|

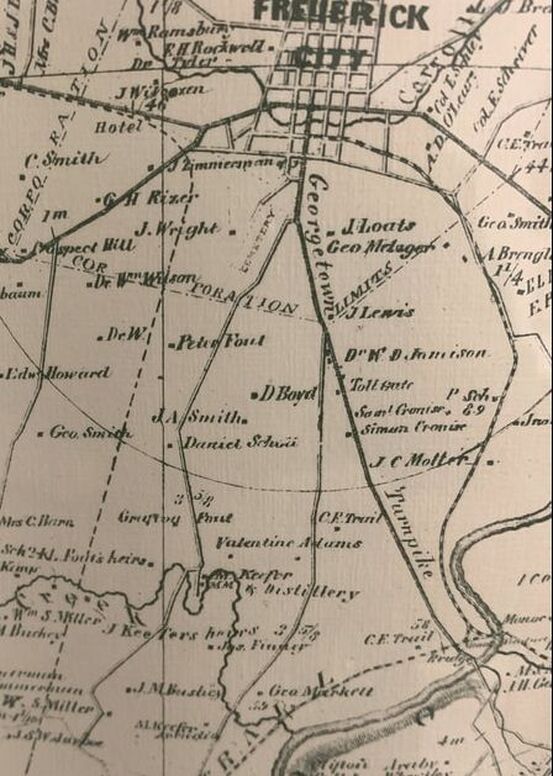

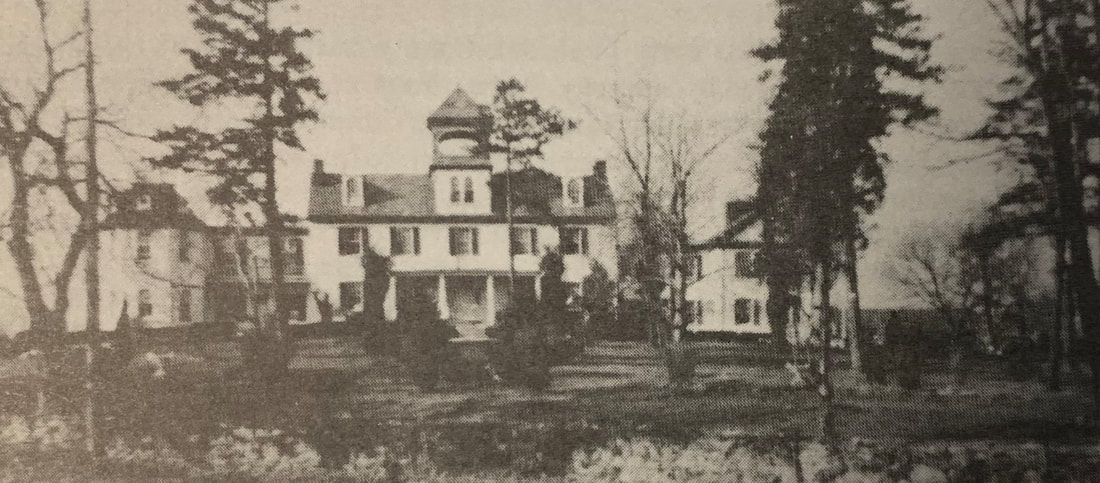

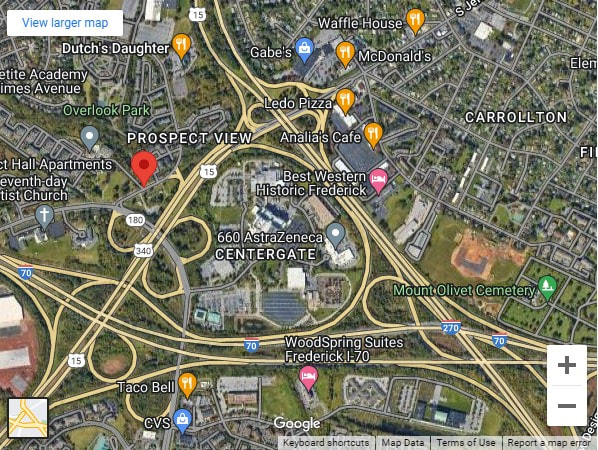

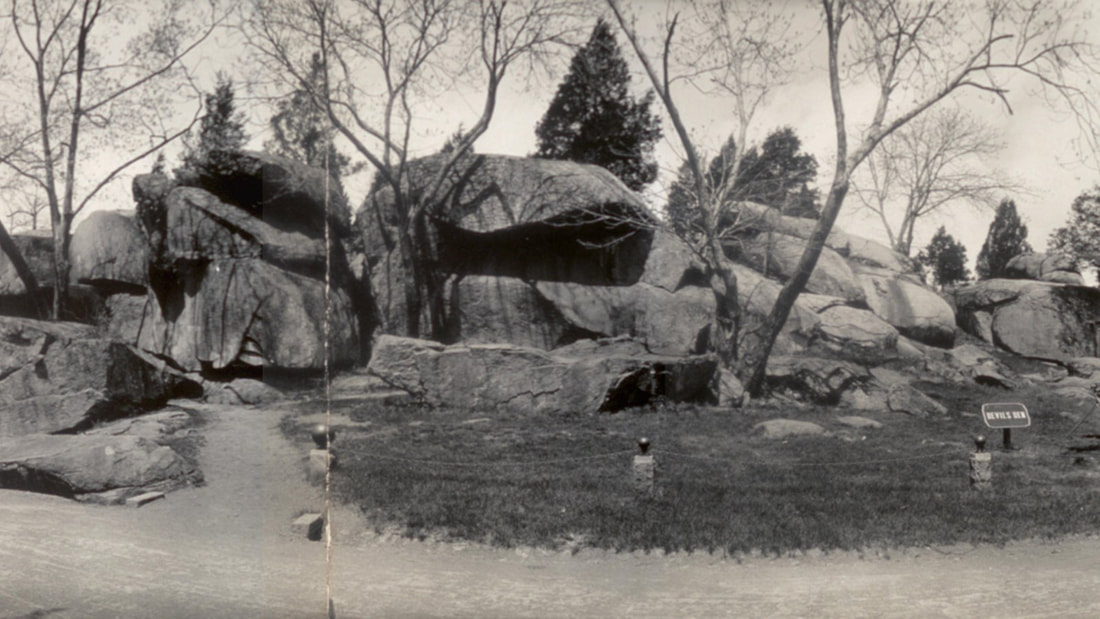

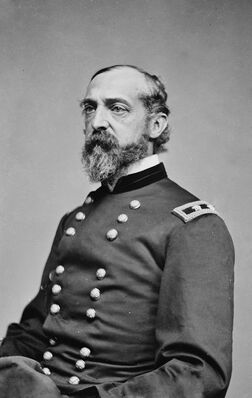

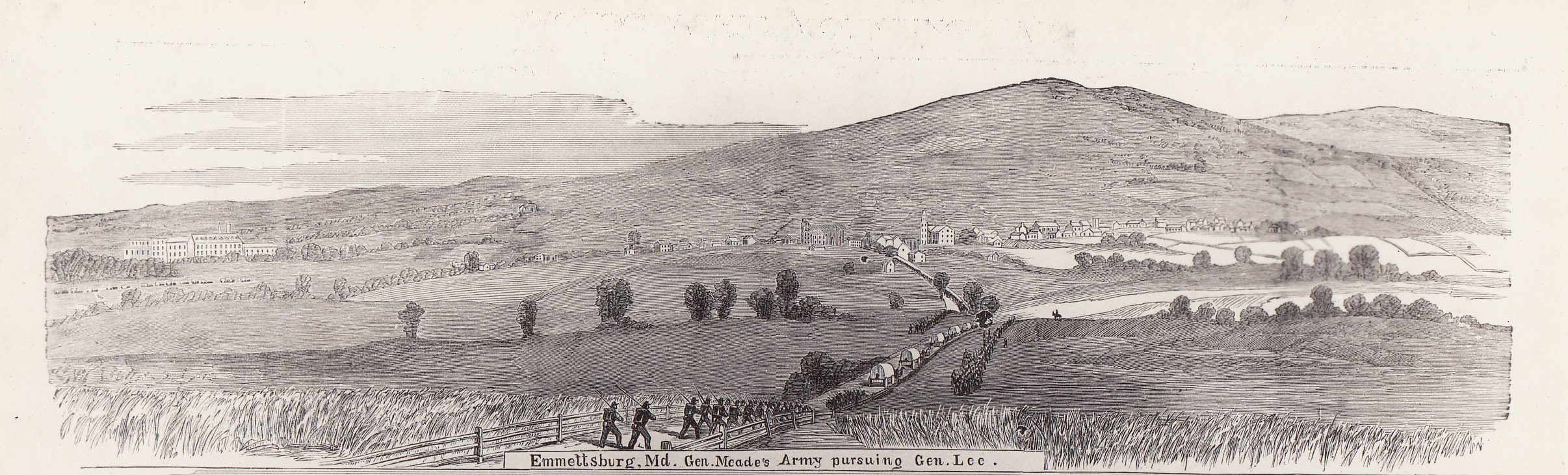

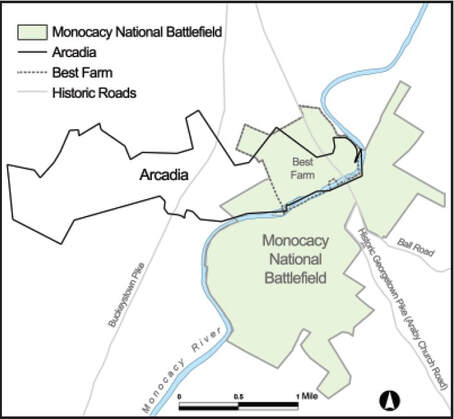

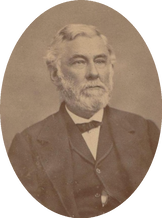

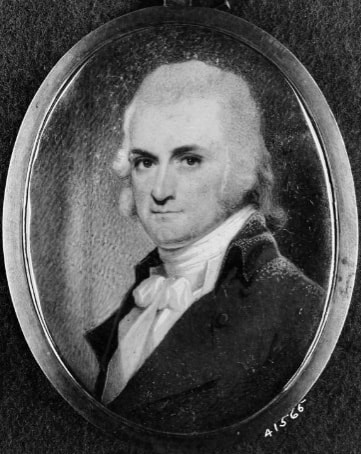

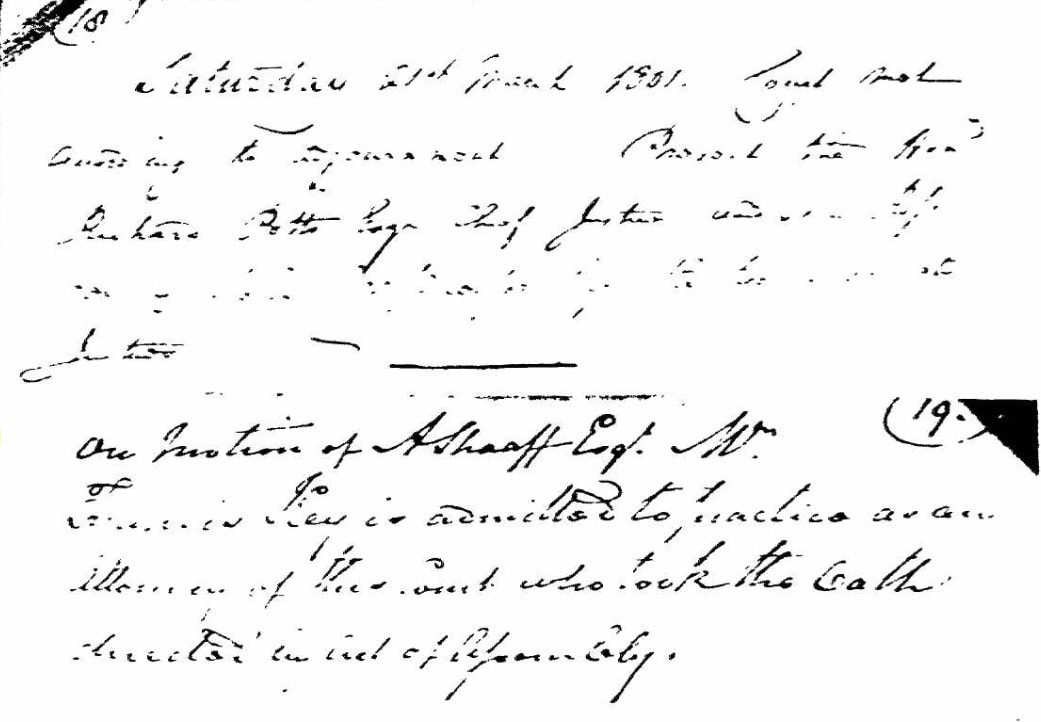

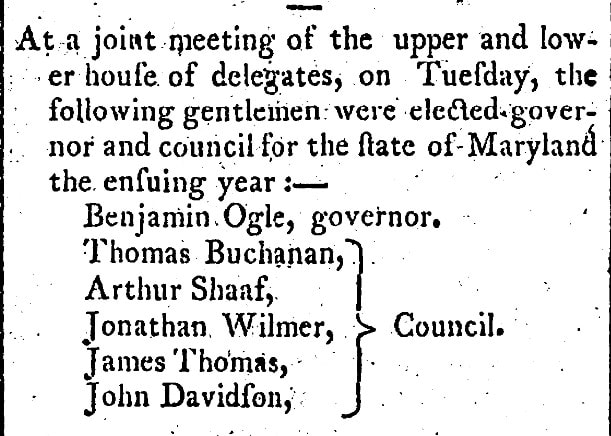

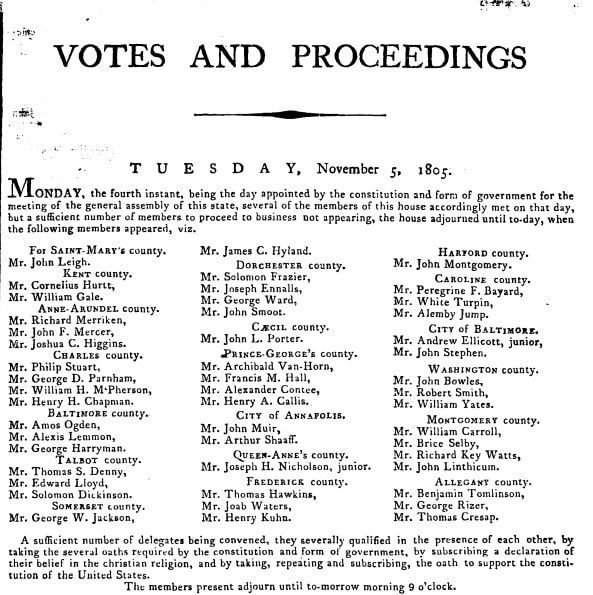

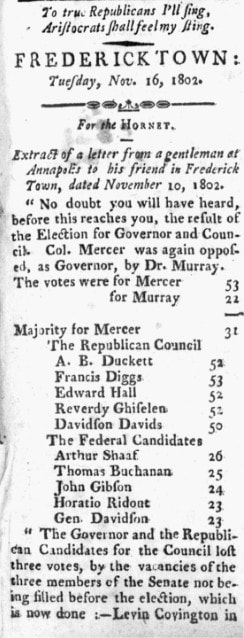

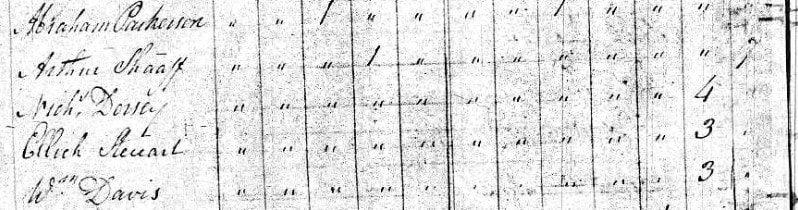

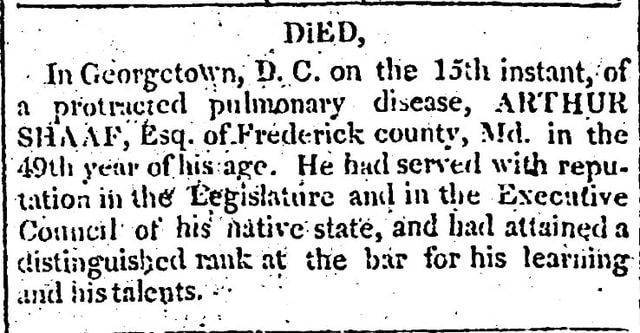

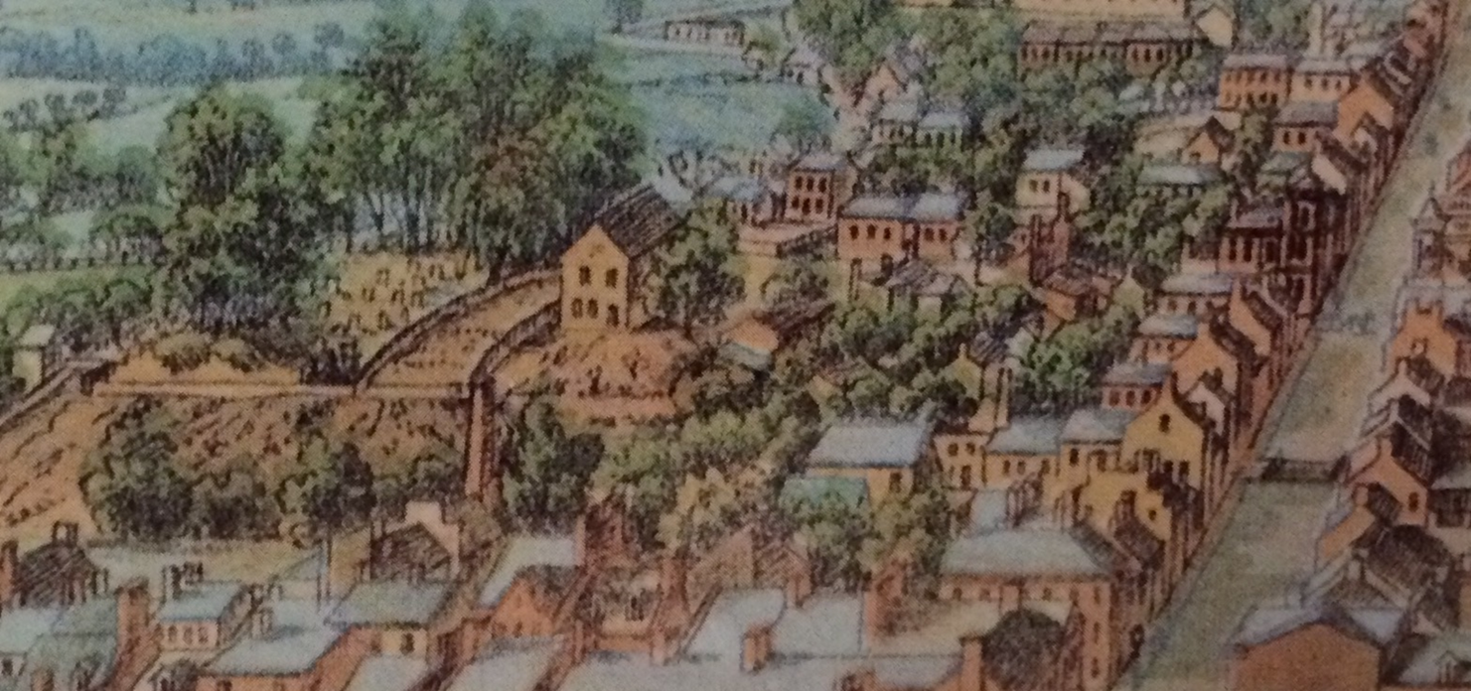

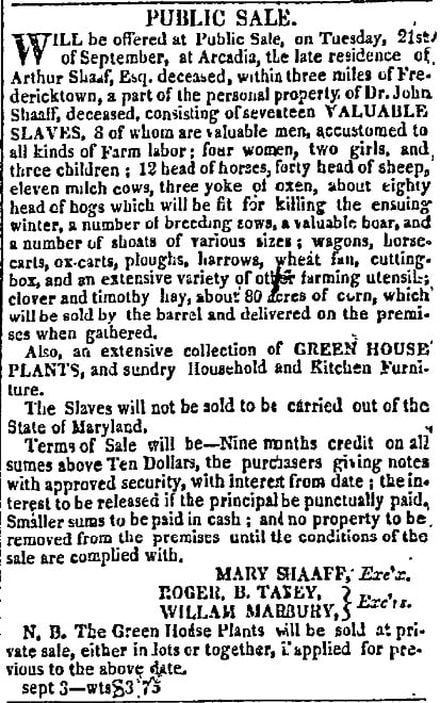

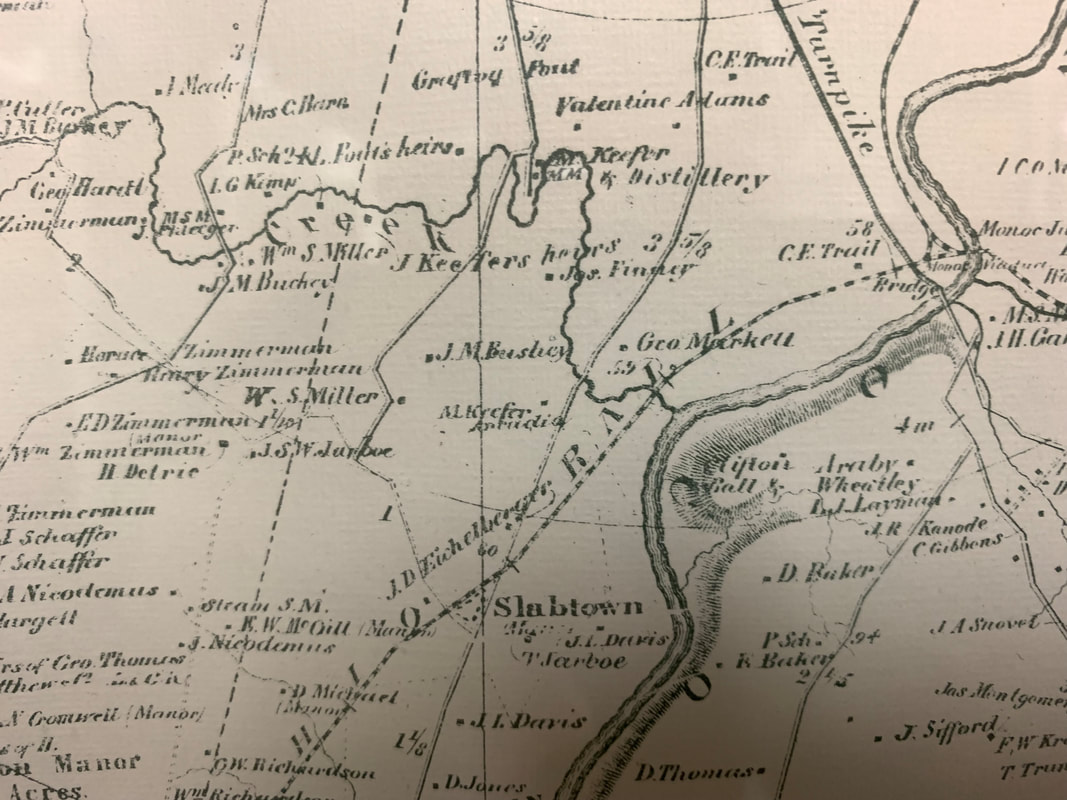

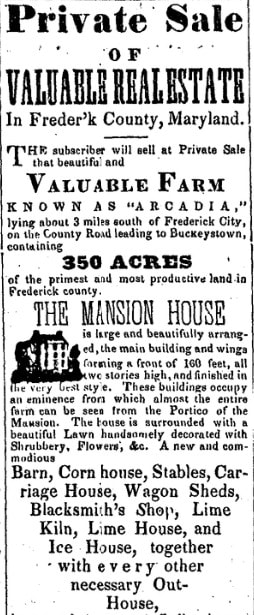

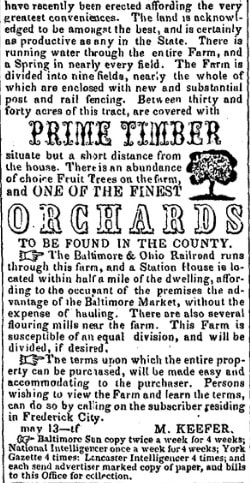

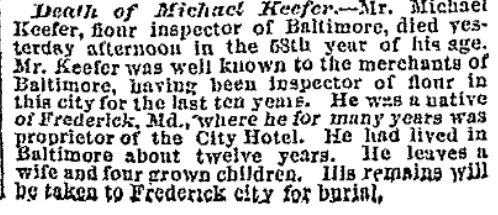

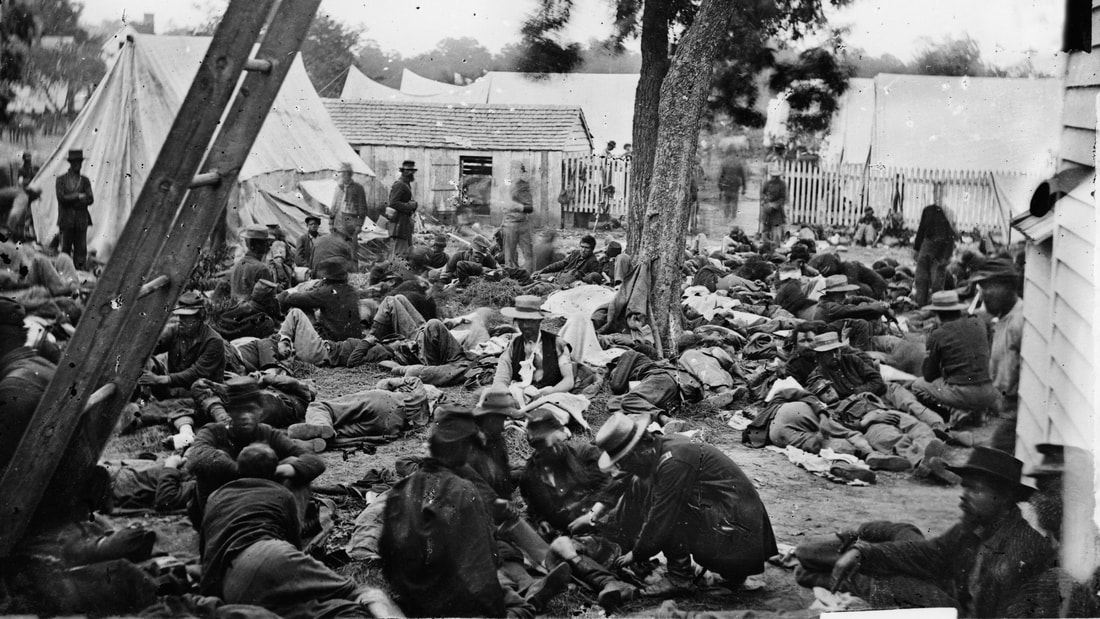

Anyone who reads this blog on a regular basis knows that I am no stranger to a wide variety of monuments and gravestones, and the “stories” behind them. As a matter of fact, rocks (primarily of granite and marble) are the “basis” of this ongoing “Stories in Stone” series. However, our interest in rocks is centered on history and geneaology instead of geology and the science that deals with the earth’s physical structure and substance. An interesting point to make here is that rocks last forever. With the assignment to represent the “physical footprint” of a human being, place or event, the memory (of said person, place or event) should last equally as long as “the rock,” shouldn't it? That’s what memorialization is all about, and why gravestones and monuments hold value to those of us who care about learning from things from our past. Going back even earlier in time, before the recording of history by cultures, we study rocks to understand early peoples and the planet itself (ie: Native American spearpoints, monadnocks like Sugarloaf Mountain, Stonehenge and petroglyphs). As we near the end of June, I can’t help but think about a unique, local specimen that proves my “point of rocks” serving as solid, lasting reminders. This particular one captures a legendary event from Frederick’s past that did not occur on Mount Olivet’s property, but was in very close proximity from a geographic sense. Years ago, this locale would have been reached by a short walk of about 500 hundred yards from my office at the cemetery. This would be similar to a walk from the back of Mount Olivet to our front gate on South Market. These days, with residential, commercial and transportation growth over the last century, getting there requires greater effort, and is best made by automobile. I’m talking about “the Gen. Meade Change of Command Monument” at Prospect Hill. Considered to be on the outskirts of southwest Frederick, the “Change of Command” monument is often missed. It is located along Himes Avenue at the foot of the hill and service road leading up to the Prospect Hall mansion, formerly the site of St. Johns Regional High School. The marker’s visibility and accessibility have improved greatly in recent years thanks to the Civil War Trails program in which wayside interpretive markers have been placed next to the rock in question, which had previously been partially hidden by shrub growth, and difficult to access by automobile. The granite monument marks the vicinity where the command of the Union Army of the Potomac passed from Gen. Joseph Hooker to Gen. George B. Meade on June 28th, 1863. This was done by order of President Abraham Lincoln at a critical time during the American Civil War. The significance of this event was not known at the time, as just days later, Gen. Meade would be engaged in the most famous battle ever to take place on American soil, perhaps only rivaled by Lexington & Concord or the Battle of Yorktown of the American Revolution. This is not a native rock to Frederick, but fittingly hails from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. More specifically, it comes from the infamous “Devil's Den” on the battlefield. For those not familiar, Devils’ Den is a boulder-strewn hill on the south end of Houck’s Ridge below Big Round Top. On the second day of battle (July 2nd, 1863), “the Den” was skillfully used by Confederate artillery and sharpshooters to shoot at the commanding Union position above on the ridge. Why don't we bring science into this story this week, just for fun. The Gettysburg National Military Park website gives readers the following geologic background on the rock composing Devil's Den and our local monument : Approximately 180 million years ago during the late Triassic Period, the Gettysburg Formation comprising sandstone, siltstone, and shale was deposited in a large carved-out basin in the Gettysburg area. These lowlands were broken by hills and ridges that were formed as a result of geologic activity when a dense 2,000-foot thick slab of igneous (molten) rock called the Gettysburg Sill and also two 50-foot dikes were thrust into the Gettysburg Formation. One of the dikes underlies Seminary Ridge in a north to south orientation while the other parallels the ridge to the west. Sills are responsible for the topographically-high areas of the Round Tops, Culp's Hill, and Cemetery Ridge and Hill. The intrusion dikes are composed of very fine-grained, dense diabase rock very resistant to weathering. The composition of these rocks indicates that the molten masses cooled very rapidly. The Gettysburg Sill is coarse-grained diabase, an igneous rock otherwise known as granite. The Sill also contains a large amount of feldspar. Two bronze plaques are attached to a granite boulder. The first plaque marked the original dedication in 1930, and the other is from the re-dedication in 1963 as part of the American Civil War Centennial activities.  1963 "Change of Command" plaque unveiling and 100th anniversary commemoration with three known attendees to the right of the monument. These include (L-R) E. Lease Bussard (Chairman of the Frederick Centennial Committee), unidentified woman, Judge Edward S. Delaplaine (noted historian/author), and Sen. Charles McCurdy "Mac" Mathias. From natural history, let's return to American history. Gen. Meade formally assumed command of the Army in the dining room of Prospect Hall on June 29th, just two days before the fateful Battle of Gettysburg. Gen. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker was the Union Army General who succeeded General Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac in 1863, despite his grandiose notions of becoming a dictator. He had a reputation for being aggressive in pursuit of war, women, and liquor. Interestingly, Gen. Hooker is best known for having his name attached to the female camp followers—the first “hookers” of record. Prospect Hall has a much richer history than simply this singular event in the Civil War. I hope to talk about other episodes involving Prospect Hall in future stories involving various former owners dating back to the 1700s. Prospect Hall may not as durable as a rock or boulder down the hill, but we are blessed to have such a historical “monument” still standing.  The area directly below Frederick City is depicted here from the 1858 Isaac Bond Atlas map. Note "Prospect Hill" (location of Prospect Hall where Hooker had his headquarters in June, 1863) in the upper left. To the southeast of Prospect Hill (at the center-bottom of this image), you can see labeled "M. Keefer-Arcadia." This is where Meade had made his headquarters in late June, 1863. Another interesting part of the “Meade Change of Command” story involves another “structural witness to history.” This landmark mansion can be found still standing a few miles to the southeast of Prospect Hall. This is known as Arcadia, and you may have driven by it before while on Buckeystown Pike. Or perhaps you’ve heard of it because its name has appeared in the news a great deal of late because it may be demolished. Arcadia is important to local history for a variety of reasons. In particular, for our recounting of the “change of command,” this property is part of our larger story as it is the location where Gen. Meade was encamped when he learned the news of his military promotion. The order for a change of command from President Lincoln was carried by Gen. James A. Hardie, a 40-year-old West Point graduate who served as Secretary of War Edwin Stanton's Chief of Staff. According to the account by Judge Edward S. Delaplaine in the souvenir program issued on the occasion of the centennial anniversary of the war, the messenger arrived from Washington at the train station on South Market among a throng of Union soldiers in the streets of Frederick: "Hardie made the journey in mufti (civilian clothes). In Frederick he heard that Meade's headquarters was located near the Harper's Ferry road about a mile from the city. Hiring a buggy and driver, he made his way at night with difficulty past army wagons and crowds of soldiers, reaching Meade's tent on Sunday, June 28 at three o'clock in the morning.” Meade took command reluctantly because he was concerned about changing leaders in the middle of a campaign. Additionally, he felt his longtime friend Gen. John F. Reynolds was more capable and more deserving of the assignment. Gen. Meade described his appointment in a letter back home to his wife Margaret: "At 3:00 a.m., I was aroused from my sleep by an officer from Washington entering my tent, and after waking me up, saying he had come to give me trouble. At first, I thought it was either to relieve me or arrest me.... He then handed me a communication to read; which I found was an order relieving Hooker of command and assigning me to it.... As a soldier, I had nothing to do but accept and exert my utmost abilities to command success... I am moving at once against [Confederate Gen. Robert E.] Lee, who I am in hopes [Gen. Darius N.] Couch will at least check for a few days; if so, a battle will decide the fate of our country and our cause." Meade's prediction proved true. Just hours after his promotion, the general found himself with little to no time to calculate his next moves. During the day of the 29th, he moved the Army of the Potomac forward (and northward) towards the enemy. By that evening, Gen. Meade had established his headquarters in Middleburg, Maryland. He wrote again to his wife: “We are marching as fast as we can to relieve Harrisburg, but have to keep a sharp lookout that the rebels don’t turn around us and get at Washington and Baltimore in our rear. They have a cavalry force in our rear, destroying railroads, etc., with the view of getting me to turn back; but I shall not do it. I am going straight at them, and will settle this thing one way or the other. The men are in good spirits; we have been reinforced so as to have equal numbers with the enemy, and with God’s blessing I hope to be successful. Good-by!”  Jim Hueting in front of Prospect Hall Jim Hueting in front of Prospect Hall Both armies would soon be fully engaged on the farm fields and woods surrounding Gettyburg for the first three days of July, 1863. This would be the turning point of the Civil War, and Meade had found himself in a much different situation from when he had laid his head down to go to sleep in his tent beside peaceful Ballenger Creek at Arcadia just a few days earlier. If interested, please take a look at the following blog by Gettysburg Battlefield Guide Jim Hueting made back in 2009. He has some excellent photographs of Arcadia and Prospect Hall to help frame the scene of that fateful night Meade took command. Arcadia The word arcadia is defined as “a region or scene of simple pleasure and quiet.” I guess this was also the marketing message of National Bohemian beer, which was brewed and enjoyed “in the land of pleasant living” here in Maryland? The Arcadia mansion and former manor site is located between Frederick and Buckeystown. The extensive plantation, in its original form, included land stretching eastward across the Monocacy River. The manor house is said to have been erected around 1790, or the years immediately after. According to histories of Frederick, the mansion was the meeting place of the local gentry who gathered to play cards, dance, race horses and fox hunt. History books from the early 20th century make comment that, “the splendid mansion is one of the finest in Western Maryland. It is of colonial style and is situated on a high rolling elevation, surrounded by all kinds of beautiful trees and flowers. This estate is one of the best country homes in the county.” Today the house overlooks adjacent Buckeystown Pike (MD Route 85) and offers a commanding view of the surrounding area including Monocacy National Battlefield, in the distance to the east. Arcadia was extensively altered in the late 19th century, and now possesses an elaborate balconied tower. The interior was also extensively updated at that time as well. Historians and architectural experts agree that Arcadia is significant for its historical associations and as an interesting mix of architectural features which have made it a bonafide local landmark. The house played other roles during “the war between the states” in addition to hosting Gen. Meade and his soldiers in late June, 1863. Ten months earlier, in September, 1862, Confederate colonel (later general) William N. Pendleton stayed at Arcadia. This was during the Antietam Campaign and Pendleton was certainly no stranger to Frederick. He was actually a former resident, having served as rector of the city’s All Saints Episcopal Church from 1847-1853. He left town in a huff after resigning his post due to a dispute with the church vestry. He had urged the vestry to build a new church to replace the aging facility on Court Street. They refused, at least until after he left town. The new church would go under construction later that decade and front on West Church Street. In 1864, Arcadia was utilized during the Battle of Monocacy. It actually encompassed the Best Farm at one point of time (as the map above shows). Rebel Gen. Jubal Early formed his troops here to cross the Monocacy and go into battle. Arcadia would also serve as a makeshift, field hospital for wounded Confederate soldiers during the famed “Battle that Saved Washington.” There have been a number of owners of Arcadia over the years as you can imagine. I’d like to highlight a handful that are buried here in Mount Olivet. First off, there is Arthur Shaaff, credited with originally building the mansion along (Henry) Ballenger's Creek south of town. Arthur Shaaf Arthur Shaaff was born in Frederick County on October 7th, 1768 and died on May 15th, 1817. Named for his grandfather, Arthur Charlton, he was the son of Caspar Shaaff (?-1799) and Alice Charlton (b. 1743-1775). Mrs. Shaaff was the daughter of Arthur Charlton (1722-1771) and Eleanor (Harrison) Charlton (1723-1770), well-known tavern operators in Frederick’s past. Caspar Shaaff and Alice Charlton were married in November, 1759. The couple had four children: Mary, John Thomas, Arthur, and Caspar. The Charlton family was of English descent and arrived in Frederick County during the early eighteenth century. They had direct ties to the Keys of Terra Rubra. Caspar Shaaff was of German descent and worked as a merchant and carpenter. In 1754, Shaaff (also found to be spelled Shaaf and Shoaf) acquired 275 acres of land surveyed originally for Joseph Chaplaine under the name of "The Resurvey on Exchange" in the vicinity of Fox’s Gap atop South Mountain. During the period 1757-1758, Caspar Shaaff filed legal petitions in the local court to collect debts owed to him. He is shown as head of household in Frederick County in the 1790 US Census. It is thought that he lived here locally in 1796, because Mr. Shaaff assisted in settling his mother-in-law, Mrs. Eleanor Charlton's estate. In 1797, Caspar Shaaff of Frederick Town was appointed "agent for the late Daniel Dulany, in the counties of Montgomery, Frederick, and Washington, to accept rents, etc." Caspar’s son, Arthur Shaaff, could be found living primarily in Annapolis by century’s end. He had become a prominent lawyer in Maryland, and would play a role in the early careers of two other Frederick esquires. Shaaff practiced law in Frederick, Annapolis, and Hagerstown. Roger Brooke Taney identified Arthur Shaaff as one of the prominent and distinguished members of the Maryland Bar when Taney, himself, was a law student in Annapolis between 1796-1799. Taney recalled Shaaff as a mentor and a colleague. He (Taney) prepared cases both with Arthur Shaaff, and opposing the gifted attorney.  Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) Taney related that Shaaff assisted him when he moved to Frederick City in 1801 to practice law. "Mr. Shaaff, who still practiced in Frederick, having invited me to take part in one of his cases, in order to give me the opportunity of appearing in public.” Arthur Shaaff’s practice included real estate management, property disputes, property transfers, and estate settlement. In some cases, Shaaff, Roger Brooke Taney, and a cousin, Francis Scott Key, collaborated. I’ve been under the impression for years that the fabled joint law office of Taney and Key, once found in Courthouse Square (and fronting Court Street), was actually the law office of Arthur Shaaff. In 1806, Roger Brooke Taney married Ann Phoebe Charlton Key, the sister of Francis Scott Key, and became a cousin by marriage to Arthur Shaaff. Shaaff’ s mother (Alice (Charlton) Shaaff) was sister of Ann Phoebe Penn (Charlton) Key—the mother of the Key siblings, Ann Phoebe Penn Dagworthy (Charlton) Key and Francis Scott Key. Like he had done with Taney, Arthur Shaaff is credited with presenting young Francis Scott Key to the Frederick County Court, and moved for his admission to the bar. The formal ceremony was noted as follows in the records of Clerk William Ritchie: “On motion of A. Shaaff, Esq., Mr. Francis Key is admitted to practice as an Attorney of this Court who took the Oath directed by Act of Assembly.”  Wide view from Council St giving contect. Faux Law office to the right of historic brick house (denoted by marker) and original Shaaff, Taney, Key office was to the left of said house. The three story, duplex with dormers was built in the early 1900s in keeping with the guidelines of the Historic Preservation Commission several decades before there even was a designated historic district in Frederick. It's just too bad we lost the original dwelling, which prompted the "building/labeling" of the faux office for tourism sake not unlike the rebuilt Fritchie House. Historian William Jarboe Grove (1854-1937) wrote in his “History of Carrollton Manor” of 1922: "In the summer, Mr. Taney would sometimes retire, with his family, a few miles from Frederick to Arcadia, the country-seat of the eminent lawyer Arthur Shaaff, a bachelor, and a cousin of Mrs. Taney, to recruit his overtasked mind in the serenities of the country.” Although Arthur Shaaff practiced law in Frederick County, he was not recorded in the 1800 and 1810 censuses as residing in Frederick County. His primary residence was in Annapolis, Maryland. However, Shaaff also was not recorded in the Annapolis census data for 1800. The 1800 census listed his brother John T. Shaaff as head of household in Annapolis, Maryland. The household contained 2 free white males between the ages of 26 and 44 (presumably John T. and Arthur), one free white female between the ages of 26 and 44, and seven slaves (U.S. Census 1800). By 1810, both Arthur Shaaff and John T. Shaaff were listed as separate heads of household living in Annapolis. Arthur Shaaff died on May 15th, 1817 at approximately 49 years of age. He would be buried in All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal Cemetery, originally located between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. On September 30th, 1854, one of Mount Olivet’s founding board members, Richard Marshall, handled plans to re-inter Shaaff’s body in newly opened Mount Olivet Cemetery. Marshall was a leading lawyer in town, and formerly mentored by Roger Brooke Taney. Marshall also moved the bodies of Mrs. Ann Taney and her parents (Ann and John Ross Key) to the south end of his lot. This gravesite was originally known as the Marshall Lot, but is now better known as the Potts Lot, as the Marshall’s married into this family. The Arcadia Mansion and associated property were inherited by John Thomas Shaaff, the elder brother of Arthur Shaaff. John T. Shaaff was a doctor by profession who practiced in Annapolis. He was the Treasurer of Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland from 1799 to 1801 and a member of the Governor's Council from 1798-1800. He moved his practice to Georgetown after 1810. While in D.C., he served as the Vice-President of Columbia Institute and was a founder of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia in 1819. When John T. Shaaff died on May 3rd, 1819, the executors of his estate were his wife Mary Shaaff of Georgetown, William Marbury of Georgetown, and Roger Brooke Taney of Baltimore. (Frederick Examiner 1851, July 23). In 1826, the executors of the estate of John T. Shaaff sold Arcadia to Col. John McPherson (1760-1829) of Frederick for $29,000. McPherson transferred the property to teenage grandson John McPherson Brien (1807-1850), who transferred the property to his father, John Brien (1766-1834)in 1833. In 1835, the estate of John Brien sold the property to Col. Griffin Taylor, described as a large slaveholder living the lavish "southern plantation lifestyle" and incurring debts that required him to sell off sections of the property. William Jarboe Grove referenced account books containing gaming debts that were found in the attic by later owners. In the 1850 census, Taylor was recorded with 18 enslaved persons. In 1851, Mr. Taylor offered his real and personal property for sale stating that he intended to remove to the West. A footnote on Col. Taylor is that he relocated to Cincinnati, but died four years later in October, 1855 and was laid to rest in St. Johns’ Catholic Cemetery in Frederick. The estate was described as containing 1,015 acres and was offered as a single farm or for subdivision into three or four farms. The estate contained three dwelling houses, as well as Arcadia Mansion where Col. Taylor resided. The mansion was described as a large brick house with "wings handsomely finished, and the gardens and grounds about the house are handsomely laid off and improved with evergreens". Griffin offered the mansion with about 280 acres as one farm. Frederick resident Jacob Engelbrecht reported in his diary entry of September 9th, 1851 the sale of Arcadia Farm and Mansion by Griffin Taylor to Michael Keefer for $18,000. At the time, Keefer (1815-1876) was the proprietor of Frederick’s City Hotel on West Patrick Street. In 1858, Michael Keefer assigned his real estate, including Arcadia, and personal property to Edward Shriver to act as his trustee to sell advantageously at private or public sale to clear Keefer's debts. In October 1858, Shriver sold Arcadia, then containing approximately 338 acres, to Thomas and Cynthia Clagett. The deed was recorded in 1862. Both men are buried here at Mount Olivet.

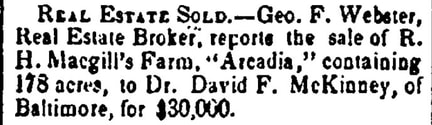

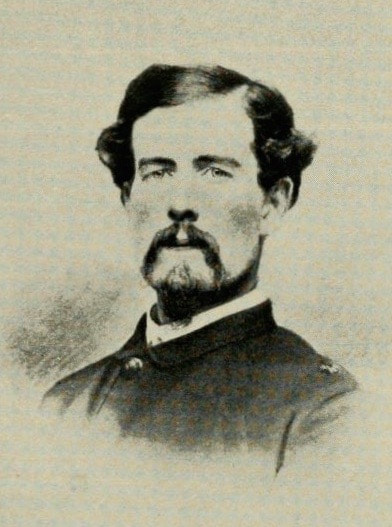

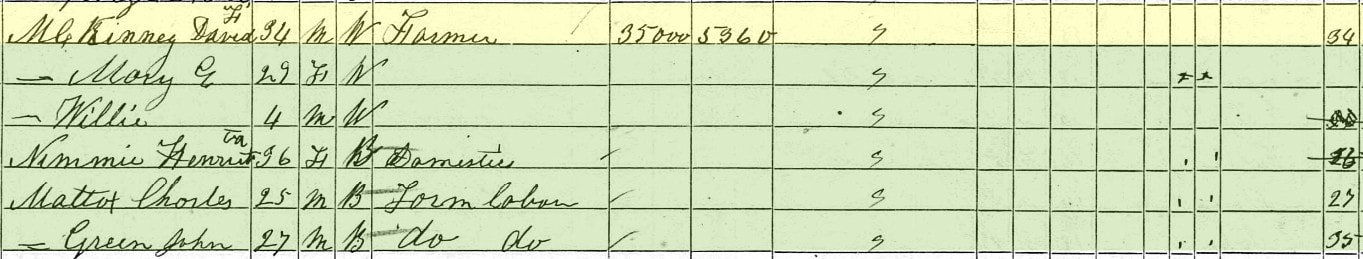

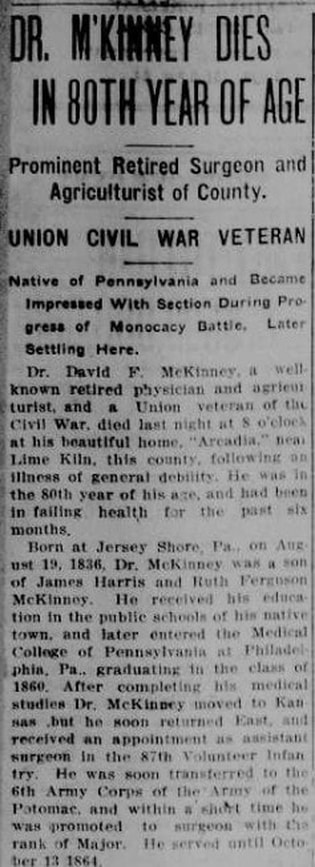

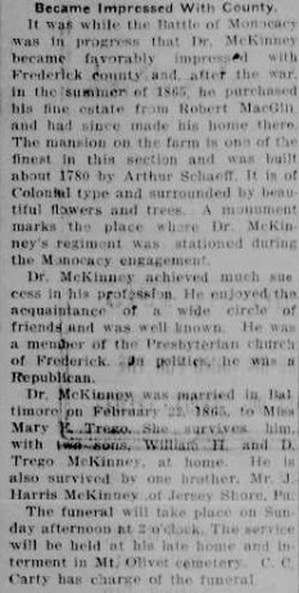

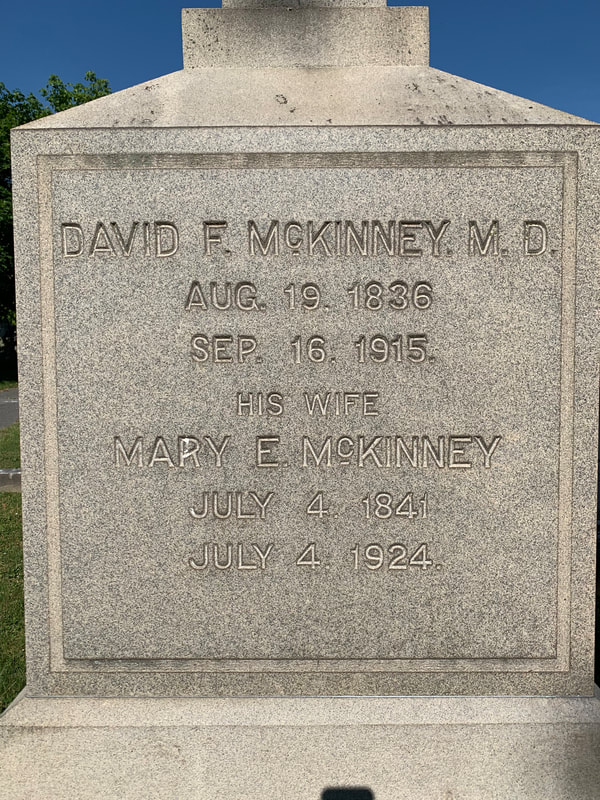

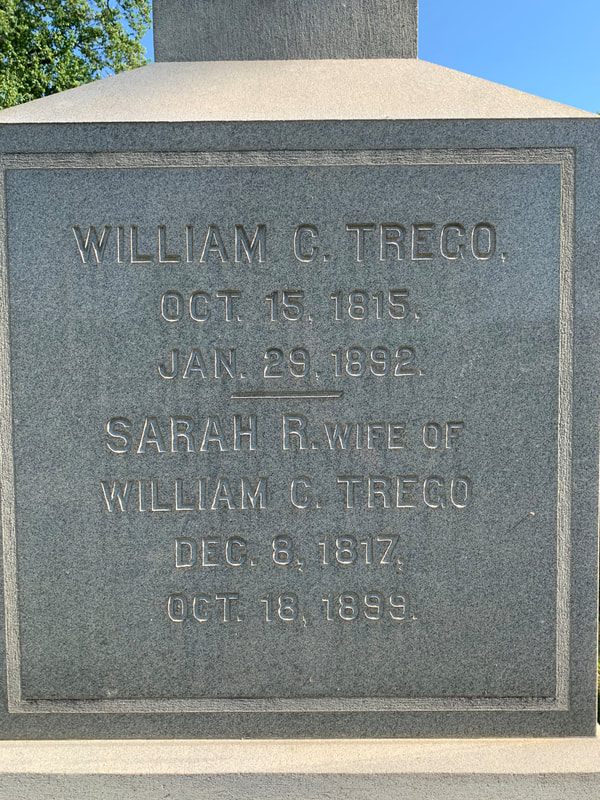

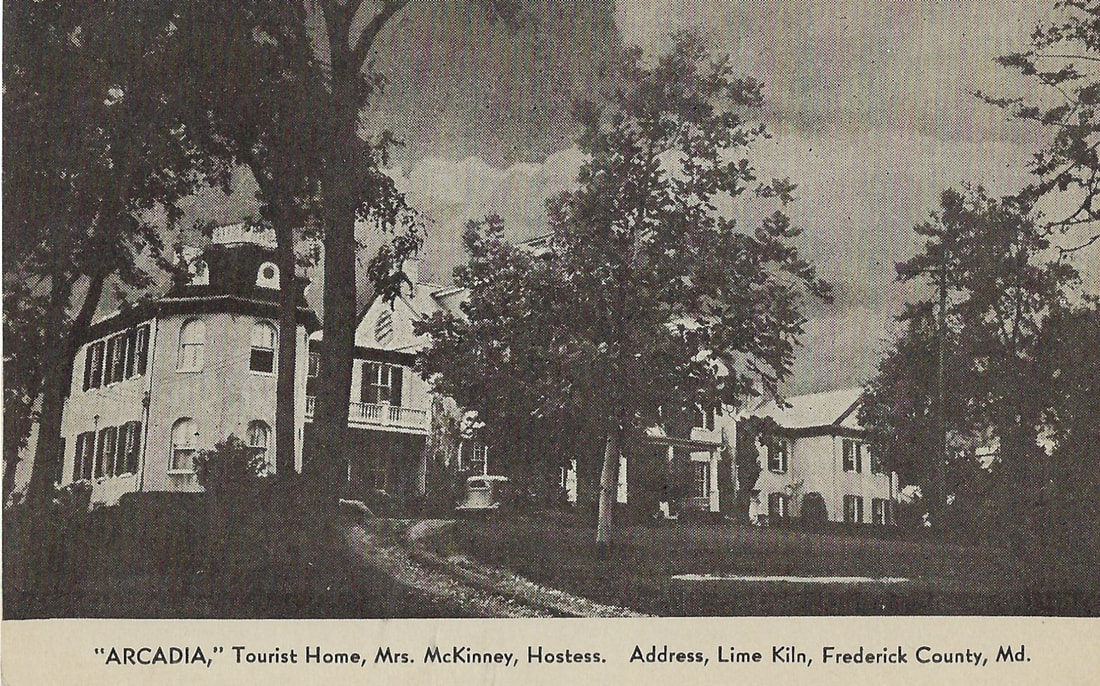

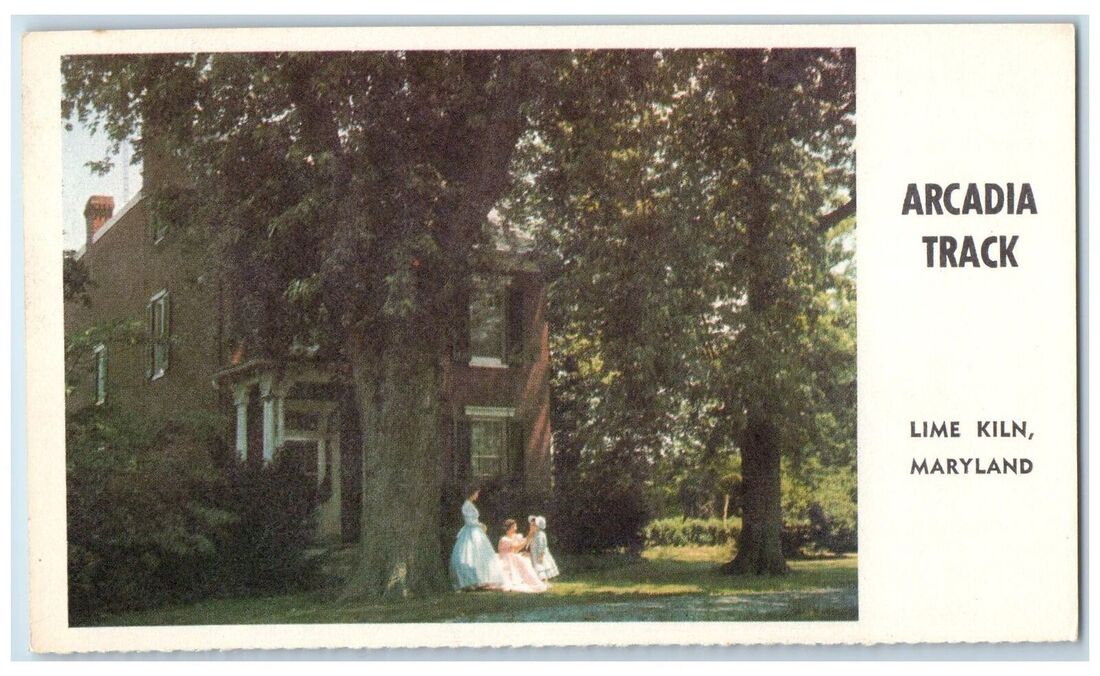

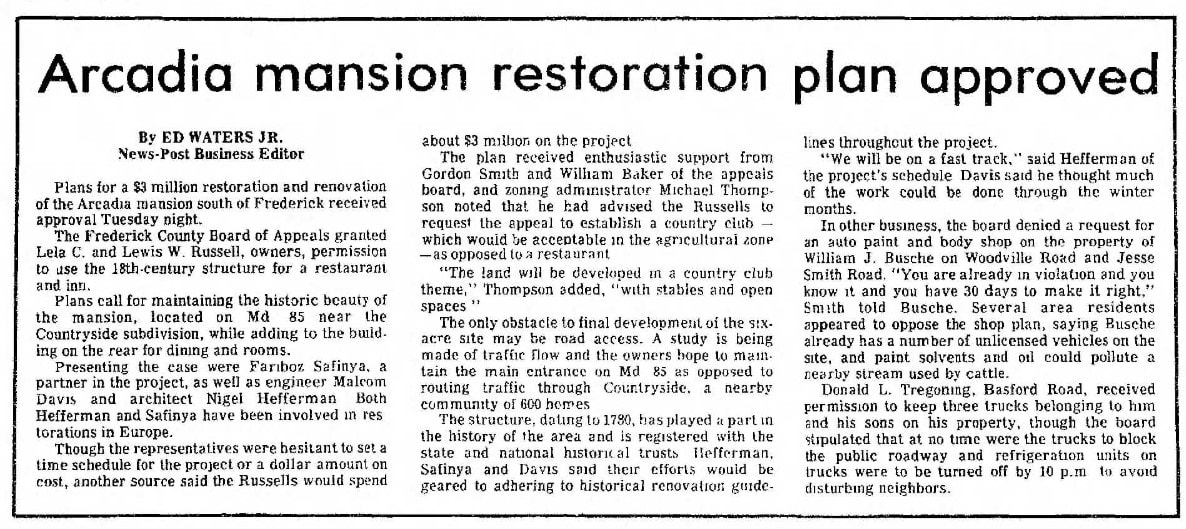

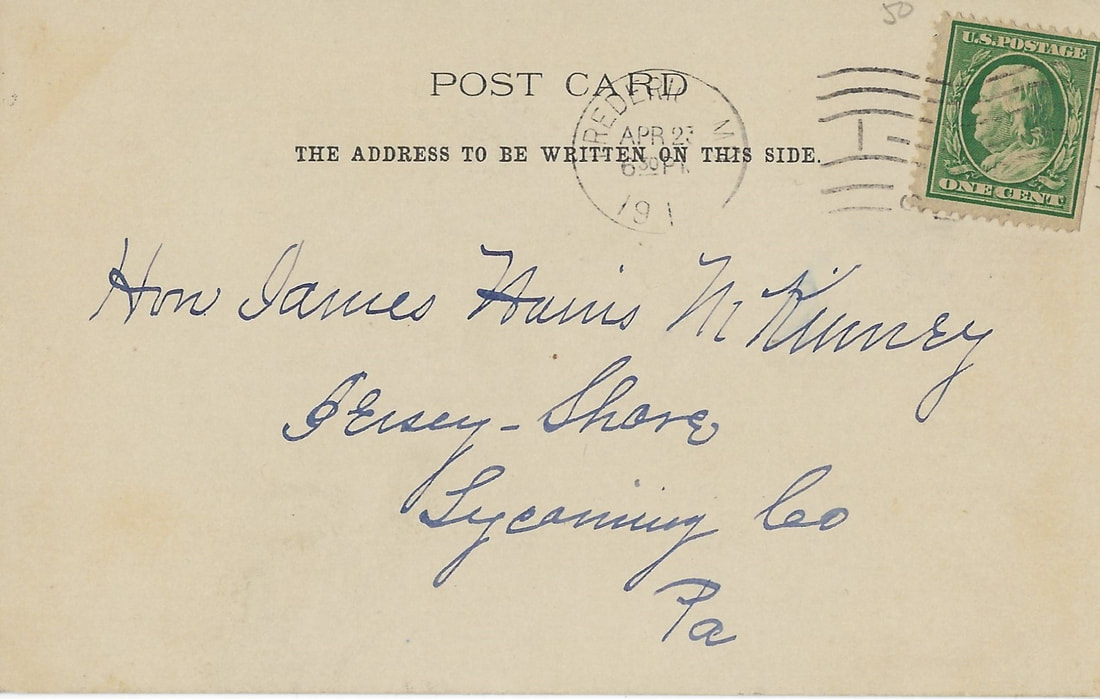

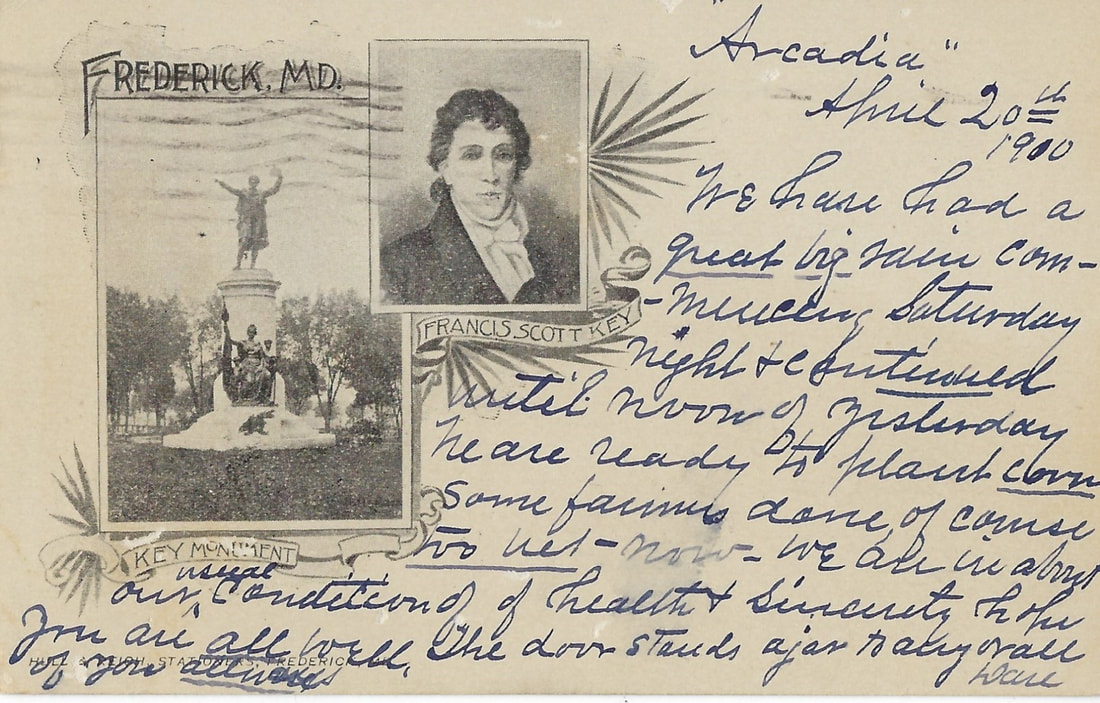

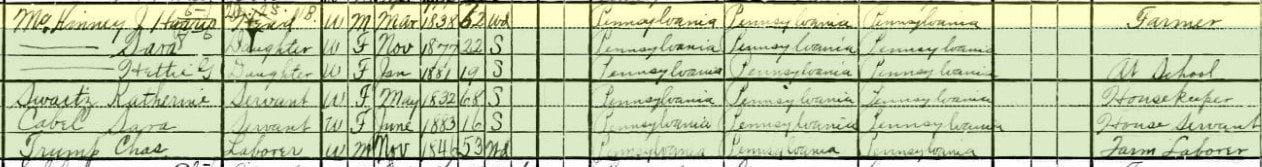

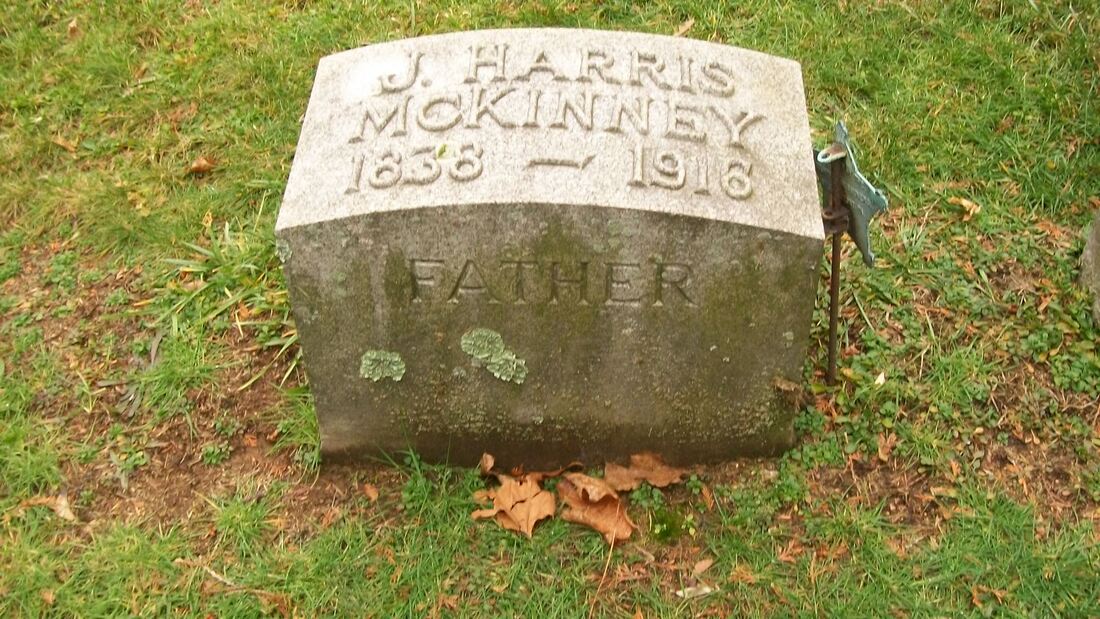

Thomas Clagett resided on a large estate near Kemptown and used Arcadia as a fox hunting retreat. In residence in 1860 were Thomas Clagett, age 22, with the occupation of farmer and a laborer, J. Dunloff, and 4 slaves. Mr. Grove recalled that his father lived at Arcadia under Clagett's ownership and boarded his son. In 1862, Thomas Clagett sold Arcadia Mansion and 210 acres of land to Robert Henry MacGill, Sr. (1821-1876). He wouldn't be here for long, however. MacGill and McKinney It was Mr. MacGill who hosted Gen. Meade and the Union soldiers in late June 1863. A year later, William Jarboe Grove recalled that, as a ten-year old boy, he watched the ambulances bringing Confederate wounded from the battlefield. His father was pressed into service to carry stretchers. Arcadia was used as a temporary field hospital, with operations conducted in the central room on the first floor. While Confederate wounded were taken to Arcadia, Union wounded were taken to another farmhouse nearby. That hospital, on the George Markell property, was under the charge of David F. McKinney, a surgeon with the 6th Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Dr. McKinney reportedly was so taken with the area that he purchased 277 acres containing the Arcadia Mansion in 1865 from Robert MacGill. McKinney continued to work as a physician in Frederick County and became an agriculturalist. Dr. David Ferguson McKinney was born in 1836 in Clinton County, Pennsylvania near Loch Haven. He was educated in public schools and received a degree from Jefferson College in Canonsburg, PA. He entered the Pennsylvania Medical College of Philadelphia and graduated in 1860. Soon after graduation, McKinney was appointed as assistant surgeon in the 87th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. He was transferred to the 6th Army Corps of the Potomac and was shortly thereafter promoted to surgeon with the rank of major. He served for three years and was discharged in October 1864. Dr. McKinney was married in 1865 and brought his new bride, Mary (Trego) McKinney, to live at Arcadia. The former Mary Trego (b. 1841) was the daughter of a successful iron manufacturer from Baltimore. David and Mary McKinney improved Arcadia Mansion during their tenure. It was reported that Dr. McKinney replaced the blood-stained floorboards in the first floor center room, the family’s dining room. The room had been used as the operating room when Arcadia was used for a short period of time as a Confederate field hospital. Other alterations that occurred were the raising of the one-story hyphens to two stories. William Jarboe Grove reported that "the north wing is as it was originally built except the two center rooms, a story was added by Dr. McKinney. The small rooms connecting the main and end wings were formerly one story high." The McKinneys added the viewing tower on the front of the east elevation of the building. The McKinneys would reside at Arcadia for half a century. Both David, who died in 1915, and Mary E. McKinney (d. 1924) are buried here in Mount Olivet Cemetery. They have one of the only surviving lots with marble "curbing" delineating their gravesite. A massive cross is the central feature with corresponding footstones for family members listed on the base of the cross. Here too are Dr. McKinney's Trego in-laws and his sons William and David who would assume Arcadia after his death. Both gentlemen would farm and manage the estate with their respective wives. I have a very nice collection of vintage Frederick postcards. In a thrift shop in Hagerstown, I found a few cards showing our Arcadia. I bought both. The first card talked of Arcadia serving as a tourist home near Lime Kiln with Mrs. McKinney as a hostess and appears to be from the 1930s/40s by the car in the driveway. I assumed this to be William McKinney's wife, Grace McSherry McKinney, and not Dr. McKinney's wife Mary (Trego) McKinney. The second card doesn't even look like the house in question, but I bought it anyway. It probably hails from the 1960s during the Civil War Centennial period. I would soon learn that the McKinneys began to take in tourists in the 1930s. Author Nancy Bodmer wrote in her Buckeystown and Other Historical Sites that this was "not only for monetary benefits but because they enjoyed sharing Arcadia with other people. One of the first to stay for the summer months was Miss Mary Neighbours, who was born in Buckeystown. In 1939 she came to Arcadia for a rest in the country from the hot and hectic Frederick. She stayed 27 years, leaving only when the house was sold. Hardly a night would go by that the rooms would not be occupied." In April 1966, heirs of the McKinney family sold 277 acres south of the mansion to a group of investors who would construct the Countryside development. The mansion and remaining land has been bought and sold many times over. Plans along the way have even included a country club, but that did not come to fruition. Years ago, I bought another old postcard on eBay, dated 1900, with the Francis Scott Key monument on its face. I was particularly interested in this card because it was actually written at Arcadia. The author was Dr. McKinney who signed his correspondence with “Dave.” It was penned on April 20th, 1900 to the former physician’s brother James Harris McKinney living in Jersey Shore, Pennsylvania (located in Lycoming County and nowhere close to the Atlantic Ocean). (Written Transcript) “Arcadia,” April 20th, 1900 We have had a big rain commencing Saturday night and continued until noon of yesterday. We are ready to plant clover. Some farmers done, of course too wet-now-We are in about our usual condition of health and sincerity. Hope you all are well. The door stands ajar to any or all of you. Always, Dave For good measure, I searched for James Harris McKinney and found his name in the 1900 Census and final resting place up in Pennsylvania. This is one of my longest stories to date and actually inspired by my acquisition of that antique postcard. Made of paper, it's a miracle it even survived and somehow started in the hands of David F. McKinney at Arcadia 123 years ago, was sent to Jersey Shore, PA, and wound up in my hands all these years later. This humble (and long) "Story in Stone" is not just a testament to several owners of a singular property that happened to be buried in the local cemetery.It's also not just about a beautiful mansion from Frederick’s past, that still survives. No, it’s much more than that—Arcadia is a common thread of Frederick’s history through hundreds of years, and and serves as a touchstone to legendary figures in our local and national history including Gen. George Gordon Meade, Roger Brooke Taney and Francis Scott Key. Those men, along with lessor known characters such as Arthur Shaaff, Robert MacGill and Dr. David F. McKinney, are long-gone as well. But steadfast Arcadia is still here, weathering the test of time, not unlike a rock formed millions of years ago. The home was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, and the subject of postcards throughout the 20th century. Many county residents would even refer to Ballenger Creek as "Shoaff's Creek," giving credit to the early builder of the mansion. Sadly, Arthur's surname has silently slipped away, but his mansion home has not. I know that Frederick County continues to grow, and progress does not stand still. However, as the name of the mansion suggests, I pray that the parcel and beautiful house located at 4720 Buckeystown Pike remains untouched, and like a gravestone in a cemetery, has the opportunity to continue standing as a testament to the owners and events of the past as a reminder of “a region or scene of simple pleasure and quiet.” AUTHOR'S NOTE: Key sources of information were compiled in the Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historical Properties Survey Form (Inventory No. F-l-172) and Nancy Wilmann Bodmer's "The Past Revisited: Buckeystown and Other Historical Sites" published in 1990. The latter is where the early period image comes from.

3 Comments

Russell Poole

6/27/2023 09:04:44 am

Great story, as always, Chris! Fascinating details about long overlooked Frederick history. May you keep providing these detailed incites about our area for many years to come! - Russ

Reply

Russell Poole

6/27/2023 09:07:07 am

....of course that should have read "insights" but, thanks to the "miracle" of modern technology, spell check rendered it as "incites" at the last second!

Reply

James Nee

6/27/2023 02:26:23 pm

The old house in the second postcard still stands along the road to the prison, across Rt. 85.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed