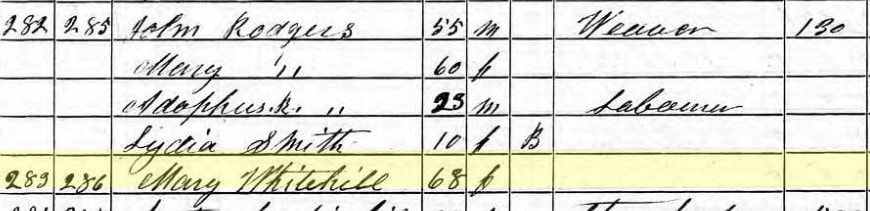

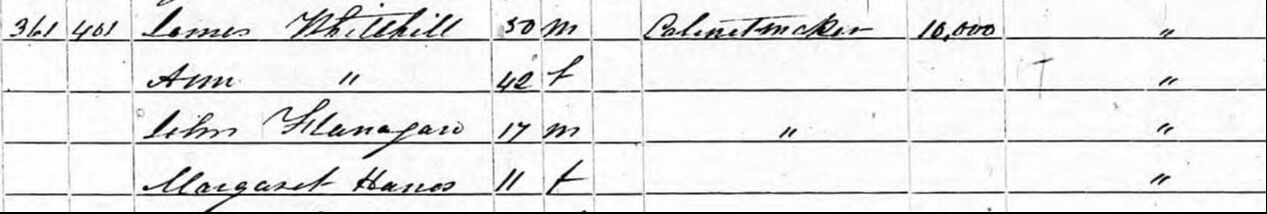

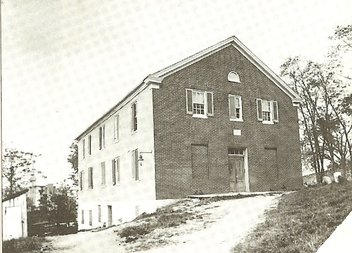

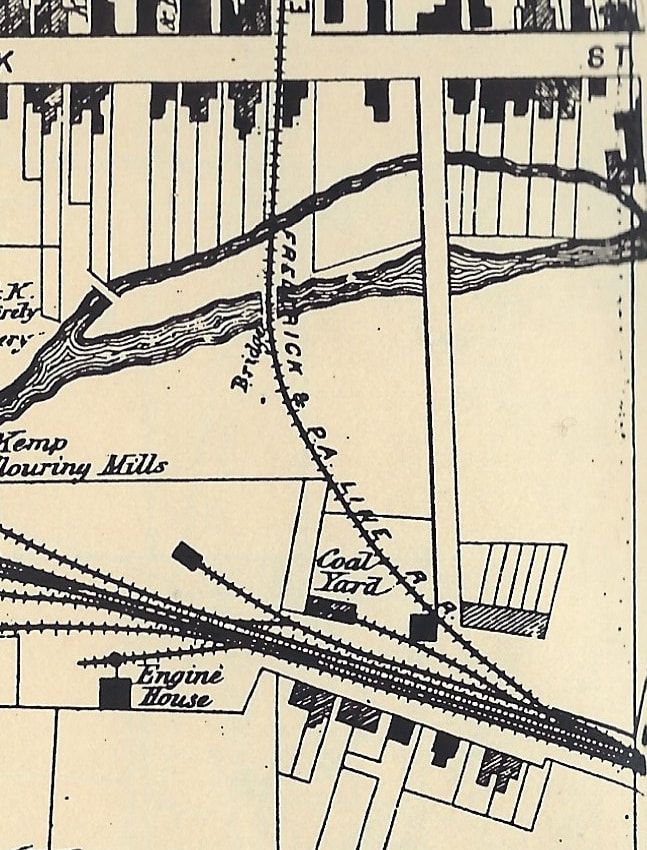

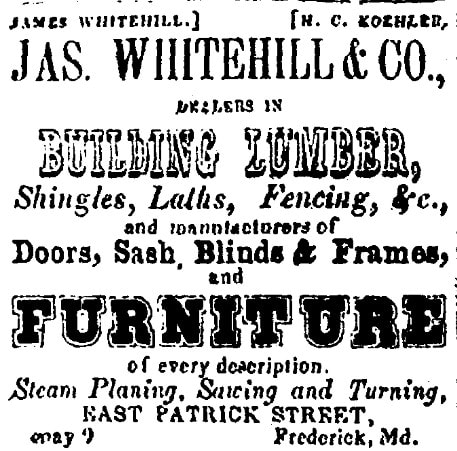

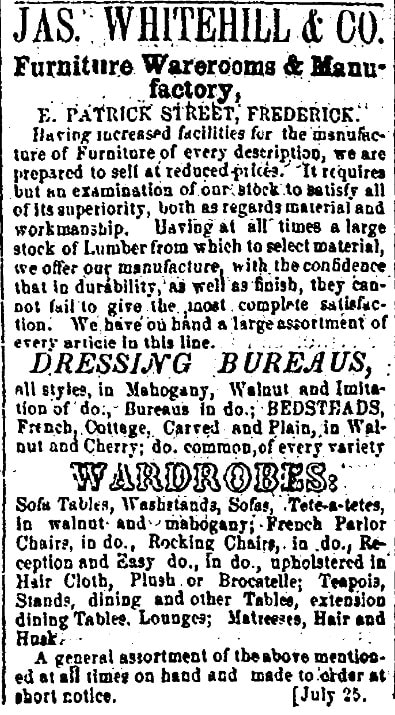

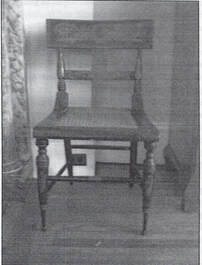

Halloween (a contraction of "All Hallows' evening") aka Allhalloween, is a celebration observed in many countries on October 31st, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day. It begins the observance of Allhallowtide, the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed. Well then, that completely explains the iconic symbols associated with the day (Halloween), at least in terms to pop culture. Fittingly, graveyards have played an important role in the real commemoration of the dead, obviously. But this also holds true in the commercially-based, candy and costume-riddled version because one could hypothetically find many iconic Halloween-oriented objects within a burial ground, or cemetery. Take ours for example. We have a few jack-o-lanterns, and I’m sure a random bat or two, but I am pleased to report that I have not encountered a ghost, witch, warlock, vampire or werewolf in my five years of working at Mount Olivet. However, I must confess that we are not short on tombstones, coffins, skeletons and skulls. Well, we are short on one of the latter, but I will get to that later. A friend, and former work colleague of mine, Ron Angleberger, and myself, have been conducting candlelight walking tours of Mount Olivet since 2013. The majority of these nocturnal sojourns have occurred in advance of Halloween, and for good reason. Ron certainly has more experience in the “macabre” tour game as he is the brains behind the popular Downtown Frederick Ghost Tours. I’m no slouch either, as I can certainly ”carry my water” as the historian and preservation manager of this historic garden cemetery and love conducting these tours as well. That said, we continue to both try our best to reverently “wow” visitors with the amazing history and stories of those buried here in Mount Olivet’s past. Over the years, the cavalcade of tour patrons has ranged from kids to teens, young couples to middle-agers up to seniors. This fall, I decided to step back from conducting the general public tour, allowing Ron to take the lead. I, instead, have concentrated on developing/delivering tours to our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group, not to mention students associated with Frederick Community College’s Institute for Learning in Retirement (ILR) program. One common stopping place, on all of these sojourns, has been a particular hillside gravesite in Area F. Lot 25 to be exact. It belongs to one of the cemetery’s founding members, while the site itself, represents only one of two built-in, ornamental crypt tombs in our cemetery. His story and final “resting” place has Halloween written all over it. The gravesite of James and Ann Whitehill is one to behold, even though it took on a more prominent air in olden days. Today, it just seems a bit more subdued in contrast to its former reputation as representing the prominent, strong-willed resident that it would hold for eternity. This has been the case for the past 15 years, dating back to some unfortunate events which occurred here in early 2005. More about that later, as I think I should start by telling you a bit about the “souls” encrypted here, but they were anything from poor!  Thanks to talented, professional photographer Van Corey, we have this photograph of the Whitehill crypt from 2003 Thanks to talented, professional photographer Van Corey, we have this photograph of the Whitehill crypt from 2003 The Whitehills Instead of re-inventing the wheel, I have gladly turned to an old friend of mine, Joyce Cooper, for expertise on our prime subject this week as she wrote a comprehensive biography on this gentleman and his family for the Fall 2002 edition of the Journal of the Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland. Joyce relocated to Walton, Kentucky years ago with her family. Thanks to FaceBook, I have her secured as a friend, only a simple “Messenger” message away these days. I fondly recall the assistance, support and expertise received in my early research and documentary endeavors from the article’s author, Joyce Cooper, a former teacher and longtime staff member of the Historical Society. In respect to James Whitehill, she performed exhaustive research in an effort to glean more about this man because of his connection to many of the items residing in the Society’s archival and artifact collection. Whitehill was a prominent businessman in town and had his hand in all kinds of endeavors, the greatest of which was furniture making, primarily from a location that is very much known today by locals and visitors alike—the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Joyce did an amazing job in capturing the vivid events of a difficult childhood for Mr. Whitehill caused by an abusive father. However haunted his early life seems, James seemed to keep his head on straight and would rise to become one of Frederick’s leading citizens in his adult life—a true testament to human resiliency. Sadly, he did not have much opportunity to reverse the cycle of fathering to his own son, as a lone child would die as an infant at six months of age. James C. Whitehill by Joyce C. Cooper James Whitehill’s ancestral roots were firmly anchored in the British Isles. While his maternal great-great-great grandparents emigrated from England, his paternal great-grandparents, James and Rachel Cresswell Whitehill, arrived in America from Renfrewshire, Scotland. They married in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where they spent the rest of their lives. Their son David Whitehill, born May 24, 1743, married Rachel Clemson in Salisbury Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The children born to David and Rachel exhibited the wanderlust typical of the period, most of them spreading into central and western Pennsylvania. Their son John, however, moved to Maryland where he married his fifteen year old first cousin, Mary Clemson, a daughter of John and Elizabeth Haines Clemson. Following their marriage in August of 1795, John and Mary set up housekeeping on a farm near Libertytown, Maryland, owned by Mary’s father. Mr. Clemson allowed them to live rent-free for two years, and provided them with “two horses, some other valuable stock, and household and kitchen furniture.” The young couple may have had a difficult time financially, for Mr. Clemson rented the farm to them for several more years at a “moderate rent much below the real value.” Three children were born to John and Mary Whitehill during their first five years of marriage, with three more surviving children being born by 1815. James Clemson Whitehill, their second child and first son, was born August 12th, 1798. Unfortunately, young James and his siblings must have known times of great unhappiness during their childhood years, based on evidence found in court records. A “Bill of Complaint of Mary Whitehill” addressed to “the Honorable Judges of Frederick County sitting as a court of Chancery,” dated April 20, 1815 and presented by John Clemson, Mary’s father and “next friend,” details a life of spousal abuse. Mary’s complaint paints a graphic picture of a hard-working woman struggling with a husband who “day after day...was rioting in taverns or wasting their mutual gains in the most criminal debauchery.” Somewhat balancing the aggrieved wife’s statement was the testimony of Leonard Six, taken October 16, 1818 by the court. The abstract of his testimony says that “Whitehill, when in a state of intoxication was a high tempered man, but not apt to get out of humor unless he is brought to it. That when sober, he was as good a tempered man and sociable neighbor as he would wish to live beside.” Good neighbor that he might have appeared to be to outsiders, John’s wife alleged that she had suffered John Whitehill’s abuse in silence for most of her nearly twenty years of marriage, hoping to “at least ward off his unkindness” by being a loving and good wife. Rather than showing her respect, if not love, he beat her severely and repeatedly. Finally, one April evening he threatened to kill her if she did not leave their home in one minute. Their oldest daughter, Rebecca, described to the court the horrible scene played out before the children: I was present at the time of the separation of John Whitehill and Mary Whitehill. He said if she did not go he would murder her. She begged for God’s sake that he would spare her life. That she wanted to live with her children. The more she begged, the more he swore. He said he had sworn the hardest oath that a man could swear. That she would go and would give her but one minute to clear herself or he would murder her. These threats were made in the house. Mary Whitehill was suddenly driven off without any clothing more than those she was wearing. A horse was brought for her to ride away on by order of John Whitehill who helped her on. ‘Twas near sunset. She went alone except having her infant child with her. Certain court records indicate that Mary returned to her father’s home. On March 9, 1826, over ten years after Mary’s initial bill of complaint, the court annulled John Whitehill’s parental control and gave Mary custody of her minor children. Hopefully, the court also ruled in Mary’s favor on her request that John Whitehill make “adequate and valuable provisions” for her financially. Her case was pressing, for her husband had “lately given out that he will speedily leave this state and go into some one of the Western states to reside,” a move that would endanger Mary’s claim and make it “difficult for the complainant to recover the same.” John Whitehill died in 1829, but Mary lived until March of 1862. At the time of the 1850 Federal Census, she lived in her own home near Libertytown a few doors from the homes of her brother John Clemson and her nephew Dennis Clemson. By the time Mary won her custody case, her two older daughters had married, and her son James had embarked on his career as a furniture maker. He announced his business in the December 14, 1822 issue of the Frederick Herald. James Whitehill Cabinet-Maker Respectfully informs his friends and the public generally, that he has commenced business in Liberty-Town, and is now prepared to execute any kind of work in his line, in the most fashionable and substantial manner, and on very accommodating terms. He also intends to keep on hand a Supply of furniture neatly finished, and by his diligence and industry hopes to be liberally patronised [sic] by the public Seven years later he announced the opening of his business on East Patrick Street in Frederick in the April 25, 1829 issue of the Frederick’s newspaper, The Examiner. Furniture The subscriber would notify the citizens of Frederick-town and county that he has removed to Frederick, and purposes carrying on the Cabinet and Chair Making Business extensively. His shop is in Patrick-street, nearly opposite the store of Mr. Stuart Gaither, where he can supply all kinds of furniture either of mahogany, walnut or cherry; also plain and elegant chairs. All orders promptly attended to, and the Work executed in the best manner. Two Journeymen Cabinet-makers who are sober, industrious, good workmen, will find immediate employment. James Whitehill His move to Frederick was not the only major change in James Whitehill’s life that transpired in 1829. On February 9, 1829 he married nineteen-year-old Ann Campbell, daughter of Bennett and Catherine Devilbiss Campbell. In addition to the Devilbiss family, Ann’s ancestral lines included such early Frederick families as the Barricks (Bergs), Herzogs, and Stulls. Just where the newlyweds lived is unknown, but the 1850 Census lists them on East Patrick Street, probably living over his shop. According to the 1850 census information, James owned some $10,000 in real estate. He had $3000 invested in the business, with an inventory of wood valued at $1200, hardware valued at $500, and finished furniture worth $500. The manufactory, employing seven men whose salaries totaled $175 monthly, relied on hand power. His household included James himself, his wife Ann, John Flanagan (age 17) and Margaret Hanes (age 11). John Flanagan may have been an employee, and Margaret Hanes was likely a relative of Ann Whitehill. No children are listed, for the only known child of the Whitehills, a son named James Campbell Whitehill, would not be born until 1852 and lived only six months. James Whitehill and his employees conducted several branches of business at the East Patrick Street location for nearly four decades. Foremost was the manufacture and sale of furniture and an associated activity—coffin making. In addition to coffins, Whitehill offered for sale the “Fisk Metallic Burial Case” with a rosewood finish in his January 9, 1856 advertisement in the Frederick Examiner. Whitehill’s third branch of business was selling lumber and other building materials. The Examiner of January 4, 1854 contains his advertisement for shingles, lathe and lumber. In March of 1856, a Maryland Union advertisement announced to the public that he had “just received 150,000 Cypress Shingles, of very superior quality” as well as lumber, lathe, sash, blinds, doors, windows, and frames. A detailed advertisement found in the Maryland Union newspaper ran for several weeks in the spring of 1856:

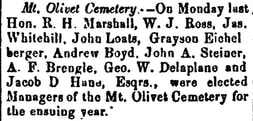

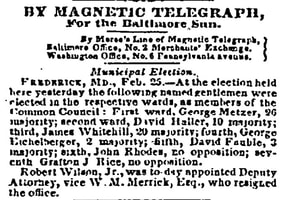

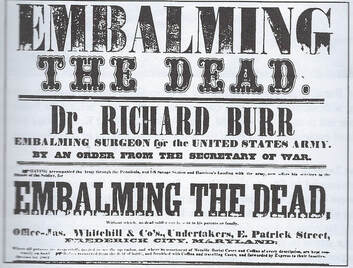

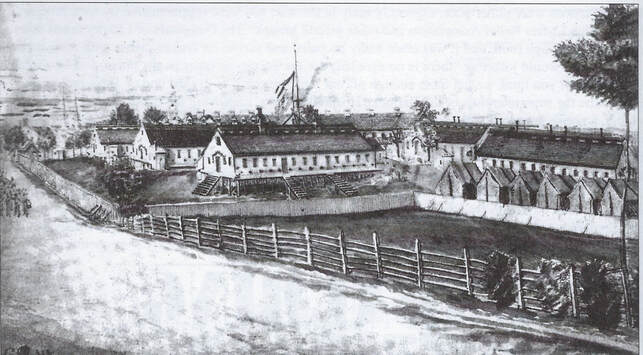

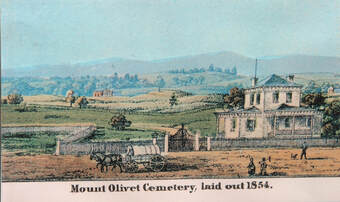

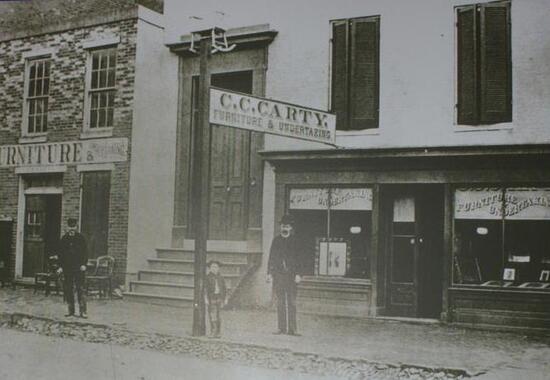

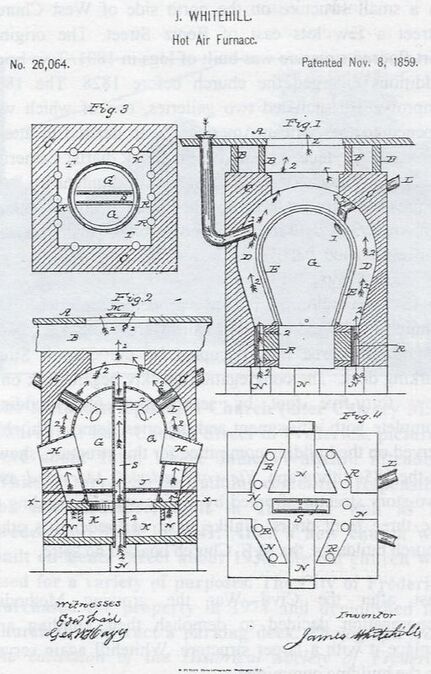

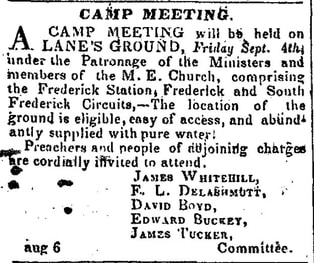

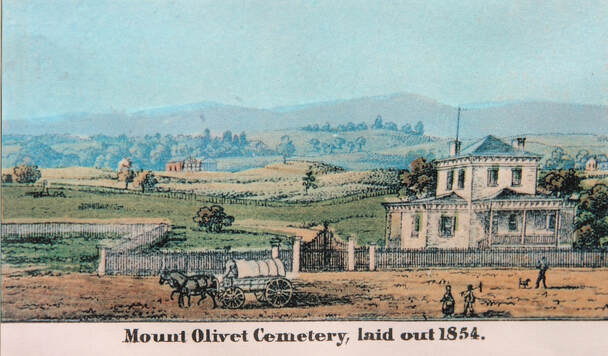

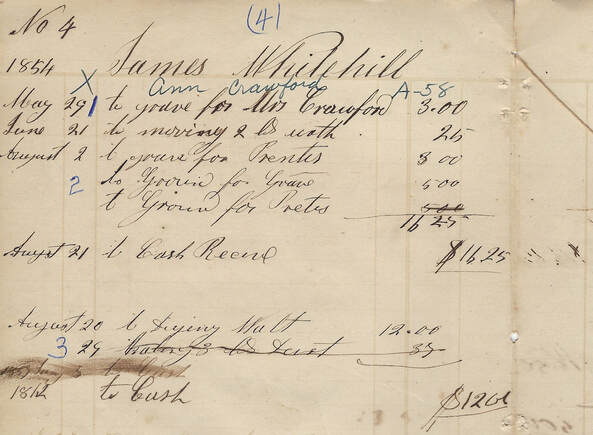

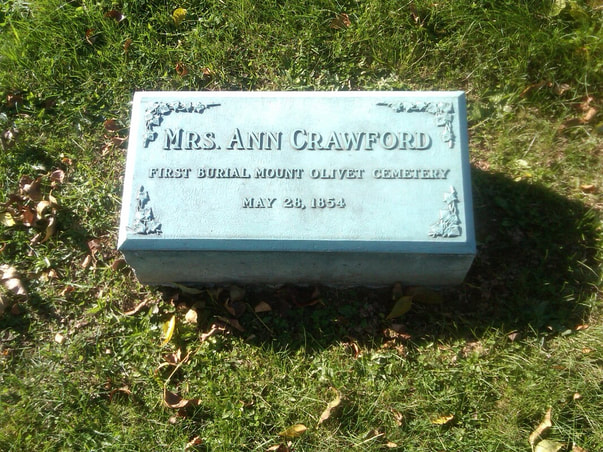

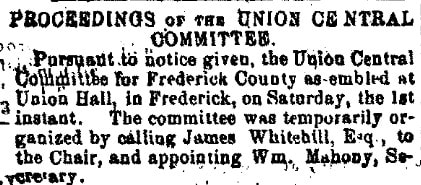

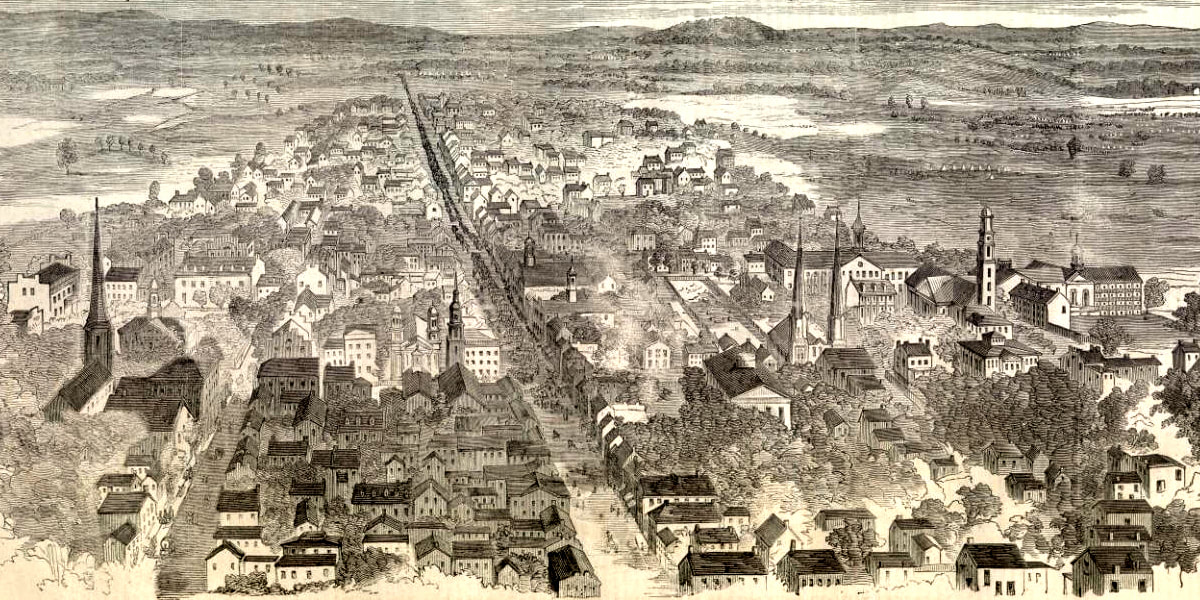

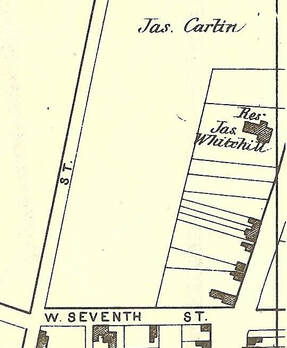

Engelbrecht identified another construction project when he wrote, “Nearly the whole winter and at this time Mr. James Whitehill is putting up three small brick buildings at the depot. Remarkable mild season this. Friday January 22, 1858.” In his will, Whitehill seemed to refer to this completed project, describing it as “six brick houses known as ‘Whitehill’s Row’ near the lower depot of the B & O Railroad.” Jacob Engelbrecht provided further information on Whitehill’s changing business activities in his Wednesday, November 7, 1866 entry: “’Lumber yard’ –John C. Hardt and Hiram M. Keefer bought from James Whitehill his lumberyard in East Patrick Street. They took possession on Monday morning last.” This sale involved only a portion of Whitehill’s complete property. In 1870 Whitehill retired from the furniture business, which was purchased and carried on by Clarence C. Carty and his descendants for many years. Though retired, Whitehill launched another business venture, purchasing the “brick yard, lime kiln and dwelling out Church Street below and South of the Gas House for $7000 from John A. Steiner,” according to Engelbrecht’s diary entry for April 13, 1870. He operated this business until his death. Perhaps his involvement in the construction business stimulated his inventiveness. The United States Patent Office holds Whitehill’s application for Patent No. 26,061, dated November 8, 1859. The letter that accompanies his detailed drawings begins: To all whom it may concern: Be it known that I, James Whitehill, of Frederick, in the county of Frederick and State of Maryland, have invented a new and usefull (sic) improvement in Hot Air Furnaces; and I do hereby declare that the following is a full, clear, and exact description of the same, reference being had to in the accompanying drawings, forming a part of this specification…” Whitehill’s design involved a double firebox, allowing for the use of one or both parts to heat the air in the chamber between them. Thus, the temperature of the air in the chamber could be somewhat regulated to accommodate the needs of the homeowner as the weather fluctuated. But James Whitehill was not solely a man of business; he took an active part in community affairs—religious, civic, and political. He was an active member of the Methodist Episcopal Church, being one of the trustees named when an act of the General Assembly of Maryland incorporated the Frederick Methodist Episcopal Church in 1840. In 1841 the church purchased a property fronting on East Church Street and extending northward to Market Space, roughly the area now occupied by the Church Street parking deck. The congregation quickly began work on a new 45’ x 75’ building, complete with a basement and galleries. James Whitehill served on the building committee for this structure, shown in the 1854 lithograph View of Frederick, Maryland as a two-story structure fronted by a wide stairway leading to the three front doors. Unlike most of Frederick’s other church buildings, the Methodist Episcopal Church boasted no spire.  Frederick Examiner (May 10, 1860) Frederick Examiner (May 10, 1860) Another area of Whitehill’s sphere of community involvement was the establishment of Mt. Olivet Cemetery. Churches and cemeteries were closely related in Frederick during the first hundred years of its history, when several congregations maintained their own graveyards, often behind their buildings. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, these cemeteries were nearly full. The community urgently needed a new burial ground. Therefore, the Judges of the Circuit Court incorporated a sizeable group of men—including James Whitehill, William J. Ross, Richard Potts and John Loats—as the Mt. Olivet Cemetery Company in October of 1852. The next year lots and driveways were laid out on the thirty-two acre cemetery property. In May of 1854 the cemetery received its first burial. Jacob Engelbrecht reported: The first corpse buried on the New Cemetery—Mrs. Ann Crawford, who died at the house of Mr. James Whitehill on Sunday evening, May 28, 1854 was buried on “Mount Olivet Cemetery.” This was the first burial on the cemetery since they dedicated it—there had been several bones removed the week or two before. Old Mr. Baltzell and wife (father and mother of Doctor Baltzell & several others. Reverend Alexander E. Gibson officiating Minister (of Methodist Episcopal Church). Tuesday May 30, 1854. 7 o’clock A.M.  Baltimore Sun (Feb 26, 1851) Baltimore Sun (Feb 26, 1851) Yet another of Whitehill’s avocations made its way into Engelbrecht’s detailed diary entries. The diarist often recorded details of political affairs at all levels of government. As early as the 1830s, James Whitehill appears as a frequent candidate and sometimes winner in Frederick’s elections for Board of Alderman and Common Council. Perhaps politics ran in the Whitehill blood, for several of his Pennsylvania relatives were politicians; at least three served terms in Congress during the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Jacob Engelbrecht chronicled Whitehill’s political career, starting with his unsuccessful run for a seat on Frederick’s Common Council in 1835. He met with success in the 1836 election, and was chosen to fill the seat of a deceased Council member in 1850. In each of the next five years, Whitehill was re-elected to the Council. In the 1862 election for Aldermen, he—and all the other Union Party candidates—won easily, for they ran unopposed, there being no “Rebel” party candidates. Talk of disunion disturbed Frederick citizens, inspiring a group of them to form a Union Club on February 11, 1860. They chose James Whitehill as their president. Soon every district within the county had its Union Club. Members of these clubs raised Union flags, sang patriotic songs, and pledged their loyalty to the Union.  The war years made normal civilian life difficult, if not impossible. Frederick endured the movements of and occupations by thousands of Federal and Confederate troops, especially during September of 1862, July of 1863, and July of 1864. Following the 1862 battles of South Mountain and Antietam, Frederick played a major role in caring for sick and wounded soldiers of both armies. Research shows that nearly all public buildings, including most churches, were converted into hospital wards, and James Whitehill’s Methodist Episcopal Church was not exempted. It, with the nearby Lutheran Church and Winchester Seminary (Frederick Female Seminary, now Winchester Hall), formed General Hospital #4. Between September 17, 1862 and January 17, 1863 over 900 men were treated in this hospital complex. In addition to seeing his church used for war purposes, Whitehill saw his primary business change from the furniture manufacture and sale to the undertaking trade, with the establishment of an embalming station in his store. A broadside advertised an embalming station operated by Dr. Richard Burr, embalming surgeon for the United States Army, with its office located at “Jas. Whitehill and Co.’s, Undertakers, E. Patrick Street.” In addition to undertaking, James Whitehill provided coffins, wooden headboards, and hospital furnishings to General Hospital #1 located in and around the Hessian Barracks on the south side of town.  Union Hospital #1 on the Barracks Grounds on South Market Street (today the site of Maryland School for the Deaf). Below is a depiction by local artist Richard Schlecht of burial at Mount Olivet Cemetery during the Civil War. Many of Mr. Whitehill's coffins made during the Civil War are in the ground here in Confederate Row. Again, thanks to the Historical Society of Frederick County and in particular, Joyce Cooper and her incredible research, allowing me to tell you the rest of the Whitehill story and how it pertains to Mount Olivet Cemetery, and Halloween. In 1867, the Whitehills moved from their East Patrick Street home to a large house on the west side of North Market Street at Eighth Street. The home is located at 731 N. Market Street and was originally built by Hiram Winchester, female seminary principal and namesake of Winchester Hall (Frederick County's seat of government). Winchester sold this to Whitehill for $4,550, a hefty price for the time. The house became the Frederick City police station and jail in the mid-fifties and remained so until 1982. In December, 2016, this building was opened as the Frederick Rescue Mission’s “Faith House,” a temporary shelter for homeless women and children. James Whitehill experienced poor health in his final years. An article from February, 1874 gives us a glimpse of the condition he found himself in. His health further declined in the ensuing months. James Clemson Whitehill died on July 13th, 1874. He was buried in a fine funerary crypt In Mount Olivet built into the southeast side of Cemetery Hill (also once referred to as Pumphouse Hill). His funeral occurred on July 15th and it can be assumed that it was well-attended.

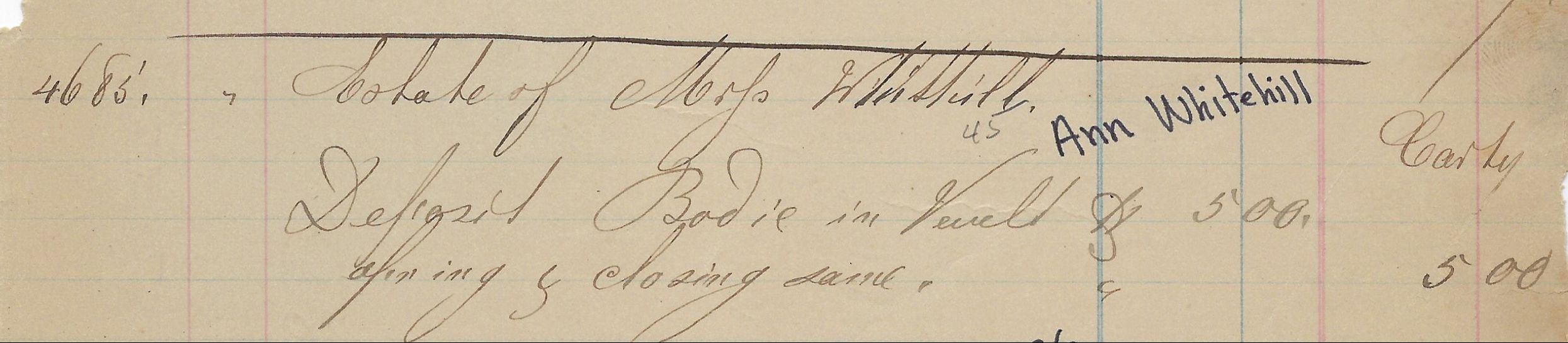

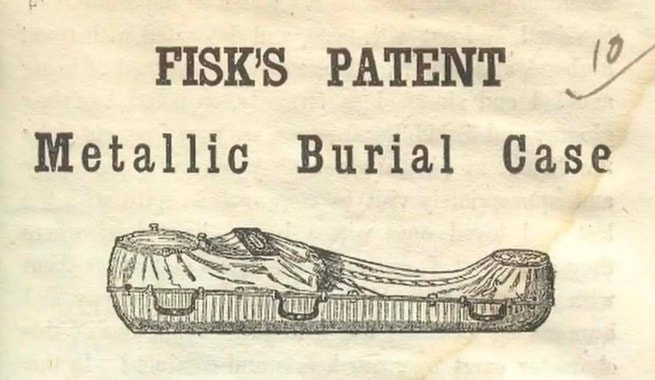

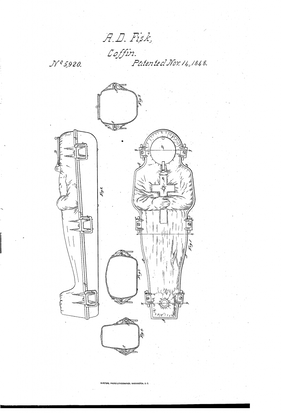

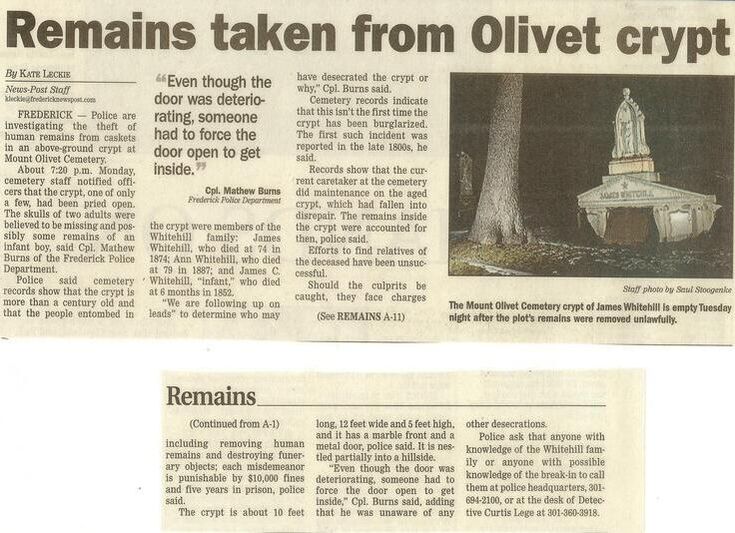

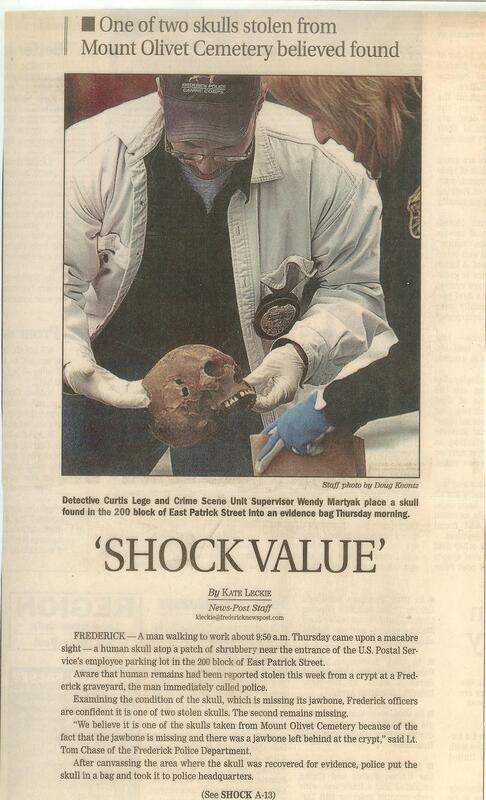

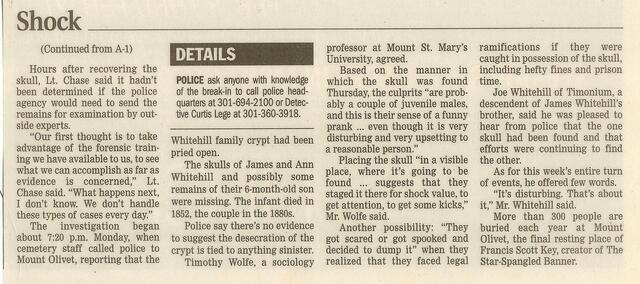

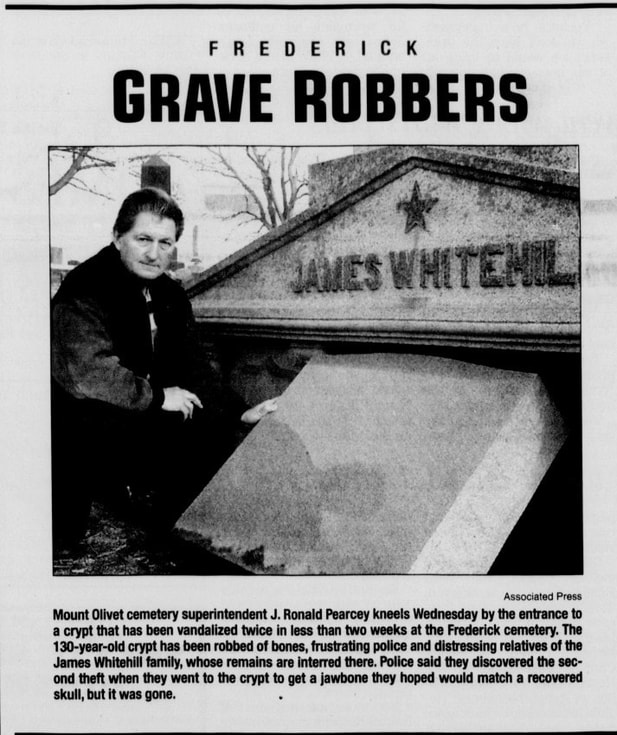

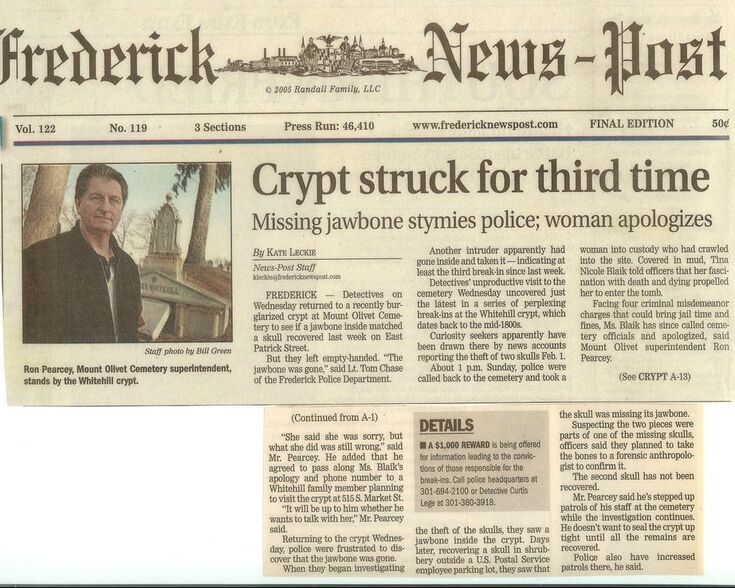

Ann Whitehill would pass on April 8th, 1887. The cause of death was the same given as her late husband-—heart disease. So that was that, the Whitehill family was resting in peace—but even this age-old cemetery-centric cliché could be deemed “debatable.” There is a strong suspicion that the crypt was a victim of “grave-robbing” in the late 1890s or early 1900s. Although we have no official records of this occurring in Mount Olivet, these criminals were stealth-like in their attempt to steal jewelry off corpses in cemeteries around the country and world. Crypts (like the Whitehills) were appealing because there was no digging to be done, and you didn’t have to go “subterranean” for the heist.  While I’m on the unpleasant subject, another type of graveyard crime in “days of old” was “body snatching.” This was an even more despicable situation as thugs actually took bodies from their intended grave lots. Why, you may ask? Well, for educational purposes of course. Early medical schools were in desperate need of cadavers. They paid quite well, and didn’t ask questions. I can practically guarantee that we never had a case of “body snatching” in Mount Olivet’s history, but I can’t give the same surety for the other early burying grounds in downtown Frederick or surrounding countryside. I guess we will never know. (NOTE: add here devilish laugh sound effect followed with “ ba ha ha”). Grave robbery on the other hand could have occurred in earlier days, and actually would in 2005. And yes, our friends the Whitehills and their crypt in Area F were the victims of such a dastardly thing, perhaps more than once. Our superintendent of 53 years, J. Ronald Pearcey, says that he recalls the iron door on the Whitehill crypt never seemed 100% secure since the time of his own arrival on staff back in the 1960s. The top hinge had been jarred from its setting in marble, and the upper part of the door near this junction seemed to have been somewhat bent, as if having been pried open at some time by use of a crow bar or like instrument. Ron said that he tried to fix the hinge back in 1997. The opportunity came about as Ron was performing intensive research in updating cemetery records. Apparently, he had no record of Mrs. Whitehill’s actual burial here in our cemetery record books. He decided to visit the crypt and take a glimpse inside to survey the contents. In our possession at that time was a “skeleton key” (pardon the pun) that opened the Whitehill crypt door lock. Ron made multiple discoveries that particular day as he found the lead coffin of infant James Campbell at the foot of the crypt, just behind the entry door. In front of him, he saw two metal coffins on the concrete base floor, placed longways, from left to right, in front of him. He assumed that Mr. Whitehill, who died first, was placed in the back/rear and that the matching coffin in front was that of Mrs. Whitehill. The couple possessed metallic Fisk-brand coffins, which Whitehill had advertised in the newspaper back when he owned his funerary business. These were unique caskets, made of metal and featuring a glass “porthole” in which one could view the decedent’s face. Fisk metallic burial cases were patented in 1848 by Almond Dunbar Fisk and manufactured in Providence, Rhode Island. The cast iron coffins or burial cases were popular in the mid–1800s among wealthier families. While pine coffins in the 1850s would have cost around $2, a Fisk coffin could command a price upwards of $100. Nonetheless, the metallic coffins were highly desirable by more affluent individuals and families for their potential to deter grave robbers. Ron commented that the coffins were in a stage of deterioration, rusting and the lids somewhat collapsed. He said that his brief observation showed that the bones of these bodies had been somewhat disturbed, not truly matching up to how they should be if left alone. A fourth coffin was also in this crypt, off to the right, and placed lengthwise across the foot of the Whitehill coffins. It was a wooden coffin in a far worse deteriorating condition. Research in our records showed this to be the body of Elizabeth (nee Schade or Schaed) Tice, a former tenant of Mr. Whitehill who died on October 25th, 1863. Mrs. Tice was born on May 27th, 1780, and was the wife of George Tice, a tailor, who had died in December, 1831. Mrs. Tice’s husband, son Henry (d. 1839) and a four-year-old grandson are buried in the old German Reformed graveyard, currently under the various war monuments of today’s Frederick Memorial Park. A check of 1850 and 1860 census records shows Elizabeth Tice as a next-door neighbor to the Whitehills when they lived on East Patrick Street and ran their furniture business. This finding was an extra bonus for Ron in his record research. Upon completion, he and staff members did what they could to further secure the door when they closed the crypt back up. Obviously, this would not be enough, however. Ron told me that, at the time, he sensed there had been a prior disturbance of some kind as the caskets didn’t seem to be neat and orderly as he thought they ought to be. This led staff to believe that the crypt had fallen prey to an earlier break-in, but it had not been thoroughly ransacked, rather carefully combed through. I have searched early newspapers and cemetery records, but came up empty in my search for documentation of any early events (19th or 20th century) relating to grave intrusion here at Mount Olivet involving the Whitehill crypt. I could see a situation of this nature downplayed and not reported to authorities in an effort to keep the peace with relatives and lot-holders. As we learn with incidents of vandalism in cemeteries, there is a strong feeling of violation felt by not only staff but all who have a loved one in a particular burying ground, even if just one gravesite has been tampered with or defaced. Twice Bitten Early Monday morning of January 31st, 2005, Ellie Summers and Liz Claggett, regular walkers in our cemetery, made a horrible discovery. They found bones strewn about on the small knoll in front of the Whitehill crypt. It had snowed during the overnight, and the ladies also saw the door to the crypt was wide open. They immediately made their way back to the front of the cemetery and notified Superintendent Pearcey. Pearcey immediately went to the site with another staff member, our current cemetery foreman, Tyrone Hurley, and saw what had been reported to them—the crypt door had been fully pried open, and the display of bones had indeed come from the Whitehill crypt. Ron then notified the authorities who came out to make a report and investigate. The group saw nearby car tracks and footprints in the snow outside the cemetery’s only other crypt belonging to the Roelkey family. It appeared that someone had been pulling on the outer gate of this funerary repository, but were frustrated in their vain attempt. The thought prevailed that the culprits hit the Whitehall crypt before the snow had started falling, and then attempted to raid the Roelkey crypt as the precipitation had started accumulating. Because of the snow forecast, Superintendent Pearcey left the gates open so that staff could enter early in an effort for snow removal. Back at the Whitehill crypt, Tyrone was sent into the structure to assess the damage. He reported that the glass portal on each coffin appeared to have been smashed, and the boxes themselves had been raided of some of their human contents. Tyrone and Ron carefully retrieved the remains and placed them back in the broken deteriorating coffins within the crypt. Unfortunately, they realized that both skulls and a jawbone were missing from the scene. Ron and Tyrone closed the door the best they could, with hopes of doing more the following morning as they had to put their energies toward plowing the 3-4 inches of snow covering the cemetery lanes and roadways. The next day word got out through the initial police report, and a media-circus ensued with news entities from Baltimore and Washington wanting to cover the unfortunate Whitehill crypt break-in. Superintendent Pearcey was interviewed by newspaper and television reporters throughout the day. The crypt entrance way was now blocked by the placement of an extra piece of granite found in one of our storage areas. News Channel 5 (out of Washington) did a live remote report from the cemetery that Tuesday night, and CNN had a team up here as well to do the same. On Wednesday, February 2nd, the Frederick News-Post would run the following story: While the Frederick City Police were conducting their investigation, a unique find occurred near downtown Frederick’s Post Office. The story would make front page news in the February 4th edition of the Frederick News-Post. The Whitehill break-in made other newspapers across the area including Baltimore, Annapolis, Hagerstown and Cumberland. The Associated Press picked up the story and it ran in various publications throughout the country. The Washington-Post would also interview Ron about the unfortunate vandalism, now thought to be the work of juveniles. The following Sunday, February 7th, brought a new and equally unsettling wrinkle to the story. Late in the afternoon, Superintendent’s Pearcey's son was driving through the cemetery in late afternoon and noticed a lady entering the Whitehill crypt. He immediately notified his father. Here is the newspaper story related to this aspect: And just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water....this was the front page of the February 10th Frederick News-Post: The following day, Ron and his grounds staff worked to fully secure the Whitehill crypt. The Police were still searching for the lone missing skull and jawbone, as the other had been returned to the crypt. Meanwhile, no remains of the Whitehill infant had been removed as erroneously reported in the papers. Fill dirt was utilized to further build up the ground around the crypt’s door, and the granite slab was turned on its side and packed-in tight against the door. The 600-pound marble slab was remains intact since that day. The good news, there have been zero instances of vandalism here at the Whitehill crypt, a true positive. On the downside, however, the missing skull has never been located and returned to its rightful burial tomb. Ironic in a way, as many residents of Mr. Whitehill’s day described the prominent businessman and politician as progressive, stubborn and headstrong. Maybe it’s time to remove the last adjective?

1 Comment

LORETTA JECELIN.

10/31/2020 11:16:35 pm

My Father's parents bought a home a few miles down from the cemetery around the time world war II ended. I grew up there and my father continued to live there until 1995. My grandmother who was his mother is buried in the cemetery. During the years we were there when I grew up it was all farmland. Grandmother's husband died leaving her widowed for many years. I have photographs of back in those days. Our home was where the parking place is now for the hike and bike trail just off of executive boulevard. When I was a child at one end of the road was a sign that said cemetery road which is now known as New Design Road. There is lots I can tell you about the area during the 50 years my family lived there. THERE IS ALSO A FEW QUESTIONS I AM CURIOUS ABOUT CONCERNING AND ADJOINING PROPERTY. THIS MIGHT MAKE AN INTERESTING STORY FOR YOU.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed