|

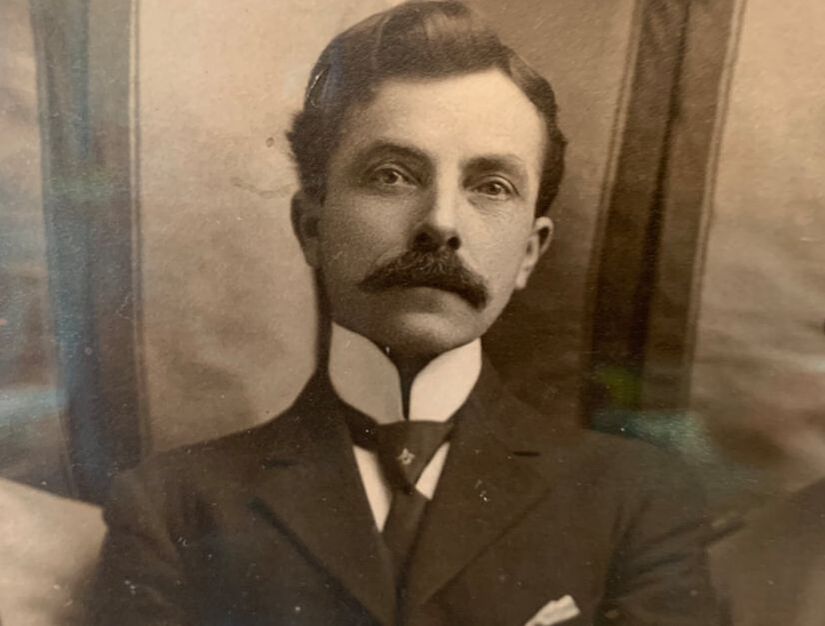

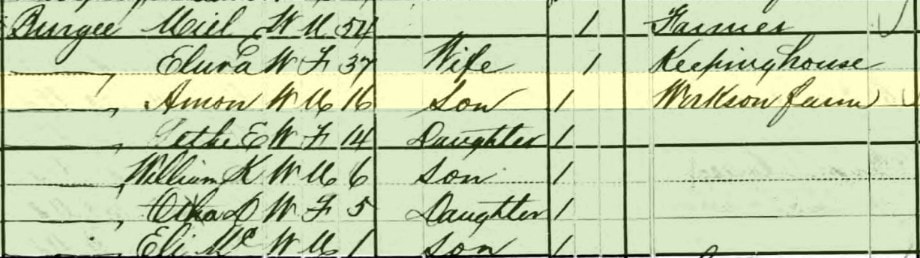

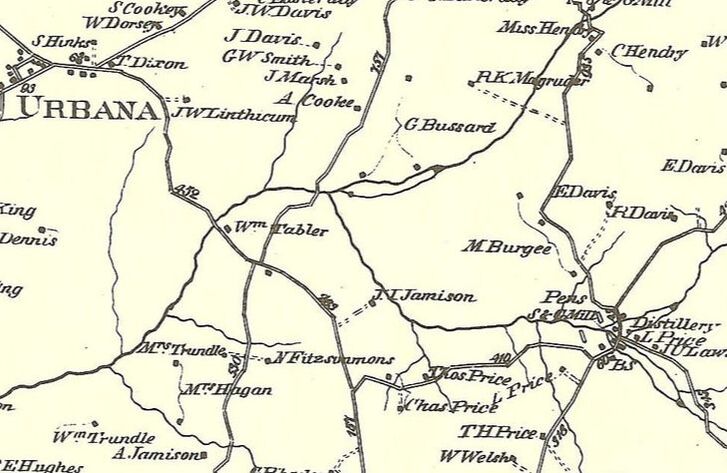

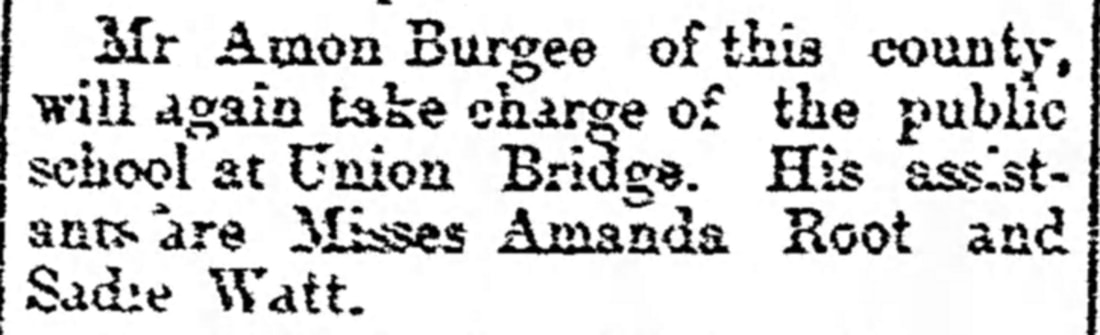

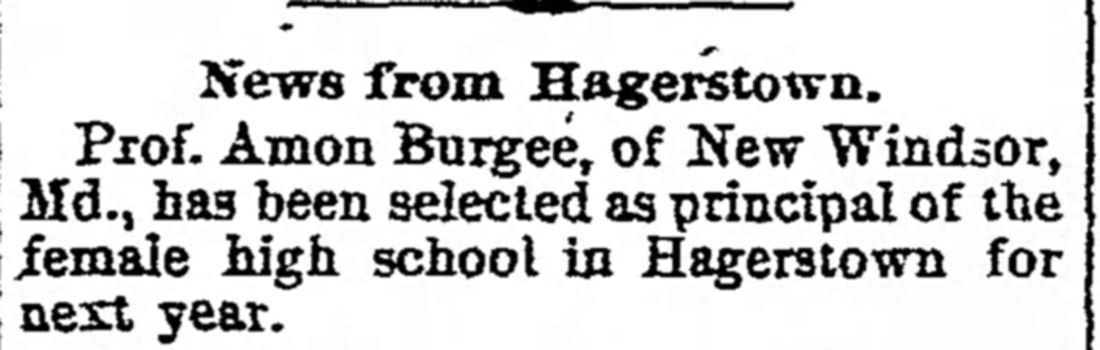

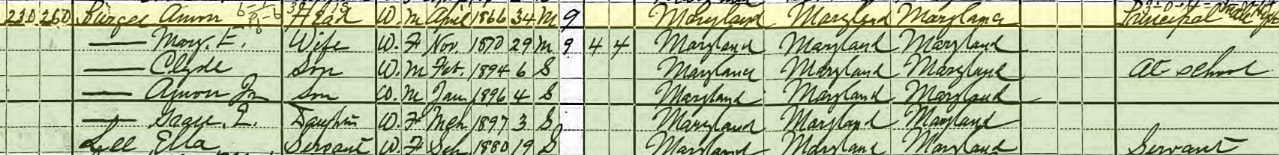

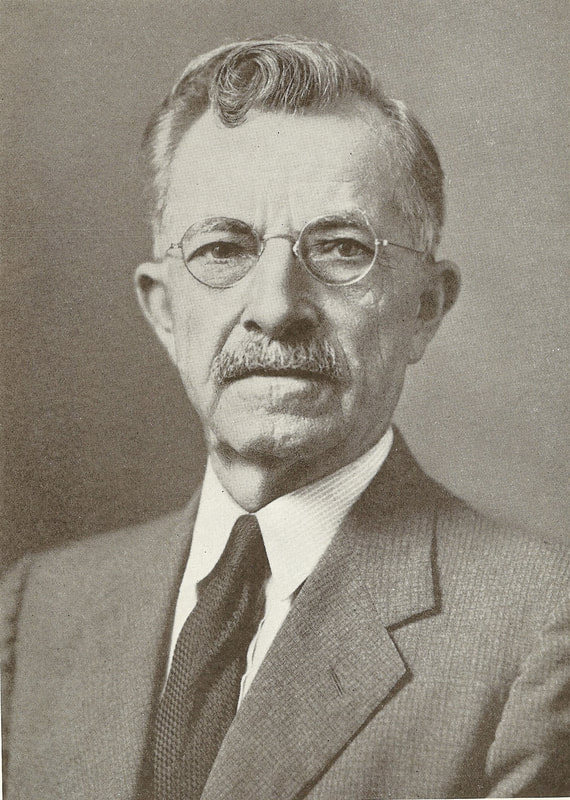

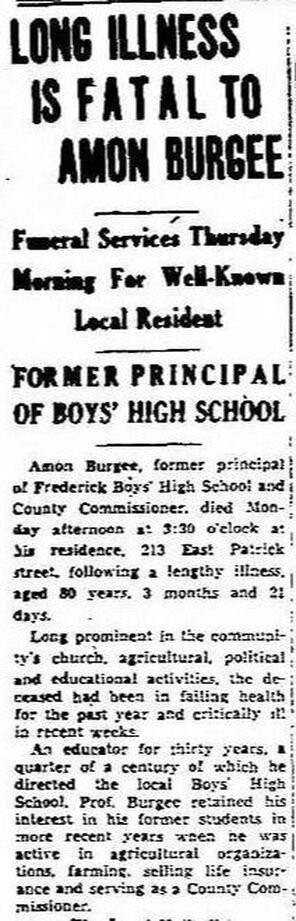

Another school year is complete, kids ranging from kindergartners to college students now find themselves having what seems like an everlasting summer in front of them. It’s a hedonistic existence which could include staying-up late (and “sleeping-in”), vacations, camps and time at a beach or pool. Some kids will work, and others will play all day long. Teachers embrace the break as well—many now getting the chance to unwind and unravel from the past school year, slowly getting themselves recharged and refreshed over the next two months before another demanding “tour of duty” comes their way—always faster than anticipated it seems. I know all about this stuff as I’m the father of four teens and married to a teacher. There is a select group of people who embrace summer, but find it to be, perhaps, their busiest time of the year. These are the school administrators, an unsung bunch that don’t have reason to countdown to the “last day of school” each year. These folks are faced with a myriad of tasks that must be completed over the summer months before the annual return of students and teachers in late August. Whether this is a principal’s first or twentieth year as an administrator, planning everything that needs to get done before the start of the new school year can be a challenge. These chores include such things as hiring new teachers, overseeing class assignments, managing school reparations and acquiring needed books and supplies. Mount Olivet Cemetery is final resting place to countless former educators. In the past, we have featured blog stories on folks like Joseph Henry Apple, Professor William Von Steinman, Hester Posey and Elihu Rockwell. This week we will chronicle one of the most beloved school administrators in Frederick history. His name was Amon Burgee—and education was not only a year-long profession, it was a lifetime passion.  Miel Burgee Miel Burgee The Making of a Professor Amon Burgee was born on a day where much of the nation, at least the northern states, was in mourning. This was April 16th, 1865, the day after President Abraham Lincoln had died as a result of John Wilkes Booth successful assassination attempt. Amon’s birthplace was near Price’s Distillery, once located at the crossroads of the namesake road and Maryland route 75. The distillery is long gone from this locale situated southeast of Urbana, but a current landmark is the Green Valley Animal Hospital. Amon’s father, Miel Burgee (1818-1903) was a native of the area and a lifelong farmer along Prices Distillery Road. His mother, Clara Elizabeth Lawson (1843-1888), was Miel’s second wife. Six children would be blessed to this union, with Amon being the oldest.  Old Pleasant Grove School Old Pleasant Grove School Amon grew up on the Burgee family farm where he learned several of life’s greater lessons, none better than the value of hard work. He attended the Pleasant Grove School and quickly developed a desire for learning and a love of reading books. His biography, appearing in Williams and McKinseys’ History of Frederick County (1910), says of the young scholar: “Almost from the first day he showed a fondness and aptitude for study. Such was his love for school that neither the elements nor three miles of muddy road were sufficient to cause a single day’s absence during eight years’ attendance. This won him the confidence and admiration of his teacher who urged him to continue his studies.“ Amon would go to high school, enrolling in Glenellan Academy in nearby Ijamsville. The school was run by Herbert Thompson from 1878-1888. Burgee’s advanced schooling was not a given, as most farm children customarily went to work full-time (back on the farm) after eighth grade. He completed his classwork in an accelerated rate after just one year. Burgee then attended Western Maryland College in Westminster in fall 1882. He would graduate five years later, having to spend an extra year at the college taking courses in Greek, German, Literature and Science in order to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree as a member of the “Class of 1887.” He had been denied his diploma the previous year because of a requirement to take Greek. He completed four units of the language in that single, additional senior year. Amon Burgee’s path led back to the family farm near Urbana, but not for long. He would accept the principal position for the public school of Union Bridge in Carroll County. Williams’ History of Frederick County claims that the 23 year-old, recent graduate took this position simply as a favor to his friend and fellow Western Maryland alumnus James Diffenbaugh, Carroll County’s school superintendent. On his first day in the new post, students laid in wait, setting to test the moxie of their new principal. Amon reportedly gave them a view of his expectations as he apparently “thrashed” the oldest boy in the school. Suffice it to say, Principal Burgee never again had a discipline problem with any of his other students in Union Bridge.

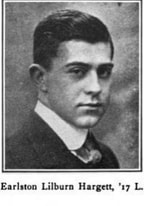

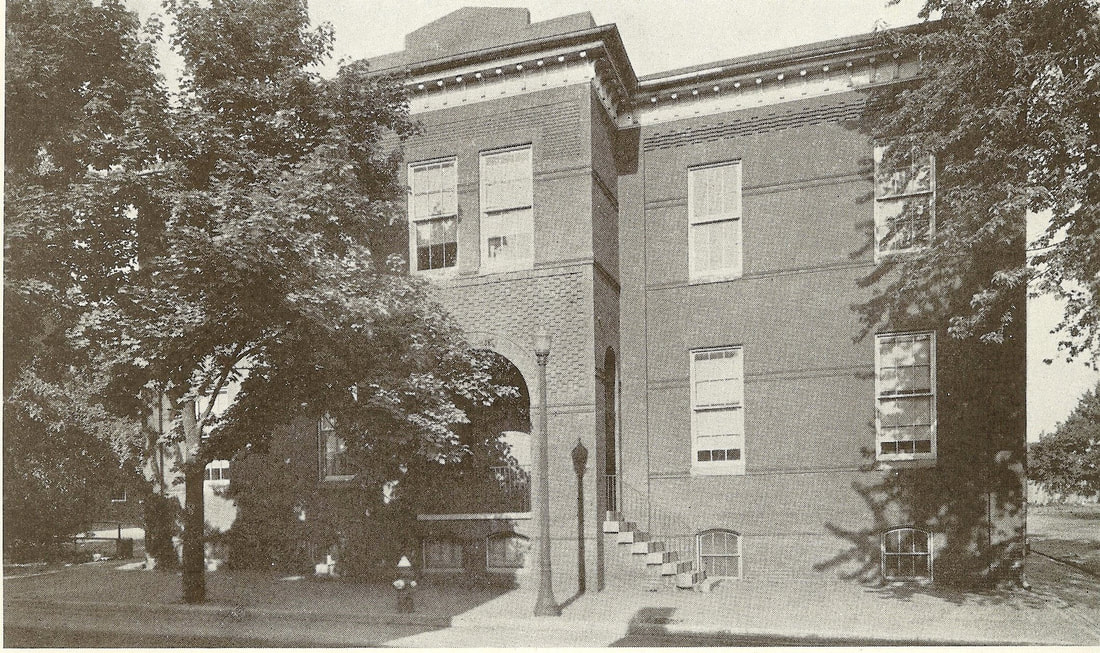

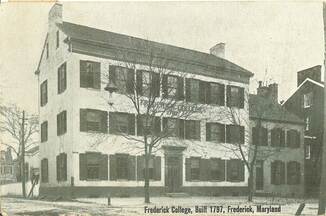

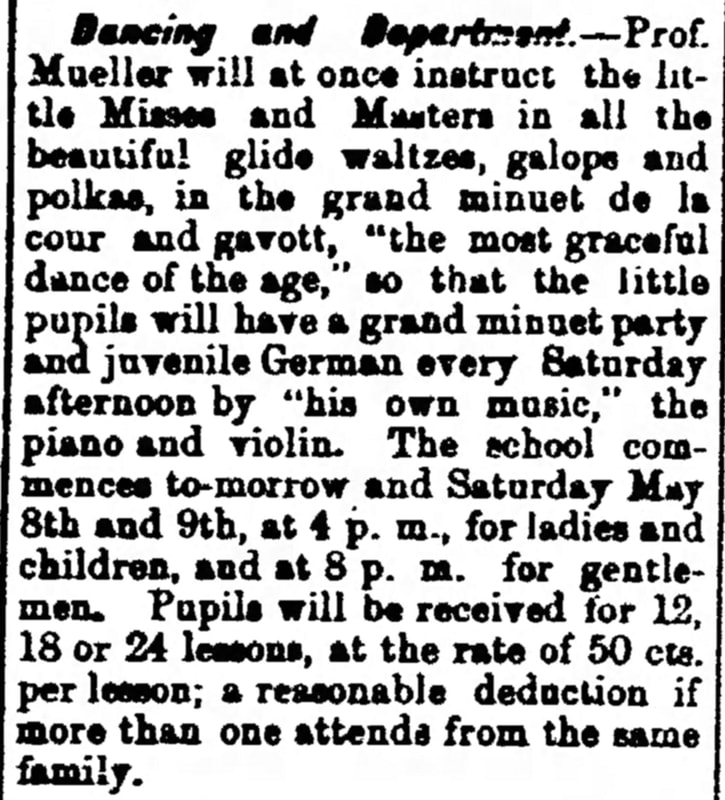

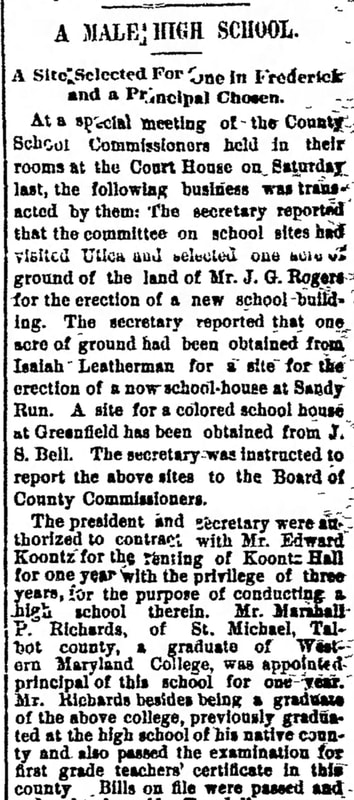

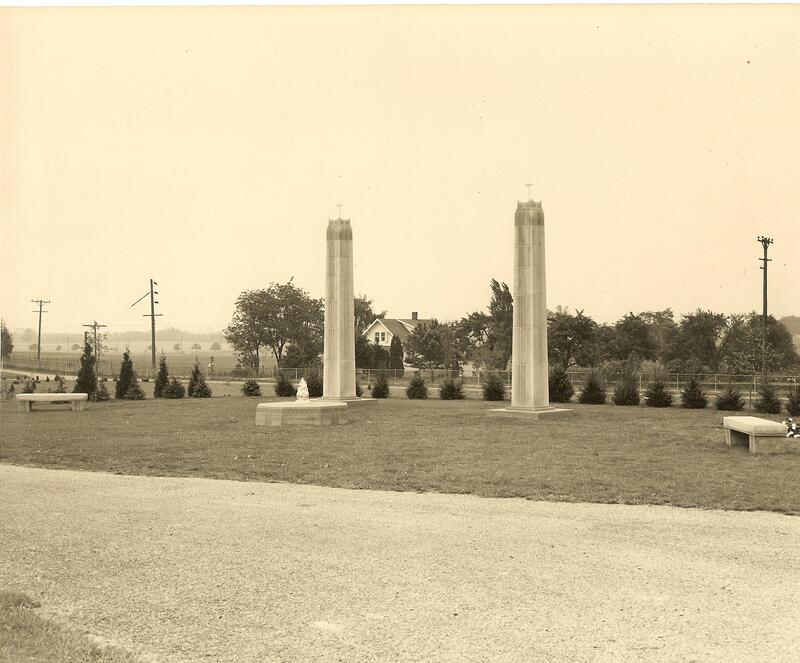

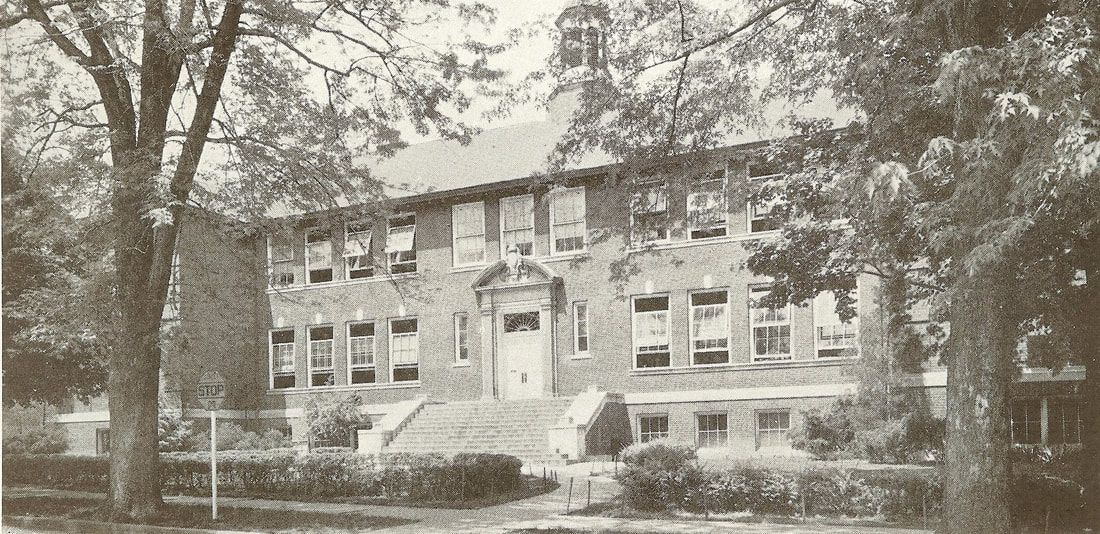

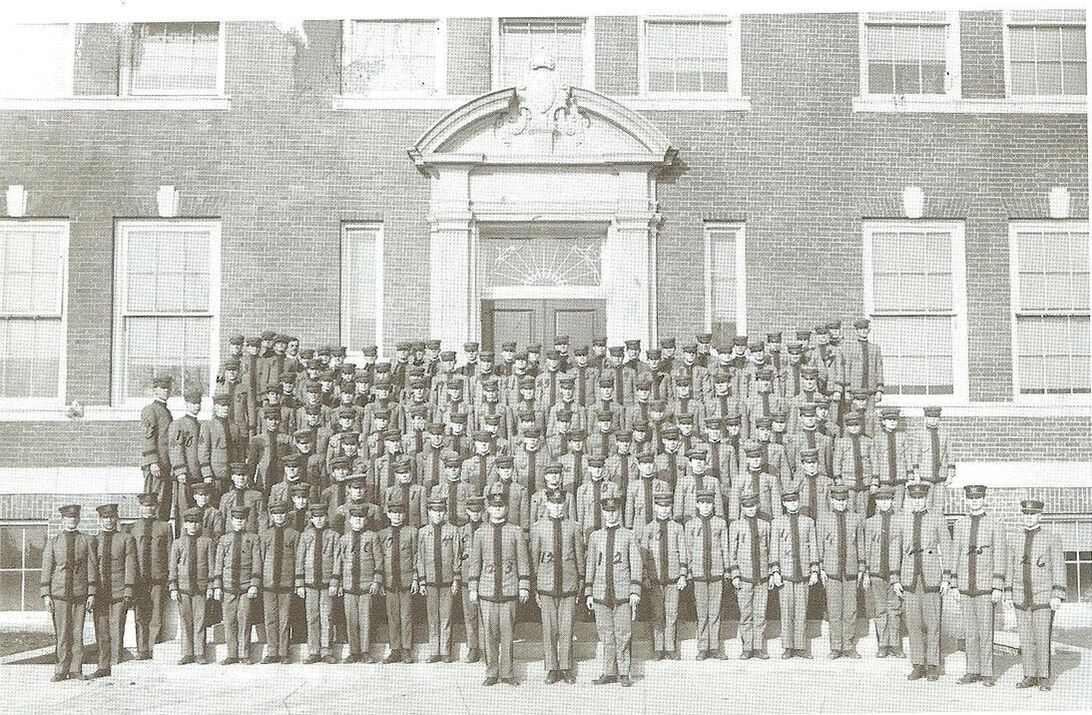

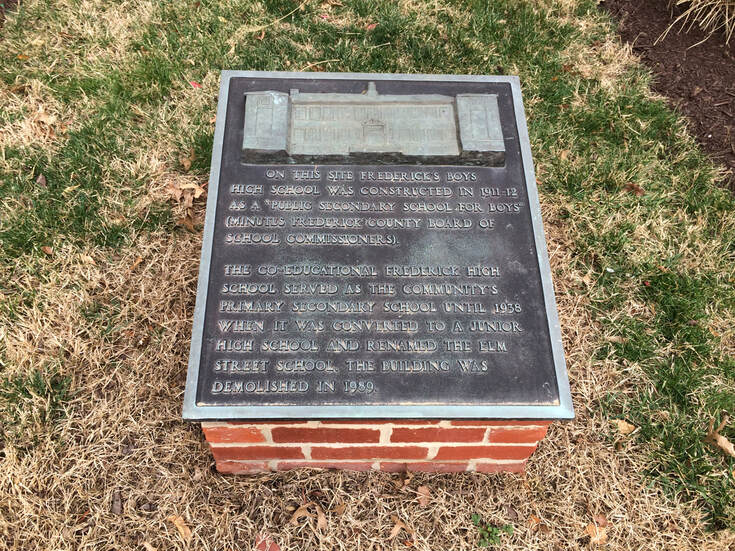

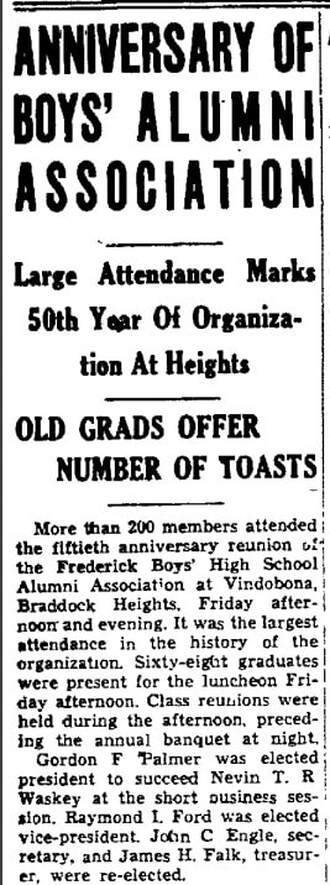

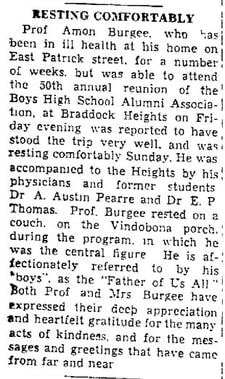

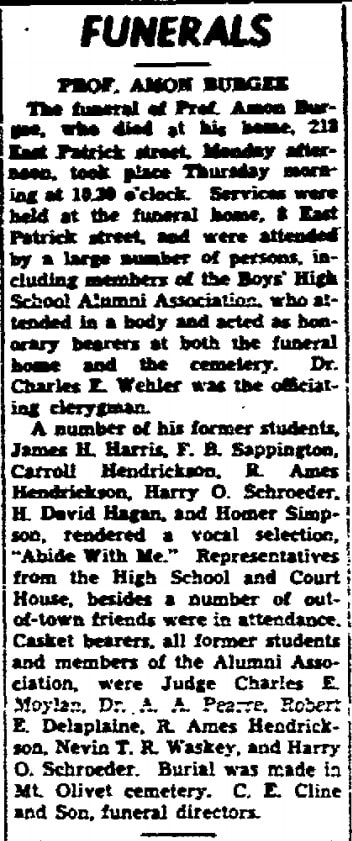

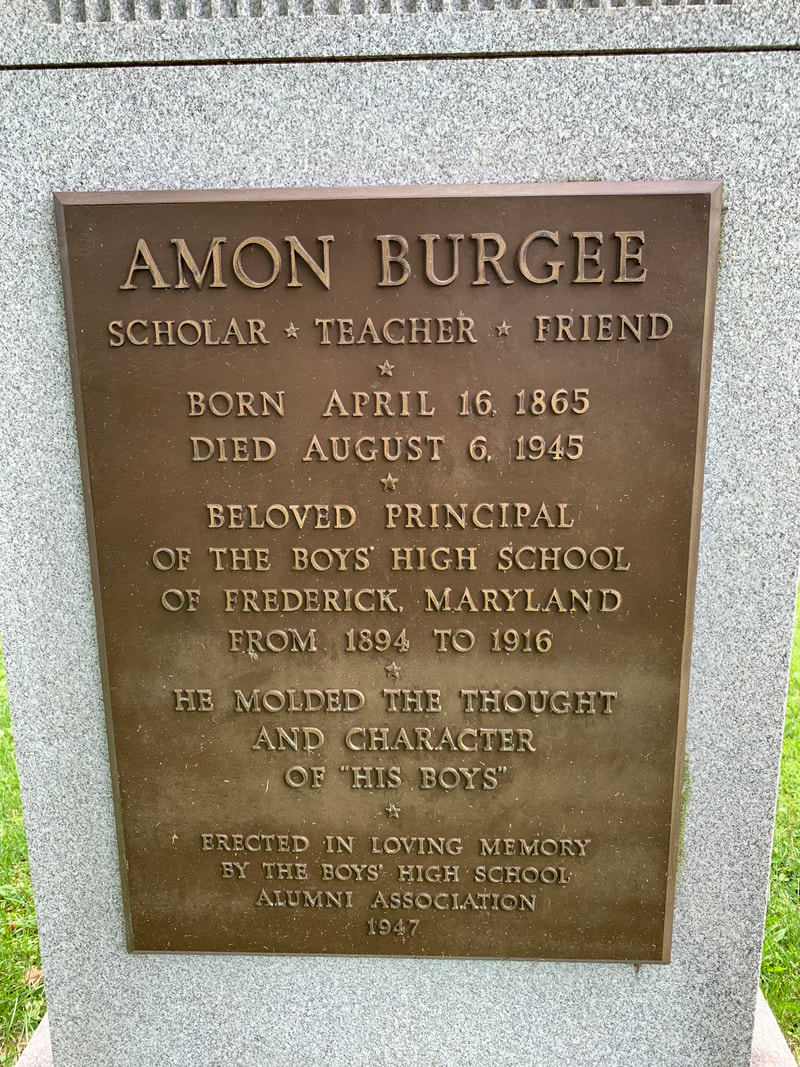

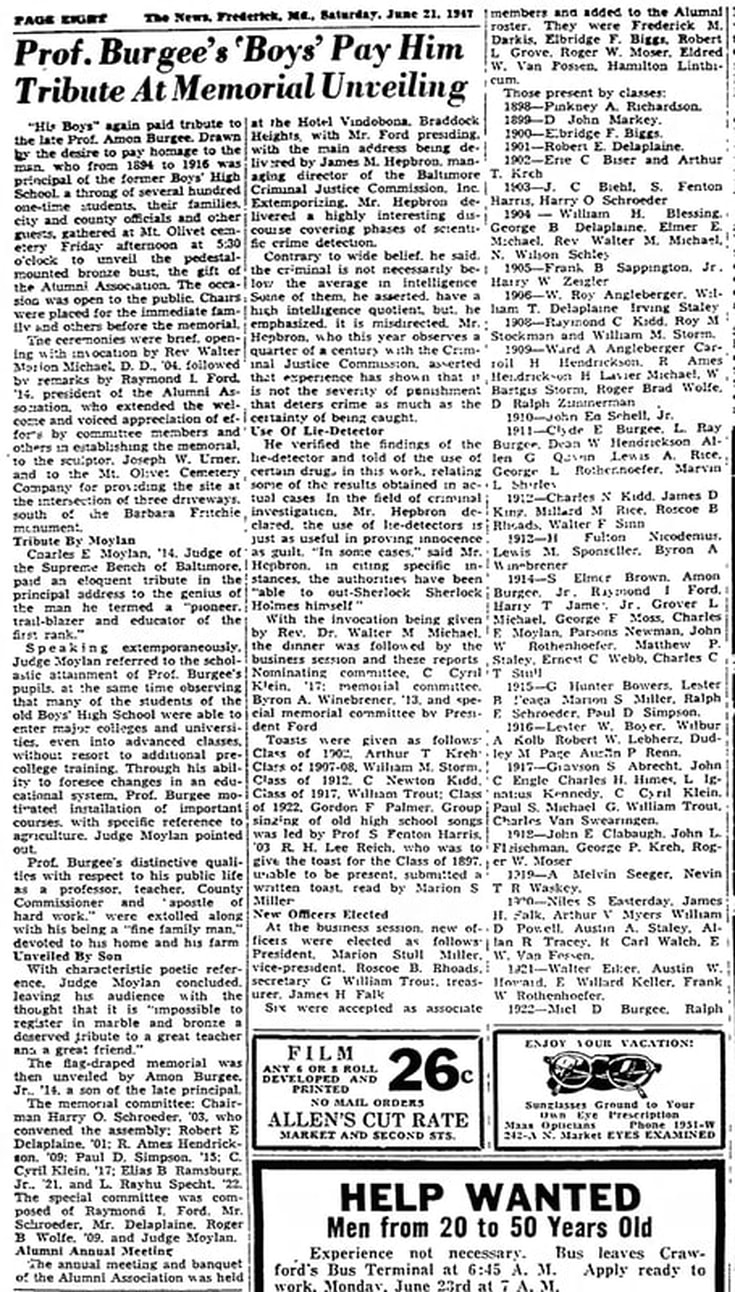

Boy’s High School Up through the nineteenth century, higher education was centered primarily on males and not females. Girls could receive the 3 “R’s” at private schools and from tutors and governesses. These opportunities were certainly not the norm for the typical girl or young lady. Frederick’s heritage includes the incredible story of the Frederick Female Seminary, later known as the Frederick Woman’s College. Under the leadership of the fore-mentioned Joseph Henry Apple, this institution (once housed in Winchester Hall) would become one of the first, and foremost, educational centers for women in the entire country. We know this school today as Hood College, and Frederick can share the laurels as the backdrop for the school’s role in bridging the educational gender gap. Ironically, the first public high school in Frederick was for girls, and not boys. Girls' High School was located on E. Church Street just shy of Chapel Alley and behind St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church and served for many years as the headquarters for Frederick County Public Schools before a modern, high rise facility was opened in the 2000's at the corner of S. East and South streets. Young males of the 19th century attended what was known as the Frederick Academy, housed in an impressive building that once stood on northeast corner of Council and Record streets (adjacent today’s Frederick City Hall). For those not attending “The Academy,” another local option was St. Johns Literary Institute. Boys from all over the state attended this Catholic institution, opened by Jesuits in 1829. One of these students had an even stronger connection to Abraham Lincoln than Amon Burgee (and his birthdate)—this was alleged Lincoln conspirator, Dr. Samuel Mudd, who attended this school in Downtown Frederick’s E. Second Street in the late 1840’s. In 1891, many local community leaders found that the majority of boys here could not afford the tuition fees associated with the above-mentioned two schools of secondary learning. Tax payers requested that a public high school be opened for boys. The Board of County Commissioners and the Board of Education employed Mr. Marshall P. Richards to open a school for boys, who desired “better preparation for life, as well as for College.” The Male High School started in a building located at 314 N. Market Street between Third and Fourth streets and was known as Koontz Hall. Koontz Hall had been the site of a dancing school in 1885, operated by a Frenchman named Monsieur F. William Mueller. Mueller had formerly had stints in places such as Memphis, TN and Louisville, KY and would go on to take a position of professor of dancing for the US Naval Academy in Annapolis. The new high school opened in September 1891 and boasted 13 students. The first graduating class of Frederick Boys’ High School (1892) consisted of three graduates: David Beall, Nelson Beall and Harry Lakin. Professor Burgee was hired in the summer of 1894 to come back to Frederick to carry out the duties associated with the principal position of Frederick Boys’ High School. A small booklet entitled The Boys High School, Frederick, Maryland (1894-1922) by Mary C. Ott gives a description of Amon Burgee’s first day: “It is 8:45am, September 3, 1894—a group is at the entrance to the Hall, waiting to pass judgment on this new principal. ‘He is coming. He looks like business.’ He arrives. ‘Boys, it is time for you to be at your desks.’ Do they loiter as formerly? Oh, no. They take the stairs, nineteen steps, almost as one, with leap and bounds. From now on, it is work. No nonsense. The distance from the Principal’s desk to the last desk in the Hall, was much longer than the usual class room;—the heat of September was intense and the last boy in the row, being too tired a and warm to think, played with a pocket-mirror, reflecting on the sewing of a lady across the street. It had been fun the year before, but this Principal was alert, and that boy was made an example of the foolishness of wasting mind and matter and from that day, no boy in that group wasted his time nor energy in play.” Amon Burgee was overseeing a school consisting of eighth, ninth and tenth grades. Eleventh grade came about later in 1907. Operating under the three year plan, students graduated with 22 Units. Year courses included Latin, Botany, Zoology, Physical Geography and Astronomy. Amon taught all subjects at one point or another and his pupils would go into a variety of occupational fields in the future: professional, political, educational, business, cultural, and recreational. Burgee’s first graduating class consisted of just one student—Jesse Roop Klein. Klein would become a minister, school-teacher and farmer. The number of graduates constantly grew in time, along with it, Professor Burgee’s sphere of influence. He knew his role in life, to grow young minds into competent/community-impacting adults. Burgee's success could also be credited to the talented staff of teachers he had assembled. As for summer vacation, Amon went back to his first “growing experiences” and the family farm near Price’s Distillery. Here he cared for the summer harvest, just after delivering his academic harvest of graduates. Throughout June, July and August, he readied himself, staff and students for the upcoming school year. No rest for the weary! Mr. Burgee served Boys’ High School as principal from 1894-1916. For many years he received a salary of $700/year. Lucrative offers were made by other schools to lure him away, however he declined all of them, some of which promising to double his pay. Mrs. Ott goes on to say of Burgee: Years of fruitfulness and happiness in the continued success of those who had gone out from the Boys’ High, under the guiding hand of himself and his faculty. From the beginning of his regime as Principal, the scholastic assignment had been such, that the evenings were spent at home, in educational preparation. Parents were happy to cooperate and give encouragement to sons to study. Mr. Burgee, and later his teachers did not demand the impossible, but did expect every boy to put forth his best efforts. As enrollment grew, they outgrew their first school home and were given quarters on the third floor of the South Street School. In the interim, the new High School was being built on the North Market St. School grounds to accommodate primary and elementary grades and Mr. Burgee was made Principal of the entire school. Professor Amon Burgee instituted forensic art societies such as classic literature and student debate. A lasting legacy to Amon Burgee is the surviving team name of Cadets attributed to Frederick High School up through the current day. In 1904, Burgee instituted mandatory military training for his students. He formed the Boys’ High School Cadet Corps, which would be drilled by Harry J. Kefauver, another faculty member at the school. The Cadet Corps was a success from the start. Eventually three companies were formed—A, B, C, and the discipline and tactics learned were said to have carried over into student life, home life and civic participation. Burgee’s rationale was that if every boy could become a leader of a school corps company, that student could later become a leader in community life, wherever he lived.  This held true as a number of Frederick Boys’ High graduates under Burgee became pillars in our community. Many also served in the military as America entered the World War in 1917. One former student, and captain of a Cadet Company at Boys’ High, was Earlston Lilburn Hargett. Hargett would go on to become a champion debater at the University of Pennsylvania and earned both a law and business degrees while there. In late September, 1918, 1st Lt. Hargett would lose his life in eastern France while serving in the 150th Field Artillery in the opening volleys of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the deadliest battle in American history. (NOTE: In case you are interested, Cadet Corps training in Maryland was disbanded in 1920 by the State Board of Education.) Amon and his wife were busy raising kids of their own. They resided in Frederick City, living on E. Patrick Street. In 1907, they bought a beautiful country manor house on a 40-acre estate east of town. This was known as Park Hall, built in the 1840's and recently demolished in the last decade. Interestingly, he had bought this home from Robert Downing, one of the top stage actors of the 19th century who is also buried in Mount Olivet. The Burgees would reside here for the next 37 years before moving in town in 1944. Speaking of moving locations, in 1910, a better site was sought to accommodate an ever-increasing enrollment for Boys' High. A new school structure was built at the head of Elm Street. This consisted of a better equipped plant eventually morphed into the first home of Frederick High School when both the Boys’ and Girls’ High Schools were consolidated into a single coed facility in 1922. When Frederick High School was moved across town (to its present site) in 1939, the second home location of Burgee’s old school became known as the Elm Street School and became a Junior High facility that many residents, including my wife, attended. Today this site features a parking deck for Frederick Memorial Hospital. Under Amon Burgee’s leadership, the Frederick Boys’ High School came known as one of the leading preparatory schools in the eastern United States. Burgee retired as principal in 1917, but he practiced what he preached in continuing to serve his community thereafter. In 1930, he was elected county commissioner and was a devout servant to Trinity Methodist Church where he sang in the choir and taught the Men’s Bible Class for 55 years. All the while, Amon never lost his interest in two other things, near and dear to his heart: agriculture in which he served in various offices including in the Farm Bureau and the Frederick County Farmers Cooperative Association, and his former students. Professor Burgee can be summed up as a lifelong cultivator. Likewise, he always held the adoration and respect of his former students. In 1944 a committee was appointed to arrange a fine commemorative event for the following year—the 50th anniversary of the Boys’ High School. This was overseen by the Boys’ High School Alumni Association, consisting of former students whose names read as a Who’s Who of Frederick’s past. The event took place in early June, 1945. Amon Burgee had been ill and housebound for nearly a year, but he would muster up the strength to travel to Braddock Heights and the Vindabona Hotel to make, what would stand, as his last public appearance. The guest of honor had this final opportunity to see the boys he had turned into men. Professor Amon Burgee just didn’t create the institution of Frederick’s Boys’ High School, he embodied it until his last breath. The aged educator died at age 80 on August 6th, 1945, at his home on East Patrick Street in Frederick. Amon would be laid to rest in a lot owned by Linthicum family of whom his sister married into. This is in Area T/Lot 41. The school's alumni association went one step further as a special tribute was erected as a lasting monument to their beloved administrator—one who never took summers off. Former student Joseph Walker Urner was commissioned to sculpt a bust likeness of Professor Burgee, which sits atop a four-foot granite pedestal. This veteran of both world wars was the same artist who had previously crafted the busts of Roger Brooke Taney and Thomas Johnson, Jr. that formerly stood in Court House Square. (To my knowledge, this one has never received threats to be moved.)

A new, and very special, burying place would be purchased for this teacher of men by the alumni association. This was Area AA/Lot 138, a lone parcel that sits as a small island unto itself at the northeast corner of AA, and is buttressed by driveways paralleling neighboring areas MM and T. Professor Burgee's body would be moved to this location on November 6th, 1946. The bust monument would be unveiled on June 20th, 1947.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed