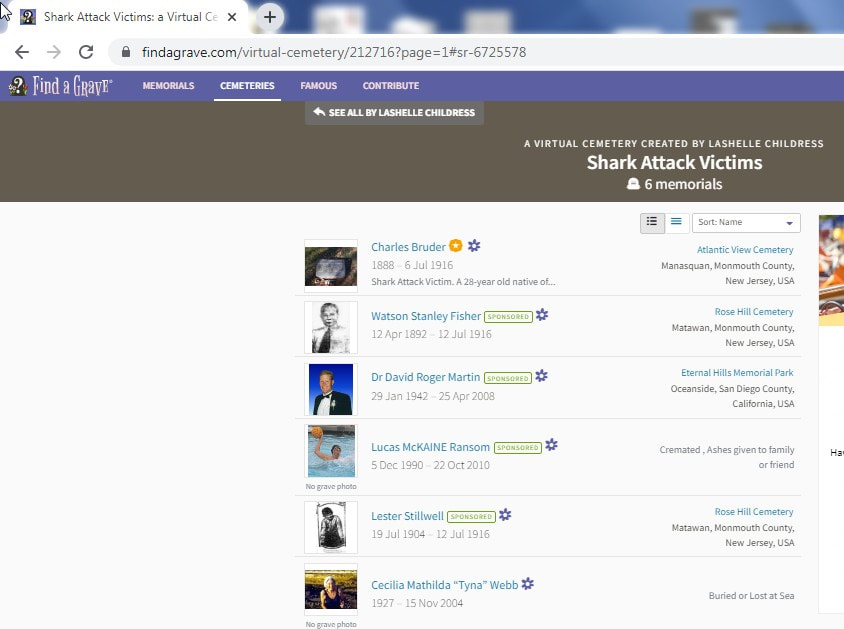

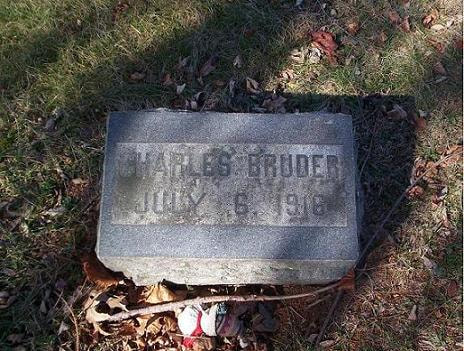

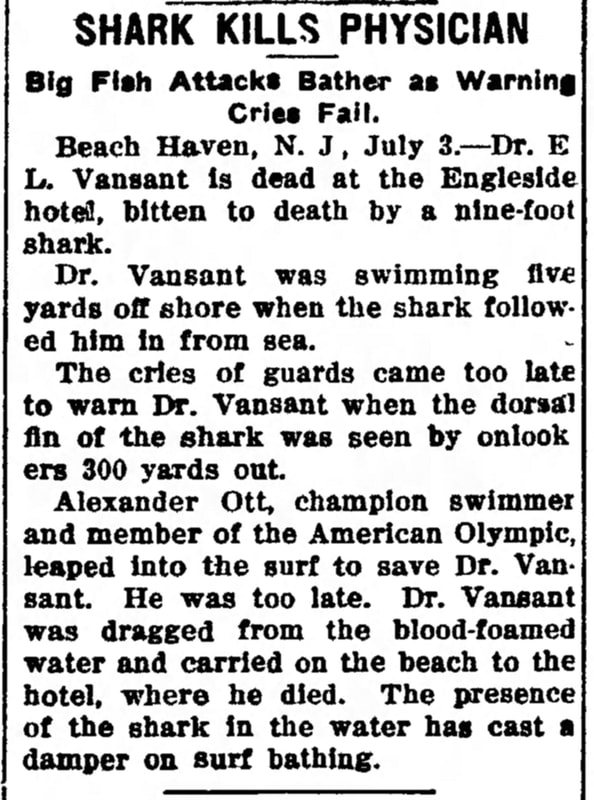

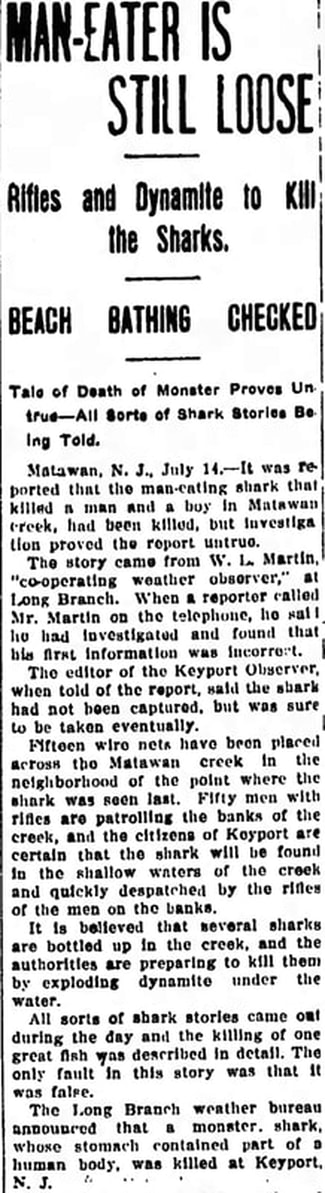

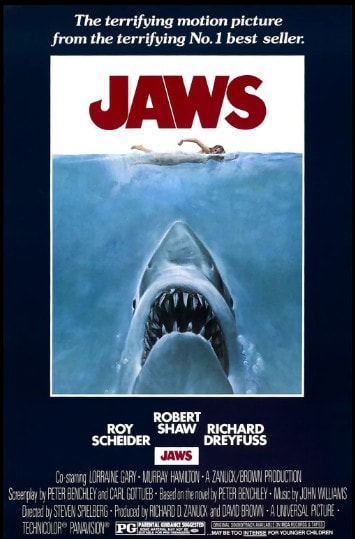

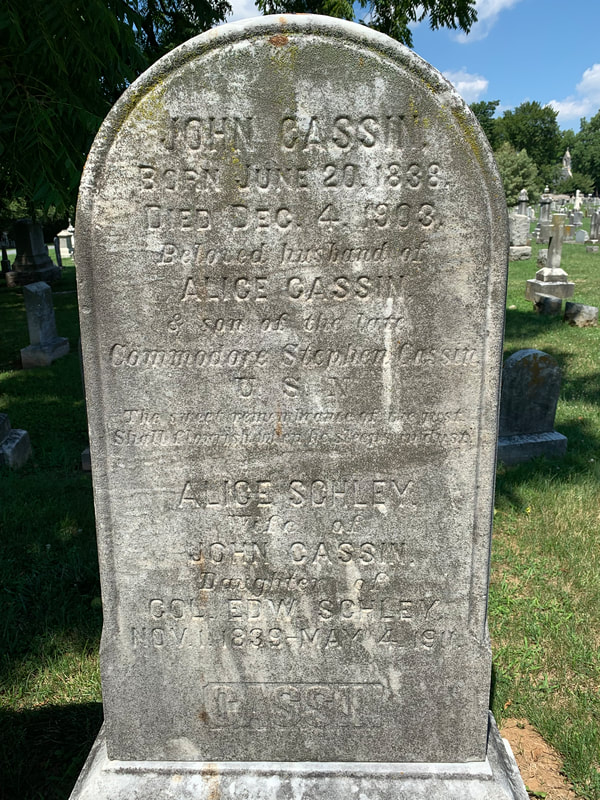

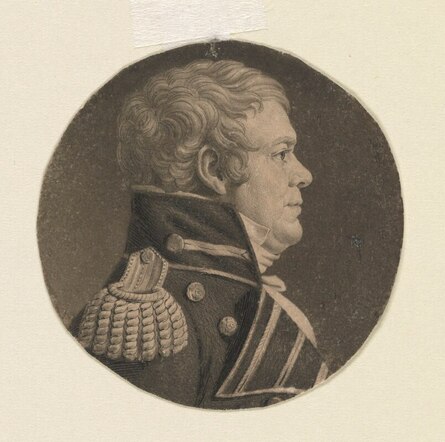

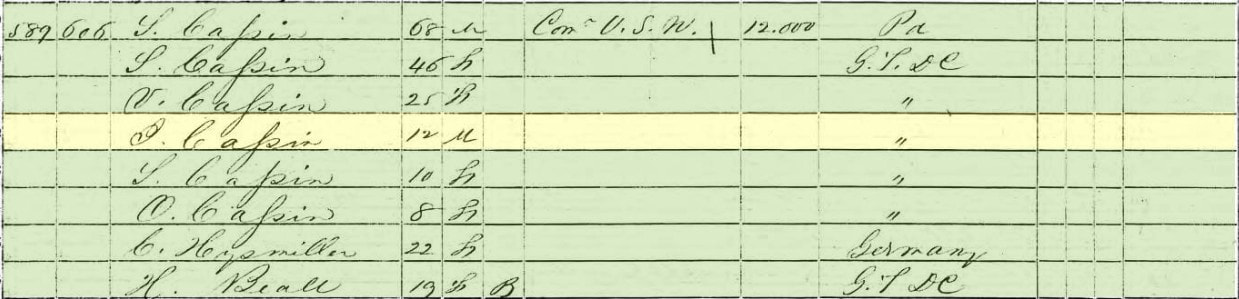

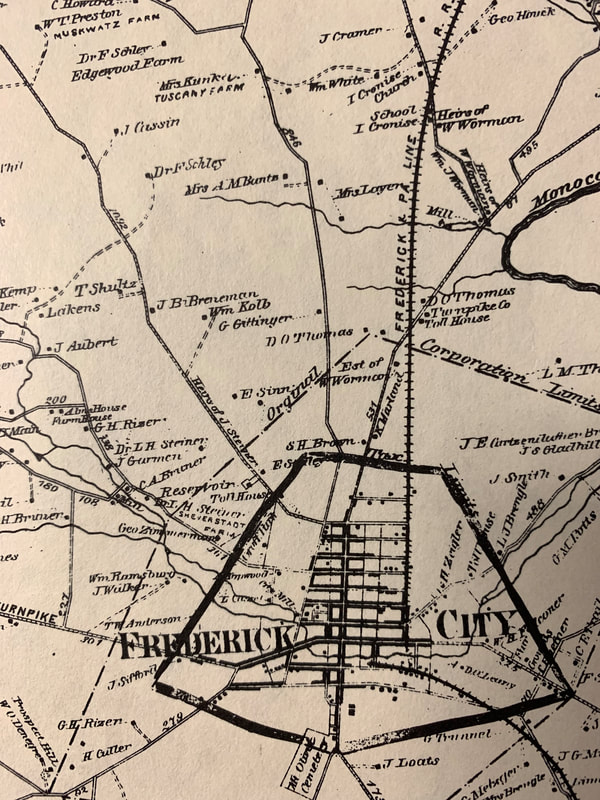

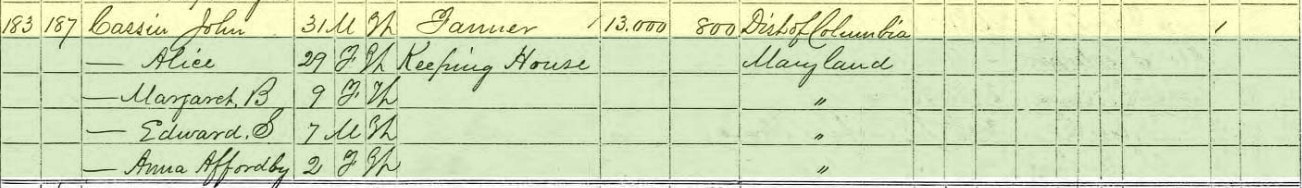

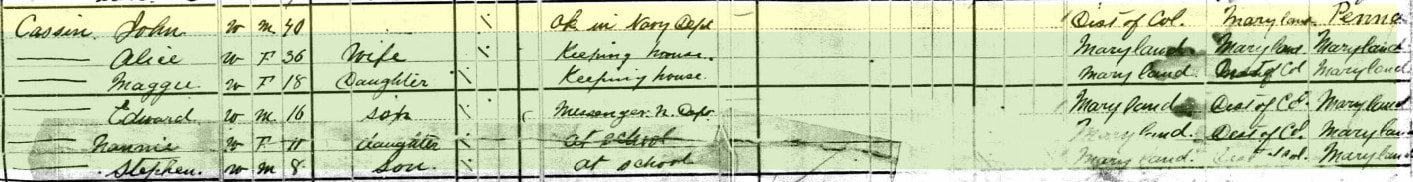

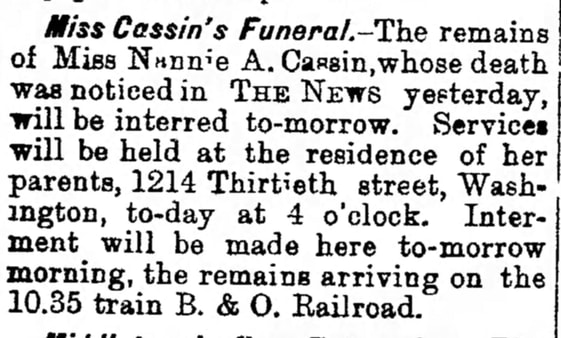

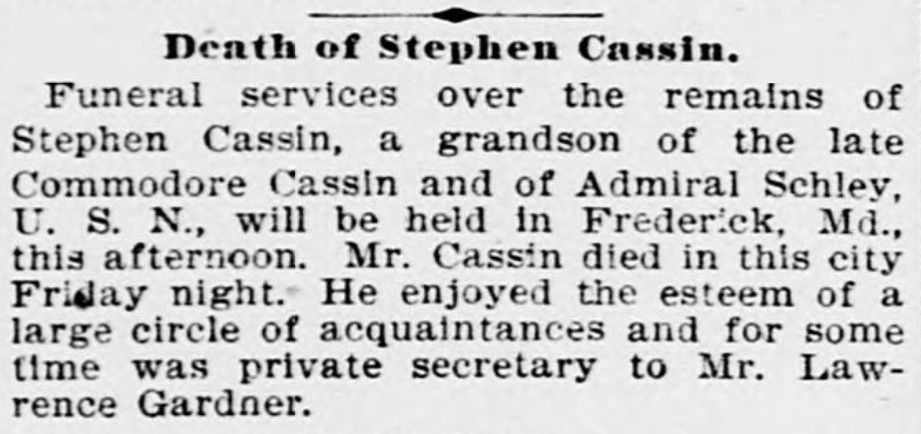

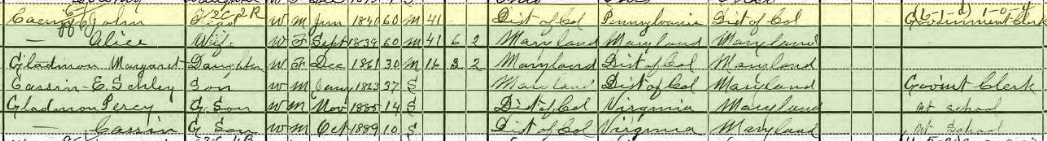

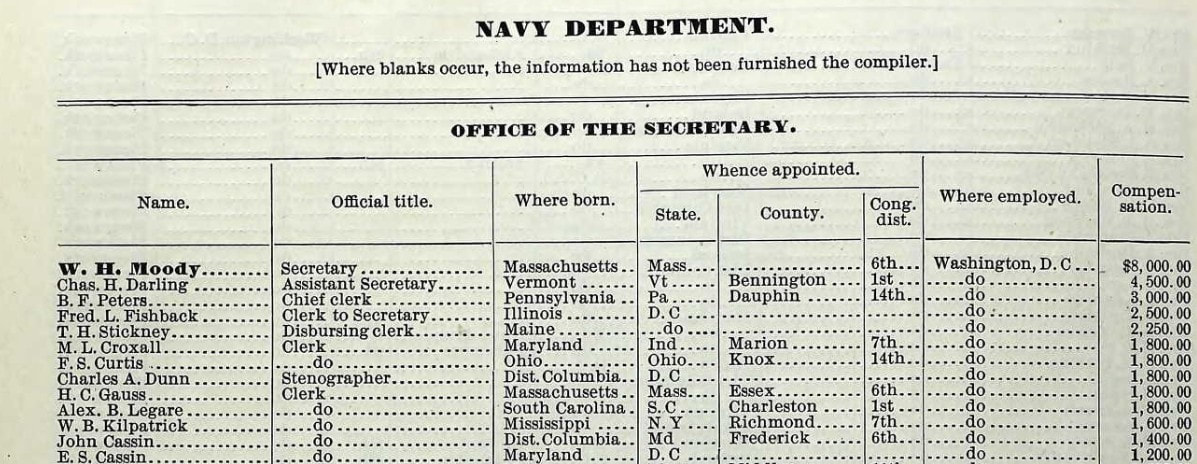

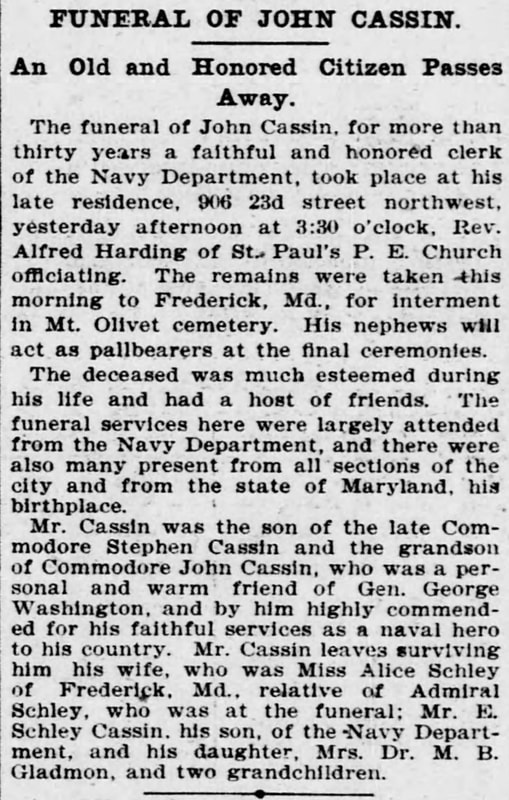

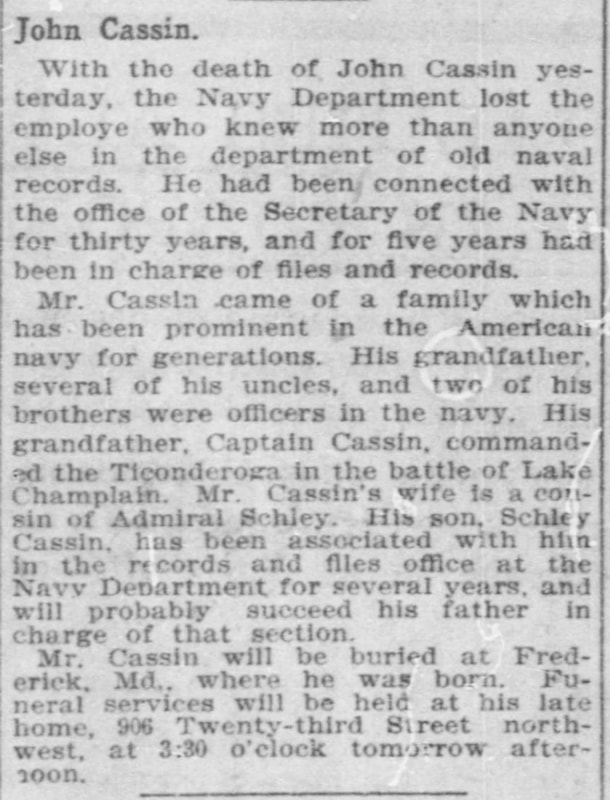

Happy “Shark Week” from Mount Olivet Cemetery! I can practically guarantee that this salutation has never been uttered by a human being ever before in the history of the world. It’s late July and we find ourselves once again in the midst of this unadulterated, yearly celebration of the cartilage-based fish possessing an infamous reputation akin to seafaring pirates of yore. For those unfamiliar with what I’m talking about here, Shark Week is an annual, week-long TV programming block found on the Discovery Channel, which features shark-based tv shows and documentaries. Now, mind you, I didn’t have this year’s event on my calendar or smartphone (July 24-30th, 2022). I was reminded this past Sunday morning while sitting on the beach in Fenwick Island, Delaware by a blimp.  In researching for this week’s “Story in Stone,” I learned that Shark Week originally premiered on July 17th, 1988 and is featured each year in either July or early August. It was originally devoted to highlight conservation efforts and correcting misconceptions about sharks. Over time, and with a keen marketing approach, the yearly “feeding-frenzy” of programming grew in popularity, becoming a major hit on the Discovery Channel, which is based just down the road in Bethesda. Since 2010, Shark Week has been the longest-running cable-television programming event in history and is broadcast in over 72 countries. After seeing that blimp overhead last weekend, I wondered if there was any way I could connect Shark Week to Mount Olivet? I have written about sharks before as they hold a unique connection to me as my son Eddie had the nickname of “Sharky” as a toddler—dating back to his days swimming around as a fetus. Seriously, as my wife and I chose not to know the sex of our child until birth. I refused to simply refer to the future child as “baby” in conversation, thinking it needed a nickname with frankly more bite. I also named my side “research for hire” business History Shark Productions, thus making me either the History Shark, or at least part of a legion or fraternity of “History Sharks.” So, my literary search for the dreaded “Great White” began right there on the beach. I began my search with our Mount Olivet database of interments and received “no bites.” I then scoured the Find-a-Grave.com page for Mount Olivet with a similar result. I then began thinking on national terms in an attempt to spark my creative juices. I certainly sailed off-course and soon found myself in troubled waters as I had landed on a unique Find-a-Grave tribute page of shark attack victims. This was compiled by an individual named Lashelle Childress and had absolutely everything to do with maneaters and cemeteries, but nothing to do with Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland. I decided to read further anyway. There are only a handful of names on this page, but three are in Monmouth County, New York. One such was Charles Bruder, a 28-year-old native of Switzerland, and former soldier in the Swiss Army. At the time of his death, he was employed as the Bell Captain at the Essex and Sussex Hotel at Spring Lake. Mr. Bruder was the 2nd victim of the infamous "Jersey Maneater Shark Attacks" of 1916. He was attacked by the shark, which bit off both his feet before he was rescued by the hotel shore patrol. He died on the beach from loss of blood and shock. Lester Stillwell was a 12 year-old boy who went swimming with friends in the Matawan Creek (Matawan, NJ) on the afternoon of July 12th (1916). As his pals watched in horror, young Lester was brutally attacked by a shark (still unknown as to what kind) and killed. Townsfolk quickly gathered at the creek and several men attempted to find Lester's body. One of the men, Watson Stanley Fisher, 24 years old, actually found Lester's body when he, himself, was attacked. Stanley died 12 hours later that day from blood loss from his wound, while Lester's body was discovered two days later. Because of his bravery and sacrifice, Stanley is remembered as a hero. Both he and Lester were buried on July 15th, 1916 at the Rose Hill Cemetery in Matawan. A gentleman named Dr. Richard Fernicola wrote a book about these tragic deaths entitled, "Twelve Days of Terror" about the shark attacks of 1916 along the Jersey Shore and in Matawan Creek. Four people would be killed or injured between July 1st and 12th. The event can be seen as the very first “Shark Week,” you could say, and took place against a backdrop of a deadly summer heat wave and polio epidemic in the United States that drove thousands of people to the seaside resorts of the Jersey Shore. Since 1916, scholars have debated which shark species was responsible and the number of animals involved, with the great white shark and the bull shark most frequently cited. Personal and national reaction to the fatalities involved a wave of panic that led to shark hunts aimed at eradicating the population of "man-eating" sharks and protecting the economies of New Jersey's seaside communities. Resort towns enclosed their public beaches with steel nets to protect swimmers. Scientific knowledge about sharks before 1916 was based on conjecture and speculation. The attacks forced ichthyologists to reassess common beliefs about the abilities of sharks and the nature of shark incidents of a violent nature. The Jersey Shore attacks immediately entered into American popular culture, where sharks became caricatures in editorial cartoons representing danger. The assaults became the subject of documentaries for the History Channel, National Geographic Channel, and Discovery Channel, which aired 12 Days of Terror (2004) and the Shark Week episode Blood in the Water (2009). Sufficed to say, my reservations about getting back in the water were “short-lived,” pardon the pun, but I was sure glad to be on the beaches of “Lower, Slower” Delaware than New Jersey, or, worse yet, Amity, Long Island, New York. The latter was the fictional site of the “Jaws” novel by Peter Benchley, and subsequent movie directed by Stephen Spielberg. These two offerings captured my imagination as a youth, as it did countless others, upon its release in the mid-1970s. That summer of 1975 had everyone going to the beach on high alert as the movie was released on June 20th. On a lighter, and related, note, exploration of Find-a-Grave.com led me to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s historic Allegheny Cemetery where there is as unique a tombstone as you will ever see. This marks the grave of Korean War veteran Lester C. Madden—self-proclaimed to be one of the biggest “Jaws” movie fans in the world. Mr. Madden was buried under a stone shaped like the iconic great white from the book’s cover and movie posters. I was certainly envious of Allegheny Cemetery for having such a stone, and told that to my history assistant, Marilyn Veek, upon my return to the office earlier this week. However, she brought to my attention the presence of a shark-themed gravestone in our midst here in Mount Olivet. It is located in Area TJ/Lot 87. Here, one can find the touching tribute to an 8-year-old who, I assume, had a great fascination with the Elasmobranchii family of which sharks belong. This is the final resting place of Mark Anthony Marketon, who passed away the day after Christmas in 2018. The Rockville native died at Johns Hopkins Hospital of an undisclosed illness. Mark Anthony’s gravesite, like Mr. Madden’s in Pittsburgh, is surely something to behold, and will keep his memory alive to cemetery visitors long into the future. Among the notable features are a photo collage, a glass front compartment housing favorite toys, and two renderings of sharks—a Great White and the silhouette of a hammerhead. I could not find any other sharks, but fish abound on gravestones throughout the newer sections of Mount Olivet. These are commonly chosen to designate avid outdoorsman or those desiring the religious connotation employing the symbol frequently used by early Christian writers in the Gospels to mean resurrection and infinity thereafter. Another thing that many sharks, and visitors to a cemetery, can encounter, are anchors. These “boat holders” typically symbolize hope and steadfastness, often serving as a symbol for Christ and his anchoring influence upon the lives of Christians. In coastal areas, the anchor also serves as a symbol for nautical professions and commonly mark the graves of dedicated seaman. Sometimes, the anchor can also be disguised as a cross to guide the way to secret meeting places. Much like the Victorian iconography of a broken column, an anchor with a severed chain represents death, in most cases prematurely. Two of our past Stories in Stone are shining examples of this as they tell the stories of two seafarers buried here in Mount Olivet: Captain Herman D. Ordeman and U.S. Naval engineer George A. Dean. Both fine monuments can be found in Area A. A few weeks back, a few gravestones connecting to a naval profession caught my attention. I was not far from Confederate Row, when I was pulled into a family plot in Area H, listed as Lot 506. Here lie seven members of the Cassin family. No anchors, fish or sharks for that matter, can be found on any stones. Truth be told, there are no symbols or memorable designs whatsoever. However, three of the six stones certainly beckon the sea in respect to the U.S. Navy and a former leading member of that branch. Problem is, this gentleman is buried elsewhere. These stones proudly express a familial relationship with Commodore Stephen Cassin (1783-1857), a native of Philadelphia who is buried at the famed Arlington National Cemetery. Here we have buried Commodore Cassin’s son, John Cassin (1838-1903), and grandson, John Stephen Cassin (1870-1895). Interestingly, John Cassin was married to Alice Schley (1839-1911), daughter of Col. Edward Schley and great-granddaughter of one of our Frederick Town founders—German immigrant John Thomas Schley (1712-1790) and wife Margaret Wintz. While Col. Schley had nothing to do with water in a military sense, he even got the proverbial "shout-out" on this gravestone too. Col. Schley's brother, Winfield Scott Schley, had everything to do with H2O as his career was based on it. Alice (Schley) Cassin’s first cousin, Winfield, was born in 1839 in Frederick at Richfields plantation, just north of Frederick City and along US Route 15. Just look for the billboard saying so along the highway and across from Beckley’s Motel and east of Homewood Retirement Community. Richfields was the original homeplace of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. before he moved in with his daughter at Rose Hill Manor after losing his wife. Interestingly, Winfield Scott Schley’s mother would die at Richfields as well along with some of Winfield’s siblings. This supposedly spooked his father, John Thomas Schley, Jr. (1808-1876), who began to question the safety of drinking water on the property. This precipitated John to move his family to downtown Frederick—200 East Church Street to be exact, on the southeast corner as it intersects Chapel Alley. Winfield attended St. John’s Catholic School across the street from his home, and then went off to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis where he graduated in 1860. He served in the American Civil War and eventually rose to the rank of rear admiral in the United States Navy and the hero of the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War. He died in 1911 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery as well as the forementioned Stephen Cassin. Admiral Schley’s parents (John Thomas, Jr. and Georgianna) were farmers and are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area P, along with several of his siblings. In neighboring Area F/Lot 41, one can find Admiral Schley's uncle, Col. Edward Schley, father of Alice (Schley) Cassin. I’m assuming that Winfield Scott Schley was well aware of the exploits of his cousin’s father-in-law. (Stephen Cassin). Perhaps old Admiral Schley was responsible for the introduction between cousin Alice and Commodore Cassin’s son John Cassin. We may never know, but I found it interesting that these cousins have the same vital dates by year. Before we look at John Cassin a bit closer, I’d like to share some information on his father Stephen Cassin (Feb 16, 1783-August 29th, 1857). He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery's Section 1, Grave 299. Here is what his biography on FindaGrave.com says: United States Naval Officer. He began his Navy service in 1800, when he was appointed as a Midshipman. He took part in the Barbary Wars, and had risen to Lieutenant by the outbreak of the War of 1812. Sent to serve under Commodore Theodore MacDonough in Lake Champlain, he assisted in building up American Naval forces there, and was given command of the “USS Ticonderoga”. He performed well at the September 11, 1814 Battle of Lake Champlain, directing his ship as it fended off British attacks and a boarding party. Commended by Commodore MacDonough, Stephen Cassin was awarded a Gold Medal by the United States Congress a month later for his performance. He ended the war with the rank of Master Commandant. Remaining in the Navy, he achieved the rank of Captain in 1825, and Commodore in 1830. In 1822, while in command of the “USS Peacock”, he captured and destroyed a number of pirate vessels that had been preying on shipping in the West Indies. Stephen Cassin died in 1857, and was originally interred in Georgetown, DC. He was subsequently removed to Arlington National Cemetery, where his remains lie in Section 1. Two United States Navy Destroyers have been named “USS Cassin” after him – DD-43, which served during World War I, and DD-372, which was heavily damaged at Pearl Harbor, but was salvaged and won six battle stars during World War II. Our John Cassin was named for his grandfather who also experienced a storied career with the US Navy. This gentleman, John Cassin (1760-1822) was born in Philadelphia and buried in St. Mary of the Annunciation Catholic Chirch Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. Little is known of John Cassin's early life, but what is known reveals he fought in the Revolution as early as 1777 participating in the Battle of Trenton and continuing his service with the Army until he became a First Mate as a Pennsylvania Privateer on board the "Mayflower" on June 27, 1782. After the Revolution Cassin became a merchant seaman, twice being shipwrecked near the turn of the century it became necessary to increase the size of the Navy due to the ongoing Barbary pirate attacks along with other potential threats. He enlisted as a Lieutenant on November 13, 1799. On April 6,1806 he was promoted to Master Commandant and became second in command of the Washington Navy Yard. On July 3, 1812 he was promoted to Captain, then the highest rank in the United States Navy. During the War of 1812-1815 he led the United States Navy in the Delaware for the defense of Philadelphia. He was also the Commanding Officer of the Norfolk Naval Shipyard from August 10, 1812 until June 1, 1821 when he was chosen to be the Commanding Officer of the Southern Naval station based at Charleston, South Carolina.  The Crawford-Cassin House still stands in Georgetown at 3017 O Street. Built in 1818, the gardens of the property once extended to 30th Street to the east and to P Street on the north. The house is still accessible from P Street by a private driveway. Early in the 20th century the building was altered and enlarged to be used as a private school. Today it is again a private residence, which recently sold for $13 million dollars. Our subject, John Cassin, was born in Washington, D.C. on June 20th, 1838. The Cassin family was living in style in Georgetown in the 1850 US Census. I will venture to say that perhaps John was sent to Frederick’s St. John’s Academy for his schooling as this would explain the opportunity to meet his future wife, and perhaps Winfield Scott Schley was a classmate, and better yet, a friend. In 1860, while Schley was graduating from the Naval Academy, young John Cassin had taken a different path in life away from military service. He is listed as a farmer and living in a downtown hotel operated by Michael Zimmerman. By 1870, he appears to be farming his own farmstead north of town in the Yellow Springs area. Further research showed that John bought a 100-acre farm on Yellow Springs Rd (in the deed the road was called Spout Springs turnpike) in 1859, but would lose it to bankruptcy in 1873. He had 3 mortgages on the property, 1 to H D Ordeman, 1 to William White, and 1 to Nathan Neighbours and B. H. Schley (presumably Major Benjamin Henry Schley, Alice's brother). My assistant Marilyn gave me the idea that Alice's parents or other relatives could have played a role in influencing them to buy the farm, since "Dr. Fairfax Schley" owned properties nearby. The area of Cassin's farm is now the Clover Hill development. John and Alice would raise four children into adulthood: Margaret “Maggie” B. (b. 1862); Edward Schley (b. 1864); Anna “Nannie” Affordby (b. 1869) and John Stephen (b. 1870). By 1880, he had traded in his plough for a pencil. His family moved back to his old hometown of Georgetown. and he was employed as a clerk for the US Navy Department. I’m guessing this occurred around 1873, likely as a result of the bankruptcy. However, this was the same year that marked the death of his father. I found later that he started in his employment with the Navy that same year. John and Alice’s daughter Nannie died of Typhoid fever at age 18. She would be laid to rest back here in Frederick next to her father’s sister, Olivia (1842-1867), who had died in 1867 at age 25. Two years later (1869), two of John and Alice’s children were reburied here in the family plot. Through Ancestry.com, I found one of these was Alice Cassin (March 22, 1865-Dec 4, 1869). Another son, John Stephen, would die in 1895 (aged 25) of Typhoid fever like his sister. In 1900 the John Cassin family was living on 23rd Street in Northwest D.C. I found a US Navy employee U.S., Register of Civil, Military, and Naval Service directory from July 1903 which shows both John and son Edward working as clerks for the Navy Department. Coincidence or plain old nepotism, you be the judge? However, one cannot deny that those Cassins had great connections to naval heroes. John Cassin died five months later on December 4th, 1903. His mortal remains came back to Frederick for burial. From his obituary, I was excited to learn that Admiral Schley had attended his funeral service. Alice would die in May, 1911 as mentioned earlier. Her son possessing her Schley maiden name, Edward, died of nephritis less than 16 years later and is buried here in the family plot as well. Margaret B. (Cassin) Gladmon passed in 1926.

It might not be obvious to the casual visitor, but this family certainly was connected to the sea through familial connections. If anything else, they sure were proud of the Commodore. Maybe it's because they knew their life blessings could be attributed to his fame? Who knows? That's it, that's my story and I'm sticking to it. Not quite Shark Week material, but neither is receiving writing inspiration from a blimp at the beach when you get right down to it. Unless, of course, that blimp has sharks all over it. I bet little Mark Anthony Marketon would have really got a kick out of seeing that contraption flying overhead.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed